Palgrave MacMillan, New Directions, Youth Music and measurement

Noise Solution, beats, stories and numbers: A digital outcomes capture strategy that improves well-being outcomes

Simon Glenister, MEd (Cantab)

Introduction

Noise Solution is a social enterprise delivering around six hundred hours a month of 1:1 mentoring, in music technology and production, across the East of England. Music producers are paired with young people that mental health teams, schools and local authorities are struggling to engage. Noise Solution’s focus is using music mentoring as a route to create stronger relationships around each participant leading to improved subjective well-being. We focus on well-being as an organisation because, as this chapter explores, improvements in well-being lead to improvements in social, educational and health outcomes. Fundamental to the organisation is an ability to demonstrate those outcomes.

This chapter reflects on a number of themes that those concerned with an outcomes capture strategy might consider. Things like the importance of a data strategy in capturing outcomes, and how we use technology alongside face-to-face engagement to best build relationships with and around our participants. How we use evidenced literature, like Self Determination Theory, to theorise how that engagement might work and inform our fusion of face-to-face and technological design decisions. How we can use technology to best capture, measure and present changes in well-being. And finally a glimpse of what AI is starting to offer in

understanding, analysing and presenting the data that a well-thought-out data capture strategy provides.

Who we make music with and how

Noise Solution receives its referrals from three main sectors: schools, statutory organisations in mental health, and UK Local Government services such as social services.

Young people are normally referred to Noise Solution because professionals, in roles such as social workers or mental health specialist, might have concerns about a young person. They might feel they are ‘stuck’ in negative patterns that the professional is struggling to shift. The young people’s challenges often, but not exclusively, might present as school anxiety leading to attendance challenges, lack of motivation, low self-esteem, low engagement, more general anxiety, depression, children in care settings struggling to thrive or students at risk of exclusion. Or, more likely, a combination of the above, with trauma often as a root cause or symptom in the mix.

Traditional deficit-based approaches often delivered by social work, educational and mental health teams, tend to identify ‘problems’ and try to provide solutions. In my experience there can be a mindset at play that the young person is ‘a problem, to be solved’, it’s a deficit-based approach. As an organisation we are much more interested in a strengths-based approach.

When a Noise Solution musician engages with a young person the musician doesn’t ask what issues there may be and makes it clear that there is no agenda, learning goal and no curriculum or exam expected. It’s important to note here that the referral process ensures we have relevant information on each participant in regard to vital need to know information. However, each engagement is delivered in a non-medicalised, non-problematised way. Where

every session is led by that young person’s interests in what they would like to create, with a focus on having fun and building a relationship. It is one-to-one project-based music mentoring, that is participant-led and often, though not exclusively, centred around music technology (making beats).

Whatever their level of experience, over a minimum period of 20 hours and often much more, the participant is consciously supported to feel ‘in control’ to contribute their own ideas. Musicians lead with questions such as “What do you listen to? Would you like to create that? How many of those creative decisions were yours?” The focus is on the participant’s successful and quick practical creation of music that they feel they own, often using Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) to create genres of music that are culturally relevant to each participant. As such, we generally tend to be creating electronically driven genres of music, including but not exclusive to Hip Hop, Grime, Drill, Drum and Bass.

A digital outcomes capture strategy

The reality for organisations, like Noise Solution, is that if the positive outcomes of its work are not captured, they are simply not visible to funders to either validate past funding or win funding for new work. In part, our answer to this is our development of a CRM system (customer relationship manager). Within that platform Noise Solution has created our own bespoke social media-esque experience for participants, their families and their professionals. While it presents and acts as a social media platform it is not open to the world but securely closed. Within every session, each participant and their musicians can capture and post video highlights of each music mentoring session to an individual’s digital story feed. Every session sees videoed reflective conversations between participants and their musician, discussing

what’s working, what’s not and how that makes them feel, all recorded and posted to their feed for targeted sharing. This content is posted and shared weekly, with a community of significant adults relevant to each participant (and them only). These family or key workers are each identified as important by the participant and invited to join an individual’s feed. This allows family and key workers to be digitally ‘in the room’ (without having to be there physically). This digital community can contribute actively by viewing and commenting on the posts from each session. Currently, around 500 hours of mentoring occur a month, with video reflections from those sessions alone accounting for around twenty to thirty hours of video, every month.

Noise Solution’s platform doesn’t just capture the stories participants create about their experience, any other data collected relating to ‘any and all’ aspects of the running of the organisation exist within our CRM. Every process (many automated within the platform) from start to end of every person we work with is also captured in this same platform. A 100% paperless data strategy from referral, to, contract management, safeguarding, attendance, the stories themselves, live well-being analysis (more of which later), the automated onboarding of families and professionals, exit interviews, and much more all happens in this one digital space. Data is collected not as a bolt-on to be analysed later, but as part of an ongoing rolling process as it progresses. Data collection is rolled into the very culture of every interaction with musicians, participants, professionals and families. That we can then report on by age, gender, contract, geography, in any way we wish. Dashboards provide live analysis of all aspects of this data, becoming an inherent part of the organisation's analysis of our performance. As importantly those dashboards and the reports that feed them are set up to trigger warnings or processes when something that should happen doesn’t. Having all your

data in one platform, that tells you when things are not happening, that’s a mind shift that is incredibly helpful in becoming a more efficient organisation.

