The New York Forest Owner

Officers & Directors

Edward Neuhauser, President edward.neuhauser@gmail.com

Beth Daut, Secretary bethdaut@gmail.com

Nick Jensen, Treasurer njensen@merceradvisors.com

Mike Arman, At large member

Dick Brennan, AFC Chapter

Bruce Cushing, SAC Chapter

Beth Daut, At large member

Mike Gorham, At large member

Harmon Hoff, At large member

Nick Jensen, At large member

Dana Allison, WFL Chapter

Edward Neuhauser, At large member

Jason Post, CDC Chapter

Tony Rainville, At large member

Sam Finnerman, LHC Chapter

Art Wagner, At large member

Dan Zimmerman, CNY Chapter

Claire Kenney, Office Administrator PO Box 644 Naples, NY 14512; (607) 365-2214 info@nyfoa.org

Peter Smallidge, Ex-Officio Board Member pjs23@cornell.edu

Stacey Kazacos, Ex Officio Board Member stacey@sent.com

volume 63, number 1

Jeff Joseph, Managing Editor

Mary Beth Malmsheimer, Editor

The New York Forest Owner is a bi-monthly publication of The New York Forest Owners Association, PO Box 644, Naples, NY 14512. Materials submitted for publication should be sent to: Mary Beth Malmsheimer, Editor, The New York Forest Owner, 134 Lincklaen Street, Cazenovia, New York 13035; Materials may also be e-mailed to mmalmshe@syr.edu; direct all questions and/or comments to jeffjosephwoodworker@gmail.com. Articles, artwork and photos are invited and if requested, are returned after use. The deadline for submission for the March/April issue is February 1, 2025.

Please address all membership fees and change of address requests to PO Box 644, Naples, NY 14512 or ckenney@nyfoa.org. (607) 365-2214. Cost of family membership/subscription is $55.

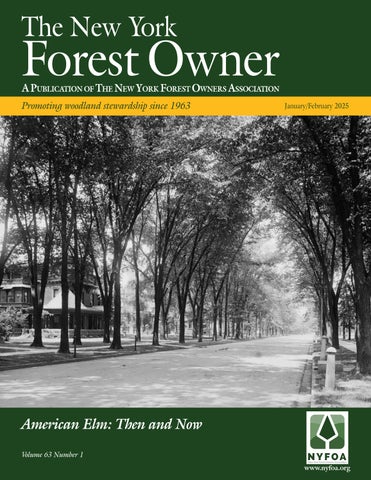

Like countless other streets across New York State and the nation prior to the introduction of Dutch elm disease, West Genesee Street in Syracuse was once lined with graceful, stately elms.

Change is difficult for any individual or organization. Recently the NYFOA board of directors made the difficult decision to no longer have an executive director. Craig Vollmer served for four years as executive director but NYFOA does not have the financial resources to continuing funding this position. On behalf of all the members of NYFOA, I want to thank Craig for his years of service to our organization.

In an effort to make information about NYFOA more readily available to new potential members, the NYFOA BOD has decided to send electronic copies of the magazine to all current members with a valid email address. This will allow members to easily forward electronic copies of the Forest Owner and hopefully will be a small step in continuing to get the word out about NYFOA.

Recently we had a visitor to our woodlot from Paris, France. JeanBaptiste Ingold was able to track me down through the NYFOA website. His family owns a “small” woodland (136 hectares or 335 acres). A more typical sized forest in the same area of northwestern France that is

owned by one of his relatives is 450 hectares or 1,100 acres. His family’s ownership of the forest dates back to the 1830’s, during the reign of Louis XIV, who gave the forest to his family.

All of the large forest owners in this part of France employ a forester to manage the property. Jean-Baptiste said that forestland in this part of France is rarely offered for sale and that there are relatively few owners of small forest properties. Clearly a very different model than how we deal with private woodlands in New York.

