Spatial Intimacy

Intimate spaces spawn deeper feelings of intimacy and comfort, as opposed to the lack of control and sense of direction that comes from open internal layouts and spaces. The open plan typology has dramatically altered how we occupy and engage with architecture and self. Following technological advancements and innovations that have enabled the development of structures and ideologies, the growing trend of freeing the plan from its interior walls and boundaries relinquishes any sense of being and architectural identity. In considering the role of open plans as an economic and social response to maximise efficiency for

spatial and functional arrangements and requirements, how much does this very decision detract from the way in which the active user experiences space – or one room from another? Where are we to dwell in the abyss? Open plans convey almost an unnerving, uncanny sense of spatial infinity and comfortability. Order must be restored – to do so, defined boundaries should be reintroduced into the architectural discourse through well-articulated applications of permeable surfaces. As a result this begins to inform the generation of thresholds that operate and coincide with adjacent spaces, establishing a more distinguishable

relationship between architecture and its observers. Therefore, architecture can be better understood and digested, as it embodies a deeper architectural identity when defined boundaries and thresholds are established.

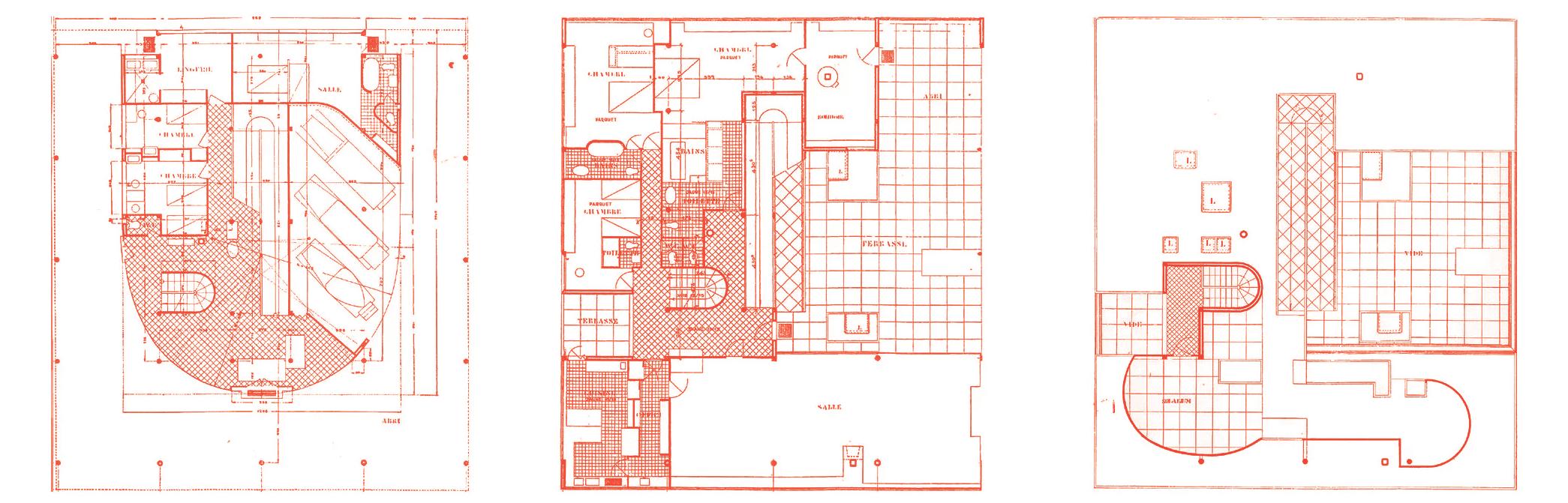

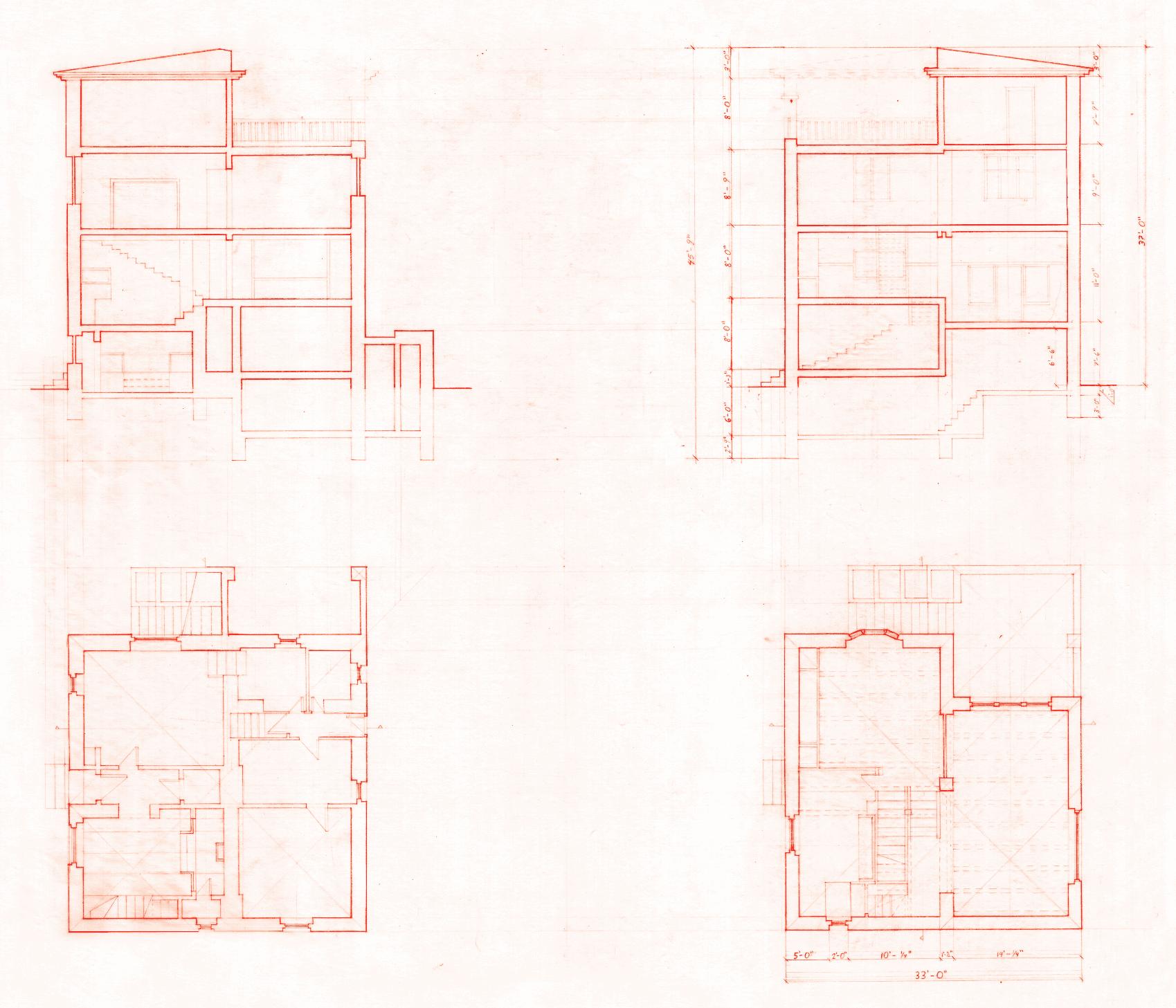

[2] Plans of Villa Savoye / Le Corbusier (Drawing courtesy of Foundation Le Corbusier ©)

It becomes evident through a logistical grid layout that spatial arrangements, whilst conveying spatial order, appears more as an afterthought - internal programmes are fitted within the series of pilotis, therefore enforcing the idea that the human experience of space is not considered in Le Corbusier’s design ethos.

The Sixth Point of Architec -

