NABA and the National Butterfy Center in the News

Recently, NABA and the National Butterfly Center have been very much in the news. Here are a few (of many, many) articles that you might want to see:

https://www.texasmonthly.com/the-culture/ doerte-weber-checkpoint-carlos-border-artberlin-wall/

https://www.dallasobserver.com/news/butterfycenter-on-border-is-tip-of-the-spear-in-borderwall-battle-11570047

https://thehill.com/opinion/energyenvironment/431262-property-rights-versusthe-wall

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/landowner-onsouthern-border-suing-trump-administrationnational-emergency-declaration/

Many NABA members enjoy receiving print copies of American Butterfies and of Butterfy Gardener. Other members prefer to receive their copies in digital form. Moving forward, those members with a regular membership will choose one form of publication delivery — either print or digital. Those members with family, copper and other supporting memberships may continue to receive both print and digital versions, although these members can also choose to receive only print, or only digital, if they so desire.

NABA is offering free trial memberships to people who have not previously been NABA members, if they help NABA monitor butterfies by entering data into the Recent Sightings page and/or participate in the NABA Butterfy Count program. The free, trial membership includes access to digital versions of NABA publications

as well as access to NABA-Chat and other NABA programs. So, invite your friends, family and neighbors to participate in Recent Sightings and/ or the Counts, helping to monitor and conserve butterfies throughout North America — they will be rewarded with a free, trial membership.

Artists interested in entering the 2019 NABA Art Contest should submit digital images of original two-dimensional color “paintings,” in any medium. The digital fle name should include the artist’s name, should be from two to fve MB, and should be sent to naba@naba.org. Higher resolution images will be requested, if needed. If realistic, the painting should depict species found in Mexico, the United States or Canada. In your cover letter, please indicate the dimensions of the original work, give a description of the medium of the work, and provide a release granting to NABA the right to copy and publish the image. Please include a telephone number and email address where you can be reached. Submissions need to be received not later than June 1, 2019. Winning artist will receive a prize of $500, 2nd place winner will receive $125 and winners and honorable mentions will have their works published in color in the Fall 2019 issue of American Butterfies. All decisions of the judges are fnal.

Continued on inside back cover

Front cover: Rosy maple moth ( Dryocampa rubicunda ). 2016 June 18. Guernsey Co., OH, Photo by Steven Russell Smith. See silkmoth article on page 4.

The North American Butterfy Association, Inc. (NABA), a non-proft organization, was formed to promote public enjoyment and conservation of butterfies. Membership in NABA is open to all those who share our purpose.

President: Jeffrey Glassberg Vice-president: James Springer Secrty./Treasurer

Ann James Directors: Jeffrey Glassberg

Fred Heath

Yvonne Homeyer

Ann James

Dennis Olle

Robert Robbins

James Springer

Patricia Sutton Scientifc Advisory Board

Nat Holland

Naomi Pierce

Robert Robbins

Ron Rutowski

John Shuey

Ernest Williams

Volume 27: Number 1 Spring 2019

Inside Front Cover NABA News and Notes

2 Balancing the U.S. Constitution on a Butterfy’s Back by Jeffrey Glassberg

4 Giant Silkmoths by Jesse Babonis

14 A New Jersey Butterfying Big Year by Steven Glynn

22 You Are What You Eat

23 Bordered Patch on Straggler Daisy in Texas by Jan Dauphin

28 We Are NABA: Jane Hurwitz interview by Mike Cerbone

30 Taxonomists Just Wanna Have Fun: Tangled Up in Blue by Harry Zirlin

40 Hot Seens by Mike Reese

48 Contributors

Inside Back Cover Readers Write

American Butterfies (ISSN 1087-450X) is published quarterly by the North American Butterfy Association, Inc. (NABA), 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; tel. 973285-0907; fax 973-285-0936; web site, www.naba.org. Copyright © 2019 by North American Butterfy Association, Inc. All rights reserved. The statements of contributors do not necessarily represent the views or beliefs of NABA and NABA does not warrant or endorse products or services of advertisers.

Editor, Jeffrey Glassberg

Editorial Assistance, Matthew Scott and Sharon Wander

Please send address changes (allow 6-8 weeks for correction) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; or email to naba@naba.org

As you read this, much of the remaining 5% of native habitat in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the most biodiverse portion of the United States, is being destroyed. Giant tree-eating machines are turning native vegetation into toothpicks in a matter of minutes (this youtube video demonstrates the machines’ surreal capabilities — https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=LYKg0gbRFns&fbcli-d=IwAR3Y2t rx76LR13cceFyO0RXPsgc5wVqDHyJLdHm Lfg6YLPWRXqWfRgZ40Rk), crushing baby birds in their nests at the same time. They’re currently doing this at what were “National Wildlife Refuges” paid for with 10s of millions of your tax dollars.

But soon, they plan to move on to private property, including the National Butterfy Center (NBC), in Mission, Texas. The trampling of private property rights and individual liberties at the NBC directly affects NABA’s mission to conserve butterfies. But it also affects the constitutional rights of all Americans.

The United States’ Constitution’s fourth and ffth amendments — barring unreasonable searches and seizures or the taking of private land without due process and just compensation — are all that stand between you and your family and a police state.

For the past year and one-half, the federal government has been conducting unreasonable searches and seizures at the National Butterfy Center (and throughout the Rio Grande Valley), targeting NBC employees and guests, targeting U.S. citizens on the basis of their ethnicity, and taking NABA’s land, planting sensors and cameras, destroying vegetation, without due process or just compensation. On Valentine’s Day this year, a federal judge, dismissed the lawsuit that NABA fled in Dec.

2017 seeking to stop these actions. NABA intends to appeal the Valentine’s Day massacre.

You may think “Well, that’s too bad, but this won’t have a direct impact on me because I don’t live near the U.S.-Mexican border.”

Think again, because the justifcation for this abrogation of constitutional rights says that Customs and Border Protection offcials can take these actions “within a reasonable distance from any external boundary of the United States” and reasonable distance is sometimes defned as 25 miles, sometimes as 100 miles and sometimes undefned. Onehalf of the U.S. population lives with 25 miles of an external boundary and two-thirds of the population lives within 100 miles of a boundary. Did I mention international airports? That means you Denver, Kansas City and Nashville.

The militarization of the borders is part of a larger trend toward creating expanded police and national security powers more characteristic of a dictatorial autocracy than of a constitutional democracy. It’s not a coincidence that the current U.S. administration is friendlier to Russia and North Korea than it is to Canada and France.

Tell your congressional representatives and senators that Customs and Border Protection need to be brought under control, stopping their lawless actions.

Today, they’re coming for the National Butterfy Center and butterfies, tomorrow, it’s for you and your family.

(Did I forget to mention that the federal government is monitoring all telephone and other communications

Please photocopy this membership application form and pass it along to friends and acquaintances who might be interested in NABA

Yes! I want to join NABA, the North American Butterfy Association, and receive American Butterfies and The Butterfy Gardener and/or contribute to building the premier butterfy garden in the world, the National Butterfy Center. The Center, located on approximately 100 acres of land fronting the Rio Grande River in Mission, Texas uses native trees, shrubs and wildfowers to create a spectacular natural butterfy garden that importantly benefts butterfies, an endangered ecosystem and the people of the Rio Grande Valley.

Name:

Address:

Email (only used for NABA business):______________________ Tel.:______________________

Special Interests (circle): Listing, Gardening, Observation, Photography, Conservation, Other

For a $35 donation, one receives NABA publications as either digital or print. All higher levels of donations receive both digital and print versions. Outside the U.S., only digital is available, at any donation level.

Tax-deductible dues (donation) enclosed (circle): Regular $35 (must choose either digital or print — circle one), Family $45. Special sponsorship levels: Copper $55; Skipper $100; Admiral $250; Monarch $1000. Institution/Library subscription to all annual publications $60. Special tax-deductible contributions to NABA (please circle): $125, $200, $1000, $5000. Mail checks (in U.S. dollars) to NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960.

American Butterfies welcomes the unsolicited submission of articles to: Editor, American Butterfies, NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960. We will reply to your submission only if accepted and we will be unable to return any unsolicited articles, photographs, artwork, or other material, so please do not send materials that you would want returned. For the type of articles, including length and style, that we publish, refer to issues of American Butterfies

Occasionally, members send membership dues twice. Our policy in such cases, unless instructed differently, is to extend membership for an additional year.

American Butterfies welcomes advertising. Rates are the same for all advertisers, including NABA members, offcers and directors. For more information, please write us at: American Butterfies, 4 Delaware Road, Morristown, NJ 07960, or telephone, 973-285-0907, or fax 973-285-0936 for current rates and closing dates.

If you have questions about missing magazines, membership expiration date, change of address, etc., please write to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960 or email to naba@naba.org.

by Jesse Babonis

While most of us are familiar with the numerous and beautiful butterfies we encounter during the day, some of the largest and most majestic lepidopterans are more active at night. Unless we know what we’re looking for and how to fnd them it’s easy to overlook these nocturnal denizens of our felds and forests. The giant silkmoths, in the family Saturniidae, are a diverse and colorful group of about 1500 moth species that are native to every continent except Antarctica. Roughly 80 species can be found in the United States. Despite the name “giant silk moths” they range in size from the small, candy-colored, Rosy Maple moth (Dryocampa rubicunda) to North America’s largest lepidopteran, the Cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia). Primarily nocturnal, there are a few notably diurnal saturniids, such as the buckmoths and sheepmoths in the genus Hemileuca

This page: A male cecropia moth. June 15, 2016. Allen Park, Wayne Co., MI.

