nysascdMission Statement

NYSASCD aims to assist educators in the development and delivery of quality instructional programs and supervisory practices to maximize success for all learners.

nysascd

Executive Board 2023-2024

President

Mark Secaur

Smithtown CSD

President-Elect

Matthew Younghans

Clarkstown CSD

Immediate Past-President

Mary Loesing

Connetquot CSD (retired)/Science Consultant

Vice President for Communications and Affiliate Relations

Amanda Zullo

Tuper Lake CSD

Treasurer

Deborah Hoeft

Young Women’s College Prep

Secretary

Marcia Ranieri

Guilderland CSD

Ex-officio NYS Education Department

David Coffey

Associate in Instructional Services in the Office of Standards and Instruction

Executive Director

Mr. Eric Larison

Solvay UFSD (retired) nysascd.director@gmail.com nysascd.org

Board Members

Martha Group

Vernon Verona Sherrill CSD

Brian Kesel

West Genesee CSD

Timothy Eagen

Kings Park CSD

Marcia Ranieri

Guilderland CSD

Gregory Borman

NYC Department of Education

Lisa B. Brosnick

Buffalo State

Cindy Connors

Orchard Park CSD

Dominick A. Fantacone

SUNY Cortland

LaQuita Outlaw

Bay Shore UFSD

Debbie Baker

Genesee Valley ASCD

Ted Fulton

Hicksville CSD

NYSASCD.org

visit OUR WEBSITE!

As registered members of the New York State ASCD website, we want to encourage you to please visit!

Also if you aren’t already a member please consider joining New York ASCD or suggesting that a colleague join for only $55.00 annually.

As a member of NYASCD you will receive our on-line newsletter, NYSASCD DEVELOPMENTS, as well as our on-line journal, Impact and discounts for all of our professional development activities. Complete information about NYSASCD may be found on our website. This website gives you information about our organization, professional development activities, information about affiliates across the state, and links to other professional organizations and resources.

Foreword

“Shall we play a game?” is a question asked by a supercomputer in the 1983 movie WarGames. Among the gaming options available to Matthew Broderick’s character was Global Thermonuclear War. Thankfully, the supercomputer eventually concludes that “The only winning move is not to play.” This movie sounded the alarm about the potential deleterious impacts of Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) and is particularly prescient today as the world grapples with this emerging technology. While the potentially harmful effects of over-relying on technology are concerning, and worthy of debate, educators need to understand that it has been with us for some time and take the steps necessary to better understand the impacts it will have on teaching and learning. What has once been considered cheating is now a tool that can be used via a blended approach to essay writing that combines human thinking with artificial intelligence. In this way, the strengths of each can help to create a better, yet still authentic product. As the creator of the supercomputer in WarGames stated…“General, you are listening to a machine. Do the world a favor and don’t act like one.”

Mark Secaur, Ed.D., is the Superintendent of Schools for Smithtown Central School District. Prior to his tenure in Smithtown Schools, Dr. Secaur was the Deputy Superintendent for the Hewlett-Woodmere School District and Principal of Oceanside High School. Dr. Secaur is an Active Past-President of LIASCD and President of NYSASCD.

nysascd on Social Media

Please join us and follow along:

nysascd

& PASS

The ASCD PASS program offers ASCD affiliates an opportunity to earn additional revenue. Through PASS, NYASCD can earn income from new and returning business generated for ASCD programs, products, and services. Affiliates are assigned a unique source code (ours is NYAFF), and each person that uses the affiliate codes when making an eligible purchase will be contributing to our affiliate’s financial health, further enabling us to accomplish important work.

LaQuita Outlaw, Ed.D., has worked in school leadership for over a decade. Dr. Outlaw serves as a peer editor for Corwin Press and assists several local organizations with organizing professional development opportunities for educators across Long Island.

Learning and technology have been close relatives who are often found at odds with each other with the initial introduction. Our knowledge about the way people learn has evolved over the last decade or so with brain research. In the article “Credibility” by Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey, we see how the focus on learning improves student outcomes. Trust is an essential component of learning. The question then becomes, is that why some classroom teachers are concerned about the role Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) plays in learning.

John Spencer in the repost of his article entitled, “The Future of Writing in a World of A.I.” (Part I), and Tim Dawkins in the article “Ownership, Not Fear: Preparing Educators for A.I. in the Classroom” explore the unknowns and share some ways that A.I. can be considered as a partner in the educational setting. Spencer looks specifically at how A.I. might change writing in the classroom. Understanding how best to responsibly incorporate this platform into the classroom requires a level of familiarity that comes with exploration. Tim Dawkins shares an approach he used with educators in his district to familiarize staff with the way artifical intelligence works.

In the end, each development culminates in providing more robust learning opportunities for students and staff. The third installment of the “DNA of Learning Series, Requisite 1: Navigating Uncertainties,” outlines how to use the uncertainties in learning to engage students. The authors, Greenleaf, Millen, and Roth take readers through an application of the learning model. Despite the ever-changing landscape of education, one thing is consistent, learning prevails.

Many thanks to the writers of this issue of the Impact Journal and to Mark Secaur for their contributions and leadership.

The Role of Credibility

Douglas Fisher & Nancy Frey

Douglas Fisher & Nancy Frey

Douglas Fisher, Ph.D., is professor and chair of educational leadership at San Diego State University and a leader at Health Sciences High and Middle College. Previously, Doug was an early intervention teacher and elementary school educator. He is the recipient of an International Reading Association William S. Grey citation of merit and an Exemplary Leader award from the Conference on English Leadership of NCTE. He has published numerous articles on teaching and learning as well as books such as The Teacher Clarity Playbook, PLC+, Visible Learning for Literacy, Comprehension: The Skill, Will, and Thrill of Reading, How Tutoring Works, and How Learning Works.

So you want to have an impact on students and the schools they attend? That’s probably why you are reading this journal. You care about the outcomes of your efforts and you look for the best practices that move learning forward. You move from ideation to implementation and dedicate hours to honing your craft. Even with all of that, sometimes our efforts fail to have the impact that we desire. Perhaps that’s because we have not invested sufficiently in credibility and, instead, spent all our time focused on the teaching rather than the learning.

