Common Ground

A Land Conservation Guide for Local Government

Allison DeFoor, President & CEO

THIS GUIDE WRITTEN BY

Ramesh Buch, Director of Conservation Acquisitions

Heather Nagy, Strategic Conservation Planning Coordinator

Will Wanzenberg, Associate Acquisitions Coordinator

A SPECIAL THANK YOU

The North Florida Land Trust (NFLT) gratefully acknowledges the support of the Live Wildly Foundation for this project.

NFLT also acknowledges the time and contributions of Alachua County Commissioner Ms. Anna Prizzia, Mr. Avery Roberts, CEO of the Roberts Companies, Clay County Assistant County Manager Ms. Chereese Stewart, Mr. Tim Telfer, Chief of Conservation Acquisition for Volusia County, and Ms. Margaret Kirkland, Chair, Conserve Nassau.

NFLT also extends its appreciation to Mr. Zach Franco, Conservation Partnerships Coordinator at Archbold Biological Research Station.

Finally, we salute all the land conservation professionals, advocates, elected officials, and especially landowners who work to make the map a little greener for future generations.

THANK YOU!

Find your place on the planet. Dig in and take responsibility from there.

GARY SNYDER

Greenprinting

Definition: An adaptable, collaborative, strategic approach that reveals the range of benefits nature provides a community and suggests ways that a community can protect or enhance those benefits. It engages government, stakeholders, partners, and the community and uses the best available science to identify multiple-benefit nature-based solutions for decision-makers. These solutions can range from conserving natural or working lands and protecting drinking water, to supporting rural economies, restoring habitat to protect wildlife, expanding urban forests, and designing parks to improve community health.

Guide Summary

In his essay What Are People For?, Wendell Berry wrote, “You cannot know who you are until you know where you are.” A Greenprint allows a community to preserve place as a part of their identity. Through the process of Greenprinting, communities can identify strong land conservation projects, evaluate them effectively, and manage their acquisition and long-term stewardship. Most importantly, it empowers residents to feel confident in the decisions being made. NFLT employs a line-of-sight model to help communities establish a clear and achievable path toward building a portfolio of well-managed lands that reflect local values, one that is ecologically, politically, and financially sustainable.

It is important to note, when we refer to land conservation projects in Florida, we are only discussing willing-seller, voluntarily-negotiated, arm-length transactions that are based on market valuations of property.

A TYPICAL NFLT GREENPRINT INCLUDES THE FOLLOWING ELEMENTS:

• Stakeholder meetings with local officials to develop an inventory of existing expertise, document libraries, best practices, needs, and opportunities.

• Interviews with subject matter experts to develop an inventory of resource needs and begin to identify potential conservation values.

• Meetings with Commissioners to build consensus on the direction of a potential land conservation program and to identify the conservation values of the Commission.

• Community engagement, including public workshops to shape the program’s values and outcomes, and polling of citizens and likely voters, to understand community conservation values, priorities, and willingness to support public funding.

• An online survey tool for those who cannot attend live workshops so they can also learn about the proposal and provide input

• A comprehensive Final Report, offering program recommendations, a model program description, draft enabling legislation, and sample referendum language.

NOTES:

• In this document, Key Principles are in Bold Text

• The highest level of legislative authority in a local community in Florida is typically a Commission or Council. We use the term “Commission” throughout to generically refer to these legislative bodies.

Greenprinting 101

A Greenprint is a specialized form of strategic conservation planning. At its core, it is a tool that helps a Commission identify, prioritize, and pursue natural, agricultural, and cultural resources for conservation. Like any effective tool, it must be tailored to the task at hand. In this case, the plan needs to identify and prioritize the land based on inputs from the community. It follows then that the necessary first step

is to identify the conservation values the community wants to protect—and therefore see represented in the portfolio of acquired property.

What do we mean when we say Conservation Values?

These are the characteristics of a piece of land that generates some type of benefit the public values. As illustrated in Figure 2, open spaces offer a wide range of benefits that enhance a community’s quality of life. Historically, conservation values were narrowly defined as ecological: natural resources, wildlife biodiversity, or habitat. However, over time, these values have been broadened to recognize the importance of outdoor recreation, cultural and historic resources, farms and ranches, storm protection, flood control, aquifer recharge, water quality improvement, and buffering military bases from encroachment. If programs are established in a well-thought-out manner, the community can fully reap the benefits conservation lands provide, forever. None of these benefits are guaranteed. If we do

BENEFITS OF LAND CONSERVATION

not protect the lands that generate these benefits, they will degrade and disappear forever. This distinguishes open space from land conservation, which is the intentional act to preserve these benefits that come from the land. The goal of Greenprinting is for your community to make a fully informed decision on what its future will look like. Greenprinting helps you identify which lands should be conserved with limited public resources and funding.

