Shang to Qing

7 - 21 Jul 2025

Camden Park, Singapore

Viewing by Appointment Only

Contact: gallery@nikkofineart.com

Foreword

This inaugural special exhibition and sale represents a year of contemplation and meticulous selection.

The six objects featured span an extraordinary timeline, from approximately 1250 BC to 1800 AD, lending to the title Shang to Qing. This sale also marks a milestone for us: the release of our first catalogue.

In the online publication, where we can, we have attached links to the section on similar examples, for ease of reference.

Considerable time and effort have been devoted to this undertaking, and we are thrilled to share it with you.

We hope you take great pleasure in the works of art we have chosen.

Catalogue

A Bronze Dagger (Ge)

Late Shang Dynasty, Anyang Period (13th – 11th Century B.C.)

The base of the tapered blade adorned on both sides with high relief casting of a cicada motif. The haft of the blade intricately engraved with an intaglio design of a taotie mask, mirrored on both sides.

Encrusted in a richly textured green patina, interspersed with areas of brownish-red cuprite.

Provenance: Stephen Junkunc III Collection

Similar examples:

Sotheby’s A Journey Through China's History. The Dr Wou Kiuan Collection Online. Part I, Lot 54

The Collection of The British Museum, Registration Number 1940,1214.282

Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art, Accession Number S2012.9.600

The taotie is one of the most mysterious and iconic motifs in Chinese bronzes, characterized by a frontal, bilaterally symmetrical zoomorphic mask. Its design is thought to derive from jade pieces bearing “monster masks” found at Neolithic sites belonging to the Liangzhu culture (3310 - 2250 B.C.)

The taotie is first mentioned in relation to bronzes in Lushi Chunqiu, an encyclopaedic Chinese classical text, compiled in 239 B.C. under the patronage of Lu Buwei, prime minister of the state of Qin. The scholar describes laying eyes on a Zhou period Ding bearing a taotie mask, describing the taotie as such; the taotie has a head but no body, it devours people without swallowing, and therefore suffocates on itself, a retribution for its evildoing. The taotie may have served as a cautionary warning against avarice.

The function of the motif has been variously interpreted: it may have been totemic, protective, or an abstracted, symbolic representation of the forces of nature.

A Bronze Dragon Mount

Zhou Dynasty, Zeng State

Late Spring and Autumn Period – Early Warring States Period (5th Century B.C.)

A bronze mount stylised in the form of a dragon head, the mount is open and undecorated at the back, where it was likely affixed to the framework of a Bianqing. Finely interlaced low relief patterns of serpent-like creatures on the top and sides of the mount.

Individual distinctive elements, including the piercing eyes, upturned nose, exposed fangs, and jaw are embellished with intricate engraving

Provenance: Ben Janssens Oriental Art, London

Published: Mythical Animals - Asian Art in London 2019

Similar examples:

The sole closely related example known to us is the set of mounts on the bianqing excavated from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, now housed in the Hubei Provincial Museum

Christies: The Sze Yuan Tang Archaic Bronzes from the Anthony Hardy Collection, Lot 844 (Chu State)

Zeng

A state forgotten over time, and perhaps deliberately omitted from historical record following its conquest by the Zhou

The extraordinary assemblage of 6239 bronze wares, discovered in the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng dating to the 5th century in 1978, constitutes one of the largest known finds from China’s Bronze Age. Since then, further archaeological discoveries have shed more light on this mysterious state.

A vassal state of the Zhou dynasty whose central authority ruled from the Yellow River basin to the north. The Zeng flourished along the middle reaches of the Yangzi River, a region rich in minerals.

Inscriptions on a set of bronze vessels unearthed at Sujialong, Jingshan in 2016, attest that one of Zeng’s principal duties was the protection of the so-called “Road of Copper and Tin,” a major trade route facilitating the transport of such mineral resources essential to the casting of bronze objects for both ceremonial and martial use.

Once assumed to be subordinate to Chu, the Zeng have emerged as a formidable state in their own right, further discoveries at sites like Yejiashan and Wenfengta suggest that Zeng lords were descended from Zhou royal lineage, entrusted with governance along the empire’s southern frontier.

These findings attest to Zeng’s privileged access to metallurgical resources, its technical sophistication in bronze casting, and its strategic importance in consolidating Zhou authority across the southern reaches of the realm.