If you were to consider the impact of Le Corbusier’s contribution to the modern architectural discourse, the integration of key architectural elements (notably his Five Points of Architecture) aided the breakthrough for tectonic expression and spatial efficiency. Perceptions surrounding early 20th century architecture has shifted, as did the structural capabilities and requirements for buildings had taken advantage of ordered columns to relinquish the floor plan from structural demands. Non load-bearing walls had become a dominating innovation for delineating spaces and functions, greatly expanding

the opportunities for physical occupation. Evidently, Le Corbusier presents a new wave of economised architecture to improve quality of life. Villa Savoye, considered an “icon of modernism,”1 presents as a spatially dynamic ensemble that enables occupants to dwell freely – given free rein to navigate without prescribed paths. Unpacking this design ethos, a key ingredient is missing from the forefront (perhaps, the Sixth Point of Architecture) - the human experience of space. Reviewing the spatial arrangement of Villa Savoye, one must question what direction the subject must take to access the stairwell thats set freely in the centre of the room. Although permeable walls are present in plan, actively and literally defining exterior and interior zones, the structural grid of columns depicts the beginnings of spatial delineations which abruptly reaches a brick wall (how ironic). This structural grid stipulates a series of invisible barriers which informs little to no guidance for navigation – while the columns achieve their structural purpose for relieving the plan from spatial definitions, they have subsequently deteriorated the existence of clear boundaries, becoming more physically and emotionally digestible. Although implied, these ‘boundaries’ are disregarded, creating a spatial void of sorts that the user gets lost within – like navigating freely without a

