&CONTEMPORARY MODERN

ART + DESIGN

04.18.24

he Modern & Contemporary Art + Design Auction offers a curated selection of items as wide-ranging as an innovative silkscreen by Christopher Wool, the powerful documentary photographs of Gordon Parks, works by Southern Regional artists Ida Kohlmeyer and George Dunbar, the iconic jazz images of Jean-Pierre Leloir and William Gottlieb, the vibrant and colorful abstract works on paper by some of the most significant Spanish artists of the 20th century, to eclectic lighting and iconic mid-century furniture.

“Untitled”

T

Ida Rittenberg Kohlmeyer (American/Louisiana, 1912-1997)

oil on canvas, 47” x 58�”

“The ideas I work with are essentially timeless … Working with basic ideas will always be exciting, and if a color or form is visually exciting in any profound sense, it will be that way in 10 or 20 years from now.”

-Richard Anuszkiewicz, 1977

George Dayez (French, 1907- 1991)

“Femme Se Coiffant”, 1955/6 oil on canvas, 32” x 38”

George Dayez (French, 1907- 1991)

“Femme Se Coiffant”, 1955/6 oil on canvas, 32” x 38”

Modernica

Los Angeles Daybed

20th century, h. 26”, w. 74-1/2”, d. 34-1/2”

Francisque

“Sans Titre”, 1954 carved limestone, h. 31-1/2”, w. 13”, d. 9”

Lapandery (French, 1910-1961)

“Untitled”

oil on paper mounted on wood panel, 17-1/2” x 14-1/2”

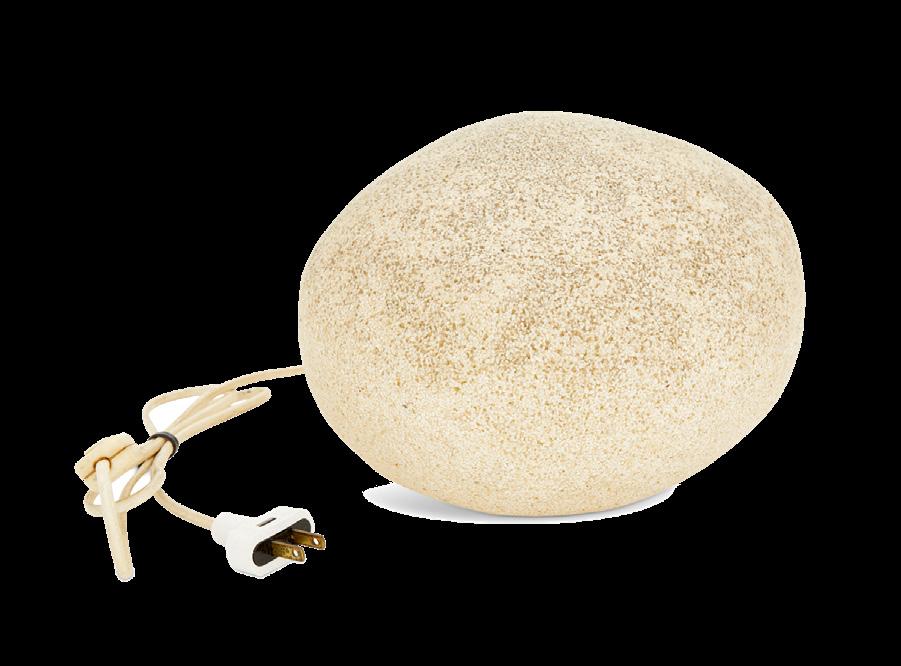

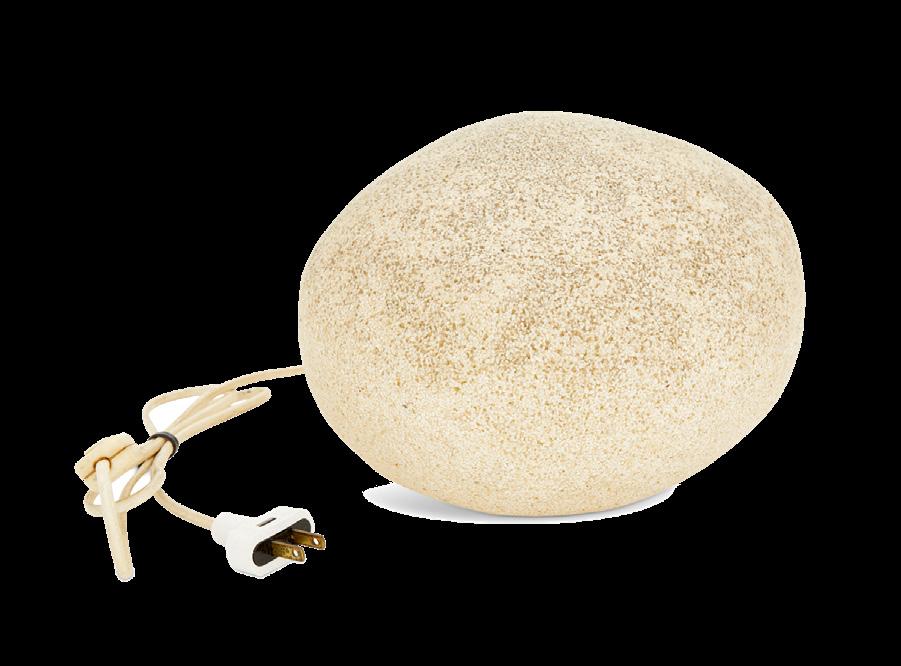

“Rock” Table Lamp for Atelier A

1970s,

Andre Cazenave

France, h. 6-3/4”, w. 9, d. 9”

Clyde Connell (American/Louisiana, 1901-1998)

THAT’S WHERE IT STARTS AND THAT’S WHERE IT ENDS.

MAXWELL HAGEGE

Vamdrup Stolefabrik

Dining Table and Four Chairs

1960s,Brazilian rosewood table h. 28-1/4”, dia. 48”, with leaves l. 72”; chairs h. 34”, w. 20”, d. 22-1/2”

LOGAN

Tripod

“In a Boat Under the Stars” pen and ink on paper, 18”

Frank

“Sugar Baby Melon”

gilt-painted bisque, h. 8”, w. 10-1/2”, d. 8”

Walter Inglis Anderson (American/Mississippi, 1903-1965)

x 15-1/2”

Fleming

(American, 1940-2018)

T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings

Table Lamp ca. 1950, brass, h. 21-1/4”, dia. 17”

William “Bill” Ludwig (American, Louisiana, 1935-2011)

“Untitled”, 1986

polished and patinated bronze, h. 25”, w. 7-3/4”, d. 5”

Contemporary Side Table

glass and patinated metal

h. 25-1/4”, w. 18-3/4”, d. 18-3/4”

Contemporary Linen

Velvet Sofa h. 32”, w. 82, d. 36”

Eduardo Chillida (Spanish, 1924-2002)

“Chicago”

lithograph on Rives paper, 41-1/8” x 29”

Eduardo Chillida (Spanish, 1924-2002)

“Chicago”

lithograph on Rives paper, 41-1/8” x 29”

use silkscreen like a brush. It’s just something between my hand and the painting. I do the screening myself and it seems like a very mechanical process ... To me, [silkscreen] is one of those kinds of processes that you can see, like a dripping in the painting, you can see it, you can feel that it is handmade. You know that it is not completely mechanical, it’s printed like a professional printer. I think that gives the audience an entrance into the painting. I think visual art has power, that’s the interest to me, and that should communicate to the audience. It’s not a specific message.”