Here’s how we landed on credibility. We were observing classrooms with essentially the same lessons. Not scripted lessons or prescriptive lessons. But rather lessons that the teachers had planned together based on what were then the new standards. There were many similarities among the classrooms. The same strategies were used to address the same learning intentions. The same materials were provided to students and the same tasks were assigned.

But the impact differed widely. In our search to explain these differences, we found the evidence on teacher credibility and by extension leader credibility. And we were surprised by the impact; the effect size of teacher credibility is 1.09, among the highest influences on students’ learning. There wasn’t an effect size for leader credibility, and the term is rarely used

in education, but the studies in business, government, nonprofits, and healthcare were stunning. Leaders with high credibility create environments where people are happier and more productive. We do know that a healthy school climate has a positive impact on students’ learning, with an effect size of .44, just above average in the impact it has. The question is, what is teacher credibility and leader credibility and how can we develop it? Importantly, we don’t get to decide if we are credible, our students (or staff members in the case of leaders) do. It turns out there are four aspects of teacher credibility and five for leaders.

Trust

The first aspect of credibility for teachers and leaders is relational trust. The people around us want to know if we have their best interests at heart and if we are reliable and honest. Others look to our actions to decide if we are trustworthy. Remember, trust is easier to gain than regain. Start out right by using students’ names. Establish routines and follow them. Be honest with students and explain when you can’t explain something. Think about the trusting relationships you have with others and apply those rules in the classroom and school. It really is simple but without attention can get easily violated.

You’re a teacher and you said that we were going to an assembly on Friday but we didn’t (and you didn’t tell us why). Trust is tarnished. You told a student that they did a good job, when it really was average. Trust is tarnished. You said something harsh in frustration and didn’t apologize. Trust is tarnished. When trust is violated, it is human nature to look for additional evidence that the person is not trustworthy. When something goes wrong, make amends. Apologize. Give it time and forgive yourself. Tomorrow is a new day and you can work to rebuild trust.

Nancy Frey, Ph.D., is a Professor in Educational Leadership at San Diego State and a teacher leader at Health Sciences High and Middle College. She is a member of the International Literacy Association’s Literacy Research Panel. Her published titles include Visible Learning in Literacy, This Is Balanced Literacy, Removing Labels, and Rebound. Nancy is a credentialed special educator, reading specialist, and administrator in California and learns from teachers and students every day.

This applies to leaders as well. Do staff members trust you? Are you trustworthy? Are you honest and reliable? And do you apologize and then explain when things go wrong, making amends whenever possible? Like teachers, your actions are noticed. When you are disrespectful to someone, we all think that we could be next. As Covey (2008) tried to teach us in The Speed of Trust: when trust exists, things go faster. If you are thinking of a new initiative or program and you do not have the trust of the staff, it’s doomed to fail. An investment in trust is an investment in the wellbeing of the school.

Competence

Students have spent hundreds, if not thousands, of hours with teachers. They know what good lessons feel like. And they know when they are not learning or when it is chaos in the classroom. When teachers change their strategies too frequently, students believe that the teacher doesn’t know how to teach. When lessons are not organized and the examples are irrelevant, students question the competence, and thus the credibility, of the teacher.

There is a difference when it comes to leaders. The vast majority of teachers have not been principals (or coaches or even department chairs) and thus there is less clarity about the skills needed to do the job. So leader competence is judged by communication skills. It seems that

nearly every challenge in a school has a lack of communication as a root cause. The solution in this case is more and different communication. Leaders need effective communication systems. Perhaps the guidelines for a phone call, text message, versus email are not clear. Under what circumstances should I, as an employee in this school, call, text, or email you? And perhaps there needs to be daily updates provided by leaders about the goings-on of the school. Those are just ideas; our point here is that communication is a key driver in perceived credibility of leaders and ineffective communication systems compromise impact.

Dynamism

Interesting word, right? The dictionary says that dynamism means that you’re full of energy. But when it comes to credibility, it’s more than that. Yes, the environment (schools and classrooms) should be full of energy, but they should also be filled with passionate people who care deeply about learning. People who exhibit dynamism are confident and they choose to engage; they are not passive participants. One of the ways that we compromise our dynamism is through our presentations. When we project terrible slides, with lots of words and generic images, people start to wonder if we care about their learning. When the oral part of the presentation is simply reading the slides, perceptions of both dynamism and competence suffer.

Of course, dynamism is not limited to the ways in which we present information. Wangberg (1996) notes that “the best teachers are people who are passionate about their subject and passionate about sharing that subject with others” (p. 199). He argues that there are at least four ways to demonstrate passion in the classroom:

1. enthusiasm

2. immersion in the subject

3. creative and innovative approaches

4. the teacher as a learner

In other words, it’s not about changing our personalities. Yes, some people are more reserved than others. It’s about choosing to

as do the places we put our body. For example, the following non-verbal clues signal to others that they are valued:

• Facial expressions

• Proximity

• Eye contact

• Tone of voice

• Gestures

• Touch

In the classroom, it’s proximity. In other words, how close you get to students in the physical space. Teachers can use proximity as a classroom management tool as well as a tool to convey to students that there is a connection. The same goes for leaders. In some schools, it’s

demonstrate passion for the learning process, which applies to leaders as well. Leaders need to be passionate about education, including the learning of teachers.

Immediacy

Essentially, immediacy is about being there—being present, both physically and mentally. Students perceive this as closeness and relatedness. Can they connect with you as a person? We are not suggesting that teachers should be friends with students but rather that there is a connection, a bond if you will, that allows people to feel connected. Our verbal and non-verbal behaviors convey immediacy

rare to see the leaders move around the building, while in others they seem to be everywhere, talking with everyone. For example, do leaders attend professional learning events alongside teachers? Immediacy can be fostered when people are learning together.

Forward Thinking

The final aspect of credibility, which was only found in the research on leaders and not teachers, focuses on the ability to be optimistic and plan for the future. People who work in schools want to know where their organization is going and how they fit into the future. They want leaders to have plans

Immediacy can be fostered when people are learning together.

for the future and be able to lead the way. As Kouzes and Posner (2009) note, what people want most from their leaders, as opposed to colleagues, is to be forward looking. They want to be part of an organization that is mission driven, goal oriented, and well prepared for the challenges ahead.

