Introduction and background

Transceve is a social purpose organisation utilising AI technologies to extract social impact insights from conversational data, predominantly to support the third sector (charities, social enterprises, and other social purpose organisations) to measure and act on its social impact more easily.

As an organisation, we recognise the significant potential of AI technologies for third sector organisations and beyond. We are also acutely aware of the significant issues surrounding biases in Large Language Models (LLMs) and are taking an active role to mitigate such biases, to further the work of Transceve in an ethical, socially responsible way, and to provide much needed contributions to both the literature and practical work in this area.

This paper identifies a clear gap in the literature, and proposes a novel, more easily accessible solution to fill this gap. We believe this has significant potential for the ethical, equal, diverse, and inclusive application of AI technology.

The researchers

An initial team of researchers contributed to the authorship of this paper:

Paromita Saha Killelea PhD is a consultant and interdisciplinary researcher with over 15 years of experience across academia, journalism (BBC, ITN), public policy, and strategic communications (DFID, HMRC, Department of Health, and UK nonprofit sector).

Paromita is a rigorous mixed methods researcher who combines qualitative insights with quantitative analysis to uncover systemic disparities in complex intersectional DEI contexts. Her research background spans media & cultural policy, as well as public affairs, with contributions to international projects on media diversity, the impact of the recent crisis on UK & European creative economies, AI adoption in the creative industries, and public trust & ethical journalism producing outputs that have shaped policy interventions.

She now runs a boutique consultancy focused on the intersection of decentralized technologies, cultural production, and systems change. Current projects include designing a research and AI development strategy for a U.S.-based cultural data platform. She holds a PhD in Mass Communication and Public Affairs and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

Dr. Ronda Železný-Green is a digital changemaker creating social learning systems to empower Black people, women, people with disabilities, and other marginalized populations in the technology and education sectors.

Serving as a mobile technologist, trainer, and researcher, Ronda’s nearly 20 years of professional experience spans five continents and the public, private, and civil society sectors. A Black and Indigenous cis woman excelling with

ADHD, Ronda also has extensive experience delivering action-oriented training that integrates the themes of racial equity and justice and gender with global perspectives.

Hallmarks of her career include:

• learning/educating with tech and data;

• championing, coaching, and mentoring women in tech and data; and

• empowering people to use technology as transformative tools to live their best lives.

Damien Ribbans is the lead author of this paper. Damien is the current Operations Director at award-winning social enterprise Noise Solution, and is leading the development of Transceve, spinning it out of Noise Solution into a separate entity.

Damien has a 25+ year career in the third sector, spanning domains such as disability, children’s mental health, homelessness, older people, and marginalised young women. Damien has started several social enterprises and worked in large national charities.

Damien has recently completed two years research study at the Institute for Continuing Education at the University of Cambridge, culminating in a dissertation entitled ‘A Narrative Examination of Motivational Models for Youth Facing Exclusion from Secondary Education Provision: A Review.’.

Simon Glenister is the founder of Noise Solution, a social enterprise pioneering an evidence-based approach that combines one-to-one music mentoring, focused on beat making, with a bespoke digital platform. Simon's work is equally informed by a career as a professional recording artist and his research in digital youth work and well-being, which he pursued during his MEd at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge (2016-2018). The organisation has garnered 24 national awards since 2019 and is consistently ranked as a top 100 UK Social Enterprise by NatWest.

Prompt engineering as a response to promote Equality, Diversity, and Inclusivity representation in Large Language Models.

“AI, in many ways, holds a mirror to society, and while we can "clean" the mirror, addressing what it reflects is equally, if not more, crucial.” (Dwivedi et al, 2023:13).

Introduction

A practitioner/researcher may be tempted to turn to Chat GPT to analyse case studies exploring racial disparities in mental health treatment. However, the mental health professional finds that the Large Language Model (LLM) in question is providing a different set of interventions for particular racial groups for the same mental health condition. For example, the model suggests therapy and community support for White mental health patients, whereas harsher, more disciplinary institutional interventions may be suggested for Black and Brown patients. These subtle yet seemingly unintentional inconsistencies illustrate how LLMs can unwittingly reproduce systemic biases from the data upon which they are trained. Tools such as ChatGPT are increasingly used in domains such as education, research, clinical training, and human resources management, as these organisations seek to benefit from the speed, scale, and efficiencies that LLMs can provide. Without careful and deliberate safeguards, these unexamined outputs pose significant risk, exacerbating the inequalities and inequities present in both the training data and the processing structures of the LLM. Interventions must be developed to mitigate these risks.

LLMs have revolutionised natural language processing (NLP), enabling significant advancements in text generation, automation, and human-computer interaction. However, these models often reflect biases present in the data they are trained on, leading to disparities in representation, reinforcement of societal prejudices, and unfair or unrepresentative responses being provided.

The goal of this project is to develop a toolkit that provides a structured framework for organisations to integrate equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) principles into LLM use through prompt engineering, via a dynamic feedback loop. This dynamic feedback loop provides, we believe, a novel approach to EDI integration and bias mitigation which will contribute significantly not only to the literature, but also to the evolution of LLMs at this emergent stage. Crucially, this project is designed to have real-world impact beyond academia, offering practical value by equipping organisations with actionable tools to assess and improve the inclusivity of their AI systems. As

businesses increasingly adopt LLMs in decision-making, customer interaction, and content generation, the proposed toolkit will offer a timely and scalable solution for embedding EDI into everyday AI practice. By bridging theoretical research and applied implementation, the project stands to shape both scholarly discourse and industrial standards in responsible AI development.