- Christopher Wool in conversation with Nicolas Trembley for Numéro

- Christopher Wool in conversation with Nicolas Trembley for Numéro

I “

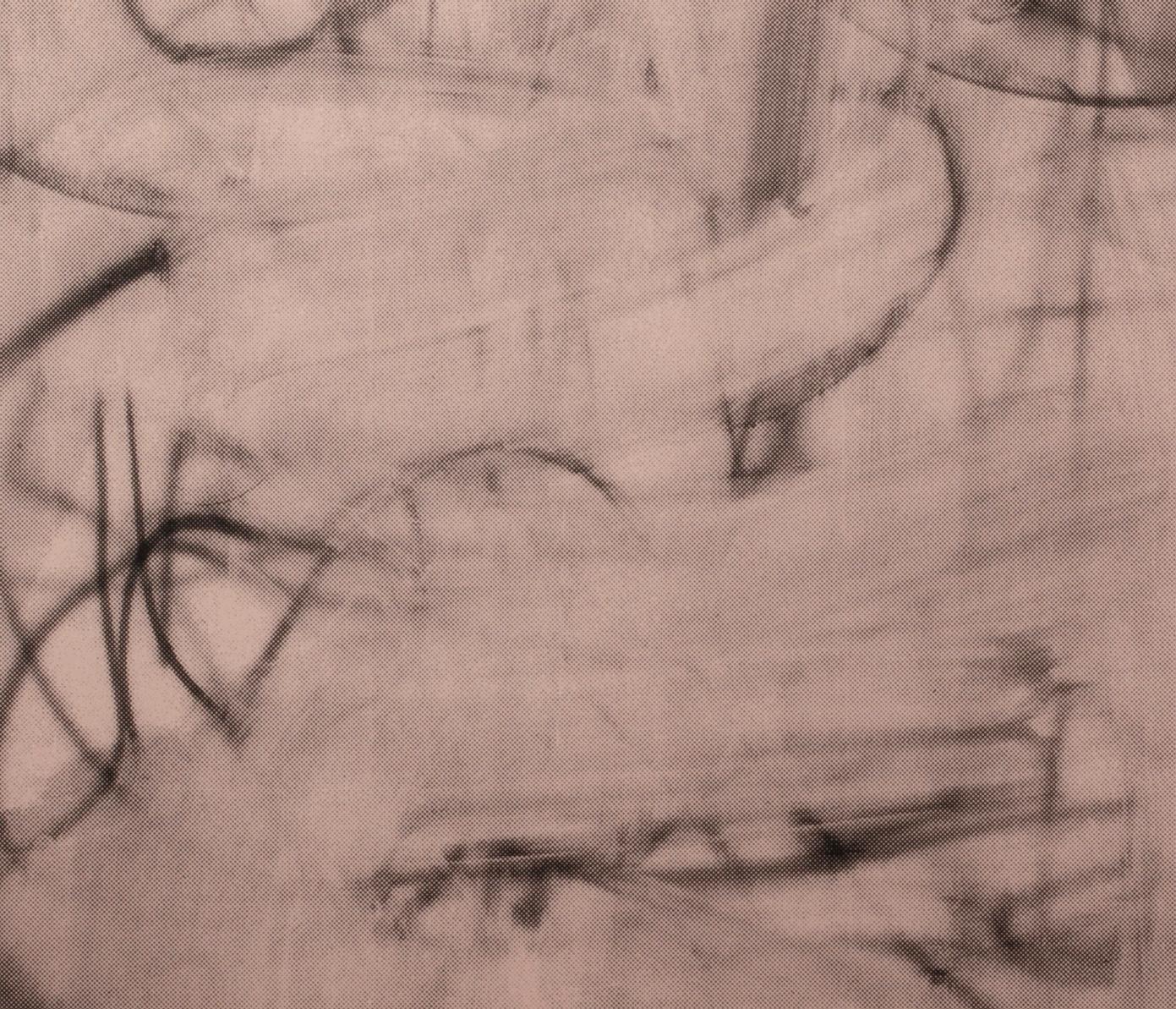

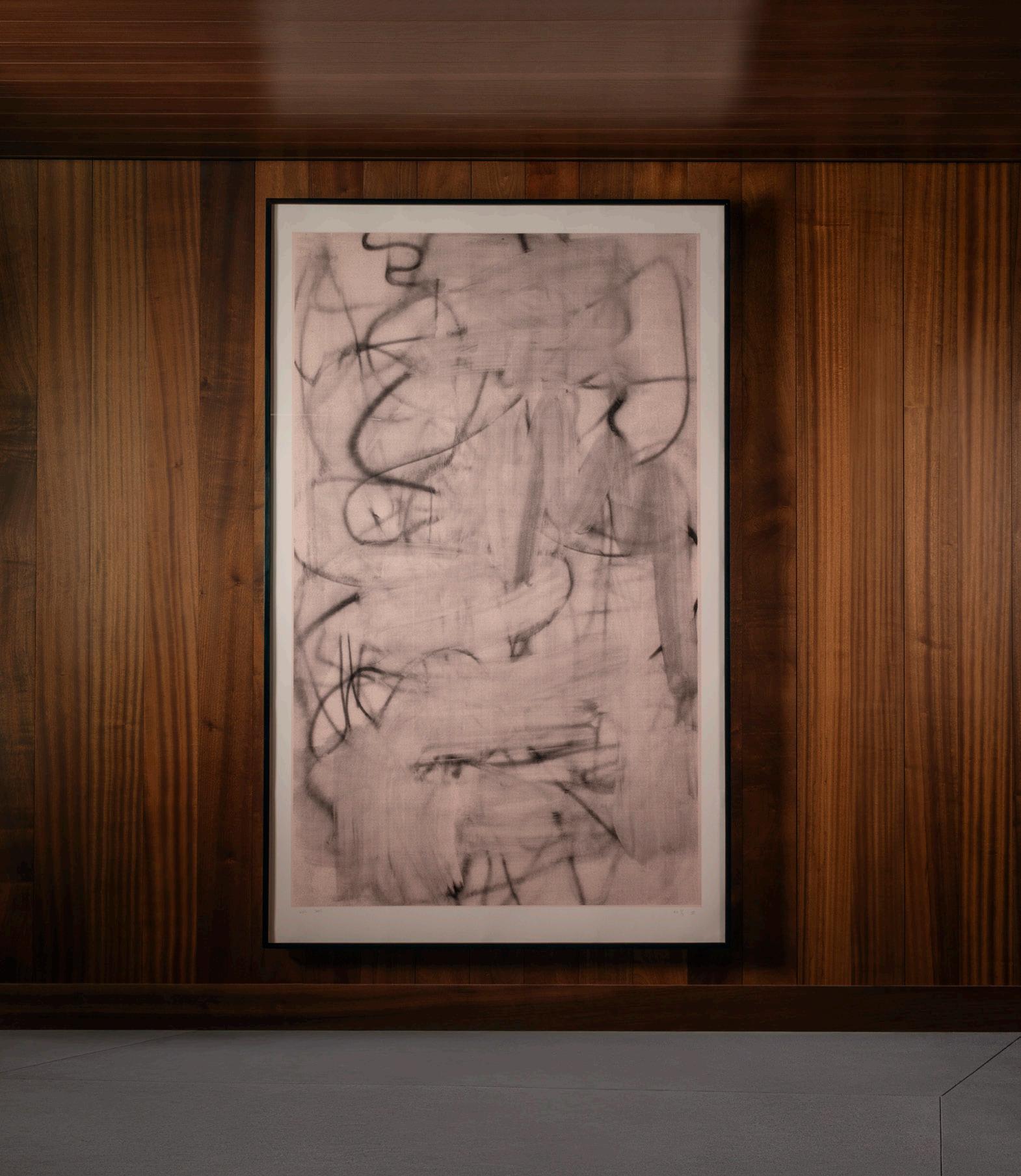

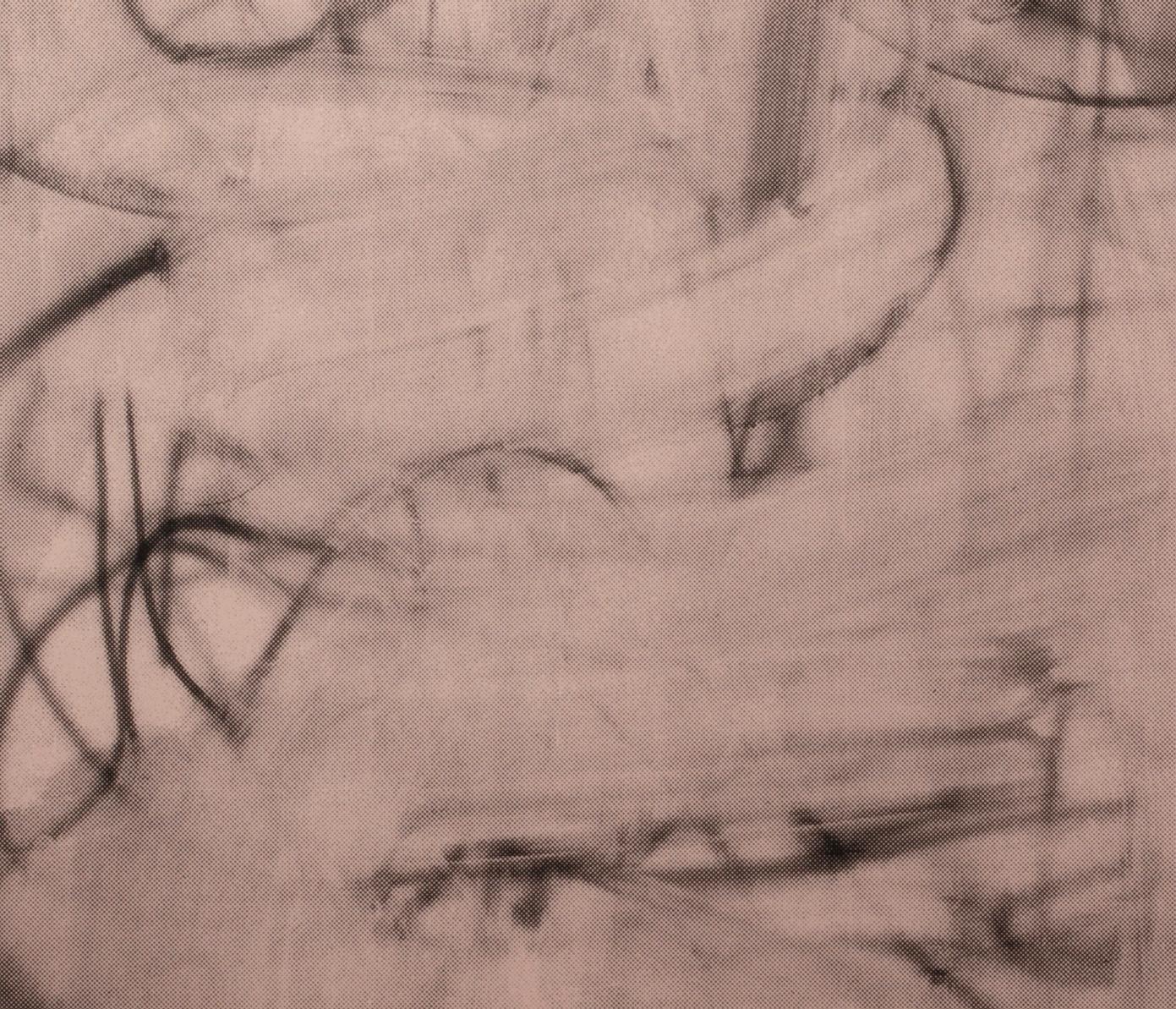

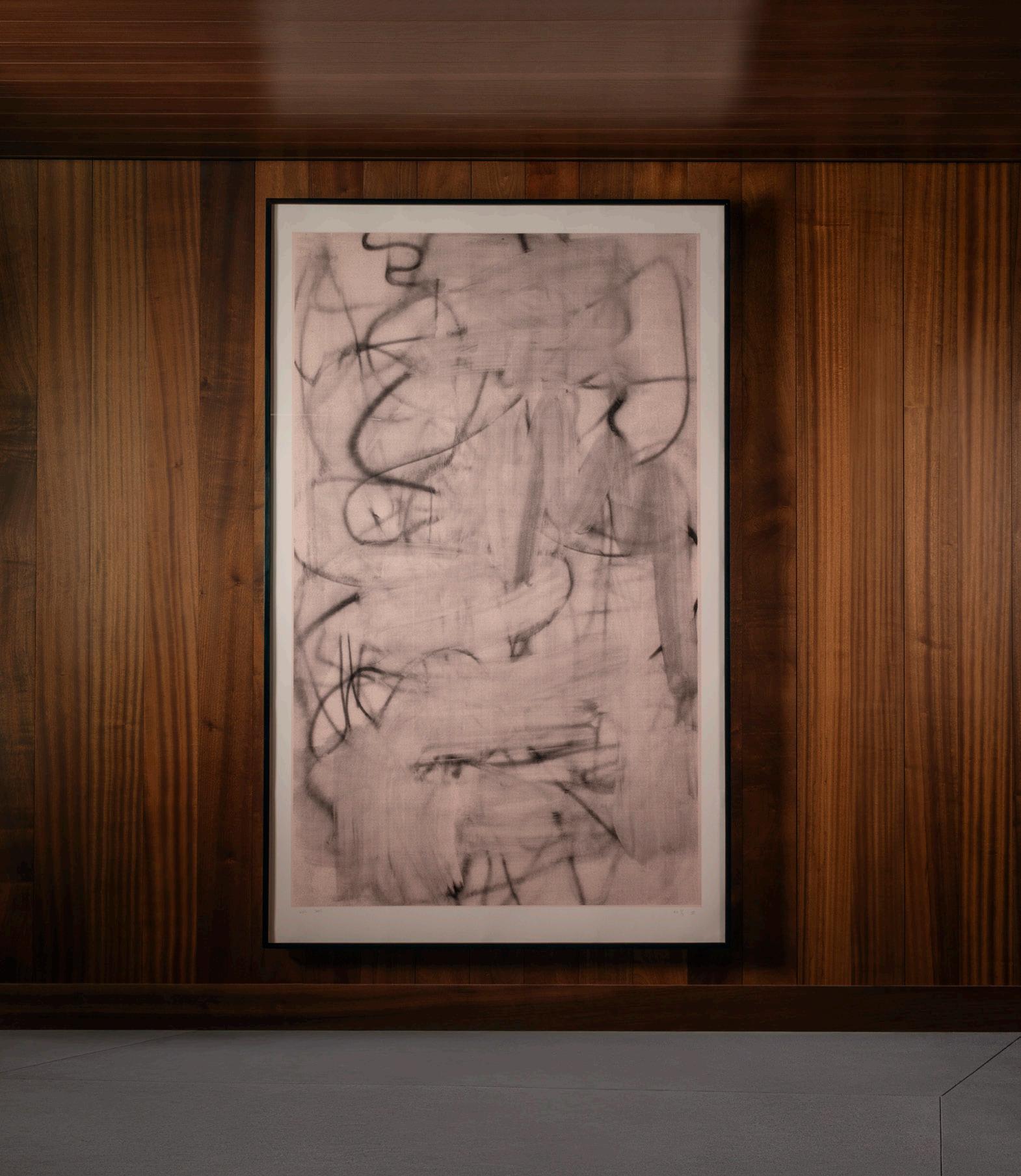

Christopher Wool (American, b. 1955)

“Woman III”, 2005 silkscreen ink on paper, 82-1/2” x 51-1/2”

O CHRISTOPHER WOOL

ffering both abstract fluency and access to the mechanics of expression, Woman III (2005) exemplifies why Wool’s work resists codification so deftly. Born to a molecular biologist and a psychiatrist in 1955, Wool rose to prominence in New York in the 1980s by approaching painting differently from the popular Pictures Generation artists who repudiated the validity of painting in a postwar setting. It was within these parameters that Wool began his artistic practice of creating distance between himself and his work by using rollers, stamps, and stencils to create readymade compositions of universal words and phrases in black enamel paint on sharply white canvas and aluminum surfaces. By highlighting process and using an objet trouvé approach, Wool was able to evade the notion of painterly expression. Through this approach however, he was also able to maintain a free-hand fluidity by leaving in the uneven textures of rollers, the pooling at the sides of the rubber stamp, and the irregular drippings from the stencils.

Following this early work, Wool began to dabble with silkscreen. This method afforded him more control over the mechanical process of creation, while still allowing for naturally occurring flaws that had become recognizable to his oeuvre. The dense layers applied via silkscreen created new forms and configurations, and Wool’s work with abstraction expanded beyond that of his black-and-white paintings through the implication of natural forces in conjunction with mechanics of expression. These automated works broadened Wool’s oeuvre as he began to reconsider his embargo on mark making by tracing, and then erasing, layers of gestural lines reminiscent of graffiti.

The hand of the artist came more into focus, and this is evident in Woman III, with its delicate, arabesque loops and the freehand wiping and smearing that break up those loops. Woman III is one of a monumental triptych that pays homage to a series of work by Willem de Kooning from 1964 to 1966, featuring several imposing, behemoth female figures on wooden doors that had been installed in his studio at one time. The resulting works are considered a touchstone in de Kooning’s career. Wool’s triptych was influenced by de Kooning’s works and is a reflection on the use of medium, especially the importance

“Woman III is one of a monumental triptych that pays homage to a series of work by Willem de Kooning...”

of silkscreen to Wool’s practice. The abstraction in Woman III, borne of a symbiotic cycle of doing and undoing, coalesces into emotive and conceptual cohesion, not unlike de Kooning’s abstraction. The synthesis of adding hand-painted lines, their subsequent obfuscation, and the strata of images via automated silkscreen mark a return to those formal qualities that are associated with painting. Like in Wool’s most sought-after paintings, Woman III is a tense and arresting investigation of creation and erasure, gesture and mechanics, that renews painting and immortalizes silkscreen as valid post-modern processes.

Reference: Nicolas Trembley, “Meet artist Christopher Wool, the master who creates tension between painting and erasing, gesture and removal”, Numéro, November 3, 2022.

Curtis Jere “Skyscraper” Table Lamp

1970s, chrome, h. 37-1/2”, w. 17-1/2”, d. 17-1/2”

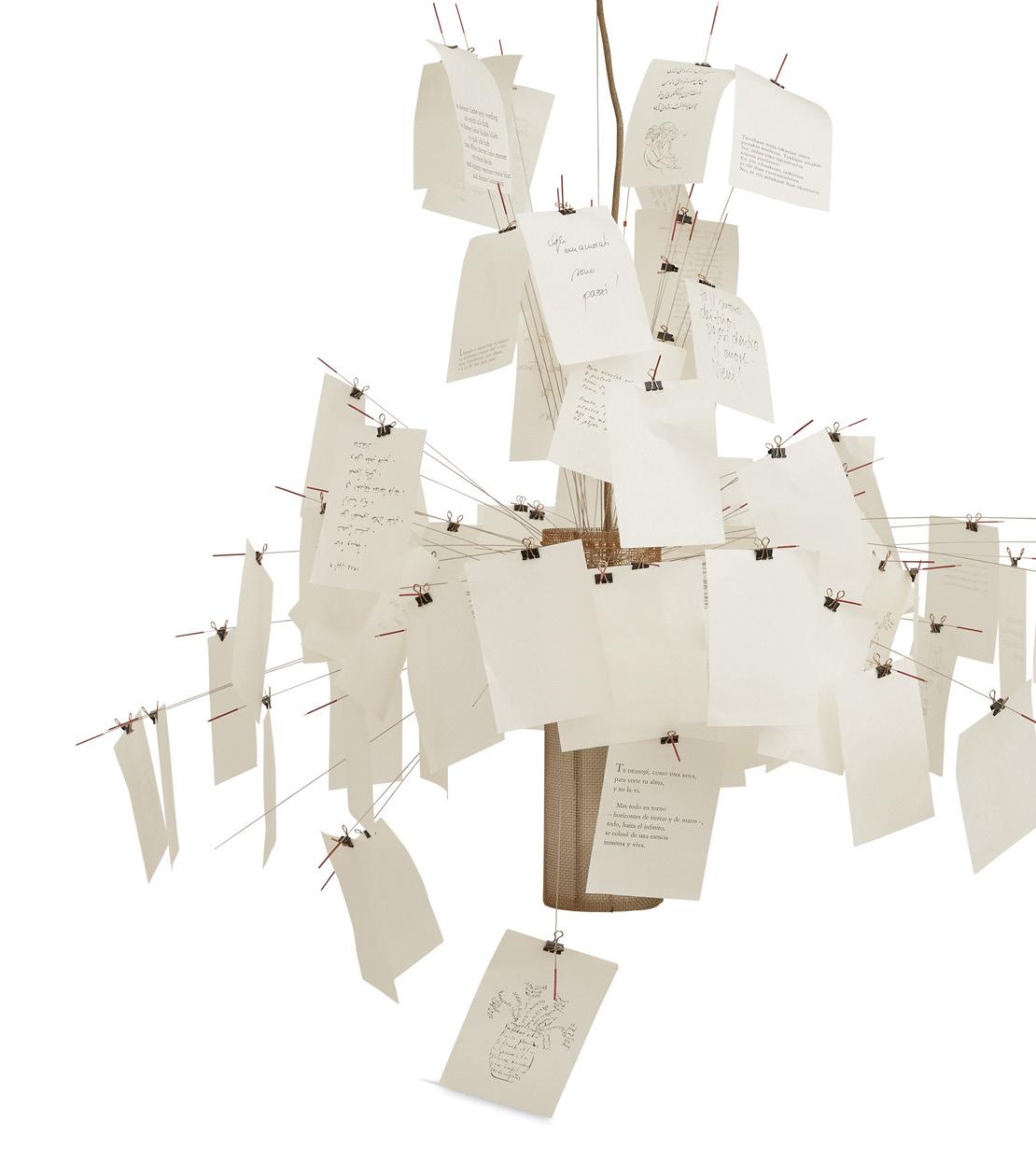

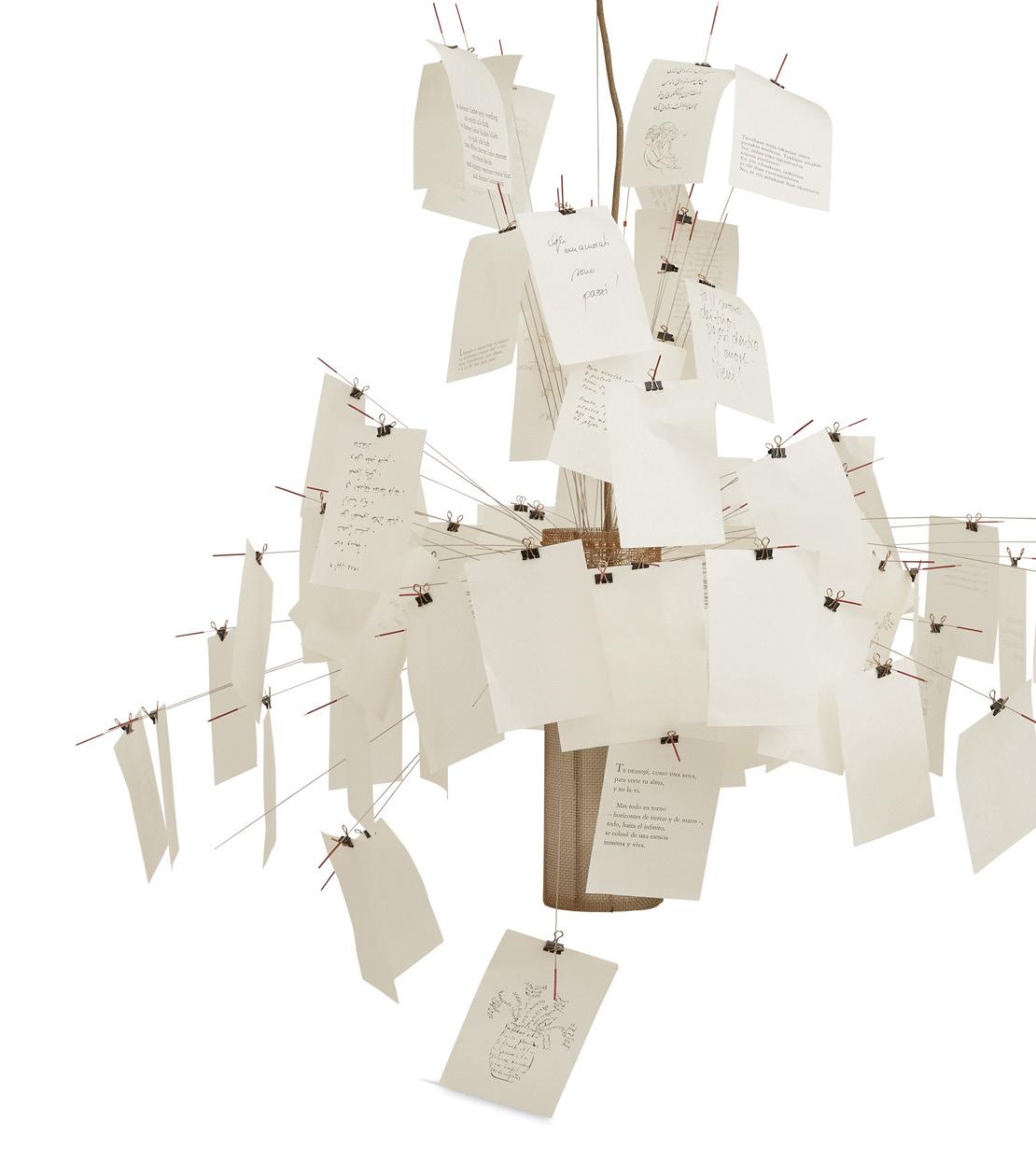

Ingo Maurer “Zettel’z 5” Pendant Light Fixture

1997, Germany

stainless steel, frosted glass, and Japanese paper, dia. 40-42” (variable)

Curtis Jere “Skyscraper” Table Lamp

1970s, chrome, h. 37-1/2”, w. 17-1/2”, d. 17-1/2”

Ingo Maurer “Zettel’z 5” Pendant Light Fixture

1997, Germany

stainless steel, frosted glass, and Japanese paper, dia. 40-42” (variable)

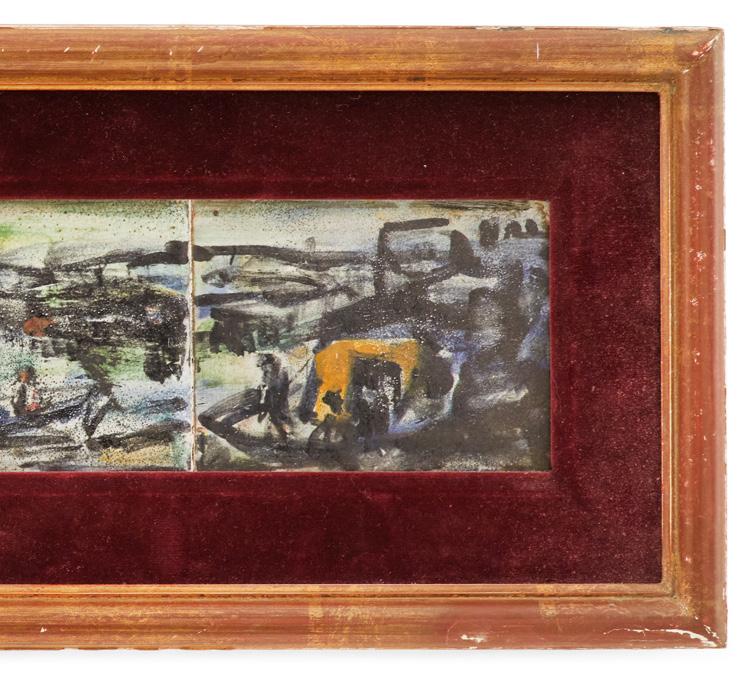

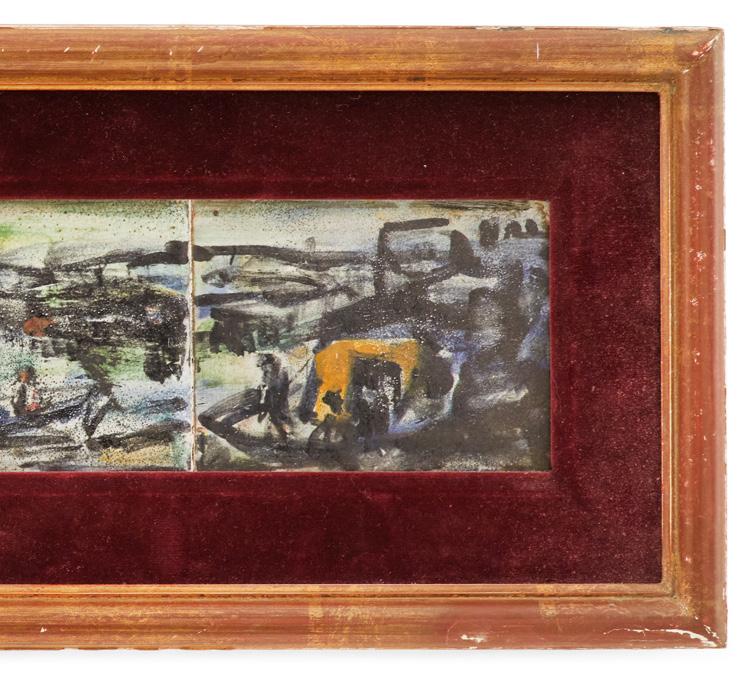

Georges Rouault (French, 1871-1958)

“Le Port,” painted and glazed ceramic, 7-7/8” x 18”

Georges Rouault (French, 1871-1958)

“Le Port,” painted and glazed ceramic, 7-7/8” x 18”

French Art Deco Coffee and Tea Service

first quarter 20th century, silverplate

French Art Deco-Style Credenza

mid-20th century, rosewood and marble, h. 39-1/2”, w. 68”, d. 21”

