Butterflies American

Volume 26: Number 1 Spring 2018

Fritillary ID

Taxonomists: Flashers

Volume 26: Number 1 Spring 2018

Fritillary ID

Taxonomists: Flashers

NABA’s Survey of Frosted Elfins

NABA’s survey of Frosted Elfins in East Texas, underwritten by a Conservation License Plate grant from Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept. is underway!

Citizen science volunteers have already located a number of colonies of the elusive elfins and wild indigos, their only caterpillar foodplants. The project will continue into April. Later this year, we plan on running an article in this magazine, letting everyone know the results of the survey.

NABA is offering free trial memberships to people who have not previously been NABA members, if they help NABA monitor butterflies by entering data into the Recent Sightings page and/or participate in the NABA Butterfly Count program. The free, trial membership includes access to digital versions of NABA publications as well as access to NABAChat and other NABA programs. So, invite your friends, family and neighbors to participate in Recent Sightings and/or the Counts, helping to monitor and conserve butterflies throughout North America — they will be rewarded with a free, trial membership.

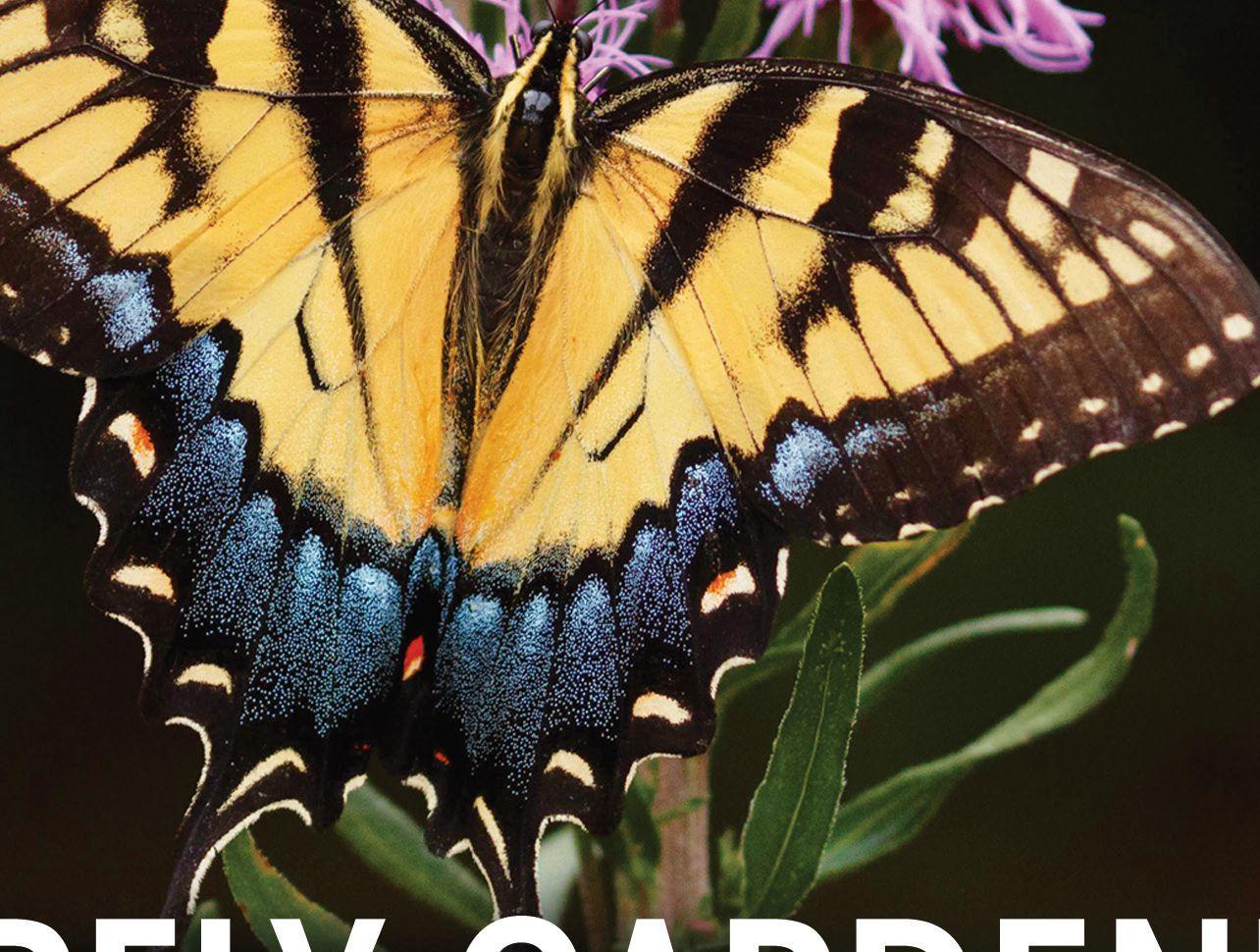

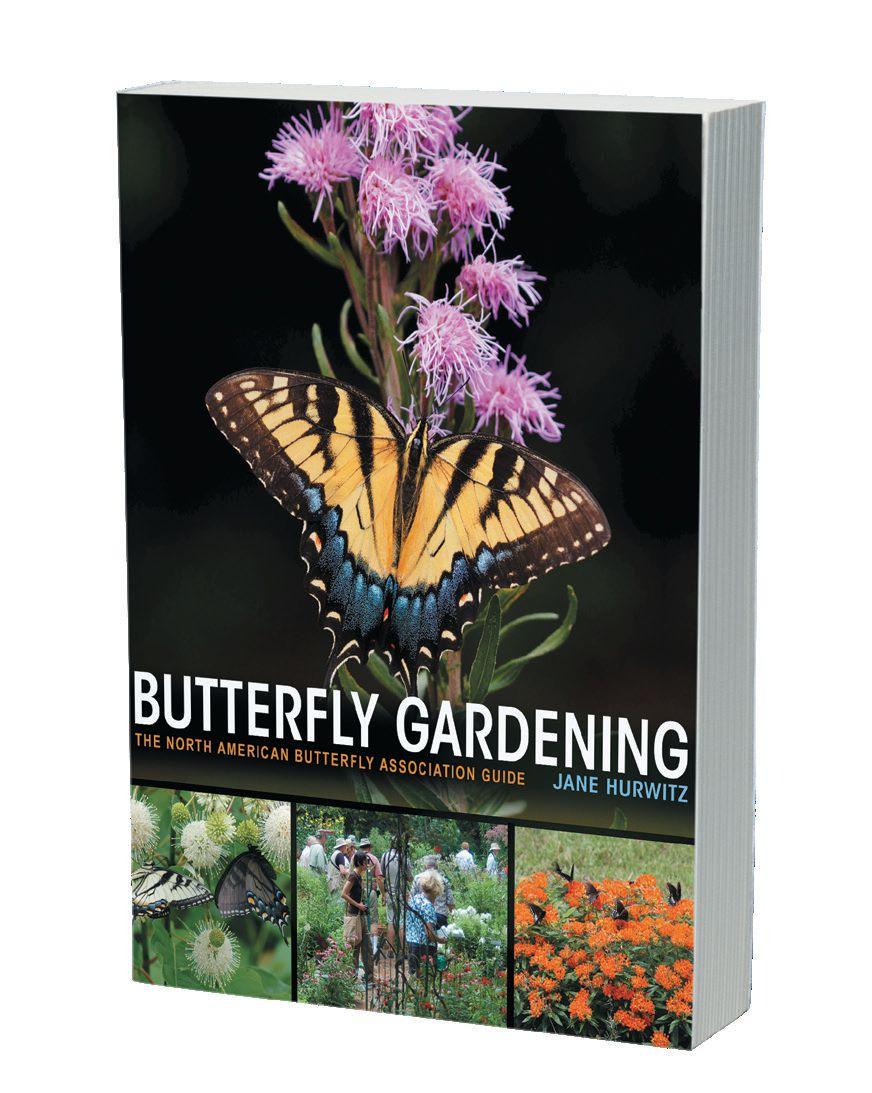

NABA’s Butterfly Gardening Guide

Butterfly Gardening: The North American Butterfly Association Guide, authored by Jane Hurwitz, editor of NABA’s Butterfly Gardener, has just been published by Princeton University Press — see ad on page 41. The best guide to butterfly gardening is available to NABA members at a 30% discount by going to https://press.princeton.edu/titles/11290.html and using the code NABA 18 (once the book is in the shopping cart, a box for “discount Code” appears. Members can also call 800-343-4499 and follow the prompt for customer service who will accept the discount code — good until the end of May, 2018.

New Virginia Chapter

We are happy to report that a new NABA chapter has formed in the Richmond, Virginia area. Contact Lauren Adelman, president, at heyla2016@gmail. com for more details.

NABA Members Meeting: Save the Date!

It’s official! The thirteenth NABA Biennial Members

Meeting will be held September 16-19, 2018 in Tallahassee, Florida. Don’t miss this great opportunity to see butterflies you may never have seen before, including Yehl Skipper, Berry’s Skipper and Dotted Skipper, along with thousands of individual butterflies, including sweeps of seven species of swallowtails. Better yet, you’ll be able to connect with ardent butterfliers from throughout the country. NABA meetings are always fun!

