Local publishing legend Keith Roulston discovered a passion for live theatre while studying journalism at Ryerson University in Toronto

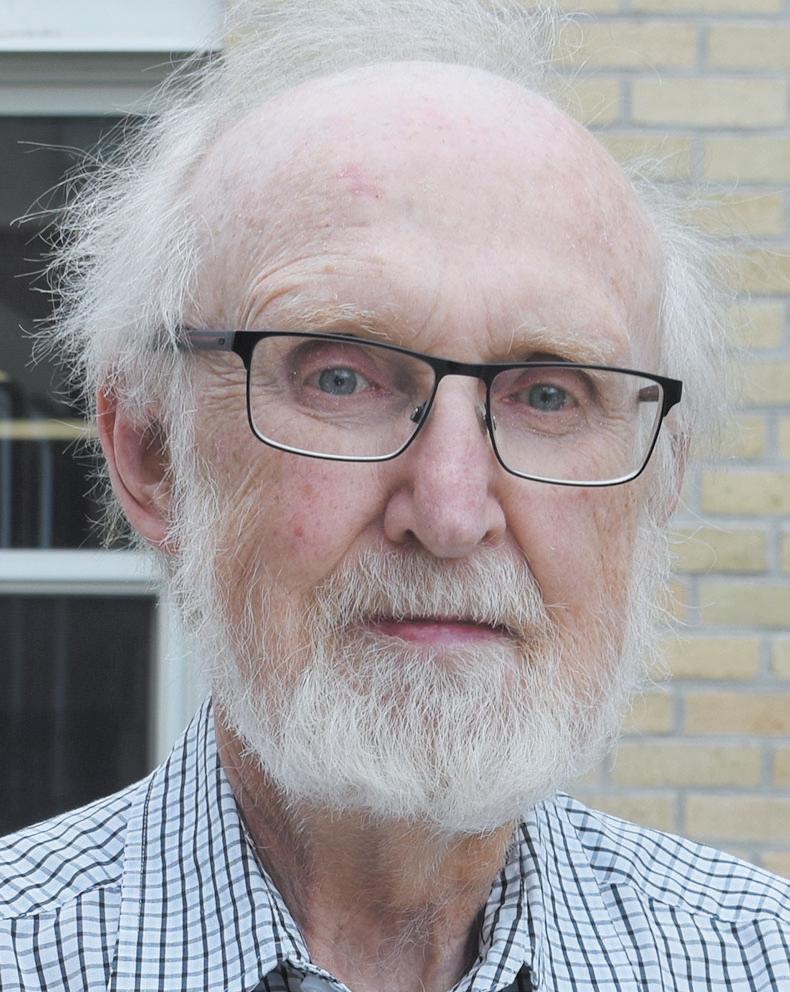

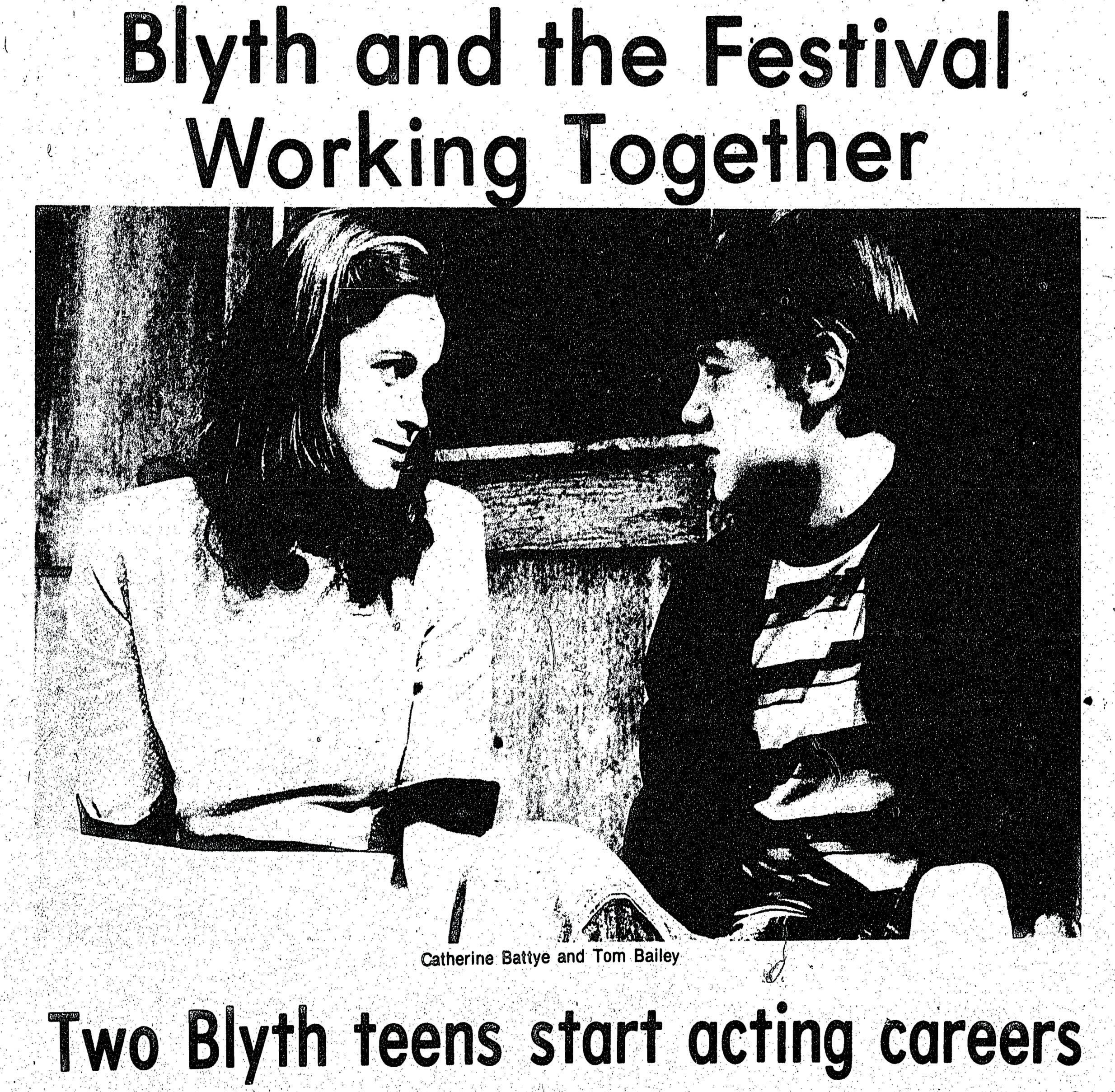

Ontario Community Newspaper Association Hall of Famer Keith Roulston co-founded the Blyth Festival in 1975. Throughout the subsequent decades, he has served as the Festival’s general manager, president of the board, and lauded as a frequent playwright. (Scott Stephenson photo)

By Scott Stephenson The Citizen

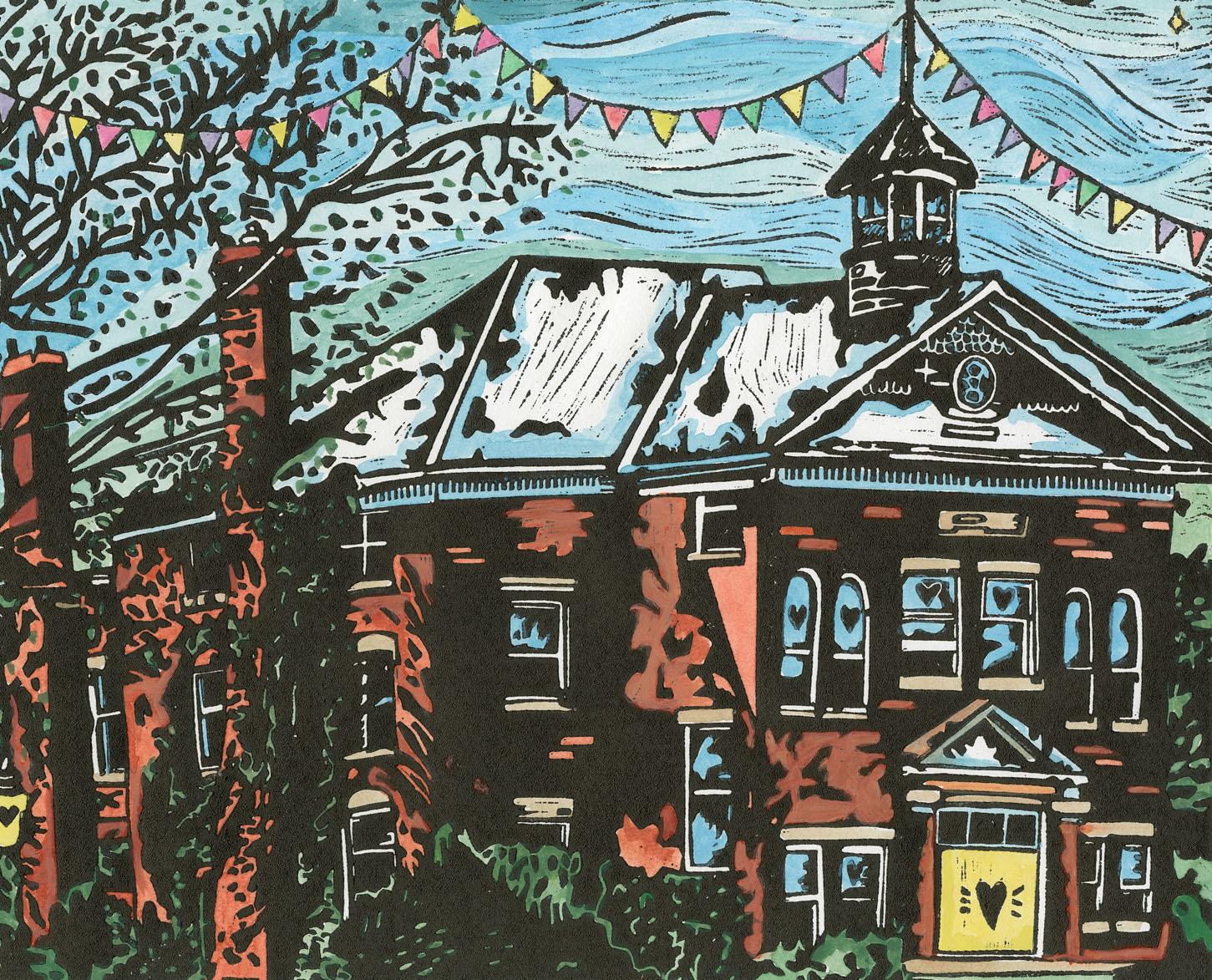

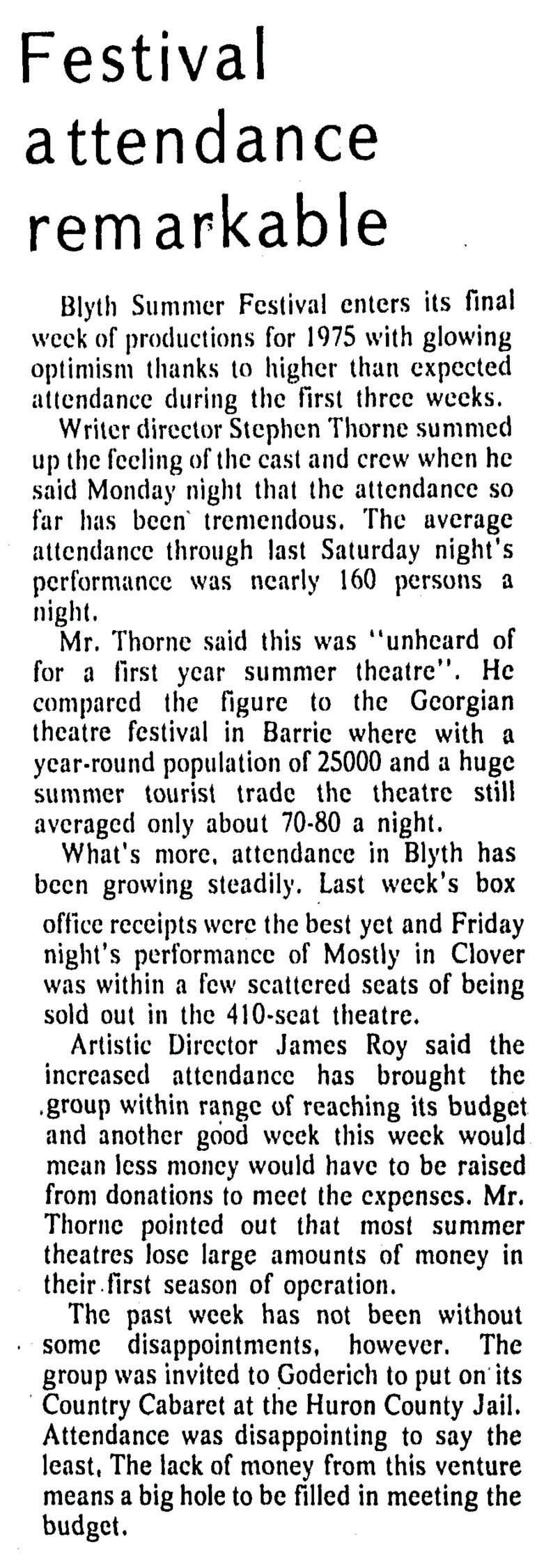

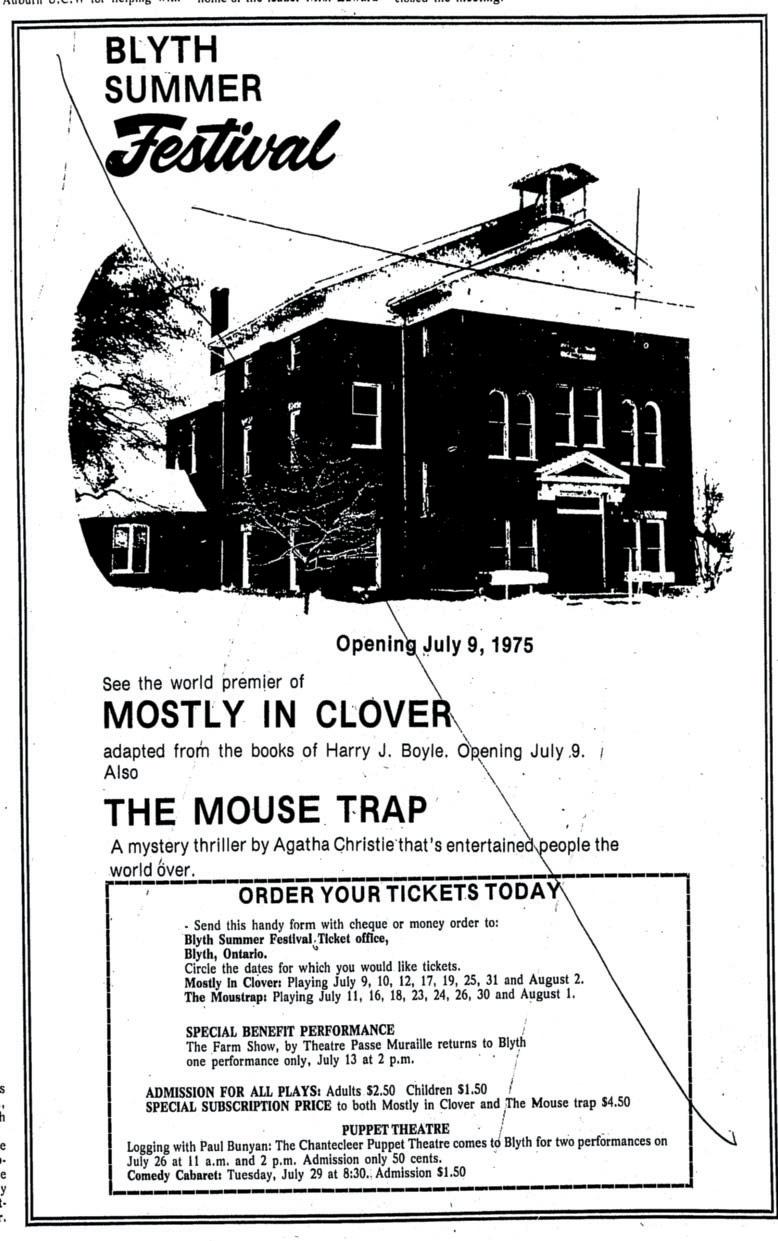

As the story goes, James Roy, Anne Chislett, and Keith Roulston came together in the Village of Blyth in 1975 and hatched a radical and innovative idea - to create a rural theatre festival that would enrich the lives of its audience and give a voice to the community. But

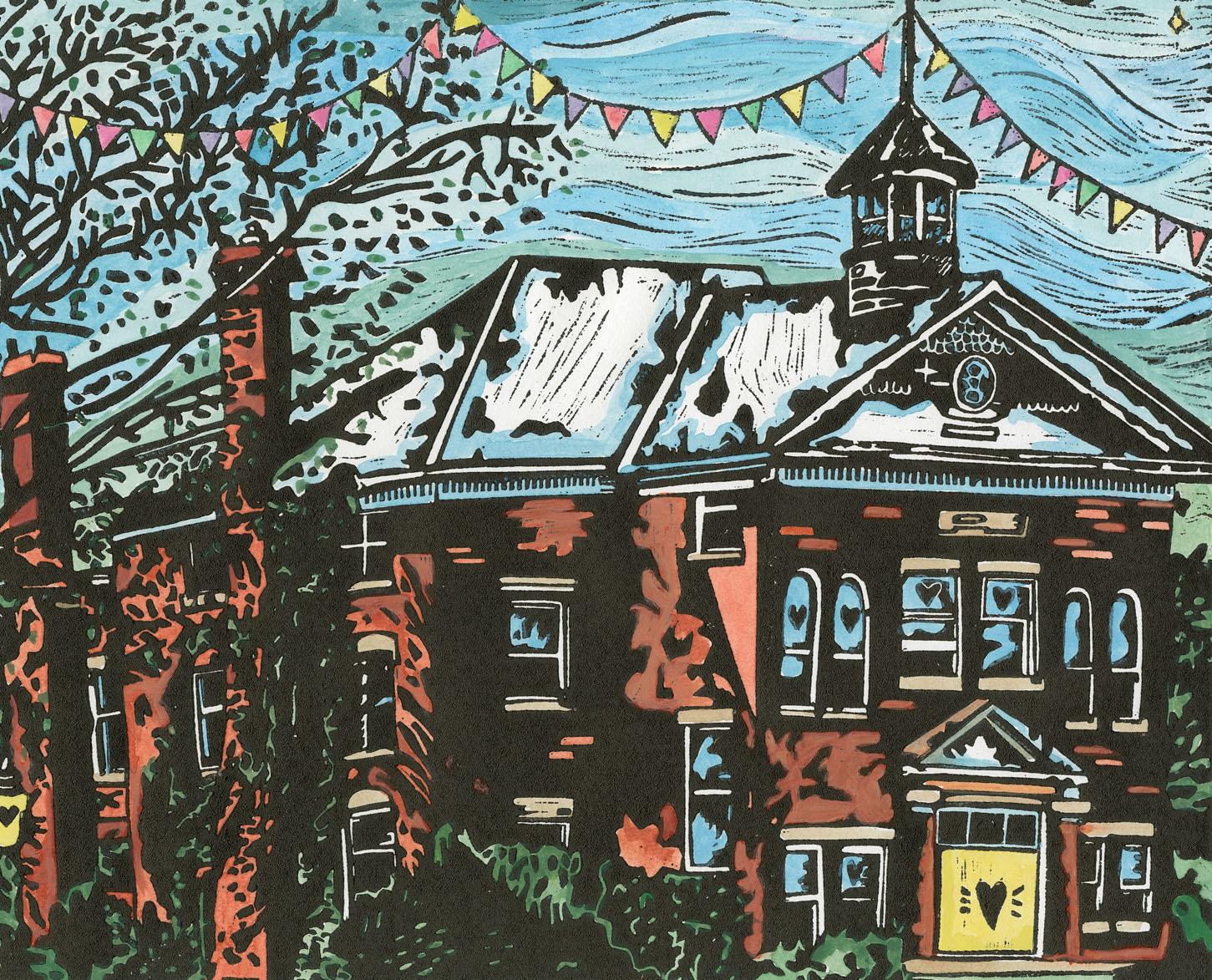

the full story of the Blyth Festival actually began decades earlier - in 1920, the year that the cornerstone of Blyth’s Memorial Hall was laid. Because, without Memorial Hall, there would be no Blyth Festival. The construction of the stately space came about as part of the local community’s collective dream - to honour the brave men and women who had served in World

War I, which later expanded to include those who served in World War II. First and foremost, Memorial Hall has always been a living cenotaph designed with the intention of honouring the unassailable spirit of those who fought, by giving the community a place to gather, and be entertained, together. Now, over 100 years later, the hall and the people that populate

it still strive to fulfill that dream.

