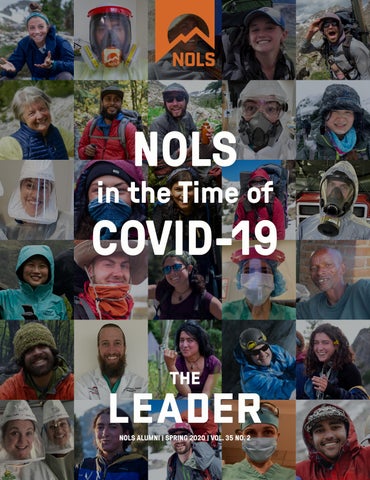

Thisissue of The Leader was just days away from being printed when COVID-19 struck. At NOLS, courses were cancelled, campuses were shuttered, and valued employees were laid off. The cost to print and distribute The Leader is high (too high in light of our precarious financial situation), but connection to our readers—you, our alumni—is deeply valued. The answer: An electronic edition. Once we settled on a digital edition, next we considered how to

include all that’s happened since coronavirus first hit while retaining the stories that had already been written. The solution: the first six pages of this e-edition cover NOLS’ challenges, solutions, and the value of a NOLS education to our alumni during the pandemic. The remaining pages are full of alumni profiles, how-to stories, and feature stories—the content you’re accustomed to reading in The Leader. Unique times call for unique responses. We hope you enjoy this one.

In this challenging time, we are tending to immediate priorities, but we’re also taking sight and focusing on what lies ahead. True to NOLS’ values, we’ve sketched out a vision to help guide our actions.

1. We will do everything in our power to keep our school healthy, vigorous, and ready to emerge from this crisis and flourish into the future.

2. We will take care of our team by retaining as many employees as we responsibly can while adjusting workflows and aiding former teammates during this challenge.

3. We will care for our communities and partners. No person or organization succeeds on their own: we will do what we can to educate and inspire our grads, advocates, sponsors, volunteers, and business partners to help them emerge from the pandemic with us.

4. We will treat this crisis as bitter medicine that forces us to reexamine our thinking, assumptions, and educational models while getting better at all aspects of what we do

Thanks to the NOLS community for sharing photos for our special section of The Leader

Dear NOLS Community,

As NOLS’ President, and in conjunction with our Board of Trustees, I’m ultimately responsible for the financial health and viability of our school and our mission. I take that commitment very seriously. As a school founded on teaching leadership, we know that exercising leadership is seldom easy—it requires a broad and fair-minded view of the facts, and a willingness to make difficult decisions.

These are difficult times for NOLS and our global communities. But, while the pandemic crisis and its related economic downturn are new to all of us, we are also all familiar with tolerance for adversity and uncertainty. We’re accustomed to weathering the storm and adapting to the unexpected. We know that united, we are powerful.

NOLS grads around the world are applying their valuable backcountry and wilderness medicine skills to this crisis—as community leaders, as volunteers, as first responders, and as frontline medical staff. We hear daily how NOLS has uniquely prepared them.

NOLS is encountering unprecedented headwinds. For the safety of our students and staff, many courses have been canceled, and travel is curtailed. With nearly 90% of our revenue generated by our educational programs, and these programs suspended for the immediate future, the challenge is obvious. Thanks to years of hard work and alumni support, we have some financial reserves and an endowment, but the pandemic’s impact is brutal.

We’ve tightened up operations, idled

hundreds of instructors, reduced our fulltime employees by nearly 60% and location staff by 85%. We are working with legislators to improve eligibility for government assistance as we do not qualify for most aid under current guidelines. Our remaining people—instructors, support staff, educators, and others remain at risk as NOLS’ ability to support the team diminishes. This threatens our community’s immediate livelihood as well as the organization’s ability and capacity to rise when the pandemic crisis ebbs.

The NOLS community is stepping up. People ask: “how can I help?” The best way you can help is to invest in the NOLS Fund today. Donations of any size help support and preserve the people and programs that are the heart of NOLS.

As a nation and as a global community we are beset by incredible challenges and almost paralyzing unknowns. But NOLS’ internal compasses still point to some grounding truths: care for yourself, safeguard the team, and be a source of solutions in our communities.

We’re so thankful that you’re part of the NOLS community. Thank you for your support of our work, and for your ongoing consideration.

With confidence in our future

Terri Watson NOLS President

NOLS is committed to providing our community with timely updates during this period of uncertainty and change. Please find the most recent course impacts at the time of completing this e-edition below, and refer to our website for up-todate information: www.nols.edu/en/ about/resources/travel-notices/

• Expedition courses, Custom Education field courses, and Alumni trips are cancelled through June 30.

• Wilderness Medicine, Risk Services, and Custom Education classroom-based courses are suspended through June 30.

• NOLS campuses in Scandinavia, Pacific Northwest, Northeast, Teton Valley, and the Yukon are closed for the summer and programs scheduled at these locations have been cancelled.

If you are a student on an impacted course, NOLS is committed to taking care of you. We are providing tuition refunds, opportunities to transfer to future courses, and available staff to support your needs. Please see our Travel updates page and FAQ for more details.

Dear NOLS,

Sitting in my ambulance, sun coming up on a deserted 5th avenue in the shadow of the Empire state building. Figured id start pecking away.

If it comes out disjointed it because of the stop/start of typing between assignments. Also i am not a wordsmith.

I am a FDNY Rescue Paramedic in NYC which is different from “line“

paramedics in that beyond paramedicine, Rescue Medics are trained as the medical component in technical rescues including High Angle Rescue, Confined Space Rescue, Trench Rescue, Water Rescue and Hazmat.

Of the 1,500 Paramedics in NYC’s five boroughs, there are 85 Rescue Medics populating 11 units throughout the city. When not on these “Special Operations Command” SOC assignments, we operate

as regular paramedics treating all manner of medic calls from ODs to heart attacks, multi traumas, and cardiac arrests -the whole shebang.

My unit is ‘07 Rescue and our CSL -cross street location- is 34th / 5th ave (The Empire State Building); we primarily serve Manhattan but often operate in the outer boroughs for Rescue Assignments. We turn out of FDNY EMS Sta 08 next

to Bellevue Hospital -Manhattan’s level 1 Trauma center. My station is proudly the first EMS station in the country, founded in 1869. “First and Still the Best” is our motto. As you can imagine, these days our focus is primarily Covid-19 related assignments but people are still getting hit by subway trains, falling off/jumping off buildings and having heart attacks, strokes etc….we show up for all of it.

We are through the apex here, and are cautiously waiting the inevitable next wave.

I think of the apex as a two-week span in April and is a focus of this discussion. The EMS call volume in NYC is arguably

the largest in the world with avg 4,500 calls per day. As a comparison, through the apex, daily call volume was over 7,400. The dramatic increase in volume paired with soon to be 1/3 of EMS getting sick and unable to work made for a sporting couple weeks.

In my 9th year at FDNY and being a paramedic in NYC over that time, i felt like I had seen just about everything. These 2 weeks eclipsed all experience. i know I’m still processing it …

Cardiac arrests increased 6 fold, it seemed like every other call was a cardiac arrest during this time; meanwhile protocols are being changed daily to try to relieve pressure on already strained hospital ERs and ICUs. Grimly, these changes revolved a lot around arrest treatments and pronouncements, and how to manage the dead.

When transporting the critically ill, no family could come along; tearful goodbyes and i love yous in many a door way… Writing this and talking with my partner as i do, we again recognize how impacted we are from all of it.

My experiences at NOLS as a student, then as a volunteer and trustee served me more than i think i can even say…

Working a tour on a NYC ambulance is like a mini expedition in a mobile tent group. We have a goal (to safely respond to emergency calls and treat the sick and injured; package and transport them to any number of hospitals.) On each call, my partner and I carry about 120 lbs of equipment over all kinds of terrain (down into subway stations, up several flights in old walk ups). Often we have to carry patients and our equipment back to our ambulance. So logistical prep is key: equipment check and inventory, food rations managed, we split tasks equitably like a good tent group does.

Good Expedition Behavior is key, we all have strengths and things that challenge us more than others. Recognizing, empathizing, and communicating with each other in real time throughout a day makes for a successful tour. Sometimes taking some more weight, sometimes asking your partner to take a bit more for you. Not just physically,

emotionally too. It’s hard to overestimate the impact of... so much death and suffering; critical clinical decisions made with increasing fatigue (physical/mental/emotional). At the risk of sounding dramatic, that is weight that must be shared too.

As Rescue Medics we also take responsibility as leaders/mentors to the EMTs (average age around 23) checking in with them physically, mentally, emotionally, showing some tricks of the trade, and importantly especially lately, modeling and supporting critical stress debriefing. Open honest assessments of self and partners is reminiscent of expedition debriefing.

