The Butterfly Habitat Network

NABA continues to work on laying the groundwork for its Butterfly Habitat Network. In southern Florida we have initiated ambitious plans to save Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreaks (much more detail about this in the next issue). In New Jersey, we are exploring the possibility of purchasing, or managing for its rare butterflies, Klots’ Bog in Lakehurst. In the upper Midwest, we are actively looking for land that would be appropriate to purchase. In southern California, we are working with others to determine what steps can be taken to save Hermes Coppers from extinction. And, in the East, we are working with the USFWS to determine the status and needs of Frosted Elfins.

First offered in connection with the Memorial Day and Victoria Day Counts, NABA is extending it’s offer of a free, trial membership to people who participate in the NABA Butterfly Count Program who have not previously been NABA members. The free, trial membership includes access to digital versions of NABA publications. So, invite your friends, family and neighbors to participate in the Counts, helping to monitor and conserve butterflies throughout North America — they will be rewarded with a free, trial membership.

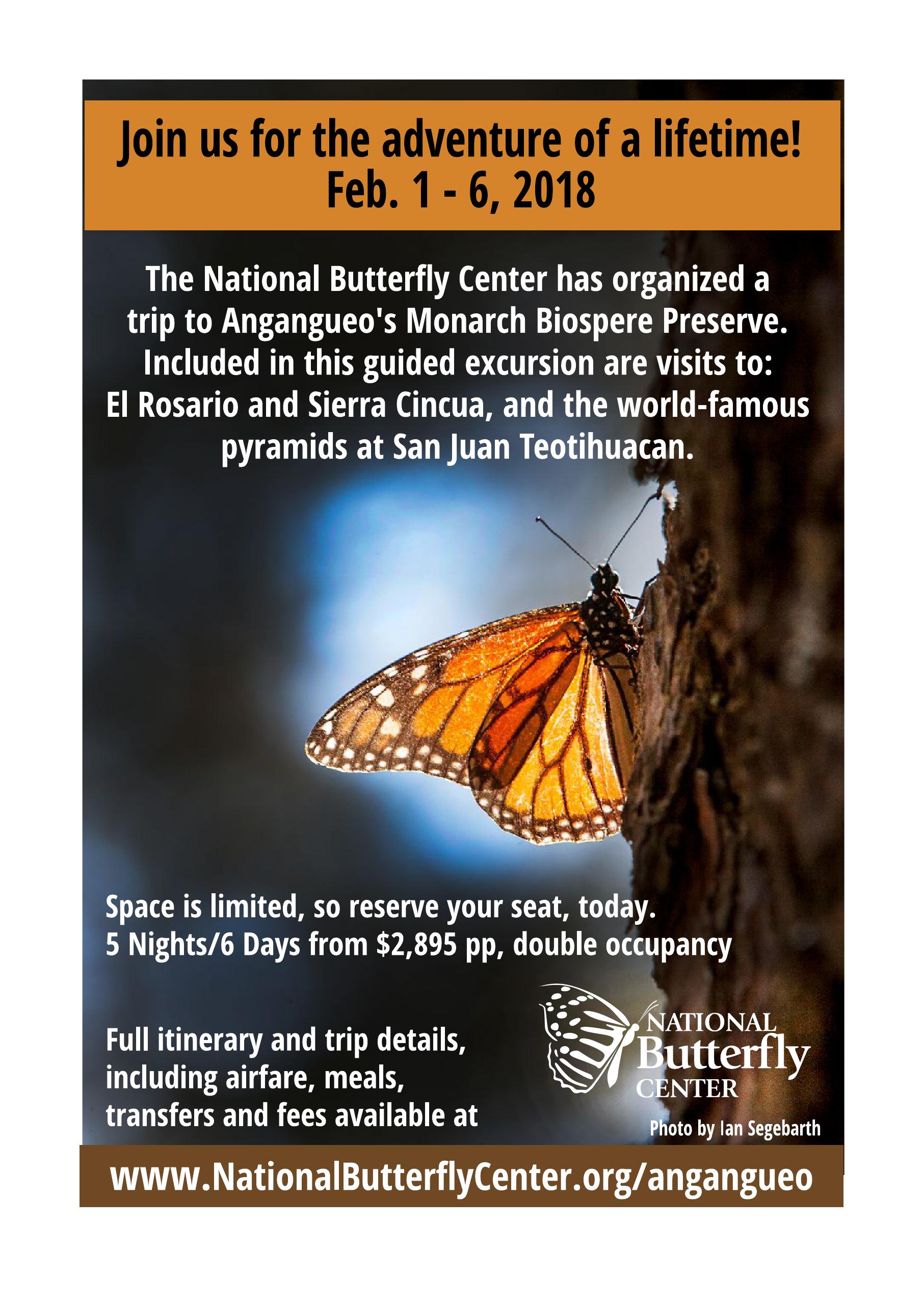

In February, 2018, NABA is offering, for the first time, a trip of a lifetime to see and learn about the spectacular Monarch overwintering sites in the mountains of central Mexico. For more information, see page 35 of this issue.

This year’s Texas Butterfly Festival will be held Nov. 4 - 7. Don’t miss the sensational butterflies, the amazing food, or camaraderie and good times! See the back cover of this issue for more information.

The thirteenth NABA Biennial Members Meeting is tentatively planned to be held in mid September, 2018 in Tallahassee, Florida. Don’t miss this great opportunity to see butterflies you may never have seen before, including Yehl Skipper, Berry’s Skipper and Dotted Skipper, along with thousands of individual butterflies, including many individuals of seven species of swallowtails, and to connect with ardent butterfliers from throughout the country. NABA meetings are always fun!

You can now follow NABA activities on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest

Please smile if you use Amazon to purchase anything! If you do, Amazon will donate a portion of the purchase price, at no cost to you, to NABA. Simply go to smile.amazon.com and follow instructions, choosing North American Butterfly Association as your charity.

Continued on inside back cover

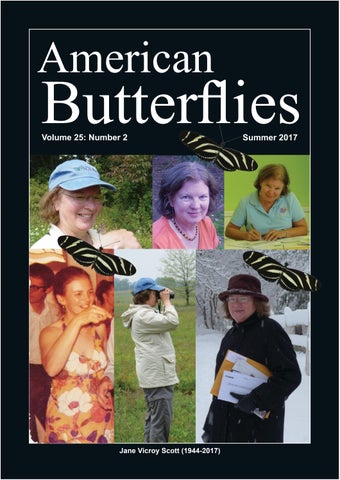

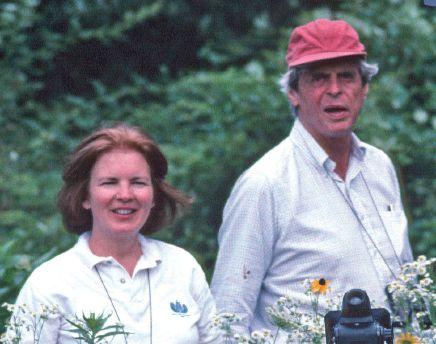

Cover photos of Jane Vicroy Scott (1944-2017):

Top left, Aug. 28, 2004, with a Hackberry Emperor at Peaquest WMA, Warren Co., NJ.

Top middle, July 1, 2006, Convent Station, Morris Co., NJ.

Top right , Nov. 3, 2010, going over finances at the newly constructed Visitors Pavilion, National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

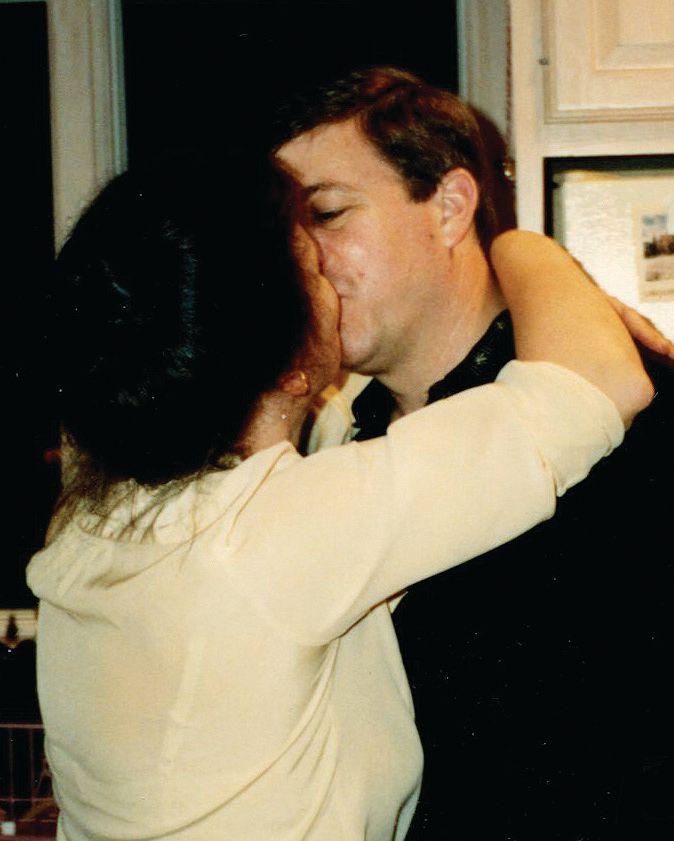

Bottom left, May, 1976, Her Ph.D. party, Houston, Texas.

Bottom middle, May 15, 2008, Galeville Airport, Ulster Co., NY.

Bottom right, Feb. 3, 2014, retrieving NABA mail, Morristown, Morris Co., NJ.

See page 36.

The North American Butterfly Association, Inc. (NABA), a non-profit organization, was formed to promote public enjoyment and conservation of butterflies. Membership in NABA is open to all those who share our purpose.

