Butterflies American

Laugh at Jack Frost!

Join NABA’s Survey of Frosted Elfins

NABA has received a Conservation License Plate grant from Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept. to survey eastern Texas for rare Frosted Elfins in the early spring (late February — April) of 2018.

We invite all NABA members to participate! If you live in, or near, east Texas, you are perfectly positioned to make significant contributions to our knowledge of this butterfly. If you live farther afield, for example in Montana, Michigan or Maine, this will be your chance to escape winter and get a jump on the butterfly season. And, while NABA won’t be able to reimburse your expenses traveling to Texas nor your living expenses, approved volunteers will be reimbursed for reasonable travel expenses within Texas.

To learn more about this fun-filled, butterfly community opportunity, please visit http://www. naba.org/frosted_elfin.html.

NABA is offering free trial memberships to people who have not previously been NABA members, if they help NABA monitor butterflies by entering data into the Recent Sightings page and/or participate in the NABA Butterfly Count program. The free, trial membership includes access to digital versions of NABA publications as well as access to NABA-Chat and other NABA programs. So, invite your friends, family and neighbors to participate in Recent Sightings and/or the Counts, helping to monitor and conserve butterflies throughout North America — they will be rewarded with a free, trial membership.

The best guide to butterfly gardening — NABA’s own, of course! — authored by Jane Hurwitz, editor of NABA’s Butterfly Gardener, is scheduled fto be published this April by Princeton University Press. Keep an eye out for it.

It’s official! The thirteenth NABA Biennial Members Meeting will be held September 16-19, 2018 in Tallahassee, Florida. Don’t miss this great opportunity to see butterflies you may never have seen before, including Yehl Skipper, Berry’s Skipper and Dotted

Skipper, along with thousands of individual butterflies, including sweeps of seven species of swallowtails. Better yet, you’ll be able to connect with ardent butterfliers from throughout the country. NABA meetings are always fun!

On October 21, 2017, there was a memorial celebration lunch for Jane Vicroy Scott, NABA’s late Secretary/ Treasurer. About 100 people traveled from throughout the United States to attend the four hour event. As she always did, Jane brought people together.

The Jane Vicroy Scott Memorial Video can be seen at https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=EWB4MQllD5g.

Thank you to the hundreds of NABA members who have sent letters and email messages of condolence and to the the many NABA members who have contributed to the ongoing Jane Vicroy Scott Memorial Fund.

We’d like to ask those NABA members who have planned estates, to consider including NABA and the National Butterfly Center in their plans. This will allow you to continue to help butterflies and conservation.

NABA has begun a project to save endangered Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreaks. So far as is known, Grannybush (pineland croton) is the only plant species eaten by Bartram’s Screub-Hairstreak caterpillars. Pineland croton is restricted to pine rockland habitat, which has largely been, and continues to be, destroyed. Bartram’s Scrub-Hairstreak also appears to be restricted to pine rockland habitat, but that may be because that is the only place that it’s caterpillar foodplant is found.

NABA is trying to replicate the success that South Florida gardeners inadvertantly had in stablizing the population of Atalas and increasing their range. Atalas were thought to possibly be extinct, but then, about 25 years ago, cycads became popular garden plants in South Florida. Even though the cycads planted in land owners gardens were almost always non-native species, Atalas still were able to use these plants as caterpillar foodplants.

Continued on inside back cover

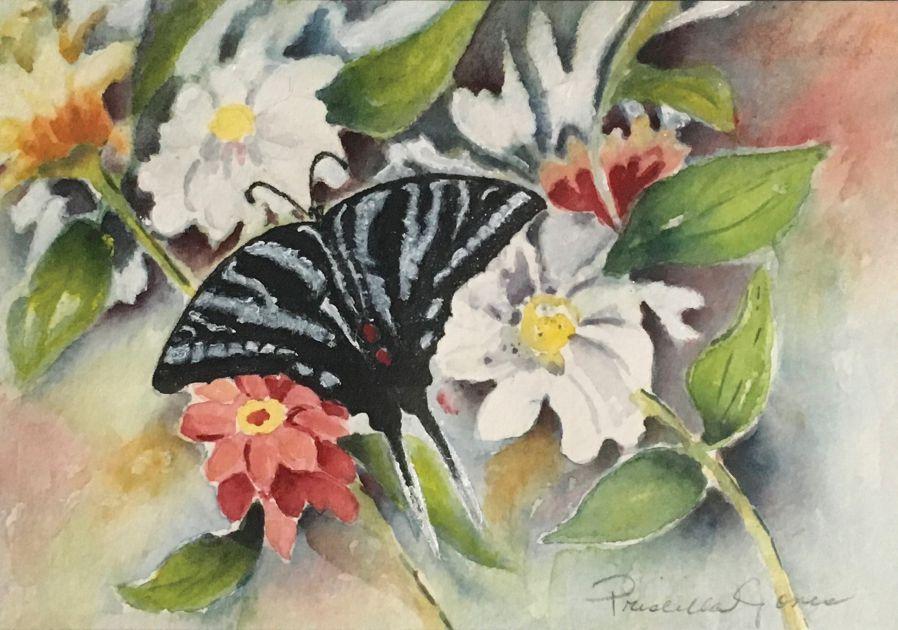

Front cover painting “Butterfly Lake” is by Jennifer Becker. See page 76 for Art Contest article.

The North American Butterfly Association, Inc. (NABA), a non-profit organization, was formed to promote public enjoyment and conservation of butterflies. Membership in NABA is open to all those who share our purpose.

President: Jeffrey Glassberg Vice-president: James Springer Secrty./Treasurer

Ann James Directors: Jeffrey Glassberg

Fred Heath

Yvonne Homeyer

Ann James

Dennis Olle

Robert Robbins

James Springer

Patricia Sutton Scientific Advisory Board

Nat Holland

Naomi Pierce

Robert Robbins

Ron Rutowski

John Shuey

Ernest Williams

Volume 25: Numbers 3/4

Fall/Winter 2017

Inside Front Cover NABA News and Notes

2 Butterflies Battle Border Wall by Jeffrey Glassberg

4 Definitive Destination: Ralph E. Simmons State Forest, Nassau Co., Florida by Bill Berthet

24 Butterfly Scouts, Be Prepared! by Jeffrey Glassberg

36 The National Butterfly Center Gets Greener and Follows the Sun by Marianna Treviño-Wright

38 Butterflies Along the Colorado Trail by Mark Nelson

46 You Are What You Eat

47 Monarch on Butterfly Milkweed in TX by Don Dubois

51 Guava Skipper on Guava in TX by Jan Dauphin

58 Southern Skipperling on Bermudagrass in TX by Jan Dauphin

62 Members Photo Gallery by Jill Gorman

64 Hot Seens by Mike Reese

76 NABA Art Contest

79 Readers Write

80 Contributors

American Butterflies (ISSN 1087-450X) is published quarterly by the North American Butterfly Association, Inc. (NABA), 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; tel. 973285-0907; fax 973-285-0936; web site, www.naba.org. Copyright © 2018 by North American Butterfly Association, Inc. All rights reserved. The statements of contributors do not necessarily represent the views or beliefs of NABA and NABA does not warrant or endorse products or services of advertisers.

Editor, Jeffrey Glassberg

Editorial Assistance, Matthew Scott and Sharon Wander

Please send address changes (allow 6-8 weeks for correction) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960; or email to naba@naba.org

NABA isn’t a litigious organization. NABA normally tries to work with government agencies, even if NABA doesn’t agree with many of the actions taken (or not taken) by those agencies. Until recently, the only lawsuit ever instituted by NABA was filed in 1997 when NABA sued the United States Army in an attempt to block it from destroying the only viable population of Regal Fritillaries east of the Mississippi. Perhaps surprisingly, the United States Army quickly agreed with NABA’s arguments and scrapped their plan to convert Regal Fritillary habitat into a tank maneuvering area. The result — Regal Fritillaries are still flying at Fort Indiantown Gap Military Reservation in Pennsylvania.

As many of you are probably aware, NABA has now been forced to file a second lawsuit, this one on December 11, 2017, against the United States Dept. of Homeland Security and the United States Customs and Border Protection.

On July 20, 2017, one day before my wife, Jane Vicroy Scott, died, Marianna TreviñoWright, the executive director of the National Butterfly Center, discovered contractors clearing butterfly plants from a portion of our property. Although she was able to convince the contractors to leave, the Chief Patrol Agent for the United States Customs & Border Protection Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Sector, after first claiming that no one had been there, later admitted that the contractors (from Alaska) were there but stated they had a legal right to proceed with the work they were doing and that when they returned they would be accompanied by armed guards.

He also told Marianna that the United Stated Dept. of Homeland Security had plans to construct 28 miles of border walls in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, running through properties that include Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, and the National Butterfly Center.

However one feels about immigration, and especially about illegal immigration,

constructing an expensive, divisive and ineffectual border “wall” makes no sense.

First, of the undocumented immigrants now entering the United States, more than two-thirds of them arrive here with legal visas that they then overstay. So a wall will have no effect upon almost 75% of illegal immigration. As Marco Rubio, a U.S. senator from Florida said “In Florida, 70 percent of the people here illegally came on an airplane. They overstayed a visa — the wall isn’t going to address that.”

Second, the large increase in border patrol personnel and the increased use of sophisticated technology to detect and apprehend people illegally crossing the border, has had an effect. According to Fox News in late 2016, “Last year, Border Patrol arrests — one gauge of illegal crossings — fell to the lowest level since 1971.” The number of arrests were even less in 2017.