Planning

We’d like to ask those NABA members who have planned estates, to consider including NABA and the National Butterfly Center in their plans. This will allow you to continue to help butterflies and conservation.

Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreak

NABA has begun a project to save endangered Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreaks. So far as is known, Grannybush (pineland croton) is the only plant species eaten by Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreak caterpillars. Pineland croton is restricted to pine rockland habitat, which has largely been, and continues to be, destroyed. Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreak also appears to be restricted to pine rockland habitat, but that may be because that is the only place that it’s caterpillar foodplant is found.

NABA is trying to replicate the success that South Florida gardeners inadvertently had in stabilizing the population of Atalas and increasing their range. Atalas were thought to possibly be extinct, but then, about 25 years ago, cycads became popular garden plants in South Florida. Even though the cycads planted in land owners gardens were almost always non-native species, Atalas still were able to use these plants as caterpillar foodplants.

We are hoping that Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreaks will respond in a similar way, using pineland crotons even when they are growing in suburban yards. To that end, we have initially grown 1000 pineland crotons and will soon be working with Fairchild Gardens, the Miami Zoo and Miami-Dade County to distribute these plants to home owners who live near the few existing populations of Bartram’s ScrubHairstreaks. If, as we hope, these plants are found

Continued on inside back cover

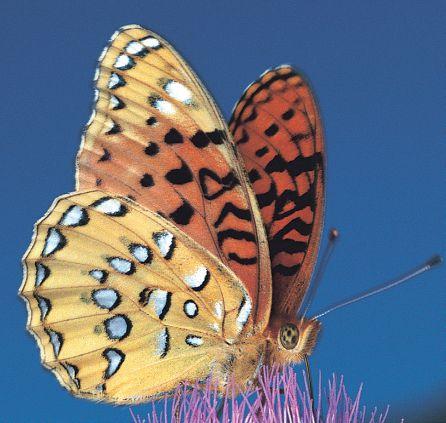

Front Cover photo of a Great Spangled Fritillary was taken on July 31, 2013 along Niagara Creek Rd., Tulomne Co., CA by Jeffrey Glassberg.

The North American Butterfly Association, Inc. (NABA), a non-profit organization, was formed to promote public enjoyment and conservation of butterflies. Membership in NABA is open to all those who share our purpose.

President: Jeffrey Glassberg Vice-president: James Springer Secrty./Treasurer

Ann James Directors: Jeffrey Glassberg

Fred Heath

Yvonne Homeyer

Ann James

Dennis Olle

Robert Robbins

James Springer

Patricia Sutton Scientific Advisory Board

Nat Holland

Naomi Pierce

Robert Robbins

Ron Rutowski

John Shuey

Ernest Williams

Volume 26: Number 1 Spring 2018

Inside Front Cover NABA News and Notes

2 Spring for Hope by Jeffrey Glassberg

4 Go Get Set On Your Marks: Greater Fritillaries Part 3, the Greater Yosemite Region by Jeffrey Glassberg

18 Heliconians: Unraveling the Mysteries Behind the Roosting of Real Social Butterflies by Susan Finkbeiner

28 You Are What You Eat

29 Sleepy Orange on Java-bean Senna in TX, by Don Dubois

31 Queen on Prairie Milkvine in TX, by Don Dubois

34 Taxonomists Just Wanna Have Fun: Flashers! by Harry Zirlin

40 Cuban Swallowtail (Papilio caiguanabus): First Report from the United States by Susan Kolterman

42 Hot Seens by Mike Reese

48 Contributors

Inside Back Cover NABA News and Notes (continued)

American Butterflies (ISSN 1087-450X) is published quarterly by the North American Butterfly Association, Inc. (NABA), 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; tel. 973285-0907; fax 973-285-0936; web site, www.naba.org. Copyright © 2018 by North American Butterfly Association, Inc. All rights reserved. The statements of contributors do not necessarily represent the views or beliefs of NABA and NABA does not warrant or endorse products or services of advertisers.

Editor, Jeffrey Glassberg

Editorial Assistance, Jane V. Scott, Matthew Scott and Sharon Wander

Please send address changes (allow 6-8 weeks for correction) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; or email to naba@naba.org

As I write this, more than a foot of heavy, white snow is blanketing my yard and driveway. A large tree limb fell and crushed my Weber grill — I’ve left it there as part of an ongoing crime scene. About an hour ago, I shoveled some of the snow from the end of the driveway, thinking this would eventually help me get my car onto the street and headed for food and supplies. Then I realized that, being an old guy living alone, if I had a heart attack and fell into the snow, no one would find me until the spring thaw.

If you’ve read this far, you can fairly surmise that I’m not snowed under, felled by a heart attack. However, it’s been a tough winter, a difficult three and a half years, and a truly horrible past ten months.

Things look bad. Poweshiek Skipperlings may imminently go extinct, the first endemic butterfly full species to disappear from the United States and Canada. The burgeoning human population is trampling all other life forms on the planet, disrupting millions of years of evolution that created an Earth that is a wondrous biological paradise of diversity and beauty. The U.S. government threatens to erect an aesthetically, environmentally, financially and morally reprehensible and repugnant border wall through the National Butterfly Center — effectively destroying a vibrant source of life and education that NABA has spent the past fifteen years bringing to fruition. My wife, Jane Vicroy Scott, who gave meaning to my life, died in July.

Given our current realities, having a functioning brain seems to be antithetical to feeling hopeful about the future. My brain has always taught me to be a pessimist, to understand reality and to expect the worst outcomes, so that I could be prepared for their effects and not be crushed by disappointment. And when I talk with people, often it is my brain doing the talking.

But, in addition to having a brain, I also have a heart (see below), even if it is in a particularly vulnerable state at the moment,

[When my wife died, I had a stress heart attack. The heart attack caused my heart to have an arrhythmia. The most common heart arrhythmia is atrial fibrillation, but because I am a butterflier, the actual medical term for my arrhythmia was “atrial flutter.” The cardiologists enjoyed this, claiming that I got the stress heart attack just to be able to tell the joke! After they electroshocked my heart, the arrhythmia seems to be gone and the grill marks have now faded.].

and, to my complete and utter mystification, my heart has always hoped for what it secretly believes is the inevitable triumph of good. I wouldn’t have founded the North American Butterfly Association or the National Butterfly Center if I wasn’t secretly an optimist.

Right now, coming out of the darkness, I’m looking forward to spring. Any day now, the azures and elfins will again appear, and my smile is waiting for their blue wings to take flight and for their sticky feet to grasp the nodding, pink bearberry flowers.

Although the external realities seem as crushing as that tree limb, each of us needs to focus on what we, as individuals, can do to move the world in the right direction, even to a very small degree. We need to irrationally hope that millions of us moving in the right direction will save the day, because it is certain that without hope and optimism, darkness will prevail. Go ahead — plant that host plant, support NABA, It all depends upon you.

Please photocopy this membership application form and pass it along to friends and acquaintances who might be interested in NABA

Yes! I want to join NABA, the North American Butterfly Association, and receive American Butterflies and The Butterfly Gardener and/or contribute to building the premier butterfly garden in the world, the National Butterfly Center. The Center, located on approximately 100 acres of land fronting the Rio Grande River in Mission, Texas uses native trees, shrubs and wildflowers to create a spectacular natural butterfly garden that importantly benefits butterflies, an endangered ecosystem and the people of the Rio Grande Valley.

Name:

Address:

Email (only used for NABA business):______________________ Tel.:______________________ Special Interests (circle): Listing, Gardening, Observation, Photography, Conservation, Other

Tax-deductible dues enclosed (circle): Regular $35 ($70 outside U.S., Canada or Mexico), Family $45 ($90 outside North Am.). Special sponsorship levels: Copper $55; Skipper $100; Admiral $250; Monarch $1000. Institution/Library subscription to all annual publications $60 ($100 outside U.S., Canada or Mexico). Special tax-deductible contributions to NABA (please circle): $125, $200, $1000, $5000. Mail checks (in U.S. dollars) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960

American Butterflies welcomes the unsolicited submission of articles to: Editor, American Butterflies, NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960. We will reply to your submission only if accepted and we will be unable to return any unsolicited articles, photographs, artwork, or other material, so please do not send materials that you would want returned. Articles may be submitted in any form, but those on disks in Microsoft word are preferred. For the type of articles, including length and style, that we publish, refer to issues of American Butterflies.

If you have questions about missing magazines, membership expiration date, change of address, etc., please write to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960 or email to naba@naba.org.

American Butterflies welcomes advertising. Rates are the same for all advertisers, including NABA members, officers and directors. For more information, please write us at: American Butterflies, 4 Delaware Road, Morristown, NJ 07960, or telephone, 973-285-0907, or fax 973-285-0936 for current rates and closing dates.

Occasionally, members send membership dues twice. Our policy in such cases, unless instructed differently, is to extend membership for an additional year.

