American Butterflies

Volume 25: Number 1

Volume 25: Number 1

The Butterfly Habitat Network

NABA continues to work on laying the groundwork for its Butterfly Habitat Network. In southern Florida we have initiated ambitious plans to save Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreaks (much more detail about this in the next issue). In New Jersey, we are exploring the possibility of purchasing, or managing for its rare butterflies, Klots’ Bog in Lakehurst. In the upper Midwest, we are actively looking for land that would be appropriate to purchase. In southern California, we are working with others to determine what steps can be taken to save Hermes Coppers from extinction. And, in the East, we are working with the USFWS to determine the status and needs of Frosted Elfins.

First offered in connection with the Memorial Day and Victoria Day Counts, NABA is extending it’s offer of a free, trial membership to people who participate in the NABA Butterfly Count Program who have not previously been NABA members. The free, trial membership includes access to digital versions of NABA publications. So, invite your friends, family and neighbors to participate in the Counts, helping to monitor and conserve butterflies throughout North America — they will be rewarded with a free, trial membership.

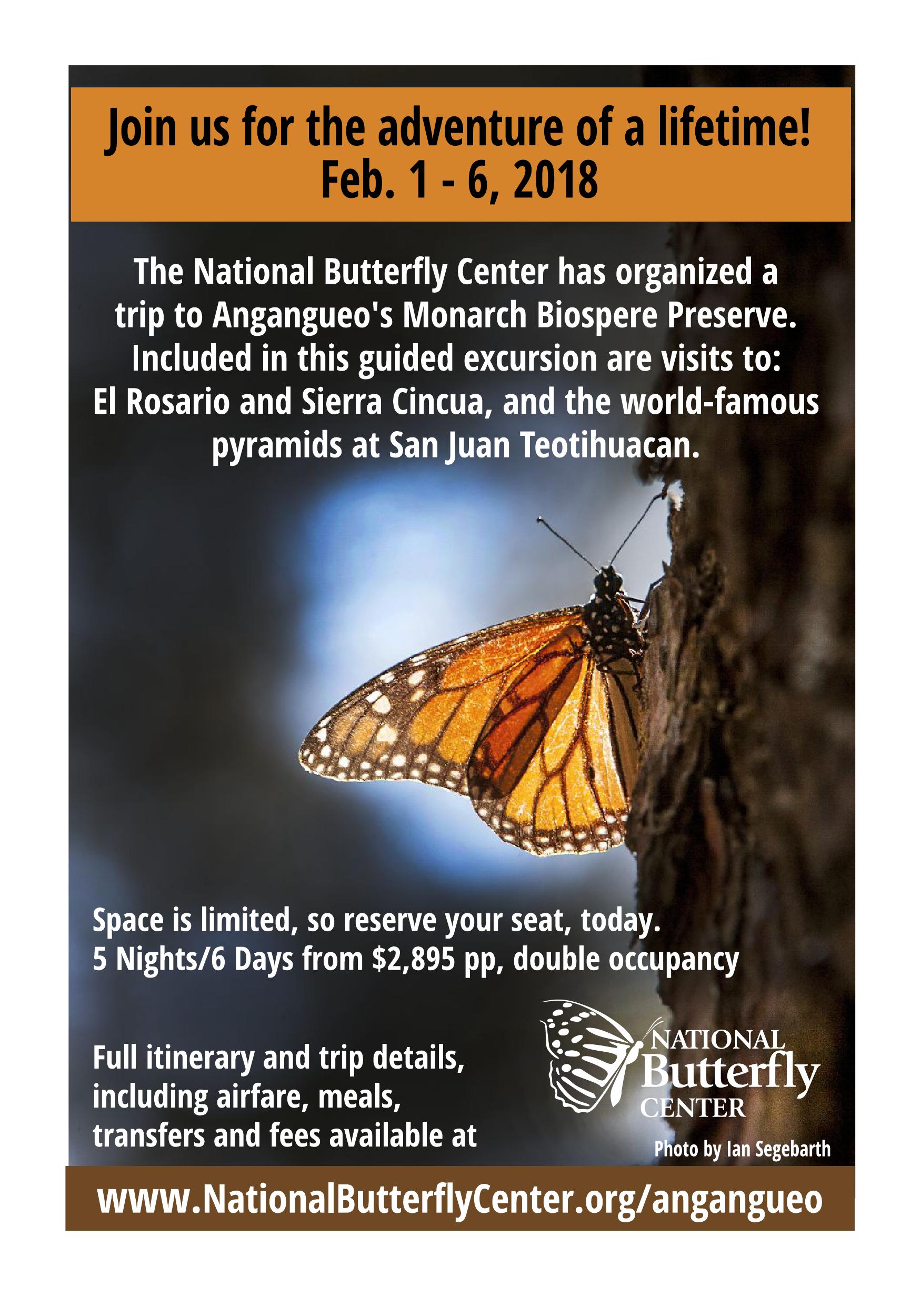

In February, 2018, NABA is offering, for the first time, a trip of a lifetime to see and learn about the spectacular Monarch overwintering sites in the mountains of central Mexico. For more information, see page 35 of this issue.

This year’s Texas Butterfly Festival will be held Nov. 4 - 7. Don’t miss the sensational butterflies, the amazing food, or camaraderie and good times! See the back cover of this issue for more information.

The thirteenth NABA Biennial Members Meeting is tentatively planned to be held in mid September, 2018 in Tallahassee, Florida. Don’t miss this great opportunity to see butterflies you may never have seen before, including Yehl Skipper, Berry’s Skipper and Dotted Skipper, along with thousands of individual butterflies, including many swallowtails, and to connect with ardent butterfliers from throughout the country.

You can now follow NABA activities on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest

Please smile if you use Amazon to purchase anything! If you do, Amazon will donate a portion of the purchase price, at no cost to you, to NABA. Simply go to smile.amazon.com and follow instructions, choosing North American Butterfly Association as your charity.

NABA is thrilled to announce that we will soon be making available to the public new pages, at www. webutterfly.org. The website will allow the public to see the NABA Butterfly Monitoring Program data, including data from the 4th of July, 1st of July and 16th of September counts, displayed as maps and graphs. One can learn about the abundance of butterfly species and how they vary from year to year. The web pages will also include photos and information about all North American butterflies.

Continued on inside back cover

Cover photos, of a luna moth was taken on April 16, 2012 in Sussex Co., NJ by Wade Wander. Recent research has shown that the long, twisted tails of luna moths confuse the echolocation signals of bats (the primary predator of adults), thus enabling some individuals to escape predation. Upon learning this, Wade Wander determined to create his own long, twisted tale. See the article about mothing on page 22.

The North American Butterfly Association, Inc. (NABA), a non-profit organization, was formed to promote public enjoyment and conservation of butterflies. Membership in NABA is open to all those who share our purpose.

President: Jeffrey Glassberg Vice-president:

James Springer Secrty./Treasurer

Jane V. Scott

Directors:

Jeffrey Glassberg

Fred Heath

Yvonne Homeyer

Ann James

Dennis Olle

Robert Robbins

Jane V. Scott

James Springer

Patricia Sutton

Scientific Advisory Board

Nat Holland

Naomi Pierce

Robert Robbins

Ron Rutowski

John Shuey

Ernest Williams

Volume 25: Number 1 Spring 2017

Inside Front Cover NABA News and Notes

2 Planet Change by Jeffrey Glassberg

4 Go Get Set On Your Marks: Satyrium Hairstreaks Part 2, the West by Jeffrey Glassberg

22 Daggers and Darts and Quakers too — My Passion for Moths; or, How A Butterfly Enthusiast Came to the Light by Wade Wander

32 You Are What You Eat 33 Pipevine Swallowtail on Woolly Pipevine in TX, by Don Dubois

36 We Are NABA: Mary Lynn Delfino interview by Mike Cerbone

40 White-striped Therra (Vacerra caniola): First Report from Mexico by Jeffrey Glassberg

42 Hot Seens by Mike Reese

48 Contributors

Inside Back Cover Readers Write

American Butterflies (ISSN 1087-450X) is published quarterly by the North American Butterfly Association, Inc. (NABA), 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; tel. 973285-0907; fax 973-285-0936; web site, www.naba.org. Copyright © 2017 by North American Butterfly Association, Inc. All rights reserved. The statements of contributors do not necessarily represent the views or beliefs of NABA and NABA does not warrant or endorse products or services of advertisers.

Editor, Jeffrey Glassberg

Editorial Assistance, Jane V. Scott, Matthew Scott and Sharon Wander

Please send address changes (allow 6-8 weeks for correction) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; or email to naba@naba.org

There are different opinions about how best to respond to the imminent destruction of the planet Earth. Some people, such as Elon Musk and Richard Branson want to fly to Mars so that they can actualize the science-fiction fantasies of their youths and encourage the human race to continue breeding at its current prodigious rate. While the mysterious red planet beckons to many, I remain fond of the grounded Earth.

Although some might put down my fondness for the current planet as an all-toohuman need to continue to want our world to be the same as it was when we were children, I can’t help thinking that perhaps this relationship with the Earth is somehow different, an evolutionary green bond of sorts, that connects us to the life around us.