As an organisation Noise Solution has been on a sixteen-year journey developing how to capture the impact or changes in the lives of participants. In youth work and third sector language these changes in participant’s lives are termed ‘outcomes’ and are a way of understanding more deeply the actual impact of an intervention. Outcomes are often confused with outputs. Outputs are what we can count - things like counting how many people attended and they don’t actually tell us much. They have historically been a mainstay of evaluation though. Capturing outcomes on the other hand demonstrates that change has occurred for someone rather than they just turned up. More and more it is demonstrating outcomes not outputs that determine if an organisation receives funding from commissioners and funders. Noise Solution’s capturing of outcomes (using both digital stories and number data) started as a means to answer questions from health and educational commissioners about the value of the service to them. What became apparent early on in that journey was that the actual sharing of these digital story feeds not only captured outcomes but contributed to improving outcomes for participants, families and professional key workers.

Historically, program evaluation is typically carried out after an intervention has occurred. In contrast, Noise Solution’s use of these digital stories, using participant reflections, meant those making content and those viewing (including the participant) could evaluate the participants' experience live week by week. With the participant’s actual voice being central to every weekly reflection/evaluation. That sharing of reflections, then projected as it is onto the screens of parents/professionals weekly updated in new posts to their feed can and does

shift perceptions of the participant from being a problem to be ‘fixed’ to someone successfully achieving.

Drop the term ‘outcomes analysis’ into a conversation with someone in the third sector and you’ll often be met with an eye roll and cynicism. It can be viewed as something that ‘gets in the way’ of the real work, as you collect data, often for someone else. As such this idea that a means of capturing impact could contribute to improving outcomes is unusual. When done well I firmly believe good outcomes capture can solve most organisational issues, from operations to finances to funding. For example, Noise Solution is receiving significant recognition for both the outcomes we achieve and how that data is captured and evaluated.

In 2024 we were listed in the NatWest Social Enterprise Index as a top 100 UK-performing Social Enterprise (for the fifth time). Since 2026 we’ve been shortlisted or won 23 national awards. In 2024 beating Microsoft in the Innovation in AI category at the National Digital Revolution Awards (more on which later). Other shortlisted awards nationally include Music Teacher Magazine, Social Enterprise UK and the Arts Council’s Digital Trailblazer Awards and Children and Young People Now magazine awards. These achievements are, if nothing else external validation we’re doing the work and that sits well in any contract or funding application we submit.

Young People’s Noise Solution ‘Digital Story’

At the time of writing, participants take part in a minimum of twenty hours of mentoring. Starting with ten hours in their home, school or local community space and then often moving to a local recording studio. As mentioned, as a regular part of the culture of each session, highlights are captured via audio/video/text and posted to a participant’s story or feed. These

might include the moment the participant created something they are proud of, the participant demonstrating a new skill or achievement, or the posting of a track they created with or without an accompanying video. It’s the musician’s role to help participants contribute to their digital story, curating a ‘narrative’ that those watching the digital story can engage with. Musicians may choose what to capture to best demonstrate the ‘story’ of each session.

In a way that supports participants to feel ‘seen’ as in control and successful at their endeavours. But always with the co-created consent of the participant. Participants have full editorial control over what's shared, and with who. I’m hammering home a point but at the end of all sessions, participants are always encouraged to reflect on video, in conversation with their musician, about their thoughts and feelings at the end of the session. If they don’t want to of course we don’t force the issue.

Guests to the digital story are mostly family and or carers but also key workers such as social workers, mental health or school professionals. These people experience the ‘Story’ feed as they would any other social media feed (except it is privately protected and closed to the outside world). Because of the way the platform onboards everyone in a young person’s ‘group’ they can then receive automatic notification via email weekly when the ‘Story’ has been updated, with a link taking them back to the feed to view and comment on each session.

See figure 3 below for an example post, where someone is responding to a young person showcasing that week’s track and reflecting on it.

Fig 1. An example post from within a Noise Solution ‘Story’ feed, n.b you can see comments reacting to the video reflection, alongside the ability to ‘like’ the post

Just as youth work holds co-production and user involvement at its core, and upholds evaluation that includes, rather than excludes the participant, Participants lead their own weekly evaluation by reflecting in conversation on what is and isn’t working in their own words. I believe, these reflections, being of the culture of each session, help internalise (and share) a sense of success within an evolving story weekly for a participant. It’s a (huge) side benefit that it also makes us better able to make a case for using the service as each participant curates their own case study - co created with the comments of their family and professionals. Noise Solution’s primary goal is to use these stories to mirror the participants’ success back at themselves and enable them to experience feeling ‘seen’ and recognised as

becoming successful by those whose opinions they value. All this qualitative data though accumulates naturally week by week as part of every set of sessions. 600 hours a month, creating upward of twenty to thirty hours of video in reflections. That’s a lot of case studies.