President:

Jeffrey Glassberg

Vice-president:

James Springer Secrty./Treasurer

Ann James Directors:

Jeffrey Glassberg

Fred Heath

Yvonne Homeyer

Ann James

Dennis Olle

Robert Robbins

James Springer

Patricia Sutton Scientific Advisory Board

Nat Holland

Naomi Pierce

Robert Robbins

Ron Rutowski

John Shuey

Ernest Williams

Volume 25: Number 2

Summer 2017

It’s People — Stupid! by Jeffrey Glassberg 4 Acting Locally to Help Globally Vulnerable Frosted Elfins by Dean Jue

16 You Are What You Eat

17 Eastern Tiger Swallowtail on Tuliptree in OH, by Jan Dixon

20 Common Checkered-Skipper on Cuban Fanpetals in TX, by Don Dubois 24 Eye Color in Satyrs by Jeffrey Glassberg

28 Taxonomists Just Wanna Have Fun! Go Tell It On The Mountain by Harry Zirlin

In Memoriam: Jane Vicroy Scott by Jeffrey Glassberg

American Butterflies (ISSN 1087-450X) is published quarterly by the North American Butterfly Association, Inc. (NABA), 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; tel. 973285-0907; fax 973-285-0936; web site, www.naba.org. Copyright © 2017 by North American Butterfly Association, Inc. All rights reserved. The statements of contributors do not necessarily represent the views or beliefs of NABA and NABA does not warrant or endorse products or services of advertisers.

Editor, Jeffrey Glassberg

Editorial Assistance, Matthew Scott and Sharon Wander

Please send address changes (allow 6-8 weeks for correction) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; or email to naba@naba.org

Many of you may remember the Bill Clinton campaign slogan “It’s the economy — stupid.” The slogan was a way of focusing on what was most important to most people — their own jobs and thus their ability to feed, clothe and house themselves and their family.

More than 90% of people do not have a strong connection to butterflies or to anything related to nature. More often than not, they are actually afraid of nature — it’s a negative to them, not a positive.

Members of the North American Butterfly Association have a strong connection to butterflies and to all of nature. But even NABA members probably respond more strongly to the immediate needs of people than to the needs of butterflies.

This was forcefully thrust upon me when NABA’s Secretary/Treasurer, and my wife of more than 40 years, Jane Vicroy Scott died (see pg 36). Although it is difficult to imagine anyone being more passionate about butterflies than am I, if every single butterfly disappeared from the face of the Earth, the emotional pain I would feel would be nothing compared to what I’ve felt following Jane’s death.

Obviously, that is not to say that Jane’s death was a more important loss to the planet than the complete loss of butterflies, but rather that one’s response to the loss of butterflies is mainly an intellectual response, a realization that this is a terrible thing for the planet while one’s response to the loss of a loved one is profound grief and pain. Jane’s death literally broke my heart and I now need heart surgery.

So, if we want to engage more people with nature, it may be that we need to focus more on the people side of the equation than on nature itself. If we want to save butterflies, we need to find, or create, ways to show nonnature people that becoming involved with butterflies will help them personally and be good for other people as well.

Try getting other people into butterflying by pointing out to them that walking in the sunshine through fields of flowers is a low-impact way to keep healthy. Serious butterfliers are in great shape and have that just-eclosed look (well, this may not be completely true of all of us). So, don’t sign up for the gym (which most people mean to use, but don’t), go butterflying instead.

Show young people how butterflying is like a real life video game or a treasure hunt, where you are trying to identify small, but beautiful, objects that sometimes come hurtling at you at high speeds.

For couples you know who may not be experiencing complete and satisfying connubial bliss, let them know that butterflying is a powerful de-stressing agent. In addition, mastering the art of erotic tick checks is a medically proven way of saving a marriage. So, don’t go to a couples counselor, go butterflying instead.

Of course, helping butterflies means conserving and creating habitat for butterflies and working toward the elimination of pesticides that are toxic to butterflies. As it turns out, the same habitats that are good for butterflies are good for people. Creating the aforementioned de-stressing zones fosters the goals of providing clean air and water for people. And creating pesticides that only kill the real pests, e.g., Anopholine mosquitoes that carry malaria, stops people from being exposed to the toxic pesticides that are currently poisoning people.

You can help both butterflies and people by contributing to the Jane Vicroy Scott Memorial Fund by going to www.naba.org and clicking on “Donate”.

Please photocopy this membership application form and pass it along to friends and acquaintances who might be interested in NABA

Yes! I want to join NABA, the North American Butterfly Association, and receive American Butterflies and The Butterfly Gardener and/or contribute to building the premier butterfly garden in the world, the National Butterfly Center. The Center, located on approximately 100 acres of land fronting the Rio Grande River in Mission, Texas uses native trees, shrubs and wildflowers to create a spectacular natural butterfly garden that importantly benefits butterflies, an endangered ecosystem and the people of the Rio Grande Valley.

Name:

Address:

Email (only used for NABA business):______________________

Tel.:______________________ Special Interests (circle): Listing, Gardening, Observation, Photography, Conservation, Other

Tax-deductible dues enclosed (circle): Regular $35 ($70 outside U.S., Canada or Mexico), Family $45 ($90 outside North Am.). Special sponsorship levels: Copper $55; Skipper $100; Admiral $250; Monarch $1000. Institution/Library subscription to all annual publications $60 ($100 outside U.S., Canada or Mexico). Special tax-deductible contributions to NABA (please circle): $125, $200, $1000, $5000. Mail checks (in U.S. dollars) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960

American Butterflies welcomes the unsolicited submission of articles to: Editor, American Butterflies, NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960. We will reply to your submission only if accepted and we will be unable to return any unsolicited articles, photographs, artwork, or other material, so please do not send materials that you would want returned. Articles may be submitted in any form, but those on disks in Microsoft word are preferred. For the type of articles, including length and style, that we publish, refer to issues of American Butterflies.

If you have questions about missing magazines, membership expiration date, change of address, etc., please write to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960 or email to naba@naba.org.

American Butterflies welcomes advertising. Rates are the same for all advertisers, including NABA members, officers and directors. For more information, please write us at: American Butterflies, 4 Delaware Road, Morristown, NJ 07960, or telephone, 973-285-0907, or fax 973-285-0936 for current rates and closing dates.

Occasionally, members send membership dues twice. Our policy in such cases, unless instructed differently, is to extend membership for an additional year.

NABA sometimes exchanges or sells its membership list to like-minded organizations that supply services or products that might be of interest to members. If you would like your name deleted from membership lists we supply others, please write and so inform:

NABA Membership Services, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960

Sally Jue

Introduction

Many North American Butterfly Association (NABA) members enjoy getting into the field to look for butterflies and especially delight in finding rarer species. Wouldn’t it be great if this passion for finding rare butterflies resulted in actions that help protect them?

This is a story of how citizen scientists are doing just that in Florida. This article describes a statewide project powered by citizen scientists that benefited Florida’s rare butterflies and a local citizen science effort that focuses on Frosted Elfins to help preserve the largest known population of this rare butterfly in the Southeast.

Frosted Elfins are small butterflies in the gossamerwing family that were originally found from Ontario and New England southward to northern Florida and westward to Wisconsin and the Mississippi River. (The populations west of the Mississippi River are often treated as a separate subspecies, Callophrys irus hadros.) The elfin’s overall range is now greatly reduced, and it is extinct or imperiled in 20 of the 32 states or provinces where it originally occurred. Current population strongholds are in New Jersey, Massachusetts and Michigan. Prior to 2008, the only known populations in Florida were in the northeastern counties of Clay and Nassau.

Left: Adult male Frosted Eflins are territorial, often perching on vegetation near their host plant. Mar. 4, 2017.

Below: Sites where Sundial Lupines form a nearly solid groundcover produce the highest number of Frosted Elfins.

Opposite page: Dean Jue searching for Frosted Elfins at one of the survey sites. Apr. 6, 2016.

The butterfly is ranked by NatureServe as a G3 globally-vulnerable species (NatureServe, 2017).

Frosted Elfins have a single brood each year, with adults emerging from their chrysalises in early spring. In Florida, the adult flight is from late February through midApril with eggs laid during this period. Eggs hatch after about a week, and caterpillars are active for three to four weeks. They pupate at or just below the soil surface where they remain until the following spring.

The elfin’s natural habitat includes grasslands, barrens, savannas, and both hardwood and conifer woodlands, often on sandy soils. In Florida, the species’ sole host plant is Sundial Lupine, but in some other states it uses various wild indigos instead. The habitats where the butterflies and their host plants occur are maintained by disturbance, such as fire. Without periodic disturbances, the host plants becomes overgrown by shrubs and other vegetation and the site eventually becomes unsuitable for the butterfly.

The largest known population of Frosted Elfins is in New Jersey and is believed to number in the thousands. Another New Jersey population has probably close to 500 individuals. These populations occur on human-derived habitats such as powerline and railroad right-of-ways, old gravel pits, or approach zones of airports rather than in habitats maintained by more natural processes such as fire. In the Carolinas, fewer than 20 adults are usually seen on a single survey, compared with 50 to 100 or more adults at the top New Jersey sites. In 2008, the known populations of the species in Florida were in pine uplands (i.e., sandhill) and right-of-ways and had a high of about 20 adults seen in a single day. The population total for an area is believed to be a few times the numbers seen on a given day (NatureServe, 2017).

In 2007, with funding from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the

Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI — the state’s natural heritage program) began a six-year project to confirm the continued presence of rare and declining butterfly species on previously-documented sites and to search for new populations on Florida conservation lands. Data collected by volunteer regional coordinators and other citizen scientists, many of them NABA members, were submitted to FNAI and incorporated into FNAI’s statewide biological database which is used by decision makers to help protect and maintain Florida’s biodiversity. Their efforts resulted in the addition of 600 new records for rare butterflies.

