The politics of speciesism: Animal Agriculture as a global Priority Problem

Abstract

Throughout the course of human evolution, significant milestones have been accomplished by revolutionary shifts. While scientific and technological advancements have propelled us forward in terms of knowledge, innovation, and material progress, they have not always been accompanied by proportional moral progress. A good example to illustrate this claim is the agricultural revolution, which, despite being a salient solution for its time, neglected fundamental issues that have become pressing moral problems of our present with potential existential risks for the future, such as the case of climate change. Applying expected value maximization style reasoning, this paper hopes to provide sound arguments in favour of considering Factory Farming as a global priority problem. Therefore, I make a case for rapid animal agriculture phaseout as an effective intervention to tackle this problem.

Furthermore, Icontend thatforhumanitytofurtherprogressandchange thetrajectory ofhistory, the next fundamental change must be a moral one. In this respect, amidst moral uncertainty, I argue that moral circle expansion is a highly effective strategy to tackle this change. Finally, I explore other promising strategies such as global policy change as an impactful approach to reshaping the fundamentalstructure ofourfood system, and significantly impacting our moral trajectory.

Keywords: axiology, animal ethics, decision theory, climate change, global priority problem, factory farming.

Introduction

Why is animal agriculture a global priority problem?

1. On the equal consideration of nonhuman animals

1.1.Human Exceptionalism

1.2.On Sentience

1.3.Nonhuman Personhood

1.4.Utilitarian Animal Ethics

2. Problematizing Factory farming

2.1.Definition and Scope of Factory Farming

2.2.Ethical, Environmental, and public health consequences

2.3.Expected Value of Ending Factory Farming

3. Effective Trajectory Change

3.1.Moral circle expansion

3.2.Lobbing Global Policy Change

Conclusion

References

Introduction

Animal agriculture is an unsustainable practice that is causing unprecedented harm to our planet and its inhabitants. If we understand the ecological crisis as a pressing problem of the twenty-first century - is it not urgent to begin discussing the interests of those with whom we share our ecosystem? Doing so would not only help us obtain a comprehensive solution to a complex problem but integrate the reciprocal needs of other beings hitherto silenced. Such dialogue is integral to shake previously held truths and certainties such that we might build a more solid foundation from which we can reform our attitudes, degrees of tolerance and ability to coexist respectfully - as has already been proven the case with issues of class, race, gender, and sexual minorities.

Though the politics that inform our behaviours remain deeply entrenched, there is a growing understanding that our own survival and well-being is contingent on a mutually dependent existence with other species. By revaluating the cognitive biases that influence power dynamics, we can expand our moral circle, taking a fundamental step towards a more sustainable and compassionate future for both humans and nonhumans. This paper critically examines the ethical, environmental, and global health consequences associated with factory farming. In doing so, it proposes impactful strategies to address these pressing issues.

I commence by advocating for the equal moral consideration of nonhuman animals, drawing upon perspectives from both normative ethics and applied ethics. With the establishment of this foundation for equalmoralconsideration, Ithen delveintotheethical implications stemmingfromanimal farming practices and the environmental concerns intertwined with them.

I utilizefundamentalconcepts ofutilitytheorytoelucidatethe expectedvalueassociatedwithceasinganimal farming as opposed to its continuation. I also employ the SPC framework to estimate the instrumental value of historical or future events. Additionally, I proposethat factory farmingcan have far-reaching effects, such as the perpetuation of immoral value credence. Furthermore, I argue that for humanity to progress and alter the course of history, a moral revolution is necessary. In this context, amidst moral uncertainty, I contend that expanding our moral circle is a highly effective strategy for driving such change. Finally, I explore global policy change as a impactful approach to reshape the fundamental structure of our food system and significantly influence our moral trajectory. By combining moral circle expansion and policy change, my aim is to present compelling arguments that position factory farming as a pressing problem of our timeand highlightalternative paths forindividuals and societytocontributetothistransformative shift.Lastly, thisresearchaimstoaddress thefollowingquestions:

• Is animal agriculture a global priority problem?

• Do animals matter morally?

• What is the expected value of ending factory farming?

• How can this research influence epistemic and institutional decision-making to blueprint a food system free of animal exploitation?

Methodologically, this research takes a qualitative approach and employs expected value maximization reasoning along with basic notions of decision theory. It draws on interdisciplinary literature encompassing animal ethics, sociology, ethical theory, history, and decision-making theory, integrating key concepts of utility theory.

Our world is confronted with numerous urgent challenges, and determining which ones to prioritize is an ongoing endeavour. With the ever-evolving nature of society, problems that were once deemed critical may have lost their urgency, while previously unnoticed issues may have gained significance as potential existential threats. To address this complexity, various interdisciplinary research bodies worldwide are actively exploring how to effectively prioritize these problems. Among some of the notable organizations engaged in this pursuit, The Global Priorities Institute an interdisciplinary Research Centre at the University of Oxford employs the tools of multiple academic disciplines, especially philosophy, and economics, to inform the decisions of those who want to better the world.1 In the same quest, Open Philanthropy a research and grant making foundation dedicated to allocating resources to the causes that are in most need of attention has developed a framework to identify causes that should be prioritized based on three key criteria: importance, tractability, and neglectedness. 2 Importance refers to the scale of the problem being addressed, tractability assesses the ease of solving the problem, and neglectedness evaluates the current allocation of resources towards the problem. This framework has been refined and further enhanced through collaboration with the Future of Humanity Institute, a research group at the University of Oxford that offers guidance to policy-makers and influential decision-makers on global prioritization. These institutions prioritize projects that go beyond conventional academic research and directly address the most crucial considerations that actors seeking to create the greatest good must confront. By employing these frameworks and collaborating with leading research institutions, these organizations aimto identifyand supportinitiativesthatcanmake a unique and substantial contribution, addressing gaps that would otherwise remain unattended.3 Among the global priority problems identified by these andmany other organizations, climate change stands out, while Factory Farming is considered a very important neglected problem 4 In this paper, however, I argue that Factory Farming is a global priority problem for two main reasons: first, due to its large impact on climate change, and second, due to its unprecedented scale and intensity of suffering involved for nonhuman animals In the forthcoming chapters, I will address these complex issues in greater detail.

