8 minute read

The DNA of Learning

from Spring/Summer 2023 IMPACT

by NYSASCD

Part III, Requisite 1: Navigating Uncertainties

Robert K. Greenleaf, Elaine M. Millen, and LaVonna Roth

Introduction

Robert K. Greenleaf, Ed.D., has 45 years of experience in education from superintendent to playground supervisor. He was a former professional development specialist at Brown University and an adjunct professor at Thomas College SNHU and USNII-GSC. As President of Greenleaf Learning Bob specializes in strategies for understanding behaviors, learning and cognition. He holds a doctorate in education from Vanderbilt University and is the author of eight instructional books. bob@greenleaflearning.com

Each article in this five-part series will unpack a blueprint for re-starting our passion as educators. The collective series will represent a comprehensive outline of fundamental requirements for timeless learning as we emerge from the COVID ashes and rebuild our lives as educators.

We need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they’re falling in. (Tutu, 2014)

Navigating Through Life’s Uncertainties

Have you ever thought about why some of us can navigate successfully through the unexpected happenings in our daily life? These appear in many forms: a difficult morning…yes, it’s the flat tire as you walk out the door to go to work; the birthday party that was just moved to your house with two hours’ notice; difficult news; uninteresting content with a test at the end of the class; the two-year old’s outburst at the restaurant; forgetting to take the meds and the proverbial badhair day! Navigating uncertain times is one of life’s mainstays.

Elaine M. Millen, M.Ed., C.A.G.S., has over 50 years of experience in education as a teacher, principal, director of special education, curriculum director and assistant superintendent of schools. She has taught at both the undergraduate and graduate levels in both public and private institutions. As an educational consultant and instructional coach, she has worked with hundreds of school leaders across the country and has written several articles on transforming professional learning opportunities for teachers, students and leaders.

Elaine.millen90@gmail.com

Success and confidence depend on developing the skills needed to problem solve for solutions.

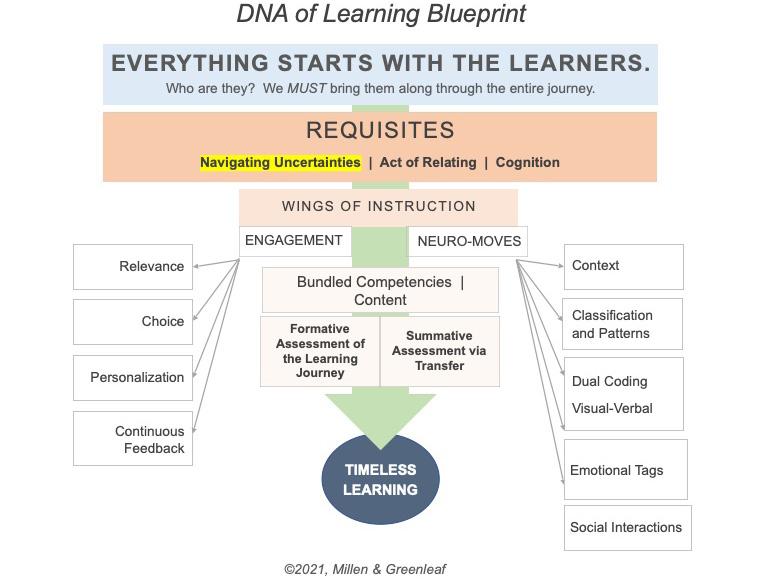

Articles 1 & 2 conveyed that once relationships are mastered, three requisites for purposeful learning can be tackled. Optimal learning depends on competence in the requisites of 1) navigating uncertainties, 2) the art of relating and 3) human cognition.

Navigating Uncertainties

As our life has become more complex, the culture of schools has also been presented with challenges to the structures of the organization as well as to teaching and learning. These uncertainties have increased, coming from conflicting information; differing perspectives; underlying beliefs; novel occurrences and the impact of 21st century unknowns. Navigating these uncertainties will require our schools to focus instruction on the deep thinking around problem solving. Shifting from getting the answer as quickly as possible to understanding and learning the skills needed to solve problems in a variety of settings and contexts is critical for a successful future. In a society that relishes “quick fixes” this teaching will require a focus on essential competencies and big ideas in learning. This shift must become the focus of andragogy and pedagogy.