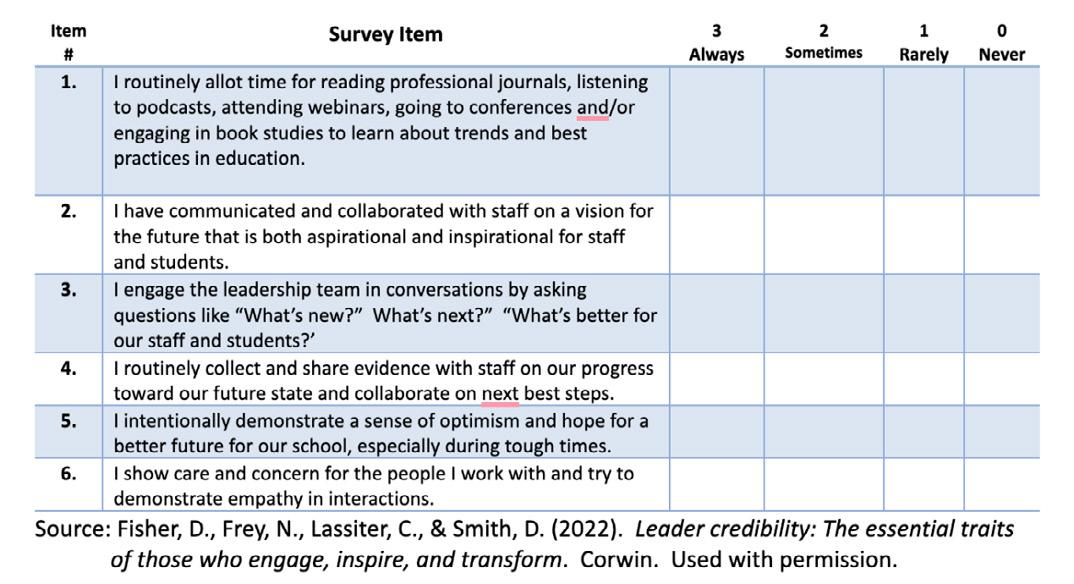

It seems reasonable to suggest that students would appreciate something similar. They want to know where they are going as a class and what goals they will accomplish. And they want to know that they will be prepared for the challenges ahead, be that tomorrow or well into their future. We have created a survey item that you can use to assess your ability to be a forward thinking leader (see below.)

Conclusion

As you think about the impact that you want to have in the classroom or

school, it’s important to recognize that new initiatives and programs are more likely to be implemented by individuals who are credible. And we can take actions to improve our credibility and thus have a greater impact on the people around us.

REFERENCES

Covey, S. (2008). The speed of trust: The one thing that changes everything. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kouzes, J. & Posner, B. (2009). To lead, create a shared vision. Harvard Business Review.

https://hbr.org/2009/01/to-lead-createa-shared-vision

Wangberg, J.K. (1996). Teaching with a passion. American Entymologist, 42(4), 199-200.

The Future of Writing in a World of A.I.

John SpencerJohn Spencer is a former middle school teacher and current college professor on a quest to transform schools into bastions of creativity and wonder. He is passionate about seeing schools embrace creativity and design thinking. In his podcast, The Creative Classroom, he explores the intersection of creative thinking and student learning.

John explores research, interviews educators, deconstructs systems, and studies real-world examples of design thinking in action. He shares his learning in books, blog posts, journal articles, free resources, animated videos, and podcasts.

Back in December, I showed ChatGPT to a friend of mine who is also a professor. “I’m not worried about AI in my humanities courses,” she said. “Not at all?” She shook her head. “I know of colleagues who are going back to the blue books and banning devices. Or they’re looking into programs that can detect ChatGPT in an essay. But I’m just wondering how we might need to transform the essay.” We then talked about Socrates and his concerns about writing.

One of the main reasons was that Socrates believed that writing would cause people to rely too much on the written word, rather than their own memories and understanding. He believed that people who read a text would only be able to interpret it in the way that the author intended, rather than engaging in a dialogue with the ideas presented and coming to their own conclusions. Moreover, Socrates was concerned that writing could be used to spread false ideas and opinions, and that it could be used to manipulate people. Sound familiar? These are many of the same concerns people have with AI.

“I’ve been through this before,” she adds. “When I realized students could just download whole essays, I started requiring students to do pre-writing that they turned in. I changed to high-interest prompts that you couldn’t find online. Now I see that ChatGPT can generate responses to those high-interest prompts and I’m going to think hard about how to treat AI as a tool.”

Together, we planned out a solution that would include blending together AI-generated and student-generated text. It was similar to what I describe later in this article. The essay isn’t dead but it is changing. It will continue to evolve in the upcoming years. For now, the use of AI is forcing us to ask, “When is AI a learning tool and when is it cheating?”

HOW WILL ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE CHANGE THE WAY WE WRITE?

When Is It Cheating?

When I was a new middle school teacher, I had several teachers warn me not to have my students use spellcheck. If we let students use spellcheck, students would grow dependent on the tool and they would become awful spellers. I had similar concerns as well. If we relied too heavily on technology to fix spelling mistakes, would students ever bother to use correct spelling?

That semester, I had students submit a writing sample. I then counted the words and the number of spelling errors to find the rate of spelling mistakes. I then had students do a handwritten assessment at the end of the semester. There was a significant decrease in the number of spelling mistakes when comparing the initial student samples to the samples at the close of the semester. It turned out this tool for cheating was actually providing students with immediate feedback

on their spelling. Instead of mindlessly clicking on the spellcheck, they were internalizing the feedback.

We now use spell check all the time. What was once a tool for “cheating” is now a tool we use for writing.

What Was Once Considered Cheating is Now Just a Tool

The truth is students are already using AI in their writing. We don’t tend to think of spell check as AI. But it is a primitive example of a smart algorithm. While spell check software is not as advanced as the newer generations of AI, it still relies on machine learning and pattern recognition to improve its accuracy over time. Some spell check software may also use natural language processing techniques to detect contextual errors, such as correctly spelled but misused words. If it seems as though your spell check and grammar checks on Word and Google Docs have improved over the years, it’s because they have.

Students are already using more advanced AI in every phase of the writing process. When doing research, the auto-fill option in Google narrows down the search for students. When typing in a Google Document, the auto-fill option will often complete sentences for students. As students edit their work, the grammar check offers suggestions for what needs to change.

