NORTH CAROLINA Farm Life

The Murphy family shaped North Carolina’s pork industry — and they’re not done yet.

Braswell Family Farms: Growing a legacy from mill to egg powerhouse

USDA in N.C.: Ron Garret leads the state’s farm programs

Publisher Neal Robbins

EDITORIAL

Senior Editor Cory Lavalette

Editor Dan Reeves

Contributors Melinda Burris, Ena Sellers, PJ Ward-Brown

PHOTOGRAPHY

PJ Ward-Brown, Stan Gililand

ADVERTISING

Jim Sills, VP of Local Newspapers

SALES REPRESENTATIVES

Allison Batts, Carol Windsor

DESIGN

Design Editor Lauren Rose

North

Asheboro, N.C. 27203

Letter from the publisher

These stories remind us that agriculture in North Carolina is not static — it evolves with each generation.

WELCOME TO THE SECOND EDITION of North Carolina Farm Life, a North State Journal special publication. We’re proud to bring you another collection of stories highlighting the people, innovations and traditions that de ne agriculture and rural life in our state.

North Carolina’s rural landscape and agricultural economy is as diverse as it is essential — from eggs that feed the East Coast and Wagyu beef raised with precision to century-old family farms and the country’s rst hydroponic co ee operation. In this issue, we go beyond the statistics and talking points to introduce you to the individuals whose daily work sustains our food supply and rural communities.

You’ll meet Trey Braswell, now leading the fourth generation of Braswell Family Farms, who re ects on faith, stewardship and decades of growth in Nash County. In Davidson County, Josh Snider opens the barn doors to a dairy operation built on childhood dreams and hard-earned experience. In the rolling hills of Hurdle Mills in Person County, Stanley Hughes shares lessons from a lifetime of farming and his pioneering role in organic tobacco. And we visit Turkey, in Sampson County, where the Wilders family is using science and stewardship to raise high-quality Wagyu cattle. You’ll also nd the remarkable story of Big Guns Co ee — a venture founded by a Marine veteran and his daughter that is reshaping how we think about farming and entrepreneurship.

These stories remind us that agriculture in North Carolina is not static — it evolves with each generation. Yet the core values remain: hard work, family, faith, innovation and a deep connection to the land. Those values are present in every feature of this issue.

I am excited to bring you the second issue of North Carolina Farm Life with excellent stories of the people and practices shaping rural communities and the agriculture industry across our state. Whether you’re a farmer, policymaker, rural resident, consumer or simply someone who appreciates the work that happens in our elds, barns and pastures, we hope you’ll nd something meaningful in these pages. As the hot, humid summer months await us, we are especially mindful of the farmers and families across North Carolina who rise early and work late to tend their elds, ocks and herds. Their daily dedication under the North Carolina sun reminds us why these stories matter — and why we’re proud to tell them.

Murphy Family

Carrying on a North Carolina pork legacy across three generations

Humble roots to industry giants driven by family ties

By Dan Reeves North Carolina Farm Life

DUPLIN COUNTY — When Successful Farming launched its Pork Powerhouses list 30 years ago, Murphy Family Farms ranked No. 1 with 180,000 sows. Founder Wendell Murphy had built a pork empire from the dirt lots of Rose Hill, eventually producing more pigs than entire states like South Dakota, Ohio and Wisconsin.

By 1994, the operation expanded to 337,000 sows and held the top spot for four years. But after the hog market collapsed in 1998-99, the company sold to Smith eld Foods. The deal, nalized in 2000, included 325,000 sows.

The Murphys launched a new endeavor in 2004 — Murphy Family Ventures — and two decades later, they’ve returned to the Pork Powerhouses list. The 2025 ranking, released in May, places them at No. 9 with 150,000 sows following a major agreement with Smith eld announced in December 2024.

Under the deal, Murphy Family Ventures took ownership of 150,000 sows and the market hogs they produce, while Smith eld continues to provide feed and transportation. Murphy now produces about 3.2 million hogs annually for Smith eld.

Despite shedding 170,000 sows, Smith eld/WH Group remains the nation’s largest pork producer with 600,000 sows.

The Genesis: Wendell Murphy’s vision

What began in 1962 as a modest feed mill in rural Duplin County has evolved into a diversi ed enterprise, starting with founder Wendell Murphy and carrying on to his son, Dell, and a third-generation leader, Wen.

“Murphy Farms goes back to 1962,” Wendell Murphy said, re ecting on his origins on a small tobacco farm. Like many

MURPHY FAMILY

in rural areas then, his family diversi ed with livestock for self-consumption. After graduating from NC State in 1960 and rejecting a job o er in Brazil, Wendell brie y taught vocational agriculture, knowing he wanted to be his “own owner and business.”

His entrepreneurial journey began with a feed mill, a daring move considering Duplin County already had a dozen small operations. The initial model involved shelling corn for poultry companies, earning a modest 10 cents a bushel. However, Wendell quickly spotted an

COURTESY

Piglets nurse from their mother sow at Murphy Family Farms in Wallace.

untapped opportunity: the discarded corn cobs and husks.

“It occurred to me that there would be a market for that cobbled shuck material,” he said. “It turned out that we could sell all that we could get. There was a strong demand for it.”

This innovative approach signi cantly boosted their edgling business.

The arrival of combine harvesters in the early 1960s, leaving cobs in the eld, signaled a shift. With extra time at the feed mill, the Murphys ventured into buying feeder pigs from local sales, nishing them on dirt lots.

“It was clear right from the beginning that we were making a lot more money on the hogs that we were producing ourselves than we were on the feed that we were selling,” Wendell said.

This realization led them to pivot, eventually ceasing the custom feed business to focus entirely on hogs. Their expansion became aggressive, sourcing pigs from across the Southeast, eventually even as far as Iowa, Missouri and Minnesota.

A devastating blow came with a hog cholera outbreak in 1969, which required the government to destroy their entire herd of 3,000 to 4,000 pigs, burying them on the farm. With their land quarantined, Wendell, drawing an idea from the poultry industry, turned to contract farming. They provided growers with all necessary equipment and capital investment. Farmers, risking only their time, were paid a dollar per pig.

“A thousand dollars today won’t buy much, but back then it was signi cant,” Wendell said. “

This model “exploded,” quickly creating a line of farmers eager to partner.

As their demand for pigs outstripped supply, the Murphys recognized the need for their own sow operations, bringing in experts to manage this complex new venture. Wendell’s philosophy: “You make sure you’re hiring people who are smarter than I am. I want somebody smarter than me, not less smart.” This principle has been a cornerstone of their success.

Navigating crashes and political service

The business continued its upward trajectory until a severe market crash in 1998, which deepened further in 1999.

“Those two years made me realize that the biggest mistake that I had made ... was by not building a processing plant,” Wendell re ected.

Permits that were once available became impossible to secure, leaving them vulnerable to market uctuations.

During this period of intense growth,

Wendell also served in the North Carolina General Assembly — six years in the House (1983–1988) and four in the Senate (1989–1992). He credits his strong management team for enabling this civic duty. He recounted winning every precinct in his district, a testament to the Murphy family’s reputation for “honesty and integrity.”

“You don’t promise a lot and deliver a little,” he said. “You promise a little and deliver a lot.”

The birth of Murphy Family Ventures: Dell’s leadership

While Wendell never envisioned the immense scale his enterprise would eventually reach, the foundation he laid proved to be remarkably strong. A new chapter began around 2001, after the family’s core hog operations were sold to Smith eld. That’s when Dell Murphy stepped in to build a “back o ce” and manage the family’s diversi ed interests under the new umbrella of Murphy Family Ventures.