NABA sometimes exchanges or sells its membership list to like-minded organizations that supply services or products that might be of interest to members. If you would like your name deleted from membership lists we supply others, please write and so inform:

NABA Membership Services, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960

by Jeffrey Glassberg

(genus Speyeria) often produces a great pain in the frass. One of the key reasons for the difficulties is that most of the greater fritillaries vary remarkably in wing pattern, depending upon the exact geographical location of the population — the 13 species of Speyeria have been given something like 140 subspecies names. This extensive intra-species variation

1. Hydaspe Fritillary. July 26, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

2. Callippe Fritillary. July 19, 2005. Little Walker Rd., Mono Co., CA.

3. Great Spangled Fritillary. July 31, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

4. Nokomis Fritillary. Aug. 2, 1997. Mill Creek Rd., Mono Co., CA.

5. Zerene Fritillary. July 21, 1995. One mile west of Devil’s Gate Pass, Mono Co., CA.

6. Atlantis Fritillary. June 29, 2006. Sierra City, Sierra Co., CA.

7. Great Basin Fritillary. July 24, 1995. Dorrington, Calaveras Co., CA.

8. Mormon Fritillary. July 28, 2013. Saddlebag Lake, Mono Co., CA.

makes it difficult to identify characteristics that will reliably separate a particular species from all the other variable greater fritillaries over the vast spread of the North American continent, and especially in the topographically-blessed, western United States.

In an attempt at alleviating your pain, we began a series of articles that focuses on the identification of greater fritillaries in one rather small area, thus making the job of sorting them out much easier. In the spring 1998 issue of American Butterflies, we brought you the first installment of this series of articles, focusing on Rabbit Ears Pass in northern Colorado. Seven years later, the second installment, in the summer 2005 issue, covered Humboldt National Forest in Nevada. This third installment, thirteen years later (too soon?), focuses on Yosemite National Park and surrounding areas in California. Here, you only need to deal with 8 of the 13 species and, more critically, only 10 of the 140 named subspecies! Still, the identity of some individuals will be indeterminate.

The undersides of these butterflies provide much of the identification information, and, in most cases, identification is problematic given a view only of the upperside. That being said, there is useful information, if only negative information, on the topsides as well, so, it is always best to see, or, even better, photograph, both the topside and the underside of the same individual butterfly. Admittedly, this is often quite difficult, but if you try real hard, you’ll (often) find, you can get what you need.

These two large species have a wide, creamcolored postmedian band on the HW below. Great Spangleds have a dark brown disk that is even darker on females (compare photos 9 and 11) while Nokomis has an olive disk on females and a yellow/cream disk on males. Both species have amber-colored eyes, as opposed to the blue-gray eyes of other fritillary species (but see Mormon Fritillary, which is small).

Both of these species are distinctive enough that you are unlikely to confuse them with other fritillaries. However, if your only view is of their topsides, you could confuse these two species with each other.

Above, females of both species are dark brown basally with cream-colored outer areas (see photos 15 and 16, pg. 9). The HW submarginal crescents [A] (photos 15 and 16) differ between the species. On female Great Spangleds, these crescents are separate, on Nokomis, they are connected.

Males above are bright orange. Both species lack black spots at the base of the FW [B] that other greater fritillaries normally possess. However, note that most Hydaspe Fritillaries in the Yosemite region have spots that are very faint or are absent. Great Spangled males have thickened FW veins [C], but Nokomis males don’t. Lastly, Great Spangled males have one black bar at the base of the HW [D] while Nokomis males have two bars.

Opposite Page

9. Great Spangled, female. July 31, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

10. Nokomis, female. Aug. 2, 1997. Ten miles north of Bridgeport, Mono Co., CA.

11. Great Spangled, male. July 31, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

12. Nokomis Fritillary, female. Aug. 6, 2017. Near Little Walker River, Mono Co., CA.

13. Great Spangled, male. July 31, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

14. Nokomis Fritillary, male. Aug. 3, 2017. Near Little Walker River, Mono Co., CA.

Opposite page

Top: Habitat for Great Spangled Fritillary. July 26, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

Bottom: Habitat for Nokomis Fritillary. July 30, 2013. One mile south of Devil’s Gate Pass, Mono Co., CA.

This page

15. Great Spangled, female. July 31, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

16. Nokomis, female. Aug. 6, 2017. Near Little Walker River, Mono Co., CA.

17. Great Spangled, male. July 31, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

18. Nokomis Fritillary, male. Aug. 3, 2017. Near Little Walker River, Mono Co., CA.

In the Yosemite area, Nokomis Fritillaries are found only in large, wet meadows east of the Sierra crest. Great Spangled Fritillaries can be found there as well, but are much more common in moist, grassy, forest openings at mid elevations west of the Sierra crest.

Atlantis, Hydaspe and Zerene Fritillaries

Atlantis

19. June 29, 2006. Sierra City, Sierra Co., CA.

20. July 3, 2014. Soda Springs, Nevada Co., CA.

21. Aug. 9, 2011. Yosemite Creek area, Yosemite NP, Mariposa Co., CA.

Hydaspe

22. July 26, 2013. Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co., CA.

23. July 26, 2013. Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co., CA.

24. July 25, 1995. Big Trees Park, Calaveras Co., CA.

Zerene

25. July 26, 2013. Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co., CA.

26. July 21, 1995. 1 mile west of Devil’s Gate Pass, Mono Co., CA.

27. July 26, 2013. Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co., CA.

Fritillaries can all be confused with each other in the greater Yosemite area, where all of them normally have unsilvered underside HW pale spots. Zerenes occur both west and east of the Sierra crest, with pink/purple individuals westward and paler, browner individuals eastward. Atlantis and Hydaspe Fritillaries occur only west of the Sierra Nevada crest. Both Atlantis and Hydaspe are mid-sized greater fritillaries while Zerenes average larger. Perhaps the best way to recognize Atlantis Fritillaries is to realize that they are not Hydaspe or Zerene Fritillaries.

On their undersides, Atlantis Fritillaries differ in three ways from Zerenes. One, the HW postmedian band is more coherent on Atlantis — the spots are more similarly sized, shaped and aligned — than on Zerene. Two, on Zerenes the dark inward “shadows” capping the HW marginal pale spots are wider than the pale spots [E] (photo 25)(both because the “shadows” are high and because the pale spots are flat). On Atlantis Fritillaries, the “shadows” are either equal to the height of the marginal pale spots or are shorter. And three, Zerenes have a quite pink/lavender HW ground color, while Atlantis normally is browner.

Separating Atlantis and Hydaspe is, in my opinion, more difficult. Although, as with Zerene and Atlantis, Hydaspes are normally more pink/lavender than are Atlantis, the ground color can be similar. In addition, Hydaspes have a HW pm band that is coherent, similar to Atlantis. A difference is that the submarginal pale band is yellow/cream on Atlantis [F] (photo 20) but pink/lavender on Hydaspe [G] (photo 23).

Perhaps the most reliable way to separate Hydaspe Fritillaries from Atlantis and Zerene Fritillaries is by the presence or absence of a black line along the HW leading edge [H] (photo 23). Hydaspes have a sharp black line, while Atlantis and Zerenes either lack the line or have only some diffuse black here [I] (photo 21). Please note that my sample size for this, and other characters, is quite small and thus it is possible that some individuals vary.

28. Atlantis, male. July 6, 2006. No. of Carson Pass, Alpine Co., CA. 29. Atlantis Fritillary, female. July 31, 2013. Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co.,CA.

Above, males of all three of these species have swollen FW veins, while females do not. Above, females have a pale area along the subapical costal margin. Hydaspes can often be recognized by the lack of a strong black spot near the base of the FW [J] and bold black FW pm spots [K] (photo 30). Zerenes have a strong black spot near the base of the FW [L] and a bold black FW median band [M] (photo 32).

30. Hydaspe, male. July 31, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

31. Hydaspe, female. July 31, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

32. Zerene, (western) male. July 8, 2017. Dry Meadow Creek, Tulare Co., CA.

33. Zerene female. Aug. 29, 2009. Crane Flat area, Yosemite NP, CA.

34. Zerene (eastern), male. July 30, 2013. South of Devil’s Gate Pass, Mono Co., CA.

This page

35. July 28, 2013. Saddlebag Lake., Mono Co., CA.

36. July 26, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

37. Aug. 6, 2010. Tuolomne Meadows, Tuolomne Co., CA.

38. Aug. 4, 2017. Sweetwater Mountains, Mono Co., CA.

39. July 26, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

40. July 24, 1995. Dorrington, Calaveras Co., CA.

41. July 30, 2013. South of Devil’s Gate Pass, Mono Co., CA.

42. Aug. 4, 2017. Sweetwater Mtns., Mono Co., CA.

43. June 4, 2004. Paiute Mtn., Kern Co., CA.

44. July 19, 2005. Little Walker River Rd., Mono Co., CA.

Fritillaries can all be confused with one another, especially east of the Sierra crest, where Zerenes are paler and browner than they are west of the crest (compare photos 25 and 41). However, Zerenes average significantly larger in size than the small Mormons and Great Basins. You’ll want to note this in the field, because size is difficult to impossible to determine from photographs.

Until 2013, it was thought that the undersides of Mormon and Great Basin Fritillaries were indistinguishable in the California Sierra. However, it turns out that Mormon Fritillaries in the California Sierra and (as I now realize) up through the Cascades and into Alaska), have amber eyes while Great Basins have typical fritillary blue-gray eyes (compare photos 35 and 38). Admittedly, with some individuals and especially with various angles of view and lighting situations, this may be difficult to determine.