Third, a border wall would cede thousands of square miles of United States property, including two-thirds of the National Butterfly Center, to Mexico. The boundary between Mexico and the U.S. is in the middle of the Rio Grande. A wall cannot be built there. It also cannot be built on the northern edge of the river because building isn’t permitted in the flood plain under a U.S.- Mexico treaty (and it’s dangerous) and because following the very sinuous and twisting path of the river would double or triple the needed length (and cost) of a wall. So, the wall is slated to be placed away from the river, in some places up to a mile or two from the river. The thousands of acres behind the wall, most of it privately owned, would become a no-man’s zone, not a usable part of the United States but not quite part of Mexico either.

NABA’s lawsuite focuses on the unconstitutional taking of NABA’s property, but also on the continued illegal activities of the U.S. Border Patrol who claim to have authority under a law that allows them to patrol lands

continued on page 79

Please photocopy this membership application form and pass it along to friends and acquaintances who might be interested in NABA

Yes! I want to join NABA, the North American Butterfly Association, and receive American Butterflies and The Butterfly Gardener and/or contribute to building the premier butterfly garden in the world, the National Butterfly Center. The Center, located on approximately 100 acres of land fronting the Rio Grande River in Mission, Texas uses native trees, shrubs and wildflowers to create a spectacular natural butterfly garden that importantly benefits butterflies, an endangered ecosystem and the people of the Rio Grande Valley.

Name:

Address:

Email (only used for NABA business):______________________ Tel.:______________________ Special Interests (circle): Listing, Gardening, Observation, Photography, Conservation, Other

Tax-deductible dues enclosed (circle): Regular $35 ($70 outside U.S., Canada or Mexico), Family $45 ($90 outside North Am.). Special sponsorship levels: Copper $55; Skipper $100; Admiral $250; Monarch $1000. Institution/Library subscription to all annual publications $60 ($100 outside U.S., Canada or Mexico). Special tax-deductible contributions to NABA (please circle): $125, $200, $1000, $5000. Mail checks (in U.S. dollars) to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960

American Butterflies welcomes the unsolicited submission of articles to: Editor, American Butterflies, NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960. We will reply to your submission only if accepted and we will be unable to return any unsolicited articles, photographs, artwork, or other material, so please do not send materials that you would want returned. Articles may be submitted in any form, but those on disks in Microsoft word are preferred. For the type of articles, including length and style, that we publish, refer to issues of American Butterflies.

If you have questions about missing magazines, membership expiration date, change of address, etc., please write to: NABA, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960 or email to naba@naba.org.

American Butterflies welcomes advertising. Rates are the same for all advertisers, including NABA members, officers and directors. For more information, please write us at: American Butterflies, 4 Delaware Road, Morristown, NJ 07960, or telephone, 973-285-0907, or fax 973-285-0936 for current rates and closing dates.

Occasionally, members send membership dues twice. Our policy in such cases, unless instructed differently, is to extend membership for an additional year.

NABA sometimes exchanges or sells its membership list to like-minded organizations that supply services or products that might be of interest to members. If you would like your name deleted from membership lists we supply others, please write and so inform:

NABA Membership Services, 4 Delaware Rd., Morristown, NJ 07960

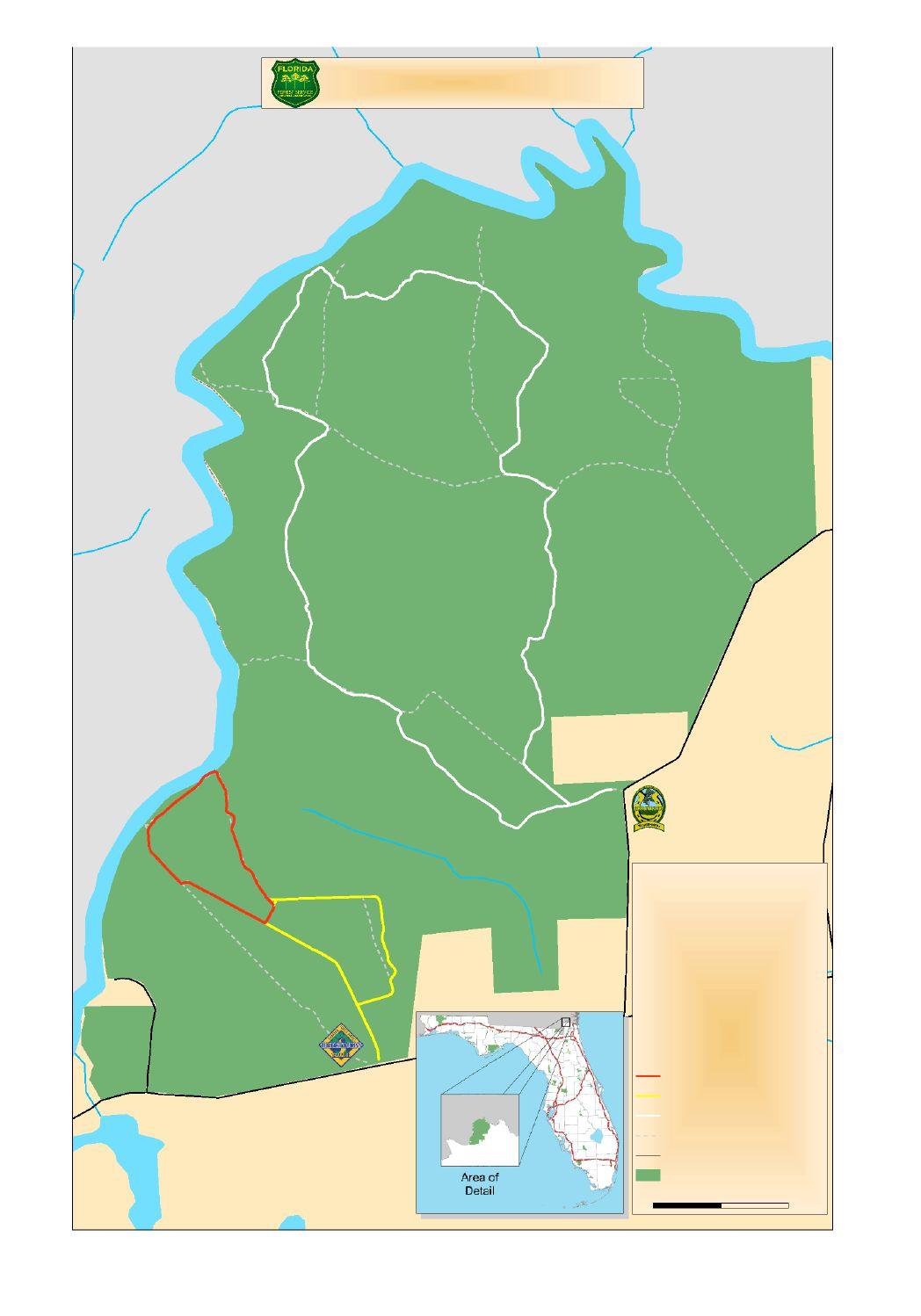

by Bill Berthet

Ralph E. Simmons

Memorial State Forest (Simmons SF) is a 3,638 acre preserve that supports twelve types of natural communities. These

Above, main photo: The St. Mary’s River. Aug. 27, 2017. Simmons State Forest, Nassau Co., FL.

Above, inset: Hackberry Emperor. July 3, 2015. Simmons State Forest, Nassau Co., FL.

include 998 acres of sandhills, 162 acres of upland hardwood forest, 693 acres of wet flatwoods, 134 acres of seepage slope, 481 acres of upland pine forest, 55 acres of mesic flatwoods, 422 acres of floodplain swamp, 3 acres of river floodplain lake, 414 acres of bottomland forest, 275 acres of baygall, and 1 acre of dome swamp.

Located in the extreme northeastern corner of Florida, about 36 air miles northwest of downtown Jacksonville, the northern part of the forest borders Georgia and around seven miles of the St. Mary’s River. The forest contains five intermittent drains that flow into the river, several seepage slopes, and one river floodplain lake. The St. Mary’s River is

Dotted Skipper on Fewflower Blazingstar. Aug. 31, 2009.

Durbin Preserve, Duval Co., FL.

Yehl Skipper on Coastal Plain Chaffhead. Oct. 5, 2014. Simmons S.F.

Dion Skipper on Coastal Plain Chaffhead. Sept. 30, 2015.

Simmons S.F.

Palmetto Skipper on Coastal Plain Chaffhead. Oct. 8, 2012.

Bull Creek WMA,

approximately 125 miles long, draining the eastern side of the Okefenokee Swamp to its mouth in the Atlantic Ocean.

The property was acquired by the St. Johns River Water Management District using Save Our Rivers Funds. It was leased to the Florida Forest Service for management in September 1992 as the St. Marys State Forest. In 1996, the forest was renamed for Ralph E. Simmons, a former chairman of the Board of Directors of the St. Johns River Water Management District, who was instrumental in the purchase of the property.

There are three designated entrances to Simmons. Two entrances include grass parking areas with a kiosk. A third parking area is located at the end of Scott’s Landing Road. This area provides parking for the Simmons SF picnic area as well as for the cooperatively managed boat ramp. A walk-in entrance is also available where vehicles must park by the side of the road. There are currently ten miles of established trails on Simmons SF. These trails are maintained as three distinct trail systems known as the red, white and yellow trails. In addition to the three marked

Top: Gopher tortoise burrows are common in Simmons SF, however this one was at Branan Field Wildlife and Environmental Area, Duval Co. on Apr 23, 2007.

Above: Many Yankees think that water moccasins (cottonmouths) can help them walk on water. June 10, 2015. Simmons SF.

trails, Simmons SF is also a part of the Great Florida Birding trail, with more than 125 bird species documented. There are three primitive campsites in Simmons SF; two river sites and a group camp site.