Self Determination Theory

Following my MEd research at the Education Faculty of Cambridge University (2016-18), I operationalised Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Deci and Ryan 2000) as a theoretical framework to inform the majority of decisions made by Noise Solution. As such SDT informs the design of our face-to-face intervention, internal communication, external communication, and digital infrastructure, which hosts young people's stories.

Self Determination Theory (SDT) provides a macro-level framework for understanding the factors essential for intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and for promoting well-being.

According to SDT, similarly to how humans require physical necessities such as food, water, and shelter, there are three Basic Psychological Needs (BPN) that must be present for humans to thrive and attain well-being. These three BPNs are autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Indeed, if any of these needs are unfulfilled it can lead to pathologies and illbeing, as argued by Ryan & Deci below:

‘…by failing to provide supports for competency, autonomy and relatedness, not only of children but also of students, employees, patients, and athletes, socialising agents and organisations contribute to alienation and ill-being.’ (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 74).

In Nagpaul and Chen's (2019) literature review, where SDT has been used successfully with youth in challenging circumstances, all studies cited showed improved outcomes when encouraging basic psychological needs (BPN) of autonomy, competence and relatedness.

Noise Solution’s implementation of SDT utilises music as an engagement activity within which to encourage BPN. For example: Autonomy is fostered by asking participants if they wish to participate, also allowing participants to co-negotiate project goals and choose which genre of music is created, what is captured and who it is shared with. Competence is encouraged by quick mastery of music technology (predominantly ‘beat making’ within DAWS or Digital Audio Workstations), where the focus is on quick wins rather than years of study of scales or reading notation. The musician guides the achievement of quickly achievable (great sounding) co-negotiated musical goals. Relatedness is supported both internally between the relationship with the musician and also externally via the community both witnessing and contributing to the ‘Digital Stories’ within the digital platform. Family and key workers view and comment. This two-way communication allows participants to experience relatedness as they ‘see’ themselves as succeeding and also recognised as succeeding by others. With benefits for both participants and stakeholders.

Previous research (DeNora and Ansdell 2014) has found that narratives that include commentary from stakeholders have the potential to enhance feelings of accomplishment alongside music engagement. The process of others observing and participating in the narrative can play a vital role in reinforcing any reflective self-realisations, such as those in the weekly video reflection. Davis and Weinshenker (2010) discuss a similar process in the context of the research field of digital storytelling. Engagement and feedback from others about a ‘Digital Story’ and through conversations sparked by it, can aid in internalising any newly created narrative of success. According to Kegan (1994), for young people to reflect and change, adults need to be present to help scaffold the reflection of experiences for young people in order for self-reflection and change to occur.

“Self-reflection is a developmental accomplishment… they must step outside of their immediate categorical reality. Their experience must be transformed into an object of contemplation” (Kegan, 1994, p. 32)

Figure 2, above, visualises this relationship between participant, family/carer and key person. The ‘Story’ enables multiple stakeholder adults to be present and be part of that scaffolding. The digital ‘Story’ tool therefore may act as a transitional object for contemplation, facilitating reflection and bolstering the basic psychological need of relatedness. Where the relationship between the musician and participant already focuses on encouraging all three basic psychological needs. The fulfilment of BPN as shown in figure 2, should therefore in theory contribute to positive well-being outcomes.

Well-being as an Outcome

Improved well-being through arts engagement is widely held to bring benefits, especially for the cohort of young people that Noise Solution works with. However, ‘well-being’ is a complicated area, and participants' feelings about their well-being are subjective. As such, we should recognise that there are complexities of attribution around what is or isn’t contributing to changing well-being levels for individuals.

On the plus side, Meta-analysis studies have found that increased well-being improves shortand long-term subjective health outcomes (Howell et al. 2007, p. 83). While art/culture has also been cited as being a vehicle for improving social cohesion and well-being (Fancourt, Warran & Aughterson, 2020, p. 3). Educational attainment too appears to benefit when well-

being is higher (Gutman & Vorhaus, 2012, p. 3). Therefore, improvements in well-being appear to bring desirable outcomes, with arts as a recognised vehicle to do so. But debate remains as to how best to measure it. For example, arts organisations have often been criticised in the past for relying too heavily on qualitative data and for not being rigorous enough in their analysis of it (Deane, Holford, Hunter, & Mullen, 2015, p. 133).

