10 —

N O R TH ER N C LAY C EN T ER

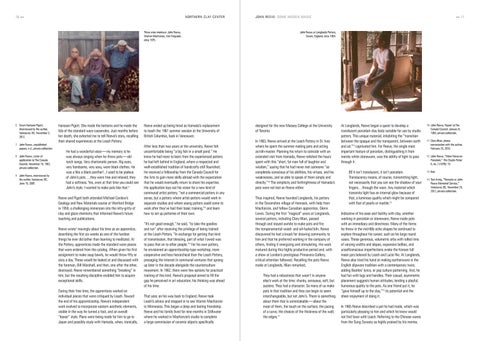

Three wise monkeys: John Reeve, Warren MacKenzie, Ken Ferguson, circa 1975.

6 Gwyn Hanssen Pigott, interviewed by the author, Vancouver, BC, November 3, 2012. 7 John Reeve, unpublished papers, n.d., private collection. 8 John Reeve, Letter of application to The Canada Council, November 19, 1962, private collection. 9 John Reeve, interviewed by the author, Vancouver, BC, June 19, 2007.

Hanssen Pigott. She made the bottoms and he made the lids of the standard ware casseroles. Just months before her death, she exhorted me to tell Reeve’s story, recalling their shared experiences at the Leach Pottery: He had a wonderful voice — my memory is he was always singing when he threw pots — old torch songs. Very charismatic person. Big eyes, very handsome, very sexy, wore black clothes. He was a like a black panther!...I used to be jealous of John’s pots….they were free and relaxed; they had a softness. Yes, even at that time you could see John’s style. I wanted to make pots like that.6 Reeve and Pigott both attended Michael Cardew’s Geology and Raw Materials course at Wenford Bridge in 1959, a challenging immersion into the nitty-gritty of clay and glaze chemistry that informed Reeve’s future teaching and publications. Reeve wrote7 movingly about his time as an apprentice, describing the first six weeks as one of the hardest things he ever did (other than learning to meditate). At the Pottery, apprentices made the standard ware pieces that were ordered from the catalog. When given his first assignment to make soup bowls, he would throw fifty or sixty a day. These would be looked at and discussed with the foreman, Bill Marshall, and then, one after the other, destroyed. Reeve remembered something “breaking” in him, but the resulting discipline enabled him to acquire exceptional skills. During their free time, the apprentices worked on individual pieces that were critiqued by Leach. Toward the end of his apprenticeship, Reeve’s independent work evolved to incorporate eastern aesthetic elements, visible in the way he turned a foot, and an overall “looser” style. Plans were being made for him to go to Japan and possibly study with Hamada, when, ironically,

Reeve ended up being hired as Hamada’s replacement to teach the 1961 summer session at the University of British Columbia, back in Vancouver. After less than two years at the university, Reeve felt uncomfortable being “a big fish in a small pond.” He knew he had more to learn from the experienced potters he had left behind in England, where a respected and well-established tradition of handcrafts still flourished. He received a fellowship from the Canada Council for the Arts to gain more skills abroad with the expectation that he would eventually return to share his expertise. His application lays out his vision for a new kind of communal artist pottery, “not a commercial pottery in any sense, but a pottery where artist-potters would work in separate studios and where young potters could come to work after they’ve had their basic training,”8 and learn how to set up potteries of their own. “It’s not good enough,” he said, “to take the goodies and run” after receiving the privilege of being trained at the Leach Pottery. “In exchange for getting that kind of transmission, that blessing, part of what I owed was to pass that on to other people.”9 For his own pottery, he envisioned an apprenticeship-type workshop, more cooperative and less hierarchical than the Leach Pottery, presaging the interest in communal ventures that sprang up later in the decade alongside the counterculture movement. In 1962, there were few options for practical training of this kind. Reeve’s proposal aimed to fill the gap he perceived in art education; his thinking was ahead of his time. That year, on his way back to England, Reeve took Leach’s advice and stopped in to see Warren MacKenzie in Minnesota. This began a deep and lasting friendship. Reeve and his family lived for nine months in Stillwater where he worked in MacKenzie’s studio to complete a large commission of ceramic objects specifically

JO H N REEVE: SO ME H I D D EN MA G I C

— 11

John Reeve at Longlands Pottery, Devon, England, circa 1964.

designed for the new Massey College at the University of Toronto. In 1963, Reeve arrived at the Leach Pottery in St. Ives where he spent the summer making pots and acting as kiln-master. Planning his return to coincide with an extended visit from Hamada, Reeve relished the hours spent with this “short, fat man full of laughter and wisdom,” saying that he had never met someone “so completely conscious of his abilities, his virtues, and his weaknesses, and so able to speak of them simply and directly.”10 The simplicity and forthrightness of Hamada’s pots were not lost on Reeve either. Thus inspired, Reeve founded Longlands, his pottery in the Devonshire village of Hennock, with help from MacKenzie, and fellow Canadian apprentice, Glenn Lewis. During the first “magical” years at Longlands, several potters, including Clary Illian, passed through and stayed awhile to make pots and fire the temperamental wood- and oil-fueled kiln. Reeve discovered he had a knack for drawing community to him and that he preferred working in the company of others, finding it energizing and stimulating. His work matured during this highly productive period and, with a show at London’s prestigious Primavera Gallery, critical attention followed. Recalling the pots Reeve made at Longlands, Illian remarked, They had a robustness that wasn’t in anyone else’s work at the time: chunky, sensuous, soft, but austere. They had a character. So many of us make pots in that tradition and they can begin to seem interchangeable, but not John’s. There is something about them that is unmistakable — about the meat of them, the touch on the surface, the pacing of a curve, the choices of the thickness of the wall, the edges.11

At Longlands, Reeve began a quest to develop a translucent porcelain clay body suitable for use by studio potters. This unique material, inhabiting the “transition between the opaque and the transparent, between earth and air,”12 captivated him. For Reeve, the single most important feature of porcelain, distinguishing it from merely white stoneware, was the ability of light to pass through it. [I]f it isn’t translucent, it isn’t porcelain. Translucency means, of course, transmitting light, not necessarily that you can see the shadow of your fingers…through the ware. Any material which transmits light has an internal glow because of that, a luminous quality which might be compared with that of pearls or marble.13 Indicative of his ease and facility with clay, whether working in porcelain or stoneware, Reeve made pots with an immediacy and directness. Many of the forms he threw in the mid-60s echo shapes he continued to explore throughout his career, such as his large round vases. These generous, volumetric orbs with rolled rims of varying widths and slopes, expansive bellies, and unselfconscious imperfections evoke the Korean full moon jars beloved by Leach and Lucie Rie. At Longlands, Reeve also tried his hand at making earthenware in the English slipware tradition with a contemporary twist, adding Beatles’ lyrics, or pop culture patterning. And, he had fun with lugs and handles. Their casual, asymmetric placement suggests human attitudes, lending a playful, humorous quality to the pots. As one friend put it, he “gave himself up to the clay,”14 its potential and the sheer enjoyment of doing it. In 1965 Reeve described a pot he had made, which was particularly pleasing to him and which he knew would not find favor with Leach. Referring to the Chinese wares from the Sung Dynasty so highly praised by his mentor,

10 John Reeve, Report to The Canada Council, January 8, 1964, private collection. 11 Clary Illian, phone conversation with the author, February 25, 2016. 12 John Reeve, “More Notes on Porcelain,” The Studio Potter 6, no. 2 (1978): 19. 13 Ibid. 14 Tam Irving, “Remarks at John Reeve Memorial Service,” Vancouver, BC, November 29, 2012, private collection.