Opposite page: How spectacular is a cecropia moth caterpillar just after shedding its skin? July 1, 2016. Allen Park, Wayne Co., MI.

I remember my frst encounter with a saturniid. I was in the third grade and I had found a luna moth (Actias luna) roosting in a lilac bush near my school bus-stop. Although I had only seen them in books, I instantly recognized it. The experience was magical! It was amazing that such a colorful, exotic looking moth was right there near my house in Pulaski County, Missouri. I wanted

desperately to capture it but I was pretty sure that this was something rare and special, so I observed it in the lilac bush until my attentions grew too much for it and it few off. That luna moth made a lasting impression on me and I was hooked on saturniids from that point on. Because I was so young and inexperienced, I had no idea how common and widespread some of the giant silkmoths really are. Even though they are not commonly observed, several species of these moths are abundant in many parts of the United States.

How does one encounter a giant silkmoth? That can take a little planning. Unlike most North American moths, adult saturniids have

no functioning mouthparts and do not feed. Therefore, it’s useless to try to attract them with any type of food that you might think would be enticing. A great and easy way to observe nocturnal saturniids is through the use of night lights. I use black lights, while some of my friends prefer mercury vapor lights. Either way, it’s possible to create a decent and inexpensive set up. I hang my black lights on a clothesline over a white sheet and run them off of an extension cord from my barn. It’s not the most portable set-up, but I think it works great for my simple curiosity.

Because I enjoy observing all manner of insects attracted to lights, I turn my black

lights on just before sunset. Where I’m currently living, in northeastern Pennsylvania, it doesn’t seem like many of the Saturniids really start fying until 10 or 11pm, so I don’t get discouraged if none show up to my lights right away. It’s best to run your lights for only a few hours and then shut them down, so that the moths you’ve attracted can continue on with their natural behaviors. The next morning I’ll check the trees and bushes around my light set-up, as I’ll often fnd moths still roosting there.

If you don’t want to invest the time and money into your own light set-up, a great place to fnd giant silkmoths might be at your

local 7-11! Many gas stations and convenience stores run high-powered lights all night. A diverse population of local moths can be attracted by these lights, especially on the rural edges of a community. You might get some funny looks, stalking around a convenience store at night with a camera in hand. But I fnd that once I explain why I’m there (always a good idea by the way) and what I’m up to I’m met more often with curiosity than anything else.

Attracting diurnal silkmoths can be a little trickier, since they aren’t attracted to lights like their nocturnal counterparts. Pheromones are probably the most reliable method for

Above: A Glover’s silkmoth caterpillar (Hyalophora columbia gloveri). Sept. 8, 2012. Garden Canyon, Cochise Co., AZ.

Opposite page

Top: A silkmoth in the genus Eacles. Oct. 21, 2014. Napo, Ecuador.

Bottom: A Common Sheepmoth (Hemileuca eglanterina). July21, 2007. Phillips Canyon, Teton Co., WY.

attracting the day fiers. Pheromones are the chemical substances that these moths use to fnd each other when it’s time to breed. Within hours of emerging from her cocoon, a female Saturniid moth will start producing and releasing pheromones to attract a mate. This is referred to as “calling”. When she calls, the pheromones she produces disperse through the environment on the breeze. Male saturniids have large, feathery antennas that are specifcally designed to detect and follow a female’s pheromone trails over vast distances. I’m always amazed at how a male can home in on a female from miles away despite changes in wind current and direction, weather patterns, and physical obstacles.

While there are some types of synthetic moth pheromones commercially available

for purchase, I don’t really know much about them and I have never used them. My experience lies in rearing caterpillars through to adults, or fnding cocoons, and then keeping a female outdoors in an airy screen cage while she releases her pheromones. Once she starts calling it does not take long for the local males to appear! A few years ago, I found a dozen Promethea moths (Callosamia promethea) cocoons during the winter. I kept them in a screen cage outdoors, and in late May the moths started to eclose. I released the males that emerged as soon as they were able to fy, and I kept the female in the cage on my porch while she called. It was only a matter of ten minutes or so before the frst male showed up, attracted by the female’s chemical scent trail. In less than an hour, there were seventeen

male Promethea moths circling the screen cage, trying to get to the female. What a sight to see!

Rearing giant silkmoths is probably my favorite aspect of these regal insects. In my opinion, there is nothing more exciting than hatching tiny eggs and watching the caterpillars grow and change through each instar until they pupate and become a perfect, spectacular moth.

It’s imperative that you do some research into suitable host plants for the caterpillars before the eggs hatch. Some species are polyphagous and will readily accept a number of different foods. Others can be quite particular in their dietary requirements, making it more of a challenge to rear them successfully. Because it can be diffcult to keep deciduous leaves alive and fresh for an

extended period I prefer to rear my caterpillars in mesh sacks, called “sleeves”, directly on their host plant. Cut branches tend to wilt and wither in a matter of a couple of days. When you sleeve your caterpillars on a host plant you ensure they have ready access to fresh, living, food at all times. Additionally, the natural air fow, sunshine, and precipitation that your caterpillars receive while living in an outdoor environment helps to reduce the chance of disease and can lead to larger, healthier caterpillars.

Sleeves for rearing saturniid caterpillars can be made out of any number of materials. Most of my sleeves are made from old, sheer, curtains that I already had on hand. Some of my friends, who rear caterpillars on a larger scale, purchase bolts of military-grade mosquito netting to fashion into sleeves. The

choice of cloth just depends on what you have access to and can afford.

Size and style of your rearing sleeves depends a lot on what species you are rearing and how many you want to raise. Most of my sleeves are about three feet long and two feet wide. A sleeve this size is suitable for raising at least a few caterpillars of any of the native U.S. saturniids. As you can imagine, a sleeve designed to house a dozen Polyphemus caterpillars (Antheraea polyphemus) may only be suitable for three or four of the massive hickory horned devils (caterpillars of the Regal moth, Citheronia regalis). Overcrowding your caterpillars is defnitely something you want to be aware of and avoid. Some saturniid caterpillars, such as the Io moth (Automeris io) and the eastern buckmoth (Hemileuca maia), are gregarious through at least their frst or second instars. After that, though, they need a little more space. If kept in too close quarters your caterpillars won’t

grow to their full potential and you will risk problems with disease.

Check your sleeves on a daily basis! As your caterpillars grow, their dietary needs will change radically. A branch that can feed fve, second instar, luna moth caterpillars for a week may only feed the same number of fourth instar caterpillars for a day or two. Some species, like the voracious Io moth caterpillars, have been known to chew through cloth sleeves when they start to get low on food. Holes in your sleeves are not only a means for your caterpillars to escape, but they can also be a point of entry for parasitoids and predators.

A daily sleeve check can be a rewarding experience. Not only are you ensuring the peace of mind that comes with knowing your caterpillars are healthy and happy, but you are also getting a frst-hand look at a life cycle that often remains hidden in nature. Few people are lucky enough to be able to observe

A sagebrush sheepmoth (Hemileuca hera) is dressed for a formal affair. Aug. 21, 2010. Sun Lakes, Grant Co., WA.

the saturniid life cycle, from egg to adult, in a wild situation. The changes in color and morphology that saturniid caterpillars undergo as they mature are incredible!

As your caterpillars grow and mature, pupation is something that needs to be considered. Depending on which species you are rearing, their needs may be very different. Caterpillars of moths in the subfamily Saturniinae, such as the luna moth or Polyphemus moth, will build their cocoons in the leaves of their host plants. Caterpillars of moths in the subfamily Ceratocampinae, such as the regal or the imperial moth (Eacles imperialis) need to be able to go underground to pupate properly. Ceratocampines can be a little tricky, but if you’re observant and you know what to expect you shouldn’t have any trouble. There is often a signifcant change in color and behavior that preludes the Ceratocampine pupation. You will also notice a change in your caterpillars’s frass. Before pupation, the caterpillars of both subfamilies will produce a larger-than-normal amount of runny excreta as they clear their gut. This can be unnerving, as runny excrement can also be a sign of infection and disease in your stock. In addition to the emptying of their gut, you may notice that your caterpillars’s prolegs will start shriveling up and your caterpillars will have diffculty clinging to the branches of their host plants. This is the start of their wandering phase. During their wandering phase the caterpillars look for a suitable place to burrow underground and pupate. If a suitable substrate is not provided for them, your caterpillars may not pupate properly and may not survive. I have great luck getting my Ceratocampines to pupate by placing wandering caterpillars in large containers of damp substrate. A fve-gallon bucket with six to ten inches of moistened peat moss in it is an easy and convenient way to facilitate their need to burrow. Once they dig underground they should be allowed to remain there, undisturbed, for at least 30 days. This gives them a chance to pupate normally and for their

pupal case to harden enough to handle without damaging it.

After pupation occurs, the waiting begins. Depending on the species of moth and your regional climate, you may have to wait longer than a year for your moths to eclose, or emerge from their cocoons. Some species, such as the luna moth, can be bivoltine or even multivoltine in warmer climates. This means that they may produce more than one brood in a year. Those that overwinter as pupas emerge in the spring, breed, and produce a summer brood. The summer brood hatches, grows, and pupates and, if the weather is conducive and the growing season is long enough, they may produce a third brood of caterpillars. This isn’t a very common occurrence in the US, and typically it is the summer brood will spend the winter as pupas. Other species, such as the regal moth, are naturally univoltine, producing only one brood in a year. Once those species pupate they won’t be seen again until they are adults, next year. Some pupas may even take more than a year before they eclose. Patience is key when rearing univoltine saturniids.

