1 minute read

Economic Freedom Indexes Promote Growth – But they Need to Change

ECONOMIC FREEDOM INDEXES PROMOTE GROWTH – BUT THEY NEED TO CHANGE

Dylan Grice

Advertisement

Economic Freedom Indexes promote growth – but they need to change

If economic freedom resembles Hong Kong or Chile as they currently appear, then one would be forgiven for finding it unattractive. Yet despite this, according to the Heritage Foundation Economic Freedom Index (EFI), or that of the Fraser Institute, or those of myriad other organisations, it would seem that this is perhaps how it appears in practice. Indeed, the Fraser Institute deems Hong Kong the freest country on earth. Singapore, a de facto dictatorship with a ‘meticulously planned economy’ (Marshall 2016) comes a close second. Chile comes 13th in the midst of its current protests (Gwartney, et al. 2019), and placed even higher in most EFIs when under the leadership of General Pinochet. Pinochet, of course, tortured and brutalised countless citizens, but duly ran a free market economy as per the guidance of the ‘Chicago Boys’ who advised him, educated at the University of Chicago by Milton Friedman (Sigmund 1983).

Each of these economies, past and present, suffers from vast inequality, and has shown on multiple occasions a willingness to suppress the political and civil rights of citizens. In 2015, Singapore jailed 16-year-old Amos Lee as an adult for posting a video criticising ex-leader Lee Kuan Yew. In 2019, Hong Kong attempted to curtail the civil rights of its citizens by introducing a bill allowing the extradition of the state’s political enemies to China, and brutally cracked down on public protest afterwards. It was withdrawn in September, but it now seems that China’s new national security law will be passed regardless. Chilean protests against inequality generally, triggered by higher subway fares, have been met by the government declaring a state of emergency, and the shooting and injuring of numerous protestors with rubber bullets.

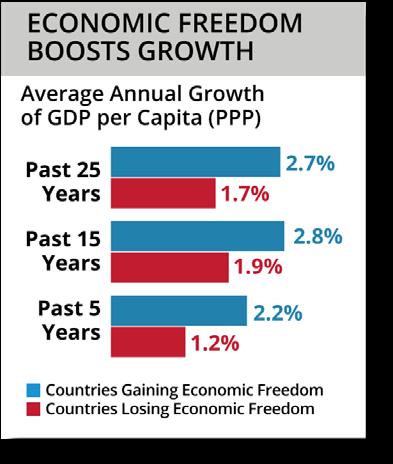

In most academic literature, however, it is widely accepted that the measures promoted and praised by such EFIs, when implemented by those countries aforementioned, among others, do promote domestic economic growth. Figure 1: (Miller, Kim and Roberts 2019)

Figure 1: (Miller, Kim and Roberts 2019)

There are some exceptions, such as South Korea and, historically, the USA, whom economist Ha-Joon Chang emphasises developed rapidly due to their distinct mercantilist protectionism (Chang 2011). However, Hong Kong and Singapore are revered as success stories of globalisation, and the material wellbeing of their citizens, even their poorest citizens in an absolute sense, has without doubt seen growth as a result of their opening up to free trade and their domestic embrace of policies promoting economic freedom, as defined by EFIs.

Let this article therefore, not be construed as antieconomic freedom, for the growth benefits that policies promoting such freedom can bring globally and domestically are clear. It must be recognised though, that a paradox exists, whereby many of those countries that have embraced economic liberalisation measures to enrich some of their populace economically, have seen unrest due to the civil, political and occasionally economic repression of sections of that same populace.

This paradox has emerged due to the fact that EFIs’ narrow definition of economic freedom is inadequate for measuring the extent to which the economic growth brought about by increased liberalisation generally, actually benefits most of the general populace of the aforementioned countries, and for measuring the extent of the freedom it brings the individuals within them. Hong Kong’s macroeconomy is a prime example of this; in a country with an GDP per capita in excess of $60,000 (Miller, Kim and Roberts 2019), the Gini coefficient (a measure of inequality), sits at over 0.5. For context, the next highest Gini coefficient amongst developed countries, other than Singapore which will be addressed later, is the USA’s score of 0.41, and in most of Western Europe it sits in the 0.2s (World Population Review 2020). Indeed, such high levels of inequality can be a natural result of development, as originally displayed to us by the Kuznets curve, which displays a concave relationship between growth and inequality that emerges as a country develops (Kuznets 1955). However, with a GDP per capita more than double that of Britain, it is hard to argue that such levels of inequality continue to enhance freedom in countries such as Hong Kong. It is no wonder, therefore, that along with the political repression brought about by the lack of democracy and civil liberties afforded to its citizens, there is discontent amongst many people at the way in which the country is governed.