We anticipate this will help organisations stay compliant with emerging AI regulatory frameworks within the UK and EU, while helping to mitigate potential bias, thereby facilitating more accurate representation in LLM outputs. The literature review and findings in this paper identify knowledge and methodological gaps which highlight why the proposed feedback-driven toolkit is timely, cost-effective and commercially viable.

Issues surrounding EDI in LLMs have sparked ongoing debates, with researchers beginning to develop a range of techniques that may mitigate biases while promoting fairer, more representative outputs. Regulatory focus is now being placed on regulation in the AI space, including 'laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence' (EU, 2024), and the Artificial Intelligence Regulation Bill (2025) in the UK. These regulatory approaches contain clear recognition of biases inherent in LLM models (EU, 2024 cl 31, HL, 2025 cl 2(c)) and the need to mitigate such biases, but do not provide guidance as to how this mitigation should be enacted. The debates around LLMs and EDI, coupled with the incoming regulatory pressure, make this an issue that cannot be ignored. Organisations will be legally and morally required to demonstrate, and act in ways that minimise or mitigate, biases in LLMs during their use of these tools.

One emerging solution is prompt engineering to guide LLMs toward more balanced and inclusive responses. By refining prompts, researchers and practitioners can steer model outputs to better reflect diverse perspectives, avoid harmful stereotypes, and ensure equitable representation across different demographic groups. The underlying issues around the lack of diversity in training data for LLMs and the perpetuation of stereotypes explored later in this paper mean that prompt engineering alone is not enough. This proposal is not intended to resolve the fundamental issues around (the lack of) diversity in LLMs, and should not be taken in isolation. Other work investigating more diverse training datasets, diverse engineering and design methods, and other prompt engineering methods must continue. This proposal aims to provide a toolkit for the users of LLMs to begin to diversify the ‘thinking’ of the LLM and the responses provided whilst this other work continues.

Prompt engineering describes a process or set of processes to design and adapt input queries (usually using natural language) when instructing an LLM (Sikha, 2023:3).

Various approaches to prompt engineering have been developed, from ‘zero shot’ (giving the LLM no context), to ‘few shot’ (providing a selection of examples), and ‘chain of thought’ prompting where the user instructs the LLM to carry out instructions via a set of pre-defined steps (Bansal, 2024:17).

Some work has already shown success using human feedback, with Hu et al (2024) showing that consumer-facing LLMs which have been fine-tuned through human feedback show less ‘outgroup hostility’ than other models. Hu et al suggest further finetuning using human feedback could continue this mitigation (2024:69). Importantly, their research also raises ethical concerns regarding the balance between bias reduction and authentic representation (ibid).

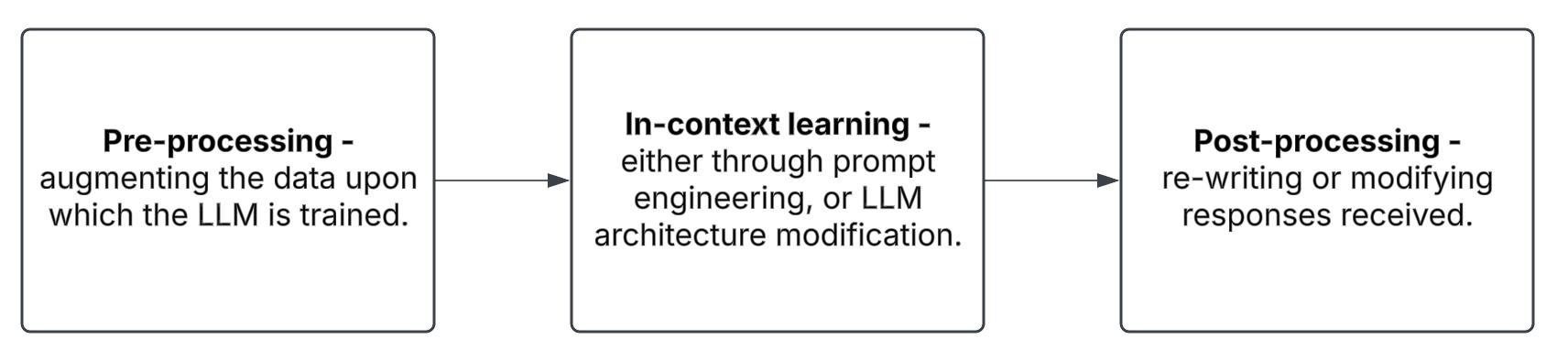

The literature talks about various ways to neutralise the data (Pre/In/Post) using either synthetically generated datasets at a training level, in-context learning (providing examples of the type(s) of response(s) desired as part of a prompt), or an iterative backand-forth approach adjusting prompting based on responses received until you receive an acceptable response. This 'acceptable response' is only acceptable to the user, taking into account their own inherent moral/societal 'biases' and beliefs. This subjectivity means the power remains in the LLM (and its biased datasets) and the end user (with their own inherent conscious and subconscious biases).

This literature review explores current work being done to address bias in LLMs, and evaluates existing research, methodologies, and best practices in fostering EDI through targeted prompt design.

By synthesising findings from recent studies, published from 2023 onwards, this review aims to provide insights into the effectiveness of bias mitigation strategies, highlight challenges in implementation, and discuss future directions for leveraging ethical AI strategies, in particular via the dynamic feedback loop model which we are proposing. Ultimately, understanding how to promote EDI within LLMs is crucial for ensuring that these powerful models serve as inclusive tools, rather than reinforcing societal inequalities.

Methodology

Literature searches were conducted on the 3rd and 4th February 2025, using Google Scholar as the primary search tool, with additional searches on IEEEXplore and the ACM Digital Library.

