It is a tough hope that is needed in the world right now.

KATHERINE COLLINS, ARRIVAL , POP TECH 2022

It is a tough hope that is needed in the world right now.

KATHERINE COLLINS, ARRIVAL , POP TECH 2022

With this question, N Square launched the sixth cohort of the Innovators Network Fellowship. Looking ahead to 2095, how would our world be changed if national and international security was no longer based on the threat of nuclear weapons?

This assignment proved challenging on a number of counts.

First, the complicated nature of global security. Threats to security have become more intricately intertwined and interconnected. Climate change may spark a pandemic, triggering mass suffering, economic fragility and political clashes between countries. Or, an armed conflict may contribute to ecological degradation or impair food distribution placing people at risk in other parts of the world.

The potential interactions between these threats pose a dilemma for global security — each risk must be addressed on its own terms,

but no single approach will be sufficient to the multifactorial challenges the world faces. Second, the problem of mental models and frameworks. Trying to conceptualize new infrastructures and frameworks for the maintenance of peace is daunting. For people working in the security apparatus, it is difficult to step outside of doctrines of deterrence and co nflict in place since World War II. For newcomers, the complexity and secrecy of the established systems restricts access and engagement. For all, in the field or not, the need to address real and present concerns makes long term imagining difficult.

Individually, they represent different world views and conflicting understandings of what peace is and how it can be secured.

Initial conversations ping-ponged between debating the merits of a security apparatus based on the threats of nuclear annihilation and trying to imagine new approaches to human and planetary security. But as they grappled with these poles and argued with each other, the fellows began to identify the outlines of resilient structures that could help societies prepare for, and sustain, our shared future(s).

Through those debates and discussions, fellows kept returning to the question, “What capacities must we cultivate and exercise for a more secure future?”

The final challenge was placing ourselves 70 years in the future. To ask what might happen and to explore how our societies might be reshaped over the next two generations to make the world more secure.

What emerged was the nascent operating system shared here.

To address these challenges, and to invite as broad a discussion as possible, the fellows were drawn from a wide range of practices — they include a nuclear disarmament activist, two instructors from the U.S. military academies, a community activist, a technologist, a nuclear scientist, an investment officer with a divinity degree, a creative director and the leader of a NGO dedicated to independent journalism.

As a metaphor, an operating system allows us to visualize the protocols and procedures that might give form to new futures without having to imagine a new world whole cloth.

In computation, an operating system mediates between different layers and applications — each working independently and often developed in different coding languages. This flexibility allows different applications working toward different purposes to function together to create a shared platform. Like a computer operating system, a planetary operating system should enable functional interoperability between different world views and different agendas.

The eight elements of our operating system were conceived by a small group of people over a very limited time, while undoubtedly incomplete, they shine a light on the intersectional nature of the local and global challenges we face in this century and the next.

In our case, interoperability between governance and participatory structures above and below the scale of the nation-state. This is not a small point — one of the important features of an operating system is that it does not rely on a single vision or protocol, thereby enabling many different activities and outcomes.

If you would like to take up these debates and investigations, following each element of the operating system we share some of the inspirations and questions that helped to crystalize and clarify our thinking. Let us begin, stepping out of today and journey forward to 2095.

It is possible, and it will be tempting for readers, to try to assemble these components into a single story. But our purpose here is not to predict or perfect a particular future. Instead, we hope that this operating system will prompt consideration of alternative ways of meeting the challenges of our shared future. It is intended to invite readers to ask fundamental questions about their current worldviews, conduct closer investigation of the components necessary to secure our future(s) and debate the particulars of those components.

Here in 2095, it is hard to identify a single event that shocked people and governments into seeing that new global security priorities were required to assure human survival. Perhaps we can say it was the accumulation of climate shocks that catalyzed demands for new responsive and resilient approaches to building human security in the face of destabilizing environmental, economic and social factors.

It could have gone either way. During the 2020s many of the dominant powers appeared to be on paths toward autocratic rule, rising nationalism, and isolationism. Global incidents could have caused a retrenchment on the part of the nuclear powers, but they did not.

Partly because the scope and scale of climate challenges galvanized people around the world. And partly because the nuclear weapons states began to scuttle their arsenals when it became clear their stockpiles could be weaponized against them.

Of course, the removal of nuclear weapons required new approaches to secure peace in an anarchic world — that is a new international approach to strategic deterrence to hold geopolitical threats in place. But, we leave that story to others to tell. Our story focuses on the parallel efforts of millions of people to reduce those threats by attending to human and planetary security.