Within this context, Noise Solution also recognises the importance of measuring well-being as a quantitative measure. We have been collecting data using the Shortened Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-being scale, developed in partnership between academics and the NHS, and known as SWEMWBS, since 2015 (Warwick Medical, 2021). The appropriateness, methodology and accuracy of this NHS scale is discussed in more detail in the results section of this chapter. An initial external study conducted in 2016 showed that despite a small sample size (n34) of the SWEMWBS data, Noise Solution’s impact on well-being was statistically significant (The Social Investment Consultancy, 2016, p.18). Statistical significance is determined using mathematical analysis and determines if the results are influenced by chance or not. It’s a desirable outcome because if Noise Solution’s well-being outcomes are statistically significant then improved well-being would be a statistical probability for those who complete a set of sessions. Given the benefits identified with improved well-being this should be a compelling argument for commissioners.

Measuring ‘well-being’ Change

We’ve placed an easy means within each participant's ‘digital story’ feed to collect SWEMWBS well-being scale data. Participants complete this seven-item questionnaire designed to give a subjective well-being level, with question responses being scored on a one to five Likert scale.

The numbers for each answer are summed. The scale is collected both at the beginning and end of a participant's time with Noise Solution (normally 10 weeks apart) giving two summed scores representing changing levels of well-being. This allows for comparative analysis (or journey travelled data) of their start and end subjective level of well-being. Further automatic analysis within the platform occurs enabling the creation of dashboards for internal use that give us the ability to benchmark and compare Noise Solution’s SWEMWBS results against national averages. These national averages come from peer reviewed literature and rely on results that have already been collated at scale (n30000). Ours is a live automated pipeline of well-being data that measures feelings and turns them into understandable graphs that are nationally benchmarked.

Youth Well-Being Results: Pre-Post Change and vs the National Average

Figure 3 below sets out a sample of three hundred and eighty-eight sets of SWEMWBS start and end scores contributed by Noise Solution participants. Demographically, we see one hundred and five participants below the age of thirteen, One hundred and seventy-eight between the ages of thirteen and fifteen. Eighty-five participants between sixteen and twentyfour. Thirteen participants between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-nine and with seven aged over thirty-nine. Regarding gender, twenty-four per cent of participants identified as female, non-binary or preferred not to say.

Fig 3. Age and gender split of average start and end SWEMWBS scores]

The important columns here to focus on are the age range, sum of score difference and record count. The meaningful change threshold for SWEMWBS, identified in Shah et al.’s 2022 paper on the sensitivity to change of the SWEMWBS scale, is any difference between one and three (Shah et al., 2022, p. 1). If the number is +1 or higher in the average score difference column then that’s a meaningful change in well-being for that demographic. As you can see it is +1 or above across the board.

Of note is that the greatest change between start and end scores occurs amongst sixteen-to twenty-four-year-old women or those choosing not to state gender, where we see an average change of 4.10 (n31). As a practitioner and CEO looking to demonstrate outcomes, our ability to granularly see these sorts of well-being changes and evaluate changes demographically has

led to far better conversations with commissioners and funders, as we can clearly demonstrate where and with who we see better well-being outcomes.

Benchmarking is vital. In isolation these scores could be viewed with suspicion. In Figure 4 below, we see a broader overview of Noise Solutions' three hundred and eighty-eight SWEMWB scores compared against a UK national average score. Evaluative work done by the team developing SWEMWBS saw the Warwick and Edinburgh team collate 30,000 responses to the scale from various organisations from across the UK. This enabled that team to establish population score bandings and averages. From a practical perspective, Noise Solution can evaluate its own SWEMWBS scores against population averages split into bandings of low, medium and high levels of well-being. (Ng Fat, 2016). The charts below show three shades of bandings. These represent delineations of Noise Solution results below the UK national average (darkest), within two points (mid) of the UK national average, and above the UK national average SWEMWBS scores (lightest).

Fig 4. Start and end SWEMWBS scores compared against the UK national average derived from a sample of n30,000]

Compared to national averages, seventy-five per cent of participants scored their subjective well-being as sitting within the low-level banding pre-intervention. Post-intervention, low

levels of well-being dropped to fifty-four per cent. Eighteen percent started with SWEMWBS scores above the UK average. Post-intervention, that doubled to thirty-seven per cent.

Well-Being Results: Statistical Significance

In addition to scrutinising demographic categorisations and providing national comparisons against established well-being averages, the cloud-based platform employed by Noise Solution systematically examines well-being data through various statistical methodologies. Specifically, the SWEMWBS data undergoes automatic analysis to ascertain both statistical significance and the extent of change in well-being. This involves employing a T-test to determine statistical significance while calculating the range of well-being change using Cohen's method. For a more detailed exploration of the application of these statistical analysis methodologies by 'Noise Solution,' see the study titled 'Changes in Well-being of Youth in Challenging Circumstances: Evaluation After a 10-Week Intervention Combining Music Mentoring and Digital Storytelling' (Glenister, 2018). However, an explanation of the basic concept of statistical significance is needed.

