Face to Face

The decant of Room 30, August 2020

Face to Face Issue 65

Director of Development

Jessica Litwin

Manager

Daniel Hausherr

Copy Editor

Elisabeth Ingles

Designer

Annabel Dalziel

All images

National Portrait Gallery, London and © National Portrait Gallery, London unless stated

npg.org.uk

Gallery Switchboard 020 7306 0055

The Gallery is committed to reducing our environmental impact and this magazine is printed on paper certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council and is fully recyclable.

Dr Nicholas Cullinan

as 2021 opened , the construction phase of the Gallery’s Inspiring People project began in earnest. It has taken an enormous amount of work by dedicated staff and contractors, all pulling together behind the scenes, to reach this significant milestone. In the first of a series of articles looking in greater depth at the Inspiring People project, Alix Gilmer, the Project Director, tells us more about the challenges of the building renovations. Alexandra Gent, Paintings Conservator, also tells us how the team moved a 3-metre painting through a 2-metre door as part of the Collection decant.

The Gallery has remained very busy during the closure period, with most staff working from home because of Covid-19 restrictions. In the autumn of 2020, we launched our Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize as an online-only exhibition for the first time. Andy Horn, who under normal circumstances would hang the show, tells us about the challenges and opportunities of holding an exhibition virtually. Also moving online is our hospitals programme, which engages with children across four London hospitals. Anna Linch, Participation Project Manager, tells us about the recently launched programme exploring community and creativity, using the stories of key figures in the world of healthcare and medical research.

The National Memorial Arboretum exhibited a series of Hold Still portraits inspired by the 2020 lockdown. Chris Ansell, NMA Head of Participation and Learning, shares his experience of staging an in-person exhibition during a pandemic.

This issue also looks at two new acquisitions by Jabez Hogg, who is today remembered not for his work as an ophthalmic doctor in Victorian London, but for being a pioneer of the emerging art form of photography. Rachel Wang, award-winning filmmaker and Gallery Trustee, casts her cinematic eye over the Collection to tell us about her favourite portrait.

Finally, one of our curators, Clare Freestone, tells us about her work on the Madame Yevonde archive. Yevonde was a pioneer of colour photography and is well represented in the Gallery’s Collection.

We hope that you are all continuing to keep safe and well. We appreciate your ongoing support of the Gallery and will keep you updated on our progress as the project moves forward.

Dr Nicholas Cullinan director

MY FAVOURITE PORTRAIT

by Rachel Wang

Documentary Filmmaker

below

Sir Henry Unton (detail) by unknown artist, 1596 (NPG 710)

as a documentary maker , I love delving into people’s life stories. What drives them? What makes them unique? What more can I discover about the kind of world they live in? It’s this fascination that drives my love of portraiture.

There are many paintings that I visit time after time at the Gallery. Some feature sitters I admire, others have been created by artists whose work I love. Occasionally, if I’m really lucky, a painting will fit both of these categories. But the one painting I’m drawn to above all others is by an unknown artist and depicts a sitter whom I know very little about. This is the portrait of the sixteenth-century soldier and diplomat Sir Henry Unton.

To me, this rich and evocative portrait feels filmic – a bio-pic of a statesman rendered in oil paint. It was commissioned by Sir Henry’s wife Dorothy following his death. Dorothy referred to it as a ‘story picture’. It is dominated by a large figure of Sir Henry, but this is just one

of several portraits of him on this panel – I’ve counted thirteen Sir Henrys but there could be more. This is his life in storyboard form, told anti-clockwise from birth to burial with episodes depicting him as a student, ambassador and traveller. Each scene is replete with tiny symbolic details, such as a loyal white dog, the winged figure of fame, and the ominous skeleton with an hourglass on his shoulder.

More than 400 years after his death, this painting transports me to his world and offers a rare insight into the culture and pastimes of the sixteenth century. I like to imagine that Sir Henry, sitting at the central desk, is reflecting on his full life. He has a quill in his hand and is poised to write his own life story.

Rachel Wang is a Trustee of the National Portrait Gallery, and also chairs the Gallery’s Digital Advisory Group. She is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and one of the founding directors of Chocolate Films. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and a Member of BAFTA.

Photo: Rachel Wang © AWITA

HOSPITALS PROGRAMME: CREATIVITY AND COMMUNITY IN THE MIDST OF COVID-19

by Anna Linch Participation Project Manager

what did the nation turn to during the first lockdown? Creativity and community. We made rainbows for our windows, we clapped for the NHS and our key workers, children sent paintings and drawings to decorate the Nightingale Hospitals. Art became a way of coping and coming together. We see this day-to-day in the Hospitals Programme, where art plays a fundamental role in health and wellbeing, and as the virus took over our lives in spring 2020 we thought about how to share the Collection remotely with families isolating at home and in hospitals.

