A Women’s Building Manifesto

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the attendees, staff, trustees, volunteers and leaders of the sixteen women’s organisations that contributed to this manifesto. These organisations welcomed us in on visits, took part in interviews, conferences and collage workshops, and shared their time, experience and expertise.

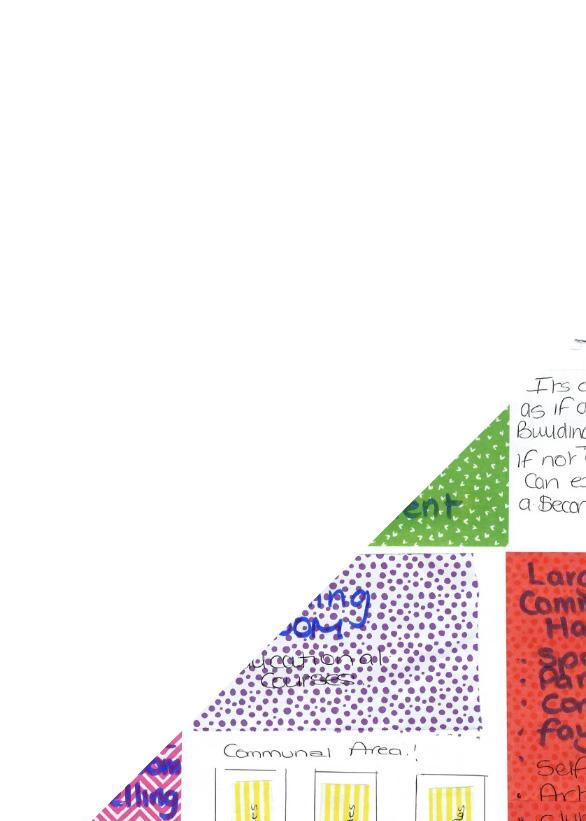

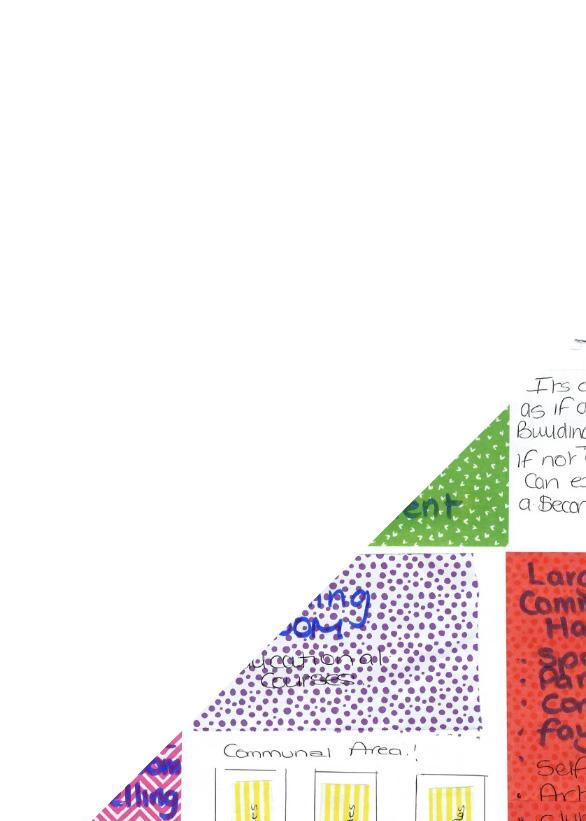

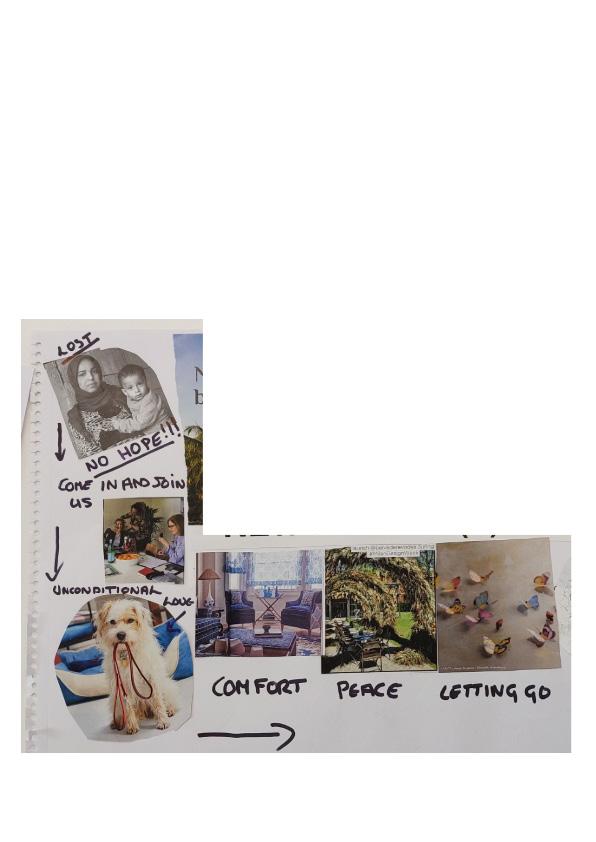

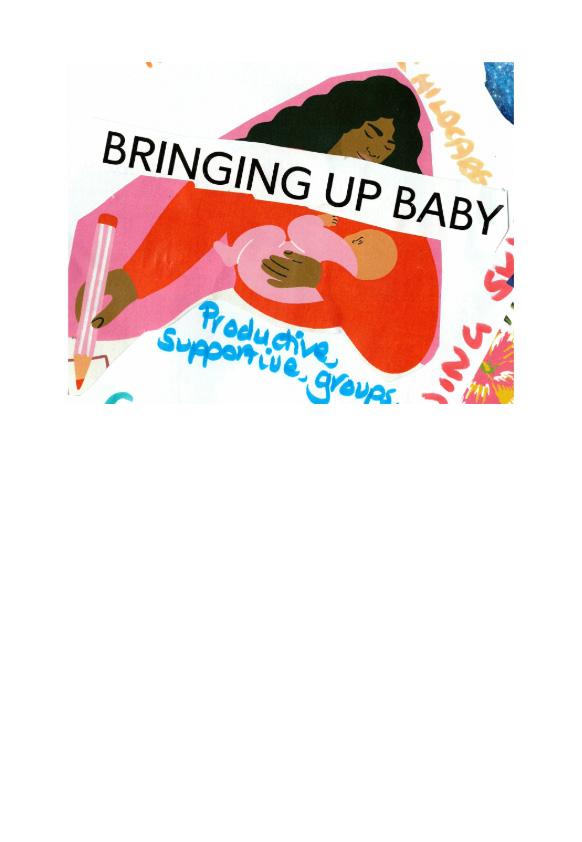

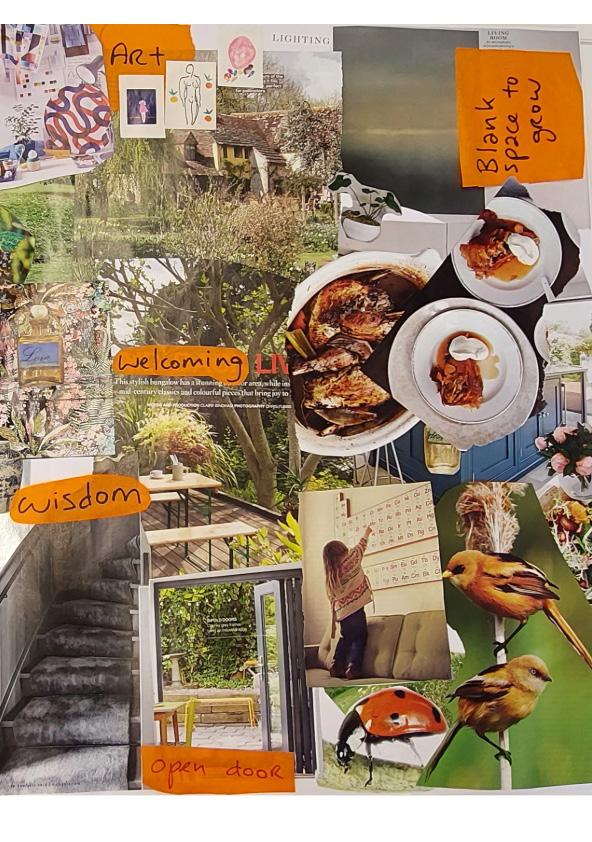

All art work was produced by women during the collage workshops.