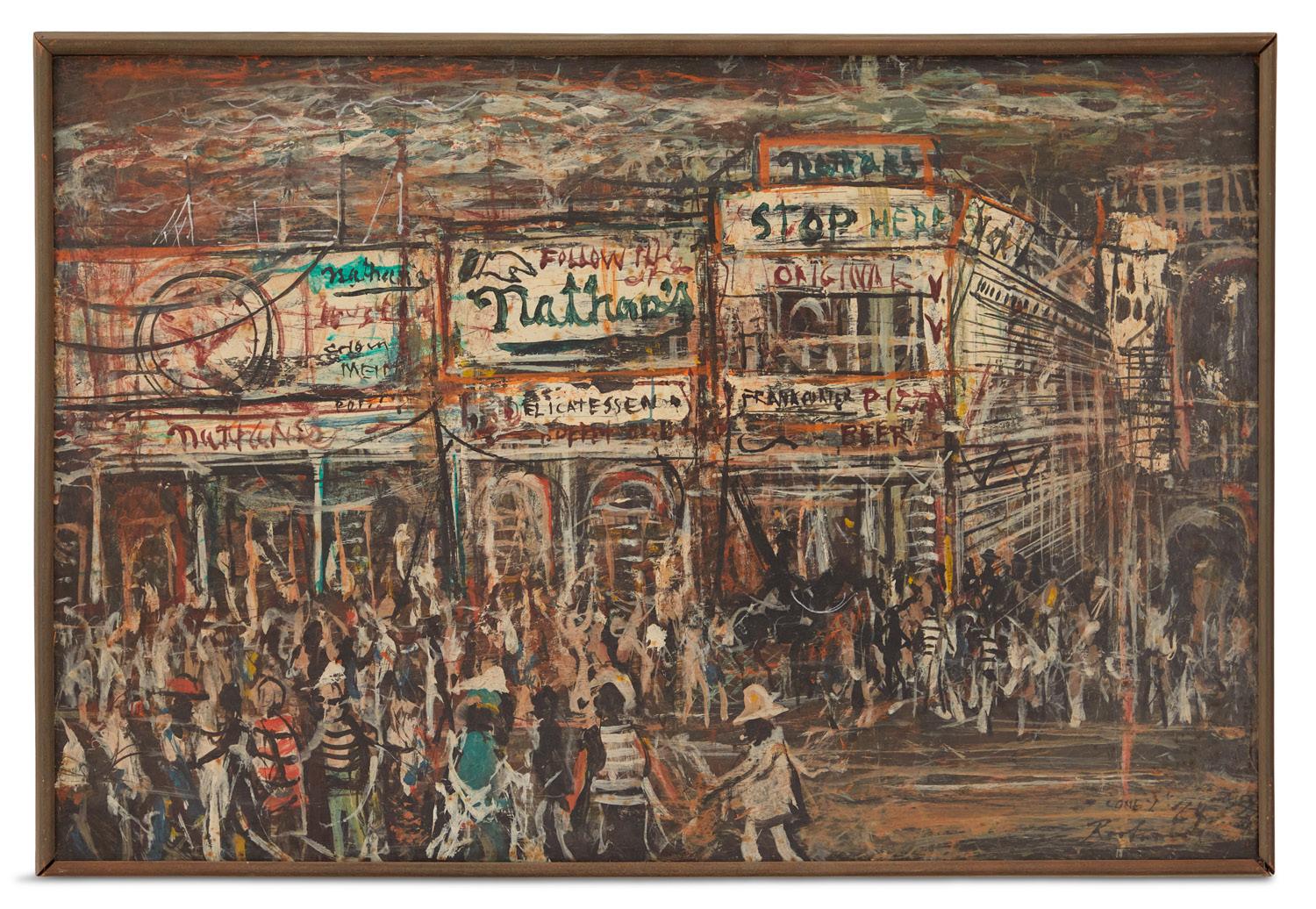

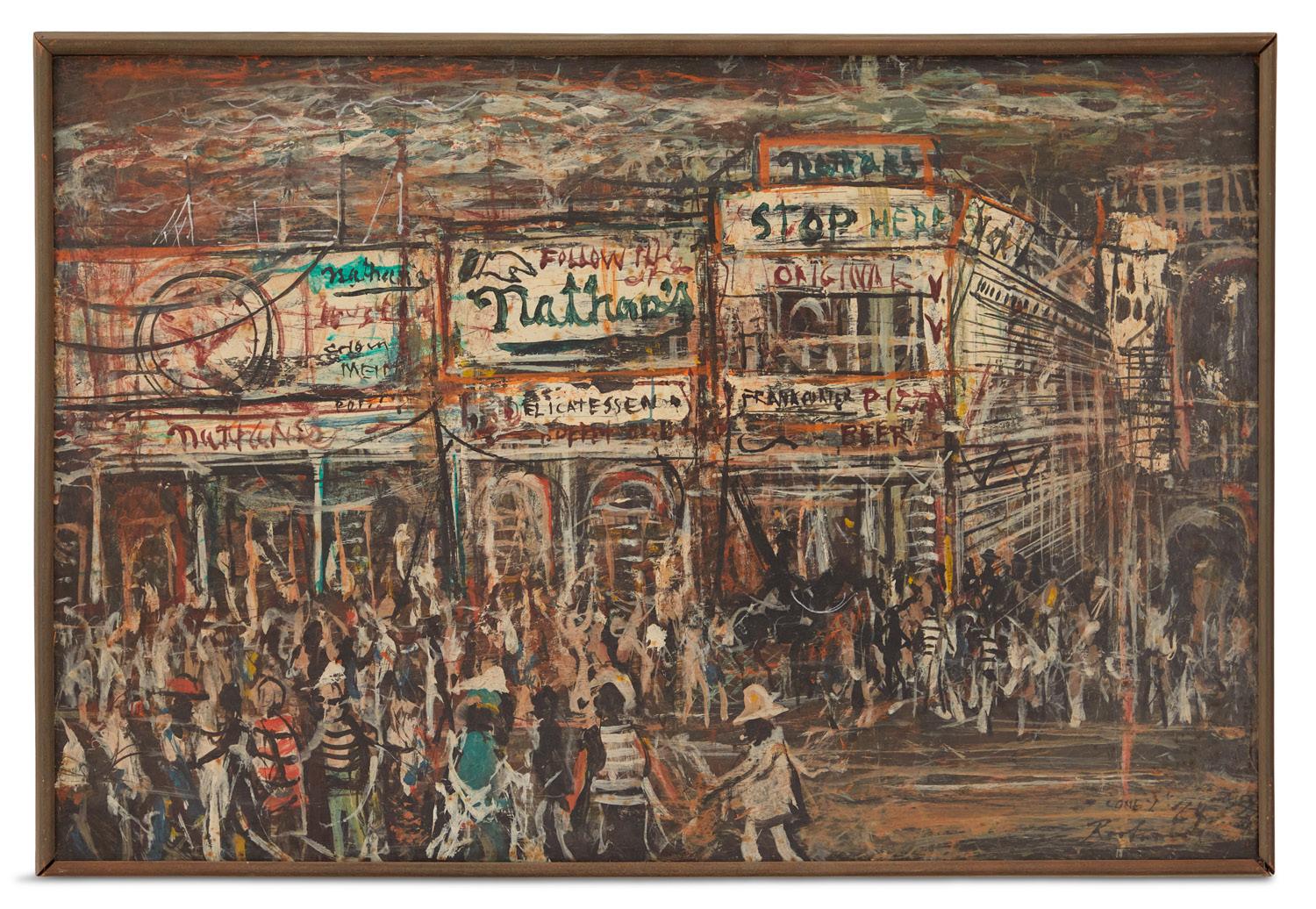

Noel Rockmore (American/Louisiana, 1928-1995)

“Coney Island: Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs”, 1964, oil on masonite, 25” x 37”

Mario Villa

(Nicaraguan/Louisiana, 1953-2021)

Mixed Metal Floor Lamp, h. 78-3/4”, dia. 25”

Noel Rockmore (American/Louisiana, 1928-1995)

“Coney Island: Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs”, 1964, oil on masonite, 25” x 37”

Mario Villa

(Nicaraguan/Louisiana, 1953-2021)

Mixed Metal Floor Lamp, h. 78-3/4”, dia. 25”

Roger Rougier Table Lamp

1970s, acrylic h. 28-1/2”, w. 7-1/2”, d. 11-1/4”

Maurizia Tempestini for Salterini Coffee Table

plate glass and iron, h. 18”, w. 54”, d. 30”

Frank Gehry Style

“Wiggle” Lounge Chairs (one of a pair)

1970s, pencil reed h. 34-1/2”, w. 18-1/4”, d. 27-1/2”

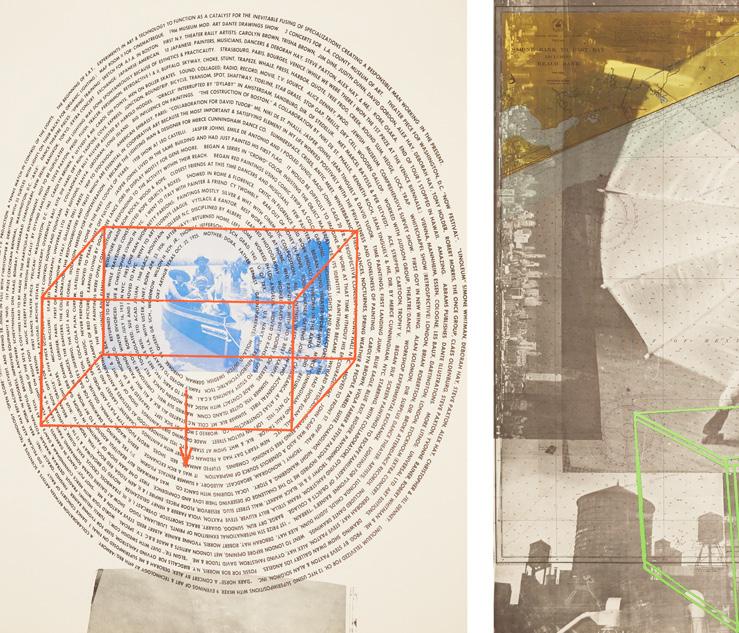

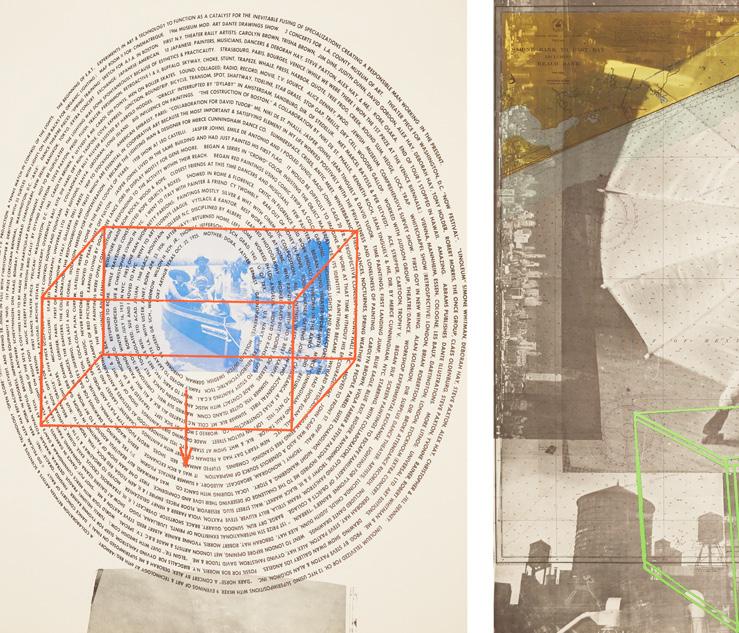

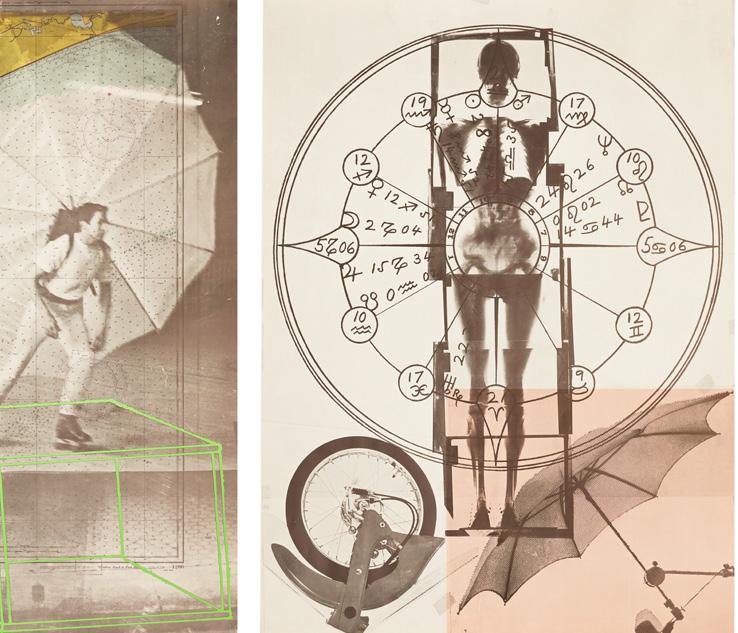

Robert Rauschenberg (American, 1925-2008)

“Autobiography”, 1968, three-panel offset lithographs, each 66-1/2” x 48-3/4”

Arthur Silverman (American, 1923-2018)

“Untitled”, 2000, patinated steel, h. 15-3/4”, w. 13”, d. 8”

Custom Modern Coffee Table bronze-patinated steel base, h. 18-1/2”, w. 48”, d. 48”

Brass and Lucite Table Lamp

1970s, France h. 12”, w. 16-1/4”, d. 5-3/4”

Jack Haywood for Modeline

“Serpentine” Floor Lamp

enameled wood h. 58”, w. 9-1/2”, d. 14”

Poul Henningsen for Louis Poulsen

“PH 4/3” Table Lamp

chrome-plated brass and steel, spun aluminum and bakelite h. 21-1/2”, dia. 17-3/4”

Pierre Cardin

Ralph Lauren Silvered Bronze and Burkina Stone-Top Gueridon silvered bronze, stone h. 30”, dia. 29”

Ralph Lauren Silvered Bronze and Burkina Stone-Top Gueridon silvered bronze, stone h. 30”, dia. 29”

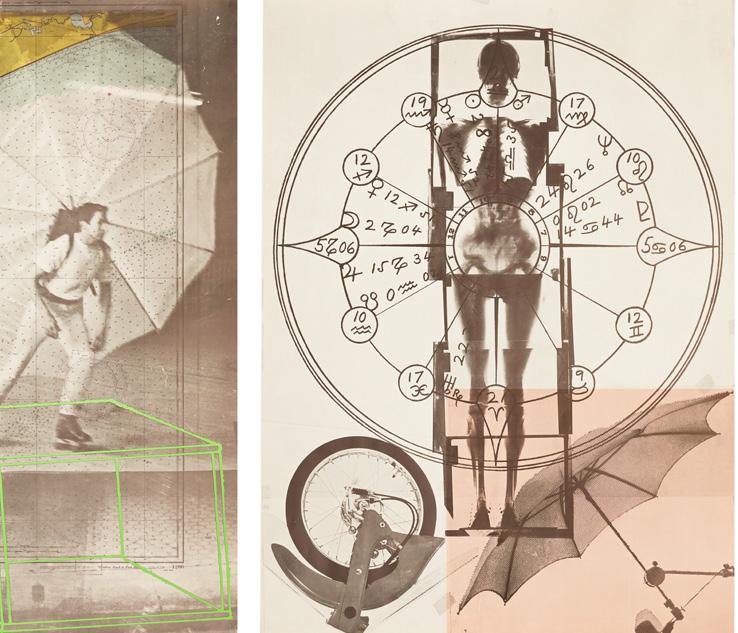

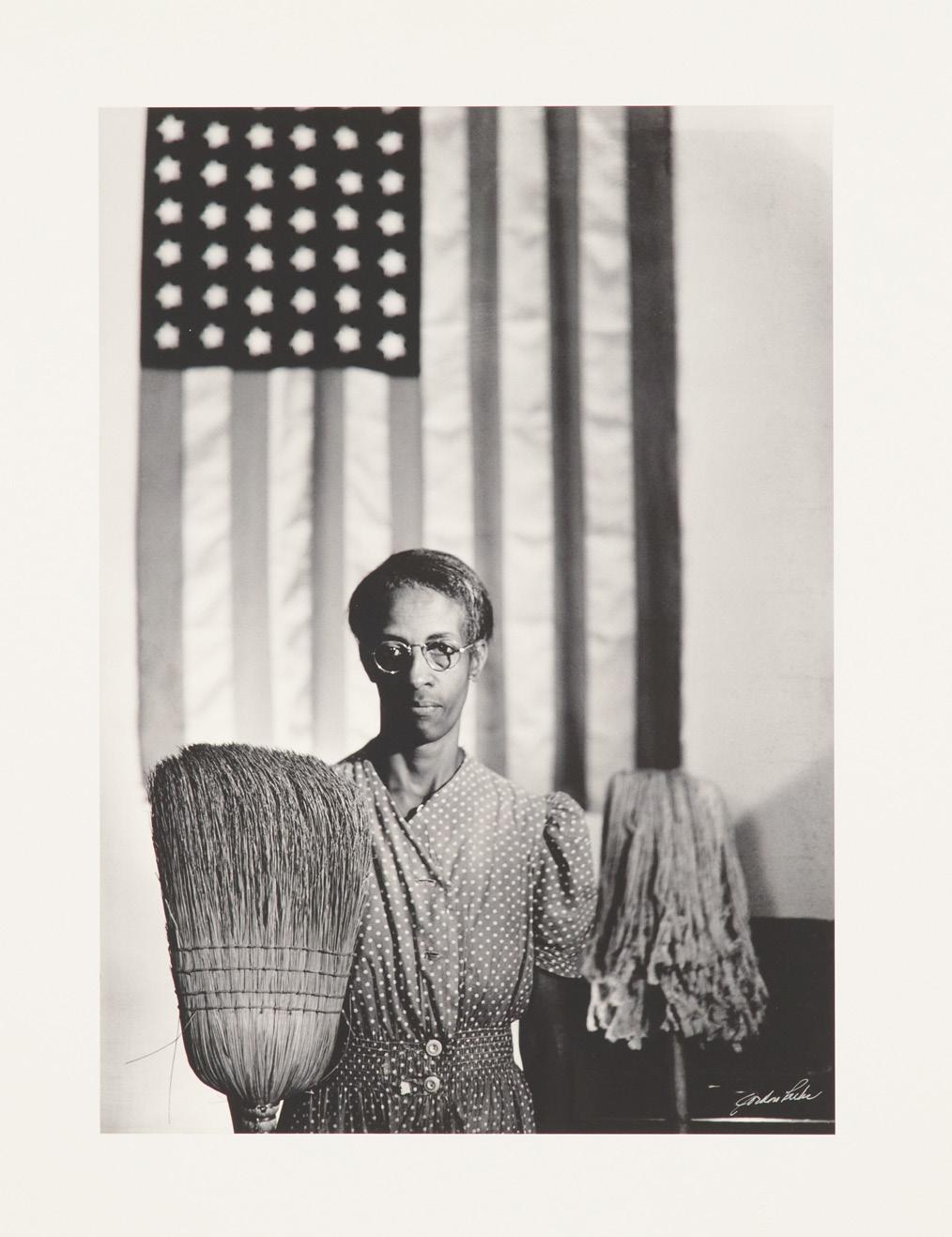

GORDON PARKS

(AMERICAN, 1912-2006)

One of Gordon Park’s most well-known and lauded images, “American Gothic” was a direct result of the rampant racism of 1940s Washington D.C. In 1942, the young photographer was awarded a Rosenwald Fellowship which afforded him the opportunity to apprentice at the Farm Security Administration (FSA) photography program. Re-locating from Chicago to D.C., Parks experienced an appalling degree of racism that astonished even him. Discovering no one even willing to talk with him, much less allowing him to take photographs, the young man resolved to look within the local African American community.

“American

Gothic, Washington, D.C. (Ellen Watson)”, 2021 archival pigment print from the 1942 negative, 22” x 17”

I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point I had to have a camera.”