The establishment of Murphy Family Ventures included building strong human resources and accounting departments to support the family’s growing business portfolio. This included managing contracts for family members who became Smith eld growers and taking over operations of the DuPont land development, River Landing. Today, the portfolio includes 1-800-PACKRAT, Albemarle Boats, Bill Carone Ford GMC Buick Chevrolet, River Landing, the Mad Boar, Village Subs and more, totaling more than 60 business entities and over 1,000 employees.

“I learned everything I know from this guy and his dad,” Dell said, gesturing to Wendell, his voice thick with emotion. “I’ll re-echo — and I apologize if I get emotional, I’m just one of those people. If I feel it, I wear it. That’s really the biggest

blessing of my life, no question. I try to do exactly what he said: get people who are smarter than me, dedicated, and ready to get up and be the best.

“We’ve stubbed our toe and gotten smarter a few times.”

Murphy Family Ventures has continued to diversify.

“I almost don’t know which way to turn when I wake up in the morning,” Dell joked, highlighting their varied holdings, which include a boat company. However, his “love is with the pigs,” a passion that has been reignited by a recent, signi cant transaction.

Reclaiming the legacy: the return to hogs

Last year, Murphy Family Ventures reacquired a signi cant portion of the hog operations that were previously part of Smith eld’s U.S. assets (which have since become publicly traded).

“It was a very friendly transaction,” Dell said. While the scope is limited to their North Carolina operations — about half of what Wendell originally sold — it marks a powerful return to their roots. “It’s a nice-sized operation. And it’s plenty for us.”

Stephanie Durner, who has been with the company for decades, noted the profound sentiment surrounding this reacquisition.

“I’ve seen so much nostalgia, so much sentiment around this most recent deal,” she said.

The return has involved resurrecting retro branding, including a 1990s-era logo. Recent grower events have seen individuals who worked with Murphy Farms 25 to 30 years ago “come back to the fold,” a testament to the enduring relationships built on trust and integrity. Furthermore, about 35 to 40 former Smith eld employees, primarily from local communities, transitioned to Murphy

COURTESY MURPHY FAMILY

Wen Murphy, grandson of Wendell and son of Dell, is seen holding piglets at Murphy Family Farms.

Family Ventures and have “really buckled down and they’re on the program,” according to Dell.

Economic

impact and community roots

The Murphy family’s impact on Duplin County and eastern North Carolina is undeniable.

“It’s obviously huge,” Dell said, crediting his father for laying the groundwork. State Sen. Jimmy Dixon once said the Murphy family was responsible for a “very high percentage of the tax value in Duplin County.” Beyond the sheer economic contribution, the family’s contract farming model allowed local farmers to diversify their operations with a “nice solid income,” providing stability in an often unpredictable agricultural landscape.

The third generation: a foundation of dedication

The dedicated third-generation leadership falls on 30-year-old Wen

Murphy, who oversees support operations in North Carolina, including maintenance, heavy equipment and nutrient management. Wen brings a wealth of hands-on experience.

“I’ve worked one summer since I started working back in high school outside of the company,” Wen said.

He’s earned his stripes and worn many hats through the years, working as a prep chef, interim manager, herd tech on hog farms ( nishers and sows), and even installing and training sta for chicken farms. He managed a breeding department in Missouri, became an assistant manager, then a farm manager, before transitioning to project manager in maintenance.

“I’ve kind of taken two or three positions and ... we didn’t hire back everybody all at one time,” he said. “I just kind of assumed those roles for a little while.”

Having attended NC State like his father and grandfather, he decided early on to dedicate himself to the company.

“Whatever part of that didn’t really matter to me, I was gonna be part of it,” he said. “It’s been a lot of fun. There’s always

Waters Agricultural Laboratories, Inc.

a challenge. And I think that’s the driver, right? What can we do to overcome this? Did we do this good? Could we have done it better? Always trying to get a little better overall.”

Keeping family ties strong

Wendell Murphy took every opportunity to reiterate that the success and survival of both the family and the business depended on staying together. He felt that bond was strained after the Smith eld merger, when daily work and collaboration changed. To strengthen those ties, he started the Murphy family retreat, an annual event now in its 20th year. What began as a way to manage a new investment portfolio has become a cherished tradition that brings the extended family together.

Cousins of the next generation, including Wen, have grown “very, very close now” through these gatherings.

“Sometimes you have to get creative to make sure that we keep the glue,” Wendell said, “because we’re always stronger together.”

IMPROVING GROWTH WITH SCIENCE

Wilders blends tradition, science

Wilders is building a legacy that not only produces high-quality beef and pork but also strengthens agricultural practices

By Ena Sellers North Carolina Farm Life

NESTLED JUST a stone’s throw from Interstate 40 in Turkey, in Sampson County, the Wilders’ farm is perfectly positioned only a quarter mile from Exit 364, making it an easy stop for visitors.

Trees frame the edges of the Wilders’ property, standing as silent sentinels to the Wagyu cows grazing peacefully in the distance, their serene presence underscoring the tranquility of this rural

haven. Jaclyn Smith, her husband Reid and their three children have created a home here, where nature’s beauty and the steady rhythm of the land serve as daily reminders of life’s simple blessings. Surrounded by wide open spaces and

a deep connection to the earth, the family has created not just a home but a sanctuary that re ects their values and passions.

Sprawling across 1,300 acres, the Wilders farm is home to a thriving herd

PHOTOS BY ENA SELLERS / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

of 2,000 cattle and more than 100 pigs, each an integral part of their ecosystem. For this family, their journey into raising Wagyu cattle and Berkshire hogs was driven by a deep love for agriculture and a commitment to growth that is as purposeful as it is personal.

“(The pandemic) gave us the opportunity to really evaluate what was important, what we could live with and what we could live without,” Jaclyn Smith told North Carolina Farm Life. This re ection led them to embrace a new venture in agriculture. “Through that whole process, we learned that agriculture was something that our family was passionate about.”

What started as a small vegetable garden and some chickens in the Wilders township of Johnston County quickly expanded — and the brand Wilders was born.

“Eventually, we added four pigs — one boar and three sows — then a momma cow. We didn’t know she was pregnant with twins, and so we immediately had a bottle baby, which was so much fun for us to experience,” Smith recounted, her excitement evident as she reminisced.

For the couple, the decision to raise Wagyu cattle was driven by the breed’s uniqueness and the exceptional quality of the beef it produces. The marbling in Wagyu is what gives the meat its renowned melt-in-your-mouth buttery texture.

“It was a very intentional decision,” Smith said, adding that they were very fortunate early on because a few farmers were leaving the industry just as they were getting started.

“We were able to acquire mature cows, so we could really start dabbling with some of the genetics,” she said, explaining that this also provided the opportunity to engage with experienced breeders who generously shared their knowledge.

The Wilders brand grew signi cantly over the course of a year. In December 2021, they acquired the property in Turkey.

“We moved our rst animals here on Christmas Eve of 2021,” Smith said. By the summer of 2022, the couple and their three children, now aged 8, 12 and 14, had fully relocated. “We spent Christmas break in an RV out here, and then we kind of went all in. Our kids started the new school year o here, and so our family o cially moved out this way over the summer of 2022.”

