Nudging

Nudging refers to the occourance of subtle guidance of peoples behaviours in a particular direction without overt coercion.

The peacewalls can be seen as a form of environmental nudge that reinforces social divisions between catholic and protestant communities, the mere existance of the wall acts as a gentle nudge that perpetuates the seperation of neighbourhoods and discourages interaction between the two groups.

The walls make it less likely for people to cross from one side to the other, as they symbolize a boundary that signals safety, territoriality, and often hostility between groups. Even if there are gates/walk ways, the walls nudges residents to stay wihtin their own communities therefore reinforcing patterns of avoidance and segregation

Territoriality

The theory of territoriality in environmental psychology suggests that people establish and defend boundaries in their physical spaces to maintain a sense of ownership, control, and identity.

The walls represent territorial markers, defining the limits of each community’s space and reinforcing a sense of identity and belonging within those territories. The physical presence of the walls provides a sense of security for each group, as the walls create a psychological and physical barrier that separates them from the perceived threat of the other community. This territorial defense fosters feelings of ownership over the space, which is strongly tied to the group’s political, cultural, and religious identity.

Furthermore, the walls encourage exclusionary behavior, where each community may see the other as an outsider, reinforcing ingroup/ outgroup dynamics. The presence of the walls primes people to adhere to their community’s norms and protect their territorial boundaries from outside influence. This territoriality also leads to a resistance to change, as the walls have become deeply entrenched in the communities’ identities, with fears that removing them could invite conflict or loss of control