Writing by Carly Guest and Rachel Seoighe, drawing on the ideas, experiences and imaginations of all the women we spoke to.

The creation of this manifesto was funded by the Independent Social Research Foundation Small Grant Award for the project Transformative Justice for Women.

Introduction

This manifesto offers a vision of a transformative women’s building, bringing to life the ideas and work of women who attend, staff and lead women’s buildings across the UK.

This manifesto draws on visits to five Women’s organisations across the UK, on collage workshops with three groups of women, on interviews with five organisation leaders, and on a women’s building conference attended by representatives of nine women’s buildings, incorporating a world café discussion and collage workshop. We use the language of ‘women’s building’ to emphasise the significance of the physical space to the work these UK based organisations do.

This manifesto draws on the wisdom, experience and knowledge of these women to suggest ways that women’s organisations can create transformative, healing spaces for restoration, recovery and growth. The women’s buildings consulted have each, in different ways, created a community and network of support that recognises the deeps harms experienced by women in patriarchal societies and creates a space for challenging social harm through care, recognition and healing. Each operates in different ways, with varying focuses on, for example, one to one counselling, arts and crafts, community engagement, youth clubs, campaigning and advocacy, and the needs of racially marginalised women or young women.

All are healing spaces. They are places that respond to the needs of women, creating the conditions and opportunities for healing, transformation and growth. They are governed, developed and sustained in line with feminist principles, and invest in a vision of the present and future where women are supported, cared for and empowered.

Many of the women who attend the women’s buildings have had experience of and have been harmed by punitive systems and institutions. The buildings provide alternative, non-punitive communities founded in trauma-informed principles and practice.

This manifesto is structured around the following four principles of transformative justice, reflecting the organisations’ shared commitment to creating safe, caring, supportive spaces and communities for women:

• Building Capacity

• Holistic Approaches

• Healing Emotionally and in Community

• Safe and Non-Punitive design

It considers the challenges faced by women’s buildings and their transformative effects on the lives of women, communities and society.

The manifesto invites you to reflect on, respond to and be inspired by women’s buildings as a movement towards transformative feminist futures.

Core Principles

The following pages set out some core principles that guide the work of women’s organisations. Strategy, governance, funding, provision and delivery should all align with the core principles.

TENDERNESS HEALING CARING

CULTURALLY SENSITIVE

ANTI-RACIST COURAGEOUS LOVING TRUST

COLLABORATIVE

HOPEFUL FEMINIST

INTERVENTION

CHOICE

WELLBEING

RIGHTS FOCUSED

Building Capacity

For a women’s building to grow, and to be sustainable and function as needed, consideration needs to be given to funding models, staffing and governance structures, and how practice aligns with organisational principles. Organisations build capacity in innovative waysinternally and across the sector.

A clear funding model that meets the needs of the organisation is key; a cohesive funding strategy and a long-term plan, rather than an ad hoc or unplanned approach, offers more financial security. Whilst diverse funding streams, such as statutory, corporate, grant, trading and philanthropic funding can create multiple sources of income, relying on multiple funding pots can be complex and precarious. Some funding (often private or corporate) offers more flexible, unrestricted funds not linked to particular activities or outcomes.

Creative and diverse funding models can allow women’s buildings to build capacity in different ways. Buildings that have a number of organisations within it might view the finances of each as operating separately or could adopt a collective funding model where each organisation contributes to a funding pot according to its resources and capacity.

Relationships with funders are key: demonstrating the positive work of the building and the impact on women’s lives, through evaluations and funder visits, can be critical to developing long-term relationships with funders. These relationships can also bring expertise, volunteering and awareness raising, which can sometimes be more valuable than money. Some organisations might consider cocommissioning models that offer a collaborative approach between the public sector, organisations and citizens to resource a holistic service.

The wealth of knowledge and expertise within the building might also generate a funding stream. Providing training to other organisations, such as private, third sector and statutory services might form part of a trading model. This can offer independent income streams outside of the funding/grant model that dominates the sector. Shops and cafés might generate some income, but their greater value is in offering a contact point for women, and opportunities for developing skills and work experience.

Building organisational capacity requires a clear governance and staffing model that provides support and resources to a knowledgeable and dedicated staff and trustee group.