The entire family is involved in farm activities, with each member taking on di erent roles. The children help with everyday tasks like mowing and feeding

A PROUD local lending partner OF THE FARMERS AND RURAL RESIDENTS WITHIN NORTH CAROLINA.

Providing loans for farms, homes and land within 46 counties in eastern and southeastern North Carolina.

COURTESY WILDERS FARM

the animals. The farm has a diverse team, some with agricultural backgrounds and others without. However, everyone contributes their strengths from various professional elds. According to Smith, this mix has introduced new perspectives and innovative ideas to their farming practices.

With a background in elementary education and real estate sales, Smith plays a crucial role in educating consumers about their products and their commitment to producing high-quality meats.

“We want to do it the right way, and we want to be good stewards of God’s creation,” she said.

Reid Smith grew up raising cattle with his father before transitioning to a career in development and construction. Today, he leads the genetic side of the business.

“He has really enjoyed the science behind merging the di erent bloodlines to be able to create an elite animal that produces a great beef,” Smith said.

Using advanced breeding techniques, such as arti cial insemination and embryo transfer, Wilders breeds full-blood Wagyu cattle with lines tracing back to the Japanese lineage.

“We have a satellite lab where Vytelle, a worldwide company, works extracting what they call ovocytes, which are like unfertilized eggs from the mom, and then they can fertilize the eggs and create an embryo,” Smith explained. This technology helps Wilders improve the genetic pool of their herd and improve reproductive success. “They can grade the embryos to make sure that they have the best viability. It’s really neat that we can do that, all on our property.”

Smith noted that various factors contribute to the overall evaluation of an animal, including both physical traits and the genetic potential of their cattle.

“You want a well-balanced animal,” she said. “The embryos get created, and then they get implanted in surrogate moms. They can be other Wagyu moms or they can be non-Wagyu moms. We have a few herds on the farm that are non Wagyu.”

Smith noted that these larger-framed surrogate mothers can help reduce birth complications because they are giving birth to smaller animals. Additionally, they produce high-quality milk, which gives the calves a strong start in life. She mentioned that they typically expect about one-third of the implanted embryos to successfully take. Also, bulls are allowed to naturally service the remaining cows during their cycles. She explained that they try to synchronize the cows’ cycles so that births occur during the most favorable weather conditions for

“We want to do it the right way, and we want to be good stewards of God’s creation.”

Jaclyn Wilders

both the mother and calf. They usually focus on a two-to-three-week window for births in a speci c pasture.

“We really try hard to schedule the births in the spring and fall because the weather is best for both mama and baby for survival and for birthing. Lots of things I never thought I would know in my life, but we’ve learned through this process and it’s been so cool,” Smith said.

To ensure optimal health, the Smiths work with a nutritionist who advises them at each stage of the animals’ development. Additionally, each pasture is equipped with salt blocks and mineral trays to provide balanced nutrients. The grain nishing process also plays a crucial role in enhancing the marbling of the meat, adding to its palatability.

Wagyus are harvested once they reach 28 to 30 months of age. The extended feed time for Wagyu cattle contributes to the additional costs, but it is necessary for achieving the premium marbling that de nes their beef.

Like Wagyu cows, Berkshire hogs are also known for their meat marbling.

“You can see some marbling in the pork side, too — it is quite delicious,” Smith asserted. Their pigs are raised outdoors, allowing them to forage and contributing to the avorful pork.

“We just felt like they needed to be on the ground and in nature, and when they do that they’re getting to forage a little bit, and so they’re getting nutrition from the ground,” she added, explaining that although this approach can be more costly, the family values it as part of their commitment to animals well-being.

That includes the Smiths’ decision to keep the sows with their o spring after birth, which they believe is crucial for the animals’ welfare at that early stage.

“One thing that I have enjoyed also about the process was letting the mom and baby stick together,” she said.

Her passion for the family farm shines through as she re ects on how they’ve built something truly meaningful.

“I like that we’ve been able to create what we feel is important on our farm,” Smith said.

The Wilders journey has evolved, with

ENA SELLERS / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

the family recently beginning to reap the rewards of their hard work. Some of the embryos they created back in 2021 are now reaching maturity and contributing to the products in their freezer — it takes about three years to turn an embryo into a nished steak, a reminder of the long-term dedication involved in raising premium livestock.

“We want to knock the socks o our customers every time And so to do that, you have to have a consistent quality product,” Smith said.

“The goal is to get on as many menus as we can. And then also continue to advance on the genetic side so that we are creating that top quality product every time.

“We’re very focused in the U.S., just with our beef side. But I think on the genetic side … it can expand past just the U.S. … I think the sky’s the limit.”

Wilders hopes to contribute to the agricultural community by o ering live animals and genetics for sale. Smith shared that they are planning to have a production sale o ering live animals directly from their farm, alongside frozen genetics in November.

ENA SELLERS / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

Hoke cotton elds re ect global economic trends

Local farmers adapt to market changes and technological advancements

By PJ Ward-Brown North Carolina Farm Life

RAEFORD — As autumn’s crisp air replaces summer’s heat, the elds of Hoke County undergo their seasonal transition. The county’s cotton elds transform as white bolls are harvested and rolled into large bales, awaiting transport to local gins. Throughout North Carolina, cotton farming stands as a

symbol of both tradition and change.

Historically known for its livestock, Hoke’s farmers have diversi ed their agricultural portfolio to include corn, peanuts, soybeans, sweet potatoes and cotton. This shift re ects a broader trend in North Carolina’s farming sector, where adaptation and diversi cation are key to sustainability.

Farmers like Marvin McDonald, his son Daniel and veteran Johnny Boyles are at the forefront of this evolving landscape. They navigate the complexities of a crop deeply intertwined with the global economy. Marvin McDonald, who transitioned to cotton farming in 1989,

was driven by the need for nancial sustainability amid uctuating grain markets. “Cotton farming is not just about growing a crop; it’s about understanding and adapting to market trends,” he said.

Daniel McDonald, set to continue the family legacy, stresses the importance of public awareness and appreciation for the impact that farmers and agriculture have on every citizen.

“Many don’t realize where their food comes from,” the younger McDonald said. “They see farming, but they don’t understand the challenges and hard work involved.”

He says a commitment to educating

PJ WARD-BROWN / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

the public and encouraging the next generation’s involvement in farming is vital for the industry’s future.

Johnny Boyles, with four decades in farming, joined the McDonalds to discuss cotton crops. Boyles re ected on the shift from tobacco to cotton as his entry into the cotton industry.

“Tobacco was once the mainstay, but cotton has proven more sustainable and less controversial,” said Boyles. “It’s about adapting to the times and the market.”

Boyles also pointed to technological advancements that have transformed cotton farming.

“The industry has evolved, but the essence of farming — resilience and hard work — remains unchanged,” he added.

The global cotton industry is signi cant to the world economy, with major producers like the United States, India, China and Brazil shaping the market. The U.S. remains a key exporter, with states like Texas, Georgia and Mississippi leading in production. The international supply chain of cotton, stretching from cultivation to textile manufacturing, involves countries like China and Bangladesh, requiring stable trade relations to maintain practices and production.

In North Carolina, the major players in cotton production are concentrated in the northeast of the state. Counties like Halifax (95,000 bales), Northampton (71,400), Bertie (70,000), Martin

“Cotton farming is not just about growing a crop; it’s about understanding and adapting to market trends.”

Marvin McDonald

(56,000), Edgecombe (47,500) and Hertford (34,000) lead in production.