Boolean searches were conducted across the selected search engines with the following search strings:

“STRATEGIES” AND "PROMPT ENGINEERING" AND “BIAS REDUCTION” AND “LLMS”.

"TECHNIQUES" AND "PARTICIPANT FEEDBACK" AND DIVERSE AND "LLM OUTPUTS”.

"PROMPT ENGINEERING METHODS" AND "REDUCE BIAS" AND "LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS" AND “RETRAINING”.

“PARTICIPANT FEEDBACK" AND “INFLUENCE” AND “DIVERSITY" AND “QUALITY” AND "LLM OUTPUTS”.

"P

ROMPT ENGINEERING TECHNIQUES" AND “LLMS”.

Suitable literature was classified as either ‘direct’ (directly related to the research questions), or ‘indirect’ (indirectly related, but provides useful context). Literature cited in either direct or indirect literature was included as indirect literature, if it provided useful insights or context.

Preprint or non-peer-reviewed papers were either discarded or added as secondary literature if they provided useful or interesting context. Papers not available in English were discarded. Papers that were unavailable (either behind a paywall, or unavailable through one of the researcher’s institutions) were also discarded.

IEEEXplore papers were discarded as irrelevant, as they were not specifically DEIfocused. The ACM Digital Library was also discarded for similar reasons.

These parameters returned a total of 14 primary items and 17 secondary items. These items will be synthesised and discussed below.

Table 1 - List of primary items selected

Author(s)

Year

published

Bansal, Prashant 2024

Bevara et al 2024

Title

Prompt Engineering Importance and Applicability with Generative AI

Scaling Implicit Bias Analysis across Transformer-Based Language Models through Embedding Association Test and Prompt Engineering

Gallegos et al 2024 Bias and Fairness in Large Language Models: A Survey

Hu et al 2024 Generative language models exhibit social identity biases

Kumar & Singh 2024 Bias mitigation in text classification through cGAN and LLMs

Noguer I Alonso 2025 Theory of Prompting for Large Language Models

Raj et al 2024 Breaking Bias, Building Bridges: Evaluation and Mitigation of Social Biases in LLMs via Contact Hypothesis

Raza et al 2024 Safe and Sound: Evaluating Language Models for Bias Mitigation and Understanding

Serouis & Sèdes 2024 Exploring Large Language Models for Bias Mitigation and Fairness

Surles & Noteboom 2024

USA & Sikha 2023

Information system cognitive bias classifications and fairness in machine learning: Systematic review using large language models

Mastering Prompt Engineering: Optimizing Interaction with Generative AI Agents

Zheng & Stewart 2024 Improving EFL students’ cultural awareness: Reframing moral dilemmatic stories with ChatGPT

Zhou et al 2024 Evaluating and Mitigating Gender Bias in Generative Large Language Models

Discussion

Large Language Models are inherent in many aspects of our lives. Artificial Intelligence (AI)-powered systems now use LLMs to make decisions and create their responses. Web searches, design, and music streaming algorithms use AI-powered recommendation engines. Websites are now using agentic ‘chatbots’ for customer service. Scientific and business processes are now leveraging the ability of LLMs to ‘intelligently’ process large amounts of data. Users engage directly with natural language LLM portals such as ChatGPT through deliberate and intentional natural language prompts. Meanwhile, organisations integrate these natural language LLMS into the design of their products and services, covertly shaping user experiences.

The rapid user adoption of LLMs such as ChatGPT, which reached 100 million monthly active users in January 2023, just two months after launch (Hu, 2023), has meant that regulation and oversight of LLMs have not been able to keep pace with their wider usage (Gross & Parker, 2024). While work is now beginning in the regulation space (ibid), these models have grown and become embedded in our societies with little to no ethical or regulatory oversight. This governance is particularly lacking in key areas such as data privacy1, algorithmic bias2, misinformation control3 , intellectual property concerns4 , and accountability5 for AI-generated content. For instance, questions remain about the sourcing and ethical use of training data, the potential for reinforcing societal biases, and the responsibility of AI providers in mitigating the spread of harmful or misleading information. Additionally, oversight is needed to ensure transparency in how these models operate and make decisions, as well as to establish clear legal frameworks governing their use in sensitive domains such as healthcare, finance, and law enforcement.

LLMs are built from, and trained on, large datasets of mostly pre-existing (and some synthetic, artificially created) data (Bansal, 2024). These data are uncurated, meaning it has not been manually reviewed or filtered to remove inherent biases and ensure more proportionate balance. This lack of oversight into uncurated training datasets means that these often unfairly reflect or exhibit societal biases, often reflecting and perpetuating protected and other characteristics (such as age, gender, race, and

1 AI systems often collect and process vast amounts of personal data, sometimes without clear user consent or understanding (Wachter et al, 2016)

2 Biases in AI systems can arise from skewed training data or flawed design choices, leading to discriminatory outcomes (Gallegos et al, 2024).

3 Generative AI can be used to create highly convincing fake content, including deepfakes and AIgenerated news, complicating efforts to curb misinformation (Brundage et al, 2018).

4 AI systems trained on copyrighted material raise legal questions about ownership and fair use, especially when they generate content that closely mimics human creators (Hayes, 2023).

5 There is a need to establish AI accountability for misleading or harmful outputs, to guarantee that actors justify their actions and respond to interrogations, and victims are compensated and perpetrators punished accordingly (Nguyen et al, 2024).

derogatory or exclusionary language) through the outputs generated by the LLM (Gallegos et al, 2024). The biases inherent in these data collection and management processes go on to form the foundations of the LLM, which continues to magnify these biases as the LLM goes on to independently produce outputs.