1 Greaves, Hilary, et al. "Aresearch agenda for the Global Priorities Institute Version 2.1."

2 Philanthropy, Open. "Cause selection." (2022)

3 Greaves, Hilary, et al. "GLOBAL PRIORITIES INSTITUTE." (2017).

4 Wiblin, Rob. "Aframework for comparing global problems in terms of expected impact." 80,000 Hours (2016).

2. On the Equal Consideration of Animals

2.1. Human Exceptionalism

Granting nonhuman animals equal moral consideration is an ongoing discussion At its core lies the ubiquitous credence of human exceptionalism The relationship among these two topics serves as foundational basis for this subchapter. Human exceptionalism is a widespread assumption to which people commonly adhere to without any valid scientific rationale. It contends that human beings, in relation to the natural world, possess unique and superior qualities that warrant special considerations based on their distinctiveness Among these special considerations, moral value is the central focus of my interest due to the ethical implications that arise from this assumption. An example of my concern is illustrated as it follows:

H Human beings are exceptional

P(H) Humans should be prioritized due to their fundamental moral value.

¬H → ¬M(A) nonhuman animals are not human beings; therefore, they may be morally disregarded

The logical consequence presents the following problems.

Firstly, the proposition ‘H: If Human beings are exceptional’ assumes that human beings are exceptional, without offering any justification for the conclusion.

Secondly, the proposition (H: If Human beings are exceptional) moves from descriptive claims to prescriptive statements (P(H): Humans should be prioritizeddue to their fundamental moral value), without sufficient justification The mere fact that human beings are exceptional does not automatically imply that they should be prioritized morally.

Thirdly, is that ¬H → ¬M(A) nonhuman animals may be morally disregarded based solely on the fact that they are not human beings. Such generalization dismisses the possibility that nonhuman animals might possess inherent moral value or other relevant characteristics that warrant moral consideration.

Additionally, I would like to reflect on the Appeal to Tradition fallacy which consists of justifying an argument based only on the grounds of tradition The risk of such reasoning is that it disregards the possibilities for criticalevaluation andchallenge ofthe status quo while reinforcingthecredence of tradition as an admissible argument.

Despite ofarriving to poorly justified or faulty reasoned conclusions, such ideas constitute a ubiquitous state of affairs. Some might argue that the inferences I have provided, are simplistic and that therefore overlook the ‘big picture’. I will get on to this shortly Until now, my purpose has been merely to illustrate the first stage of an average discussion when most people are asked if animals are worthy of moral consideration. While some might resonate with human exceptionalism credence, they would argue that determining whether animals deserve moral consideration depends on the supportive arguments for such claims. In this respect, I like to begin by stating that a being worthy of moral consideration is one that can be subjected to harm or injustice. It is thought that only humans are capable of recognizing moral claims, and therefore are

the only ones who may claim such considerations.5 However, the fact that animals can experience moral wrongs, despite of not being capable to recognize moral claims, challenges the assumption that moral consideration is solely contingent upon the ability to comprehend and assert moral entitlements We might wish to know to what kind of moral wrongs can nonhuman animals be subjected to? And how in fact can it be proven that have the capacity to undergo such experiences?

To answer the first question, there are many moral wrongs that animals are subjected to Some such as captivity, cruelty, physicaland psychological abuse, neglect, and death, aremoreevident. While others, such as separation from families, deprivation from forming social bonds, rest, play, and learn, tend to be overlooked.6 If animals can experience moral wrongs, they can also experience moral goods While animals cannot assert moral entitlements in the way humans do, theircapacity to experience positive states and wellbeing calls for a consideration of their interests and the moral implications of our actions towards them. All the kinds of moral wrongs aforementioned, are howevernot exclusive to animals, but extended to human beings. Just like human beings, nonhuman animals are social, intelligent, and curious beings who experience pain and pleasure, and therefore, it is in their interest to avoid being subjected to wrongs. However, animal interests complicate thediscussion becauseof apotential conflictof interests. Forexample, in the case of Factory farming, the interest of animal to not be harmed contest the interest of the human that wishes to eat them. In an attempt to mitigate the wrongs, either to animals, or to their own sense of morality, humans might argue in favour of humane Factory farming, yet such idea is dissonant with the very notion of Factory Farming. I will provide further elaboration on this matter in the following chapter.

The second question prompts up to ponder how can we prove that in fact, human beings have the capacity to be wronged? Some would argue, that human ability to communicate about their internal states is one of the grounds that can serve as ‘proof’. However, black slaves, in spite of being equally able to communicate, were too, denied moral consideration. Slave owners, argued that because of their race, slaves were inferior morally and intellectually to white people 7 Comparatively, throughout history, a similar logic, or lack thereof, has been extended to women, Jewish and many other oppressed groups who have contested being subjected to harm and injustice. These instances indicate that the reasons why groups oppress others, have less to do with sound arguments and more to do with the exercise of power. Like white supremacists, human beings, resource to the argument of human supremacy over the natural world, demanding from those who challenge the status quo, to prove such claims.

2.2. On Sentience

Intelligence and consciousness have long been argued as exclusive to humans. In this regard, influential thinkers, sucha René Descartes, have contributed to shape misconceptions regardingthecapacity ofanimals to suffer and experience more complex emotions.

Descartes, a philosopher, and mathematician who lived in the 17th century, proposed a mechanistic view of animals, suggesting that they were like automatons or machines. Descartes, referred to animals as brutes, and as such they could not reason. Instead, their behaviours and reactions could be explained through purely mechanical processes, thus, suffering and consciousness were exclusive to human beings Descartes developed the theory of dualism, which classified mental phenomena as nonphysical and therefore nonspatial. According to his theory, the brain and the mind were two separate substances. To Descartes, the

5 Horta, Oscar. "The Moral Status ofAnimals." The International Encyclopedia of Ethics (2013).

6 Singer, Peter. "Animal liberation or animal rights?." The Monist 70.1 (1987): 3-14.

7 Gordon-Reed,Annette. "America's original sin: Slavery and the legacy of white supremacy." Foreign Aff. 97 (2018): 2.

scope of science could not reach the intricacies of the mind and should only be limited to the physical world

The mind, however, pertained to the realm of philosophy.