Lucknow-area native Keith Roulston has capably served the Blyth Festival in many capacities over the years. He was the first-ever chair of the Festival’s board of directors, has written numerous well-received plays, and served several stints as its general manager. Over the course of many decades, as various artistic directors came and went, Roulston remained the Festival’s consistent connection to the local community. But when he first encountered Memorial Hall in 1971, Roulston was on the hunt for captivating content he could use in the pages of the local newspaper that he had just taken over. “When we bought the old Blyth Standard, we were taking over a paper that was printed in the old letterpress way, so there were no pictures in it,” he recalled. “I wanted to get pictures. I wanted to knock people on their rear-ends right off the bat with the pictures that we took!”

He didn’t know it at the time, but the paper’s offices were located just a few steps away from Blyth’s longrunning event space. “I heard that there was a variety concert going on at a place called Blyth Memorial Hall, which I had never heard of before.” Roulston grabbed his camera and headed to the hall in hopes of capturing some entertaining images worthy of the front page. The moment he stepped into the building, he saw a future in it. “I looked around, and I was just so impressed with this building, even though it was in god-awful shape. The curtains? There were no curtains. There were flats on the stage so [people] didn’t fall through... I started thinking that it was too bad that such an old building was not being used morethat it should be something.”

Roulston may be best known as a local boy who grew up with a penchant for founding newspapers, but his second-most-pressing passion was born while he was out in the world, seeking an education. “I had fallen in love with theatre when I was going to Ryerson in Toronto. The Royal Alex had just been sold to Ed Mirvish, and he was always bringing in touring shows, and he couldn’t always sell all the seats that were there, so he came to Ryerson and offered all the extra tickets to the Radio and Television Arts (RTA) department. I had a roommate that was in RTA, and he got tickets for both of us to go to the shows.”

Roulston quickly settled into his new role running the local newspaper. “I became good friends with Helen Gowing who ran the needlecraft shop... there was still a Blyth Fall Fair in those days, and the next summer, Murray Scott, the president of the Blyth Fall Fair, came to Helen, and said that the [Canadian National Exhibition (CNE)] in Toronto had just started up a Queen of the Fair competition, and they wanted all the rural fairs across Ontario to have their own Queen competitions and send their winners to the CNE.”

Roulston thought that Memorial Hall would be the perfect place for Blyth’s Queen competition, and he and Gowing set about making it so.

“We had a whole bunch of volunteers that went in and started to clean things up, and we cleaned out the whole place, and so on,” he explained. At that time, the team may not have had an exact vision in mind for the hall’s future, but the members shared a common desire.

“We dreamed of making it into

Continued from page A4 some place that could be used.”

Just when it seemed like that dream was about to become a reality, conflict arose. “Irvin Bowes was the fire chief of Blyth when it was still its own village. He read what we were doing, and he said ‘I’ll let you have this event, but you can’t keep on using Memorial Hall for any more than that, until you get a proper fire escape. We had found the money for paint and cleaning and so on, and so forth, but we didn’t have the whole $35,000 that was needed - that was big money in those days, and we didn’t have any access to funds like that.”

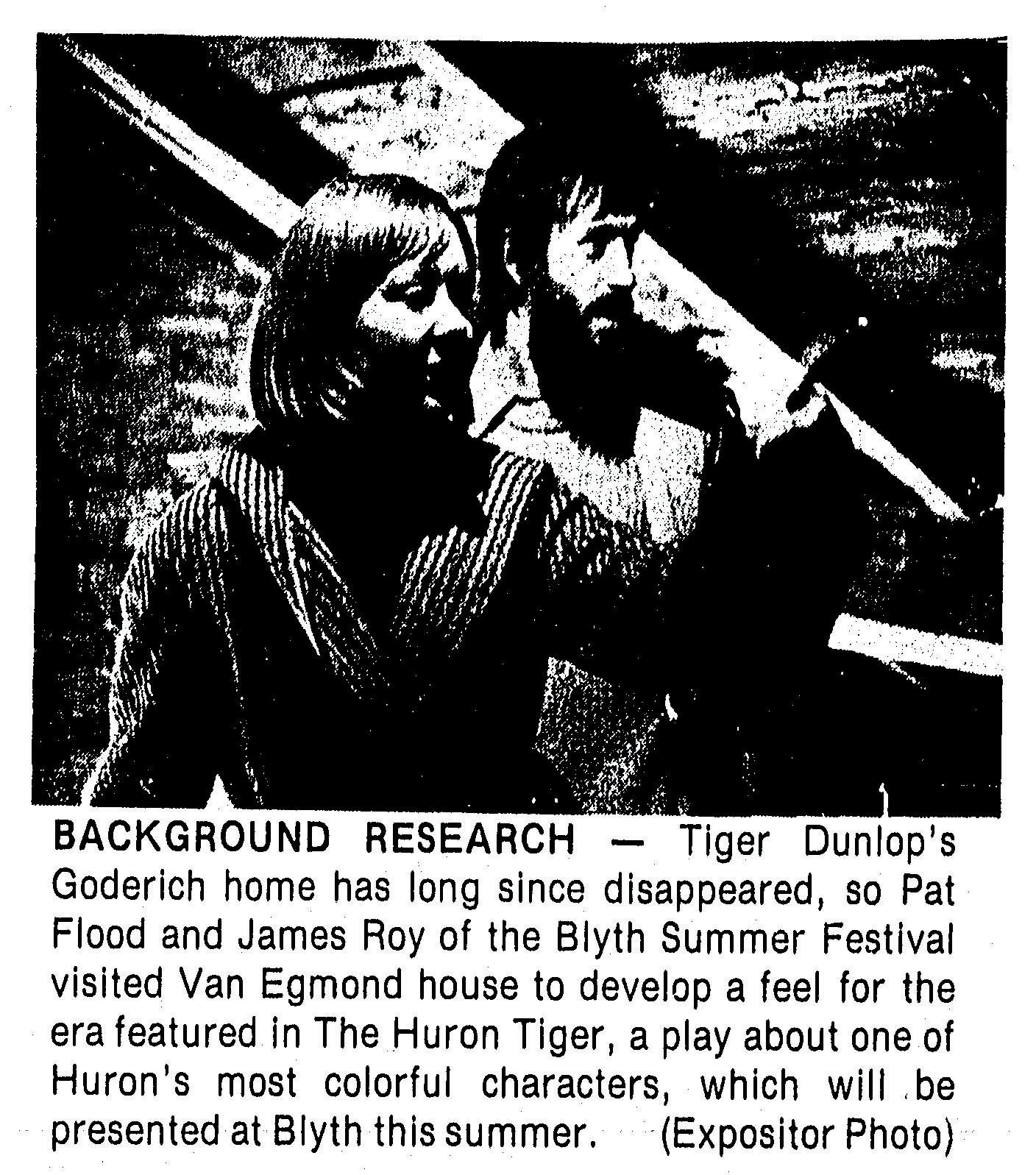

Around the same time, Roulston was covering the monthly meeting of the Federation of Agriculture for The Blyth Standard. Fortuitously, one such meeting fell on the same day as a street fair run by the Clinton branch of the Lions Club. “While I was there, I ran into Jim Fitzgerald, who had taken over the Clinton News-Record, which I had been the editor of before I came north to Blyth. I had read a story in his paper - that there was a group of actors west of Clinton who were researching a show that they were going to do about the community. And then along came Paul Thompson, at this street fair we were at, and Jim introduced me to him. I kept telling him about what we were doing in Blyth, and how he should come back and do stuff at Blyth Memorial Hall. And so I ended up going when they had The Farm Show in the barn - I saw the

very first performance of it. Little did I know that James Roy was also there - he saw the show too.”

Roulston remembers his first experience with The Farm Show vividly. “I knew some of the people that were portrayed on the stage. They had a luncheon afterwards for all the neighbours - it was the cast’s chance to show off what they had worked on after talking to them while they researched the show... it was pretty magical. Especially because I took my wife, Jill, and our oldest daughter. We sat in the haymow, in the old barn, and Christina was two, playing around in the hay.” Romping around with Roulston’s daughter was Paul Thompson’s daughter, Severn Thompson, who now works for the Festival, as well as future Blyth Festival artistic director Janet Amos’ son, Christopher.

While Roulston was observing the birth of The Farm Show in a barn in Clinton, Blyth’s theatrical future was still hanging on the balance of a busted fire escape. “Finally,” continued Roulston, “the council came up with enough money to build the fire escape. But then somebody said, ‘well, that building was built in 1920, Lord knows what the wiring is like - we better make sure that that’s safe’. And so an inspector took a look, and he said ‘it’s not great... but it’s not unsafe.’ So then, it seemed that we were all set to get the fire escape built.”

But then complications escalated, and the stakes were suddenly

higher. “Another councillor, who happened to be a builder, looked at the roof and said ‘I think there’s a sag in that roof - I think we need to investigate that.’ So then we brought in an engineer, and we found out they’d poorly designed the roof - one roof ran into the other, and so the roof wasn’t safeit had to be replaced. And the first quote they had was $75,000, and that was not going to fly with anybody.” A new quote, for a marginally more manageable $50,000, was brought forth. Members of the community rallied around the effort. “Finally, the Women’s Institute (WI) came forward, and they were very supportive - they thought something should happen there. They were the group who were behind the building of Memorial Hall in the very first place. They said, ‘This is the memorial for the soldiers of two World Wars - we’ve got to fix this up.’” This impassioned assertion from the WI reached the ears of the local council. “Eventually, in the fall of 1974, council agreed to replace the roof on it. If you look at The Blyth Standard in the fall of 1974, you can see photos where they were tearing off the roof.”

The repairs took time, however, and Roulston felt that he may have missed his chance to bring Paul Thompson back to town. “By this time, Theatre Passe Muraille had given up on Blyth, and they had gone and set up in Petrolia. But then, that winter, after James Roy had graduated from York University, he went to Passe Muraille, and did a show there. Afterwards, he was talking to Paul, and told him he really wanted to start a summer theatre.” Thompson

promptly advised Roy to get in touch with Roulston. “I got a letter from James, and that’s where it all began.”

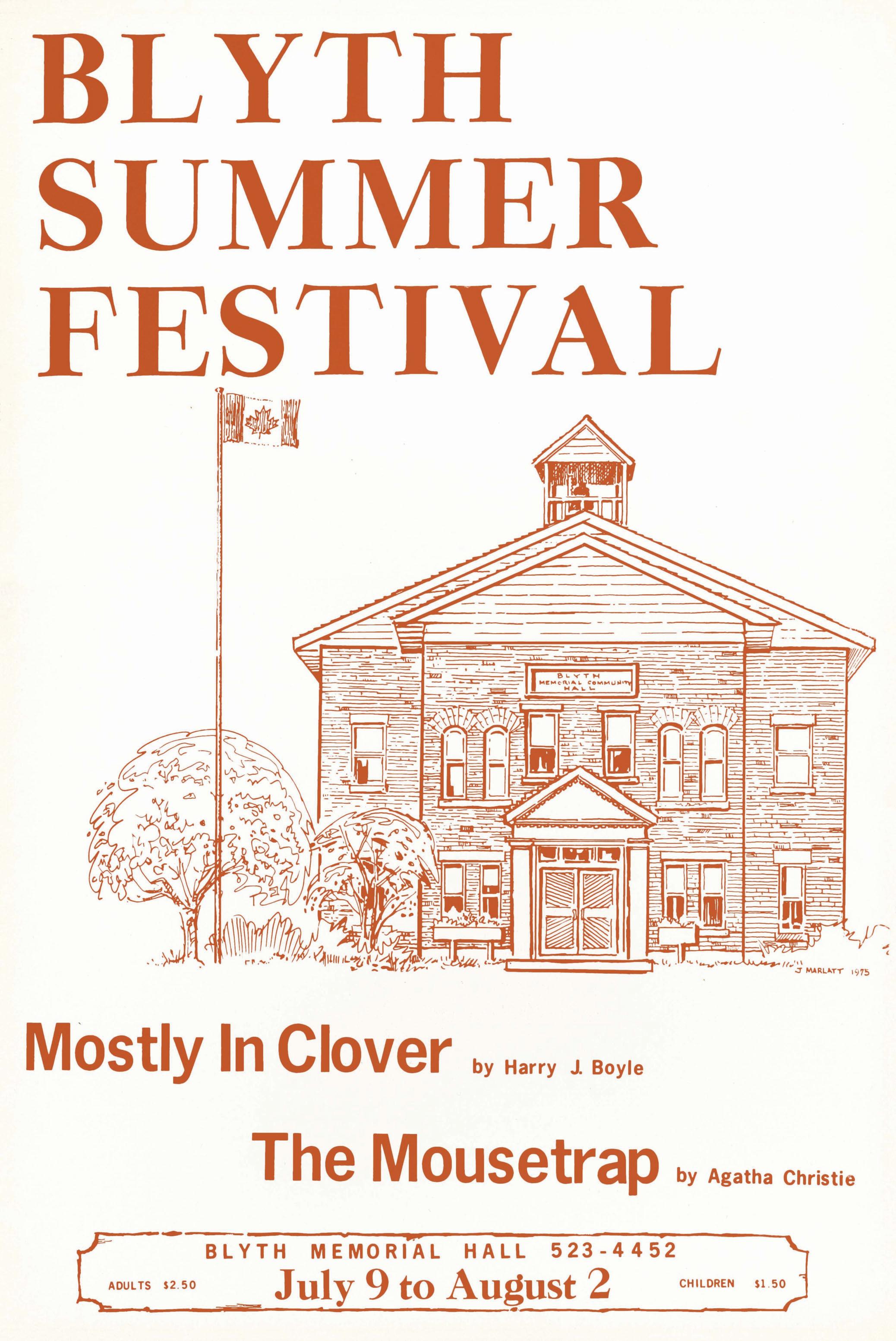

The people of Blyth had worked so hard together to revive their beloved performance space, and entrusted Clinton’s own James Roy to provide programming guidance as its first-ever artistic director. Roulston thinks it was the right move. “That very first season, when we had decided we were going to go ahead and have a theatre, it was all in James’ hands as to what was going to go on the stage. He came in, and he’d just been at his mother’s place, and he certainly remembered the books of Harry J. Boyle. He got the books off the shelf, and he thought ‘yeah, there’s stuff here we can do a play out of.’ And so he came to me with the idea, and I thought it was wonderful.”

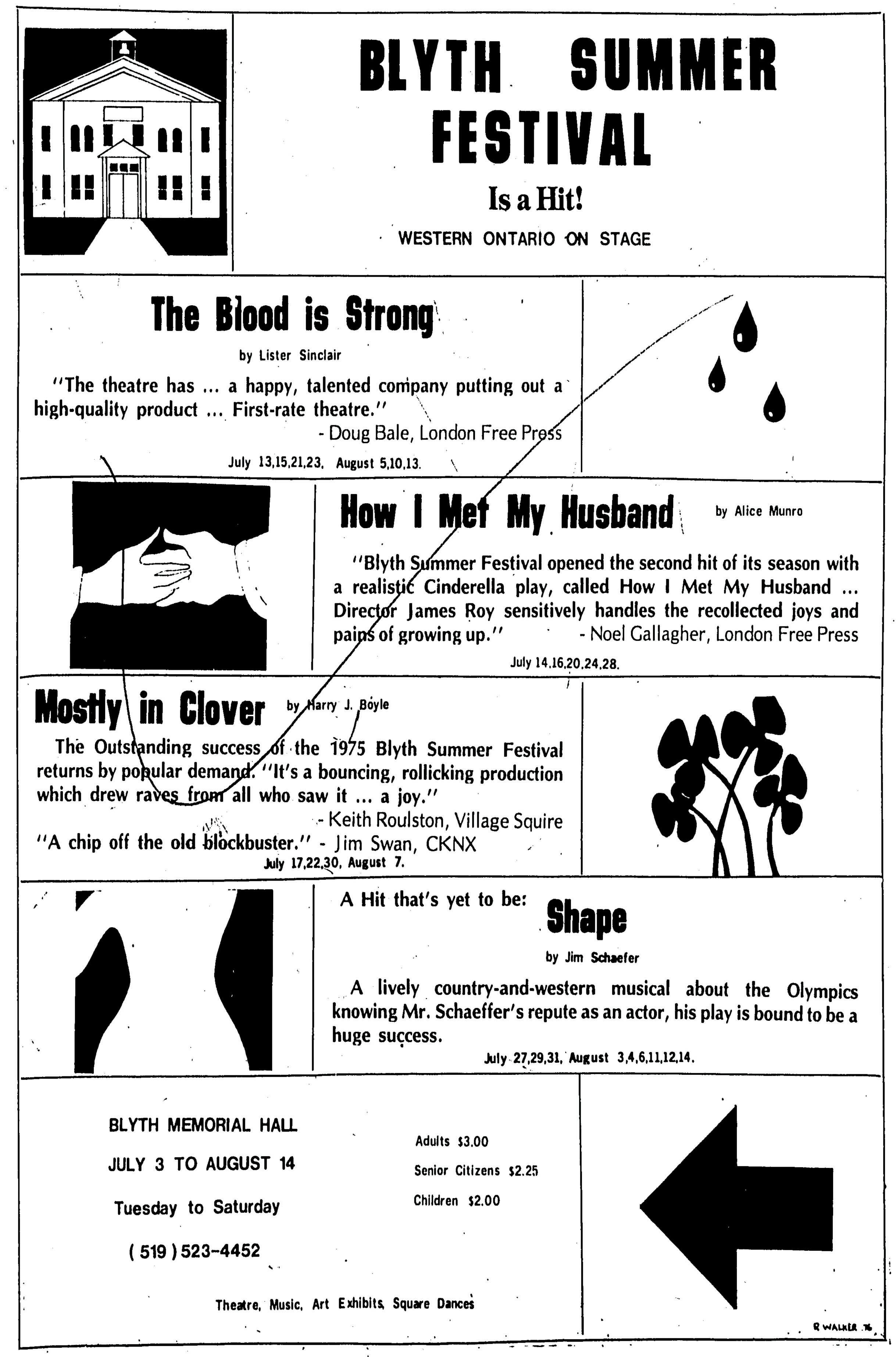

The play that was born of that idea, Mostly in Clover, was the Festival’s first original production, and its first smash hit. “And that made James’ mind up - from then on, he was going to do only Canadian plays, or only plays that had a local bearing.”

On the opening night of Mostly in Clover, there was no seating in the balcony due to the continued lack of a working fire escape for that portion of the building. There was

also no air conditioning. “It turned out to be a hot night, and the dedication ceremony ran long,” Roulston recalled. “It went on and on and on, and the heat went up and up and up - people were starting to stick to the wooden seats, and the cast was backstage, and they were so hot! They kept asking ‘are we going to do this?’ Finally, all the ceremonies were over, and they started the show! And there was a first laugh, and a second laugh, and it just built, and built, and built, and

Continued from page A5 there was a standing ovation at the end.... A big friend of the Festival was Jim Swan, who was at the CKNX radio and television station. He came that night, and he had a recorder, and he interviewed all of the actors who were in the cast.

After he finished that, everybody went downstairs, and there was a big party. When we were heading out afterwards, I remember Robbie Lawrie - who was the reeve of the village at that point, stopped me and said ‘I think you’ve got a hit there.’ By the end of the season, that show was selling out all the performances. The word of mouth had gone around, and we did an interview in the paper and so on.”