All around, every day, I see calls to help the planet, by doing something about the changing climate that is affecting all biological organisms, including human beings. Let’s put a tax on carbon emissions, people say; let’s reduce our carbon “footprint”; let’s be more careful and efficient in our use of energy and food resources.

And, anyone who pays attention to butterflies knows that climate change is a reality, because the phenology of butterfly flight times and the ranges of warm area butterflies has rapidly changed over the past thirty years, as documented in NABA Butterfly Counts.

However, my belief is that while climate change is a crisis, all of the focus on it misses the more than 7 billion gorillas in the room — the exploding human population. You can play the recycle, greater efficiency game for a while, getting people to drink recycled human urine, a la Dune, to conserve water, for example, but even with the decreased quality of life that these greater efficiencies demand,

in the end there will always be too many people for the planet to support.

Each human being needs space to live, food to eat and water to drink. Some people believe that humans, being creative, will figure out ways to stuff ever more people into smaller spaces (perhaps giving them constant medications to make their lives tolerable); to manufacture human “food” from replenishable, non-organismal sources (yum); and to find other sources of water, such as the aforementioned urine or desalting sea water. However, each of these developments, even if actualization is possible, would only delay the inevitable. And, what sane person would jump off of a cliff thinking “no worries, I’ll invent a parachute on my way down.”

All of this is to say that the real threat to butterflies, all of the other animals and plants on the planet, and to human beings as well, is the continued growth of the human population. Rather than focusing on climate change, we need to find ways to slow, and reverse, the growth of the human population. Of course this will be extremely difficult, and painful.

Having spent hundreds of years fostering an economic Ponzi scheme — an economy that only works when we continually recruit new people into the system — we will need to find ways to deal with the daunting economics of declining growth.

If you are one of the Earth guys who gets queasy about Mars (think Geena Davis and Jeff Goldblum), and if you care about butterflies and the future of the planet, let’s start spreading the word about the real cause of our problems.

Please photocopy this membership application form and pass it along to friends and acquaintances who might be interested in NABA

Yes! I want to join NABA, the North American Butterfly Association, and receive American Butterflies and The Butterfly Gardener and/or contribute to building the premier butterfly garden in the world, the National Butterfly Center. The Center, located on approximately 100 acres of land fronting the Rio Grande River in Mission, Texas uses native trees, shrubs and wildflowers to create a spectacular natural butterfly garden that importantly benefits butterflies, an endangered ecosystem and the people of the Rio Grande Valley.

Name:

Address:

Email (only used for NABA business):______________________ Tel.:______________________ Special Interests (circle): Listing, Gardening, Observation, Photography, Conservation, Other

Tax-deductible dues enclosed (circle): Regular $35 ($70 outside U.S., Canada or Mexico), Family $45 ($90 outside North Am.). Special sponsorship levels: Copper $55; Skipper $100; Admiral $250; Monarch $1000. Institution/Library subscription to all annual publications $60 ($100 outside U.S., Canada or Mexico). Special tax-deductible contributions to NABA (please circle): $125, $200, $1000, $5000. Mail checks (in U.S. dollars) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960

American Butterflies welcomes the unsolicited submission of articles to: Editor, American Butterflies, NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960. We will reply to your submission only if accepted and we will be unable to return any unsolicited articles, photographs, artwork, or other material, so please do not send materials that you would want returned. Articles may be submitted in any form, but those on disks in Microsoft word are preferred. For the type of articles, including length and style, that we publish, refer to issues of American Butterflies.

If you have questions about missing magazines, membership expiration date, change of address, etc., please write to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960 or email to naba@naba.org.

American Butterflies welcomes advertising. Rates are the same for all advertisers, including NABA members, officers and directors. For more information, please write us at: American Butterflies, 4 Delaware Road, Morristown, NJ 07960, or telephone, 973-285-0907, or fax 973-285-0936 for current rates and closing dates.

Occasionally, members send membership dues twice. Our policy in such cases, unless instructed differently, is to extend membership for an additional year.

NABA sometimes exchanges or sells its membership list to like-minded organizations that supply services or products that might be of interest to members. If you would like your name deleted from membership lists we supply others, please write and so inform:

NABA Membership Services, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960

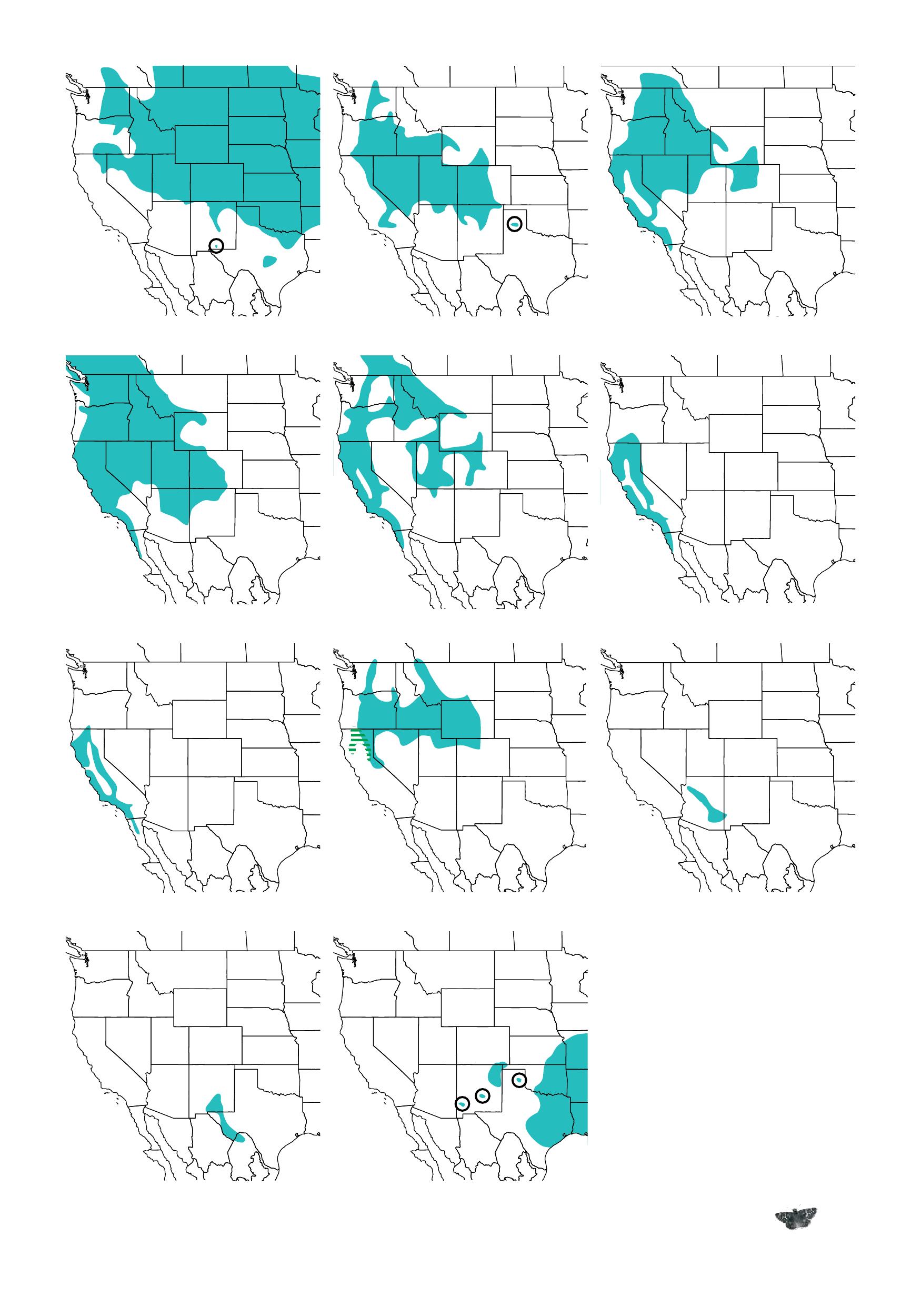

Page 5: The eleven species of Satyrium hairstreaks in the West*.

1. Coral Hairstreak.

July 16, 2000. Baker Creek, Great Basin NP, White Pine Co., NV.

by Jeffrey Glassberg

2. Behr’s Hairstreak. June 29, 2015. East of Fandango Pass, Modoc Co., CA.

3. California Hairstreak. June 22, 2014. Near Sattley, Sierra Co., CA.

4. Sylvan Hairstreak. Aug. 6, 1999. Bondurant, Sublette Co., WY

5. Hedgerow Hairstreak.

July 1, 2015. Above Gumboot Lake, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Siskiyou Co., CA

6. Mountain Mahogany Hairstreak. July 1, 2015. Above Gumboot Lake, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Siskiyou Co., CA

7. Gold-hunter’s Hairstreak. June 1, 1987. San Gabriel Mtns., Los Angeles Co., CA.

8. Sooty Hairstreak. July 1, 2015. Above Gumboot Lake, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Siskiyou Co., CA.