The small trading hamlet of Mills Ferry was established on the St. Marys River just east of Simmons SF during the Florida’s British Period (1763-1783). Mills Ferry was first chronicled in the early 1770s by the naturalist William Bartram. He noted that the Seagrove & Co. trading post existed here where the British King’s Road crossed the river connecting Charleston, South Carolina to St. Augustine, Florida. Towering Longleaf Pines were cut along this section of the St. Marys River to mast the tall ships of the British Navy.

Since 2007 I have been working as a volunteer with the Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI) and the Florida Forestry

Service surveying for critically imperiled, and other FNAI-tracked butterflies, observing and documenting 95 species, plus six more observed by others, totaling 101 species of butterflies in this 3836 acre “Butterfly Bonanza” forest. Currently there are 15 FNAItracked species of butterflies documented at Simmons SF, including the seldom seen Frosted Elfin, Spring Azure, Creole Pearlyeye, Wild Indigo Duskywing, Eastern Tailed Blue, Mourning Cloak, and a reliable spring and fall brood of Dusky Roadside-Skippers.

I look forward each year to the start of the butterfly season in Florida, beginning with the two to three week period in the month of February for the nectaring opportunities and the showy blossoms of Chickasaw Plum. Enter the power line corridor entrance from Lake Hampton Road, walk past the locked gate for several hundred yards, take the first right, and the plum grove will be on both sides of forest

This White Peacock was the 101st species of butterfly seen in Simmons SF. Sept. 23, 2017.

In February and March, Chickasaw Plums are a magnet for nectaring butterflies and, of course, they attract stray butterfliers as well. Feb. 24, 2016. Simmons SF.

road. Peak bloom lasts less than a week and the exact timing varies year to year.

In Chinese culture the five petals of plum blossoms symbolize the “five blessings” referring to longevity, wealth, health and composure, virtue, and the desire to die a natural death in old age.

There is a grove of 21 trees in this area. The “champion thicket” measures around 38 ft. high, 50 ft. in width, 45 ft. in depth and has 42 trunks! In 2016 only seven were in bloom. Over the years, I have observed 23 species of butterflies in this grove. I sometimes scratch my head, curious to know why the same species of butterflies can be found year after year perched, or feeding only in several small areas in this grove of trees. I marvel at the audible level of the humming and buzzing

created by plasterer, mining, carpenter, honey, and bumble bees nectaring and the many song birds hidden and camouflaged in the thicket.

It’s always an entertaining sight watching three to five Zebra Swallowtails flying together, daisy chaining in various acrobatic formations, then splitting off like a Blue Angels maneuver, or getting a glimpse of overwintering Monarchs.

This area is also home to many gopher tortoise burrows and southeastern pocket gopher mounds.

In 2011, FNAI conducted a survey for gopher tortoises across the property. This survey evaluated approximately 820 acres of suitable habitat. It divided the habitat into three different types: sandhill, pine plantation and ruderal. The study found multiple size

Zebra Swallowtails, nervous fliers in the extreme, will sometimes stay still when presented with Chickawaw Plum blossoms. March 15, 2009. Simmons SF.

classes of burrows, suggesting multiple age classes present within the forest and evidence of recent reproduction. The study concluded with an estimate of 1,360 active and 607 inactive burrows.

In March and April I can be found roaming the 55 acre block of upland pine and sandhill habitats looking for eggs, caterpillars, and adults of FNAI ranked S1, Frosted Elfins near their palmate-shaped leaf hostplant Sundial Lupine. Nectar sources for this rare butterfly include Sundial Lupine, Shiny Blueberry, Dwarf Huckleberry, and hawthorns. The last instar caterpillars are sometimes attended by ants, and are capable of pupating more than one inch underground.

Another target species is the small, timid, dark, fast-flying, FNAI S2, Dusky Roadside-

Skipper. Talk about frustrating: while you are crawling around trying to get close enough to obtain a good photograph of one of these little guys, they are saying “see ya later” as they disappear off into the pine forest. Caterpillars feed on Bearded Skeletongrass (and perhaps other grasses as well).

The upland pine and sandhills area has a large stand of Gopherweed Wild Indigo that attracts many butterflies and other northeastern Florida pollinators in the area to nectar on the bright yellow flowers. Eastern Redbud, Wild Cherry, Carolina Willow and the vine Evening Trumpetflower are also important nectar sources for butterflies and other northeastern Florida pollinators during this time.

During these months (including February) I also visit the slope forest that has cane

Southern Pearly-eye are regular, but uncommon, in and near cane breaks. May 1, 2015. Simmons SF.

breaks of Giant Cane bordering the St. Marys River near the camping shelter. This upland hardwood closed-canopy forest, is dominated by deciduous hardwood trees on mesic soils with an understory of Highbush Blueberry bushes overshadowed by Dahoon and American Holly, host trees for Henry’s Elfins.

On February 5, 2012 next to the cabin shelter, (take the second Penny Haddock Entrance, walk the forest road, then take the first right and continue until the trail dead ends) all the stars were aligned and I watched two Mourning Cloaks glide down in a zigzag pattern from the canopy of the forest to land on fresh horse dung. Mourning Cloaks are very rare in Florida. After several stealth-like approaches, I still could not get close enough for a decent picture. I put my Tilley hat on the ground and hid behind some bushes. Teasing

me, the Mourning Cloaks would flutter around the hat but would not land. Being very patient, I hid behind a tree until one of them landed close enough for a decent shot, popping out from behind the tree I was finally able to take the “record” shot. None have been seen on numerous visits since then.

Wearing snake boots, thick pants, a long-sleeved shirt, a wide-brimmed Tilley hat, gloves, insect spray, and glasses (not sunglasses) I will be skulking around the wet areas of the bottomland forest in April and May, surveying for Harvesters, Hackberry and Tawny Emperors, Southern and Creole Pearlyeyes, Appalachian Browns, Gemmed Satyrs, Zabulon and Laced-winged Roadside Skippers and others. A population of Creole Pearlyeyes was only recently discovered here and Simmons SF is the only place this rare species

Simmons SF is the only place in Florida where Creole Pearly-eyes are known to occur. July 4, 2015. Simmons SF.

is known to occur in Florida. I look for Giant Cane, host plant for the pearly-eyes and others, and Narrowfruit Horned Beaksedge, a host sedge for Appalachian Browns. This habitat can be hazardous. You have to be aware of not tripping on cypress knees, uneven wet terrain, spiny plants and vines, mosquitoes, spiders, venomous snakes, humid conditions fogging up your glasses, and ticks. After arriving back at the car I shed all my clothes, put them in a plastic bag, then put on a new set of clothes. I always check for ticks and take a shower when I get home.

Bottomland forest is a deciduous, or mixed deciduous/evergreen, closed-canopy forest on terraces and levees within riverine floodplains and in shallow depressions. Bottomland forests may be inundated with water for a portion of the year. The diverse

overstory is dominated by Red Maple, Sweetgum, Sweetbay, Swamp Tupelo, Tuliptree, and Loblolly Bay. Other trees which may be found in this system include Eastern Redcedar, Live Oak, bald cypress and Cabbage Palmetto. The mid-story consists of scattered trees and shrubs, such as Swamp Titi, Swamp Doghobble, Dahoon, Inkberry, and Fetterbush Lyonia. The ground cover here consists of sedges, ferns, and various grass species. The outside edges of this community are surrounded by herbaceous grasses. If you’re at the right place at the right time, you might see Hackberry and Tawny Emperors lapping up sap oozing from the trunk of a tree. When this happened to me, it reminded me of being a 10-year-old boy in Berkley, Michigan looking for sap flows in the hardwood forest near my home, and finding

Mourning Cloaks that were so fixated on the sap that they were oblivious to my presence.

May is hairstreak month. I look for Farkleberry, Deerberry, Swamp Titi, blackroot, Button Eryngo (also known as ratttlesnake master)(the Timucuan Indians used the roots for neuralgia and the leaves for dysentery, chewing the leaves increased saliva flow) Saw Palmetto blooms, Eastern Redcedar, and others, being rewarded with Great Purple, Oak, Red-banded, Striped, White M, Juniper, and Gray Hairstreaks!

On May 25, 2008 I came across two Saw Palmettos with more than a dozen butterflies fluttering around the numerous white blooms. I counted seven Oak, five White M, and one Striped Hairstreak, in about 20 minutes — another spectacular event from Mother nature!

Along the edges of floodplain swamps and seasonal water creeks, the very showy blooms of Orange Azaleas and of Mountain Azaleas wait for Eastern Tiger, Palamedes,

This page: Dusky RoadsideSkippers are mostly rare. Simmons SF is one of the best places to see them. This one is nectaring at PoorJoe. Aug. 26, 2012. Simmons SF.

Opposite page top: Lace-winged Roadside-Skippers are always a treat. This one is also nectaring at PoorJoe. Sept. 1, 2012. Simmons SF.

Opposite page bottom: Cofaqui Giant-Skippers are among the least-seen butterflies that are resident in the United States. Sept. 12, 2010. Simmons SF.

Mimics are very rare strays to the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf Coasts. This one was at Simmons SF on Aug. 30, 2016.

and Spicebush Swallowtails to nectar. For nectaring skippers I am on the hunt for Kidneyleaf Rosinweed hoping for a first brood of Meske’s Skippers. In the pine flatwoods area I look for the purple blooms of Buckroot another premium nectar plant that blooms at this time of year.