THE GREENPRINTING PROCESS:

1. ENGAGE THE COMMUNITY: Begin by conducting interviews and polls of the public, subject matter experts, community leaders, and Commissioners. This helps determine the relative importance of various public benefits — such as recreation, water quality, or farmland preservation — and gauge the community’s desire to protect them. For example, one may care about both recreation and water quality protection but may prioritize one more strongly.

2. DEFINE CONSERVATION VALUES: Translate these prioritized benefits into clearly defined conservation values that reflect what the community wants to protect.

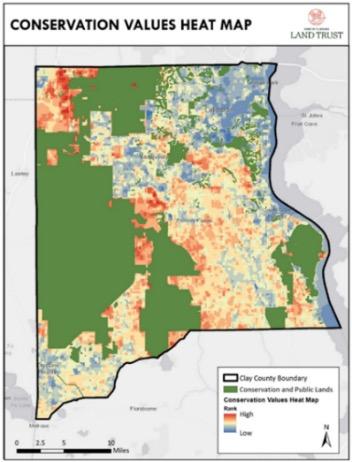

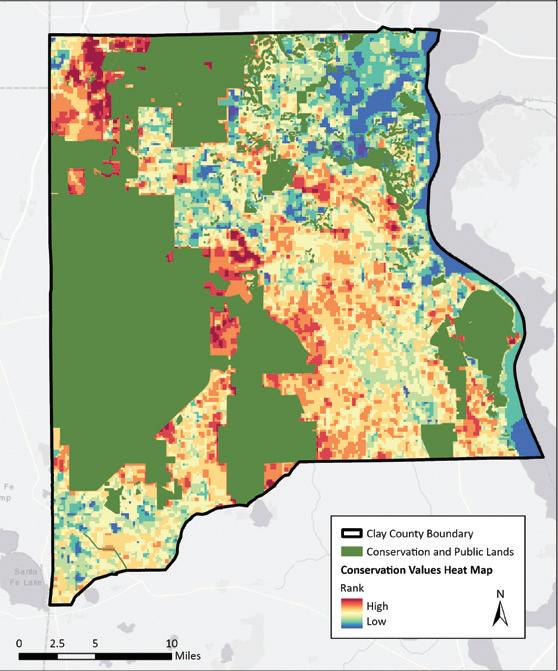

3. APPLY SCIENCE-BASED ANALYSIS: Use scientific data to map where the resources that support the identified conservation values are located and assess their significance. If protecting water quality is valued, then land areas that influence water quality are identified using credible, science-based data.

4. DEVELOP STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS: Finally, provide clear, actionable recommendations on how to best protect these identified conservation values—ensuring community goals are met with precision and efficiency.

CLAY COUNTY GOOD PLANNING, GREAT RESULTS

In November 2024, Clay County voters approved their new Forests and Farms Program with an approval rate of 72.9%. This referendum approved $45MM in new funding for conserving water quality, agricultural property, and wildlife habitats. Chereese Stewart has served as Clay County’s Assistant County Manager since 2021. She was born and raised in Clay County and witnessed firsthand how her community was changing. With the building of the Beltway though the middle of the county, county leadership decided to explore ways to preserve portions of what made the county special. She had heard about NFLT’s work in Nassau County and sought out advice on whether such a program was possible there.

A very conservative community, Clay County leadership insisted on a strategic, measured, and inclusive planning

process; one that emphasized determining what their residents’ conservation values and priorities were, and what their tolerance was for for providing new funding sources to protect them.

NFLT held two workshops with the county commission, three more spread out in the community, and posted the information and a polling tool online so that those who could not attend in person could view the presentation, vote, and be heard. In addition, NFLT’s partner, the Trust for Public Land, polled voters to determine if what we were hearing in the community was truly representative of county voters. TPL’s polling mitigates biases that can arise from group meetings and means the resulting data is highly predictive of the results of the referendum.

As Chereese said. “At the end of the day, it needed to be a group effort; we wanted to make sure the right information got to the community so they could make up their minds and then tell us -- the county -- what they wanted us to do. I was thinking we’d pass by 60%. Getting to 73% demonstrated the value in the early planning and community engagement.”

THE COMMISSIONER’S PERSPECTIVE

There is a proven model for developing, launching, and running local conservation programs — what we call the “Line-of-Sight” model. As illustrated in Figure 3, this model aligns the outcomes to the community’s identified conservation values. Simply put, the property conserved must provide the benefits that the community desires, or that they perceive would be lost.