Because butterflies have specific host plant requirements, one way to look for undiscovered populations is to search where the butterfly’s host plant grows. For the Frosted Elfin, FNAI staff asked local native plant society members and land managers

Opposite page: Adult Frosted Elfins frequently nectar on Sundial Lupine buds and flowers. This individual, with unusually colored hindwings, was sighted over a period of several days near the same spot. Mar. 24, 2016.

Left: In early spring, Sundial Lupine is one of the most conspicuous flowering plants in sandhills and is a popular nectar source for many insects such as this carpenter bee. Apr. 5, 2015.

Franklin County.

for locations of Sundial Lupine in the central Florida Panhandle. Local native plant enthusiast and NABA member Virginia Craig spends several days a month botanizing in the Apalachicola National Forest (ANF) and knew of several patches of this lupine in Liberty County. Louise Kirn, the ANF ecologist in 2007, knew of another lupine location in

In the spring of 2008, Virginia led a group of local NABA members to the Liberty County site. While examining lupine growing along the edge of a dirt road, Sally Jue was surprised to see an adult elfin fluttering at her feet. This was the first documentation of Frosted Elfin in the central Florida Panhandle! On our trip to the Franklin County site we found several more adult elfins. Using this same approach, MaryAnn Friedman, the western Florida Panhandle regional coordinator for the FNAI project, discovered new populations of elfins in Okaloosa and Walton counties. By 2010, we had extended the range to Leon County. In all, citizen scientists documented Frosted Elfins in five new Florida counties!

In April 2010, Virginia discovered the first

Above: Without periodic fire, sandhills are quickly invaded by hardwoods such as oaks, which shade out the Sundial Lupines needed as food for Frosted Elfin caterpillars. Apr. 10, 2015.

Below: A survey site a few days after a prescribed burn. White rings mark longleaf pine cavity trees used by Red-cockaded Woodpeckers, another threatened species that inhabits Florida sandhills. Mar. 6, 2017.

Frosted Elfin population in Leon County at a site in the ANF where she knew from earlier explorations Sundial Lupine grew. Later that month, a group of NABA members visited the site and counted 20 elfin caterpillars on the lupine leaves and buds. In November 2010, the US Forest Service (USFS) conducted a prescribed burn on this unit of the forest.

After the burn and through the spring of 2013, we found no evidence of Frosted Elfins at the site despite repeated searches. The Sundial Lupine, however, responded well to the burn and was as prevalent as before.

So where was the nearest geographic area occupied by Frosted Elfin relative to the ANF site where the elfin had disappeared? A clue came in March 2014 when, while hiking in the ANF, Sally observed an elfin flying from the west towards the known lupine site. A search of the forest about half a mile to the

west produced 25 adult Frosted Elfins in an area with large patches of Sundial Lupine. Although extirpated from the first known location, the butterfly was still present in Leon County!

Species such as Frosted Elfin, that require periodic disturbances to persist, are often found in a metapopulation. A metapopulation is a group of populations of the same species that are geographically separated from each other but whose individual members move from one population to another. When one site becomes unsuitable for the species’ survival (e.g., due to a prescribed fire or the longterm exclusion of fire), individuals move to other nearby areas of suitable habitat. When the unsuitable areas become suitable again, individuals from nearby sites move back into these unoccupied areas. This maintains the overall metapopulation across both space and

Above: Mating Frosted Elfins. Feb. 28, 2017.

Right: Freshly-laid Frosted Elfin eggs, such as this one on a Sundial Lupine flower bud, are flattened, pale green disks. Mar. 27, 2017.

Opposite page top left: Late instar Frosted Elfin caterpillar feeding on Sundial Lupine flower. Apr. 5, 2015.

Opposite page top right: Third instar caterpillar, about 1/3 inch long, feeding on Sundial Lupine leaflet. Apr. 13, 2017.

Opposite page bottom: Frosted Elfin pupa, about 1/2 long. Fourth instar caterpillars wander up to several feet from their host plants and pupate at or up to an inch or so below the soil surface. June 6, 2017. egg

Discovery and documentation of the first Frosted Elfin found in the central Florida Panhandle in March 2008. From left to right, Virginia Craig and Amy Sang in front, Dean Jue and David Harder in back. Mar. 23, 2008.

time, even if the species may periodically disappear from a particular portion of the area at a given moment in time. Metapopulation structure and dynamics is currently an active area of biological research.

The “rediscovery” of Frosted Elfins in Leon County pointed to a larger issue. What if the newly-discovered location was the only other site for Frosted Elfins in the county and it had been also burned at the same time? Would that have exterminated all the Frosted Elfins in Leon County? We needed to know if there were other lupine patches nearby, and if they had elfins that would help comprise a larger metapopulation.

In the spring of 2014, using FNAI maps of sandhills, NABA member Dave McElveen led a team of Jean McElveen and Brian Lloyd that eagerly hiked, biked, and drove to search 30 square miles in the ANF for lupine patches. They were surprised to find 30 new sites! Proximity of these lupine patches to one another suggested they might all be part of one large elfin metapopulation. But how many of them actually had elfins?

We formed a team of local NABA members Wilson Baker, Virginia Craig, Dean Jue, Sally Jue, Brian Lloyd, and Dave McElveen. For our first survey season in spring 2015, we focused on collecting presence/absence data for Frosted Elfin adults and caterpillars at all 34 known lupine sites. During the adult flight period, we observed

elfins at 26 sites. We were thrilled! Elfins were much more widespread than we had dreamed. We also found three new lupine sites, bringing the total number of sites monitored to 37.

As the adult flight wound down, we shifted our focus to searching for caterpillars at sites where we had not seen adults, including at the newly-discovered sites. This paid off as we found caterpillars at one site where no adults had been observed.

Overall, we documented presence (either adults or caterpillars) of Frosted Elfins at 27 of 37 lupine sites. The number of adults seen ranged from a single individual at several sites to a high of 90 at a large site covering over 3 hectares. To estimate the minimum population size of the elfin metapopulation, we surveyed as many sites as possible on a day believed to be close to the peak adult flight time (March 20). We counted 140 adult elfins that day. During 2015 caterpillar searches, we found a total of 122 elfin caterpillars.

An unexpected concern we encountered this first year was that the lupine site where the highest number of adult Frosted Elfins had been seen was scheduled to be prescribe burned during April. If burned at that time, many butterfly caterpillars would still be on the lupine plants and would be killed by the fire. Sally contacted a lead ANF biologist and informed him of the significance of the Frosted Elfin population in that particular burn unit. Much to their credit and our relief, the USFS burn staff agreed to delay the prescribed burn for that unit until after mid-May, when most elfin caterpillars would have pupated and thus be more protected from fire.

Recognizing the importance of the distribution of the elfin sites relative to burn units, we refined our objectives and methodologies for 2016. We divided the sites into primary, secondary, and tertiary categories. The primary sites were spread across eight burn units that represented the full range of prescribe burn seasonality (i.e., summer, fall,

and winter) and burn return interval (two, three, and four years since the last burn). We concentrated on these 20 primary sites and conducted at least two surveys per week during the adult flight season, whereas the 17 secondary and tertiary sites were surveyed for adults less frequently. All primary sites were included in our one-day survey to estimate minimum size of the elfin metapopulation. The secondary sites were newly discovered lupine patches or ones that historically had Frosted Elfins but where none were found in 2015. The tertiary sites were small or duplicate sites whose burn seasonality and burn return intervals were already represented by the 20 primary sites. All 37 sites were thoroughly searched for caterpillars in April.

In 2016, the first adult elfins were seen March 1 and the last one on April 20. The maximum number of adults observed on one day was 103, compared to 140 in 2015. This reduction in number of adults was expected since the site with the highest number of adults in 2015 had been burned in that year in July; there was a two-thirds reduction in the number of adults seen at this site after the fire. As in 2015, the butterfly was present at many small lupine sites (i.e., sites of less than 50 square meters) while some much larger, hectare-sized sites had very low numbers of adult elfins.

After the adult survey period, we found an additional 13 new lupine patches and eight of them had Frosted Elfin caterpillars! The 101 elfin caterpillars found across all the sites was comparable to the number seen in 2015. Overall, we documented presence (either adults or caterpillars) of Frosted Elfins at 32 of 50 lupine sites in the ANF.

To further refine our methodologies for the third year, we shifted our focus to burn units. By now we had 50 lupine sites spread across 15 different ANF burn units. The 40 primary lupine sites selected for 2017 surveys were in nine burn units that represented the full range of burn seasonality and burn return intervals described earlier. Unlike the protocol used

in earlier years, all the sites within each burn unit were surveyed on the same day by a team of at least two people. This provided a more standardized count of the number of adult elfins within each burn unit for each survey. Each of the nine burn units was surveyed at least once a week during the adult flight period.

The first adults were seen February 16 and the last one on April 14. As in previous years, a one-day survey of all primary sites was conducted in March to estimate minimum size of the adult elfin population. The number of adults observed that day was 106. Caterpillar surveys became the focus in April and May. We observed about 140 Frosted Elfin caterpillars in 2017 compared to approximately 100 caterpillars during each of the first two years. After analyzing his Frosted Elfin caterpillar pictures from 2015 through 2017, Dave believes he has documented that Florida’s lupine-feeding Frosted Elfins caterpillars have four instar stages like the Wild Indigo-feeding elfins found in other states.

For the first time, we did a pilot capturemark-release study by marking 12 adult elfins to observe their behavior, estimate their life span, and perhaps gain insights on dispersal. After initially marking five elfins, we observed two of them up to seven days later, all close to their original locations. A prescribed burn on one of our nine burn units on March 3 provided a unique opportunity to observe adult elfin response to fire. We marked a total of seven Frosted Elfins in this unit pre- and postburn. One or more of those adults remained at the site for up to four days after the fire. We were very surprised to see them, since the site was quite black and virtually all of the lupine had been burned.