DIGITAL POLITIES AND NEW FORMS OF CITIZENSHIP

TRANSCONTINENTAL RENEWABLE ENERGY SYSTEMS

NEW AGREEMENTS AND NEW SIGNATORIES

LEGAL RIGHTS OF ECOSYSTEMS

NEW LEDGERS AND NEW ACCOUNTABILITY

INTERCONNECTED GLOBAL MONITORING SYSTEMS

A RENAISSANCE IN NUCLEAR INNOVATION AND SCIENCE

Food security became a pillar of a security architecture dedicated to the preservation of basic human needs during the 2050s and 2070s. At this time, governments, activist groups, non-governmental organizations and multinational corporations found common cause.

It became clear that food shortages, social unrest and refugee migration would, over time, threaten civil society; both in countries unable to feed their people and in countries with more stable agricultural production. All parties collaborated to establish more diverse regional food production systems to address shifts in arable lands and to mitigate the weather-related damage to global food stocks.

As a result of that process, they contribute to the maintenance of the global food systems where representatives from different regions and sectors work locally and transnationally to shore up basic human needs. This prevention-first approach minimizes insurgency and sectarian violence.

Using high tech and low tech methods to support and sustain regional approaches to food production this alliance of NGOs, activists, governments and security organizations work together to build more resilient food systems.

Can we meet the challenge of reimagining global security to establish an international order that builds resilience towards trans–national threats, which may in turn increase the agency of nations, large and small, to act towards their own interests?

What are people’s definitions of long-term security?

What does security mean in a global world? Especially for the people who experienced insecurity based on the previous security systems? We don’t want the new system to entrench a colonial world order.

If we are to imagine a future security approach centered on common, human and planetary security needs. Then we would need to anchor this futurism by addressing environmental destruction, social disparities, and injustices fueled in pursuit of capitalistic gains that are foundational to our current system.

JEANNE

BOURGAULTWill this require a new intergovernmental organization—something other than the United Nations?

In hindsight, it was just a matter of time. As liberal democracies foundered in the early part of the century, people looked for new forms of political organization and affiliation. New states and polities were able to build political power and provide for the security of their citizens by leveraging the digital economy. In the process, they created new arenas for political solidarity, international action and the expression of shared values.

Today, citizens of international diasporas — whether their countries were rendered uninhabitable by climate change, their economies unable to provide a living, or their cultures stolen by forced relocation are no longer treated as refugees. An international federation of digital states has signed agreements with the European Union, China, Brazil, the African Union and North America allowing their citizens to qualify for travel and work visas.

In exchange, citizens of physical countries may also apply for work visas to participate in the robust economies of the digital states.

The Union of the Greater Pacific provides digital passports for its citizens around the world.

Their consulates provide physical footholds for the citizens of digital polities — providing shelter, support and representation.

Mobile consulates are co-located to provide easy access for citizens and to allow member states of the Union to share services.

Could distributed networking technologies, combined with ways of knowing and being that honor our integral connection to planet Earth, help new forms of sovereignty to emerge ‘above’ and ‘below’ the nation-state?

How can we apply creativity and technology to design new ways of staying connected when people are no longer connected to their homelands?

How might notions of sovereignty evolve?

JESS

How can we build a metaverse when our ‘verse’ is so flawed? How do we avoid reproducing the same problems?

There is nothing magical about the nation-state — but it is the current ‘best practice’ for assuring survival in an anarchic international system.

What if sovereignty was not limited to nation-state identities and structures? What would other forms of cultural or environmental sovereignty look like?

Tuvalu rebuilding on a blockchain to have a record of it

What will emerge if more of the world’s population are not represented by nation-states?

The nation-state is not a given in 2095.JULIA GORBACH

If the climate crisis made the need for renewables clear, the Ukrainian war and its immediate aftermath was a wake up call. Countries around the world watched as the European Union was caught between the demands of a hostile petrostate and the limited production capacity of renewable energy systems. Not wanting to find themselves in such a precarious position, countries began investing in their own green infrastructures.

As wind, solar, thermal and hydro production increased, countries began to negotiate new energy exchanges to assure their citizens had consistent access to energy.

Today, countries no longer triangulate between a few petrostates. Instead, states rich in solar, wind and water power share their electrical production across borders to assure their independence from fossil fuels and the interdependent resilience of their renewable energy systems.

Energy transmission sites and long distance power lines are now sites for regional and international diplomacy.

Ceremonial flags like these celebrate regional resources and international interdependence.

Commemorative, diplomatic gifts representing renewable energy agreements (here biofuels and wind energy) are now commonplace.

What if accelerating climate change forced a global ban on fossil fuels — requiring nuclear materials to power energy systems?

What can we learn from developing nations with robust ecologies about investment opportunities and strategies in green infrastructure?