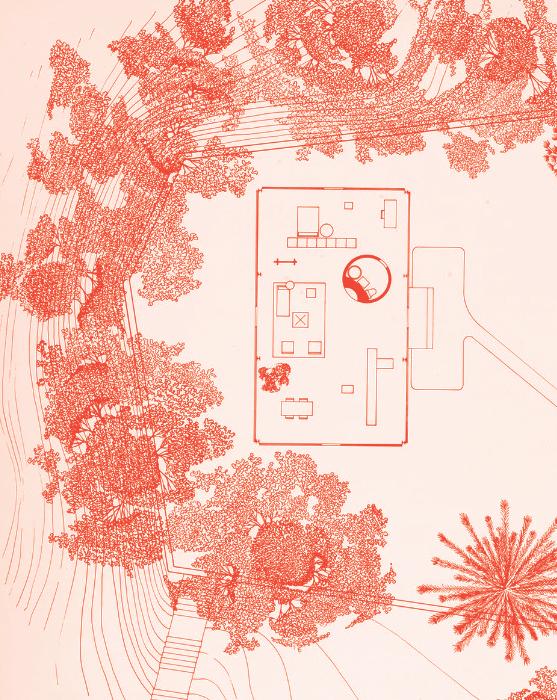

[3] Plan of Glass House / Philip Johnson (Drawing courtesy of Philip Johnson ©)

Spatial definition is minimal, with only the bathroom physically separated from the remaining programmes that are merged into one. This results in an overwhelming range of possibilities for circulation which rejects spatial definition and intimacy.

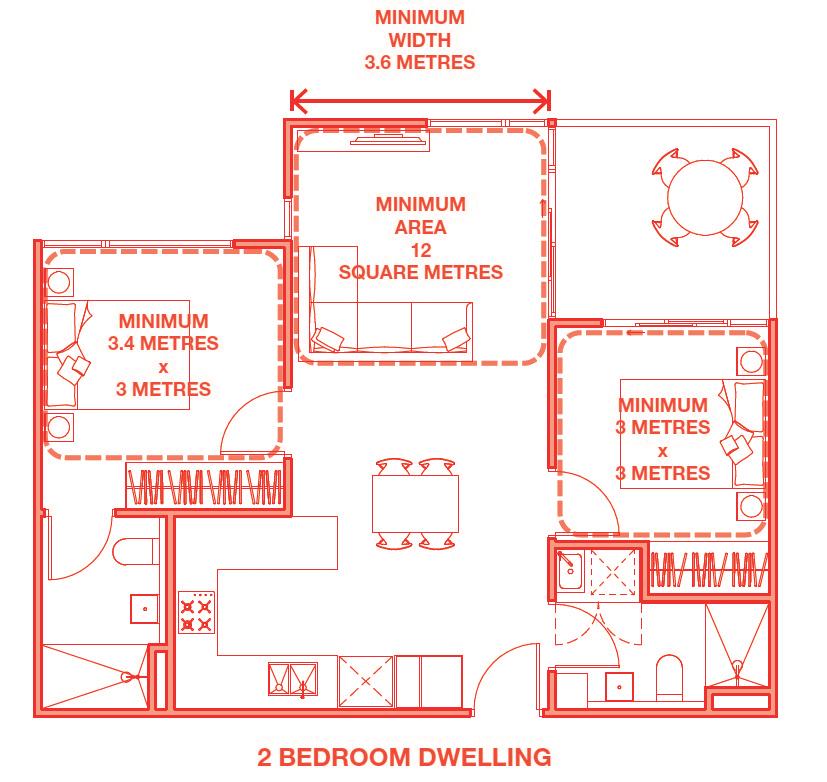

[4] Plan diagram from Apartment Design Guidelines for Victoria (Diagram courtesy of the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning) (Overlay by Nick Bizzarri)

With privatised spaces isolated by physical wall boundaries, the remaining communal space (indicated) merges into one roomfurniture arrangements determined by occupants would enable spatial differentiation, further emphasising lack of architectural identity

map. Therefore, there becomes a lacking architectural identity which can inform the user’s experience and emotional attachments with different spaces. Philip Johnson pushes these sentiments towards spatial and experiential deterioration even further with his Glass House project, which magically crams the primary functions of a house into one room. It is almost ironic: architecturally, the structural grid creates acceptable order, but results in a completely unorganised and overwhelming spatial arrangement (down to the central location of the physically separated bathroom).

Consider the spatial arrangement of a typical urban apartment. An open-plan design is almost always integrated to maximise efficiency of space – in addition to its costefficient leveraging on air circulation and natural lighting. While the elimination of internal walls has improved the circulation between spaces (through combination of programmes) and somewhat resolves the complexities of high-density housing, any sense of architectural identity is lost - the occupant, in return, becomes emotionally disconnected. Contemporary architecture has fallen victim to spatial disorder – thresholds between programmes have dissolved, leading you to wonder where the kitchen ends and the living room begins. Victoria’s

Apartment Design Guidelines stipulates the spatial requirements to achieve a functional floor plan, however continues this standard of grouping the kitchen, dining and living room as one; these standards following the same notation that spaces should be designed with consideration of “realistically scaled furniture and circulation.”2 While the architect is the provider of parameters (in this case, boundaries which differentiate one apartment from the other, as well as private rooms from communal ones), the rest is left up to the occupants to define – almost like giving the fresh intern work they aren’t qualified to do.