- Gordon Parks

He began a conversation with one of the office’s cleaning ladies, Ella Watson, who eventually agreed to allow him access to herself and her neighborhood. Over the course of weeks, Parks followed Watson to her home, church, and work, documenting various aspects of African American life in the region. The culmination was a powerful series, a strong indictment of the position and plight of the African American in 1940s society. By posing Watson against an American flag, mop in one hand and broom in the other, looking directly into the camera, Parks simultaneously references and re-interprets the iconic Grant Woods painting of the same name. “

David Parks (American, b. 1944)

“Portrait of Gordon Parks”, 2021 archival pigment print, 22” x 17”

David Parks (American, b. 1944)

“Portrait of Gordon Parks”, 2021 archival pigment print, 22” x 17”

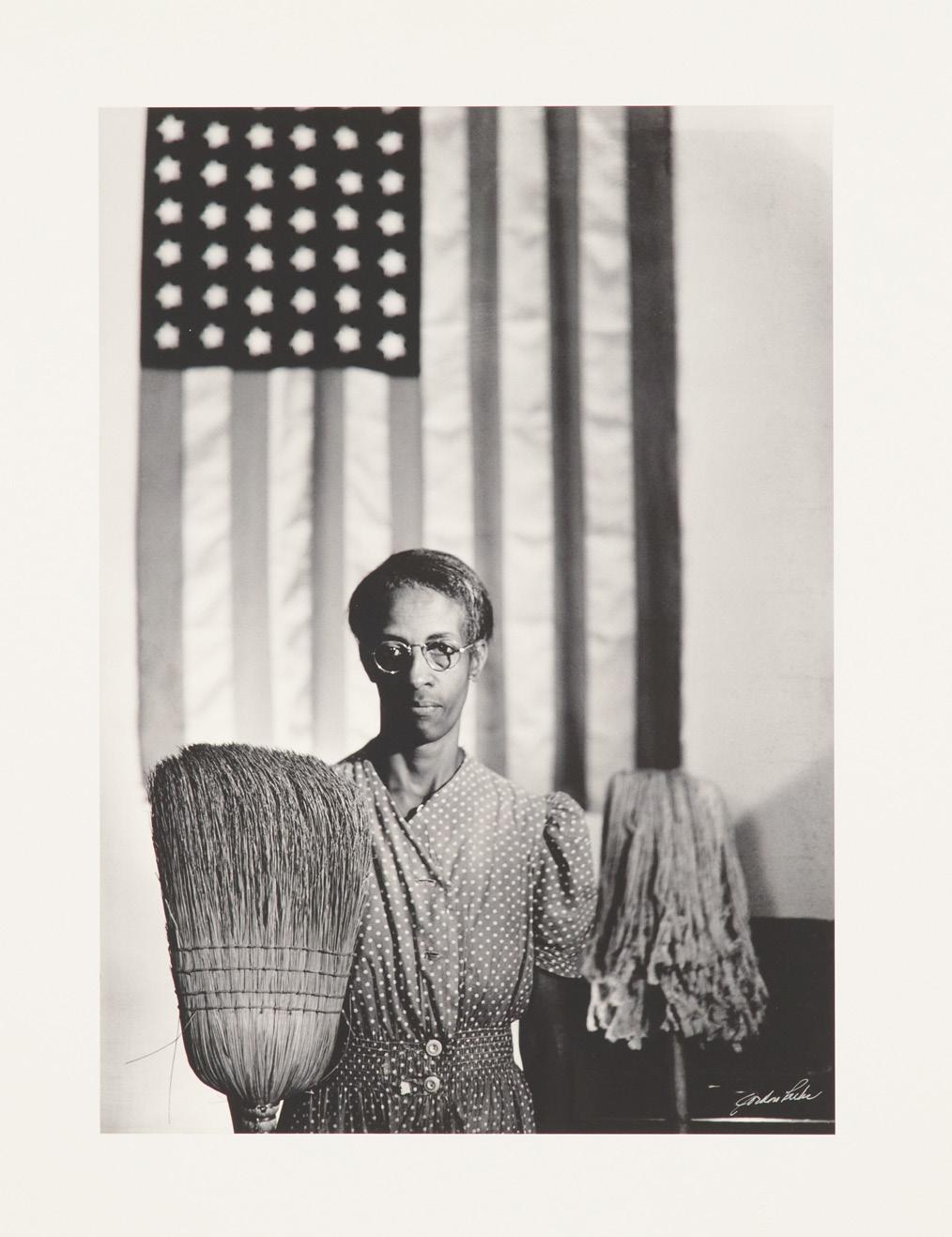

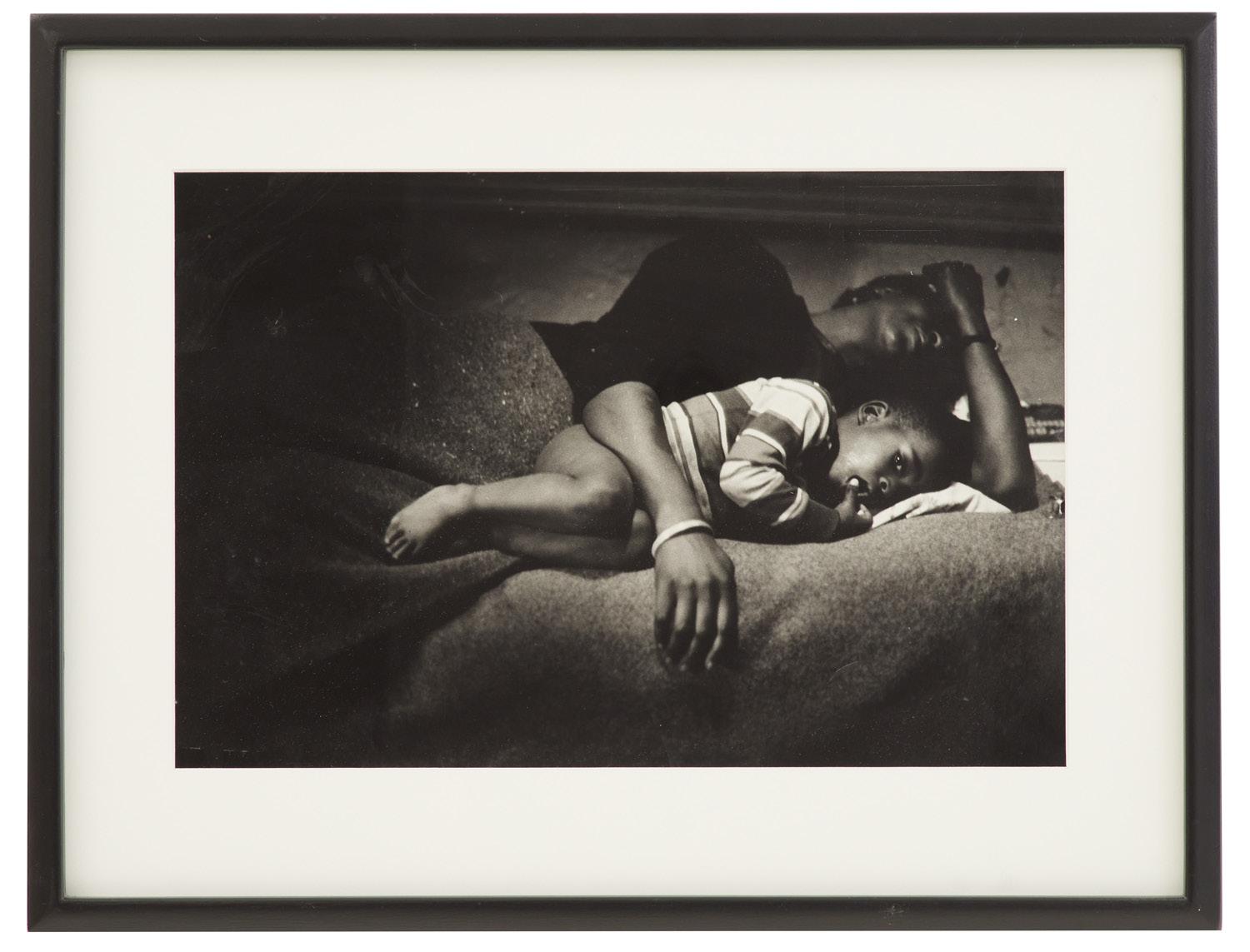

“Bessie and Little Richard (Fontenelle) the Morning After She Scalded Her Husband, Harlem, New York”

silver gelatin print, 18-1/4” x 23-3/4”

One of the most acclaimed American photojournalists of the 20th century, Parks was a staunch advocate for social justice and much of his work explores issues of poverty, racism, and civil rights.

The youngest of 15 children of a Kansas farmer and his wife, Parks taught himself

the rudiments of photography after purchasing a camera at a pawnshop. He worked as a freelance photographer, as well as working numerous odd jobs to support himself, until his series of photographs of Chicago’s South Side received national attention.

In 1942, in part because of these photos, Parks was awarded a fellowship from the prestigious Julius Rosenwald Foundation, an extraordinary honor for a self-taught photographer with no formal training. The fellowship afforded him the opportunity to re-locate to Washington D.C. for an apprenticeship at the Farm Security Administration (FSA), where he remained for several years, supplementing his income by taking fashion photos for such magazines as Vogue and Ebony. In 1948, he became the first, and was for many years, the only African American on staff at LIFE magazine. His work for the publication brought him to the attention of an even wider audience and gave him the opportunity to explore social justice issues.

Facing unemployment and increasingly frustrated by his inability to support his children, Richard frequently drank and became violent. Parks spent weeks following the family, capturing its members at some of their most fragile and vulnerable moments. Never losing his empathy, the resulting images are haunting and moving. In a somewhat unusual move for Parks, he was so affected by what he saw that he penned an introduction to the photos:

“

I too am America. America is me. It gave me the only life I know — so I must share in its survival. Look at me. Listen to me. Try to understand my struggle against your racism. There is yet a chance for us to live in peace beneath these restless skies.”

The photograph offered here was a part of a larger, multi-part 1968 LIFE magazine editorial on the plight of impoverished African Americans in the country’s largest cities. Parks, at the time the only African American staff photographer at the magazine, chose to follow the Fontenelle family of eleven — British West Indian immigrant father Richard, mother Bessie and their nine children, the youngest being 3-year-old Little Richard.

The full LIFE Magazine article with photographs is accessible at gordonparksfoundation.org

(AMERICAN, 1939-2020)

Goodacre began sculpting in 1969, with a small bronze of her daughter and had her first exhibition several years later. In 1994 she was elected a member of the National Academy of Design. Her sculptures and large-scale monuments are in countless private and public collections.

“Vietnam Women’s Memorial”, 1992 patinated bronze h. 27”, w. 27”, d. 18”

GLENNA GOODACRE

Dedication of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, Washington, D.C., 1993 “

That my hands can shape the clay which might touch the hearts and heal the wounds of those who serve fills me with humility and deep satisfaction. I can only hope that future generations who view the sculpture will stand in tribute to these women who served during the Vietnam era...”

- William Gottlieb “

I learned to shoot very carefully. I knew the music. I knew the musicians. I knew in advance when the right moment would arrive. It was purposeful shooting.”

9-7/8” x 8”

“Sidney Bechet” gelatin silver print

The Brooklyn-born Gottlieb was a self-taught photographer whose images of golden age jazz performers such as Billie Holliday, Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong permeated American culture. He photographed famed jazz soloist Sidney Bechet on several occasions and the image offered in this lot is perhaps the most famous.

The famed jazz soloist Sidney Bechet was equally at home with the clarinet and the saxophone.

Born in New Orleans to a middle class African American musical family, he began performing with his brothers while still a child, working with many of the city’s most accomplished jazz musicians. In his teens, Bechet traveled to Chicago and New York and eventually to Europe with the Southern Syncopated Orchestra. In 1925, as part of the infamous La Revue Negre, whose most famous member was Josephine Baker, Bechet traveled to Paris. While his experience in France was not without issue – he briefly spent time in a Paris jail — he discovered more acceptance, popularity, and personal freedom than he did in the United States. He was to spend much of his time in Europe and, in the early 1950s, Bechet emigrated to France permanently.

GOTTLIEB

WILLIAM

(AMERICAN, 1917-2006)