Trustee expertise should reflect the needs and focus of the service. Trustees with lived experience on the board ensure that women’s experiences and needs are centred in strategic planning and delivery. Lived experience is also invaluable on the staff team. Women might follow a path of accessing services, volunteering and training to then bring a deep understanding of the organisation that enriches strategy, focus and operations.

The building itself can foster a staff culture that is supportive and sociable and offers opportunities for learning and development. This can be achieved through formalised routes such as training, supervision and employee support programmes, and through informal moments of socialising, sharing and fostering a staff team that feels collegial, well supported and valued. A dedicated office manager who has oversight of the function, operation and administration of the building is invaluable.

Organisational strategy should be responsive to the needs of women, with women’s ideas and suggestions for development considered and incorporated where possible. Grant funding can be used to trial specific projects and test out new ideas before incorporating them fully. Co-production can be embedded into the design and operation of the building. Similarly, being visible in the community creates opportunities for engaging with women who might be future users of the building.

Working with other women’s organisations –providing support and expertise, collaborating on projects, sharing good practice – can be a means of learning from others in the sector and receiving guidance from those who have already developed projects, governance or financial models of interest.

Women’s buildings are at the forefront of meeting and responding to women’s needs in a trauma informed way, with detailed knowledge and understanding of the inadequacies and retraumatising impact of much policy and practice.

Campaigning and awareness raising, training external organisations and engaging with local and national government and other stakeholders can be avenues to creating systemic change.

Holistic Approaches

A women’s building will meet women where they are on their journey, offering both immediate and long-term support. A woman will not be perceived or treated as a problem; she will be welcomed with care and without judgment.

There are many ways for women to find the building, for example, through a regular drop-in, a website, social media, a helpline or community outreach. There might be ambassadors out in communities, including in rural areas, and women can be referred to the women’s building through other services. The women’s building training team can ensure that all referrers and staff are trauma informed in their approach.

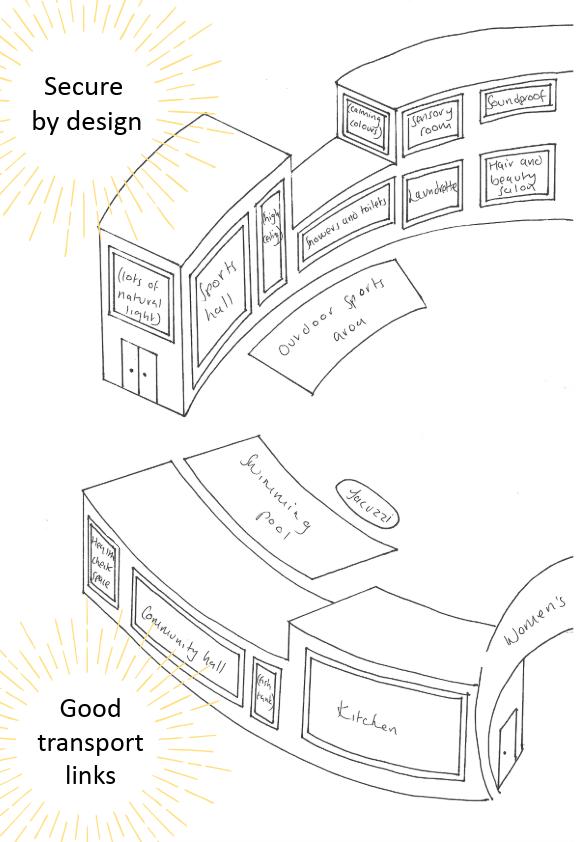

Getting to the building should be easy: it should be in a central location, with good transport links. As a multi-purpose space, women may come to the building for many reasons. This reduces stigma and allows for joined up working: a holistic casework model that sees the woman as a whole person and helps her to address any and all issues in her life. Other specialist organisations might visit or have a presence in the building, and staff can carefully connect women to other services. Staff with lived experience, who may have previously found support through the building themselves, will treat the woman with care and empathy.

Childcare and play areas might be provided so that women can speak to staff, take part in activities and go to appointments whilst their children are cared for. In terms of immediate or urgent need, a women’s building could offer toiletries and sanitary products. Meals can be provided – for women and their childrenand there might be a food bank. Staff can help women to find emergency accommodation, including domestic violence refuges. There might be a health check space, with access to a GP and a pharmacy.

Women can be supported with practical administration – with benefits, budgeting, housing support, tenancy advice and immigration advice. Simply helping women to fill out forms can reduce anxiety and allow women to focus on healing.