Another recent visitor to our property was Jim Townsend, who is the chief counsel to the Adirondack Landowners Association (ALA). Jim lives in Rochester but spends a lot of time at his family’s property in the Adirondacks. The ALA has some very large landowners as members and they have a sliding scale for dues based upon the acreage that you own. The ALA works to promote good forest stewardship and protect landowner rights.

For many years, NYFOA has participated in the Farm Show which is held at the New York State Fairgrounds in Syracuse, NY. This year the Farm show will be held from Thursday February 20 through Saturday February 22, 2025. NYFOA has a booth at the Farm Show where we get a chance to talk with folks that may own forest land and be interested in joining NYFOA. We also have a

continued on page 11

The mission of the New York Forest Owners Association (NYFOA) is to promote sustainable forestry practices and improved stewardship on privately owned woodlands in New York State. NYFOA is a not-for-profit group of people who care about NYS’s trees and forests and are interested in the thoughtful management of private forests for the benefit of current and future generations.

NYFOA is a not-forprofit group promoting stewardship of private

forests for the benefit of current and future generations. Through local chapters and statewide activities, NYFOA helps woodland owners to become responsible stewards and helps the interested public to appreciate the importance of New York’s forests.

Join NYFOA today and begin to receive its many benefits including: six issues of The New York Forest Owner, woodswalks, chapter meetings, and statewide meetings.

( ) I/We own ______acres of woodland. ( ) I/We do not own woodland but support the Association’s objectives.

Name:

Address:

City: State/ Zip:

Telephone:

Email: _______________________

County of Residence:

County of Woodlot:

Referred by:

Regular Annual Dues:

( ) Student $20

(Please provide copy of student ID)

( ) Individual/Family $55

( ) Life $750

Multi-Year Dues:

( ) 2-yr $100

( ) 3-yr $150

Additional Contribution:

( ) Supporter $1-$59

( ) Contributor $60-$99

( ) Sponsor $100-$249

( ) Benefactor $250-$499

( ) Steward $500 or more

( ) Subscription to Northern Woodlands $15 (4 issues)

NYFOA is recognized by the IRS as a 501(c)(3) taxexempt organization and as such your contribution may be tax deductible to the extent allowed by law.

Form of Payment: Check Credit Card

Credit Card No.

__________________________________

Expiration Date ________V-Code______

Signature: _________________________

Make check payable to NYFOA. Send the completed form to: NYFOA PO Box 644, Naples, NY 14512 607-365-2214 www.nyfoa.org

by Jeff Joseph

In over three decades of working with wood, I have only been asked to build something of elm once. It was many years ago, I was new to the area, and the client wanted a handrail made of elm boards that were milled from a tree harvested from their woodlot. Being entirely unfamiliar to me at the time, the elm wood seemed quite exotic. Yet a century ago, we all would have been well acquainted with elms, and elm lumber. Sadly, their stature—both literal and figurative—has declined precipitously in the interim, which is unfortunate, as it is a tree with many unique traits and virtues.

While there are six elm species native to North America, I will limit my focus here to American elm (Ulmus americana), as it is by far the most common and iconic of our elms, and is the only one I have direct experience working with. Also known as white or soft elm, U. americana is widely distributed, being found throughout New York State, and the entire eastern half of the U.S., excepting the southern half of Florida and the Gulf Coastal plain. With such a wide distribution, it is very adaptable to a range of soils and climate, but prefers rich, fertile bottomlands that are moist yet well-drained, and the edges of streams, rivers, and lakes. Never growing in pure stands, elm historically was a very minor component of mixed upland woodlands, and reached its highest numbers (up to 1/3 or more of standing timber) in the bottomlands that are its preference.