9. Sooty Hairstreak. July 17, 2002. Three Creek Meadow, Deschutes Co., OR.

10. Ilavia Hairstreak. May 14, 2016. Mt. Ord, Maricopa Co., AZ.

11. Poling’s Hairstreak. May 28, 1999. McKittrick Canyon Guadalupe Mountains NP, TX.

12. Oak Hairstreak. April 30, 2012. Pecan Park Preserve, Edwards Co., TX.

*The western ranges of Banded, Striped and Acadian Hairstreaks are limited. These species were treated in Part 1 of this article.

Coral Hairstreak

Treated in Part 1 of this article (Spring 2016), Coral Hairstreaks wear much the same coralstudded garb in the West as they do in the East. Unmistakable!

13. July 30, 2012. Kintla Lake, Glacier NP, MT.

14. July 15, 2010. Capulin Volcano National Monument, Union Co., NM.

Behr’s Hairstreak

This distinctive Satyrium hairstreak is usually gray-toned, but some individuals can be brown (photo 16). The thick, black postmedian spots are more angular than on other Satyrium hairstreaks. Especially distinctive are the two contiguous spots that look (sort of) like black eyes with white eyebrows above them [A] Above, Behr’s Hairstreaks are bright orange. This can be seen when they saw their HWs or when they fly [B] (photos 16 and 20).

Although there are a number of named subspecies, most variation is individual and, without knowing where an individual had been found, one would be hard pressed to assign it to a subspecies.

While Behr’s Hairstreaks are not likely to be confused with other Satyium hairstreaks, they can be confused with Mariposa Coppers. Mariposa Coppers (see photo 19) have a checked FW fringe, black spots in the FW cell and HW black basal spots that Behr’s Hairstreaks lack.

15. June 29, 2015. East of Fandango Pass, Modoc Co., CA.

16. July 16, 2000. Great Basin National Park, White Pine Co., NV.

17. July 19, 2002. West of Sisters, Deschutes Co., OR.

18. July 13, 1992. Lookout Mountain, Golden, Jefferson Co., CO.

19. July 23, 2007. West Thumb Geyser Basin, Yellowstone National Park, Teton Co., WY.

20. June 24, 2016. Highway 167, east of Highway 395, Mono Co, CA.

A trio of Satyrium hairstreaks — California, Sylvan and Acadian — are distinctively similar, sporting a postmedian band of solid black spots. The only other Satyrium hairstreak with this feature is Coral, which is distinctive in its own right (see page 6).

Before we discuss California and Sylvan Hairstreaks, let’s talk about Acadian Hairstreaks, treated in Part 1 of this article.

Acadian Hairstreaks are eastern/northern, hairstreaks that range west into Montana, Wyoming and Colorado. Exactly how far west they roam is uncertain, because although, according to Bob Robbins, curator of Lepidoptera at the USNM, female genitalic morphology distinguishes the two species, Acadian Hairstreaks are essentially indistinguishable from California Hairstreaks by wing pattern. The HW cell-end bar of Acadians is usually darker centered than on Californias [C], but there is much individual variation. And, although almost all Californias have a FW pm spot [D] that is closer to the submarginal spot [E] than do Acadians, some individuals fall into a gray zone.

Acadian Hairstreaks use willows as caterpillar foodplants, while California Hairstreaks feed mainly on oaks, but also on a variety of shrubs, such as Ceonothus and Mountain Mahogany. So, for now, to distinguish the two, go with geography or, at the east edge of the Rockies in Montana, Wyoming and Colorado, go with association with a particular caterpillar foodplant.

Throughout much of the West, California Hairstreaks (photos 22-27) can be (and are) confused with very similar, and very closelyrelated, Sylvan Hairstreaks which — surprise! — feed on willows.

In general, California Hairstreaks have more submarginal orange, with spots usually going up most, if not all, of the HW [F] and, to a lesser extant, along the FW as well. And, in general, California Hairstreaks are darker than are Sylvan Hairstreaks and fly earlier in the season. However, there are individuals who defy classification (see photos 26, 28-30). See page 10 for more on Sylvan Hairstreak.

21. July 20, 2014. Pondicherry NWR, Coos Co., NH.

22. June 22, 2014. Near Sattley, Sierra Co., CA.

23. July 13, 2000. Skyline Drive, Bountiful, Davis Co., UT

24. June 25, 2010. Hat Creek, Shasta Co., CA.

25. July 7, 2014. Below Mount Baldy, Missoula Co., MT.

26. June 29 2015. East of Fandango Pass, Modoc Co, CA.

27. June 25, 1988. Rock Creek Canyon, El Paso Co., CO.

In general, female Satyrium hairstreaks have more rounded FW apexes and longer tails than do males. The males of most species have a small patch of special sex scales on the upperside of the FW cell.

The ideal Sylvan Hairstreak has no orange scales over the HW soft blue outer angle spot; little, if any, submarginal orange spots, other than on either side of the HW blue outer angle spot [G] (and a little orange, one spot up [H]); pale gray ground color; faint cell-end bars [I]; and eats only willows.

Of course, your ideal man might have a finely chiseled body, a docile demeanor and just enough intelligence to run the lawn mower, but that doesn’t mean that most specimens meet your ideal!

As far as I know, there are no reported genitalic differences between California and Sylvan Hairstreaks. So, what about those nonidealized Sylvan Hairstreaks. Here’s what Paul Ehrlich has to say in 1961 in How to Know the Butterflies “I am reasonably certain of the separation of these two species only in S. California.” Not much has changed.

Some individuals, and populations, seem to provide a lot to be uncertain about. If you are certain of the identity of the individuals in photos 28, 29 and 30, then you may know something that I don’t — please let me know! To my eye, they look intermediate.

Some Sylvan Hairstreak populations lack tails (see photo 31) and these populations are often treated as dryope which most place as a subspecies of Sylvan but some treat as a full species. However, the range of tailless populations is disjunct — from Lake County south to the Los Angeles area in the coastal ranges, but also from the Sierras and east of the Sierras to northeastern Nevada. It seems likely that populations can be tailed or tailless, in which case the tailless populations wouldn’t constitute a subspecies.

28. July 19, 2015. Nelson, British Columbia, Canada.

29. June 12, 1997. Middletown, Lake Co., CA.

30. July 30, 2014. Willow Flats, Grand Teton National Park, WY.

31. May 27, 2014. Sunol Regional Wilderness, Alameda Co., CA.

32. Aug. 5, 1997. Kingston Canyon, Lander Co., NV.

33. July 19, 1998. Black Canyon, Okanogan Co., WA

34. Aug. 6, 1999. Bondurant, Sublette Co., WY.

35. June 26, 2008. North of Kernville, Tulare Co., CA.

Quite variable, both between populations and, often, within a population, Hedgerows Hairstreaks are difficult to characterize, but can usually be readily recognized when seen.

Above, the copper colored wings are usually distinctive [J] (see photos 36 and 42) and the color can usually be seen when the butterfly flies. Most individuals have prominent, pale, cell-end bars on the undersides [K], but many (see photos 37 and 43) do not. A number of populations have the areas outside the postmedian line somewhat paler than the areas inside the postmedian line [L], and this is taken to an extreme in San Luis Obispo County, CA (photo 36).

Perhaps the best way to characterize this species is by what it lacks — orange scales on its underside, especially missing over the most prominent black spot [M] (photo 39). The only other Satyrium species without orange here are Sooty Hairstreak and the occasional Mountain Mahogany Hairstreak. Sooty Hairstreaks have postmedian spots, rather than a postmedian line; and Mountain Mahogany Hairstreaks have “frosting” near the HW apex.

Hedgerow Hairstreak can be very similar to some Gold-hunter’s Hairstreaks — see that species, pages 14-15.

36. June 16, 2009. Los Osos, San Luis Obispo Co., CA.

37. July 26, 2013. Niagara Creek Campground, Tuolomne Co., CA.

38. June 19, 1998. Ridge Route, Los Angeles Co, CA.

39. July 12, 1992. Lookout Mountain, Jefferson Co., CO.

40. July 1, 2015. Above Gumboot Lake, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Siskiyou Co., CA.

41. July 19, 1998. Black Canyon, south of Methow, Okanogan Co., WA.

42. June 12, 2005. Otay Mountain, San Diego Co., CA.

43. Aug. 10, 2011. Rocky Point Trail, Lake McDonald, Glacier National Park, Flathead Co., MT.

Feeding on a variety of Ceonothuses, this species can be found in many habitats in addition to its usual chaparral habitat.

Los Angeles Co., CA

San Diego Co., CA

Jackson Co., OR San Diego Co., CA

Most individuals of this uncommon to rare chaparral hairstreak have a warm yellow-brown ground. Unlike Hedgerow Hairstreaks, Goldhunter’s Hairstreaks have an orange cap on the black spot just above the HW outer angle blue spot [N]. Mountain Mahogany Hairstreaks (next page) often have a very faint yellow cap, but they, unlike Gold-hunter’s, have white “frosting outside the HW postmedian line. Male Goldhunter’s (photos 44, 46) usually have more prominent postmedian bands than do females (photos 45, 47).