Like any expedition and tent group, my partner and I are beholden to each other, each responsible for the other. Supportive, sometimes leading, sometimes following.

Equipment/safety check, On Belay, ready to climb, climbing...is a good paramedic analog.

Hot drinks are essential!!!! I can’t tell you how often my partner and my spirits have been buoyed by a nice hot cup of tea or coffee. An invaluable NOLS tradition used with equal success in the front country.

As hard as its been, im so grateful to work with the most amazing people trying to help the city i love. Its an esprit de corps that reminds me of NOLS.

When I think of the challenges the school is facing, i can’t help but think that we are equal to the task; as a group, we respond very well to adversity.

We will get to the X. Pitch tents and get some hot drinks going. Get ready for the next day, and the one after that… clear skies and easier trail right around the bend!

Best to all at NOLS. You guys Rock! Jonathan

Jonathan Kleisner is a NOLS grad, paramedic, and former member of the NOLS Board of Trustees. He wrote this from the back of an ambulance.

“I am a former full time NOLS instructor (sailing, sea kayaking and hiking), now working as a nurse on the frontlines of this pandemic. My experience at NOLS has helped me emerge as a leader at my hospital- and I am grateful for years in the backcountry developing, practicing and honing my signature leadership style. Without NOLS I would not be the leader I am today! I pray NOLS will continue to operate in the future- we need a safe place people can learn to become the leaders they are meant to be.”

— Jess Haffenreffer

A NOLS experience now is more relevant than ever. It means something to me if someone tells me they’re a NOLS grad because I know there’s a baseline of understanding on how to manage a particularly difficult situation, and that they have situational awareness, in a physical environment and in the interpersonal environment. Those are skills that are extremely useful right now.

— Jimmy Chin

“As an RN, I’ve been caring for critically ill patients who have been vented, proned, and therapeutically paralyzed. I am an ICU staff nurse in Oregon—a level 2 trauma center with approximately 160 beds.

Being the regional medical center for several critical access hospitals, the situation at our facility has been seemingly worse than our town’s situation. Some of our challenges have been the time and effort required to properly don and doff PPE while attempting to group care and treatments, limit personnel entering the room, all while preserving the PPE we have. The most challenging part of my work is the lack of PPE. A few weeks ago, it was taking over 10 days to get test results back in some cases. That’s 10 days of PPE potentially being wasted for a patient who might be negative.

I took the NOLS WUMP (Wilderness Upgrade for Medical Professionals) course in 2017 and the WFR recert in 2019. The thorough, systematic assessment technique I learned is now adapted into my standard daily practice.

— Dan Sherman

“We’ll do this just like NOLS people have always done it— one step at a time and your comrades at your back.”

— Mike Podolsky

“…as someone in the emergency department taking care of these patients and creating research studies to treat it, my NOLS experience is front and center. Leadership doesn’t happen on sunny days. The world needs us now.”

— Stuart Harris

You all take care & remember, it’ll all work out in the end—if it hasn’t worked out… it’s not the end. I’m proud to be associated in my small way with NOLS & because of my other work I have insights into how many other organizations large & small are communicating and managing these times. I have to say, NOLS is “rocking it” by comparison even though the impacts to the workforce are high across the board. You all as managers are starting from a place where the ideals of the organization are heart felt, owned personally & beloved by the staff. That’s a strong place to begin navigation. Keep it up!

—Marc Yeston

“We’re helping our community and bleeding out at the same time. Our foundation is solid with an amazing crew. We will hit the ground running when this passes. My NOLS DNA kicked in fast and hard at the right time and it’s now a switch that won’t turn off. Ever.”

— Augie Bering

“I am so happy to be a NOLSie . . . it is part of my DNA, eases my days and those around me and maintains confidence through it all.”

— Scott Briscoe

“I always stand with NOLS.”

— Herman Stude

‘Unlikely Mountaineer’ Conquers Her Fears on Everest

Fourth NOLS Grad Comes from Unique Family Pact

Wilderness Works: Expanding Access to the Outdoors

In Memory of George Newbury

Mountains of Memories: A Former Instructor Returns to the Winds

Ifindit fitting that our featured story in this issue of The Leader reflects the memories of an instructor who speaks of the influence of time outdoors and with NOLS. As I start my tenure as NOLS’ sixth president, I’m constantly remembering times past, as well as being inspired by visions of our future.

When you walk into the west wing of our Lander headquarters offices, you walk by a line of black and white photographs of previous NOLS leaders, from Paul Petzoldt to present. The first time I saw it, I said, “It’s the Long Gray Line!” This references a 1950s film about the role of a venerable institution in the life of the lead character, and how they come back to the place that played such a pivotal role in their life’s journey and personal identity.

Each day as I come to work, I’m reminded of our legacy—but I’m more focused on our future. Who will be next? What student is going to experience NOLS today for the first time, and be forever changed? And more importantly, how are the people who deserve the chance to have a NOLS experience going to learn about us?

In a world of noise and choices, so many people don’t know about the life-changing opportunities that NOLS can offer. To quote my dad, “Well, that’s a crying shame!”

So, this is my ask of you, the person holding this issue of The Leader and knowing the gifts NOLS brings to lives, both young and old. Think of someone you know, whom you likely care about, who you’d like to give an amazing gift. Then hand them this issue and tell them to check out NOLS, give us a call, and explore opportunities.

The single most common thing I hear when I meet someone who shares that they are a NOLS alum is, “it changed my life!” I smile because it is so true. Don’t let NOLS be your best-kept secret. Share the opportunity to have an adventure, to learn to save a life, and to gain big insights into working with others toward big goals.

NOLS changes lives; NOLS saves lives. I’ve personally experienced both, and bet you have, too. When we meet, let’s share our stories—and let’s share those stories with others who deserve such a gift in their lives as well.

Terri Watson NOLS President

May 2020 • Volume 35 • No. 2

Published twice a year in spring and fall.

EDITOR

Anne McGowan

DESIGNER

Kacie DeKleine

ALUMNI RELATIONS DIRECTOR

Rich Brame

NOLS PRESIDENT

Terri Watson

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Brad Christensen

EDITORIAL BOARD

Sandy Chio

Erin Doland

Brooke Ortel

Postmaster: Send address changes to NOLS

284 Lincoln St. Lander, WY 82520

The Leader is a magazine for alumni of NOLS, a nonprofit global school focusing on wilderness skills, leadership, and environmental ethics. It is mailed to approximately 74,000 NOLS alumni. NOLS graduates living in the U.S. receive a free subscription to The Leader for life.

The Leader welcomes article submissions and comments. Please address all correspondence to leader@nols.edu or call 1-307-332-8800. Alumni can direct address changes to alumni@nols. edu or 1-800-332-4280. For the most up-to-date information on NOLS, visit www.nols.edu or email info@nols.edu.

The Leader is printed with soy-based inks in Los Angeles, Cal., on paper using 10 percent post-consumer-recycled content. The Leader is available online at www.nols.edu/leader.

Cover photo: Kristen Lovelace

Editor,

I enjoyed your article on a pair of boots in the Fall issue “The Value of a Good Pair of Boots” and Bill Sweney’s experience buying and wearing them.

What a different experience I had, also in the summer of 1971! Like Mr. Sweney, I arrived at NOLS with no boots. The personal clothing and equipment list included “Climbing boots (ankle-high, Vibram lug soles): These should fit loosely with two pair heavy wool socks. Retail costs vary from $25.00 to $75.00. We will have boots to fit you which we will rent you for $10 to $15 per course, and which you may purchase

at the end of the course if you wish. If you already have a pair, you may bring them for our inspection. However, we advise definitely not to purchase this item before coming to NOLS.”

I chose the option of renting boots. There was a large quantity of used boots in the boot room, and a staffer told me to get an oversized pair that fit me with the heavy socks on. They felt awkward, because they had been worn by different feet, no doubt. But there was a solution. I was directed to fill the boots completely with water, then plunge my feet in without socks, lace the boots, and wear them while I was gathering

all my other supplies. And eventually dry them.

This technique of molding the boots to my feet actually worked well. I ended up with a very comfortable pair of boots which gave me great service during my Wind River Wilderness course. I can’t remember the brand name. Back in Lander I turned them in, ready for the next hiker to repeat the process.

Best, Henry Taves Wind River Wilderness 1971 Peterborough, NH

By Molly Herber Creative Project Manager

In unfamiliar situations, my whole body goes into stress mode. Knots form in my stomach, my heart rate picks up, and my cheeks flush bright red. On my NOLS mountaineering course when I was 17, I felt this way almost every day: when it was my turn to be the designated leader, when I tried to light the stove by myself, and when I settled into a new campsite almost every night, trying to make it home.