These biased responses have been shown to disproportionately impact already marginalised and vulnerable communities (Bender et al, 2021, Dodge et al. 2021; Sheng et al. 2021) through producing responses that may trigger and reinforce harmful stereotypes in the minds of users. These stereotypes can lead to unfair automated decision-making, which result in biased outcomes in areas such as hiring, lending, as well as racial profiling in policing6 . The reinforcement of negative racial stereotypes can distort historical narratives by amplifying existing dominant perspectives while marginalising others. As Dwivedi et al note, LLMs merely reflect the biases inherent in the data and modelling upon which they are trained (2023:13). Gallegos et al also make the point that language, as a mechanism of communication which ‘encodes social and cultural processes’, can be harmful in and of itself (2024:1102). LLM models are trained on biased data sets, thereby generating biased responses, reinforcing and perpetuating existing societal inequalities.

Serouis and Sèdes (2024) consider the concepts of bias and fairness, defining bias as “systematic errors that occur in decision-making processes, leading to unfair outcomes.” (ibid:3), with fairness being defined as “a concept that focuses on the ethical and equitable treatment of individuals or groups within automated decisionmaking systems” (ibid:4). The authors argue that these are distinct concepts, with bias representing unfairness within the AI system(s), and fairness encompassing the processes and mitigations undertaken to minimise such biases (ibid:4). Gallegos et al recognise the subjectivity of these biases, positioning them as context- and culturespecific, rooted in complex cultural hierarchies (2024:1102).

This delineation underscores the need for bias mitigation work to take place in both the design and training of LLM models as well as within the strategies developed to mitigate these inherent biases. The (re)training of LLMs is prohibitively expensive, both in cash and environmental terms, requiring significant amounts of hardware, energy consumption, and staff costs (Bevara et al, 2024:2), with AI developers likely to spend close to a billion dollars on a single training run (Cottier et al, 2024:1). This is clearly beyond the means of end users as a practical solution to bias mitigation. Instead, this research focuses on a combination of prompt engineering and in-context learning via a dynamic feedback loop as a directly applicable methodology to promote EDI.

Research is still emerging in the ‘diversity of LLMs’ space (Bevara et al, 2024, Gallegos et al, 2024, Hu et al, 2024, Kumar and Singh, 2024, Raj et al, 2024, Raza et al, 2024, Serouis and Sèdes, 2024, Zheng and Stewart, 2024, and Zhou et al, 2024, amongst

6 Using automated decision making via an LLM to make decisions is likely to perpetuate already existing biases and stereotypes which exist in the uncurated training data upon which the LLM is trained.

others). These works aim to mitigate or eliminate the inherent biases inherent in LLMs in a variety of ways at each stage of the LLM process:

Figure 1 - Stages of the LLM process, adapted from Gallegos et al, 2024

Differences in LLM architecture have been shown to impact the (un)successfulness of prompt engineering-based mitigation strategies, with Bevara et al (2024:26) calling for further research into the interaction between model architectures and prompt success. Predominantly, this bias mitigation work focuses on neutralising the inherent biases using various means including prompt engineering (Siramgari et al, 2023), attempting to implement social psychology concepts such as the Contact Hypothesis (Raj et al, 2024), and re-training on ‘safe’ datasets (Raza et al, 2024), to return bias-neutral data. This neutrality end goal could be problematic. The concept of a ‘neutral’ digital system could perhaps theoretically be created for a point in time, eradicating perceived biases that exist in the current dataset(s) under investigation. LLMs are written by, and used by, humans with perhaps near-infinite means to use current language and create new language. These nuances of human interaction will inevitably continue to be reproduced as the LLM continues to learn from these unpredictable human behaviours. Therefore neutrality, in this sense, is an ever-moving goal (Russinovich et al, 2024:2). Neutralising approaches to biases have been tested before: Colour Blind Racial Ideology (CBRI), which emphasises sameness and equal opportunities, has been shown to be ineffective, instead, it emphasises interracial tension, further highlighting inequality, and denies the inherent racial discrimination prevalent in many, if not all, societies (Neville et al, 2013).

Furthermore, current literature often focuses on biases in isolation, in domains such as gender (Zhou et al, 2024), culture (Zheng and Stewart, 2024), race (Serouis and Sèdes, 2024), and social (psychology) (Raj et al, 2024). Whilst these narrow, domain-specific focuses may support robust academic investigation, these ‘biases’ do not exist in societies in isolation, and these isolated approaches do not allow an appreciation of the intersectionalities involved (Crenshaw, 2013). The work of Wan and Chang highlights intersectional biases in LLMs (2024:6) which are unlikely to be resolved by these isolated-bias methodologies. Addressing intersectionality as part of the approach under investigation here, despite the potential academic complexities involved, is an important step in investigating how an approach can be developed which takes account of, rather than neutralises, the interaction between biases and how these are experienced.