Functions and the experience of space come to fruition when boundaries are established. Without them, the subject is swallowed into an architectural abyss. Starkly contrasting the liberation of space explored by Le Corbusier and Johnson, Adolf Loos positions his ethos on the opposite side of the spectrum, strictly considering the experiential prosperity that comes from spatial adjacencies. Designing spaces in a manner that considers how they can drive an emotional interrelationship between subject and object. Through precise articulations of space, Loos effectively considers what Le Corbusier hadn’t in his structural innovations – how spaces could be manipulated and arranged to inform a deeper sense of feeling and intimacy. Varying

scales, ceiling heights and floor changes play an important role in this design ethos, as well as enunciating an architectural identity that can be easily understood.3 In such works as Rufer House and Muller House, there is an overwhelming sense of spatial order and coherence – the catergorisation of programmes determined by permeable boundaries and thresholds across horizontal and vertical planes creates a more digestible place to navigate and dwell in.

“My work does not really have a ground floor, first floor or basement. It only has connected rooms, annexes, terraces. Each room requires a particular height… The rooms must then be connected in such a way as to make the transition imperceptible, and to effect it in a natural and efficient fashion...”4

- Adolf Loos

[5] Plan and Section drawings of Rufer House / Adolf Loos (Drawings courtesy of Christy Mihalenko) (Overlays by Nick Bizzarri)

Plan overlays used to indicate threshold zones, primarily hallways and stairs which differentiate programmes horizontally and vertically. Section overlays further emphasise spatial order and defined catergorisation by illustrating the variety of programmes that occur - separated by walls and changing floor/ceiling heights.

In essence, there is a more architecturally refined outcome that stems from Loos’ Raumplan theory – one that challenges contemporary practices that favour dynamic spatial and functional arrangements. Space can be utilised as a tool for manipulating “sensual emotionality,”5 echoing Gaston Bachelard’s complex understanding of the house as one holistic image made up from a series of fragmented images.6

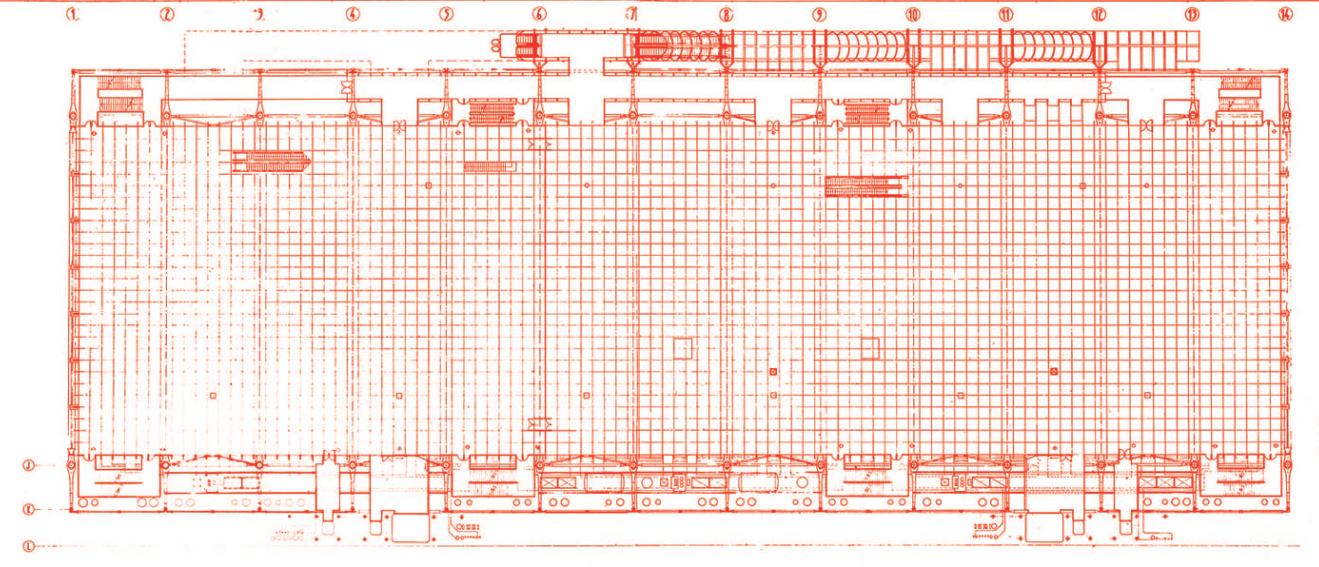

Spatial efficiency has overruled an emotional sense of place and being within architecture – contemporary architecture leaning more towards the representation of universal spaces that occupy multiple meanings that clash and collide into each other (e.g.. Johnson’s Glass House Project). This concept shares the same sentiment with a congested highway or bustling food court. Applying this thought within the architectural discourse, we begin to reveal the disorder within the order of the Centre Pompidou’s bustling internal spatial arrangements. Emulating Le Corbusier’s tectonic expression in the public domain, the separation of structure from the interior has brought forth a wave of possibilities for spatial interaction and the development of emotionality. Not to mention the overwhelmingly congested facade, what lies beneath is no different. The active participant becomes paralysed in a state of

