If I were to ask you this, what would you say? Would you have an answer? Most people spend their lives searching for one — to feel accepted in their identity, the defining characterization of purpose. I found a piece of it during my time spent in the newsroom at NAU’s Media Innovation Center. There, a sense of belonging sits deep in my chest.

I am honored to work closely with my colleagues at The Lumberjack — who continually challenge themselves to learn from each other and people in the community. Through storytelling, I believe we can make a difference. People are scared right now — and rightfully so. Headlines come out daily about changes to education, community resources, job security, citizenship status, protest rights, civil rights — First Amendment rights.

No law shall be made “respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble…” Every morning, I walk past these words engraved into a large plaque in the First Amendment Plaza outside the School of Communication. And I’m reminded of everyone’s role in creating our nation’s identity and providing opportunities for all.

Within The Lumberjack ’s own little corner, our adviser Katy Locke has selflessly advocated for every student who walks

Brisa Karow | Editor-in-Chief

Victoria Medina | Director of Digital Content

Alycia Stewart | Director of Marketing

Hannah Barrett | Director of Design

Emma Stansbery | Managing Editor

Ava Hiniker | Chief Copy Editor

Katherine Locke | Faculty Adviser

Ryan Williams | Multimedia Adviser

Northern Arizona University sits at the base of the San Francisco Peaks, on the homelands sacred to Native Americans throughout the region. We honor their past, present and future generations, who have lived here for millennia and will forever call this place home.

through the doors of the Media Innovation Center. The door to her office is almost always open, and her presence has been transformative, creating a welcoming environment for many at NAU. It makes a world of difference.

Through her motivation and encouragement, I believe we were able to put together our most important issue yet.

I’d like to thank everyone who shared their stories with us for this issue — ones of resilience, dissent, advocacy and growth. Each have different upbringings, experiences and individual battles; goals they work toward and lights in their lives. Many are fighting for representation, against stereotypes and to make a change. They take up space.

Indigenous drag queens Angel Lust, Anastasia and Planet Cree featured in “Stepping into the Spotlight” show what representation means for their communities. In “We Are Enough,” six individuals share their cultural identity journeys, faced with commentary both within and outside their social circles. “Navigating life with a hidden disability” sheds light on the often unnoticed and misunderstood disabilities many people have and their fight for better accessibility. “Who gets to tell the story?” features an NAU professor teaching critical race theory through art and discussion, amid national criticism of showcasing diverse narratives in education.

I hope you can resonate with the stories captured in this issue and share them with people in your inner circles. Enjoy reading “The Politics of Belonging.”

Brisa Karow, Editor-in-Chief

B risa Karo w, Editor-in-Chie f

Cover Photo: Diné drag queen Angel Lust is one of many performers in Flagstaff and is featured in this issue’s cover story “Stepping into the Spotlight.” Taylor McCormick

Jesselle Ortegon, Victoria Medina, Marcel Herving, Myrah Munoz, Sarah Manning, Abbey Sobelman, Elliott Stringer, Taylor McCormick, Morgan Felker Lewis, Mason Robles, Bryan Adams, Austin Williams, Brisa Karow

Editorial onging.

Corey Stakley, Nay Hernandez, Emilia Mena Garcia, Elliott Stringer, Abbey Sobelman, Jesselle Ortegon, Saige Steele, Mason Robles, Bryan Adams, Austin Williams

Marketing

Maeve Larson, Daisy Johnston, Sara Williams

Victoria Medina, Jesenia Tarango, Alexandra Ray, Anthony Treviso, Taylor McCormick, Yanissa Romo, Jason Maggio, Sarah Manning, Beck Toms, Sal Armijo, Landon Johnson, Caitlyn Anderson, Abbey Sobelman

Alex Porras, Palvan Bugenhagen, Tiffany Hagan, Kiel Amundsen, Hannah Barrett

Phone: (928) 523-4921

Fax: (928) 523-9313

lumberjack@nau.edu

P.O. Box 6000 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 © 2025 The Lumberjack

Table of

Who gets to tell the story?

Are Enough

Solidarity through art

Detoxing from dopamine in the digital age

+

A safe space for LGBTQ youth

Stepping into the Spotlight

Navigating social circles with a hidden disability

Tripping out of Mormonism

The emerging atheltics in Flagstaff’s forest

Story by Jesselle OrtegonPhotography

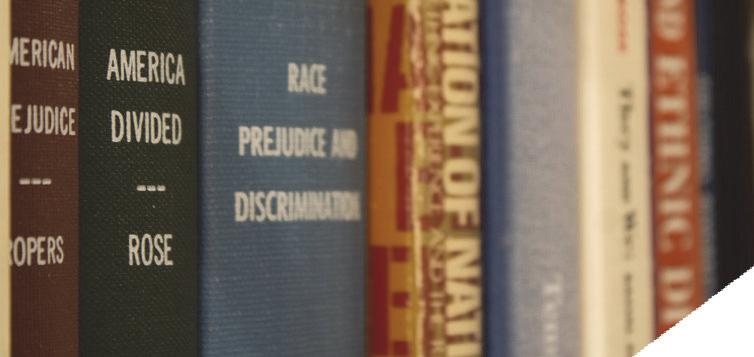

Amplifying history’s overlooked stories through critical race theory

or not, the importance of recognizing marginalized communities in his class.

The critical race theory academic framework emerged in the late 1970s to address how systemic racism has shaped society using the untold stories of non-white Americans.

Critical race theory encompasses many voices, ideas and arguments, making it difficult to pin down exactly what it looks like in the world today. However, one way students can begin to recount past injustices is telling counternarrative stories that amplify the experiences of marginalized people otherwise erased in American history.

The 2006 film “Walkout” is an artistic representation of the way critical race theory uses storytelling to approach topics of diversity and culturally sensitive learning.

“Walkout” is based on the true story of a group of Chicano students who protested against academic prejudice in East Los Angeles schools in 1968. With the assistance of Mexican American activists Sal Castro and Paula Crisostomo, the students stood up for the right to learn about and embrace their Chicano culture.

Pedro Cuevas, an assistant teaching professor in NAU’s Department of Ethnic Studies, uses the film in his classes as an example of recognizing the importance of different stories in a marginalized culture.

He centers his curriculum around reclaiming and recognizing the stories of oppressed peoples, specifically Latinos.

In Cuevas’ Latino and Chicano studies class, his students worked on a murals project for a community art showcase that opened for viewing in March. Painting murals was part of the 1960s Chicano Movement to depict the stories of Mexican American culture through symbolic, detailed art displayed on city buildings, schools or churches.

Instead of attending traditional in-class lectures, for two months, students worked in groups to create art in a medium of their choice — mainly murals — that symbolized the stories of Latinos and Chicanos that were overlooked.

Cuevas said his students practiced critical race theory through their participation in this school project because they elevated the stories and struggles of Latinos and Chicanos in history in

the form of art.

“Reclaiming those counternarratives is a way of creating a much healthier, stronger understanding of all people,” Cuevas said. “By elevating all these narratives we haven’t seen or heard, it’s like putting all the pieces to the great puzzle of humanity.”

Cuevas teaches ethnic studies to highlight the importance of history and humanize the stories critical race theory recognizes.

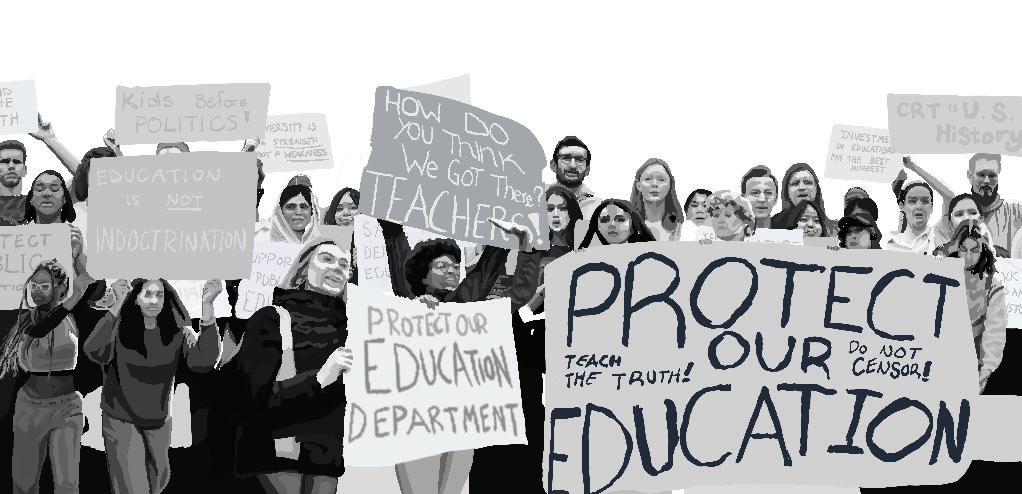

Although the theory is typically only taught in college, the Trump administration is pushing to ban topics embedded in critical race theory in K-12 education. In a January executive order, “Ending Racial Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling,” President Donald Trump’s called for schools in the United Statesto remove “wokeness” and “left-wing indoctrination” content from their curriculum.The president threatened to defund schools that teach topics he considers “critical race theory, transgender insanity and other inappropriate racial, sexual or political content.”