Despite of having shaped our notion of consciousness, both for human and nonhuman animals, many of Descartes's views have been refuted and contested in recent decades, scholars and scientists have begun to move toward a science of consciousness. In this sense, empirical evidence indicates that a wide range of animals are in fact intelligent and display rational thinking.8 The issue of consciousness is an evolving, vast, and complex field that is reaching unprecedented growth. This growth is attributed to the interdisciplinary collaboration and efforts of scientists and scholars In a general sense, consciousness refers to the state of being aware of one's own existence, sensations, thoughts, and surroundings. Animal consciousness has been researched for over one hundred years and there is growing evidence that human beings are not the only species who have the neurophysiological substrates that generate consciousness9 . On July 7th, 2021, a prominent international group of cognitive neuroscientists, neuropharmacologists, neurophysiologists, neuroanatomists and computational neuroscientists gathered at The University of Cambridge to reassess the neurobiological substrates of conscious experience and related behaviours in human and non-human animals10 During this conference known as The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, it was postulated that:

‘Convergent evidence indicates that non-human animals have the neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and neurophysiological substrates of conscious states along with the capacity to exhibit intentional behaviours. Consequently, the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.”11

The study of consciousness is fascinating and relevant in understanding not only our own nature but also the nature of other beings that evolved thousands of years before us. When considering humans, some of the motivations behind ongoing research on consciousness is to comprehend our capacity for abstract thinking, artisticcreation, meta-cognition, thedevelopment ofcomplex technology, and ultimatelypassing knowledge across generations. Undeniably, humans have extraordinary accomplishments and those differ greatly from animals. However, these differences are irrelevant when considering moral equality, particularly, given the many similarities shared between humans and animals. What aspects shall therefore be considered to establish moral considerability? Some scholars concur that sentience is a valid and succinct basis when extending moral consideration to animals. The general criteria for determining whether a being is sentient involves three considerations: Behavioural, evolutionary, and physiological.12 Sentience, relates to the capacity to have subjective experiences, sensations, or feelings. Studies conclude that both, nonhuman animals and human beings are sentient and experience the world in their own subjective ways. Consequently, to experience subjectivity, one must be subject, however, animals remain legal objects. This determination is based on the notion of personhood, a concept influenced by cultural, philosophical, and

8 Do animals think rationally? Jeannie Kever, 713-743-0778, November 1, 2007

https://www.uh.edu/news-events/stories/2017/november/11012017Buckner-Animal-Cognition.php

9 Low, Philip, et al. "The Cambridge declaration on consciousness." Francis crick memorial conference, Cambridge, England. 2012. 10 11

12 https://www.animal-ethics.org/criteria-for-recognizing-sentience/

legal perspectives. Personhood has traditionally been associated with humans, yet currently, it is debated whether some animals should also be considered persons. An example of such is the case of the Elephant Happy

2.3. Nonhuman persons?

Born in the wilderness of Asia, Happy was brought to the Bronx Zoo and has remained in solitary confinement for fifty years in a 45 sqm exhibit. The legal group Nonhuman Rights Project13, petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus on her behalf, alleging that theirclient Happy is being unlawfullyimprisoned14 The request was to ‘release happy to a sanctuary where her right to liberty will be respected’ This was the first time in history that a nonhuman animal has been represented in court as a legal person15. Arguments in favour of Happy’s attributes for personhood were supported by the world’s five most renowned experts on elephant cognition They provided, conclusive evidence that Happy is an extraordinarily intelligent and autonomous being who possesses advanced analytic abilities akin to human beings’16 After many appeals and more than eighty amici curiae sent to the court by Emeritus Harvard Professors, Buddhist monks and academic Theists, Judge Fahley argued that ‘A determination that Happy, an elephant, may invoke habeas corpus "[...]"would have an enormous destabilizing impact on modern society.’ While the court recognized that happy is not an object, and instead, a sentient, remarkably intelligent being, they also stated that Happy is not a subject and therefore has no rights. The legal system only recognizes human beings as persons and right holders. In the absence of rights and personhood, the court rejected the writ of habeas corpus. Despite of the strong scientific evidence and support from bodies of interdisciplinary academics, appeal to tradition and species membership were the unsatisfying arguments provided by the Supreme Court of the United States. To this day, Happy remains isolated in the Bronx Zoo.

2.4. Utilitarian Animal Ethics

This subchapter presents a shift in the approach to animal ethics, moving away from the traditional perspective of normative ethics. Instead, it advocates for adopting a utilitarian approach in the realm of animal ethics.

In 1970, Richard Ryder, a British psychologist, author, and animal rights advocate, introduced the term "speciesism" to describe a prevalent form of human-cantered prejudice solely based on species membership17 Similar to other types of discrimination such as racism, sexism, classism, and transphobia, speciesism reinforces thebelief inhumansuperiority. Ryderargued that being born Homosapiensis morally irrelevant when determining rights, emphasizing that the capacity to live, suffer, and experience happiness should be the relevant criteria. His perspective aligns with the UN Declaration of Human Rights, which recognizes "inherent dignity and equal and inalienable rights."18 Ryder's contributions have significantly impacted the animal rights movement and animal ethics, influencing subsequent figures like Peter Singer. Peter Singer, a moral utilitarian philosopher specializing in bioethics, further popularized the term "speciesism."While Singer shares Ryder's commitmentto animalliberation, he diverges from Ryder and the 13

14 https://www.nonhumanrights.org/client/happy/

15

16 https://archive.nonhumanrights.org/content/uploads/Happy-Brief.pdf

17 https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-animal/ 18

animal rights movement in the very notion of animal rights

19 Singer's ethical approach is rooted in utilitarianism, focusing on minimizing suffering and maximizing well-being. While the Animal Rights movement condemns killing as morally impermissible, Singer adopts a more nuanced perspective. He challenges the notion that life must be preserved at all costs, particularly for those experiencing extreme pain20. Singer argues that euthanasia and abortion can be more compassionate, humane, and morally justifiable than rigidly preserving life. Consequently, Singer finds welfarism an approach that effectively alleviates suffering acceptable. In this sense, pragmatism and effectiveness are central principles in Singer's applied ethics and utilitarianism in general. Singer emphasizes the importance of practical impact and tangible outcomes in promotinganimal welfare. Utilitarian animal ethics advocates strategic approaches that bring about meaningful change and alleviate animal suffering on a larger scale. These strategies involve supporting initiatives such as reducing animal product consumption, advocating for legislative reforms, and promoting ethical alternatives to animal testing and vivisection. By prioritizing effective strategies, individuals and organizations can make substantial contributions toward improving animal lives and advancing the cause of animal liberation.21

Another key argument in Singer's ethics revolves around are interests. In an ideal moral framework, individuals' equal moral worth would imply an equal value of their interests. However, considering power dynamics, negotiating these interests becomes crucial. For instance, while humans may enjoy the taste of meat and wearing fur and leather, animals desire to live free from suffering. From a standpoint of normative ethics and equal moral consideration, the value of intense suffering cannot be compared to mere pleasure, therefor human beings should stop wearing fur and eating meat. Yet, due to the significant power disparity between humans and nonhumans, it is necessary to acknowledge that, at present, human interests hold more weight. Prioritizing the alleviation of suffering requires finding effective compromises that satisfactorily address the interests of both groups. Thus, a pragmatic approach to changing the status quo should take precedence over an idealistic one, as the latter may prolong suffering and delay progress. 22

3. Problematizing Factory Farming

3.1. Definition and scope of Factory Farming

Throughouthistory, humanbeingshavegrappledwithexistentialquestionsandpoliticaldynamicsthatshape societies and power structures. This influence of politics became particularly significant during the scientific revolution, a transformative period in the 16th and 17th centuries, where empirical observation and reason challenged traditional beliefs. This led to the industrial revolution, marked by societal and economic transformations Politics played a crucial role in shaping the industrial revolution, as governments and policymakers implemented policies to support industrial growth, regulate labour practices, and establish legal frameworks for economic activities.