To keep aligned and focused on delivering meaningful outcomes, well-run programs must incorporate several key features. Examples include enshrining the specific conservation values in the program’s enabling legislation,

developing an evaluation tool that accurately assesses how well a nominated property meets those conservation goals, and the extent that the desired conservation values are present. For a practical example, refer to the Alachua County Forever sidebar on page 9.

Local land conservation programs are typically established through voter referenda for several reasons:

• Funding outside of core services: Land conservation, while widely supported, is often considered a “nice-to-have” rather than a core function of

Commissioner Anna Prizzia was first elected in 2020 and re-elected in 2024. She said close to 50% of the decisions the Commission makes tie to land use in some way, and 25% related directly to development actions.

She said support for land conservation crosses the boundaries of conservative, liberal, rural and urban communities. She thinks Commissioners understand protecting land benefits their communities because everyone is connected to it in some way, hiking, hunting, fishing, or farming. People now understand land provides economic benefits like filtering water and air, acting as carbon sink, and mitigating storm effects. It’s why programs pass with an average of over 64% of the vote in Florida since 1999.

She recognized some land is taken off the tax rolls, but the majority have agricultural exemptions, and the impact is offset by not having to provide public services. She pointed out that the Community Rating System lowers home and business owners’ insurance

rates when communities buy conservation lands thereby eliminating development in high hazard areas and preserving wetlands.” She recognized that agricultural lands are protected by conservation easements, so they stay private and on the tax rolls, preserving food security, and traditional ways of life. These protected farms open the door for the next generation of farmer who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford the price of land.

Her advice for Commissioners who might be considering starting a program: “Think strategically about what your community wants, structure a program appropriately, and stay in touch with the community as the programs run to meet their needs as they change over time.”

Alachua County initially focused on protecting conservation lands. The succeeding referendums added improvements to municipal parks, then preserving farming lands. She keyed in on transparency and accountability and emphasized, “there is a management cost to these lands. Long term, you are going to still own these lands, probably long after that tax is gone. Your liabilities don’t stop at the buying.”

“Overall,” she said about land conservation, “you can fly multiple kites with one string. I think it’s a win-win. For you and for the community.”

government. As such, fiscal prudence and Commission fiduciary responsibilities require them to find funding for it that does not negatively impact their core services. Referenda are typically used to determine the public’s tolerance for additional taxes, and all of Florida’s local land conservation programs were established pursuant to referenda.

• Public mandate and long-term legitimacy: A referendum provides the strongest possible public mandate, instilling confidence and trust in the program. This legitimacy extends to the staff and Commissioners as they implement the program, requiring their adherence to the principles and values in the voter-approved language. It may take years to fully implement, transcending the tenures of elected officials and staff. Because the program is voter-approved, it carries a lasting legacy.

• Maximizing voter participation: Referendums should be run during high-turnout elections —typically a Presidential or mid-term election year. This timing allows most voters to participate and overcomes any objections from those who do not participate except in these important years.

The process of preparing a referendum is typically led by the Attorney’s Office, Executive Administrator, and Budget Director. They oversee everything from the ordinance drafting, to navigating state and local approval processes, with support from departments such as Planning, Public Works, and Parks & Recreation as needed, or as available.

In Florida, land conservation and open space referendums are consistently successful. Since 1999, voters have approved 87 of the 103 local conservation ballot measures —an 85% success rate— with an average of 64% of voter support. These measures have passed in both rural and urban areas and in counties across the political spectrum. In total, voters approved more than $4.8 billion in local funding for conservation programs, supplementing the billions of dollars that the state and federal government spends in Florida. This is because with a local program, the community gets to protect places that are special to them, and that may otherwise fall under the state or federal radars. They can also use their local program funding to attract those state and federal dollars, leveraging their smaller pots to protect more land that benefits them. For an interactive map of all the local programs in the State, please visit www.nflt. org/preservation-priorities/community-conservation/map.

As part of the process, NFLT recommends that communities include a Feasibility Study conducted in partnership with The Trust for Public Land. The timing of the Feasibility Study and subsequent polling is critical; it needs to be done early enough for the community to secure approval of the ballot title and summary from the Florida Secretary of State, the Florida Attorney General, and the Florida Supreme Court. It is imperative that the polling reflect the social, political, and economic conditions of the upcoming election season—capturing a realistic picture of voter sentiment. The timeline in Figure 4 below shows a proposed schedule with key milestones.

CAN WE AFFORD NOT TO PROTECT THE LAND?

One of the prevailing arguments against land conservation is that taking lands off the tax rolls raises the cost of living for residents. This narrow view fails to understand that Commissioners must take a systematic, comprehensive, and far-reaching approach to solve the issues they deal with. The scientific and economic literature demonstrate the benefits of open space; benefits that translate to active residents, healthy populations, high productivity, reliable food and fiber supplies, and amenity value for residential development.

