Jason

Jesse

Allicyn

Ekaterina

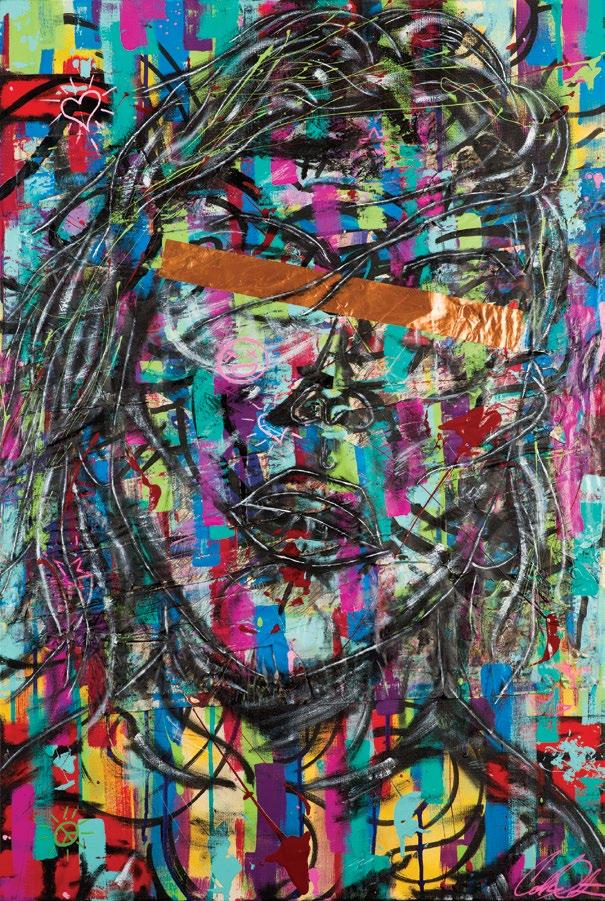

Colby

Jocelyn

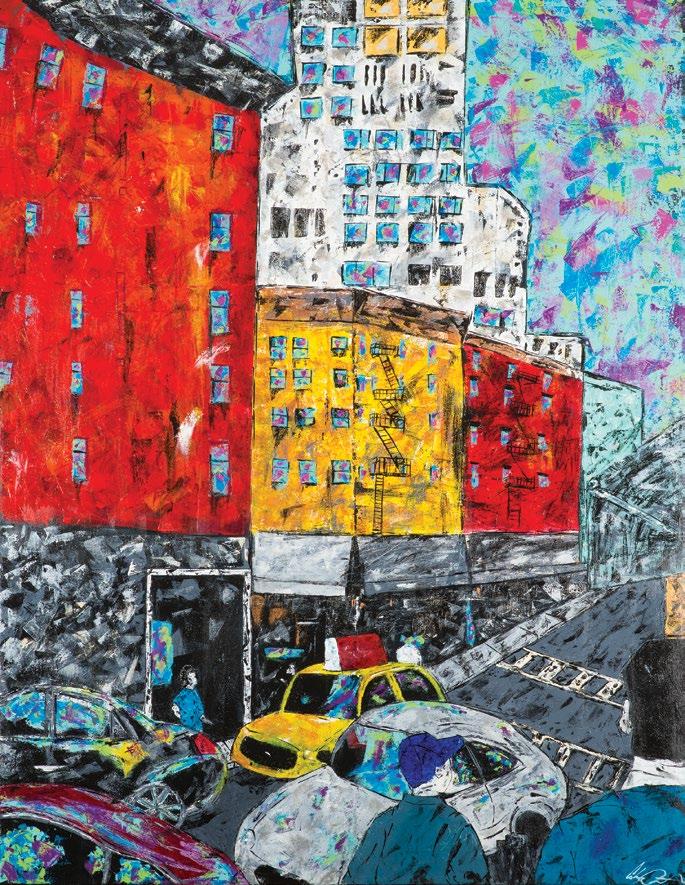

Jason

Jesse

Allicyn

Ekaterina

Colby

Jocelyn

Volume 14, No. 1 Spring 2016

Niceville, Florida

Blackwater Review aims to encourage student writing, student art, and intellectual and creative life at Northwest Florida State College by providing a showcase for meritorious work.

Managing Editor: Dr. Deidre Price

Prose Editor:

Dr. Jon W. Brooks

Poetry Editor: Dr. Vickie Hunt

Art Direction, Graphic Design, and Photography:

Benjamin Gillham, MFA

Editorial Advisory Board:

Dr. Beverly Holmes, Dr. Christopher Snellgrove, Dr. Patrice Williams, April Leake, Rhonda Trueman, and Dr. Jill White

Art Advisory Board:

Benjamin Gillham, Stephen Phillips, Leigh Peacock, Dr. Ann Waters, and K.C. Williams

Blackwater Review Intern: Joshuah Jacobs

Blackwater Review is published annually at Northwest Florida State College and is funded by the college. All selections published in this issue are the work of students; they do not necessarily reflect the views of members of the administration, faculty, staff, District Board of Trustees, or Foundation Board of Northwest Florida State College.

©2016 Northwest Florida State College

All rights are owned by the authors of the selections.

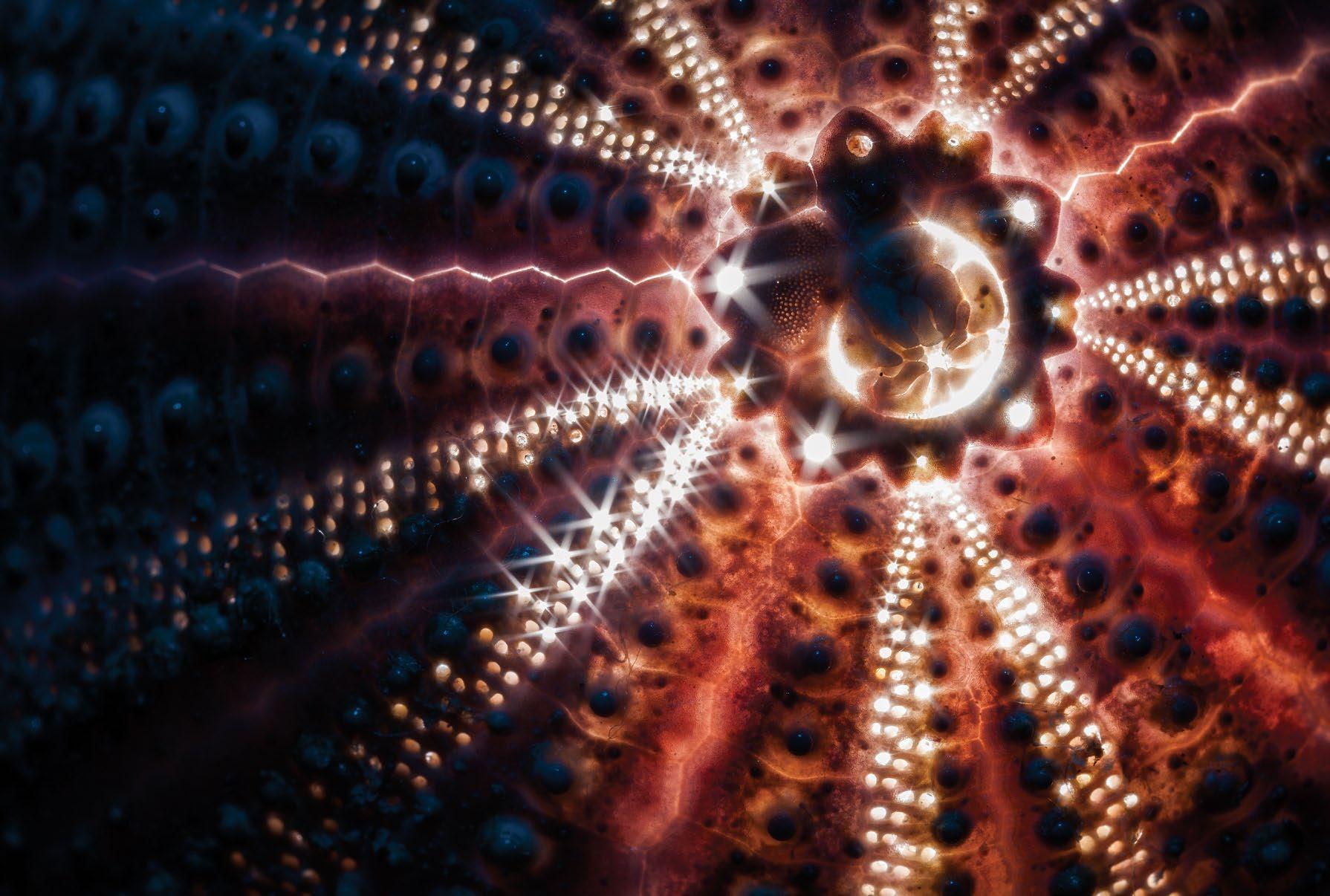

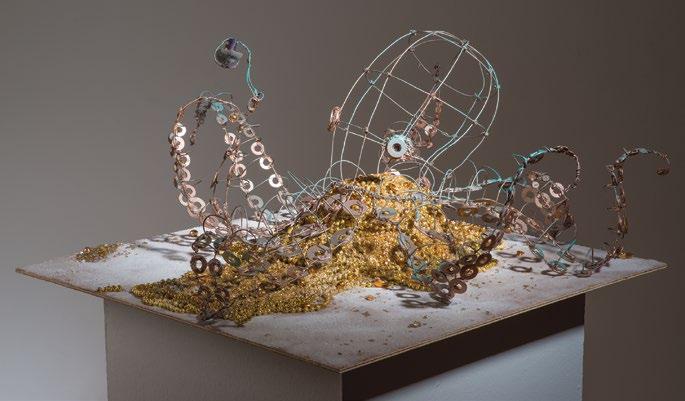

Front cover artwork: As Above, So Below, Candace Harbin

The editors and staff extend their sincere appreciation to Northwest Florida State College Interim President Dr. Sasha Jarrell, Dr. Anne Southard, and Dr. Deborah Fontaine for their support of Blackwater Review.

We are also grateful to Frederic LaRoche, sponsor of the James and Christian LaRoche Distinguished Endowed Teaching Chair in Poetry and Literature, which funds the annual James and Christian LaRoche Memorial Poetry Contest, whose winner is included in this issue.

Jocelyn Donahoo

You could find him sitting on the stump in front of 629 West Virginia Street. Between hocking up spit like lobbing a soft ball, he’d pull out a piece of Tops paper, open his tobacco pouch, take an ample pinch, align it, lick a thick glob of slob, and roll the uneven cigarette. Saturated, it took a few attempts to strike a match and keep the leaves lit.

Like a squirrel, he had a hidden collection of possessions tucked in pockets and places that he rarely shared. He often sat alone, smoking and wearing a beater, but welcomed company when folks strolled by his home. “Al talks about y’all all the time,” he often bragged, about his oldest son, my dad.

Funny, we rarely called him Granddaddy. But he was proud to call me his grandbaby and say, “Come here and give me some shug-ga,” with his raspy voice and rattling cough, cigarette flopping between his full lips. I’d drag my feet, sidestepping a brown bottle, and give him a kiss on the cheek, confessing, “I love you, Mr. Foster.”