Roulston’s own foray into playwriting came about shortly thereafter. “Probably, with Paul Thompson being around, I got interested in telling stories. I finished my first play while James Roy was here, and I showed it to him, and he was kind of interested, but it needed to be worked on, so we reworked it, and it was put on in 1977, at the very end of the season.

There were six performances, or something like that. And I was so broken-hearted that that was all it was going to get.” That play, The Shortest Distance Between Two Points, tells the tale of the residents of a fictional small town that’s found itself in the middle of a government plan to construct a highway right through the middle of town. It may have had a short first run, but The Shortest Distance Between Two Points has since been remounted elsewhere.

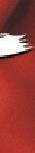

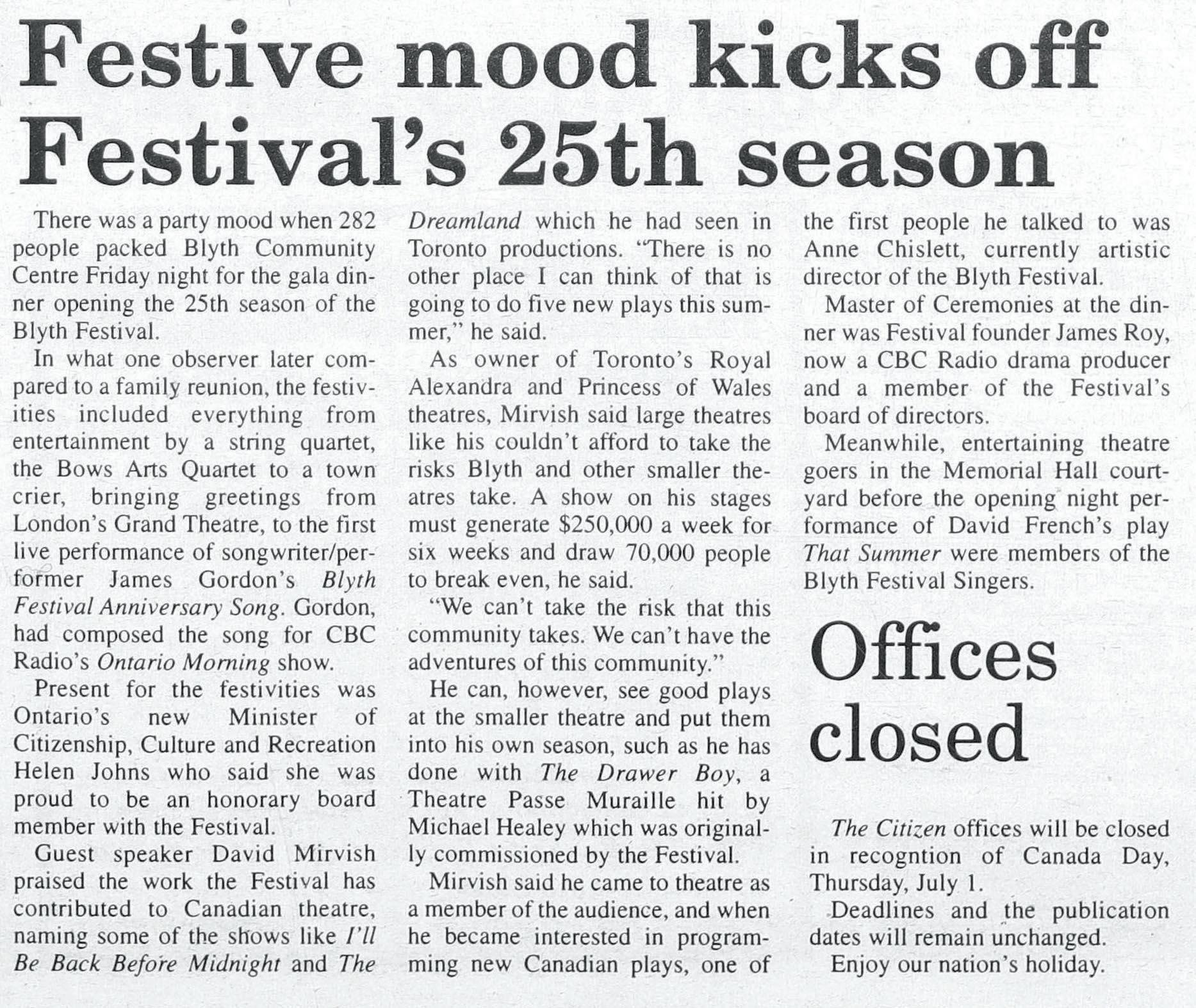

Once he started writing plays, Roulston found it was hard to stop. “I wrote three while James Roy was here. I wrote something else that Janet put on, but I don’t claim it now, because it got reworked so much. Anne Chislett and I wrote a play together called Another Season’s Harvest, about the farming crisis of the 1980s, when the price of farmland had gone suddenly a lot higher, and the interest rates went up to something like 20 per cent. And so farmers that had bought land, and thought that they had a mortgage that was going to do, and the mortgage became renewed, the interest rate was now so high there was no way they could keep a hold on that land. Up in Bruce County, the bank was coming in and taking

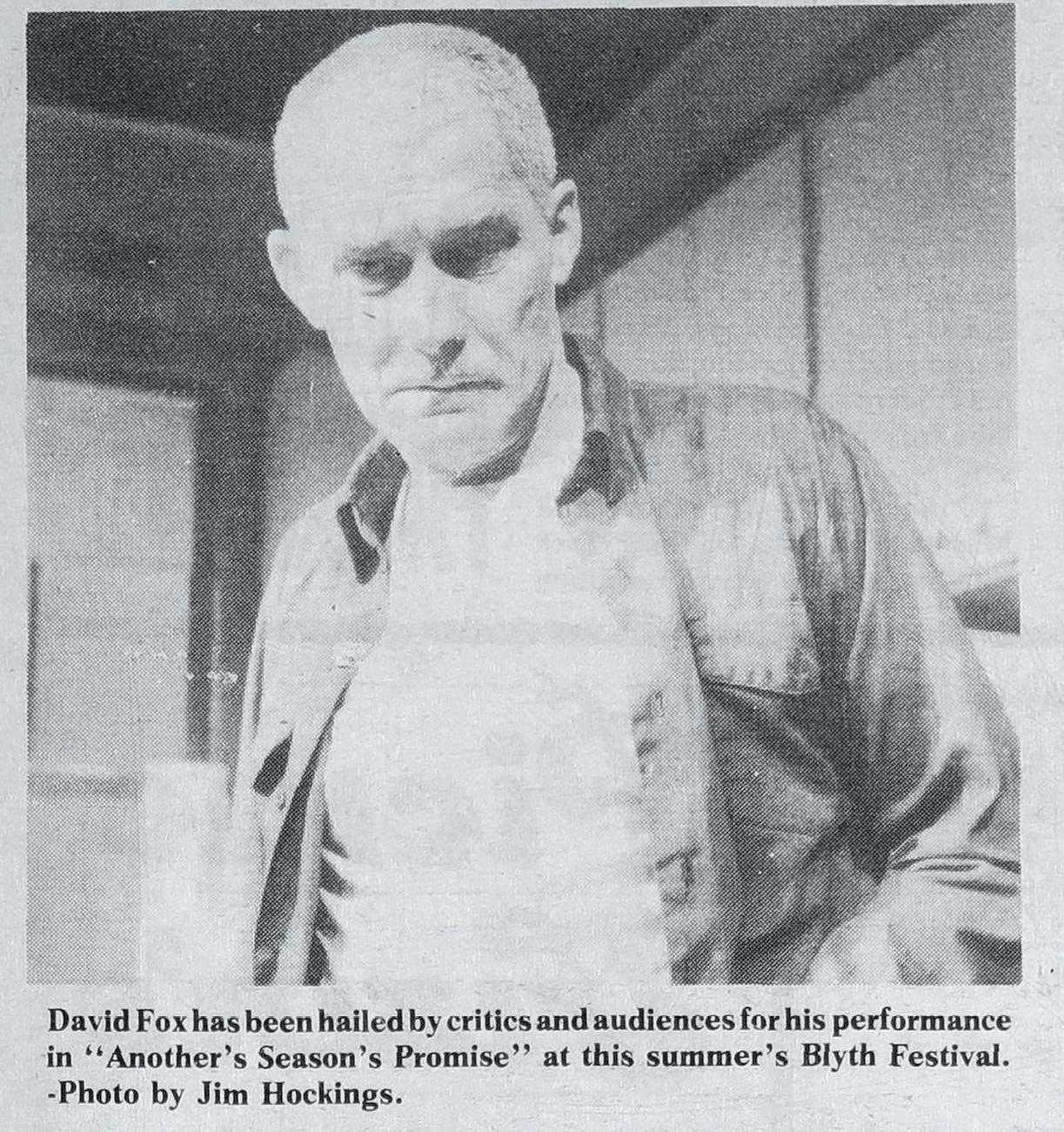

over some of the farms from the farmers that were there. They had penny auctions, and people would buy the farm for a fraction of what they’re worth, and the police were involved, and so on and so forth. I did all the research on that, and Anne did a lot of the writing, and we created this play, which was a mammoth hit.” Another Season’s Harvest returned for a second year, and later went on a national tour. Roulston and Chislett revisited that play for the farm crisis of the 1990s and early 2000s in what became Another Season’s Promise

In the fall of 1979, James decided to leave the Blyth Festival, and Janet Amos took over as its artistic director. At that point, the Festival had become popular enough that it needed to hire its first full-time general manager. Roulston applied for the job, and landed the position. Thus ushered in the era of Janet Amos as artistic director. Roulston recalls that time fondly. “She was so dedicated. The irony was that Janet was a downtown Toronto girl, but she became so Huron County. She came to perform in The Farm Show, and then she married Ted Johns, who was a Huron County boy. So she took over, and was going out, and researching plays, and finding stories to tell, and she brought Ted, who got into writing big time - they built a huge audience.”

After Amos moved on, Katherine Kaszas moved in. “Katherine was not from Huron County, but she came and lived in Huron County.”

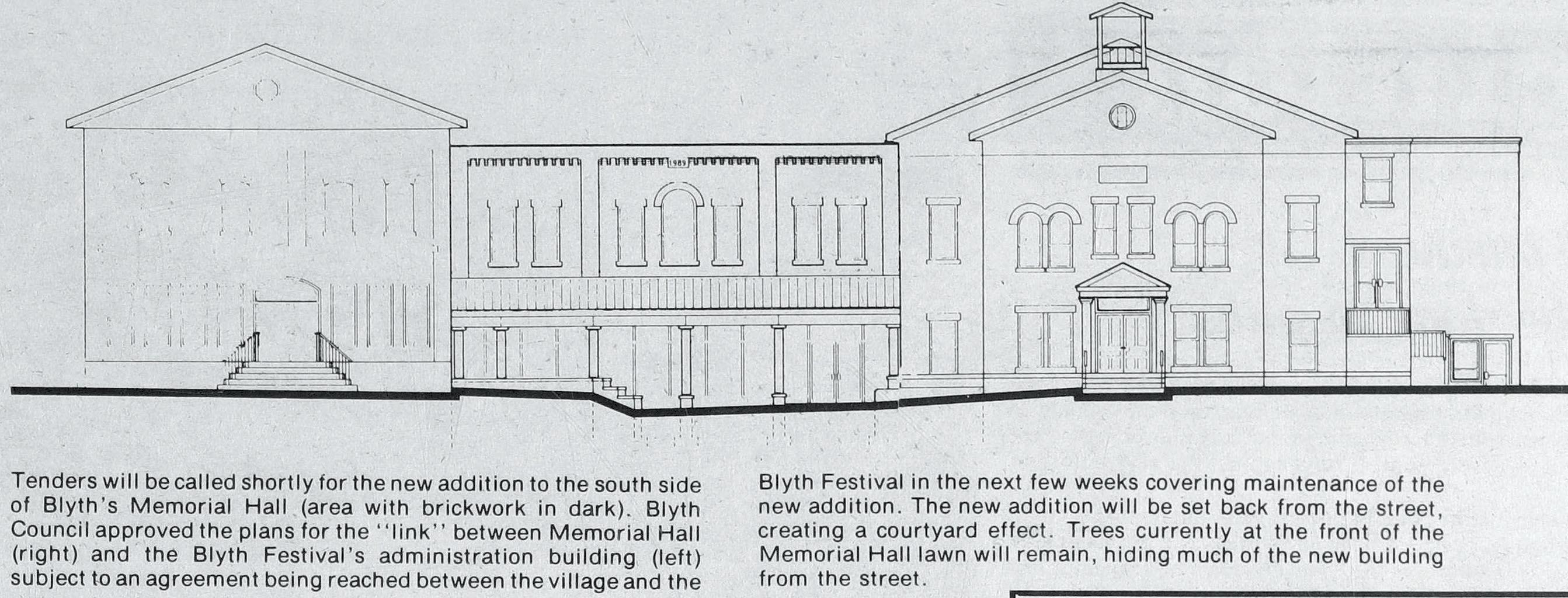

Roulston remembers her reign as a time of rapid growth. “James built it this big,” he gestured, “and then Janet built it bigger. Katherine came along and built it to the next level. Huge, huge, huge attendance. Katherine was also in charge of building what we call ‘The Link’, which is that whole part that has the art gallery in it, and attaches to where the offices are. Huge growth when Katherine was here.”

The end of the Kaszas age brought about a new kind of leader in the form of Peter Smith - a somewhat tumultuous, but interesting time period for the Blyth Festival. “Peter was a little unfocused. The theatre had built itself way up, so when Peter did some shows that weren’t popular with people, they ran into a huge deficit.... That’s when the chair of

the board came to me and to James Roy - I was running The Citizen by that point - and asked us to come and talk about how to get things back on track. So I came back on board, and James, and Jim Swan, and Paul Thompson were on the board, and we approached Janet about coming back for the second time.” Amos agreed, under the condition that Roulston would be president of the board. “So I spent another four years as her president... she rebuilt the Festivalit had gone right down.”

When Amos decided her second run had come to its natural conclusion, Anne Chislett stepped up to the plate. She hired Eric Coates as an actor, and eventually offered him the job of assistant artistic director. “She really came to trust Eric,” Roulston remarked. Coates eventually went on to succeed Chislett as artistic director - a position he held from 2003 to 2012. They didn’t always see eye to eye creatively, but Roulston grew to respect the man’s dedication to both the Festival and the community. “Coates threw himself into it - he was so involved. He came from Stratford - he had family there, he had a house there - but he wanted to be in Blyth as much as possible. He was dedicated to the community. For instance, he would always get his hair cut in Blyth. So he was going to the barber, and catching up on the community based on what the barber had picked up at the shop. He was just so involved.”

When Coates vacated the position for greener pastures, Smith returned as the interim artistic director. “Eric had picked most of the season before he left. So [Smith] was in charge of making sure the directors were hired and the actors were hired... while he was here, he was also involved in the renovation project to bring Memorial Hall up to 2014 standards.”

Following Smith’s brief return to

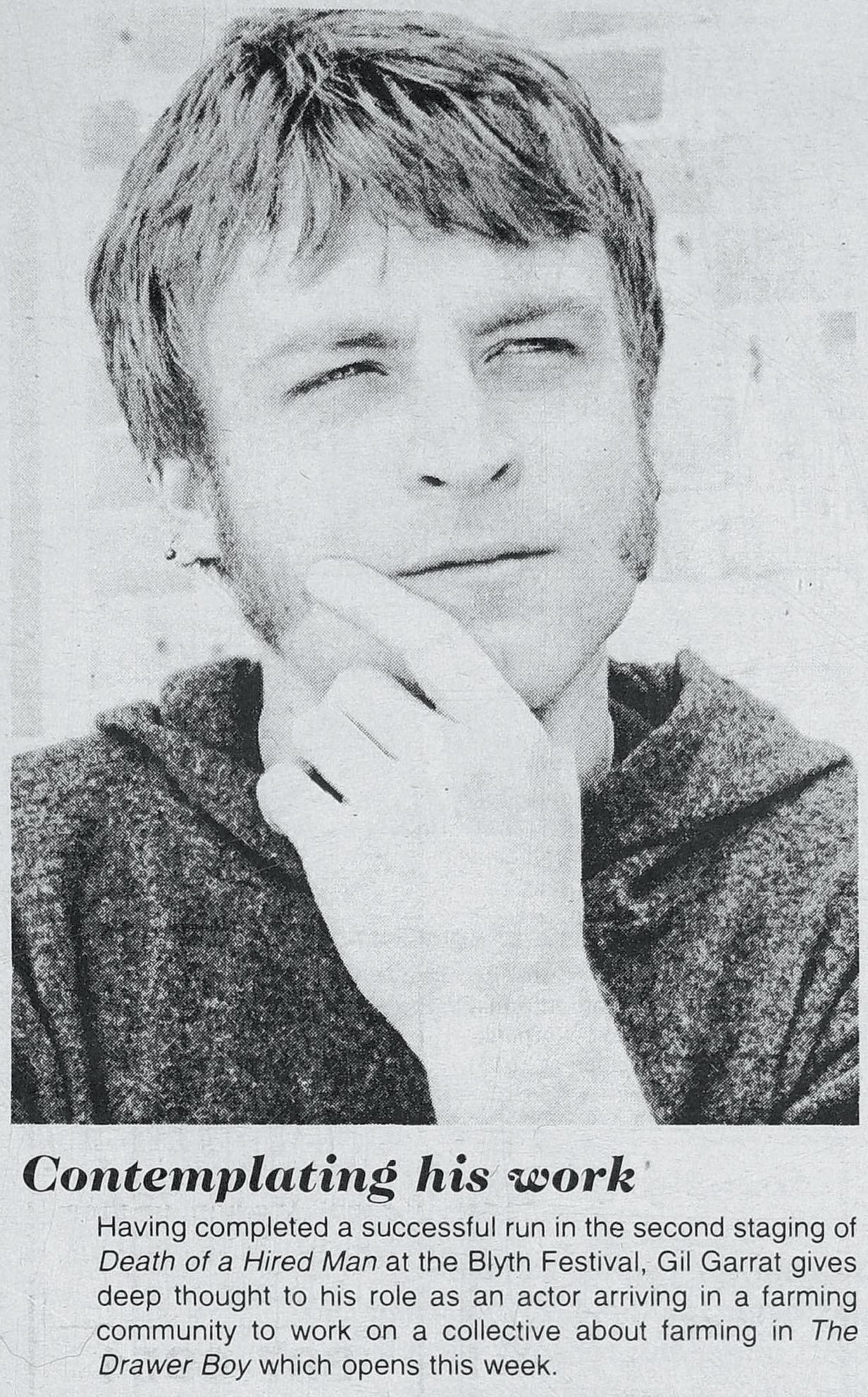

the chair, frequent Blyth collaborator Marion de Vries took the reins. “She came in, and she was just thrown into the middle of it. She was planning a second season, which I was going to have a play in, but then they replaced her with Gil Garratt. He’s been in a difficult era, with the pandemic and that. You look around the country, and that was just the end of a lot of theatres - Gil successfully built the Harvest Stage during that time.”

In Roulston’s opinion, the global pandemic isn’t the only factor making it harder for festivals like Blyth to survive - there’s also been a shift in the way people receive information that makes it harder to get the word out. “It’s more difficult for the Festival, because they don’t have people coming from the Signal-Star and the News-Record to write reviews anymore. We used to

give tickets away to all the editors of the papers, and they’d come and write reviews, so it’s a bigger challenge than ever for them to get an audience.”

Despite those challenges, this local legend isn’t worried about the future of Memorial Hall and the festival it houses. “To some extent, it’s magic, you know. What makes it work? The fact that it tells local stories about local people, for local people. That has always been a big part of it. It’s not like going to Stratford and seeing Shakespeare, or a reenactment of a play that was first done 500 years ago - these are plays that are happening today about people that you know, today. And part of it is that there’s something about Blyth - it’s a special place. We’re just happy to see our stories being told - the stories that needed to be told, but wouldn’t be told otherwise.”

