At the Heart of the Indo-Pacific:

India's Maritime Strategy in the Rimland

Musharraf Khan

Spykman's Rimland theory, developed in 1944, argued that

control over the maritime edges of Eurasia shapes global power (Spykman, 1944). More recently, Kaplan (2012) has described the region as a "fulcrum" for global competition. In the contemporary Indo-Pacific, both logics retain their strategic relevance, as states from Australia and Indonesia to Japan and more play decisive roles in regional economic and political dynamics. However, India sits at the heart of this arc, geographically central and strategically indispensable. Despite this, its influence continues to fall short of expectations. Medcalf (2020) highlights that New Delhi's inconsistent Indo-Pacific engagement, especially compared to smaller states that outperform expectations is down to a lack of resources. However, the roots of this underperformance run deeper, stemming from an amalgam of strategic inertia, institutional bias, and a lingering land-centric mindset. This paper examines these structural and strategic gaps in India's maritime posture, drawing on defence budgets and regional alignments to assess current trajectories, and outline potential pathways forward.

Inertia at Sea

India's geographic position offers a maritime advantage that few states can match. Situated at the confluence of major shipping lanes in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal, it occupies a pivotal position in regional trade and security architecture. Yet despite this strategic centrality, India's defence priorities remain overwhelmingly focused on land-based threats. Over 90% of its trade is seaborne, yet the Navy received only 17.5% of the FY 2025-26 defence budget (Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways, 2024; Ministry of Defence, 2025), while the Army accounted for 54.6% of total allocations. Naval planners had sought an additional $9.6 billion for modernisation initiatives, including the

Musharraf is an independent geopolitical analyst with a BSc in Mathematics and two years of intensive study in Political Science and International Relations (PSIR). His research interests include maritime strategy, historical power politics, and the evolving security landscape of the Asia-Pacific region. Combining empirical depth with narrative insight, his work seeks to challenge conventional frameworks and contribute a critical, accessible voice to contemporary debates in international affairs.

acquisition of a second aircraft carrier and upgrades to the Andaman and Nicobar Command - a strategically located outpost near the Malacca Strait that remains underutilised despite its regional significance - yet it remained underfunded by an approximate $2 billion (Lok Sabha Secretariat, 2025). This funding gap reflects an institutional inertia rooted in a strategic culture shaped by historical land conflicts (Pant & Joshi, 2020).

This strategic orientation is reflected clearly in parliamentary discourse, where maritime concerns receive minimal attention. Debates in the Lok Sabha in March 2025 focused on border fencing and troop deployments, with naval priorities largely absent from the agenda (Lok Sabha Debates, 2025). While opposition members - including opposition party MPs questioned the Navy's funding cuts, defence officials reiterated that escalating tensions along the Chinese border constituted the "real" threat. This land-centric orientation also permeates India's maritime doctrines, including Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) and the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI). While these frameworks articulate ambitions of regional leadership, they are undermined by limited funding and a lack of clearly defined strategic red lines (Medcalf, 2020). The result is a cautious, slow-moving posture that renders India's maritime ambitions more

through India Gate, NewDelhi

declaratory than operational.

Part of the challenge lies in the relative invisibility of maritime threats, which seldom provoke the urgency or public pressure triggered by visible land incursions. In a political landscape shaped by nationalist sentiment, the visibility of a threat plays a central role in sustaining the state's strategic legitimacy. This underestimation has led to persistent operational gaps, particularly in strategically sensitive regions like the Andaman Sea. In 2019, a Chinese hydrographic vessel entered India's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) near the Nicobar Islands (Economic Times, 2022). Since then, such incursions have continued, with Chinese vessels reportedly sighted again as recently as May 2025.

At the heart of this maritime inefficiency lies the Andaman and Nicobar Command (ANC), established in 2001 to serve as a strategic outpost. Despite its proximity to the Malacca Strait (one of the world's most critical maritime chokepoints) the ANC remains under-resourced and lacks independent budgetary authority (Pant & Joshi, 2020). In contrast, China enforces its EEZ with assertiveness, projecting a clear posture and calibrated deterrence. India's presence in the eastern Indian Ocean, by comparison, remains strategically ambiguous, withoutwell-defined red lines or rapid response protocols. Left unaddressed, this passivity threatens to erode New Delhi's standing in a region central to its envisioned Rimland role.