A quick June and early July visit is to the Florida Power and Light Company’s 300-foot-wide powerline right-of-way traversing the Southwest corner of the forest bordered by the St. Marys River. Take the powerline trail entrance off Lake Hampton Road, follow the trail down the slope to the bottom, turn left, walk up the sandhill, then turn right just before the first powerline tower to find a seasonally wet area between the road and the forest margin. Here you might find a colony of freshly emerged Common

Wood-Nymphs evasively hiding in the tall grass. When disturbed, they usually take a bouncy and erratic flight and dive into thick cover, or fall “lifeless” to the ground around Wax Myrtle bushes. The males emerge up to a week before the females, then die soon after mating. Females then lay their eggs on Broomsedge Bluestem in late summer. When the caterpillars hatch, they quickly go into diapause, then complete their development the next spring.

This seepage slope habitat is an open, grass-sedge dominated community kept continuously moist by groundwater seepage. It occurs in areas with rolling topography, and is usually bordered by well-drained sandhill or upland pine communities. Seepage slopes are always moist, except during an extreme drought, but they are almost never

Find the nectar and host plants and you’ll find butterflies.

Left: A Palamedes Swallowtail gulps nectar from a Pine Lily in Simmons SF. Sept. 7, 2008.

Right: A Pinewoods Milkweed in Simmons SF holds the promise of more Monarchs, and certainly more Pinewoods Milkweed. Aug. 24, 2012.

flooded. They consist of a diverse and unique herbaceous layer. On the drier slopes, Beyrich Threeawn (wiregrass) is the dominant component. In wetter areas, the herbaceous layer is dominated by several species of beaksedge, cane¸ Whitehead Bogbutton, Sphagnum (moss), Netted Chainfern, Parrot and Hooded Pitcherplants, Blue-flower Butterwort, and Pink Sundew. Pine Lily is also found in this community at Simmons SF and you might find Cloudless Sulphurs, Palamedes Swallowtails (see photo, this page) and Spicebush Swallowtails burrowed into the throat of this beautiful flower.

In addition to rare butterflies, Simmons SF harbors rare plants, including Alachua Bully, Florida Bellwort and Florida Hartwrightia. One never knows what one will find in Simmons SF. On August 30, 2016 on a forest road Northwest of the hunt station, Patrick Leary was surprised to see a female Mimic, a rare stray anywhere in the United States. Pat was able to take several photos (see previous page) before the butterfly disappeared into the forest. Widely distributed in the tropics, native to Africa, Asia and Australia, Mimics were introduced to Caribbean islands and northern South America, and occasionally stray to the

Right top: A Dixie Iris with landing pads made for skippers. April 24, 2015. Simmons SF.

Right bottom: Whitemouth Dayflowers attract more people than they do butterflies. Aug. 26, 2012. Simmons SF.

Opposite page: A view of the “PoorJoe” trail, one of the best places to see Dusky Roadside-Skippers in the right season. Although the PoorJoe are inconspicuous, the roadside-skippers don’t have any problem finding them. Aug. 27, 2017. Simmons SF.

southern United States.

September and Early October can be popping with butterfly diversity and numbers. My first stop I call the “PoorJoe” trail. From the main entrance along Penny Haddock Road you follow the white trail past the hunt station then take the first trail to the right following the sandhill slope, and seepage area, to the small wooden “bridge.” At this time of year the plant PoorJoe (Diodia teres) is in bloom, attracting numerous butterflies (particularly skippers). In one very small area, during the years 2008 to 2015, between the times of 11:00 – 12:15 and the dates of 8-26 to 9-15, I have observed between one and eight Dusky Roadside-Skippers nectaring on flowers of this plant. This reclusive “Swamp Fox” skipper, flies close to the ground, very briefly

stopping to nectar. Further down the trail there is a reliable spot to observe Lace-winged Roadside-Skippers, also nectaring on PoorJoe.

On September 12, 2010 while leading a Florida Native Plant Society Ixia Chapter field trip, a large, heavy-bodied butterfly zipped by, landing on a Longleaf Pine about 20 feet away. My heart started pounding and my adrenaline level was sky high as I quickly approached, camera in hand, firing off five shots at a fresh, female Cofaqui Giant-Skipper (see pg. 15) before she took off in a straight line, disappearing into the forest. I have since observed one more adult in this area and routinely find their eggs on Adam’s-needle Yucca.

I always look forward to taking the second entrance on Penny Haddock Road

and working both sides of the forest road. During these two months this pine flatwoods area has the greatest diversity and abundance of butterflies in Simmons SF, with skippers having the starring role.

When conditions are right, a mixture of flowering plants, including Carolina Redroot, chaffheads, PoorJoe, prairie-clovers, ironweeds, goldenrods, elephantsfoots, and others, attract a glorious assortment of nectaring butterflies.

On one day I remember well, Oct. 5, 2012, I found 24 Meske’s Skippers — eight of them nectaring on Summer Farewell Prairie-Clover in one small area. Other skippers in this habitat include Dion, Dotted, Yehl, Byssus, Palmetto, Crossline, Brazilian, and others.

My final stop will be along Scott’s Landing Road (heading towards the boat ramp) with Romerillo Beggarticks and Brazilian Verbena bordering both sides of the road — another butterfly bonanza area.

The only known outbreak of a plant disease in Simmons SF at this time is laurel wilt (formerly known as Redbay wilt). The disease is caused by a fungus (Raffaelea lauricola) that is introduced into host trees by a non-native insect, the Redbay ambrosia beetle (Xyleborus glabratus). This disease primarily effects Redbay. Other trees in the laurel family are also susceptible. Numerous Redbays in Simmons SF exhibit the symptoms of laurel wilt. At this time, there are no practical control methods in a forest setting. Although Redbay is the primary host tree for Palamedes Swallowtails, Redbay wilt does not appear to have greatly affected their numbers.

I use the mantras “Today’s the Day” and “Hope Springs Eternal” to keep my motor running strong. I hope readers will decide that “Today’s the Day” and visit Ralph E. Simmons State Forest — you never know what you’ll see flying by!

The forest can be accessed through three gates. The first, on Lake Hampton road, is located in a large parking area and provides access to the yellow and red trails. The yellow trail is a 1.75 mile loop that takes hikers across a sandhill ecosystem through some longleaf and oak savannah. The 1.5 mile red trail is located around the halfway point of the yellow trail, and carries hikers down a seepage slope into a meadow overlooking the Saint Mary’s River. The trail runs along the river before turning south and carrying users through a bottomland forest and uphill to rejoin the yellow trail. The entire loop of both trails is roughly 3.25 miles.

The second gate, located on Penny Haddock road, provides access to the bulk of the forest via the 6.5 mile white trail. Starting at the parking lot, the white trail crosses a sandhill longleaf savannah before entering flatwoods consisting of slash and Loblolly pine, and numerous loblolly bays and oak trees. About 1.75 miles from the gate, hikers will encounter a primitive campsite adjacent to the Saint Mary’s river that is free to use. The white trail continues on past some cypress ponds and a fast flowing stream, through some slash pine plantation. At around 2.5 miles, users will come to a T-intersection where they will see some recent logging activity. To the West they can access another primitive campsite with a beach and picnic table, as well as the continuation of the white trail. If users choose to turn East at the T-intersection, they can cut about 1.6 miles off the total length of the white trail by following the forest road. Those who do so will miss out on viewing picturesque palmetto understory and unrivaled views of the Saint Mary’s River. East of where the white trail and road meet again, the road

by Jeffrey Hill Forester, Florida Forest Service

will continue uphill to the third gate and our primitive cabin, while the trail will turn south where users can enjoy some 80 year-old oak trees and cross a 200-acre seepage slope. The trail then turns uphill briefly, and users will find themselves in a sandhill longleaf plantation, which will take them back to the gate.

The third gate is also on Penny Haddock road, and is the only one without a parking area. Generally, this gate is only used by official forest management personnel or to access our primitive cabin. The cabin can be reserved for free by calling the forest office at 904-845-4933 or emailing Jeffrey.Hill@ freshfromflorida.com with the dates and party size requested.

During hunting dates, other recreational activities, including butterflying and hiking, are not allowed. Hunting dates for the first half of 2018 are Jan. 27 - Feb. 4; March 10, 11, 17-19, 30, 31; April 1, 13-15. Hunting dates for the second half of 2018 will be available at www.myfwc.com after May 2018. Visitors can view the forest by foot, bicycle, or horseback, but any motorized vehicle is offlimits without a special permit.

In cooperation with NABA, if there is sufficient interest, we may be able to establish a “butterfly day” on which butterfliers will be able to drive their vehicles into the state forest. In addition, butterfliers can also call the forest office at 904-845-4933 and speak to me about special permits for taking their vehicles into the forest. Collecting plants, animals, or archaeological artifacts without a permit is prohibited.

If you get tired of seeing Common Buckeyes, you need to open your eyes.

Sept. 26, 2017. Simmons SF.

Abbreviations: A, abundant, likely to see more than 20 individuals per visit to the right unit at the right time; C, common, likely to see 4-20 individuals; U, uncommon, likely to see 1-3 individuals; R, rare, unlikely to see any individuals. The numbers indicate flight months at Ralph E. Simmons State Forest to date (1 = January, 2 = February, etc.).