As I write this, the first vaccine dosing outside a clinical trial has been administered at University Hospital Coventry. Our Collection holds testament to the nation’s leaders in science and medicine, from Edward Jenner, the surgeon who discovered the smallpox vaccine, to geneticist and biochemist Sir Paul Nurse. When faced with the challenge of developing digital resources in a time of national lockdown, it seemed fitting to

start with the stories of these inspirational healthcare heroes. A series of films was made about the nurse, adventurer and writer Mary Seacole, previous Chief Medical Officer Dame Sally Davies and Director of the Francis Crick Institute Sir Paul Nurse; the last of these has been involved in the worldwide search for a vaccine.

Thanks to support from property and real estate investment advisor Delancey, a series of new digital activities was also made available on the Gallery website, developed from the activity book Playful Portraits. Using materials and items usually found around the home, these were designed to inspire families to engage with the Collection, working together to create and explore art within the confines of their four walls. We are delighted to announce that Delancey and its platform business (Get Living, Here East and The Earls Court Development Company), are funding the next four years of the programme, Champions of the World. As we move into 2021, we are striving to ensure children and young people in hospitals remain connected to the Gallery, through a series of remote workshops run by our team of experienced Gallery Educators. With visitor limitations and social distancing measures in place, the bleak reality is that many children in hospitals may not have seen a face without a mask or visor for some time. While personal interaction remains one to one, it is more important than ever to reach out to this audience and bring people together safely through art.

by Amber Speed Corporate Development Manager

the star wars franchise is a cultural phenomenon that has had a huge impact on popular culture. From the beginning, the film saga has involved a wide range of British film industry talent, from leading actors to those working behind the scenes: from Alec Guinness’s and Peter Cushing’s roles in Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), shot mainly in Hertfordshire at Elstree Studios, to John Boyega and Daisy Ridley in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (2019), much of which was filmed at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire.

To celebrate this link to British industry and culture the Gallery worked with Disney+ on a special display, which aimed to introduce new audiences to our Collection. The display was located in the West End on 30 and 31 October 2020 and marked the launch of the second season of Lucasfilm’s The Mandalorian. This

below left Felicity Jones by Laura Pannack, 3 February 2016 (NPG x199584)

Riz Ahmed by Sharif Hamza, 2018 (NPG x200373)

included images from the Gallery’s Collection of Star Wars actors such as Felicity Jones, Riz Ahmed, Sir Alec Guinness and Thandie Newton, as well as Ben Morris who helped create the stunning visual effects, and, lastly, the film director and screenwriter Gareth Edwards. The display also included original concept art from The Mandalorian and a painting entitled The Mandalorian and the Child.

Disney+ is supporting the Young People’s Programme at the Gallery and, as part of the scheme, members of the Youth Forum assisted the curatorial team in creating the captions for the display. Aimed at 14–21-year-olds, the Young People’s Programme encourages young people to get involved in art and portraiture.

Our thanks go to everyone at the Gallery and Disney+ who helped make this partnership possible.

© Sharif Hamza

Emily Stone

AND REMEMBERING

Inspiring People Participation Manager

over the next three years the Gallery is working on Citizen UK, a partnership with four organisations to explore twentieth-century migration stories and bring to light some of the significant figures currently missing from the national story. ‘Citizen Researchers’ from Tower Hamlets, Ealing, Croydon and Wolverhampton will work with artists to delve into local archives and the National Portrait Gallery Collection to reveal local acts of resistance, generosity and community.

2021 will see the fiftieth anniversary of Bangladesh’s independence and the launch of our first project with Tower Hamlets. Nineteen citizen researchers, artist Ruhul Abdin and digital producers Rainbow Collective have looked at archive material, from 1920s photographs of lascars (Indian seamen) in Limehouse to newspaper cuttings about 1971 and the march from Brick Lane to Trafalgar Square in support of an independent Bangladesh. Online workshops enabled discussions across generations and continents to consider consent, value, agency and how

below

Amy Barbour-James by an unknown photographer, mid-1930s (NPG x133300)

Amy Barbour-James was the daughter of Guyanese colonial officer John Alexander Barbour-James. She was born in 1906 and grew up in Acton, Ealing, with her mother and seven siblings. She was a civil rights activist and became the secretary for the League of Coloured Peoples in 1942, an organisation founded by Harold Moody in 1931. Amy died in 1988 and gifted the majority of her correspondence including letters and photographs to the Black Cultural Archive as an important record of black histories and black activism in London.

below

Recognise Bangladesh rally taken from An Album of 1971: Bangladesh Liberation Movement by Yousuf

Choudhury

Published by Ethnic Minorities Original History and Research Centre, 2004

identity is formed, shaped and represented through portraiture, photography, language and so on. There was an overwhelming desire to remember the traumatic events of 1971 and the racism and inequality faced by many as a result, but also to contrast this by celebrating the joy within a diasporic community: to share the homes and domestic spaces created and particularly remember the women who resisted and persisted but were often not documented.

26 March 2021 will see the opening of a public artwork in Tower Hamlets, a collaboration between citizen researchers, Ruhul Abdin, Tower Hamlets and the National Portrait Gallery. If you’re nearby please pay it a visit. You can follow the progress of Citizen UK on the Gallery’s website.