Another feature that appears to have some usefulness for distinguishing Great Basins and Mormons from an underside view is that almost all Great Basins have a HW dark spot [N] (photo 38) that Mormons lack or that is very faint (always?).

Above, Mormon males lack the thickened FW black veins that most other greater fritillary males, including Great Basin males, possess. So, if the individual has swollen FW veins, it’s not a Mormon. If it lacks the swollen veins, then you need to be certain that the butterfly in question is a male before this information is useful. Behavior may provide a strong clue.

Fritillaries in the Yosemite area are fairly distinct. In the western foothills, Callippes fly mainly in June to early July and resemble the individual in photo 43, although the individual shown is from a slightly different population in Kern County. The HW pale spots are unsilvered and quite large while the HW disk is brown, contrasting with the cream submarginal band.

Individuals flying east of the crest are quite different. The HW underside pale spots are still quite large, but the ground color, rather than being brown, is green-tinged, similar to other Callippe populations east of the Sierras and Cascades — making individuals easily recognizable.

All photos this article by Jeffrey Glassberg, except as indicated.

Mormon Fritillary

45. Male. July 31, 2013. Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co., CA.

46. Female. July 31, 2013. Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co., CA.

Great Basin Fritillary

47. Male July 26, 2013. Eagle Meadow Rd., Tuolomne Co., CA.

Great Basin Fritillary

48. Female. July 31, 2013

Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co., CA.

Callippe Fritillary

49. Male. June 13, 2017. Base of Copper Mtn., Mono Co., CA.

50. Female. July 10, 2014. Little Walker River Rd., Mono Co., CA.

by Susan Finkbeiner

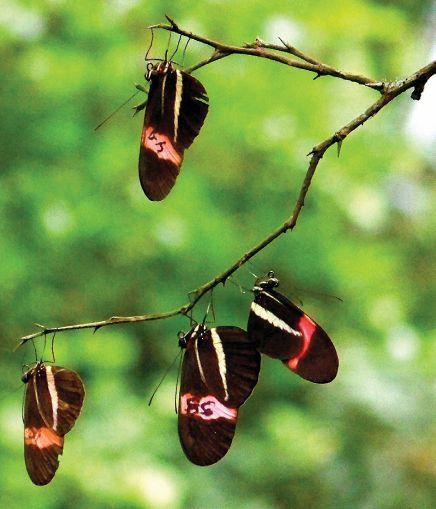

In April 2008, I was out for a late afternoon jog at the La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica. I was there for a semester abroad studying tropical biology. I had been spending mornings working on an independent project with peacocks (the butterflies, not the birds) in a nearby pasture, but in the afternoon would be back at the station enjoying my time in the rainforest. As I was running on a trail, I came upon a gap in the forest and noticed an abnormally high number of Sara Heliconians (Heliconius sara). Some were fluttering around, and others were resting on leaves with their wings closed but not upside-down for sleeping, and not open for basking. This was strange to me. I counted four, five, then six Sara Heliconians, and more appeared out of the forest coming to this single spot. The butterflies would flutter amongst themselves, then go back to sitting upright on large leaves as if they were waiting for something. I could tell something very exciting was going to happen. I stopped my run and decided to deal with the aggressive mosquitoes, and just sit and watch the butterflies. All of a sudden, one of the resting butterflies left its perch on a leaf and flew up to a dead, dry twig hanging just over my head. Then almost immediately another butterfly followed. Then another, and another, until a cluster of about 8-10 butterflies had formed an aggregation on this single twig in the understory. I knew right

Sara Helcionians spend the night in

away what I was witnessing — the formation of a butterfly communal roost — and I was elated! I had learned about Heliconius communal roosting behavior before, and was advised to keep an eye out for it at this field station. However, I had no idea how magical of an experience it would be to see first-hand how the butterflies come together to form these aggregations. I nearly missed dinner that evening at the Station because I was so mesmerized watching the butterflies interact with one another at their roosting site. From that point on, I knew I would dedicate part of

communal roosts. April 29, 2011. La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica.

my career as an entomologist to understanding more about the dynamics of this behavior and why these butterflies form communal roosts.

William H. Edwards was the first to describe Heliconius communal roosting behavior in Zebra Heliconians in Florida in 1881. The adaptive function of communal roosting in Heliconius, or the biological significance as to why these butterflies form these aggregations, has remained a mystery since then. Heliconius are widespread throughout the neotropics, including a few species that are found in the United States.

Most species of heliconians form intricate communal roosts in which the each individual butterfly goes back to its exact same roosting location in the late afternoon, the group roosts together overnight, then departs in the morning to go to their preferred foraging sites. The butterflies return to their roosting locations night after night for months on end. This behavior is extraordinary because any sort of grouping behavior or social behavior in adult butterflies is quite rare outside of migratory species. Butterflies are historically solitary animals, but the case of communal

Beautiful Sara Heliconians are worth observing, even if you are not conducting a scientific study! April 12, 2005. Rancho Naturalista, Costa Rica.

roosting in Heliconius shows an example of “real” social butterflies.

When I began graduate school, I was determined to work with Heliconius to resolve once and for all why the butterflies exhibit this special behavior. But first of all, I needed background information about why the butterflies are capable of forming these aggregations to begin with.

Heliconians have a unique life history in that they not only rely on nectar as a food source, but also feed on pollen from specific flowering plants (especially lantanas, cucumber vines and wild coffees). Heliconius have special enzymes in their saliva that allow them to break down these pollen grains into a drinkable form, so these butterflies are often found with large pollen loads on their tongues because it takes several hours for the butterflies to digest it. The pollen provides added protein and nutrients not easily obtained from nectar alone, therefore this pollen supplement allows heliconians to live up to 6-8 months in the wild — much longer than

most butterflies.

In addition to the long lifespan, these butterflies also have something called a limited learned home range. Once they emerge from their chrysalis, they disperse to an area that has all necessary resources: host plants, pollen plants, potential mates, and roosting sites, and they spend their entire adult lifespan in this single home range. The home range is usually a few square kilometers at most.

On top of this, heliconians are actually quite smart. Their brains are about 50% larger than the average butterfly brain when you compare brain mass to body mass, and they have incredible memory retention and a high learning capacity. Many aggregate insects form aggregations based on pheromone cues, whereas Heliconius rely on memorization, visual cues, and landmarks to locate their roosts every night. They are also well-known for their trapline networks when foraging, meaning they visit the same series of plants in the same order, and at the same time, daily. On the contrary, many other butterflies may hop

around from location to location when looking for resources rather than stick to the same foraging patches in a given area.

And finally, one of the biggest promoters of successful communal roosting behavior in Heliconius is the fact that they are unpalatable — these butterflies are highly toxic because, as caterpillars, they feed on passionflowers. The cyanogenic passionflower toxins are passed on to the adult butterfly, providing protection during the rest of their adult life span. Because Heliconius are brightly colored and poisonous, their wing coloration is predicted to serve as a warning signal toward predators and therefore

predators (typically birds) avoid these butterflies at all costs.

In the scientific literature, there are two major hypotheses, or predictions, regarding why Heliconius form communal roosts. One prediction suggests an information-sharing hypothesis — that an advantage of communal roosting is that individual butterflies may learn the locations of ideal foraging sites from other roost-mates by following them as they disperse in the morning. This would make sense given their feeding specialization on precious, specific pollen plants, which may be difficult to locate in the vast rainforest

understory. This type of information-sharing is common in other communal animals, for example ravens, who convene in a particular location at night then follow one another to ideal foraging sites in the mornings. It is possible Heliconius participate in such information-sharing dynamics given that following between individuals is common, and, roost-mates are often seen foraging at the same flowering plants together.

The second possible explanation for why Heliconius form aggregations is that it provides an anti-predatory benefit, through a mechanism called collective aposematism. Aposematism is a fancy term for warning signaling and is often used by animals to communicate unprofitability to predators such as toxicity or distastefulness. With Heliconius, we know that the butterflies already exhibit these aposematic bright warning colors on their wings, and that they are infused with noxious toxins from their caterpillar foodplants. It is predicted that when in a group, multiple aposematic individuals together enhance the effectiveness of this warning signal thus giving rise to the idea of “collective aposematism.”

Given this information, I traveled to Central America to test both of these predictions: The information-sharing hypothesis and anti-predatory hypothesis. But

Top left: A flesh-and-blood Erato Heliconian (minus the flesh and the blood). Aug. 3, 2015. Tabasco, Mexico.

Top right: An artificial model Erato Heliconian holds its breath (easy to do) and waits for a bird. May 5, 2012. Gamboa, Panama.

Bottom: An Erato Heliconian roost with individuals marked for study. Aug. 2011. Gamboa, Panama.

Erato Heliconians occasionally stray to south Texas, but no roosts have been seen there because it is normally a single individual stray. March 1, 2017. Canopy Tower, Panama.

before I could run any experiments, I needed to locate the communal roosts themselves. Finding roosts was always a treat, and one of my favorite parts of doing field research with this behavior. I am often asked, “How do you find so many roosts? They are so difficult to locate!” And my answer is always, “To find the butterflies, you have to think like one!”