The culmination of all of your hard work, vigilance, and patience comes when your adult moths emerge from their pupal state. It is such a thrill to see a perfect adult moth expanding its wings, knowing that this incredible creature was once a tiny caterpillar that you sheltered and raised. Once its wings are fully expanded and dry you can immediately release this beauty back into the wild. Responsible stewardship is the key to ensuring that you will be able to observe and enjoy these creatures for years to come.

by Steven Glynn

in many of our country’s great areas and have thrilled at the chase for new lifers. However, understanding and enjoying all the butterfying opportunities that our native state offers us is usually a launching point to greater exploration afeld. So has my butterfying experience been, and dedicating myself to a New Jersey “Big Year” was perhaps a natural extension of my overall butterfying experience.

When it came to doing a “Butterfy Big Year,” I admit that I was already planning for it since about October of 2016. The impetus to a 2017 Big Year was my frantic search, at the end of the 2016, for a sighting of a Pipevine Swallowtail. Had I found it, it would have marked my 100th species for the 2016 season. Falling short of the century mark, with 99 species, chafed me. Now, truth be told, I didn’t actually realize how many species I had seen that year until a friend asked me late in July if I was doing a big year and where I stood? It wasn’t until that point that I actually added up the species count within the state and set a goal to get to 100. Having fallen so close, I began to plan during that winter for the 2017 season and set my goal on fnding and photographing 100 species. Any higher number, beyond 100, would be a secondary goal.

The author harvested a sighting of a Feniseca tarquinius on Aug. 22, 2017. Chestnut Branch Park, Gloucester Co., NJ.

Above: A broken-dash that might be a Southern Broken-Dash, a Northern Broken-Dash, or a hybrid. July 17, 2017. Cape May, NJ.

Right: A Hessel’s Hairstreak, one of New Jersey’s specialties. Apr 29, 2017. Peaslee WMA, Cumberland Co., NJ.

Having a career that provides opportunities to travel regularly throughout my home state gave me a full view of the possibilities to fnding as many, or perhaps even “all”, of the species that can regularly be found in the state.

I knew from online and NABA regional group resources where and when specifc species might be fying, but for some species, it would be a matter of seeking and fnding purely on my own. It was expected that skill and luck would play a role in my yearly achievements. And it did.

Above: Leonard’s Skippers, with only a few colonies remaining, are fast disappearing from New Jersey. Aug. 20, 2017. Near High Point SP, Sussex Co., NJ.

spotted Skipper in June could be “make or break” species when doing a true run at a total yearly species pursuit within New Jersey. Many other rare or seldom-seen species would also be important to a full run. For me, early success with all of the keys species told me that I was probably on to something larger than the “Century Run” I set as an immediate goal.

Another key to my pursuit would be to not only fnd and see each species, but I also wanted to confrm every species seen with a photograph. This concept might have been a limitation to anything beyond a “Century Run”, but I wanted to set a high bar for my year and have photo documentation along the way. I would document each species with a photo and post a regular tweet on my Twitter account for those who follow me. I soon had followers contacting me and enjoying my pursuits, often providing encouragement and private messages of support. To this end, I was proud to have photographed 107 of my 108 species. The only species I was not able to photograph, but was fortunate to have seen and confrmed with fellow butterfying enthusiasts Jack Miller and Harvey Tomlinson, was the very elusive Brazilian Skipper that raced through fellow-NABA member Beth Polvino’s wondergarden on the morning we were all there hoping to get a glimpse. This brief glimpse remains my biggest “grrrrrrr” moment, and blemish on my photographic record.

From the beginning of the year, I viewed my butterfying year as being primarily a “Century Run”, and a true pursuit of a “Big Year” only unfolded as I had success with certain key species that I knew would be the most challenging to fnd. Certain species, such as Hessel’s Hairstreak in April, Cobweb Skipper in May or Two-

Heading into the 2017 year, I knew that the amount of travel would be considerable, as my ability to be in a specifc place at a specifc time might not match with an appearance of the butterfy I might be chasing at that point and time.

Living in deep South Jersey, the number of trips that I would need to take to Sussex County, in far northwestern North Jersey, was somewhat daunting, both in terms of time and expense. But, for any serious effort, I would need to undertake such travel, and at several different times of the year. Want to fnd Common RoadsideSkipper or Pepper and Salt Skipper? Be ready to go north in May. Want to fnd Aphrodite Fritillary? Be on the road in August. Leonard’s Skipper too? Head back up in September. And any of these trips could provide a great opportunity to fnd none of the species. It was also possible, if not probable, that some species would be fying early in a given month, but another regional specialty may not appear until a couple of weeks later. This is and was the case. In total, I

think I made about twelve day-trips from my home in Cumberland County, near the Delaware Bay, up to and through the counties of northwestern NJ. When you add in the additional mid-state trips for pine barrens specialties like Georgia Satyr, Two-spotted Skipper, Hoary Elfn and Dotted Skipper, the travel requirements do become rather daunting. A key to any of this was knowledge about the month to month expectations for species’ emergence and effective scheduling for the necessary travel. The excitement of the pursuit is one thing, and each species fnd keeps you in the game, but there come moments during the year that you really question yourself and have your doubts. I’m ever mindful of how blessed I am to pursue such an endeavor, but it’s not lost on me how frivolous some might view this, so

it’s not something I’d herald or deem appropriate for an every year attempt.

As with any such endeavor, planning and seeking advice or direct assistance is always useful to meeting the goal. For me, my success was augmented with help from fellow butterfiers and the kindness of private land owners who opened their properties up for my searches. Though I did the vast majority of my searches on my own and under my own planning, I did reach out to the NABA North Jersey chapter and to Jim Springer, in particular, for feld tips on some butterfies that I had no prior New Jersey experience with. These NJ lifers were a satisfying highlight to the year. I count amongst them my fnding of Appalachian Azure, Pepper and Salt Skipper, Dreamy Duskywing,

Opposite page: Milbert’s Tortoiseshells rarely are seen in New Jersey, being much more common to the north and northwest. The author was fortunate to see this one on Oct. 25, 2017. Danville, Morris Co., NJ.

Bronze Coppers are seen regularly in New Jersey, but unless one knows exactly where to go, one is very unlikely to see one. This one was seen on July 16, 2017. Canton, Salem Co., NJ.

Indian Skipper, Long Dash, Black Dash, Aphrodite Fritillary and Milbert’s Tortoiseshell.

The big take-away from my “Big Year” pursuits would be how beautiful, but fragile butterfy colonies are and how easy it is to imagine how the habitat can be destroyed or altered enough to cause colonies to fail. In preparation for the year, reading about New Jersey butterfying is left to a very limited selection of now outdated materials and some online feld note sightings. For many species, the numbers are simply not what they once were and the places have changed through succession and development, so I cannot imagine doing a state-wide pursuit without a good foundation of knowledge about the state

of butterfies as represented today. The database of sightings that we do for the South Jersey Butterfy Blog and the embedded notes we provide within our sightings is perhaps the very best information for anyone who might be seeking to fnd the most species. Our blog plays a very big role in providing current and valuable information. Though we must be cautious to guard the endangered species, we still provide guidance for the relative timing for those who seek these species and know the care that must be taken in their pursuits.

2017 will hold special meaning for my “Big Year” pursuits, but within my year was the special honor of working with The New Jersey Division of Fish & Wildlife on land management within a local, Cumberland County, wildlife management area for the augmentation and safe guarding of a Sleepy Orange colony I discovered and monitored throughout the year. The potential for this colony to exist began with my 2016 discovery of one male and two female Sleepy Oranges fying within a feld that had a good amount of Maryland Senna, the butterfy’s

caterpillar foodplant, growing within it. Perhaps with only blind optimism to go on, I had thoughts that perhaps these three individuals, within a feld of host plant, might just be the outliers to support a future colony. Seeing them fying in this feld throughout most of the 2016 summer fight season, I was very eager to see if 2017 would bring my wish to fruition.

Beginning in the spring, I contacted the regional NJF&W offce and presented my notes on the potential for the Sleepy Oranges to emerge in this spot within the Dix WMA. I was pleased to fnd willingness and cooperation to do special caretaking for the felds that held the host plant. Time would tell at that point.

Then, in June, the frst overwintering adults emerged in the same feld! By July, breeding was noted and female egg laying was occurring. In late August, an emergence was witnessed and the feld counted.

To my knowledge, this colony may be the frst documented record of breeding Sleepy Oranges for the State of New

Opposite page Sleepy Oranges, moving north with climate change, have recently colonized New Jersey. Far left, July 28, 2017; left, Aug. 13, 2017. Both in Dix WMA, Cumberland Co., NJ.

Jersey. The colony emerged during the late summer and had a high count of thirty-three counted individuals fying. I grew very fond of this species and was proud to spend time visiting and monitoring the area in my loose attempt to protect the colony and the special felds that supported the butterfies. As the year nears its end, I continued to fnd Sleepy’s fying into November and have great hopes that the 2018 season will see a renewal of this colony, and I will continue my work to protect the area for future seasons to come.

Looking back now, I think of the fortunate fnds I had and how few misses I endured. Any season will see some butterfies in relative abundance or scarcity. In 2017, that held to form. A very strong fight season for American Snout was heralded with the early February record sighting that Harvey Tomlinson and I had in Cumberland County, my frst butterfy of the year. Unlike 2016, this year fnding Painted Ladies proved to be no problem. But secretive and scarce species like Harvester and Hickory Hairstreak proved to be my toughest challenges, with great

success with the former, but no success with a confrmation of the latter.

Many other scarce or endangered species held their own challenges for me, and seeing land use changes for the Bronze Copper colony I’ve monitored in Salem County for several years was a particularly negative circumstance I witnessed.