With a one-to-one, personalised way of working, a holistic caseworker can design a programme of support and connect women with specialised services. This might include support with substance use, sexual, mental and physical health needs and domestic abuse. Organisations should find ways to ensure that all women are supported and feel safe.

Women might require support navigating the criminal justice system. The organisation might meet women at the prison gates and offer support beyond, including to women at risk of breaching their licence, helping to keep them out of prison. Family law advice might be available and emotional support for women who are at risk of or have experienced child removal.

Practical skills are essential for women to build new lives. A women’s building might teach IT skills, offer DIY courses and cooking classes, as well as presentation, public speaking and English language skills. Accredited training can set women on the path to employment, and pathways from volunteering to employment might be established. Specialist employment guidance for women leaving the criminal justice system might be offered.

A holistic approach is practical, physical, emotional and connected. Women are supported on their healing journeys in a longterm and reliable way.

Healing:

Emotionally and in Community

Women’s buildings help women to heal and reshape their lives. They are supported to process their traumas and connect with their emotions, to build healthy relationships and to create community, both inside and outside the building.

Women’s buildings facilitate healing through counselling and trauma courses, yoga and meditation, and sensory and wellness spaces. They facilitate group work and discussion –including peer-facilitated groups – creating space for women to share their experiences, connect with others and feel heard. Women might be invited to learn about consent and to recognise patterns of abuse.

Women’s buildings facilitate healing through counselling and trauma courses, yoga and meditation, and sensory and wellness spaces. They facilitate group work and discussion –including peer-facilitated groups – creating space for women to share their experiences, connect with others and feel heard. Women might be invited to learn about consent and to recognise patterns of abuse.

Women can rebuild their confidence and wellbeing through reflective courses, practices of care, and pampering and grooming. The building can give women the tools to help themselves, to feel equipped and capable. Tending to themselves and being tended to can help women heal.

Creating a healing space that is calming, relaxing, vibrant, warm, friendly and inviting involves all the senses. The colour, sounds, smells and feel of the building can create a welcoming and nourishing atmosphere.

There might be outdoor, green spaces, water and animals. There might be natural light, and a warm, airy environment. Quirky spaces with relaxing décor can delight and surprise.

Quality furnishings reflect the value the women deserve and are afforded. Women are celebrated in the space: their stories of growth, healing and support visible on the walls, alongside inspirational histories of women’s organisations, campaigns and achievements.

Women are also an invaluable support to one another. The organisation might recognise this by establishing a ‘champion’ role where women can support other women and advocate for them.

Women should feel that the building belongs to them. This sense of belonging needs to be consistently created, as the women will change all the time. The staff should ask women to reflect on what they need, on what they want the space to be, and they will listen. When moving on, women might be encouraged to choose an object or gift to leave for the next woman.

Healing can also look like engaging in public life – women might be encouraged to vote, to speak with stakeholders and advocate for themselves and others. Meaningful support should be offered to women who want to share their lived experience to bring about change. Women’s buildings should support women to build community outside the space and always welcome them back.

Safe and Non-punitive Spaces

Creating a safe and non-punitive environment is vital for welcoming women who may have had experience of punitive systems and institutions, such as the criminal justice system. Safety should be at the heart of building design.

It might take time for women to come through the door of a women’s building and even longer to feel confident and safe enough to access support or share their story. Buildings can echo this pathway by designing a non-confrontational, nonintimidating entry point, such as a charity shop or café. This creates space for women to chat to staff and find out more about the activities and support available within the building. Women might then progress through the building, accessing practical support, engaging in activities and building relationships until they feel confident and safe enough to share their support needs.

A welcoming and friendly space where women are treated with respect, rather than viewed as a problem, is critical to a non-punitive approach. The building might have no or very few rules, with issues and challenges managed within the community. Organisations can find ways to encourage women to respect the space, to care for and feel responsible for the shared environment. There might be regular meetings to discuss issues that come

Everyone in the building can be asked to take accountability for actions that cause harm, but with a focus on repair, growth and return.

Security considerations include decisions about how visible the building is and how widely its purpose is advertised. Organisations need to be easily found by women in need and want to create a welcoming space for women. They also need to be security-focused, cautious of the risk of women’s abusers arriving at the doorstep. It is a difficult balance to strike. While there are benefits to public facing spaces, such as cafés and shops, there are also safety compromises to be considered.