As mentioned earlier, statistical significance denotes the outcome of a computation that establishes the likelihood of a particular result. In the context of this study, the focus is on determining the probability of an enhancement in well-being by comparing sets of initial and end SWEMWBS scores. The resulting calculation is expressed as a 'p' value, where 'p' signifies probability. To be deemed as having eliminated the element of chance in observed outcomes, the calculated 'p' value must surpass a 95% probability threshold. Any 'p' value falling below 0.05 (or within the remaining 5% of the 95% benchmark) demonstrates the result as

statistically significant. The lower 'p' value the higher the probability and therefore a more favourable outcome.

In the specific analysis conducted on the same dataset as depicted in Figure 3 within the Noise Solution’s cloud-based platform (comparing initial and concluding SWEMWBS scores), the statistical significance has been consistently upheld at a 'p' value of 0.001. Additionally, a notable shift greater than 0.50 has been observed, categorising it as having a ‘large’ effect in the context of changes between initial and concluding scores (See Glenister 2018 for a description of the Cohen calculation of effect size). Noise Solution has consistently maintained this level of statistical significance over the past seven years.

Taken as a whole, there is, therefore, evidence to suggest that improved well-being leads to positive outcomes in engagement, education, health, and social outcomes. It is, and has been for seven years now, a statistical probability that Noise Solution participants' well-being will improve if they complete a set of sessions (there is a year-on-year 75% completion rate). This then provides a significant weight of evidence as to the efficacy of Noise Solution’s approach.

Questions may be asked, particularly for those outside academic circles, as to why we delve so deeply into the intricacies of the data. As previously stated, the demonstration of efficacy necessitates comprehensive coverage across various domains, encompassing numerical, narrative, and financial dimensions. The justification and transparency of how you arrive at these results is equally important when talking to commissioners. In my experience,

irrespective of the focus on outcomes, different commissioners tend to respond favourably to either narrative, numerical, or financial data.

While no single approach is definitive in showcasing efficacy, the amalgamation of these diverse strands suggests a high probability or gives a believable ‘steer’ of positive outcomes to a broader audience. Quantitative data is a vital component of this breadth-of-data approach, and we try to present it in a manner that is both transparent and firmly grounded in scientific principles. Deliberately incorporating academic methodologies, subject to external peer-reviewed oversight, into our analyses is about presenting realistic and believable results.