I’m delighted with the number of species I found. I regret not chasing the Common Roadside-Skipper, which is only found on a few mountain ridgelines in Northwestern NJ, but had to make a business choice on the date I planned for and never reconsidered another attempt for it. My biggest miss was the several attempts I made for Compton Tortoiseshell. This would have been a NJ and personal lifetime sighting for me, but to my knowledge no Compton Tortoiseshell sightings were recorded within the state during 2017 from any butterfy enthusiasts.

Beyond the exceptional rarity, such as Beth Polvino’s amazing Great Purple Hairstreak that graced her gardens and marked the frst sighting of this species in New Jersey in over 100 years (!), I found everything else I tried for. I saw almost 99% of the expected or probable species found in the state during my year. I was also able to re-fnd Southern Broken-Dash, a species frst found last year by Harvey Tomlinson and was a new state record then.

My “Big Year” provided a lot of memories, but I am equally grateful for the friends and connections I made on my journey and the many moments that I could share my joy of butterfying with others.

All photographs this article by Steven Glynn

We have initiated a project to document the caterpillar foodplants of North American butterfies. For those who would like to participate in this photodocumentation, here are instructions:

Find an egg or a caterpillar (or a group of eggs or caterpillars) on a single plant in the “wild” (this includes gardens). The plant does not need to be native to the area — we want to document all plants used by North American butterfies.

Follow this particular egg or caterpillar (or group of eggs or caterpillars) through to adulthood, with the following documentation.

1. Photograph the actual individual plant on which the egg or caterpillar was found, showing any key features needed for the identifcation of the plant.

2. Photograph the egg or caterpillar.

3. Either leave the egg or caterpillar on the original plant, perhaps sleeving the plant it is on with netting, allowing the caterpillar

to develop in the wild, or remove the egg or caterpillar to your home and feed it only the same species of plant on which it was found.

4. Photograph later instars of the caterpillar.

5. Photograph the resulting chrysalis.

6. Photograph the adult after it emerges from the chrysalis.

7. If the egg or caterpillar was relocated for raising, release the adult back into the wild at the spot where you found it.

We would like to document each plant species used by each North American butterfy species, for each state or province. This is the 37th installment in this series!

In addition to appearing in American Butterfies, the results of this project will be posted to the NABA website. Please send any butterfy species/plant species/state or province trio that is not already posted to naba@naba. org.

by Jan Dauphin

A Straggler Daisy growing in the author’s yard. Nov. 6, 2007. This plant species is one of many plant species that are used as caterpillar food by Bordered Patches.

On Oct 6, 2007, I found a recently laid cluster of eggs beneath a Straggler Daisy (or Prostrate Lawnfower)(Calyptocarpus vialis) leaf, and I collected the leaf to rear the eggs (suspecting them to be Bordered Patches.

Over the course of a few days, the eggs darkened signifcantly and after about four days, the caterpillars hatched. I watched the

caterpillars develop and then, about 10 days after the caterpillars hatched placed them back on Straggler Daisies while keeping one of them to rear indoors.

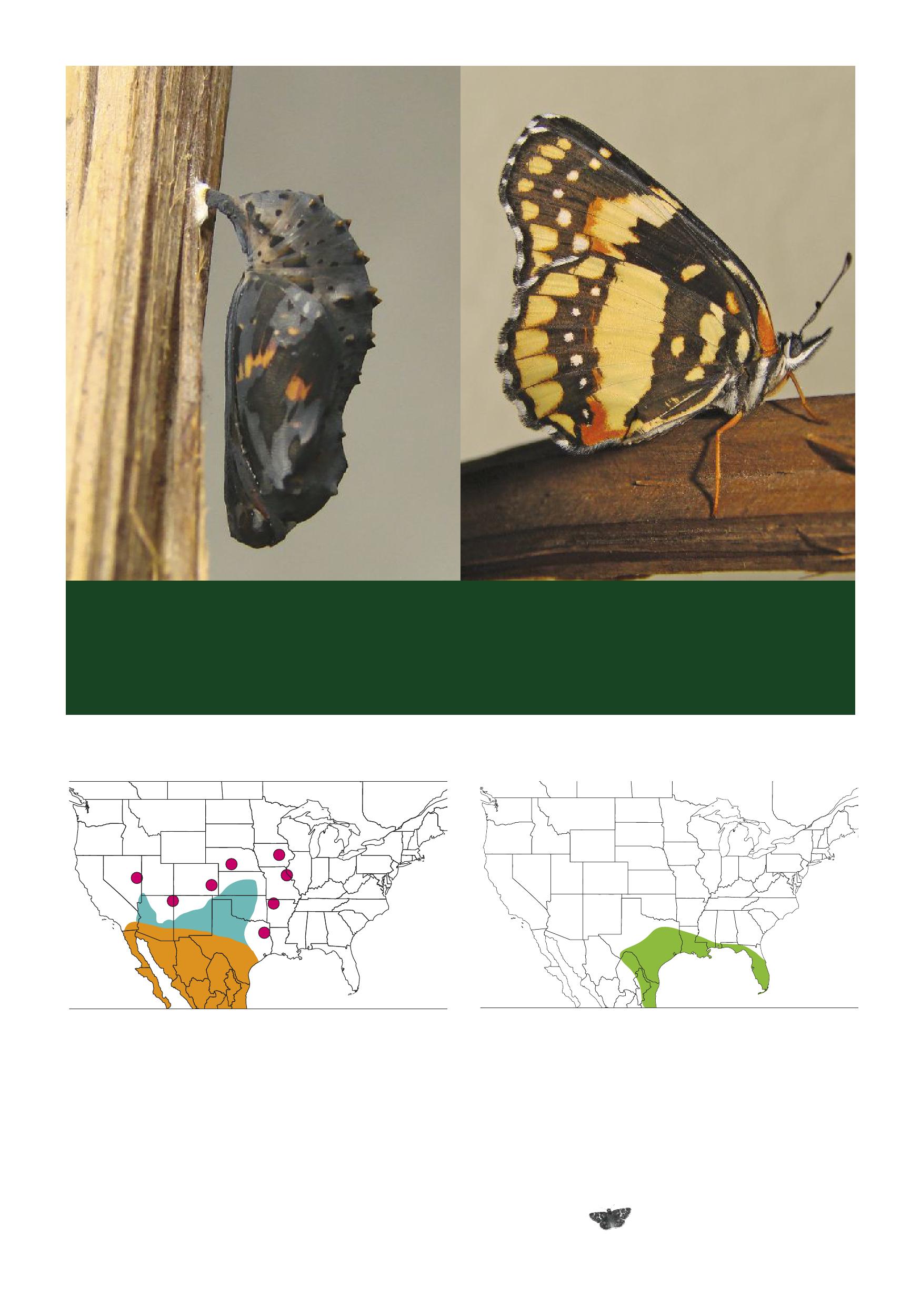

About three weeks after hatching, the caterpillar began to pupate. Six days later, the adult Bordered Patch emerged.

Opposite page

Top: Caviar anyone? Oct. 6, 2007. Mission, Hidalgo Co., TX.

Bottom: The caterpillars hatched from darkened eggs on Oct. 10.

This page

Top left: The young caterpillars on Oct. 12.

Top right: The caterpillars on Oct. 21.

Bottom: The star caterpillar on Oct. 23.

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Bordered Patches. Turquoise indicates one brood, orange, three or more broods. Cherry spots indicate that strays have occurred there. (drawing modifed from A Swift Guide to Butterfies of North America).

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Straggler Daisy, based upon county occurrence data from the Biota of North America Program. The species is native to south-central Texas and eastern Mexico and has been more widely introduced. This might be a useful plant for your garden if you live within the range shown.

Jane Hurwitz

Cerbone. What has your association with NABA been?

Hurwitz. All told, I have been the NABA jackof-all-trades. For more than 15 years I have been associated with NABA, starting with maintaining the membership database and administering the Butterfly Count Program, and then directing the Butterfly Garden and Habitat Program. Since 2011 I have been Editor of NABA’s Butterfly Gardener magazine, and last year my book Butterfly Gardening: The North American Butterfly Association Guide (Princeton University Press) came out.

Cerbone. There’s this idea among people of my generation (I’m 35, they call us the Elder Millennials) of being stewards of the land, and not exploiters of the land. I take my kids out to the woods for a homeschool co-op every week with a bunch of other homeschool kids in all types of weather, all year round. Schools and groups for children like this are becoming more popular but my own experiences of learning about gardening have shown me how divisive some practices and technologies can be (especially on the Internet). For example, I see that nobody agrees on the right way to mulch (arborist wood chips vs sheet mulching), how to provide effective amendments (is there a point to putting crushed egg shells into the soil when planting?), and other issues. Do you see this conflict in the butterfly gardening world? What guidance do you have for gardeners trying to navigate this?

Hurwitz. A lot of butterfly gardeners do not encourage mulching, rather they suggest

Interview by Michael Cerbone

that plants be allowed to fill in so densely that the soil is always covered by growing plant material during the warmer months or covered by fallen leaves and dead plant matter in the winter. When this strategy works, it cuts down tremendously on the amount of inputs needed for gardening and can improve both soil structure and butterfly habitat. A dense stand of plants may provide shelter for butterflies in addition to maximizing the number of nectar or caterpillar food plants growing in a given area. So, rather than see a conflict on the best way to mulch, I would suggest that there are always many different options for gardeners and it is simply a matter of choosing the best one for a particular situation — which may, in fact, include mulching. After Hurricane Sandy hit New Jersey, for example, I was a BIG proponent for a while of using arborist wood chips for mulch!