Pipevine Swallowtail C 2-10; Zebra Swallowtail C 2-10; Black Swallowtail U-C 2-10; Giant Swallowtail R 3-10; Eastern Tiger Swallowtail C 2-10; Spicebush Swallowtail C 3-10; Palamedes Swallowtail C 2-10; Checkered White R 4-9; Great Southern White A 3-12; Orange Sulphur R 5-9; Southern Dogface U 3-11; Cloudless Sulphur C-A 1-12; Barred Yellow C 2-12; Little Yellow U-C 3-12; Sleepy Orange U-C 3-12; Dainty Sulphur R 7-9; Harvester R 4-6; Great Purple Hairstreak U 3-10; Striped Hairstreak R 4-6; Oak Hairstreak U 4-5; Frosted Elfin R 2-3; Henry’s Elfin R 2-3; White M Hairstreak U 3-9; Gray Hairstreak C 3-11; Red-banded Hairstreak U 2-11; Ceraunus Blue C 5-11; Eastern Tailed-Blue R 4; Spring Azure R 1-6; Little Metalmark U 5-10; American Snout R 2-6; Gulf Fritillary C-A 4-11; Zebra Heliconian U 5-10; Variegated Fritillary U 3-12; Phaon Crescent U 3-12; Pearl Crescent C 3-12; Question Mark U 2-9; Mourning Cloak S 2; American Lady U 2-12; Painted Lady U-C 8-11; Red Admiral U 2-9; Mimic S 8; Common Buckeye C-A 3-12; White Peacock R 9; Red-spotted Purple U 3-11; Viceroy U 3-10; Goatweed Leafwing R 4-10; Hackberry Emperor U 4-10; Tawny Emperor U 4-9; Southern Pearly-eye

U 3-11; Creole Pearly-eye U 4-10; Appalachian Brown U 4-10; Gemmed Satyr U 3-9; Carolina Satyr C-A 1-12; Georgia Satyr R 4-10; Little Wood Satyr C 3-5; Common Wood-Nymph C 5-10; Monarch U 1-12; Queen U 8-10; Silver-spotted Skipper R-U 3-11; Long-tailed Skipper C-A 2-10; Dorantes Longtail R 9-11; Southern Cloudywing C 5-10; Northern Cloudywing C 3-10; Confused Cloudywing U 5-10; Sleepy Duskywing U 2-4; Juvenal’s Duskywing C 1-5; Horace’s Duskywing C 2-11; Zarucco Duskywing C 3-11; Wild Indigo Duskywing R 5, 9; Common/White CheckeredSkipper U 3-9; Tropical Checkered-Skipper U 3-11; Swarthy Skipper C 3-10; Clouded Skipper C 3-12; Least Skipper U 5-9; Southern Skipperling U 5-9; Fiery Skipper C 1-12; Dotted Skipper R 9-10; Meske’s Skipper U 5, 9-10; Tawny-edged Skipper U 4-10; Crossline Skipper U 5-6, 9-11; Whirlabout C 1-12; Southern Broken-Dash C 4-10; Northern Broken-Dash U 9-10; Little Glassywing U 4-9; Sachem U 6-10; Delaware Skipper U 4-5, 8-10; Byssus Skipper U 4-10; Zabulon Skipper U 3-6, 9; Yehl Skipper R 9-10; Palmetto Skipper U 6-10; Palatka Skipper R 4-11; Dion Skipper R 4, 9-10; Dun Skipper U 3-11; Lace-winged RoadsideSkipper U 4-6, 8-10; Dusky Roadside-Skipper U 2-4, 8-10; Eufala Skipper U 6-9; Twin-spot Skipper U-C 4-10; Brazilian Skipper R 8-10; Ocola Skipper C-A 7-11; Cofaqui Giant-Skipper R 4-5, 9.

All photographs this article by Bill Berthet, except as indicated

Jeffrey Glassberg

• A thoroughly revised edition of the most comprehensive and authoritative photographic field guide to North American butterflies

• Features color text boxes that highlight information about habitat, food plants, abundance and flight period, and other interesting facts

• An invaluable tool for field identification

Paper $29.95

416 pages. 3,500 color photos and maps. 5 x 8.

Moths of Central and South America, A Study in Beauty and Diversity

Emmet Gowin

“Moths fly by night and Gowin’s project is, at its heart, about drawing his jewels out of the shadows. In this sense, Mariposas Nocturnas returns full circle to the invention of photography itself.”

—Andrea K. Scott, New Yorker

Cloth $49.95

144 pages. 60 color + 10 b/w illus. 11 x 14.

Jeffrey Glassberg

• A completely revised second edition of a groundbreaking guide, featuring hundreds of new species, more than 1,500 new photos, and updated text, maps, and species names

• Now covers almost all Central American species

• The first complete guide to Mexican butterflies

Paper $39.95

304 pages. 3,700+ color photos and maps. 5 x 8.

Keep these confusing possible strays in mind

in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas.

One will not see that which one cannot see. For example, let’s imagine that you live in North Carolina and see the butterfly shown above, near where you live. You’ve seen Great Purple Hairstreaks myriad times, so, while you’ll still enjoy it’s beauty, few people would think that this might be a butterfly species that they hadn’t previously seen.

As it turns out, the butterflies shown on this page are a female (photo 1) and a male (2) White-tipped Greatstreak (Atlides gaumeri) (photos taken July 21, 2003, near Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico and April 28, 2001, Colonias Francisco Barrios, Veracruz, Mexico).

Now, it is incredibly unlikely that a White-tipped Greatstreak would be in North Carolina and even more unlikely that if one

when you’re

by Jeffrey Glassberg

was there, that it had arrived there in a natural manner. However, if you were butterflying in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas, this Mexican species might reasonably stray there.

There are perhaps a hundred Mexican butterfly species that have never been documented as occurring in the United States that, especially with global warming, could reasonably be expected to stray to the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Many of these species are quite distinctive, or closely resemble other rare strays, so that they will attract attention and possible identification.

Other species, including those covered in this article, are confusingly similar to species that are relatively common in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Many, perhaps most, butterfliers would overlook these species, thinking that the first United States record of the species was just another individual of a common species. Hopefully, this article will help!

Large and graceful, Giant Swallowtails are always fun to see. However, in south Texas, one should keep in mind the possibility of Thoas Swallowtails which, to the best of my knowledge, have never been reliably recorded in the United States (all photos of purported U.S. Thoas Swallowtails that I’ve examined have actually been of Giant Swallowtails).

Above, spots on the great majority of Thoas Swallowtails are paler yellow/ cream than they are on Giant Swallowtails. However, as you can see in photo 6, a minority

5: Oct. 27, 1999. Chaparral WMA, LaSalle Co., TX.

6: Oct. 28, 2016. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

7: Oct. 24, 2009. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

spot usually large, sometimes small spot

8: July 25, 2005. Frontera Corozal, Chiapas, Mexico.

9: July 22, 2003. Road to Yaxchilan, Chiapas, Mexico.

10: Aug. 10, 2002. Catemaco, Veracruz, Mexico.

of Giant Swallowtails approach the cream color of Thoas Swallowtails. Still, seeing a Giant Swallowtail with pale cream above should be your clue to look more closely. Next, look at the FW submarginal band. Almost all Thoas Swallowtails have, counting from the bottom of the band, a fourth spot, which is often prominent (see photo 8). About 60% of Giant Swallowtails have only three spots, while about 40% have a small fourth spot (see photo 5). However, two of 93 individuals had prominent fourth spots.

Most importantly, examine the fourth spot of the FW median band (counting from the first spot below the large spot with a “hole” in it). On Giant Swallowtails, this spot is angled outwardly, usually sharply, while on Thoas Swallowtails, this spot is gently curved outwardly (compare photos 5 and 8). Below, one can see the same difference in the shape of the fourth spot in the median band.

Another way that these species can sometimes be distinguished is by the shape of the male abdomens. Giant Swallowtail males have a visible notch by the genital opening while male Thoas Swallowtails have no visible notch. Of course, for this to be useful, one needs to know that one is looking at a male. I don’t know how to distinguish male and female Giant Swallowtails by wing pattern, so one needs to rely on behavior — if the butterfly is mudpuddling or trying to mate with another butterfly, it is almost certainly a male, whereas if it is laying eggs, it is a female.

11: Male. June 1, 1999. Green Gulch, Big Bend NP, Brewster Co., TX.

12: Female. Aug. 13, 2017. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

13: Male. July 17, 2015. Parque Agua Blanca, Tabasco, Mexico.

14: Male. Aug. 6, 2014. Bonampak, Chiapas, Mexico. spot gently curved outwardly

This brings up the last way to differentiate these species: Giant Swallowtails use citrus family plants as caterpillar foodplants while Thoas Swallowtails use piper family plants as caterpillar foodplants. So, if you are lucky enough to see your butterfly laying eggs, that will indicate the species.

In the absence of behavioral clues, I would look to see all Thoas field marks — pale cream color, sharply angled FW median band spot, four strong FW submarginal spots and no notch on the abdomen — before concluding that I was looking at the first Thoas Swallowtail documented as having occurred in the United States.

line continuous

Large Orange Sulphurs and Cloudless Sulphurs are often abundant in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Males are easy to distinguish, because male Large Orange Sulphurs are bright orange above while male Cloudless Sulphurs are lemon yellow. In the LRGV, one should keep in mind Apricot Sulphur, a species not yet recorded from the U.S.

Male Apricot Sulphurs are similar to Large Orange Sulphurs above (compare photos 16 and 20). In the field a clue that one might be looking at an Apricot Sulphur is that Apricot Sulphurs, on average, are larger than are Large Orange Sulphurs and they tend to fly higher above the ground.

Below, male Apricot Sulphurs vary from lightly marked (photo 21) to heavily marked (photo 22), as do male Large Orange Sulphurs. They are distinguished from them by the shape of the FW postmedian line. On male Large Orange Sulphur, this line is continuous, while

on male Apricot Sulphurs, the line is broken at the vein that the comes off of the lower end of the FW cell. There may be other consistent differences, but I don’t see them.