College students learning about critical race theory argue Trump’s patriotic ideals for education do not allow for diverse perspectives and fail to recognize different cultural narratives the way critical race theory does.

Brianna Cardenas took Cuevas’ class last semester and is now a teacher assistant for him. She said it taught her the importance of embracing the teachings that Western education fails to.

“We, as in marginalized communities, are the majoritarian narrative and Western colonizers are the counternarrative, but the system is twisted to make us believe that we are the counter story,” Cardenas said. “In reality, it was Indigenous people who were here first, their story, their lives, that all came first. Not the Western norms.”

The way American history is taught to students in the U.S. is different from other countries, she said. If it were not for the few standout teachers she had in high school, Cardenas might have had a narrow knowledge of history.

After taking Cuevas’ ethnic studies course, Cardenas realized the negative news coverage about critical race

theory was misleading.

“In the news, people think it is teaching our kids to be racist,” Cardenas said. “Implementing that patriotic aspect of education and excluding everything else does students around the country a disservice and doesn’t set them up for what they experience in the real world.”

Cardenas said counternarratives are essential to education and life in general because they open students up to various perspectives. It can be as simple as a teacher going around the classroom and asking each student to share something about themselves, an activity Cuevas leads at the beginning of his class. This small act can make a student in a room of 30 feel seen and not like just another face in the classroom, Cardenas said.

For Cuevas, the interconnection of giving his students a voice and celebrating everyone through storytelling is important to him. Becoming an ethnic studies professor allowed him to do so.

Cuevas has taught for 30 years at every level. His first experience with critical race theory was 25 years ago in Northern California when he was a professional actor teaching inmates

how to act and write original plays. The people he worked with at the time were labeled as at-risk groups, or inmates considered resistant to rehabilitation services. Cuevas said encouraged the incarcerated people to think in a way that offered alternative endings to their stories rather than allowing them to sustain the belief that their futures would only entail jail or prison.

Correctional systems can be dehumanizing, so Cuevas focused on how art can humanize a number of experiences — similar to what he does as a professor. By working closely with inmates, Cuevas realized the young men and women in jail were just kids who fell through the cracks of the educational system. This epiphany inspired him to further pursue education.

“There are a lot of inequities in our education system where marginalized communities don’t have an equitable opportunity

to get an education and elevate themselves and be successful and contributing members of society,” Cuevas said. “It was clear to me that these were the students just like myself that met up with these low expectations when they were in school.”

When Cuevas was ready to move on from acting, he brought what he learned from his time teaching inmates in jail into the classroom. He said counternarratives naturally integrated into his teaching since he has always had a passion for storytelling.

“Stories matter, everybody’s stories matter,” Cuevas said. “‘Why can’t we share our stories and learn from one another?’”

Taking an ethnic studies class and learning about critical race theory encouraged Cardenas to take on a minor in ethnic studies. She said Cuevas’ emphasis on sharing his stories was empowering for her as a student and future educator.

Cardenas said anyone who does not understand critical race theory should take a class with Cuevas to experience it firsthand.

“In that class, you’re not even talking about critical race theory as it is, but you’re essentially practicing it in a way that makes it so clear that critical race theory is involved in everything we do in life,” Cardenas said.

In Cuevas’ classroom, he teaches his students to humanize their experiences through art, music, language and human connection to bring the beauty of all cultures to life. His students are immersed in the practice of elevating marginalized stories in a way that is creative and allows them to connect with their peers.

“I think the most important thing an educator can do, from pre-K to doctorate level, is to create a safe, inclusive space where everyone’s, their narrative, their history, their identity is welcomed and celebrated,” Cuevas said.

Raised without Filipino traditions and values, Faith Townsend

Navigating identity through differing cultural expectations

Growing up surrounded by traditions, immersed in ancestors’ customs can be a key factor in connecting with one’s culture. However, if these connections are not built during childhood, it can impact one’s identity and relationship with their culture in the future. The disconnect can lead to a lack of pride and feeling like an outsider within one’s community.

Freshman Faith Townsend, media and marketing intern for NAU’s Filipino American Student Association (FASA), experienced this divide when she first joined the organization.

Most members in FASA were brought up with “tiger parents” who were strict with their schooling and upbringing. Many are STEM majors who specifically study nursing. Townsend is majoring in animation.

She moved to Arizona when she was 12 to live with her white dad and Filipino stepmom, neither of whom raised her with Filipino values or customs. Townsend felt out of place compared to FASA’s other members.

“I feel like a lot of people in FASA listen to the same type of music and they like the same sort of things and were interested in the same subjects in school,” Townsend said. “I would kind of try to morph myself into that … because I wanted them to think that I was more Filipino.”

Townsend later found many in FASA similarly had vulnerabilities and struggles regarding their identities, despite growing up surrounded by Filipino culture.

“I know a lot of Filipinos [who] are half white that struggle with their identity, and you wouldn’t think that I could relate to them, but I really do,” Townsend said. “I look Filipino, but I don’t feel Filipino sometimes.”

Seeing many other Filipinos who went through similar experiences was eye-opening for Townsend. She learned she was not alone in wanting people in her culture to accept her so she could feel like she belonged.

The more time she spent with the FASA community, Townsend began to evaluate her view of her culture and herself.

“I feel like I don’t need something external to tell me that I’m Filipino,” Townsend said. “I can derive that from within myself. I’m a lot more confident to say that, ‘Yeah, I am Filipino.’”

Becoming familiar with and accepting one’s heritage is an inner battle many face, especially when raised with multiple lifestyles.

This is true for junior Ayejah Rivera, president of NAU’s Latine Student Union (LSU), who grew up with separated parents. Her dad is Salvadoran and Puerto Rican and her mom is from the United States. When spending time at her dad’s house, Rivera was immersed in Salvadoran and Puerto Rican customs, different than when she would stay with her mom. Rivera said she endured a push-and-pull from both sides of her culture.

“There’s this middle ground where you’re not Latina enough for your Latine side and you’re not white enough for America,” Rivera said.

She was raised to take pride in her Salvadoran, Puerto Rican and American identities. However, this does not mean she does not seek validation from others.

Rivera’s grandmother, Nelly Rivera, immigrated from El Salvador to the U.S. and faced difficulties as she came into the country. Similar to her grandmother who was determined to make something new for her family, Rivera seeks to add value to her community in honor of her grandmother.

During her time as president of LSU, Rivera made it her mission to support other Latine and Hispanic students through club activities. One event Rivera put together was a tortillamaking night, where members learned about the Aztecs, the origins of tortilla ingredients and how they are connected to the culture. Rivera hosts such events to help LSU’s members feel at home and create a supportive community at NAU.

“I think learning from other cultures is always going back to that pride and remembering your history, like what it means for you to be part of a place or community,” Rivera said.

Those within Latine and Hispanic communities have been confronted with racist remarks to “go back to where they came from.” Rivera said the common resilience of Latine culture shows their oppressors they are here to stay.

Black people in Westernized nations like the U.S. and Europe often feel alienated from their cultural origins.

The transatlantic slave trade is a large factor in their erasure, removing individuals from their ancestry and forcibly assimilating them to Western ideals.

Regardless of generational struggles, Black people have found a way to survive in the country. Black culture is imbedded in U.S. culture, and their resilience shapes language, art, music, fashion and education today.

The grit of Black Americans goes beyond culture; resilience is ingrained within the Black community. This mentality spanning generations invigorates Black Americans to pursue self-determination.

Wendy Alexia Rountree, senior professor and director in the Department of Ethnic Studies, understands what it means to be

foundations of the English language and Western culture are built on oppressing people of color, with “proper speech” viewed as a stereotypically “white” characteristic. Black people are labeled unintelligent when they use AAVE due to nonconformity with Eurocentric languages.

According to the University of Nebraska at Omaha’s Journal of Curriculum, Teaching, Learning and Leadership in Education, the stigma of language use makes many Black Americans feel that around white people, they must choose between acting sterotypically “Black” or sterotypically “white.”

Rountree had friends to rely on to cope, but still feels the effects of bullying decades later.

“You never get rid of it,” Rountree said. “You never do. It stays with you a little bit. But again, you have to grow through it, and at least, that’s what I’ve tried to do.”

Before teaching at NAU, ethnic studies professor Wendy Alexia Rountree taught at Salisbury University, a predominately white institution. Rountree said she was likely one of the only Black professors at Salisbury. Then, she got a position at North Carolina Central University, a historically Black university, where she reconnected with her Blackness, surrounded by students and colleagues with shared cultural identities. Victoria Medina

Black in America.

“When you’re dispersed, you lose that connection, and you lose that sense of kinship,” Rountree said. “If you’re not careful, then those who disperse you win.”

Growing up in Kingston, North Carolina, she lived and breathed Black culture, educated on the Black experience by her parents and the Christian church fellowship in her hometown.

Through communal effort, older generations within her neighborhood worked together to uplift Rountree’s education, igniting her love for literature and learning.