Two examples of the latter: A 2017 Study in the Journal of Urban Planning showed, that sales price of houses in Alachua County increases 0.04% for every percent decrease in distance to the nearest conservation land in general [and that] purchase of environmentally sensitive lands has an immediate and positive influence on neighboring property values. (Cite: J. Urban Plann. Dev., 2017, 143(3): 04017003). The 2011 Ludlam Trail Study in Miami-Dade County showed that the presence

of Ludlam Trail, a nature trail, will increase property value within 1/2 mile at an annual pace of 0.32% to 0.73% faster than other properties throughout the county translating into a 25-year property value increase between $121 million and $282 million. The county will receive between $31,900 and $80,000 in sales tax from trail related expenditures while the State of Florida will receive between $191,400 and $480,000 annually in sales tax. (Cite: Miami-Dade County Park and Recreation Department, January 2011. AECOM)

Another direct example comes from our drinking water. We essentially mine old rainfall from the ground or pull it from the surface. The cost of treating that water and bringing it up to the standard we all want to consume it depends directly on the starting quality of the ground or surface water. That is dictated by the watershed upon which it fell.

Ultimately not every benefit can be translated to economic value. But even a casual observer knows living in a community with access to green space is preferable to one without. It is the responsibility of government to protect the foundations of their residents’ quality of life.

ACQUISITION AND MANAGEMENT OF WATER RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL LANDS BOND REFERENDUM

To acquire, preserve, protect, manage, and restore, water resources, environmental lands and important fish and wildlife habitat, shall Polk County levy an additional 0.20 mill ad valorem tax and issue bonds payable thereform in one or more series in an aggregate principal amount not exceeding $75 million, excluding previously-authorized indebtedness, maturing no later than 20 years from the date of issuance of such bonds, bearing interest not exceeding the maximum lawful rate?

Figure 5 above provides an example of referendum language, drawn from the successful Polk County program. The highlighted red text represent the key variables that the Greenprint and the Feasibility Study are designed to tease out from the community. These elements help shape a ballot question with the strongest chance of voter approval. These also serve as the foundational principles of the conservation program and form the basis of the Line-of-Sight model.

Structure and Operation of Local Program

Ideally, the new program should be integrated into existing county processes for property acquisition, strategic planning, legal oversight, budgeting & accounting, agenda review and approval. As land is acquired, process, operational, and capacity enhancements may be necessary to support ongoing operations. A best practice is to house the program within a department whose mission aligns with conservation goals and to form cross-functional “strike teams” from existing staff to manage specific tasks such as property evaluation, real estate negotiation, and land management. One of the most common reasons programs fail is lack of sufficient capacity or expertise. Shortly after the successful referendum, the community will expect to hear about application cycles being opened, property being evaluated and approved for negotiation, purchases made, and property being made available for public use. Meeting these expectations requires a well-resourced and well-coordinated team.

Acquiring conservation land is a specialized form of real estate transaction. While it shares many steps with residential or commercial real estate, the process

involves unique complexities that require specialized practitioners, especially when negotiating conservation easements, which introduce additional legal and technical considerations. Not every community has all the necessary expertise, and the use of qualified contractors and consultants is appropriate to enhance and supplement the governmental capacity. These professional services are typically funded from the same source as the land acquisition budget. As the portfolio of conservation land grows, so too must the capacity and resources for their proper management. Budgeting the acquisition and stewardship of these lands should be as carefully considered as any other public asset, be it a library, community center, a fire truck, or public park. Well-managed conservation lands add value to the community; poorly managed lands can cause blight, attract nuisance behavior, and become a liability to its neighbors.

Evaluating Property Applications

It is common for agencies to receive an initial surge of property nominations from the public—each reflecting individual opinions about what “should be saved.” It is vitally important for a successful program to properly evaluate and accept — or reject — applications. Effective evaluation is a cornerstone of the Line-of-Sight model and arguably the most critical element to get right. Successful programs develop an evaluation tool that assesses each application objectively, fairly, consistently, and accurately. So, the criteria that are used must promote lands that meet the Referendum values and reject those that do not. For more information, refer to the Alachua County Forever sidebar on page 9.

ALACHUA COUNTY FOREVER

THE RIGHT TOOL FOR THE JOB

Alachua County voters approved their first conservation program in 2000. Based on polling done in 1999 by The Nature Conservancy, 85% of voters said they wanted a program that protected water quality, 78% said they wanted to protect endangered plants and animals, and 75% said they wanted more amenities and areas for resource-based recreation. These values became the basis of the Alachua County Forever (ACF) Referendum:

“To acquire, improve and manage environmentally significant lands, to protect water quality and wildlife habitat, and provide areas for low-impact, resource-based recreation” which passed with 60.6% of the vote.