Frankly, I didn’t like the discomfort. I didn’t realize it was a part of my learning process until I returned home and described the experience to my family. I told them about the uncomfortable times, but also about the quiet in the morning when I woke early to cook breakfast and the exhilaration when my group topped the summit on Gannett Peak. It was then I realized discomfort was part of the experience. That by learning to be uncomfortable, I was preparing myself for the uncertainty of my everyday life.

I saw what my instructors knew all along—that tolerance for uncertainty is a skill you can learn. Here are a few tools NOLS instructors use to teach students about managing uncertainty, and they’re ones you can practice, too:

Break the challenge into manageable steps

Before teaching my first NOLS course, I was nervous about presenting classes I hadn’t taught before. Identifying that helped me make a plan to practice ahead of time. I wasn’t able to make the uncertainty go away, but I made it more manageable.

Practice self-awareness

Self-awareness helps you understand how and why you respond to stressful situations. After a significant event, take time to think about it or talk it over with a friend or the folks who were involved. Be honest about your strengths and areas for improvement so you can prepare for next time.

Practice adaptability

Think of multiple solutions to the problem in front of you, even if they seem absurd— like brainstorming all possible ways of avoiding traffic on your commute, including bicycling and hang gliding. The unexpected option may be exactly what you need.

Accept what you can’t control, change what you can

Identify factors you can and can’t control. You can’t change the fact that it’s raining, but you can decide to put on a rain jacket.

This works just as well for interpersonal conflicts, too: you can’t control someone else’s behavior, but you can control the way you respond to them.

Learn from mistakes and successes

Create a culture where it’s comfortable for you and your teammates to talk about mistakes, fix them, and learn from them. Foster a culture that values learning rather than punishes people for their mistakes.

Take care of yourself

It’s hard to respond to new challenges when your body and mind are under stress. When you notice yourself reaching your limit, do what you need to do to rest your mind and body—exercising or napping or going for a walk. Then, when the unexpected happens, you’ll be alert and energetic enough to meet the new challenge.

Molly Herber loves the smell of her backpack and does her best writing before 7 a.m. When she’s not managing creative projects or teaching expeditions for NOLS, she’s running and climbing on rocks in Wyoming.

By Brooke Ortel Writer

In1970, instructor Dave Polito concluded that NOLS courses in Wyoming had gotten too crowded. He was over it. With founder Paul Petzoldt’s blessing, Polito headed to the Pacific Northwest, intent on setting up a new campus in the North Cascades.

That first spring, NOLS Washington operated out of the affectionately nicknamed “Sloth Farm” in Redmond, Washington, later moving to “Rat Ranch” in Sedro-Woolley and finally, to its current home base in Mount Vernon. Today, NOLS Pacific Northwest is a gateway to adventures on both land and sea in Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia.

On ocean-based courses, students paddle sea kayaks along the Vancouver coast and sail keelboats across the Strait of Georgia. On land, NOLS expeditions backpack through the temperate rainforest of Olympic National Park, climb glaciated peaks in the North Cascades, or go mountaineering on the ice fields of British Columbia. In the summer and fall, semester students experience a medley of all the Pacific Northwest has to offer, bouncing from paddling in Canada to hiking in Washington—and more.

In keeping with its colorful history and varied operating areas, NOLS Pacific Northwest has continued to grow and expand its course offerings. Before coronavirus, the location planned to host its first affinity expedition for people who identify as LGBTQ+, supporting a weeklong backpacking trip in the North Cascades and a two-week sea kayaking course on the coast of British Columbia. Designed for people who share community, identity, or shared interests, affinity expeditions are an opportunity to learn outdoor skills in a supportive space.

With a wide variety of wilderness classrooms and courses, NOLS Pacific Northwest has something for everyone. And its most unusual on-campus feature? According to location director Michael Foster, the signature open-air bathhouse is “something you have to experience in person.”

QUESTION | Treatment principles for snow blindness include:

a) Decaffeinated teabags over the eyes c) Warm compress over eyes

b) Topical eye antibiotics or eye cream d) Cool compress over eyes

Answer on page 32

Four year-round; up to 20 total, including seasonal staff at the height of the summer

Land or water? Take your pick! NOLS Pacific Northwest offers backpacking, mountaineering, climbing, sea kayaking, and sailing courses.

In some parts of the Strait of Georgia, where NOLS students learn keelboat sailing, the average tide range is approximately 16 feet—a change that takes place in only six hours!

By Dan Kenah Development Officer

Rocky Mountain Transportation Manager Steve Matson looked up at the ceiling, calculating in his head how many students he has personally driven to or from the trailhead since he started driving for NOLS in 1984. “Hmm…30,000?” Though his humility may hide it, between 35 years driving NOLS buses and seven years instructing before that, Steve has served more than 10 percent of all NOLS students ever.

Steve is one of those people who, as soon as you meet him, you recognize he’s just solid. He greets everyone with warmth and a smile, steps away from whatever he’s doing, and pays genuine attention. Although, for a guy who can remember exact dates and phone numbers from 40 years ago, he still writes down some notes on his hand.

Among the 30,000 students he’s seen before and after their course, some common trends stand out. “Students are pretty pensive on the trip out of Lander,” he said. There can be anxiety or uncertainty on their faces. On the way home post-course, “Spirits are invariably higher. And all the road food disappears.”

Despite their high spirits, he still has to protect himself. “We keep the heat down in the bus on the trip back. Otherwise it’s an assault on the olfactories.” Worst smell experience? “We’d just started doing canoes and whitewater courses in the mid-80s. I picked up a spring semester that hadn’t taken off their wetsuits from the time they launched until the minute they got picked

up. When they peeled those off, it was like hauling a bus full of latrines.”

Beyond odors, Steve and his team have faced tough conditions in getting students from their course back home safely. Around Thanksgiving 12 years ago, they had to follow a snow plow past a pickup-truck rollover in Utah and dozens of other vehicles off the road, almost 100 miles to Richfield. Steve called the evacuation coordinators in Lander and told them he was stopping at a hotel for the night. “We had never put up a course in a hotel, but that was what we needed to do to keep everybody safe.”

While Steve looks forward to retiring this fall, he looks back on his NOLS career with deep gratitude. He said, “I’ve been here a long time, and it’s been a great trip, but I’ve had immense support from my wife, my family, and the people I work with. They don’t make my job doable; they make it enjoyable.”

Steve’s time working in the field has given him perspective. “Everyone does their part at the school, but I often think I’ve only been able to work in the transportation department for 35 years because of the outstanding job instructors are doing. If they weren’t, year after year, I wouldn’t have a job. I appreciate that.”

Dan Kenah is a Baffin Island 2006 grad who came to the NOLS Development office in 2016 from Jackson, Wyo. While most comfortable on skis or in front of a piano, he’s excited to climb and explore the Winds.

QUESTION | What is the most common tree in North America?

Answer on page 32

By Gabriel Leal Former Foundation Relations Officer

Len Zanni grew up in suburban New Jersey with little practical camping or outdoor experience. That changed in 1988, though, when Len took a Wind River Wilderness course in the summer between high school and college. Hooked, he took a Winter Outdoor Educator course two years later, while a student at Colorado State University.

Mountain peak, is to inspire people to get outside and appreciate the backcountry.

“NOLS teaches you how to take care of yourself in adverse or challenging conditions and how to get along with others.”

Len credits NOLS with not only kickstarting his passion for the outdoors, but also for ingraining in him the concept of expedition behavior. In the first week of his Wind River course, Len’s group had a falling out. Without quibbling, Len stuffed his pack with the largest portion of the group’s food, shouldering a heavier load. Experiences like this, he said, taught him the importance of teamwork and getting along with others.

“NOLS teaches you how to take care of yourself in adverse or challenging conditions and how to get along with others,” Len said. “Most anyone can learn how to survive outside or pick up technical skills with the right instruction, but the softer skills are some of the most difficult to learn.”

Ever since that first NOLS course, Len’s enthusiasm for the outdoors has only grown, and he’s lived an adjacent outdoor-focused life ever since. For the past 18 years, he’s worked tirelessly alongside two other co-owners to establish Big Agnes, an internationally-recognized camping gear business. You might recognize Big Agnes for its innovative sleep system or their lightweight, durable tents. The mission of the company, named after a 12,000-foot Rocky

Despite the company’s tremendous growth, Len is proud Big Agnes has stayed true to its scrappy mountain roots. It’s still based in the small mountain town of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, and staff live by the work hard, play hard mentality. Len and the Big Agnes team enjoy skiing before work in the winter and riding mountain bikes after work in the summer.