We plan to continue surveying for elfins in the ANF in future years. As we analyze our first three years of data, we look to focus on unresolved issues such as adult dispersal patterns.

Our project sprang from our desire to learn enough about Frosted Elfins to provide land managers with information that would ensure long-term viability of the species in the ANF. We have kept in close contact with USFS staff throughout the project, briefing them regularly on our plans and findings at each step. They are aware of the significance of the Frosted Elfins on their lands, have been receptive to our input, and have occasionally altered their prescribed burn plans to better accommodate the biological needs of elfins. Based on data collection, we have provided three years of results to the USFS that can help inform land management objectives for the ANF.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) began assessing

if Frosted Elfins warrant federal protection under the Endangered Species Act and will be drafting a conservation strategy for this species. The information we have collected is being incorporated into the assessment. Because we study the largest known population of Frosted Elfins in the Southeast, our data will be an important component of any nationwide conservation strategy for the species. It is notable that the ANF elfin population is maintaining itself in a natural metapopulation structure within a large national forest, as opposed to in more artificial situations such as the large New Jersey elfin populations. The ANF metapopulation can be studied by biologists to help develop conservation strategies for recovering Frosted Elfin populations in other parts of the country where the butterfly is now rare or extirpated. We recently shared our survey results with biologists at a local university. They are trained in sophisticated statistical analysis techniques that can be applied to our data

to identify trends or other findings that may warrant additional study. Through their coursework and contacts, they know students who may be interested in helping with our next year’s field work as volunteers or as a starting point for developing their own personal research. A longer-term commitment to studying the biology and conservation needs of our local Frosted Elfin population by university biologists and their students is now a real possibility.

And, of course, there are many more questions to answer. Do both male and female elfins disperse from the site where they eclose? What percentage of elfin pupas survive a prescribed burn? Why do elfins regularly use some small lupine patches while rarely using some large lupine patches, even though we see little difference among those sites? Investigating such questions requires a much larger time commitment than our team has.

We found our passion for rare butterflies can help their long-term conservation. You can do this, too! At a minimum, share your observations on websites such as “Butterflies I’ve Seen”. This develops a database to be used in conservation efforts that preserve rare and declining butterfly species. If the butterfly species has regional or national conservation importance, contact the North American Butterfly Association, as NABA might be in a position to help. If you want to go further, here are some suggestions.

First, learn as much as you can about your butterfly of interest. Go beyond your field guide to the NatureServe website (www. natureserve.org) to find out how imperiled a butterfly species is on both a statewide and global basis. Use web-based research engines (like Google, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate) to find scientists who are currently working on your species of interest and read their publications.

Next, identify exactly what you want to accomplish, how you are going to do it, and the resources you need. Surveying for and

counting the butterflies will undoubtedly be part of the plan, but also decide how often (e.g., daily, weekly) and who will do it. What is the specific route or area that will be surveyed? Start small and simple and expand in subsequent survey seasons. It is possible to work with multi-brooded species, but choosing butterflies that have only one or two broods per year limits your field season to fewer months and provides time for analyzing data and refining project methodologies.

Because unexpected circumstances will arise, your project should have several participants so that each can help cover for the other when the need arises. Also, unless the study is taking place solely on your property, the land manager or owner should be informed of your plans. This communication will identify potential conflicts (e.g., your study site is slated for conversion to a different land use) and begin the process of working with the land managers so the needs of butterflies will be considered in future management decisions. Remember that land managers often have conflicting legal mandates and responsibilities that may make it difficult for them to manage the land solely for the benefit of one species. Be flexible enough with your project to take advantage of unexpected opportunities. A prescribed burn during our Frosted Elfin surveys allowed us to look at its impacts on the adult butterflies. As your study collects data over more than one field season, consider involving scientists and students from your local educational institutions, both for potential personnel resources and for expertise beyond what your team can provide.

And lastly, HAVE FUN! We live in a time when butterflies are contributing to current research efforts (e.g., climate change) and becoming recognized as species that need to be considered when land management decisions are made (e.g., Monarch, Mardon Skipper, Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreak).

Through your participation in citizen science efforts at whatever level you can provide, you can help make this a better world both for butterflies and ourselves.

The You Are What You Eat project documents the caterpillar foodplants of North American butterflies. For those who would like to participate in this photodocumentation, here are instructions:

Find an egg or a caterpillar (or a group of eggs or caterpillars) on a single plant in the “wild” (this includes gardens). The plant does not need to be native to the area — we want to document all plants used by North American butterflies.

Follow this particular egg or caterpillar (or group of eggs or caterpillars) through to adulthood, with the following documentation.

1. Photograph the actual individual plant on which the egg or caterpillar was found, showing any key features needed for the identification of the plant.

2. Photograph the egg or caterpillar.

3. Either leave the egg or caterpillar on the original plant, perhaps sleeving the plant

it is on with netting, allowing the caterpillar to develop in the wild, or remove the egg or caterpillar to your home and feed it only the same species of plant on which it was found.

4. Photograph later instars of the caterpillar.

5. Photograph the resulting chrysalis.

6. Photograph the adult after it emerges from the chrysalis.

7. If the egg or caterpillar was relocated for raising, release the adult back into the wild at the spot where you found it.

We would like to document each plant species used by each North American butterfly species, for each state or province.

In addition to appearing in American Butterflies, the results of this project will be posted to the NABA website. Please send any butterfly species/plant species/state or province trio that is not already posted to naba@naba. org.

Opposite page

Left: Almost a year after this Tuliptree supported the Eastern Tiger Swallowtail shown in this article, the tree, doing poorly, was cut back and replanted. Here, it puts forth a hopeful sprout, looking for new Eastern Tiger Swallowtails. May 6, 2016.

Top right: This Eastern Tiger Swallowtail egg was laid on the Tuliptree the first day it was planted! Aug. 7, 2015.

by Jan Dixon

On August 7, 2015 I planted both a Tuliptree and a Black Cherry, adding to the butterfly habitat I am creating around my house. Late that same afternoon I noticed an Eastern Tiger Swallowtail laying eggs on the Tuliptree leaves. I brought the egg into my garage, where I raise butterflies, and put the leaf in a jar in an aquarium.

The egg hatched and I took photos of the developing caterpillar on August 23 at 8 days, on August 29 at 14 days, and on Sept. 4 at 20 days.

On Sept. 7 the caterpillar crawled up the side of the aquarium to pupate.

The chrysalis was kept in the garage, lighted by windows, over the winter months. I sprayed the chrysalis with water approximately every 7-10 days so it would not get dehydrated.

The Eastern Tiger Swallowtail emerged on April 29. I was very surprised to see it so early and unfortunately it was not a warm day. However, concerned it would not survive in the aquarium; I found a shrub with blooms

along the front of my house and placed the butterfly on one of the blooms protected by an overhang. I worried and watched as it rained and got colder, especially at night when the temperature dropped down to the 40’s. The butterfly remained where I placed it for three cold/rainy days and finally on Tuesday, May 3rd the weather warmed up to a 65 degree high. The last I saw the butterfly it had the wings opened and positioned to get the best of what sun there was that day.

I am not sure why the butterfly emerged so early. None of the other butterflies I overwintered had emerged as of May 4, 2016 including another Eastern Tiger

Swallowtail, and two Spicebush and eight Black Swallowtails. However, the second Eastern Tiger Swallowtail emerged sometime after 3:00 p.m. in the late afternoon of May 5. I hope I may yet see the first Eastern Tiger Swallowtail flying in my yard and that maybe the second one is a female and the first a male.

Above

The adult, a male, emerged the following spring and was placed outside. May 1, 2016.