It was so successful that voters renewed the program three more times; with a Wild Spaces Public Places referendum in 2008, and again in 2016, and more

recently in 2022 when the voters added saving agricultural lands. Critical to the County’s success was a rigorous application of criteria that facilitated the selection of project that best met the referendums’ goals. Projects were evaluated using 26 separate criteria designed to evaluate how well the property would meet water quality and quantity goals, habitat protection goals, and resource-based recreation goals. There was an additional acquisition and management section of criteria that serve as a tie-breaker. Scores ranged from a low of 2 to a max of 10. At one time, the ACF Program had an approved list with an average score over the 5.4 and acquired a portfolio with an average score over 7.0 and had acquired 7 of the top 10 scoring projects. This means the best lands were selected for consideration and the best of the best were acquired.

Reauthorizations of the program would not have been possible if the program was not meeting the desires of the public. Such is the power of using an evaluation criteria tool, and using it to benchmark its success.

FIGURE 5 Sample Referendum from Polk County, Florida

If we accept that the primary conservation values for a hypothetical Happy County, Florida are (1) protecting threatened and endangered species and habitats, (2) safeguarding drinking water sources, (3) preserving farms and working forests, and (4) expanding access to nature-based recreation, then the evaluation tool should contain criteria that evaluate whether these benefits arise from the candidate property. Table 1

illustrates how each of these four conservation values can be translated into measurable evaluation criteria, along with examples of data that might be used to assess them objectively. This is a sample list and a program may choose to include additional values or refine these criteria over time. The most important principle is to ensure decisions on conservation values are guided by reliable data and a consistent framework.

CRITERION

Threatened and Endangered (T&E)

Species and Habitats

Is there potential for T&E Species to exist?

Under-Represented Natural Communities (FNAI)

Environmental Sensitivity Index Invertebrate Habitat Areas (FWC)

Are there habitats that are present or could be restored so T&E Species can thrive?

Rare Species Habitat Conservation Priorities (FNAI)

Florida Wildlife Corridor (UF-CLCP)

Drinking Water

Farms and Forests

Does the property recharge the drinking water aquifer?

Are there potable wells relying on recharge from this property? Would polluting this property affect potable wells?

Is the property currently in agriculture?

Aquifer Recharge Areas (FNAI)

Public Water Wells (FDEP)

At some point, the program will need to reject an application that someone believes is important, making it essential that the decision is transparent, data-driven, and defensible.

Access to Recreation

Are they highly productive operations?

Are they operating sustainably and responsibly?

Is the operation in a federal priority area?

Is the property within a state park priority acquisition area?

Is it in a recreationally underserved community?

Existing Agricultural Lands (FDACS, FDoR and local property appraisers

Existing Tree Plantations (FWC Cooperative Land Cover Map Project)

High Productivity Timberlands (FDoR, Tax Parcels) Soils Productivity Index (USDA)

Sustainable Forestry Areas (FNAI)

Rural Conservation Partnership Program (USDA)

Park Optimal Boundaries (FNAI, FDEP)

ParkServe Priority Park Areas (TPL) (Local Comprehensive Plan)

FDEP Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP)

Is it in a state conservation area project?

Florida Forever Project Boundaries (FDEP, FNAI)

Rural & Family Lands Protection Program (FDACS)

Evaluation criteria are typically assessed using GIS data and other readily available sources. If additional details are needed, a site verification visit should be arranged with the landowner. Each criterion is scored according to how well that property would meet that criterion: E.g. 1 = None, 2 = Less than Average, 3 = Average, 4 = More than Average, 5 = Best. In addition to these resource values criteria, Alachua County had a Stewardship and Acquisition Issues section which was weighted so it could serve as a tiebreaker. For example, when two properties provide comparable conservation value, preference is given to the one that is easier and more cost-effective to acquire and manage—reflected in a higher stewardship and acquisition sub-score. The final project score is the sum of both sub-scores, providing a balanced assessment that accounts for both conservation impact and practical implementation.

The evaluation scores can also serve as a benchmark for measuring the program’s effectiveness in meeting its core objective: Protecting properties

that align with the conservation values outlined in the referendum. Alachua County Forever, for example, used these scores to annually review the overall conservation value of its portfolio. This process helped assess whether the program was receiving strong nominations, prioritizing high-scoring properties, and protecting the most valuable lands. For more information, refer to the Alachua County Forever sidebar on page 9. This kind of scoring and self-review leads to greater voter confidence and a higher chance of successor programs being passed.