As the Continental Divide Trail is part of Big Agnes’ backyard, Len and the entire Big Agnes crew frequently use it for recreation. Several years ago, they adopted a 70-mile section of the trail, acting as stewards by engaging in activities like trail maintenance. That same year, they also completed a staff relay of the 740-mile Colorado section of the CDT.

Today, Len lives with his wife in Steamboat Springs, where they raise two active kids. He continues to embody the balance between enthusiasm and stewardship for the outdoors, serving on the board of the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative and the advisory board of the Colorado Outdoor Recreation Industries Office. He hopes to one day send his kids on NOLS courses to learn the lessons that spending time in the mountains taught him.

By Erin Rooney Doland Senior Writer

Today, the Honorable Ericka Houck

Englert presides as a District Court Judge in Colorado’s Second Judicial District. Many years ago, however, she made rulings over the malt balls and potato pearls in the Gulch at NOLS Rocky Mountain.

“My first course was Wind River Mountaineering in 1991, and afterward I took a job in the Gulch for the rest of the summer,” she said. “It’s funny because I now take a weekly yoga class in a space above a spice shop, and the yoga room smells exactly like the Gulch.”

In the years following her first expedition, she returned to Wyoming numerous times: to work in the World Headquarters and eventually to become a NOLS instructor in 1994. At one point, she worked on a small team with Rich Brame, current Alumni Relations Director, during the early stages of the Leave No Trace project. They helped develop the logo, the curriculum, and evaluated what would become the Leave No Trace principles.

“I ended up in law school for a lot of reasons, but being in the NOLS environment and thinking about public policy and why we do things in a specific way, that was certainly a part of it,” Ericka said. “That, and I was an English major, and taking up sciences was unlikely.”

Judge Englert reflected that her time in the field as an instructor also taught her a great deal about effectively communicating with others.

“The skill of being able to get along with a bunch of people you don’t know and

have a common goal that ostensibly brings you together—it is a skill that applies everywhere. And it definitely has served me well in the law and as a judge.”

NOLS also helped her learn valuable information about herself. During her course leader debrief, she was told she was often too direct and that sometimes what she said was lost in how she said it. She was surprised at the time, but looking back she is grateful for the advice she received that day.

“I still think of it,” she said. “It’s easy to be directive, and often being directive is fine. But I am more effective as a leader when I tailor my delivery to the people I’m working with.”

Ericka’s leadership and merit caught the attention of Colorado Governor Jared Polis, who installed her as District Court Judge in August 2019. She lives in Denver with her family.

This spring they plan to go camping, and then this summer they hope to head to Glacier National Park. Adventure will always find a way into her life.

“My favorite piece of NOLS gear is the fry pan,” Ericka said. “Every camping trip I go on, I use it.” Not the wind pants? “Well, I did go on a sea kayaking trip last summer with some friends and wore my 25-year-old wind pants,” she replied. “They still worked great.”

Erin

Doland fell

“I ended up in law school for a lot of reasons, but being in the NOLS environment and thinking about public policy and why we do things in a specific way, that was certainly a part of it.”

Continue the adventure and learning by adding a NOLS Alumni trip to your calendar. Join a trip and trust NOLS to run the show. Our trips are often suitable for non-grad guests too. Alumni trips cater to the interests and calendars of our grads—last year our participants ranged from ages 10-78!

We have a variety of offerings across a spectrum of physical challenge and are always adding more options. If you don’t see what you want, contact us for custom trip ideas. For more information or to sign up call 1-800-3324280 or visit www.nols.edu/alumni

NOLS Alumni Reunions in the time of COVID-19

As with communities around the world, we canceled our recent alumni reunion plans to protect our people and neighborhoods. We’re hopeful future on-site reunions and alumni gatherings will occur soon, but we don’t know when. In the meantime, to connect, network, learn, and entertain, we’re teeing up a series of interactive Zoom calls. Watch NOLS’ social networks, emails, eNewsletters and the alumni reunion webpage for more details and topics. We hope to virtually see you soon! Thanks for standing with NOLS.

Date | September 27-October 3, 2020 (7 days)

Cost | $1,995 (includes pre- and post-trip lodging in Grand Junction)

This base camping trip practices technical travel (using ropes, harnesses, anchor-building, and rock climbing gear) through southern Utah’s steep, slotted, and rugged canyon terrain. Traditional slickrock hiking—along flat canyon washes and mesa rims— is part of the trip. Bring a guest!

Moderate Difficult

Days are warm, but long days, steep terrain, loose footing, and sleeping on the ground increases this trip’s challenge.

Date | November 14-21, 2020 (8 days)

Cost | $1,995 (includes pre- and post-trip lodging in Georgetown)

Want to explore some of the Bahamas’ most inaccessible beaches? This trip’s limestone coast, channel crossings, protected bays and white sand beaches make a perfect kayaking adventure. Learn paddle strokes, navigation, rescue techniques, and more. Grab a chance for beach walking, snorkeling, and enjoying the Bahamas! This trip is for all levels of paddlers.

Moderate Difficult

Camping on beaches is scenic, but paddling means plenty of sun and possible wind.

By Brooke Ortel Writer

I’m not sure what I want to do next. For high school and college students, a popular answer has become “take a gap year.”

In other words, it appears that the rest of the world is finally catching on to what NOLS discovered a long time ago: there’s a lot of value in learning by doing. Today, many students choose to spend all or part of their gap year with NOLS, seeking leadership experience, technical outdoor skills, and cultural immersion.

But there’s an ever-widening array of gap year options available—as well as some common misconceptions about taking a gap year with NOLS. Before you start making plans, let’s bust some myths about gap year expeditions.

1. I don’t have time. Nonsense! Of course you do. A NOLS expedition of any length, from a two-week course to a semester or whole year, is a great addition to a year outside the traditional classroom. Many students optimize their gap year by pairing a NOLS course with independent travel, internships, and more.

A month-long Alaska Backpacking

expedition might be just what you need after a hectic last semester of high school—and before diving into an office-based internship in the fall. As you hike across sweeping tundra and rugged mountains, you’ll learn leadership and communication skills that’ll set you apart as an intern and beyond.

2. I’ll fall behind on college credits. Don’t worry—in addition to diving into NOLS’ time-tested leadership curriculum, students can earn 6–27 credits for expedition courses. More than 400 colleges and universities nationwide accept University of Utah credit earned on a NOLS course, and many more grant their own credit. Plus, some expeditions also offer industry-respected certificates and certifications, including Wilderness First Aid, Wilderness First Responder, and Level 1 Avalanche Training.

3. It’s out of my reach financially. That’s what scholarships are for! Each year, NOLS awards almost $2 million in needbased financial aid. You can even apply for a scholarship prior to applying for a course

to help inform your decision. And if you have a 529 College Savings Plan, you can also put funds from that account toward your tuition.

4. Out in the wilderness, I won’t have the opportunity for cultural engagement. Turns out, you can do both—explore beautiful remote environments and gain global perspective while interacting with new communities. Cultural learning takes different forms on different courses, but you’ll find yourself engaging in both structured activities and impromptu interactions.

On a Fall Semester in India, for example, you’ll participate in a homestay with a local family and also find opportunities to practice speaking Hindi while backpacking through high mountain villages.

Take a gap year. Find out what you want to do next.

Brooke Ortel is a runner and writer who enjoys finding adventure in the everyday. True to her island roots, she loves sunshine and that salty ocean smell.

By John Gookin NOLS Instructor

Our NOLS alumni trip began like most NOLS expeditions do, with an orientation. In Lander, Wyoming’s Noble Hotel, two families and three instructors, including me, met each other, and ran through logistics, questions, and personal trip goals for our Backpacking and Fly Fishing with Llamas Alumni trip. While the meeting felt a little stiff and sterile, it was clearly the early stage of typical group development. The group, however, was not “typical.”

Family teams are common on alumni trips; this group, though, was comprised of just two families, unknown to each other. One was a three-generation Jewish family, led by a recent teenage NOLS grad. The other was a Muslim Indian-American family comprised of father, mother, and two sons. The team age spread was 9 to 71 years. Despite the surface appearance of differences across age and culture, both families clearly wanted to enjoy their time together in the wilderness, and to learn to camp well and travel on their own in similar settings.