Cerbone. Can you describe your process for soliciting articles and other content for Butterfly Gardener magazine? From speaking with Jeff Glassberg about his own efforts for American Butterflies, it strikes me that seeking out writers is similar to looking for butterflies out in a meadow, except maybe more difficult!

Hurwitz. You are so right! In fact, sometimes it is like looking for very tiny butterflies in a very large meadow. But what makes the search for magazine content fun is that I get to ask people what they are doing in their gardening lives, what makes gardening tick for them. I myself have been gardening for nearly 50 years and I am still learning new

things all the time. There are an unlimited number of topics in gardening, whether you garden specifically for butterflies or not, so gardening is a type of lifelong learning, you just keep learning and reading more, in fact reading gardening books has also been a lifelong hobby. I still treasure some gardening books that were given to me as a child.

The material that people send in to the magazine emerges from what they are doing in their current gardening life, and while the topic, butterfly gardening, is the same, each person’s experience is unique because each person interacts with their gardening environment differently, they have access to different resources, a different climate — the variables are endless. What draws me initially is the interactions between insects and plants, but what holds my attention is how people respond to those interactions.

Cerbone. Can you tell us about any resources (books, websites, etc.) that you value highly for their gardening lore that people are less likely to know about?

Hurwitz. I don’t have any specific gardening book suggestions because I find all gardening books interesting; who is your favorite child? But I do have some favorite butterfly

books and websites that I think are worth mentioning. Since we’re talking about NABA, one website that I like but that is not well publicized is NABA’s webutterfly.org. I love that it uses data from the Butterfly Count Program and it is also a great general resource. I suggest it to beginning butterfliers as one of the online resources that has accurately labeled butterfly photos. A book that I reference often that is less well known than it should be is Butterflies of the East Coast: An Observer’s Guide by Rich Cech and Guy Tudor. When I want to know a caterpillar food plant for a butterfly in my area, I check Butterflies of the East Coast and then always end up reading about far more than the food plants! Unfortunately the book is out of print but there are still used copies available. I have a few other favorite butterfly books that do not correspond to my region, but I’ve learned much from them nonetheless: Butterflies of Alabama: Glimpses into Their Lives by Paulette Haywood Ogard and Sara Cunningham Bright provides great insight into butterfly life styles, and A Photographic Field Guide to the Butterflies in the Kansas City Region by Betsy Betros has always pulled me in. Something about the way that she describes the butterflies and provides information on similar species makes me keep her book on my shelf.

Cerbone. For people out there interested in doing garden writing or writing about butterflies and butterflying (like myself), do you have any advice on how to get started?

Hurwitz. So glad you asked! Consider sending an article to Butterfly Gardener magazine or American Butterflies. There are writer’s guidelines for Butterfly Gardener on the NABA website under the “publications” tab. Writing can be demanding and take a surprisingly long time. The most useful advice I can pass along is the same advice that was given to me a long time ago: Find a topic that you love and sit down. Sit for a very long time, then sit a bit longer. And make sure that you have some words on the page before you get up!