44. June 1, 1987. San Gabriel Mountains, Los Angeles Co., CA.

45. June 17, 1998. Descanso, San Diego Co., CA.

46. May 29, 2015. Kinney Creek, Applegate River Valley, Jackson Co., OR.

47. June 2, 2012. Cleveland National Forest near Descanso, San Diego Co., CA.

Another chaparral hairstreak. This one is uncommon, but more frequently encountered than are Gold-hunter’s Hairstreaks. Males (See photos 48 and 51) tend to be browner with very short tails, females grayer, often with normal tails (photo 49). All have whitish scales between the HW postmedian line and the HW apex [O], although, of course, worn individuals may not show this. There is usually a faint yellow cap over the black spot just above the HW outer angle blue spot. Unlike Hedgerow Hairstreaks, the topsides are dark brown, not copper-colored.

48. June 13, 2005. Barber Mountain, San Diego Co., CA.

49. June 21, 1997. Mines Rd., Alameda Co., CA.

50. May 26, 2013. San Marcos Pass, Santa Barbara Co., CA.

51. June 26, 2008. North of Kernville, Tulare Co., CA.

Most individuals of this local, but sometimes not uncommon, hairstreak have an ashy gray ground color, however, some populations have individuals shading to golden brown (photos 56, 58). There can be considerable intrapopulation variability (photos 53, 54).

Normally, both the FWs and HWs have black spots circled with white [P], although both the black spots and the white circles are sometimes faint and attenuated (photos 54, 56).

Among Satyrium hairstreaks, Sylvan and California Hairstreaks have the most similar wing patterns, also with postmedian black spots, however Sooty Hairstreak lack the HW blue, outer angle spot [G] that is prominent on those, and other species.

Although you are unlikely to confuse these butterflies with other hairstreak species, you might confuse them with Boisduval’s Blues. For example, the Park Co., WY individual illustrated in “A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America” is a Boisduval’s Blue, not a Sooty Hairstreak. As you can see in photo 52, Boisduval’s Blues also have postmedian black spots circled with white. However, unlike Sooty Hairstreaks, Boisduval’s Blues have black FW cell-end bars and usually have black HW basal spots.

A few years ago, some people decided that because some populations of Sooty Hairstreak

52. June 24, 2015. Mount Ashland, Jackson Co., OR.

53. June 27, 2015. Surprise Valley, Modoc Co., CA.

54. June 27, 2015. Surprise Valley, Modoc Co., CA.

55. July 17, 2002. Three Creek Meadow, Deschutes Co., OR.

56. July 1, 2015. Above Gumboot Lake, Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Siskiyou Co., CA.

57. July 15, 2016. Mount Ashland, Jackson Co., OR.

58. July 18, 2012. Rock Creek, near Red Lodge, Carbon Co., MT.

59. July 22, 2006. Near Teton Pass, Teton Co., WY.

had male scent pads (individuals shown in photos 56 and 57; scent pads not visible) while the rest did not, Sooty Hairstreak consisted of two species. NABA, waiting for more evidence, did not adopt this change. Recently, it has been shown that where the populations with and without scent pads meet, they seem to freely interbreed. This, of course, suggests that they may best be treated as one species. It also suggests that those who immediately latch onto every publication that argues for a change in species status (or, even worse, genus status), are making a mistake.

In the United States, Poling’s Hairstreaks have a limited range, from south-central New Mexico through west Texas into the Mexican state of Chihuahua. As you can see in photos 61 and 62, milkweeds are important to more than Monarchs.

Poling’s Hairstreaks closely resemble, and are very closely-related to, Ilavia (next page) and Oak Hairstreaks (page 20). All three feed on oaks, as do a number of other Satyrium hairstreak.

Poling’s Hairstreaks are plain brown on their topsides while Ilavia and Oak Hairstreaks have bright orange patches, but the absence of any orange is difficult to conclusively determine in the field.

Instead, first determine where you are, that along will give you a strong clue. Then, look at the FW submargin. Poling’s and Ilavia Hairstreaks lack a submarginal line [Q], while Oak Hairstreaks have one [R] (page 20).

Next, look at the FW apex. Poling’s have a white fringe here [S] while Ilavia Hairstreaks have a brown fringe. Lastly, Poling’s usually have more prominent HW submarginal spots that reach closer to the HW apex [T] than do Ilavia Hairstreaks.

See Ilavia Hairstreak (next page) for separation of Poling’s, Ilavia and Oak

60. June 6, 2012. Organ Mountains, Dona Ana Co., NM.

61. May 28, 1999. McKittrick Canyon, Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Culberson Co., TX.

62. May 6, 2005. Green Gulch, Big Bend National Park, Brewster Co., TX.

from other Satyrium hairstreaks.

Other than Hedgerow and Mountain Mahogany Hairstreaks, no other Satyrium hairstreaks have a HW postmedian line that is a simple line, without wide patches or spots. And, Hedgerow and Mountain Mahogany Hairstreak are not found in areas where Poling’s, Ilavia or Oak Hairstreak are normally found.

For example, Ilavia Hairstreaks are, so far as known, found only in Arizona (OK, so they do reach New Mexico, but just barely).

Ilavia Hairstreaks closely resemble, Poling’s and Oak Hairstreaks (page 20). In fact, until not too long ago, most people treated Ilavia Hairstreaks as subspecies of Oak Hairstreaks. And, like Oak Hairstreak, but unlike Poling’s Hairstreaks, Ilavia Hairstreaks have bright orange patches on their uppersides.

63. May 14, 2016. Mount Ord, Maricopa Co., AZ.

64. May 24, 1999. Globe, Gila Co., AZ.

65. May 21, 2011. Just west of the Pinal County-Gila County line, Pinal Co., AZ.

Below, they differ from Oak Hairstreaks in that they lack a FW submarginal line [Q] and from Poling’s Hairstreak by having a brown or gray FW apical fringe [S] and by lacking HW submarginal spots near the HW apex [T]

Because of its limited range, limited flighttime and limited abundance, this may be one the least frequently seen butterfly species of North America.

Oak Hairstreaks are few and far between in the true West. Their vaguely continuous range breaks up west of the Edwards’ Plateau of Texas (photo 66), with seemingly disjunct populations in the Texas panhandle, northeastern New Mexico (photo 67), south-central New Mexico (photo 68) and southwestern New Mexico. Populations also are found south in Mexico, at least to the state of Oaxaca.

Oak Hairstreaks, very close cousins of Poling’s and Ilavia Hairstreaks, can be distinguished from both of those species by the presence of a marked submarginal line on the underside of the FW [R] and by the more

66. April 30, 2012. Pecan Park Preserve, Edwards Co., TX.

67. June 12, 1993. Mesteño Canyon, southwest of Mills, Harding Co., NM.

68. June 19, 2003. Seep Canyon, Sacramento Mountains, Otero Co., NM.

69. May 24, 2004. Etla-Guacamayas road, Oaxaca, Mexico.

70. May 28, 2010. Etla-Guacamayas road, Oaxaca, Mexico.

extensive HW submarginal orange spots [F]

Coral Hairstreak

Behr’s Hairstreak

California Hairstreak

Sylvan Hairstreak

Hedgerow Hairstreak

Mountain Mahogany Hairstreak

Gold-hunter’s Hairstreak Sooty Hairstreak

Poling’s Hairstreak Oak Hairstreak

Ilavia Hairstreak

Turquoise color indicates that there is one brood in this area.

On the Sooty Hairstreak map, the horizontal green/white bars show range of the S. fulginosa fulginosa subspecies.

text

by Wade Wander

Above: Lemon Plagodis. What’s not to like about the delicious color combination of lemon and raspberry? May 15, 2015. Sussex Co., NJ.

Left: Smaller Parasa. Only a half-inch long, this is one of our more colorful slug moths. Like many moths it rests with its wings folded over its body like a tent. The swept-back antenna is a clue that the head end is at the left. July 3, 2016. Sussex Co., NJ.

Moth mania is sweeping the country like newly emerged Orange Sulphurs across a field of Alfalfa. First held in 2012, National Moth Week registered more than 400 events in all 50 states and in more than 40 countries within just four years. This adds up to more than 1000 “moth nights” — without including any of the many un-registered moth activities. So what’s all the hubbub about?

What first appealed to me about moths was their extraordinary species diversity. More than 11,000 species are found in North America north of Mexico (compared to about 725 species of butterflies — a ratio of about 15 to 1). My own modest moth-observation efforts, that began in 2001, have yielded more

than 1050 (not a typo) species on my 3 acres in Sussex County, NJ. This represents about 9.5% of the species found in North America. Incredible, you say? Not really. Consider that since 2001 my wife and I have recorded 75 species of butterflies in our yard, which represents about 9.7% of the total number of North American species. And amazingly, we added more than 50 new species of moths in 2016. So, after 16 years I still have a reasonable expectation of finding a new species of moth or other insect for my yard list every night. Excitement for a “moth-er” — or any naturalist — is in not knowing what you might find.

“Mothing”can be ridiculously easy.

Above: A small sample of moths and other insects at a self-ballasted mercury vapor light that the author just screws into the outdoor light fixture on his deck. The greatest numbers of moths generally show up on moonless, calm, warm, and humid nights. May 31, 2011. Sussex Co., NJ.