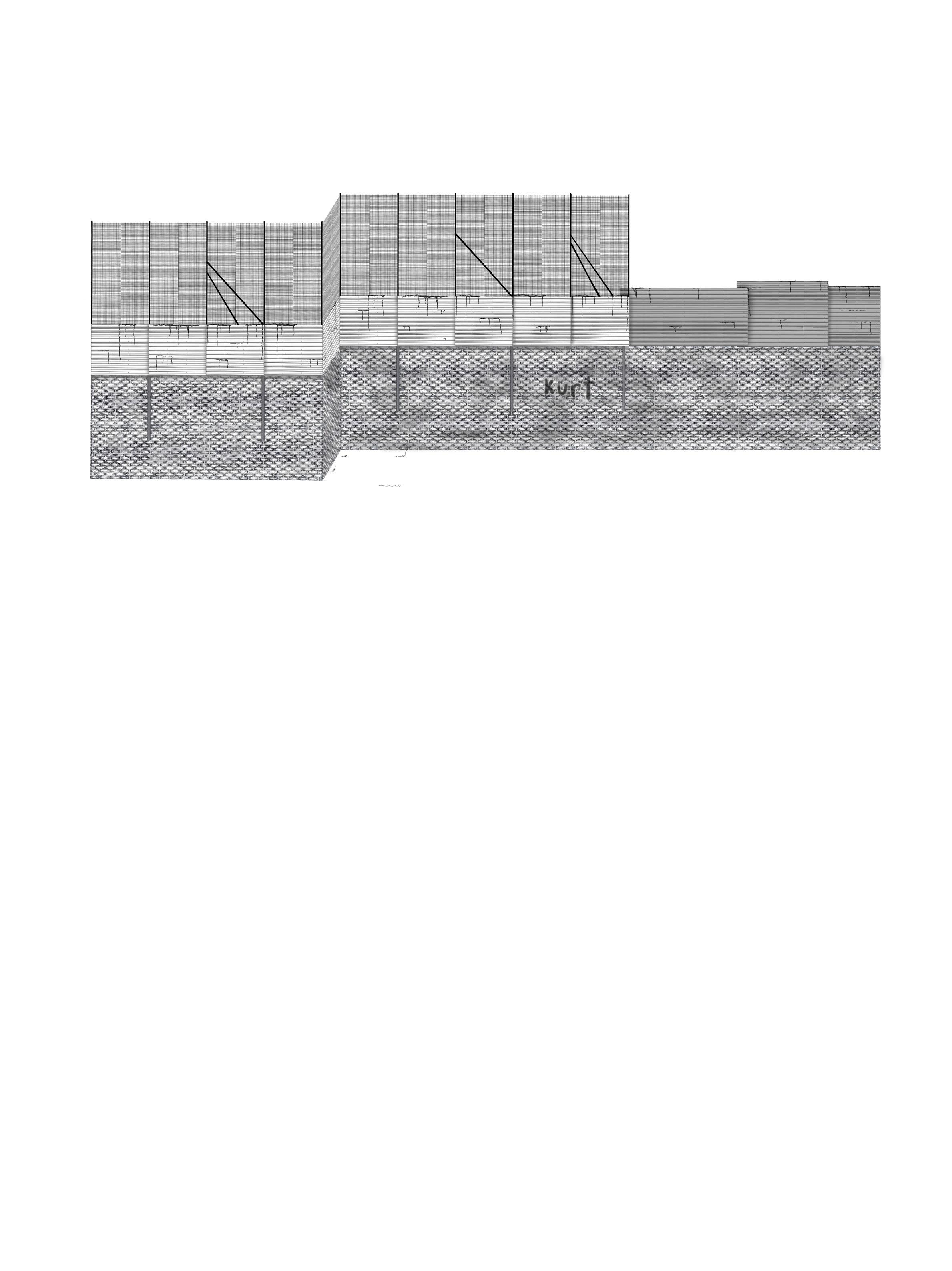

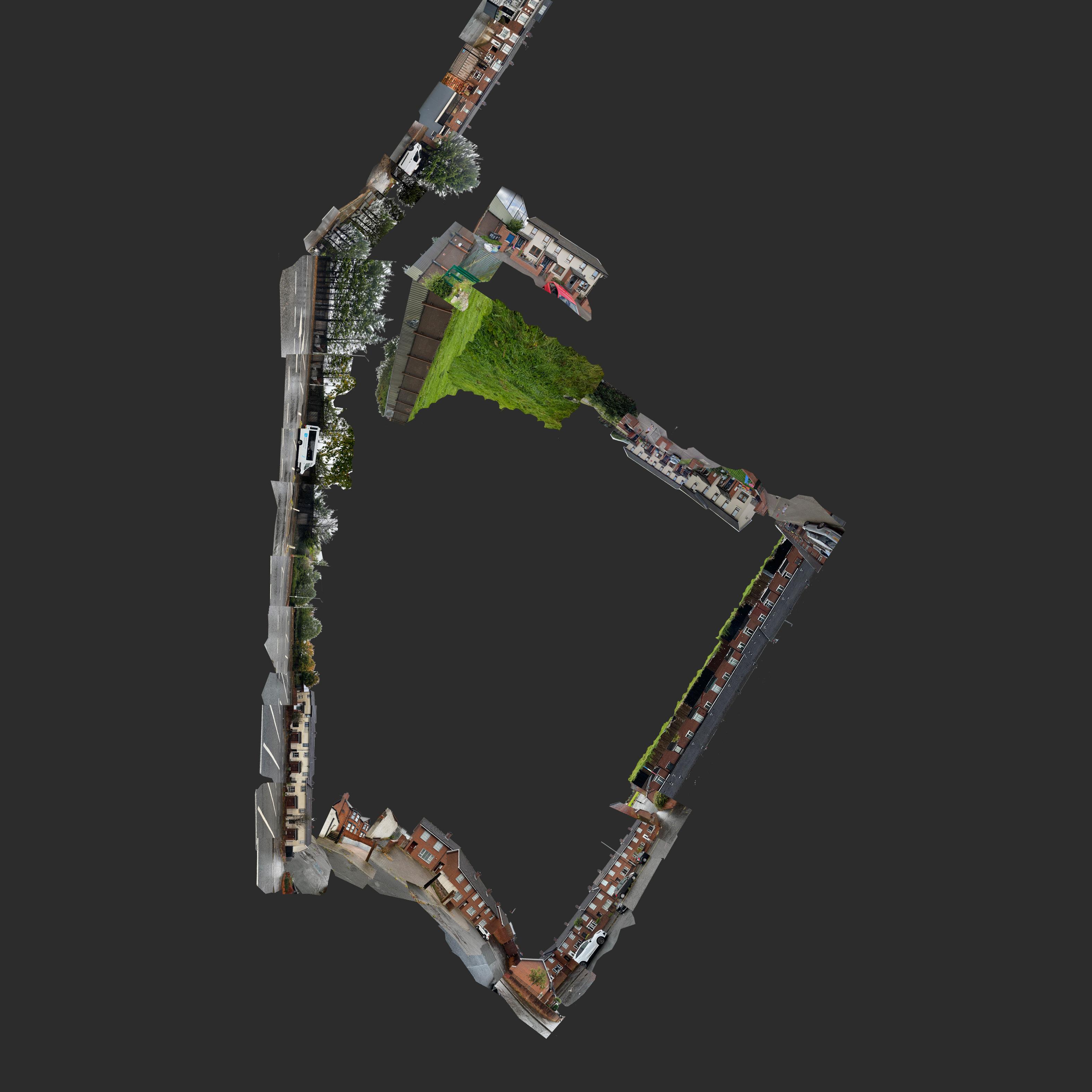

The division created by the peacewalls imppacts those that live along side it everyday. It affects how they live their lives, their mobility and how they interact with those who live on the otherside of the wall. Almost 30 years after the troubles ended, local residents are still conciously and sub consciously dealing with the repercussions of it. For many residents, the wall inconveninces their daily lives by forcing them to take longer routes to access buildings/people who may just be a couple meters away on the other side of the wall. In Cliftonville and Lower Old park there are many instnaces where this occours as the peacewall create a physical division between the communites therefore resulting in people who may only live a meter away, never crossing paths/ integrating, therefore contributing to the social and political unrest, and the lack of progressiion in this area

27 Mountview St ~ 2 Rosapenna St

Physcial distance: 10m

Walking distance: 482m

318 Crumlin Rd ~ 62 Rosehead St

Physcial distance: 15m

Walking distance: 1287m

8 Antigua St ~ 18 Rosehead St

Physcial distance: 4m

Walking distance: 321m

In the book Discipline and Punish, by michael foucault, he examines how spatial arrangements such as prisons, surveillance systems and architectural structures can discipline and regulate behaviour therefore fuctioning as a tool for social control. The peacewalls in Cliftonville/ Lower