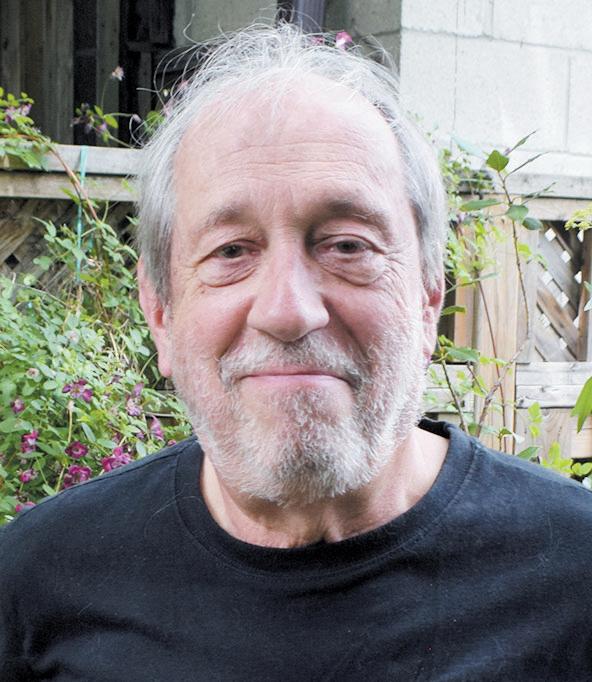

After training as an actor at York University and travelling throughout Europe, Clinton native James Roy co-founded the Blyth Festival in 1975

Roy’s decision to mount Mostly in Clover, an adaptation of the work of local author Harry J. Boyle, solidified the mandate to produce local stories. (Scott Stephenson photo)

By Scott Stephenson The Citizen

The first-ever artistic director of the Blyth Festival, James Roy, grew up on a farm in Huron County. His favourite childhood chore was cleaning the eggs produced by his family’s coterie of chickens. Once or twice a summer, the whole family would go swimming in Bayfield as a treat to beat the heat.

Roy was the Festival’s artistic director from 1975 to 1979. He may have consciously realized that he wanted to pursue theatre after seeing a production of Tennessee Williams' The Glass Menagerie when he was in the ninth grade, but the seeds of Roy’s theatrical career were actually sown years earlier, on the family farm. “My mother used to write what she’d call ‘skits’little playlets. And there was a local group, left over from the war, that had a tiny little community hall just up the road, and they would get together for a little Christmas celebration, and she would write these little skits, and my brother and I would inevitably perform, and it was always great to get an audience to laugh. And she was very funny, so we’d get lots of laughs.”

“I saw the first [performance of The Farm Show] purely by chance. I’d been in Europe for a year, having taken a year off from university. When I got back, my brother and my best friend said, ‘hey, there’s these guys doing a show out at Ray Bird’s farm... we rode our bikes out - out of town, out towards Goderich, and then up on the Maitland Line. I’d heard of Theatre Passe Muraille, because it had been mentioned a few times when I was doing my second year at York University.”

Not knowing what to expect made seeing The Farm Show for the first time even more impactful for the young thespian. “I ended up in the barn watching the show - I’d never heard of Paul Thompson, I didn’t know any of the actors, and we were surrounded by an audience who had been invited, mostly people who were portrayed in the play... so all these people were at The Farm Show , watching themselves be done by actors. And it was great!” Roy proceeded to see

The Farm Show several more times.

“I saw it two, three, four, five times - in cattle auction barns. I saw it at the Clinton auction barn, I think I saw it at the Brussels auction barn, I saw it I don’t know where. I don’t think I ever saw it in Toronto.”

Roy was in the unusual position of being able to see the show as both a member of the local farming community and an urban theatre student. As a farm boy, the show’s truth resonated with him. “I remember Janet Amos doing a scene where she’s standing in the ringer washer, which was the same as what my mother had in those days, she didn’t like the modern washers, they didn’t get clothes as clean.” As a young man with a head full of the most modern theatrical theory, he was energized by The Farm Show ’s bold originality.

“There was a real energy to it, because it was the original actors. They had a personal connection to

the material that any cast remounting a show just can’t have, particularly one where the original actors created it.”

Roy brought those two complementary personal perspectives together when he was tasked with planning the first year of programming for Blyth’s brand new theatre festival. He decided to take a big risk by producing a new play called Mostly in Clover , adapted from the writing of local author Harry J. Boyle. They also mounted a production of The Mousetrap - a popular Agatha Christie mystery.

After offering these two very different productions to the audience in Blyth, Roy observed that the crowds really responded to the locally-sourced material.

“Mostly in Clover was a big hit, two years in a row…. One of the actors, Ron Barry, who was in the original company, was so funny in Mostly in

Clover that literally, people were falling out of their seats. He’d get that kind of rolling laugh - it starts, it rolls, and then, no matter what you do, it just makes people laugh more. He had that ability to do just enough to keep it going.” That first show not only put the theatre on the map in terms of audience, it put the theatre on the map in terms of revenue.

Every artistic director of the Festival, past or present, will tell you that what has made the Blyth Festival so successful over the years is the deep connection between the local audience, the material presented on stage, and the theatre’s rural setting. And James Roy definitely believes in that concept, wholeheartedly. But Roy

also believes that there’s a logistical factor contributing to the Festival’s longevity. “One of the advantages that Memorial Hall had, and still has, is the number of seats. You can make a decent return on a show when you have 400-plus seats. When you have 100 seats, or even 200 seats, it’s just not the same. Being able to fill the seats for the second half of the first run of Mostly in Clover was phenomenal.” Of all the Blyth Festival plays Roy produced, one of his favourites is Patricia Mahoney’s This Foreign Land . “It was about the Dutch settlers that had come, and I remembered that, when I was growing up on a farm near Londesborough, we had young,

Continued from page A7

Dutch hired men. That was typicalthey would earn enough money to buy their own farm, and then they would bring over their families. And there are many, many successful farmers of Dutch origin in the area. What I really wanted to do at Blyth was sort of reflect all the aspects of the local culture, and when you sit down and think about it, there are more than you realize.”

This Foreign Land’s Blyth debut wasn’t just memorable because of its great script - it also featured future Stratford Festival star Seana McKenna. “Seana had just graduated from the National Theatre School... she had a choice to either be an intern at Stratford, or come to Blyth and become a company member.... It was the opening night of This Foreign Land, and we did not have previews

in those days, so it was the first show with an audience. At intermission, in the black-out, she misjudged the glow tape of the proscenium arch, and she went downstage rather than upstage.”

All the way at the back of the theatre, Roy heard a thud in the dark. “It was the unmistakable sound of a body hitting something. Let me tell you, it is unmistakable. When the lights came up, she had crawled back onto the stage, and she was standing up, stuck on stage, with her back to the audience. Very smart - less noticeable. A lot of people got up and never knew. I rushed around backstage, and by the time I got around, she was coming down, with blood pouring down the back of her head. We took her to the hospital, she got some stitches - she didn’t have a concussion. Or at least she wasn’t diagnosed with one at that time.

They’re better at diagnosing that now.”

The ever-professional McKenna shook it off and went back to work. “She was back on stage within a week. Well, we dropped two or three performances, and then we opened the next show of the season, and then we were back. So it was probably eight or nine days before she was back on stage. It was the beginning of the next week.”

Another highlight from his tenure as artistic director includes a musically-infused mounting of Lister Sinclair’s The Blood is Strong. “Scottish settlers - what’s better for Huron County? That one was done two years in a row - that one was very successful.” Roy also thoroughly enjoyed the hyper-local bent of The Blyth Memorial History Show, as well as Roulston’s first play - The Shortest Distance Between Two Points. “It was about

local people fighting big government - a theme that, sadly, has not gone away.”

Then there was I’ll Be Back Before Midnight, by Peter Colley. “That’s a play that’s still being done,” Roy pointed out. Colley’s spooky comedy is one of the most successful plays in the Festival’s history. “There’s a company in Poland that does it every year[Colley] actually got the idea from the place I was living in north of Blyth, in West Wawanosh. It suited me just fine, but he found it to be a little creepy.”

After their first season, Roy worked out a basic format for the Festival. “I developed the idea that we have four plays. I’d always make sure that there was something that should be an audience hit - like in my last year, it was I’ll Be Back Before Midnight. And that, of the four plays, we could, and we should, take a chance on at least one. I always programmed it last in the season, and it had the fewest performances. It was meant for all of us - the company and the

audience. I’m not talking about heavy drama, I’m talking about a serious play, with a serious theme. These were for the people who were looking for a bit more to bite off. So that, to a certain extent, has continued, in terms of the Blyth programming.”

Also after that first season, Roy had fully articulated the original artistic policy of the Blyth Festival. “The plays are chosen to reflect the culture of the area. That’s Blyth, but it’s also Huron County, it’s also Western Ontario, and you can keep going up, but the most successful plays are the ones that are local. It’s that same old thing about how the most successful art is specific, not general. Nobody writes a universal play. You need to find the small ‘c’ culture in your community, and think ‘what would the people that are living in this way - what stories do you think they might want to see on stage?’... you know what, I know a couple of writers, I’ll bet I could find somebody who would be interested in writing a play about

Continued from page A8 that. And that’s what Blyth has always done. It’s always commissioned more plays and put them on stage, probably, than any other theatre in Canada.”

Roy knew right away that the concept for the Blyth Festival was an innovative idea, but he soon realized that it’s also an ancient idea. “One of the reasons why I did Mostly in Clover was that I had

learned, in my theatre history class, that all the great theatre movements were all really local. The Greeks were local - how big was Athens? The Medieval and Renaissance plays were all town plays, done by the Guilds and aimed at the local audience. Shakespeare - extremely local. Even though he sometimes set plays in Verona, or wherever, he was really writing about London, and he was writing about the monarchy. He was writing about the people that he knew. It was all extremely local, and somehow, we seem to forget that.”

Roy pointed to Blyth’s 2009 production of Innocence Lost: A Play About Steven Truscott as one of the many examples of how that first artistic policy has continued to guide the Festival forward. “The Steven Truscott trial is hyper-local. Bless Eric Coates for putting that on, and particularly Bev Cooper, for writing it... it took 40 or 50 years before you could do a play about it, but it was a really, really good piece. It laid out the story in a way that most people locally, including me, didn’t know. Because you only get a certain amount

through local news. Well, now you get none. Almost noneexcept for The Blyth Citizen . I just had a conversation with Gil Garratt about the difficulty he has getting publicity anywhere else, in any paper, besides Blyth.”

Years of watching the people of Blyth watching plays in Blyth has helped Roy realize something“They’re one of the country’s most sophisticated theatre audiences... they’ve seen four plays a year for 50 years. At least, lots of those people have. Or they’ve seen two or three a year. But it adds up. When you see a lot of plays, you develop very good judgment. You don’t necessarily know the jargon, but you have a very good idea of what you liked about a play and what you didn’t like about a play, and why. But also, you’re happy to come back again, even if you didn’t like it.”

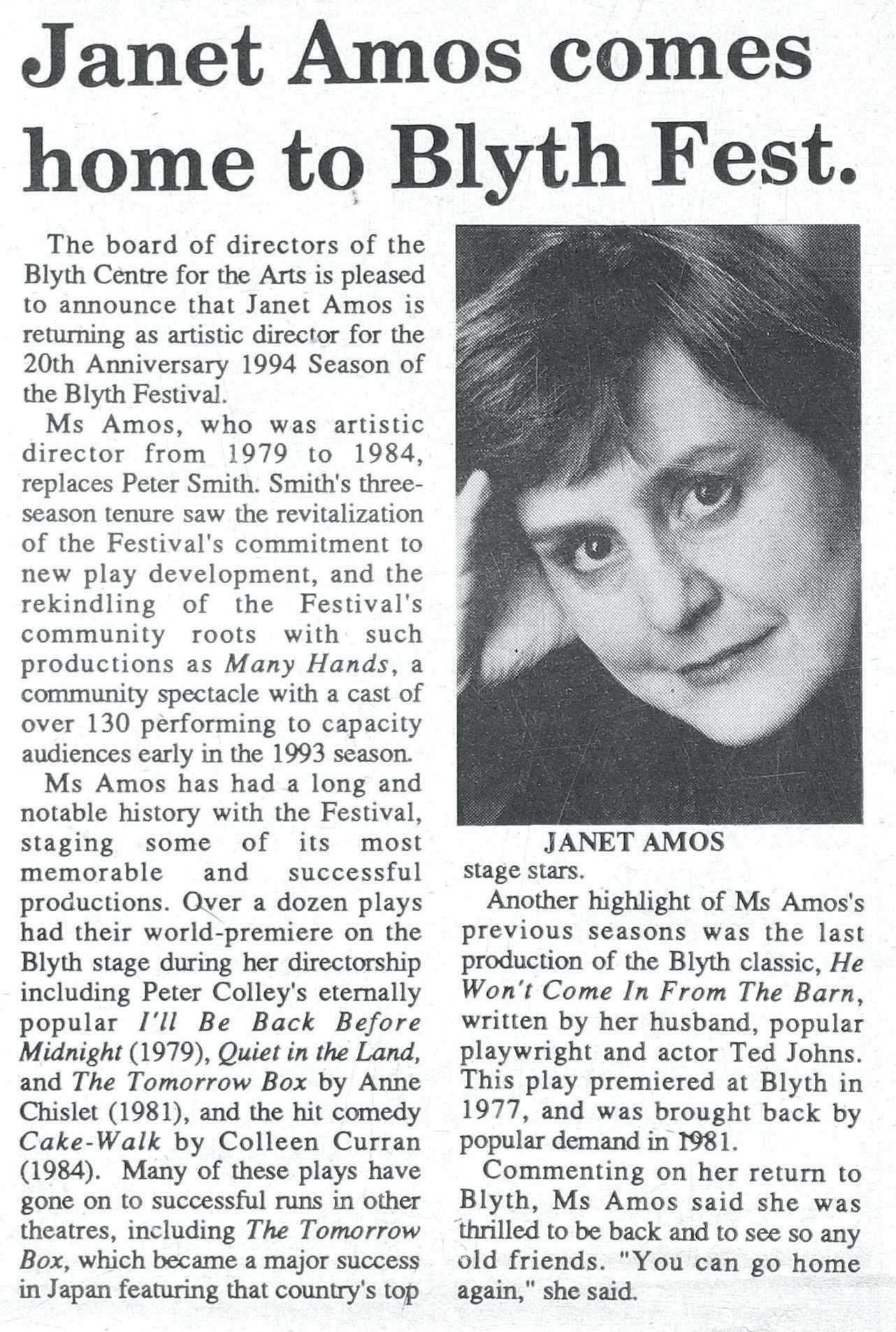

Canadian theatre legend Janet Amos set the Blyth Festival course from 1979-1984 and saved it a decade later

By Shawn Loughlin The Citizen

Janet Amos can be counted among the most successful artistic directors in Blyth Festival historyand you know that’s true because she did it twice. And it’s easy to understand her commitment to this area when it was Huron County that convinced her to remain in the world of theatre.

Her second stint at the helm of the Festival is credited as saving it,

pulling it back from the brink of closure after three seasons that lost audiences and money along similar lines. Her time as artistic director from 1994 to 1997 enabled the survival of the Festival, but in the early 1970s, she was simply an actor within Toronto’s Theatre

Passe Muraille who headed west to Huron County to embark on a crazy little project. That project became The Farm Show , and it would change Canadian theatre forever, but it also changed Amos forever.

Amos is from Toronto and was not overly familiar with Huron County when she came as part of the collective that would change the world of Canadian theatre. However, this was at a time when Amos was considering quitting theatre. She said it felt as though she was unemployed half of the time and wasn’t loving some of the work she was doing in the other half of her time.

Being on those farms and meeting the people of Huron

County completely reinvigorated her love for the theatre and set the course for the decades that were to come. She and the cast returned to the area shortly after creating the show and performing it for the very first time near Clinton in Ray Bird’s barn. They were touring with The Farm Show and playing very small communities and unusual venuesone particular tour that comes to top of mind for Amos was the Crystal Palace of Brussels - which included Blyth and its ailing Memorial Hall. Amos and the gang returned to Toronto, however, and in the meantime, Keith Roulston, Anne Chislett and James Roy founded what was called, at the time, the Blyth Summer Festival, producing its first season in 1975.

It wasn’t until the second season that Amos saw a show at the Festival and said she immediately admired what the Festival was doing - telling Canadian stories at a time when few theatres in the country were.

It was the next season that began Amos’ involvement with the Festival when founder and thenArtistic Director James Roy came calling in hopes that Amos would perform in one of the Festival’s shows as part of its third season in 1977. A very pregnant Amos had to decline, but considered, and eventually accepted, a second offer to direct The Blyth Memorial History Show , written by Jim Schaefer. Amos had

already directed at Theatre Passe Muraille, but she still considered herself a “baby director” at the time.

Amos even had her concerns about directing the show, but she consulted with her mother, who insisted that children know to come at times that are convenient for their mothers. True to this proclamation, The Blyth Memorial History Show opened and Amos was in the hospital the next day welcoming a very punctual, understanding and theatre-conscious child into the world. The staff even fashioned its own “It’s a Boy” signs for Amos upon her return to Blyth.

As for the show, Amos was committed to her work in Blyth from the beginning. Schaefer’s work was heavily improvisational and Amos insisted on bringing another theatre legend, Layne Coleman, on to help. He was busy in Saskatchewan with Paul Thompson and the Festival didn’t have the money to fly him to Blyth. Amos insisted that she needed Coleman, so she paid for his flight out of her own pocket and the show

Continued from page A11 was a success, although Amos admits it felt “scrabbly” at the time.