shock and anxiety as they try to navigate the spatial disorder. Unlike Loos’ volumetric differentiation and definition of orderly spatial adjacencies, the quality of space defined by static ceiling heights, invisible boundaries and sprawled functional agencies is further impacted by human behaviours. In the context of public architecture, there is an underlying “possessiveness of space”7 where occupants will dissolve spatially, leading to an immeasurable amount of self-defined thresholds for navigation – breaking the cycle and interrupting the connection between architecture and the observers.

[6] Plan

Nick Bizzarri)

[7]

Nick Bizzarri)

The vastness of space (illustrated in plan) achieved from the orderly distribution of structural elements (illustrated in section) has resulted a multifunctional, adaptable hell that gives too much power towards the curation of spaces for programmes. The lack of internal spatial permanence leaves the public to navigate freely inviting social over-stimulation. Overlays (right) interchangeable zones defined by isolated boundaries.

Order and Intimacy

“What is more beautiful than a road.”8

- George Sand

One might consider the difference between the hybrid worker who chooses to work from home vs. working from an office. Working externally involves navigation to a set destination via a prescribed path – the process of continuity serving as a navigation through a series of thresholds which subconsciously prepare the worker before commencing their next daily activity. The

path between A and B becomes a powerful tool in defining and strengthening the human experience of space – to refer back to my previous argument on open-plan apartment layouts, the path from the bedroom to the desk is far less dramatic yet hinders the psyche. Bachelard alludes to this idea of valuing the threshold space, as integral to enhancing functional arrangements.9 The in-between space; the meaningful void; the puppeteer whose strings playfully tie two spaces together – a defined threshold can inform an emotional and experiential transition into the next functional zone. Leveraging off this concept, Tim Boettger believes that a threshold space “is strongly determined not only by tension-building counterbalances but also by the sequence in which space is experienced.”10 Subject and object work concurrently to develop an experiential synergy – without delineated boundaries, the sentient human becomes lost.

Loos successfully achieves this outcome (e.g. Rufer House, Muller House) through his arrangement of functions physically separated by thresholds which are defined by alternating floor/ceiling heights and wall/ window boundaries – by navigating through zones, the occupant is able to leave one series of thoughts and feelings behind in one room and gain a new one in another. This is not