First Place, James and Christian LaRoche Poetry Contest, 2016

Jocelyn Donahoo

The three-hour bus ride from Niceville to Selma with a united, multi-racial group turned into a party. I’d never been on a bus that had tables in the back. We played cards, laughed, and joked, and then our tour guide played the documentary Keep Your Eyes on the Prize, the original footage of Bloody Sunday. I felt pride watching the peaceful protestors ascend the bridge, but that feeling was short-lived. My heart pounded, and my stomach twisted as the camera panned the raging officers’ rabid bulldog-like glares. Some were banging their billy clubs in their hands, just waiting. The sudden assault on men, women, and children devastated me. To see people pounded with billy clubs, trampled by horses, and whipped like slaves hurt me. I reached over and squeezed my husband Dustin’s hand. Then I looked around, caught Mama and my sister Bria’s eyes, and they were wet like mine. When I was eight, Eyes on the Prize played on PBS, and I remember asking Daddy, “Why are they doing that to those people?” and when he said, “Because they’re black,” I couldn’t comprehend it then, and I still don’t. We weren’t the only ones disturbed and crying. Everybody on the bus had become solemn, reminding us of why we were on our way to Selma.

In the past, the ride was for voting rights. Now they were trying to revoke that law. The police have gunned down our black men; disparities in employment still exist, and jail and prison terms are unequal. My family had been to the Bloody Sunday Commemoration Anniversary March in the past, but this was the 50-Year Jubilee. Dustin passed our 21-monthold son, Peyton, over to my father. Then he leaned over, bear hugged me, and tenderly whispered, “Aw, Natalie, I know. Don’t cry.” But afterwards, Dustin was squirming. His long legs kept wobbling as if he could run off the bus. Nobody blamed him. The bus dropped us off at Brown Chapel African Methodist

Episcopal Church, but because it was already so crowded, we skipped going into the church and walked around town. The boom-boom of rap met us as we turned the corner. A guy with sagging jeans and an oversized jersey was lining up CDs on his table. He looked up and stared. And I thought, oh here we go. But he nodded and said, “Like your shirts.” Dustin and I smiled and said, “Thanks.” Dustin’s shirt was black, and Peyton and mine were red. A guy with a salt and pepper beard and crisply creased jeans blasted James Brown’s “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud.” Vendors lined the streets selling African masks, canes, necklaces, earrings, purses, dresses displayed on clotheslines, green tee shirts with Reparations, others with “I Can’t Breathe” and “Hands up, Don’t Shoot” and commemorative t-shirts of The 50th Anniversary Selma to Montgomery March. Mama and Bria saw some dresses and earrings they were interested in, so we agreed to meet at the edge of the bridge. People teemed everywhere. They weren’t following the usual protocol. The procedure should’ve been the following: service at Brown Chapel, the dignitaries head up the line, and the rest of us follow suit. But people were already visible on the bridge. Both sides. There was no order.

As we headed towards the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Melissa Harris-Perry, a short little thing from MSNBC, stood in a small barricaded area interviewing a middle-aged nutmeg toned sista’. Farther up, a brown-skinned reporter dressed in khakis and a blue polo shirt poked a microphone toward Dustin and asked, “Why are you here?”

“I’m walking this bridge for my son!” he said, thrusting his chest forward.

“I see you’re wearing a ‘My Color Is Human’ tee shirt. Are you a part of the movement?”

“No, we’re not in any organization. We just believe what it stands for.” I turned around and peeled down my jacket to show him the back that read, “The only way to stop treating people like their color is to stop seeing their color. The only way to stop seeing their color is to stop seeing our own” C. Gray. We got many stares and compliments about our shirts.

About a block away from the bridge, we watched Samuel L. Jackson, Jesse Jackson, and Eric Holder, who attended the Brown Chapel service on the Jumbo Tron. In the meantime, the sun was glaring and hot, not at all what we expected for March weather. Peyton started getting fussy. He was sweating, so I took off his long-sleeved shirt and left on his tee. I dug for his sippy cup of apple juice and handed it to him, grabbed a bottled water, and tossed one to Dustin. He gave me his jacket, and I took off mine and stuffed them at the back of the stroller. The crowd was getting restless. It seemed like twenty dignitaries each gave a thirty-minute speech.

A lady said, “Another one!”

“I know,” I said. “They should’ve given them a five or ten minute limit!”

Somebody said, “Amen,” while others shook their heads in agreement.

Rev. Al Sharpton finally got up to the podium. He hit his stride doing his singsong preaching like in the old black churches. When he finished, Mayor Evans asked that people in the church stay put. Because there were too many people on the street, he’d called the National Guard to maintain order and safety.

Dustin said, “It’s getting late. I don’t know where your family is. Let’s just go ahead and walk across the bridge so we can make it back to the bus on time.”

People walked in all directions: tall people, short people, fat, skinny, big, small. Black people, white people, Asian-Pacific, Native American, Hispanics, and variations of miscegenation ranging from ivory to onyx. A man on a blue electric scooter all but ran me over. An elderly woman with a white, short curly ‘fro and honey toned skin pushed her silver aluminum walker. A tall man with a pecan complexion walked with a curved golden oak walking stick, a group of black Muslims in black suits, white shirts, and black bowties sold bean pies; groups of black fraternities and sororities in red, purple, black and gold, pink and green, blue and white were everywhere. It was so crowded on this bridge; I felt like I was in a school of fish. A 20-something

blond male swung his legs between his crutches. It was nothing for folks to just stop walking, take a selfie, or hold a camera or phone overhead to film the crowd. Natural, straight or curly hair, locks, swirls, cornrows, braids, traditional hair colors: blondes, brunettes, redheads, and some new fads: blue, red, green styles were worn. A little Asian boy in white-framed, mirrored sunglasses looked so cute. A colorful group of nuns, rabbis, priests, and ministers walked by. It had been a long time since I’d seen that many black people, no, “people” in general. They were everywhere.

Dustin’s strawberry blonde hair whipped in the air as he kept scanning the crowd, repositioning, no—posturing, grabbing for my hand or embracing my waist, as if I were a child. I was okay. It felt nice to be around my people for a change. Then I realized he was marking his territory, showing people—guys—that I’m his wife. It reminded me of the time he got jealous of one of my coworkers I was dancing with at a club. When we got home and I angrily rejected Dustin’s drunken romantic moves, he slurred, “I know you want a brotha. You can be mad if you want to, but di-vorce is not an op-tion.” Really? I was about thirty-seven weeks pregnant at that time. I am often in the minority or the “only one” in our social circles, but I’m okay with that. Dustin, who often claims, “I’m a redneck and proud of it!” was obviously uncomfortable. I curled my finger motioning for him to come down to my level and gave him a peck. I wanted him to know that I love him and was proud to be his wife. Everybody looked peaceful despite his or her diverse race or attire. Groups of Asians for Human Rights, LBGT, and Americans with Disabilities holding their banners walked past us. Some people were singing, “We shall overcome,” while others chanted “I can’t breathe”…

Dustin’s response to the reporter kept resonating in my head because it had been a looong time coming.

A few months ago, tired of complaining to family and friends about Trayvon Martin walking home from the store, and Eric Garner being choked down despite calling out “I can’t breathe, who both ended up dead, and somebody’s mother

being beaten like a man by a cop on the side of the highway, and on and on, I, Natalie Pierce, decided to take a stance for all of those injustices. I got an email about a NAACP Black Lives Matter rally regarding Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner at Chester Pruitt Park in Fort Walton Beach on December 13, 2014. When I asked Dustin to join Peyton and me, he said, “I don’t want you putting my son or you in danger. We are not going!” He acted like we’d be facing the haters of the Civil Rights Movement. And before we (Peyton and I) set out to go to the rally, Dustin boomed, “YOU’RE NOT TAKING MY SON!”

His son! Oh, it was on!

I retaliated with, “YOU FOR-BID ME? YOU MUST’VE CHEWED SOMETHING THAT CLOGGED YOUR BRAIN!”

“I don’t want our son in the crossfire of some fool!”

He was being petty and aggravating, so I informed him, “The police are going to be there. You don’t have to worry.”

“I don’t want you to go!” he said pointing his finger.

“Well, you might as well hold your breath and turn blue. ‘Cause I’m going.” He wasn’t going to control me.

“I don’t know why you think you have to save the world!” he said, pointing his judgmental forefinger at me.

“That’s what’s wrong with this society. Too many people are complacent! Just sitting back, not taking a stand, and doing nothing!” Yeah I was doing that angry black woman head and neck rolling as much as I could with Peyton on my hip.

Dustin blocked the doorway and folded his arms. “Leave my son here. He’s too young to understand what’s going on anyway.”

“Move out of my way!” I said with as much authority that I could muster.

He didn’t flinch. “My son stays.” He may as well have banged his imaginary gavel because his words were a judge’s final verdict.

So I readjusted Peyton on my hip, rolled my eyes, and thought about it for a while. I softened my tone and said flippantly, “You can come with me.” I waited for him to hold me in

his arms, peck my lips, and grudgingly say okay.

He didn’t. He gave a pouty frown and said, “I don’t have to show my support by going,” a tad too defensively.

After he trounced on my feelings, I said with strained composure, “Then please move. You’re going to make me late.”

With malevolent eyes and a firm stance, he told, not asked me, “Give me my son.” Too bad the stroller was already in the car, or I would’ve rolled it right over him. I passed Peyton over, and he stepped aside. Towering over me, Dustin said, “Promise me you’ll hold your tongue and be careful.”

Fuming, I held his gaze and sauntered out the door. At the corner of our block, I banged my hand on the dashboard and let out a frustrated squeal.

When I caught up with my family at the rally, my sister Bria blabbed, “Where’s Dustin?” Then she put her hand up in stop mode near my face and said, “Oh, don’t tell me. He can marry a sista’ but won’t stand up for the mistreatment of a brotha’. I guess he forgot his son is black!”

I was already pissed off at Dustin and was itching for a fight. “Don’t fufreaking—I’m not in the mood for your—”

“That’s enough, Bria!”

Thank God Mama interrupted her. Because with the mood I was in, we would’ve exchanged some not-so-nice words, words that almost slipped out and disrespected my parents. Words that would be hard to take back. Or forget! Her ranting was like bedbugs biting me when all I wanted to do was slip into bed, clear my mind, and sleep. I wanted to lash out and smash those reckless sentiments down her throat … because quite frankly, I was thinking the same thing. Where the hell was my husband?

Probably at home trying to make sense of his bigoted family members. Or better yet, trying to justify being married to me with my chocolate skin and bushy hair. Our union did cause some talk among his extended family. Guess they never dreamed he’d meet a sista’ at college and marry her after graduation. His uncle even messed around and jokingly called our son, Peyton, a mutt. It took a while for us to forgive him for

that. Truth be told, it’s been almost two years, and Bria is still holding a grudge. The bottom line, Dustin’s ancestors owned slaves, and he and his parents are ashamed.

I couldn’t stay focused on the speakers at the rally thinking about our argument. I stayed gone from ten a.m. until six o’clock in the evening, trying to excuse Dustin for giving Bria ammunition to humiliate me while failing to support me. When I walked in the door, “You could’ve called and assured me you were okay,” is what greeted me. I threw my hands up in the air. “Why is it every time black people congregate, white people are scared?”

I guess Dustin didn’t think he needed to dignify my question with an answer. He shook his head and said, “Your son is fine. In case you cared to know.”

“Don’t you throw him up in my face! It was your decision to keep him home. And if you were really so concerned about my wellbeing, you would’ve accompanied me. Instead of being scared something might happen!” And with that I went to bed.

Out of the corner of my eye I saw Peyton’s cup fly out of the stroller. I stooped down to pick it up when I spotted Mama, Bria, and Daddy loaded down with bags catching up with us.

“It’s about time! What’s in all those bags?” I asked.

“I had to pull them away, or they’d still be shopping,” Daddy said.

“We’ll show you on the bus,” Bria said. “All of these people—this is crazy!”

Mama said, “We’ve been here several times—”

“And this is the most people we’ve ever seen,” Daddy added. “I’m happy I bought this hat.”

“Yeah, nice Panama,” Dustin said.

Tired of being in the stroller, Peyton reached for his dad, and Dustin lifted him out and toted him on his shoulders. Peyton liked riding up high.