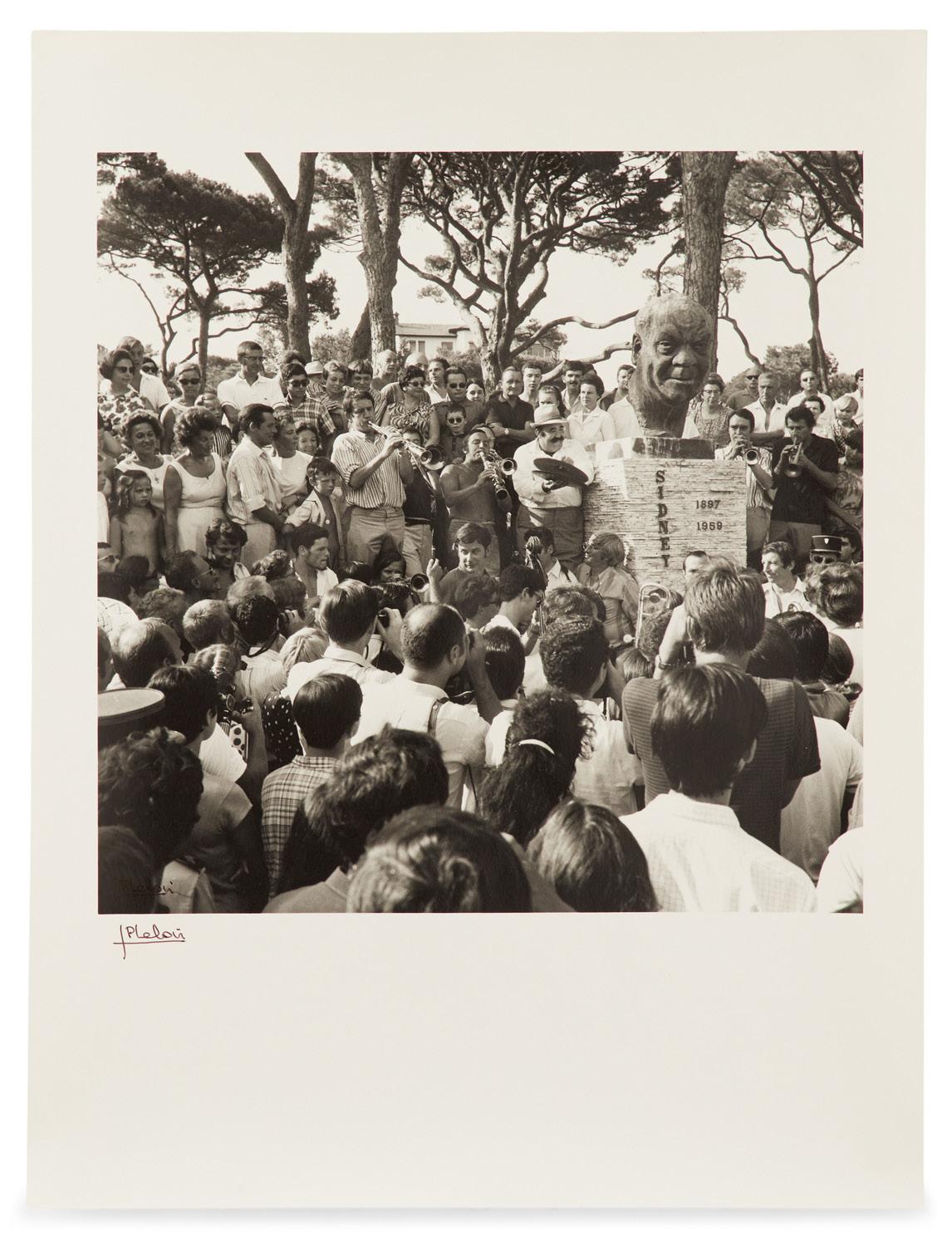

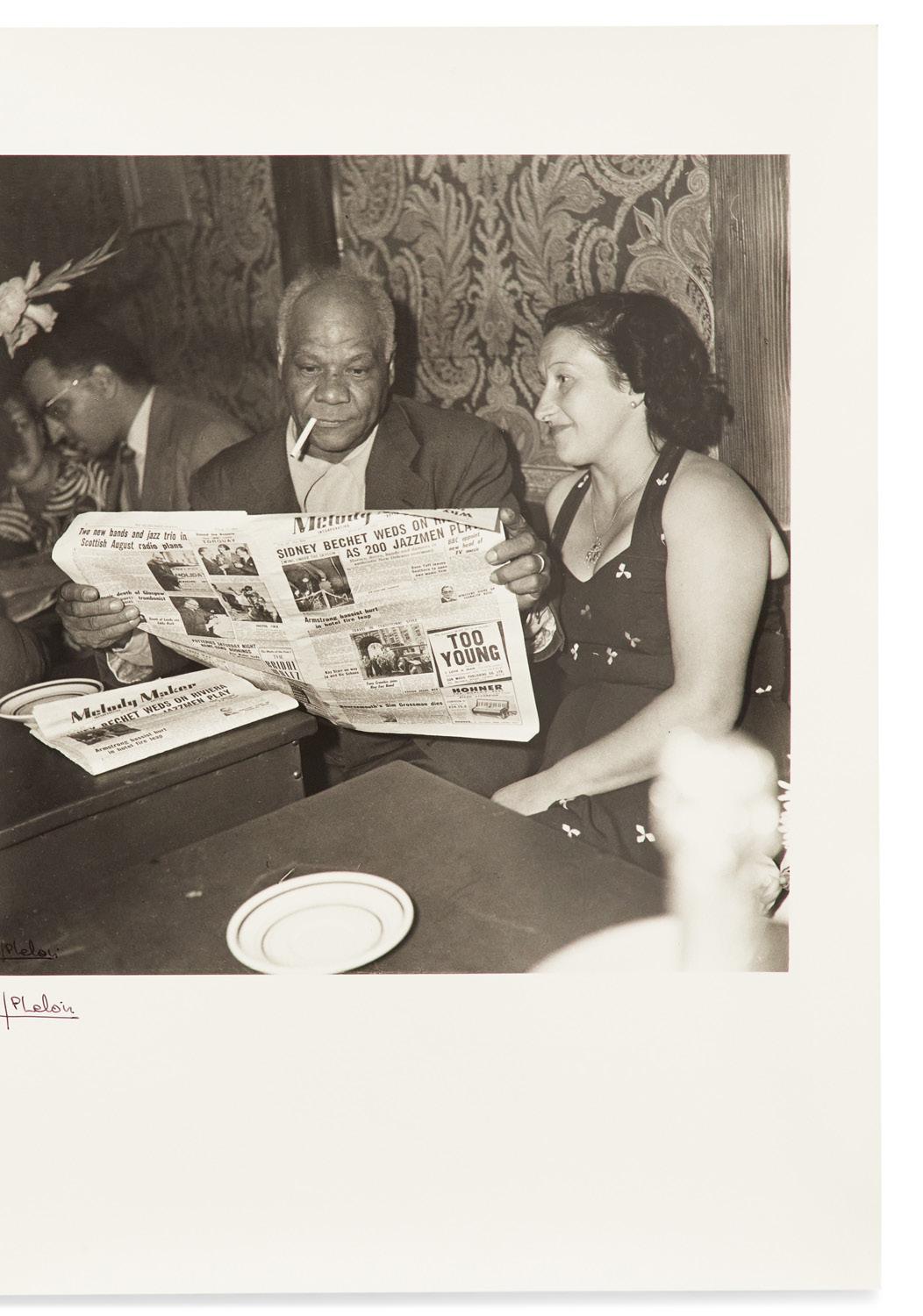

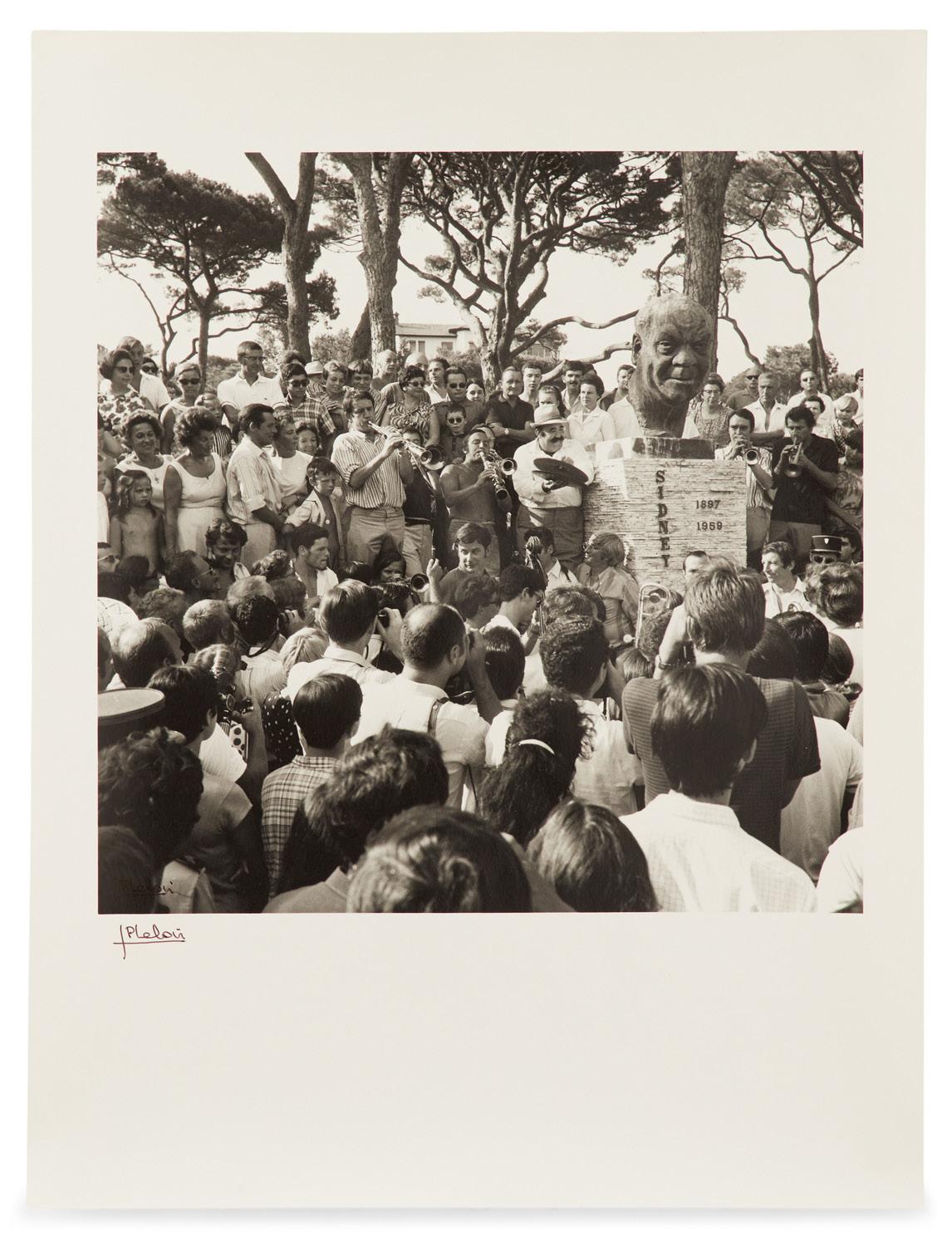

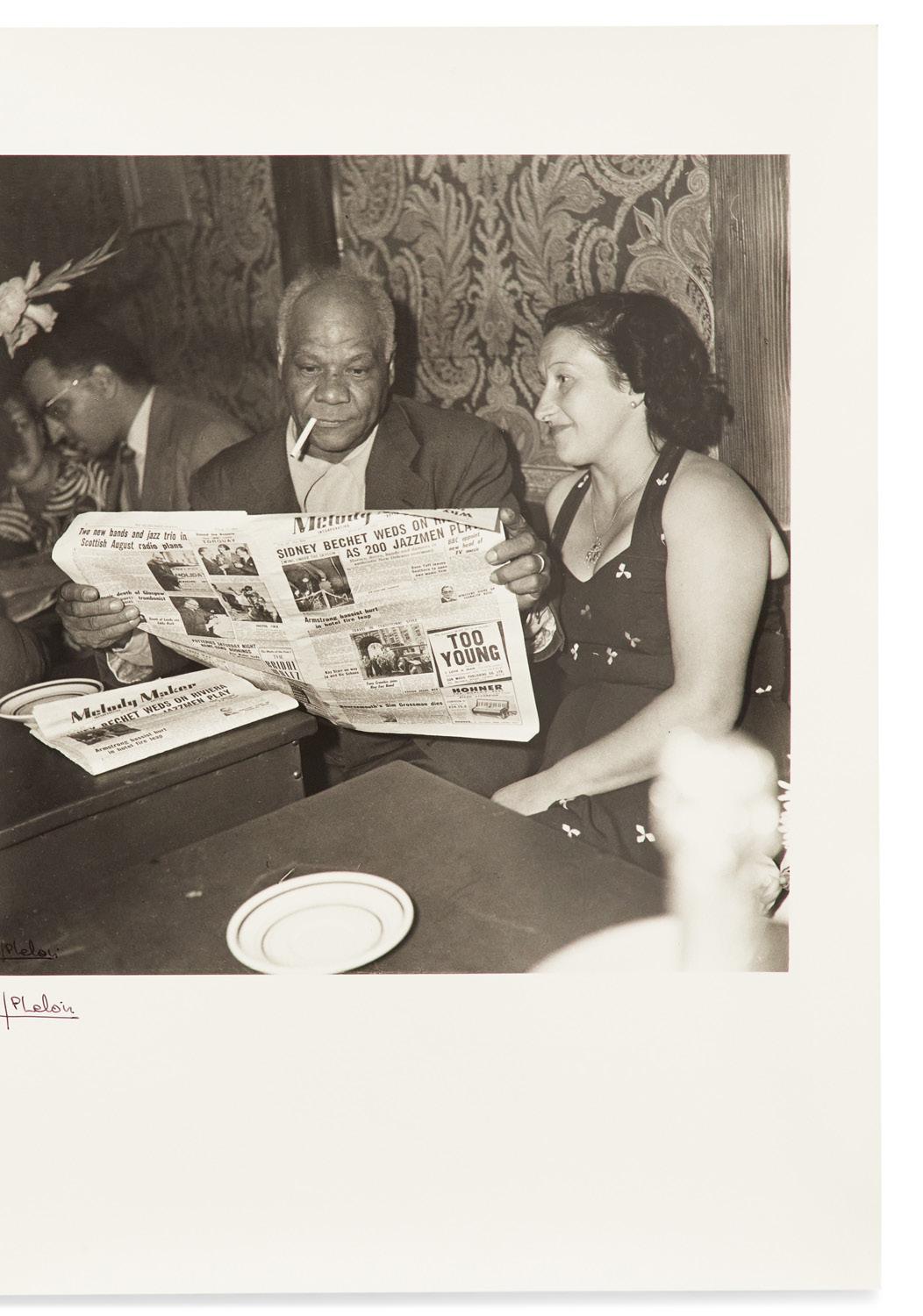

JEAN-PIERRE LELOIR

(FRENCH, 1931-2010)

“Inauguration Du Buste De Sidney Bechet”, 1960

gelatin silver print

15-3/4” x 12”

“Vieux Colombier, Sidney Bechet, Lionel Hampton, Claude Luter”, 1956

gelatin silver print

15-3/4” x 11-7/8”

A native of Paris, Leloir was fortuitously gifted his first camera by an American serviceman during the Liberation of Paris; by the early 1950s he was being published in newspapers, magazines and journals. Considered one of the pre-eminent jazz photographers, Leloir had a genuine appreciation of the musicians and his love for their work is evident in his vibrant black and white images.

I loved the people I photographed, so I made myself as available, yet as discreet as possible... I wanted them to forget my presence so I could catch those little unexpected moments.” “

Leloir photographed such jazz luminaries as Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Chet Baker, Billie Holiday and Sidney Bechet — the New Orleans-born, Parisian expatriate musician and subject of the work offered here. In appreciation and acknowledgment of his work, Leloir was honored by the city of New Orleans. Leloir did not confine himself to just one musical style, and his photographs of Edith Piaf, Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones were also lauded by critics and collectors. In 2010, he was named a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Artes des Lettres, France’s highest honor.

“Vieux Colombier, Sidney And Elisabeth Bechet”, 1952 gelatin silver print

15-3/4” x 12-1/8”

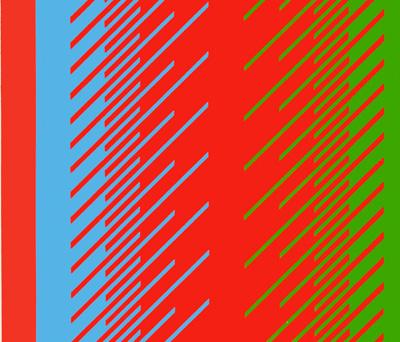

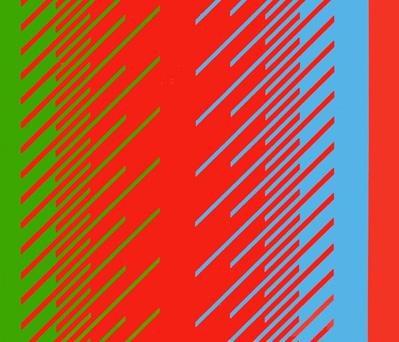

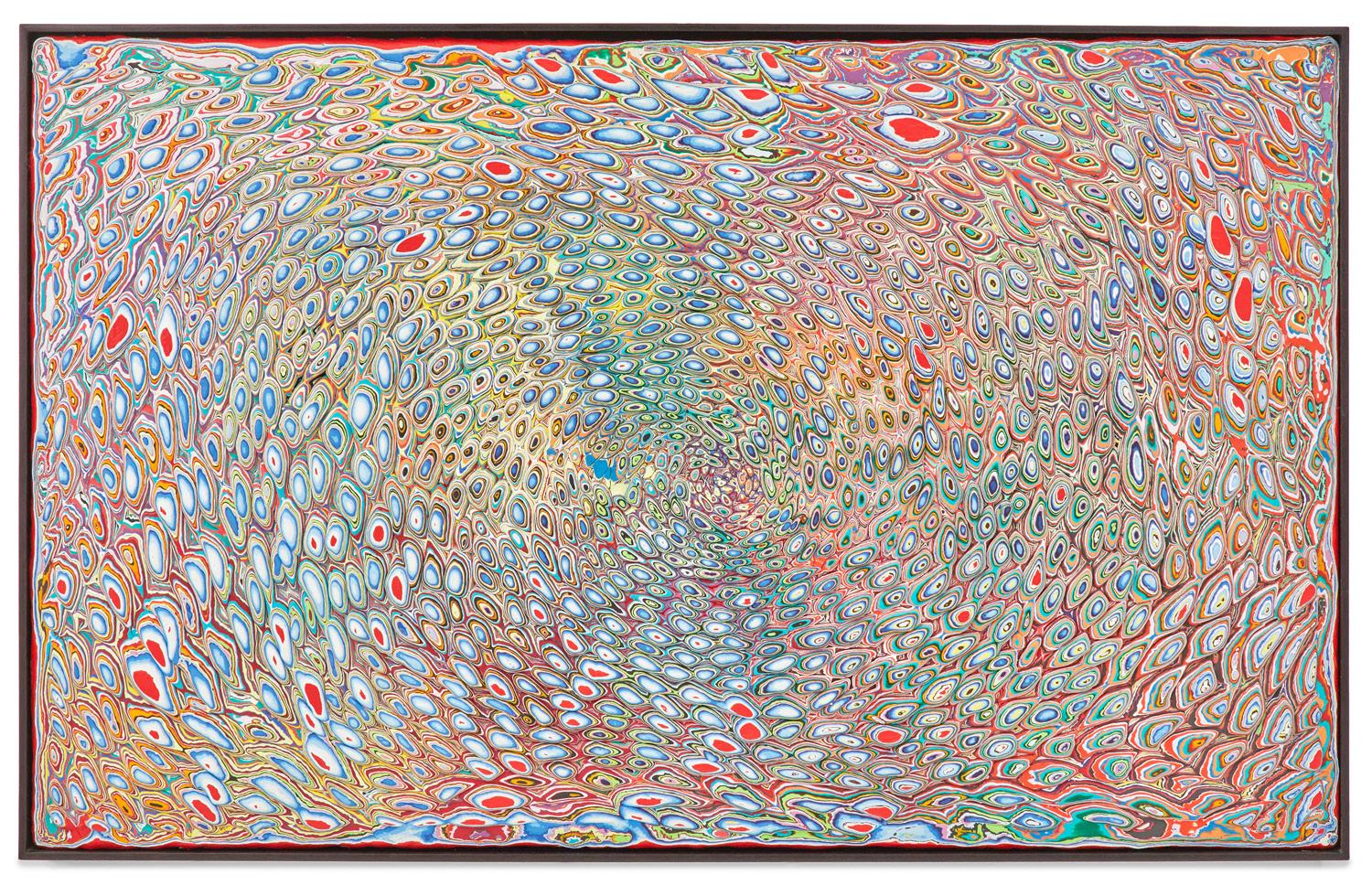

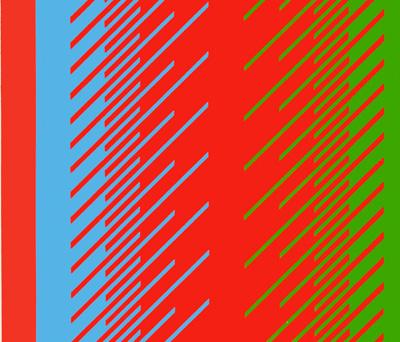

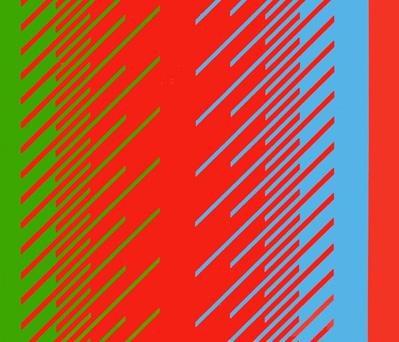

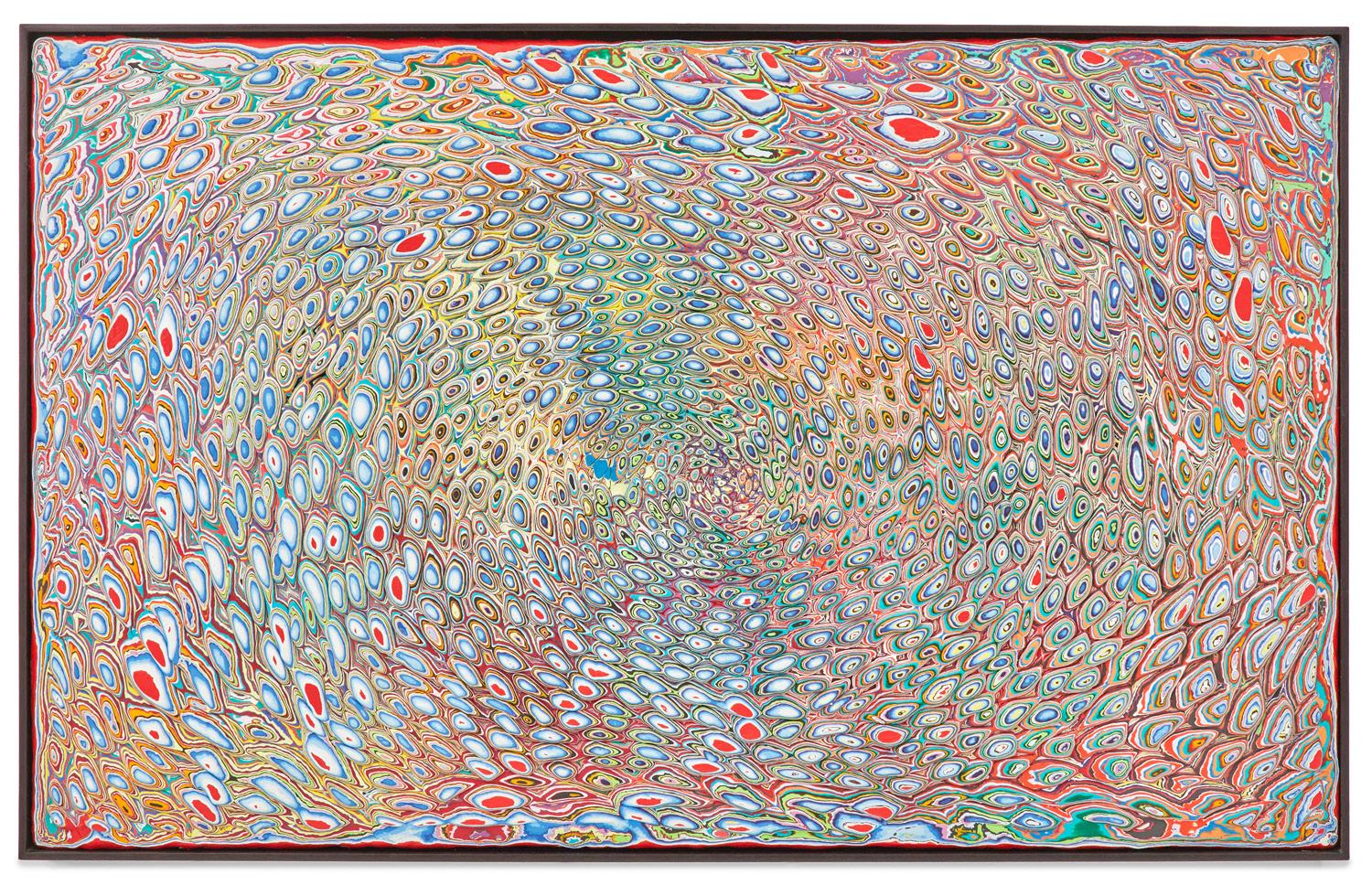

"The ideas I work with are essentially timeless … Working with basic ideas will always be exciting, and if a color or form is visually exciting in any profound sense, it will be that way in 10 or 20 years from now.”

- Richard Anuszkiewicz, 1977

“Reflection IV-Red”, 1979 hand-painted color silkscreen on masonite

82” x 48”

Awunderkind of color theory, Richard Anuszkiewicz’s pigments seem to hum, vibrate, radiate, and swell. He studied under the prominent Bauhaus artist and teacher Josef Albers at Yale in the 1950s, where he learned from Albers that the interactions of high-intensity hues and repetitious geometric compositions could produce optical and perceptual effects. However, Anuszkiewicz took his mentor’s interest in geometric abstraction and color contrast even farther by presenting an exceptional range of tonal harmonies when he honed his increasingly meticulous vision in New York in the 1960s.

Apart from his skillful ability to bring color to life on the canvas, Anuszkiewicz also displayed a masterful command of line as a compositional tool. Altering the length, width, and spacing of lines allowed him to create illusory planes and structures, which playfully warped the perception of the viewer further. Incorporating these fantastical and psychedelic trompe-l’oeil effects into his work made him a pioneer of Op Art. Though the movement was short-lived, Anuszkiewicz never stopped pursuing his fascination with how some formal elements, such as color and line, could create powerful perceptual effects for the viewer.

(AMERICAN, 1930-2020)

As the years progressed, Anuszkiewicz’s work became more meditative; throughout the 1970s, he began placing square and rectangular wood constructions in the center of his canvases with lines emanating from them. This is evident in Reflection IV-Red (1979), where the silkscreen appears to beam like a neon light due to the intense combination of hues, as well as the strategically placed lines. Despite the hard edges and repetition that had become key elements of his oeuvre, the radiating effect of the work seems to inspire a level of spirituality.

Over the course of his sixty-year-long career, Anuszkiewicz demonstrated an exceptional commitment to pure and precise abstraction. Though he dabbled with different shapes, forms, and mediums, he never strayed from his ultimate vision of creating a spiritual purity that he believed could only be found in the interactions of color and line. Anuszkiewicz’s legacy continues the tradition of geometric, highly pigmented abstraction through the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first.

ANUSZKIEWICZ

RICHARD

“Die

bronze h. 15-1/4”, w. 7-3/4”, d. 8-3/8”

Fritz Klimsch (German, 1870-1960)

Hockende”, 1950 patinated

Richard Johnson (American/Louisiana, b. 1942) “Scraper”, 2004 mixed media with paper collage on board 18-1/2” x 12-1/2”

Richard Johnson (American/Louisiana, b. 1942) “Scraper”, 2004 mixed media with paper collage on board 18-1/2” x 12-1/2”

Richard Johnson (American/Louisiana, b. 1942) “Scraper”, 2004 mixed media with paper collage on board 18-1/2” x 12-1/2”

b.