These discoveries continue to reshape scholarly understanding, positioning Zeng not as a cultural satellite of Chu, but as a distinct and influential state whose material legacy compels a reevaluation of early southern Chinese statehood.

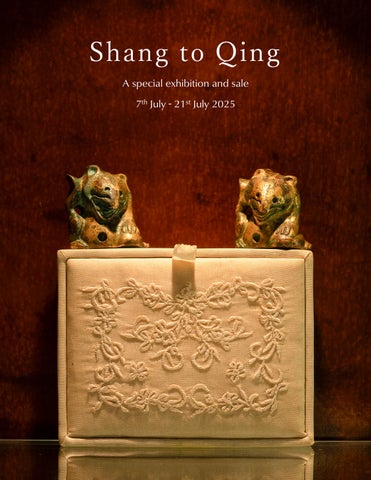

Two Gilt-Bronze Bear Supports

Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 220 A.D.)

Each bear cast half-crouched, belly flanked by folded hind legs tucked on its side, the body upright with its clawed left forepaw resting on its haunch, right forepaw raised upwards in a lifting motion. The head encircled with delicately incised markings depicting a mane. Head cocked to the left with jaws agape revealing a fierce display of teeth.

Much of the rich gilt remaining.

Provenance: Kwok Gallery

A Private Collection, Singapore

Similar examples:

Sotheby's Chinese Art Online: A Private Asian Collection 2023, Lot 3010

Bonhams Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art 2013, Lot 542

Animal-form supports of this type were made to serve as supports for vessels such as lian, zun or pan; for example, see a Han dynasty gilt-bronze vessel (lian) with crouching bear supports preserved in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, accession no. S1987.341a-b.

The posture of strength and vigilance symbolises the bear as a guardian, displaying an expressive fierceness intended to protect the vessel it once supported. Such bear supports, with their combination of realism and stylized design, highlight the skill of Han Dynasty artisans in crafting objects that were both both functional and deeply symbolic, embodying protective qualities within a visually compelling form.

An Incised Qingbai Dish

Southern Song Dynasty (1127 – 1279 A. D.)

Finely and thinly potted, supported on a straight, short ringed foot, the thinly potted flaring sides rising to a six-lobed foliate rim, a raised line of slip separating each petal. The interior masterfully incised with a peony flower and foliage.

Glazed overall in an exquisite translucent pale blue.

Provenance: An English Private Collection

Similar examples:

Bonhams Cornette de Saint Cyr: Chinese Art Lot 34

Sotheby’s CHINA/5000 YEARS Lot 502

A Longquan Celadon Brushwasher

Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368 A. D.)

Shaped in the form of a wooden basin, the exterior with gently rounded flaring sides divided into rounded segments joined by a raised band encircling the form. The interior of the brushwasher rising from a broad flat base to a scalloped rim.

Glazed overall in a lustrous sea-green glaze with prominent crackling and crazing. The glaze continues over the wedge-shaped foot, enclosing the recessed underside with only a small splash of glaze at the centre, the unglazed grey stoneware on the underside fired reddish brown.

Provenance: A Private Collection, Japan

Similar examples:

J. J. Lally & Co. Oriental Art, Song Dynasty Ceramics: The Ronald W. Longsdorf Collection, Number 9

The Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Accession Number: 16.156.2

An Iron Rust (Tiexiuhua) Vase

Qing Dynasty, Qianlong period (18th Century)

The vase superbly potted in an elegant pear shape, tapering gracefully to a high waisted neck with gently everted rim, supported on a firm waisted foot, proportionate throughout.

The entire vessel save the foot ring, glazed in a rich and lustrous reddish brown ‘iron’ glaze.

Provenance: Dr. Franklin Preiser Collection

Similar examples:

Bonhams: Chinese Art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Iron rust glaze was first innovated during the reign of the Yongzheng emperor and came into prominence during the reign of the Qianlong emperor; the glaze was designed to emulate the patinated appearance of archaic bronze. See Peter Y. K. Lam, Shimmering Colours: Monochromes of the Yuan to Qing Periods, Hong Kong, 2005, p.243.

The metallic rust effect results from a rich glaze consisting of iron and manganese being allowed to cool down slowly, which leads to iron, or oil, spots pooling on the surface.

The production of such a glaze reflects the refined tastes of the Qianlong emperor who had such an appreciation for antiquity and classical aesthetics.