How has their slow and measured progress revealed a standard for development that can shed light on progressive efforts to reimagine growth cycles ?

Clean Energy Is Key to National Security for European Union and United States

How might an energy transition shift diplomatic relations?

Systems change within the energy sector is made more difficult by the animosity toward the big players. What are the leverage points?

The Role of Renewable Energy in National Security

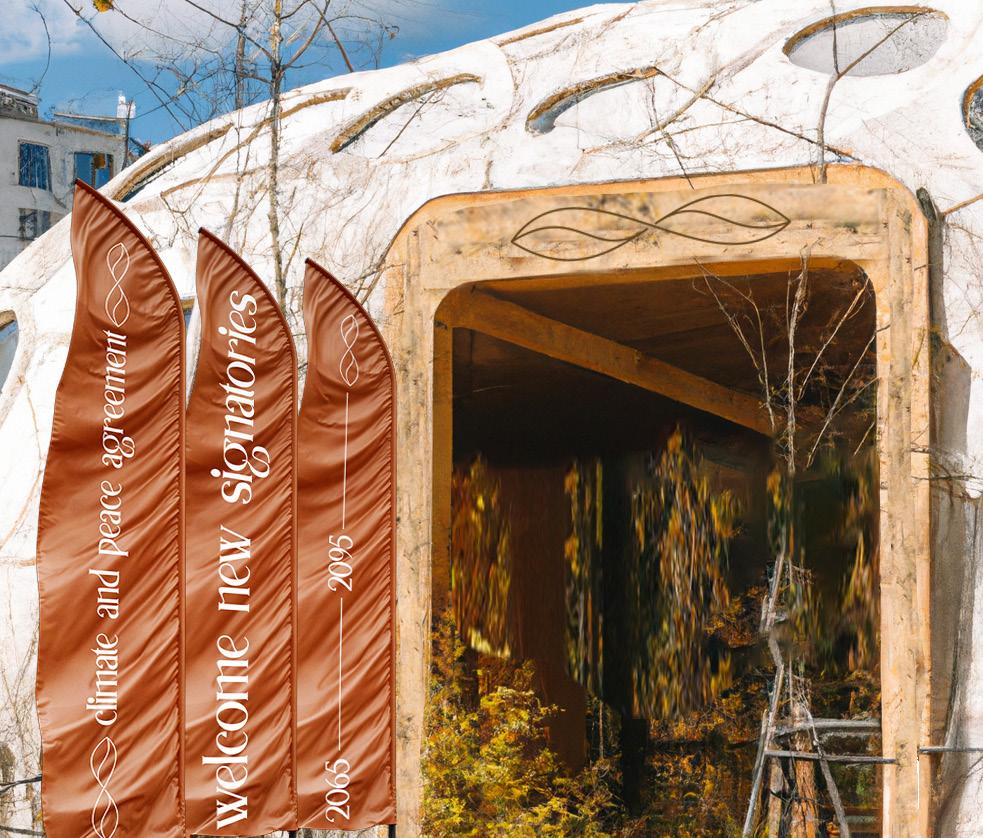

In 2065, nearly 1.25 billion people, 10% of the world’s population, signed an international agreement to hold world powers to their climate and peace commitments. Non-state advocates worked to create platforms so that underrepresented communities, indigenous nations and young people could effectively bring pressure to governments and regional trading blocs. As a result, they created new structures and pathways for individuals, groups and communities to participate in international governance.

Today, there are hundreds of binding agreements signed by world citizens, and ratified by other parties, that address peace, trade, defense, territorial boundaries, human rights, law enforcement, environmental matters. These new methods of engagement and recognition have given voice to people around the world.

To commemorate the 30th anniversary of these historic climate and peace agreements, new civic buildings are being built internationally to welcome new signatories in 2095.

These civic buildings are part assembly hall — gathering spaces for debates and decisions, part archive — preserving the terms and texts of the agreements, and part monument — honoring, and recording by name the millions of signatories from around the world.

What changes will the emergence of more women and indigenous leaders bring about?

The TPNW, Equity, and Transforming the Nuclear Community: An Interview with Nuclear Scholar Dr. Aditi Verma

What does democracy look like in 2095, and what mechanisms will there be to channel voices upward to governments? And how will they hold governments accountable?

The Power of Matriarchy: Intergenerational Indigenous Women’s Leadership

Can new agreements be negotiated in the absence of state action?

Tools for Social Change: How to Develop a Liberatory Consciousness

BY BARBARA J LOVE

BY BARBARA J LOVE

LEADERSHIP FOR EDUCATIONAL EQUITY

BY JESS BROWN

Youth will define security.

How do we work with, for and alongside communities that are determining their needs?