Then Dustin slid Peyton down and said, “Come on son, you’re gonna walk so you can be a part of history.” I was so proud of him, and for that, I leaned over and kissed him, and we shared a smile.

We surrounded them so Peyton wouldn’t be trampled. Like so many others, we took out our phones and cameras and snapped pictures and selfies. A man behind us offered to take a family picture. And we all stooped down closer to Peyton on foot. By the end of the bridge, Dustin was more relaxed and not one person had taunted us about being a mixed couple. It truly was a harmonious day.

Jocelyn Donahoo

Every black man I know has been profiled. You know, DWB or WWB. Oh, you want me to clarify? Driving or walking while black. Hell, just being black!

Yeah, it was wrong for those brothers to burn, loot, destroy their own neighborhoods. But there comes a boiling point. What would you do if for centuries your people were hanged, raped, oppressed? Let’s be real, discriminated against and exploited!

Trayvon Martin rightly hiked home from the store and was wrongly killed by a cop wannabe. Michael Brown flexed and instead of being arrested, ended up in a casket. Eric Garner sold cigarettes— a misdemeanor— but was choked down screaming “I can’t breathe!” He paid the ultimate price, indicative of our lengthy Emmitt Till-like unfair history. What takes the cake is the statement that the officer made. Freddie Gray simply made eye contact and ran.

Sadly, he ended up slammed, complaining of pain, a severed spinal cord, and eventually, a reservation in the morgue.

Black lives matter!

Martin worked for peace. But sometimes, like Malcolm, it takes “any means necessary.” So don’t talk to me about thugs and beasts. It’s easy to judge when some people, my people, aren’t seen as human beings.

Evangeline Murphy

Life isn’t easy, she told me. Mary Poppins never flies down from the sky with her umbrella to help you. You can’t fly away to Neverland And fight captains with only one hand, With little boys running their own carefree kingdom Just because you don’t want to grow up.

Life is hard, she said.

Forest creatures don’t do your laundry or clean your house. You won’t wake up one morning and find yourself a Greek god With super strength and immortality and whatever else Or find a pair of magic shoes that will take you home With just a click of the heels because you’re scared or in trouble. You have to do all that yourself.

Life sucks, she continued. People don’t randomly jump into song. That’s not normal.

There’s no such thing as true love’s kiss, More like a bunch of smooching frogs that definitely don’t turn into princes. No random prince will find you asleep somewhere and kiss you awake To live happily ever after.

If the apple’s poison, you just didn’t clean it well enough, And you were stupid enough to still eat it.

Life is tough, she stated.

If a man’s a “beast,” he’s really just an ass, And there’s no wicked stepmother—that’s your boss. Neither of them will change. A fairy godmother won’t help you get a night off Or turn your old, ’98 Saturn into a golden carriage To meet some prince who never even knew your name.

Life is difficult, she sighed. But you gotta make it worth it. You’re the beauty who doesn’t need a beast. Screw the shoe you lost and just go buy another pair.

Be the evil queen to get what you want. Go live in the woods to find yourself, be Tarzan or Robin Hood Or whatever you want. Sleep forever.

She looked over at me and smiled, Life is definitely not a fairytale, But make it something.

Andrea Hefner

It came with sudden recognition, an announcement grudgingly acknowledged: a bunion, followed by gel toe spacers worn daily wedged between the great toe and whatever that second little piggie is called. Kept in by knee highs worn in lieu of sexy garters and stockings. Sensible comfort. All the while, I attempt to convince my inner being that I have no need to get my groove back. Slipping work clothes off after a long day, my eyes meet yours as I pull my hair up. But we both know that the hanger that holds my negligees has dents in the velvet from the weight of time. I slip on my head wrap and size-16 pajamas, their shot elastic offering relief to the red marks left on my skin. I almost apologize for passing gas as I bend over to slip them on. Embarrassment nearly formulates from some semblance of personal pride, but your hand on my ample backside assures me you have lost any standard of expectations for such formalities. You even swear that conjugal visits are better without the worry of EPTs and pink lines. Later, at 9:23 pm, 12 minutes of time suspended in bliss, I spin my wedding ring on my finger. Somewhere between for better or for worse is the truth of the vows, for mediocrity, for hair dye, college-day visits, empty nests (God willing), and even for orthotics.

Andrea Hefner

Morning light filters into their bedroom, but he has been awake for an hour. The beams stream onto her hair, and he is enraptured by the refraction of the reflection. He lays a hand on her temple and ponders in wonderment at experiences that he was not a part of. Slowly he takes a weathered hand and cups the side of her breast. He feels the lightness and the paper thin crinkling of her soft skin against calloused knotty hands. He marvels at how the time has changed the topography of her landscape. He appreciates the response as she stirs in her early morning slumber and stupors towards the day. He rubs her wrist and examines spots that weren’t there even yesterday. Years have taught him to tread slowly when stoking the fires that she holds within. But he knows that his time is short: he is desperate to show her what he knows to be true: There has never been another woman since her. They say age knows no number, that you are only as old as you feel. He feels every bit of his eighty-three years.

He won’t lie to her and say that he doesn’t notice the silvery stretch marks that run across her belly or how her skin has begun to hang on her once creamy thighs. He sees how her blue veins are right at the surface, and he feels her strong life blood still coursing. He longs to make her understand that while he knows the elderly wrongs that the years have enacted upon them his passion is suspended in the time she made stand still at twenty-seven. He leans over and kisses the small of her neck, that has not changed, lifting silvery strands of hair that she quit dying six years ago. He runs his fingers down her spine. She turns towards him, and he kisses the side of her mouth. There are no children to interrupt, no work to do but this. He feels her smile against his cheek and knows that now is the time to be completely honest. Words are no match for the actions he must pursue. They make love in a place suspended between the heavens, the earth, and even the soul. They pass the remainder of the day hand in hand. As they lay down with the moonlight filtering in through the window, he tells her his secret and cries hot tears with her. They fall asleep together, and as he drifts off, she whispers a prayer for just a few more chances at the morning light.

Jocelyn Donahoo

Funny how people look at me, frowning and confused, when they offer to help and I tell them, “I got this.”

Their intentions to politely push open doors causing missed clearance on my canes, or offers to lift up my walker over a curb, while I’m still leaning my entire body weight on the black rubber tires that rotate, producing a hindrance to keep my balance.

You see I really do appreciate their intended assistance. But I’d rather not fall. I’ve got this.

People talk about me, but I watch my husband take offense when someone volunteers to extend an arm or a hand, open a door, carry my bag, better yet, fetch a chair, while he’s standing right there.

Or my son Armand, when he’s backing my wheelchair up a step on the sidewalk, and someone proposes to assist with the lift. Whether they get it consciously or subconsciously, somehow it’s not perceived as rude or crude, when they too say, “I’ve got this.”

Zachary Thomas

“Stand straight, tall, and proud. Never let anyone see through this guise. Let them thank you for your service and move on. Never speak the truth of who you are or how you feel. Keep it closed in and contained.” Those are the words Marcus O’Malley has lived his life by. Those words have kept him in chains throughout his teenage and young adult life. They have haunted him every time he tried to break away.

Marcus stared out across the room remembering his graduation ceremony from basic training, becoming a soldier, and how it was the first time his father had ever truly been happy to call him “son.” He had lived life trying to be the perfect son: smart, strong, independent, and determined. Hoping it would finally make his father proud, he joined the army, and for once, it seemed he succeeded.

Marcus’s mind flashed back to the late spring of his senior year when his father returned from a trip to London. It was around the same time his older sister, Tabatha, returned from her first year at Stanford, so the house was once again filled with the buzz of her return. Marcus and his siblings crowded her, asking her obnoxious questions about her social life and what she had been doing in her free time, attempting to squeeze details out of her, but she would not budge. Not long after the intense questioning, they were called to their father’s study.

“It took you both long enough,” his father said with his back turned to them. “I have more important things to do than to wait on you two.”

The two stood there in front of his mahogany desk in the center of the dull room. It was a fair-sized room with enough space for a large desk, two brown armchairs facing the desk, a large brown executive office chair at the head of the desk, and several bookshelves and small tables dotting the surrounding walls. The walls held many pictures and random certificates

that were framed, and just behind the desk was the large family portrait, a symbol of everything the family wasn’t: close and together.

Marcus had lowered his head while Tabatha had looked forward at their father. Marcus shifted uncomfortably after moments of silence passed. Neither he nor his sister said a word back at their father for fear of what might happen; instead, they waited for him to proceed.

“Hmph, yes. Let’s get this over with, shall we?” his father said in a cold voice turning to them, pulling out his chair and sitting. “Sit, now.”

The two took a step back and lowered themselves into the brown armchairs. Marcus felt a sense of discomfort fall over him as he sat down into the armchair, his father staring intently at the two. Compared to Tabatha who sat straight up, looking right back at her father, Marcus was terrified and slouched over. Why would he call us here, he thought, what purpose could he have? Fear had already fallen over him, and there was nothing he could do but wonder.

“So, I assume you are wondering why you are both here. The answer is simple; you are the two oldest of my children, and because I refuse to allow my business to fail, it is time to decide who will be the heir to your mother’s and my business after we are gone.” His words paused, looking at the two, his face growing tense, “Marcus, you graduate soon, so what are your plans for the future?”

Marcus sat there, uncertain of what to say. Whatever parts of him that were frozen with fear were now definitely frozen in fear. What was he to say? Tell his father he had no plans? That he didn’t know what he was going to do? Or make up a quick lie and make it seem reasonable and achievable?

“Well, are you going to answer me, boy?”

“I...uh, yes. I’m...not sure...”

“You’re wasting my time then. Get out.”

“I...Father?!”

“Go. Now.”

“Just go, Marcus,” Tabatha chimed in.

“Fine,” Marcus responded.

Marcus sighed as he rose from the bed shaking away the memory. It was just another memory of his father turning him away for not being who he wanted him to be. It made him sick to his stomach. He tried so hard but always seemed to fall short with few moments of success. All he wanted was his father’s approval that it was too late to get.

Walking away from the bed, he made his way to the nearby dresser, pulling out a pair of grey sweat pants. Pulling them on, he looked across the quiet room. It was arranged with a bed against the wall with two end tables on its sides, a dresser on the left side of the bed, the side closest to the door, and a mirrored closest straight across from the bed’s end.

Marcus looked above the bed to the two black picture frames. Both pictures held different meanings with different people: one with a lover, the other a friend; two people for whom he cared greatly. Walking towards the closest mirror, he turned away from them. His eyes gazing at himself.

His eyes finding their way to the bullet scar brought the images of Afghanistan back into his mind. He rubbed the bullet scar on his chest where the Taliban had shot him just inches above his heart. He held his head, his eyes closed as he could feel the bullet passing, feeling the anguish in his heart as it continued into his friend, Stephen, the friend who would never see his wife or child again, the friend whom his secret would die with. The bullet wound would always represent something more; his guilt that it had not killed him, for all he wished was to be free. His whole purpose of joining the military was to free himself from his father’s chains, but he only found he was chained more by some of the guilt, rules, and regulations.

His mind flashed back to a few years ago, just weeks before their deployment to Afghanistan, when Stephen was with him getting settled to deploy. It was a hot day in Southern California, and the two had been driving to pick up some things.

“So, you’re not going to tell them?” Stephen asked as they pulled off onto the highway.

“Tell them, what?” Marcus replied, wanting to act like he

didn’t know what Stephen was asking.

“That you’re, you know, engaged to a guy? Dating a guy?” he said glancing over at Marcus in the passenger seat, “Fucking a guy.”

Marcus let out a sigh and looked out the window and watched the passing buildings. It didn’t really occur to him that he should tell the rest of his unit. It wasn’t their business, he’d always told himself. It was something he only shared with Stephen because of the bond they forged, the friendship they made. Marcus didn’t want the others to know. There’s no telling how they would react or what they would do, and he couldn’t afford to lose their support and trust.