“It takes a village,” Rountree said. “Yes, there were many village members. I think that helped to build me up.”

Despite support from her community, Rountree faced hardship once she reached adolescence. She was bullied, her Black peers scrutinizing her for “acting white” due to her speech patterns.

Jaylin Nesbitt, who wrote a master’s thesis in May 2022 titled “Writing while Black: African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and perceived writing performance,” said the

Rountree’s first teaching job was at Salisbury University, a predominantly white institution. She said she felt a mix of excitement and doubt during this time. Rountree realized she was most likely the first Black professor both her Black and non-Black students had. She took that as a challenge.

Although Rountree was burdened with the thought that she was not enough for the university, she took pride in her position as a Black woman in higher education.

Rountree later taught at North Carolina Central University, a historically Black college or university (HBCU) established to create educational opportunities for Black Americans. There, she found the cultural connection and support she did not have before. This recentered her in her Blackness.

“I actually believed my time at the HBCU was almost like a healing period for me,” Roundtree said. “Particularly the early years because I think it helped answer some questions that I had, even for myself.”

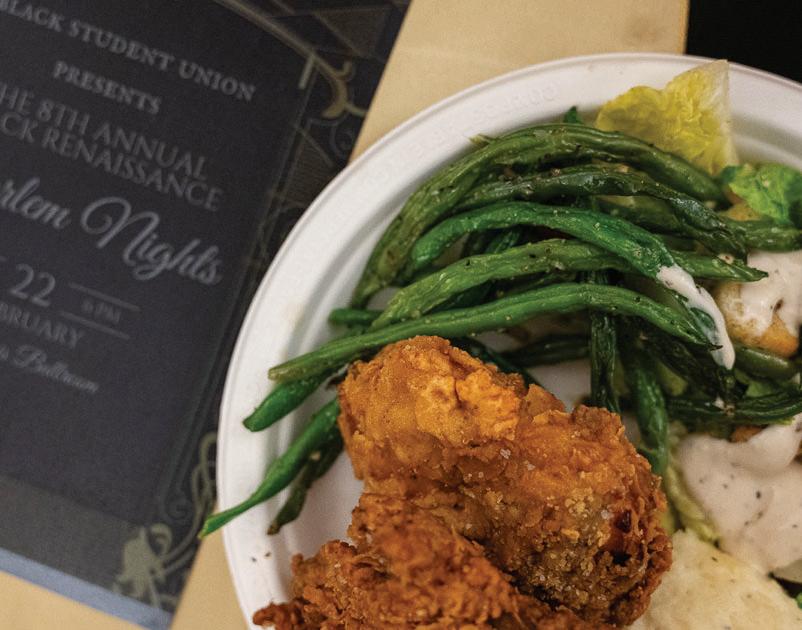

Black students create spaces to feel safe and welcome within institutions — a home away from home.

Outside his work with NAU’s Campus Living, fourthyear doctoral student Cosmos Saviour Ansah is president of the African Students Association (ASA). Born and raised in Ghana, Africa, he took an interest in international politics, graduating from college and traveling to the U.S. in 2021 to pursue a doctorate in political science.

ASA is an organization created for students from Africa or of African descent to feel connected with other students and their African roots — no matter how far removed. The group helps international African students navigate American college life, aiding in aspects like housing and homesickness.

“I’ve had instances where people come in, and within a month, they’re like, ‘I want to go back home,’” Ansah said. “So, we try to deal with those challenges.”

Arriving in the U.S., Ansah experienced forms of antiBlackness and xenophobia, with comments about his accent — sometimes told to “go back to his country.”Although he built a support system with his parents in Ghana, talking to other international students and making connections through ASA helped him cope the most.

Ansah witnessed infighting across the Black diaspora, with stereotypes of Africans and African Americans thrown both ways. He recognizes from his experiences these stigmas spread through the internet. Ansah views this as a matter of perception — a lack of education skewing the view Black people have of each other.

Creating close ties with Black people across the diaspora, most notably students affiliated with NAU’s Black Student Union, Ansah and other ASA members helped bridge the gap.

Despite his ongoing journey navigating his Blackness and African identity within higher education, ASA has been a safe haven for Ansah where he feels the least pressure to conform to American ideals.

“I don’t have to worry about how I’m speaking,” Ansah said. “I don’t have to worry about if the other person can understand, because I know they do.”

said she receives criticism from her Hopi community for her pale complexion. For her, one appearance, but by their

The Pacific Islander label encompasses many different ethnic groups and nationalities. However, as a Pacific Islander removes themself from their home region, they can find it becomes isolating and difficult to hold onto their culture, especially while living in a Western-dominated society.

Palik Rilmentos is a Flagstaff local who graduated from Tulsa Welding School a year ago. From the Micronesia region — a large group of islands east of the Philippines in the western Pacific Ocean — Rilomentos always felt he did not belong in his community. Being away from most of his extended family and the home of his tribe only worsened the problem.

“Part of it was not knowing the language very well,” Rilmentos said. “You receive a lot of criticism from the older generations.”

When he returns to the Marshall Islands, Rilmentos finds that his mother constantly acts as a translator when he speaks to his relatives. Because of this indirect communication, he said he feels like an outsider compared to his cousins, who stayed close to home.

“My cousins from back on the islands often like to tease me, calling me ‘whitewashed,’” Rilmentos said.

the U.S., so Rilmentos had more knowledge about his father’s culture than his mother’s. Despite their different ways of life, Rilmentos’ parents have supported him in finding his cultural identity to the best of their ability.

“One time, I had to cook for a wedding,” Rilmentos said. “My dad told me that it was time for me to go make my name out there, meeting family, fulfilling that role in my culture so I fully understand why I am doing it.”

Rilmentos finds it difficult to learn and engage more with his cultural practices due to limited opportunities. There are few places nearby with a large population of Pacific Islanders where people can practice cultural traditions or ceremonies. Some of his extended family moved to Tucson, which is the closest community he can connect with. On his father’s side, he experiences shared values, art, customs and voices.

His parents are from two separate ethnic groups, Ebey and Pohnpei. Although the two are from different islands, they share a lot in common. However, their native tongues are not the same, so attempting to understand and speak two other languages alongside English was challenging for Rilmentos.

On his father’s side of the family, relatives chose to live in

“It takes the tribe to raise a child because it was not just my parents who were teaching me,” Rilmentos said. “Everyone has a role to play to keep our culture alive.” ands, translator se of this s like an o n e nd was chose to live in where cerem to T ca exp vo a R is di in as th tr bec were t has

Although navigating his cultural identity in a Western-dominated society is challenging, Rilmentos said staying connected to his roots is crucial. Despite language barriers and distance from his homeland, he participates in small cultural practices. He said he hopes as Pacific Islanders settle in more areas, there will be greater opportunities to share traditions with future generations.

Many young people who want to stay connected to their heritage — but feel ashamed or dismissed by their community — experience significant discomfort.

The Hopi Nation is a prime example of how traditions are used to reinforce the values, beliefs and collective identity of the community. Before becoming a member who can participate in sacred ceremonial practices, people from the tribe must first go through an initiation.

The culture encompasses 12 villages throughout multiple mesas, each distinct in their initiation ceremonies and traditional practices.

Kayla James is from the Tewa Village, she is Spider/Bear Clan and her Native name is Tay-Kah-La. James has lived in Flagstaff her whole life and does not always feel confident about her cultural identity. The Hopi Tribe values and protects its sacred spaces and ancestors’ life stories to eventually pass them down along generations. For the tribe, there is a clear line between those who are in and those who are out based on its rules of initiation.

“Once you are initiated, it’s like a right of passage into

adulthood, holding certain obligations you are responsible for,” James said. “However, if you do not look a certain way, there seems to be a lot of backlash or gossip about the individual.”

While James’ parents are from Tewa Village, she grew up spending time with her grandmother, Maudine James, who lived in the Village of Polacca on First Mesa. She said she has witnessed people in the village who look down on Hopis with a paler complexion, questioning whether or not they belong.

“There was this one girl who was half white and half Hopi,” James said. “No one really was welcoming to her due to her pale complexion and unfamiliarity of family history from the mesa, which actually pushed her away.”

She is constantly reminded by elders that it is important to learn and educate herself about Hopi culture. The Hopi are one of the smallest tribes in the world. According to the 2020 U.S. Census Bureau, the Hopi have a total population of around 6,000 people.

“Not living on the Hopi Reservation prevents me from participating in many cultural practices,” James said. “I feel limited when trying to engage in ceremonies that are so central to our way of life.”

Hopi people who live far from the mesas often struggle with wanting to continue their traditions, customs or using their language. The obligation to make it to all of these ceremonies is overwhelming, James said, as they happen almost every weekend in the winter and spring.

In February 2024, however, her grandmother passed away, and James said it made her feel more disconnected from her culture.

“When my grandmother passed, it got worse,” James said. “She was the one who taught me about our traditions, and without her, I feel lost trying to hold onto them.”