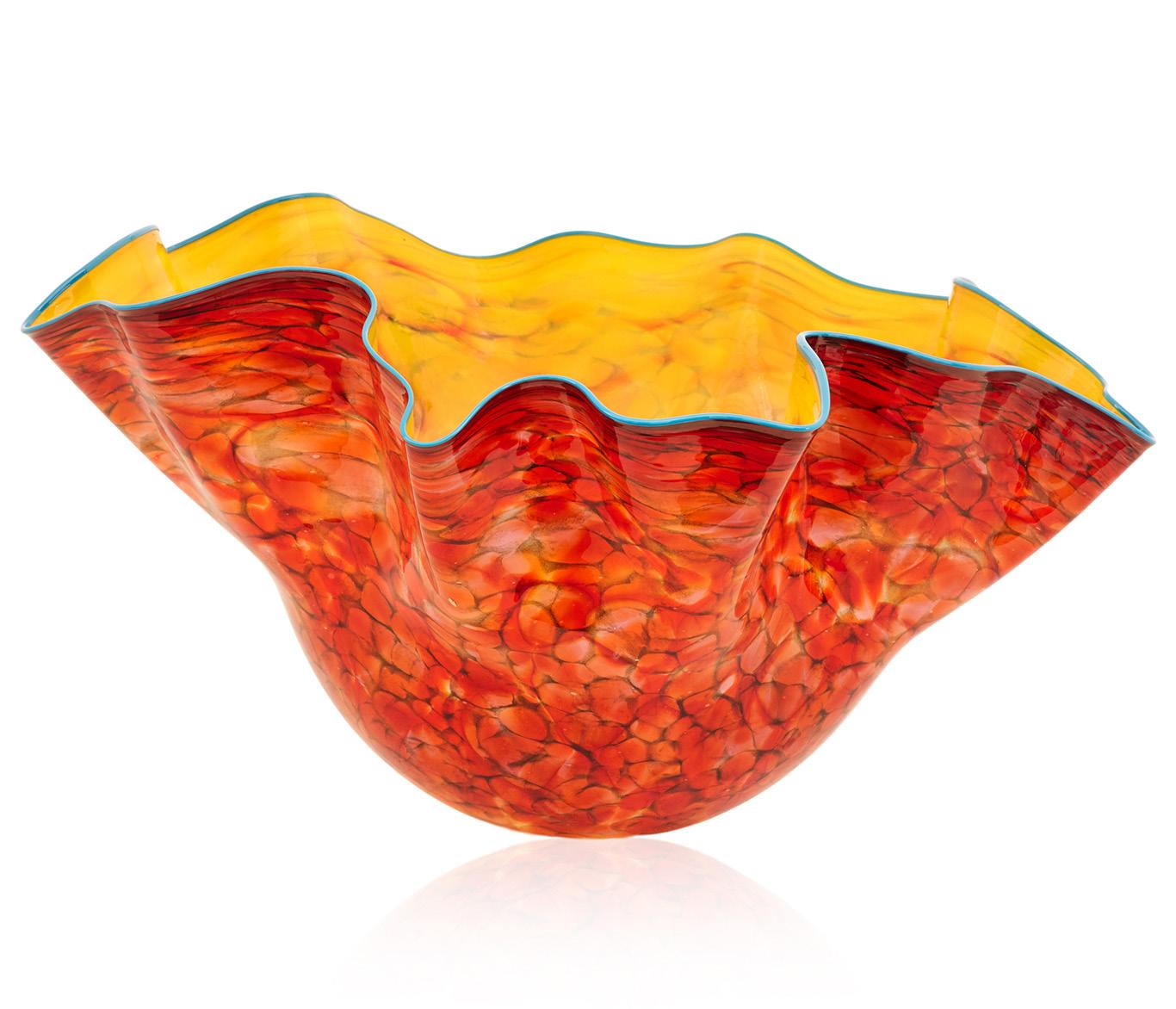

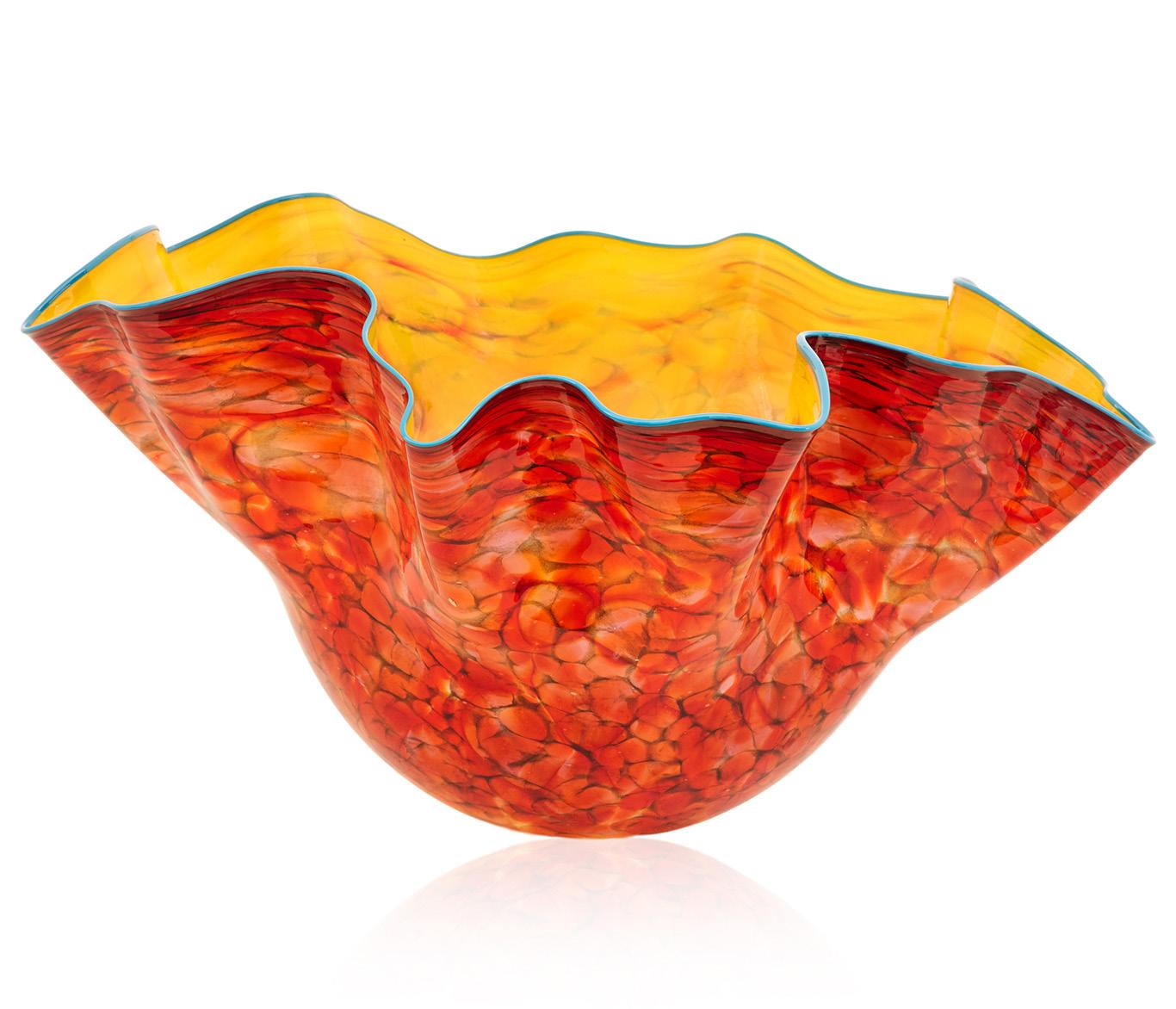

Dale Chihuly (American, b. 1941)

Monumental Winter Yellow Macchia with Ice Blue Lip, 1999 hand-blown glass h. 20”, w. 37”, d. 33”

670 Lounge Chair and 671 Ottoman 1970s, leather, laminated oak and enameled aluminum chair h. 32”, w. 33”, d. 29”; ottoman h. 17-1/2”, 25-1/2”, d. 22”

“Personnages”, 1989 silkscreen on paper 16-7/8” x 30”

Eduardo Arroyo (Spanish, 1937-2018)

Charles and Ray Eames for Herman Miller

Eduardo Arroyo (Spanish, 1937-2018)

Charles and Ray Eames for Herman Miller

Eduardo Arroyo (Spanish, 1937-2018)

“Personnages”, 1988 lithograph in colors 25-3/4” x 19-7/8”

Pierre Casenove (French, b. 1943)

“Visage”, 1994 (one of two) gilt-bronze h. 7-1/4”, w. 7-1/2”, d. 2”

Eduardo Arroyo (Spanish, 1937-2018)

“Personnages”, 1988 lithograph in colors 25-3/4” x 19-7/8”

Pierre Casenove (French, b. 1943)

“Visage”, 1994 (one of two) gilt-bronze h. 7-1/4”, w. 7-1/2”, d. 2”

“150501i”,

Holton Rower (American/New York, b. 1962)

2015 cut paint on plywood 31-1/4” x 49-3/4”

Ida Rittenberg Kohlmeyer (American/Louisiana, 1912-1997) “Little Stacked”, 1990 carved and painted wood h. 12-1/2”, w. 5-3/4”, d. 3-3/8”

Luis Feito (Spanish, 1929-2021)

“Carcajon”

lithograph on paper

20-1/4” x 18-3/4”

Simon Kidd (Irish, b. 1993)

“Stratum”, 2020 wood-fired, slip-cast stoneware h. 6”, w. 6-3/4”, d. 6-1/4”