“Well?” Stephen repeated.

“No. I don’t think I will,” he answered.

“Why not? Afraid of what they will say? Don’t wanna be the queer of the unit? The fairy?” Stephen taunted.

Marcus looked over and glared at him. He didn’t care what they would call him; what he cared about is what they would call the man he loved. What they would say, how they would do it, what they may even do to him. He wanted to protect him from that.

“No, I’m not.”

“Then what is it? You can tell me, ya know?”

“I know.”

“Well?”

“It’s about him.”

Stephen glanced back over and gave him a wicked smile, followed by a chuckle. Stephen was preparing to say something, Marcus could feel that, but what he wasn’t really sure.

“Worried about Pretty-Boy, eh? He can take care of himself; I’m sure he’s been through worse than you have about all this. I mean he grew up out to the world. You haven’t. I’m sure he’s had a black eye or two because of it.”

“I just don’t want them abusing him, if they knew.”

“Of course.”

Marcus scoffed at himself, looking away toward the nearby window, sunlight starting to pour into his house in the

quaint little neighborhood not far from Fort Drum, New York. Marcus cast his gaze back to the moving body in the bed, trying desperately to get comfortable again; he couldn’t help but look away in shame. His partner had given everything up for him, changed his entire life for him, and dealt with the idea of not being recognized by any except certain family. Yet he still felt that he had to hide their relationship from so many, for fear of judgment.

He lived with the constant idea that his father and society would disapprove. It always lingered in his mind, he would always be a son wanting approval, a person wanting approval, and this was always one thing he felt his father would disapprove of more than anything else, something that would make his father so disappointed.

Marcus looked over to the bed again trying to shake the feelings of disapproval from his mind. His gaze once again caught the sleeping body of his beloved partner, Andrew. Andrew was a smart, kind, compassionate person who cared deeply enough for Marcus to leave his job and family behind and move with Marcus from base to base, always living in the shadows, only revealed to some, and that’s what hurt Marcus most about this situation. He was so willing to not be known to the world because of how Marcus felt about it all. Marcus knew that Andrew knew that he loved him, but he always knew Andrew deserved better. However, Andrew always reassured him how much he loved him, and no matter what, that he was staying with him until the bitter end, and in a way that willingness gave him a sense of hope.

Marcus faintly smiled as he looked back to the picture right above the bed on the right, hanging over Andrew. It was the picture of them a few years ago, taken on the day Marcus had come back from a deployment. Andrew had shoved himself into Marcus’s arms when he walked through the door of his apartment, his face buried in his chest. The feeling was mutual as Marcus almost refused to let go of him.

“I missed you so much.” Andrew said looking up at him. Andrew was the smaller of the two, only 5'8" compared to

Marcus’s 6'4" height, which in a way was a charm of Andrew that Marcus loved.

“I missed you too, Little Cub,” he replied picking him up in his arms.

Marcus held him in his arms for a long time before finally kissing him and putting him back down. He looked down at Andrew and couldn’t help but smile like a fool. The two of them seemed to just forget about the rest of the world at that minute, taking each other back in.

“I missed you,” Andrew said again leaning up and kissing him again.

“And I missed you.”

Andrew took a step back and gently smiled at him. He reached to take the bag that had been dropped on the floor, before being stopped in his tracks.

“It’s fine; I will take it. Don’t trouble yourself with it.”

“Come on; I’m not that weak. I can take a bag and move it upstairs.”

“I said I will take it.”

Marcus looked down at the now scowling man, whom he couldn’t help but laugh at a little. Andrew was stubborn, incredibly stubborn when it came to wanting to do something. In a way, Andrew hated being told no, or that someone else would take care of it. It was something that Marcus loved and hated about him because it could get annoying, but it also was adorable in moments like this.

“Hmph. Suit yourself then,” Andrew replied turning away from him and looking the other way.

“Oh, come now, don’t be that way.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“I’m sure…”

Marcus crept forward flinging his arms around Andrew, holding him in close.

“Let go of me!” Andrew pleaded.

“Not happening,” Marcus replied.

“Ugh, I hate you.”

“You love me.”

“Most days.”

Marcus smiled and finally let him go, turning him around to look at him in the eyes again. He took Andrew’s hand and led him to the nearby living room, which didn’t seem to have changed much. He sat down on the couch leading Andrew to do the same. He looked at him, leaned forward, and kissed him again before pulling away.

“So, how’re you? What’s been happening?” Marcus asked.

“You get back, and you want to know about me? I think it should be the other way around, honestly. But if you insist, I got accepted to continue my medical residency nearby.”

“That’s great. I’m very proud of you.”

“Of course you are!”

Looking away from the picture, Marcus smiled back at Andrew, who was sleeping peacefully in the bed. It was time, Marcus thought, it was time to make the change. He was ready; he was going to be ready. It’s time that it happened, that the world knew about Andrew.

D.L. Thornton

The putrid stench of the train’s coach car toilet bowl filled my nose, as I knelt, fingers poised to probe my throat again, above it. Why can’t I puke? Please God, just let me puke. I had always heard of motion sickness, but I could never have dreamed it could be this bad. Tears streamed down my face from gagging, but I just couldn’t vomit. It was awful, and no matter what I tried, it just got worse. Ok Ezra, You can do this. Just think of everything that’s happened in here. All the disgusting, rotten things that have…that have happened…

“Don’t let them bury me, Ezra.” My mother’s voice filled my ears, and I closed my eyes.

“Please, I know I haven’t got any right to be putting this all on you, but do me this one last kindness,” my mother said, her voice hoarse often pausing to cough in between words; from beneath the shroud cast over her off the light from the window, the light of a world just given away to the night, the words rose into the stagnant, dusty air. The sight of my mom, decrepit and fragile, surrounded by her moth-eaten quilts in a simple homespun gown, stained with sweat and the morning’s grits, stirred a profound sadness in my heart. The sallow skin, the knotted, thinning mess of hair haloing her head, and shuddering movement of a skin and bones hand reaching for a handkerchief on the bedside table, in an attempt to preemptively suppress a coughing fit.

Her frail body was racked with a string of violent coughs, the sound of which filled her modest bedroom of our house. Insistently, she tried to continue speaking but couldn’t manage to stop long enough to talk.

“It’s ok, Mama. I heard you,” I said trying to hand her a glass of water. “Drink something. It’ll make you feel better.” She reached for the glass, still coughing, and spilled more than a little before managing to down a couple of swallows.

“Thank you Ez. I—I needed that,” she said, her voice catching about halfway through. I couldn’t help but notice how carefully she was folding the handkerchief, trying to hide that it was now stained pink with her blood, but it didn’t matter. Despite her efforts, I could see a few drops mixed with the stains on her gown. “It’s just, you know how much I abhor tight places and the dark. The idea of being trapped in a box underground for…well, for forever is more terrifying than dying itself.”

“But you’d be gone, Mama. You wouldn’t know anyway.” I said this despite the fact that the words nearly killed me, too. I was being strong for her, but the idea of losing my mother was too much to fathom.

“Yes, I would. Whether I end up in heaven, hell or experience nirvana, I’d know.” Her eyes grew distant as she went on. “Even if all we do when we die is vanish to nothing, I still feel like I would feel it somehow. No, I wasn’t meant for the coldness of the ground. I want to be cremated. You know as well as I the power fire holds. The purity it grants.”

“I do.”

“After all, fire is life. It’s born. It feeds.”

“It grows, and it dies,” she smiled as I finished one of her favorite sayings. My voice broke on the last word, and I looked down at the once-white carpet to hide my tears from her. Hot tears burned rivers of fire down my cheeks. I heard the bed shift as my mom rose to place her hand on my shoulder.

“Ezra, listen to me. I know this is hard, and I know it seems impossible and unfair, but it’s going to be ok. People die, even the ones we love. It’s the single absolute of our existence.” She squeezed my shoulder slightly. “It’s normal to be sad, to mourn, but promise me that, when I’m gone, you, celebrate the life I had.” Her voice was still soft, as if she feared raising it too high would induce more coughing.

I turned my head toward her, slowly lifting my eyes to meet hers. Her hand moved to my cheek as I did, her thumb stroked the side of my face gently.

“Can you promise me that, Ezra?” she asked.

Opening my eyes, I saw the warm intensity in her gaze.

Her green eyes, once glazed over in thought, were so vibrant, so young. Looking into my mother’s eyes, I almost forgot that she was sick. How could those eyes, those resilient knowing eyes, be in such a decrepit body? She was right; it wasn’t fair. Not in the slightest. How could this be happening to me? Things like this never happened in real life. I was spinning out of control. My eyes began darting between my mother’s eyes. Back and forth, from one to the next again and again. Blood rushed to my head. I could hear the dull thud of my heartbeat in my ears.

Thud. Thud.

“Promise me. Ez.” Her voice was stern, full of a strength I had missed from her, and the grip on my face grew ever so slightly tighter.

Thud. Thud.

I took a few deep breaths.

Thud. Thud.

Nodding as I said, “Yes, I promise.”

Her thumb ran across my cheek one last time before she smiled and leaned back into her cocoon of blankets, “That’s my girl.”

Thud. Thud.

“Miss.” A man’s voice called from outside the bathroom.

Thud. Thud.

“Miss! Ma’am, I am going to have to ask you to vacate the lavatory as soon as possible.” His voice seemed frustrated with a hint of worry.

“I’ll be right out.” I said, flushing the toilet for effect. I rose to my feet, nearly falling back down still gripped by the vertigo. I washed my hands and face in an attempt to rinse the signs of crying away, but as I did, I knew it was no use. Still red and swollen, my eyes would give me away instantly. I took a few deep breaths before opening the small bathroom door. I didn’t think it possible, but the sight on the other side of that door made me feel worse.

The young porter stood next to the doorway of the bathroom with an anxious looking pregnant woman next to him.

“There you are, Ma’am,” he said gesturing to the open doorway before turning to me.

I had barely gotten out the word sorry before the woman barreled past me and shut the door.

“I am so sorry for that, Miss, but she was very insistent. Are you doing okay? You were in there quite a while, and your color seems a bit off.”

“Thank you for your concern, but yes, I’m fine.” I said “Well, if you need anything, I will be around, and please don’t hesitate to ask,” and with that he was gone, walking off towards the next train car.

I wonder if he even really cares, or, if like the woman now in the bathroom, he simply did enough to sate the urge. Genuine concern or employment obligation? In the end, I didn’t really care either way.

Trying with all my might not to look out of the windows on either side of me, I slowly made my way back to my seat. The sight of the rushing landscape intensified the vertigo by a power of ten, at least. Even staring at the ground, though, I couldn’t shake the feeling. I decided to take a break and just stand for a bit. Grasping the side of an empty seat, I stopped and closed my eyes.

“Attention all passengers; this is your captain speaking. We will soon be approaching a tunnel. We will be traveling for about fifteen minutes underground, and your ears may pop due to the pressure change,” a tinny voice rang from the intercom system.

I opened my eyes. The few others in the car seemed to buzz with energy. Most reacted excitedly, but one man seemed nervous. He was gripping the arms of his chair so firmly that I could see the tendons in his white knuckles straining. The look on the man’s face as he shook his head exuded terror. I could tell he was trying to contain it and failing, but the woman next to him, his wife maybe, had a hand over one of his, and was speaking softly to him, but he kept shaking his head.

I couldn’t hear everything, but a few phrases managed to pierce through the residual train noise and reach me. “Shh, it’s okay—” Muffle. Muffle. Muffle. “No, just try and—” Muffle. Muffle. “It’s only a few minutes, just—” Muffle. Muffle. “It’s only temporary.”