So this is my secret: The best way to locate a communal roost is to pretend you are a butterfly. Find where they forage, and find dry, brittle twigs under a protected part of the understory that would make a nice shelter from the wind and rain. Find the host plants and pollen plants, and you will almost certainly find the butterflies too. Once one finds where Heliconius forage regularly during the day, it is quite easy to just follow these slow-flying butterflies in the late afternoon until they reveal to you their nearby roosting site, where you will find many other butterflies from the same population coming to roost together.

There is always a sense of excitement and joy every time I locate a new communal roost. It is possible to get very close to the aggregations, even when the butterflies are forming them, making it an enchanting experience to be a part of this phenomenal butterfly behavior in nature.

To test the information-sharing hypothesis, I spent months observing communal roosts of Sara and Erato Heliconians in Costa Rica and Panama. I tirelessly watched butterflies arriving to roosts in the evening, and departing roosts in the morning, to see whether they followed one another in the mornings from the roost to potential resources. In order to keep track of every single individual, I captured and individually marked butterflies with numbers using a Sharpie marker (see photo, opposite page). Over time I could notice very interesting personalities in butterflies, for example some always arrived first to the roost, and others were always last to leave in the morning.

I observed nightly roosting behavior in more than 100 butterflies from 13 communal roosts total, during six months of data collection. Of my observations combined, I found only one instance of following behavior between Erato Heliconians and no following behavior between Sara Heliconians. Based upon these results, I concluded that heliconians do not rely on communal roosts as information-sharing centers. However, other observations of mine show that the butterflies forage together, and that new roosts are initially formed through following behavior, so it is likely that the butterflies are not using roosts as information-sharing centers because the same individuals are already familiar with the resources in that part of their home range and no further following behavior is necessary.

After testing the information-sharing hypothesis, I then set out to test whether communal roosting in Heliconius might serve as an anti-predatory benefit through collective

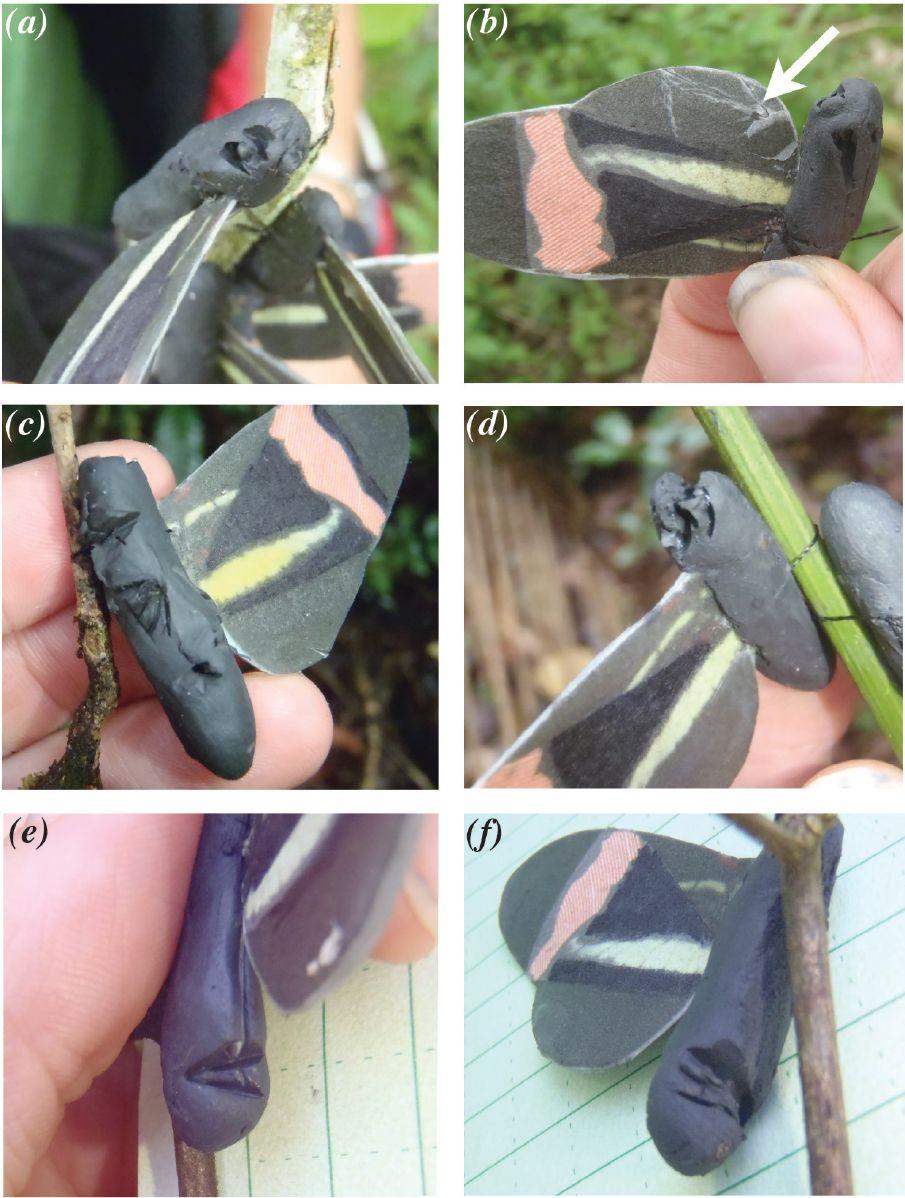

aposematism. Going into this project, I knew testing this theory was going to be difficult. My colleagues and I eventually decided that the best way to vigorously test this in field experiments would be to produce thousands of artificial butterflies for use in predation studies. I designed paper butterfly models, that resembled Erato Heliconians. The models were printed on a special filter paper and even included some of the actual butterfly wing pigment on them to accurately represent real butterfly wings as best as possible. Using these artificial, fake butterflies, I set out 320 single butterflies, and 320 roosts of five, at a field location in Costa Rica. The artificial butterflies were left exposed to bird predators for four days and checked daily for predation.

The author made model butterflies, resembling Erato Heliconians, out of special filter paper and actual butterfly wing pigment (for the wings) and plasticine (for the bodies). The artificial models were placed in differently sized model “roosts” and bird attacks were monitored by examining the models for beak marks.

Images (a)-(f) show examples of bird attacks on artificial Heliconius erato butterfly models, indicated by attack marks and beak marks on the plasticine abdomen. Image (b) has an arrow pointing at a triangular beak mark on part of the butterfly model wing.

Sure enough, I found that the single butterflies were attacked significantly more than aggregations of butterflies. Given this exciting result, I decided to expand on this finding and examine predation rates on different sizes of communal roosts. Using the same methods, I set out 200 roosts each of two, five, and ten artificial butterflies (total 600 roosts, and a grand total of 5,320 artificial butterflies used in both projects combined). This part of the project was done in Panama where communal roosts of Erato Heliconians are abundant.

After several months of data collection, I found something very peculiar: birds avoided attacking communal roosts of five, but readily attacked roosts of two or ten butterflies. This result was opposite my prediction because I suspected that as butterfly aggregation size increased (i.e. from a roost of five to roost of ten), that predation would decrease, by definition of collective aposematism. But that did not appear to be the case and roosts of ten were attacked significantly more than roosts of five.

Although I was perplexed with this result regarding my predation studies, I noticed something: there appeared to be an optimal group size for these butterflies. With further natural roost observations

over the course of four months in Panama, I found that the average roost size for Erato Heliconians was between 4-5 individuals. This striking information provided evidence that the experimentally optimal group size (roost of five) corresponds very closely with the average number of butterflies found at these roosts in nature, which is also about five individuals. Combining these results, I surmise that predators learn to avoid aggregations of particular sizes in these butterflies and associate group size with the strength of the warning signal from these toxic butterflies.

However, in the field I continued to notice something peculiar: Even in a forest patch, say, the size of your average suburban backyard, I would find multiple communal roosts of Erato Heliconians, rather than one large roost. I could tell the butterflies were well aware of the presence of other roosts in the area — butterflies from different roosts would flutter amongst themselves, sometimes even go and perch temporarily on another roost, then return to their preferred roost for the night. This was very intriguing to me considering the roosts had plenty of substrate to support much larger aggregations, yet for some strange reason the butterflies decided to disperse to smaller roosts for the night. This got me thinking: are butterflies being picky and choosy about how big their aggregations are? Is there a preference to join a roost of a particular size? Will butterflies prefer to join roosts that are the same size as the average number of roosts found in the home range (five), and will they abandon established roost when they get too large?

I tested these questions both experimentally in greenhouses, as well as with manipulated wild roosts in Panama. I created dummy “roosts” of two, four, and ten individuals using real, but dead butterflies placed in roosting positions. Now you might be wondering, that makes no sense that a real, wild butterfly would want to roost with dead butterflies! But they did, and they

did very well. My greenhouse experiments showed that most butterflies preferred to join a medium-sized roost over a small or large roost. My field experiments with natural, wild roosts showed that butterflies eventually left large roosts and started new, smaller roosts nearby. In fact, some of the same three or four butterflies preferred to stick together as they started a new roost when the original roost got too large and I thought this was so fascinating! From both wild roost data and greenhouse roost data, I concluded that butterflies prefer to roost in medium-sized groups, and leave roosts when they get too big, but for unknown reasons. Their preferred roost size corresponds with optimal roost sizes from the predation study, as well as the average number of butterflies found in natural roosts. This provides evidence that the butterflies were capable of assessing the magnitude of their group size, and (possibly) regulating their roost sizes by adjusting them to these medium-sized groups.