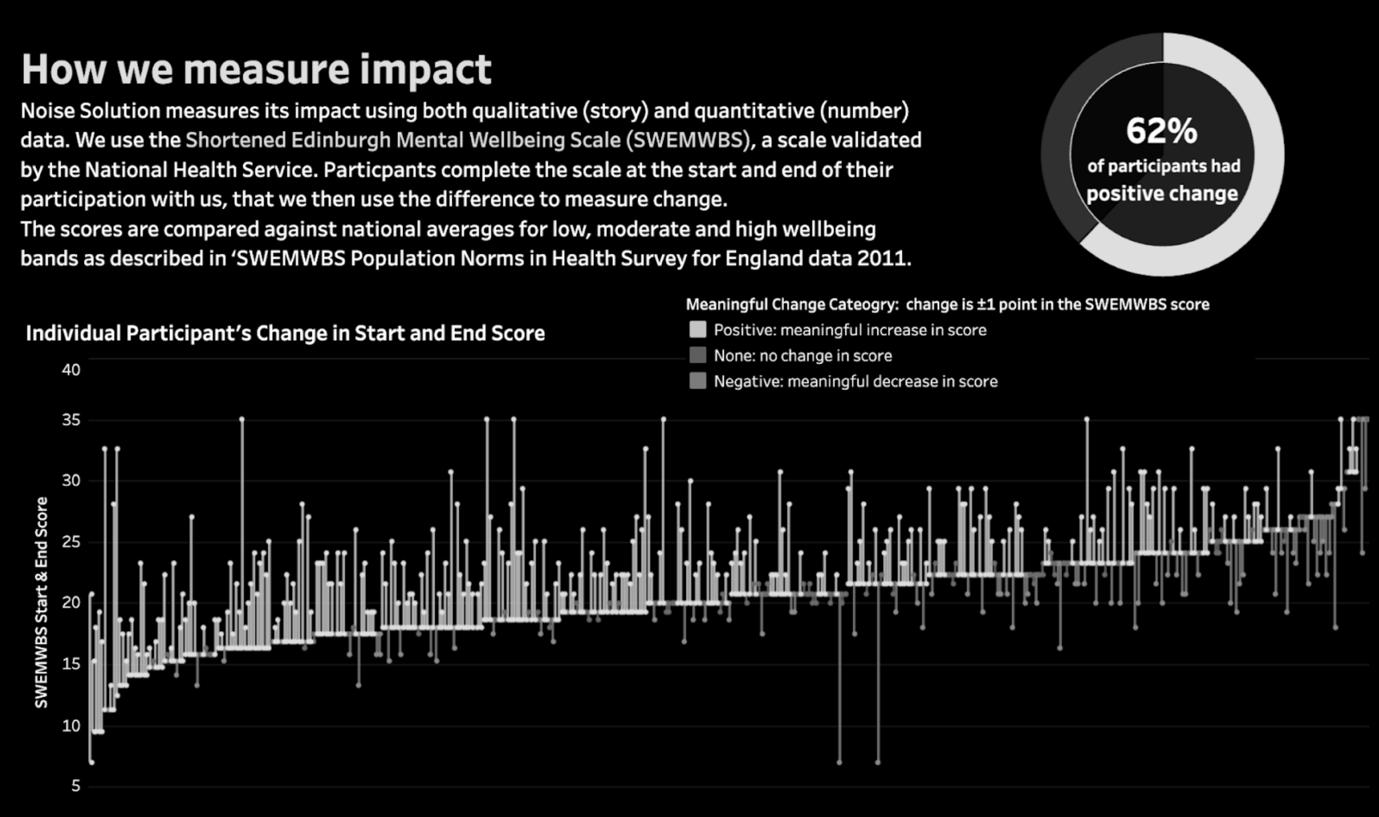

Figure 5 is a chart created in 2024 (updated from the sample when this chapter was originally written, showing changes in start and end SWEMWBS scores across the last 400 participants, demonstrating a highly positive trend of increased well-being over the population of

participants, whilst being transparent in showing that not all participants experience a wellbeing increase.

Significantly, the ability to benchmark these scores against 30,000 other responses holds intrinsic value. It steers us away from a common criticism of third sector organisations of arbitrarily made-up scales, and towards a more robust comparative framework. The use of technology and our data strategy means that all our outcomes’ data comes direct from participants themselves as they articulate their own subjective well-being in both number and word format, it is their unfiltered experiences and the outcomes that arise because of them.

This endeavour also shows flexibility to having access to different types of data. Specifically, we can scrutinise the well-being results of any group. For example, examining young women participants and inquiring into the statistical significance of their results. We can juxtapose those initial quantitative findings scores against national averages. The 'Story' component allows for the illumination of the authentic weekly voice associated with a data point or ‘person’ contributing data in the process. The integration of all this data, both qualitative and quantitative, within a singular cloud-based platform (there’s that data strategy again) means we can interrogate in any way we desire. This approach enables commissioners not only to observe numerical trends but also to directly engage with the unique narratives or ‘voice’ of each participant, thereby imbuing numbers with the often-compelling illumination of real-life outcomes.

The Financial Significance of Positive Well-being: For Families, For Services

In the preceding section, I briefly touched upon the financial implications of enhanced wellbeing. In 2024, a comprehensive pro-bono study was conducted by independent health economists and data analysts from a firm called Costello Medical, a large healthcare data consultancy. In simple terms, the study aimed to determine the financial value generated for every pound invested in the program, gauging how much money was saved by services, families, or systems. The report revealed that Noise Solution yielded a SROI of 1:12.56. That means for every £1 spent £12.56 is returned in savings to services and families (Costello Medical, 2024, p.3). Taking the amount of turnover Noise Solution received in commissioned services in 2024 this equates to a conservatively estimated saving of £6.46 Million. This is, as you can imagine, another strand to that breadth of data, contributing to a breadth of data to make the case.

What Lies Ahead: Exploring A.I Automated Audio-to-Text Linguistic and Sentiment Analysis for Video Evaluation

In a chapter dedicated to digital approaches for outcome capture and evaluation, it is essential to address digital advancements like A.I. This section serves as a glimpse into our next steps. It's important to note that everything discussed here is currently in beta form and hasn't been implemented live, yet. However, we've externally demonstrated the feasibility of the concepts discussed here. To the extent that in May 2024 we won the ‘Innovation in A.I.’ award at the national Digital Revolution Awards, winning a category that saw Noise Solution competing against Microsoft.

As stated previously, evaluation processes typically occur after a project concludes, as organisations compile data collected during the course of their interventions. Noise Solution is actively developing the capability to use generative AI to analyse what’s said conversationally in each of the reflective videos captured at the end of each session (if consent is given to do so). We can identify roles such as musician/participant in the transcript and ‘what is said when’, all of which can be time-stamped and added to a transcript. Importantly any identifying information can tokenized and removed, meaning that nothing identifying goes off to the AI service and after analysis we can link data back what’s been said to records but in a way that doesn’t leave identifying data open to the world. Once in text format, we can use generative A.I and our understanding of Self Determination Theory’s basic psychological needs to analyse that data. Advances in A.I when placed within a platform that already has a data strategy that collects story and number data in the same place could be a significant game changer.