One significant area that experienced a transformation during the industrial revolution was agriculture. Prior to the industrial revolution, farming practices were predominantly small-scale and labour-intensive, with farmers relying on traditional methods and manual labour to cultivate crops and raise livestock. As the demand for food increased due to the growing urban population and changing dietary habits, farmers sought

19 Singer does not believe animals have rights or moral obligations

20 Peter Singer,Animal liberation, pg18

21 Peter Singer,Animal liberation Pg

22 Tobias Leenaert, towards a vegan world

ways to maximize production The principles of standardization, efficiency, and mass production began to be applied to agriculture. This shift led to what is known today as Factory farming.23

Politics and government policies played a role in facilitating this transition. Governments implemented agricultural policies to support industrialized farming, provided subsidies for mechanization and technological advancements, and established regulations and standards for food production. While industrial agriculture, has created a narrative about the efficiency of animal production by meeting demands of a growing population; it has brought within unprecedented suffering to animals while becoming a culprit of climate change As Tobias Lennaert reflects in ‘How to create a vegan world’ the basis of our society is built in animal consumption 24

3.2. Ethical, Environmental, and public health concerns associated with factory farming.

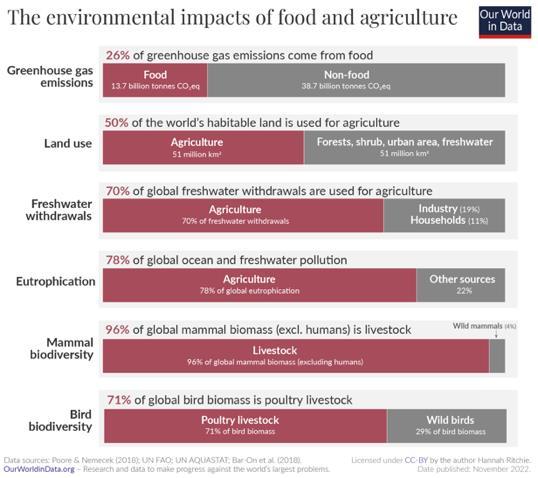

Earth is host to 8 billion human beings who in a year, consume 130 billion nonhuman animals for food.25 This figure includes neither the individuals used in experimentation, transport, entertainment, and hunting; nor the 8.7 million wild nonhuman animals suffering the consequences of the destruction we impart on our ecosystem. According to the UN projections, the world population will have increased more than 10 fold over the span of 250 years; which accounts for 80 billion human beings; a size which compared to humanity’s history will be extraordinary.26 If we assume that the population growth follows a steady linear increase over 250 years, based on these assumptions, it is estimated that 80 billion human beings will approximately consume 9.36 trillion nonhuman animals. Estimating population growth and animal consumption requires complex calculations of an extensive set of variables to predict such projections. Therefore, the aforementioned projection intends only to illustrate the state of affairs regarding animal agriculture today while prompting to consider the possible outcomes for the future. As the following table estimates, Factory Farming is a significant contributor to climate change. It is accountable for 26% of greenhouse gasemissions, itaccounts for 50% of the planet’s land utilized foragriculture, and 70% ofglobal freshwater withdrawals are attributed to agricultural purposes. Moreover, it pollutes 78% of global oceans and freshwater sources.27 Additionally, its inefficient conversion ratio suggests that a substantial reduction in global hunger could be achieved if 35% of the world's grain harvest was directly allocated to human consumption instead of being utilized for livestock rearing.28

The intensive use of resources, such as land, water, and feed, as well as the emission of greenhouse gases, contributes like no other to climate change, deforestation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss. The public health implications of factory farming are also a pressing concern. The concentration of animals in close quarters creates an environment conducive to the spread of diseases, including zoonotic diseases that can transmit from animals to humans.30

Factory farming requires large amounts of feed, water, and land, which could be redirected toward more efficient and sustainable food production methods.31

The disregard for animal sentience allows factory farms to prioritize maximizing output and minimizing costs, resulting in animals enduring excruciating suffering. Animals are treated as machines, subjected to inhumane practices from their breeding to their killing. This raises three areas of significant concern: selective breeding, living conditions, and rearing practices. Selective breeding is problematic because it has created an “extreme organism”32 unable to live normally in its own body33 Chickens amount for 9 billion of the yearly and are the animals that suffer the most. Academics of the University of Arkansas published in a peer-reviewed article published in Poultry Science that “If humans grew at a similar rate, a 3kg (6.6 lb) newborn baby would weigh 300 kg (660 lb) after two months”34

Considering the aforementioned considerations, the concept of factory farming stands in fundamental opposition to the principles of humane farming practices and sustainability. Moreover, I contend that traditional farming practices have limited capacity to meet the demands of a growing population, therefore, in the context of our industrialized society, animal agriculture and factory farming have become closely intertwined, with the latter increasingly dominating the agricultural landscape 29 ourworldindata

32 Dawkins, M. 2012. Breeding for better welfare: genetic goals for broiler chickens and their parents. Animal Welfare. 21(2):147-155.

33 national Chicken Council. 2011. U.s. Broiler performance,1925 to present. http://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/aboutthe-industry/statistics/u-s-broiler-performance/. Accessed January 30, 2014.

34 https://thehumaneleague.org/article/chicken-selectivebreeding#:~:text=In%20the%20poultry%20industry%2C%20commercial,yield%20more%20meat%20or%20eggs

The subsequent subchapter will argue that the perpetuation of this system not only ensures but also exacerbates these detrimental consequences. Furthermore, the discussion will explore the possibilities and challenges of reforming factory farming practices.