With thanks to our partners: Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archive Service, Ealing Local History Centre, Museum of Croydon and Wolverhampton Arts & Culture.

Supported by: National Lottery Heritage Fund, Art Fund, Garfield Weston Art Fund

THE TAYLOR WESSING

PHOTOGRAPHIC PORTRAIT

PRIZE

by Andy Horn Exhibitions Manager

the gallery ’ s exhibitions team , like much of the organisation, has had to adapt quickly to the changes that this year has brought. We have had to learn how to work remotely – from meetings on Zoom and Teams, to overseeing the installation of touring exhibitions in other countries and time-zones from our phones at 6 am, to quickly learning how to create an exhibition online.

I have been fortunate enough this year to step in and support the development and delivery of this year’s Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize and to work closely with our Chief Curator of Photography, Magda Keaney, in creating this virtual exhibition of fifty-four photographs. I have previously installed several exhibitions in the Porter Gallery, a lovely and intimate space to work in, and it feels a bit like a swansong to work with its virtual Doppelgänger, as the physical gallery will not exist in the same way when the refurbished Gallery opens. As you will see when you visit the exhibition on the website, you almost feel that you are back in the gallery spaces.

One of the joys of this year’s exhibition is the breadth of its reach and representation. It is a truly global exhibition, with both sitters and photographers from many different countries and cultural backgrounds, faces and figures from both the margins of society and international celebrity, and expressions ranging from intense loss to celebrations of strength and empowerment. Many stories

below top Jaxxon and his Father by Georgie Wileman, 2020 © Georgie Wileman

below bottom

Uncle Noel Butler and Trish Butler at their Burnt Home, Nuru Gunyu, near Milton, New South Wales by Gideon Rendel, 2020 © Gideon Rendel

The Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize is viewable online until 31 March 2021 – https://www.npg.org.uk/photoprize

touch upon the challenges of our current times, such as the destruction caused by man-made climate change, the growth of food banks, fuelled by poverty and social inequality, and the effects of the pandemic impinging on everyday life. One of the results of having the exhibition online is its capacity to reach international audiences who might otherwise not visit the Gallery, and to reach new visitors.

Photography is a powerful medium: it can confer power upon both the photographer and the image. At a time when truth and traditional power relationships are often contested, and in a world where image is frequently taken for reality, capturing and communicating an authentic representation has never been more important. Many of the photographers in the exhibition have collaborated with their sitters and established sensitive and enduring relationships with them, and this is reflected in individual photographers’ approach to their work and the narratives they have written about their image. I have particularly enjoyed reading these descriptions, which are at times very moving.

The skills and experience gained in creating a virtual exhibition are something that we are all taking forward with us. We now often use this process to mock up and visualise an exhibition before we finally hang it, as well as continuing to improve our knowledge of how visitors engage with our online exhibitions:

they may have very differing skills in and confidence with technology and might view the exhibition as much from a phone as from a laptop. I often stay with my eighty-year-old aunt when I am working in London, who is a keen amateur photographer and regular visitor to the Portrait Prize exhibition. She is also someone with limited confidence with technology and so I am very aware of the need to make navigating an online exhibition as clear and straightforward as possible. I hope that we have achieved this.

Rebekah the food bank manager by Charlie Clift, 2020 © Charlie Clift

INSPIRING PEOPLE

by Alix Gilmer

Inspiring People Project Director

the main construction contract has now begun, an exciting new phase for the Inspiring People project. Gilbert Ash, the appointed contractor, started with site set-up in January and with erecting site hoarding around the building, a very visible sign that the construction work at the Gallery is now underway.

Over the summer, we prepared for the handover of the building. The Collection has been taken into storage and we cleared the front and back of house areas including the shops and café, retail storage, offices and the learning studio. We also moved the framing studio from the basement of the Duveen Wing to a temporary location in Orange Street one floor below the Conservation Studio, where we also have staff offices and the Library and Archive. This will allow us to undertake important

conservation work supporting our continuing loans programme. We continue to share works both nationally and internationally.

In advance of the main construction work, we undertook work to strip out and prepare the East Wing for the arrival of the construction team. This was previously the location for the shop, which will move to the Porter Gallery where it will be adjacent to our new entrance through the north façade. On the first floor of the East Wing, where we had staff offices, we will have new gallery spaces for part of our contemporary collection. A new kitchen on the second floor will support the expanded basement café, and new stairs and a lift will make the East Wing fully accessible.

Throughout the East Wing we removed floor coverings, electrical and mechanical

services and undertook some demolition and exploratory work. We were excited to discover the original terrazzo flooring and further investigation will establish whether this can be conserved as part of the project. In the North Wing we carried out a similar range of work, removing some of the fabric wall linings, asbestos removal and installing protection for the historic building fabric.