What do non-colonial peace treaties look like?

In 2075, a legal settlement recognized the rights of Lake Erie, the eleventh largest lake in the world, and required executives to confront the effects of their companies’ practices and measure their progress in reducing toxic algal blooms. The widespread recognition of ecosystems and ecosystems services has been essential to preserving human and planetary health.

For the twentieth year in a row, executives from local manufacturing plants joined scientists, local leaders and citizens to walk through the waters of Lake Erie. Events like this one, that recognize the lake and its stewards are now commonplace. Similar events will take place this year at Lake Taihu in China, Lake Biwa in Japan, and in communities surrounding Lake Victoria in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

Walking the lake brings together people from across sectors. This event is a civil ceremony, a public performance and an annual scientific assessment of the health of the lake.

The rope used at this event is ceremonial but its use is specified in the settlement with businesses charged with cleaning the lake.

How do we secure ourselves in the face of the pressures posed by food insecurity, mass migration and climate rendering places uninhabitable?

The legal framework enabling legal personhood for ecosystems in NZ. For many, many years - in some instances, decades - Maori iwi have been working to seek redress for breaches by the Crown (the government) of the guarantees set out in the Treaty of Waitangi. These negotiations have resulted in specific claims and settlements, that set out compensation and other issues agreed to between the NZ Government and Maori iwi.

In a post human-centric world, we must finally recognize our role as part of a greater natural system and we need to take responsibility for our actions. So, if the planet is what needs to be secured right now to restore balance, it needs to be given a voice.

What mechanisms can we use to help secure and support planetary function?

How secure will we be behind national boundaries if the planetary boundaries are breached due to the inability of governments to cooperate?

Is the link between legal rights and a deeper recognition of the value of ecosystems too weak? Everything is indebted to these ecosystems and those debts are coming due.

The Converging Risks Lab of the Council on Strategic Risks (CSR) released a landmark report that identifies ecological disruption as a major and underappreciated security threat and calls on the United States to reboot its national security architecture and doctrine to better respond to this evolving threat landscape.

JULIA GORBACHLYNDON BURFORD MICHELLE LATIMER SHARED BY JULIA GORBACH SHARED BY LYNDON BURFORD AUSTRALIAN EARTH LAWS ALLIANCE

The use of traceable transactions and independent currencies was first prototyped to promote human rights by activists and block chain enthusiasts in the 2020s. The increased transparency and security of information-rich transactions was used to track and reduce carbon emissions, coercive practices and slave labor. This week the Human Rights DAO reached a major milestone with the ratification of its human rights protocol. The widespread adoption of the HR DAO protocol today makes it the most universal non-legal framework for protecting human rights, tracking more than a million transactions per day.

But the HR DAO is just one of the organizations developed over the past fifty years that use distributed ledger protocols to embed more information in transactions. Internationally, more and more people are participating in these distributed systems making these advances more stable while also providing alternatives to state economics and currencies. Consumer habits and rapid adoption have brought this system to the everyday marketplace.

In a temporary pop up celebration, the Human Rights DAO took over all of the screens on Times Square to celebrate its passing 1,500,000 transactions.

Increasingly, companies and consumers are using HR DAO’s assessment to evaluate and certify their products.

HR DAO members regularly hold open meetings to adjust its protocols — updating them to make them more effective.

If future norms and laws are encoded in algorithms used to govern societies, the question of who writes the code is critical. Justice and equity will depend on a diversity of voices and lived experiences being represented in the code.

Blockchain-powered distributed governance for communities, institutions and the world.

“…blockchain affords the potential for governance mechanisms that were literally unimaginable in the past, because the technologies needed to imagine them did not exist. It significantly expands the design space to think creatively about the architecture and dynamics of a decentralized security system that would truly serve humanity’s needs”

BY LYNDON BURFORDIt is hard to remember how zealously private companies and countries guarded their sensor and satellite data in the early part of the century. By 2030, citizens and nongovernmental organizations had cobbled together sensor data and satellite imagery that enabled them to track nuclear weapon signatures. As more organizations found ways to access these data sources, they built a lattice of global monitoring systems that enhanced our ability to monitor greenhouse gas emissions, ocean-going vessels, ecological system services and military activity at a global scale.

This cross-sector dissemination and sharing has become so commonplace that last week a zoonotic spillover was avoided when bird populations infected with the deadly variation of avian flu were identified at a fragile forest edge. Local animal control officers, supported by a consortium of scientists, public health professionals and civilian monitors working in 10 countries, were able to identify and cull infected members of the flocks in three provinces — thereby protecting human and animal populations throughout the region.