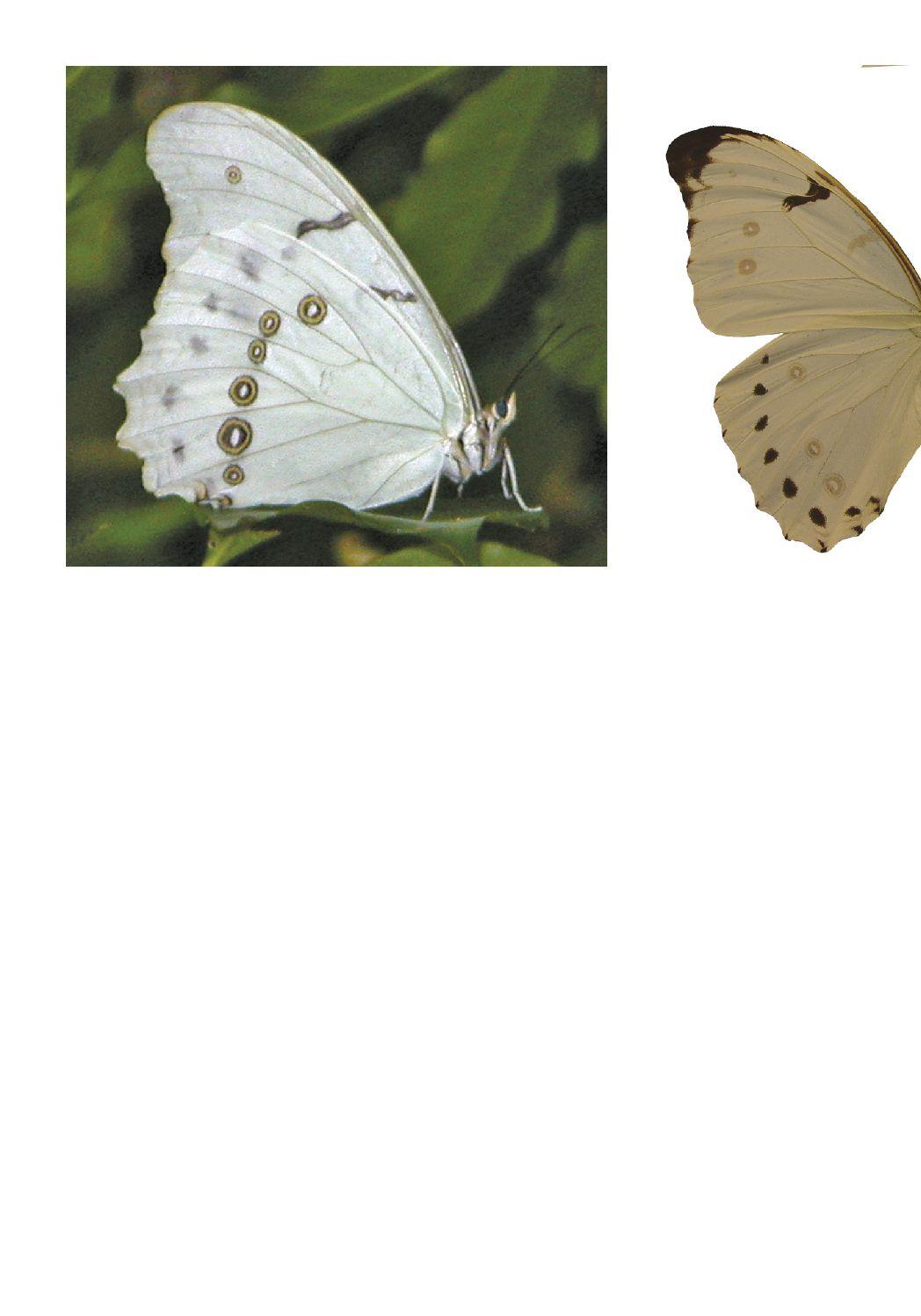

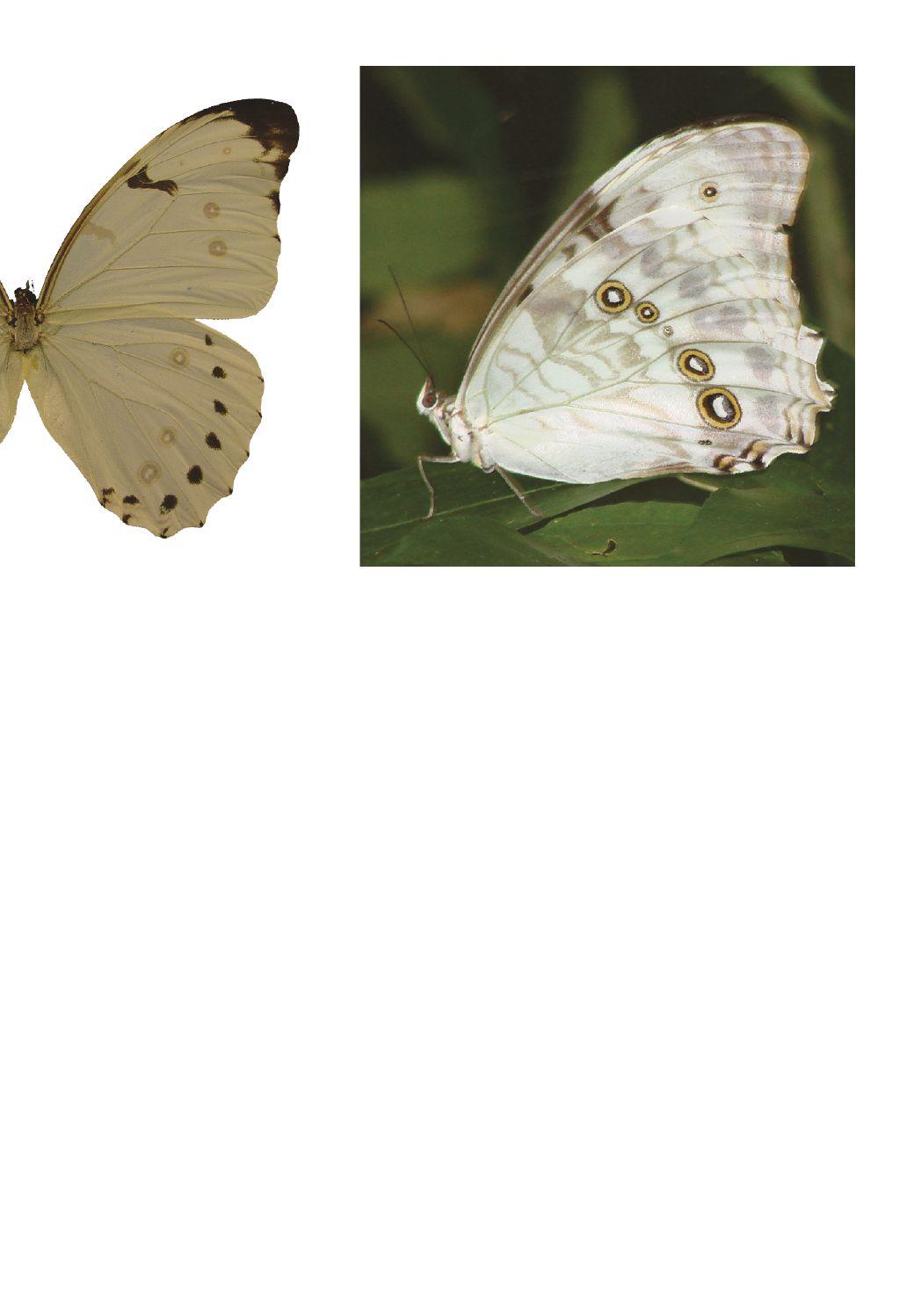

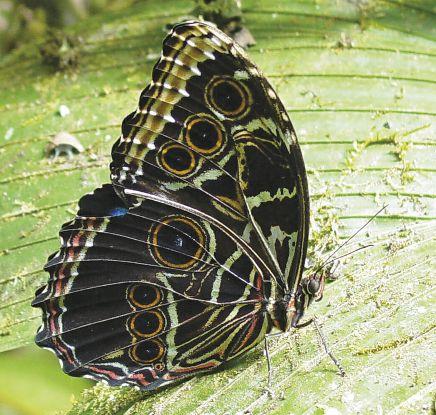

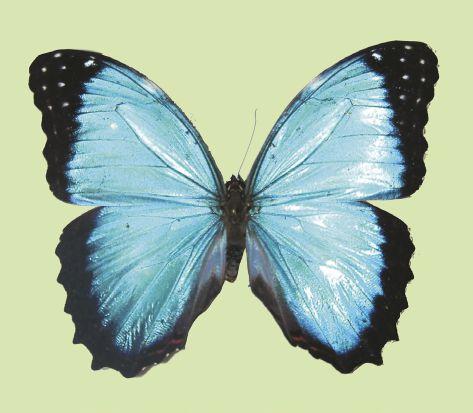

Butterflies in the genus Morpho are among the largest and most beautiful species in the Western Hemisphere. Many, but not all, are stunning iridescent blue on the upper sides of the wings, whereas the undersides of the wings are often deep brown with an array of eyespots. This pattern causes them to flash and dazzle while flying but seemingly disappear when they alight and fold their wings over the back, concealing the bright blue and exposing only the somber undersides.

This behavior, while perhaps a specific adaptation to the sunlit canopy

of the rain forest, is not so different from that of our various commas, such as Eastern Comma , which expose bright, flashing colors in flight only to blend in quickly upon landing. So, too, with two of our brightest blue hairstreaks, White-M Hairstreak and Great Purple Hairstreak (which is blue) which are tropical species that moved north. Morphos occur regularly only from Mexico southwards, although there is one record of White Morpho (Morpho polyphemus) from Arizona and also tantalizing stories of glimpses of big flashing blue butterflies in Texas along

Below: The underside of Morpho amathonte, Clouded Morpho. Sept. 12, 2008. Canopy Tower, Panama.

Opposite page: The upperside of Morpho amathonte, Clouded Morpho. 99-SRNP-5893. Costa Rica.

the Mexican border. There are close to thirty full species in the genus and scores of named subspecies, although the validity of some named taxa is controversial and the taxonomy is always in a state of flux.

Just as with the last article I wrote about cattlehearts, I have never seen a morpho in the wild. Friends who know of my interest in butterflies and go on eco-tours to Costa Rica or elsewhere in Latin America are always telling me what a thrill it is to see them and it must be, but I just never get around to going to anyplace with morphos.

Morphos are quintessentially Neotropical butterflies in the Brushfooted butterfly family. Within the Brushfoots, they are most closely related to the satyrs, (and placed by some workers in the subfamily Satyrinae), a relationship that is not so obvious until you think about their brown undersides with a row of eyespots. And in the Neotropics, there are satyrs with iridescent blue colors on the upper sides of the wings such as Mexican BlueSatyr, Blue-topped Blue-Satyr and Blue Vented Blue-Satyr. In fact, even in the United States, freshly emerged satyrs,

Above: Adam and Eve, a print by Salvatore Dali that makes effective use of Morpho cypris. The individual depicted here appears to be Morpho cypris aphrodite, which apparently means “The shapely one, lady of Cyprus, Aphrodite. Did Dali know this and intentionally place this butterfy on Adam while placing a butterfy whose English name is Black Pansy on Eve? Let’s guess yes!

such as Common Wood-Nymph have an iridescent green or purplish sheen that can be seen occasionally when they open their wings and the sunlight hits them just right. In my view, if you think of morphos as being giant blue satyrs, you won’t be far wrong.

As for the origin of the generic name, “morph” means shape or form in Greek and I always assumed that morphos got their name because the iridescent scales on their wings caused them to change

their color or form as they flew, a kind of metamorphosis or “change in form.” But that, apparently, is not the origin of the name, at least not directly.

Morpho is another epithet for the Greek goddess of beauty, Aphrodite, and means “the Shapely One.” The name was created by Fabricius in 1807, but morphos were known to European naturalists long before the name was coined. The painter and naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) traveled

Above: Morpho helenor, Common Morpho, is widespread throughout the Neotropics, but details of its wing pattern vary geographically. June 8, 2008. Atoyac, Veracruz, Mexico.

to what was then Dutch Surinam (Suriname today) in 1699 and not only created images of the adults of morphos, she also observed and illustrated the life histories of a number of species.

Linnaeus named two species himself in 1758 (telemachus and achilles), although he placed both in the genus Papilio, where he placed all butterfly species. Telemachus and Achilles were central figures in Homer’s Iliad, perhaps the literary source that supplied Linnaeus with more butterfly names than any other (although readers will have to wait for me to retire before I count them up).

Neither Morpho achilles nor Morpho telemachus occurs in Mexico or Central America and it is the six species that occur there and which appear in the Swift Guide to the Butterflies of Mexico and Central America by Jeffrey Glassberg that I will discuss in this article

The six morphos that occur in Mexico and Central America are Common Morpho (Morpho helenor), Cobweb Morpho (M deidamia), Shorttailed Morpho (M theseus), Clouded Morpho (M amathonte), White-banded Morpho (M cypris) and White Morpho (M polyphemus). All six of these names are based in Greek mythology and all

Above: The upperside on a Morpho helenor, Common Morpho. Oct. 31, 2014. Valle de Anton, Panama.

of them relate in one way or another to Aphrodite and the Trojan War she caused.

You may recall that the root cause of the mythological Trojan War was the abduction of Helen by Paris (whether there was an actual Trojan war is only a matter of conjecture, even if one accepts that there was a Troy based on the archeological evidence of Heinrich Schliemann’s digs at Hisarlik in Turkey). Although Helen is often called “Helen of Troy” she was Helen of Greece before she was abducted. She was abducted because Aphrodite promised the mortal Paris (a Trojan prince) the

most beautiful woman in the world as his prize if he chose Aphrodite as the fairest among the three goddesses Hera, Athena and she.

The contest between these three goddesses as to whom was the fairest was precipitated by Eris, the goddess of discord, who was angry at not being invited to a celebration (who wants discord at a celebration, after all). So she crashed the party bearing the gift of a golden apple inscribed “For the Fairest.”

Originally, Zeus was supposed to judge among Hera, Athena and Aphrodite, but Hera was his wife and

Morpho polyphemus, White Morpho. Jan. 8, 2005. Monte Carlo, near Santa Maria, Oaxaca, Mexico

Athena his daughter (she sprang fullborn from his brow, remember?) so he passed the task to Paris who had a reputation for fairness, although it was apparently undeserved as he let himself be bribed.

Once Helen was carried off to Troy, the Trojan War ensued as described in Homer’s Iliad. The journey back to Greece for Odysseus and some of the other participants in the war is described in The Odyssey. These two Homeric works contain hundreds of mortal and immortal characters whose names have been applied to butterflies and other animals from Linnaeus onwards.

White-banded Morpho (Morpho cypris), named by Westwood in 1851,

Morpho polyphemus, White Morpho. Mexico

takes its scientific name from another epithet for Aphrodite because the ancient people of the island of Cyprus claimed that Aphrodite was born there. “Cypris” means “‘Lady of Cyprus” so Morpho cypris could be translated as “The Shapely One, Lady of Cyprus.” But wait, there is a subspecies of this Morpho in Nicaragua and Honduras named Morpho cypris aphrodite which must mean “The Shapely One, Lady of Cyprus, Aphrodite.” This Morpho, with its opalescent markings against a shimmering light blue background is arguably the most beautiful butterfly in the world, but judging the most beautiful will only lead to discord, as the story of Paris teaches. Clouded Morpho (Morpho

Morpho. Museum specimen. Veracruz, Morpho polyphemus, White Morpho. July 31, 2009. Ruiz Cortines, Veracruz, Mexico

amathonte), named by Deyrolle in 1860, also has a name related to Aphrodite. Amathus was an ancient city in Cyprus and maintained a cult sanctuary of Aphrodite in her incarnation as Aphrodite Amathusia.

Cobweb Morpho (Morpho deidamia) is named for yet another symbol of feminine beauty, as Deidamia of Scyros was the young bride of Achilles, whom he left behind (pregnant and none too happy) to join the Trojan War expedition.