Old park act as a spatial barrier that regulates behavious and interactions between communities. They create physical and psycological seperation, therefore enforcing the idea that communities should remain seperated. This is not only a structure to seperate residents physically, but alos psychologically.

Michael Foucault

Identity and memory

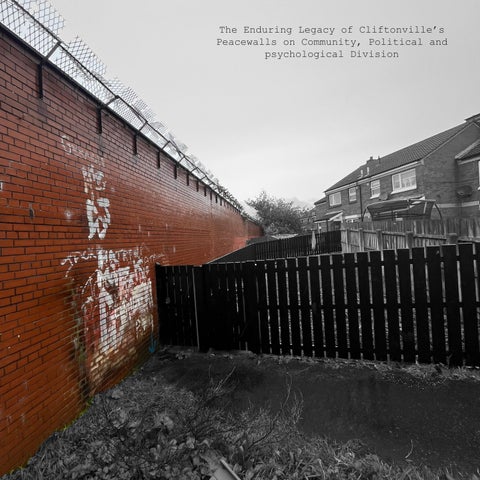

psychogeography places a great deal of importance on how space is experienced emotionally and how it is tied to historical memory. The peace walls were errected in the midst of a violent conflict and their continued existance serves as an enduring reminder of the sectarian tensions that shaped cliftonvilles/ Low Old Parks history.

This collective memory is often embedded in the physicalal space itself, therefore the walls act as a visual cue of the “need” for speeration.

Social Control

The peace walls can be viewed as a physcial manifestation of political decisions used as a tool for social control. They dont just physically seperate, they also control behaviour by structuring social interactions and influencing how people percieve themsleves and eachother. When divisions become normalised through physical structures, it reinforces the belief that the social boundaries are not only real, but necessary in order to keep their community safe. People may internalise these boundaries as part of their daily behaviour, therefore reinforcing patterns of exclusion and avoidance between communities.