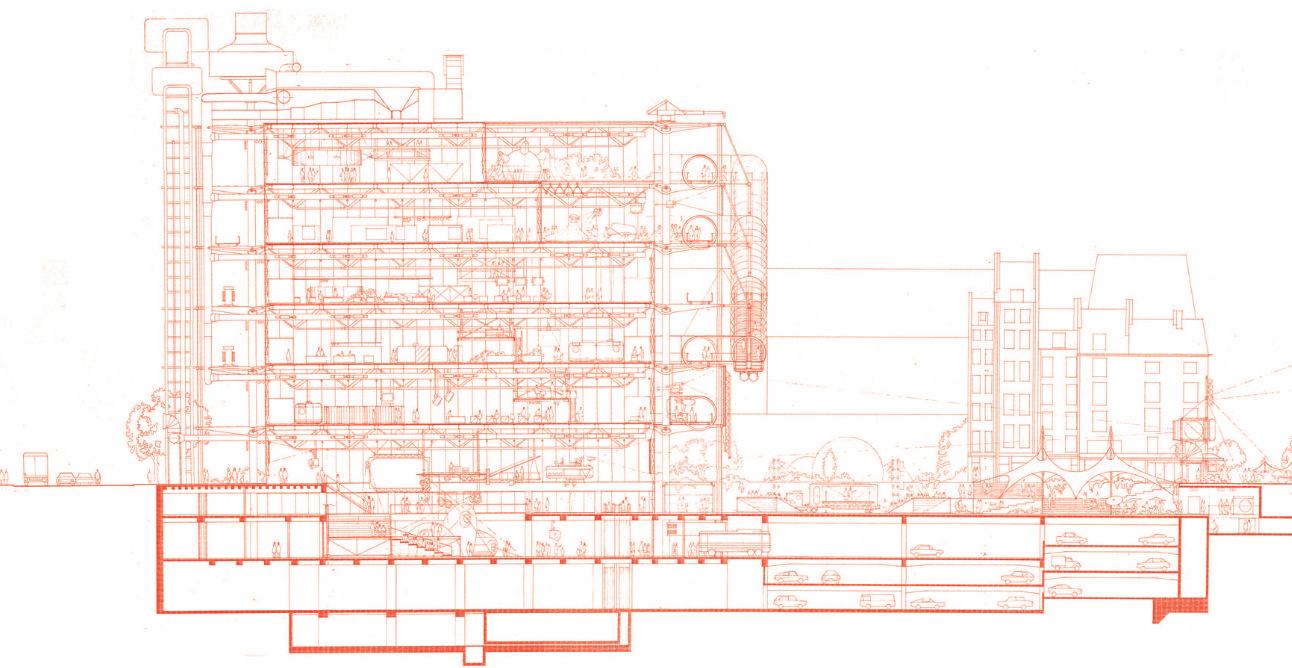

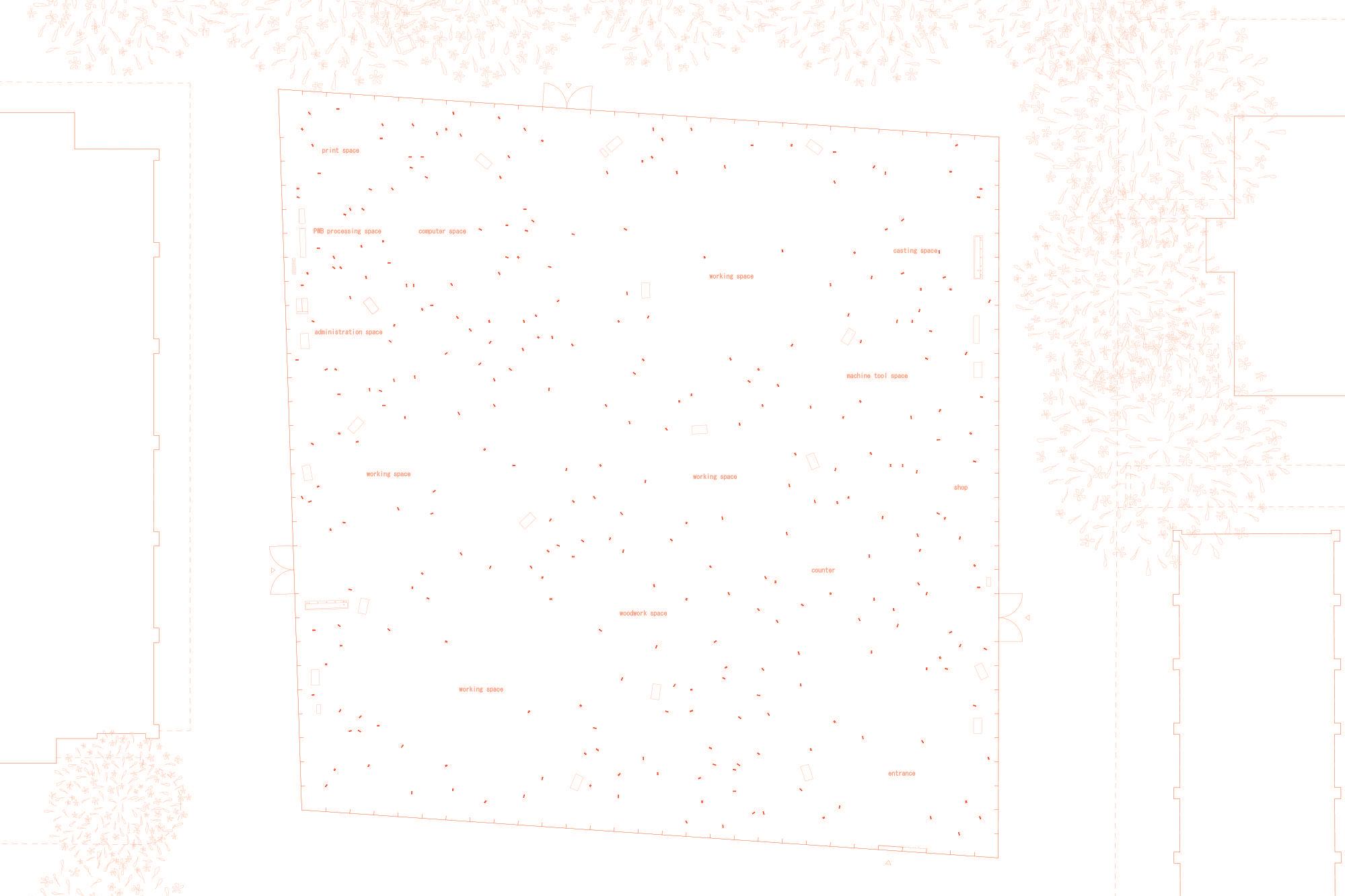

[8] Kanagawa Institute of Technology KAIT Workshop / Junya Ishigami and Associates (Drawing courtesy of Junya Ishigami + Associates ©)