But the reason that past generations knew elm so well was not due to its presence in eastern woodlands at all, but rather for its near universal presence as a cultivated tree in yards, parks, cemeteries, and most notably, lining countless streets throughout the country. This was certainly true in towns and cities

Figure 1. A rare sight today, massive elms such as this picturesque specimen growing around the corner from NYFOA president Ed Neuhauser’s home in Groton, New York were once common throughout our region. The dieback visible in the crown is cause for concern.

throughout New York, from Manhattan to upstate cities such as Syracuse, Buffalo, Utica, and Rochester, each of which planted many thousands of elms in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The motive behind the widespread planting of American elm was that due to its

unique genetics, it naturally grew with a form ideal for being incorporated into the man-made landscape. On top of a tall, straight, and clear stem, the crown of an American elm would naturally assume a symmetrical, vase or fountainlike shape, a ‘vaulted arch’ of limbs and

foliage as aesthetically pleasing as it was accommodating of roads and buildings, without any need for pruning (Figure 1).

The arrangement of the foliage in a single plane along the branches provided needed shade while allowing some dappled light through, like a lattice. In many ways it was, and remains, the archetypal image of a deciduous tree; if you’ve ever seen a well-formed, mature specimen, you will know exactly what I am talking about. Alas, these once common denizens of towns and villages across the nation have become a rarity, due to the ravages of Dutch elm disease, which was first discovered in the U.S. in Ohio in 1927. “Dutch” elm disease is actually a bit of a misnomer, as although it was first found in the Netherlands in 1921, it is most likely of Asian origin (first transported to Europe and subsequently to the U.S. on figured elm veneer logs).

Like so many other tree diseases, Dutch elm is a two-part affliction, with

an insect transporting a fungus from tree to tree. In this case, there are three carrier insects, all elm bark beetles (one native, two European), that feed on elm cambium, phloem, and inner bark, where they also lay their eggs. The fungi are a group of closely related species that colonize and consume those same living tissues favored by the bark beetles, who conveniently (yet unwittingly) carry them there, or at least create the entry points for the fungus. In an attempt at self-defense, the trees exude gums and cellulose that do little to slow the fungus, but end up blocking their own xylem and ability to transport water from their roots to their crowns, causing dieback, and in most cases, death within a few short years. Sadly, large and mature trees with thick bark are preferred hosts for the bark beetles, so the oldest and grandest specimens are attacked preferentially.

Elm yellows, also known as elm phloem necrosis, is another elm specific

disease caused by a non-native, bacterialike phytoplasma that feeds on the vessels that transport sugars from elm leaves to the rest of the tree. By stopping the flow of carbohydrates and other nutrients, it starves an infected tree to death. While likely first introduced into North America in the late 19th century, it was overshadowed by the subsequent and overwhelming effects of Dutch elm disease. Like Dutch elm, it too is transmitted from tree to tree by an insect, in this case the common, native whitebanded elm leafhopper, which feeds exclusively on elm foliage, and possibly by other phloem feeding insects. It should also be noted here that each of these elm diseases can be spread underground through root grafts, which were likely common in the densely packed plantings of elms in urban areas.

To make matters even worse, in August of 2022 an invasive insect from

continued on next page

East Asia—the elm zigzag sawfly—was detected for the first time in New York State, and since has been confirmed to be present in at least 23 counties statewide. This insect feeds exclusively on elm foliage, leaving a distinctive ‘zigzag’ pattern in its wake (Figure 2). While it does not seem to cause enough damage to kill trees outright, the feeding does reduce photosynthesis, leading to branch dieback and crown thinning, adding stress to already weakened trees. We will likely be seeing much more of this insect in the near future, as it is capable of flying over 50 miles in a single year, and produces 4-6 generations of offspring in a single season. Under this multifaceted assault, most of our most revered and iconic elms have perished (excepting those regularly treated with systemic pesticides), making those that remain that much more valuable, and, I would argue, underappreciated.