Environmental Cues and social behaviour

The peacewalls often restrict direct access to certain areas and over time people may develop avoidance behaviours due to this. People may choose routes that avoid contact with those from the other side, internalising a sense of territoriality and even when the physcial threat of violence is low, the psycological presence of the wall can create and atmosphere of suspicion or anxiety.

The power of presence

the constant physical prescence of the walls influence peoples behaviour by acting as a persistant reminder of the historical divisions and sectarian tensions. Even if the walls are not actively policed or patrolled, their mere existance implies that seperation is neccessary or atleast acknowledged as fact of life. They serve as a symbol of ongoing conflict and the mere presence often subliminaly shapes the way people from different communities interact. They subtly reinforce the idea of an “us vs them” mentality. Therefore people on either side of the wall may feel an implicit need to maintain a sense of boundaries or distance even if there are no imediate threats or active conflict. People may subconsciously avoid interaction wiht individuals from the other side of the wall, even when encountering them in neutral spaces such as schools, shops, workplaces. The walls are psycological cues guiding individuals on how to behave, who to trust and where to go.

Psycological Reinforcement of “Otherness”

In social psychology, the concept of othering plays a central role in how people define and relate to those who are seen as “different” from themselves. The peacewalls serve as physical manifestations of this social process, and serve as a constant reinforcement of the notion of the “other” and the idea that there is inherant deifferencesbetween the communities on either side contributing to the social identity theory where individuals define themselves/ their group by contrasting it wiht an “other” group. The falls foster a mindset that “outsiders” are a threat or at the very least not to be trusted, this psycological distancing helps solidify the distance between communities and cna reinforce exclusionary behavious such as avoiding social interaction, intermarriage or collaborative efforts across community lines aswell as increasing the likelyhood of sectarian crime/ antisocial behaviour.

The future of the walls

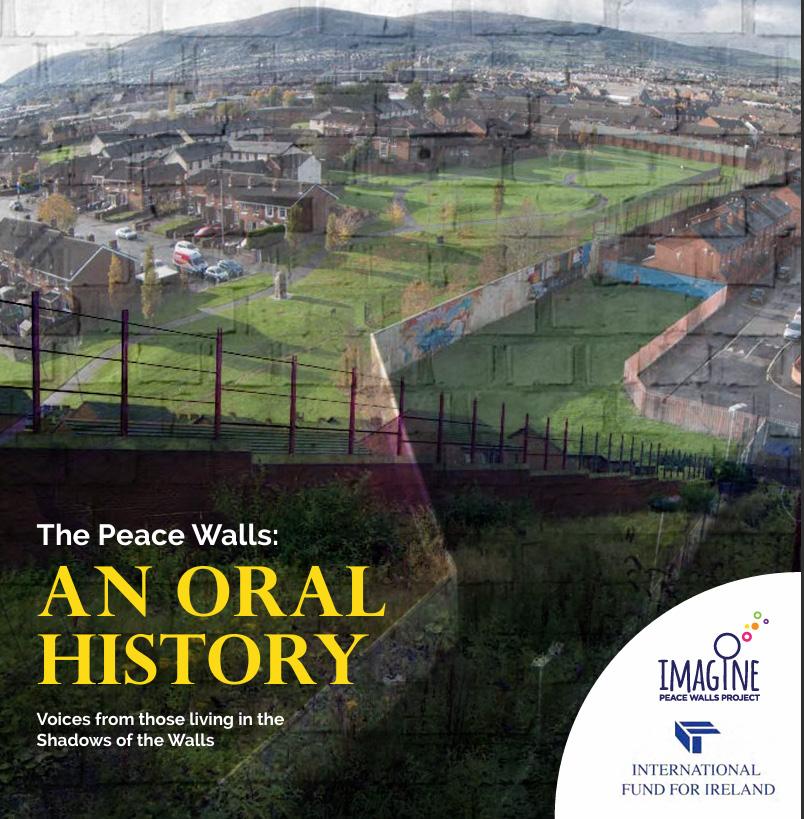

"The Peacewalls: An Oral history" shares personal accounts of Lower Old Park and Cliftonville residents who have lived along side the peacewalls for thirty years or more. Through firsthand testimonies, it explores the lasting impact of these barriers on people’s lives and highlights the importance of shairng stories, memories and experiances as a way of fostering understanding and promoting reconcilliation. It delves into the emotional, social, and political impact of these physical and symbolic barriers which continue to shape the lives of individuals, families, and neighborhoods; influencing both daily life, and a step towards a more cohesive future. I took particular interest in how the residents responded regarding the possible removal of the peacewalls if they felt that the people are ready for the potential reintegration of these two communities.