We have been working closely with the National Gallery to manage any vibration impact from our construction work on their Collection. This has involved numerous trials

of working methods with the construction team and vibration monitoring by the National Gallery; this is informing future ways of working and we will collaborate closely with them throughout the project. They are wonderful neighbours and are fully supportive of our programme.

Externally, the statue of Henry Irving has been dismantled and removed. The work was undertaken by a specialist stone conservator who will store Sir Henry for the duration of the construction phase before returning him to our new public forecourt.

HOW WE MOVED THE LARGEST PAINTINGS

by Alexandra Gent Paintings Conservator

moving the whole displayed Collection out of the Gallery was a huge undertaking. However, the scale of some portraits brought its own challenges. Six of the paintings in the National Portrait Gallery Collection are so big that they could not fit into our largest lift or through the external doors. The only way to move them out of the building was to roll them prior to transportation. This is not something we like to do, as it exerts some stress on the painting, but in this case it was necessary, as we had to remove the entire Collection in order for the Inspiring People redevelopment project to progress safely.

In this article we will focus on The General Officers of World War I by John Singer Sargent, to illustrate all the steps involved in de-installing and packing these immense paintings.

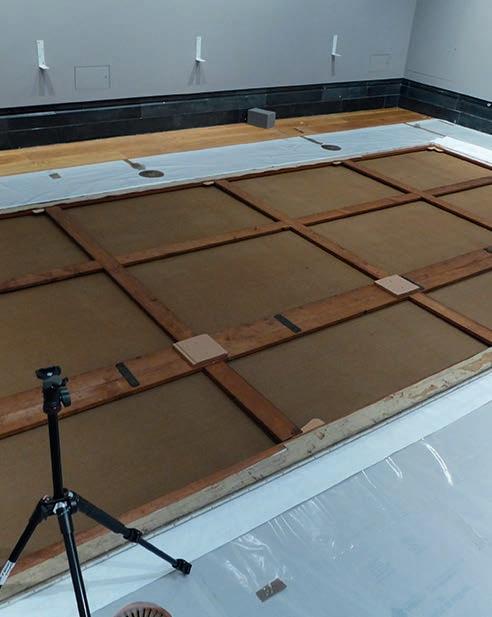

The first step was to take the painting down from the wall. Painting and frame together are very heavy, and so the art handling team used specialised equipment to do this safely. Stackers took the weight of the frame and allowed it to be lowered in a slow and controlled manner. Six art handlers were involved, helping to guide the painting and keep it balanced (fig. 1).

Once the painting was off the wall the frame could be removed and dismantled (fig. 2). The frames for very large paintings are specially designed so that they can be dismantled easily. In this case the corner joints were

held together with bolts. All the joints were labelled, so that the frame can eventually be reassembled in the correct order. Once it was carefully taken apart, each section was individually wrapped for protection during transport and storage.

With the frame safely out of the way, our attention turned to the painting itself. It was dusted with a soft brush to remove loose dirt. Unlike most of the paintings on display in the Gallery, these large pictures cannot be glazed, so particulate matter settles on their surfaces and we must dust them regularly. The floor was cleared and meticulously cleaned to make sure no debris remained that could cause damage. The cleaned area was then covered in a layer of polythene and another layer of Tyvek, which would also act as an interleaf when the painting was rolled. At this stage, the art handlers carefully laid the group portrait face down (fig. 3).

The next step was to remove the painting from the stretcher. Large oil paintings are executed on woven canvas supports. The canvas is tensioned over a wooden framework, called a stretcher, and is attached around the edges using tacks or staples. Each tack or staple was carefully removed by the paintings conservators to release the edges of the canvas. At this stage the stretcher could then be carefully lifted away from the canvas. Like the frame, the stretcher was also dismantled into its individual parts before being packed (fig. 4).

Illustrating the steps involved in de-installing John Singer Sargent’s The General Officers of World War I (NPG 1954)

When the stretcher was removed the edges of the canvas, called tacking margins, remained folded at right angles and needed to be flattened before the painting could be rolled. The tacking margins were gradually

eased down with care, using controlled heat and pressure, and then left weighted to cool completely. Once the whole canvas was flat the painting was ready to be rolled.

The large cardboard rollers, used in the construction industry for casting concrete pillars, are made by a specialist company. The rollers were adapted for us by the cratemakers to our specifications, inserting discs of plywood in the ends to provide strength and adding a larger outer circle to make an edge to facilitate rolling. A layer of impermeable foil membrane was also applied to the roller as a barrier layer to stop any acid from the cardboard affecting the painting. The large diameter of the roller reduced some of the stress on the paint layer and the plywood ends made sure that the roller didn’t rest on the painting.

Rolling the painting involved the conservators and art handlers working together. Two art handlers turned the roller from the ends, while the conservators guided the canvas with the Tyvek interleaf around it, with further art handlers holding the other edge of the painting to keep the tension (fig. 5).

Once the canvas had been rolled the end was secured with tape (fig. 6), and the whole painting was wrapped and sealed in polythene. Both the canvas and the frame will be stored like this and monitored regularly, until the portrait is needed for display again.