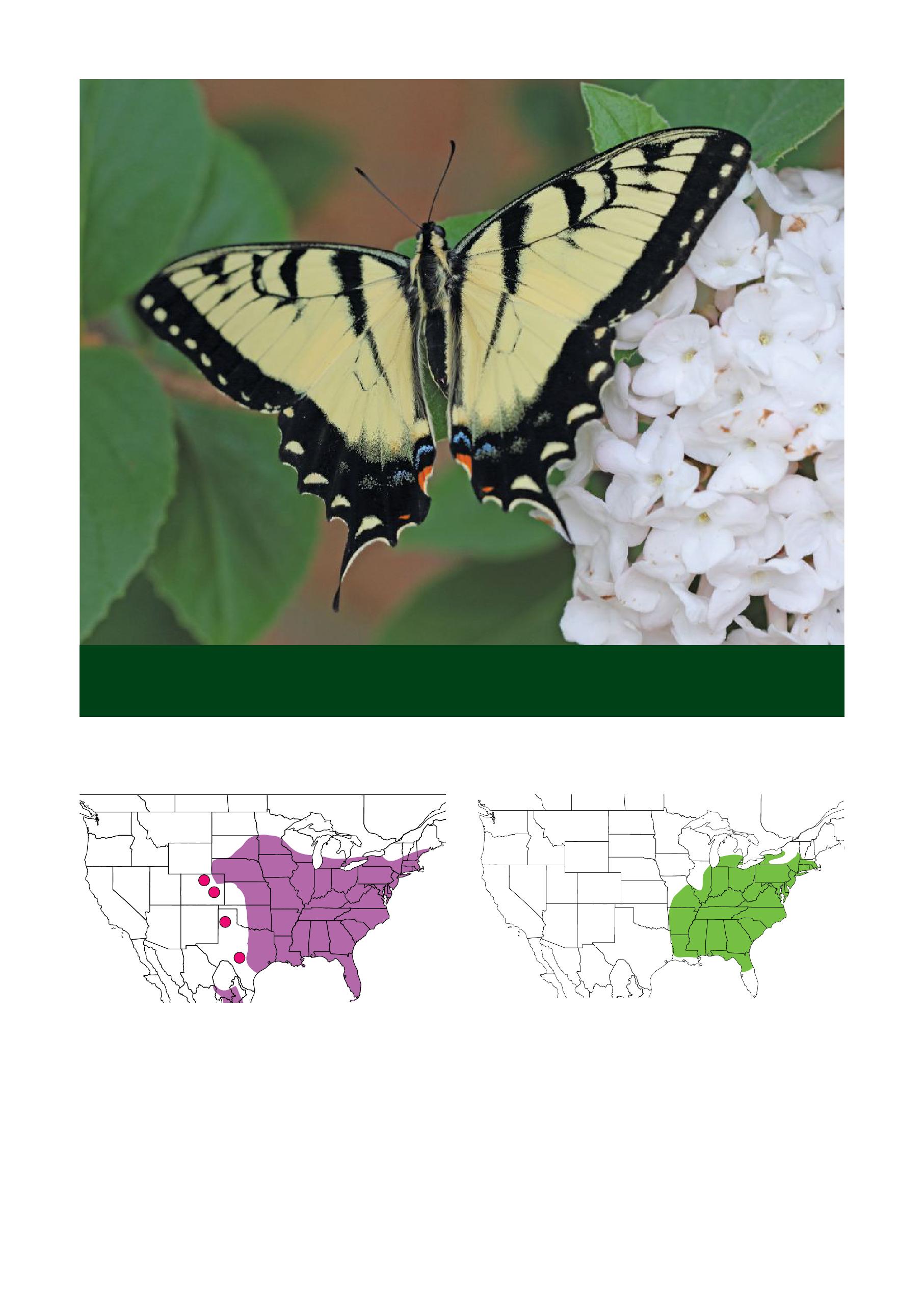

Above: A drawing of the range where Eastern Tiger Swallowtails are found. Purple indicates two broods. Cherry spots are locations where strays have occurred. (drawing from the second edition of A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Tuliptree, based upon county occurrence data from the Biota of North America Program. This might be a useful plant for your garden if you live within the range shown.

by Don Dubois

A common, tough-stemmed perennial weed in the Houston, Texas area, Cuban Fanpetals is a primary host plant for Common CheckeredSkippers. It will quickly move into any disturbed site and is an uninvited guest in many gardens. Its flower is not showy but its use as a butterfly host plant gives gardeners a reason to let it grow. According to some sources the tough stems were once used to make cords and brooms. It is also reported to contain alkaloids and have medicinal uses. It is avoided by cattle in pastures

A Common Checkered-Skipper was seen laying eggs on Cuban Fanpetals on June 7. The eggs were being laid in the flower buds but they were small enough and so well hidden that a search did not reveal them. While no eggs were found, one of the

stems where egg-laying activity was seen was netted. With a more thorough inspection, a leaf-fold secured with silk threads was discovered on an adjacent plant. Unfolding the leaf nest revealed a small caterpillar.

Opposite page

Top inset: A Common Checkered-Skipper prepares to lay an egg on a Cuban Fanpetal. June 7, 2013.

Top main photo: The Cuban Fanpetal that an egg was laid on. June 8, 2013.

Bottom: An early stage caterpillar. June 17, 2013.

This page

Top left: A Common Checkered-Skipper caterpillar on Cuban Fanpetal. June 7, 2013.

Top right: Late stage caterpillar. June 14, 2013.

Bottom right: Pupa. June 17, 2013.

adult Common Checkered-Skipper emerged on June 23, 2013.

The caterpillar was brought inside and fed stems from the same plant. The caterpillar formed a chrysalis inside a leaf-fold on June 17. Likewise on June 17, a check of the stem netted on June 7 revealed an early instar caterpillar inside a leaf-fold. A photo of the

early instar caterpillar is included as part of the documentation. The chrysalis formed on June 17, hatched on June 26 and the adult butterfly was photographed and released.

Above: A drawing of the range of Common/ White Checkered-Skipper. Purple indicates two broods. Orange indicates three brood. (map from the second edition of A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

American Butterflies, Summer 2017

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Cuban Fanpetal, based upon county occurrence data from the Biota of North America Program. This might be a useful plant for your garden if you live within the range shown.

to both field identification and to taxonomic decisions. For example, in Butterflies through Binoculars: The West (2001), eye color, for the first time, was used to identify butterflies, as I demonstrated how Atlantis and Aphrodite Fritillaries could be separated in the field by their blue-gray and amber respective eye colors. And, in 2013, I described a new species of hairstreak that had been confused with a common species for 100 years but whose eyes are a different color (Robbins, R. and Glassberg, J. A butterfly with olive green eyes discovered in the United States and the Neotropics. Zookeys. 2013; (305): 1–20.).

Recent studies suggest that the butterfly subfamily Satyrinae includes owl-butterflies

by Jeffrey Glassberg

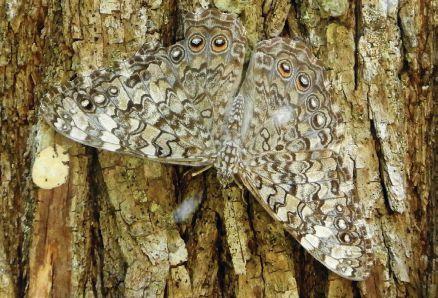

and morphos as well as satyrs. Although not included in these studies, it turns out that the default eye color/pattern for both satyrs and owl-butterflies is gray with vertical black lines. The other butterflies that share this unusual color/pattern are the ticlears (often called clearwings) — the subfamily Ithomiinae — and many of the monarchs — subfamily Danaeinae. Some treat ticlears and monarchs as one group.

For this article, I looked at ten species of owl-butterflies placed in four different genera. All have gray or brown eyes with vertical black stripes (see inset photo, page 26, for an example). I also looked at five species placed in the genus Morpho, all of these have eyes that are solid black/metallic. So far as I am aware, only two other, unrelated, groups of butterflies have metallic eyes — preponas and hairstreaks in the Greatstreak section

Top left: Carolina Satyrs have gray eyes with vertical black stripes, as do most satyrs. Aug. 8, 2014. Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico.

Top right: Little Wood Satyrs are in the minority of satyrs with black eyes. May 22, 2015. Mountainside Park, Morris Co., NJ.

Bottom left: Canyonland Satyrs have black-striped gray eyes, as do all of the gemmed-satyrs. Sept. 2, 2013, Turkey Creek Rd., Cochise Co., AZ.

Bottom right: Red Satyrs, placed in the same genus as Little Wood-Satyrs, also have black eyes. July 29, 2016. Garden Canyon, Cochise Co., AZ.

Opposite page: Agatha’s Blue-Satyr (Chloreuptychia agatha) has eyes typical of most satyrs. Oct. 20, 2015. Napo Province, Ecuador.

Owl-butterflies, such as this white-crescent owl-butterfly (Caligo idomeneus) have eyes that are very similar to satyr eyes. Oct. 30, 2013. Napo Province, Ecuador.

of hairstreaks (which includes Great Purple Hairstreak).

Of the 47 species of satyrs that occur in the United States and Canada, distributed among 14 genera, only Little Wood-Satyr and Red Satyr, (both placed in the genus Megisto) have black eyes (see page 25). Because there are individual butterflies whose wing pattern causes some butterfliers to be unsure of whether they are Carolina Satyrs or are Little Wood-Satyrs, the very different eye color of these two species is a useful field mark.

As best I can tell, outside of the phantomsatyrs (tribe Haeterini), the only genera of New World satyrs where at least some species have black eyes are Cissia, Euptychoides, Euptychia and Megisto. These four genera appear to be closely related, as does the Old World genus Paleonympha whose single species, opalina, also has black eyes. Because all of the members of the genus Euptychia

that I have examined have black eyes, and as an aid to identification, I have given the group name “blackeyed-satyr” to the genus Euptychia. If it turns out that the four abovementioned satyr genera form a monophyletic group, then the name blackeyed-satyr should probably be expanded to include all of them.

The brushfoot family is the only New World family of butterflies where species have gray (or sometimes brown) eyes with vertical black stripes. Within the brushfoot family, both the Monarch subfamily (which includes both monarchs (tribe Danaeini) and ticlears (tribe Ithomiini) and the Satyr subfamily (which includes satyrs, owl-butterflies and morphos) have most species with gray eyes with vertical black stripes.

So, the next time you are looking closely at a butterfly, make sure that you look at it’s eye-color — it could open your eyes to a whole new world!

including

Bottom: Phantom-Satyrs, including Blushing Phantom-Satyr (Cithaerias cliftoni) also have black eyes. Oct. 23, 2014. Napo Province, Ecuador.

by Harry Zirlin

Mountains are embedded in the religions of many people and seem as natural as abodes for deities as the heavens. The Greek myths are in line with other world religions in this regard and we should remember that Greek myths are really the stories of the ancient Greek religion. That is, the ancient Greeks themselves didn’t view these stories as myths any more than a Catholic priest today understands the gospel narratives

as myths. Greece is a mountainous country and Mount Olympus ruled as the premier real estate option for the pantheon of immortals. But Mount Parnassus, which towers over Delphi (home of the Delphic Oracle) was also important in Greek religion. One myth tells us that Apollo, the sun god, was looking for a place to house his oracle. Arriving in Delphi, he was confronted with an enormous snake named “Python” which he killed and decided his oracle should be in Delphi to commemorate his triumph (more anti-snake propaganda along with the serpent in Eden). Once Apollo became associated with Delphi, it was natural that Mount Parnassus would be viewed as important to Apollo as well. But

Above: A Phoebus Parnassian basking in the glow of a ray of sun. June 29, 2013. Scott Mountain, Siskiyou Co., CA.