3.3. Expected value of Ending factory farming

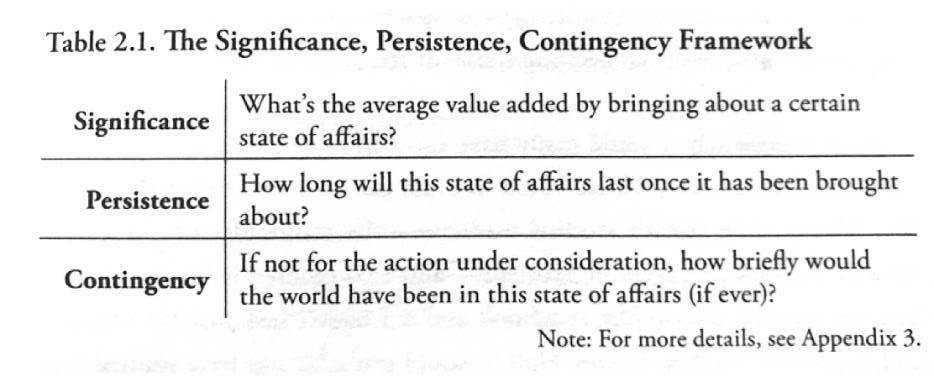

A change of affairs, such as rapid animal agriculture phaseout is undoubtedly a complex quest. Two of the considerable challenges this quest faces are, firstly to estimate the expected value of ending factory farming and secondly, to decide which interventions will have greater impact. When facing uncertainty, decisions can be biased byintuitionsor personal preferences. For instance, someonewho places ahigh valueonanimal welfare might assign a higher utility to ending factory farming than someone who is more concerned about the economicimpact. To address this, a value maximizationapproach can provide a framework for decisionmaking. In this chapter, I will introduce the Significance, Persistence, and Contingency (SPC) framework developed by William MacAskill, Teruji Thomas, and Aaron Vallinder from the Global Priorities Institute at Oxford.

The SPC framework considers the world as a complex entity comprising various features or states of affairs that contribute to its overall value. When assessing the value of each feature, it involves evaluating their significance (average value per unit of time) and persistence (duration). Additionally, it examines the extent to which a particular agent's decision or originating event influences the value of a specific feature by considering counterfactual scenarios.

The aim of this framework is to estimate the expected change in value resulting from an originating event. It formalizes the factors of significance, persistence, and contingency to determine the total value of the world. These factors are evaluatedin relation tothedurationof the feature given the occurrence oftheevent.

“Let ∆V and ∆T be the changes that E makes to V and T , relative to the salient alternative or status quo. Then we can formally define

Sig = ∆V /∆T

Per = T Con=∆T/T.

The product of these three factors is the change in value:

∆V = Sig×Per×Con”36

To qualitatively apply this framework, I will consider the significance, persistence, and contingency factors related to ending factory farming.

Significance of Ending Factory Farming: 37

Animal Suffering: Ending factory farming significantly reduces animal suffering, promoting ethical treatment and compassion.

Global Health: Cessation of factory farming helps mitigate disease risks and zoonotic infections, protecting global health.

Climate Change: Ending factory farming contributes to substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and environmental degradation, mitigating climate change.

Economic Impact: Transitioning away from factory farming presents short-term economic challenges but offers long-term economic benefits and job creation.

Food Security and Resource Efficiency: Ending factory farming allows for more efficient use of resources, promoting food security and sustainable resource management

Persistence of Ending Factory Farming:38

Animal Suffering: Requires ongoing commitment to animal welfare and ethical considerations.

Global Health: Continued efforts in public health initiatives and sustainable farming practices are essential.

Climate Change: Relies on sustained commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and implementing sustainable agriculture practices.

Economic Impact: Depends on the viability and growth of alternative food industries and favorable market conditions.

Food Security and Resource Efficiency: Requires a focus on sustainable farming practices and research for efficient resource management.

Contingency of Ending Factory Farming:39

Animal Suffering: Relies on consumer demand for ethical products and advancements in alternative food production methods.

Global Health: Involves ongoing public health initiatives, policy support, and effective disease prevention measures.

Climate Change: Depends on continued technological advancements, government policies, and global cooperation.

Economic Impact: Hinges on the economic viability of alternative food industries, consumer acceptance, and investment in sustainable practices.

Food Security and Resource Efficiency: Requires research and innovation in sustainable agriculture, resource-efficient farming methods, and policies prioritizing food security.

37 Eisen, Michael B., and Patrick O. Brown. "Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO2 emissions this century." PLoS Climate 1.2 (2022): e0000010.

38Compassion in World Farming. Beyond Factory Farming: Sustainable Solutions for Animals, People and the Planet: A Report by Compassion in World Farming. Compassion in World Farming, 2009..

39 Food and Water Watch. “Factory Farm Map: What’s Wrong with Factory Farms?” FWW, n.d. Retrieved December 6, 2016

Based on the SPC framework, ending factory farming appears to offer greater value maximization in terms of ethical considerations, public health, environmental sustainability, long-term economic benefits, and resource efficiency compared to continuing with it. However, the persistence and contingency factors highlight the need for ongoing efforts in areas such as consumer demand, technological innovation, policy changes, and industry practices. Addressing these factors increases the likelihood of successfully ending factory farming.

Moreover, the expected utility of ending factory farming considers the overall value associated with its cessation, accounting for probabilities of achieving positive outcomes in various aspects. It encompasses benefits related to animal welfare, global health, climate change mitigation, economic advantages, food security, and resource efficiency.

Furthermore, this framework can be applied to climate change as a single feature of the factory farming state of affairs. ‘In general, if some change to the world has at least a reasonable chance being highly significant, persistent, and contingent, then that can be sufficient for the expected value of that change to be very great indeed.’ In this respect, a peer reviewed quantitative research article conducted by Michael B. Eisen andIPatrick O. Brown the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Department of Integrative Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California and the Department of Biochemistry (Emeritus), Stanford University School of Medicine concluded that a rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potentialto stabilizegreenhouse gas levels for30 yearsand offset 68 percent ofCO2 emissions thiscentury40 Finally, Considering the uncertainties surrounding animal suffering and intelligence, the argument to end animal farming as a means to prevent intense suffering is strengthened. If the current trajectory of increasing animal production continues, it may lead to a rise in overall suffering experienced by animals in factory farming. Furthermore, the true extent of animal suffering and its value remains uncertain.

4. Changing the trajectory

4.1. Moral circle expansion

Expanding moral considerations to other groups is not a new concept. What is novel about this argument is its propositionthatdoingsois ahighlyeffectivestrategyforimprovingthe futureofhumansandnonhumans In this chapter I explore the concept of ‘circles of recognition’ proposed by Alessandro Pizzorno in relation with the concept of moral circle expansion introduced by William Edward Hartpole Lecky and popularized by Peter Singer41 It has since been further developed by many scholars.