James is committed to attending these traditional ceremonies and actively participating in her cultural practices. She is persistent in driving almost three hours, enduring long days and nights, preparing large amounts of food as offerings and memorizing dances to help enrich her understanding of her culture.

“Being Hopi isn’t defined by what you look like, it’s about the heart, the heritage, your spirit,” James said. “But sometimes, no matter how deeply your roots go, others only see the surface, making you question if you truly belong.”

The Anasazi Inn at Gray Mountain is part of the Painted Desert Project, on State Route 89A. The Native message on the side of the building is about stolen land.

By Sarah Manning

In a region marked by political tensions, there are spaces where individuals communicate their thoughts, opinions and affiliations rooted in culture in northern Arizona. The art creates a visual dialogue that fosters an unspoken sense of solidarity among those who might otherwise feel unheard.

Alleyway walls, buildings and underpasses in northern Arizona are painted with messages of protest, political stances and unanimity. The artwork from activist groups and commissioned artists represents Flagstaff’s local activism, embodying dreams and concerns within the city.

Táala Hooghan Infoshop, once a space for an anti-colonial and anti-capitalist Native community space in east Flagstaff, closed its doors in spring 2024. Now, the building stands as a gallery for Indigenous activism. Messages such as “Protect the Peaks” and “Haul No!” represent larger land sovereignty movements within Native culture.

The Haul No! movement’s

symbols can be found across northern Arizona from stickers to wall art. The activist group protests the continuation of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation. Haul No! spreads the message about the harm caused by mining and how it affects nearby communities and the environment, which can include local water sources with high levels of heavy metals.

Heading north of Flagstaff, statements through history canvas abandoned buildings and trading posts. Once a busy pit stop along Route 66, the Twin Arrows Trading Post is now a destination for selfexpression. Messages in vivid color layer the deserted infrastructure, with almost every inch of space covered.

Anasazi Inn at Gray Mountain, located north off State Route 89A, is home to the Painted Desert Project. The vacant inn now serves as a colorful landmark on the highway, with alluring hues and photographs — printed with wheat paste. Interactive murals show the importance of clean drinking water. Motion-activated speakers attached to the top of the old overhang of the gas station play sounds of running water amid the dry desert land.

Over time, the brain becomes accustomed to the dopamine release caused by social media. It requires a higher screen time for the same level of satisfaction, which causes decreased pleasure in

On an unusually warm winter day in February, Lucy Truett sits at a table outside the DüB Dining District with her phone face-down in front of her. She never looks at it except to check her screen time average, which has decreased by more than three hours from the previous month.

Although she still jokes and gesticulates like many members of Generation Z, Truett has kicked the addiction many her age hope to free themselves of: her phone.

Truett, a junior majoring in environmental and sustainability studies with a minor in journalism, deleted all her social media accounts in January after suffering from a concussion that prevented her from using her phone. Now, her daily screen time average sits just under two hours and consists almost entirely of her messaging app.

“If five hours of screen time is low, that’s five hours of my day,” Truett said. “I know people who can have social media and also have interests and hobbies, but I did notice that it got to the point where I was not doing things I was really interested in anymore, especially in my alone time.”

Like a casino slot machine, social media is designed to keep users engaged and wanting more.

According to a study on social media addiction published in January by Cureus, a peer-reviewed medical science journal, specially curated algorithms create a dopamine loop by flooding the brain with feel-good chemicals when a user receives a like, comment, share or encounters content tailored to their personal taste. “Social Media Algorithms and Teen Addiction: Neurophysiological Impact and Ethical Considerations” found the consistency of these interactions is uncertain, and the unpredictable nature of the algorithm leaves users searching for more, aided by the endless stream of content on platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

Over time, the brain becomes accustomed to the dopamine release caused by social media. It requires a higher screen time to achieve the same level of satisfaction, which causes decreased pleasure in offline activities.

Nora Stefani, an assistant teaching professor and researcher in the School of Communication, said social media can be good for gathering feedback from others while also creating a dangerous cycle of engagement when users are in search of validation from peers.

“The internet is a great place, for good and ill, to get somebody else’s opinion in a quantifiable way so you can evaluate ‘Am I getting the engagement that supports that on social media? Let me stare bug-eyed at my numbers and try to confront and watch,’” Stefani said. “That could give some people comfort and a sense of confidence, but it can also become a thing where you start trying to quantify yourself.”

To combat the relentless social media time suck, a rising movement of young people including Truett are embracing “slow living” to create a more mindful, sustainable and present lifestyle with reduced screen time.

For Truett, this means shifting the types of media she consumes rather than completely cleansing herself of it. While she still occasionally checks Instagram on her laptop, she has found time for more enriching forms of entertainment like reading, cooking and watching long-form video content to retrain her attention span.

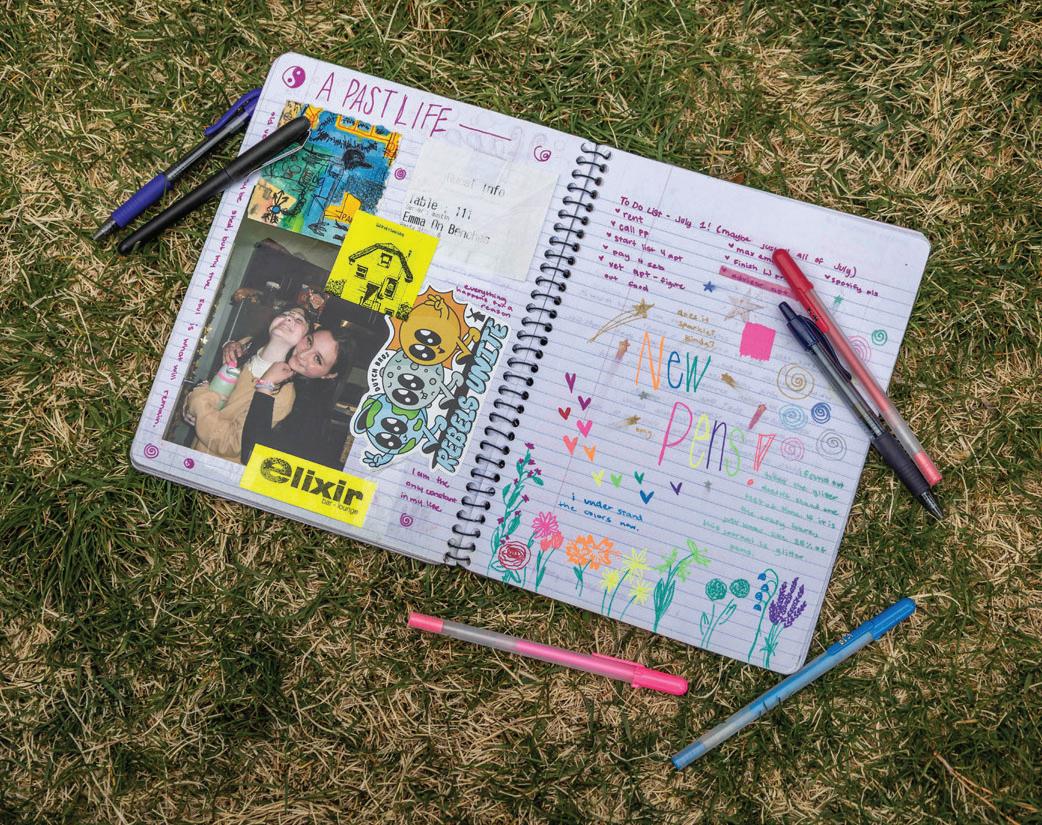

Spending time away from her phone has strengthened Truett’s commitment to her creative hobbies. Although she journaled and drew prior to her media shift, she said she often hurried to finish projects to spend more time on her phone. Now, she forces herself to be more intentional with what she creates.

“Why am I so afraid of spending time on something?” Truett said. “We’re all taking in so much all the time… I know that I’ll learn more and I’ll benefit very genuinely from taking the long

route and sitting here and doing this.”

Like others embracing a slower way of living, Truett said it is important to establish hobbies, whether they be creative, physical or mental. Hobbies encourage creative thinking, problemsolving skills and real-world abilities, allowing for self-exploration, according to a 2021 study published in an international medical journal, Lancet Psychiatry.However, an earlier study published in the Cureus Journal of Medical Science in 2017 showed young adults have been spending less time on in-person social interactions, reading and other offline activities since the rise of digital spaces.

Truett said one of her professors encouraged her to start a blog on Substack, which, like journaling, has become an essential outlet to express her thoughts. She said it feels more meaningful and authentic than the curated, photo-centric landscape on social media.

“I wanted that kind of creative outlet to find a way to promise myself and challenge myself to be honest and vulnerable because I think that’s what’s missing from social media,” Truett said. “Having it not related to what I look like and just be what is churning in my brain has been a really good outlet that is much more fulfilling than posting on my ‘Close Friends’ story.” Spending time on her creative outlets has strengthened Truett’s pre-existing relationships with family and friends. When Truett started her blog, her mom was inspired to write her own creative pieces. Instead of lying in bed mindlessly swiping between apps, Truett chose to read in her living room and connected with her dad over their respective books.