Opposite page: A Phoebus Parnassian sipping what must be the nectar of the gods. June 29, 2013. Scott Mountain, Siskiyou Co., CA.

according to other sources, Mount Parnassus is where Apollo conceived the nine muses with the titaness Mnemosyne (“Memory”). These versions of the myth have the nine muses living on Mount Parnassus, whereas other versions place the muses on Mount Helicon (see “Where is My Muse” etc.).

When Linnaeus gave names to the butterflies he was describing, he named one after Apollo. We know this species today as Parnassius apollo but Linnaeus placed it in the genus Papilio, as he did with all butterflies. This beautiful species (see pg ??) flies (or used to fly) in grasslands at both high and low elevations throughout Europe. Because it is declining, as are so many species, it is protected by law in most places where it still occurs.

Linnaeus may have felt the name Apollo was appropriate for this regal, sunloving species that often occurs in mountain meadows. But it was Pierre Andre Latreille (1762-1833) who is credited for bestowing the generic name Parnassius on apollo and its congeners in 1804. Latreille was a French zoologist who specialized in insects and other invertebrates. He had trained as a Catholic priest prior to the French Revolution. The new government was anti-Catholic (anti-all religions except the theocracy of the state) and demanded that all priests swear allegiance to the state. Latreille refused and for this was imprisoned in 1793 and facing possible execution. Then along came the beetle that saved his life.

A Clodius Parnassian. June 30, 2015. Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, Jackson Co., OR.

Latreille had already developed his interest in insects prior to imprisonment. A doctor was inspecting the prisoners when he found Latreille inspecting a beetle on the prison floor. Latreille explained to the doctor that it was the rare species Necrobia ruficollis (the Red-shouldered Ham Beetle in the Checkered Beetle family and never mind that ruficollis means “red-necked,” it would be insensitive to call a beetle a redneck). The doctor was so impressed by Latreille’s expertise and dedication to entomology under such adverse conditions that he was able to pull a few political strings and get Latreille and one of his cell-mates released. The story goes that all of the other prisoners were dead within a month. As another aside, that species of beetle also occurs in the USA, but unlike many alien species, it appears to be rare here as well. I’ve never seen it, which may be a good thing.

Latreille almost certainly created the genus Parnassius for “Apollo Butterfly” (as it is called, although Apollo Parnassian strike me as a better name) because of the mountain’s importance to the Apollo myth. Parnassians are actually primitive swallowtails and it is believed that their point of origin was central Asia, where many species occur to day. From there, some moved west to Europe and others moved east over the Bering land bridge (or one of the Bering land bridges as there has been more than one) and into North America. The NABA Checklist Second Edition credits North America with three full species in the genus Parnassius: Parnassius eversmanni, Parnassius phoebus and Parnassius clodius. Of these, there is no debate that I’m aware of that the first two also occur in Eurasia and that clodius is endemic to North America. Our checklist names two subspecies under phoebus: (1) smintheus and (2) behrii, that some recent works treat as full

A Clodius Parnassian (and a copper friend). June 26, 2014. McCloud, Shasta Co., CA.

species, but NABA’s current view is that the evidence to support treatment of these two named populations as full species is weak.

In this regard, here might be a good place to say that in both Eurasia and here, the populations of Parnassius have been saddled with a bewildering array of subspecific epithets that appear more an artifact of the allure this group holds for hobbyists than any natural factor. Parnassius phoebus is known in Europe as “Small Apollo Butterfly” another name which I think would not get past NABA’s name committee unaltered. Here we call it Phoebus Parnassian and it still graces meadows and mountainsides throughout the Rocky Mountains where its foodplant sedum (stonecrop) grows.

Fabricius named it Papilio phoebus in 1793, recognizing with that name its relationship with Papilio apollo, as “phoebus,” which means a ray of the sun in Greek, was often prefixed to Apollo’s name as “Phoebus

Apollo.” Assuming that there are indeed only three full species of Parnassians in North America, I’ve seen all three. But if, as some contend, smintheus and behrii are distinct from phoebus, than I have never seen Phoebus Parnassian, as those who contend smintheus and behrii are distinct only recognize populations in Alaska as being Phoebus Parnassian. (My very scientific approach to questions of lumping and splitting that cuts across all taxa is that if I’ve encountered both populations of something that someone contends are two full species, then I view them as two full species myself and, if I have not, then they are both the same species until I do.)

Assuming that smintheus is a subspecies of phoebus, it is the population that I am most familiar with, as it is the most-easily seen Parnassian in Colorado, where I have spent many summer weeks over the past decades. Smintheus is another appellation that was applied to Apollo, this time as a suffix

Above: Apollo Parnassians still occur on Mount Parnassius. However, where and when this individual was photographed is unknown — clearly a mythological creature.

Opposite page top: Mnemosyne Parnassian. May 30, 2014. Buda Mountains, near Perbál, Hungary.

Opposite page bottom: A Mnemosyne Parnassian with a Southern Festoon friend. April 23, 2016. Perbál, Hungary.

as in “Apollo Smintheus.” The name was derived from “sminthos” meaning a mouse, as mice were symbols of prophetic power in ancient Greece and Apollo was represented in sculptures with mice scurrying at his feet or, on coins, holding a mouse in his hand. But Apollo Smintheus can also be translated as “Apollo, destroyer of mice” and perhaps the sun’s power to drive mice into hiding during the day was also at play. In any event, the name smintheus, which was first applied by Doubleday in 1847, was again given in recognition of this butterfly’s relationship to Parnassius apollo Parnassius phoebus behrii,

32 American Butterflies, Summer 2017

which is a subspecies that flies in the southern Sierra Nevada was named for Hans Hermann Behr (1818-1904) the same German-American doctor, botanist and entomologist for whom Colias behrii (Sierra Sulphur) and Satyrium behrii (Behr’s Hairstreak) were named.

Parnassius clodius, (Clodius Parnassian) is only found in North America. I think of it a California species, as that is where I have seen it most often, but it ranges north and east of California as well. Clodius was probably named for Publius Clodius Pulcher (died 52 BC), a colorful rogue from the pages of Roman history whose life overlapped and

Male Eversmann’s Parnassians are the only parnassians that are stongly yellow-hued. According to C.I.A. agents who hacked into Russian computers to affect the outcome of a butterfly beauty pagent, this individual was photographed somewhere in Siberia.

intersected that of Julius Caesar. Few other historical figures spelled their name “Clodius” as Publius Clodius Pulcher deliberately changed his name from Claudius to distance himself from the aristocratic branch of this important family. Some of the scandals associated with him now are difficult to understand without at least a superficial knowledge of the religious rites practiced by the Romans, but the accusation that he had an affair with the wife of Julius Caesar stands the test of time. This butterfly was named by Édouard Ménétries (1802-1861) in 1857 from collections made in California by Leopold von Schrenk. Ménétries was French and a student of Latreille. But why he chose to name this butterfly after Clodius is not apparent to me.

The other Parnassian in North America does not get into the lower 48 states. Parnassius eversmanni, Eversmann’s Parnassian, is found in Alaska and far

northwestern Canada. It, too, was named by Ménétries, this time in 1850 for the German biologist and explorer, Eduard Friedrich Eversmann (1784-1860) who traveled and collected throughout Russia and Central Asia. The North American subspecies thor was named by Henry Edwards (1827-1891) in 1881 for the Norse god of thunder. Edwards described it as a separate species from Eversmann’s Parnassian, another example of the question whether the similar populations on both sides of the Bering Sea are one taxon or two.

While writing this column, I wondered whether any Parnassians actually occur on Mount Parnassus. I posed the question on my Facebook page and the answer I received from people I think should know is that both Apollo Parnassian and Mnemosyne Parnassian (as I choose to call them in English) occur there. May they long do so.

by Jeffrey Glassberg

Jane Vicroy Scott, died on July 21, 2017, following a three year battle with cancer.

Jane served on the NABA Board and as NABA Secretary/Treasurer since NABA’s inception in 1992. Although her title was Secretary/Treasurer, in reality, she functioned as NABA’s Chief Operating Officer.

Jane was born in Selma, Alabama, on August 16, 1944 to Clarence E. (Vic) Vicroy and Maude Eileen Yeager. Vic was in the U.S. Air Force and, immediately after World War II, was based in England, ostensibly as a meteorologist, but actually as the second in command for communications of the predecessor of the Defense Intelligence Agency (the military counterpart of the C.I.A.) — he was a spy. He would always leave on trips, giving Jane instructions on what to do if he didn’t come home.

Her mother’s family had deep roots in Alabama. In 2000, Jane discovered what is probably the largest population of Mitchell’s Satyrs in the world, in the Talladega National Forest, in Bibb County, Alabama, on land that she later learned had been owned by her greatgreat grandfather.

The eldest of seven sisters, Jane both helped raise the younger siblings and tried to shield them from the brunt of their mother’s frequent wrath. When Jane was deciding upon a name to be called by our first grandchild, the sisters lobbied for “Her Janeness.”

Because Jane’s family was military, she grew up constantly moving from base to base, living at one point or another in ten different states. However, the longest residences were two lengthy stays in England that caused her to become a lifelong Anglophile.

While in England, Jane seriously studied ballet, and her dream was to become a ballerina.

May, 1976. Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.

But, when it came time for her family to leave England, her parents told her that she couldn’t stay there by herself. Rather, she was sent to Hawaii — where, at that time, there was no serious ballet — to help take care of her father’s aging mother. She never quite got over this loss, but continued to love ballet and dance.

Raised a Catholic, Jane first attended college at a small Baptist Woman’s College in Alabama — Judson College (this later proved to be critical for funding the National Butterfly Center). As she did her entire life, Jane managed to fit in, enjoy herself and make lifelong friends.