Monitoring go teams can be dispatched to address and combat short term outbreaks and spillover events.

Field operatives are supported with sensor kits that allow them to do real time analysis in the field and share the results on a global uplink.

Longer term earth observatory sites allow for ongoing assessment in at-risk areas.

Cryptocurrencies built on public blockchains create significant privacy risks. Their governmentcontrolled cousins, Central Bank Digital Currencies, create significant risks of digital authoritarianism by making state-controlled money that is programmable and censorable. To protect human and civil rights, these systems and the legal contexts they operate in need stringent privacy protections. Zero knowledge computation and homomorphic encryption are important areas of exploration in those regards.

How will nation-states resist or respond to these monitoring systems?

When we equip people with tools to self-monitor to protect themselves and their communities we also need to address the dangers of intrusive surveillance and self-monitoring at scale.

What is the information ecosystem that this new world will require?

We need new feedback loops and information flows. So that accurate and relevant signals are received and our responses to those signals are appropriate and effective.

Ways of Being

Can we order and organize disparate monitoring and data analysis systems for the safekeeping of human and planetary health?

Dismantling the nuclear security apparatus released, by some estimates, a quadrillion dollars into world economies and freed the research attention of physicists and scientists globally. This contributed to a flowering of nuclear innovation, nuclear medicine and nuclear energy.

One of the outcomes of this flowering of nuclear science is that today research stations located in the depths of the Mariana Trench and the outer reaches of the Asteroid Belt have been supporting multi-year research projects for decades — building planetary science, sponsoring experiments in extreme locations and contributing to innovations in small fusion reactors.

The Outer Space Ecosystem Research Center is just one of a growing string of long term research platforms supported by clean fusion.

These research platforms enable long term exploration, yielding new discoveries about geochemistry of the hadalpelagic zone.

What does it mean to design and manage these technologies equitably?

“We are attempting to imagine a path toward a nuclear engineering discipline that better prepares its intellectual progeny to sense and reason with the inevitable moral dissonances that the management—creation as well as dismantlement—of nuclear technologies poses for society.”

BY ADITI VERMA & DENIA DJOKIC ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYSHARED BY ADITI VERMA

Though having vast potential to support social progress, these technologies inevitably also produce serious harms. How should such harms, past and future, be repaired? Can these harms be sufficiently repaired to justify the continued existence of these technologies?

What kinds of reparations are needed (or useful) for the peoples and communities most effected by uranium mining, nuclear power production or nuclear wastes?

Physicists have an important role to play in technology development and policymaking related to nuclear weapons, expressed Robock, along with three other speakers during the meeting’s plenary sessions on nuclear threat and mitigation. Robock encouraged meeting attendees to join the Physicists Coalition for Nuclear Threat Reduction.

Let us step back into our time machine and return to our present day. We have seen a future, or indeed facets of many possible futures.

Meeting the challenge of assuring our shared survival is a multigenerational project. One that requires simultaneously hospicing old systems and midwifing new ones. These transitions will not be ea sy. They will oblige us to find ways to work together across communities, across ideologies and across time. And they will demand skill, attention and dedication.

Taken as a premise, the OS invites the examination of our closely held beliefs about security and its purposes. As it did for Kiki and Brian in their discussion at Pop Tech about new security architectures.

One might refer to the catalog to make sense of things we encounter in our daily lives, as Jeanne and Katherine have reported using it.

As a collection, the OS can be used to guide further investigations. As when Leo asks what structures might preserve global stability in 2095? Or to ask what elements might be missing in the framework. Studying a single element allows one to work through its implications and possibilities. When Julia and Lyndon began asking exactly how an interconnected global monitoring system might function, for example, they began to identify specific approaches and safeguards that might balance swift action with the protection of individual privacy rights.

Or each of the eight elements could be the subject for signal scanning.

Engaging in any of these exercises can focus the mind. They may call us to focus on the important work at hand as they did for Jess.

They may encourage us to carry these conversations forward with colleagues or students, as they do for Aditi. Or they may inspire us to take up entirely new projects.

The experiences of the fellows suggest that there are at least three ways this Operating System might be put to these efforts in 2023.

The larger N Square community and its partners are actively engaged in similar processes across other projects. Asking: What could the future look like?

What is happening now? What steps do we need to take in the transition?

If you want to get involved, we encourage you to visit nsquare.org.

Associate Professor, Department of Defense Analysis Naval Postgraduate School

Associate Professor, Department of Defense Analysis Naval Postgraduate School

If nuclear weapons ‘went away’ — what would take their place? What fills the space of strategic deterrence?

Leo has worked for a number of entities across the Department of Defense, exploring how organizations respond when their legacy modes of operation no longer match their evolving strategic environment.