Conservation Easements

Fee ownership of property is thought of as owning all the rights to put that property to any use – subject to local regulations and codes. If many of those rights were used, e.g. mining, building subdivisions, and clear-cutting natural forests, the conservation value of the property would be impacted or completely lost. Some property can be considered so ecologically valuable that fee ownership by an agency is necessary to protect those functions. However, not all property is for sale in fee, nor do all require full public ownership to protect the values they contain. Conservation easements are typically thought of as the purchase of just the development rights but are really the purchase of the bundle of

THE ADVOCATE’S PERSPECTIVE

Margaret Kirkland is the chair of Conserve Nassau, a citizen’s advocacy group pressing for conservation of land in Nassau County, Florida. “I grew up knowing a little about land conservation because my family was raised on a farm. I retired to Amelia Island, Nassau County, full time in 2011, knowing nothing about the ecology of North Florida. Then, a group in the community formed Amelia Tree Conservancy. As part of the leadership, I needed to know as much as possible about the ecology of the area to write articles and make presentations, so I did a lot of research on the topic. At some point I realized that land conservation was our best hope for saving as much of our natural environment as possible.

“Together with others in the community, I worked tirelessly to get our Nassau County initiative passed. We were successful because the community realized we are rapidly being overdeveloped and losing our natural and healthy land. Unfortunately, perhaps because of our development crush and a late start on this effort, not nearly enough has been done to maintain sustainability, resilience, wildlife corridors, water quality, natural features, etc. We are losing or have lost the most critical opportunities for land conservation on Amelia Island and in the eastern half of Nassau County.

“The majority in our community support land conservation and I still spend roughly 10-15 percent of my time in public meetings advocating specifically for land conservation. The Nassau County program passed, but the process is slow. My advice to other communities is to start early and push to advance the process as rapidly as possible. Also, constant engagement with the community is critical to maintain trust and commitment.”

rights that if used – or continue to be used – would negatively impact the conservation values. Conservation easements are a great tool for the community to maximize conservation value using limited funds. Not every property needs to be owned and managed by the government for its conservation values to be protected.

Conservation easements allow for the protection of property without taking the private landowner out of the equation. In many cases, landowners are better suited than public entities to manage their property, especially on working lands. Besides wildlife and water resource benefits, these agricultural lands provide economic value to the region, food security for the nation, income and jobs for the community, and add to the rural and traditional ways of life for many in the state. The landowner is compensated based on the decrease in the market value of their property. Depending on the location of the property, the uses being restricted and the demand for them, and other considerations, conservation easements typically range from 50% - 70% of the fee simple value. Therefore, a conservation easement can protect land at less cost than purchasing the fee-interest, minimize the perpetual costs of stewardship, and keep the property on the tax rolls and generating income.

Because conservation easements typically remain in private ownership, they often do not provide public access. As a result, they may score lower in some evaluation systems leading to them being not selected for consideration - a common but misguided oversight. Conservation easements are a powerful tool for protecting vital connections and resources when the property is not for sale, or when it is not cost effective to purchase it in fee, or when it would be detrimental to remove the producer and their contributions to the economy and the landscape.

Advisory Committees

Acquiring conservation lands requires both expertise and oversight. To keep the voters’ trust that the best properties were selected and public dollars spent responsibly and transparently, a citizen’s committee should be established. This is the hallmark of every successful local program in Florida. Extensive polling

demonstrates voter support rises if this is a feature of the proposed local program.

These advisory committees add significant value because they can:

• Bring expertise from the community that may not be present on the Commission and represent different stakeholders.

• Act as a resource for the Commission, providing research, advice, and recommendations on policy issues relating to conservation land acquisition and stewardship.

• Spend more time digging into the criteria and evaluating property that might be available to commissioners.

• Handle the public input at this evaluation and filtering stage.

Typically, the advisory committee supports the county’s land conservation program through five key responsibilities:

1. Evaluation of nominated property by using the evaluation criteria.

2. Review of potential acquisitions for compliance with adopted rules and procedures.

3. Review of Land Stewardship Plans.

4. Conservation easement review.

5. General advisor to the Commission on land conservation issues.

The committee’s central role is to evaluate nominations of property and make recommendations to the Commission on which lands should be purchased. No property should be purchased without having been reviewed by the committee. It is entirely appropriate that, for a disclosed public purpose, the Commission may reject the committee’s recommendation. However, the Board of County Commissioners may not add to or expand its active acquisition list with any property that has not been evaluated and recommended by the committee. Advisory committees ensure transparency, accountability , and provide a structured forum for

public input and discussion. It is also important to recognize that public funds used for these acquisitions are raised from all taxpayers, including those who may have voted against the program. This makes it even more critical that decisions are made with fairness, integrity, and a strong foundation of public support.