Jane had always been interested in science in general, and in biology in particular. As a child, she chased butterflies and brought home horned lizards in her pants pockets, trying to learn what made them tick. One time she convinced her parents to allow her to put a dead skunk, which she had found on the road, in their freezer, so that she could dissect it. It was pointless to stand in the way of something that Jane wanted to do. At Judson, the biology teacher was a charismatic, glamorous, independent woman, and so Jane was encouraged to pursue her scientific interests.

After two years at Judson, Jane briefly went to the U. of Hawaii and then transferred to TCU in Texas, where she received both a B.A. and a Masters degree.

From TCU, Jane was admitted to a Ph.D. program at Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston, Texas. While at Baylor, she took a seminar class at Rice University, discussing recent scientific articles about bacteriophage lamba. I was also in that class and, the next year, we became a couple. Our first trip together was to northern Mexico, looking for butterflies.

After earning her Ph.D. in 1976, Jane and I moved to California where she took a position at the University of California, San Francisco while I was at the Stanford University School of Medicine. We lived between them, in San Mateo. This was at the dawn of biotechnology, and many of the breakthrough techniques were being developed in the Stanford Biochemistry Dept., where I worked. So Jane would often come down to Palo Alto, to learn new techniques and get materials. And then, it was easier to get back to our house than to go all the way to San Francisco.

July 17, 2014. Walker’s Drive-In, Jackson, MS. Jane was there to participate in the Delta NF NABA Butterfly Count.

It perhaps provides some insight into Jane’s high-energy approach to life to know that she would eletrophorese Visna virus (the closest known virus to HIV) proteins labeled with radioactive iodine through polyacrylamide gels on top of the washing machine in our garage. After three years in California, we moved to New York City where we both took positions at Rockefeller University.

After I started a biotech company, Jane decided that one of us needed a real job, so she left Rockefeller University and joined Lederle Laboratories (part of American Cyanamid) which was the largest vaccine manufacturer in the United States. Jane quickly rose to become Director of Vaccine Development and one of the highest ranking women in the corporation. If you, or a loved one, received a DPT vaccine from the late 1980s through the mid 1990s, you, or they, got the vaccine that Jane brought to market, as it was the only DPT vaccine then used in the United States.

Jane traveled throughout the world for her work. She went frequently to Japan, where the people at the Japanese pharmaceutical company she worked with referred to her as “strong American woman.” While the Berlin wall was still up, Jane sneaked into East Berlin to attend a meeting. Difficulties ensued.

Because of her expertise with biopharmaceuticals, Jane was selected by the U.S. government to be part of a team that investigated Russian biological warfare facilities following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Despite the work demands, Jane managed to be a wonderful mother to our son, Matthew Scott, and a spectacular grandmother to Hunter and Hayden. She was also, without a doubt, the most fantastic wife in the history of the planet.

Throughout the past ten to 15 years, Jane has worked almost full-time for NABA, without any financial compensation. All that NABA has accomplished is due, in good part, to Jane’s hard work, drive and belief in doing good. She answered the phones with a warm and welcoming tone, she watched NABA’s audited tax returns with a hawk’s eye, she managed payroll, for a short time she was Executive Director of the National Butterfly

Center, she spent the night making sure the contractors were on the up-and-up, pouring the foundation (at 3 am) for the Visitors Pavilion at the National Butterfly Center, she proofread American Butterflies, she made friends of everyone she met, she fashioned the editor of American Butterflies into a semblance of a human being.

Unlike almost all the rest of us, Jane became more beautiful each year, not only as a person, but also physically — at least to my eyes.

Jane was a force of nature — strong, ebullient, and brilliant; yet warm and kind. She made everyone she met feel better about themselves, while accomplishing so much for the world.

Jane’s love, passion and penetrating intelligence are irreplaceable. Jane’s spirit remains strong in the many people she touched.

Top left: June, 1960. England.

Top right: Aug. 13, 1990. Nantucket, MA.

Bottom left: Jane with George Plimpton while he was covering the butterfly count for a major story that appeared in the New York Times Magazine. July 9, 1995. Westchester Co., NY.

Bottom right: Sept. 2001. Convent Station, Morris Co., NJ.

Above: Jane at one with the universe. April 22, 2001. Laguna Atascosa NWR, Cameron Co., TX.

Left: Jane Scott and Jeffrey Glassberg at one with the universe. Nov. 27, 1992. Chappaqua, Westchester Co., NY.

The spring of 2017 began with some unusual butterfly sightings. On Feb 4, Eric Whiteside found 8 Cuban Crescents at the Key West Botanical Gardens, Monroe Co., FL. On Feb. 5, James Lancaster noticed a female Monarch laying eggs throughout a garden in West Riverside, New Orleans, Orleans Parish, LA. She did this for more than 30 minutes. Moving way northward, Steve Glynn saw an American Snout, a Question Mark and a Mourning Cloak near Dividing Creek and Fairton, Cumberland Co., NJ on Feb. 8 — certainly an early date for an American Snout in New Jersey.

Although butterflies fly throughout the year in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas, species diversity in February is normally much lower than later in the year. Not this year. On Feb. 1, Karl and Dorothy Legler found 47 species at Estero Llano Grande State Park, Hidalgo Co., TX and on Feb. 10, Rick Snider tallied 54 species, including 3 Chestnut Crescents, at the same location. Not to be outdone, Dan Jones saw 55 species, including an Angled Leafwing, at the National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX on Feb. 12. Also at the National Butterfly Center, yet another first U.S. record showed up, this one a Mathew’s Groundstreak (Rubroserrata mathewi), seen and photographed by Mike Ricard on Feb. 23.

In California, Brett Badeaux saw 10 species, including Spring White, Sonoran Blue and Desert Orangetip at Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, San Diego Co., CA on Feb. 20.

Florida saw a lot of butterfly activity in February. Walter Wallenstein saw 16 species, including a very encouraging 11 Florida Leafwings and a Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreak in Everglades National Park, Miami-Dade

40 American Butterflies, Summer 2017

by Michael Reese

Opposite page Top

This beautiful Desert Orangetip was photographed by Dennis Holmes on March 3, near McKittrick, Kern Co., CA, nectaring at Douglas’ Fiddleneck. As will become obvious, the editor is enamored of orangetips.

Opposite page Bottom

This spiffy Bramble Hairstreak was photographically captured by Ken Wilson on March 4 in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, San Diego Co., CA.

Co., FL on Feb. 11. On Feb. 19, Julie Appleget saw 11 species, including Great Purple Hairstreak, Henry’s Elfin and White M Hairstreak at Goethe State Forest, Levy Co., FL. Ron Smith noted 15 species, including a remarkable 36 Mallow Scrub-Hairstreaks on Feb. 20 at Fort De Soto Park, Pinellas Co., FL. On Feb. 24, Dave Czaplak saw and photographed an Antillean Daggerwing, an extremely rare stray, at the Key West Botanical Garden, Monroe Co., FL. Linda Cooper saw 31 species, including 13 species of skippers at Three Lakes WMA, Osceola Co., FL.

Elsewhere, in Feb., Rich Kostecke tallied 2 Great Purple Hairstreaks and an impressive 59 Goatweed Leafwings at the Comanche Bluff Trail and Granger Lake, Williamson Co., TX. On Feb. 19, Dave Patton saw and photographed a White-striped Longtail at the Acadiana Nature Station, Lafayette, Lafayette Parish, LA — a range extension for a species that appears to be expanding eastward and northward. Also on Feb. 19, James Shelton found Spring Azures flying in 81 degree weather at Amelia WMA, Amelia Co., VA. Also early, were 11 male Falcate Orangetips, found by Kathy Malone and Kristy Baker at the Cheeks Bend Bluff Overlook Trail, Columbia, Maury Co., TN on Feb. 20. On Feb. 23, Mara Meisel, saw 5 Eastern Commas and 2 Mourning Cloaks along Berry Hollow Fire Rd and Saddle Trail, Shenandoah National Park, Madison Co., VA. Lastly, but definitely not leastly On Feb. 23 Mike Rickard found and photographed a Mathew’s Groundstreak (Rubroserrata mathewi), the first time this species has been recorded from the U.S., at the National Butterfly Center in Hidalgo Co., TX.

By March, butterflies were warming up. On Mar 1, at the National Butterfly Center, Dan Jones saw a Variegated Skipper, an extremely rare stray to the U.S. On Mar. 4, Ken Wilson saw 11 species at Anza-Borrego Desert SP, San Diego Co., CA, including a beautiful Bramble Hairstreak. Also on Mar. 4, William Beck saw a Question Mark, a rare stray here, in Peppersauce Canyon, Pinal

American Butterflies, Summer 2017

Opposite page

Top row

Left: Mike Rickard photo of a Mathew’s Groundstreak (Rubroserrata mathewi) documents the first U.S. report of this species. It is uncommon, even in Mexico.

Right: The first Antillean Daggerwing reported from the U.S. in eight years. Feb. 24, Stock Island, Monroe Co., FL.

Second row

Left: One of the few documented European Peacocks in North America. April 27, Staten Island, NY.

Right:: Pale Crackers are extremely rare strays to southern Florida. This one was seen on April 27 in Richardson Park, Broward Co., FL.

Third row

Left: Another extremely rare stray to the U.S. this Variegated Skipper was seen on March 1 in Estero Llano Grande State Park, Hidalgo Co., TX.

Right:: Three-spotted Skippers appear to be moving northward. This one as at Saddle Creek Park, Polk Co., FL, on March 4.

Bottom row

Perhaps the most easterly record of a White-striped Longtail was seen on Feb. 19 in the Acadiana Nature Center, Lafayette Parish, LA.