Beyond its iconic silhouette, American elm can also be readily identified by its leaves, bark, and fruit. The 3-6” long leaves are alternate, oval-shaped, with a sharply double toothed margin, tapering to a point at the tip. They have a distinct asymmetry, with the bottom edges of each leaf meeting the very short (+/1/4”) petiole unequally at the base, giving them a lopsided appearance (Figure 3). Elm leaf litter is high in both potassium and calcium, and decomposes rapidly, so elm foliage has long been known as a soil builder, and occasionally as a livestock feed. If you’ve got any elms around the yard, rake and compost the leaves and apply the rich mould to your garden or other plantings in need of some fertilization.

American elm bark is a uniform grey to grey-brown when mature, and is deeply furrowed, with irregular, elongated, raised ridges (Figure 4). Unlike many of its arboreal neighbors, the bark of even young stems is quite furrowed, but in varying shades of brown rather than the monolithic gray that it will develop later in its life (Figure 5). Elm bark is surprisingly corky or ‘spongy’ to the touch, not at all hard and brittle like other trees with similar thick, furrowed bark.

American elm is monoecious, with its perfect flowers (containing both male and female parts) in hanging clusters that are wind-pollinated. Flowering takes place in early spring before the leaves emerge. Its small, flattened seeds are encased in papery, hair-fringed samaras that are disseminated (also by wind) shortly thereafter. A high percentage of these seeds germinate immediately, and as it is a prolific and precocious seeder, elm enjoys a competitive advantage in its preferred habitats following disturbance. As the seeds are small with minimal

reserves, seed survival is highest when germinating in direct contact with mineral soil, and when given partial shade for the first year, after which full sun will give the most rapid growth rate.

Elm is considered intermediate in shade tolerance among its peers, allowing it to compete to a degree with faster growing or more shade tolerant species in its environment, and it responds well to release from shade. Young to middleaged elms can also regenerate through the formation of stump or root sprouts, though this ability declines with age and

tree size. Mature, healthy American elms can (or at least could) reach 150’ in height and 6’ in diameter. Interestingly, for an early-successional pioneer tree, it is quite long lived, maturing at about 150 years old, with some individual trees reaching upwards of 300 years of age. According to the DEC’s Big Tree Register, New York’s current “champion” elm resides in Fulton County, and is 140’ tall and 5’ in diameter.

It is thought that elm’s current postDutch elm survival ‘strategy’ is to grow fast when young, and to reproduce as

soon as possible (as early as 15 years of age), allowing it to persist, just with nowhere near the majesty or longevity of its heralded past. The numbers bear this out: according to the USDA in 2017, elm ranked 17th in New York among all major tree species for total numbers of stems between 1-4.9” DBH (about 150 million trees); it was 20th in total number of stems 5+” DBH (about 40 million trees). In each case the overall number of stems had declined significantly since the previous survey 10 years earlier. Due to the lack of sawtimber-sized stems statewide, it

was not even ranked for overall volume in either cubic feet or board feet. So lots of small elms, with very few surviving to full maturity.

Like most everything else about this tree, the wood of American elm is very distinctive in its character, with a host of what are, from the perspective of a woodworker, both positive and negative traits. It is a coarse-grained, ringporous, lightweight wood, with only a subtle gradient between its very light brown heartwood and lighter tan/blonde sapwood. The colors are not as uniform as with maple or birch, often showing much variance even within the face of single board (Figure 6). Identifying elm wood is quite easy once you become familiar with it. To get technical for a minute, the earlywood pores are large and are arrayed in a single narrow, continuous row. The adjacent arrangement of the parenchema (food storage) cells within the pores of its latewood is so distinctive to the genus that it has been defined as “ulmiform.” When looking at elm endgrain, the arrangement of these pores in the latewood look like miniature, light colored, jagged EKG readings against the darker backdrop of the rest of the more tightly bunched latewood vessels (Figure 7). The medullary rays are visible, but only with a handlens. On the flatsawn faces of an elm board (parallel to the growth rings, or tangent to the circular stem), these jagged lines within each growth ring look ‘feathery,’ in a pattern like herringbone or tweed (Figure 8). It is so distinctive and unusual that you’ll always immediately associate it with elm, though some of the same figure evidently also shows up in hackberry (Celtis occidentalis).