A Final Note on Stewardship

Imagine that a conservation land’s ability to deliver benefits to the community can be scored from zero to 100% conservation value, with 100% being a perfectly functioning property providing its benefits with minimal management. A property is acquired with a function score somewhere on that scale. Rarely do you get to acquire a perfectly functioning property. Depending on the type of property, its ecological, recreational, or agricultural values can always be enhanced. It should be a core principle of the agency that the overall quality and integrity of its conservation land portfolio must not decline under its stewardship.

While it is desirable to restore any degraded functions, and reach 100% conservation value for for every acquired parcel, that is neither affordable nor practicable in the short term. This principle has budgetary and operational ramifications. To address these constraints, certain traditional land uses—such as hunting, cattle grazing, or sustainable forestry—may serve as interim management tools. These traditional practices can maintain conservation values while allowing other lands to be restored or until restoration funds become available. It may also be appropriate to manage some land as perpetual revenue-generating properties to offset the expenses of the entire portfolio. Each property should have a management plan approved by the Commission that articulates a clear vision for that parcel. The plan’s primary objective should be to increase, or at least maintain, its conservation value score, with all strategies and activities aligned toward either enhancing those values or preserving current conditions until further restoration becomes possible.

KEEPING THE FAITH VOLUSIA COUNTY

Tim Telfer is Volusia County’s Chief of Conservation Acquisition, running the Volusia County Forever Program since 2021. Before that, he ran Flagler County’s Program for 17 years.

Tim said his No. 1 priority is keeping the voters’ trust.

“One of the things we do well is build trust in every project. We build trust with each landowner as they work through our process. We want them to stick with us on a transaction where they might get more money on the private side. That starts with early communication building expectations, acting as a guide.”

“This kind of trust can really facilitate future deals. Our large landowners all know each other. We need them to have a good experience of working with us so when they do, they’ll talk to other landowners about it. The old saying is true, you know, trust is built in drips and lost in buckets.”

To build trust, Tim put a dashboard on the website where the public can, with a couple of clicks, learn about program and its progress. He also communicates with folks who may have been opposed to land conservation. “We put sweat equity into being available when people want to come in and talk about the program. Our advisory committee is from a spectrum of backgrounds, and we give them information so that they can go back and speak to their peer groups.”

Tim also advocates for building trust by growing the conservation ethic in the community, and that’s often best done by trying to get people out onto these properties. These may not always be your typical user. “We need to find land for everyone to put their feet on the ground.”

Trust is a local government’s most valuable currency. As Tim puts it. “We all want to see local governments succeed with this. Our success is their success and vice versa. If you see something in our success, take it and run with it. And we’ll use your successes here. We all win together.”

Lessons Learned, Key Takeaways, Guiding Principles.

KEY TAKEAWAYS FROM THE DOCUMENT ARE SUMMARIZED HERE FOR EASY REFERENCE.

1. All transactions must be voluntary, market-based, and conducted at arm’s length with willing sellers. Page 2

2. Effective land conservation strategic plans identify and prioritize lands based on community input. Pages 2 + 3

3. Conservation Values are the characteristics of a piece of land that generate some type of value or benefit to the community. See Figure 2. Page 3

4. These benefits are not guaranteed—without protecting the lands that provide them, they will be permanently lost. Page 2

5. The goal of Greenprinting is for the community to make a fully informed decision on what its future will look like. Page 3

6. The “Line-of-Sight” is a tried-and-true model for developing, launching, and running local programs. See also Figure 3 for illustration. Page 4

7. Typically, these programs are created pursuant to a referendum for several reasons: Pages 4 + 6

a. Land conservation is often viewed as a “nice-tohave” initiative for a government, not a core function.

b. Referenda provide a strong public mandate and long-term support

c. The referendum should be run during a Presidential or mid-term election year to maximize voter turnout.

8. Conservation referenda pass in Florida. Since 1999, 85% (87 of 103) have passed, with average voter support of 64%. Page 6

9. A feasibility study and polling—conducted with NFLT and the Trust for Public Land—is recommended to gauge support under real-time social and political conditions. Page 6

10. Program leadership should be housed in a department with an aligned mission and supported by cross-departmental “strike teams” to manage key functions. Page 8

11. If local expertise is limited, use qualified consultants to strengthen the program’s capabilities. Page 8

12. Land acquisition and stewardship budgets should be given the same consideration as any other essential public service or capital asset. Page 8

13. It is vitally important for a successful program to properly evaluate, accept and reject applications. This is a critical component of the Line-of-Sight model and is the single most important part of a successful program. Page 8

14. Ensure all property assessments are backed by data. Rejection of applications must be justifiable and transparent. Page 11