Opposite page top: Virgin Tiger Moth. One of our largest tiger moths and, without a doubt, one of the most spectacular. July 19, 2016. Sussex Co., NJ.

Opposite page bottom: Io Moth. Both sexes of this Giant Silkworm Moth are marked with large hindwing eyespots that, when flashed open, are thought to frighten predators. The bright yellow forewings identify this as a male. June 18, 2014. Sussex Co., NJ.

Tufted Bird-dropping Moth. As the name suggests, adults look like bird droppings, which (as with some butterfly caterpillars) reduces predation by birds. The brilliant iridescence indicates that this individual has just emerged from its cocoon. June 7, 2015. Sussex Co., NJ.

Take my set-up, for example. Just a mercury vapor lamp, a black light, and a few standard incandescent and fluorescent lights screwed into the ordinary outdoor light fixtures on my house. No white sheets, no baiting with stale beer and rotten bananas, no pheromones. Just flipping on a few light switches and checking every 30 minutes or so to see what has shown up. Butterflying during the day and mothing at night — what could be better! And just about anyone who lives in a house can do this — even in suburbia. Of course it really helps to have some native vegetation on or near your property. The more diverse the host plants (both woody and herbaceous species) that are available in your area, the more moths you will attract to your lights. So, let those weeds in your lawn grow (even alien species like Common Dandelion are host plants for moths

and provide nectar for many other insects), and please don’t cut down those native saplings and shrubs, even those that are a bit scraggly.

Second I was surprised to find that, contrary to popular belief, not all moths are drab and somber-colored creatures of the night. To be sure, some are difficult to get worked up about, but most species are beautiful in subtle ways or are downright flashy and gaudy. Even tiny micromoths just a few millimeters long can be amazingly attractive — they just require a closer look. And the variation in color and pattern between and even within sexes of many species adds to the already extraordinary phenotypic diversity. And as any gardener can tell you, many species are active during daylight hours, so you can enjoy a surprising number of moths

Cherry Scallopshell. This species may look familiar to older generations of people who may remember TV test patterns. May 24, 2015. Sussex Co., NJ

without even losing any sleep.

And finally, who can resist those wildly imaginative moth names? Many are usefully descriptive and significant but still manage a certain panache, like the Saffron-headed Monopis. But many other names are lyrical, almost poetic, like the Little Cloud Ancylis and the Featherduster Agonopterix. And isn’t the Spun Glass Slug Moth a more evocative name than, say, the Fiberglass Moth? Some moths have two common names — one for the caterpillar and one for the adult. The familiar red-and-black–banded hairy caterpillar we see humping its way across roads — that we have known since childhood as the Woolly Bear — metamorphoses into the Isabella Tiger Moth. And vegetable gardeners are certainly familiar with Tomato Hornworm caterpillars, which later will fly as Carolina or Five-spotted

Sphinx moths.

But other moth names can best be described as whimsical. And there are lots of them, so let’s get started.

There is a group of moths called Quakers (yes, Quakers, as most are modestly dressed in gray) that includes species named subdued, cynical, and intractable. (I remember telling a fellow moth-er that one night my lights were overrun with intractable Quakers. I often wonder how nearby folks interpreted this statement.) Apameas can be Doubtful, Ignorant, or Downright Impulsive. Some Daggers have upbeat names that range from Pleasant to Delightful and all the way to Splendid, while others are curiously named Hesitant, Retarded, Afflicted, Fragile, and most alarming of all, Funerary. Agreeable and Dubious Tiger Moths look alike so I am

Giant Leopard Moth. One of the Tiger Moths, this one is named Leopard because it is spotted rather than striped. The large black-and-red caterpillars are frequently seen. June 22, 2011. Sussex Co., NJ.

dubious about my identifications. The Major Sallow outranks (in attractiveness if nothing else) the Private Sallow. The mousy Dowdy Pinion and her bawdy sister the Wanton Pinion make an odd couple. Are the Brother and the Abrupt Brother estranged? The Friendly Probole is apparently easy to get along with whereas the Alien Probole needs a green card (despite its being native). Last but equally intriguing in the taxonomic chain is the clan of Darts, which boasts Slippery, Rascal, Subgothic (what, no Gothic?), Subterranean (?), Venerable, Voluble, Clandestine, and Attentive members. A motley clan, indeed! Want some more? How about the

Slowpoke, the Joker (does not look like the Batman nemesis), Disparaged Arches, Exasperating Platynota, Impudent Hulda (I kid you not), Deceptive Apotomis, Wretched Olethreutes, Derelict Eucosma, Likable Gretchena, Happy Pammene, Vagabond Crambus, Splendid Palpita (not in my view), Glorious Habrosyne (definitely), Renounced Hydriomena, Fervid Plagodis, Turbulent Phosphila, Confused Eusarca, and Morbid and Detracted owlets? And if there is anything worse than being the Frigid Owlet it’s being the Forgotten Frigid Owlet.

I could go on, so I will. I wonder what the Music-loving Moth thinks of the noodlings

Bicolored Pyrausta. The genus Pyrausta includes many colorful species but this is perhaps the flashiest. June 21, 2015. Sussex Co., NJ.

of the Slightly Musical Conehead (a species of katydid). I have a special fondness for the (no longer politically correct) Festive Midget. (Oh what joy to find a youth sports team called the Festive Midgets!) It’s hard to know what to make of the Ambiguous Moth but it seems a safe bet to give a wide berth to the Horrid Zale.

Had enough? No? Good — I’ve got more. The Adorable Brocade (not in my book), Shy Cosmet, the Herald (adults overwinter), Laugher, Honest Pero, Abstruse Looper, Deceptive Snout, the Bad-Wing and the HalfWing, Shimmering Adoxophyes, Shattered Ancylis, Oystershell Metrea, Pegasus Chalcoela, and the luminous Pale Beauty (think actress Cate Blanchett). Either the Oneeyed or the Small-eyed Sphinx may be king (or queen) in the land of the Blinded Sphinx (this all has to do with their eyespots). And finally some all-time favorites of mine — the Hieroglyphic Moth, the Goldenrod Stowaway Moth, and — superhero wannabes — the Cloaked and Green Marvels.

Quick quiz. Which one of the following three moths is real — the Shaggy-spotted Wockia, the Bigly Bombastic Bomolocha, or the Orange-tufted Narcissistic Moth? If you guessed the Wockia you are right, although you could be forgiven if you thought it was a little-known Star Wars character. The others are, well, fake moths.

And, of course, we cannot leave this subject without discussing the underwing moths in the genus Catocala. Carolus Linnaeus (the father of taxonomy) assigned scientific names to moths in this genus, as he did to so many species of fauna and flora — in most cases based on specimens collected by others. But what is so intriguing about the underwing group is that Linnaeus and later taxonomists followed two main themes in their scientific names (which have been translated to English in current field guides): female/ marriage, and bereavement. (I prefer to think this was done after swilling copious amounts of lager beer.) In the former category we have the Betrothed, the Bride, the Wife, the Old

Wife, the Girlfriend (worlds collide when the Girlfriend shows up with former or current Wives), the Mother, Connubial, Once-Married, Darling, Delilah, Sweetheart, Newlywed, and the Little Nymph. And let’s not forget the Old Maid. All of these species have hindwings that are brightly banded with pink, yellow, orange, or red. All the species saddled with the bereavement theme have black hindwings, and as might be expected have gloomy names such as Sad, Mourning, Widow, Tearful, Forsaken, Dejected and, my personal favorite, the Inconsolable Underwing. If I discover a new species of Catocala with brightly colored hindwings I propose to name it the Strumpet Underwing; and one with black hindwings the Dystopian Underwing.

Just reading all these fantastic names, how can you not want to learn a LOT more about these moths? So, I hope that this overview has whetted the appetites of at least some of you to expand your lepidopteran menu. Just as my good friend John Yrizzary, the great bird artist, aroused my interest with amazing tales of moths in his yard, I in turn have passed on the excitement of mothing to many others — some of whom now have become obsessed.

To get started, I recommend that you obtain a copy of the Peterson Field Guide to Moths by David Beadle and Seabrooke Leckie. Despite a number of errors, the color photos of living moths in this guide are very useful for beginners and even for more experienced moth-ers. Also, online resources are available such as the Moth Photographers Group (www.mothphotographersgroup. msstate.edu/). This website contains an exhaustive number of species and most of the color photos are of living specimens.

For you beginners, be sure to photograph every moth you see, as this is an excellent — and nonlethal — way to identify them. You can then, at your leisure, compare your photos to those shown in the field guide and on the Moth Photographers Group and Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA) websites, which also include national distribution maps. But do not expect to

identify every photograph to species because some genera require careful examination of genitalia (I am not kidding). You can also check out moth photos on my Flickr site, which is open to all viewers.

And, best of all, you don’t need expensive equipment. I photographed all of the insects in this article in my yard using a relatively inexpensive Canon PowerShot SX50HS camera. To photograph the smaller species I attach a Raynox Model M-150 macro-lens.