The next day, we issued gear, taught basic lessons about packing, and headed

into the Wind River Range. Even with llamas carrying half our gear, backpacks were burdensome; the team had to get used to carrying heavy loads at 10,000 feet. Already challenged by the hike, a mountain storm blew in—thunder, lightning, and rain rapidly turned to marble-sized hail. With a break in the weather, our team confronted a tricky river crossing, complete with rushing current, slippery boulders, and sketchy wet logs. The families immediately stepped up to spot one another and coax anxious llamas across the channel. Leaving the trail for a “shortcut” to our campsite, our path was a maze of boulders and thick trees. We all worked together to find the relief of camp. It had been a challenging first day, but also a defining time as the team dealt with genuine obstacles that required cooperation and overcoming adversity.

We cooked dinner together that night, as we did every night of the trip, and shared some unmatched conversations.

Food—its identification, creation, presentation, and consumption—is a key element on many NOLS adventures. This

trip brought two family cultures into the mix as we learned why a Muslim family might eat kosher meat. The families explained that kosher and halal are very similar, both based on being respectful of the animal and being sanitary. This piqued the whole group’s broader curiosity about the Muslim faith. Honest, kind questions and answers about family prayers, hijab considerations, sunrise observation, and other aspects of Islam popcorned around the group.

Perspectives on spirituality sometimes took a backseat, though, to the hilarious and curious interactions between our most senior (age 71) and Jewish and our most junior (age 9) and Muslim teammates. Different generations, different families, and different perspectives didn’t get in the way of mutual enjoyment, laughter, riddles, fly-fishing, day-hikes, learning, and exploration. Less than 48 hours after our stiff Lander orientation meeting, we were in the wilderness, in high spirits, and glad to be with each other.

By the end of the week-long trip, we’d all learned and shared so much. The team’s backcountry skills had grown and our appreciation for spiritual perspectives had broadened. Strangers came together to spend time as family units and came away with surprising and powerful learnings and insights.

Our llama adventure affirms that wilderness can connect us—in the outdoors, in our communities, and in our families.

By Molly Herber Creative Project Manager

Cell phones are becoming better adventure tools every day with apps for navigation, trip guides, even stargazing. So why is a cell phone nowhere to be found on a NOLS equipment list? Some might say it just isn’t worth it—most of our course areas are beyond the reach of reliable service. While that’s true, the more important answer is that students on NOLS courses keep finding value in unplugging. What they learn about themselves and others is impossible to get when a phone is in their pocket. We aren’t saying never to bring your phone camping (they are amazing tools), but if you consider the reasons we leave phones behind, maybe you’ll make your next adventure a tech-free one.

Boredom is good for you. One of the main reasons people use their phones is distraction. We open social media apps just to see what’s going on, watch videos, or read. When phones aren’t present, our attention is more available. Although you need to pay attention to your surroundings in the outdoors, you’re also spending hours each day hiking or paddling or waiting for water to boil—times of repetitive motions when your mind has freedom to wander: to plan for the future, let ideas take root, and gain perspective on your life.

Limiting resources leads to better problem solving. We rely on our phones for quick answers. You can look up the height of Mount Kilimanjaro, the year proper hiking boots were invented, and the real length of an inchworm in an instant. But some of the most fun conversations—and most heated debates—happen on NOLS courses around just these kinds of questions; things you could know in a moment at home, but are impossible to verify—and perfect to debate—when you’re in a mountain valley in Patagonia.

Additionally, not having easy answers available builds the mental muscles of creativity and resilience. Research conducted on NOLS expeditions showed participants learned ill-structured problem solving (solving problems with unclear goals and incomplete information) better than their peers who had only learned in a classroom setting.

You connect better with the people around you. Many of us now rely on our phones for communication and maintaining a sense of community. Because you’re outside of your normal support network on a NOLS course, your expedition mates become the people you turn to for advice, jokes, and encouragement when the trip gets difficult. Relationships form quickly. And more research is showing

that conversations with no smartphones present are rated as significantly higher quality than those with smartphones around, regardless of people’s age, ethnicity, gender, or mood. When you’re in the outdoors, the people you’re with are the people you’re with. You’re committed to this group and your shared goal of moving through a wild place together.

So, next time you’re packing your bag for an adventure, think twice about bringing your phone.

Molly Herber loves the smell of her backpack and does her best writing before 7 a.m. When she’s not managing creative projects or teaching expeditions for NOLS, she’s running and climbing on rocks in Wyoming.

By Aimee Newsom Alumni Relations Coordinator

Courtney Reardon is—by her own estimation—an unlikely mountaineer, but that hasn’t stopped her from climbing some of the world’s highest and most challenging peaks. Courtney, who has worked in finance for the past 13 years and calls New York City home, grew to love the outdoors later in life. She admits she was “shy and timid” as a child. “Even now, I have a vivid imagination,” she said, “and a lot of that imagination goes toward fear.” Over the years, this seemingly intrepid NOLS graduate has discovered that conquering the fear of failure and discomfort has afforded some of her greatest opportunities for personal growth.

A graduate of Columbia University, Courtney was working on Wall Street when the crisis of 2008 put her career in jeopardy. In preparation for a possible layoff, she brainstormed alternative plans. Glancing around her home, she realized all her favorite books, movies, and documentaries were about climbing and mountaineering. She’d never attempted either activity but felt drawn to pursue the interest.

Courtney avoided the impending layoff and seized

“Over the years, this seemingly intrepid NOLS graduate has discovered that conquering the fear of failure and discomfort has afforded some of her greatest opportunities for personal growth.”

an opportunity to register for her first NOLS course in 2009: a two-week Idaho winter camping and backcountry skiing trip for adults. Despite stormy weather, three feet of snow, and negative temperatures, this first foray turned out to be “fuel and food for the soul.” Every personal trip Courtney took over the following six years was spent in a tent. She expanded her outdoor skills and gained toughness as she traveled. But, even after honing her mountaineering techniques on harsh summits like Denali in Alaska and Vinson Massif in Antarctica, Courtney still considered herself a “desk jockey on vacation.”

With encouragement from her husband and knowledgeable alpine guides who recognized her ability, Courtney trained for a two-month-long summit expedition on Mount Everest in 2018. After three intense months spent strengthening body and mind, she traveled across the world to join a small team of all-male German and Austrian climbers. Almost immediately, she questioned her chance of success. An hour into a training hike on day four, with lungs burning and doubt swelling, she was forced to turn back to base camp and recover. Humiliated, she watched her more experienced teammates continue without her. “I felt embarrassed that I’d even showed up thinking I could climb Everest,” she admits.

A disheartened phone call home resulted in a much-needed pep-talk from her husband. He reminded Courtney of how much she loved to be

outside challenging herself and that she would only get stronger as the climbing got tougher. Despite the first physical setback—to be expected at such high altitudes—he knew she was ready to accomplish her goal.

He was right. Several weeks later, after pushing through pain and anxiety, Courtney became the 68th American woman to reach the earth’s highpoint.

Courtney continues to be inspired by others who set goals requiring sacrifices of time, resources, and even physical or mental comfort. Her climbing résumé is impressive, but her humility is apparent when she admits that her journey has not been easy. “I want people to know that my inner self is still a timid 13-year-old girl,” she insisted. The difference now, it seems, is her grit and will to overcome. Even in the face of ever-present fears, “I go out and do the things that scare me.”

By Anne McGowan Development Communications Coordinator

Jordan stepped off the bus at NOLS’ Rocky Mountain campus as soon as it pulled into the parking lot. Tanned and strong after her Wind River Wilderness course, she and her coursemates unloaded the gear they’d carried for the last month while her parents, Tim and Lucy Jordan, stood undetected under the eaves of the building. When Mollie spotted her mom and dad, she threw herself at them, hugging them with such force it appeared they all might topple over.

Completing a 30-day NOLS course in the Winds and catching a ride home with her parents was a new experience for Mollie, but it wasn’t for Tim and Lucy. Mollie was their third and youngest daughter to become a NOLS grad, thanks to a unique pact made with the girls’ aunt and uncle.

In 2006, Mollie’s cousin, Cristen Mangrum, enrolled on a Wind River Wilderness course. Cristen was 16 when her father Bill suggested a NOLS course after a year her mother Valerie called “not an easy one.” Cristen agreed, so Bill drove her cross country to Lander, Wyoming for the beginning of her course. He and Valerie were also there to greet her at the

“The young women now share stories and memories, encourage and challenge one another, and all have a deep respect for the environment, especially the Wind River Wilderness and Rocky Mountains.”

end of it. “On the drive home, Cristen read portions of her journal revealing just how much she’d gotten to know herself, and who she was in relation to others,” Valerie said. “She came back changed.”

Treasuring those changes in Cristen, Bill and Valerie lit upon an idea: they would offer a NOLS course to each of their young nieces, Tim and Lucy’s children.