Despite its emphasis on digital mindfulness, slow living does not encourage a complete media detox; it focuses on intent. While social media use can affect a person’s mental health and creativity, it has the potential to foster support networks that increase resilience and feelings of social belonging when used in moderation.

Nora Stefani, an assistant teaching professor at the School of Communication, said social social media. Anthony Treviso

Stefani said she grew up participating in both online and inperson fandoms, one of which is for “Star Trek.” Through social media, she created meaningful connections that she said made her feel more confident in her interests without fear of bullying.

“I think it’s a really untapped and misunderstood space for people to figure out what their values are and to come up with a clear, positive identity,” Stefani said.

Lindsay Afton, who grew up with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, often also felt isolated from her peers. She found solace in reading books and listening to Taylor Swift, and at age 10, she created an Instagram account to find like-minded people.

Afton said she used fan accounts to forge friendships she still maintains today. After preserving a friendship for more than a decade, she met an online mutual from middle school at the opening weekend of Swift’s Eras Tour in Glendale, Arizona, in 2023. Another friendship helped her explore her identity as a lesbian and taught her about queer and lesbian history.

“Learning that has really made me feel more like myself instead of losing part of myself, which I think some people do online,” Afton said. “I feel like I’ve found myself in a way that I would not be able to without the internet.”

She said online exploration has allowed her to feel more authentic in her day-to-day life. Her clothes better represent her

Journaling is a creative hobby that can reduce stress and encourage problemsolving skills.

sexuality, and she is unafraid to tell people about her interests.

However, Afton understands not everyone has had the same experience online. She said social media can negatively impact how people view themselves, their interests and other users, but it has too many worthwhile features to write it off completely.

“It’s up to individual users to draw the line for themselves, which isn’t a skill that’s taught to us,” Afton said. “I think there are too many pros for social media and the internet to just talk about the negatives because the negatives all have a solution.”

Stefani said it was crucial for her to find space for her interests outside social media. Relationships she maintained online also manifested in her daily life, and online skills turned into tangible projects.

Truett looks for a balance between time spent online and time spent forming human connections and consistent hobbies.

“Nobody has taught us how to have boundaries with social media because our generation is the first to really be raised on social media,” Truett said. “We will find balance because we have to, because we are suffering, but we’re also the first generation to be facing all of this crazy stuff available right at our fingertips. It’s hard not to just be addicted to it.”

Junior Lacey Meyers uses her phone as a reference while watercolor painting during an Art Club meeting. Anthony Treviso

The caret blinks in and out of focus. A blank text box glares intimidatingly. Staring at the computer screen, it feels impossible to conceive a true answer to the question on the screen.

“What are your hobbies?”

Many people say hobbies are essential to living a balanced life, but it can be difficult to dedicate time to leisure when technology and work consume our daily routines. To combat the fast pace of social media, slow living encourages people to spend time on calmer and simpler activities.

The “three hobby theory” is a common guide to finding balance in life, with many sourcing it online as a solution to selecting a range of hobbies. While there are different applications of the theory throughout history, most versions in recent years suggest individuals should have three hobbies: one to stay active, one to make money and one to exercise creativity and stimulate the mind. Engaging in fitness, finance and creativity opens doors to opportunities for self-improvement and can lead to a more fulfilling lifestyle.

While many people stay active to maintain their health, working out may not always feel pleasurable, and the gym can feel like a chore.

Hiking, dancing, team sports or martial arts, for example, improve physical health and have been shown to release endorphins, reduce stress and improve sleep and self-esteem, according to a Mayo Clinic article published in March titled “Exercise and stress: Get moving to manage stress.”

Physical hobbies can be scheduled like signing up for pilates or as simple as walking through a neighborhood, but activities that are both pleasurable and habitual have the potential to improve one’s quality of life and increase their lifespan.

According to a 2024 study conducted by One Poll, an international market research company, 40% of Americans have a side hustle, secondary job or activity that provides extra income. A side hustle or freelance job has the ability to supplement income and encourages financial security.

For some, money-making hobbies such as writing, tutoring, babysitting, dog-walking or entrepreneurship can provide an outlet for passion projects. For others, it can generate networking opportunities or the chance to meet new people with similar interests.

It is not important to excel at an art form, but it is important to create. The outcome of the process does not matter so long as the activity stimulates the mind and encourages self-expression.

Creative hobbies include activities with tangible outcomes, such as painting, cooking, woodworking, journaling, knitting or photography, and intangible outcomes like playing an instrument or acting in a play.

According to a 2022 study shared by the National Library of Medicine about leisure activites’ connection to improved health, these activities offer many benefits, including stress reduction, enhanced self-confidence and reduced loneliness. In addition, hobbies with both tangible and intangible products encourage problem-solving skills and resourcefulness, which can be applied to other real-world situations.

Day-to-day life may not always encourage creativity, but the art of creating promotes a well-balanced life.

Noncreative hobbies that stimulate brain function can also be beneficial to well-being. Puzzles and reading can improve memory, concentration and attention to detail and provide a sense of accomplishment when finished. When feeling stuck, introducing any number of these diverse hobbies to your lifestyle can encourage your activity, mental stimulation and financial security.

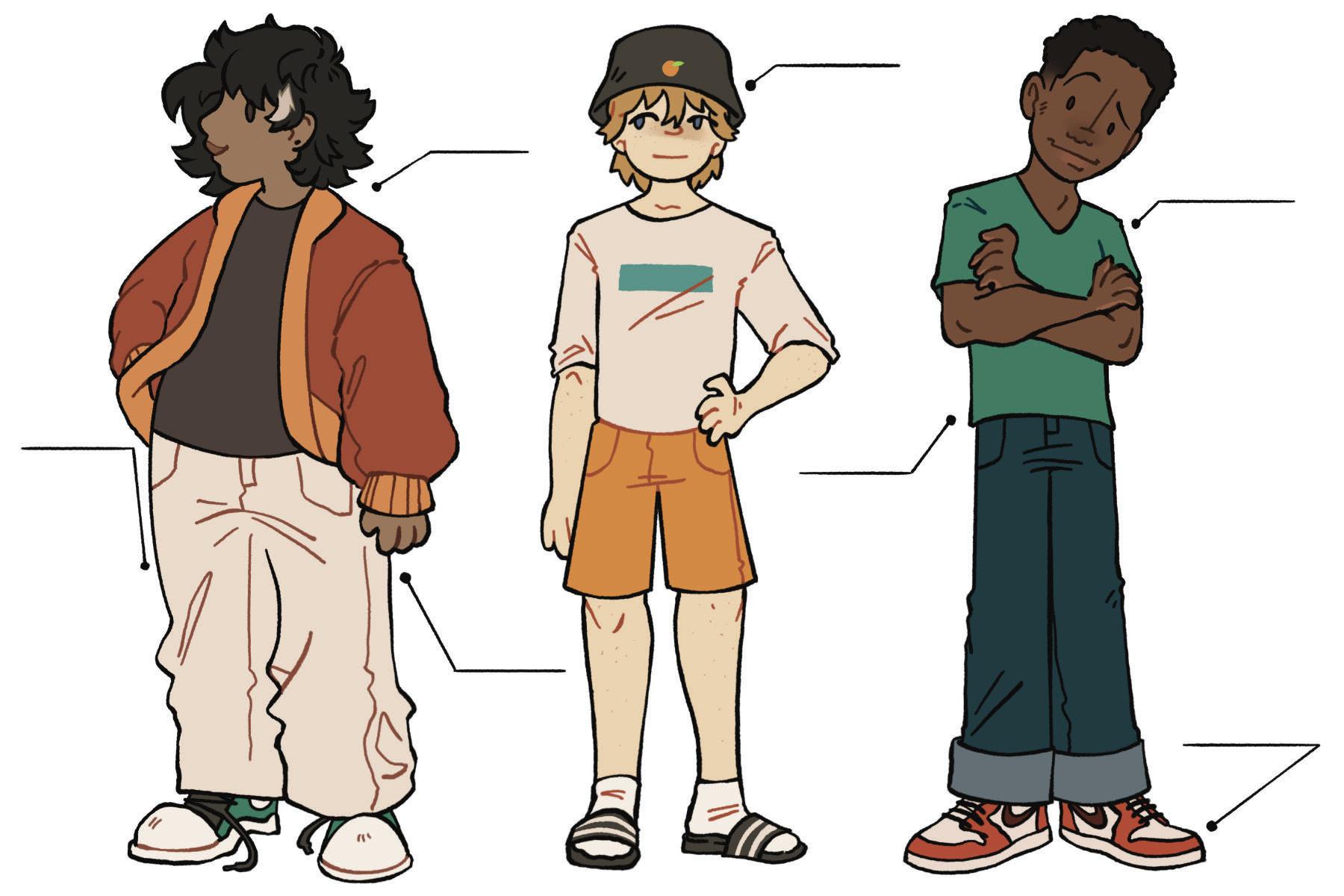

Story by Elliott Stringer

Illustrations by Kiel Amundsen

by Beck Toms and Sal Armijo

About one in 10 people in the United States identify as LGBTQ+. According to a 2024 Gallup poll, the number of queer people coming out has steadily risen since 2012, with the total percentage of openly queer Americans rising 5.8 percentage points in this 12-year timespan. That means more queer people are seeking resources and support while they navigate the process of self-discovery.