While Hoke County doesn’t rank among these top producers, its agricultural diversity, including row crops and livestock, provides a bu er against market volatility, strengthening the local economy and contributing to the resilience of the state’s agricultural sector.

These farmers face challenges, including uctuating market prices, weather and evolving consumer demands as part of the broader industry. The value of global and state cotton economies underscores the crop’s signi cance. The U.S. is a leading cotton producer, with an estimated annual production value

exceeding $6 billion. North Carolina, ranks sixth among states in cotton production.

The latest U.S. Department of Agriculture cotton projections for 2025 show China accounts for nearly half of global cotton stocks, with India, Brazil and the United States combining for an additional 25%. World cotton production is forecast at 117.8 million bales, about 3% below the previous year, as global output declines in India, Pakistan and the U.S. o set gains in China and Brazil.

Global cotton trade is projected to rise in 2025-26, reaching nearly 44.8 million bales — the highest level in ve years — driven by increased mill use and

ELI WARD-BROWN FOR NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

Marvin McDonald, left, and his son, Daniel, stand next to rolls of Cotton harvested on their farm.

Despite production slipping from last year’s levels, ending global cotton stocks are projected to hold steady at around 78.4 million bales, maintaining a historically

and

These updated forecasts underscore a shifting global balance, where strong consumption and trade growth contrast with slightly weakening

— especially in historically

producers like India, now forecasted to produce 23.5 million bales, its lowest in 17 years.

Local North Carolina farmers like the McDonald family are committed to the future of global crops like cotton and hope the demand and innovation help keep them in business.

“I just hope that textiles and things can improve around this area so we can continue to a ord to do it,” Daniel McDonald said.

CAROLINA AGRI-POWER LLC

PJ WARD-BROWN / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

North Carolina ranks sixth among states in cotton production.

A Culture of Barbecue. A Commitment to Community.

Across North Carolina, barbecue is more than a tradition. It’s a point of pride.

That’s why the NC Pork Council proudly sponsors the Whole Hog Barbecue Series a celebration of our state’s rich barbecue heritage that also supports the communities we call home.

In the past five years, these events have raised more than $1.1 million to support local nonprofits and strengthen North Carolina communities.

Pine Knot Farms

Third-generation small farmer

Stanley Hughes discusses challenges

By Melinda Burris North Carolina Farm Life

HURDLE MILLS — Stanley Hughes is 77 years old, and — alongside his wife, Linda Leach Hughes — he still works sunup to sundown daily, farming land in Hurdle Mills, a small community just outside Hillsborough that has been in his family since his grandfather purchased it in 1912.

Despite years of working full-time jobs, Hughes always continued farming part time. Because of his persistence, he is proud to say that, while at times some elds have been dormant, Pine Knot Farms has been farmed consistently.

“I sort of try to choose what the market calls for,” Hughes said.

Though Hughes certainly knows his trade and is sure to plant produce that years of experience have taught him will sell well, he is willing to experiment.

He says he tried “to diversify some,” keeping a watchful eye on the market to see what new vegetation he can plant that will nd a consumer base.

In addition to organic tobacco, Pine Knot Farms cultivates a variety of fresh fruits and vegetables. The Hugheses have gained a reputation for their quality collard greens, sweet potatoes, Brussels sprouts and broccoli, along with an assortment of other produce.

Hughes began growing organic tobacco 29 years ago after being approached by R.J. Reynolds, which was looking for farmers willing to grow the crop using organic farming practices. Looking back, he recalls that he and one other man he knew were the rst two African American farmers who decided to take a chance on the new methods and “get in on it.”

He knew what was happening in the industry and was aware that, at the time, organic tobacco was “bringing in twice as much (pro t) as normal tobacco.”

“I said, ‘Well, I’m going to try some of it,’” he said. “I didn’t try to put my whole crop in it because I didn’t know which way it might go. So far, it’s been OK.”

Hughes said while he’s learned organic

farming produces healthier crops, it can also a ect how much is harvested because organic farming does not allow using pesticides and other chemical agents.

“Some of this stu , where you can do di erent things and apply di erent chemicals and stu , will make the yields go higher,” he said. “Some of your organic crops aren’t going to yield as high because of what the chemicals do.”

Overall, the Pine Knot Farms entrepreneur said taking the initial risk of trying organic tobacco farming nearly three decades ago has been a positive that has led to him getting more business contracts from those who speci cally want to buy organic. This is a market he sells to, understanding that there

PHOTOS COURTESY PINE KNOTT FARMS

Stanley Hughes is seen walking in the collard greens elds of Pine Knot Farms.

are certain patrons who will come to his farm because his tobacco is organic.

“They’ll come to you; some buyers will come to you quickly,” he said.

According to Hughes, a signi cant hurdle small farms like Pine Knot face is simply trying to get a share of the market.

“You can’t compete with the large farmers because a lot of this stu , they got di erent packing equipment.”

That leaves small farmers struggling to keep up and maintain a large enough outlet for selling their goods to keep their investment pro table.

Part of the di culty, Hughes explained, is nding a way to get the funding they need to try new farming machinery and methods.

“If you want to make change, a piece of equipment that you think you can sell, say it was a crop you want to plant or harvest, maybe a piece of equipment you need to buy to do that and trying to get a loan to do it, being small, they aren’t going to say it’s feasible for you,” he said.

Having been through this process multiple times, Hughes is often asked, “Do you want to take on that kind of debt, over time?” Hughes attributes this to nancial organizations being afraid small farmers will over-extend themselves.

That can leaves some small farmers with no choice but to continue to use traditional and often outdated techniques and second-hand equipment instead of bene ting from the most current technology.

Hughes is a strong proponent of the region’s Black Farmers Markets, asserting that their events provide an excellent opportunity to create connections that help sustain small farmers.

Left, Stanley Hughes and wife Linda Leach Hughes are photographed after receiving the NC Rural Center’s 2022 Entrepreneurs of the Year Award. Right, the Pine Knot Farms stall is pictured at a local Black farmers market. PHOTOS

Ron Garret appointed USDA state executive director

Advancing Trump’s America First agenda for NC Agriculture

By Dan Reeves North Carolina Farm Life

RON GARRET, recently appointed as state executive director of the USDA Farm Service Agency in North Carolina, brings decades of experience working closely with farmers across the state. Having served as a county executive director, Garret’s strong relationships with growers prepared him well for his current role overseeing federal farm programs statewide.

Garret’s long career with the Farm Service Agency (FSA) began in 1991 as a county operations trainee. Over the years, he served in multiple county o ces before spending nearly 34 years as a county executive director, earning numerous awards from the National Association of State and County O ce Employees for his dedication to agriculture and community service. He holds a bachelor’s degree in agricultural business management from NC State University.

As state executive director (SDA), Garret oversees the delivery of FSA programs to agricultural producers across North Carolina. These programs include commodity support, conservation initiatives, credit assistance and disaster relief, all aimed at ensuring a safe, a ordable, abundant and nutritious supply of food, ber and fuel for Americans.

“My experience as a county executive director blessed me with the opportunity to serve the growers of our state,” Garret said. “My relationship with the growers helped shape me and gave me the experience to be prepared for this role — to serve not only my area but all of North Carolina.”

As SED, Garret’s responsibility is to carry out the vision of the president and implement agriculture programs passed by Congress, ensuring they reach farmers e ectively and fairly.