Detailed thought should be given to the use of the physical space to ensure that a sense of safety and confidentiality is not compromised. Warm and welcoming signage, for example, can encourage women who need support to attend the building, but might also risk intrusion or alert perpetrators to its location. Organisations should consider these factors when decided on their external signage and design, and visibility in the local community. Where women’s organisations are associated with the criminal justice system – probation for example –careful thought needs to be given to the visibility of this relationship to ensure women do not feel stigmatised.

Women’s organisations need to consider the security of the building to protect women’s physical safety. However, there is a risk that security features might be reminiscent of harmful, punitive environments, therefore undermining women’s sense of safety and an environment of healing. Drawing on trauma informed design can help organisations avoid replicating punitive environments, whilst ensuring the building is ‘secure by design.’

Embedding safety features into the design of the building, particularly if planned in consultation with women, can maintain the balance between security and feelings of safety.

Given preconceptions about women accessing the building and a perceived need for a risk averse approach, punitive mindsets might need to be challenged and disrupted during the design process.

Features of 'secure by design' buildings might include keypads on doors, controlled access, buzzers, panic buttons, and automatic lighting. Each of these can create a conflict between the need for security and the need to create a safe and welcoming space. Organisations should consult with women throughout the design process to ensure that this balance is reached as far as is possible.

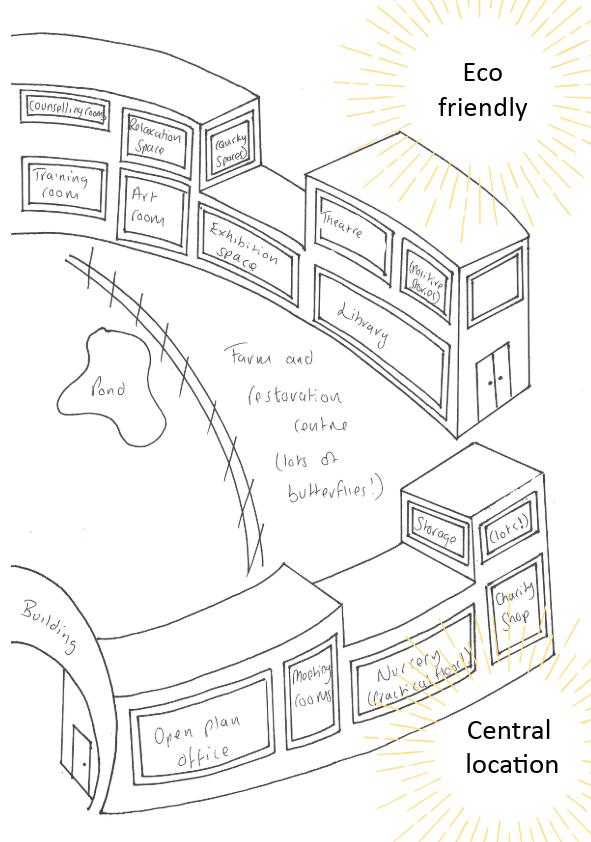

A Women’s Building

The Women’s Building overleaf is a depiction of all the elements the women who contributed to this manifesto said were needed in a transformative women’s building, with no restraint on imagination.

You are invited to colour and decorate this image to create your own women’s building. How do you want it to look, smell, feel?

Challenges

Running a women’s building is beautiful and challenging. Transformative work happens in the space despite structural challenges including funding, recruitment and the everyday maintenance of the building.

Funding is a constant challenge, particularly securing funding for core costs. Staff are losing sleep about the sustainability of their organisations. Funding is currently siloed and specific to particular contracts or pieces of work, when organisations need it to be flexible and holistic. Many organisations take up contracts with statutory services, which are restrictive and often poorly set up. Policy-makers and civil servants design contracts – and broader systems – in a way that is unworkable. An onthe-ground understanding of how women’s organisations work is missing, one that values long-term support and the less tangible impact of the work.

Organisations are resistant to taking outcome-based or payment-by-results contracts, as women’s journeys can be complex and non-linear. Some, for example, refused to be part of the disastrous Transforming Rehabilitation programme of probation reform, which left them ‘in the wilderness’ for years in terms of funding.