Weighing about 35 pounds per cubic foot when dry (by way of comparison, about 25% less than sugar maple), American elm is not particularly hard, with a Janka hardness rating of 830 foot pounds (about 75% less than sugar maple), yet is quite strong and tough. Its modulus of elasticity (a measure of stiffness and compressive strength) is 1,340,000 lbs./sq. inch (about 35%

continued on page

By Scott J. Meiners Cornell University Press, 2023

One of the biggest challenges we face as woodlot owners is determining how to go about encouraging others to value the role that privately owned woodlands play in society. When you consider that only a small fraction of those who own forested land in the U.S. have any type of explicit management strategy to guide how that land will be used, let alone preserved as healthy and productive woodland for the long term, appealing to the non- forest owning public to value and support the maintenance and stewardship of woodlands can seem like an impossible task.

With so many pressing cultural and ecological issues facing us as a society, and with even highly degraded woodlands still at least looking as green as ever to the uninitiated, how do we go about convincing our fellow citizens to care about forestlands enough to prioritize them in municipal planning and government funding, and ultimately just in instilling a communal sense of responsibility and ethics in all members of society around forest management that would serve to discourage many of the worst abuses of woodlands taking place around us today? And how do we encourage this kind of “land ethic”, as Aldo Leopold once famously wrote, not just for iconic and charismatic old-growth stands and trees, which undeniably hold immense cultural, historical, and ecological value, but perhaps even more so for the countless small holdings of secondary forest like those we own that are in varying stages of recovery from being converted to cropland or pasture over the past two centuries?

A tall order to be certain, and a cynic might say an impossible one in our society at present. But it is exactly this challenge that led Scott Meiners to write Tree by Tree, which is an attempt to utilize stories of the challenges facing individual tree species in eastern North America to

by Jeff Joseph

highlight the big picture of what we stand to lose as our forests are slowly but steadily degraded by a multitude of stressors, losing their integrity and resilience in the process. Meiners is a professor of biology at Eastern Illinois University, and has spent much of his professional career in the study of vegetation recovery post-agriculture, putting him in a uniquely qualified position to assess the state of our forestlands in the eastern U.S., near all of which were stripped of tree cover at least once by our forebears on this continent.

Tree by Tree starts with a succinct attempt to place the degradation of Eastern North America’s forests in a broad historical context, from the geological forces that led to the formation of our current landscape, to the rise and retreat of the Wisconsin glaciation, to the impacts of human activity on woodlands, to the current rapid rise of climate change. While noting that change is constant and natural in ecological systems, Meiners points to the radically accelerated pace of change at present as the critical cause for concern, as the rapid spread of pests and diseases, and climate change in particular, outstrip the ability of individual tree species and entire forest ecosystems to adapt, leading to irreversible declines of forest biodiversity, resilience, and integrity.

The heart of the book moves to focus on the plight of individual tree species and their ecology as case studies and exemplars of forest stress and decline. American elm, American chestnut, eastern hemlock, white ash, and sugar maple each get their own chapter, all of which are full of concise and relevant detail. A subsequent chapter deals with the challenges faced by a number of ‘lesser’ species, including flowering dogwood, American beech, black walnut, and white oak.

Meiners then moves on to an overview of some of the most prominent interfering and/or invasive plants inhibiting forest regeneration, succession, and native flora, among them the tree of heaven (Ailanthus), Norway maple, wineberry, honeysuckle, bittersweet, garlic mustard, and stiltgrass.

This same chapter also addresses the loss of predators and the subsequent explosion of the deer population across our region, and the profound impact it has had on forest regeneration.

The next chapter provides a ‘sylvographic’ study of Mettler’s Woods, an old-growth forest in New Jersey owned by Rutgers University where Meiners conducted his dissertation research. The clear upshot of the many changes he documents from his extensive time spent in this once majestic woodland is that protection from logging in no way provides protection from all the ills being visited upon the broader forested landscape that we all share.