15: Nov. 1, 2013. National Butterfly

16. Aug. 29, 2016. National

17: June 23, 2007. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

18. Oct. 23, 2009. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

19. July 21, 2003. Near Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico.

20. July 25, 2009. Paraje Nuevo, Veracruz, Mexico.

21. July 19, 2003. Rd. to La Union, Chiapas, Mexico.

22. Feb. 3, 2005. La Ceiba, Honduras.

pale spots

Female Apricot Sulphurs could be overlooked as either Cloudless Sulphurs or as Large Orange Sulphurs. Unlike female Large Orange Sulphurs, Apricots have the FW postmedian band broken, as on males. However, female Cloudless Sulphurs also share this feature and above, Apricot Sulphurs vary from off-white to yellow to orange-yellow, as do female Cloudless Sulphurs. Luckily, there are other features that vary.

Apricot Sulphurs almost always have the FW apex darkened, obscuring 1 or 2 of the apical pink/brown spots. I have not yet seen a female Cloudless Sulphur with this feature, but butterfly variation is endless.

Apricot Sulphurs also have a brown/pink band on the HW lower basal area, while on Cloudless Sulphurs the “band” is broken into spots (on Large Orange Sulphurs, it is similar to Apricot Sulphurs).

At the end of the FW cell, Apricot Sulphur females have a dark spot with a

spots

24. Large Orange Sulphur. Nov. 6, 2013. National Butterfly Center, Hidalgo Co., TX.

spot with small pale area

relatively small pale area, while female Cloudless Sulphurs have a thinner dark outline surrounding larger pale spots.

Lastly, the FW cell of Apricot Sulphurs is variably speckled with dark brown scales, while female Cloudless Sulphurs have much paler flocking, if any.

25: Aug. 4, 2002. Teocelo, Veracruz, Mexico.

Julia Heliconians are uncommon but regular and resident in the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Some butterfliers may not be aware of the fact that another heliconian, Least Heliconian, that ranges into northern Mexico, might be mistaken for a female Julia Heliconian.

Least Heliconians average quite a bit smaller than do Julia Heliconians and fly with faster wingbeats, but absolute size is sometimes difficult to gauge in the field while the determination of the rapidity of wingbeats might fly by many observers.

If you get a look at the topside, Least Heliconians have black veining running into the hindwing from the margin as well as a black stripe down the center of the abdomen. Julia Heliconians lack these features.

Below, the bodies of Least Heliconians have the appearance of white spots on black, while the bodies of Julia Heliconians have the appearance of black stripes on white. In addition, Julia Heliconians have a red spot and red streak on their HW and FW respectively and Least Heliconians lack these red elements.

All photos this article by Jeffrey Glassberg, except as indicated.

30: Least

June 29, 2005. Lagunas de Montebello, Chiapas, Mexico.

31. Least Heliconian. Feb. 27, 2017. Canopy Lodge area, Valle de Anton, Panama.

Least Heliconian. July 20, 2005. Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico.

This summer, the National Butterfly Center made a bold decision. In addition to harvesting rain water and wildflower seeds, we decided to harvest the sun. Thanks to a very generous grant from the Green Mountain Energy Sun Club, we are now able to do just that!

As a lean, green, environmental education and conservation agency, the National Butterfly Center is committed to the triad of principles best articulated by ‘reduce, reuse, recycle.’ In this case, we are greatly reducing our use of fossil fuels and our carbon footprint by converting largely to solar power. The 102-panel, 34.17 kilowatt photovoltaic system now located on the roof of the Chrysalis Visitors’ Pavilion will provide almost $250,000 in energy savings and a 50 percent reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. That’s like not driving 80,000 miles every year!

by Marianna Treviño-Wright

Funding this project of the North American Butterfly Association (NABA) is something our members take very seriously, We are charged with being good stewards of member donations and the grants we receive to advance our mission, so the Sun Club® grant is fantastic on many levels. Not only does the Sun Club grant fund the full solar array, permitting, installation, annual maintenance and monitoring, it also reduces our monthly operating budget by cutting our electricity bill in half! We’re excited to educate the public on how to use natural resources responsibly while protecting valuable ecosystems.

“The National Butterfly Center’s focus on environmental education and conservation directly aligns with our mission of providing sustainable solutions that focus on people and the planet,” said Jason Sears, executive director of Green Mountain Energy Sun Club.

The roof of the Visitors Pavilion at the National Butterfly Center now captures the sun. Our energy production and butterfly wingbeats are now synchronized! Nov. 3, 2017.

“We’re proud to support North American Butterfly Association for making a difference at the National Butterfly Center through the use of solar power, while showcasing the positive effects it can have on our planet.”

At the center, many steps have been taken toward increasing sustainability, including the use of rainwater catchment tanks and in-ground composting of organic waste. The solar array, funded by a $90,000 donation from the Sun Club, will be our latest agent of conservation. Each month we will be able to track our electricity usage in kilowatt hours and calculate the carbon that was offset from using solar energy. Visitors to the butterfly center and our website will soon be able to review these figures to gain a better understanding of how solar power reduces CO2 emissions.

Every dollar we save is another dollar available to fund operations. For this reason, we are grateful to the Sun Club, without which this powerful change would not have

happened. We are excited to add a solar energy component to our outreach and education programs, so everyone may understand the positive environmental impact this clean, renewable and readily-available form of energy makes.

We invite you to make a difference in your home and in this world by choosing Green Mountain Energy, available in certain markets throughout Texas, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Massachusetts. As a Green Mountain customer in Texas, you can choose to contribute to the Sun Club for the benefit of nonprofit organizations, like the NBC, by adding a $5 donation to your monthly electricity bill. For more information on the Sun Club or to nominate another nonprofit for a sustainability grant, visit gmesunclub.org. To learn more about Green Mountain and the benefits of renewable energy, visit www.greenmountain. com.

(or how I spent my summer vacation)

by Mark Nelson

Above: A Phoebus Parnassian in segment 2/2.57.3. July 3, 2017.

Left: One encounters spectacular views along many segments of the trail. This view is available along the Collegiate Range western alternative. Segment CW3/0.9. July 20, 2017.

runs about 500 miles north to south roughly along the continental divide of the Rocky Mountains from Denver down to the scenic town of Durango. The trail is divided into 28 segments, each about 20 miles in length (see map on page 45). The Colorado Trail Databook describes these segments and mileage within segments corresponding to certain landmarks. Backpacking the entire length of the Colorado Trail takes approximately one month and provides a great challenge due to large elevation gains and difficult weather.

I had been on shorter jaunts of one to two weeks, but a month-long trip was rather daunting. Recent retirement meant I had the time, and, living in Denver put me close to the start of the trail, I just wasn’t too sure about the desire. There is a difficult balance between the pleasures of the outdoors versus the pain of carrying a heavy load for many miles. To tip the scale towards the hike, I needed some sort of additional reason for the trip, and trying to photodocument butterflies along the trail seemed to be just the ticket!

During my hike I used the CT Databook information to document butterfly locations and recorded that information in the form of Segment number/and mileage within the segment. There’s an option in the Collegiate Range portion of the CT to take either the eastern section or the western section. The western section is relatively new and is designated as CW01-CW05 and is the path I followed the summer of 2017.

For me, the combination of hiking a certain number of miles per day and taking pictures of butterflies was a grand compromise. First up for consideration

was weight (and money). The attempt to minimize pounds carried, led me to the purchase of a relatively inexpensive Panasonic Lumix camera with macro capability. This camera is also small in size and easy to carry. Of course, without a fancy (and heavy) zoom, it’s difficult to obtain good pictures of butterflies without being nearby. You need to get pretty close! The second compromise was miles walked per day. If I spent too much time on butterflies, I’d never make it to Durango (turns out I never did). I tentatively planned on 12 miles per day as my goal. I Figured that mileage would take about six hours, leaving time for my pursuit of butterflies.

After all my preparation and purchasing light weight camping gear

I ended up carrying 34 lbs., including food and water. I left for my trip on July 2nd and immediately at the trail entrance spotted a Silver-Spotted Skipper. But no photo evidence was obtained! It was difficult to get pictures. My estimate is that only about 10% of attempts resulted in a successful photograph. Early on, my excitement would lead me to quickly jettison my trekking poles as I fumbled for the camera. Often frightening the subject when the poles hit the ground.

Miles walked per day changed in erratic ways as fire closures and gloomy rainy days convinced me to walk from 0 to 29 miles per day on different occasions! It was interesting how my butterfly perspective allowed me to enjoy a particular Segment that repulsed (perhaps

Above left: Bramble Hairstreaks were abundant in Segment 2. On July 3, it almost seemed as though I was tripping over them.

Above right: An Arctic Blue seen just below Hope Pass. July 17, 2017. Segment CW1/7.4.

Opposite page: A common butterfly along the trail, this Variable Checkerspot was spotted in Segment 4 on July 5, 2017, nectaring at a species of four-nerve daisy.

too strong a word) most hikers. Segment 2 was burned in the 1996 Buffalo Creek Fire. Most hikers complain about the absence of cover (and lack of water), but I had a great time! Flowers were incredibly plentiful, as were butterflies.

In some segments, the denseness of trees inhibited butterfly activity. This seemed to be the case in Segment 3, where it wasn’t until a I encountered a meadow near the end of the segment, that butterflies were seen.

I was usually on the move by 6 am and butterflies would typically be stirring by about 8:30. Often, I would set up camp by 2 in the afternoon allowing for more “focused” photo attempts. Whether hiking or camping, Variable Checkerspots were among the more common butterflies I

encountered along the trail.