Almost all of my moth photos are taken in situ. I rarely move moths (although I might gently tweak a Catocala or sphinx moth to get it to show its hindwings), and I have never put any in the fridge to slow them down. Also, I usually turn my lights off by midnight, because moths (and other insects attracted to lights) have much more important things to do than stay plastered onto the sides of my house until dawn (when birds quickly learn to pick them off). I do miss some late nightflying species that way, but a smile crosses my face when I think of them out there in the dark making more moths. And keep good notes on species abundance. The longer you observe moths the more likely you will notice some population trends such as the decline in giant silkworm moths, sphinx moths, and underwing moths that I, and many others, have noted. This information may help scientists determine which species are declining. In New Jersey, the Endangered and Nongame Species Program is trying to evaluate moth populations, but it is a challenging task because data are very sparse. Citizen-scientists like many of you can make important contributions to fill such data gaps.

Finally, consider participating in one of the many “moth nights” that are springing up across the country. It’s a great activity for kids, who get a chance to see moths and lots of other cool insects (and to stay up late).

To learn more about National Moth Week and register for one or more of its numerous activities, just contact nationalmothweek.org. Happy mothing, and may the The Angel (look it up) be with you!

We have initiated a project to document the caterpillar foodplants of North American butterflies. For those who would like to participate in this photodocumentation, here are instructions:

Find an egg or a caterpillar (or a group of eggs or caterpillars) on a single plant in the “wild” (this includes gardens). The plant does not need to be native to the area — we want to document all plants used by North American butterflies.

Follow this particular egg or caterpillar (or group of eggs or caterpillars) through to adulthood, with the following documentation.

1. Photograph the actual individual plant on which the egg or caterpillar was found, showing any key features needed for the identification of the plant.

2. Photograph the egg or caterpillar.

3. Either leave the egg or caterpillar on the original plant, perhaps sleeving the plant

it is on with netting, allowing the caterpillar to develop in the wild, or remove the egg or caterpillar to your home and feed it only the same species of plant on which it was found.

4. Photograph later instars of the caterpillar.

5. Photograph the resulting chrysalis.

6. Photograph the adult after it emerges from the chrysalis.

7. If the egg or caterpillar was relocated for raising, release the adult back into the wild at the spot where you found it.

We would like to document each plant species used by each North American butterfly species, for each state or province.

In addition to appearing in American Butterflies, the results of this project will be posted to the NABA website. Please send any butterfly species/plant species/state or province trio that is not already posted to naba@naba. org.

Opposite page

Top left: The Woolly Pipevine plant that supported the growth of the Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars. March 31, 2005.

Top right: Pipevine Swallowtail eggs on the Woolly Pipevine. April 18, 2005.

Bottom left: Caterpillars on the Woolly Pipevine. April 27, 2013.

Bottom right: A chrysalis. May 2, 2013.

by Don Dubois

Woolly Pipevine (Aristolochia tomentosa) is the primary native caterpillar host plant for Pipevine Swallowtails in the Houston, Texas area. While it shows numerous blooms in March, very few if any fruits are generally found. Most of the fruits drop off after the bloom, apparently without being pollinated.

Over a seven year period I have found only one mature fruit on my largest vine. The vine is well behaved here and gradually increases in size over several years. New plants will sprout from the roots but it is not an aggressive spreader. In the wild, mature plants may reach 30 feet or more as they scale trees along sandy

river banks in forested areas.

On April 11, two small Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars were found feeding together on Woolly Pipevine leaves on a garden trellis and the leaves were netted to protect the caterpillars from predation. The eggs were not found before the caterpillars were located but a photo of pipevine swallowtail eggs on the same plant taken another time is included for completeness.

The caterpillars grew rapidly and the first one pupated on May 2. The second formed a chrysalis about a week later on May 8. By 11 AM on the morning of May 16, it was apparent that the first butterfly was about to emerge as the pattern of the butterfly started to show in the chrysalis. The first butterfly emerged shortly after 2 PM and by 3 PM the wings were expanded. The butterfly was allowed to harden its wings outside on a shrub. The second chrysalis had still not hatched as of July 1. The chrysalis was still viable and it appears likely that the second chrysalis is destined to be a fall emergence.

Above: Range of Pipevine Swallowtail. Orange indicates three broods. Purple indicates two broods. Turquoise indicates one brood. Cherry spots are locations where strays have occurred. (map from A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

adult emerged on May 16, 2013.

Above: The approximate range of Woolly Pipevine, based upon county occurrence data from the USDA. This might be a useful plant for your garden if you live within the range shown.

Cerbone. Where did you grow up? Did your childhood have an impact on your interest in nature? A common theme for a lot of the people I speak with is an early exposure to animals and insects.

Delfino. I was born and raised in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in an urban neighborhood where houses can be so close to each other that you can stand between them, stretch out your arms, and touch them. Learning about and being in nature was not part of my childhood experiences. Once in a while my dad would take us for a walk behind the local elementary school where there was a creek adjacent to an abandoned railroad tunnel and a short rough trail that connected to another part of the neighborhood, and that was really it in terms of nature.

Although surrounded by the beauty of the Endless Mountains and the Pocono Mountains, I was not intrigued by nature until I moved to Ohio for graduate school nearly ten years ago. As part of my graduate assistantship in retreats at the University of Dayton, I co-led women’s wilderness retreats to Red River Gorge in Kentucky with my colleague Allison, who was a budding birder. We would also take bike rides, and she would point out various birds, their calls, and their behavior. Of course, I teased her a bit, but I quickly found within myself a deep satisfaction in the beauty and wonder of nature.

Interview by Michael Cerbone

After graduate school, I moved to northeast Ohio, where a few years later, butterflies grabbed me after going on a guided hike with two naturalists from the Portage Park District. I had ridden my bike five miles to the trailhead on a hot August afternoon and went on this butterfly count in a tank top and shorts (with no bug spray). The more experienced counters puzzled over my attire as I was clearly unprepared; the bugs ate me alive!

Through cycling and hiking along the many paths of northeast Ohio, I have learned more about the native butterflies in this area. This summer, a friend got me connected to two weekly counts in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Although I was new to the group, I discovered I knew more than I thought. Plus, the retirees who primarily compose the group love my “young” eyes! Now I’ve got the binoculars, the camera, and the right clothes. Citizen science is fascinating new territory for me and very different from the work I do in my professional life.

Being in nature was not something that was part of my childhood experience; however, following baseball and collecting baseball cards was. I thoroughly enjoyed taking note of the teams’ uniforms and changes from year to year and could remember easily when something was amiss. To this day, I have a great fondness for colors, patterns, and logos and am proud to be a daily reader of Paul Lukas’

Uni-Watch blog and Twitter feed. Having a mind for this kind of minutiae is extremely helpful in identifying birds and butterflies. Now, if I could transfer that to plants...

Cerbone. What is your educational/ professional background?

Delfino. I have a BA in Communication Arts (2004) from Marywood University in Scranton, Pa. and a MA in Pastoral Ministry (2009) from the University of Dayton. I have spent all of my professional life in church ministry with youth and young adults. I currently serve as the pastoral associate for campus ministry at the University Parish Newman Center, a Roman Catholic parish which serves Kent State University.

Cerbone. Can you recommend any good spots for butterflying in your local area?

Delfino. Being somewhat new to butterflies, I sought out recommendations from my fellow butterfliers. Obviously, the

Cuyahoga Valley National Park where we do our counts has some great spots. Within the park, we count at Indigo Lake, Terra Vista Natural Study Area, and Pine Hollow. Outside the park, two recommended spots are Springfield Bog in Akron and Mentor Marsh in Mentor near Lake Erie.

Cerbone. As always, I have to ask: how would you say that being in the ministry is like butterflying?

Delfino. Wow! This is a fantastic question. As a campus minister, one of my primary roles is to be a witness to the transformation that is taking place in the lives of college students, spiritually, for sure, but also developmentally and emotionally. In many ways, it is akin to witnessing the life cycle of the butterfly, which reflects the central truth of the Christian tradition, the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. Being involved in butterflies helps me to cultivate a sense of mystery. Both ministry and butterflying require endless patience and an openness to wonder. A student may not be ready to open her wings to take on a new challenge or a new project even though I think she’s ready. How many times have I stood before a butterfly and quietly tried to coax it to do the same! “Open up, little one!” But when both the student and the butterfly eclose, I never tire of wonder and gratitude in those moments.

Finally, since I don’t work directly for the university, working with college students in ministry helps me to identify trends in higher education and with young adults in general, much like butterflies tell us something of what is happening in the environment.

Cerbone. We often find that younger people are a less represented demographic for NABA. What do you think is the silver bullet to changing that and getting youth more engaged with nature and conservancy?

Delfino. When I attended my first NABA meeting in Texas, it did not take long to notice the disparity in the demographics in the room. Young adults like myself have many competing interests, and though my generation possesses a great spirit of volunteerism and service, we are less likely to join membership organizations than our parents or grandparents. Commitment seems to be difficult for us.

Yet many of us are environmentallyconscious and want to do our part to be good stewards of the earth for the generations to come. I am not sure if I have a silver bullet, but a few things come to mind. First, never underestimate the power of personal invitation. That’s how I got involved in the butterfly counts in my area. It has changed my whole perspective on what it means to be involved in this pursuit.