FIG. 2

FIG. 3

FIG. 4

FIG. 5 FIG. 6

FIG. 1

MADAME YEVONDE –A TONIC FOR TODAY

by Clare Freestone Curator, Photographs

in researching the photographer Madame Yevonde (1893–1975), it has become evident that her vivacious personality and highly original work offer welcome inspiration, both artistically and in a humanistic sense.

With a strong desire for personal independence, Yevonde opened her first studio in Victoria Street in 1914, following an apprenticeship with fashionable portrait photographer Madame Lallie Charles. Yevonde Philone Cumbers had dreaded the alternative ‘meaning of life … the endless procession of bored, ineffective, protected young ladies’. Mary Wollstonecraft was her heroine and it was through an advertisement in The Suffragette that she considered photography as a career option. As well as photographing theatrical and society sitters for the burgeoning number of periodicals, Yevonde’s first subjects included soldiers going off to war, and she paused her fledgling career to work on a farm for the ‘cause’.

Yevonde’s social conscience was balanced by her love of glamour; her business acumen countered her sense of fun. She was committed to both her profession and her gender. In 1921 she became the first woman to lecture at the Professional Photographers’ Association: ‘Photographic Portraiture from a Woman’s Point of View’ offered that ‘portrait photography without women would be a sorry business.’

Portrait photographers were numerous and innovation was necessary to survive the

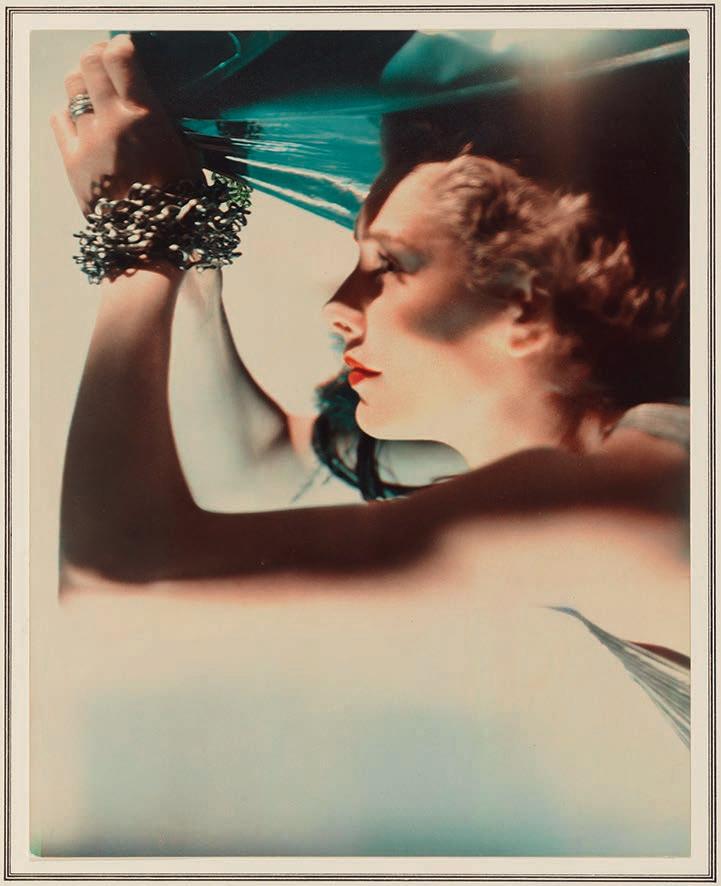

below Edith Brougham (Mrs Richard Hart-Davis) as Ariel by Madame Yevonde, 1935 Vivex colour print (NPG x11660)

interwar years – indeed, Yevonde’s dictum ‘be original or die’ manifested itself in her use of the Vivex colour process. As well as holding a number of her spectacular Vivex prints, the Gallery is in the process of acquiring Yevonde’s archive of 2,500 separation negatives, through the Portrait Fund.

Douglas Arthur Spencer’s process involved printing with vivid pigments, resulting in Yevonde’s desired ‘riot of colour’. This heightened sense of Technicolor reality, used commercially but not taken up widely by her contemporaries, appealed to Yevonde and

became a vehicle for her fantastical originality. In July 1935 An Intimate Exhibition –Goddesses and Others opened at her new Berkeley Square studio. Taking inspiration from a charity ‘Olympian’ ball, Yevonde posed over twenty women as classical goddesses in surreal and humorous tableaux. Dressed, propped, posed, lit, filtered, cropped, printed, retouched, and mounted, these magical images have become Yevonde’s passport to contemporary audiences.