I had finally unraveled the mystery behind the adaptive function of communal roosting behavior in Heliconius, which had puzzled biologists for over a century. Ultimately these results help provide insight into the types of ecological pressures that drive the evolution of social behavior in historically solitary animals, such as butterflies. I have continued my work with Heliconius communal roosting when possible, and anticipate digging even deeper into the dynamics of this behavior to find out, from an individual butterfly’s perspective, why they choose to join a roost, what causes them to leave a roost, and why they prefer to roost over and over with the same individuals. After all, being a social butterfly is more complex than one might think.

We have initiated a project to document the caterpillar foodplants of North American butterflies. For those who would like to participate in this photodocumentation, here are instructions:

Find an egg or a caterpillar (or a group of eggs or caterpillars) on a single plant in the “wild” (this includes gardens). The plant does not need to be native to the area — we want to document all plants used by North American butterflies.

Follow this particular egg or caterpillar (or group of eggs or caterpillars) through to adulthood, with the following documentation.

1. Photograph the actual individual plant on which the egg or caterpillar was found, showing any key features needed for the identification of the plant.

2. Photograph the egg or caterpillar.

3. Either leave the egg or caterpillar on the original plant, perhaps sleeving the plant

it is on with netting, allowing the caterpillar to develop in the wild, or remove the egg or caterpillar to your home and feed it only the same species of plant on which it was found.

4. Photograph later instars of the caterpillar.

5. Photograph the resulting chrysalis.

6. Photograph the adult after it emerges from the chrysalis.

7. If the egg or caterpillar was relocated for raising, release the adult back into the wild at the spot where you found it.

We would like to document each plant species used by each North American butterfly species, for each state or province.

In addition to appearing in American Butterflies, the results of this project will be posted to the NABA website. Please send any butterfly species/plant species/state or province trio that is not already posted to naba@naba. org.

Opposite page

Top left: A Java-bean Senna volunteered in the author’s yard. Aug. 27, 2012. Montgomery Co., TX.

Top right: An egg was seen on a leaf. Aug. 27, 2012. Montgomery Co., TX.

Bottom: A few days later a caterpillar emerged. Aug. 30, 2012. Montgomery Co., TX.

by Don Dubois

Considered as a weed in much of the South, a Java-bean Senna showed up as a volunteer in my garden in the Houston, Texas area. An alternate common name, sicklepod, is due to its long slender curved seedpod.

A single egg was found on August 27 and the entire plant, which was only about a foot tall, was netted. A small greenish caterpillar hatched on August 30 and made a jade-green chrysalis on September 7. A Sleepy Orange emerged on September 12.

Top: The caterpillar on Sept. 6, 2012. Montgomery Co., TX.

Bottom left: The caterpillar pupated on Sept. 7, 2012. Montgomery Co., TX.

Bottom right: The adult emerged on Sept. 12, 2012. Montgomery Co., TX.

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Sleepy Oranges. Orange indicates three broods. Purple indicates two broods. Turquoise indicates one brood. Cherry spots are locations where strays have occurred. (drawing from A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

Above: The approximate range of Java-bean Senna, based upon county occurrence data from the Biota of North America Program. This might be a useful plant for your garden if you live within the range shown, however, keep in mind that it is toxic if ingested and is considered to be weedy by some.

by Don Dubois

Above: A Prairie Milkvine in the author’s yard. May 22, 2014. Montgomery Co., TX.

Right: A close-up of flowers. May 24, 2014. Montgomery Co., TX.

Prairie Milkvines are not common but they are widely distributed across the eastern half of Texas and into Oklahoma. The plants in my garden were grown from several windblown “milkweed” seeds that were collected without knowing what they were. The seeds appeared to be germinating during dispersal and were

planted immediately to see what kind of milkweed might sprout. As the plants grew to maturity it became obvious that they were not one of our “regulars” and upon blooming it was determined that they were, in fact, Prairie Milkvine.

For several years the plants sported the usual accompaniment of milkweed insects but no milkweed butterfly caterpillars. This changed on August 11 of this year when a

sizable queen caterpillar was noticed feeding on the milkvine. The caterpillar was brought inside and fed additional clippings from the host plant. After only two days from discovery, the caterpillar stopped feeding and made a “J” on the container. A chrysalis was formed on August 14 and the butterfly emerged on August 23. Photos were taken periodically to document its progression.

Opposite page:

Top: A Prairie Milkvine seedpod. Aug. 11, 2016.

Bottom left: A Queen caterpillar was found on the plant. Aug. 11, 2016.

Opposite page

Bottom right: The caterpillar pupated on Aug. 14, 2016.

This page: The adult Queen emerged on Aug. 23, 2016.

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Queens. Orange indicates three broods. Purple indicates two broods. Cherry spots are locations where strays have occurred. (drawing from A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

Above: The approximate range of Prairie Milkvine, based upon county occurrence data from the Biota of North America Program. This might be a useful plant for your garden if you live within the range shown.

by Harry Zirlin

United States, most skippers are small and not brightly colored. That doesn’t mean that they are not beautiful and intriguing in many ways, and I enjoy seeing the less common species immensely. There are a few bigger, snappy ones here, such as Silver-spotted Skipper and Hoary-edge, both of them representatives of tropical groups that have made it this far north and both breed and overwinter here. Another skipper of tropical affinities that sometimes makes it up this way (but typically without breeding) is Long-tailed Skipper, sporting flashing, iridescent green hindwings with handsome trailing tails. But, with those few exceptions, brightly colored skippers in this hemisphere are mainly tropical beings.

Perhaps the most stunning of these, and certainly the most brightly colored of those that enter the U.S., belong to the genus Astraptes, known as “flashers” in English. As of the date of this writing, six species of Astraptes have been reliably recorded from the U.S., all from southern Texas. Of those six, four have been seen at NABA’s National Butterfly Center (NBC): Two-barred Flasher, Yellow-tipped Flasher, Gilbert’s Flasher and

Frosted Flasher.

The word Astraptes means “lightning” in Greek and was first used by Jacob Hϋbner in 1819 in an obvious reference to the electric blue flashing colors of the wings. The flasher most consistently recorded from south Texas, although none of them are common, is Two-barred Flasher, Astraptes fulgerator. Fulgerator also means lightning, this time in Latin, so Two-barred Flasher could also be called ”Two-bolts of Lightning Flasher.”

Bottom left: Frosted Flasher (Astraptes alardus). May 22, 2017. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX. Note the strong resemblance to

Bottom right: the Dutch humanist, Alardus. Photo of a woodcut by Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen. 1523.

Two-barred Flasher had already been named fulgerator by Walch in 1775, before Hϋbner created the genus name Astraptes, which may explain how it wound up with its doubled name.

Over the last 15 years or so, it has been maintained that the butterfly we call Twobarred Flasher is actually a group of species. According to a 2004 article “Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterfly Astraptes fulgerator” by Paul Hebert, Erin Penton, John Burns, Daniel Janzen and Winnie Hallwachs, there are ten different species that have had the name fulgerator applied to them on the Guanacaste Reserve in Costa Rica alone. How many more there are across its wide range from Texas to Argentina can only be guessed at now. This view is based on (i) DNA barcoding, (ii) ecological associations including host plant differences, (iii) different

This page

Top left and right: Yellow-tipped Flasher, Astraptes anaphus. Oct. 28, 2008. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

Bottom left and right: Smallspotted Flasher, Astraptes egregius. Oct. 22, 2015. Wejlib-Ha, Chiapas, Mexico.

Opposite page

Left: Two-barred Flasher, Astraptes fulgerator. March 1, 2006. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

Right: Two-barred Flasher. Sept. 25, 2007. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

color patterns of the caterpillars, and (iv) subtle differences in color, wing shape and size in the adults. Apparently the caterpillars of each species are much more different from caterpillars of the other species than the adult butterflies are. This view, however, was not unanimously accepted and Andrew Brower maintained in a 2005 article named “Problems with DNA barcoding for species delimitation: Ten species of Astraptes fulgerator reassessed” that the data relied upon did not support the existence of ten species, although even he appears to accept that more than one species exists under the name “fulgerator.”

Although the 2004 article by Hebert et al. maintained that there were ten species on the Guanacaste Reserve all going by the same name, they referred to each species by a code name and did not bestow scientific names upon any of them. Years later, Brower (who we just saw was something of a critic of the ten species view) named each of the ten species in a 2010 article entitled “Alleviating the taxonomic impediment of DNA barcoding and setting a bad precedent: names for ten species of Astraptes fulgerator with DNAbased diagnoses.”

One of the ten purported species from the Guanacaste Reserve Brower named Astraptes augeas. He named it thus in reference to the fifth labor of Hercules, who was required

to clean out the stables of Augeus of Elis. The name was given in recognition of the enormous labor involved in the DNA barcoding project to sort out the fulgerator complex. Indeed, all ten names authored by Brower in his 2010 article had a tongue-incheek aspect and Brower, while fixing the ten species with scientific names, maintained that his doing so did not mean he endorsed the scientific validity of the species he was naming. For now, we can enjoy the beauty of the butterflies and await a consensus on just how many species of “Two-barred Flashers” exist.