“My role is to be a leader for the president and his focus on the rural community,” Garret said. “The programs Congress implements we carry out to make sure they are implemented correctly

Ron Garret was appointed by the Trump

executive director of the USDA Farm Service

and appropriately for the growers of North Carolina.”

Since stepping into the position in May, Garret has prioritized addressing pressing challenges faced by farmers, particularly those in western North Carolina a ected by Hurricane Helene.

“We’ve focused signi cant energy on providing support to growers in the mountains,” he said. “Since I came on board, we have worked hard to assist that region.”

Garret also emphasized ongoing economic challenges confronting North Carolina’s agriculture sector.

“Our growers are concerned about the overall farm economy, especially commodity prices,” he said. “There are challenges in the local economy and the farm economy in general.”

The current administration’s “America First” agenda is an integral part of Garret’s role.

“The president is certainly focused on the farmer,” he said. “He’s keenly aware of their needs and committed to supporting them.”

Garret’s leadership is critical for

“My role is to be a leader for the president and his focus on the rural community.”

Ron Garret

guiding North Carolina’s farming communities through economic and environmental challenges. With extensive experience and close ties to growers, Garret is dedicated to ensuring federal resources help sustain and grow the state’s vital agricultural sector.

“I’m here to carry out the president’s vision and support the rural economy through e ective program delivery.”

COURTESY N.C. FARM SERVICE AGENCY

administration to serve as state

Agency in North Carolina.

SPRING INTO SWEETNESS

stews + soups

casserole

puree + mash

SWEETPOTATO MANGO POPSICLE

Created in partnership by Bucket List Tummy’s Sarah Schlichter, RD of record for the NC Sweetpotato Commission.

PREP TIME: 10 minutes

FREEZE TIME: 6 hours

SERVINGS: 8

CALORIES: 16 kcal

INGREDIENTS

• ¼ c sweetpotatoes cooked, cooled and mashed

• ½ c mangos diced

• ½ c pears diced

• 1 Tbsp strawberries diced

• 1 c mango seltzer or light wine

INSTRUCTIONS

income rural urban shopping list bag of potatoes

1. Combine all ingredients in a blender, except diced strawberries.

2. Blend until icy consistency.

3. Pour into popsicle molds. If desired, you can add reserved diced fruit (including strawberries) in the molds.

4. Freeze 2-3 hours or overnight until solid.

5. Serve as is, or in a glass of your favorite juice/seltzer or wine (rosé or sauvignon blanc work best)!

Brewing up a farming revolution — indoors Big Guns Co ee

The scalable, sustainable franchise bene ts veterans and the disabled

By Dan Reeves North Carolina Farm Life

TRYON — At rst glance, Big Guns Co ee seems like any other neighborhood cafe — a locally owned, welcoming spot to grab a cup of joe or a mu n. It could easily pass as an alternative to

Starbucks in the picturesque Blue Ridge Mountain town of Tryon, an a uent, artsy community known for attracting the outdoorsy and equestrian set. Big Guns ts the charming aesthetic — from the outside, at least.

In reality, it’s the front line of a new farming model that could reshape how co ee is grown and consumed in the United States. The “shop” is where most of the roasting is done, but in a large open space in a modern building 15 minutes from Tryon proper, Shane “T. Shane”

Johnson and his 10-year-old daughter, Charli, shared with North Carolina Farm Life the Big Guns story, how the co ee is grown and their plans for the future.

Standing before rows of co ee plants growing above tanks of water under the glow of LED lights, Johnson said, “Just Google ‘hydroponic co ee farm.’ Pretty much all you see is us.”

Big Guns Co ee is the nation’s only hydroponic co ee farm — for now. Johnson hopes to franchise the concept, giving others, especially veterans, a shot

PJ WARD-BROWN / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

Charli and her father, T. Shane Johnson stand in front of co ee plants growing hydroponically at Big Guns Co ee’s facility outside of Tryon.

“Why don’t we start a co ee brand?”

Charli Johnson

at a rare business model. Co ee typically grows in tropical regions like Colombia and West Africa, with Hawaii the only U.S. producer.

“We needed to scale really fast because we got so many requests for the co ee,” Johnson said. “We had so many people come to us saying, ‘I want to grow a farm!’”

The approach has drawn international attention, including inquiries from Germany.

“No one’s really done this on scale

before,” he said. “We cracked the code.

“Most of the co ee on shelves comes from the same farms, just di erent packaging,” Johnson said. “We want people to actually know where their co ee is grown and how — and give farmers a more secure future.”

The team recently ful lled a major retail order — 13,000 bags of co ee for Sprouts stores across the U.S. — and is now setting its sights higher. Big Guns has been invited to audition for Shark Tank, with plans to pitch the concept nationally.

A scalable co ee farm franchise

Johnson, who lost most use of his right arm during his time in the Marine Corps in a brutal attack, wanted more than just to grow and sell co ee. He’s focused instead on franchising — o ering wounded veterans and farm-based entrepreneurs a chance to create their own versions, potentially with on-site cafes and agritourism draws.

To meet growing demand and scale quickly, Big Guns is launching a franchise

PHOTOS BY PJ WARD-BROWN / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

program aimed at farmers who want to add a new cash crop to their operations. With an initial investment of around $50,000, franchisees can set up mobile hydroponic farms capable of year-round co ee production. The company handles harvesting, packaging and distribution, while farmers share in the pro ts.

“It’s a co-op model,” Johnson said. “They grow it, we harvest it and sell it through retail — like Sprouts, Walmart or local grocery chains. That way, farmers don’t have to worry about extreme weather or inconsistent pricing wiping out their income.”

One acre of hydroponics is equivalent in yield to 12 acres of traditional farmland. That year-round e ciency, plus the durability of the enclosed system, o ers an added layer of protection against hurricanes, droughts or supply chain disruptions.

Responding to further questioning, Johnson pointed proudly to his petite daughter and said with a smile, “Talk to her.”

A 10-year-old co ee mogul taking on giants

At 10 years old, most kids are focused on school, playdates and video games. Charli Johnson, however, is busy building a co ee empire and negotiating deals with retail giants.

How Big Guns Co ee came to be isn’t your typical lemonade stand tale. The hydroponic growing system was her father’s vision, but the brand itself was Charli’s idea. Her inspiration came after a traumatic moment — when her dad, Shane, was hit by a car of gang members and left for dead on the side of the highway. He survived despite being declared 100% disabled and “coming back to life” three times.

A nod to her dad’s incredible strength and the world record he once set for most pushups in 12 hours.

“I’ve been watching him do this all the time,” Charli says, her voice carrying a wisdom beyond her years. “He broke several world records while trying to gure out why he’s here. So, I thought, my dad’s strong and I want people to feel that strength too.”

The idea came when Charli was just 6. After school one day, she pitched it to her dad in the car: “Why don’t we start a co ee brand?” Tired of his daily Starbucks runs, he handed her a glitter pen and some paper when they got home. She came back with a name — Big Guns Co ee — and a logo: a co ee cup with little muscles.

PHOTOS BY PJ WARD-BROWN / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

PHOTOS BY PJ WARD-BROWN / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

From there, things moved quickly. A surprise trailer appeared one day, and soon they were setting up shop at a local boxing place. What started as a small venture rapidly gained momentum. Charli found herself being interviewed for the rst time — a nervous but pivotal experience that led to appearances on Fox, “The Kelly Clarkson Show” and other national media.

“I was very nervous,” she recalled, a feeling she now manages with practiced ease.