Surles and Noteboom make the point that ‘fairness’ in machine learning is usually conceptualised in two separate ways; statistical fairness (ensuring equal outcomes across different groups), and individual fairness (ensuring that similar individuals receive similar treatment) (2024:492). Traditionally statistical fairness is more commonly applied, perhaps due to the relative ease with which it can be measured. This statistically based approach is more aligned to bias neutralisation, whereas the complexities involved in biases may be better represented using an ‘individual fairness’ approach.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is a technique designed to enhance the accuracy of LLMs, by allowing them to connect to external sources of information in addition to their existing training datasets. RAG is intended to provide grounding for responses generated, allowing the LLM to ‘sense check’ any response before it is provided, and access up-to-date sources of information (Martineau, 2024). Deploying a RAG-based LLM has benefits; it reduces the need for frequent re-training of LLMs and therefore reduces the environmental, social, and resource implications of this retraining, and allows the LLM to access up-to-date information creating a more accurate experience for the end user (ibid). Amugongo et al urge caution with RAG LLMs, with concerns around privacy, bias, hallucination, and data security still present (2024:20). Wu et al (2024) argue that the complexities involved in RAG models, due to their complex, multi-component architecture, has meant that focus has been on developing efficiency within RAG models to limit computing resource utilisation, with little to no focus on the ‘fairness’ of these models (ibid:2). Wu et al propose prompt adjustments, increasing access to documents available to the LLM through the retrieval process, and prioritization of documentation from ‘relevant groups’ to achieve better balance and fairness (ibid:9). Despite these valid concerns, a RAG approach appears to be a promising methodology to explore within the scope of this project. It provides a framework for data grounding7 and selection in the response preparation process. As part of this project, we will explore how this data selection process can be constructed to support the broader bias mitigation strategy.

The literature describes several frameworks that have been designed to measure levels of biases present either to assess biases in LLMs, the responses returned (pre- and post-mitigation), or both. Feldman et al (2015) introduced the concept of ‘disparate impact’, an algorithmic methodology designed to assess unintended discrimination. The authors used this American legal doctrine to determine unintended discrimination, to test for disparate impact and to develop an approach to masking bias whilst preserving relevant information in the data. Wan and Chang describe the Language Agency Bias Evaluation (LABE, 2024:3), a benchmarking framework designed to measure social biases related to language agency, or how individuals or groups are described in texts based on their levels of control, influence, and proactiveness. The LABE framework leverages template-based prompts, an agency classifier, and bias

7 Data grounding is a process of linking AI-generated responses to factual, authoritative sources, ensuring outputs are accurate, reliable, and grounded in real-world knowledge, and avoiding ‘hallucinations’ or untrue assertions.

metrics, to test for gender, racial, and intersectional language agency biases in LLMs. Zhou et al utilised the ‘Multi-Dimensional Gender Bias Classification dataset’ as a tool alongside GenBiT (a tool designed to evaluate gender bias by analysing the distribution of gender terms across a dataset) with which to evaluate gender biases across multiple dimensions (2024:4). These and other applicable frameworks will be assessed for their suitability to this research during the methodology design phase.

Table 2 - summary of bias mitigation strategies

Methodology

Stage

LLM training Development (prelaunch)

Dataset curation Development (prelaunch)

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

Advantages

Allows the LLM architecture to be developed with bias mitigation in mind.

Supports the LLM to reason using less biased data.

During response Allows specific context to be provided to the LLM.

Disadvantages

Prohibitively expensive, and resource intensive.

Curated data will still be inherently biased by the curator.

Needs to be carefully constructed, to allow the correct amount of relevant data to be retrieved.

Prompt engineering

One shot

Pre-response

Pre-response

Multi-shot

Pre-response

Chain of thought

Pre-response

Post-processing

Post-response

Allows specific context to be provided to the LLM.

Allows more in-depth context to be provided to the LLM.

Guides the LLM through steps required to process requirements.

Allows responses to be tailored once received.

Not workable at scale, as the prompt will need to be rewritten for each context.

Not workable at scale, as the prompt will need to be rewritten for each context.

Inherent biases will be present in steps incorporated into the prompt.

Does not provide any opportunity for LLM ‘memory’ to be further developed.

Gallegos et al describe ‘social bias’ as “a subjective and normative term we broadly use to refer to disparate treatment or outcomes between social groups that arise from

historical and structural power asymmetries” (2024:1098). LLMs are not trained to take that subjectivity into account when processing the request, unless the subjective context is provided as input by the humans who trained the LLM. Such contextual subjectivity input is, by definition, subjective itself. Work on debiasing datasets can therefore only ever be subjective to the person or people performing the debiasing work (ibid:1102). Zhou et al position gender bias in LLMs in three pragmatic and semantic aspects; bias from the gender of the person being spoken about, bias from the gender of the person being spoken to, and bias from the gender as of the speaker (2024:4). Whilst their work was specifically gender-focused, this multifaceted positioning can be equally applied to other biases. Bevara et al (2024:3) recognise that “personal inclinations can taint evaluations”, and that variations in individual backgrounds can “…further tilt outcomes” (2024:3). Bevara et al contend that this further highlights an urgency for bias mitigation and fairness.

The proposal

This research seeks to design and test a ‘dynamic feedback loop’ model, positioning the subject of the query (or prompt) at the centre, implementing subject-specific bias definitions with a view to eliciting more individualised and representative, intersectional LLM responses.

The research questions for this proposal are as follows:

● Can the incorporation of feedback from participants themselves influence the diversity and quality of insights produced by LLMs?

● Can a successful dynamic feedback loop model be developed, tested, and refined?

● Can a RAG framework be developed which successfully identifies that person's own subjective biases to inform and ground the LLM response?

In the conversational, natural language data context, what is missing is the originator of that conversation themselves. This approach may provide a paradigm shift from macro to micro, and neutrality to individuality, providing a framework for adoption by others and, crucially, contributing a different perspective to the literature.

Proposed research design

At this stage, we anticipate that the study will take the form of quasi-experimental design primarily under the supervision of two researchers/consultants who specialise in EDI research and AI ethics. We expect the project to have a duration of two years. The framework we propose will be developed in accordance with three earlierreferenced studies (Wan & Chan 2024, Zhou et al 2024, and Fieldman et al 2015), utilising the knowledge and learning which has already taken place in the development of these frameworks. This will involve conducting bias evaluation (using GenBit and

LABE classifiers), initial bias mitigation via prompt engineering, as well as iterative refinement via a dynamic feedback loop.