15. Use evaluation scores to track progress toward protecting properties that reflect the conservation values approved by voters. Page 11

16. Some lands are so ecologically significant that full public ownership is warranted—but not all land must be publicly owned to be protected. Conservation easements offer a flexible, cost-effective alternative. Page 11

17. Conservation easements may be undervalued in scoring models, but they are vital for protecting important lands not available for fee purchase, or where continued private ownership benefits the broader landscape and economy. Pages 11 + 13

18. Establishing a citizen advisory committee builds transparency and trust and significantly increases voter support. This is a defining feature of Florida’s most successful local programs. Page 13

19. No property should be purchased without having been reviewed by the citizen advisory committee. Page 13

20. A core principle of the program should be that no conservation land under its care is allowed to degrade. Page 14

21. To support interim stewardship, traditional land uses—such as grazing, hunting, or forestry—can be appropriate tools for maintaining conservation value while awaiting restoration funding. Page 14

THE NORTH FLORIDA LAND TRUST has extensive experience in these types of strategic planning projects and NFLT staff has more than 30 years’ experience developing and running County land conservation programs. NFLT staff has developed Greenprints for both Nassau and Clay Counties and is currently under contract implementing Nassau County’s Conservation Lands and Acquisition Management Program. NFLT is working with Highlands County to Greenprint their local land conservation program. NFLT’s advice is frequently sought out by staff of new and established programs. NFLT understands the goals of each local land conservation program varies according to the desires of their residents and the elected officials. NFLT customizes the conservation planning process according to the needs of its client community.

PHILOSOPHY: North Florida Land Trust was founded in 1999 and is a land conservation, 501(c)3 organization focused on preserving and enhancing our quality of life by protecting North Florida’s irreplaceable natural environment. We have a core service area of seven counties in North Florida and work on an as-needed basis elsewhere throughout the state.

OUR MISSION: To preserve and enhance our quality of life by protecting North Florida’s irreplaceable natural environment.

WE ENVISION: North Floridians feel more connected to and have a stronger appreciation for our unique native environment. The North Florida Land Trust implements collaborative approaches for long-term solutions commensurate with rapid growth. By protecting more of North Florida’s farms, forests, and natural areas, we maintain traditions, enhance lives, and sustain our expanding communities.

CORE VALUES

We believe…

• We all bring our greatest strengths, and together they add power.

• Our dedication to innovation and new ideas gets results.

• Our dependability and accuracy earn trust.

• Consistently being transparent and honest brings us together.

• Our passion and connection to protecting our natural environment make a difference.

WHAT WE DO: Since its inception NFLT has facilitated the preservation of almost 44,000 acres worth $110 million. Of these, NFLT holds an interest in more than 15,687 acres including more than 5,000 acres of Conservation Easements.

STRATEGIC FOCUS: Our work centers around six Priority Preservation Areas (PPA). These are:

• Osceola to Ocala (O2O) Wildlife Corridor

• Military Readiness and Base Buffering

• Salt Marsh and Climate Resilience

• Springs, Aquifer Recharge and Water Quality Improvement

• Working Lands

• Community Conservation

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION. NFLT will work with communities to acquire funding and property that may not fit into any of the other above-mentioned PPAs – all we need is a willing landowner, willing funding partners, and community support. As a part of the Community Conservation PPA, we offer our Greenprinting service. We assist local governments in developing the means, resources, and tools to protect locally important green spaces, and compete for State, federal, and private funds to purchase property and conservation easements. We can also work as their real estate arm to negotiate conservation deals for them to consider.

GREENPRINTING: NFLT staff possesses extensive knowledge and expertise in local government land conservation, with a strong track record of designing, implementing, and managing effective local programs. Recent Greenprinting work:

• 2018 – 2022: Assisted Nassau County (FL) design its Conservation Acquisition and Management Program, taking that from Blueprint, through 2020 Referendum, to implementation.

• 2022 – Present: Is now the full-time conservation real estate arm for Nassau County handling property evaluations, negotiations with landowners, contract development, due diligence, Citizen Committee and Commission briefings, grant preparation, and strategic conservation planning.

• 2021 – 2023: Assisted the cities of Fernandina Beach, New Smyrna Beach, and Jacksonville negotiate and acquire conservation property.

• 2022 – 2024: Assisted Clay County (FL) develop its land conservation program resulting in the County agreeing to put a $45 million Referendum question to their voters.

• 2024: Assisting Highlands County (FL) develop its Ridge to River Conservation Planning Study.

• 2025 – 2028: Assisting Flagler County implement its Environmentally Sensitive Lands Program.

HOW CAN WE HELP YOU?

Contact us at Info@NFLT.org or call 904.557.798. Visit us at www.NFLT.org.