“It’s only temporary, Soph. Besides, Kevin’s a great man. I’m sure you’re exaggerating,” my father said, talking into the phone.

I was standing there, hiding just outside the kitchen, the shadows of the dark hallway concealing the sight of me from my father, who sat at our maple breakfast table. It was initially the sound of my father’s voice, which had prevented me from simply entering the room, but it was well past midnight, and the last time he had caught me out of bed at this time of night it hadn’t ended well.

“The fact of the matter is I can’t support her, and our brother can’t help, Sophia.” There was a pause.

“No, I’m not just trying to palm her off. I just—I know I can’t do right by her. I can barely look at her without wanting to die myself. There’s so much of Violet in those eyes.” There was a hollow quality in his voice as he said those words, a sadness that was both foreign and familiar to me.

A pause.

Did Father not want me, not love me, anymore?

The wooden floors of the hallway, worn smooth with years of use, were cool on the bottoms of my bare feet; I tried with all my might to disappear into the wall, making myself as thin as possible. I wanted to simply vanish into the wood of the wall, and not have heard what he had said.

“Yes, I still love my daughter! What the hell kind of question is that?”

A pause.

“It’s not forever, Sophia, just until I can get my life back together. Once I’m back on my feet, she’ll be back here with me.”

In those moments, I understood that my father, as much as it pained me, was right. I had noticed how he would look at me sometimes. How his eyes would completely sink and his face would melt for a few seconds at the sight of me, only for the briefest of moments, before being replaced by the strong front that I was used to.

I was frozen. I wanted to rush back up to my room and pretend to be asleep. No, to actually be asleep; I wanted to

never have left my room. This doesn’t make any sense. But it does… it makes complete sense; you just heard him explain it, hell, you agree. But… no that wasn’t him; it wasn’t. Aunt Sophia was right to question him. He’s not thinking clearly. He can’t be thinking clearly.

“Ezra!” my father shouted in surprise. “What on earth are you doing out of bed?”

The shock of seeing him suddenly there, BAM in from of me, made me scream without realizing it. Then I was in motion. My once-frozen limbs were all at once a blur of motion. I was running, running down the hall and out the front door. I kept running long off our property. I ran down our driveway and out into the street, only stopping when I reached the stop sign at the end of our street.

Breath ragged, I stood doubled over in pain, one hand on my knee, the other clutching the stich in my side. The pain and shock mixed inside me. Colliding in my abdomen, they began a battle inside me. I could feel my stomach turning, roiling. My throat constricted, and I could feel the low acidic burn of bile rising in my esophagus.

I collapsed to my knees, and in five gut wrenching heaves vomited onto the carpet of the train.

“Oh my God. Really?” a nearby woman groaned as she rose from her seat.

Shaking, I knelt there, hands covered in the contents of my stomach. I’m not sure how much time passed, but it seemed that instantly the porter who called me out of the bathroom was herding people to the cars to either side of ours.

“Just until we clean this up. Don’t worry, won’t take ten minutes,” he was saying to everyone as they passed him.

I began to pull myself together. Struggling to my feet, I headed towards the bathroom again to rinse off the vomit from my hands. It was a difficult feat because I didn’t want to touch anything along the way, but I came to the same problem at the door of the bathroom.

“Do you need help?” It was a young boy; he couldn’t have been more than six, and he was standing beside me pointing at

the door.

I gave him a small smile and said, “Yes. Yes, I would like that very much.”

Grinning, he reached up and opened the door, pulling it with both hands. The sight of him, so willing, so eager to help, warmed my heart. I stepped into the bathroom, turned on the water with my elbow, and washed my hands. The warm water cascaded over my hands and forearms in rivulets of soapy purity.

Stepping out of the bathroom, I saw the boy still there. “Oh, hi. Thank you very much for your help. I’m Ezra,” I said, extending my hand to him.

“Hello. My name’s Harry. I’m four. Me and my mommy are going to visit Grandma in the country.” He said this as a worried woman rushed up to us and picked him up.

“Harold Bloom! Don’t you ever run away from me again! You had me worried sick,” the woman, his mother, said as he fought to break out of her grip. She struggled with him for a moment before she began to hum mindlessly.

I didn’t recognize the tune at first. It wasn’t until the end of the first verse that I finally placed it: “The Wheels on the Bus.” At the end of the verse, Harold was still fighting against his mother, but she began to walk back towards their seats. Was I that innocent, that pure ten years ago?

I followed them, not really knowing why, but I needed to follow them. I sat two rows behind them as Harry’s mother’s voice rose from her humming.

“What do the wipers on the bus do, Harold? What do they do?” she asked him.

“They go back and forth. Back and forth all through town,” Harry said, calming down enough to respond, but still not giving up.

“That’s right,” his mother agreed, “They go back and forth, back and forth…”

Back and forth.

Back and forth.

I had grown to hate that lake. Uncle Kevin forced me to

go out in the boat with him a few times a week. Every time we went out there together, it was a little worse. It always began the same way. We’d get in the boat, the hard wooden bench hurting me as I sat. Uncle Kevin would look at me, a frightening look in his eyes, and he’d slowly row us out into the lake. The oars moved back and forth in the water. Always back and forth, cutting in and out of the water.

Even after we stopped in the center of the lake, I would close my eyes and imagine the oars still moving. Pushing, pulling, moving back and forth, and cutting in and out of the water. Instead of the leering glance of my uncle. The malicious intent behind those eyes. His rough, calloused hands grabbing, pulling at me, my clothes.

The carnal need to resist, to fight back, nullified by the memory of that first time. The anger that flared up. The hands that turned to fists and stuck out, full force, at my head, chest, everything in reach until I—No…

Just think of the oars, of their power over the water.

The cold, dead water. Existing under the guise of bringing life, facilitating growth, but suffocating, smoothing, dousing all in its path. How I longed to wield the control those simple tools inherently possessed.

It was the fourth time he had taken me out on that wretched lake that week, and it would be the last. That boat ride, like all the others, became a sad, painful blur when I tried to remember it in the safety of my room, but one thing was for certain. I was never going out on the lake with him again, and I couldn’t stay in this house one more night.

Who are you fooling, Ezra? Where would you go? Home? Don’t you remember why you’re here in the first place?

“Damnit, Ezra! If you don’t get your ass down here and tend to the fish I put on! I want to shower before dinner.”

Hoping against all odds that he would drop it, I didn’t move. He’d let me recuperate in peace. I had locked my door, just in case anything escalated.

Minutes passed in silence. I almost began to believe it; maybe a semblance of a heart was forming in the chest of

that—the doorknob jostled in its place angrily. BANG. BANG. BANG.

“You’ve got ten seconds to get out here Ezra.” I wanted to move even less after those words. His voice was calm but cold. Smooth, thin ice that would soon break and give way to the torrent of rage just beneath the surface.

“I was just changing. I’ll be right there,” I said rising hurriedly to my feet and making an audible fuss near the small closet. His only response was to slowly tread away toward his bedroom.

My knees collapsed underneath me, and before I knew it, I was softly sobbing on the floor. My chest heaving with my broken breaths, I forced my way to my feet and made my way downstairs. As I neared the kitchen, a chill ran through me, returning the heat to my hands and face.

The following hour or so became a haze of flashing memories, but before I knew what had happened, it was too late. I was already stirring the pills into the quickly thickening box of macaroni and cheese.

Hands in my pockets, I clenched the money I had stolen from his nightstand. I tried to convince myself that he would be fine. They were only a couple sleeping pills and some laxatives, I thought. He won’t die… I just don’t want him to be able to follow me. I began to walk away. Into the darkness. Into the future.

Where are you going? I kept asking myself, but I never came up with an answer.

“Attention all passengers. We will be a arriving the next station in about five minutes.” The captain’s tinny voice said through the intercom.

“Come on, Harry. This is our stop. Don’t you want to visit grandma?” the woman said still holding the fussy child.

“Grandma!” Harry said, excitedly wanting to get down.

The pair of them gathered their things from overhead and headed toward the nearest exit. I watched them go, almost wanting to go with them, longing for the normality of their lives. I sat in my seat staring in the direction that young Harry and his mother left, until.

“Ma’am? Are you feeling better?” It was the porter. The same one who had pulled me out of the bathroom earlier.

“Um,” I actually hadn’t thought about being sick since I met Harry. “Yes, I feel- much better.”

“Well then, is this your stop?” he said a smile stretching across his face.

“No, not quite yet, thanks. I’m not sure what my stop is actually.”

“Well, where are you heading?”

I turned away from him, not answering his question. I wasn’t trying to be rude, not really. I just didn’t know. I let my gaze absent mindedly trace the rushing landscape, and felt the traces of vertigo returning. Trying to minimize the spinning that had already begun again, I quickly shut my eyes and put my head in my lap. I should just stay on this train. Going on and on like this…forever.

“Miss? Miss, are you sure you’re all right?” he was still there. This stranger who was so concerned for me. Why?

I looked up at him, ready to reply that I was, and that he could leave, when I saw his eyes. Soft, green eyes.

Like mine. Like…

In those almost familiar eyes, I saw earnest emotion. Those weren’t the empty eyes of someone simply doing his job, not the leering gaze of someone with ulterior motives, nor the sad gaze of someone looking on with pity.

He really wants to help me.

“I’ll go and fetch you some water. I won’t be a minute.” He began to turn, heading away, but I reached out and held his forearm. Grasping the cloth of his uniform in my hand, I waited for his eyes to return to mine. I needed to be sure. Had to be certain of what I had seen.

As the warmth of his gaze fell upon me again, I saw the hints of a questions there, but still the soft concern I had sensed before. But there was something else now as well. They were sharper, more determined.

“Is there something else I can do to help?

I hesitated.

“Yes, yes there is. Is there a phone on-board?”

He answered my question with a nod.

“Could you take me to it, please?”

“Of course. Right this way,” he said, a small smile returning to his face.

Walking slowly, eyes half closed to minimize the rushing view of the landscape on either side, I followed him down the car and past the bathroom. He led me to the train’s dining car, where there were two phones at either end.

“Thank you,” I said picking up the receiver and starting to dial, “and you don’t have to get me that drink. I can get it on my way back to my seat since I’m already here.” He just nodded in reply because I had finished dialing and was waiting for it to ring as I said this. I just watched him walk away. I wasn’t sure what I would say. I didn’t really have a plan; I was just kind of...

“Hello. Hello, is someone there?”

“Dad.”

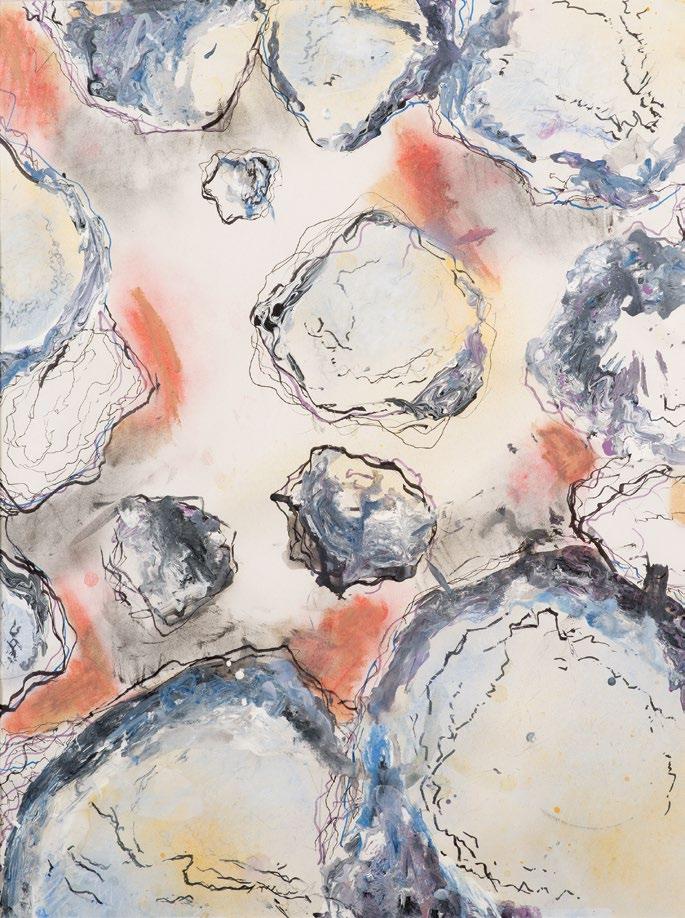

Allicyn Baldwin

Dear Jake,

You left some things behind when you died— that old pillow, your smelly, holey blanket, a few pictures, hundreds of short hairs, and me.