We’ve demonstrated that the platform has the ability to securely collect and then perform linguistic analysis. Identifying within those reflection videos that contain conversational data the concepts related to Basic Psychological Needs (BPN). We’re able to return either what was said (descriptive data) or discrete values (numbers) attached to feelings changing over time within any video content i.e. return the top 20 things a person or demographic has said about any BPN. Or track over time how each of the BPN have changed week by week. Taking the next logical step, we could react to what that data tells us by surfacing advice to parents, professionals, or musicians on how to react to the absence of BPN within the reflections. We could highlight and react through targeted messaging where BPN are not being demonstrated, with the intention of further improving outcomes.

I should highlight that we fully acknowledge the substantial ethical considerations associated with collecting and analysing vast amounts of data on our platform. The strides made in A.I. technology, automatic speech-to-text, and their ability to conduct automated analysis of transcribed content present exciting possibilities, albeit with important ethical considerations. There are issues around where data is held, what’s done with it, bias within A.I language analysis to name a few.

However, the possibilities are also incredibly exciting. Charities in the UK spend an estimated fifteen and a half million hours a year reporting to funders and commissioners. As an organisation, we believe we can and are circumventing this problem through this approach of story and number data, collected in a way that harvests data on outcomes from conversations. It’s a world with better data, collected in a way that has outcomes itself and not a feedback form in sight!

Most evaluations reflect on the past, looking at what’s already happened. Evaluative processes by necessity have taken place after a project has finished. However, Noise Solution is moving ever closer to understanding what people are or are not saying of interest (within an SDT framework) as they move through a programme and being able to automatically demonstrate that visually within dashboards.

Conclusion

“There is no perfect way to capture changes in well-being” is something I find myself frequently saying when talking about Noise Solution’s approach to impact capture. This is often followed by me saying, “..anyone who says there is, is selling snake oil”. I think, as a

paired set of statements, these have greatly informed my approach to impact capture and analysis. They encapsulate both how hard the task is and how we need to be careful, indeed sceptical, about what and how we view ‘evidence’ of impact.

Development of the ways in which Noise Solution collects data happens, we hope, in a way that is non-intrusive to the experience of the young person and doesn’t interrupt the flow of sessions or the establishing of relationships. This approach is strengths-based, rather than deficit-based. It contributes to the outcomes it achieves; it also manages to bring disparate partners (so often siloed) in different sectors together around a strengths-based narrative (Education/Mental health/Local authority and families). All with the participant feeling in control. SDT theorises that any perceived lack of autonomy is a demotivator. Acting in any way that medicalises or problematises young people means they can feel controlled and this, through an SDT lens, is often an endemic issue with data collection and should be considered problematic and guarded against.

This has so often been a stumbling block for organisations demonstrating outcomes, as many feedback mechanisms used to capture impact do just ‘get in the way’ and can feel controlling. For example, when was the last time someone felt good about being asked to fill in a feedback form? No one feels intrinsically motivated to do that. Especially if it was giving you a scale essentially asking how broken you are? Intentionally, as far as any Noise Solution participant is concerned all they are doing (apart from answering seven brief positively framed well-being questions (SWEMWBS) in week one and week ten, is making or talking about making music and posting about it, in a way that mirrors very common social media experiences. Yet the breadth of data and what we can extrapolate from both the qualitative and quantitative data,

within a digital infrastructure where everything from referral forms/engagement of family and professionals within the platform/who said what when all collected in one data ‘bucket of truth’ is truly deep.

Simply, we enable young people to take control of an element of their lives (Autonomy), often against a backdrop of things not going so well. We then support them to be good at something they care about, their music, and we do so quickly (Competence). Technology allows us to mirror their success back at the young person. That same technology enables their significant adults to also experience or ‘see’ and engage in that success. Vitally, for the participant, that facilitates them ‘feeling seen’ as successful by those whose opinion they value (Relatedness). We believe that capturing and sharing weekly reflections contributes to far wider outcomes. As an approach, it incorporates the collection of data as an integral part of the culture, and it doesn’t get in the way.

Data is king, yet organisations often seem averse or incapable of either collecting it or understanding what to do with it once they have it. Scattergun approaches to data collection can mean that organisations miss the fantastic opportunities that having a focused data strategy offers. Consistent data collection (collected intentionally in a way useful to the organisation) can solve many issues based on funders' demands or claims of impact for your work. The opportunities that technology gives us to remove the barriers to collecting meaningful data, mean that the information we do collect can be seen as far more powerfulliterally in the case of video. If we utilise technology to listen to and understand that video data automatically - rather than wading through it - as I’ve shown, whole new worlds of possibilities in outcomes analysis open.