Mae Baker moved from Tucson to Flagstaff in 2019 feeling lost and isolated.

While she initially planned to pursue a degree in psychology at NAU, she took a break from school to focus on her identity and career goals, a break that became a longer period of introspection once the COVID-19 pandemic left Baker quarantined in her room.

Confined to her home and online spaces, Baker said she began to struggle with gender dysphoria and lacked a support network to help her understand why.

“I hardly knew anyone else who was queer or especially trans,” Baker said. “I was just feeling very lonely.”

Baker eventually found the support she was looking for while scrolling through Facebook. One queer youth group promoting free events for connecting with LGBTQ+ locals intrigued her, but she said it was difficult to gather the courage to attend its regular meetings.

Once she took a chance on the organization and stepped into rainbows and banners — Baker said she felt comfortable meeting new people, making connections and learning about her identity,

group of volunteers founded one·n·ten in 1993, a time when queer movements were combating the residual homophobia sparked by

The organization offers housing assistance, support groups and

The Flagstaff location, operated by two volunteers and a coordinator, provides a space for locals to explore queer topics the exact locations of their meeting spaces private to protect the

Before every group session, members discuss guidelines for

Meetings tend to follow themes of queer empowerment, whether that is talking about queer artists and history or planning trips around Flagstaff to laser tag arenas, thrift stores and Lowell

Rebecca Osier, the Flagstaff one·n·ten coordinator, said her goal for the group is to build a place where people can educate

“We want to build resiliency and connection and community but also talk about things that aren’t being talked about,” Osier

Volunteer Karen Cahoy, or “Gran” as the group calls her, said she started volunteering because she wanted to facilitate resource

One·n·ten volunteer Karen Cahoy, or “Gran” as the group calls her, said she joined the organization to advocate for and provide resources to queer youth.

More than 20 years ago, her son came out as gay in a small rural her options and chose to volunteer with one·n·ten because it knowing that you’re a part of something more than just yourself,” seem to be much in the rhetoric in the political atmosphere of

January aimed at queer individuals, from rescinding previous orders advocating for LGBTQ+ equity to threatening to punish

marker nonbinary and other genderqueer individuals use, is no York Times reported “more than 1,800 transgender, intersex

Civil Liberties Union with inquiries/concerts about passport

is often expensive and, in some states, near impossible, without research group, eight states require both a court order and proof from a physician — to change the gender recorded on a birth

One·n·ten assists with legal matters, paying for court documents

A tin of pride pins for one·n·ten members to keep, trade or hang up is accessible during group meetings.

“Love Who You Love” Tow’rs

“The Giver” Chappell Roan

“mars” YUNGBLUD

“She Likes Girls” Metro Station

“Don’t Stop Me Now” Queen

“The Village” Wrabel “Home” Cavetown

“Take Me to Church” Hozier

“Jenny (I Wanna Ruin Our Friendship)” Studio Killers

“Learning to Love Myself” iiwaa

“Emotions” Joey dib

“Different Colors” WALK THE MOON Clairo

“Boys In The Street” Greg Holden, Seeb

Protest organizers encouraged rally-goers to speak out against discrimination at the “Rally to Protect Our Kids” at the Arizona State Capitol, March 5. Beck Toms

scholars regardless of their nationality, gender identity or sexual orientation.

Kado Stewart, vice president of programs and strategy for one·n·ten, attended the protest.

At the state Capitol, Stewart said safe spaces should not be limited to out-of-school programs and the country should take the initiative to defend queer kids in educational spaces.

“LGBTQ youth are valid,” Stewart said. “Their experiences are important, their identities are important, and I feel that it’s critically important for queer youth to have community.”

Stewart sought resources growing up as a queer individual, and when they found none, they curated programs that aided in the coming-out process for queer youth and young adults.

In 2008, they started a summer camp for queer individuals in Prescott. When they discovered many of the kids who joined their program were also involved in one·n·ten, Stewart joined the nonprofit and helped create its free outdoor program, Camp OUTdoors.

In their 17 years with one·n·ten, Stewart said they realized it

| Spring 2025 | The lumberjack

One·n·ten members advocated for the country to take initiative in increasing safe spaces and defending queer students in educational spaces at the “Rally to Protect Our Kids” at the Arizona State Capitol, March 5. Many attendees wore red in support of Red for Ed, a movement for the improvement of public education. Beck Toms

is vital queer people have access to spaces that recognize their needs, ranging from economic to emotional.

“There’s a lot of understandable fear happening right now for the entire LGBTQ community,” Stewart said. “Our doors are open.”

Those interested in getting involved with one·n·ten locally can text @f18onenten to 81010 for program updates and reminders, including program schedules, events and locations.

New members fill out forms confirming their name, pronouns and if they require resources like housing and food.

Story by Taylor McCormick

Drag queen Angel Lust applies white eyeliner as face paint for a photoshoot. Lust is wearing a culturally inspired Diné heritage. Taylor McCormick

Fresh to Flagstaff’s drag scene is 20-year-old Angel Lust, a queen who boldly presents a hyper-feminized version of themselves. Her persona takes inspiration from car models in magazines she admired as a child. “I was always interested in feminine things,” Angel Lust said. “Since being on the reservation, I didn’t know you could do that until I saw a drag queen, and I was like, ‘I can wear dresses.’ I started dressing up in my room secretly.”

Angel Lust is a genderfluid Diné individual who uses all pronouns. When in drag, her outfits closely resemble the theme of each show she performs at. Her goal is to appear as a cisgender woman, using long hair and revealing clothing to do so.

There are no beauty or makeup stores on the Navajo Nation. When they visited Flagstaff as a child, they would sneak to the store to purchase whatever makeup they could get their hands on.

During high school, they began watching “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” and the first queen they were inspired by was Bianca Del Rio, a Cuban Honduran. In an interview with Refinery29, Del Rio said she was told she was not Hispanic enough to represent her culture after winning the show’s sixth season.

Angel Lust said drag became a way for her to present the femininity she felt since eighth grade. Their outward appearance fluctuates based on how masculine or feminine they feel on a

given day, and they believe two-spirit is part of this identity.

Angel Lust said it can be hard to leave the reservation, a challenge they faced when they started their drag career. With limited Indigenous representation in the media, from drag queens to actors, they said they were unaware of the possibilities for different lifestyle choices.

Angel Lust made her debut in March 2024 at “Fresh Faces of FLAUNT” and was a special guest for the “Giveback Drag Show” at Yucca North during Indigenous Heritage Month. Now, she is a new cast member for Dragstaff and performs the last Friday of each month at Firecreek Coffee.

She also became a member of The Kiki Scene’s Phoenixbased House of Kittenz in December 2024. The Kiki Scene, created in the early 2000s by former Hetrick-Martin Institute (HMI) staff members, provides an alternative to the mainstream ballroom scene for queer youth of color. The HMI serves as a LGBTQ+ youth services center.

During Y2K Night on Feb. 28 at Firecreek Coffee, Angel Lust performed twice. From floorwork to climbing on tables, she confidently interacted with the crowd. They said the most difficult parts of getting ready to perform are the uncomfortable padding and high heels, though they have become more accustomed to the latter.

At Revel’s Drag Race, Angel Lust participated in a three-

part competition with runway, talent and question segments at the Monte Vista Hotel on Feb. 14. She wore a Diné-inspired turquoise and orange dress with a feathered headdress, face paint and red handprints on her neck.

They recall the handprints, made of greasepaint and red lipstick, stained their neck for a week.

The red handprints are a symbol of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People movement, a terrifying reality for many Native American women and girls. She used the competition as an opportunity to highlight the movement. Although she did not win, she said first place would have meant being a representative and voice for Indigenous people.

While they do not usually perform drag with undertones of advocacy, Angel Lust said Jayde Justyce, a Mexican American queen who uses their platform for activism, encourages them to speak up.

“She’s one of my really good friends,” Angel Lust said. “She brings a lot of her views and what’s going on into the shows, and I really respect that about her. I feel like, as drag queens, we are looked at more when you’re at shows.”

Between performances at “Burlesque on Birch” on Feb. 22, a show at Hops on Birch, Jayde Justyce spoke to the crowd about the Trump administration. She said she is pained to see students turn on their classmates by threatening to report them and their parents to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement as a Mexican American. She followed up by encouraging the audience to protest anti-trans legislation.

“Go do the damn thing!” Jayde Justyce said. “If you have the ability to boycott, boycott with us!”

Angel Lust said attendees come to the shows to see drag, so the larger the turn out, the more they will hear about what is going on in the world, especially topics that affect 2SLGBTQ+ individuals.

Angel Lust plans to compete in Phoenix for the title of Miss Junior Phoenix Pride, as it is the first year the contest will be open to all of Arizona. She will also make an additional 10 sponsored appearances at drag shows in the Valley this year.