[9] Plan of Kanagawa Institute of Technology KAIT Workshop / Junya Ishigami and Associates (Drawing courtesy of Junya Ishigami + Associates ©) (Overlays by Nick Bizzarri)

The plan illustrates a complete spatial disarray - assumed spatial zoning based on the location of columns eliminates the presence of thresholds, causing collisions in behaviour-driven circulation spaces.

the case with Junya Ishigami’s Kanagawa Institute of Technology Workshop, which completely obliterates the formality, rationality and existence of thresholds (what would happen if Le Corbusier took psychedelics). A spatial nightmare that relinquishes control, leaving the occupants to wander and clash together like ants. It could be argued that the positioning of columns can also inform a sort of invisible set of boundaries which informs different functions and thresholds. But it’s one room! That anyone can navigate through freely! It’s one room that just keeps going. This abstract design approach brings chaos without any clarity of functional zoning – no matter how cost efficient and economically sustainable the design may be.

“It is the quality of the transitions between spatial boundaries that are crucial; often they are a source of anxiety because they are ambiguous...”11

- Roderick J. Lawrence [on thresholds]

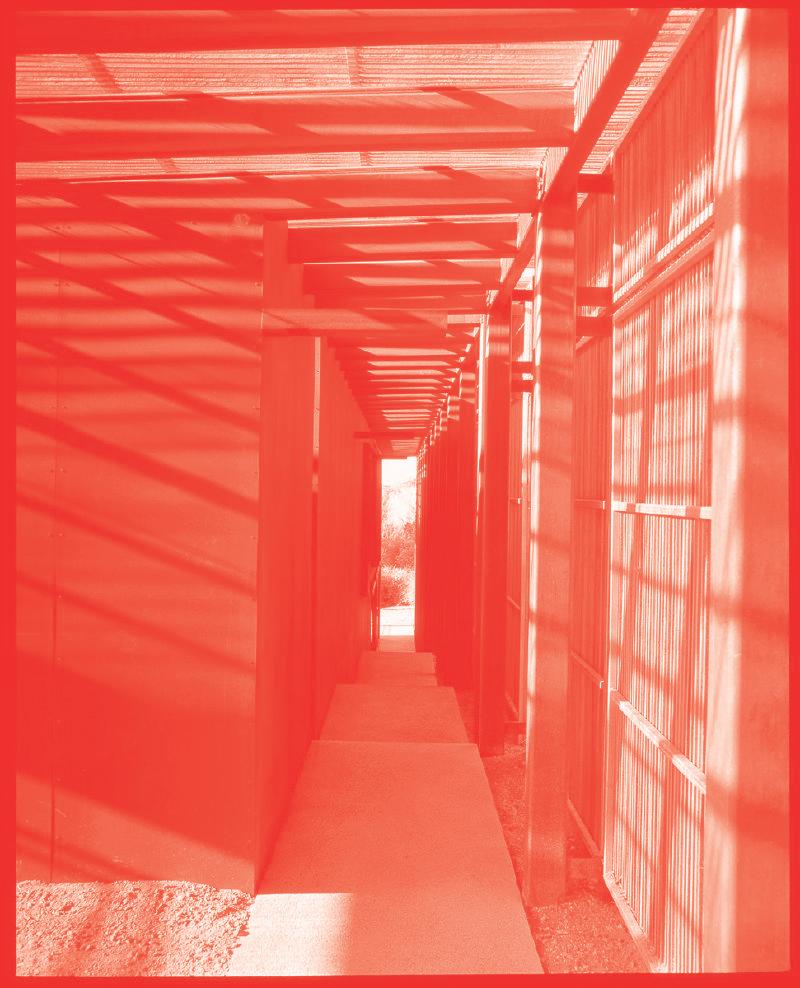

Spatial catergorisation can successfully create order and comfort, and it is this continuity of functional arrangements that creates a more physically and emotionally digestible navigation through space. A clear threshold (or series of thresholds) begins to inform the overall success of a building and its ability to establish a gradient between the interior and exterior – as well as adjacent internal zones. In traditional Japanese residential architecture, the entryway (genkan) demarcates an in-between threshold. Hats and shoes are removed and replaced with slippers, officially establishing a transition from formal to informal; a transition into domestic comfort.12 In Sean Godsell’s Peninsula House, the entryway threshold is manipulated with the implementation of a centralised hallway that travels through the building towards the primary gathering spaces. For more private spaces, isolated hallways and stairwells are integrated for appropriate transitions. Holistically, with each zone relatively associated on different planes, circulation requires movement across floors and through changing scales of space for the occupants to resituate themselves within the house.

A systematic approach to spatial and functional arrangements creates a more successful outcomes in architectural design.