China's Rimland Gambit: Encirclement Through Infrastructure

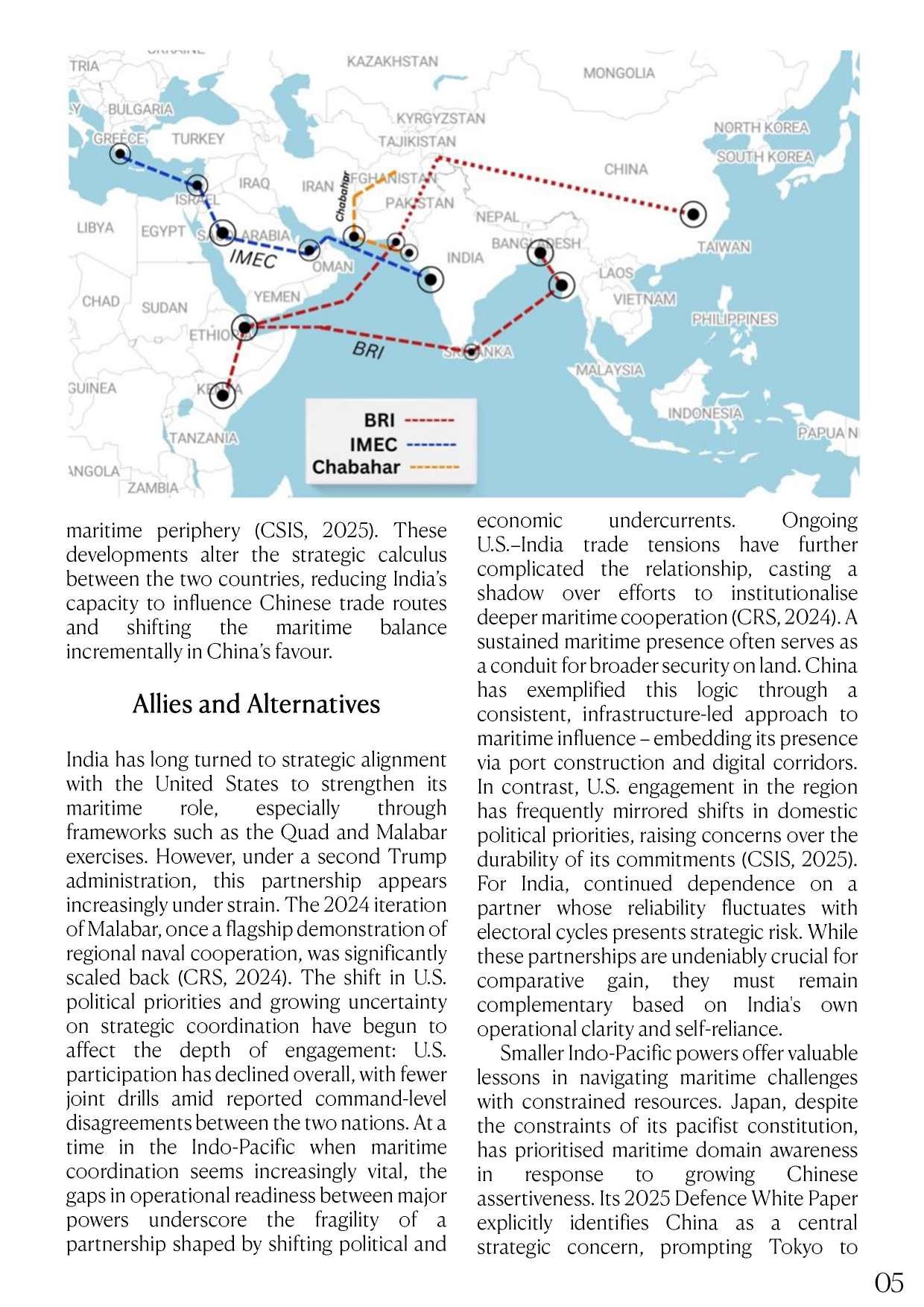

Over the past decade, Beijing has pursued a deliberate Rimland approach through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), constructing a chain of dual-use ports (Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Kyaukpyu in Myanmar, and Djibouti) expanding its influence across the Indian Ocean (Rolland, 2020). In August 2022, Chinese research

vessels, some reportedly linked to the PLA Navy, docked at Hambantota under theguise of "oceanographic cooperation." India offered little response, effectively allowing Beijing to map undersea terrain and monitor maritime activity within its Exclusive Economic Zone (HT, 2022). While it is plausible that overt retaliation can jeopardise regional diplomatic ties or overstate the immediacy ofthe threat, India's inactivity reflects a broader hesitancy to challenge China's incremental assertiveness in the maritime domain.