Drag emerged in the late 19th century, with the first recorded drag ball arising in Harlem, New York. The event allowed participants to express themselves creatively and play with gender identity through exaggerated features and mannerisms contradicting traditional gender expectations. While drag is open to anyone, ballroom in particular, was created for Black and Latino queer individuals as a response to racism in queer spaces.

Crystal Labeija, a Black transgender woman, revived ballroom culture with the creation of the house system in 1968, which aided queer people of color in finding community through chosen families. She acted as a house mother to homeless LGBTQ+ youth.

In 1990, several attendees at the third annual Intertribal Native American, First Nations, Gay and Lesbian American Conference in Winnipeg, Manitoba, introduced the term two-spirit, which refers to a person who embodies both masculine and feminine qualities. Twospirits are often visualized as two spiritlike intertwined entities outside the Western gender binary, though this can vary across tribes. In Diné, “dilbaa” refers to a masculine woman or third gender and “nádleehí” refers to a feminine man or fourth gender.

While not all Native drag queens are two-spirit, the identity has made its mark within Indigenous queer communities.

Before bigotry caused by colonization, two-spirit individuals were well-trusted and respected by tribal members. They helped maintain cultural traditions as educators and medicine people and are well-known as knowledge keepers. The title made them targets, as colonization aimed to destroy closely guarded knowledge in Indigenous traditions and cultures.

Despite efforts to diminish two-spirit identities and fluid gender expression, Indigenous drag has persevered. Several Native drag queens use their platforms to shed light on two-spirit existence and use their outfits and performances to pay homage to their tribes.

er

ane Jacobs is Flagstaff Pride’s first traditional Indigenous president raised with the hózhó philosophy of balance and cultural understanding of the Diné lifestyle. In his experience, he said Diné people are welcoming toward 2SLGBTQ+ individuals. He identifies with the fourth gender, nádleehí, and said he did not have to come out to his family, as they have always known subconsciously and accepted him regardless.

However, Jacobs knows people who were kicked out of their homes for their identities. He said traditional ways of life and Indigenous queer representation on reservations diminished when European colonization brought various sects of Christianity to North America.

“It’s extremely important to be seen and heard,” Jacobs said. “When you come from a community that doesn’t necessarily see that, it’s a struggle to put it out there. Thankfully, I’m able to at least say, ‘Here’s your chance to use our stage.’”

At Flagstaff Pride 2024, Jacobs introduced the first Native American market to the festival. This June, he plans to debut the festival’s first Indigenous headliners: Stella Standingbear and Tia Wood.

Navajo Nation Pride works to reintegrate Diné traditions, teachings and perspectives that existed prior to colonization and Western LGBTQ+ identities. Co-founder Alray Nelson’s mission is to reclaim the right to exist while holding the Navajo Nation government accountable for anti-gay legislation. For example, the Diné Marriage Act was passed in 2005 and prohibits same-sex couples from getting married on the reservation.

There have been several attempts as recently as 2025 to amend the Navajo Nation Code to recognize all marriages on the Navajo Nation, but none have been successful.

The first step to supporting Indigenous queer people is acknowledging the harm done to erase and invalidate their existence. Revival of two-spirit identities is essential to increased representation. Jacobs said he has always known the talent within Indigenous two-spirit individuals, but they have always been pushed to the back.

Jacobs uses his position as Flagstaff Pride’s president to give this demographic a stage, a voice and the opportunity to be seen. He plans to partner with the Lived Black Experience Project to further highlight Black perspectives while incorporating more Indigenous aspects into the event.

Drag queen Anastasia starts her number for Dragstaff’s “Divas, Divas, Divas” night at Firecreek Coffee in downtown Flagstaff, March 28. Taylor McCormick

The personas created by drag queens are nothing short of carefully curated. Dressed in a color-coordinated outfit and listening to 2000s pop music, Anastasia’s persona only comes out once the wig and makeup are fully on, embodying her soft but sassy energy.

Anastasia is a 31-year-old Diné, Hopi and Taos drag queen who uses all pronouns and has been doing drag since 2012. She was introduced to drag after attending Flagstaff Pride the same year they came out, sparking her interest in dressing up glamorously. In her bright pink wig and big tutu, Halloweenera Anastasia would attend People Respecting Individuals and Sexual Minorities (PRISM) drag shows at NAU before her 21st birthday.

Despite not identifying with labels — though they know a spectrum of identities exists — Anastasia said they feel a connection to the two-spirit identity. They view two-spirit the same way the LGBTQ+ community views gender-fluid identities: an individual’s gender presentation changes depending on how they feel that day.

Anastasia said they became secure in their identity after shifting their views of gender, allowing them to feel confident both in and out of drag.

“I just kind of went with it or whatever somebody referred [to] me as,” Anastasia said. “I’m still me at the end of the day.

You’re not going to hold something over me, but I am going to take what you’ve given me and still hold the power at the end of the day.”

On the reservation, Anastasia said she noticed minimal drag representation but encountered transgender Indigenous individuals. When she hit her 20s, Anastasia learned about two-spirit identities and the Indigenous version of the gender spectrum.

Subconsciously, she did not view gender expression and sexuality as black and white but rather as people presenting as they truly are.

Flagstaff drag queens after receiving recognition and awards for her art. In addition to Mann, Anastasia enjoys watching every Dragstaff artist perform because it gives her ideas for song choices she would not have considered otherwise.

They believe as a drag queen, they will always make a political statement just by leaving the house. Anastasia said it was rewarding when they realized being confident in their own identity can inspire others. Anastasia was inspired by celebrities like Britney Spears and Lady Gaga for being outspoken and confidently expressing themselves, regardless of criticism they received.

“If I’m just seeing somebody, I’m going to embrace whoever, and I feel like that’s what Indigenous cultures have all kind of built upon,” Anastasia said. “You just love and accept everybody, that’s called kinship. Kinship is the main thing that keeps everyone together.”

Between the ages of 14 and 16, Anastasia lost both of her parents and hopes they are looking down at her, proud of her accomplishments. She said one piece of advice helped her persevere through hardships and pushed her to always accept herself: be happy, be proud and be you.

Anastasia started drag around the same time as Anya C. Mann, a local Diné drag queen whom she admired. She said Mann is her “RuPaul” and compared the way drag queens look up to him to the respect she has for Mann.

Mann has been viewed as a mother figure for

“Even on a bad day,” Anastasia said, “If you can find one thing that you’re happy about, the bad day, be proud that you got over it, and at the end of the day, you’re just being yourself. That’s all you can be.”

When getting ready for a show, 27-year-old Planet Cree finds herself rushing and stressing out. If something does not fit right, she will rip it out and scrap it from the look entirely.

Planet Cree expresses her creativity by experimenting with drag she described as weird and different, much like her paintings and drawings. She grew up in the depths of the Grand Canyon alongside her tribe, the Havasupai, and said drag is critical to conveying political messages.

“Drag inherently is pretty political, especially recently,” Planet Cree said. “It kind of waxes and wanes with how controversial drag is to people.”

Planet Cree said she wants drag to become more political, considering her experience with national parks as a former junior ranger. She uses her social media platform on TikTok to bring awareness to environmental concerns within the Grand Canyon, in addition to misconceptions about Indigenous people.

“There’s issue going on with my tribe in the Grand Canyon,” Planet Cree said. “Now with the presidency, national parks are not being taken care of anymore. They’re firing a bunch of park rangers and people who take care of nature.”

Planet Cree began doing drag about two years ago with the encouragement of drag queens Revelucien and Glamlad Cometh after moving back to Flagstaff to finish college. She remembers feeling nervous and shaky during her first performances. To remedy this, she views shows as a way to prove herself worthy of recognition as a drag queen.

of Indigenous drag is considerable, she believes there is minimal education on what it means to be a drag queen, especially within a variety of Native ways of life.

She is focused on ensuring she has a good time, inadvertently reflecting that energy back to the audience.

She said her drag persona is a mixture of dumb, goofy and campy looks with scary, dark aesthetics. She includes leather, black and red into her makeup and outfits. Her goal is to be both freaky and funny at the same time.

She has created a few cultural outfits inspired by her identity as a Havasupai artist. Although Arizona’s representation of re lo inc makeu an Planet he

“Everyone just has their own thing, their own religion, their own culture,” Planet Cree said. “I think it can be hard to appreciate other people’s cultures sometimes. But I think it mostly comes from a lack of understanding.”

Planet Cree did not learn about the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People movement until college. She was horrified.

Planet Cree said society is usually shocked by her artform.

She is aware not everyone has met an Indigenous person and may not know they still exist, but she said locals are lucky to live in Flagstaff where Indigenous culture is visible.

“Realize that these people and artists are not your enemies,” Planet Cree said. “They’re just people trying to cope with life, too and make art and make people happy.”

Photography by Jason Maggio, Alexandra Ray and Anthony Treviso

Illustration by Palvan Bugenhagen

Story by Morgan Felker Lewis

When her friends start to experience exhaustion and burn out from rushing from class to commitment, Artemis Jones goes out of her way to remind them to take care of themselves. Acknowledging when it is time to take a step back and place one’s health first is a skill she’s had to perfect from a young age.