Certain students might even use Grammarly to polish their writing in the editing phase. The AI here is so subtle that we sometimes miss it. But machine learning is already fueling aspects of the student writing process.

Note that all of these tools have been considered cheating at some point. The same is true for calculators in math and for spreadsheets in statistics. Every technological advancement has been considered a form

So if it feels like ChatGPT is more akin to cheating than previous AI, it’s because it functions in a way that more closely mirrors human thinking. Clippy was cute and even acted a bit human it its tone but current chatbots can feel as though you are actually talking to a person.

of cheating at first. However, eventually, these tools become essential elements to the learning and creative processes.

Somehow, ChatGPT feels different. As a newer generation of AI, it is built on deep learning. This new generation of AI relies on algorithms designed to mirror the human brain. That’s part of why ChatGPT feels so human. Deep learning models learn from massive amounts of data sets and engage in pattern recognition in a way that’s not explicitly programmed. In other words, the algorithm is learning and can now make predictions and generate entirely new ideas. The term “deep” in deep learning refers to the use of multiple layers in a neural network, allowing the system to learn and represent increasingly complex features at each layer. If a spell check is one-layer deep, ChatGPT is multilayered.

So where does that leave us with cheating? When is AI simply a tool to enhance learning and when is it co-opting and replacing a vital part of the learning process? It can help to think of it on a continuum. I love the way Matt Miller, from Ditch that Textbook conceptualizes it (Table on following page).

As Miller describes, “We’re going to have to draw a line—as educators, as schools, even as school districts—to determine what we’re going to allow and what we aren’t.” I love the last question about how students might use AI in the future because it might vary from task to task. In writing blog posts, I might consult ChatGPT for ideas or even use it to explain a definition (where I then modify and re-write it). However, I wouldn’t want ChatGPT to write this. I want it to be my own voice. On the other hand, I could see the appeal of AI to answer my emails or even create a first draft of technical writing after I generate an outline. The truth is we are all going to use AI in a blended way.

Somehow, ChatGPT feels different.

A Blended Approach to Essay Writing

This blended approach moves away from the either/or options of embracing Artificial Intelligence or blocking it entirely. Instead, it focuses on using AI wisely to enhance the learning while also embracing the human elements.

A blended approach might include a mix of hand-written and AI-generated writing. Students can create sketchnotes and blend together drawings and text in an interactive notebook or journal. These low-tech options focus on writing as a way of “making learning visible.” Here, students choose old school tools because the simplicity provides more flexibility for deeper thinking.

But these same students might also use a chatbot to generate new ideas or use an AIgenerated response that they then modify and amplify. They might use AI as the starting place and add their own unique voice to the finished product. This could happen in the same class period. Students in a blended mode can shift back and forth between the human and artificial intelligence.

Part

of learning how to use

AI wisely is finding the best contexts for using AI. This starts by recognizing the strengths of both the human and machine learning. Machine learning does well with synthesizing information from multiple sources and generating text that’s clear and readable. Machine learning can also help with editing

and ideation. But if machine learning offers artificial intelligence, humans offer authentic intelligence. We do well with voice and tone (especially humor). We understand context and can write with empathy. While AI does well with creativity, we are better divergent thinkers.

A BLENDED APPROACH THAT COMBINES HUMAN THINKING WITH ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Initial Conceptual Understanding

I sometimes think about this as the prepre-writing. It’s the phase where students access their prior knowledge before asking questions and engaging in research. A blended approach might start with a K-W-L chart on a shared document. Students jot down everything they know about the topic. Next, they write down everything they want to know about the topic. At this point, instead

of moving into research, students would use a chatbot (like ChatGPT) to ask questions and learn about the topic. The dynamic nature of a chatbot allows for clarifying questions that are tailored to a student’s understanding.

For this example, I’ll give a social studies essay asking, “How susceptible are we to having a World War III?”as a part of their unit on World War I.

So a student might ask, “What were the causes of World War I?” The answer ChatGPT gives is:

1. Militarism: The arms race between the major powers in Europe, particularly Germany and Britain, had been escalating for many years before the war. The belief in the power of military might lead to an increased emphasis on building up national armed forces.

2. Alliances: A system of alliances had developed between the major powers of Europe, which meant that if one country went to war, its allies would also be drawn in. The main alliances were the Triple Entente (France, Russia, and Britain) and the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy).

3. Imperialism: The competition for colonies and territories around the world led to tensions between European powers, particularly Germany and Britain.

4. Nationalism: The belief in national superiority and the desire for selfdetermination led to tensions and conflicts between ethnic and national groups, particularly in the Balkans.

5. Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand: The assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, by a Serbian nationalist in June 1914, provided the trigger for the outbreak of war.

The student might ask ChatGPT to simplify it with a prompt like, “Explain it to someone in the eighth grade.”

1. Militarism: This means that the countries in Europe were always trying

to build up their armies and make them as strong as possible. It was kind of like a competition to see who could have the biggest, strongest military.

2. Alliances: Some countries in Europe had made agreements with each other that if one of them went to war, the others would help them out. It was like a team sport, where if one player gets into trouble, the others come to their aid.

3. Imperialism: This means that some countries wanted to take over other parts of the world, like colonies in Africa or Asia. This caused tension because different countries wanted the same territories, and they were willing to fight for them.

4. Nationalism: This is when people feel very strongly about their own country and think it’s better than any other. This led to conflict between different groups of people, especially in the Balkans, where there were many different nationalities and ethnic groups.

5. Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand: This was the event that triggered the start of the war. Archduke Franz Ferdinand was the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and he was assassinated by a group of Serbian

nationalists. This set off a chain of events that eventually led to war.

At this point, the student might ask follow-up questions, like “Why would an assassination lead to a whole world at war?” Or perhaps this person is confused by militarism and asks, “Can you give me examples of militarism?” Or maybe they focus on the U.S. and say, “Did Americans care about World War I?” It could be a random question like, “What did they call World War I before World War II happened?”

At this point, students can add to their KWL chart. They might engage in some initial research and view videos or read articles. The process would be dynamic.

Research

In this phase, students would engage in online research by generating questions and finding answers. They might start with an initial set of questions but then amplify it by asking a chatbot to come up with research questions for them. During the online research, they would read articles and add to their research chart (with questions, answers, and citations) but also use the chatbot to clarify misunderstandings. Students might work in teams to compare their information and even go entirely human with a Socratic Seminar. In the end, students would create a hand-drawn sketchnote showing the

connections between ideas. In other words, how did nationalism relate to imperialism?