On a micro scale, we can see a further explanation for the emergence of this paradox when looking at Singapore’s labour market. The Heritage Index of Economic Freedom affords Singapore the crown of presiding over the freest labour market on earth (Miller, Kim and Roberts 2019). There is no doubt that the significant liberalisation methods pursued by the country, making hiring and firing easier and allowing workers to constantly move to the jobs in which they have the highest marginal product, have led to increased economic growth, and the enrichment of many citizens. Furthermore, it is clear that such measures have increased economic freedom in a narrow sense, since workers can move from job to job with little friction. Nevertheless, Singapore, with its GDP per capita of $93,906 per annum (Miller, Kim and Roberts 2019), has no minimum wage, and no unemployment benefit (Zaobao 2011). Thus, one must clearly question how truly free individual Singaporean labourers are, even if Singaporean labour is free as a collective, with no government enforced safety net to ensure that all workers have adequate bargaining power with employers. Perhaps it is thus unsurprising that Singapore has a Gini coefficient of 0.458 (World Population Review 2020). Indeed, the freedom of the individual labourer to choose between a sub-optimal job, and destitution, is no real freedom at all. All the liberalisation measures in the world could not truly free most of the populace to control their labour, without adequate social security measures to match.

Why is it, therefore, that EFIs so narrowly define the notion of economic freedom so as not to account for the security of workers, which serves in many countries to enhance their freedom? Partially, it is a data collection issue. It is difficult to define social mobility, or the extent to which individual workers have control over their own labour. However, there are subjective measures throughout the rankings of each of these EFIs. Much like the parable of the dishonest waiter, whose bill calculations always seem to favour himself, the nature of these subjective measures always seems to favour a world-view that looks to prioritise the freeing of markets, rather than the freeing of the individuals who act within them. A freedom that could be brought about through adequate security measures and perhaps through the imposition of the democratic elections that would most likely bring them about.

This is due to the fact that most EFIs, whether they be that of the Cato, Fraser or Heritage Institutes, are published by free market think-tanks who come under the guidance of the libertarian Atlas network, funded by the Republican Koch brothers in the USA (Lawrence, et al. 2019). Furthermore, the Fraser Institute Economic Freedom of the World Index was devised by the Mont Pelerin Society, which included the likes of Friedrich Hayek, the Austrian economist, and Milton Friedman, as notable members (Slobodian 2019). As aforementioned, Friedman played a pivotal role in devising and implementing the economic policies of the ‘Chicago Boys’ in Pinochet’s Chile in the 1980s, and thus it is perhaps unsurprising that the index itself rewarded such policies at the time, and has rewarded similar policies in its rankings ever since.

Clearly, therefore, the evidence does suggest the measures to promote economic freedom employed by those countries atop most EFIs do promote growth and prosperity. One only needs to survey the GDP per capita levels of Singapore and Hong Kong for confirmation. However, if EFIs want to be truly representative of the individual freedom held by each member of the citizenry of such countries, rather than being representative of a particular worldview, extra measures are required to enhance their ranking systems. None of the Fraser, Heritage or Cato Institute’s list democracy as an enhancer of economic freedom, as studies in political economy have shown it to be (Spindler, de Vanssay and Hildebrand 2008). Indeed, the hypothesis of one Milton Friedman’s book, ‘Capitalism and Democracy’, implies that the freest countries of earth should necessarily be democracies, as economic freedom brings with it political freedom (Friedman 1962). Furthermore, a fairer, more equitable EFI would mark countries down for proliferating inequality through policy, as measured through easily obtainable Gini coefficients. If such changes were given sufficient weight, one suspects that the rankings currently manufactured by these indexes would change drastically. Perhaps drastic change is exactly what is required.

References

Chang, Ha-Joon. 2011. 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism. Penguin Books.

Friedman, Milton. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gwartney, James, Robert Lawson, Joshua Hall, and Ryan Murphy. 2019. Economic Freedom of the World: 2019 Annual Report. Fraser Institute.

Kuznets, Simon. 1955. “Economic Growth and Income Inequality .” American Economic Review 1-28.

Lawrence, Felicity, Rob Evans, David Pegg, Caelainn Barr, and Pamela Duncan. 2019. “How the Right’s Radical Thinktanks Reshaped the Conservative party.” The Guardian, November 29.

Marshall, Colin. 2016. “Sinagpore - The Most Meticulously Planned City in the World.” The Guardian, April 21.

Miller, Terry, Anthony B. Kim, and James M. Roberts. 2019. 2020 Index of Economic Freedom. The Heritage Foundation.

Sigmund, Paul E. 1983. “The Rise and Fall of the Chicago Boys in Chile.” SAIS Review.

Slobodian, Quinn. 2019. “Democracy doesn’t matter to the defenders of ‘economic freedom’.” The Guardian, November 11.

Spindler, Zane A., Xavier de Vanssay, and Vincent Hildebrand. 2008. “Using Economic Freedom Indexes as Policy Indicators: An Intercontinental Example.” Public Organisation Review 195-214.

World Population Review. 2020. Gini Coefficient by Country 2020. January 13. http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/gini-coefficient-by-country/.

Zaobao, Lianhe. 2011. Minimum Wage Cannot Work. January 27. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-replies/2011/ minimum-wage-cannot-work.