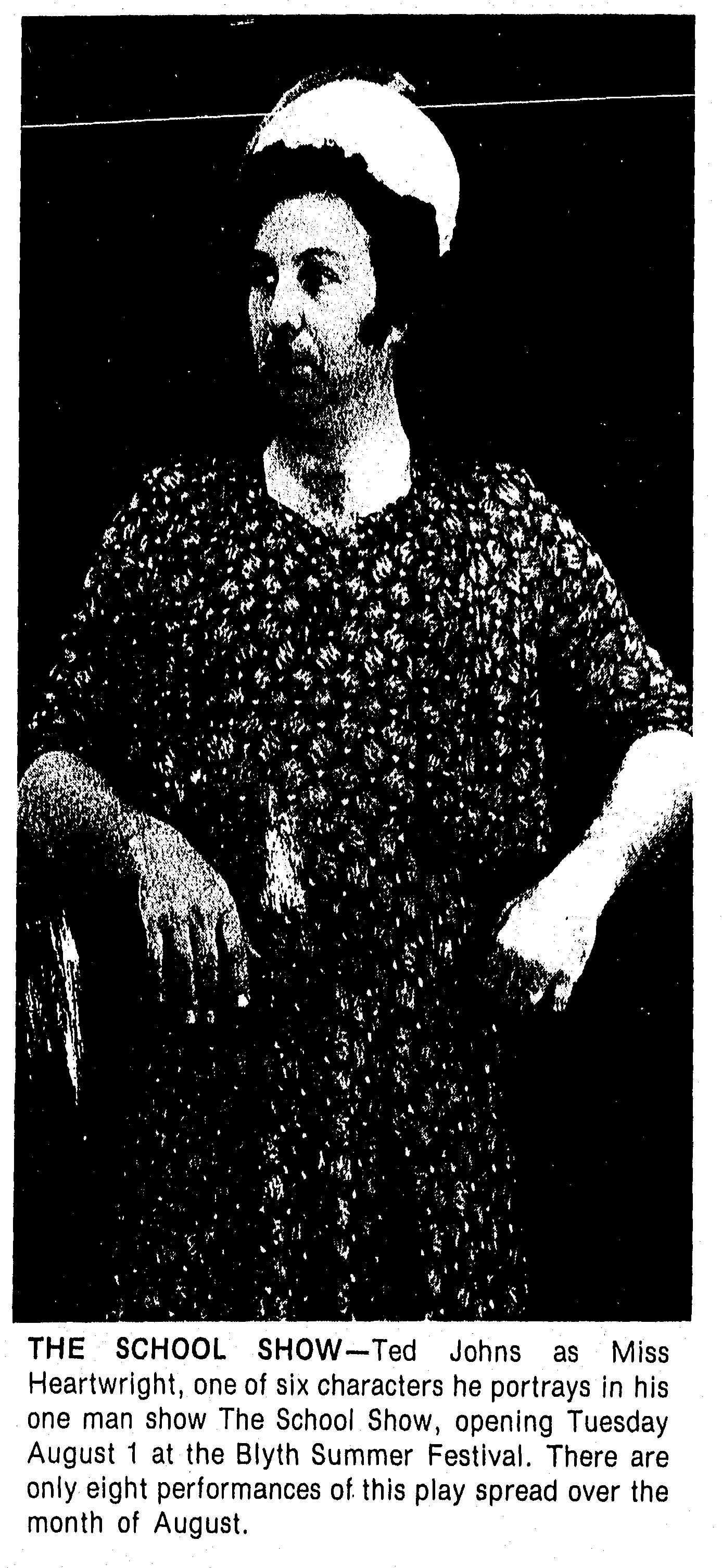

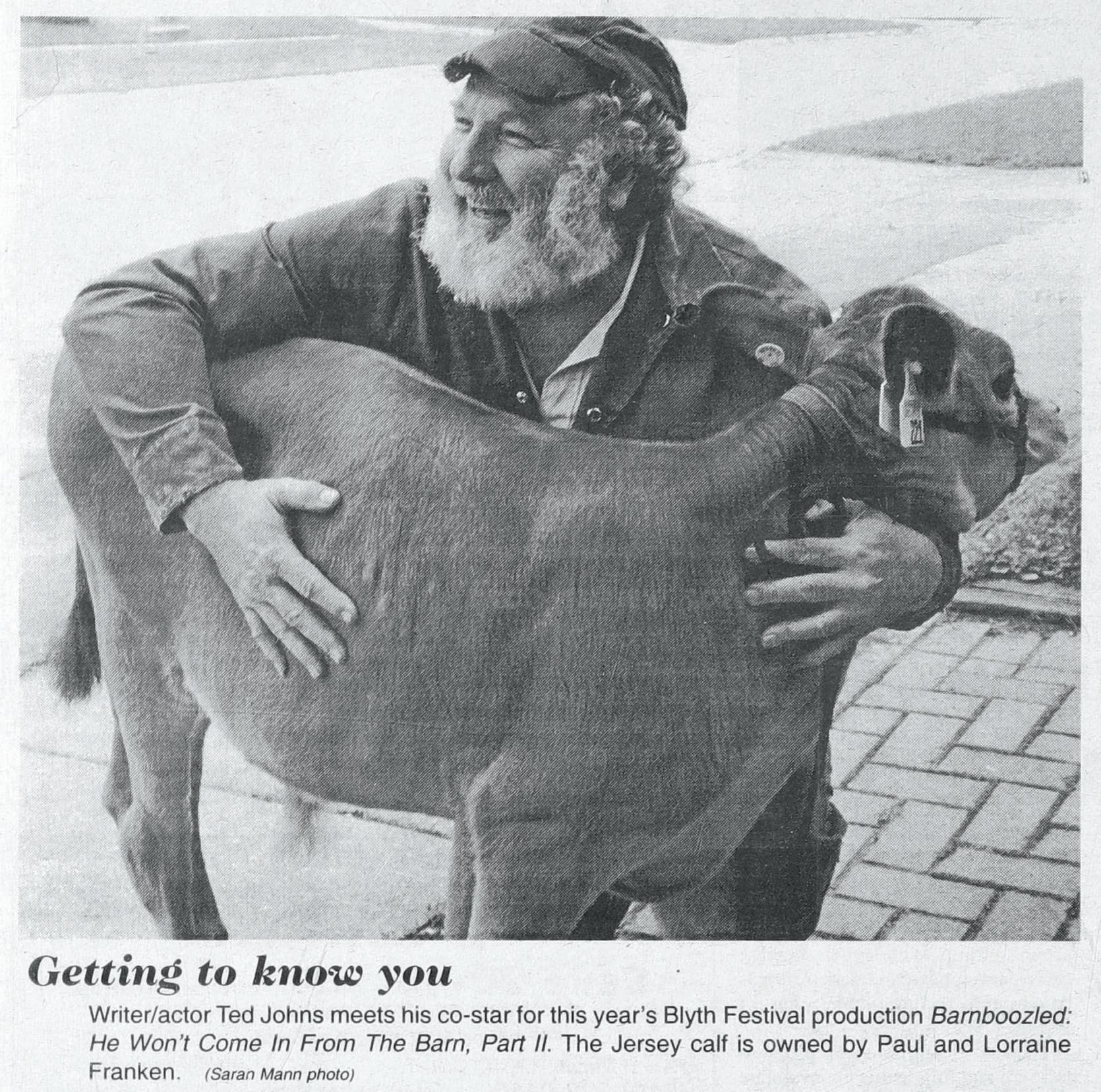

As part of the 1978 season, Amos’ husband and one of the country’s most prolific playwrights and actors, Ted Johns, created The School Show for the Festival on a very aggressive timeline. They had young children at the time and Amos was working at both the Shaw Festival and acting in television, but, as she says, when you’re in a creative field, you can’t turn down work.

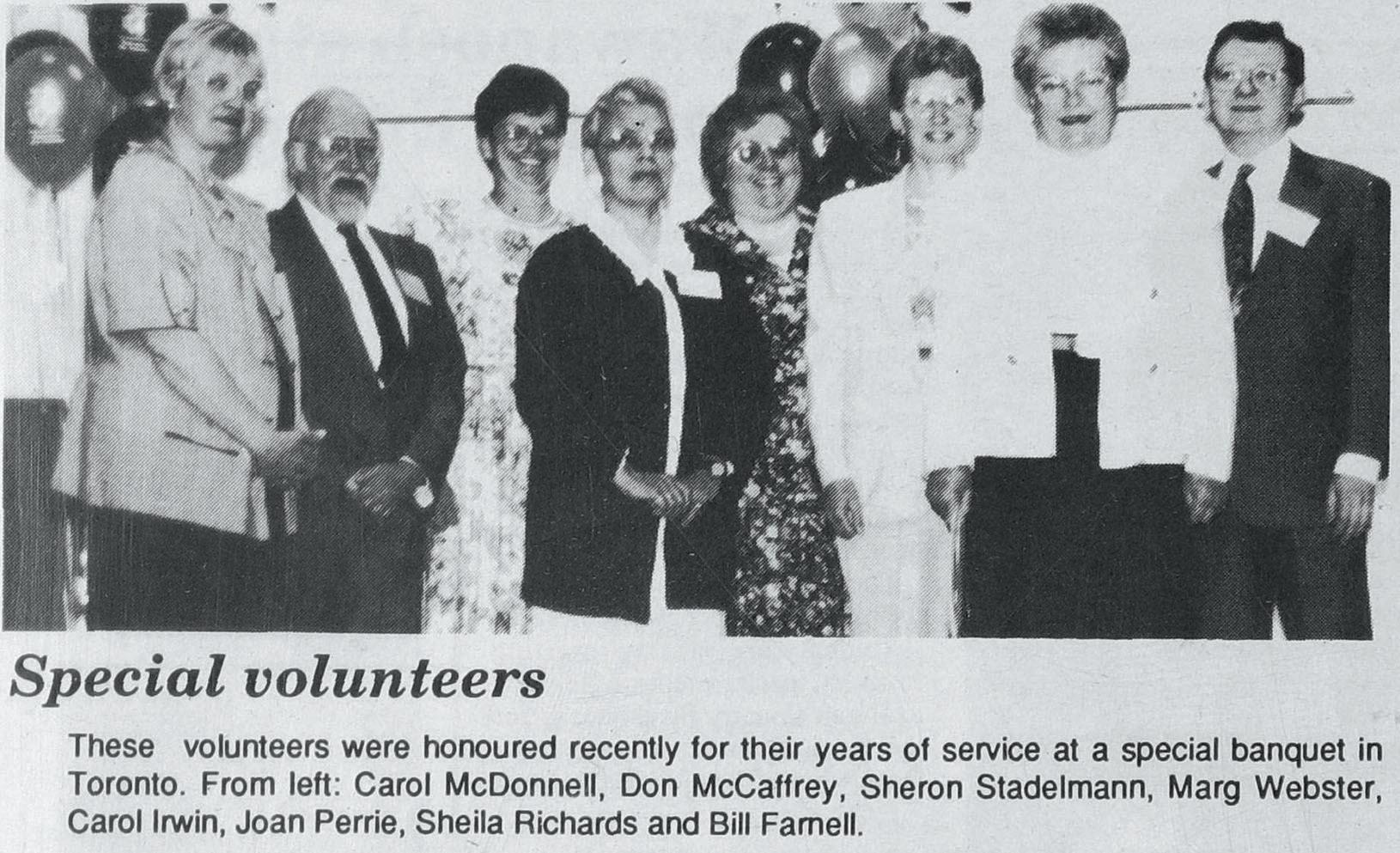

It was then that Amos was encouraged by both Chislett and Roy to apply to be the next artistic director of the Blyth Festival. Because she was so busy, she almost missed the cut-off to apply and eventually did so by way of a handwritten letter. She was among five or so people who were interviewed and it was dedicated theatre volunteer Sheila Richards who informed Amos that she was the successful candidate and that her support was unanimous.

Years later, Amos laughs, she found out that was not the case and that her hiring caused somewhat of a controversy, as she was chosen over some candidates with more experience. Amos opined that it was Johns’ success that helped get her the job, but, in the end, Roy and Chislett had tremendous faith in her ability to do the job and lobbied hard for her to fill it.

She worked that first season, 1979, as the associate artistic director so she could learn the ropes and understand what it takes to be in the position.

Among her first challenges was learning how to do the books and the financial side of running a theatre, which she says has served her well over the years - not many artistic directors are well versed in the financial and practical sides of things and she had that foundation.

Humbly, she says she was tremendously lucky and surrounded with hard-working, talented people as she took over the reins of the Festival, but, between 1979 and 1984, the Festival found great success, producing some of its biggest and most revered shows.

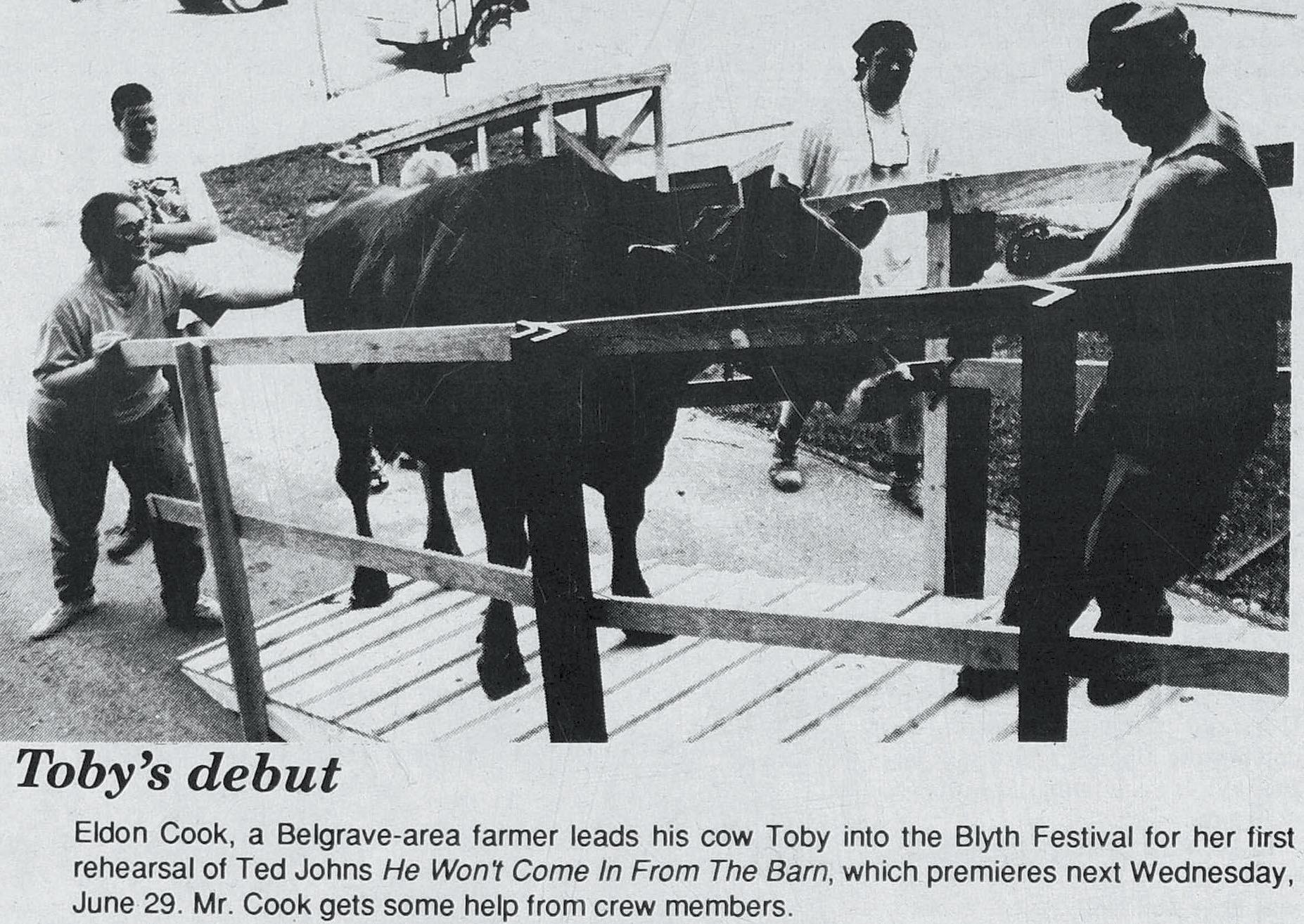

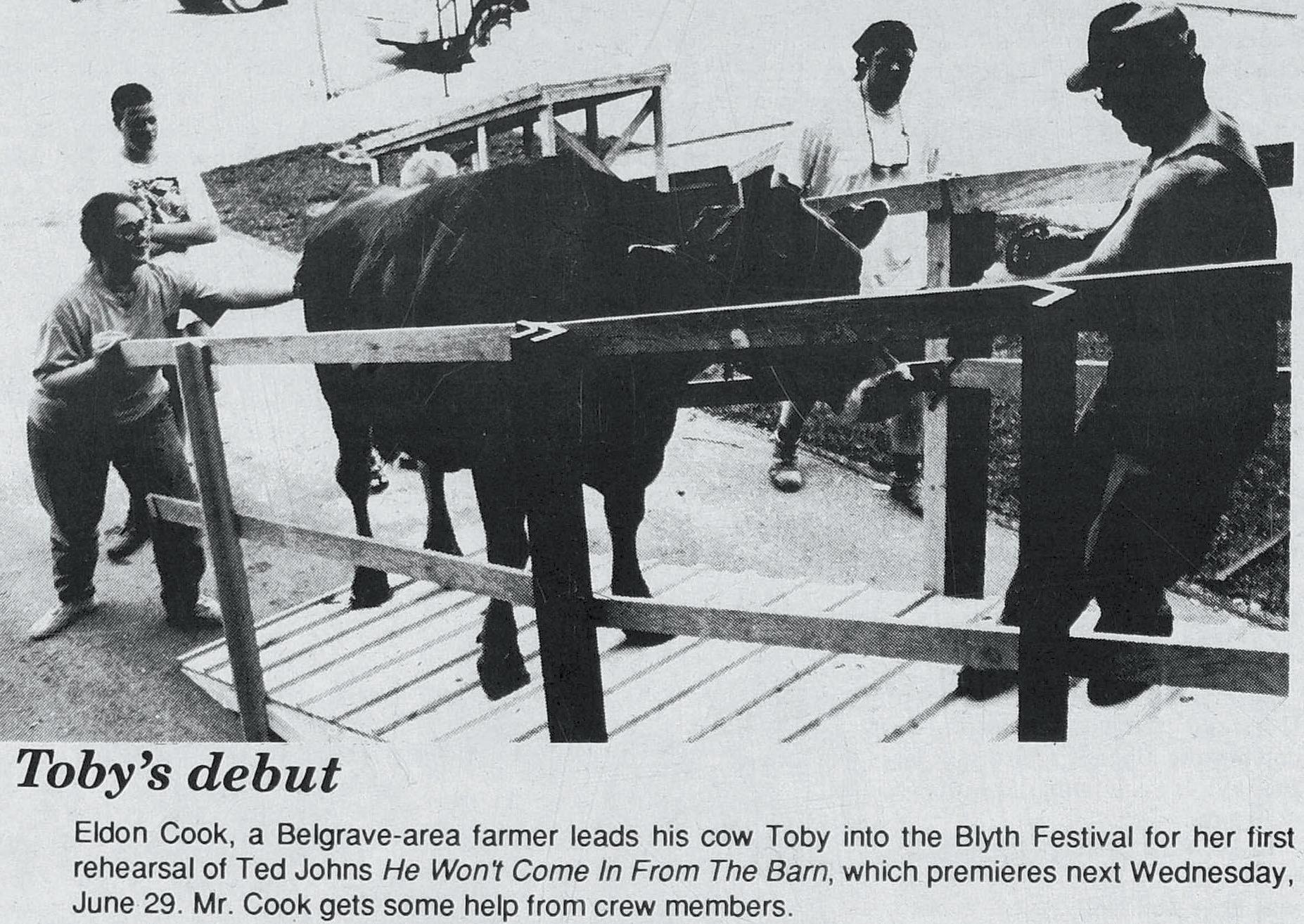

Peter Colley’s I’ll Be Back Before Midnight came in 1979, followed by John and the Missus by Gordon Pinsent in 1980 and Quiet in the Land, Tomorrow Box and He Won’t Come in From the Barn in 1981. In 1982, Amos then wrote Down North and Johns and John Roby wrote Country Hearts

Things at the Festival were booming at that time. People were lined up around the building to buy tickets to shows, productions were often held over and audiences were finding their way to the Blyth Festival. Though, in her final two seasons, Amos was also directing and acting in many of the shows, all while juggling a young family and running the theatre. Soon, it became a bit too much and Amos says she was run off her feet with the work, saying she was simply “too tired” for the job.

She eventually handed over the keys to the kingdom to Katherine Kaszas, who would serve as the artistic director from 1985 to 1991. Meanwhile, Amos headed east and

serve as the artistic director of Theatre New Brunswick from 1984 to 1988.

The large touring theatre was busy, but different than the Blyth Festival and Amos said the move was hard on Johns and the older of their two children. The theatre wasn’t really producing the kinds of plays that Johns would write, but

Amos said it was a good job.

Then, 10 years after she had bid farewell to the Festival, she returned to a very different situation than the one she left behind.

Kaszas had grown the Festival

the community and its residents. Despite not growing up in a small community, Kaszas says she didn’t feel an aspect of culture shock

Katherine Kaszas brought in some of the Festival’s most successful plays ever and expanded Memorial Hall to what it is today 1988

By Shawn Loughlin

When it came time for Janet Amos to pass the artistic director baton in the mid-1980s after a tremendously successful six-season stint, she turned to Katherine Kaszas, who was still in her 20s at the time, to continue growing the Blyth Festival. And grow it she did.