Small-spotted Flasher, Astraptes egregius, has a name, given by Butler in 1870, that means “excellent” or “surprising.” Note that the English word “egregious” means “conspicuously bad” but an archaic meaning is “remarkably good.” This species is a much rarer stray to southern Texas than Two-barred Flasher. It is one of the two species of Flashers not seen at the NBC. In fact, there are no known records anywhere in the United States for at least the past 30 years, although I doubt that it was given the appellation “surprising” or “excellent” for that reason. Judging from images, it is certainly an attractive species.

Yellow-tipped Flasher, Astraptes anaphus, on the other hand, has a name, given by Cramer

in 1777, that means “dull” or “insipid.” It’s an attractive skipper in my opinion, but does lack the bright blue and green colors of its congeners, so it could be viewed as dull in comparison with the other, gaudier flashers.

Green Flasher, Astraptes talus, was recently added to NABA’s online checklist. It was seen on Oct. 30, 2014 in Mission, Texas and is the other flasher yet to be observed at the NBC. Named talus by Cramer in 1777, but why, I do not know. Talus is an odd word, with multiple meanings. In Latin, it refers to the ankle and the talus is one of a group of foot bones making up the tarsus, or lower part of the ankle joint. Talus is also a geological term, meaning a slope formed by an accumulation of rock debris. Talus slopes are the favored habitat of several high altitude butterflies, such as Magdalena Alpine, but I do not believe the Green Flasher is among them. The geological meaning of talus is from Middle French but is probably ultimately derived from a different Latin word “talutum” meaning slope. Neither of these meanings of the word talus appears to me to be related to the name for Green Flasher. It may be that talus, in this context, like so many other butterfly names, is based on the name of a mythological or literary character. Talus is the name of a character in Edward Spenser’s long English allegorical poem from 1590 “ The Fairie Queen.”

Gilbert’s Flasher, Astraptes gilberti, was named by Texas skipper expert H. A. Freeman for his son Gilbert, who he had said was very interested in the genus. In fact I know this because Freemen helpfully stated why he named the species “Gilberti” in the description. Many of the skippers that H. A. Freeman named were named by him for family members and friends. Linda’s and Celia’s Roadside-Skippers come to mind. Freeman also named a Flasher for his wife Louise in the same article he named Gilbert’s Flasher, although that name seems to have been sunk in synonymy. Indeed, some recent lists sink Gilbert’s Flasher in synonymy with Astraptes alector, although Freeman pointed out the differences between Gilbert’s Flasher and alector in the article that described Gilbert’s Flasher as distinct. Interesting to me is that the lists that lump alector and gilberti still refer to the taxa by the English name “Gilbert’s Flasher.”

The sixth species recorded from the USA is Frosted Flasher, Astraptes alardus, named by Stoll in 1790. The English name comes from the conspicuous and large patches of white “frosting” on the undersides of both the forewings and hindwings. Alardus (14911544) was a Dutch humanist scholar, although I do not know if the scientific name alardus is related to this.

In addition to the six species recorded from Texas, there are 27 more species recorded from Mexico south to Argentina, and that does not include the taxa named by Brower. Looking at a list of the names with the date of description, the most recently described species is Astraptes mabillei, named in 1989 from Bolivia. Other than that, the majority of species were described in the 18th and 19th centuries. I expect that as the group is more carefully studied, more species will be added to the list.

Opposite page

Left: Green Flasher, Astraptes talus. The origin of the name talus is a mystery. July 25, 2012. Santa Clara, Cocle, Panama.

Right: Green Flasher. April 11, 2011. Manu Rd., Peru. This page Gilbert’s Flasher, Astraptes gilberti, was named for Gilbert Freeman, H.A. Freeman’s son.

Top and left: Gilbert’s Flasher. March 13, 2004. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

by Susan Kolterman

A Cuban Swallowtail, endemic to eastern Cuba, rests at John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, North Key Largo, Monroe Co., FL. June 19, 2017.

I am a volunteer at Dagny Johnson Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park and Crocodile Lake NWR (that’s just its shortened nickname). After monitoring the Grove trail at the nearby John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park for Schaus’ Swallowtails for ten weeks, one finally was sighted on June 16, 2017.

Three days later, on June 19, 2017, I thought I would monitor an extra day this week and boy did we get lucky! We did not see a Schaus’ but we did see 24 species of butterflies — nine more than any previous

survey in 2017. On the Grove Trail, leading to an historic key lime and mango grove, I saw what I thought was a Polydamas Swallowtail and was surprised that it was nectaring and hanging out so I took a couple of pictures and just kept going. When I got home, I looked at the pictures and laughed because it didn’t look anything like a Polydamas so I sent my pictures to the big guns and was pleasantly surprised to find out that it is a Cuban Swallowtail (Papilio caiguanabus) and a first sighting for the United States. Yay!

“This book stands alone. It gently guides you step-by-step on the path to creating an accomplished butterfly garden, and it makes you feel as though you have been welcomed into a group of butterfly-gardening friends. The presentation is clear and concise, the butterfly and plant charts are indispensable, and the photographs are incredible.”

Rick Mikula, president

of Butterfly Rescue International

By November, throughout most of North America, butterfly sightings are starting to wind down and butterfliers are hoping to see their last butterfly of the year or look forward to their first sightings from the new year. November submissions of note in 2017 included a November 1 rare photograph of a Zarucco Duskywing caterpillar on Shyleaf, in Sarasota Co., FL by John Lampkin; a November 1 report by Beth Polvino of 2500 roosting Monarchs, found by Michael O’Brien, at St. Pete’s Beach Crossover in Cape May Co., NJ; a November 2 sighting from Wheaton, Montgomery Co., MD by Scott Baron of a Cloudless Sulphur, a late date in this location; a November 4th list from Bart Jones of 13 species including a Monarch flying in Parsons, Decatur Co., TN after two nights of freezing temperatures; and a late date for a Long-tailed Skipper for south New Jersey on November 5 by Beth Polvino at NABA garden #1151, Cape May Co., NJ.

On November 10 Jim Egbert observed abundant Monarchs moving west, in numbers not witnessed by him in decades, on Plantation Rd., Gulf Shores, Baldwin Co., AL; on November 11, Denis C. Quinn, after 19 degrees overnight, was surprised to see a Clouded Sulphur flying after noon in 37 degrees temperature, one mile west of U.S. route 1, on Mason/Dixon — MD/PA-19362; Dale Bonk saw four Zebra Heliconians and a White Peacock, an uncommon butterfly here, on November 15 in Vernonburg, Chatham Co., GA; Andrew Block reported a Clouded Sulphur on November 21, the latest in the year he has seen a butterfly in the northeast, at Highridge Plaza, 1789 Central Park Ave., Yonkers, Westchester Co., NY; and, on November 25, Barbara Peck saw a late Painted Lady in River Park, Shasta Co., CA.

by Michael Reese

The spiffily patterned Zarucco Duskywing caterpillar doesn’t closely resemble the black-scaled adult that it will become. This one was photographed on Nov. 1, 2017 on Shyleaf in the Celery Fields Butterfly Garden, Sarasota Co., FL by John Lampkin.

As noted in the last issue, in the East, Monarchs appear to have had a better year than they have had for quite a while. On Nov. 2, 2017, Beth Polvino photographed this cluster, part of 2500 roosting Monarchs, at St. Pete’s Beach Crossover in Cape May Co., NJ.

Other November sightings of note included five Clouded Sulphurs, all nectaring on dandelion, reported by Denis C. Quinn on November 26 along Mason/Dixon MD/PA; a Cabbage White and four Common Buckeyes seen by Jim Wilkinson at Masonville Cove Environmental Education Center, MD on November 28; a report of a late date for an Eastern Comma reported on November 28 by Bob Yukich from High Park, Toronto, Ontario; and a sighting of a Monarch flying west into the wind on November 29 by Steven Rosenthal at Pt Lookout, Firemen’s Memorial Park, sand trails, Nassau Co., NY.

December butterfly sightings included two Clouded Sulphurs observed by Jeanette Klodzen on White Rock Trail (Antelope Island), Davis Co., UT on December 1; a fresh male Monarch reported by Steven Rosenthal and Harry Zirlin from Orient Beach State Park, beach/playground parking area, Suffolk Co., NY on December 2; an Eastern Comma flying on December 11 two days after a snowfall, reported by Jim Wilkinson from the Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center, Queen Anne’s Co., MD; a December 11 sighting of an Orange Sulphur seen flying at 40 degrees in Crocheron Park, Queens Co., NY by Steve Walter; and a December 14 submission from David H. Bartholomew from Rancho San Antonio Open Space Preserve, Santa Clara Co., CA of two Painted Ladies hilltopping and a flyby Red Admiral

January sightings of note included a January 7 report by Jim Egbert at the Ft. Morgan Historic Site, Baldwin Co., AL of 11 Monarchs with temps in the 30s to start the day; an American Snout seen on January 21 by William G. Haley Jr. in Chattanooga, Hamilton Co., TN with temps in the 60s; a Mourning Cloak on January 23, his first butterfly of the year, submitted by John Heyse from Crockett Hills Park, Crockett, Contra Costa Co., CA; and a very early Anise Swallowtail from Muir Land Trust, Contra Costa Co., CA on January 28 observed by John Heyse.