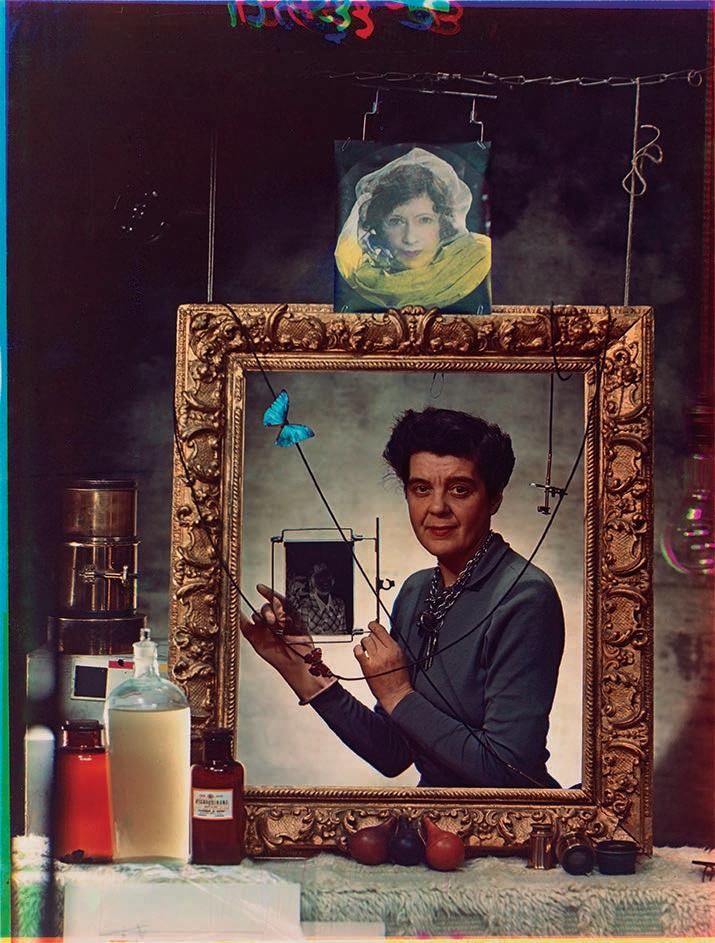

One of her last Vivex colour photographs (the process didn’t survive World War II) is her 1940 self-portrait. Here she has framed herself watched over by her portrait of the Duchess of Wellington as Hecate. Described by Yevonde as ‘the most interesting’ of her goddesses, Hecate is associated with the night, magic and necromancy. Yevonde displayed the apparatus of her craft as if alluding to the magic of photography. She wrote of the recent death of her husband, playwright and journalist Edgar Middleton, and of German bombing in her autobiography In Camera, published that year.

This moment marked the end of a chapter in Yevonde’s career; however, she continued to work for the next thirty years. Her innovations included environmental black and white portraits, playful photomontages and solarisation. She continued to celebrate women’s achievements and made new portraits for her exhibition Some Distinguished Women in 1968. The following year she wrote to the director of the National Portrait Gallery, below Self-portrait by Madame Yevonde, 1940 Colour dye transfer from the original Vivex negatives (NPG P620)

Roy Strong: ‘Having been in photography since 1914 I am considering drawing in my horns a bit and going into semi-retirement for the twentieth time.’ Following their correspondence Yevonde donated her portrait prints, many of them of key twentieth-century figures, to the Gallery. It is a great opportunity and indeed an inspiration that fifty years later we are able to research and investigate the tri-part negative archive. This research will contribute to a revaluation of Yevonde’s oeuvre and an exhibition of her work in the National Portrait Gallery’s future programme.