You left an empty space in my bed that no amount of bubble bath or tea could possibly fill. Sleep still refuses to come for me.

But though you have died, your ghost lingers, an unseen hand that guides and protects. I can practically hear your soft footsteps beside me.

You would not want me to be crying, hunched up in the shower, shampoo forgotten. You would want me to remember summer and you.

You would not let me close my door and sit in bed alone, losing track of days. You would want me to go outside, take a walk for you.

Though you have died, my dear one, I know that you still love me. I know you forgive me, and you’re waiting for the night I once more sleep beside you.

Until then, Allicyn

Raisin wrinkled skin is what we find, pulling off our wet socks. Wet, from the puddle, that had looked so tempting to splash in.

Tempting then, regret now, like a slice of cake eaten without permission only to be caught with the crumbs on our shirts later.

Raisin cookies are what Jace and I would find, if we were entering my grandmama’s kitchen even with the mud from our wet rain boots tracking sloppy prints on her clean linoleum.

However, this is not Grandmama’s kitchen, and cookies are not what greets us.

Raisin colored bruises are left on our skin. Jace and I blink back tears in the bathroom where we sit, peeling off our mud-caked rain boots and wet socks to reveal raisin wrinkled skin.

Jocelyn Donahoo

It was my decision to write a quick revision. It shouldn’t take but a minute or two. But if you’re a writer, well, you know that minute … it overlapped, and trampled my vow of “dinner will be ready in an hour.”

The problem is the voices keeping up with the voices. A hungry mob chanting, they can be distracting. They crowd my head, pushing and shoving, each and every character wanting the spotlight of attention. Unlike some writers, I don’t outline. The characters dictate the plotlines I create. They force me into the zone. Not the Twilight, but the artistic, imaginative up to three—four—five a. m.

Keys can be heard pecking, computing: wisecracking, face slapping, roving over ruddy clay roads, heart pounding, hairs rising on the back of the neck, breathtaking views of a luminous red maple tree, tears trailing down pudgy cheeks, a kid smiling with jack-o-lantern-like teeth, type verses and scenes.

So I guess I just need to answer their bidding. And let the words flow freely. Without guilt or penalty.

Morgan Masek

Hey Imagination,

Can you finally come up with something for me?

I’ve been sitting here for hours staring at this barren page. That black bar has blinked three hundred sixty-two times, On this void, which I have mistaken as a mirror, For I am sure it reflects the blank stare on my face. Despite it being digital, I can hear the clock ticking, What I should be hearing is the clicking of the keys, On my keyboard and seeing letters appear on the screen, Of light that feels like a strong fan blowing directly into my eyes. Yet nothing comes to mind.

Is your fuel tank empty? Should I go to a gas station? If it’s rest you need, well too bad, I need a poem now. You were working fine this morning! The images in my head were vivid, bright and alive, You could have painted a masterpiece painting, That could have been hung in a museum with a golden frame, In the hallway with exotic, high-priced, oil-splattered canvasses. But no, when I most needed the masterpieces you could produce, You leave me with this vacant space while I’m drying out my eyes staring, hoping that somehow words will magically line themselves, In rhyming, flowing orders of vague phrases, that one could call poetry. However, alas, I stare and chew on my fingernail, Trying to pull out something before the deadline, Without your damn help.