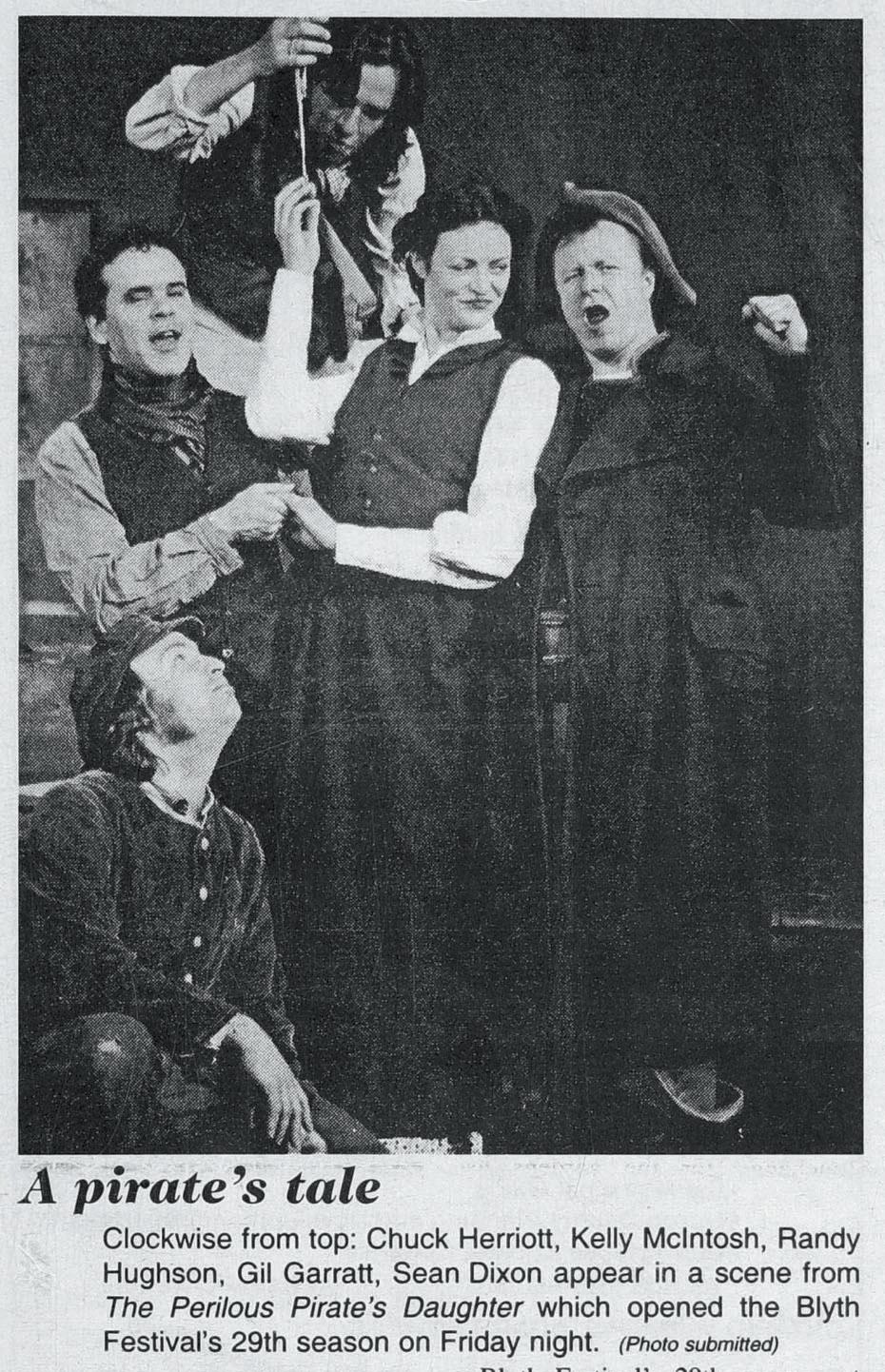

Kaszas took over in the Blyth Festival’s top position and brought forth a five-show season in 1985. It opened with Brian Wade’s Polderland , Moose Country by Colleen Curran, Beaux Gestes and Beautiful Deeds by Marie-Lynn Hammond, Ted Galay’s Primrose School District 109 and Garrison’s Garage by Ted Johns.

The Festival was in good shape thanks to the hard work of cofounder James Roy, who got it off the ground as the artistic director from 1975-1979, and Amos, who had ushered in a new era that includes some of the Festival’s most successful productions, like Anne Chislett’s Quiet in the Land, Ted Johns’ He Won’t Come in From the Barn and Peter Colley’s I’ll Be Back Before Midnight Kaszas had met Amos when she was directing a show at Theatre Passe Muraille and Kaszas said she begged Amos for an opportunity at the Blyth Festival, admiring the work that was being done there, and Amos relented and a very young Kaszas was the Festival’s newest stage manager.

Kaszas, an Ottawa native, came of age in the world of theatre at a time of great change in Canada. The Blyth Festival and some of the landmark Toronto theatres like Theatre Passe Muraille, and the Factory and Tarragon Theatre were just getting their feet under them and the work they were doing, telling Canadian stories in Canadian theatres, was regarded as pretty radical for the time, Kaszas says. It’s hard to overstate, she said, the impact of something like The Farm Show on theatre students at the time. She was immediately intrigued with the changing

Miles Potter and Layne Coleman.

Having the support and confidence of both Amos and Johns was a big boost, Kaszas said, so she got to work. She did so with the help of a lot of amazing people, she said, which is something that is so special about the Blyth Festival. Kaszas says that the people who work for the Festival are so committed to the mandate of the Festival that it’s magical.

Further to that buy-in is that of the community, Kaszas says, which is really what sets the Festival apart. The community has adopted the Festival as its own, welcoming and supporting itbut that’s because the Festival is telling the stories of the community and its people, so it’s really a circular relationship between the Festival and its artists and

when she began working at the Festival and later became its artistic director. She said the community

Continued on page

1987

landscape of Canadian theatre and wanted to be part of it.

For her first season at the Blyth Festival, Kaszas was the stage manager for the 1980 productions of St. Sam of the Nuke Pile and The House That Jack Built. She would be back again, but then take a few seasons off, not wanting to be pigeonholed as a stage manager, but wanting to direct her own shows.

She would return and serve as an assistant director on some shows and then, when the time came for Amos to move on from the Blyth Festival and take on the role of artistic director at Theatre New Brunswick, Amos asked Kaszas if she’d be interested in applying for her old job.

She was, so she did and Kaszas was chosen to be the third artistic director in the Blyth Festival’s history. Kaszas said she had had tremendous mentorship from not only Amos, but directors she greatly admired, like

Explore this year’s inventory of potted trees and larger trees in wire baskets.

Designing, Planting and Tree Spading

Tim & Christine Diebel

Phone 519-291-4754

Fax 519-291-3968

Email tdiebel@outbacktreefarm.com

5290 Line 86, R.R. #3 Listowel, ON N4W 3G8 www.outbacktreefarm.com

in Toronto and as a dramaturge at the Banff Centre for the Arts, all while freelancing within the Canadian theatre world.

is always a care and attention, in a community sense, that goes into producing work for the Blyth Festival that is unique.

For our interview, Kaszas carved time out of a busy trip to FaceTime from London, England on a trip to see her daughter, who had just had a baby of her own. Kaszas said she was happy to do it and that she adores the Blyth Festival and the community. That commitment has meant so much over the years and the Festival is lucky to count Kaszas as not just one of the architects of its success along its 50-year journey, but as one of its most dedicated supporters now.

Continued from page A12 adopting her, in a way, was a big part of the circular relationship that she so admires about the Festival and she still has a tremendous spot in her heart for Blyth and the Blyth Festival.

After her first season, she mounted what would become one of the Festival’s greatest successes, penned by two of its incredibly talented founders. Another Season’s Promise, written by Keith Roulston and Anne Chislett, opened the 1986 season, which continued with Drift by Rex Deverell, Gone to Glory by Suzanne Finlay, Lilly, Alta by Kenneth Dybat and Cake-Walk by Colleen Curran.

Another Season’s Promise would return the following season, be produced internationally and spawn a sequel in 2006, Another Season’s Harvest by Roulston and Chislett once again. Notably, for Kaszas, Another Season’s Promise played an integral role in the Festival’s touring productions, which were really taking off at the time. The touring productions served as highquality advertisements for the Blyth Festival that would show up at your door in towns across southwestern Ontario and beyond. She said they worked wonders in terms of bringing audiences to Blyth.

However, when the Drayton Festival Theatre opened in Grand Bend in the early 1990s, its presence put a bit of a stop on things, as the communities that were being served by the Festival’s touring productions were now being served by the Grand Bend theatre, so those audiences began to dry up. Kaszas did note that the Blyth/Grand Bend baseball rivalry, however, did not dry up, and she remembers Blyth on the winning end of many of their fun interindustry games.

In fact, she’s sure that it was one of those games that induced labour with one of her two children who were born during her time at the Blyth Festival. She also remembered that there was a British actress in the company for one of the games and, at her time at bat, she struck the ball into the field of play. However, being British and not overly familiar with baseball, her cricket mind clicked on and she ran to the pitcher’s mound.

The Blyth Festival crew busted into uproarious laughter and Kaszas soon felt it was time to head to a local hospital. The Festival staff greeted her appropriately upon her return - celebrating her new baby and welcoming her back to the job. After five years as the artistic director, growing the audience in ways the founders could only have dreamed about back in those early days, Kaszas felt it was time to

move on. Five years was enough.

Amos had grown the Festival to bring in audiences that would have been unimaginable in those first few seasons and, by the time Kaszas was nearing the end of her time with the Festival, nearly 45,000 people were coming to Blyth for the Festival every seasonattendance level heights that are the envy of many.

Furthermore, Kaszas arguably managed the most substantial expansion of the Festival and Memorial Hall in its history. Thanks in part to a rare federal and provincial government funding opportunity, the Festival’s old garage was renovated and carpentry, paint, costume and prop shops were all built. The former CIBC bank branch was converted into offices, the box office link (including the Bainton Gallery - the home of the Blyth Festival Art Gallery) was constructed and the June Hill rehearsal room and large loading dock were all constructed. These major improvements created the earliest version of the Memorial Hall we all now know and love.

The cost was approximately $2 million dollars and it was only finally paid off within the last 11 years. However, at that time, the Festival had grown and with it, its budget had grown to more than $1.5 million - again, something that would have been unthinkable in those early seasons of the Festival.

After leaving the Blyth Festival, Kaszas served as the associate artistic director of Canadian Stage

In her later years, however, she found a real passion ignited within her when she began to teach on a full-time basis. She taught at both the University of Toronto and Sheridan Music Theatre before heading west to Windsor’s St. Clair College in 2004.

In her time at St. Clair College, she launched both the Music Theatre Performance and Entertainment Technology programs and directed a number of productions. She just recently retired from the position of artistic director of the college’s music theatre programs. In fact, during our interview, Kaszas boasted that Ryan Brink, the Festival’s current hard-working production manager, is one of her graduates.

She continues to be passionate about and invested in the work being done at the Blyth Festival to this day, returning to Huron County when she can to take in productions and that’s because she is in awe of the Festival and its unwavering dedication to its mandate. It is still telling the stories of its region - just as founders James Roy, Anne Chislett and Keith Roulston intended - and that mission has never changed over the course of the last 50 years.

When discussing the rise of Canadian theatre in the 1970s, Kaszas said that each of the theatres doing “radical” work at the time all had their own identity. The Tarragon Theatre, for example, had a truly individual method of telling singular stories, while the Factory

Theatre would be better characterized as a gritty, confrontational style of theatre in those early days. Some theatres were producing very well-written, composed plays, while Paul Thompson and Theatre Passe Muraille were staging collective creations that could change from performance to performance and were much more comfortable with improvisation.

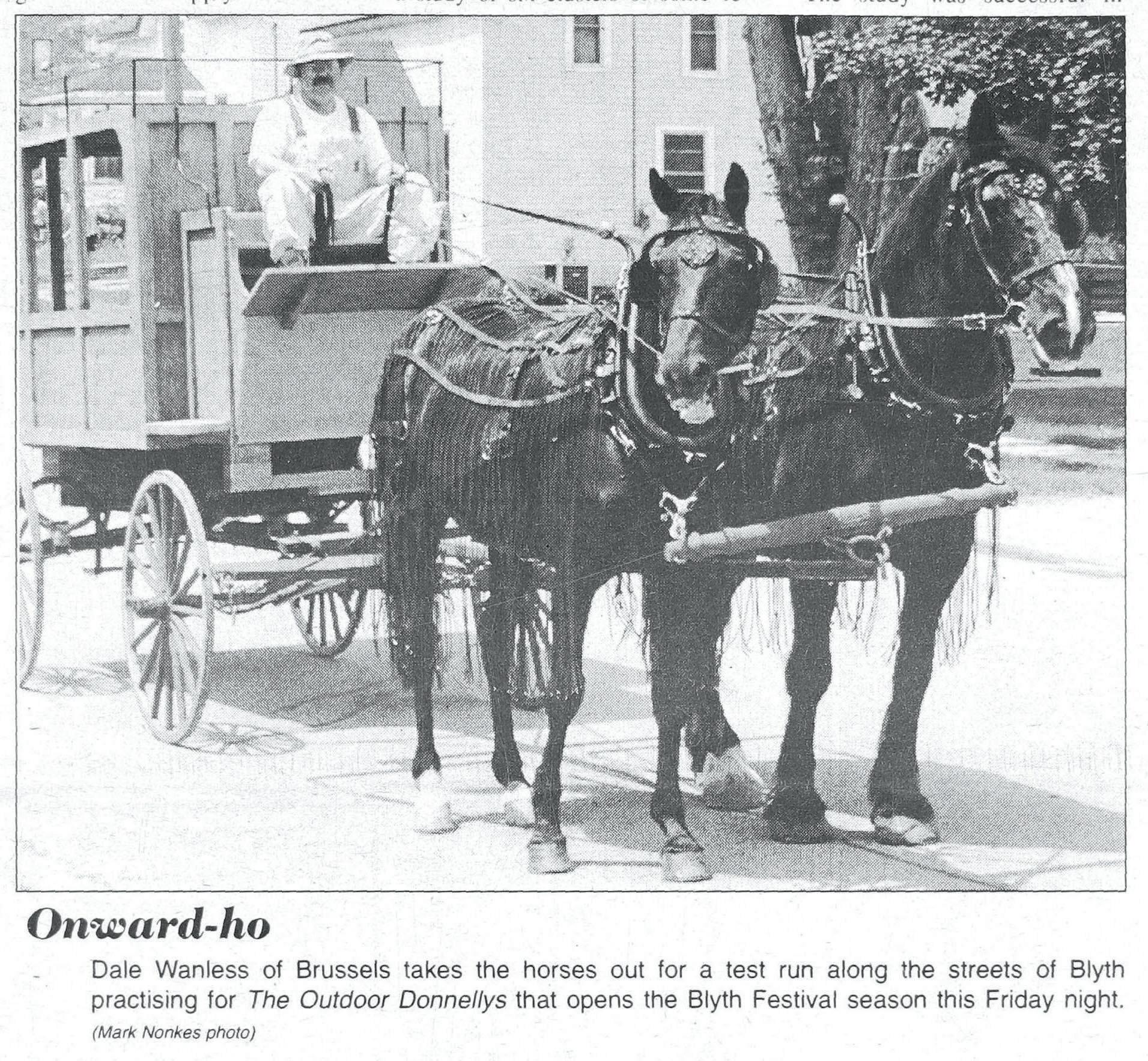

In terms of the Blyth Festival, Kaszas says that from the early days of the Festival right up until today, a Blyth Festival show has a specific feel that cannot be replicated. She said you can look at the sweeping scope of work produced at the Blyth Festival over its 50 years, from massive outdoor spectacles like The Outdoor Donnellys to subtle masterpieces like Quiet in the Land and Another Season’s Promise and, despite their drastic differences, know that they are both Blyth Festival productions. It goes back to that commitment to community and its relationship with the village, she said, and there

Peter Smith oversaw some of the most challenging years at the Blyth Festival

In the early 1990s, Peter Smith was at the helm of the Blyth Festival, taking creative chances and dreaming big.

By Scott Stephenson The Citizen

In the barnyard of Blyth Festival artistic directors, there are some who would consider Peter Smith to be a bit of a dark horse, while there are others who might call him a black sheep. From 1991 to 1993, Smith used his time in the artistic director’s chair to take a lot of big risks, programming-wise. While not all of those risks paid off, ultimately, Smith feels grateful for the whole experience.

Originally hailing from Halifax, Smith was working at a theatre in Winnipeg when he first became involved with the Blyth Festival, at the behest of Katherine Kaszas.

“We were having a good time, and then she said ‘you should come to Blyth’. And I said ‘OK - I don’t know where that is.’” After that first visit to Blyth, Smith headed back east and began developing the wellrounded résumé that eventually led him back to Blyth. “I started up with directing, and then artistic directing, dramaturgy and producing - learning about a bunch of different aspects of the forum, of the arena…. You never know when you’re going to walk into a learning experience. Often, the best learning experience is the one that humbles you, I’ve found.”

The siren song that drew Smith back to Blyth was the Festival’s dedication to producing new work. “I just couldn’t get enough of new work,” he admitted. “Really, a director is the first audience of a new play. That’s a position that I came to love and appreciate. Witnessing something coming to life for the first time, and then 25 pages get cut, and you’ve got a new ending and all those things, it’s like being in a creative cauldron... So that was probably the beginning. As I said, there were many humbling experiences along the way.”

Kaszas eventually asked Smith to be the Festival’s associate artistic director. “It meant you read the

Of course, it wasn’t all negative reviews that were shared in the grocery store aisles. “Other times, people would come up, and just stand there, and they’d go ‘that was pretty good.’ And I just came to appreciate that contact with the audience that you just don’t get in a lot of theatres. I’ve worked coast to coast to coast - Blyth is a very special place in that regard. It’s the connection to the community.”

One of Smith’s favourite productions from his time at Blyth wasn’t a huge hit with everyone in the audience, but it certainly had its fair share of fans. “In the first season that I was artistic director, I performed in The End of the World Romance by Sean Dixon.” Smith’s wife, actor Laurel Paetz, was also in the show. “It was a fascinating piece of poetry-prose. For some people, it was just such an electric experience in the theatre. It really was. But there were also people that were like ‘this isn’t a Blyth play, it’s too odd, it’s too peculiar.’ But looking back, I’m really glad that we did it - it’s a beautiful piece of writing.”

hundreds of plays that people have submitted. That was another real education - reading play after play after play.” Driven on by his curiosity, Smith kept putting one foot in front of the other, and soon found himself in the role of artistic director.

Something he learned early on was that the Blyth audience is always willing to engage in a bit of open communication.

“Scrimgeour’s used to be the grocery store, and you’d go in there after an opening night, or even after a preview, and people would come up and stand beside you, and they sometimes wouldn’t say anything, and I’d think ‘this is awkward’, and I’d nod,” Smith explained. “And then they would say ‘Well, you kind of missed the mark there last night,’ and then they’d just walk away.”

Another one of Smith’s most memorable contributions to the pantheon of Blyth Festival plays was 1993’s Many Hands. “There were like 200 people in it! There was a parade every night through the Village of Blyth - there was music, and stories. And it’s the story of a place, told by the people of the place. There were kids, and adults, and bankers, and people from the pharmacy, and farmers - it was nuts. It was a crazy large event that 400 people saw every night. They followed behind this parade, and there were scenes on lawns, and graveyards and in trees, and on rooftops, and then we ended up at the rutabaga plant.”

One of the shows that had the biggest impact on Smith during his time working at Blyth was Another Season’s Promise , written by Festival founders Keith Roulston and Anne Chislett. “It was a seminal moment for me. There was just a whole lot going on. There were the farm survivalists with the red arm bands, the penny auctions were happening - this was all in our lifetime. This wasn’t some distant, Okie from Muskokee kind of thing. This was going on. It was a

Continued on page A15

Our portable sanitation units come in standard, luxurious comfort and deluxe models for your special event. Contact us and we can help you determine your portable sanitation requirements.

Phone: 519-368-5529 • 1-888-805-6481

Fax: 519-368-7817 • email: bws@bmts.com website: www.bluewatersanitation.com

Continued from page A14 powerful story that was about them, but it actually traveled. It could have been told anywhere.”

Smith counts himself lucky to have been at the show's opening night. “You could hear a pin drop. Araby Lockhart and the late, great, David Fox played the heads of the family, and David’s character came to the realization that his farm was actually going under. Many generations, and all that let-down, and the weight on his shoulders... you couldn’t have had art being any closer to an audience than that. It was a moment when the art, the creativity, and the audience were one.”

Looking back at his time in Blyth, Smith has come to accept that all the ups and downs were all just part of the same big ride. “It was like one big season. It was a blur. And now, where I’m at is mostly letting go. And I think that would have been good to have in

turkeys. As a stage manager once said to me, ‘you put just as much energy into an eagle as you do a turkey’. It doesn’t matter, you just keep pouring it on.”