Short-tailed Morpho (Morpho theseus), was also named by Deyrolle in 1860 for the mythic king of Athens who slew the Cretan Minotaur in his labyrinth. Theseus, too, has a connection with the goddess of beauty,

as the Greek historian Pausanias wrote that Theseus founded the sanctuary to Aphrodite on the Acropolis in her role as “Aphrodite Pandemos” or “Aphrodite of all the People,” a name fitting for the Athenian democracy.

White Morpho (Morpho polyphemus) and Common Morpho (Morpho helenor) were named for masculine characters who also had a connection to the Iliad or Odyssey.

Polyphemus was the name of the Cyclops who captured Odysseus and his men on the island of Sicily when they entered his cave in search of food. After killing and eating four of the Greek warriors, he was made drunk and then blinded by Odysseus and then tricked into allowing the Greeks to escape the

cave. Polyphemus also lent his name to Polyphemus Moth, which has one huge eyespot on each hind wing reminiscent of a Cyclops. White Morpho has a row of eyespots on its underside wings but so do most Morphos and I don’t know if the name polyphemus was meant to refer to these markings or not when the name was bestowed by Westwood in 1850.

Common Morpho (Morpho helenor), named by Cramer in 1775, bears the name of yet another warrior in the Trojan conflict. Helenor was the illegitimate son of the King of Lycia and a slave named Lycimnia. He went and fought in the Trojan war on the side of the Trojans but did nothing to distinguish himself. Only when he follows Aeneas to Italy and dies in battle there flinging himself on the Latin enemy does he do anything notable in the eyes of the Roman poet Virgil. Recall that The Aeneid of Virgil sets out the myth that the Romans are descended

from the Trojans through the Trojan prince Aeneas who conquers the Latins. Common Morpho is found throughout the New World tropics and I have a list in front of me that sets out the names of 47 subspecies in addition to the nominate taxon. My guess, without knowing anything more about it, is that is an excessive number of subspecies and is the sort of splitting that often causes butterfly taxonomy to be viewed with skepticism by workers in other groups.

Now is perhaps a good time to say that whereas I see relationships among these names, the genius of the system that Linnaeus invented is its arbitrariness. As long as each species has a unique name, its name doesn’t have to mean anything or refer to anything. The names are simply symbols that stand for the species. Some names are descriptive, like Two-tailed Swallowtail (Papilio

Morpho deidamia, Cobweb Morpho. Clearly, great beauty leads to spinning webs of intrigue. Left: Jan. 16, 2003. Cana, Panama. Right: Morpho deidamia, Cobweb Morpho. SRNP 21505, Costa Rica.

multicaudatus) which can be translated as the “Multiple-tailed Butterfly) but many names are not descriptive and deliberately so.

Prior to the Linnaean system, species were known in scientific circles by long descriptions in Latin such as “The butterfly with two-tails on each hind wing with multiple black stripes on each fore wing against a yellow ground color” etc. It was the insight that Linnaeus had that if the name stopped after two words, the first word being a group name and the second name being unique to each species in that group, it was sufficient, so long as no other species had both the same first and last name.

Think how confusing human names are in comparison with all the John Smiths and James Jacksons, with some closely related to each other and some not. Our names are so unworkable that the government has to issue us unique nine-digit numbers to keep us all straight. Incidentally, our social security numbers in the format 123-12-1234 are a sort of trinomial nomenclature, or at least they were when I was born. The first three digits stand for the state I was born in, the second two digits are the batch number for the numbers assigned during a certain period and the last four digits are sequential within that batch. Using that system, more than 400 million unique numbers have been assigned to date.

The system that Linnaeus devised, still in use today, supplanted an unworkably complex system and, in its relative simplicity, is not so different in logic and format from systems devised by other cultures. As pointed out in Principles of Animal Taxonomy (Columbia Univer-

sity Press, 1960) by the mammalogist George Gaylord Simpson, indigenous South American languages had a word for armadillo (tatu) and the various species of armadillo were known as tatu para, tatu guasa, etc. which neatly tracks the logic inherent in binomial nomenclature.

Simpson also points out that most of the vernacular names in field guides are not truly vernacular at all, but are created by naturalist authors to track the same system the scientific names follow. “Butterfly” is a vernacular name in the sense that most people on seeing a butterfly and asked what they are looking at would respond “a butterfly.” The subset of people who would respond “an Eastern Tiger Swallowtail” is probably not that much broader than the subset that knows the scientific name is Papilio glaucus

With many insects, this is even more pronounced, as very few people understand that the vernacular name “ladybug” is not one kind of beetle (assuming they know ladybugs are, in fact, beetles) but that ladybugs are a diverse family of beetles (the Coccinelidae) with almost 500 species in the United States alone. English names for ladybug species such as Seven-spotted Ladybug or Convergent Ladybug are often simply translations of the scientific names. And that brings me back to morphos because, almost invariably, when my birder friends return from the neotropics and tell me they saw morphos, it is useless to ask them what species of morpho they saw.

by Michael Reese

A cooler fall in the eastern part of the United States and an early dose of freezing weather put an early end to the butterfy season. Late season sightings consist of a November 1 list from Michael Drake of six species including a Pearl Crescent reported from the Morris Arboretum, Philadelphia Co., PA; a November 3 report from Mike Reese from Forest Beach Migratory Preserve, Ozaukee Co., WI of an Orange Sulphur nectaring on dandelions in sun and 45-degree temperatures; a November 4 report from Andrew Block of three species including a Monarch at 192 Macy Rd., Briarcliff Manor, Westchester Co., NY; and a November 7 submission from Rich Kelly, Al Lindberg, and Lois Lindberg of three Red Admirals and eight Monarchs at Jones Beach State Park, Nassau Co., NY. Other late fall sightings included a November 18 sighting of a Monarch by Denis C. Quinn on Fowler’s Beach Rd., Sussex Co., DE; a November 19 report of an Orange Sulphur and an Eastern Comma in northwest Carroll Co., MD by Jim Wilkinson; fve Eastern Commas seen by Marcus Gray and family at Powhatan WMA, Powhatan Co., VA on November 21; a report from Kathy Beza Richardson on November 25 of four species including three Sleepy Oranges in Cumberland Marsh NAP, New Kent Co., VA; and a December 2 report by Linda Romine from Meldahl Lock and Dam, Chilo Lock #34 Park, OH of four Orange Sulphurs, a Question Mark and two Eastern Commas. Allen Belden started off the new year right with an Eastern Comma on January 1 in an urban garden in Richmond, VA with overcast skies and temperatures in the mid 60s; and Bart Jones observed a Question Mark on January 27 at Memphis Botanic Garden, TN.

Some butterfiers in the Lower Rio Grande Valley had an ID disagreement, luckily, they were able to patch things up! The species shown here are some of the least seen resident U.S. butterfies.

Left We think that this is some type of patch, but can we be defnite? Nov. 3, 2018. National Butterfy Center, Hidalgo Co., TX

Right A Banded Patch spent a number of days at Falcon State Park, Starr Co., TX, providing a lifer for many butterfiers. This photo was taken on Nov. 7, 2018.

The upperside of the same individual Banded Patch.

Florida butterfy sightings included a report of 26 species, including ‘Florida’ Dusted Skipper, at Bull Creek WMA, Osceola Co., FL on November 2, by Ed Perry IV; 15 species and the park’s second-ever Malachite, submitted on November 15 by Ron Smith in Fort De Soto Park, FL; a November 15 report by Hans Johnson of fve species including two Atalas at Naples Botanical Garden; and a Nov. 18 sighting of Martial Scrub-Hairstreak in Broward Co. A very late-fying Delaware Skipper was photographed at Paleo Hammock, St. Lucie Co., by James Monroe. A January 1 sighting of 13 species including three endangered Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreaks by Walter Wallenstein at Navy Wells Pineland Preserve, Homestead. Additional Florida reports included a January 22 sighting by Edward Perry IV of three species including a male and female Julia Heliconian at McLarty State Treasure Museum, part of Sebastian Inlet State Park; and a January 26 list by Amelia Grimm, Leigh Williams, and Mark Whiteside of 13 species including a rare Amethyst Hairstreak in Fort Zachary Taylor Historic State Park, Key West, Monroe Co.

Western butterfies of note include a November 2 report from Allen Belden of eight Chiricahua Whites in the Mt. Lemon summit area, Pima Co., AZ; a November 2 sighting of four species including California Tortoiseshell and Mourning Cloak, both late dates at this location, by David H. Bartholomew at Rancho San Antonio Open Space Preserve, Santa Clara Co., CA; and a November 9 report from Barbara Peck of 11 Gulf Fritillaries despite 30 degree temperatures in the morning, in her backyard in Anderson, Shasta Co., CA.

January reports included a January 6 submission from Ken Wilson in Escondido, CA, his frst of the year butterfy a Cloudless Sulphur; a January 19 sighting from John Heyse in Crockett Hills Park, Contra Costa Co., CA of two Mourning Cloaks, his frst butterfies of the year; a report on January 22 of fve species including two Large Orange Sulphurs by Brett Badeaux in Craig Regional

C’mon, it was winter — what could possibly be fying?

Top left

Bordered Patches on the U.S-Mexican border at the National Butterfy Center, Hidalgo Co., TX on Nov. 1, 2018.

Top right

Mexican Bluewings are the iconic butterfy of the National Butterfy Center. However, this one was photographed at Progreso, Hidalgo Co., TX on Nov. 1, 2018.

Middle right

This Soldier was patrolling in Progreso, Hidalgo Co., TX on Nov. 1, 2018 (note the proximity to, and possible interdiction of, the Mexican Bluewing).