There were, though, some unique stipulations to the Mangrum’s ‘deal’ with the Jordans: All the sisters—not just some—had to agree to take a course. They had to be 16 at the time of their expedition and enroll, like Cristen did, on a Wind River Wilderness course. The Mangrums would transport them to Lander before the course, while their parents would be responsible for the trip home.

The end of Mollie’s course gave the families a chance to reflect on the experience. “Each trip has been unique, but for each girl, it was the trip they needed,” Valerie said. Cristen Mangrum found community on her course. Abigail Jordan said she found her voice, while her sister Amanda learned a leader isn’t always at the front of the pack. For Mollie, “The best lesson I came away with was to be confident in myself. It sounds cheesy, but it’s true. I had to learn to trust myself physically and mentally and to stick to my decisions without doubting myself.”

Their courses also brought the sisters and cousin closer. “It’s something only we understand,” Mollie said. “Even my aunt and uncle, who sent us on our trips, don’t understand what really happens on a NOLS course because they’ve never experienced one.” The young women now share stories and memories, encourage and challenge one another, and all have a deep respect for the environment, especially the Wind River Wilderness and Rocky Mountains.

“My NOLS course was the craziest and hardest—but most rewarding—thing I’ve ever done,” said Mollie, grateful for her aunt and uncle’s gift. “It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience and it truly changed my perspective on myself and life.”

her love of words and books to a career in writing.

By Brooke Ortel Writer

ForBrandon Quintero, the most challenging day of his NOLS course was also his favorite.

On his first day as designated leader, Brandon led his coursemates across a high mountain pass in Wyoming’s Wind River Range. “There was no trail—just all mountain and huge snowy peaks. You couldn’t even call it hiking,” he remembered. “But it was magical.”

Brandon came to NOLS through Wilderness Works, an Atlanta-based nonprofit that works with underserved students ages 6–18 through a progression of weekend outings, summer camps, and outdoor trips. The organization’s mission is to “provide homeless, at-risk, and very vulnerable children with year-round enrichment, experiential education, and character development.”

Founder Bill Mickler first worked with underserved youth during his college years and knew he’d found his passion. In 1997, he left the corporate world and created Wilderness Works. He hasn’t looked back. “My fear is that extraordinary young people will miss out due to disadvantage,” Bill explained. “These young people come from really

“My fear is that extraordinary young people will miss out due to disadvantage. These young people come from really daunting circumstances and they inspire me.”

daunting circumstances and they inspire me.”

Starting with weekend visits to local parks and museums during the school year, Wilderness Works also makes it possible for underserved and homeless children to attend weeklong summer camps.

Many younger students dream of one day attending the program’s capstone, Field Camp—an opportunity to go on multi-day trips to Mount Rainier, the Tetons, Yellowstone, and more. “For kids who don’t even get out of their zip code, it’s a transformative experience,” Bill said.

In 2019, NOLS partnered with Wilderness Works for the first time, enabling four students to attend a 30-day Wind River Wilderness course through its Gateway Scholars program. This initiative provides full-tuition scholarships for underserved youth.

Thanks to previous Field Camp trips, the Wilderness Works students were well-prepared for the backpacking expedition. But, Bill pointed out, “One of the things we all have to learn is how to be more tolerant, sensitive, helpful, and selfless. I noticed growth in all four guys in that area.”

Wilderness Works student Victor High added that the wilderness medicine training he received “helped me the most since I do go camping, and if this was to happen while I am on a trip, I wouldn’t freak out. Instead, I would keep calm for myself and the person injured.”

Based on conversations with students and instructors, Bill concluded that everyone learned something. “It’s not just about disadvantaged kids discovering outdoor living,” he said. “It’s also about the advantaged kids interacting with other types of people. I could tell it really added a dimension to the experience.”

More than a decade after his first Wilderness Works outing, Brandon Quintero has come full circle. Now a staff member, he’s looking forward to leading a trip for students ages 13–15 this summer. He’s determined to make sure the kids have a good time: “They’re pretty green and I don’t want their first experience to be their worst experience!”

Brandon found his place in the outdoors. Now he’s excited to give others the opportunity.

By Anne McGowan Development Communications Coordinator

Thereare folks we meet just once and know they possess something special. It’s visible in their broad smile, the sparkle in their eyes, and their love for adventure. George Newbury was one of those people.

The longtime NOLS Pacific Northwest director, one-time Kenya director, early instructor, and a NOLS Instructor Association (NIA) founder—among many titles—passed away on March 16, 2020.

George came to NOLS in 1970, just five years after its founding. Fresh from the U.S. Coast Guard, George veered from a winter of skiing in Jackson, Wyoming to Lander to visit his cousins, Martha Hellyer and Diane Shoutis. While he planned a short catch-up, he was offered work at NOLS by Martha’s husband, Rob Hellyer. George hired on, repairing old Army surplus vehicles that NOLS founder Paul Petzoldt purchased, and soon took his first course—with Rob and Martha as his instructors. That same year, George met his partner in life and adventure, Mary Jo Hudson.

“Of course, we met at NOLS,” Mary Jo said. A student at the University of Montana, she had heard about NOLS from friends in Jackson.

“I went back to Missoula, quit school, and headed to

“He taught me how to be an instructor and a leader, taught me how to be a branch director, a supervisor, a parent, and taught me what was most important in a friendship. He will be missed.”

Lander,” Mary Jo remembered. A talented seamstress, she sewed sleeping bags, earning money to pay for a course at NOLS East in Connecticut. Returning to Lander after the course, Mary Jo was picked up at the Riverton Airport by the man Paul sent to retrieve her—George.

“That was the start of our life together,” Mary Jo said. The pair took their NOLS Instructor Course together in 1972, but not before driving cross-country in an unheated Volkswagen, and living on a sailboat off the Grenadines.

Married in 1976, their passion for NOLS and for adventure was just beginning. George took on the directorship of NOLS Kenya that year, running the location with Mary Jo. When they left in 1979, the Newburys caught a plane to Rome, bought bicycles, and pedaled to London. Next move: back to Lander, where they had their sons, Eric and Craig. George worked in Admissions while Mary Jo found a place in the Finance department.

In 1983 George was named director of the NOLS Pacific Northwest location, and the family moved to Sedro Woolley, Washington. During his tenure, which lasted until 2007, George opened NOLS locations in Canada, India, and Australia. He negotiated the purchase of property in Conway, Washington where NOLS Pacific Northwest now sits, and then helped design the facility.

“Designing that property was a great project for George,” said Mary Jo. “He was proud of it. He built a beautiful facility and created a fun

work environment. He was excited for young in-town staff because they wanted to live the NOLS life, maybe become an instructor someday, excited to learn about climbing and sailing.”

Most important to George, though, was his family. He relived his youth with his boys, teaching them to ski, sail, ride bikes and motorcycles, and to travel. Others benefitted from lessons George taught too.

“He taught me the NOLS curriculum,” said John Gans, former president. “He taught me how to be an instructor and a leader, taught me how to be a branch director, a supervisor, a parent, and taught me what was most important in a friendship. He will be missed.”

Mary Jo, Craig, and Eric Newbury are asking that gifts in George’s memory be made to the NOLS Fund in recognition of his impact on the school and its students.