Organizing Ideas and Outlining

In this phase, students would brainstorm ideas and organize them into a coherent outline. They might do a mind map or organize their ideas with sticky notes. At some point, students would create an initial outline for their essay. For sake of transparency, they would screenshot the initial outline and then ask for the chatbot to create an outline. Then, after comparing the outlines, they would modify their own outline. Students might even generate multiple outlines using the regenerate responses button on ChatGPT.

Writing

In this phase, students could take their initial outline and ask for the chatbot to generate the actual text. They would take an initial screenshot with a time stamp and then copy and paste the text into a shared document (Google Document). From here, students would modify the text to add their own voice. They would need to add additional sentences and perhaps even break up paragraphs. Using their research chart, students would add facts and citations that they then explain. The initial chatbot text would be black but the human text would be a color of the students’ choice.

Editing and Revision

As students move toward revision, they could engage in a 20-minute peer feedback process:

A key aspect of editing and revision is asking, “how is this being received?” or “how do actual humans respond to this piece?” Most of the feedback could be the type that humans do well, such as voice, engagement, tone, and clarity. But students could also ask for specific feedback from the chatbot. It might be something like, “How can I make my argumentation better?” or “What are some changes I could do to make the essay flow more smoothly.” Students might engage in a one-on-one writing conference with the teacher but then move back to the AI for additional targeted feedback.

Adding Multimedia

If students want to transform their essay, they could add a human touch by doing a video or audio essay. You can give students examples of video essays like those of the Nerdwriter YouTube channel. Here, they combine images, video, and text with their distinctly human voice. They might sketch a few slides to illustrate key points or even animate these in the style of Common Craft videos. Again, this approach blends together technology with the human touch. But students can use AI as a tool to generate images based on command prompts. They might also ask a chatbot to come up with ideas for images or videos to use alongside their voice.

The DNA of Learning

Part III, Requisite 1: Navigating Uncertainties

Robert K. Greenleaf, Elaine M. Millen, and LaVonna RothIntroduction

Robert K. Greenleaf, Ed.D., has 45 years of experience in education from superintendent to playground supervisor. He was a former professional development specialist at Brown University and an adjunct professor at Thomas College SNHU and USNII-GSC. As President of Greenleaf Learning Bob specializes in strategies for understanding behaviors, learning and cognition. He holds a doctorate in education from Vanderbilt University and is the author of eight instructional books. bob@greenleaflearning.com

Each article in this five-part series will unpack a blueprint for re-starting our passion as educators. The collective series will represent a comprehensive outline of fundamental requirements for timeless learning as we emerge from the COVID ashes and rebuild our lives as educators.

We need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they’re falling in. (Tutu, 2014)

Navigating Through Life’s Uncertainties

Have you ever thought about why some of us can navigate successfully through the unexpected happenings in our daily life? These appear in many forms: a difficult morning…yes, it’s the flat tire as you walk out the door to go to work; the birthday party that was just moved to your house with two hours’ notice; difficult news; uninteresting content with a test at the end of the class; the two-year old’s outburst at the restaurant; forgetting to take the meds and the proverbial badhair day! Navigating uncertain times is one of life’s mainstays.

Elaine M. Millen, M.Ed., C.A.G.S., has over 50 years of experience in education as a teacher, principal, director of special education, curriculum director and assistant superintendent of schools. She has taught at both the undergraduate and graduate levels in both public and private institutions. As an educational consultant and instructional coach, she has worked with hundreds of school leaders across the country and has written several articles on transforming professional learning opportunities for teachers, students and leaders.

Elaine.millen90@gmail.com

Success and confidence depend on developing the skills needed to problem solve for solutions.

Articles 1 & 2 conveyed that once relationships are mastered, three requisites for purposeful learning can be tackled. Optimal learning depends on competence in the requisites of 1) navigating uncertainties, 2) the art of relating and 3) human cognition.

Navigating Uncertainties

As our life has become more complex, the culture of schools has also been presented with challenges to the structures of the organization as well as to teaching and learning. These uncertainties have increased, coming from conflicting information; differing perspectives; underlying beliefs; novel occurrences and the impact of 21st century unknowns. Navigating these uncertainties will require our schools to focus instruction on the deep thinking around problem solving. Shifting from getting the answer as quickly as possible to understanding and learning the skills needed to solve problems in a variety of settings and contexts is critical for a successful future. In a society that relishes “quick fixes” this teaching will require a focus on essential competencies and big ideas in learning. This shift must become the focus of andragogy and pedagogy.

For several years, we have heard the importance of teaching the next generation of learners the 21st century skills. Many have referred to them as the 4 C’s: critical thinking (problem solving), communication, collaboration and creativity. Teaching these skills to the extent needed for deep thinking and transference, has been undermined by trending programs. We have been wooed into programs with the assurance of anchoring activities to problem solving skills

but bypassed organic applications across varied contexts in favor of sanitized weekly lessons out of context. Isn’t problem solving a lifelong competency that everyone—at all ages—and in all walks of life, will benefit from mastering?

If there’s one constant, it is that we will be challenged— often—and in many ways! Some issues will be minor, some substantial. Are all at school taught ways of dealing with interruptions to expected outcomes? When the curtain opens, we must be problem solvers throughout each day, digging beneath symptoms to identify causes. Attitudes, behaviors and struggles in the day’s lesson must first determine if the content is relevant to students. When uncertainties occur, we circle the wagons and engage in supportive problem solving. No child or colleague left behind! Mistakes and challenges are to be respected as opportunities for growth. What is our known, expected response when a disruption happens? When we replace “what is happening?” with “why is this happening?” our disposition toward problem solving shifts.

Coaching Uncertainties

We persistently hear “I don’t know,” “I can’t,” or experience other behaviors that exhibit a lack of capacity to navigate uncertain moments. Building student-managed competencies around identifying the problem and knowing how to begin to address it, will require explicit teaching and modeling. Understanding why it is important to clearly identify the issue, how to begin analysis, and make decisions about options for getting un-stuck are imperative for self-regulated behaviors (Greenleaf, 2005). Front loaded, yes. Saving time in the long run, absolutely!