If weather was suitable, butterflies were abundant in areas such as Hope Pass, Lake Ann Pass, or near the Monarch Ski Area at elevations around 12,000 feet

Sometimes the best photo opportunities corresponded with storms arriving on the scene. Butterflies would usually stop moving under these conditions. At about 4 pm one afternoon the weather was turning cold and windy and the sky was getting darker. I saw a Hoary Comma fluttering near the ground. It then landed upside down on an old bristlecone pine cone in a tree. Pretty good camouflage! It would not depart from that spot despite me rustling branches as I attempted to obtain better shots. It seemed to be asleep.

This beautiful spot was along Segment 24/11.6 in the San Juan Mountains. Aug. 4, 2017.

I decided to end my trip early on August 5th and climbed up one more pass (Molas) where I hitched a ride into Silverton. I thought it would be fun to end the trip with a train ride through the Animas River Canyon into the town of Durango.

I didn’t really need to finish hiking the Colorado Trail in order to complete my trip. The weather also seemed increasingly inclement and not suitable for obtaining photographs of butterflies. Not that suitable for me either! Sitting through

Above: The never-ending trail at Segment 18/11.0. July 27, 2017.

Left: A Taxiles Skipper, the first butterfly photographed by the author. Segment 1/7.0. July 2, 2017.

a hail storm at 13,000 feet convinced me of that.

Taking everything together (including all the great folks I met along the trail) it was a good way to spend a month during the summer. While my efforts were limited by weather and schedule, it seems I documented around 40 different species during my trail time. For sure this is a fraction of the whole, and it would take a lot more study time to thoroughly document the butterflies of the CT. Maybe next summer?

Left: A common Ringlet was nectaring at a Blackeyed Susan on July 4, 2017 in Segment 3/11.9

Below: A map of the Colorado Trail, showing the location of segments.

wasp species showed two species — red paper wasp (Polistes carolina) and metric paper wasp (Polistes metricus) were participants in the attack on the caterpillar.

A few days later another Monarch (possibly a second generation butterfly) was noticed laying eggs on a nearby Butterfly Milkweed. Inspection of it and a few other Butterfly Milkweeds revealed a few caterpillars and the documentation process was again begun. The caterpillar chosen for a resumption of the documentation was already sizable, presumably a fifth instar. Once again, the host plant was netted, but this time only a single stem was within the net so that a tighter seal could be obtained near the base of the stem. Two days later the caterpillar stopped eating and began wandering about. It was taken inside to avoid any potential wasp attacks. A “J” was formed on May 9 and a chrysalis on May 10. The butterfly emerged on May 18. Based on the time required to go from egg to caterpillar to its untimely demise (21 days) and the time for the second caterpillar to form a chrysalis and subsequent butterfly (8 days), the entire cycle from egg hatch to butterfly was completed in approximately 30 days. The adult Monarch was returned to another milkweed in the garden near its origin.

Above: A drawing of the range where Monarchs are found. Purple indicates two broods. Orange indicates three broods. (drawing from the second edition of A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

Opposite page

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Butterfly Milkweed, based upon county occurrence data from the Biota of North America Program. This might be a useful plant for your garden if you live within the range shown.

Top: A mating pair of Guava Skippers. Nov. 22, 2009. Hidalgo Co., TX.

Bottom: A Guava tree in the author’s yard. April 27, 2007.

by Don Dubois

On their journey north, every spring, Monarchs pass through Texas, a critical area on their migratory pathway. Awaiting their arrival in the greater Houston area are several milkweed species, including Butterfly Milkweed. While some state that Butterfly Milkweed is not much used due a lower level of chemical protection from predators and rough leaves that are difficult for young caterpillars to eat, Monarchs frequently use this important caterpillar foodplant in the Houston area.

On April 8, 2016 eggs were spotted on Butterfly Milkweed in my garden and the entire plant was sleeved with a five-gallon paint strainer to thwart the red paper wasps which relentlessly patrol for caterpillars and the parasitic flies which lay their eggs on the defenseless young caterpillars. On April 12, two tiny caterpillars were seen. Photos were taken periodically to monitor progress.

Opposite page

Top left: Newly emerged caterpillars. April 12, 2016.

Top right: A caterpillar grows. April 20, 2016.

Bottom left: The caterpillar has grown much larger. April 25, 2016.

Bottom right: The caterpillar was almost ready to pupate, but was killed by wasps. April 28, 2016.

This page

Top left: A new caterpillar was discovered that was at about the same stage has the first caterpillar. Newly emerged caterpillars. May 8, 2016.

Top right: This caterpillar soon pupated. May 10, 2016.

On April 18, only one caterpillar could be found during a search of the host plant. A few days later the second caterpillar reappeared — apparently it had been well hidden in spite of its colorful markings. It was removed and placed on another milkweed to ensure sufficient food for the first caterpillar. By April 28 the caterpillar had made its final molt and was fat and happy. It had consumed all the flower buds and most of the tender leaves near the top of the plant.

On the morning of April 29 the caterpillar was restless, presumably preparing for the transition to a chrysalis. A check later in the day was unsettling. The net bag was filled with six buzzing wasps, which had apparently eaten the caterpillar. The wasps were dispatched by crushing them but there was no trace of the caterpillar. The wasps had entered the net bag at the base of the plant, where there was a crevice between the two stems of the milkweed. It was not anticipated that wasps would be able to locate such a small opening but obviously they did. What attracted their attention is not known, perhaps the gut-cleansing purge before forming a chrysalis. A tentative identification of the

wasp species showed two species — red paper wasp (Polistes carolina) and metric paper wasp (Polistes metricus) were participants in the attack on the caterpillar.

A few days later another Monarch (possibly a second generation butterfly) was noticed laying eggs on a nearby Butterfly Milkweed. Inspection of it and a few other Butterfly Milkweeds revealed a few caterpillars and the documentation process was again begun. The caterpillar chosen for a resumption of the documentation was already sizable, presumably a fifth instar. Once again, the host plant was netted, but this time only a single stem was within the net so that a tighter seal could be obtained near the base of the stem. Two days later the caterpillar stopped eating and began wandering about. It was taken inside to avoid any potential wasp attacks. A “J” was formed on May 9 and a chrysalis on May 10. The butterfly emerged on May 18. Based on the time required to go from egg to caterpillar to its untimely demise (21 days) and the time for the second caterpillar to form a chrysalis and subsequent butterfly (8 days), the entire cycle from egg hatch to butterfly was completed in approximately 30 days. The adult Monarch was returned to another milkweed in the garden near its origin.

Above: A drawing of the range where Eastern Monarchs are found. Purple indicates two broods. Orange indicates three broods. (drawing from the second edition of A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

Opposite page

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Butterfly Milkweed, based upon county occurrence data from the Biota of North America Program. This might be a useful plant for your garden if you live within the range shown.

Top: A mating pair of Guava Skippers. Nov. 22, 2009. Hidalgo Co., TX.

Bottom: A Guava tree in the author’s yard. April 27, 2007.

by Jan Dauphin

Top left: A Guava Skipper was observed laying eggs on the Guava Tree in the author’s yard. Oct. 25, 2014.

Top right: Day 8 from when the egg was laid. Nov. 1, 2014. At this point, the outer shell was separating from the rest of the red egg.

Bottom: The caterpillar hatched on Day 10 and was about 3 mm in length. Nov. 3, 2014.

Day-37 The refugium was opened to measure the caterpillar. The caterpillar was 10mm long. Nov. 30, 2014.

are fairly common in the Lower Rio Grande Valley (LRGV) of South Texas. The trick to easily locate them is to know where their caterpillar host/food plants, Guava, can be found. They are beautiful spreadwing skippers, quite large, and well-marked.

On Oct. 25, 2014, I observed a Guava Skipper laying eggs on the Guava that we have in our front yard. We have raised many Guava Skippers on this tree in the past, but I had never wanted to take the time to do a life history of a Guava Skipper, before. The difficulty with this critter is that it uses a tree, which means a lot of the study would have to take place outdoors. Also, the caterpillar protects itself inside a refugium, so if you

want to see the caterpillar, you have to open the refugium. This means the caterpillar has to go through the slow process of closing the refugium, each time it is opened.

Also, the leaves where the caterpillar is working must be contained inside some sort of netting, to keep out wasps and other insects. We had a great, wet winter in the LRGV on 2014. We also had several cool, even cold days that year. I was always concerned that when I opened the refugium in wet or cold weather, the naturally sluggish caterpillar might not be able to enclose itself inside the shelter, and I would lose the caterpillar.

The caterpillar never went into true diapause, but there were several days in a row

Opposite page

This page

Left: When one is engaged in an exciting activity, it’s always smart to use protection. Feb. 8, 2015.

Right: The caterpillar eventually pupated on Feb. 18, 2015. This photos was taken on Day-127 from when the egg was laid. Feb. 28, 2015.

Top: Day-54 from when the egg was laid. The caterpillar was 18mm long with yellow rings. Dec 17, 2014.

Bottom: Day-107 from when the egg was laid. The caterpillar was 40mm long. There was no change in the appearance of the caterpillar, until today. The caterpillar is covered in a snow white pruinescence. Feb. 8, 2015.

This page

Above: 134 days from when the egg was laid, the adult emerged from the chrysalis. March 7, 2015.

Right: The underside of the same individual. March 7, 2015.

Opposite page

A second Guava Skipper emerged earlier, on March 1, 2015. It took only a few minutes to unfurl its wings.

that the caterpillar did not grow at all. The caterpillar was in no way a voracious eater. As a matter of fact it ate very little. A couple of Guava farmers I know say they would never waste money on pesticides for their Guavas, because the caterpillars must eat very little. The Guava Skipper feeds late at night, not

during the day. If one did not recognize the refugiums, one might not even know there were caterpillars on the Guava.