In conclusion, Meiners leaves us with four suggested strategies to combat the many threats elaborated throughout this highly engaging and ambitious book, and perhaps most surprisingly, considering the dire picture painted, a sense of optimism about the future. If you were looking for one book to offer to a friend, family member, colleague, or political representative to educate them about what we are faced with and stand to lose with the current threats to our forestlands in the eastern U.S., this is the one. Highly recommended.

by Kristi sullivan

Mink are very active and inquisitive animals, with a keen sense of smell and sight. They are most active at night and in early morning. On land, they move with a quick, bounding lope, which they can continue for miles. This characteristic lope leaves paired tracks, which stand out in the winter snow along stream banks and beaver ponds. Mink are at home in the water as well, and they swim and dive with ease.

Mink occupy a wide variety of wetland habitats but most commonly are found along streams and beaver dams in undeveloped rural areas. Here, they can be seen traveling from one stream bank to the other, investigating nearly every hole, crack, crevice, and overhang that may hide a potential meal. Mink are best suited for areas with excellent water quality because these waters will hold the greatest concentrations and varieties of prey. Like most mustelids, they are agile and fierce fighters, killing prey with a hard bite to the back of the skull. Prey includes muskrats, mice, rabbits, shrews,

The mink is a semi-aquatic member of the Mustelidae family. Its relatives include weasels, martens, fishers, wolverines, badgers, and otters. They occur throughout New York State in areas with suitable habitat. Adult male mink average two feet in length, including an 8-inch tail. They weigh 1.5 to 2 pounds. Females are slightly smaller than males and weigh up to half a pound less. Like weasels, the mink has short legs, a 6–8 inch bushy tail, a long neck and body, short head, and a pointed muzzle. A mink’s coat is thick, full, and soft. The fur is dark chocolate brown on the back, blending into a slightly lighter shade on the belly. A distinguishing characteristic of mink is a small, white patch of fur on the chin.

fish, frogs, crayfish, insects, snakes, waterfowl, and other land birds. Mink are opportunists, feeding on whatever is most abundant or most easily caught. They occasionally kill more than they can eat and will cache carcasses in the winter and revisit them to feed. In turn, mink are prey for foxes, bobcats, and great horned owls. In the wild, mink typically live to be two or three years old.

To find enough prey, males require a home range up to three square miles, while females use a much smaller range. Individual territories overlap, and several animals in succession may use the same den. One mink will have several dens along its hunting route. They den in abandoned woodchuck tunnels, hollow logs, vacant muskrat lodges, holes in stone piles, and beneath large tree roots. Dens are usually near water and may have more than one entrance. Mink line their nests with dried grass, leaves, and feathers.

Overall habitat requirements for mink include an abundant food supply, permanent water, and undeveloped shores.

Woodland owners who would like to enhance habitat for mink can focus on protecting water quality and limiting the use of pesticides on lands adjacent to water. High-quality, pesticide-free water improves insect populations, which in turn provide food for animals that mink prey upon, like frogs. Woodland owners can also create riparian and wetland buffers and protect existing buffers from development. Brush piles can be created to serve as denning sites, if naturally occurring dens are not available. A few large trees felled and left on the ground can provide future logs for feeding and denning. Dead wood protruding into the water will provide cover for mink prey as well.

Kristi Sullivan is a Wildlife Conservation Specialist in the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment and Directs the New York Master Naturalist Program. More information on managing habitat for wildlife can be found at https://blogs.cornell.edu/ nymasternaturalist/

series of talks on Friday and Saturday that are free and open to anyone who might be interested in learning more about managing their woods.

We need NYFOA members to staff the booth at the show. Claire Kinney, our NYFOA administrator, will be setting up a schedule of NYFOA members who can volunteer at the booth. If you can get to the show and might enjoy spending half a day talking with the public, please let Claire know at ckenney@nyfoa. org. It will also be very nice to have a chance to attend a few of the free talks that will be available.