Leading teams of military officers, academics, and other experts, he helps organizations rethink how they gather information, measure success, invest in infrastructure and most importantly link their daily activities to deeper strategic purpose. He wrote Rational Empires: Institutional Incentives and Imperial Expansion (University of Chicago Press, 2012) and co-edited Assessing War: The Challenge of Measuring Success and Failure (Georgetown University Press, 2015). He has also published numerous articles on strategy, metrics/assessment, intelligence, and emerging technology.

Can human security be scaled?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position or policy of the Department of the Navy or Department of Defense.

The nation state is not a given in 2095. How might notions of sovereignty evolve?

How will nation-states resist or respond to these monitoring systems?

There is nothing magical about the nation state — but it is the current ‘best practice’ for assuring survival in an anarchic international system.

What changes will the emergence of more women and indigenous leaders bring about?

Will this require a new intergovernmental organization — something other than the United Nations?

As president and CEO of Internews, Jeanne leads the organization’s strategic management and its programs in more than 100 countries.

Under her leadership, Internews has fostered independent media sectors in countries such as Jordan and South Sudan and provided lifesaving information to people during crises in Ukraine, Myanmar, and Afghanistan. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Jeanne led Internews’s Rapid Response Fund to help local media partners access emergency funding and continue operating in dire economic conditions. An expert on issues of media for democracy, misinformation/disinformation, women’s media leadership, information technology, and participatory community development, Jeanne has spoken at venues such as the Skoll World Forum, the Global Philanthropy Forum, and the World Economic Forum in Davos.

How will we organize around climate change and resource allocation?

What is the information ecosystem that this new world will require?

What will the generations of tomorrow aspire to and what will they fear?

JEANNE BOURGAULTAssistant Professor of Industrial Design Rhode Island School of Design

Can human security be scaled?

How can we build a metaverse when our ‘verse’ is so flawed? How do we avoid reproducing the same problems?

How do we work with, for and alongside communities that are determining their needs?

Jessica Brown is a multidisciplinary, multimedia spectacle generator, creative connector, black futurist, afronaut cosmic explorer, and mermaid creating disruptive & discursive work. Her work is rooted in liberation theology, dipped in pop culture references, sprinkled with humor, and packaged in Joy. At RISD, she is an Assistant Professor of Industrial Design. She serves on the University’s Board of Social Equity & Inclusion (SEI) and Community Engagement steering committees. Previously, Jess was a toy designer and Project Manager of Product Development at Hasbro, In her own multidisciplinary work, Jess creates flexible environments that facilitate an inclusive space to explore, reflect, and discuss the challenges of social justice concerns in the US. She holds a BFA in furniture design from Murray State University and an MFA in industrial design from RISD. Active in her community, Jessica served as a board member of the Providence municipal Reparations Commission, She is a board member and artist at the Nicolson File Art Studios, board member of PRONK! the Providence Honk Festival of bands,member of the Haus of Glitter, and founder of Optimistic People Project! and FLOAT!

How will we organize around climate change and resource allocation?

How do we account for, work with, and understand the trauma associated with the questions we are asking?

What kinds of reparations are needed (or useful) for the peoples and communities most affected by uranium mining, nuclear power production or nuclear wastes?

Lyndon is a nuclear disarmament researcher. In that context, he is currently exploring the opportunities and risks of distributed ledger technologies and specifically, blockchain. He is the N Square research lead on New Technologies, Agency and Power, a project forming part of the Horizon 2045 consortium, and is also the inaugural N Square Network Weaver in Residence. Lyndon is a visiting research associate at the Centre for Science and Security Studies, King’s College London, and a cofounder of PATH Collective. PATH is a mission-driven startup working to connect communities working on humanitarian approaches to nuclear disarmament with opportunities in blockchain-based art, storytelling, and fundraising.

How secure will we be behind national boundaries if the planetary boundaries are breached due to the inability of governments to cooperate?

Cryptocurrencies built on public blockchains create significant privacy risks. Their government-controlled cousins, Central Bank Digital Currencies, create significant risks of digital authoritarianism by making state-controlled money that is programmable and censorable. To protect human and civil rights, these systems and the legal contexts they operate in need stringent privacy protections. Zero knowledge computation and homomorphic encryption are important areas of exploration in those regards.

How do we make peace profitable and create a system that authentically reproduces peace and equity?

How do we solve the ‘problem’ of nuclear risk when those with power and agency to affect nuclear risk directly also see nuclear risk as the ‘solution’?

If future norms and laws are encoded in algorithms used to govern societies, the question of who writes the code is critical. Justice and equity will depend on a diversity of voices and lived experiences being represented in the code.