Charli is no stranger to the media spotlight, but even seasoned entrepreneurs would balk at her next challenge: closing a deal with Walmart. At only 10 years old, she entered a boardroom with the executive of Walmart and his assistant. “I was nervous,” she admitted, describing herself “popping my ngers” at the round table. Initially, her dad started talking, but soon the attention shifted to the unexpected young face at the table.

“They’re like, ‘What’s going on here?

Why is there a kid? Who are you?’” Charli recounted.

With only 20 minutes to secure the deal — and no follow-up opportunities with a company as large as Walmart — the pressure was immense. But Charli delivered her pitch with conviction.

As she shook the executive’s hand, he remarked, “I don’t think I’ve ever been closed by a 10-year-old before.”

The audacious meeting paid o , and Big Guns Co ee secured a deal with Walmart.

Their success hasn’t stopped there. Big Guns Co ee is now expanding into Target and Sprouts and working with platforms like Sincorá. Charli’s business travels have taken her to Las Vegas, Chicago and Reno, with interest even stretching to Germany and Spain for speaking engagements.

Charli is not just an entrepreneur; she’s a trailblazer, a ghter, and a living testament to the power of big ideas and unwavering determination. Her journey with Big Guns Co ee is far from over,

and it’s clear she’s just getting started.

The long-term vision goes beyond production. Big Guns is building out an agritourism-based co ee experience, where customers can walk into a shop, see the co ee plants growing, learn how beans are processed and even pick their own cherries.

“You’d have to go to South America to get this experience,” the elder Johnson said. “Here, people can see the trees, understand the process and have a great cup of co ee — all in one place.”

They envision franchise opportunities that include not just farms but full retail experiences: indoor farms, cafes and drive-thrus where guests can learn, sip and support sustainable agriculture.

“It’s not something new. It’s the future of farming,” he said.

With interest building both at home and abroad, Big Guns Co ee is betting that the future of farming — and your morning cup — may just be grown under LED lights in a converted greenhouse near you.

Freight Farm

Box to Bowl – community-supported agriculture in action

Smart farm technology helps feed a growing population

By Melinda Burris North Carolina Farm Life

KENANSVILLE — James Sprunt Community College is home to a hydroponic smart farm housed in a renovated 40-foot shipping container.

Katlyn Foy, a specialist in plant science and horticulture, manages the “Box to Bowl” initiative, which she explains is unique because it works for hydroponics and “entwines vertical gardening.” It also stands out as the only facility of its type in the state dedicated to educational research and development of controlled environment agriculture.

Foy emphasized the sustainability of vertical gardening, pointing out it allows for growing “more crops in a speci c area without having to use a whole lot more nutrients or things like that.”

She said the school’s container farm is capable of growing at a full capacity of 2.2 acres and is eco-friendly.

“We use 99% less water than traditional farming, and that is simply just because the water in the farm is recycled on a 24-hour basis.”

All environmental factors within the indoor farm are continuously monitored and controlled by smart technology, creating optimal growing conditions year-round.

To create this consistent, non uctuating atmosphere, the container farm at JSCC relies on an

HVAC system with high-tech heating, cooling and air quality-monitoring capabilities that maintains a constant temperature of 75 degrees within the unit at all times. Additional automation allows Foy and her team to precisely

PHOTOS COURTESY FREIGHT FARMS

Plant science specialist Katlyn Foy, center, runs the hydroponic farm at James Sprunt Community College.

control the amount of water, nutrients and exposure to light the plants receive.

The initiative also utilizes sensor tracking technology that keeps them informed of all electrical conductivity. Foy said it provides data detailing the amount of nutrients that are in the water at any given time.

“Through that,” she explained, “the nutrient system can dose the water based on what those readings are.”

The consistency within the farm creates an environment that Foy credits with giving the plants just one job: to grow. And they do so at a rapid rate, with the average turnaround from seed to harvest generally taking four to six weeks, depending the crop being grown.

Foy is quick to point out another positive to vertical hydroponics.

“We’re able to grow organically because we do not need to use pesticides or chemicals inside the farm,” she said.

Foy said not having to worry about uncertain weather changes and the e ects atmospheric deviations can have on crops “takes a lot o of the farmer.”

“My main role is really just seeding the plants, moving the plants — or better known as transplanting — and then harvesting the plants,” she said.

The sensor tracking technology gives her reassurance traditional farmers don’t have, knowing she will receive an alert 24/7 if conditions alter and pose a danger to the success of her crops.

Sustainable farming and feeding an expanding population

Foy said there is increased interest and support for sustainable farming practices.

“I think in recent years, there’s been a big push for more sustainable agriculture practices because — it’s really sad to say, but a lot of our farmland is going away,” she said. “It’s being purchased by developers to put houses on it.”

Meanwhile, Foy stated, farmers still “have to feed the population. I mean, the people have to have food to eat. And I think the challenge comes from land; obviously, we’re not making any more

PHOTOS COURTESY FREIGHT FARM

land, so we have to utilize what we already have.”

She is quick to stress that sustainable agriculture practices like container farms are “not intended to replace traditional agriculture.”

“It’s another resource under our belt,” she added.

Community-based outreach to combat food insecurity

Grant funding from the Tobacco Trust Fund, Duplin County, the North Carolina Electric Cooperative and Four County Electric Cooperative made the purchase of the container farm and the establishment of the Box to Bowl program at JSCC possible. For Foy, taking the job as manager of the nonpro t educational project was more than a career move; it was a chance for the Duplin County native to return home and pursue her goal of addressing the food insecurity in the area and give back to the community. She maintains the position aligns with her interests on multiple levels.

“I get to teach,” she said. “I get to be kind of in the eld, so to speak. I get to work with my hands, which is everything I wanted in a job.”

Through a contract with the USDA Farm Share Program, Foy and her team have pursued community outreach by collaborating with Duplin County farmers to create 150 community- supported agriculture boxes weekly, distributing 600 boxes of food to those in need each month.

Embracing the future

Foy said she anticipates container farming will continue to grow and evolve in Duplin County, statewide and beyond.

“I always say, the future of sustainable agriculture and controlled environment agriculture is very bright. ... I think with agriculture, there’s always a learning opportunity,” she said. “

There is something new you can learn every single day. ... When you know better, you do better.”

“We’re able to grow organically because we do not need to use pesticides or chemicals inside the farm.”

Katlyn Foy

PHOTOS COURTESY FREIGHT FARM

Snider’s Dairy Farm

Where every animal is treated like a pet

An educational hub and working dairy in Davidson County

By Dan Reeves North Carolina Farm Life

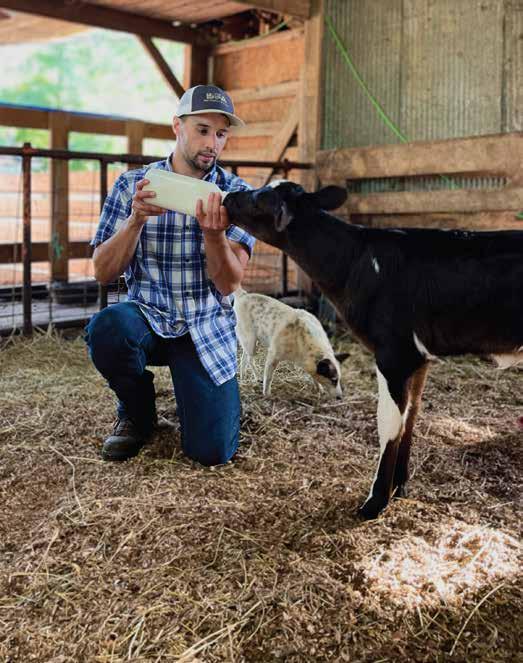

DAVIDSON COUNTY — O the beaten path, tucked away in the pastoral heart of the Piedmont, Snider’s Dairy Farm is rewriting the story of traditional dairy farming — one cow, one calf, one

educational farm visit at a time. A family legacy coupled with young boy’s innate passion for cows and profound respect for animals turned a small local dairy into a thriving, community-oriented functioning farm.