After his first run, Smith returned to the helm of the festival one more time as interim artistic director in 2013, following the departure of Eric Coates. Smith had his work cut out for him that season, but he didn’t let it get him down. “It was fun. It was really a lot of fun. The season was fun, and it was great to be back. And really, what came out of it was fixing the leaky roof and the new seats. And Project 1419 was born, which was another community event I did not plan for, and was not even interested in participating in, but it started in that interim year because we needed to replace the seats and fix the roof. That interim year was really transformative for me - I was back working with the company, bringing people together. It was an

working as the creative director for the Canadian Centre for Rural Creativity, Smith often feels the inexorable pull of the Blyth Festival and its steady stream of new plays designed to entertain a local audience. “It’s like the ebb and flow of the tides,” he explained. “All this new work - it’s another season’s promise. You put the seeds in, you hope for the best, you hope for more sunshine and rain, and financing, and then it goes up, then it’s all of a sudden over.”

Being the artistic director of the Festival was certainly a wild ride for Peter Smith and the audience in Blyth, but he's happy to have shared that experience with them. “There were some dogs, and there were some goofy experiences, and all the rest of it. But there were those moments when art, story, community came together. In Blyth, there’s always the possibility of that - it doesn’t always happen, but the possibility of that happening

When the Blyth Festival struggled to pay its bills amid mounting challenges, it turned to a familiar face

The Festival amassed tremendous debt at this time and was borrowing from local businesses, families and even the county. Amos said the Festival didn’t have a line of credit at the time, so it was debt, rather

than a deficit - an important, and more severe, distinction. In a speech she gave for the Festival’s 40th anniversary, Amos said the Festival amassed operating deficits

Continued on page A17

However, when Peter Smith took the torch from Kaszas, the annual offering swelled, along with costs, and the audiences shrunk. Amos

Continued from page A11 substantially and shepherded it throughout some of its most successful years, producing hits like Another Season’s Promise by Roulston and Chislett in 1986, John Roby and Raymond Storey’s Girls in the Gang , Kelly Rebar’s Bordertown Café in 1987, Robert Clinton’s The Mail Order Bride in 1988 and Dan Needles’ The Perils of Persephone in 1989.

estimates that, at her height, Kaszas was drawing in excess of 42,000 patrons per season. Compare that to the 17,000 or so who were attending shows in the early 1990s when Smith was producing six shows per season, as opposed to the traditional four.

Continued from page A16 of over $200,000 for two straight years, in addition to the building debt of $350,000.

“By 1993, the theatre was broke. Bills could not be paid. The Canada Council and Ontario Arts Council funding was in jeopardy,” she recalled in that speech.

She said that returning to the Festival during that time, was “hell” but she so loved the Festival that she knew she wanted to do whatever it took to help turn things around and make it successful.

Tough decisions had to be made upon her arrival. The 1994 season was scaled back tremendously after the Festival’s board of directors chose not to renew Smith’s contract. Amos said she cut the budget in half and had to terminate a number of hard-working people who didn’t deserve to be let go, but that the Festival was in survival mode and difficult decisions had to be made.

Those who were left, she said, worked like dogs. They worked nights, weekends and more for little pay, but they were motivated to save the Festival from ruin.

Those early months, she said, were the product of a staff and a board of directors that were willing to pull up their sleeves and work for the Festival, doing whatever was in their power to pull the Festival from the brink of disaster.

Board members like Marian Doucette and Duncan McGregor deserved a lot of credit, as does the rest of the board, she said, while top-of-the-line fundraisers like Sheila Richards, Betty Battye and Lynda McGregor (then Lentz) were pulling in money from wherever they could find it, all to benefit the Festival.

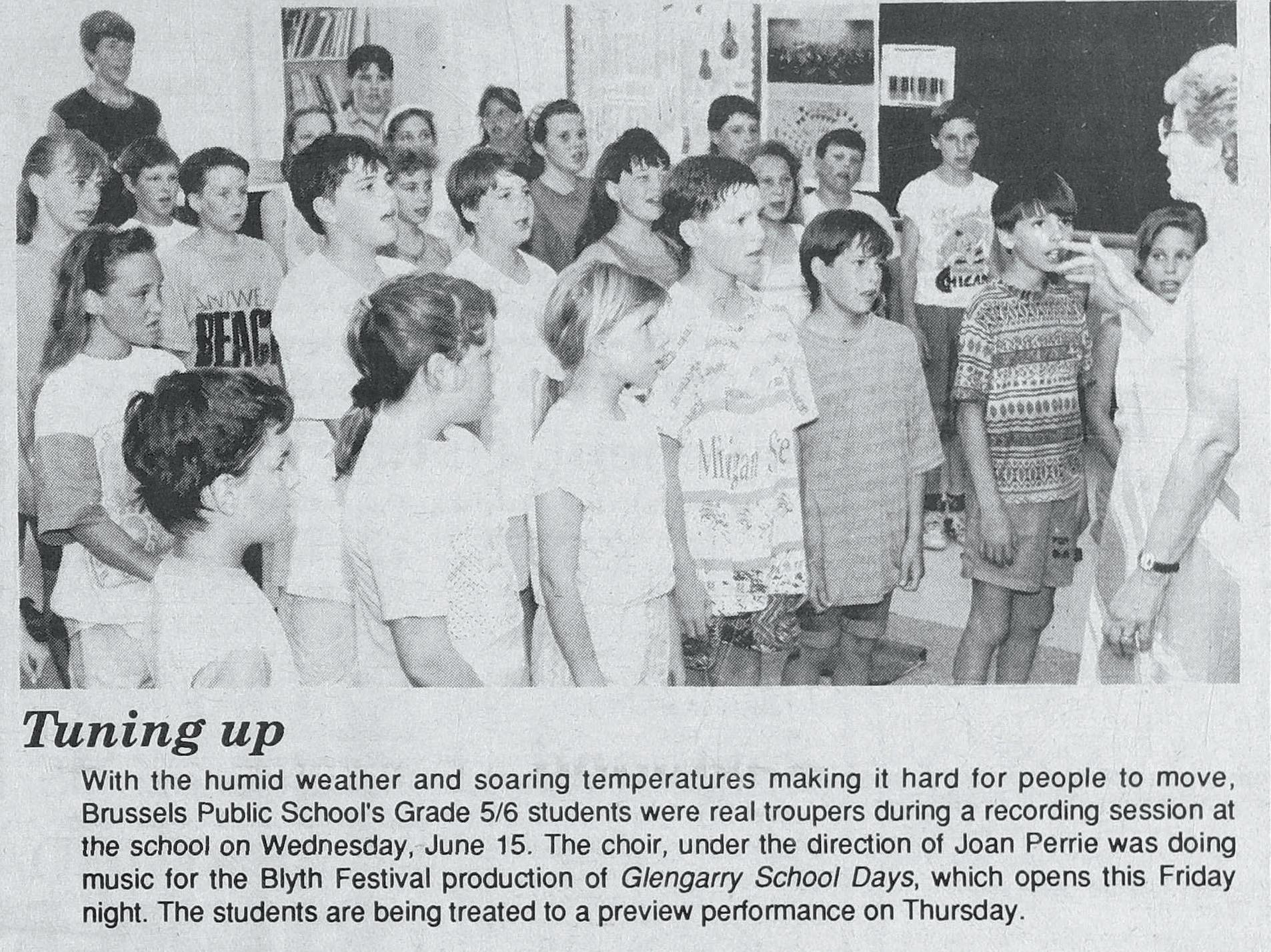

Amos opened the 1994 season with Glengarry School Days by Chislett and brought Johns in to revisit his beloved He Won’t Come in From the Barn, which would eventually be held over that season. Selling out that He Won’t Come in From the Barn run, Amos said, helped to provide cash flow for the Festival - bills could be paid and the organization had money in the bank again.

In the seasons that followed, Amos returned to some time-

honoured pieces that she knew had connected with Blyth Festival audiences in the past in the hopes that they might once again.

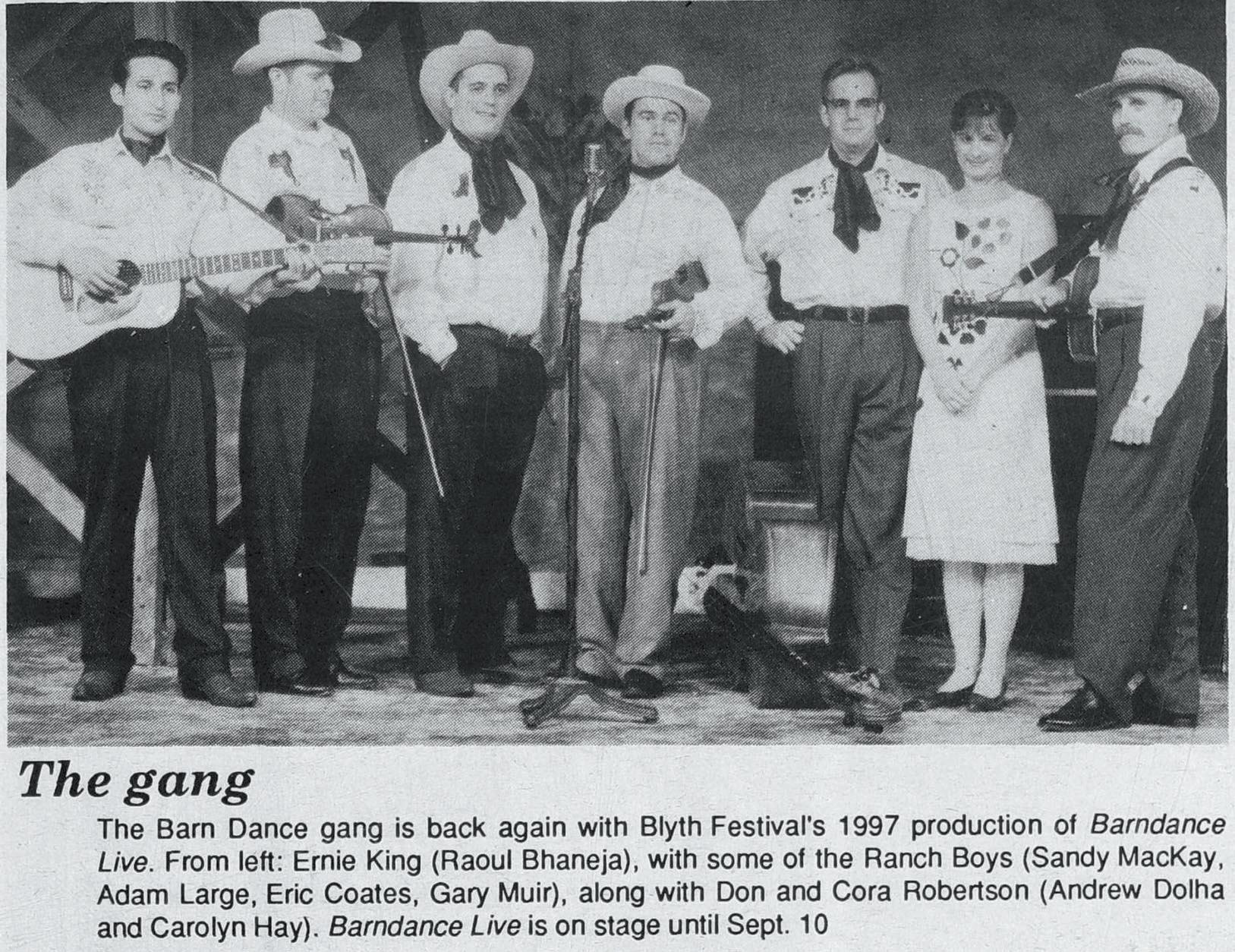

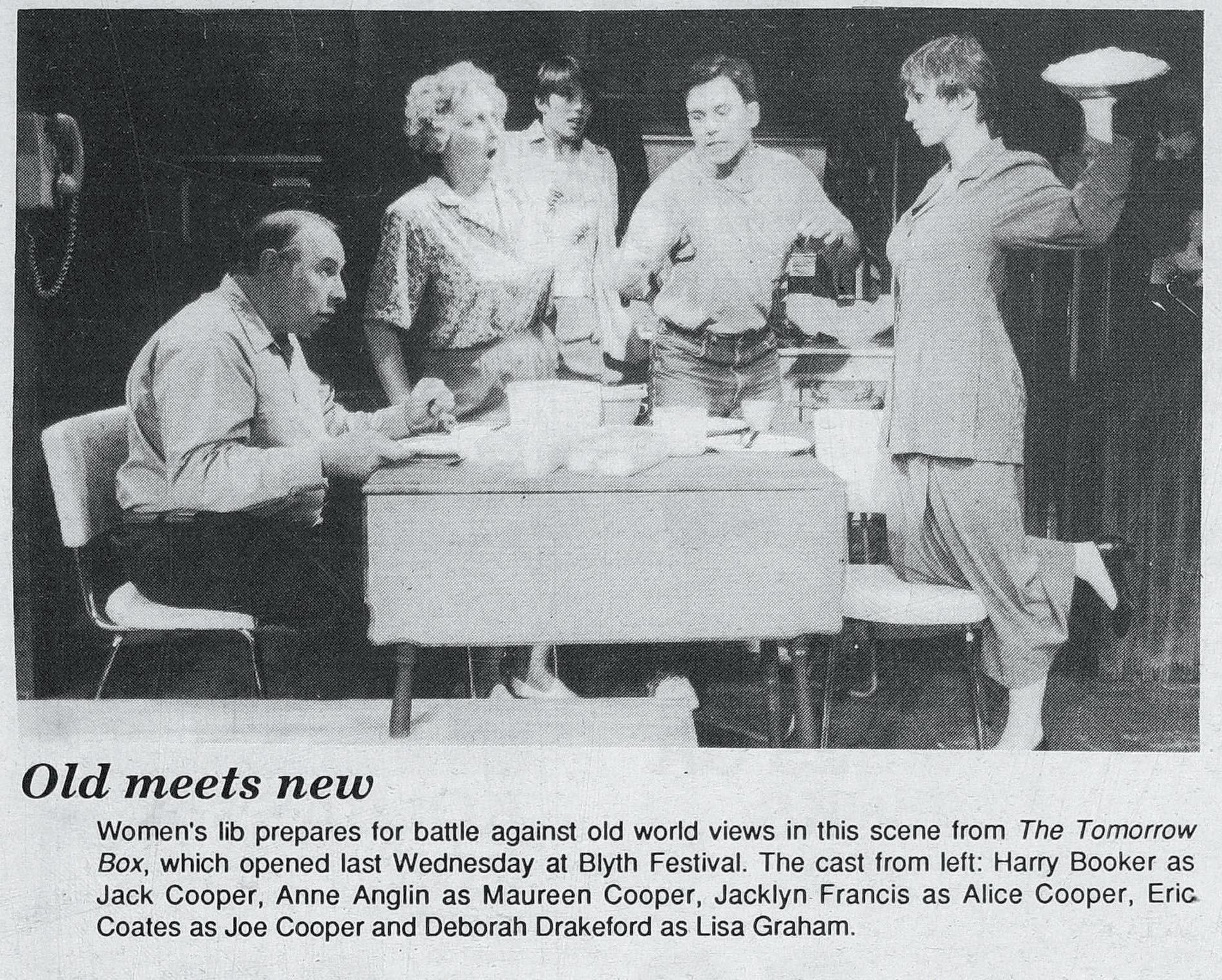

The Tomorrow Box, Jake’s Place and He Won’t Come in From the Barn returned for the 1995 season, followed by Paul Thompson’s return with Barndance, Live! in 1996 - a landmark hit for the Festival that returned in 1997. Also that season, Amos remounted Quiet in the Land and produced Booze Days in a Dry County by Paul Thompson and There’s Nothing in the Paper by David Scott.

In four years, Amos turned hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt into a surplus in excess of $100,000 and the path was again set for the Festival to succeed for the forseeable future, handing the artistic director position off to cofounder Anne Chislett in 1998.

Amos is credited by many as the person who saved the Blyth Festival and for that reason she is among the most beloved artistic directors the Festival has ever had. More than that, however, she is revered as a member of the community in a way that few others who held the position are. Her children went to school in Blyth, the family kept a home near the village for many years and Amos was named The Citizen’s Citizen of the Year in 1997 - the only Festival artistic director to ever receive that honour.

She says, even today, that Blyth feels like a second home to her. She was quoted in the 1990s as saying that Blyth was her “favourite place” and that she was always happy to return. She and Johns remain enthusiastic supporters to this day, remaining passionate and engaged with the work of the Festival, willing it to succeed from afar.

Amos, Johns and the rest of the creators of The Farm Show have been the subject of much praise this season, which has seen the remount of the beloved Canadian classic.