Alessandro Pizzorno, one the leading figures on contemporary sociological theory, introduced the concept of "circles of recognition"42 to explore identity and social action. Pizzorno's perspective on recognition emphasizes the role of reception and the social performance of identity43 He argued that individuals construct their identities through the recognition they receive from others, fostering a sense of interconnectedness and communication. Moreover, Pizzorno's emphasis on mutual acknowledgment and understanding highlights the importance of recognizing others as part of the shared social fabric. In this

40Eisen, Michael B., and Patrick O. Brown. "Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO2 emissions this century." PLoS Climate 1.2 (2022): e0000010.

sense, his focus on the continuous process of negotiation and adjustment within the circles of recognition aligns with the dynamic nature of moral circle expansion.

Moral circle expansion, involves expanding moral consideration to include more individuals and groups. Identity, as Pizzornoargues, is fundamental toextendmoralconsiderationtoothers, becauseincreasedmoral considerationis usuallygiventomembers ofthesetof individuals who possess a particularattribute. In other words ‘a community of moral agents concludes that a feature on which they previously based the moral inconsiderability of some individuals is not morally relevant Consequently, heightened moral consideration is typically granted to members of a category who possess a specific attribute. Both Singer and Pizzorno argue that moral circles are not fixed or static but can expand or contract depending on various factors such as social norms, cultural values, and political structures.44 Singer argues that our moral circle has been expanding considerably since our hunter gatherer times andthat evidence points to the fact that we areliving in the most peaceful era in human history. Compared to any other time, we are less violent and demonstrate greater care for those around us45 In recent times, Crimston et al have developed scientific methods to measurethis aspectofmoralcognition. The MoralExpansiveness Scale(MES)allows individuals toindicate the entities they include or exclude from their moral circle, providing insights into the extent of moral expansion. Higher scores on the MES are associated with greater prosocial behaviours, such as a willingness to sacrifice for others and engage in volunteering.

This understanding can be useful in discussions surrounding the expansion of our moral circle to include nonhuman animals, as they share features such as intelligence, consciousness, and sentience with us. As explored in Chapter 2, the belief in supremacy undermines the well-being and cohesion of both the excluded ‘others’ and the group itself, as mutual support contributes to the overall welfare of society. The risks of not expanding our moral circle have been experienced throughout history in extreme cases such as Nazism, slavery, and other instances of systemic oppression.

I would liketo argue for the potential of factory farmingto have cascading effectsthatextendto populations, value locking immoral credences for generations. If factory farming extends considerably in time, it might become deeply ingrained in a society, shaping, and reinforcing beliefs, attitudes, and values related to the treatment of animals and others that show features of exclusion. Populations may become "value locked"46 in immoral credences, meaning that they hold beliefs or values that perpetuate or condone practices that are ethicallyproblematic ormorally questionable. Inthecontextof factory farming, this couldinvolve accepting or disregarding the suffering and harm inflicted on animals, neglecting environmental consequences, or prioritizing economic interests over ethical considerations.

The cascading effects of factory farming can also have implications in the development of General Artificial Intelligence (AI). There is a risk that value lock can either stagnate the possibility of moral progress or be replicated in the treatment of human beings by attributing them lesser moral considerations in comparison to AI. 47Therefore, it is important to recognize the potential long-term consequences of value lock associated with neglecting the importance of expanding our moral circle

When considering thetopic ofmoralcircle expansion, the Significance, Persistence, and Contingency (SPC) framework might be a valuable instrumental tool. It not only helps identify interventions with higher effectiveness but also provides insights into the duration of their impact. I contend that moral circle

expansion, when it successfully permeates policies, markets, and culture, can have a profound and enduring influence.

Breaking free from value locked immoral credence requires critical thinking, awareness, education, and a willingness to challenge the status quo. It involves revaluating beliefs, questioning societal norms, and considering alternative perspectives and ethical frameworks. By extending moral consideration to a broader range ofentities, theimpact ofmoral circle expansion can extend beyond individual attitudes and behaviours to shape the very fabric of society. This encompasses the development and implementation of inclusive policies, the transformation of market practices, and the evolution of cultural norms. As a result, the impact of moral circle expansion can be long-lasting and far-reaching.

4.2. Lobbing and Global Policy Change

Whilemy previous subchapteris primarilyarguedfrom anethicalstandpoint, evidence suggeststhatshifting beyond individual advocacy toward institutional change might be a high-impact strategy for the abolition of Factory Farming Inthis sense, thereis a tendency ‘towardthe gradual abandonment of the idea ofnormative ethics and moral truth of any kind and the tendency to emphasize procedures and public policy’ . 48 Governments and businesses have a significant influence in shaping our world. However, it is important to acknowledge that instances of bad governance and unethical business practices are pervasive In our interconnected world, it is crucial for citizens to exercise their rights and take measures to prevent a concentration of arbitrary decision-making power in the hands of a few. Decentralizing knowledge is one promising strategy to regulate stakeholders and governments, as it promotes transparency and helps phase out centralized decision-making processes. In this sense, one effective means of advocating for institutional change and phasing out factory farming is through informed lobbying. Citizens, organizations, and activists caninfluencepolicydecisionsand pushforlegislativereforms thatalignwiththeirethicalandenvironmental concerns by engaging in strategic lobbying efforts. Reclaiming transparency can be a path to phasing out centralized information and, consequently, centralized decision-making processes. Decentralization and community-driven development contribute to effective governance, empowering diverse stakeholders and enabling their meaningful participation in decision-making processes.

The focus of public affairs should be on providing practical solutions based on empirical evidence. Even the most well-crafted and persuasive argument will fail if it is not approached with an emphasis on effectiveness and strategies that yield high impact.

In recent times, there is a growing demand from diverse ONGs which advocate for stimulating higher political participation by offering citizens access to databases containing relevant information used by institutions and governments used to make important decisions, such as funds allocation One salient example of an organization that is focusing on such efforts is g0v movement, or g0v, ‘ a decentralized civic tech community with information transparency, open results, and open cooperation as its core values. g0v engages in public affairs by drawing from the grassroots power of the community.’49 International calls for action and pledges play a vital role in mobilizing political will and driving change. In the case of factory farming, two types of dialogue can be pursued. One involves engaging domestic stakeholders and national governments, while the other involves governments and their international

48 Bishop, Jeffrey P., and Fabrice Jotterand. "Bioethics as biopolitics." Journal of medicine and philosophy 31.3 (2006): 205212.

49 Fan, Fa-ti, et al. "Citizens, politics, and civic technology:Aconversation with g0v and EDGI." East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 13.2 (2019): 279-297.

development partners. These dialogues serve to emphasize the significant political, social, and economic benefits that can be achieved through reducing factory farming. They also remind governments of their obligations under the UN Charter to uphold human rights, including the right to food, and climate change action. As we have explored in earlier chapters, abolishing factory farming holds great potential for mitigating hunger, considering that the conversion rate of calories from grains to meat averages at 70% to 1%.