Engaging with policy-makers and politicians takes time, and can often be fruitless and circular: progress is reversed and the work begins afresh when staff and governments change. Working with the police and with other statutory agencies is also challenging. Organisations can soften the impact of women’s journeys through the criminal justice system by, for example, providing a place for community sentences to be served, where women can benefit from their holistic casework model. However, the contracts and funding for doing this work do not always reflect the resources required from the organisation.

Organisations need to build up reserves to ensure stability, but these reserves can work against them when applying for funding.

A lot of funding available for specialist support for racially minoritised women requires that the organisation is ‘byand-for’ racially minoritised women, defined in often narrow ways. This can restrict an organisations’ ability to apply, even where there is a high proportion of racially minoritised staff and the organisation already provides those specialist services. Organisations received more funding at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, which meant that they could support more women and expanded their outreach and services. That funding has now dried up, reducing their capacity to support these women despite ongoing need.

The spaces themselves pose management challenges. Many organisations rent their buildings, which can feel precarious. Many don’t have enough space and are forced to be creative, flexible and “make do.” Building maintenance is expensive and challenging – especially where organisations rely on a landlord to carry out repairs.

The Covid-19 pandemic has had an impact on the way that women engage with some organisations. It can be common for women to come only for appointments, rather than simply spending time in the space, which has an impact on its character, use and atmosphere.

Where residential spaces are offered, women’s organisations want to create homely and safe spaces but are cautious of creating dependency. In designing the spaces as “nice but not too nice,” they might try to ensure that women will not resist moving on, and to mitigate women’s disappointment in the inevitably low-quality housing they are offered.

It can be difficult for organisations to recruit staff who are experienced in a holistic casework model. Many organisations prefer to recruit women who have come through the service themselves. While organisations are heavily dependent on volunteers, managing those volunteers is enormously time-consuming and challenging. Resources are strained and careful, trauma-informed work takes time. It takes a lot of time to train staff, whether they are volunteers, fundraisers, consultants or board members. While many are concerned with achieving genuine diversity, on the board of trustees for example, it can take years to meaningfully change organisational cultures.

An overall challenge and critique was that organisations feel forced to provide services through and alongside existing, broken systems rather than challenging those systems. Some women’s organisations have stayed focused on campaigning and advocacy.

Transformative Practice

In elements of the organisational practice of women’s buildings, we can see transformative approaches designed to support women and to change the system. Organisations spoke of creating dedicated wellness spaces to promote women’s healing, shaped by trauma informed principles, eco-conscious and inclusive design, such as sensory rooms.

Lived experience is centralised in operational practice and organisations advocate for this approach across the sector, building knowledge and capacity. Some spoke about their organisation’s formal move towards a co-production model that fully involves women who use the building in decision making, gathering their ideas on everything from interior design to the activities that take place there. Many of the staff themselves have lived experience, which has the potential to transform organisations and the sector more broadly.

Some organisations run and participate in lived experience panels, bringing the voices of women into policy spaces. Others offer training on how to centralise lived experience in practice. This is part of a pattern of transformative capacity-building traceable across the sector, where organisations share their experiences and models with others, advising and consulting on how to set up spaces and how to do meaningful consultations with women, for example. In terms of funding, organisations are imagining new ways of generating sustainability that move away from reliance on grant funding and retain their feminist and trauma informed foundations.

Many organisations have developed holistic casework models, where the woman’s whole self and life is considered. Some have developed integrated, holistic training – both in-house and external. One organisation, for example, worked with a university to develop a holistic casework degree. They aim to formalise and mainstream this approach, and to ensure that holistic caseworkers can

be recruited. Central to this holistic approach is a desire to create self-help tools for women, so that they can go on to live safe and fulfilled lives.

While often working with the criminal justice system, organisations are conscious of the effects of stigma on women, including in relation to employment, and work to reduce it. Preserving independence and the ability to criticise the system was emphasised by one organisation, for example, by refusing to take contracts that would limit their freedom to criticise systems and decisions by those in power.

Women’s organisations are working to transform the system and the sector in various ways, sometimes engaging with the system and sometimes challenging it. This often relies on activating women’s stories and testimonies, by inviting politicians to visit the space and speak to the women, for example, and campaigning and

The creation of this manifesto was funded by the Independent Social Research Foundation Small Grant Award for the project Transformative Justice for Women.