The research team have data available to them from Noise Solution, a social purpose organisation providing evidence-based music mentoring to youth at risk across the East of England. Noise Solution is using an AI-powered engine to extract social impact insights from conversational data. Consent to research is already sought from Noise Solution participants. Additional data may also be available from other sources using the same engine, depending on explicit and informed consent being gained.

Generated responses from a variety of LLMs (including ChatGPT, Llama, Mistral) will be the unit of analyses for this study. We will also explore recruiting a group of EDI and AI ethics experts who will act as human evaluators, in addition to our senior researchers supervising the study.

Findings will be consolidated into a report with a proposed framework that we can share with interested stakeholders, from LLM developers to end-users and other research institutions and colleagues. The aim of the study will be to answer the research questions outlined above, in order to develop and share a ‘blueprint’ for bias mitigation which is able to be adopted by other researchers, users of LLMs, and LLM developers themselves.

Ethical considerations

As already discussed, regulation in the AI/LLM domains is nascent so we cannot rely on existing regulatory or ethical frameworks to guide our research in these areas. Ethical discussions such as the ethical framework developed by Porsdam Mann et al (2023, 2024) and the ‘Oxford Statement’ (2024) help to provide some guidance. Full ethics consideration will be given to this project, with the appropriate safeguards implemented.

Our research is intended to provide much-needed understanding of how EDI can be better integrated and operationalised within LLM usage. It is important to be mindful of unintended consequences such as overreliance on automated processes without ‘human in the loop’, unintended introductions of new biases, or privacy concerns (Raza et al, 2024:6).

Schiff et al (2024) have investigated the emerging field of AI ethics and governance auditing, making comparisons with the much more established fields of financial and business ethics auditing. Importantly, Schiff et al state that “AI principles are not enough to prevent unethical outcomes” (ibid:2), adding to the discourse calling for more robust governance.

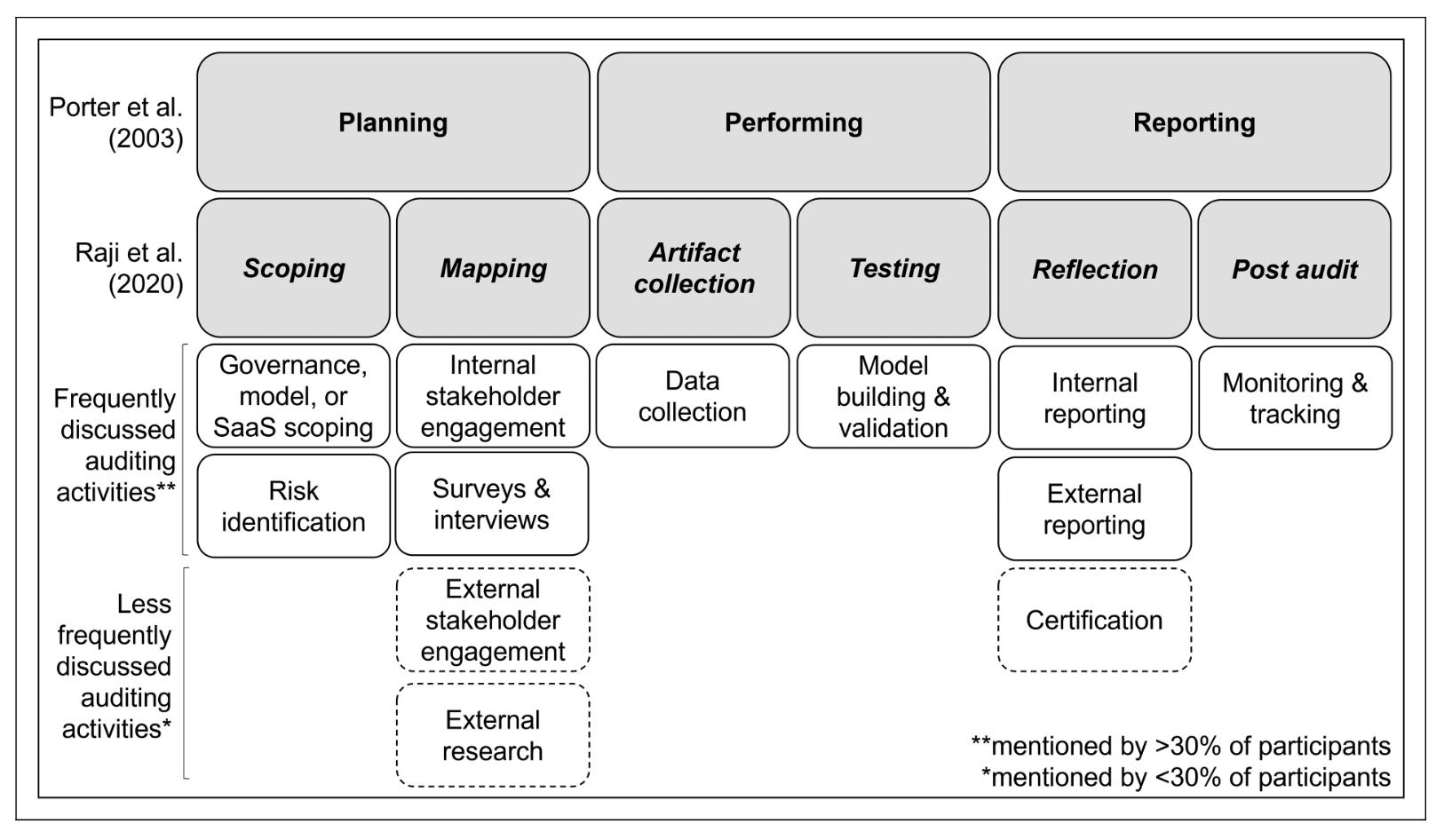

Schiff et al have mapped AI ethics audit activities discussed by the participants of their study against existing auditing frameworks:

Figure 2 - Activities discussed in AI ethics auditing, from Schiff et al (2024:10)

This provides a useful structure with which to design an ethical assessment for this project, and will be considered and adapted as appropriate as part of the full research design.

