FEATURE

HYPENOMICS: WHEN STREETWEAR REIGNS SUPREME By Oscar Miller

U

sually, the picture of young individuals camping out on the streets of London on a cold Wednesday night provokes feelings of sympathy. However, it’s not sympathy the long lines of hopeful campers on Soho’s Peter Street are seeking – it’s opportunity. These fashionconscious entrepreneurs, usually under the age of 25, are looking to get their hands on the newest range from New York streetwear brand Supreme. The brand has been successfully building ‘hype’ on social media for weeks in an attempt to add to demand which already greatly outstrips supply. Those able to successfully purchase items from limited weekly ‘drops’ boast both exclusivity and profitability, with some pieces selling on aftermarkets for nearly ten times their retail price. Consumers may queue for hours or even days, estimating what items will be ‘dropping’ and what sort of price they may be able to charge customers on the aftermarket.

Those able to successfully purchase items from limited weekly ‘drops’ boast both exclusivity and profitability, with some pieces selling on aftermarkets for nearly ten times their retail price. Firstly, it is important to look at the consumers driving this excess demand. Data from PwC’s Global Consumer Insights Survey revealed that consumers spend five times as much per month on streetwear than non-streetwear, despite 70% of consumers reporting an income of less than $40,000 a year (Leeb, Menendez and Nitschke, 2019). These consumers are primarily concerned with the conspicuous consumption of ‘status goods’, those which elevate social standing (Veblen, 1899). This is known as a ‘Veblen Effect’, where consumers use product price as a signal of wealth (Mason, 1992) and where utility is derived from societal perception. The diagram below (WallStreetMojo, 2020) 36

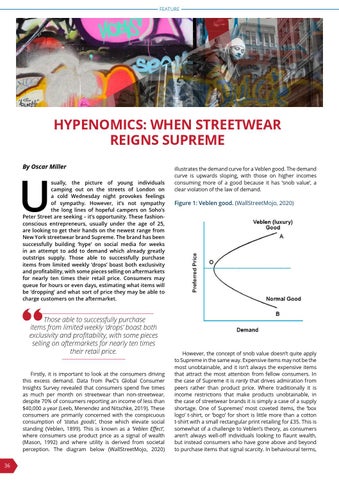

illustrates the demand curve for a Veblen good. The demand curve is upwards sloping, with those on higher incomes consuming more of a good because it has ‘snob value’, a clear violation of the law of demand.

Figure 1: Veblen good. (WallStreetMojo, 2020)

However, the concept of snob value doesn’t quite apply to Supreme in the same way. Expensive items may not be the most unobtainable, and it isn’t always the expensive items that attract the most attention from fellow consumers. In the case of Supreme it is rarity that drives admiration from peers rather than product price. Where traditionally it is income restrictions that make products unobtainable, in the case of streetwear brands it is simply a case of a supply shortage. One of Supremes’ most coveted items, the ‘box logo’ t-shirt, or ‘bogo’ for short is little more than a cotton t-shirt with a small rectangular print retailing for £35. This is somewhat of a challenge to Veblen’s theory, as consumers aren’t always well-off individuals looking to flaunt wealth, but instead consumers who have gone above and beyond to purchase items that signal scarcity. In behavioural terms,