After a time, a pure white pruinescence formed on the caterpillar and remained for a few days, until it formed a pupa. It took a long time from egg-laying to butterfly emergence. We did, indeed, have to buy a second Guava for the caterpillar! We kept this one in the house to prevent losing leaves and to try to keep the skipper from going into diapause.

From egg to emergence took 134 days. One huge disappointment: I looked at the chrysalis, checking for the butterfly to emerge. I looked again ~4 minutes later, and the butterfly was out and its wings were already about dried! It must have emerged as soon as I had turned away! Fortunately, I had been keeping track of a second Guava Skipper, whose egg was laid the same day as my study skipper. I did capture its emergence, so I used 5 photos from that butterfly, just to show how fast the process is from emergence to wings dried.

Above: A drawing of the range where Guava Skippers are found. Orange indicates three broods. (drawing from the second edition of A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

Above: A drawing of the approximate occurrence of human-planted Guava in the U.S., based upon data from the USDA and personal experience. Although planted in Florida and Louisiana, Guava Skippers, a Mexican species, only occur in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas.

(

Above: Bermudagrass in the author’s yard. July 28, 2008.

Right: A Southern Skipperling laid an egg on Bermudagrass in the author’s yard. Apr. 23, 2011.

by Jan Dauphin

is abundant throughout most of Texas and all of the Lower Rio Grande Valley. It is a caterpillar foodplant for Southern Skipperlings and for many other grass-skippers and spreadwing skippers.

On April 23, 2011, I observed a Southern Skipperling lay a single egg on Bermudagrass. I collected the blade of grass and brought it inside to begin a 45-day life-cycle study of this species.

Top: Day-5 from when the egg was laid. The caterpillar has fully eclosed and has eaten most of the egg casing. The caterpillar is 1.5mm long. Apr. 28, 2011.

Above left: Day-17. The caterpillar is 8 mm long. May 10, 2011.

Above right: Day-33. The caterpillar is 19mm long. May 26, 2011.

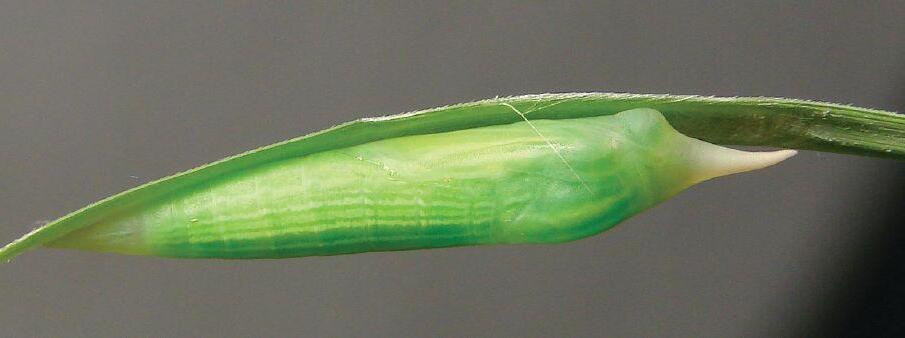

Top: Day-36. The caterpillar has just formed its chrysalis. The caterpillar never formed a “J”. Note the unusual point on the end of the chrysalis. May 29, 2011.

Middle: Day-40. The butterfly’s wings can be seen. June 2, 2011.

Bottom: Day-44. The chrysalis had darkened, considerably. June 6, 2011.

Day-45. The adult butterfly emerged and was released back into the garden. June 7, 2011.

Above: A drawing of the range of Southern Skipperling. Cherry spots indicate areas where the species has strayed, turquoise indicates one brood, purple indicates two broods, orange indicates three brood. (map from the second edition of A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America).

Above: A drawing of the approximate range of Bermudagrass. Although used by numbers of skippers, you might not want this non-native grass in your garden.

On a sun-filled afternoon in the spring, a wasp met a painted lady... (see the spring 2025 issue for the rest of the story.)

July 26, 2017. Gwinnet Co., GA.

Western butterflies sightings of note included May 4 reports from Rob Santry of 20 species, including 25 California Crescents, seen along Ash Creek - 5 miles west of Interstate 5 at the Klammath River, Siskiyou Co., CA, and from Venice Kelly of eight species, including Sara Orangetip, Sheridan’s Hairstreak, Brown Elfin, and Hoary Elfin in Bridge Meadow (8500 ft.) between Mud Lake and Caribou Open Space 2 miles north of Nederland, Boulder Co., CO. On May 14, Georgia Spoonemore saw a Soapberry Hairstreak at Waurika Lake, East Shore Circle, Jefferson Co., OK, While on May 17 William D. Beck reported five Ilavia Hairstreaks at the edge of Highway 60 mp 266 nr Jones Water Campground, Gila Co., AZ. A May 22 submission by Brett Badeaux from Silverado Canyon, Orange Co., CA listed 32 species including Tailed Copper, Goldhunter’s Hairstreak, Mountain Mahogany Hairsteak, Hedgerow Hairstreak, Squarespotted Blue, and Gabb’s Checkerspot.

On June 3, John Heyse saw four species of swallowtails in his yard in Crockett, Contra Costa Co., CA for the first time; Pipevine, Western Tiger, Anise, and Two-tailed; on June 4, Dennis Holmes reported 17 species in Manton, Shasta Co., CA; on June 15 Randy Harrod reported two lifers, a Juniper Hairstreak and an Umber Skipper in Calaveras Big Trees State Park, Calaveras Co., CA; Rob Santry also had two lifers, a Common Alpine and Silver-bordered Fritillary, on June 24 in Ochoco National Forest - Big Summit Prairie, Crook, Co., OR.

On July 1, Ken Wilson and Ray Bruun observed hundreds of Behr’s Hairstreaks on Peavine Rd up to 6850 feet elevation, Reno,

by Michael Reese

Butterflies are beautiful, flowers are beautiful, together, they are beauuuutiful!

Opposite page

Top

Two-tailed Swallowtails love thistles. This one was nectaring at Scotch Cottonthistle on June 4, 2017 at Manton, Shasta Co., CA.

Opposite page

Bottom

‘Sweadner’s’ Juniper Hairstreak and Romerillo Beggarticks just feel right together. Come to the NABA Biennial Members Meeting this September and you may be able to create your own artful photo. Sept. 26, 2017. Jennings SF, Clay Co., FL.

Washoe Co., NV. David H. Bartholomew reported “ hundreds upon hundreds” of Golden Hairstreaks” at the Long Ridge Open Space Preserve, San Mateo Co., CA on July 7. Brant Reif, on July 10, along the Beehive Basin Trail near the Big Sky Ski Resort, Madison Co., MT reported 17 species including Christina’s Sulphur, Relict Fritillary, Hayden’s Ringlet, and Grizzled Skipper.

On Aug. 19, Jeanette Klodzen, along Otter Creek, five miles north of Koosharem, Sevier Co., UT saw eight lifer Nokomis Fritillaries.

On Sept. 2 Venice Kelly reported 20 Green Commas in the James Peak Wilderness east portal, Gilpin Co., CO.

Sightings that mentioned snow (Cold Seens?) included a June 7 report by Jeanette Klodzen on the Twin Lakes Trail from Big Cottonwood Canyon, UT (8700-9449 ft.) of two Milbert’s Tortoiseshells despite the upper half of the trail being snow-covered. Snow was still present at 7000 ft. in various locations including Soda Springs and Donner Summit, CA on June 30 when Ken Wilson saw 17 species of butterflies including Clodius Parnassian, Lustrous Copper, Edith’s Copper, Sylvan Hairstreak, and Dotted Blue, Dennis Holmes on July 25 reported 11 species including 30 Greenish Blues at Lassen NP just above the Sulphur Works, CA despite “snow everywhere”, and on October 19 Venice Kelly found a Painted Lady and a Reakirt’s Blue at 8300 ft. less than a week after a couple days of snow on Farrell Drive 2 miles west of Pinecliffe, CO.

Interesting Texas reports include a May 5 report of 18 species including Sandia Hairstreak, Bromeliad Scrub-Hairstreak, Rawson’s Metalmark, and Arizona Skipper from William D. Beck in Big Bend National Park, TX; a May 6 sighting of eight Poling’s Hairstreaks, a rare species, by Ronald Hedden in McKittrick Canyon, TX, and a July 15 report of a Simius Skipper, an unexpected find east of its typical range, by Ronald Hedden in White River Lake, TX. Other Texas sightings include a trio of sightings submitted by Daniel

Opposite page

Top row

Left: Mimics are rare strays to the United States from the West Indies, but the incidence of their occurrence seems to be ticking up. This one was found by Amy Grimm at Bahia Honda SP, Monroe Co., FL on Aug. 28, 2017.

Right: You were a winner if you were bullish on Golden Hairstreaks. David Bartholomew reported hundreds of them on July 7 at the Long Ridge Open Space Preserve in San Mateo Co., CA.

Middle row

California Crescents, usually rare to uncommon, were surprisingly common this year in the Northwest. May 4, 2017. Ash Creek, Siskiyou Co., CA.

Bottom row

Left: One of the few records of a Monk Skipper from extreme northeastern Florida. Oct. 6, 2017. JulingtonDurbin Preserve, Duval Co., FL.

Right: The past few years have seen a large expansion of the range of Funereal Duskywings. The individual shown here is the first record from Minnesota. Aug. 15, 2017. Coldwater Spring, Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, Hennepin Co., MN.

Jones including an August 27 sighting of 40 species including Ornythion Swallowtail, Statira Sulphur, Dingy Purplewing, and Manybanded Daggerwing at the National Butterfly Center, Mission, TX; an October 3 sighting of 38 species including a Gold-spotted Aguna in his Progresso Lakes Yard; and on October 14, 45 species, a new high for his yard in Progresso, Hidalgo Co., TX.