What capacities must we cultivate and exercise for a more secure future?

KATHERINE COLLINSKatherine Collins is Head of Sustainable Investing at Putnam Investments and portfolio manager for Putnam’s Sustainable Equity strategies, with approximately $6.5 billion in assets under management. Ms. Collins has over thirty years’ experience as an active fundamental investor, and was named to the inaugural Forbes ‘50 Over 50’ list of leaders who are shaping the future of finance in 2021. She is a beekeeper, the author of Month of Sundays and The Nature of Investing , and founder of Honeybee Capital, an independent investment research firm focused on sustainable investment themes. Earlier in her career, she served as Head of Equity Research, Portfolio Manager, and Equity Research Analyst at Fidelity Investments. Katherine serves on several nonprofit boards, including the Santa Fe Institute, Omega Institute, Harvard Divinity School Dean’s Council, and Wellesley Centers for Women. She earned a Master of Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School and a B.A. from Wellesley College, and is a CFA charter holder.

The nation state is not a given in 2095. How might notions of sovereignty evolve?

Systems change within the energy sector is made more difficult by the animosity toward the big players. What are the leverage points?

Is the link between legal rights and a deeper recognition of the value of ecosystems too weak?

Everything is indebted to these ecosystems and those debts are coming due.

We need new feedback loops and information flows. So that accurate and relevant signals are received and our responses to those signals are appropriate and effective.INTERCONNECTED GLOBAL MONITORING SYSTEMS

JEANNE BOURGAULT

What if sovereignty was not limited to nation-state identities and structures? What would other forms of cultural or environmental sovereignty look like?

Julia Gorbach is a Ukrainian-American Emmy award-winning storyteller and conceptual creative director / strategist who works across media and technology. Founder of Wild Minds, a creative advisory and content innovation lab, she partners with clients to listen deeply to their purpose and playfully design content, experiences, and products. Julia has worked with some of the world’s most innovative brands to start-ups, studios, nonprofits and small businesses changing the way we think, express, connect and experience today.

How will we organize around climate change and resource allocation?

In a post-human-centric world, we must finally recognize our role as part of a greater natural system and we need to take responsibility for our actions. So, if the planet is what needs to be secured right now to restore balance, it needs to be given a voice.

When we equip people with tools to self-monitor to protect themselves and their communities we also need to address the dangers of intrusive surveillance and self-monitoring at scale.

Associate Professor and Director of Strategic Plans and Assessment United States Military Academy West Point

Can we meet the challenge of re-imagining global security to establish an international order that builds resilience towards trans-national threats, which may in turn increase the agency of nations, large and small, to act towards their own interests?

What if accelerating climate change forced a global ban on fossil fuels — requiring nuclear materials to power energy systems?

Brian is an active-duty Army Colonel and an associate professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point. His professional military experience includes various armor and cavalry command and staff positions from platoon to brigade levels and operational and combat deployments to Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Brian previously served as director of West Point’s Center for Innovation and Engineering, where he coordinated and funded multidisciplinary project-based design education and research efforts for various Army, Department of Defense, and civilian sponsors. Brian holds a PhD in engineering education and is a licensed professional engineer in the Commonwealth of Virginia. He holds leadership positions within the American Society for Engineering Education and is a frequent reviewer for multiple academic journals.

How do we secure ourselves in the face of the pressures posed by food insecurity, mass migration and climate rendering places uninhabitable?

How does national trauma contribute to competition?

How long is a national memory?

Will we ever get over the past?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect those of the Army or the United States Government.

What tools do we need to prepare future leaders for an unclear future?

What kinds of reparations are needed (or useful) for the peoples and communities most affected by uranium mining, nuclear power production or nuclear wastes?

Security can only be secured by cultivating diversity and consistently re-engaging how to expand on biodiversity and earth systems.

Kiki is an award winning Design Engineer completing studies at RISD. A product developer turned conceptual digital and material design engineer, she loves operating at the intersection of intelligent systems, interaction design, sustainability and fine art. Using multichannel systems to explore science, technology, and society, her practice establishes roots and embodiment within the philosophical realm of the digital humanities. As an indigenous, Kenyan American designer, her work provokes onlookers to confront assumptions, standards, and lexicology through inviting art and design lovers to investigate the social and ecological impact of our visually hypnotic and easily accessible material and digital culture. Because no matter how far we go into the future and into the galaxy, there is something tethering us all to the soul-crafting beauty of the earth. Currently, her work is exploring geospatial frameworks, embedded narrative environments, accessibility, energy systems, and luxury.

If we are to imagine a future security approach centered on common, human and planetary security needs. Then we would need to anchor this futurism by addressing environmental destruction, social disparities, and injustices fueled in pursuit of capitalistic gains that are foundational to our current system.