“I know it’s hard whenever things are still happening. If everything was sort of cut and dry I could say ‘Okay, the war is over, get on with it. We’ve got to do this and got to do that. Pull the Walls down. We’ll all be friends again. We’ll all live together in mixed communities’ but there’s still people out there that still hold on to things and still would like to get their own back.”

(Female, Protestant, 50-59)

“You take these Peace Walls away you are going to have access to each other and it’s going to be … When you can’t see people you can’t start a row and start harming them. It will be a very, very longtime.….. The wall makes you feel a wee bit safer and it makes people on the other side feel safer”

(Male, Catholic, 70-79)

“I hope they will come down in my lifetime, but I would say you are going to have to do an awful lot of work. It’s not just a matter of knocking those Walls down. You are going to have to do an awful lot of work. Forget about the Peace Walls. Make them nice and then spend the money that’s being used and that’s been to get the two groups and build relationships. We don’t want the bloody things. Make them the way they have in New York with a lot of graffiti on them and a lot of dancing wee figures on them. It’s going to be a long time but what you are going to have to do is get the hearts and the minds of both communities – the young ones .”

(Male, Protestant, 70-79)

“I’d love to see it go. I don’t like barriers. Barriers cause problems and I don’t like that. Open it all up. The people will either live together or they will move away. One or the other. Why can’t they forget? That was yesterday; close the door. Move forward. Think of your children and the future you want for them.” (Female, Catholic, 70-79).

“People have a fear of change. A fear of not knowing, because they have lived in an environment like this for so long. I hope in years to come you will see the Walls being transformed into physical structures that create employment or maybe could be part of social housing. I think if anything is going to happen it will happen naturally, all we want to do is live in peace. We have lived through forty odd years or more plus of hardship and strife and really difficult times. It is also about creating an environment where our young kids are educated and they stay within the community rather than moving away and that could have a massive impact.”

(Female, Protestant, 50-59)

“I must confess I have never considered taking the Peace Walls down because I think it’s too early, far, far too early. If they took them down tomorrow there would be a bloody funeral because that would just open the gates to all the mayhem because it’s not over. They were there for a few years but I don’t think it’s anywhere near the right time to … Maybe eight, ten or fifteen years’ time, yes. But I think at the minute …no”

(Male, Protestant, 70-79)