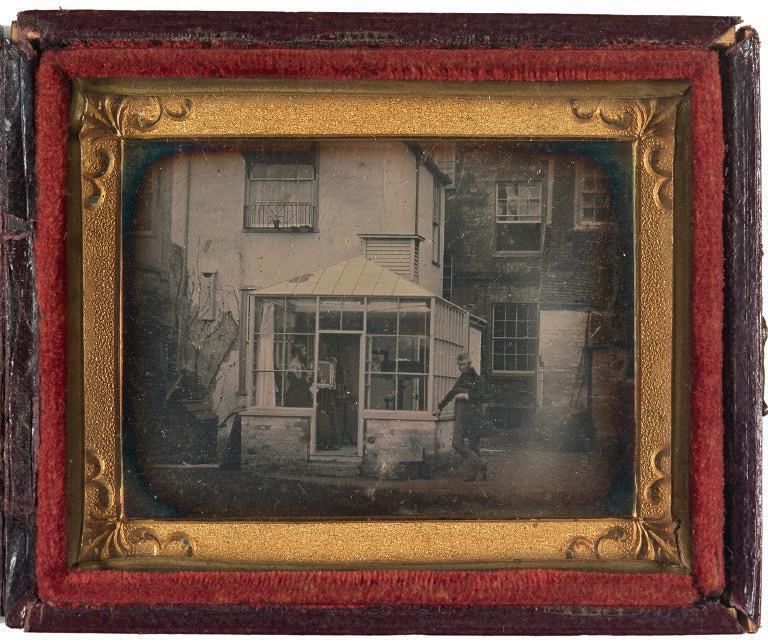

NEW ACQUISITIONS: JABEZ HOGG

by Magda Keaney Senior Curator, Photographs

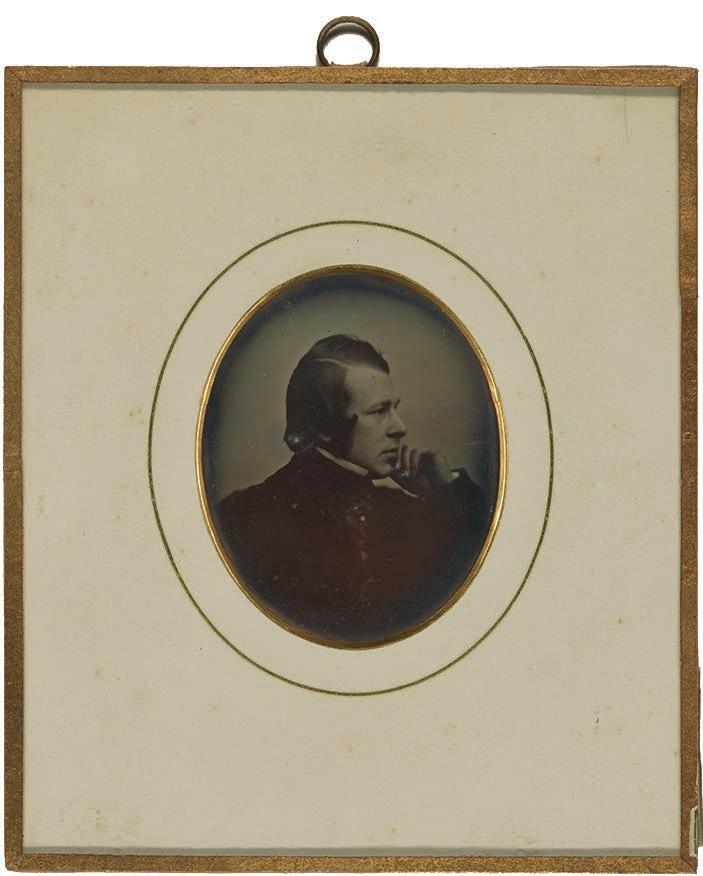

the gallery ’ s collection includes relatively few portraits of British photographic pioneers. Two new acquisitions related to the enthusiastic early photographer and noted physician Jabez Hogg are therefore important additions.

An ophthalmic surgeon, Jabez Hogg (1817–1899) entered the medical profession in 1840 and had a distinguished career attending at the Royal Westminster Ophthalmic Hospital, Charing Cross, for twenty-five years. He was a surgeon at the Hospital for Women and Children at Waterloo and a consultant to the Bloomsbury Eye Hospital. He was admitted as a member of the Royal College of Surgeons

below left

Jabez Hogg

Richard Beard studio, c.1843 (NPG P2092)

in 1850 and was well known for his major published work The Microscope, its History, Construction and Applications (1854).

Hogg was an early adopter of photography. He was an associate of Richard Beard’s ‘Photographic Institutions’, the first daguerreotype studios established in London, in 1841. His Practical Guide to Photography (1843) was published in several editions, promising ‘Full and plain directions for the economical production of really good daguerreotype portraits and pictures’. He is credited as having an important role in the application of photography in the printed press and worked with the Illustrated London News as an adviser and writer from 1843. During the late 1880s he was the editor of the Illustrated London Almanac. A series of his daguerreotype portraits of doctors and scientists is owned by the Royal College of Surgeons.

The first portrait is a striking head and shoulders profile of Jabez Hogg in his late twenties, attributed to the Beard Studios. It was made around 1843, when Hogg was active in photographic circles. Here he is not shown at work as a ‘photographer’, as he is in the famous daguerreotype ‘Jabez Hogg and Mr Johnson’ (c.1843), held in the collection of the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford. However, with his carefully groomed hair and smart highcollared jacket, he is certainly pictured as a respectable gentleman. This is in keeping

with the persona of a medical practitioner, but was also how Victorian photographers often chose to present themselves. An interesting comparative image from the Collection is Benjamin Brecknell Turner’s 1855 portrait of his wife and brother-in-law. Turner is represented by his camera in the bottom right-hand corner of the frame. The image is taken in his studio, which he has transformed into a middle-class drawingroom, alluding to respectability, taste and the pursuit of cultural interests.

The second daguerreotype is a rare, intriguing depiction of a makeshift photographic studio in London, also made around 1843. It illustrates a glasshouse behind a Victorian property being used to make photographs. A woman and another figure seem to be posing or standing in front of a camera –possibly a Wolcott daguerreotype camera. A third unidentified man stands outside. More research is needed to determine exactly whose studio this is. Though the object was owned by Hogg and was previously thought to show his own space, this has not been proved conclusively.