As we or a student becomes “stuck,” what do we do? Where do we begin? How do we become un-stuck? Often the

LaVonna Roth, M.A.T., M.S.Ed. is an engaging and interactive keynote speaker, consultant, educator, and mom. LaVonna bridges her passion for how the brain learns with identifying how every individual S.H.I.N.E.s with their mindset and socialemotional well-being. She supports schools in harnessing the S.H.I.N.E. framework, increasing psychological safety, & building the foundation based on the brain sciences. LaVonna has 3 degrees, is the author of 8 books, and has worked with organizations in the U.S./Canada and internationally.

proverbial carrot or stick is administered. Manipulation/control is used to quell the issue. However, we all know such responses are temporary, unresolved and exhaustingly repetitive. We tell students to problem solve, but do we teach it or model it within context? As a situation presents itself, do we develop a process with the students to ensure transparency? Do we develop a process collaboratively with students, so they understand why the thinking is important? Thus, teachers begin by making their uncertainties public. They have the courage to become learners with the students by stating why the circumstance is troublesome,

and modeling how their thinking evolves. Demonstrating with and for learners the process of 1) identifying the pattern that has been interrupted (the perceived problem), 2) why it needs to be addressed, and 3) openly analyzing (unpacking) ideas, perspectives, options, and causes to model ways of tackling challenges.

There are many problem-solving approaches. Most outline steps such as define the problem; gather information; generate possible solutions; weigh each option’s benefits and shortcomings; and then decide, do and evaluate.

Example

As early as five weeks into homeschooling during the pandemic, I saw fear in my granddaughter’s eyes. The barrage of news had already begun to take a toll on her wellbeing. Together we problem solved her all-consuming worries. (Step 1) I started by saying, “I’m noticing you are distracted. What’s happening?” Caitlyn looked down and, welling up with tears said, “I don’t want anybody to die.” I suggested we talk this through so we could both understand the problem she was experiencing.

She continued, saying that the “TV” kept talking about people everywhere dying and that she couldn’t see her friends or her greatgrandmother because she didn’t want to be the reason for her to die. With a bit more exploration, we both decided that people in general—and Caitlyn in particular—had become afraid to leave their homes, go to stores, be around other people... and that meant she could not see her friends, go to school or even see other family members. She was scared.

At this point I suggested we gather some information (Step 2). We listed all the information we could find about the virus, sorting it into categories of health concerns; social concerns; emotional concerns and other factors. (Step 3) Once we had information organized, we looked it over to determine is

some factors might be more important than others. We then generated a list of things we would be sure NOT to do, a list we wanted to do and a third list of possible options.

This produced some criteria to apply to ideas and options, such as “How close to others are we willing to get?” and “What could we do where there were no or few people?” and “What do we feel would be an interesting thing to do?” (Step 4) Now that we had ideas, we began brainstorming and prioritizing which ones we thought would be of interest, fun to do, as well as related to some of the assigned schoolwork.

(Step 5) We chose to go on “field trips” each week. Using our criteria and priority list we decided that a trip to a local fishery would be a good place to start... no one there, outside, can keep our distance as needed, etc. The Shy Beaver Trout Farm was a delightful first trip. We walked about, discussed types of fish, habitats, their growth, the purpose of hatcheries, and more. We developed questions about the hatchery that we would explore upon return home. When we were in the car headed back, we discussed Step 5 and evaluated our trip, both agreeing that it was not only safe, but also interesting and we learned a lot! (ASQ, 2022)

The next trip was a walk in the woods, then a trip to have lunch—following our guidelines. Soon, Caitlyn began to understand

that amidst fears we can approach our concerns openly and come to exercise choices that meet our needs while tending other factors. Our role as educators can make the difference! What this means to our present practice is a shift from a fixed “way of being” to one that explores why things are happening before moving quickly to administering consequences.

Moving to Tomorrow... the shift is to engage students in the process of problem solving

• Step 1: Consciously pausing to identify and define the problem with students. This transparency is critically important and by doing so, you are modeling for students, the thinking and process to solve problems. underlying causes before attempting a solution & consequences

• Step 2: Navigating through the issues to identify the causes of the problem, engages a facilitated conversation with students: “I need your help in understanding why we keep having trouble with this. Let me log your thoughts.”

• Step 3: Keep your eye on the purpose and intent of the work. A collaborative conversation generates possible solutions. There is no judgment on students input. The role of the teacher is to understand the students thinking

around the logic of the solutions. “That’s an interesting thought Joe! I never would have thought of that. Help me understand how you got there?”

• Step 4: Weigh the value and shortcomings of the solutions generated from the students. Modeling critical thinking, helps students begin to develop analyzing skills. “Joelle, what are the pros and cons of your choice?”

• Step 5: With the students, develop a plan on how the solutions will be implemented and when evaluating the success will take place. “Jimmy, what are your next steps and how will you know it is working or not?”

Navigating uncertainties will take time and skill development. Inviting students to learn how to begin to analyze their uncertainties and move from “I don’t know”, or “I don’t care”, to engagement in a process, will lead to a self-directed learner!

The process will require collecting information, gathering ideas/opinions, organizing categories of information, identifying key/pivotal components, developing essential targeted questions to explore, and then investigating options and consequences. Taking time before arriving at a determination will pay dividends moving forward—toward sustainable goals. Efficient

and effective problem solving is a catalyst for perseverance, resilience, and timeless learning--with a huge return on investment. Too much is at stake for YOUR class, YOUR organization, YOUR satisfaction at work... and most importantly THEIR learning. No shortcuts will make the difference!

REFERENCES

Tutu, D and Tutu, M. (2014) The Book of Forgiveness (Audiobook).

Greenleaf, Robert. (2005). “Creating Mindsets: Movies of the Mind.” Greenleaf-Papanek Publications.

ASQ. (2022) The Executive Guide to Improvement and Change, ASQ Quality Press. ASQ Books & Standards | ASQ.

nysascdE-Newsletter

New York ASCD’s e-newsletter has become a valued source of information on national education issues with a New York focus. Topics like observation, evaluation, student achievement, standardized testing, educating the whole child, special education, and communication, STEM, CTE, new graduation requirements, etc. are of interest to everyone and much is written about all of it nationally. Subscribing to our e-newsletter guarantees you monthly insight! Not only is it a place to gain information, we invite all subscribers to submit articles reflecting their thinking and experiences for consideration. The year ahead should be a dynamic one in our state with changes in evaluation again and a new commissioner, to name only two. Subscribe today to keep abreast of what is happening and what people are thinking about!