In developing a methodology that places ‘the subject’ at the centre, our research needs to be mindful of the subject’s right to privacy, acting transparently, and with the subject’s best interests in mind. Taking a subjective approach to defining bias requires nuance and must not lead to the profiling of study participants. The development of a clear and transparent framework should guide fair and proportionate judgments in the use of AI systems - particularly in addressing and mitigating the inherent biases embedded within LLMs.

References

Allport, G. W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Social Problems.

Amugongo, L.M. et al. (2024) Retrieval augmented generation for large language models in Healthcare: A systematic review [Preprint]. doi:10.20944/preprints202407.0876.v1.

Aroyo, L., Taylor, A., Diaz, M., Homan, C., Parrish, A., Serapio-García, G., Prabhakaran, V. and Wang, D., 2023. Dices dataset: Diversity in conversational ai evaluation for safety. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, pp.53330-53342.

Artificial Intelligence (Regulation) Bill [HL] (2025) House of Lords Bill [76]. Available at: https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3942 (Accessed: 13 March 2025).

Bansal, P. (2024) ‘Prompt engineering importance and applicability with Generative AI’, Journal of Computer and Communications, 12(10), pp. 14–23. doi:10.4236/jcc.2024.1210002.

Bender, E.M. et al. (2021) ‘On the dangers of stochastic parrots’, Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, pp. 610–623. doi:10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Bevara, R.V. et al. (2024) ‘Scaling implicit bias analysis across transformer-based language models through Embedding Association Test and prompt engineering’, Applied Sciences, 14(8), p. 3483. doi:10.3390/app14083483.

Brundage, M., Avin, S., Clark, J., Toner, H., Eckersley, P., Garfinkel, B., Dafoe, A., Scharre, P., Zeitzoff, T., Filar, B. and Anderson, H., 2018. The malicious use of artificial intelligence: Forecasting, prevention, and mitigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.07228.

Cachat-Rosset, G. and Klarsfeld, A. (2023) ‘Diversity, equity, and inclusion in Artificial Intelligence: An evaluation of guidelines’, Applied Artificial Intelligence, 37(1). doi:10.1080/08839514.2023.2176618.

Chen, H., Waheed, A., Li, X., Wang, Y., Wang, J., Raj, B. and Abdin, M.I., 2024. On the Diversity of Synthetic Data and its Impact on Training Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.15226

Cottier, B., Rahman, R., Fattorini, L., Maslej, N. and Owen, D., 2024. The rising costs of training frontier AI models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.21015

Crenshaw, K., 2013. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In Feminist legal theories (pp. 23-51). Routledge.

Dodge, J. et al. (2021) ‘Documenting large Webtext corpora: A case study on the Colossal Clean Crawled Corpus’, Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing [Preprint]. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.98.

Dwivedi, Satyam, Ghosh, S. and Dwivedi, Shivam (2023) ‘Breaking the bias: Gender fairness in LLMS using prompt engineering and in-context learning’, Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 15(4). doi:10.21659/rupkatha.v15n4.10.

European Union Regulation 2024/1689 (2024) 'Laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence', Official Journal L 168, pp. 1–47. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1689 (Accessed: 13 March 2025).

Feldman, M. et al. (2015) ‘Certifying and removing disparate impact’, Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pp. 259–268. doi:10.1145/2783258.2783311.

Gallegos, I.O. et al. (2024) ‘Bias and fairness in large language models: A survey’, Computational Linguistics, 50(3), pp. 1097–1179. doi:10.1162/coli_a_00524.

Gross, A. and Parker, G. (2024) UK’s AI Bill to focus on CHATGPT-style models, Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/ce53d233-073e-4b95-8579-e80d960377a4 (Accessed: 07 February 2025).

Hayes, C.M. (2023) ‘Generative Artificial Intelligence and copyright: Both sides of the black box’, SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4517799.

Hu, K. (2023) CHATGPT sets record for fastest-growing user base - analyst note | reuters, Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpt-sets-record-fastest-growing-userbase-analyst-note-2023-02-01/ (Accessed: 07 February 2025).

Hu, T. et al. (2024) ‘Generative language models exhibit social identity biases’, Nature Computational Science, 5(1), pp. 65–75. doi:10.1038/s43588-024-00741-1.

Kumar, G. and Singh, J.P. (2024) ‘Bias mitigation in text classification through cgan and LLMS’, Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy [Preprint]. doi:10.1007/s43538-024-00371-1.

Martineau, K. (2024) What is retrieval-augmented generation (rag)?, IBM Research. Available at: https://research.ibm.com/blog/retrieval-augmented-generation-RAG (Accessed: 19 March 2025).

Neville, H.A. et al. (2013) ‘Color-blind racial ideology: Theory, training, and measurement implications in psychology.’, American Psychologist, 68(6), pp. 455–466. doi:10.1037/a0033282.

Nguyen, L.H., Lins, S., Renner, M. and Sunyaev, A., 2024. Unraveling the Nuances of AI Accountability: A Synthesis of Dimensions Across Disciplines. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.04247.

Noguer I Alonso, M. (2025) Theory of prompting for large language models [Preprint]. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5013113.