How can the AI revolution, blockchain, and the oscillating waves of web 3 begin to address designing for healthy earth systems and transformative social systems?

KIKI NYAGAH JESS BROWN, KIKI NYAGAH, ADITI VERMA KIKI NYAGAHIf nuclear weapons are dismantled, how will we hold nuclear states and non-state actors accountable?

Assistant Professor

Department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences

University of Michigan

What does security mean in a global world? Especially for the people who experienced insecurity based on the previous security systems? We don’t want the new system to entrench a colonial world order.

Aditi is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences at the University of Michigan. She is broadly interested in how nuclear technologies specifically, and complex technologies broadly, can be designed in collaboration with publics such that traditionally excluded perspectives can be brought into these design processes. Verma is a Visiting Scholar at the Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs’ Project on Managing the Atom, and former Stanton Nuclear Security Postdoctoral Fellow at the Belfer Center where she was jointly appointed by the Project on Managing the Atom and the International Security Program. Previously, she worked at the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, where her work focused on bringing epistemologies from the humanities and social sciences to academic and practitioner nuclear engineering, thus broadening their epistemic core. She also held positions at the International Atomic Energy Agency, Framatome (formerly Areva), and the Center for the Study of Science, Technology and Policy. Aditi holds undergraduate and doctoral degrees in Nuclear Science and Engineering from MIT. Her doctoral research combined theoretical and methodological resources from design studies and sociology to study how reactor designers make decisions in the foundational early stages of design, particularly those bearing on safety.

What do non-colonial peace treaties look like?

What does democracy look like in 2095, and what mechanisms will there be to channel voices upward to governments? And how will they hold governments accountable?

What happens when we release the people, structures and materials from the nuclear security apparatus?

This work would not be possible without the work of many hands...

fellows to illustrate scenarios and to help further focus and refine the ideas underlying each element of the Operating System.

First — none of this would have been possible without the active engagement of the sixth cohort of N Square Innovators Network fellows.

The Altimeter Design Group and PopTech worked closely with N Square to organize this cohort of N Square fellows and to run the convening in Maine, in June 2022, and to carry the conversations to PopTech’s annual conference in D.C. in October of that same year.

As a result of this process, there is no single author for any of the ideas shown here, nor a single consensus about how an Operating System like this one might emerge over the next two generations.

The Operating System was conceived and developed in dialogue.

From the Fall of 2022 to March 2023, Charlie Cannon, Megan Valanidas and Tomiris Mimi Shyngyssova listened and participated in fellows’ conversations, teasing out themes and ideas and sharing them back for reflection and refinement.

The graphic design of this document was developed by Tomiris Mimi Shyngyssova in close collaboration with Charlie Cannon and Megan Valanidas. Special thanks to Tim Maly of the Center for Complexity at the Rhode Island School of Design for reading and commenting on ideas and final drafts. Thank you to all those who helped make this work possible.

As the elements of the Operating System emerged they were shared with Altimeter designers Chad Hagen, Rives Matson, Kate Danessa and Tomiris Mimi Shyngyssova who began to develop specific scenarios and artifacts. These pieces flowed back into conversation with the

Launched by five of the largest peace and security funders in the US, N Square is a path-breaking initiative built on the idea that new forms of cross-sector collaboration—combined with the sheer ingenuity of an engaged public—will accelerate the achievement of internationally agreed goals to reduce nuclear dangers. A hands-on alliance among iconoclasts, innovators, funders, and advisors, N Square brings new ideas, new people and new perspectives to the ‘wicked problem’ posed by nuclear weapons. By fostering partnerships between experts from diverse backgrounds, N Square helps nuclear specialists gain new perspectives on problem-solving while introducing new allies to the complexities of the nuclear threat.

The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of N Square funders or the individual members of N Square and the N Square Innovators Network fellows or the organizations with which they are associated.

An Operating System for the 22nd Century © 2023 by N Square and Altimeter Design Group is licensed under Attribution-NonCommercialNoDerivatives 4.0 International. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ nsquare.org

DALL-E 2 (OpenAI) was used in visualizing ideas and generating a visual basis for some of the final artifacts.

Type: Archivo Family (Omnibus-Type, 2021); Familjen Grotesk Regular (Familjen STHLM AB); Martel (Dan Reynolds, 2014).

DALL-E 2 (OpenAI) was used in visualizing ideas and generating a visual basis for some of the final artifacts.

Type: Archivo Family (Omnibus-Type, 2021); Familjen Grotesk Regular (Familjen STHLM AB); Martel (Dan Reynolds, 2014).