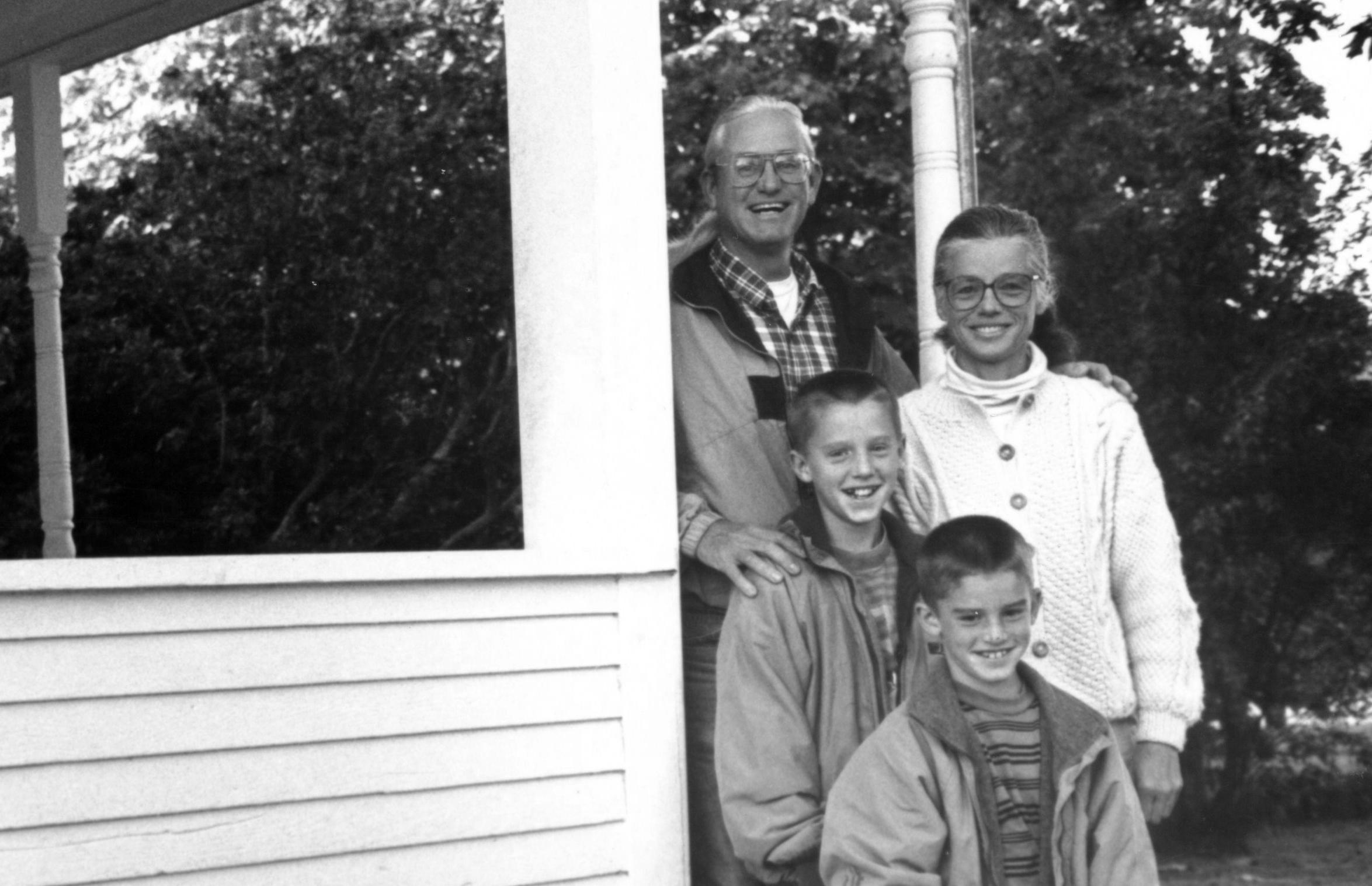

By Pete Yeomans NOLS Grad

Fromthe top of Wind River Peak, I can see all the way to the Tetons. Between our vantage point and the Grand Teton lie numerous peaks and valleys holding memories precious to me. Next to me on this perfect summit day are my wife and my three children, ages 15, 11, and 9, along with another family that has become our closest travel companions. This is our fourth Wind River Range family backpacking trip in the last seven years. My youngest was only 3 years old when we first walked up the North Fork of the Popo Agie River to the Cirque of the Towers. My oldest is now 15, the same age as I was when I took my student course in these same Wyoming mountains. That course planted seeds in me so deep and strong that I continue to feel its influence at the age of 50.

I turned 16 on that Wind River Wilderness course in 1984. Despite being the youngest person on the course, I was given the opportunity to be the small group expedition leader. Before I’d even met my instructors, Reese Jameson, Lisa Johnson, and Paul Twardock, I had entertained a fantasy about working for NOLS someday. But climbing steep snow to a rock gully to a snow couloir to reach the summit

“That course established a relationship to these mountains that has been a wellspring of beauty, inspiration, and learning to last a lifetime. For that, I am indebted to NOLS for the richness of my life.”

of Mount Victor with Lisa made working for NOLS a certain ambition. At the top, you could have told me my next climb was going to be Mount Everest. Back in town, I called my parents collect from a pay phone in the Noble Hotel lobby and burst into tears when I heard my father’s voice. I was so full of the richness of the experience that I could not find the words to explain. Later that day, I gathered old maps at the Rocky Mountain branch. Back in my room, I painstakingly and perfectly traced our fourweek route with a pen across the maps.

From the top of Wind River Peak, I can’t pick out Mount Victor or quite recall my student route of 35 years ago, but I can see countless places where I had travelled as a course instructor. My Instructor course launched me into work that gave me some of the most precious experiences of my life—full of opportunities to lead and to learn. On this summit day, my family sits patiently as I try to guide their eyes to each peak and tell them the corresponding story. I have perhaps the same feeling I’d had in that phone booth in 1984—the sense of being so moved that I cannot quite find the words to do justice to the memories. My family indulges me nonetheless. I’d first climbed Wind River Peak on my student course and then while instructing a Wind River Wilderness course in 1993. To the south over toward Poison Lake, I can see snow slopes where I taught snow travel and self-arrest with Sam Talucci and Mark Harvey that year. That was

the course on which I got my first contract to proctor a fall semester. A proctor is an instructor who follows students on every section of a semester, while other instructors join and leave the course as needed. We all laughed when the news came in with the food ration and a resupply of half a bar of hand soap—the half that said “Proctor” and not the half that would have said “Gamble.”

To the north, I can see the unmistakable snowy summit of Gannett Peak. I remember the hiking section of a 1993 Fall Semester in the Rockies when Christine Lichtenfels, Chris Sanok, and I took the course up the Gooseneck to the summit after bivying the night before on the top of Dinwoody Pass. Nearby was Mount Helen. From the southern end of Titcomb Basin, we launched the students on their small group expeditions. As soon as they were out of sight, we sprinted up the basin back to Mount Helen, climbed the Tower One Gully, and then made it all the way to our designated campsite. Three years later, I took my brother to the summit of Gannett. Overwhelmed by the experience, he cried at the top up of the Gooseneck. On the descent, I worked not to panic as I struggled with a loose

crampon on the steep snow above the gaping bergschrund.

Sitting with my family and looking north, I can also see Fremont Peak. I know I took students up there once but can’t recall when. Clearer in my memory is taking my brother to the top in 1994. The view over the eastern side dropped him to his knees to catch his breath and steady himself. Somewhere in the shadowed ridgeline, near Fremont, but on the near side of Indian Basin, sits Mount Harrower. Two years ago, friends and I ignored the cloudy weather, and picked the wrong day to climb the north ridge. Eight pitches up, we got stuck in a heavy hail storm with lightning and electrical currents that stabbed at my neck when I leaned away from the rock. I decided the long rappel in the storm was going to be more dangerous than pushing on. All credit to our good friend who led the damp pitches when the storm finally passed. We made it safely back down, but I wondered how I had gotten us into that terrible situation. Maybe my NOLS smarts had worn out with time.

About halfway between those northern peaks and our position on Wind River, I can also pick out the summits of Desolation Canyon. I tell my family about two different bivys with students on the summit of Midsummer Night’s Dome, a geology class below the sweeping face of Raid Peak, and a snow climbing class on the eastern slopes of Mount Geike. On the west shoulder of Mount Bonneville lays a high pass I’d crossed through once as a student in 1984 and then again as a course leader in the 1990s. Some memories are less dramatic and yet remain mysteriously vivid despite how random they seem. I can remember stopping at the top of that pass, looking westward at the gorgeous soft twilight that marked a day that had gone on longer than planned, and telling myself, “I have to remember this moment, I have to take a picture with my mind.” I still have that “photo.”

Other memories were out of view but very much on my mind. I started my Instructor course at the edge of the

highway, right where U.S. Route 287 leaves the Wind River Reservation. On the short drive from Lander, I had convinced myself I’d forgotten my hiking boots and would be failed immediately. I was certain! Imagine my relief when I found them at the top of my pack as we unloaded the bus. My instructor Tom Bol somehow managed to identify 50 bird species between the bus and our first campsite a few miles away. He later helped me prep my birding class and flapped through my “classroom” wearing a snorkel and flippers as I talked about the unique behavior of the American Dipper.

In some ways it feels like my life is flashing before my very eyes— not my whole life, of course—but certainly some of the most impactful memoires that were steeped in learning, adventure, and a growing sense of competence. But also experiences that gave me a stiff dose of humility, that tempered the undeniable itch for adventure, like the misadventure on Harrower with my friend. To the west, I like to think I can see the Wyoming Range where I worked a winter course with Patti Saurman and Chris Walburgh. On that course, Chris enticed me with the possibility of climbing big mountains with him in the future. Just four months later, as I arrived for my first summer working Alaska mountaineering courses, they both died in an accident on the slopes of Mount Hunter.