For several years, we have heard the importance of teaching the next generation of learners the 21st century skills. Many have referred to them as the 4 C’s: critical thinking (problem solving), communication, collaboration and creativity. Teaching these skills to the extent needed for deep thinking and transference, has been undermined by trending programs. We have been wooed into programs with the assurance of anchoring activities to problem solving skills but bypassed organic applications across varied contexts in favor of sanitized weekly lessons out of context. Isn’t problem solving a lifelong competency that everyone—at all ages—and in all walks of life, will benefit from mastering?

If there’s one constant, it is that we will be challenged— often—and in many ways! Some issues will be minor, some substantial. Are all at school taught ways of dealing with interruptions to expected outcomes? When the curtain opens, we must be problem solvers throughout each day, digging beneath symptoms to identify causes. Attitudes, behaviors and struggles in the day’s lesson must first determine if the content is relevant to students. When uncertainties occur, we circle the wagons and engage in supportive problem solving. No child or colleague left behind! Mistakes and challenges are to be respected as opportunities for growth. What is our known, expected response when a disruption happens? When we replace “what is happening?” with “why is this happening?” our disposition toward problem solving shifts.

Coaching Uncertainties

We persistently hear “I don’t know,” “I can’t,” or experience other behaviors that exhibit a lack of capacity to navigate uncertain moments. Building student-managed competencies around identifying the problem and knowing how to begin to address it, will require explicit teaching and modeling. Understanding why it is important to clearly identify the issue, how to begin analysis, and make decisions about options for getting un-stuck are imperative for self-regulated behaviors (Greenleaf, 2005). Front loaded, yes. Saving time in the long run, absolutely!

As we or a student becomes “stuck,” what do we do? Where do we begin? How do we become un-stuck? Often the proverbial carrot or stick is administered. Manipulation/control is used to quell the issue. However, we all know such responses are temporary, unresolved and exhaustingly repetitive. We tell students to problem solve, but do we teach it or model it within context? As a situation presents itself, do we develop a process with the students to ensure transparency? Do we develop a process collaboratively with students, so they understand why the thinking is important? Thus, teachers begin by making their uncertainties public. They have the courage to become learners with the students by stating why the circumstance is troublesome, and modeling how their thinking evolves. Demonstrating with and for learners the process of 1) identifying the pattern that has been interrupted (the perceived problem), 2) why it needs to be addressed, and 3) openly analyzing (unpacking) ideas, perspectives, options, and causes to model ways of tackling challenges.

LaVonna Roth, M.A.T., M.S.Ed. is an engaging and interactive keynote speaker, consultant, educator, and mom. LaVonna bridges her passion for how the brain learns with identifying how every individual S.H.I.N.E.s with their mindset and socialemotional well-being. She supports schools in harnessing the S.H.I.N.E. framework, increasing psychological safety, & building the foundation based on the brain sciences. LaVonna has 3 degrees, is the author of 8 books, and has worked with organizations in the U.S./Canada and internationally.

There are many problem-solving approaches. Most outline steps such as define the problem; gather information; generate possible solutions; weigh each option’s benefits and shortcomings; and then decide, do and evaluate.

Example

As early as five weeks into homeschooling during the pandemic, I saw fear in my granddaughter’s eyes. The barrage of news had already begun to take a toll on her wellbeing. Together we problem solved her all-consuming worries. (Step 1) I started by saying, “I’m noticing you are distracted. What’s happening?” Caitlyn looked down and, welling up with tears said, “I don’t want anybody to die.” I suggested we talk this through so we could both understand the problem she was experiencing.