Second, groups can highlight practices and promote events that the average person can do, such as incorporating native plants in your garden or taking a family-friendly guided hike. Many people feel overwhelmed by saving the earth, so why not put it in manageable terms. As Unitarian clergyman Edward Everett Hale wrote, “I am only one, but I am one. I can’t do everything, but I can do something.”

Finally, maintain vibrant social media accounts that include a healthy mix of stunning photography (we are a visual generation!), fun factoids, and upcoming events. It’s lovely to see flowers and butterflies, but I’d love to see some “real” people enjoying themselves! Maybe then the millennials can unplug from our Netflix and technology addictions and take a more active role in nature and then perhaps in conservancy and advocacy.

Cerbone. You mentioned participating in the Cuyahoga Valley butterfly count. Do you have any advice for first-timers attending their first count as an observer?

Delfino. Trust your instincts. You know more than you think you know. Take advantage of being in a community of learners. I have found that butterfly enthusiasts are a gentle and understanding lot who never tire of even the most basic questions. We each have something to teach each other. Most importantly, there is no test at the end! On a practical level, make sure to check in with the leader of the group about meeting place and time and any special instructions on clothing as some areas may be prone to biting and/or stinging insects or other obstacles.

Cerbone. You are very active in our online community; what would you like to see us focus on more in terms of content or postings on social media?

Delfino. Because I’m new, I love it all and feel the content is fairly diverse! I would love to see more short profiles of members as well as some more tools/resources for identification. I would also love to see more local chapters establish a presence on social media.

Anurag Agrawal

Cloth $29.95

“An unprecedented tour of the lives of these insects, based on cutting-edge research into their evolution.”

Carl Zimmer, coauthor of Evolution: Making Sense of Life

“Gorgeously written and wonderfully illustrated.”

Thomas D. Seeley, author of Honeybee Democracy

“The best book on monarch biology that I have ever read.”

Stephen B. Malcolm, Western Michigan University

by Jeffrey Glassberg

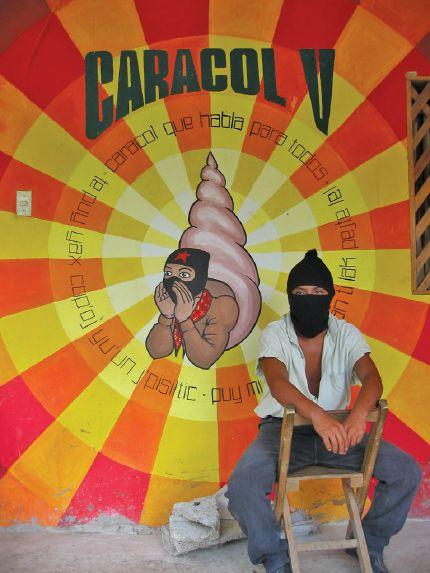

In August of 2014, a small group participated in a Sunstreak Tours trip to the Palenque area of the Mexican state of Chiapas.

Although butterflies are the overwhelming focus of these trips, we normally visit quite a few Mayan ruins, such as those at Palenque, Bonampak and Yaxchilan and quite a few spectacular waterfalls, such as Cascadas de Agua Azul and the falls at Misol-Ha.

The 2014 group included a participant who, while enjoying the butterflies we were seeing, wasn’t really a butterflier but who was very interested in photographing waterfalls. So, late in the trip, on August 10, we decided to visit a community that was reported to have an interesting waterfall that I had never previously visited.

The people in every Chiapas community that we visit have been warm and welcoming — except in Roberto Barrios! Entering this Zapatista community we felt cool and even hostile vibes.

We saw very few butterflies and, after visiting the waterfall, decided to leave. On the way out, just near the entrance, was a flowering bush that was attracting a few butterflies. I managed a few grab shots of one that looked like a Coruscating Skipper (Oxynthes corusca), but somehow looked off.

Examining the photos (this page) more carefully after my return, I realized that the butterfly was a White-striped Therra (Vacerra caniola), a species previously known only from Guatemala southward.

Above: One of the waterfalls at Roberto Barrios, Chiapas, Mexico. Aug. 10, 2014.

Opposite page left: White-striped Therra. Aug. 10, 2014. Roberto Barrios, Chiapas, Mexico.

Opposite page right: A Zapatista guard. 2005. Roberto Barrios, Chiapas, Mexico.

by Michael Reese

Any butterfly seen after November 1 in the more northern states is really a bonus and many butterfly watchers are out trying to see that last one of the year before winter begins. Reports from Nov. or later often have comments relating to frost or cool weather and yet the butterflies were still flying. For example, on Nov. 2, Denis C. Quinn was surprised to find 11 species after several frosts including a fresh Long-tailed Skipper in Nottingham, PA. Beth Polvino had a Question Mark and a Clouded Sulphur in the same frame on Nov. 2 in her backyard in Cape May Co., NJ. Andy Birkey had never seen butterflies so late in the season when he spotted Eastern Tailed-Blues and a Common Checkered-Skipper on Nov. 3 in Coldwater Springs, Mississippi National Rivers and Recreation Area, MN. Other sightings of interest included a Cabbage White seen by Melissa Bruesehoff on Nov. 5 in Warren, MI, a sighting of a Sachem on Nov. 5, a new late date, in Montello, WI by Mike Reese, and seven species including a new late date for Little Yellow reported by Steven Glynn from Dix WMA near Fairton, NJ on Nov. 11. Michael Drake had four species flying at only 50 degrees on Nov. 12 in Pennypack at Pine Rd., Philadelphia Co., PA. Still more sightings included six species, including a very small Variegated Fritillary, observed on Nov. 16 by Kathy Barylski in Catoctin Creek Park, Frederick Co., MD; seven species including 16 Common Checkered-Skippers and 15 Sachems on Nov.18 reported by Mark Adams in Albemarie Co., VA; three species seen by Curtis A. Lehman on Nov. 18 in Forest Hills, PA; six species seen by Jim Wilkinson on Nov.

42 American Butterflies, Spring/Summer 2015

On Nov. 4, 2016, Vickie DeLoach recorded 17 species in the Etowah River Park, Cherokee Co., GA, including Gulf Fritillaries. This photo was taken there on Oct. 29.

Holly Salvato photographed this stunning Erato Heliconian at the National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX on Dec. 24, 2016.

This Malachite, photographed on Jan. 2, 2017 in the Granger WMA, is the first report of this species from Williamson Co., TX and one of the farthest north occurrences ever recorded.

Bottom

This Sonoran Hairstreak was photographed in Larry Fellows’ backyard in Tucson, AZ. It appears to be the first Pima Co. record for this species, and only the 6th record for the United States.

19 including a Common Checkered-Skipper in Elkridge, MD; and an Orange Sulphur and Common Buckeye observed by Steven Rosenthal on Nov. 28 in Firemen’s Memorial Park, Point Lookout, NY.

Monarchs are always interesting sightings and reports after Nov. in the northern states even more so. Late Monarch sightings included three adults and many caterpillars reported by Carolyn McCartney on Nov. 13 even after a hard freeze in Bridgewater, VA, a fresh Monarch reported on Nov. 19 by Andrew Block in Westchester, Co., NY, and a Monarch seen by Beth Polvino on Dec. 5 in North Cape May, NJ.

If the Northern butterfliers need a butterfly fix during the cold late fall and winter, obviously the National Butterfly Center in Mission, TX would be a great place to visit! Besides sightings of 50 or more species regularly reported from there throughout the winter, you might find a new U.S. record, such as the Alana White-Skipper reported by Mike A Rickard on Nov. 28 (see American Butterflies Fall/Winter 2016 issue for photos). Other sightings at the National Butterfly Center included 71 species seen on Dec. 13 by Daniel Jones; 55 species reported on Dec. 17 by Karl and Dorothy Legler including Pavon Emperor, Blomfild’s Beauty, and Malachite; 69 species on Dec. 28 including a Common Banner and Telea Hairstreak observed by Mark and Holly Salvato; Daniel Jones observed 56 species there on Jan. 5 including Pearly-gray Hairstreak and Falcate Metalmark; and on Jan. 30 Karl and Dorothy Legler reported 47 species.

Florida butterfly sightings of note include a Nov. 6 report by Brian Ahern from Green Cay Wetlands, Palm Beach Co., FL of 12 species including 20 Atalas found in the parking area, and on Nov. 22 Laurel Rhodes and five others observed 23 species including abundant Barred Yellows and Ceraunus Blues in Celery Fields Park and Audubon Center, Sarasota Co., FL. Tom Palmer on Nov. 29 reported the first Great Purple Hairstreak observed at Lake Blue Scrub, Auburndale, 44 American Butterflies, Spring/Summer 2015

FL; Julie Appleget saw a Bartram’s ScrubHairstreak, a U.S. endangered species, on Dec. 31 at the Navy Wells Pineland, MiamiDade Co., FL; John Lampkin saw 15 species including 39 Red-banded Hairstreaks on Jan. 17 at Babcock-Webb WMA, Charlotte Co., FL; and Mark and Holly Salvato observed 17 species including a Bartram’s ScrubHairstreak and five Florida Leafwings, both endangered species, in Everglades NP, FL on Jan. 21.