Jones, an NAU junior majoring in geology and minoring in disability studies, has multiple hidden disabilities.

According to the Invisible Disabilities Association, invisible

or hidden disabilities like mental illnesses, chronic pain or mobilitiy issues are not always immediately apparent, but they can affect a person’s everyday life through a range of symptoms.

Jones was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) at age 14, but it first manifested at age 13. CRPS is a condition that causes extended inflammation and chronic pain from an injury or medical event, such as surgery, trauma or a stroke, but has no visible symptoms associated with it.

Jones also has central auditory processing disorder (CAPD),

celiac disease, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY).

CAPD affects a person’s ability to process auditory stimuli. Jones said she hears voices at the same volume as an elevator hum, and this noise level difference causes her to have trouble processing words.

She was diagnosed with MODY and celiac disease between ages 3 and 6, ADHD at 17 and CAPD between 18 and 19 years old.

CRPS causes Jones to have flare-ups of pain in her leg, and some days, she needs a mobility aid to help manage them. When she uses her cane, she tells people she was in a car crash to avoid the trouble of explaining CRPS.

“They don’t see it every day,” Jones said. “They don’t have a frame of reference for how you’re doing. The days I bring my cane are the days I get the most questions. It’s kind of like you have to explain yourself. Every single time you bring a mobility aid, you have to justify it.”

According to Harvard Medical School, people with hidden disabilities face the decision of either disclosing their disability or shouldering it alone.

The initial injury that led to CRPS left Jones’ hand temporarily paralyzed, and she had severe muscle spasms. At the beginning of the process, she was misdiagnosed.

At age 13, Jones and her mother went to the Scottsdale Mayo Clinic for a diagnosis. Jones said her mother had to beg to get her admitted, as the clinic did not admit patients under 14.

“I went through this whole battery of tests where they tried to figure out what was going on with me neurologically,” Jones said. “At the very end of it, this dude sits me down and says that I have psychosis and that it’s all in my head.”

When she was 14, she received a diagnosis from a professional at Phoenix Children’s Hospital who had worked with CRPS before.

“I feel also a lot in today’s society is what is pushed, like you have to find that diagnosis, that treatment, that condition,” Jones said. “It kind of leads to false assumptions, which worsens the entire process for anybody with hidden disabilities because now we have to fight that and everything else on top of that.”

Lauren Copeland-Glenn, the business and educational partnerships director for NAU’s Office of Mobility and Social Impact and co-chair of the Commission on Disability Access and Design (CDAD), works at NAU to help make campus accessible both in-person and online.

Copeland-Glenn also has a hidden disability. She has two types of migraines that can last for days, mainly triggered by strong scents.

She said NAU is in the process of updating its websites to make them more accessible for users may not be able to access them based on their disabilities. The process will include adding screen readers to all NAU websites in accordance with Americans with Disabilities Act Title II regulations and will be implemented by April 2026.

“I think that this is really going to help a lot of people that probably we don’t even see on a daily basis,” Copeland-Glenn said. “They may have not even requested accommodations because they’ve just kind of figured out how to work in the world.”

John Schaffer, who teaches courses for the disability studies minor at NAU, is also the academic program coordinator for the Institute of Human Development (IHD) and co-chair of CDAD.

Schaffer produces films about people with disabilities through his production company, Wild Asperagus, based in Flagstaff. He worked with an actor with autism spectrum disorder, formerly known as Asperger’s syndrome, on his first film, “Vectors of Autism: a documentary about Laura Nagle.” Nagle named the company after her diagnosis.

of Mobility and Social Impact and co-chair of the Commission on Disability Access and Design helps make campus accessible both in-person and online. Alexandra Ray

More recently, Wild Asperagus showed its film “Sound Tracks” at the Flagstaff Mountain Film Festival in April. The film followed a group of artists with autism who spoke about their lived experiences through art.

“There is so much misunderstanding around the disability experience, and it’s really important that we highlight them telling their own stories in their own ways and sharing their narratives,” Schaffer said. “That’s really how we get change in society.”

Schaffer is one of the advisers for the Advancing Disability Advocacy Club — or Club ADA — a student-run organization that is a center for support on campus.

Jones is the president of Club ADA and the former chief accessibility officer of ASNAU. In her positions on campus, she advocates for people with disabilities and promotes Club ADA as a disability education resource for people at NAU.

“I’m trying to continue to get this club off the ground, host events and just kind of make it more well known than it currently is,” Jones said. “And as a center for disability advocacy, like if you have questions about disability, you can go to Club ADA and ask these questions and somebody there will have an answer for you.”

CDAD works with departments around campus to equip professional staff with the proper training surrounding disabilities through specialized programs specific to each department’s discipline.

“The goal is that people should be able to access any space and get what they need without having to ask for an accommodation, without having to divulge that really personal information,” Copeland-Glenn said.

Jones worked directly with NAU Disability Resources to get receive for her disabilities. The department’s goals are to remove existing barriers and promote accessibility for all, providing a cost-free, universally designed environment for people with disabilities on campus.

Students seeking accommodations have had both positive and negative experiences with Disability Resources, but Jones said the department needs more support.

“Disability Resources is understaffed and overworked, and so a lot of times, people are turned away and things aren’t done how others would hope,” Jones said. “It does kind of create an issue around Disability Resources and a stigma around disabilities in general … but a lot of my professors and a lot of my teachers have been one-hundred percent understanding when I can’t come in because my condition is flaring up.”

Schaffer works under the IHD, which fosters all-inclusive environments for people with disabilities and prioritizes access, attitude and inclusion, according to its website. The disability studies minor is housed in the IHD.

Since starting to teach at NAU in 2008, Schaffer has seen a change in the public’s attitude toward disability advocacy.

“I’ve particularly seen a lot of awareness surrounding neurodivergent people, understanding what autism is, understanding what ADHD is,” Schaffer said. “I think that our NAU community has been way more understanding, accepting and accommodating for our neurodivergent students.”

Jones said her ADHD diagnosis caused her understanding of herself to shift, validating her emotions about not being able to become motivated. She learned it is normal to quit and fail, and it is important to enforce boundaries in social settings.

She relied on her friends to help her when she was not doing well and eventually learned to stand up for herself in the world as a person with a hidden disability.

“All it taught me was that somebody likely always has something,” Jones said. “There’s always something going on behind the scenes that you aren’t privy to, that you don’t know, and so it’s best to be kind.”

Story by Mason Robles

Photography by Caitlyn Anderson

ory hotography CaitlynAnderson

Illustration by Alex Porras, Hannah Barrett and Palvan Bugenhagen

New realities are hard to realize when you’ve never experienced them — especially when something as thin as paper can do so much. Nature rang more clearly than ever before. Maybe the beauty was a byproduct of the perfect weather, but I could feel the earth breathing across my skin as my spirit revealed a new world.

Flowing in tandem with the wind, I slowly phased into another plane of existence. I separated from my physical form mentally while physically feeling everything around me in intense detail.

I’d heard psychedelics could be ued for therapy, so I wasn’t particularly afraid of the trip ahead. Setting aside an entire day to trip let me enjoy myself and the moment. No other anxieties. I do know every trip is different and depends heavily on circumstances, so had I been in a bad space mentally, I wouldn’t have thought about tripping recreationally.

Free from the chains of sobriety, the marigold petal bridge to the spirit world showed itself to me. Día de los Muertos was over, but for once, the spirit actually burned in me; I’ve never felt so connected to the land I stood on.

I saw, with my own eyes, the world as it relates to me spiritually. My ancestors lived here long before — I could put into perspective why I love the land. Arizona was my ancestors’ land before white colonizers stole it from them, so if anyone deserves to be here, it’s me: No one is illegal on stolen land.

Unlike the spirituality I studied as a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, this connection was real.

As a Mexican American, taking college courses helped me better understand my personal experiences; how colonization and whiteness impacted my perception of the world I grew up in.

made me feel less Mexican or more hit

in my life, my teachers helped me understand how my experience fits into the Mexican diaspora. Parents of assimilated Mestizos didn’t teach us our native tongue or gave us white names to save us from future discrimination. I’ve since learned to take off the Eurocentric lens that American education forces students to look through.

Built on genocide and colonization, our white ancestors committed heinous and violent acts anywhere you can point to on a map, but the packaging of their history always praises them.

My dad is from Mexico City. He brought me and my siblings there as young kids and showed us the deep history of the Aztecs

I learned about Aztecs in history classes, their section in textbooks

The language of colonization describes Eurocentrism as normality and others as savages. Had I not been to Mexico with my family, I wouldn’t have seen the rich history and advanced technology of the Aztecs. In American schools, we only learn about the white man’s whitewashed history and degrade the rest despite its legacy of colonization and slavery.

ua d th va schools, washed his colonization

Human sacrifice is obviously inhumane, but there were never nuances taught about anything regarding Mexican history and culture in our Eurocentric education.

Growing up Mormon, I used to celebrate my deep and direct