Philippe Starck for FLOS, Italy

“Ara” Table Lamp

1998 chromed brass, chromed steel and glass

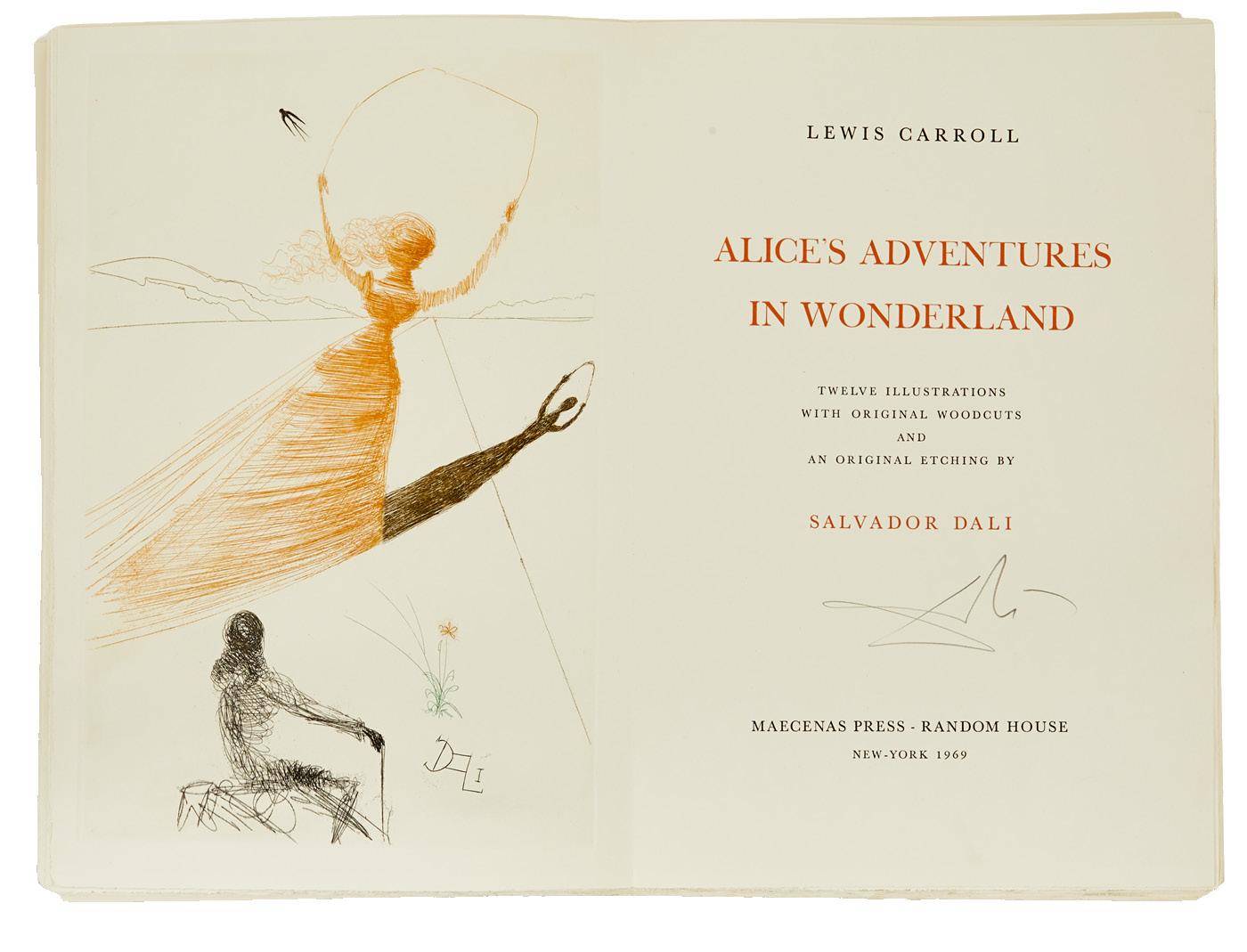

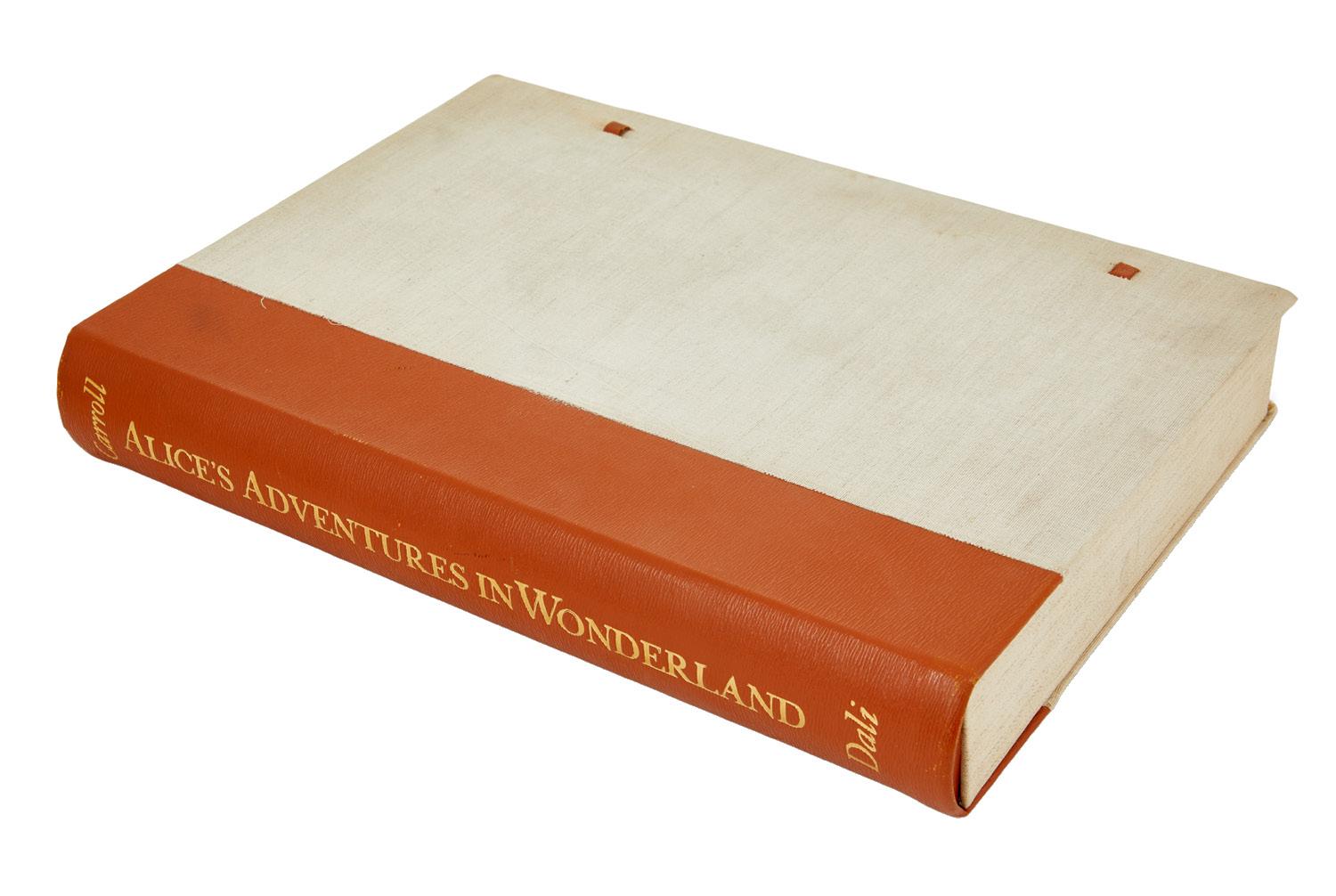

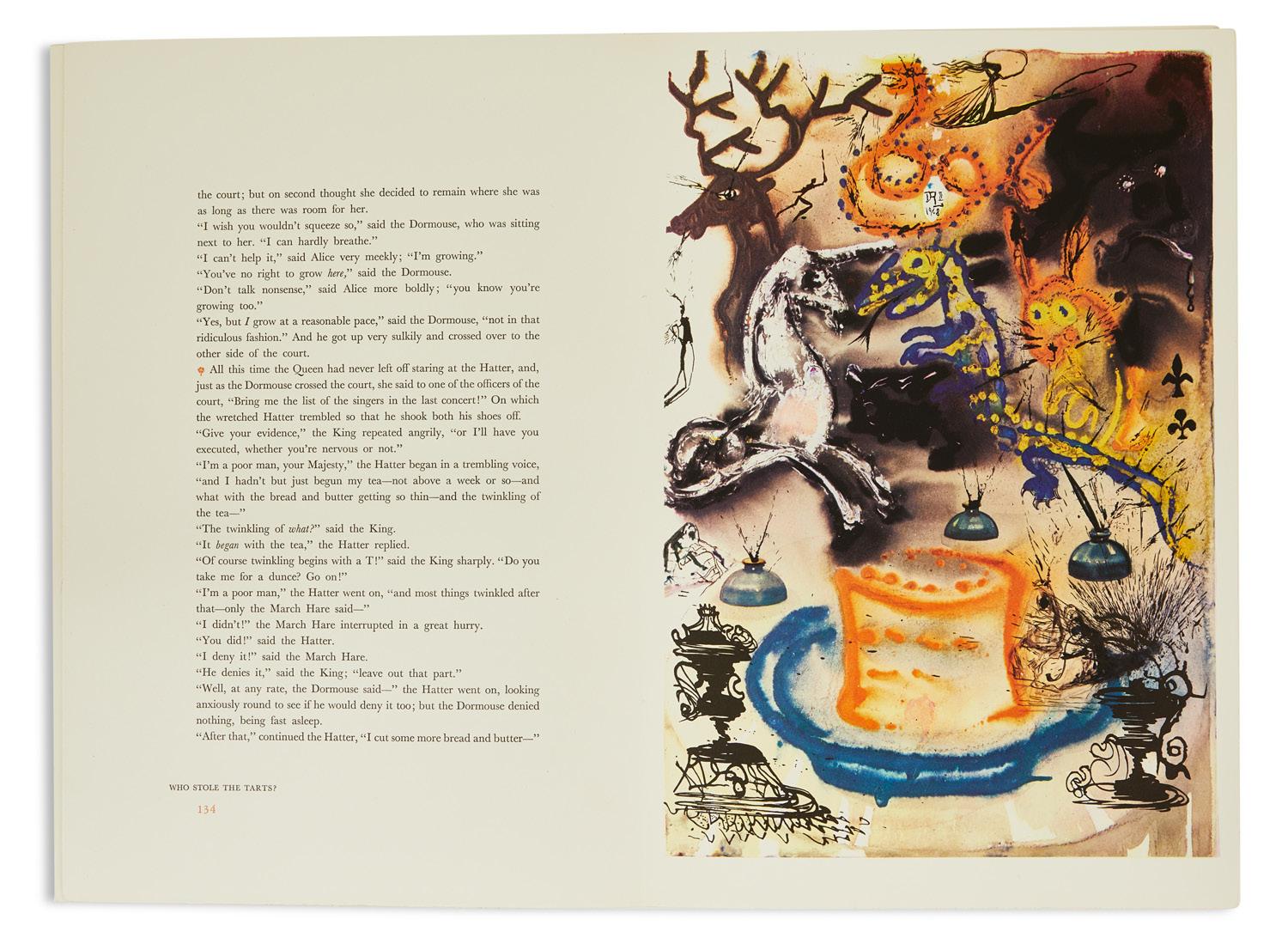

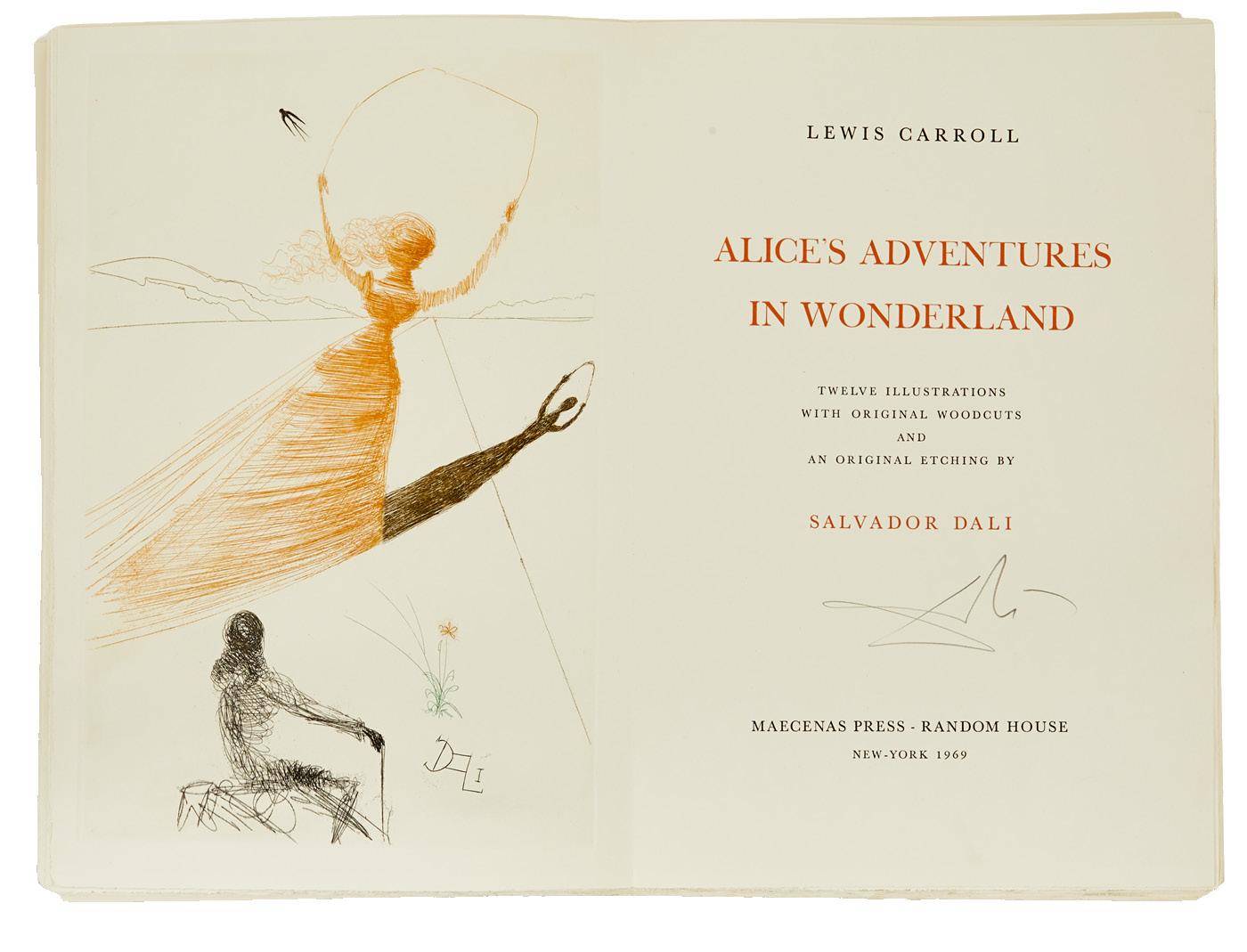

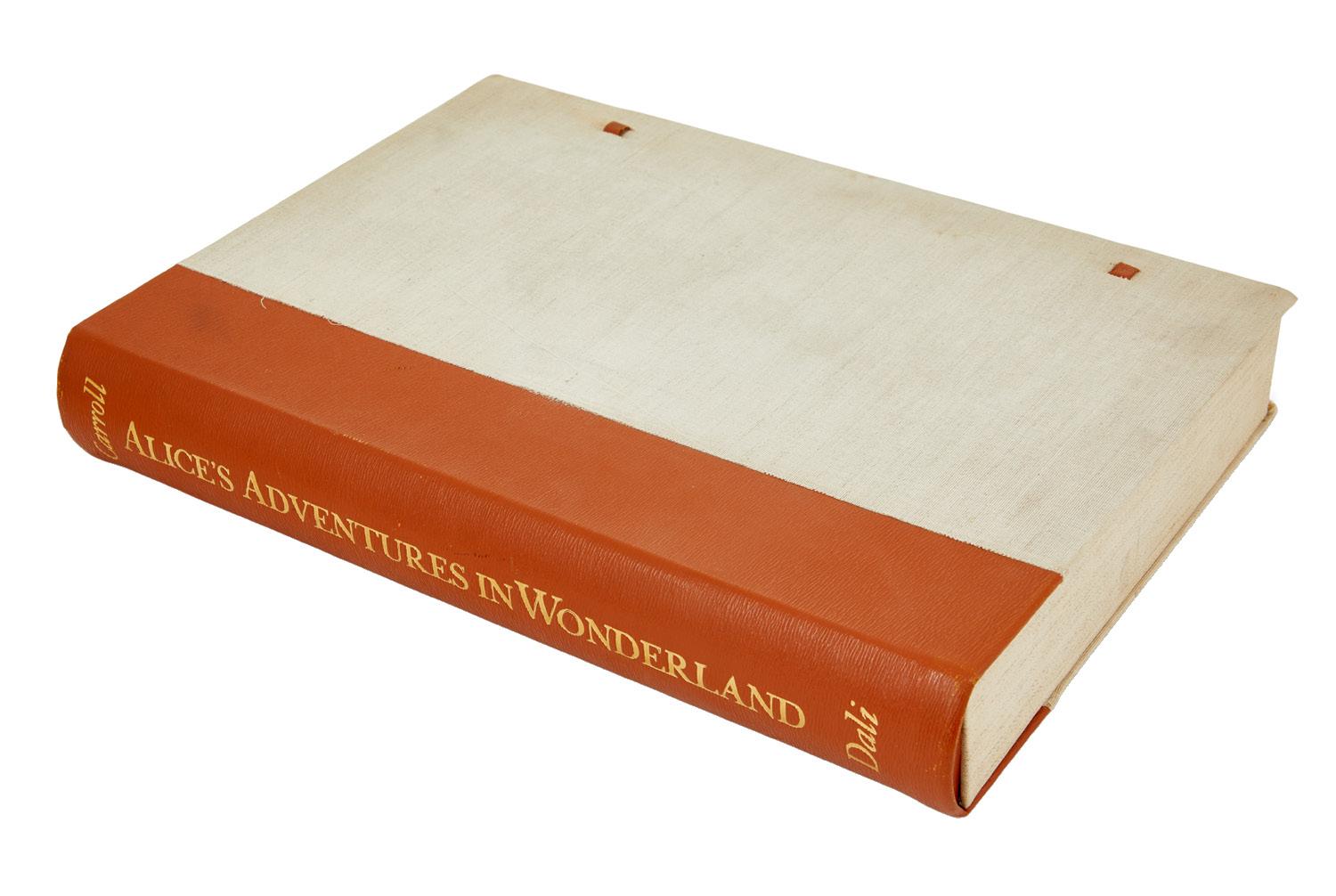

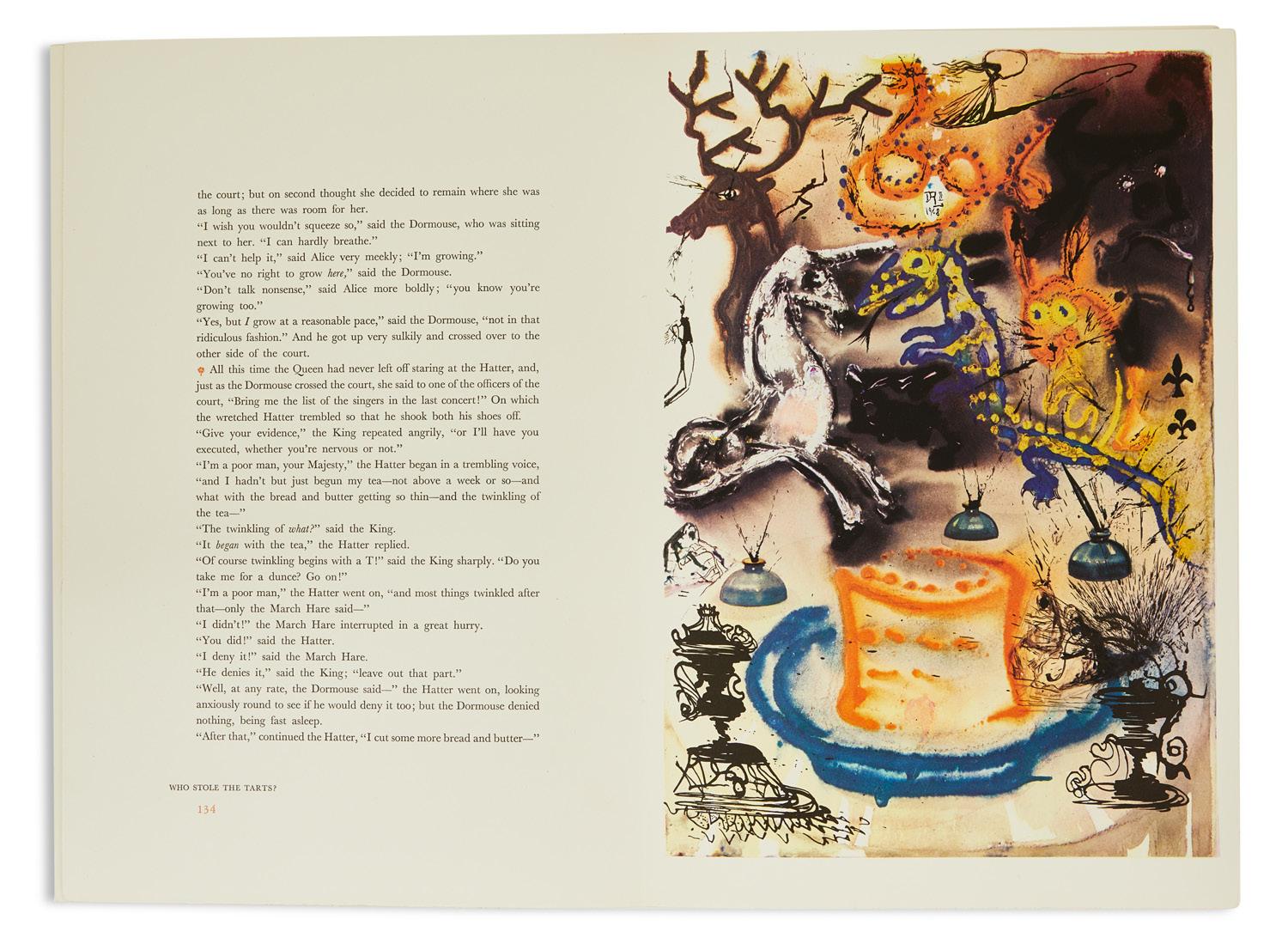

Lewis Carroll (British, 1832-1898) and Salvador Dali (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Maecenas Press - Random House, 1969

18-1/2” x 13-1/4”

Lewis Carroll (British, 1832-1898) and Salvador Dali (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Maecenas Press - Random House, 1969

18-1/2” x 13-1/4”

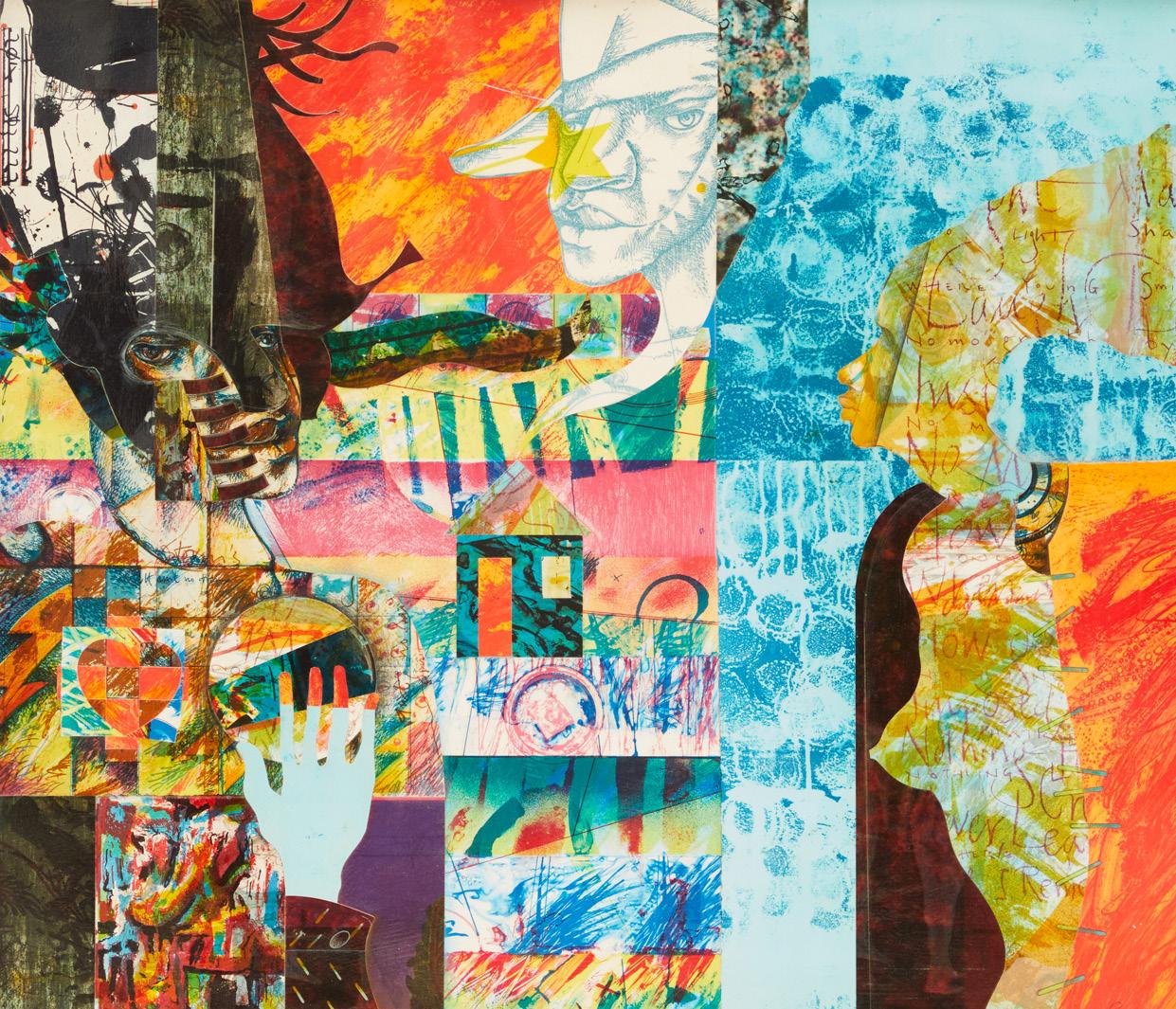

Romare Bearden

(American, North Carolina, 1911-1988)

“Out Chorus, Rhythm Section”, 1979

lithograph from the Jazz Series

23-5/8” x 33-1/4”

Pair of Scandinavian Chairs in the manner of Wilhelm Kienzle 1970s, beechwood and leather h. 32-1/2”, w. 23-1/2”, d. 25-1/2”

Milo Baughman for Thayer Coggin “Giant Swivel Chair”

1970s, strie velvet h. 26”, w. 41”, d. 41”