Oxford statement on the responsible use of generative AI in adult social care (2024) Oxford Statement on the responsible use of generative AI in Adult Social Care | Ethics in AI. Available at: https://www.oxford-aiethics.ox.ac.uk/oxford-statement-responsible-use-generative-ai-adultsocial-care (Accessed: 10 February 2025).

Porsdam Mann, S. et al. (2023) ‘Generative AI entails a credit–blame asymmetry’, Nature Machine Intelligence, 5(5), pp. 472–475. doi:10.1038/s42256-023-00653-1.

Porsdam Mann, S. et al. (2024) ‘Guidelines for ethical use and acknowledgement of large language models in academic writing’, Nature Machine Intelligence, 6(11), pp. 1272–1274. doi:10.1038/s42256-024-00922-7.

Priyadarshana, Y.H. et al. (2024) ‘Prompt engineering for Digital Mental Health: A short review’, Frontiers in Digital Health, 6. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2024.1410947.

Raj, C. et al. (2024) ‘Breaking bias, building bridges: Evaluation and mitigation of social biases in LLMS via contact hypothesis’, Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 7, pp. 1180–1189. doi:10.1609/aies.v7i1.31715.

Raji ID, Smart A, White R, et al. (2020) Closing the AI accountability gap: Defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, pp.33–44. https://doi.org/10.1145/3351095.3372873.

Raza, S., Bamgbose, O., Ghuge, S. and Pandya, D., Safe and Sound: Evaluating Language Models for Bias Mitigation and Understanding. In Neurips Safe Generative AI Workshop 2024

Roche, C., Wall, P.J. and Lewis, D. (2022) ‘Ethics and diversity in artificial intelligence policies, strategies and initiatives’, AI and Ethics, 3(4), pp. 1095–1115. doi:10.1007/s43681-022-00218-9.

Rubei, R., Moussaid, A., Di Sipio, C. and Di Ruscio, D., 2025. Prompt engineering and its implications on the energy consumption of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.05899

Russinovich, M., Salem, A., Zanella-Béguelin, S. and Zunger, Y., 2024. The Price of Intelligence: Three risks inherent in LLMs. Queue, 22(6), pp.38-61.

Sarker, I.H. (2024) ‘LLM potentiality and Awareness: A position paper from the perspective of trustworthy and responsible AI modeling’, Discover Artificial Intelligence, 4(1). doi:10.1007/s44163-02400129-0.

Schiff, D.S., Kelley, S. and Camacho Ibáñez, J. (2024) ‘The emergence of Artificial Intelligence Ethics auditing’, Big Data & Society, 11(4). doi:10.1177/20539517241299732.

Serouis, I.M. and Sèdes, F., 2024, August. Exploring large language models for bias mitigation and fairness. In 1st International Workshop on AI Governance (AIGOV) in conjunction with the ThirtyThird International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence

Shams, R.A., Zowghi, D. and Bano, M. (2023) ‘Ai and the quest for diversity and inclusion: A systematic literature review’, AI and Ethics [Preprint]. doi:10.1007/s43681-023-00362-w.

Sheng, E. et al. (2021) ‘Societal biases in language generation: Progress and challenges’, Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers) [Preprint]. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.330.

Shofman, M. et al. (2024) Negative preference reduction in large language model unlearning: An experimental approach [Preprint]. doi:10.22541/au.172910500.09952481/v1.

Siramgari, D., Sikha, V.K. and Korada, L. (2023) ‘Mastering prompt engineering: Optimizing interaction with Generative AI agents’, Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences Technology, pp. 1–8. doi:10.47363/jeast/2023(5)e117.

Surles, S. and Noteboom, C. (2024) ‘Information system cognitive bias classifications and fairness in machine learning: Systematic review using large language models’, Issues in Information Systems, 25(4), pp. 491–506. doi:10.48009/4_iis_2024_138.

Thistleton, E. and Rand, J. (2024) Investigating deceptive fairness attacks on large language models via prompt engineering [Preprint]. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4655567/v1.

Torres, N. et al. (2024) ‘A comprehensive analysis of gender, racial, and prompt-induced biases in large language models’, International Journal of Data Science and Analytics [Preprint]. doi:10.1007/s41060-024-00696-6.

Wachter, S., Mittelstadt, B. and Floridi, L. (2016) ‘Why a right to explanation of automated decisionmaking does not exist in the General Data Protection Regulation’, SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2903469.

Wan, Y. and Chang, K.W., 2024. White Men Lead, Black Women Help: Uncovering Gender, Racial, and Intersectional Bias in Language Agency. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.10508.

Wu, X., Li, S., Wu, H.T., Tao, Z. and Fang, Y., 2024. Does RAG Introduce Unfairness in LLMs? Evaluating Fairness in Retrieval-Augmented Generation Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.19804.

Yang, J., Wang, Z., Lin, Y. and Zhao, Z., 2024, December. Problematic Tokens: Tokenizer Bias in Large Language Models. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData) (pp. 6387-6393). IEEE.

Yi, D.O.N.G., Mu, R., Jin, G., Qi, Y., Hu, J., Zhao, X., Meng, J., Ruan, W. and Huang, X., Position: Building Guardrails for Large Language Models Requires Systematic Design. In Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning

Zheng, Y. (Danson) and Stewart, N. (2024) ‘Improving EFL students’ cultural awareness: Reframing moral dilemmatic stories with chatgpt’, Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, p. 100223. doi:10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100223.

Zhou, H., Inkpen, D. and Kantarci, B. (2024) ‘Evaluating and mitigating gender bias in generative large language models’, International Journal of Computers, Communications & Control, 19(6). doi:10.15837/ijccc.2024.6.6853.