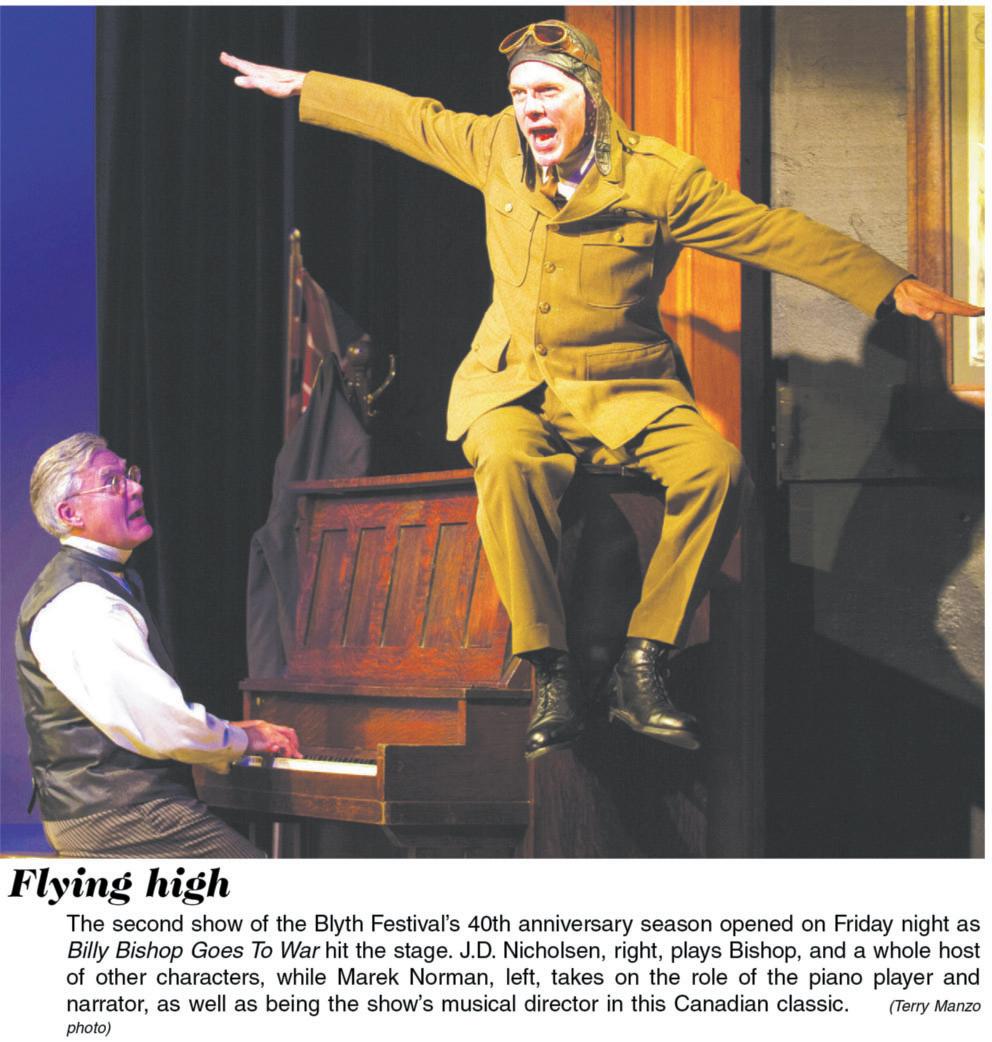

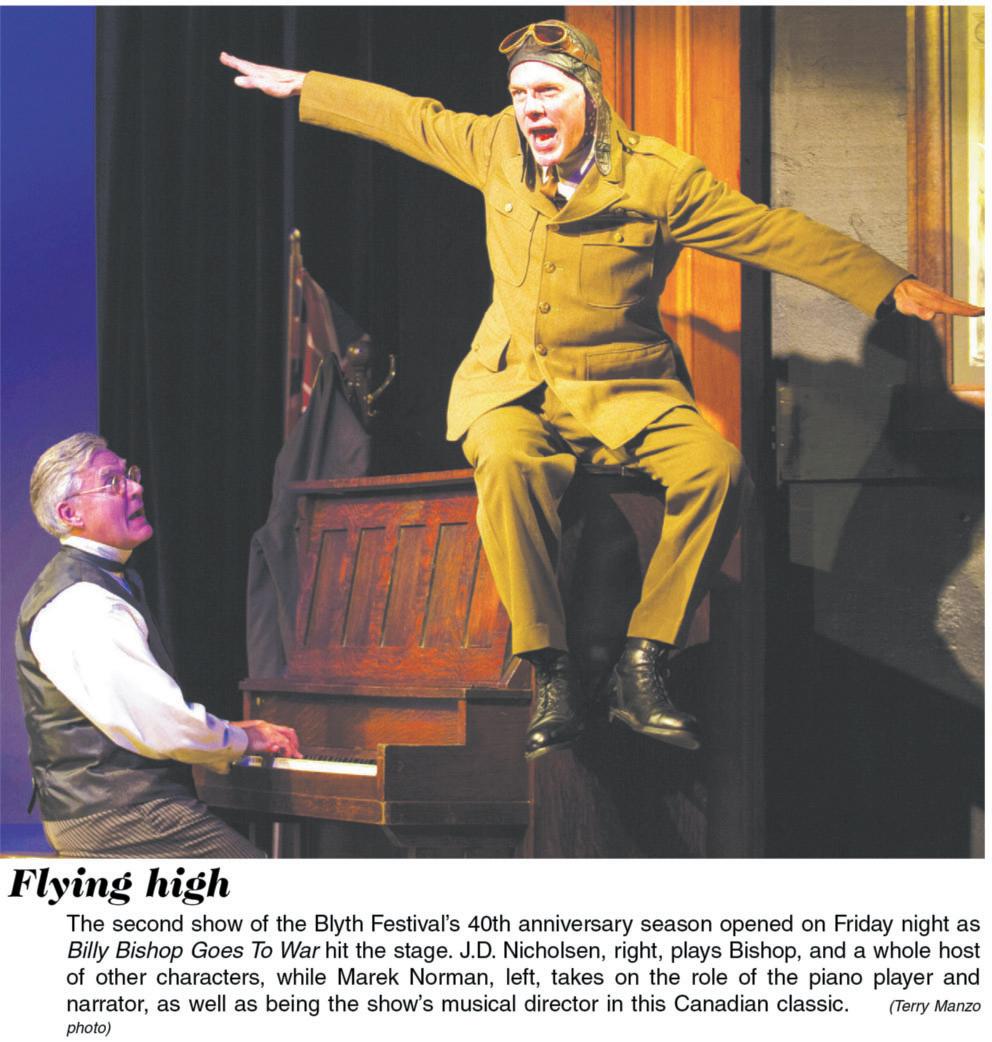

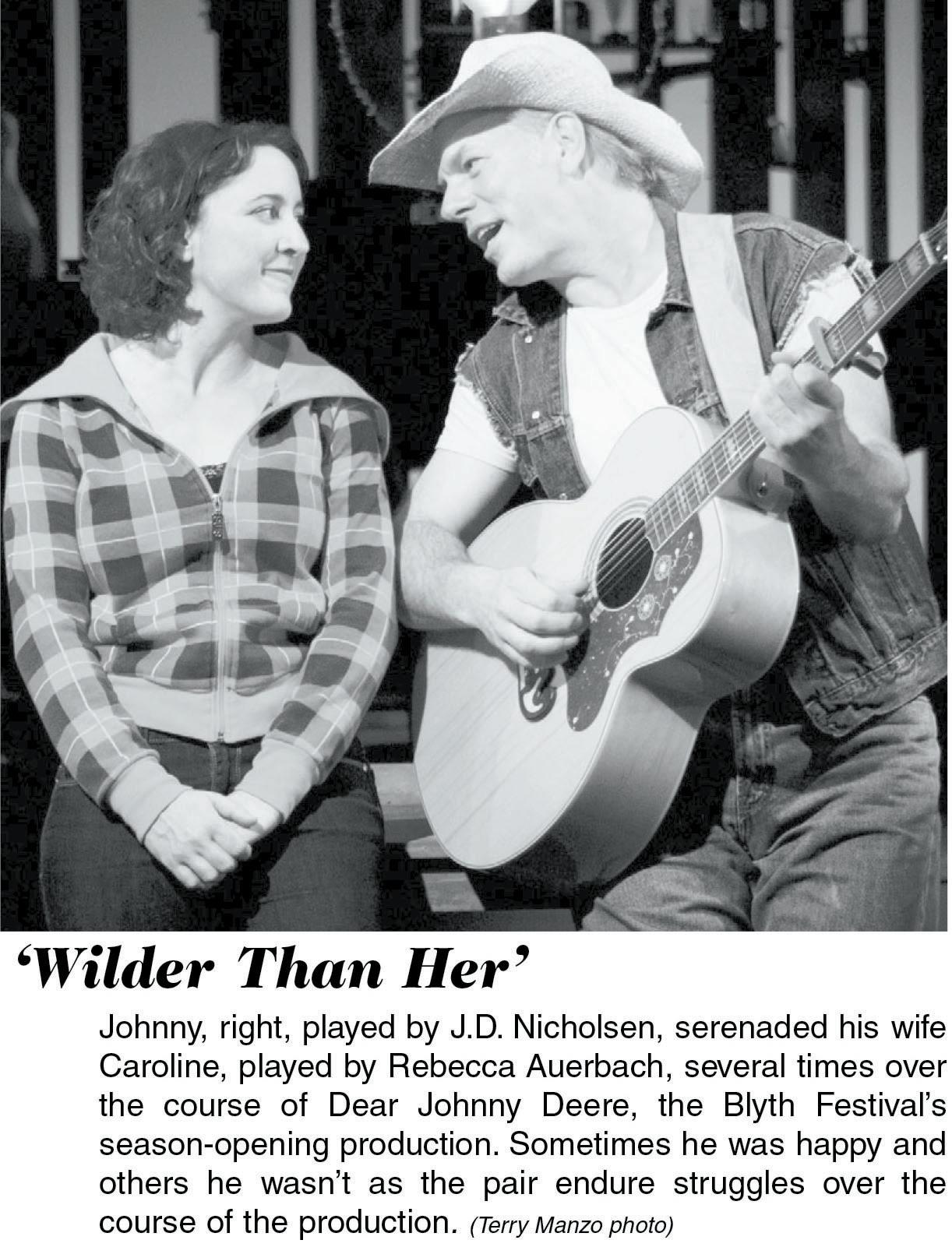

However, Amos was last in Blyth professionally 10 years ago when the Festival celebrated its 40th season under newly-minted Artistic Director Marion de Vries. She directed the Canadian classic Billy Bishop Goes to War, which starred J.D. Nicholsen and Marek Norman.

As mentioned, that season, Amos delivered the keynote address at the anniversary gala before opening night, spanning the history of the Festival, recounting her time here and celebrating those who came before her. To end her address, she recalled words written to her and the rest of what she called the “20th year saviours” from Roulston,

looking back at what was, at times, a challenging 20 years, but looking ahead to another 20 years with hope, optimism and appreciation.

“The importance of your work goes beyond anything that can be measured - beyond the frustrations you inevitably suffered, beyond any money raised. Your work was and is the foundation upon which the next 20 years can be built. You have worked very, very hard, but your efforts are appreciated and very, very worthwhile.”

In the 1990s, Roulston wrote those words to thank Amos for all she had done and in 2014, Amos volleyed those words back at Roulston to thank him for all he had done.

In the early 1990s, amid a recession and a rapidly changing entertainment landscape, the Festival faltered and neared its premature end. The people of Blyth and the theatre-lovers of Canada are forever indebted to Amos for righting the ship.

By Scott Stephenson The Citizen

The first founder of the Blyth Festival, Keith Roulston had both the dream and the drive to make it happen. The second founder, James Roy, supplied a vision for the future and enough verve to fuel those first few years which meant that the only thing left for the third founder, Anne Chislett, to add was a little bit of experience and an astonishing amount of artistic talent. She wrote and directed numerous hit plays during her time in Blyth, and was the festival’s artistic director from 1998 to 2002.

Chislett was born in Newfoundland, and first became interested in theatre when it came to

her in the form of a British theatre company that arrived on the east coast when she was a child, set up shop, and started putting on live shows. “Somehow, they made a go of it,” she recalled. “Now, looking back, I can’t imagine what the economics of that situation were.

All of us kids had subscriptions to the Saturday matinees - must have been quite inexpensive.” The London Theatre Company came to St. John’s from Liverpool in the fall of 1951 and formed the first weekly, professional, repertory theatre company in Canada. They performed 26 plays every season.

“I’d always been a little bit interested in theatre,” Chislett admitted. “I’d seen amateur shows, but it was the regular dose of

Saturday matinees that got me absolutely hooked on it.”

Chislett is the only one of the three festival founders who didn’t see the first run of Theatre Passe Muraille’s The Farm Show. “It was the second manifestation of The Farm Show that I saw. I’d just finished teaching in Clinton, and I’d moved away, but I heard about it, so I came back to see it, and it was quite magical.” She recalls less about the seminal show itself than she does the overall experience. “I remember meeting the people that it was about. It was quite interesting! At that time, there was just beginning to be a bit of Canadian theatre - but this was theatre that came right out of the community. It was unique in that way, and it was a

new experience, and it was very exciting to watch.”

Those who grew up with institutions like the Blyth Festival may take the steady stream of new, Canadian plays for granted, but Chislett recalls what things were really like back in the day. “When I studied theatre at UBC, there was never a Canadian play. There was never much attention paid to an audience. It was all very intellectual, German, abstract stuff. So, what theatre became in Blyththe emotional connection, the shared experience, the feeling of community - it’s what it must have been in ancient Greece, at the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens.”

Chislett was Roy’s assistant artistic director that first season. She recalls the same oft-told story of the original Blyth Festival throwdown in which locallyproduced underdog Mostly in Clover defeated Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap, but she recalls it a bit differently. “The legend has it that nobody saw the Christie, and everybody saw Mostly in Cloverthat wasn’t entirely true, they both did very well. But at that point, there was no air-conditioning in the theatre, and it was weather like this - so hot. The varnish on the chairs melted, so when everybody leaned forward to laugh or clap, you would hear ‘RRRRIIIIIPPPP!’”

Beyond the satisfying ripping of sticky skin peeling off of wooden chairs, there’s another sound that Chislett recalls from that night. “I

still remember vividly that first laugh in Clover - waiting for it, and suddenly hearing the audience erupt in laughter - you knew you had a hit. It was lovely.” After Mostly in Clover succeeded in really connecting to the crowd, Chislett developed a real taste for audience response. “There’s a moment, if something’s really, really, working, between the final black-out and when the applause starts. I live for that moment.”

After that first season, they put out an open call for new plays to stage. “We got two responses - one from Jim Nichol, and one from Peter Colley.” The play from Colley, I’ll Be Back Before Midnight, went on to become an international sensation. “It was a big mega-hit,” she laughed, “which is still providing the author with a luxurious lifestyle in California. It traveled the world and is still, in fact, being produced. So that’s quite amazing.”

Since not many scripts were coming in, the Festival decided to start commissioning the kind of work its founders wanted to see. “We commissioned an enormous amount of our plays. There were relatively few that came in and landed on the desk, and just had to be done. But occasionally there was. Thirteen Hands was one that I really wanted to do that already existed that had been done elsewhere. But for the most part we commissioned, because the plays

Continued from page A18 weren’t there in the beginning.”

Once they finally had the plays coming in, Chislett found it could be difficult to select among them. “Inevitably, choosing the first three are easy - for the last one or twoit’s impossible.”

One important part of the existing local culture that wound up really bolstering the Festival in the early days was the food. Specifically, the

traditional country supper. “When we started attracting an audience, there were no restaurants. There was nowhere for them to eat.

Someone was running the hotel, but it was more of a bar then... The Blue Blyth Inn. But there was the head of the Women’s Institute -

Evalena Webster. She took over the hospitality element, and produced these country suppers. It made going to Blyth a real experience for

people. It was a huge selling point.”

While she loved working with talented artists like Janet Amos, Shawn Kerwin, Ted Johns and Eric Coates, there’s one person who always comes to mind when she thinks of her time with the Festival - her frequent collaborator, Keith Roulston. “He is always my sort of go-to. Keith is always ‘Mr. Blyth’ to me. We both worked together, and he’s also the person who really

got it going, and he remains a good friend.”

One of her favourite examples of a locally-oriented success was a play she wrote with Roulston. “Another Season’s Promise evoked quite a response from the audience, and has since traveled a bit in the farming community and was

recognised by farmers. And that means a great deal to me. Other times, it’s just a lighter approach to being in Huron County, and being in rural Canada.”

She also had some pretty dynamic accomplishments during her time in Blyth, like Paul

Continued from page A18 Thompson’s T he Outdoor Donnelleys, a sprawling piece of theatrical art that took place in a variety of different locations. “It

wasn’t just all over town - it was all over the county! It had some great moments, and I loved the experience of seeing bits of it every night,” she recalled. “When

[Thompson] came with the idea, I had to get a grant for it - it was kind of expensive. I remember his face when I said ‘we’ve got the grant!’ and he realized he had to actually do it.”

Fifty years ago, Anne Chislett first set out to found a rural theatre festival with Keith Roulston and James Roy, and it’s still going strong. “It’s a bit of a miracle, isn’t it? One thing we always did, right from the beginning, with James, and with Janet, we always had the continuity in mind, so we’re always bringing somebody else along who would take over - it was never thrown out to the winds. Gil was the director of the Young Company when I was there, somewhere around 2000. So he’s been associated with it now for something like 20 years, and I’m

sure he’s bringing up people that will succeed him.”

Chislett feels that the artistic director’s job is a balancing act.

“You have to have a vision of what kind of theatre you want to present to your audience, and what audience you want to bring into the theatre. I don’t think it’s just enough to go up and throw on stage what you want to do, with stuff that you like. I mean, it’s necessary to do things you like - there’s no point in doing work that you don’t like. But I think, beyond that, there must be some overall vision of what you’re communicating. I gather the audience has changed quite a bit,

but in the olden days, we were doing plays that had a direct emotional key-in to the audience. It wasn’t like we were importing culture and showing it to them. It was involved.”

During her many years of active involvement with the Blyth Festival, Anne Chislett has certainly learned a thing or two, but there’s one thing that still stands out to her. “I learned that the point of theatre is connection to the audience. Theatre is communication - a collective experience, rather than the imposition of culture... and the thing I failed to learn was patience.”

In the mid-1990s, a young actor named Eric Coates began performing at the Blyth Festival - a theatre company he so truly admired - but little did he know that, one day, he would be among the Festival’s longest-tenured artistic directors.

As part of the 1995 season, under Artistic Director Janet Amos, Coates was part of the casts of Anne Chislett’s The Tomorrow Box and Ted Johns’ Jake’s Place (and Johns’ He Won’t Come in From the Barn for good measure). He would return the next year as part of Paul Thompson’s Barndance Live! cast and continue to act on the Memorial Hall stage until an even greater opportunity within the Blyth Festival presented itself.

However, it all started many years earlier when Coates watched The Clinton Special, a short film directed by famed Canadian author Michael Ondaatje, which included footage from the production of and making of The Farm Show , a watershed moment in Canadian theatre. He identifies that event as being a really important and formative experience in his life as a burgeoning theatre professional.

He knew that was the kind of grassroots and important storytelling he wanted to do through the theatre, so when the opportunity to act at the Blyth Festival presented itself, he jumped at the chance.

As Anne Chislett, one of the

Festival’s three founders, took over the position of artistic director in 1998, taking the reins from Janet Amos, who had pulled the Festival back from ruin in the seasons spanning from 1994 to 1997, she approached Coates about a potential mentorship placement.

Coates was paid by way of a grant through the now-defunct Theatre Ontario and he began to learn about the inner workings of running a theatre company like the Blyth Festival from one of the masters. Chislett, who not only is credited as one of the founding members of the Festival, but is celebrated as a Governor General’s Award winning playwright.

He learned about the complexity of making decisions and programming seasons and how much “armchair quarterbacking” was done by those who had not lifted the curtain on the inner workings of the Festival and didn’t understand all that it took to run it. He developed a great appreciation for the work being done and the effort it took to do it.

And yet, when it was time for him to take the reins, Coates admits that he was brash and more concerned with his own personal successes and importance than he was with the success and importance of the Festival, calling his first season in 2003 an “unmitigated disaster” that was saved only by the runaway success of David S. Craig’s Having Hope at Home - a touching comedy that he would remount as part of the 2012 season.

Coates said he was tremendously humbled by that first season and that he learned a lot from its failures and successes. He said that getting over himself, to a certain degree, was an important step, and he looked to the advice and guidance of those who had come before him, citing the famous Mark Twain quotation, “When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around, but when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.” One of the misfires he remembers vividly was attempting to mount

David French’s famous trilogy of “Mercer Plays” beginning with Leaving Home in 2003, which was not received well at all, despite its reverence in the theatre world across the country.

Undaunted and committed, Coates stuck to his guns and produced Salt-Water Moon in 2004, which was a slight concession from his original plan, mounting the plays out of order to include the widely popular Salt-Water Moon ahead of Of the Fields, Lately, the linear second play in the trilogy. He abandoned his plan in 2005 and did not produce the third French show at the Festival.

He said that Salt-Water Moon found a modest audience in 2004, exceeding the success of Leaving Home, but, in what he said was a clear and shameless attempt to ingratiate himself with the local audiences after a so-so first season, he remounted The Outdoor Donnellys, a collective helmed by Paul Thompson and Janet Amos. The show had found so much success in 2001 and 2002 that he returned to the well and it paid off, as audiences flocked back to the

theatre, eager to see one of the Festival’s landmark shows one more time.

As predicted, it was a success and Coates also struck gold with Anne Lederman’s Spirit of the Narrows, which he would remount in 2005 due to its success. Also that year, he produced Powers and Gloria by Festival co-founder and noted playwright Keith Roulston, in addition to the remount of Peter Colley’s I’ll Be Back Before Midnight, another of the Festival’s hits from years past.

Then, in 2006, Coates hit his stride with The Ballad of Stompin’ Tom by David Scott and Another Season’s Harvest by Roulston and Chislett, marking a return to the realities of farming in Canada in the early 2000s in a much-heralded sequel to Another Season’s Promise from 1986 and 1987.

Coates said he was never exactly “comfortable” in the position of artistic director, which is a good thing, but he did say that with that season he began to feel as though he understood the theatre and its audience a lot better than he did in

Continued from page A21 his earlier seasons. Furthermore, he said he, slowly but surely, began to learn the important lesson that he would never please everyone.

The next season brought with it one of the pieces of which Coates is most proud: Reverend Jonah by Paul Ciufo, a finalist for the 2008 Governor General’s Literary Award for Drama. The show represented the kind of progressive story Coates strived to tell, including the first same-sex kiss in Festival history.

And what made all the difference in being able to tell that story, Coates said, was having a local person tell it. Ciufo, who has flourished as a Huron Countybased playwright both at the Festival and beyond, had an understanding of the community and its ways that was such an asset to the story being told in Reverend Jonah, Coates said, and it made it digestible for the Festival audience.

The next year he found another hit with Innocence Lost: A Play About Steven Truscott, written by Beverley Cooper, a finalist for the Governor General’s Award that year, giving Coates and the Festival back-to-back nominees.

Coates says, embarrassingly, that he rushed to produce the play before the Supreme Court ruled on Truscott’s years-long battle. He said it was important to tell the story from the Huron County perspective before that decision was made and to not “jump on the bandwagon” after it had been made, regardless of the outcome of the decision.