Subject and object are interlocked in a binding relationship that blends together to construct a clear sense of being. What would architecture be without the observer? It is important to consider the observer when fabricating a series of spaces and functions for occupation. The lack of boundaries and thresholds that are prominently evident in open-plan designs retract any physical and emotional connections to architecture, spaces and self. How are we meant to organise our thoughts when the arrangement of spaces are not organised?

Illustrating the entryway as a key threshold space for physical, emotional and social transition as entry into a household becomes more privatised.

[11-13] Photos of Peninsula House / Sean Godsell Architects (Photos courtesy of Earl Carter ©)

Evidence of changing ceiling heights and floor levels - architectural elements which enhance a transition from one space to another. Word Count: 1936

References Images Notes

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2014.

Bardeesi, Talal M. Noor. “Optimizing Dwelling Transitional Space”. Ekistics 59, no. 354/355 (Greece: Athens Centre of Ekistics, 1992): 206-16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43622250

Baudrillard, Jean. “The Beaubourg Effect: Implosion and Deterrence.” In Simulacra and Simulation. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Boettger, Till. Threshold Spaces: Transitions in Architecture. Analysis and Design Tools. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783038214007

Jara, Cynthia. “Adolf Loos’s ‘Raumplan’ Theory.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol.48, no. 3 (United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis, Ltd: 1995): 185-201. https://doi. org/10.2307/1425353.

Lawrence, Roderick J. “Transition Spaces and Dwelling Design.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 1, no. 4 (Chicago: Locke Science Publishing Company Inc., 1984): 261-71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43028706

Long, Christopher. “Raumplan and Movement.” In The New Space: Movement and Experience in Viennese Modern Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017. https:// doi.org/10.12987/9780300223927

Robinson, Jenefer. “On Being Moved by Architecture.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 70, no. 4 (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2012): 337-53. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/43496529.

1 Jenefer Robinson, “On Being Moved by Architecture,” in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 70 , no. 4 (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2012), 349.

2 Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, “Apartment Design Guidelines for Victoria,” Victoria State Government, accessed 11 November 2024, https://www. planning.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/631509/ApartmentDesign-Guidelines-for-Victoria.pdf

3 Cynthia Jara, “Adolf Loos’s ‘Raumplan’ Theory,” in Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol. 48, no. 3 (United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis Ltd, 1995), 186.

4 Jara, “Adolf Loos’s ‘Raumplan’ Theory,” 186.

5 Christopher Long, “Raumplan and Movement,” in The New Space: Movement and Experience in Viennese Modern Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 63.

6 Gaston Bachelard, “The House. From Cellar to Garret. The Significance of the Hut,” in The Poetics of Space (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2014), 3.

7 Talal M. Noor Bardeesi, “Optimizing Dwelling Transitional Space,” in Ekistics 59, no. 354/355 (Greece: Athens Centre of Ekistics, 1992), 206.

8 Bachelard, “The Poetics of Space,” 11.

9 Bachelard, “The Poetics of Space,” 11.

10 Tim Boettger, “Introduction,” in Threshold Spaces: Transitions in Architecture. Analysis and Design Tools (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2014), 13.

11 Roderick J. Lawrence, “Transition Spaces and Dwelling Design,” in Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 1, no. 4 (Chicago: Locke Science Publishing Company Inc., 1984), 263.

12 Roderick, “Transition Spaces,” 265.

[1] ArchEyes. Villa Savoye Staircase. ArchEyes | Timeless Architecture. https://archeyes.com/the-villa-savoye-le-corbusier/

[2] Foundation Le Corbusier. Floor Plans. ArchEyes. https:// archeyes.com/the-villa-savoye-le-corbusier/

[3] Philip Johnson. Floor Plan. ArchEyes. https://archeyes.com/ philip-johnsons-glass-house-an-icon-of-international-stylearchitecture/

[4] Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. Dwelling Amenity. In Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. “Apartment Design Guidelines for Victoria,” 115. Victoria State Government, accessed 11 November 2024.

[5] Mihalenko, Christy. Rufer House Plans. Wordpress. https:// christymihalenko.wordpress.com/2013/06/18/the-rufer-house/

[6] Studio Piano and Rogers, Fondazione Renzo Piano. Plan. Archello. https://archello.com/project/centre-pompidou

[7] Studio Piano and Rogers, Fondazione Renzo Piano. Section. Archello. https://archello.com/project/centre-pompidou

[8] Junya Ishigami + Associates. Render. Divisare. https://divisare. com/projects/259825-junya-ishigami-associates-kanagawa-instituteof-technology-kait-workshop

[9] Junya Ishigami + Associates. Floor Plan. Divisare. https:// divisare.com/projects/259825-junya-ishigami-associates-kanagawainstitute-of-technology-kait-workshop

[10] Diagram by author

[11-13] Carter, Earl. Photographs of Peninsula House. Divisare. https://divisare.com/projects/236084-sean-godsell-architects-earlcarter-peninsula-house