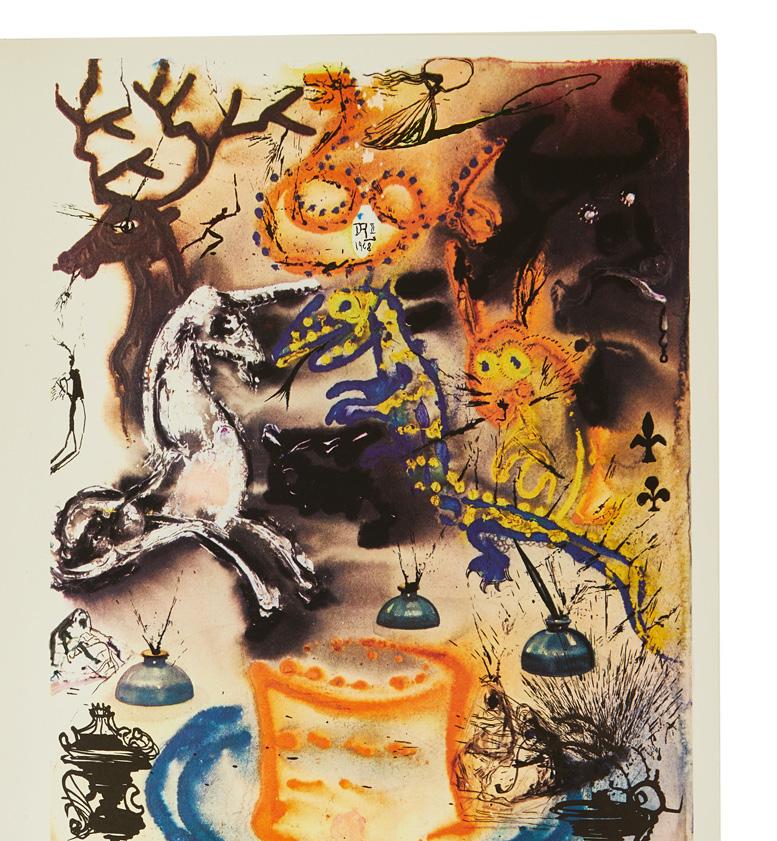

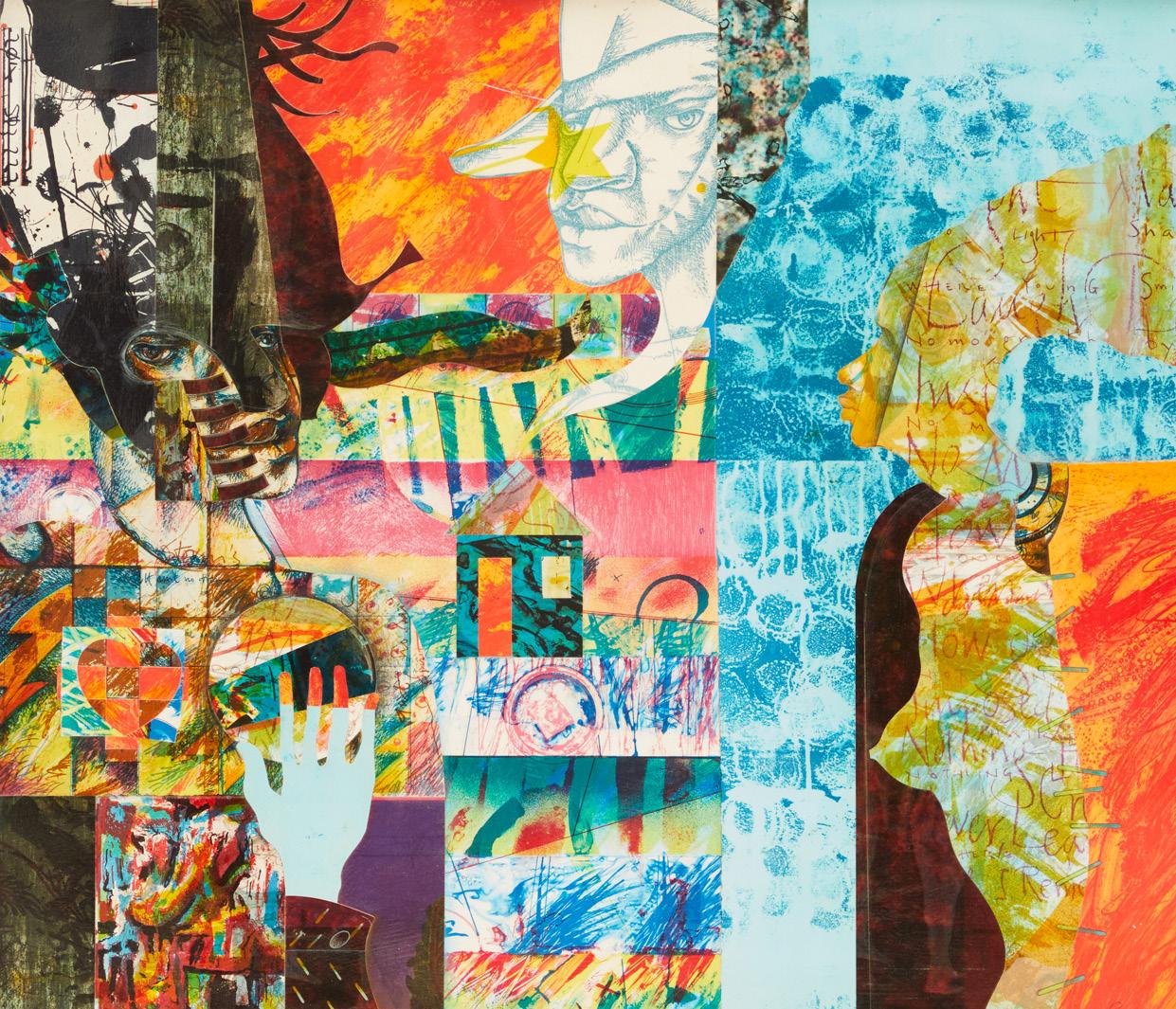

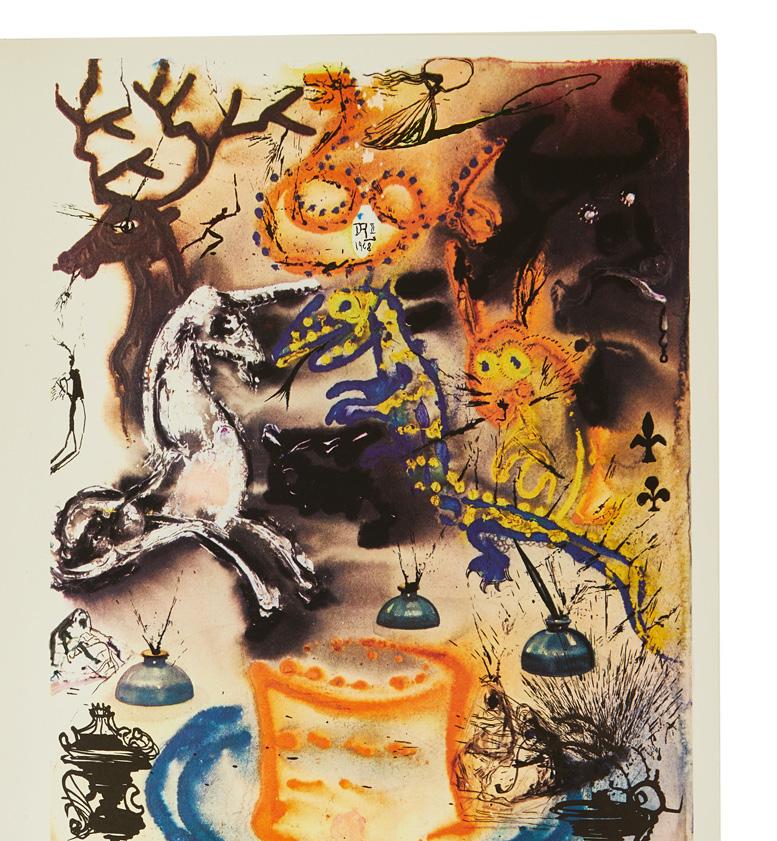

Charles Kvapil (French, Belgian, 1884-1957)

“Bouquet de Pavots” oil on canvas 19-1/4” x 22-1/2”

Milo Baughman for Thayer Coggin “Giant Swivel Chair”

1970s, strie velvet h. 26”, w. 41”, d. 41”

Charles Kvapil (French, Belgian, 1884-1957)

“Bouquet de Pavots” oil on canvas 19-1/4” x 22-1/2”

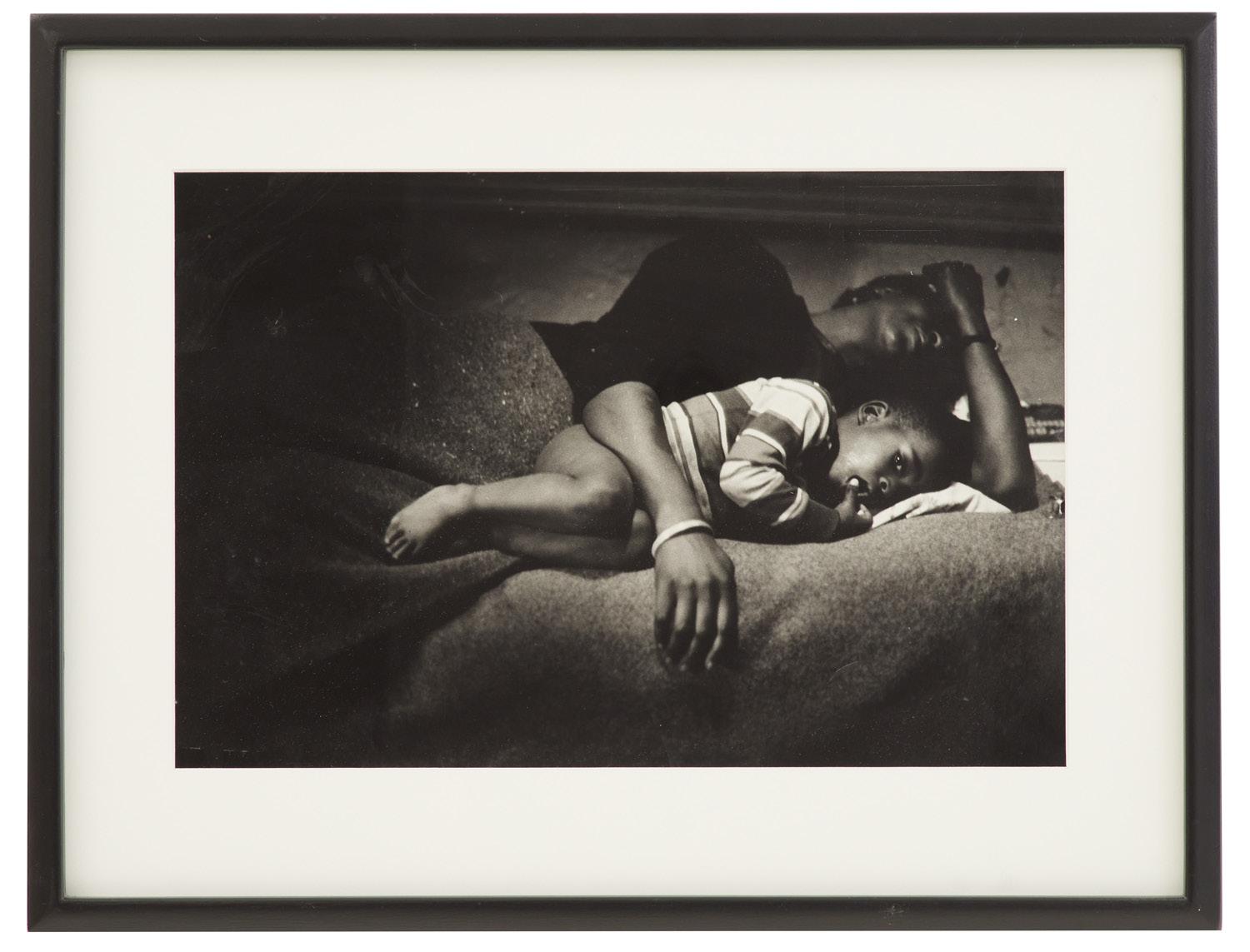

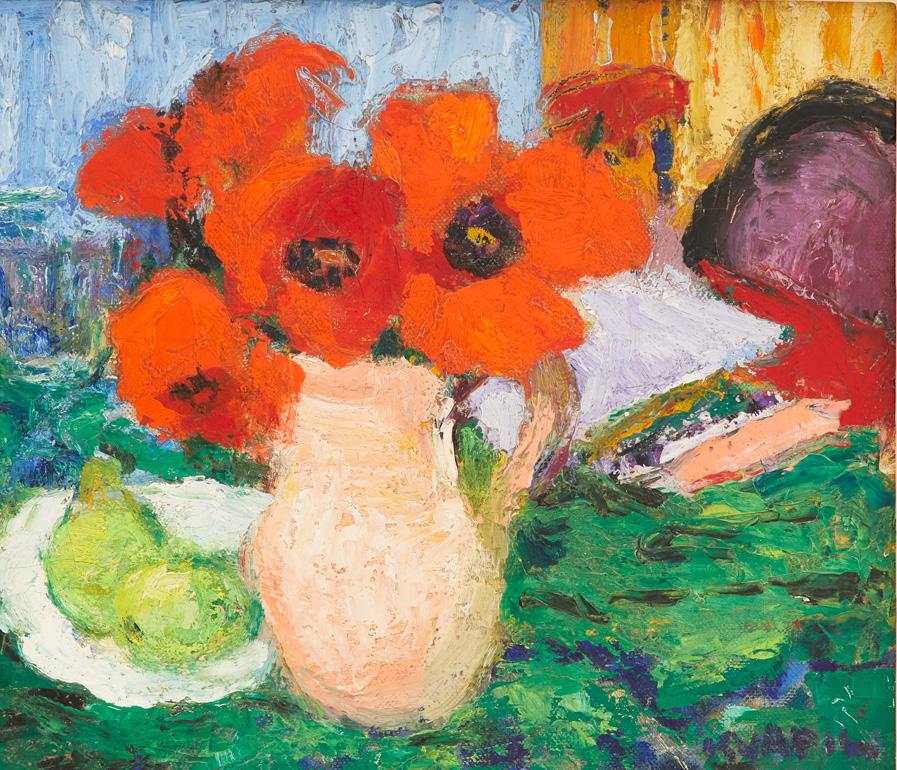

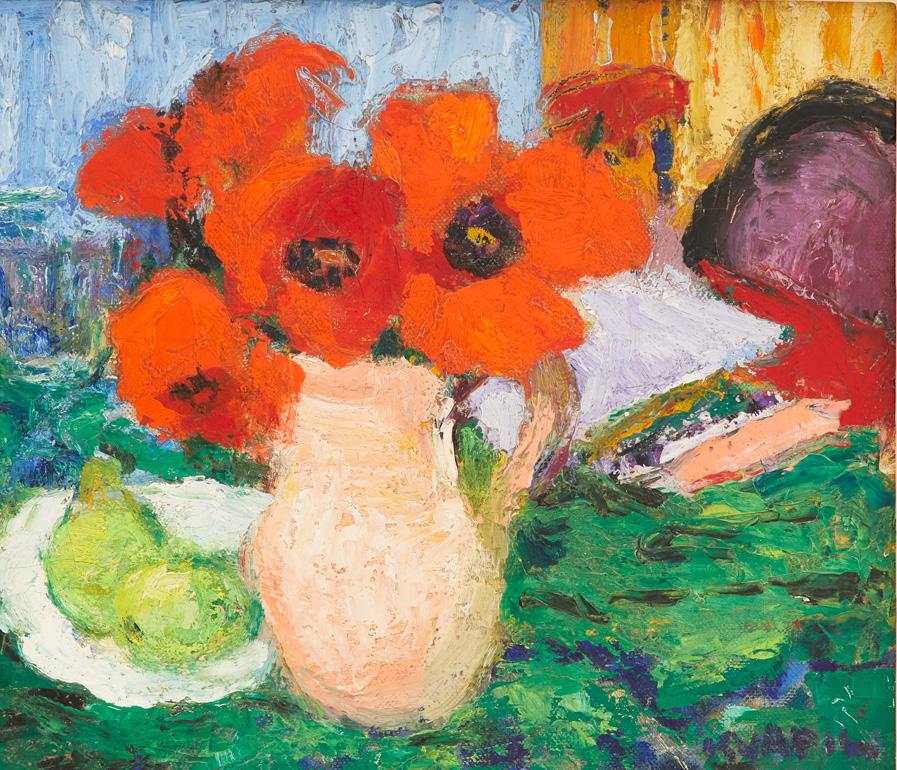

John Tarrell Scott (American/Louisiana, 1940-2007)

John Tarrell Scott (American/Louisiana, 1940-2007)

36” x 40-1/2”

“1619 Not Yet”, 1997 mixed media collage on paper

Jelena Restovic James Director of Fine Art

jelena@neworleansauction.com

504.566.1849 SPECIALISTS

504.566.1849

Associate Specialist: Sophie Curtis

Michele Carolla, Senior Specialist, Fine Art

michele@neworleansauction.com

CATALOGUE PHOTOGRAPHY: Christa Ougel

Location Photoshoot at Virgin Hotel, New Orleans

CREATIVE DIRECTOR | Amelia Schussler

PHOTOGRAPHER | Jacqueline Marque

PRODUCER | John-Robert Horville

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY | Sam Aguirre-Kelly

LIGHTING TECHNICIAN | Brett Felty

OPERATIONS | Cedric Roberts, Cassius Brown, Willy Williams

&CONTEMPORARY MODERN 04.18.24 ART + DESIGN New Orleans Auction Galleries 333 Saint Joseph St. New Orleans, LA 70130 504.566.1849 info@neworleansauction.com neworleansauction.com LA AB 363

George Dayez (French, 1907- 1991)

“Femme Se Coiffant”, 1955/6 oil on canvas, 32” x 38”

George Dayez (French, 1907- 1991)

“Femme Se Coiffant”, 1955/6 oil on canvas, 32” x 38”

Eduardo Chillida (Spanish, 1924-2002)

“Chicago”

lithograph on Rives paper, 41-1/8” x 29”

Eduardo Chillida (Spanish, 1924-2002)

“Chicago”

lithograph on Rives paper, 41-1/8” x 29”

- Christopher Wool in conversation with Nicolas Trembley for Numéro

- Christopher Wool in conversation with Nicolas Trembley for Numéro

Curtis Jere “Skyscraper” Table Lamp

1970s, chrome, h. 37-1/2”, w. 17-1/2”, d. 17-1/2”

Ingo Maurer “Zettel’z 5” Pendant Light Fixture

1997, Germany

stainless steel, frosted glass, and Japanese paper, dia. 40-42” (variable)

Curtis Jere “Skyscraper” Table Lamp

1970s, chrome, h. 37-1/2”, w. 17-1/2”, d. 17-1/2”

Ingo Maurer “Zettel’z 5” Pendant Light Fixture

1997, Germany

stainless steel, frosted glass, and Japanese paper, dia. 40-42” (variable)

Georges Rouault (French, 1871-1958)

“Le Port,” painted and glazed ceramic, 7-7/8” x 18”

Georges Rouault (French, 1871-1958)

“Le Port,” painted and glazed ceramic, 7-7/8” x 18”

Noel Rockmore (American/Louisiana, 1928-1995)

“Coney Island: Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs”, 1964, oil on masonite, 25” x 37”

Mario Villa

(Nicaraguan/Louisiana, 1953-2021)

Mixed Metal Floor Lamp, h. 78-3/4”, dia. 25”

Noel Rockmore (American/Louisiana, 1928-1995)

“Coney Island: Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs”, 1964, oil on masonite, 25” x 37”

Mario Villa

(Nicaraguan/Louisiana, 1953-2021)

Mixed Metal Floor Lamp, h. 78-3/4”, dia. 25”

Ralph Lauren Silvered Bronze and Burkina Stone-Top Gueridon silvered bronze, stone h. 30”, dia. 29”

Ralph Lauren Silvered Bronze and Burkina Stone-Top Gueridon silvered bronze, stone h. 30”, dia. 29”

David Parks (American, b. 1944)

“Portrait of Gordon Parks”, 2021 archival pigment print, 22” x 17”

David Parks (American, b. 1944)

“Portrait of Gordon Parks”, 2021 archival pigment print, 22” x 17”

Richard Johnson (American/Louisiana, b. 1942) “Scraper”, 2004 mixed media with paper collage on board 18-1/2” x 12-1/2”

Richard Johnson (American/Louisiana, b. 1942) “Scraper”, 2004 mixed media with paper collage on board 18-1/2” x 12-1/2”

Eduardo Arroyo (Spanish, 1937-2018)

Charles and Ray Eames for Herman Miller

Eduardo Arroyo (Spanish, 1937-2018)

Charles and Ray Eames for Herman Miller

Eduardo Arroyo (Spanish, 1937-2018)

“Personnages”, 1988 lithograph in colors 25-3/4” x 19-7/8”

Pierre Casenove (French, b. 1943)

“Visage”, 1994 (one of two) gilt-bronze h. 7-1/4”, w. 7-1/2”, d. 2”

Eduardo Arroyo (Spanish, 1937-2018)

“Personnages”, 1988 lithograph in colors 25-3/4” x 19-7/8”

Pierre Casenove (French, b. 1943)

“Visage”, 1994 (one of two) gilt-bronze h. 7-1/4”, w. 7-1/2”, d. 2”

Lewis Carroll (British, 1832-1898) and Salvador Dali (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Maecenas Press - Random House, 1969

18-1/2” x 13-1/4”

Lewis Carroll (British, 1832-1898) and Salvador Dali (Spanish, 1904-1989)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Maecenas Press - Random House, 1969

18-1/2” x 13-1/4”

Milo Baughman for Thayer Coggin “Giant Swivel Chair”

1970s, strie velvet h. 26”, w. 41”, d. 41”

Charles Kvapil (French, Belgian, 1884-1957)

“Bouquet de Pavots” oil on canvas 19-1/4” x 22-1/2”

Milo Baughman for Thayer Coggin “Giant Swivel Chair”

1970s, strie velvet h. 26”, w. 41”, d. 41”

Charles Kvapil (French, Belgian, 1884-1957)

“Bouquet de Pavots” oil on canvas 19-1/4” x 22-1/2”

John Tarrell Scott (American/Louisiana, 1940-2007)

John Tarrell Scott (American/Louisiana, 1940-2007)