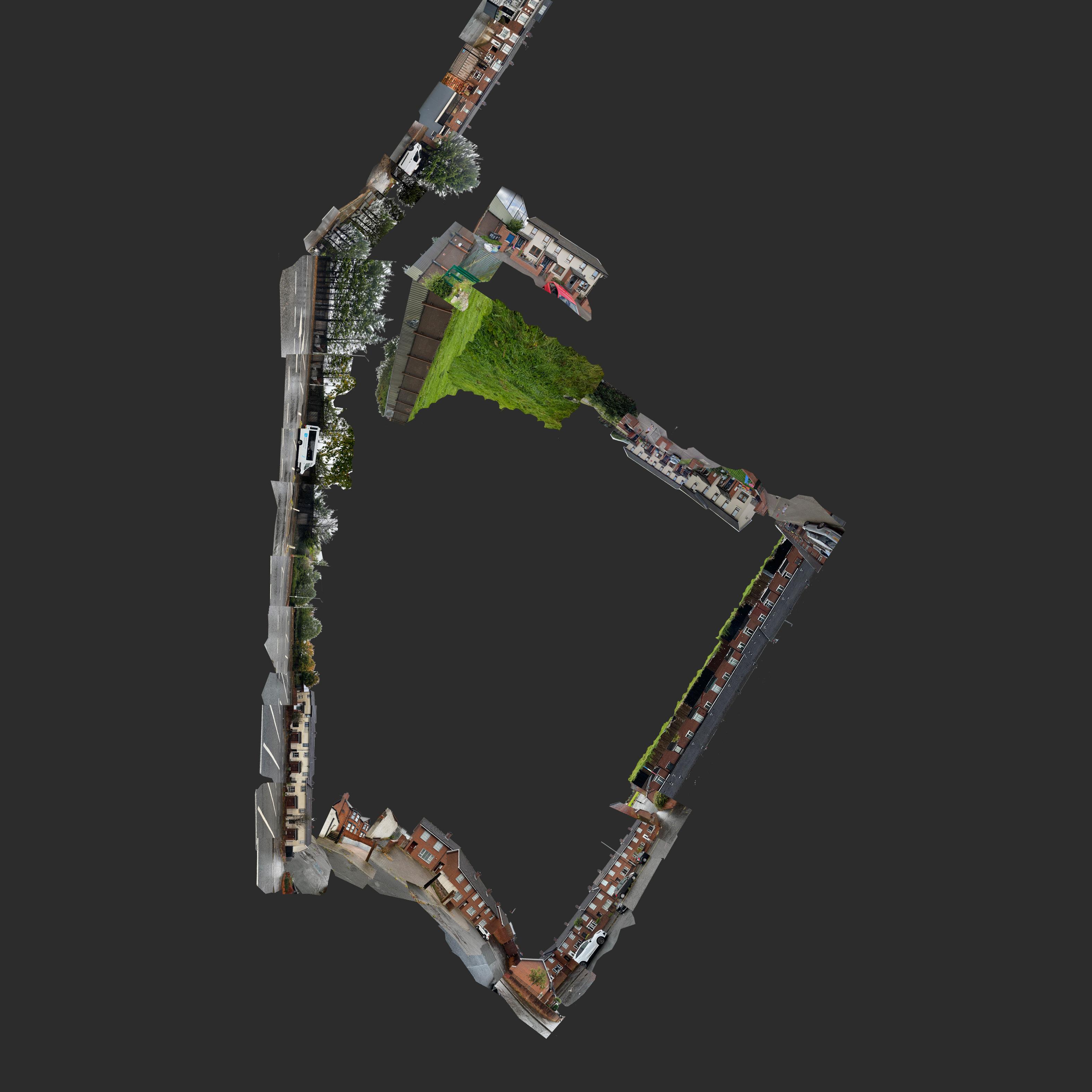

Site Visit

During our site visit I noticed a large neglected/overgrown green space and a scrap yard on either side of the main peace line. I found it interesting how these left over spaces that have been disconnected by the peacewalls, become occupied or lack there of.

Abondoned green space

While not a physical wall, the abandoned green space behind the Peace Wall in Lower Oldpark acts as an invisible divide between communities, reinforcing separation. This underutilized space, could serve as a place for community gatherings or development, but its separation and isloation due to the wall contributes to the social division. It reflects the territoriality theory, where both communities view the space as outside their control, discouraging shared use and interaction. The neglect of this land fosters isolation, limiting opportunities for cohesion and integration. Its lack of access or development creates a subtle psychological barrier, preventing cooperation and maintaining territorial divisions. This “hidden barrier” keeps the communities separated, without being as visibly obvious as the Peace Wall itself. while in the area It felt almost eerie walking on the grass of the abandoned green space, as though you shouldnt be there and that that area belongs to someone, even though it is public space, it felt very hostile and unwelcoming

Scrapyard

The scrapyard on the Cliftonville side of the Peace Wall acts as a buffer zone between the Protestant and Catholic communities, both physically and psychologically. Situated near the wall, the scrapyard occupies valuable land that could otherwise serve as a neutral space for interaction or development. Instead, it creates an industrial barrier that reinforces the separation between the two communities. The scrapyard, with its disorganized and unattractive appearance, discourages cross-community engagement by making the area seem inhospitable, further entrenching the territorial divisions. It represents a kind of neutral ground that is neither fully integrated into either community, yet still marks a distinct division.