She continued, saying that the “TV” kept talking about people everywhere dying and that she couldn’t see her friends or her greatgrandmother because she didn’t want to be the reason for her to die. With a bit more exploration, we both decided that people in general—and Caitlyn in particular—had become afraid to leave their homes, go to stores, be around other people... and that meant she could not see her friends, go to school or even see other family members. She was scared.

At this point I suggested we gather some information (Step 2). We listed all the information we could find about the virus, sorting it into categories of health concerns; social concerns; emotional concerns and other factors. (Step 3) Once we had information organized, we looked it over to determine is some factors might be more important than others. We then generated a list of things we would be sure NOT to do, a list we wanted to do and a third list of possible options.

This produced some criteria to apply to ideas and options, such as “How close to others are we willing to get?” and “What could we do where there were no or few people?” and “What do we feel would be an interesting thing to do?” (Step 4) Now that we had ideas, we began brainstorming and prioritizing which ones we thought would be of interest, fun to do, as well as related to some of the assigned schoolwork.

(Step 5) We chose to go on “field trips” each week. Using our criteria and priority list we decided that a trip to a local fishery would be a good place to start... no one there, outside, can keep our distance as needed, etc. The Shy Beaver Trout Farm was a delightful first trip. We walked about, discussed types of fish, habitats, their growth, the purpose of hatcheries, and more. We developed questions about the hatchery that we would explore upon return home. When we were in the car headed back, we discussed Step 5 and evaluated our trip, both agreeing that it was not only safe, but also interesting and we learned a lot! (ASQ, 2022)

The next trip was a walk in the woods, then a trip to have lunch—following our guidelines. Soon, Caitlyn began to understand that amidst fears we can approach our concerns openly and come to exercise choices that meet our needs while tending other factors. Our role as educators can make the difference! What this means to our present practice is a shift from a fixed “way of being” to one that explores why things are happening before moving quickly to administering consequences.

Moving to Tomorrow... the shift is to engage students in the process of problem solving

• Step 1: Consciously pausing to identify and define the problem with students. This transparency is critically important and by doing so, you are modeling for students, the thinking and process to solve problems. underlying causes before attempting a solution & consequences

• Step 2: Navigating through the issues to identify the causes of the problem, engages a facilitated conversation with students: “I need your help in understanding why we keep having trouble with this. Let me log your thoughts.”

• Step 3: Keep your eye on the purpose and intent of the work. A collaborative conversation generates possible solutions. There is no judgment on students input. The role of the teacher is to understand the students thinking around the logic of the solutions. “That’s an interesting thought Joe! I never would have thought of that. Help me understand how you got there?”

• Step 4: Weigh the value and shortcomings of the solutions generated from the students. Modeling critical thinking, helps students begin to develop analyzing skills. “Joelle, what are the pros and cons of your choice?”

• Step 5: With the students, develop a plan on how the solutions will be implemented and when evaluating the success will take place. “Jimmy, what are your next steps and how will you know it is working or not?”

Navigating uncertainties will take time and skill development. Inviting students to learn how to begin to analyze their uncertainties and move from “I don’t know”, or “I don’t care”, to engagement in a process, will lead to a self-directed learner!

The process will require collecting information, gathering ideas/opinions, organizing categories of information, identifying key/pivotal components, developing essential targeted questions to explore, and then investigating options and consequences. Taking time before arriving at a determination will pay dividends moving forward—toward sustainable goals. Efficient and effective problem solving is a catalyst for perseverance, resilience, and timeless learning--with a huge return on investment. Too much is at stake for YOUR class, YOUR organization, YOUR satisfaction at work... and most importantly THEIR learning. No shortcuts will make the difference!

References

Tutu, D and Tutu, M. (2014) The Book of Forgiveness (Audiobook).

Greenleaf, Robert. (2005). “Creating Mindsets: Movies of the Mind.” Greenleaf-Papanek Publications.

ASQ. (2022) The Executive Guide to Improvement and Change, ASQ Quality Press. ASQ Books & Standards | ASQ.