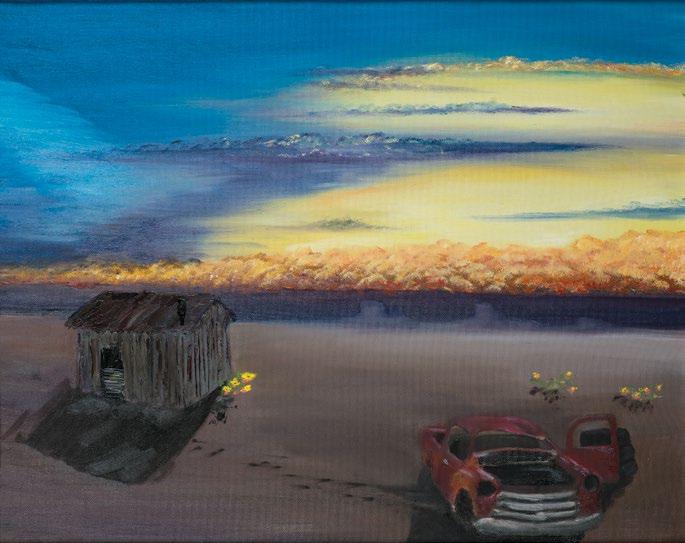

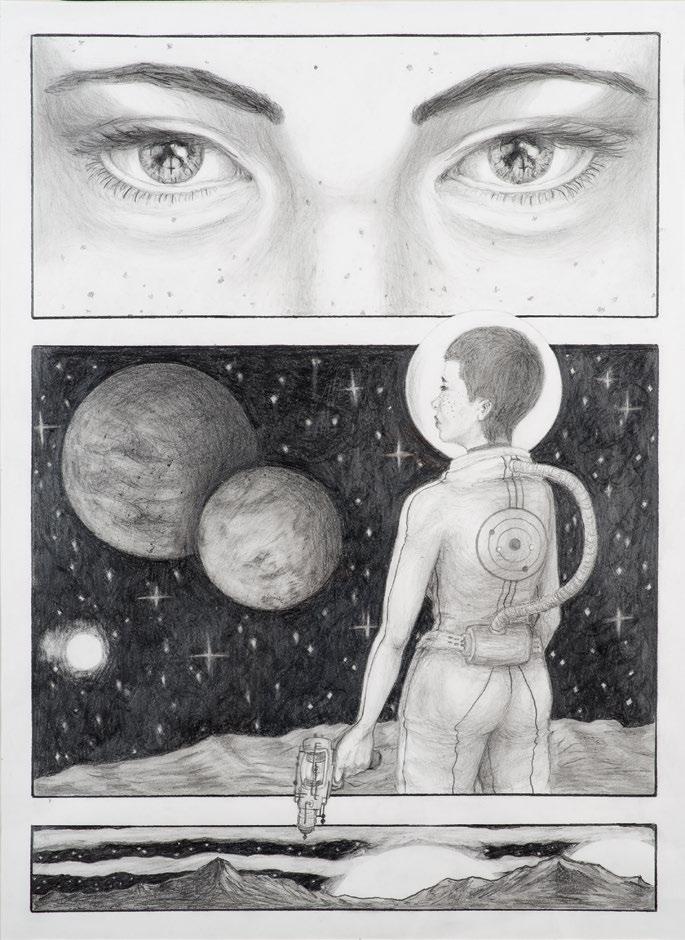

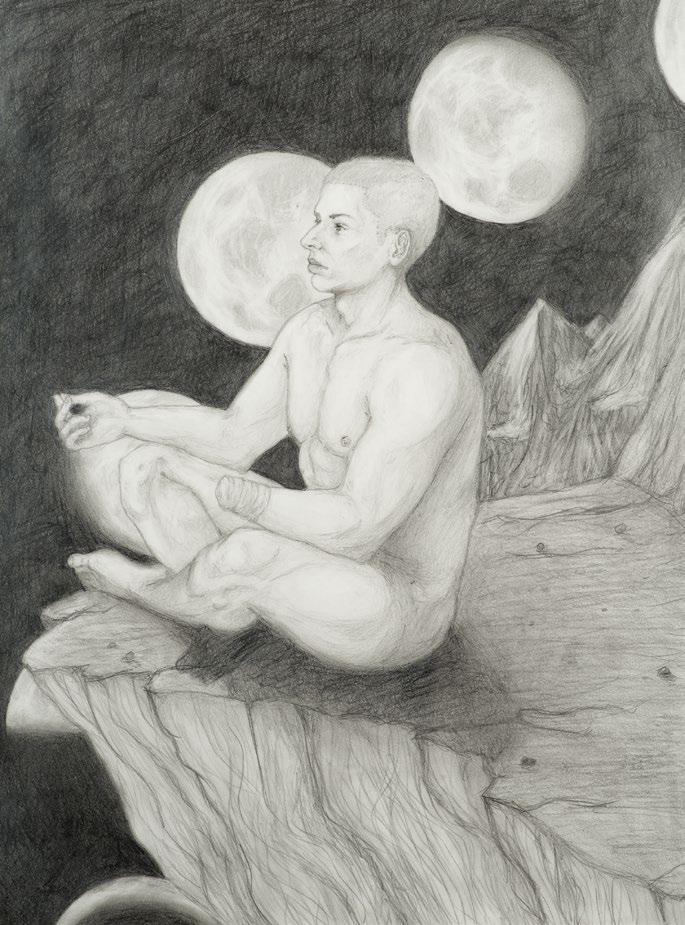

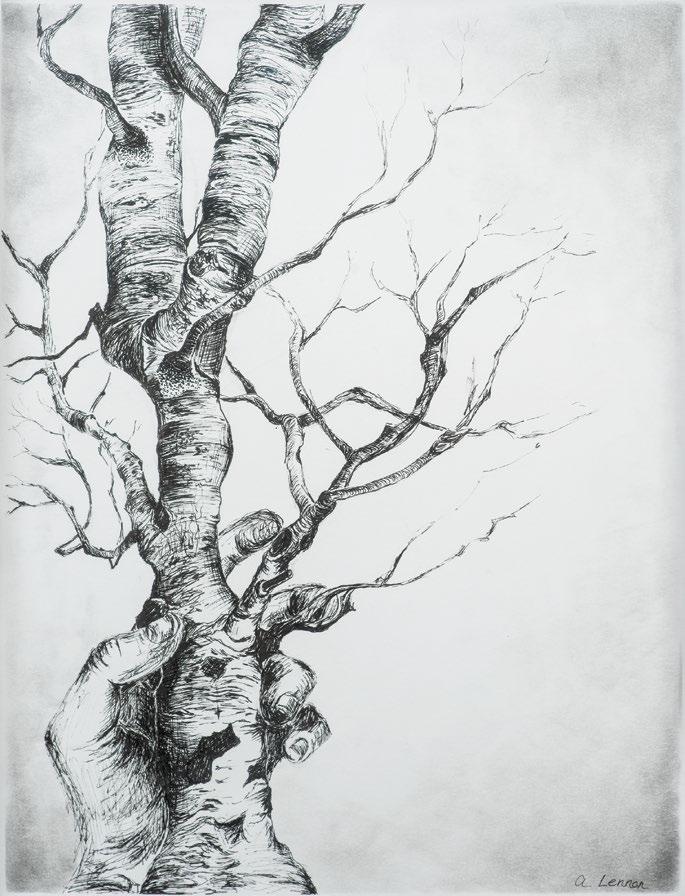

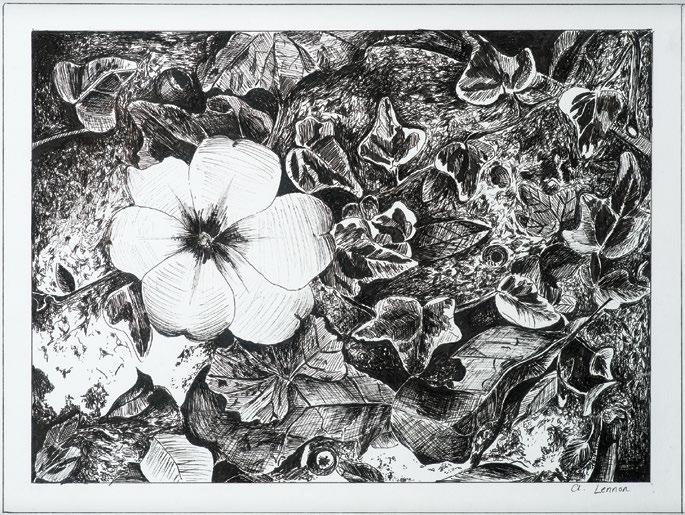

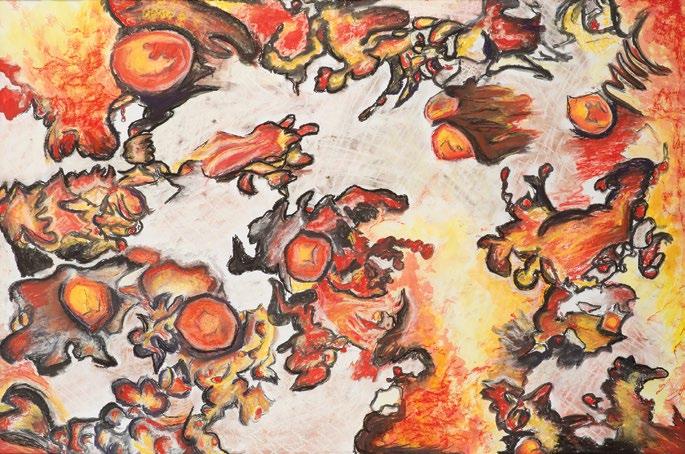

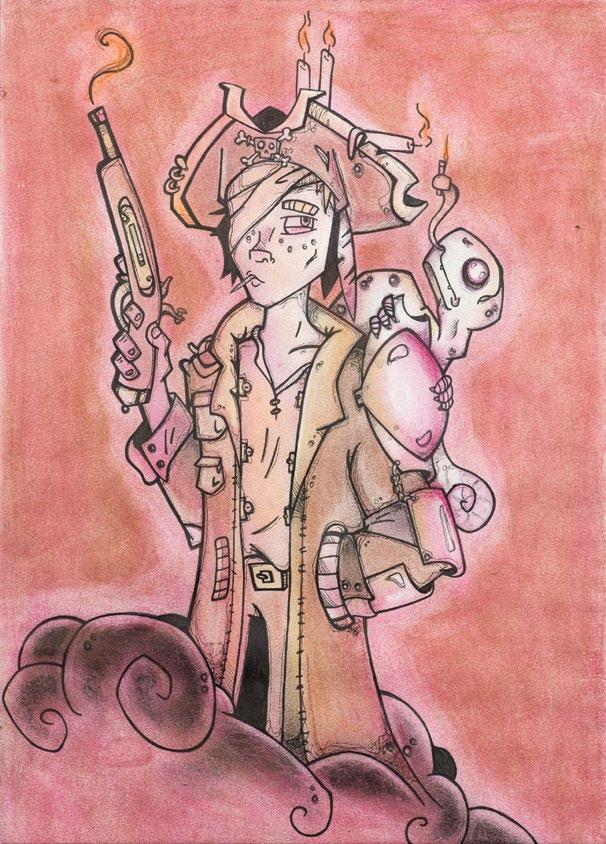

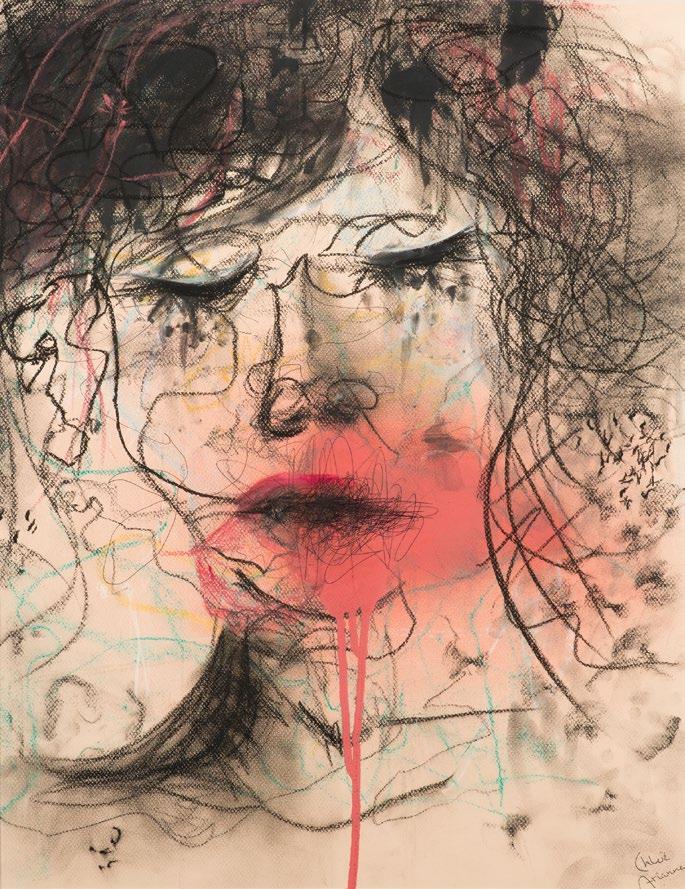

Photograph

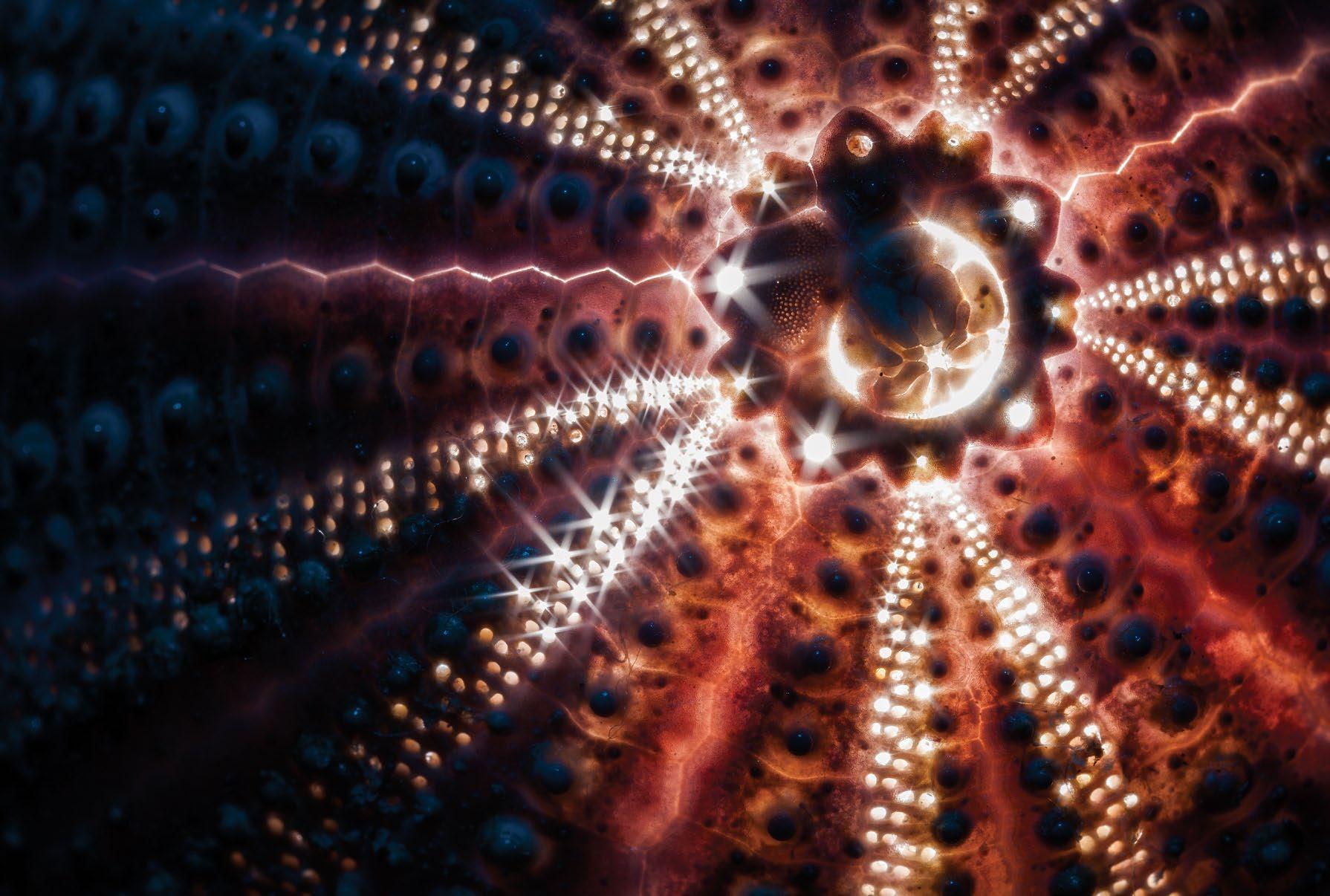

Apple Study

Serenity

Photograph The Last One

Neighbor

Billy E. Gartman II

Candace Harbin

Hnyla Photograph Weathered

Natalia Kireeva

Aeryn La Mar Graphite Family

Maria B. Morekis

Maria B. Morekis

Olivia

Linda Safford

Olivia walks three blocks from the market to the alley beside Baubles Jewelry Store. Her fast pace does not allow her to reach the stairs before the raindrops appear the size of saucers as they hit the sidewalk. Climbing the stairs and fumbling with the key, she cusses, drops the bag of groceries, and then cusses some more as she unlocks the door. She glances to see a man at the bottom of the stairs.

“Ophelia doesn’t live here anymore,” she yells to him.

“I’m not looking for Ophelia. I’m looking for Olivia. Are you…her?”

The rain is now pouring in solid sheets blown by the wind.

“Go away,” she says as she grabs the box of spaghetti, the head of lettuce, and makes her way into the apartment. As she places her soggy load on the kitchen counter, there is a knock at the door.

“Olivia! I need to talk to you,” the man yells with volume but without anger.

“I don’t know you. I don’t know anyone. Go away.”

“Your Aunt Ophelia told me I’d find you here. She’s an old friend. So was your mother.”

“Go away!” yells Olivia with angry volume. “I’m calling the police!”

She wipes the rain from her arms with sheets of paper towels and pulls her cell phone from her pocket. She quickly scrolls the list and finds the number for the jewelry store owner. She texts him.

“Go outside and get the man away from my door. I don’t know him.”

A fast reply.

“I’ve been watching. He’s OK. Let him in.”

“NO!”

“Trust me. Let him in.”

Aunt Ophelia had introduced Olivia to the jewelry store owner when she moved into the loft. Warren Zogby, the owner and designer at Baubles, is the only person Olivia has met in Bayside, Florida. She feels confident in his words, “Trust me,” because she felt something trust-worthy about him when they met, something in his eyes.

She walks to the door and slowly opens it to a three-inch crack. “I have people watching.”

He smiles, “Please, I am not going to harm you. I only need to talk to you.”

Olivia moves back and allows the man into the apartment. He is soaked from head to toe and begins to take off his shoes.

“May I have a towel?”

Olivia eyes him up and down. “Wait here. Don’t dare sit on anything.”

“I won’t.”

Olivia likes his voice and finds his patience admirable. Most of the men she has known would be screaming and ready to point a gun at her head for having kept them standing in the rain.