The development of the daguerreotype studio was nothing short of a revolution in portrait-making. Besides its relationship to Hogg, this acquisition is of great value as there are no other known examples of a depiction of an early 1840s studio from this point of view, particularly not in London. The image positions the photographic

below top

below bottom

An early photographic studio in London by an unknown photographer [Associate of Jabez Hogg, possibly Jabez Hogg], c.1843 (NPG P2091)

portrait and the apparatus of the camera in relation to the history of art, with a print or painting seen on the easel. In the revelation of the broader setting it raises a dialogue around class and photography – what kinds of people could make daguerreotypes and who had their portrait made.

Humphrey Chamberlain; Agnes Turner (née Chamberlain) by Benjamin Brecknell Turner, 1855 (NPG P1003)

HOLD

TO REMEMBER

by Chris Ansell Head of Participation and Learning at the National Memorial Arboretum

visitors to the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire were treated to a special exhibition of Hold Still late last year. All of the portraits selected for the community exhibition were shown on outdoor digital screens in the grounds of the 150-acre Arboretum, which provided a safe environment for people to view the collection.

As the nation’s centre of remembrance, the Arboretum is a place to recognise those who have served our nation, including key workers and members of the NHS, and to remember those who have been lost. After viewing the exhibition, many people chose to walk the Arboretum and reflect on their experience of lockdown among over 25,000 trees and 300 memorials to military and civilian service organisations.

Of the 100 portraits featured in Hold Still, three were taken in Staffordshire, including Roshni Haque’s photograph ‘Eid-Ul-Fitr 2020’. The exhibition captured the diverse

The Hold Still exhibition at National Memorial Arboretum, Staffordshire, 2020

range of people’s experiences during lockdown while highlighting how connected everyone felt to each other through this period, despite the restrictions.

The exhibition was accompanied by a family activity which encouraged young people to develop their own photography skills and document their experience of the pandemic through portraiture.

Set against the backdrop of the young Arboretum, Hold Still featured portraits of people who, in some way, had sacrificed for our country and community during the pandemic. Visitors to the exhibition were able to contemplate their own experience of lockdown and enjoy a socially distanced day out within the autumnal landscape.

Chris leads the Arboretum’s learning offer and yearround programme of exhibitions and commissions. Having studied fine art at the University of Oxford, he has curated exhibitions at galleries and public venues across the country, and has lectured at Birmingham City University and University of the Arts London.

below from left

© National Memorial Arboretum

Photo: Chris Ansell © NMA

Anna Maria Foster

Membership and Gift Aid Manager

2020 was a challenging year for everyone in so many ways. As the Gallery was preparing for the building’s redevelopment to begin in June 2020, the unexpected pandemic forced a national lockdown and the Gallery to close. Little did we know in March that we would be unable to reopen the much anticipated exhibitions David Hockney: Drawing from Life and Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things or that it would be the last chance to see the Collection in our galleries prior to the redevelopment work.

With many plans having to change, the pandemic has challenged us to find different ways to share the Collection. We have since showcased popular exhibitions online such as the BP Portrait Award 2020 and the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize 2020

In keeping with this new digital focus we have hosted a series of events that we hope you joined and enjoyed. These included a Virtual Drawing workshop inspired by John Singer Sargent portraits in collaboration with Raw Umber Studios; the Hold Still talk with Denise Vogelsang, Director of Communications & Digital, reflecting on her experience in delivering such an outstanding project; In Conversation with Simon Callow and Marina Warner in collaboration with The Daily Telegraph, to coincide with the launch of the Gallery’s latest publication Love Stories; and the talk with Ed Purvis, our Head of Collection Services, taking us through the fascinating removal of the Collection from

below Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh by an unknown photographer, 28 May 1937 (NPG x36099)

the Gallery walls. We will continue to share the recordings to watch or re-watch at your leisure.

The Gallery has been extremely fortunate to be able to count on your continued support. Thank you for joining us in this transformational journey that will allow us to welcome you back to a new inspiring building and Collection in 2023.

Spring offer for Gallery Supporters

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

BOOKS A

PREVIEW OF ICONS AND IDENTITIES

The Gallery’s upcoming publication Icons and Identities draws upon the exceptional collections of the National Portrait Gallery to investigate and celebrate the variety and complexity of the genre. It draws together the most famous faces from British history, from Queen Elizabeth I and Sir Isaac Newton to Audrey Hepburn and The Beatles, alongside less well-known sitters, presented through six interrelated themes that are at the core of portraiture’s fascination.

Fame explores the relationship between image and public renown; Power looks at the use of portraiture in promoting different forms of authority; Love and Loss reflects on the intimate connection between portraiture, affection and absence; Identity focuses on the diverse ways in which portraiture represents various identities; Innovation investigates the new ways of seeing and creating pioneered by significant portrait artists; and Self-Portrait provides an insight into what occurs when artists turn their critical gaze on themselves.

Icons and Identities, by Rab MacGibbon, edited by Tanya Bentley, accompanies a major international exhibition.

Available online only at npgshop.org.uk for pre-order, publishing 1 April 2021 priced at £19.95.

Gallery Supporters enjoy an increased discount of 20% in our online shop, including all new publications. Use code MEMBER2020 which replaces your Membership Number as the online discount code for all purchases.