Middle left

Chestnut Crescents are rare immigrants to the United States. Very similar Brown Crescents have never made it across the border. McAllen Nature Center, Hidalgo Co., TX. Nov. 7, 2018.

Bottom right

In the winter, Queens are usually the most common butterfy at the National Butterfy Center. National Butterfy Center, Hidalgo Co., TX. Nov. 24, 2018.

Bottom left

Yes Virginia, there is a Florida and, even in the winter, it brings butterfy gifts. This Martial Scrub-Hairstreak provided an uncommon view of its upperside. North of Griffn Rd., Broward Co., FL. Nov. 18, 2018.

Park, Orange Co., CA; and a January 24 report from David H. Bartholomew at Rancho San Antonio Open Space Preserve 12, Santa Clara Co., CA of a Mourning Cloak and three California Tortoiseshells.

In November, Texas butterfy reports often have some highlight sightings. Some submissions from this year include a November 1 sighting list from Daniel Jones from his yard in Progreso Lakes, Hidalgo Co., of 44 species including a Mexican Bluewing and a Ruddy Daggerwing; a November 2 sighting by Mark and Holly Salvato of 23 species including three False Duskywings in Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Refugio Co.; and Sandy-Crystal Vaughn observed eight species including her lifer Viceroy at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Refugio Co. on November 3. Linda Cooper kept us informed about the butterfies before, during, and after the Texas Butterfy Festival. Some of her highlights include a November 2 trip to Roma, Salineno, Falcon Heights, and Falcon State Park, Starr Co., with Mike Richard where they saw 49 species including huge numbers of Large Orange Sulphurs, American Snouts, and Queens; Linda Cooper reported November 3 sightings from the National Butterfy Center and McAllen Nature Center, Hidalgo Co., of 51 species including a rare Hermit Skipper at each location; Also on Nov. 3, many observers were treated to a Defnite Patch at the National Butterfy Center, Hidalgo Co., the frst report of this scarce species from the National Butterfy Center. A November 6 trip with Linda Cooper, Ken Wilson and Luciano Guerra with 66 species including Guava Skipper and Hermit Skipper at the King Family Compound, McAllen Nature Center, and the National Butterfy Center. A Chestnut Crescent, a very rare stray to the U.S., was at the McAllen Nature Center, Hidalgo Co.; First seen on November 7 by Robert Gilson and Chris Talkington, a Banded Patch was present at Falcon SP, Starr Co., TX for at lease a couple of days. Linda Cooper had a November 14 list of 55 species including

A beautiful, freshly emerged Delaware Skipper was found at Paleo Hammock, St. Lucie Co., FL on Dec. 2. This is a late date for this species. Maybe something is happening with the climate?

Isabella’s Heliconians are rare strays to the United States. This individual was nectaring at the National Butterfy on Jan. 12, 2019, demonstrating once again that any time of the year is a good time to visit the National Butterfy Center.

a Red Rim and a Four-spotted Sailor at the National Butterfy Center, Hidalgo Co.; and, on a November 25 trip with 12 others to Falcon State Park and Falcon Heights, Starr Co., she reported 50 species including a Vicroy’s Ministreak, Mexican Fritillary, and Coyote Cloudywing. Karl and Dorothy Legler submitted several reports from January to let us know that there are still butterfies to be seen. On January 4 they saw 20 species at the Valley Nature Center, Weslaco, Hidalgo Co., including Red-bordered Metalmark and Sickle-winged Skipper. On January 12 at the National Butterfy Center, Mission, Hidalgo Co., they totaled 41 species, including a rare Isabella Heliconian; and on January 28 at Sable Palm Sanctuary, Cameron Co., they saw17 species including six Blue Metalmarks.

Whether you see an unusual butterfly, an early or late sighting of a common species, or have a complete list of the species you have seen, we would appreciate hearing from you. Please send your butterfly sightings to sightings@naba.org. Those who record your sightings to the Butterflies I’ve Seen website can just click on “email trip” and send it to the address given above. Your sightings will go into the larger database and will also be available for others to see on the Recent Sightings web page.

Opposite page

Top

Hermit Skippers had a small boomlet in the Lower Rio Grande Valley last fall. This forward looking individual was at the McAllen Nature Center, Hidalgo Co., TX, on Nov. 3, 2018.

Bottom left

This latish ‘Florida’ Dusted Skipper was photographed at the Bull Creek WMA, Osceola Co., FL on Nov. 2, 2018.

Bottom right

Jane Vicroy Scott is no longer with us, but Vicroy’s Ministreak still fies! Rarely seen in the U.S., this one was at Falcon Heights, Starr Co., TX, on Nov. 25, 2018.

page, top

A male Four-spotted Sailor sailed into the National Butterfy Center on Nov. 14. The crew was very excited.

Jesse Babonis works as a veterinary technician in northeastern Pennsylvania. She’s been interested in insects for as long as I she can remember, and the saturniids are of particular interest to her. Jesse attended classes at the University of Maine in Orono and Bloomsberg University in Bloomsberg, PA.

Mike Cerbone is NABA’s administrator for the Butterfy Garden Habitat Program and Social Media Coordinator, currently helping to edit the 2018 Butterfy Count. He has a bachelor’s degree in English from Rutgers University, and currently lives in Basking Ridge, New Jersey with his wife, Beth, and young son, Callum. He’s working on renovating a historic 1790’s East Jersey Cottage here in Bernards Township, and has big plans for a woodland garden in the property’s backyard, along with plenty of host and nectar plants for butterfies. Michael was born and raised in the Garden State, and returns to it after spending almost a decade living in Oakland, CA and Pittsburgh, PA.

Jan Dauphin’s passion for the past 20 years has been butterfy watching. Her photos have appeared in over 30 books, numerous magazines, and thousands of newspapers, worldwide. After retiring from the Houston area, she moved to Mission, TX twelve years ago, strictly for the butterfies. Her tiny Mission yard was landscaped in local native

plants and has had 152 documented species of butterfies, probably the highest yard list in the U.S. Jan is very much involved in South Texas’ Lower Rio Grande Valley’s conservation organizations. Her award-winning web page, TheDauphins.net, covers the fora and fauna of “the Valley”.

Steve Glynn is an enthusiastic amateur naturalist who enjoys butterfying and traveling the U.S. in search of butterfies, birds and dragonfies. He and his family are from South Jersey, but after 20 years of work in digital equipment and medical imaging manufacturing, plus a 15-year tenure in industrial sales representation, Steve will be retiring in 2020, with his wife Lisa. They plan to travel, hike and chase butterfies and waterfalls across the U.S. Steve enjoys nature photography and sharing stories and images of his butterfy discoveries, while pursuing writing about nature and travel, participating in and leading nature walks, and giving presentations on his butterfying activities.

Mike Reese updates the NABA Recent Sightings web pages. He enjoys photographing wild fowers, birds, dragonfies, and, of course, butterfies. He is an educator in Wautoma, Wisconsin and has been recording and documenting the butterfies that are found there for over 15 years. He also maintains a website on the Butterfies of Wisconsin.

Harry Zirlin’s fascination with butterfies and other insects dates to his early childhood. He travels extensively in the United States, studying and photographing butterfies. He supports this passion by working as an attorney in the environmental area at the New York law frm of Debevoise & Plimpton.

I hope they smash every butterfy on the boarder [sic] as they BUILD THE WALL Todd Schafer67@gmail.com

Dear Mr. Schafer, thank you for sharing your sensitive side with us. [Ed.] [this is one of the few such emails and telephone messages, of the many, many received at NABA HQ and at the National Butterfy Center, that we could share with a family audience).

This year, NABA president Jeffrey Glassberg tries to photograph the twentyone U.S. resident species that he hasn’t yet photographed in the United States (see article in last issue of American Butterfies. You can follow his episodic progress at https:// butterfies.naba.org/. First up will be a trip to Missouri in late April, searching for Ozark Swallowtail, a species for which there has been no documented occurrence in 32 years. After this, the plan is to visit Oklahoma in May, looking for Outis Skipper, and then to travel to Alaska in June, hoping to photograph Early Arctic and Taiga Alpine.

You can encourage his efforts and support NABA at the same time by pledging a taxdeductible donation to NABA — it can be $10 or $1000, or whatever else you want — for each of the twenty-one species he is able to see and photograph over the course of the next three or four years (he’d be especially pleased if you designate your donations for the Jane Vicroy Scott Memorial Fund). It may be a grueling marathon — the time needed in Hawaii seems like it will be especially tough. Simply write (NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960) or email (naba@ naba.org) to let us know about your pledged donations. Thanks for your support!

(continued from inside front cover)

The best guide to butterfy gardening — NABA’s own, of course! — authored by Jane Hurwitz, editor of NABA’s Butterfy Gardener, has been published by Princeton University Press. Keep an eye out for it.

We’d like to ask those NABA members who have planned estates, to consider including NABA and the National Butterfy Center in their plans. This will allow you to continue to help butterfies and conservation.

Please smile if you use Amazon to purchase anything! If you do, Amazon will donate a portion of the purchase price, at no cost to you, to NABA. Simply go to smile.amazon.com and follow instructions, choosing North American Butterfy Association as your charity.

You can now follow NABA activities on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest (and also by talking with actual people!).

Those of you who generously contribute donations to NABA and work at a large corporation may be able to double your contribution. Many corporations have matching gift programs. Check with your human resources or public relations dept. to see if your company have such a program.

Correction: The photo of a Yellow Angled-Sulphur on page 41 of the American Butterfies Winter 2018 issue was labeled as having been taken in Carr Canyon, AZ. It was actually taken in Ash Canyon, Cochise Co., AZ.