These developments reflect part of a broader move to consolidate influence in a strategically crucial region. By embedding itself in the infrastructure of India's maritime periphery, China is steadily eroding New Delhi's ability to project power and shape regional outcomes. In contrast, India's current maritime strategy has lacked a cohesive counter, being unable to match China's pace of infrastructure diplomacy. New Delhi has sought to respond through initiatives such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) and investments in the Chabahar Port in Iran (Defense News, 2025). However, both efforts have been faltering: the IMEC remains limited by stymied Gulf investment over long-term viability, while Chabahar intended as a strategic outpost in Iran - has been eclipsed by China's deeper engagement at the nearby Jask Port.

Located just 300 kilometers from Chabahar, China's growing presence at Jask Port (reportedly being prepared for joint drillswith Iran) marks a more direct challenge to India's influence in the Arabian Sea. In parallel, the development of the Kyaukpyu-Yunnan pipeline offers Beijing an overland energy corridor, reducing its reliance on the Malacca Strait and thereby weakening one of India's few strategic pressure points in the region (Pant & Joshi, 2020). A similar rationale is applied to China's 'Digital Silk Road' project, with the laying of undersea cables near Indian island territories introducing an additional layer of strategic encirclement close to India's

BULGARIA KYRGYZSTAN GREECE

ANGOLA

Chabahar ZAMBIA

maritime periphery (CSIS, 2025). These developments alter the strategic calculus between the two countries, reducing India's capacity to influence Chinese trade routes and shifting the maritime balance incrementally in China's favour.

Allies and Alternatives

India has long turned to strategic alignment with the United States to strengthen its maritime role, especially through frameworks such as the Quad and Malabar exercises. However, under a second Trump administration, this partnership appears increasingly under strain. The 2024 iteration of Malabar, once a flagship demonstration of regional naval cooperation, was significantly scaled back (CRS, 2024). The shift in U.S. political priorities and growing uncertainty on strategic coordination have begun to affect the depth of engagement: U.S. participation has declined overall, with fewer joint drills amid reported command-level disagreements between the two nations. At a time in the Indo-Pacific when maritime coordination seems increasingly vital, the gaps in operational readiness between major powers underscore the fragility of a partnership shaped by shifting political and

economic undercurrents. Ongoing U.S.-India trade tensions have further complicated the relationship, casting a shadow over efforts to institutionalise deeper maritime cooperation (CRS, 2024). A sustained maritime presence often serves as a conduit forbroader security on land. China has exemplified this logic through a consistent, infrastructure-led approach to maritime influence - embedding its presence via port construction and digital corridors. In contrast, U.S. engagement in the region has frequently mirrored shifts in domestic political priorities, raising concerns over the durability of its commitments (CSIS, 2025). For India, continued dependence on a partner whose reliability fluctuates with electoral cycles presents strategic risk.While these partnerships are undeniably crucial for comparative gain, they must remain complementary based on India's own operational clarity and self-reliance.

Smaller Indo-Pacific powers offer valuable lessons in navigating maritime challenges with constrained resources. Japan, despite the constraints of its pacifist constitution, has prioritised maritime domain awareness in response to growing Chinese assertiveness. Its 2025 Defence White Paper explicitly identifies China as a central strategic concern, prompting Tokyo to

expand its ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) coverage into the South China Sea (Japan Ministry of Defense, 2025), with further deployments to the Philippines and Vietnam. Compared to India, this reflects a more synchronised approach across its political, and operational levels, enabling swift and consistent maritime responses in contested spaces.