Co., AZ and Tom Palmer photographed a Three-spotted Skipper, expanding its range northward, in Saddle Creek Park, Polk Co., FL. On Mar. 11, Laurel and Dusty Rhodes saw 24 species, including Twin-spot Skipper and Little Metalmark, at the Scherer-Thaxton Preserve, Sarasota Co., FL. Moving west, William D. Beck saw butterflies galore, including Spring Whites, Desert Orangetips, Desert Elfins and Sheridan’s Hairstreak, at the south end of the Spring Mountains, near Goodspring, Clark Co., NV. In Dead Man’s Gulch, west of Lyons, Boulder Co., CO, Venice Kelly had to go several thousand feet down the mountain before she saw some early butterflies, including 11 Hoary Commas and 3 Sheridan’s Hairstreaks. Mark and Holly Salvato found 10 Florida Leafwings (just less than the 11 seen here in Feb.) and 2 Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreaks in Everglades NP, MiamiDade Co., FL on Mar. 17.

On Mar. 24, Curtis Lehman, saw a Gray Hairstreak in Forest Hills, Allegheny Co., PA for what may be a new early date for PA. On the same day, across the country, in AnzaBorrego Desert SP, San Diego Co., CA, Brett Badeaux saw 32 species, including Queen Alexandra’s Sulphurs, Leanira Checkerspots, Pearly Marbles, and Painted Ladies beginning their migration northward. Sightings on Mar. 25 finished March with a bang as 12 different reports were received for the day. Mark Adams reported many firsts of the year, including Spicebush Swallowtail, Falcate Orangetip and Silvery Blue, about 10 miles w of Charlottesville, Albemarle Co., VA. In Texas, following an unusually warm spring, Ron Hedden found a number of well-worn butterflies that may have survived the winter, including Great Purple Hairstreak, Gorgone Checkerspot and Dotted Roadside-Skipper by White River Lake, Crosby Co., TX; and Bill Ellis reported that Clytie Ministreaks were common along the Arroyo Colorado, near Rio Hondo, Cameron Co., TX.

There were 371 butterfly reports in April. On Apr. 1, Linda Cooper and 6 others, despite very dry conditions and few nectar

44 American Butterflies, Summer 2017

With the loss of many historic colonies and only a limited number of currently known locations the continued existence of Appalachian populations of Grizzled Skippers has been a source of concern for many years. The fact that NABA VicePresident Jim Springer found three individuals —a high number for this species in the East — on April 16 near Covington, Allegheny Co., VA, is quite heartening.

Another eastern butterfly that is facing hard times is West Virginia White. A combination of habitat loss, climate change and the spread of non-native Garlic Mustard (upon which female West Virginia Whites are induced to lay eggs but the caterpillars die when they try to eat it. Happily, there are still some areas where West Virginia Whites seem to be OK, as you can see in the photo at right. April 14, Connellsville, Fayette Co., PA.

Falcate Orangetips emerged early in Tennessee. This one was at Cheeks Bend Bluff Overlook Trail, Columbia, Maury Co., TN. Feb. 20, 2017.

sources, managed to see 46 species, including 22 species of skippers, at Bull Creek WMA, Osceola Co., FL. On Apr. 3, on the first warm day of the season, Rob Santry saw newly emerged Mustard Whites, Sara Orangetips and Spring Azures at Fish Hatchery Park, Josephine Co., OR. On Apr. 5, Chris Blazo, butterflying Red Rock Rd. along Licking Creek, Franklin Co., PA, saw 10 species including Zebra Swallowtails (which seem to be expanding northward), Sleepy Duskywings, and Juvenal’s Duskywings. On Apr. 8, Mark and Holly Salvato found a Fulvous Hairstreak at the Turkey Creek Sanctuary, Brevard Co., FL. On Apr 12, Dennis Holmes found San Emigdio Blues to be abundant in Victorville, San Bernardino Co., CA. Edward Perry reported that, on Apr 12, Bull Creek WMA continued to be very dry however, “Like an oasis in a desert, some purple thistles had as

many as six species of butterflies on a single bloom!” yielding a total of 38 species. More than 1000 duskywings, with probably 75% being Juvenal’s, were seen by Robert Bell on Apr 13 in the Shawnee SF, Scioto Co., OH. Jim Springer’s report of 250 Juvenal’s Duskywings, near Covington, Allegheny Co., VA on Apr 16, was accompanied by more critical report of 3 Grizzled Skippers — very rare butterflies in the East. Three Goatweed Leafwings, very rare in Iowa, were reported by Chris Edwards from the Farmington Unit of the Shimek SF, Van Buren Co., IA. On Apr 20, Denis C. Quinn reported a very early Monarch at Havre de Grace, Harford Co., MD and the same day, Matthew Dilley also saw a Monarch, this one in Manheim Township, Lancaster Co., PA. The next day, Apr 21, another Monarch was seen in farther to the north, in Armstrong Co., PA,

A Sara Orangetip models for Vogue Butterflies. Fish Hatchery Park, Josephine Co., OR. April 3, 2017.

these butterflies is unknown, but perhaps the most likely possibility is that they had pupated in a shipment sent from Europe to Kennedy Airport and subsequently eclosed and flew off. by Curtis Lehman, who also reported a very early Cloudless Sulphur, seen on Apr. 30 in Washington Co., PA. Also on Apr. 30, Jeanette Klodzen saw an Anise Swallowtail and a Mourning Cloak with temperature in the low 50s at about 6400 ft. on the Little Cottonwood Creek Trail, Salt Lake Co., UT. A Pale Cracker, an extremely rare stray to southern Florida, was seen and photographed on Apr. 26 by Mary Beth and Billy Mullgan, in Richardson Park, Broward Co., FL.

Confused Peacocks. There were two reports in April of European Peacock (Aglais io) in the New York City area. On Apr. 11, Rich Kelly saw a fresh European Peacock at Muttontown Preserve, Nassau Co., NY and on Apr. 27, Alan Pieluszynski photographed a European Peacock on Staten Island (report forwarded by Harry Zirlin). The source of

Whether you see an unusual butterfly, an early or late sighting of a common species, or have a complete list of the species you have seen, we would appreciate hearing from you. Please send your butterfly sightings to sightings@naba.org. Those who record your sightings to the Butterflies I’ve Seen website can just click on “email trip” and send it to the address given above. Your sightings will go into the larger database and will also be available for others to see on the Recent Sightings web page.

Jan Dixon is retired from a career in counseling and teaching. She has a Ph.D. in psychology. New-found time brought an opportunity to pursue a deep interest in birds and quickly develop a passion for butterflies. She planted butterfly gardens in two Ohio home locations — one in Holland and a second, developed over the last four years, in Perrysburg after a move. Jan has experienced the joy of raising nine different species of butterflies from host plants in her gardens. As a volunteer, she has been involved in butterfly research with the Nature Conservancy at the Kitty Todd Nature Preserve for the past twelve years.

Don Dubois’ brief biographical appeared in the Spring 2017 issue of American Butterflies.

Jeffrey Glassberg is a director and president of NABA. Jeff has followed butterflies since he was 5 years old living on Long Island, New York. He detoured to take an undergraduate degree in civil engineering and a Ph.D. in molecular genetics, then worked at Stanford University and Rockefeller University. In 1981 he invented DNA fingerprinting and co-founded a biotechnology company (Lifecodes) that commercialized this technique. Jeff is a past-president of Xerces Society, the author of the ‘Butterflies through Binoculars’ field guide series, the editor of the ‘through Binoculars’ series (including Caterpillars, Dragonflies and Wildflowers) and the author of A Swift Guide to the Butterflies of Mexico and Central America and of A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America. He

graduated from the Columbia University School of Law in 1993 and is a member of the New York bar. He is an adjunct professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Rice University.

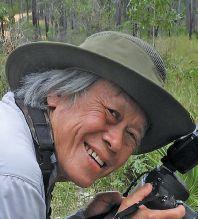

Dean Jue, a birdwatcher and avid outdoor photographer for more than 30 years, began concentrating on butterflies in 2001. He received his undergraduate degree in zoology from the University of California at Berkeley. As research faculty at Florida State University (FSU), he coordinated the collection of distribution data for Florida’s rare and threatened butterfly species on conservation lands throughout the state. Now retired from FSU, he continues to conduct local butterfly surveys with his wife Sally and travels both domestically and internationally to see and photograph butterflies. He serves on the steering committee for the Imperiled Butterflies of Florida Work Group.

Mike Reese updates the NABA Recent Sightings web pages. He enjoys photographing wild flowers, birds, dragonflies, and, of course, butterflies. He is an educator in Wautoma, Wisconsin and has been recording and documenting the butterflies that are found there for over 15 years. He also maintains a website on the Butterflies of Wisconsin.

Harry Zirlin’s fascination with butterflies and other insects dates to his early childhood. He travels extensively in the United States, studying and photographing butterflies. He supports this passion by working as an attorney in the environmental area at the New York law firm of Debevoise & Plimpton.

The Gorilla Speaks.

Just read your editorial about population in the latest issue of American Butterflies. Right on! We’ve been reading the book Drawdown by Paul Hawken. Two solutions to the population problem are family planning and the education of girls. As it turns out, those solutions are both in the top 10 out of 100 solutions for climate change.

Susan Goldstein, Oakland, CA

We are NABA

Thanks for publishing the interview with Marianna Wright. The information about how different demographics respond to plants and animals is insightful. I had no idea that some people are afraid of butterflies! I think everyone involved in environmental education needs to read this article, so that they have a better understanding of how to reach every individual. We need everyone on our side; those who love butterflies and those who hate them. Marianna provided some important information that could lead to better approaches to teaching some students.

Sal Levinson, Berkeley, CA

(continued from page 88)

NABA is thrilled to announce that we will soon be making available to the public new pages, at www. webutterfly.org. The website will allow the public to see the NABA Butterfly Monitoring Program data, including data from the 4th of July, 1st of July and 16th of September counts, displayed as maps and graphs. One can learn about the abundance of butterfly species and how they vary from year to year. The web pages will also include photos and information about all North American butterflies.