The story begins in the 1970s, when Mark Snider and his father, Clyatt, began building a dairy barn. Mark had discovered a love for dairy work helping a local farmer milk Brown Swiss cows in exchange for a calf. He later worked

at Crousedales Dairy Farm in Lexington before opening his own small parlor in the 1980s. With help from his father, he milked about 40 Brown Swiss and Holsteins until stepping away from the business in the early 1990s — not knowing his children, especially his son Josh, would one day pick up where he left o .

“When I was 7 years old, all I wanted was a Holstein dairy cow,” laughed Josh Snider, now married and in his early 30s.

That Christmas, with a little help from Santa, his parents surprised him with a calf he named Annabelle.

“Annabelle really started this whole, I guess you could say, dairy journey,” he said.

Snider showed Annabelle at fairs and 4-H events, winning top honors at an NC State competition. By middle school, Snider was working Saturdays milking 220 Holsteins at a neighbor’s farm. Instead of pay, he asked for calves.

“I didn’t want money,” he said. “I wanted more baby cows.”

In 2011, during Snider’s junior year of high school, the family decided to restart dairy operations.

“We were milking about ve cows with a portable milker,” he said. “And I said, ‘Why don’t we open the parlor back up?’”

Dairy Farmers of America (DFA) agreed to pick up their milk, and they began milking 20 cows. The Sniders restored the barn, installed a new milking system and brought back their original cows — Annabelle, Elizabeth, Jasmine and Chloe.

After graduating in 2012, Snider enrolled at the University of Tennessee with plans to become a vet. But it wasn’t what he wanted. He shifted to animal industries and decided to come home and buy the family farm from his uncle, who had other plans. He gave Snider three years to relocate the cows. Snider spent that time saving money through odd jobs, including delivering mail and milking cows again for neighbors. Eventually, he raised enough to build a new milking parlor.

In 2020, in the middle of the pandemic, Snider’s Dairy Farm opened its new facility with eight cows. Today, the farm milks about 50 — mostly Jerseys, Holsteins, Guernseys and Brown Swiss.

“I’ve just kept building and growing and buying cows where I could and where I could nancially a ord things,” Snider said. Their largest herd expansion came last spring, with the purchase of 22 cows from Virginia.

Caring for the girls

The cows — or “girls” as they are called at Snider’s Dairy Farm — graze in open pastures and enjoy a twice - daily diet of grain and hay, with no added hormones or milk-enhancing supplements. They’re known by name, not number — a deliberate choice that fosters connection and respect.

Snider stressed their commitment to

Josh

“I asked my neighbor if I could milk cows for him in exchange for calves. I didn’t want money. I wanted more baby cows.”

Josh Snider

COURTESY JOSH SNIDER

Snider feeds Annabelle’s great-granddaughter.

animal welfare, explaining that while the cows are pasture-based and have access to grass, they also have the option to retreat to the barn, where fans keep them cool in the summer heat.

“We use medicine for sick animals,” he said. “But it’s important for people to understand that there are no antibiotics in milk. There are no added hormones. That’s just not how it works.”

Community impact

Snider’s Dairy Farm is as much an educational hub as it is a working dairy. The farm hosts hands-on summer camps featuring everything from cow milking and sheep feeding to horseback riding and water slides. Camps are limited to small groups, allowing for a more immersive learning experience. Guided tours and seasonal photo sessions run from June through October, o ering visitors the chance to walk through grazing pastures, try “kid-friendly” milking, enjoy hayrides and take part in themed photo shoots with calves, lambs and other animals.

While the agritourism aspect of the farm raises some money, Snider said it’s important to him to educate the public, especially youths, about the agriculture industry.

“I like to have the kids out here learning where their food comes from,”

he said. “There’s such a disconnect about the process. We want them to know their food doesn’t just magically appear at Walmart.”

The Sniders participate in the Davidson County Farm Tour and host seasonal events like fall festivals. A recent one drew 1,200 people, with proceeds supporting local FFA chapters.

Their milk goes to DFA for processing and distribution through a Winston- Salem facility. Snider said the group has supported them since day one.

“When I was milking eight cows, they said, ‘We’ll keep picking your milk up — just keep milking,’” he said.

Looking ahead, Snider pictures expanding milking capacity to about 100 cows and building a new housing barn within the next two years to streamline operations. He also plans to integrate robotics and continue balancing quality milk production with education — all while working to pay o the new dairy barn.

Snider still thinks about Annabelle — her great-great-granddaughters are now part of the herd.

“That full-circle moment — raising a calf and milking her descendants — it’s hard to describe,” he said. “But it’s what makes it worth it.”

Whether you’re a student learning animal biology or a family seeking a meaningful farm day, the Sniders welcome you into their world — where every animal is a pet and every visitor becomes part of the story.

PHOTOS COURTESY JOSH SNIDER

Josh Snider poses with cows at Snider Dairy Farm in Lexington.

Braswell Family Farms

Four generations built on faith, feed

Braswell is one of the largest specialty egg producers and specialty feed mills on the East Coast

By Dan Reeves North Carolina Farm Life

NASHVILLE — Adaptation, resilience, faith and a deep-rooted commitment to agriculture have kept Braswell Family Farms thriving for more than 80 years.

What began as a small feed mill in Nash County has grown into a major operation that produces nearly 800 million eggs annually and 200,000 tons of feed for chickens, turkeys and hogs. Now led by fourth-generation president Trey Braswell, the company ranks among the largest organic feed producers on the East Coast and is the second-largest Eggland’s Best franchisee in the U.S.

The story began in 1943 when brothers E.G. and J.M. Braswell bought the historic 19th-century Boddie Mill, tied to the original Boddie Plantation — a 10,000-acre land grant from the king of England.

By the 1950s, the next generation faced the familiar challenge of supporting large families in rural North Carolina. They acquired a our mill in downtown Nashville, which remains part of the current mill site. At the time, many families kept “work animals” and backyard livestock to provide for themselves.

“Of course, with donkeys — every family had a cow, a pig and chickens,” Trey Braswell said.

As livestock farming modernized in the 1950s and ’60s, the Braswells shifted to bulk commercial feed, delivering it with their own trailers. Today, about half of the feed produced at the mill supports their own poultry; the rest is sold to other livestock producers — chickens, hogs and turkeys — both organic and conventional.

In the ’60s and ’70s, the egg industry wasn’t vertically integrated. One farm might raise chicks, another lay hen and a third handle feed or packaging. Packaging plants typically controlled the retail relationships. Braswell Family Farms began integrating vertically in the 1970s, starting with their own high- quality feed and later contracting with local farmers to raise pullets — young hens.

“We had the feed — high-quality feed — so we started raising chicks,” Braswell

said. “Then we had our rst round of contract farmers build pullet houses.”

The next step — egg production — was a risk. Their customers were often egg producers themselves. But the family slowly expanded by working with farmers to build laying hen houses and selling eggs to packaging plants across state lines.