Clarity ofpurpose and consistent engagement can still yield meaningful results

Similarly, Indonesia presents a compelling and effective example of how smaller powers can project maritime resolve without relying on an overwhelming or heavily-funded use of force. In recent years, Jakarta has consistently defended its rights around the Natuna Islands, a region where Chinese fishing vessels and coast guard patrols have increasingly tested Indonesia's claims to statehood. While Indonesia undoubtedly lacks the scale of India's naval power, it has leveraged partnerships with countries such as Japan and Australia to reinforce its maritime position via joint exercises, capacity-building initiatives, and diplomatic signalling (Medcalf, 2020; The Jakarta Post, 2024). This integrated and proactive approach differs from India's more cautious maritime posture, where efforts such as the NC31 (National Command Control Communication and Intelligence Network) modernisation programme remain under development.

While structural factors such as population size, geography, and institutional capacity naturally shape strategic outcomes, these alternative cases suggest that clarity of purpose and consistent engagement can still yield meaningful results. For India, this highlights the importance not only of expanding capabilities, but of aligning them with a coherent and regionally attuned maritime strategy.

The Case for Strategic Correctives

India's maritime limitations stem less from a lack of awareness than from longstanding institutional preferences. The country's continental focus rooted in repeated conflicts along its northern borders - has understandably driven resource allocation toward land-based capabilities. However, as the Indo-Pacific emerges as the principal theatre of geopolitical competition, a gradual rebalancing of defence allocations (towards a 40-30-30 split across the Army, Navy, and Air Force by FY 2027) would represent a significant strategic recalibration (Ministry of Defence, 2025). Such a reallocation would not only reflect changing strategic realities, but also provide the naval arm with the resources needed to operate credibly in contested waters.

A crucial corrective inthat respect would be to define and communicate clear maritime red lines, particularly around the Andaman Sea and critical Exclusive Economic Zones. These would need to be communicated through diplomatic channels and supported by operational readiness, with an emphasis on signalling deterrence rather than escalation. The Andaman and Nicobar Command (ANC), given its geographic importance, has been identified by some analysts as a candidate for transition into a fully integrated Maritime Theatre Command (Pant & Joshi, 2020). Similarly, the Indian Ocean Port Partnership (IOPP) may also warrant further development as projects involving co-developed ports in locations like Sri Lanka or Mozambique have been discussed as possible avenues for enhancing regional presence, though their implementation depends on a range of political, financial, and logistical factors (CSIS, 2025).

There is no denying that, as regional competition deepens, the Indo-Pacific has emerged as a primary theatre ofgeopolitical activity. While India's strategic geography offers considerable advantages, the extent to

which this translates into sustained maritime influence remains an open question. Revisiting strategic priorities at sea may offer states like India not only a means to reinforce their regional role, but also to engage more credibly with alternative coalitions in shaping multipolar outcomes. As Spykman observed decades ago, the power that commands the Rimland holds the keyto global order.

References

Center for Strategic and InternationalStudies. (2025). Making infrastructure in the Indo Pacific a success. CSIS.

Congressional Research Service. (2024). Quad military integration challenges (CRS Report No. R47588). CRS.

Defense News. (2025, February 14). China, Iran, and Russia hold joint naval drills in Mideast. Japan Ministry of Defense. (2025). Defense of Japan: Annual white paper.

Lok Sabha Secretariat. (2025, March). Standing Committee on Defence: Demands for grants 2025-26. Lok Sabha.

Ministry of Defence, Government of India. (2025). Union budget 2025-26: Defence services demands for grants.

Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways. (2024). Annual report on maritime trade 2023-24. Government of India.

Pant, H. V.,& Joshi, Y. (2020). India's strategic shift and maritime reordering. International Affairs, 96(5), 1245-1262.

Rolland, N. (2020). China's Maritime Silk Road initiative: Economic drivers and strategic implications. The China Quarterly, 243, 903-933.

The Jakarta Post. (2024, October 12). Indonesia expels Chinese vessel from Natuna waters, affirms sovereignty.

Kaplan, R. D. (2012). The revenge of geography: What the map tells us about coming conflicts and the battle against fate. Random House.

Medcalf, R. (2020). Indo-Pacific empire: China, America and the contest for the world's pivotal region. Manchester University Press. Spykman, N. J. (1944). The Geography of the Peace. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Hindustan Times Post. (2022, August 16). Chinese vessel reaches Sri Lanka amid concerns in India. Economic Times Post. (2022, Nov. 06).Navy plans to stop Chinese spy ship from entering India's exclusive economic zone.