My ‘takeaway’ is that organisations are missing a trick if impact data is left as an afterthought or merely added on through someone else’s agenda. Data collection is a powerful tool, solving myriad problems in making organisations work better to achieve greater outcomes for those they work with. Evaluation should not be ‘bolted on’ the end of projects. It needs to be folded into the very DNA of how an organisation engages with people and its technology and yet needs to be subtle enough not get in the way of the frontline work being done. Evaluation also needs to have breadth, and depth, which can sound quite daunting, but this a message to help encourage others to think more deeply about their impact capture journey. If in doubt follow the advice I followed when I started 15 years ago that’s led me to this point “If you are not sure where to start, just start collecting something.”

References

Costello Medical (2024). Social Return On Investment Report Available: https://issuu.com/noisesolutionuk/docs/sroi_model_exec_summary_and_methodology_april2 024?fr=sYjBlZjcyNzYxNTc Last accessed 30/5/2024

Davis, A., & Weinshenker, D. (2012) Digital Storytelling and Authoring Identity In: C. Ching, & B. Foley (eds.), Constructing the Self in a Digital World. Cambridge University.

Deane, K., Holford, A., Hunter, R., & Mullen, P. (2015). Power of equality 2. Available: http://network.youthmusic.org.uk/learning/research/power-equality-2-final-evaluation-youthmusics-musical-inclusion-programme-2012-20. Last accessed 18/1/2022.

DeNora, T., &Andsell, G. (2014). What Can’t Music Do. Psychology of Well-Being Theory. Press 47-74.Research and Practice, 23 (4), 1-10.

Department of Health and Social Care (2019). Strengths-based approach: Practice Framework and Practice Handbook. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data /file/7781 Last accessed 10/09/2022.

Fancourt, D. Warran, K. Aughterson, H. (2020). Evidence Summary for Policy The role of arts in improving health & well-being Report to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evidence-summary-forpolicy-the-role-of-arts-in-improving-health-and-wellbeing. Last accessed October 2022.

Glenister, S. (2018) Changes in well-being of youth in challenging circumstances: Evaluation after a 10-week intervention combining music mentoring and digital storytelling. Transform 1 (1), 59-80.

Gutman, L., & Vorhaus, J. (2012). The Impact of Pupil Behaviour and Well-being on Educational Outcomes. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data /file/219638/DFE-RR253.pdf Last accessed 10/10/2022.

Howell, R., Kern, M.L., & Lyubomirsky,S. (2007) Health benefits: Meta-analytically determining the impact of well-being on objective health outcomes. Health Psychology Review, 1 (1), 83-136.

Kegan, R. (1994) In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. Harvard University Press.

Lifestyles Team, NHS Digital (2021). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2020: Wave 1 follow up to the 2017 survey. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/dataand-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-inengland/2020-wave-1-follow-up# Last accessed 1/9/2022.

Nagpaul, T. Chen, J. (2019). Self-determination theory as a framework for understanding needs of youth at-risk: Perspectives of social service professionals. Children and Youth Services Review 99 (1), pp. 328-342.

Ng Fat, L., Scholes, S., Boniface, S. et al. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental well-being using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual Life Res 26, 1129–1144 (2017).

Noise Solution (2021). Impact report. Available: https://issuu.com/noisesolutionuk/docs/ns_impact_report_2021_ Last accessed 18/1/2022.

Best Psychology Scientists (2022). Research.com. https://research.com/scientistsrankings/psychology. Last accessed 2/11/2022.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000) Self Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation. Social Development, and Well-Being American Psychologist, 55 (1), 68-78.

Shah, N. Cader, M. Andrews, B. McCabe, R. Stewart-Brown, S. (2021) Short WarwickEdinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): performance in a clinical sample in relation to PHQ-9 and GAD. Health Qual Life Outcomes 19 (260).

Shah, N. Cader, M. Andrews, W. P. Wijesekera, D. & Stewart-Brown, S. L. (2018). Responsiveness of the Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS): Evaluation a clinical sample. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16.

Social Enterprise Mark (2020). What is Social Enterprise? Social Enterprise Mark. Available:https://www.socialenterprisemark.org.uk/what-is-social-enterprise/#toggle-id-5. Last accessed 31/7/2022.

The Social Investment Consultancy (2016). Noise Solution External Evaluation Report. Available: Youth Music https://network.youthmusic.org.uk/posts/cabinet-office-fundedimpact-audit-states-noise-solution-sta. Last accessed 31/7/2022.

Will Thompson. (2023). Charities spend 15.8 million hours reporting to funders - that's too much. [Online]. Time to Spare. Last Updated: August 2023. Available at: https://blog.timetospare.com/charities-spend-15-8-million-hours-reporting-to-funders-that-stoo-much [Accessed 23 August 2023].

Van den Broeck, A. Ferris, D. Chang, H. Rosen, C. (2016). A Review of Self-Determination Theory’s Basic Psychological Needs at Work. Journal of Management 42(5), pp. 11951229.

Warwick Medical School (2021). Collect, score, analyse and interpret (S)WEMWBS. Available: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/platform/wemwbs/using/howto. Last accessed 10/11/2022