“So who are you?” she asks as she hands him a beach towel.

“Thank you,” he says as he takes the towel and dries off. “I’m Harlan Breck.”

She steps back, cants her head to one side, and squints her eyes. “I’m calling the police,” she says as she pulls her phone from her pocket.

“No! Wait! I know my name is familiar to you from North Carolina. I’m his son.”

“Whose son?”

“Harlan Breck is my father. He owns Breck Furniture. Your mother worked there.”

“How do you know?”

“I know her … well … I knew her then. We met in 1997.”

“Well, she’s dead. My so-called father murdered her. Now he’s dead.”

Olivia walks to the kitchen and sets out a Dutch oven and

begins cooking ground beef. “She never mentioned you.”

“I think she did. She had to have mentioned her summer vacation here with Ophelia. About seventeen years ago?”

She begins chopping an onion and bell pepper. “Aunt Ophelia said you’d come. Let’s stop beating around the bush, ok? If I’m your daughter, just say so. ”

“I don’t know for sure.”

“Aunt Ophelia said you’d say that.”

Olivia wipes her hands on the kitchen towel and walks to the credenza by the door. From a basket she picks up the three envelopes and hands them to him. “Mom obviously never mailed these. I found them in her safe-deposit box.” She watches him take in a deep breath and exhale. His eyes are fixed on the address.

“I’ve not lived there for at least fifteen years.”

“You don’t have to open them here. I don’t care what’s in them. Whatever happened, whomever I may share a genealogy with, at this point in life, I don’t care. I’ve got to work on me and set out on this new adventure called adulthood.”

He smiles. “I heard your mom say those exact words… about setting out on her new adventure of adulthood. We were both seventeen.”

“And were you lovers?”

He nods. “It was sweet and almost innocent. We were together for three weeks. Then she had to move back to North Carolina.”

“Why did you stay here?”

“College. My father had it all set for me. He had my entire life planned.”

“So you’re married?”

“Divorced.”

Olivia nodded her head. “Look, I’ve had a screwed up and jumbled life. My dad was a drug dealer, and my mom and I bore the brunt of his rampages. She didn’t have the money to leave. She worked the factory line.”

“Can I help you finish whatever it is you’re making? Can we talk and get to know each other?”

“I don’t want to get to know you. I had a father. Pitiful

Safford • 73

excuse for one, but he got what was coming to him … finally. A swift prison sentence and then murder … the same way he killed my mom. They sliced his throat.”

“Oh God, Olivia … ”

“What, you didn’t know she was murdered? Hard to believe with all the news coverage. I had an eyewitness view. He was high as a kite and drunk. He murdered her out of anger and jealousy … pure and simple. They said, after he came off his high, he had no clue he had murdered her. I saw his eyes, and I heard his accusations. He knew exactly what he was doing.”

Harlan shakes his head and moves to the window overlooking the parking lot behind the building. A small shaded park is beyond the lot. He sees the water through a break in the trees. “Last time I saw your mom we were on the other side of the park sitting on a bench. Are you sure she never told you about me? Am I the reason you came here?”

“When my father raged against my mother, he told her to go find her Florida lover and get the hell out of his life. She ran into the bedroom and started packing. That’s when he slit her throat. I came here to see if you were worth my losing her.”

She can see Harlan’s eyes welling up with tears. He tries to fight back his emotions.

“Don’t cry for her or me. Maybe I did come here to find you, but one thing is sure—I’m on my own, and I’ll make my own way. I’m set. Believe it or not, he actually had insurance money on himself and Mom. It’s not enough to live like a rich girl, but I can get a job, and it will put me through school. It’s the only good thing out of this wicked nightmare. Unlike my mom or grandmother, I don’t have to live in Breck’s Grove. I don’t have to be harnessed to everyone’s bad decisions. Go open your cards, on your park bench, and mourn her. I don’t need a happy ending with my long-lost Daddy coming to my rescue.”

He glances at the cards and looks back up at Olivia. “I wish she’d had a fighting spirit.”

“I think you’re the one who needed a fighting spirit.”

He nods, “I agree. I didn’t have any fight in me, and my

father ruled my world. I should have been a man. I’m not that way anymore. I know it’s too late now to make any difference. I want to know for sure you are my daughter. I want to be a part of your life.”

“You should go. Maybe we can talk some other time. I just don’t see what difference it can make. I’ll tell Aunt Ophelia you came by. She felt our meeting needed to be a priority. I don’t see why. Your life is set, and so is mine. I’ve never had a real father, and I don’t need one now.”

“I hope you’ll come around to changing your mind about a relationship with me, Olivia. I’ll go. Call me if you need anything; here’s my number.” He places a business card on the counter and turns to leave.

Olivia steps back to the stove and pours the tomato sauce and spices into the ground beef. Tears are close, but she does not let them flow … not for him … not for anyone today. One day soon she will sit in the park, on their bench, and cry for her mom.

Samantha Monteverde

… I love the thrill of impending, weightless doom … —Jennifer Niven, All the Bright Places

“Such a dull place, this here is,” Zipporah remarked. The three young reapers were just entering the village. The village itself was dreary and gloomy. It didn’t help that the sky, too, was gray with clouds.

“We’re only here to speak with the head of this town. It’s not like we’re going to live here or anything of the sort,” Dinah replied as she pulled her horse to a stop outside one of the buildings that seemed to be where businesses were housed.

“C’mon then,” she told her friends before sliding off her horse. A bow held in one hand and her quiver of arrows slung across her back, she made her way to the front of the building with a sense of purpose in every stride she took. Her friends followed in her wake, looking just as deadly and menacing as she. Dinah felt every eye watching her as she mounted the steps to the front of the building. Casting a look behind her, she saw many sets of eyes watching her from the corner of every window, both bottom and top floors.

“Be wary; we have an audience,” she said offhandedly to her friends.

Entering the building, they were greeted with a warm fire in the fireplace and a man writing things down at a desk by candle light. The room had a few windows and cupboards placed around the bottom floor. To the right of the little room in the back corner there was a set of stairs leading up to the second floor. Looking up, Dinah saw empty chairs and benches surrounding the top in a square ring.

“Who are you?” The man at the desk asked harshly. His eyes disdainfully scrutinized Dinah’s apparel, and seeing Zipporah’s clothing, he looked ready to throw a fit.

“You sent for us, sir?” Jason responded when Dinah didn’t say anything.

“Aren’t you too young to be fighting off vampires and werewolves? You hardly look older than a young child, much less like one capable of fighting!”

“We’re eighteen years old, sir, and more than capable of handling ourselves. You called and we came because this is our sector, and we’re here to protect those who ask.” As Dinah spoke, she sensed Zipporah ready to lash out at his obvious rudeness. “Are you the person in charge of this village?” she questioned impatiently. When he nodded, she smiled a wolfish grin, “Jason, shut the door. We have some matters to discuss with this here man.” At the sight of her smile, he grew nervous and pale. Never had he had to deal with those of the Angelum Lucis race, let alone a Reaper.

Following orders, Jason closed the door behind them. The three Reapers crossed the room to stand in front of the man. There were two chairs available, so Jason had his two companions sit while he stood behind. Jason looked at the man in an intimidating way, arms crossed and face emotionless.

“My name is Dinah, and these are my friends, Zipporah and Jason,” she gestured to them respectively. “Who sent us the letter?” Dinah asked.

“That’ll be me, Henry Penstive of Widdleton,” he responded with a slight quake to his voice. Dinah felt his nervousness in the air and felt somewhat bad that he was scared of them, for it was never her intention to frighten him. Nevertheless, she had to put him in his place. He asked for help, her help to be exact, and he shouldn’t go and criticize her looks – after all beggars can’t be choosers.

“Pleased to make your acquaintance,” Dinah responded. “What seems to be your problem?” Zipporah demanded, getting to the point.

The man pushed aside his papers and set down his writing quill. Taking a deep breath, he began to explain, “We’ve had people disappearing from nearby villages. Children disappearing, to be exact.”

“What does that have to do with us? Ever thought that they were wandering around in the woods surrounding the villages? I also don’t see how this concerns you; if anything they’re the ones who should be calling on us,” Zipporah said at once.

“Z, be quiet,” Jason told her, setting a hand on her shoulder to make sure that she remained seated. Dinah almost groaned with Zipporah’s quick temper.

“I thought it was just as you suggested until it happened to my village. My little girl was taken during the night. You see, it was no simple kidnapping. Nothing else was taken or broken, and no one even noticed she was missing till around the middle of the morning.”

“How can you not notice your child missing until mid-morning?” Zipporah fired off right away.

“We’re villagers, and we work day in and day out getting food, water, and wood. I thought my wife might’ve sent her for more firewood. But that’s beside the point; I believe that something took my daughter from me during the night.”

Dinah sensed her companions about to talk, so she held up a hand to silence their barrage of questions and remarks, “What exactly are you saying here, Mr. Penstive?”

“I’m saying, that I believe that a vampire has taken a villager from my village, and I want my little girl back.”

“You do know that that is a serious accusation to make. Vampires and werewolves aren’t something to be messed with,” Jason remarked.

“I’m very aware of that, Mr. Jason. But I’m sure that there has been a vampire in my village.”

“Vampires cannot come into a house unless invited in. In saying so, the only way the vampire would have been able to kidnap the child is if she let the monster in or she was out of the house. Both of which seem unlikely given the time period in which this event occurred,” Dinah told him.

“However unlikely the scenario might be, I stand by it that my child was taken by a vampire.”

Dinah was about to respond when Zipporah interrupted:

“This can all be solved if we just go to your house and see for ourselves. There we’ll be able to detect if there was indeed a vampire.”

Dinah looked at her friend and gave a smile. Why hadn’t she thought of that? “Zipporah’s right. Take us to the house, and we will determine if it was a vampire or not.”

“Certainly,” he responded. Standing up from behind his desk, he gestured for the door. The three Reapers took that as their cue to exit.

“Mount your horses; the house is a little farther than a walk down the lane,” Henry suggested to them. Dinah tied her bow to the saddle before mounting her horse.

“Follow me,” Henry commanded once everyone was mounted. They took off in a trot down the lane and followed the bend in the path to a house that was at the edge of the village. “You would think they would put a fence or something,” Jason muttered too low for Henry to hear.

The house was dreary as was the rest of the town and the sky. Built out of wood that looked like it was starting to turn gray, it looked like it had been through hell and back and was ready to face more. The roof of the house needed some patching and a few boards were loose from the walls of the house making the shelter look a little unstable. There were two windows from what Dinah could see, but nothing seemed to show that a vampire crossed this land. Behind the house was a slightly larger building, looking just as rundown as the house did.

“Everyone lives off the land,” Henry commented, sensing their questions about the big open land full of vegetables. He got off his horse and began walking up the path to the front door. Dinah, Zipporah, and Jason followed suit. They were just passing the gate when a woman came through the front door. She looked disheveled, and her hair looked like her hands ran through it quite a lot, making a few dark blonde strands come loose from the bun. Her weary brown eyes searched the Reapers with slight apprehension, worried that they would cause harm to what was left of her little family.

“Who are you?” she demanded.

“Easy, Elizabeth, they’re here to help. They’ll bring our daughter back.”

“If we can, of course,” Zipporah butted in.

“Quiet, Z,” Dinah reprimanded.

“Help? They’ll bring our daughter back alive and well?” She demanded, cutting her eyes from her husband to the three Reapers.

“We will see what we can do. But if it’s possible to bring your daughter back alive and healthy, we will do so,” Dinah responded.

“Come along, I’ll show you the house,” and Henry gestured for them to follow.

The house was sparsely furnished, two cots pushed in the right hand corner of the house near the fireplace with a kitchen table toward the left. A sink took resident beneath a window across from the door. There were two chairs in front of another window and a rug in front of the fireplace.