2016 was a historical year for nonhuman animals when Sentience Politics, a Swiss political organization advocating against speciesism, proposed a ballot initiative in Switzerland to outlaw factory farming, citing its violation of the constitution, and aimed to halt imports of intensively farmed meat. According to polling data, 52% of voters opposed the ban, while 47% were in favor of it. On September 2022, the final results of the participation (as a share of the electorate) revealed a turnout of 52.3%, with 37.1% voting in favor of the initiative. Despite not achieving the majority needed for approval, the initiative's impact was significant as it brought the issue of Factory Farming into the spotlight as a crucial political problem. If the initiative were approved, Switzerland's constitution, already protecting the "welfare and dignity of animals," would be amended to include an animal's right "not to be intensively farmed"

Business initiatives are now providing solutions to address the negative aspects of factory farming while preserving its advantages. This can be accomplished through the development of cultured meats and plantbased foods. One notable effort in this direction is the Protein Directory, a comprehensive and accessible global database of companiesin thealternative protein sector. As of the latest update, the directorylists 1864 such companies operating worldwide.

Moreover, The Good Food Institute50, published a summary of recommended stakeholder actions.

The A life cycle assessment (LCA) and techno-economic assessment TEA reports on commercial cultivated meat production project that by 2030, cultivated meat could

● Reduce global warming impacts by 17%, 52%, and 85-92% compared to conventional chicken, pork, and beef production, respectively. 3

● Is 3.5x more efficient than conventional chicken at converting feed into meat, consequently reducing land use by 63%, 72%, and 81-95% compared to conventional chicken, pork, and beef production, respectively.

● Can becost-competitive, withproductioncosts modelledaslowas $6.43 per kilogram ($2.92perpound).51

The reports represent the first incorporation of data from over 15 industry partners, including five cultivated meat manufacturers, which underscores the significance of collaboration. When compared to optimistic benchmarks for conventional animal agriculture, cultivated meat produced with renewable energy demonstrates a substantial reduction in global warming impacts and land use. As such, stakeholders, including governments, investors, and nonprofits, are encouraged to invest in open-access R&D, implement science-based policies, incentivize new infrastructure, and promote the development of a robust and equitable cultivated meat workforce. These findings highlight the enormous potential of cultivated meat as a sustainable and affordable protein option for the future.

Additionally, it is worth noting that lab-grown meat has received approval for human consumption from both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). In a groundbreakingachievement, CultivatedmeatcompanyUPSIDE Foods hasachievedasignificantmilestone by making its first consumer sale of cultivated meat in the US. These changes are showing an important in shift in society, a shift that would have been unimaginable in different times.

The urgent need to phase out factory farming calls for serious global policy implementation. The world's interdependence on meat exports and imports necessitates immediate action to address this pressing issue.

Food & Water Watch (FWW) released a report titled "The Urgent Case for a Ban on Factory Farms," advocating for policy changes that would halt the growth of factory farms once and for all. The report provides legislative guidance to federal and state governments, urging them to prohibit the expansion of existing factory farms and prevent the construction of new ones.

FWW's proposed ban on new factory farms is just one aspect of a comprehensive approach to mitigating the harmful effects of these operations. It calls for the enforcement and strengthening of existing environmental laws that address agriculture's contribution to climate change. Additionally, FWW recommends directing government spending towards supporting small-scale livestock production and promoting sales in local markets. These policies would encourage diversification in animal farming and facilitate the growth of sustainable and localized food systems.

Local action is a critical driver in curbing the expansion of factory farms. Notable examples include communities in North Carolina using legal avenues to exert pressure on pork Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations throughnuisance cases. Theselegal actions, suchas those against porkproducerMurphy-Brown, highlight the negative impacts endured by communities living near factory farms. Setting a precedent through local pressure empowers other communities across different states to challenge the influence of powerful corporate entities.To stay well-informed and mobilize effectively, FWW offers the Factory Farm Map, a valuable resource that visually depicts the dominance of factory farming in livestock production across the United States.

While the world possesses the necessary resources and technology to transition away from factory farming, it requires the mobilization of political will and the establishment of inclusive institutions. Crucial decisions on investment, resource allocation, and policies related to cultured meats and food security should be driven by the goal of eradicating factory farming

Individuals can hold great power, and it is crucial for citizens to recognize that this power is accompanied by personal responsibility towards our society. While it is true that not all groups or individuals have the resources or opportunities to engage in lobbying, many do. However, for a significant number of people, voting represents the pinnacle of their political involvement throughout their lives. By gaining access to information and choosing to participate, individuals can effectively shape the future of our planet and civilization.

Conclusion

The future can be bright There is no more pivotal time in history than today, with resources, technology, information, andlessons fromthepastatourdisposal. Andfor thisreason, thepower ofthe present, is greater than ever before. From a moral standpoint, the relation of power and individual moral duties should be directly proportional And in this sense, altruism, is a strategy that can assure the wellbeing and survival of all species in our planet While utilitarianism faces critics, maximizing good for the majority should not be among them. Ethicsis not idealism;itis acultivatedstrategy to shapethe future, servingas bothananchor and compass in times of moral uncertainty. Politics are often governed by emotions and discourses often rely on stirring citizens' emotions by highlighting issues that often times are ineffectively addressed or even worse, through the dissemination of falsehoods that serve hidden agendas. In this regard, I advocate for truth as the foundation upon which our political discourse should be built. The pursuit of truth and the right to be well-informed underpin the preservation of democratic values. Lack of awareness about the truth behind factory farming undermines the principles of democracy and the ability of citizens to make informed choices. The truth I speak of is the Greek concept of Aletheia, that which lifts the veil of concealment to bring truth into the light.

Resources

Ali, Sana. "The Silence of the Lamb: Animals in Biopolitics and the Discourse of Ethical Evasion." (2015). Anthis, Jacy Reese, and Eze Paez. "Moral circle expansion: A promising strategy to impact the far future." Futures 130 (2021): 102756.

Ash, K. (2005). International Animal Rights: Speciesism and Exclusionary Humn Dignity. Animal L. Benatar, S. R., Daar, A. S., & Singer, P. A. (2005). Global health challenges: the need for an expanded discourse on bioethics. PLoS Medicine, 2(7), e143

Beroiz, A. (2018). El Animal no Humano como Nuevo Sujeto de Derecho Constitucional, Santiago, Chile.

Bortolotti, L., & Harris, J. (2005). Stem Cell Research, Personhood and Sentience. Ethics, Law and Moral Philosophy of Reproductive Biomedicine , 68-75.