Efficient and effective problem solving is a catalyst for perseverance, resilience, and timeless learning--with a huge return on investment.

Ownership, Not Fear: Preparing Educators for AI in the Classroom

Tim Dawkins is Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum and Instruction in the South Glens Falls Central School District in Upstate New York. In the past, he has been a school counselor, high school assistant principal, and middle school principal. He also writes a semiregular Substack newsletter focused on the world of education, mental health, and how to build connections to the world around us. You can find him online at https://bio.link/ timothy.

In an always available, increasingly unavoidable, digitally driven world, where artificial intelligence has become an integral part of many aspects of our lives, it is imperative that school leaders prepare our educator colleagues to guide today’s and tomorrow’s students into this AI-dominated landscape. In fact, the speed with which this has become our reality, with large language models dominating the educational news cycles since late autumn, makes this work even more urgent, and the ease with which I’ve worked the phrase “large language model” into regular conversation is startling on its own. So, what does this urgency mean for us? One thing is certain; It necessitates a focus on professional development for teachers and school leaders around AI to foster confidence, reduce apprehension, and encourage ownership of this technology that is not going away.

Understanding the Role of AI in Education

It is crucial for educators to understand what AI is and its potential applications in the education sector. AI involves

AI involves using machines or software to emulate human intelligence, learning from patterns and improving over time.

using machines or software to emulate human intelligence, learning from patterns and improving over time. In the educational setting, AI can be used for personalized learning, grading, identifying student learning patterns, providing real-time feedback, writing IEP goals, and much more. As the role of AI continues to grow, students will not only need to understand how to use AI tools but will also need to develop critical thinking skills to navigate an AI-driven world. Educators, therefore, must be at the forefront of this change, understanding AI not as a replacement but as a tool to augment their teaching practice. The implementation of the The K-12 Computer Science and Digital Fluency Learning Standards in New York State has truly come at the perfect time, and our work around implementation of these standards in public schools puts us at an advantage early on to integrate understanding for our students around artificial intelligence.

Professional Development: Building AI Confidence Among Educators

The key to reducing fear and building confidence in using AI tools lies, as so many things do in education, in professional learning. By developing a comprehensive understanding of AI and its applications, educators can more confidently incorporate these tools into their classrooms. As the assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction in the South Glens Falls

Central School District, I am in a unique position to be a linchpin when it comes to deciding if we are going to embrace these technological advances or foregoing curiosity and exploration to shut down access districtwide. Luckily I work with a great team who are ready, willing, and able to work alongside our staff to help them develop the skills needed to take ownership of this very powerful technology.

Here are some strategic steps that we have encouraged in our school district to foster professional development around AI:

1. AI Literacy It is essential for educators to understand the basics of AI, how it works, and its potential impact. Professional development programs should include AI literacy as a foundational component, demystifying the technology and making it accessible. In South Glens Falls this has involved large group instruction at faculty meetings to provide an overview of what is already out there and what is coming.

2. Hands-on Training After gaining a basic understanding, educators should have opportunities to engage with AI tools directly. Hands-on training allows educators to learn how to effectively implement AI in their classrooms, experiment with different tools, and learn best practices. Our

Director of Technology Integration and Information, an administrative position, and our Technology Integration Specialist, a teacher on special assignment, work together to bring PD directly to small groups and individual teachers. We also have a robust partnership with tech specialists in our region and nationally who can offer support and insight on new and emerging tools.

3. Collaborative Learning Schools must encourage peer-to-peer learning and collaboration whether the tools are digital or not. We know this. Colleagues can share their experiences, successes, and challenges with AI, building a community of practice that supports ongoing learning and exploration. We have created an approach to collaboration and open discussion that we call The Podcast Club where participants listen to a short episode of an individual podcast, usually between 20 and 30 minutes long and then come together virtually to discuss takeaways from the episode. We have found that this, rather than a book study, is a much more digestible way for busy educators to synthesize new information and diverging thoughts than a book study because of its brief and immediately relevant nature.

4. Continuous Support In order for AI to be seen as a tool for us to take control of and not the other way around, schools must provide ongoing support and resources for educators as they incorporate AI into their teaching. Teachers, as instructional experts, should have the opportunity to wield AI technology as they have learned to wield previous iterations of emerging edtech tools. Continuous support may look like easy access to technical support, updated training, and forums for sharing experiences and asking questions with local and regional colleagues.

5. Edtech Partnerships There are many opportunities for schools to partner with emerging edtech companies that are on the cutting edge of AI-integrated tools. In South Glens Falls we are currently partnering with a company based in Norway called Curipod, a tool that helps teachers to build interactive and dynamic lessons, as part of an AI accelerator program. Through building and maintaining professional relationships by attending conferences and saying yes to visits, we have been able to enrich opportunities for students and staff in this way.

Future-Proofing Our Classrooms

As we look ahead, it is clear that AI will continue to shape what happens both inside

and outside our classrooms. We need to ensure that our teachers and administrators are equipped to lead our students into this new frontier. This involves not only professional development but also updating our curriculum and classroom spaces to reflect these changes.

Curriculum and instruction changes should include:

1. Integrating AI Across Subjects AI shouldn’t be confined to computer science or technology classes. Instead, we can integrate AI across various subjects, showing students how it is used in different fields, from healthcare and arts to environmental science and business. Remember that our job in school today is to prepare students with the essential skills to thrive in a world of work that does not yet exist.

2. Teaching Ethical Considerations

As we use more AI tools, ethical considerations become increasingly important. Students should learn about data privacy, bias in AI, and the potential social and economic impacts of AI. Although the technology is easily accessible all around us, we are still in the early stages. There is much yet to be tweaked and perfected, and our students will be the ones engaged in this work sooner rather than later. If they have not

thought fully about the implications of that work, the product will surely reflect that experience.

3. Promoting Computational Thinking

Computational thinking involves problem-solving methods that include expressing problems and their solutions in ways that a computer could execute. It’s an entirely new way of approaching old problems. By promoting computational thinking, we equip students with a key skill for the AI-driven world. Again, in New York State we can certainly look to the Computer Science and Digital Fluency Standards to help guide us in and around the classroom.