In the late 1970s, Trey Braswell’s father took over at age 35 and led the transition to full-scale egg production, building the family’s Red Hill farm in Nash County. His father-in-law added three more houses, marking the start of full vertical integration — from feed to farm to egg.

In the early 1990s, a key turning point arrived with the development of what was then called Heartland’s Best, now Eggland’s Best. Created by two Japanese innovators, the brand used a patented feed formula to produce a healthier egg — lower in cholesterol and saturated fat, and higher in omega-3s.

“At the time, eggs had a bad reputation because of cholesterol,” Trey Braswell said. “Producers were desperate, saying if we can’t do something di erent, like Eggland’s Best, we probably won’t make it.”

Though backed by science, early marketing e orts ran into legal and regulatory headwinds.

“It was a very rocky run getting going,” Braswell said.

Despite nancial troubles and bankruptcy, a group of farmers — including the Braswells — invested and bought the company, gaining equity. Braswell said his father made that decision shortly after his grandmother died. It proved crucial. By the mid-1990s, Eggland’s Best had exploded nationally, reaching nearly every grocery store in the country. “It was in 97–98% of grocery stores across the country,” Braswell said.

Technology has also transformed the operation. Machines now wash, dry, inspect and weigh eggs at a pace of 500 cases — 30 dozen eggs in each — per hour.

“A human can’t do that,” Braswell said.

Braswell Family Farms now o ers cage, cage-free and pasture-raised eggs, tailoring options to consumer preference while emphasizing bird health and welfare across the board.

“Regardless of the system, quality and care are very important,” he said.

All operations are third-party audited, and nutritionists help ne-tune feed formulas.

The business hasn’t been immune to industry challenges. Bird u outbreaks have decimated ocks across the country, sending egg prices soaring — but Braswell Family Farms has remained untouched.

The farm has also faced growing pressure from animal rights groups advocating for nationwide cage-free

STAN GILLILAND / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

Boddie Mill, named to honor Braswell Family Farms’ history, is in Nashville.

family company in

mandates. Braswell called some of their tactics extreme — accusing activists of staging videos and pressuring retailers to change policy.

“You’re turning a $2 egg into a $5 egg — and that’s not sustainable for most families,” he said.

As the egg industry shifted toward e ciency, so-called “inline farms” — large-scale operations with on-site processing — became standard. In 1999, Braswell Family Farms opened its rst inline farm in northern Nash County. The 50-acre site houses 1.2 million birds in conventional cage production.

By contrast, their pasture-raised ocks — about 250,000 birds — require 10 times the land. “Those are about $8 to $1 in terms of cost,” Braswell said.

Trey Braswell’s own path into the family business wasn’t without its hurdles. After graduating from NC State in 2003 with a degree in business management, he planned to forge his own way. But in 2008, a series of family health crises — including his cousin’s cancer, his grandfather’s

emergency surgery and his father’s illness — pulled him back home. At just 21 or 22, he stepped into the business with little experience and a steep learning curve.

“It was certainly, like they say, drinking water from a rehose,” he said.

Braswell credits strong mentors, family, support from local business leaders and a Christian business leadership group known as C12 for helping him nd his footing. The group, which functions like a “personal board” for business owners, blends practical business guidance with faith-based leadership and peer support.

“That’s been really critical,” he said.

Under his leadership — in lockstep with the generations who came before him — Braswell Family Farms remains one of the largest organic feed producers on the East Coast and the second-largest Eggland’s Best franchisee in the country, with a bright future ahead.

“For some reason, God has had His hands on this company,” Braswell said. “We seek to honor Him and glorify Him

“For some reason, God has had His hands on this company.”

Trey Braswell

in the way we run this business and how we take care of our people. We’re building on the foundations laid by the generations before us.”

STAN GILLILAND / NORTH CAROLINA FARM LIFE

The original Boddie Mill on Boddie Mill Pond is where E.G. and J.M. Braswell rst started the

1943.

Pork council fuels record BBQ season, supports NC farmers, tradition

Across

the state, the NC Pork Council champions whole hog barbecue and local agriculture

By Dan Reeves North Carolina Farm Life

WHEN 4,775 barbecue sandwiches were sold in under ve hours at this year’s BBQ Fest on the Neuse in Kinston, it wasn’t just a Guinness World Record — it was the latest milestone in a long tradition upheld by the North Carolina Pork Council.

“This is about more than just pork,” said Roy Lee Lindsey, CEO of the North Carolina Pork Council. “This is about community, about giving back and about preserving a deeply rooted North Carolina tradition.”

Under Lindsey’s leadership, the council has continued to elevate whole hog barbecue as both a cultural cornerstone and a tool for community development. For more than 40 years, the council has sanctioned local barbecue contests across the state, from mountain fairs to coastal towns. Each competition supports a local nonpro t, school or volunteer

re department. In the last ve years alone — excluding a pause in 2020 due to COVID — these events have raised more than $1.1 million and drawn more than 420,000 attendees.

“Our farmers are a part of these communities,” Lindsey said. “They’re school board members, church leaders, remen. They believe in this work because they live in the places that bene t.”

This year’s festival in Kinston was already the largest whole hog barbecue competition in North Carolina. With 100 cook teams and hundreds of volunteers, it became the ideal site for a record-setting

COURTESY NC PORK COUNCIL

North Carolina Commissioner of Agriculture Steve Troxler poses with state champion Kevin Peterson, chief cook of Showtime’s Legit BBQ, at the Got to Be NC Festival in Raleigh.

collaboration with Guinness World Records. The council began planning the attempt 18 months ago, coordinating with Guinness on category rules, food safety protocols and adjudication.

“Because the community in Kinston has been doing this for four decades, they knew how to run it,” said Lindsey. “The Guinness adjudicator even told us it was obvious we’d done this before. We had the volunteers, the infrastructure and the experience to pull it o .”

Smith eld Foods, the nation’s largest pork producer and a longtime supporter of the council’s e orts, helped underwrite the record attempt and contributed pork for the event. Earlier this year, the council and Smith eld also teamed up to donate 30,000 pounds of pork and $30,000 in funding to Manna Food Bank in Asheville, supporting ongoing hurricane recovery in the region.

Got to Be NC

Following a record-breaking BBQ Fest on the Neuse, the North Carolina Pork Council kept the momentum — and the

“This is about more than just pork. This is about community, about giving back and about preserving a deeply rooted North Carolina tradition.”

Roy Lee Lindsey, North Carolina Pork Council CEO

smoke — rolling into Raleigh for the 2025 North Carolina Whole Hog Barbecue State Championship, held during the Gotta Be NC Festival at the State Fairgrounds.

There, the best of the best faced o after qualifying through dozens of sanctioned contests across the state.

And when the smoke cleared, Kevin Peterson, chief cook of Showtime’s Legit BBQ, claimed rst place, earning $2,000 and a trophy by North Carolina

Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler.

“This win is a huge honor,” said Peterson. “To compete alongside the best pitmasters in the state and come out on top — that’s what we all work for.”

Lindsey called the Gotta Be NC Championship “the Super Bowl of whole hog barbecue in North Carolina.”

“We’re proud not just of our champion, but of every team that carried their local tradition all the way to the state stage,” Lindsey said.

Celebrating 20 Years

Prestage Foods is proudly of producing quality turkey products for customers around the world!

Two Decades of Dedication:

Thank you to our entire team at Prestage Foods in St. Pauls for your commitment to quality and customer satisfaction!