California butterfly sightings include Gulf Fritillaries still being commonly seen in Anderson, CA on Nov. 1 by Barbara Peck, a species which first appeared there in 2015 and has been present regularly since; on Nov. 24 Ken Wilson reported two Becker’s Whites and 20+ Western Pygmy-Blues from Anza-borrego Desert State Park, Yaqui Wells, San Diego Co., CA; and 11 species including 200+ clustering Monarchs reported by Brett Badeaux on Dec.

This page, above Monarchs cluster on Eucalyptus trees in Huntington Central Park, Orange Co., CA. Dec 12, 2016.

This page, left Clustering Queens are joined by a Solider (center) on Nov. 9 in Live Oak Co., TX.

Opposite page Monarchs overwintered at Fort Morgan State Historical Site, Baldwin Co., AL. Jan. 11, 2017.

Although some bemoan the increased numbers of Monarchs wintering along the Gulf Coast, this may be a good thing, because the Monarch overwintering sites in Mexico may not exist in the foreseeable future.

12 from Huntington Central Park, Orange Co., CA. Other California sightings included six Red Admirals enjoying the first day of winter seen by David H. Bartholomew at the Rancho San Antonio Open Space Preserve, Santa Clara Co., CA; Brett Badeaux reporting his first butterfly of the year on Jan. 16, a Cloudless Sulphur, from UCI Ecological Preserve, Orange Co., CA; John Heyse had a Mourning Cloak, his first butterfly of the year, on Jan. 27 in Crockett Hills Park, Contra Costa Co., CA ; and on Jan. 30 David Bartholomew recorded his first butterflies of the year, a California Tortoiseshell, Mourning Cloak, and Red Admiral in the San Antonio Open Space Preserve, Santa Clara Co., CA.

In Arizona, Larry Fellows found a Sonoran Hairstreak in his Tucson backyard on Nov. 7. This was the first U.S. sighting of this species in many years, only the 6th sighting ever, and the first for Pima County.

Sightings from the southern tier of states included 17 species, including a Gulf Fritillary on Nov. 4 in Etowah River Park, Cherokee Co., GA, seen by Vicki DeLoach (see page 43 for photo); a report from Craig Marks on Nov. 12 of 17 species including Long-tailed Skippers and Ocola Skippers which both continue to have a good year on Jefferson Island, Rip Van Winkle Garden and rookery, Iberia Parish, LA; and Nov. 16 sightings from Rich Kostecke at Presidio de San Saba Historic Site, Menard Co., TX of 21 species seen around the plantings at the picnic pavilion. On Nov. 17 Don Dubois saw a Common Mestra, a species not usually common here but having a good year throughout a large area of Texas, in his backyard in Montgomery Co., TX; John Gorey saw seven species still flying despite cooler temperatures on Nov. 22 on San Vicente Cienega Trail, NM; and on Nov. 25 Richard G Snider, on a butterfly walk at Estero Llano Grande State Park, TX, saw a Perching Saliana, a new U.S. record (see American Butterflies Fall/Winter 2016 issue for photos)! Other interesting sightings included nine species still flying on Nov. 25 despite several

light frosts reported by Vicki DeLoach Etowah River Park, Cherokee Co., GA; a Malachite sighting by Eric Carpenter on Jan. 2 in the Granger WMA, Williamson Co., TX, a new county record and one of the northern most records for this species in the U.S (see page 43 for photo).; a submission from Ronald Hedden from his backyard in Lubbock Co., TX of two Orange Sulphurs and a Southern Dogface flying in 80 degree temperatures on Jan. 11, significant because five days earlier there was a low of 10 degrees and snow on the ground!; Jim Egbert continues to monitor the butterflies in far southern Alabama, especially the Monarchs, which were still common on Jan. 11 in Fort Morgan Historic Site, Baldwin Co., AL despite three nights with temperatures in the 20s; and on Jan. 23 Tom Nix recorded 37 species including his lifer Mexican Silverspot (photo pg. 47) laying eggs in the Edinburg Scenic Wetlands World Birding Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

Whether you see an unusual butterfly, an early or late sighting of a common species, or have a complete list of the species you have seen, we would appreciate hearing from you. Please send your butterfly sightings to sightings@naba.org. Those who record your sightings to the Butterflies I’ve Seen website can just click on “email trip” and send it to the address given above. Your sightings will go into the larger database and will also be available for others to see on the Recent Sightings web page.

Opposite page, top

Beth Polvino was able to photograph a Question Mark and a Clouded Sulphur on Nov. 2, in her yard in Cape May Co., NJ.

Opposite page, bottom

A Mexican Silverspot was at the National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX on Dec. 13.

Mike Cerbone is NABA’s administrator for the Butterfly Garden Habitat Program and Social Media Coordinator, currently helping to edit the 2015 Butterfly Count. He has a bachelor’s degree in English from Rutgers University, and currently lives in Basking Ridge, New Jersey with his wife, Beth, and young son, Callum. He’s working on renovating a historic 1790’s East Jersey Cottage here in Bernards Township, and has big plans for a woodland garden in the property’s backyard, along with plenty of host and nectar plants for butterflies. Michael was born and raised in the Garden State, and returns to it after spending almost a decade living in Oakland, California and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Don Dubois’ formal training is in the area of chemistry, with a Ph.D. from the University of Kansas. He retired in 2002 after working 32 years as a chemical researcher and relocated to the Houston, Texas area. Since then Don has busied himself converting a large barren backyard into a butterfly friendly habitat. This gardening effort has been rewarded with visits by over 80 species of butterflies, several of which were county records. His interest in butterflies and insects started at an early age and involved the usual insect collection. With

the availability of good quality, reasonably priced digital cameras, collecting was abandoned in favor of photography. Don’s interest in native plants has been nurtured by volunteering with native plant specialists at Mercer Arboretum and Botanic Gardens.

Jeffrey Glassberg brief biographical sketch appeared in the Fall/Winter 2016 issue of American Butterflies

Mike Reese’s brief biographical sketch appeared in the Summer 2016 issue of American Butterflies

Wade Wander’s interest in natural history started with birds before the age of 10. He then became curious about plants, herptiles, and mammals. He rekindled an interest in butterflies about 20 years ago and 10 years ago started to study moths (and more recently, all insects). He has recorded more than 550 species at his moth station in northwestern New Jersey, and has presented numerous programs on moths and other insects, hoping to bring the enjoyment of these fascinating animals to a wider audience. He and his wife, Sharon, own and operate Wander Ecological Consultants, an environmental consulting business that, among other things, surveys for Endangered and Threatened species and conducts biological surveys.

How was the Alaska article? I don’t know, I’ll Ask Her.

That is a wonderful saga of those two men’s trip to Alaska, plus all the photos. I enjoyed reading it, and I appreciate the time they took to compile it.

Marjorie Rachlin, Washington DC

Wow! What an adventure Jeff Glassberg and Jim Springer had in Alaska. Good on ya’.

Jim Anderson, Sisters, OR

I did enjoy the adventures in Alaska. I was there in March where we had gale force winds, snow blizzards, rain squalls and the occasional peek at the sun. It was still a wonderful trip.

Jane Ruffin, Gulph Mills, PA

Jim Springer and Jeff Glassberg’s Alaska trip was beautifully presented.

Ken Kertell, Tucson, AZ

In your excellent Alaska article, I can’t find where you have identified the subject of the inset photo at the bottom of page 15. Is it a Melissa Arctic? The reason I’m asking is that I am trying to put a name on a photo I took of a similar-looking butterfly June 10, 2015, at Denali National Park.

Mike Ready, Arlington, Virginia

Yikes, the last line in the caption “a hilltopping lifer Sentinel Arctic (inset).” got cut off! Thanks for picking up on this. Sentinels are not known to be found in Denali. The second edition of A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America, now available, fully covers the Arctic. Sentinel Arctics have FW eyespots while Melissa Arctics do not. Chryxus is very similar but FW eyespots usually are round [Ed.].

Thanks for publishing the interview with Marianna Wright. The information about how different demographics respond to plants and animals is insightful. I had no idea that some people are afraid of butterflies! I

think everyone involved in environmental education needs to read this article, so that they have a better understanding of how to reach every individual. We need everyone on our side; those who love butterflies and those who hate them. Marianna provided some important information that could lead to better approaches to teaching some students. Sal Levinson, Berkeley, CA

(continued from inside front cover)

If you would like one of your photos to be considered for this feature, please submit no more than two, high resolution, interesting and unusual photos of either adult or immature butterflies taken of wild, unmanipulated butterflies or immatures in the United States, Canada, or Mexico. Photos should be in digital form, and should be uncropped and unaltered/minimally altered. Send your entries on a CD to: NABA Members Gallery, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960.

We’d like to ask those NABA members who have planned estates, to consider including NABA and the National Butterfly Center in their plans. This will allow you to continue to help butterflies and conservation.

Those of you who generously contribute donations to NABA and work at a large corporation may be able to double your contribution. Many corporations have matching gift programs. Check with your human resource or public relations department.