Even the sheer joy and eagerness of my first day as a NOLS instructor was met with caution and contemplation. I arrived at NOLS Rocky Mountain for my very first briefing of my very first course. The program supervisors looked stunned and then were reduced to tears and anguish when they shared the news that Ritt Kellogg and Instructor Tom Walters had died on Mount Foraker, and that Instructor Colby Coombs had barely survived. Though I’ve escaped the severest of consequences of mountain adventures, my mountain memories are home not only to the sweetest moments, but also to the realities of the risks taken.

Outside of Wyoming, I also worked at the NOLS Alaska, Teton Valley, and Southwest locations. I can’t see those places from the top of Wind River Peak. I can’t see Philadelphia, where I have lived for the past 22 years. I am so fortunate for how those experiences have shaped my life, from a student at 15, to an instructor at 24, to a father and husband at 50. I am blessed with a wife and good friends who have wanted to return to these mountains with me. I am proud and grateful that my children travel through these peaks and valleys in comfort and relative safety.

It is time to head down. We need to make sure everyone descends the snowfield safely. Over 35 years of as much time as I could arrange, after a broken ankle, two meniscectomies, and a groin surgery, I can hardly believe that these old knees and back still let me roam and share my favorite place on earth with the people I love. It all started with that Wind River Wilderness course in 1984 when I was just a 15-year-old boy. That course established a relationship to these mountains that has been a wellspring of beauty, inspiration, and learning to last a lifetime. For that, I am indebted to NOLS for the richness of my life.

By Amy Feng NOLS Grad

To live deliberately I left the pace of life For the wonderful world of mountains With which time and peace are rife

I met thirteen other students And three instructors too And together we set out Into the striking view

For thirty days we slept in tents In the land of the midnight sun Struggling to fall asleep After the day was done

We hiked up in the alpine And canoed in rivers too Tearing through whitewater Through the woods we flew

We cooked on top of stoves And even open fires A fry-bake and a pot Is all that it requires

From muffin mix and muesli To potato flakes and flour We always had a meal to eat Within the starting hour

We got to swim in glacial lakes And also summit peaks And see all kinds of wildlife In just a couple weeks

We counted contour lines And learned how to bake bread And sometimes did our eight-minute abs Before we went to bed

And sometimes we’d catch fish And build a great big fire And grill the fish and play guitar And never seem to tire

And during evening meetings We played games like Yee-haw Or read excerpts of poetry From many we could draw

It wasn’t always easy In fact it rarely was And when it would get really hard I would think of my because

From burning chocolate cake And almost everything else too And forcing on wet neoprene And finding three more to poo

To treating countless blisters And portaging our canoes And sleeping on the hardest rocks And dealing with the blues

And, of course, there was that ten-hour day Bushwhacking through the thick We didn’t even get to camp We weren’t always quick

But the fight was worth the victory Every single day For the beauty was surreal Forever we hoped to stay

I could never stare for long enough Could never make it real

My mind could just not understand How the mountains made it feel

The peaks were so dramatic I could almost hear them speak

Reaching out with open arms Allowing me to seek

The answers to my questions Were few and far between But questions to my answers I seemed to often glean

For I had come to them

To live and learn and love

But little did I know

The answers were not above

For I had brought them with me In my heavy heart And in my mind and soul They had always been a part

And so I reached down deep inside And searched for what I knew

The more I searched and found

The more I learned and grew

And then I could find peace With who I was before And also love who I am now

And be excited for what’s in store

Because becoming is the greatest joy That one can yearn to live

And becoming is the greatest gift

That one can yearn to give

Because I want to be wholehearted And also fall in love

With as many things as possible In this world I am one of

And I was ready then To change considerably And despite the pace of life

To live deliberately

Amy Feng is a 2019 Yukon grad from Coquitlam, British Columbia, studying at UNC-Chapel Hill. She loves spending time with her wonderful friends and family, reading books, and writing lists.

By Chandler Shepherd NOLS Grad

After taking my NOLS Wilderness

EMT course in the summer of 2017, I applied my training as a backcountry Preventative Search and Rescue Ranger at the Grand Canyon.

One day on the trails, I ran into a young, healthy-looking hiker who was struggling. Since my job was to help injured, sick, or tired hikers, I asked, “Hey man, are you okay?” He shook his head.

Based on his symptoms, he was more than unmotivated or tired. I set my pack down and started my patient assessment.

My new friend was a mid-30s male with severe cramps, headache, and nausea, and was unable to keep food down. It seemed like a pretty bad case of dehydration—at least until I got to the history part of my patient assessment. In six hours, he drank almost two gallons of water, he said. Because of his nausea, he hadn’t eaten much. I remembered learning these symptoms and relevant patient history in my NOLS WEMT course and I became very suspicious that the hiker had hyponatremia.

While hyponatremia is often overlooked in medical courses, thankfully my NOLS course had an in-depth lecture about hyponatremia versus dehydration. Water alone isn’t bad, but often people exerting themselves in a new, hot environment drink water excessively out of fear of dehydration.

Common symptoms make exerciseinduced hyponatremia, like my patient’s, challenging to diagnose. Headache, nausea, vomiting, irritability, and cramps look like symptoms of mild dehydration. The key to diagnosing hyponatremia is to get a comprehensive patient history. Asking questions like, “how much water have you had today,”

and “how much have you eaten/what have you eaten” is crucial.

The physiology behind hyponatremia is that the extreme intake of water leads to a salt imbalance, which puts the patient at risk of brain swelling. An extremely hyponatremic patient can die faster than an extremely dehydrated one. Luckily, I found my patient in the condition’s early stages. We limited his water intake, fed him salty snacks, and evacuated him via helicopter to the rim, where he obtained definitive care. Paramedics and doctors can give hypertonic saline to rebalance a patient’s salt levels, which my patient required.

As with most hyponatremic patients, the treatment for my hiker was relatively easy. For treatment, always avoid or severely limit the patient’s water intake first. Allow the patient time to rest until their symptoms subside. Salty snacks can also be helpful, but if the patient has moderate to severe hyponatremia, they may need IV hypertonic saline.

When you go out on your next trip, remember what I told my patient: prevention is key. Our bodies do an amazing job of telling us what we need if we listen; if you’re not thirsty, don’t drink.

Next time you’re on a trail and see someone struggling, get a good patient history, share your salty snacks, and don’t forget about hyponatremia.

By James Wynn NOLS Wilderness Medicine Staffing Coordinator

We’veall been there. “It’s springtime and I’m getting after it” you say to yourself as you dust off your hiking boots, throw on your old pack, and head off into the wilderness.

And then it hits, two miles in: you realize your back is killing you, you’ve developed a troubling limp, and your knees feel like someone pulled the ol’ switcheroo and replaced your cartilage with bits of gravel and broken glass.

So, you turn around and go home, a bit dejected, in a bit of pain, and now saying to yourself, “What happened to me?”

Well, whether by a year or a decade, you got older. If you are trying to get back into shape for the spring, it’s important to take it one step at a time, both figuratively and literally.

“The biggest thing people need to keep in mind when trying to get back into shape is to not confuse your current self with your former self,” said Charlie Manganiello, strength coach at Elemental Fitness in Lander, Wyoming, and NOLS Wilderness

Medicine and Spring Semester in Patagonia 2007 alum.

One of the biggest mistakes Manganiello sees is that people who used to be in tip-top shape assume they still are, no matter how much time has passed since that last 20-mile hike in full ruck.

“It’s about clear expectations of your current level of fitness, and the level you would like to reach,” said Manganiello. “We need to create a training environment that sets people up for success rather than failure.”

Just like you wouldn’t try to bake a cake without first making sure the oven is on, you shouldn’t try to head into the mountains without making sure your legs can handle the strain.

“The biggest thing is just to start moving,” said Manganiello. “People really underestimate how important just being able to go for a walk is.”

Whatever your goals are, if it seems like it’s been a long winter on the couch, the best thing you can do is to commit yourself to a stroll.

“Go for a 60-minute walk, three days a week for three weeks, and see how you feel,” said Manganiello. If at the end of those three weeks you feel great, start adding stuff to your regimen. Throw a pack on your back. Add some hills. But whatever you do, don’t get ahead of yourself. Just because you can climb 5.10s does not mean you can climb El Capitan.

“It sounds so basic, but what we really need to keep in mind when getting into peak performance is that when we are starting out, we are really just building the ability to begin training again,” said Manganiello.

So, to put it into context: if you are trying to get into shape, the goal shouldn’t be a 500 mile through hike, but rather to get yourself to a point where you can begin to train for the through hike. After all, how do you eat an elephant? Why, one bite at a time, of course.

“I like to encourage people to get into the mindset of why they are training,” said Manganiello.