4.

Changing What Classrooms

Look and Feel Like We cannot teach new and innovative thinking in spaces that feel like they were put together in the 1900s. Updating how learning takes place in our classrooms is as much about the desks that the work is done at as it is about the work itself. This includes collaborative spaces like libraries, cafeteria, and even hallways, as well. Take a look at your current setup from elementary schools to high schools. Do they look ready to engage learners in 2023 or 1923? If you’re unsure, ask the students directly. They will be honest, clear, and they know what works best for them.

5. Opportunities for Digital Equity

Students with disabilities stand to benefit greatly from ongoing and updated availability of tech learning tools, and the evolution of AI is no exception. These tools have already and will continue to revolutionize how students check their work, receive feedback for improvements, and ask for help. It also gives all families the tools to continue helping their children after the school day is over.

Now what?

Embracing AI in education doesn’t mean replacing educators with machines. Instead, it means using AI as a tool to augment teaching and learning, providing personalized and interactive experiences for students. As school district leaders, we have the responsibility to ensure that our educators are prepared for this AI-driven future. Through robust professional

development, ease of access, and supporting a growth mindset we can reduce fear, build confidence, and ensure that our teachers are ready to guide students into this new era.

Remember, the goal isn’t just to teach students about AI but also to help them understand its impact on society and empower them to be informed users and creators of AI. As we continue to navigate this exciting and challenging world that seems to change right under our feet, our educators will be the guiding force, leading students towards a future where they can use AI tools confidently and ethically. We owe it to society to ensure that we are not merely passive observers but active participants in the AI revolution. Let us invest in our schools, in our educators right now, for they will shape the leaders of our AI-driven world tomorrow, and that affects all of us.

nysascdPartnerships

Click each logo to learn more.

Lexia From acceleration, to intervention, to English Language Development, to assessment and professional learning, Lexia solutions can be used together or individually to meet all structured literacy needs for any student.

PLC Associates PLC Associates is completely committed to working with schools and organizations to achieve results, simply stated. We will stay with you and provide our “wraparound support” in order to get to the target outcomes each school and district designates. The result – we help you actually achieve your student achievement and performance goals. The company has developed numerous proprietary tools © and methodologies used successfully by schools.

New York State Teacher Centers From the Lighthouse in Montauk to the Adirondack Mountains to Niagara Falls, the NYSTC Network is a vibrant collaborative public organization that provides professional learning opportunities for educators. With 125 Teacher Centers and 7 regional networks, the NYSTC Network meets the needs of our diverse student population living in an ever-changing global environment.

SAANYS - the School Administrators Association of New York State SAANYS has a long history of supporting New York’s public school leaders and their communities. Their mission is to provide direction, service, and support to their membership in their efforts to improve the quality of education and leadership in New York State schools.

ASCD Connect the dots to your child’s success with the ASCD Whole Child approach to education.

FACTS about NYSASCD

VISION STATEMENT

• Is a diverse organization with a strong, representative infrastructure and ties to other professional organizations

• Anticipates and responds to needs and issues in a timely manner

• Provides quality, personalized, accessible and affordable professional development services that support research-based programs and practices, particularly in high need areas

• Recognizes a responsibility to identify and communicate the views of members

• Promotes the renewal and recognition of educators

• Supports the development of teachers and leaders, with an emphasis of those new to the profession

GOALS

• NYSASCD will provide research-based quality programs and resources that meet the needs of members

• NYSASCD will ensure that NY’s diverse community of learners is reflected in our programs, resources, membership and governance. Diversity will be reflected in the following ways: board members, association members and committees are diverse in terms of gender, age, ethnicity, region of the state, professional position, and years within the position, with the intention of building the capacity of the organizations

• NYSASCD will influence educational policies, practices and resources in order to increase success for all learners

• NYSASCD will create and utilize structures/tools which enable us to be flexible in our actions and responsive to the changing climate and environment within education

PURPOSES

• To improve educational programs and supervisory practices at all levels and in all curricular fields throughout New York State

• To help schools achieve balanced programs so that equal and quality educational opportunities are assured for all students

• To identify and disseminate successful practices in instruction, curriculum development and supervision

• To have a strong voice in the educational affairs of the state by working closely with the State Education Department and other educational groups across the state and nation.

MEMBER BENEFITS

• IMPACT-New York State ASCD’s professional journal provides in depth background on state and local issues facing New York State Educators

• ASCDevelopments-the newsletter, furnishes timely announcements on state and local events related to curriculum and instruction

• Institutes-two or three day institutes that bring together national experts and state recognized presenters with practitioners to share ideas and promising educational practices

• Regional Workshops-bring together recognized presenters with practitioners to share ideas and promising educational practices

• Diverse Professional Network-enables members to share state-of-the-art resources, face challenges together and explore new ideas

NYSASCD

Over 60 Years of Service to New York State Educators

1941-2023

NYSASCD has provided over 60 years of service under the capable leadership of the following Presidents:

Lance Hunnicut

Fred Ambellan

Ethel Huggard

Lillian Wilcox

Ernest Weinrich

Amy Christ

William Bristow

Bernard Kinsella

Grace Gates

Joseph Leese

Charles Shapp

Gerald Cleveland

Mark Atkinson

Ward Satterlee

Lilian Brooks

John Owens

Dorthy Foley

Anthony Deuilio

Tim Melchoir

Arlene Soifer

Mildred Whittaker

Lawrence Finkel

David Manly

George Jeffers

George McInerney

Thomas Schottman

Helen Rice

Albert Eichel

Conrad Toepher, Jr.

Peter Incalacaterra

Albert Eichel

Robert Brellis

James Beane

Thomas Curtis

Marcia Knoll

Don Harkness

Nick Vitalo

Florence Seldin

Donna Moss

Lynn Richbart

John Glynn

Robert Plaia

Robert Schneider

John Cooper

Diane Kilfoile

Diane Cornell

Marilyn Zaretsky

John Gangemi

Sandra Voigt

Mary Ellen Freeley

Jan Hammond

Linda Quinn

James Collins

Lynn Macan

Judy Morgan

John Bell

Judy Morgan

Brian Kesel

Timothy Eagen

Ted Fulton

Mary Loesing