Cataldi, S. (2002). Animals and the Concepto of Dignity: Critical Reflections on a Circus

Caviola, Lucius, et al. "Humans first: Why people value animals less than humans." Cognition 225 (2022): 105139

Caviola, Lucius. How we value animals: the psychology of speciesism. Diss. University of Oxford, 2019.

Chomsky, Noam. "Human nature: justice versus power. Noam Chomsky debates with Michel Foucault." Retrieved on March 17 (1971): 2004.

Cochrane, A. (2012). From Human Rights to Sentient Rights. Critical Review of International, Social and Political Philosophy, 655-675.

Commitee on Animal Experiments (SCAE). (2005). The Dignity of Animals: a joint statement by the Swiss Ethics Commitee on Non Human Gene Technology (ECNH) and the Swiss Committee on Animal Experiments (SCAE), concerning a more concrete definition of the dignity of creation with regard to animals. Swiss Agency for de Enviroments, Forests and Landscape.

Corbey, R. (2013). Race and Species in the Post-World War II United Nations Discourse on Human Rights. En The Politics of Species: Reshaping our Relationships with other Animals. Raymond Corbey & Annette Lanjouw eds.

Donovan, J. (1990). Animal Rights and Feminist Theory. Chicago Journals, 350-375.

Everett, Jim AC, et al. "Speciesism, generalized prejudice, and perceptions of prejudiced others." Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 22.6 (2019): 785-803.

Feinberg, J. (1974). The Rights of Animals and Unborn Generations. Philosophy and Enviromental Crisis, 43-68.

Fineman, M. (2008). The Vulnerable Subject: Anchoring Equality in the Human Condition. Yale Journal of Law & Feminism, 1-23.

Gavrell, S. (2004). Beyond Welfare: Animal Integrity, Animal Dignity, and Genetic Engineering. Ethics & the Environment, Volume 9, 94-120.

Gruen, L. (2011). Ethics and Animals: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gruen, L. (2014). Dignity, Captivity, and an Ethics of Sight. En L. Gruen, The Ethics of Captivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horta, O. (2009). Ética Animal. El cuestionamiento del antropocentrismo: distintos enfoques normativos. Bioética y Derecho, 36-39.

Horta, O. (2017). La Sintiencia. La consideración moral de los animales: curso introductorio. Zorcal eLearning.

Jaber, D. (2000). Human Dignity and the Dignity of Creatures. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental

Ethics (13), 29-42.

Korsgaard, C. (2018). Fellow Creatures. Our obligations to the other animals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kotzmann, J., & Seery, C. (2017). Dignity in international human rights law: potential applicability in relation to international recognition of animal rights. Michigan State International Law Review Vol. 26.1, 1-42.

Greaves, Hilary, et al. "GLOBAL PRIORITIES INSTITUTE." (2017).

Horta, Oscar, and Frauke Albersmeier. "Defining speciesism." Philosophy Compass 15.11 (2020): 1-9.

Horta, Oscar. "What is speciesism?." Journal of agricultural and environmental ethics 23 (2010): 243-266.

Horta, Oscar. "Why the concept of moral status should be abandoned." Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 20 (2017): 899-910.

Kirkland, Kelly, et al. "Moral expansiveness around the world: The role of societal factors across 36 countries." Social Psychological and Personality Science 14.3 (2023): 305-318.

Kuhse, H., & Singer, P. (2009). What is bioethics? A historical introduction. A companion to bioethics, 111.

Kymlicka, W. (2017). Human Rights without Human Supremacism. Canadian Journal of Philosophy , 763792.

Low, P. (12 de octubre de 2018). Declaración sobre la Conciencia de Cambridge. Obtenido de Ética

Animal: http://www.animal-ethics.org/declaracion-consciencia-cambridge/ Mañalich, J. P. (2018). Animalidad y subjetividad. Los animales (no humanos) como sujetosde- derecho. Revista de Derecho (Valdivia), 321-337.

MacAskill, W. (2015). Doing good better: Effective altruism and a radical new way to make a difference. Guardian Faber Publishing.

MacAskill, William. Normative uncertainty. Diss. University of Oxford, 2014.

Natalia Albarez Gómez (2016) ”El concepto de Hegemonía en Gramsci: Una propuesta para el análisis y la acción política” en Revista de Estudios Sociales Contemporáneos n° 15, IMESC- IDEHESI/Conicet, Universidad Nacional De Cuyo, 2016, pp. 150-160. https://bdigital.uncu.edu.ar/objetos_digitales/9093/08albarez-esc15-2017.pdf

ONU. (1948). Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos. Obtenido de http://www.un.org/es/universaldeclaration-human-rights/

Paez, E. (2016). Ética sin distinción de especie. Derecho y Humanidades, 171-183.

Paez, E. (2018). La protección jurídica de la vida de los no humanos. Fundamentación teórica y mecanismos de tutela. En Derecho animal. Teoría y práctica. Santiago: Thomson-Reuters. Regan, T. (2003). Animal Rights, Human Wrongs. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Performance. Ethics and the Environment, 104-126.

Satz, A. (2009). Animals as Vulnerable Subjects. Animal Law, 18-20.

Schaffner, J. (2016). Animal Rights: From Why to How. Animal L., 225-227.

Singer, P. (1993). Animal liberation. Island, (54), 62-66.

Singer, P. (2004). Animal liberation. In Ethics (pp. 284-292). Routledge.

Singer, P. (2016). The most good you can do: a response to the commentaries. Journal of Global Ethics, 12(2), 161-169.

Singer, P. (2017). Ethics in the real world. In Ethics in the Real World. Princeton University Press.

Singer, P. (Ed.). (1986). Applied ethics. Oxford readings in philosophy.

Stanescu, James. "Beyond biopolitics: Animal studies, factory farms, and the advent of deading life." PhaenEx 8.2 (2013): 135-160.

Thomas, N. (2016). Animal Ethics and the Autonomous Animal Self. Toronto: The Palgrave MacMillan. Turner, B. (2006). Vulnerability and Human Rights. Pennsylvania: Penn State Press.

Waytz, Adam, et al. "Ideological differences in the expanse of the moral circle." Nature Communications 10.1 (2019): 1-12.

Zetter, Lionel. Lobbying 3e: The art of political persuasion. Harriman House Limited, 2014.

https://www.sentienceinstitute.org/

https://www.animalcharityevaluators.org/

https://www.centreforeffectivealtruism.org/

https://ourworldindata.org/ https://www.un.org/es

https://www.animal-ethics.org/ https://rethinkpriorities.org/