Florida sightings included a November 5 submission by Ron Smith from Fort De Soto Park, Pinellas Co., of 20 species including 11 Mallow Scrub-Hairstreaks On November 14, 25 Julia Heliconians were observed at one of the most northern colonies of this species by John Lampkin at the Fred and Ida Schultz Preserve, Hillsborough Co.; and six species including two Large Orange Sulphurs were reported at Key West Tropical Forest and Botanical Garden, Monroe Co., on December 3 by Amelia Grimm. Other Florida sightings included two fresh Atalas on December 12 at Long Key Natural Area, Broward Co., by Allen Belden; eight species including Mangrove Skipper and Obscure Skipper on December 18 submitted by Ron Smith from Fort De Soto Park, Pinellas Co.; and a report from Walter Wallenstein on January 27 of two of the federally endangered Florida Leafwings at Long Pine Key, Everglades NP.

As always, many great butterflies were seen during the Texas Butterfly Festival, run by NABA’s National Butterfly Center (NBC) in Mission, Texas. These included the second U.S. record of an Alana’s White-Skipper, found by Jeffrey Glassberg at the NBC on Nov. 5 (the first record was also from the NBC); a Strophius Hairstreak found by Jeffrey Glassberg on Nov. 6; sightings of a Pale-spotted Leafwing, Four-spotted Sailor, Guatemalan Cracker, and Orange Banner, an extremely rare stray to the Valley with less than a handful of records, on Nov. 7, reported by Matt Orsie and others; and sightings of a Common Banner, Dingy Purplewing, Red Rim, Gray Cracker, and Ruddy Daggerwing on Nov. 8. Later in the month, on Nov. 18, at the National Butterfly Center, Mark and Holly Salvato reported 56 species including a Rosita Patch. Karl and Dorothy Legler reported 16 species at the NBC after a prolonged cold period including many fresh Lyside Sulphurs on January 21.

Other Texas sightings included a Nov. 7 report from Austin of a Potrillo Skipper, by Dan

The National Butterfly Center in Mission, Hidalgo Co., Texas continues to produce rarities!

Top left

The second record of an Alana WhiteSkipper in the United States. Nov. 5, 2017.

Top right

Common Banners are scarce in the United States. This female seen on Nov. 8, 2017, hung around for more than a week.

Bottom left

Strophius Hairstreaks are very rare strays to the United States. Nov. 6, 2017.

Bottom right

One of the few Orange Banners every seen in the U.S., this one was the first for the National Butterfly Center. Nov. 18, 2017.

Hardy; while a Nov. 21 report from Daniel Jones in his Progresso yard listed 50 species including Red-bordered Pixie and Statira Sulphur A Tiger Mimic-Queen was found at Quinta Mazatlan, McAllen, Hidalgo Co. on Dec. 2, one of the few records from the U.S. and seen by mob. A Dec. 19 list of 28 species included a Giant White and an Olive-clouded Skipper from Estero Llano Grande State Park reported by Karl and Dorothy Legler. On Dec. 5, William D. Beck reported two White Scrub-Hairstreaks from Hugh Ramsey Nature Park, Harlingen, Cameron Co. And, on Jan. 5, Keith Godwin saw a Tropical Leafwing in Government Canyon SNA, Bexar County, rare for this area.

Whether you see an unusual butterfly, an early or late sighting of a common species, or have a complete list of the species you have seen, we would appreciate hearing from you. Please send your butterfly sightings to sightings@naba.org. Those who record your sightings to the Butterflies I’ve Seen website can just click on “email trip” and send it to the address given above. Your sightings will go into the larger database and will also be available for others to see on the Recent Sightings web page.

This page, top

A Rosita Patch at the National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX on Nov. 18, 2017. The editor of American Butterflies keeps missing this one.

Bottom

A Four-spotted Sailor. Nov. 7, 2017. Mission, Hidalgo Co., TX.

Opposite page, top

One of the very few Tiger MimicQueens ever seen in the U.S. Dec. 2, 2017. Quinta Mazatlan, McAllen, Hidalgo Co., TX.

Bottom

A Potrillo Skipper just north of its usual range. Nov. 7, 2017. Zilker Botanical Garden, Travis Co., TX.

Don Dubois’ formal training is in the area of chemistry, with a Ph.D. from the University of Kansas. He retired in 2002 after working 32 years as a chemical researcher and relocated to the Houston, Texas area. Since then Don has busied himself converting a large barren backyard into a butterfly friendly habitat. This gardening effort has been rewarded with visits by over 80 species of butterflies, several of which were county records. His interest in butterflies and insects started at an early age and involved the usual insect collection. With the availability of good quality, reasonably priced digital cameras, collecting was abandoned in favor of photography. Don’s interest in native plants has been nurtured by volunteering with native plant specialists at Mercer Arboretum and Botanic Gardens.

Susan Finkbeiner is an entomologist and evolutionary biologist whose research focuses on butterfly diversity, ecology, and evolution. Her previous research has used Heliconius butterflies to examine how natural and sexual selection work together to favor the evolution butterfly wing patterns, how wing signals may drive the evolution of social behavior in the context of visual ecology, and how butterfly visual systems coevolve with specialized visual cues. Her current research

aims to understand the ecological and evolutionary processes that shape temporal and spatial patterns of sisters (genus Adelpha) biodiversity. Susan received her B.Sc. in Entomology from Cornell University and then obtained her Ph.D. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of California, Irvine. She then was a postdoctoral research associate at Boston University and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago.

Jeffrey Glassberg brief biographical sketch appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of American Butterflies.

Susan Kolterman is a volunteer for Dagny Johnson Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park and Crocodile Lake NWR. Ten years ago if you had asked why she wanted to volunteer, it was because she wanted to learn more about native plants. Besides learning more about local botany, her thirst for knowledge has exploded into birding, herpetology, butterflying, lichenology. She believes that the best part of her experience has been the people she has met along the way. The goofy picture of her was taken after she enjoyed the smell of a native spider lily and then realized that she had pollen all over her face.

Mike Reese’s brief biographical sketch appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of American Butterflies.

Harry Zirlin’s brief biographical sketch appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of American Butterflies.

(continued from page inside front cover)

and used by the hairstreaks, we will then expand the project, growing many more crotons to plant over a much larger area.

Regardless of the outcome of this exciting citizen conservation project, we believe that we will learn valuable information about Bartram’s ScrubHairstreak that will be useful in the continuing efforts to save them.

NABA is thrilled to announce that we will soon be making available to the public new pages, at www. webutterfly.org. The website will allow the public to see the NABA Butterfly Monitoring Program data, including data from the 4th of July, 1st of July and 16th of September counts, displayed as maps and graphs. One can learn about the abundance of butterfly species and how they vary from year to year. The web pages will also include photos and information about all North American butterflies.

April 4, 2018: Sex,

The National Butterfly Center, in Mission, Texas, serves as the backdrop for a portion of this insightful documentary of wild butterflies, filmed by Peabody Award-winning cinematographer Ann Johnson Prum, who recently won an Emmy for Best Cinematography in Documentary for her production of Super Hummingbirds, also for PBS’ NATURE.

We were privileged and honored to host Prum last fall. The film promises to be a powerful and intriguing examination of the biology and behavior of butterflies that few have ever seen!

Please smile if you use Amazon to purchase anything! If you do, Amazon will donate a portion of the purchase price, at no cost to you, to NABA. Simply go to smile.amazon.com and follow instructions, choosing North American Butterfly Association as your charity.

You can now follow NABA activities on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.

Those of you who generously contribute donations to NABA and work at a large corporation may be able to double your contribution. Many corporations have matching gift programs. Check with your human resource or public relations dept.

The 12th NABA Photography Contest will be held in 2018. The winner will receive $300 and the 1st runner-up will receive $100. Winning entries will be published in the Fall 2014 issue of American Butterflies. Photographs of adults must be of free-flying, unrestrained butterflies taken in the field (not in a butterfly zoo), in Canada, the United States, or Mexico.

Photographs of immatures must be of eggs, caterpillars or chysalises taken in the field, or at a location (e.g., one’s house or laboratory) within 20 miles of where the eggs or caterpillars were obtained. Submissions, which must be received by June 6, 2016, should be in the form of digital images, sent as high resolution jpeg files on a CD, DVD or flash drive. Please include the photographer’s name in the file name. Files sent via email will not be considered. Please limit your submissions to three images (only the first three images received, per entrant, will be considered).

Entries must be accompanied by a signed statement giving NABA the right to copy and publish the photographs, both in print and digital form, and vouching that the photographs, if taken of adults, were taken in the field, of free-flying, unmanipulated butterflies. If of immatures, the photographer’s statement must vouch that the immatures were either photographed in the wild; or within 20 miles of where found and if removed from the wild that they were reared through to adults (or attempted to rear through to adults) and released where they were found.

Please include your last name in the digital file name and please include detailed information about when and where the photographs were taken, as well as camera, lens, flash, film, and setting information — to the extent known. Please include a telephone number and an email address where you can be reached.

Send your entries to: NABA Photo Contest, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960.