We sometimes do not recognize that some active members of NYFOA add a great deal to the organization and that their efforts can sometimes save the organization, a lot of money. I have known and benefited from all of the time and effort that Hugh Canham has volunteered in organizing the Farm Show talks over many years. What I did not realize is that by putting in all the work and effort that Hugh does in organizing these talks, the Farm Show waives our participation fee, which is ~ $1,000. On behalf of all of the members of NYFOA, I would like to thank Hugh for all his work over the years.

I have received positive feedback about the idea of developing a list of NYFOA members who have knowledge about specialized subjects within the sphere of NYFOA’s mission and would be willing to share that knowledge with those who would take the time to visit them. As a place holder, I have named this idea the “reverse MFO visit”. A MFO visit takes place when the MFO visits someone’s property and walks the property together with the owner, providing ideas on what potentially could be accomplished on their property.

The idea of the “reverse MFO visit” is to have someone who wants to learn more about a particular subject visit someone who has some specific knowledge about that particular subject and is willing to spend an afternoon passing on that information. I have tried for a long time to come up with a better, more descriptive name than “reverse MFO visit”, with no luck. So I’m asking for help from NYFOA members to help me come up with a better name that more accurately describes this idea. Please let Claire know your ideas and the final name will be selected by the BOD. As an incentive to help you get your thinking caps on, I will give the winner 100 board feet of red pine lumber. All the winner has to do is to come to our place to pick it up.

The BOD has been doing a great job in coming up with new ideas to help get the word out about NYFOA. In the first example that I would like to mention, Dick Brennan of the AFC has agreed to chair a quarterly Zoom meeting of all the chapter chairs. The purpose of these meetings is to allow the chapter chairs to share ideas on developing programs for their chapters. This was initially started under Craig Vollmer and has proven very useful. I am

very grateful to Dick for continuing to lead this effort.

Bruce Cushing has been pushing the BOD to evaluate new ways to increase NYFOA’s name recognition. Bruce’s suggestion is to place small ads in statewide newspapers such as the New York Outdoor News and regional monthly papers such as the Hill Country Observer (a paper covering eastern NY, southwestern Vermont and the Berkshires) and Adirondack Sports. Small business card-sized ads are relatively inexpensive and would effectively get NYFOA’s name out in front of the public. This is an excellent suggestion that deserves further consideration.

Hope to see some of you at the Farm Show in February.

–Ed Neuhauser NYFOA President

Free programs to help landowners get more benefits from their woodlots will be presented Friday and Saturday, February 21 and 22, during the 2025 Farm Show in Syracuse by the New York Forest Owners Association, in cooperation with the American Agriculturist magazine. The talks are held in the Martha Eddy Room in the center of the Art and Home Center building. These programs are presented by the New York Forest Owners Association in cooperation with the NY Department of Environmental Conservation, Cornell Cooperative Extension, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and with special thanks to each of our expert speakers.

Learn More, Earn More. Seminars are free and open to all. Topics include managing small woodlots, maple syrup making, deer management, supporting native plant pollinators, and federal cost sharing for woodlot improvements, and legal aspects of property ownership, among others. Programs start on the hour and allow time for questions and discussion.

In addition to a display area there will be a NYFOA booth in one of the other large show buildings.

Visitors are encouraged to bring their questions and pause at the booth area before or after attending a seminar program. Trained volunteers will be there to help with resource materials, displays, and expert advice.

Friday February 21

Moderator: Michael Gorham, New York Forest Owners Association

10AM: Deer Control by Means of Slash Walls

Peter Smallidge, Cornell Cooperative Extension Forester

The increasing number of deer in New York is causing problems when trying to regenerate a woodlot after a timber harvest. Using the slash produced during harvest to create barriers to deer can be an effective control mechanism.

11AM: Invasive Species in Your Woodlot

Peter Smallidge, Cornell Cooperative Extension Forester

Many nonnative plant species find their way into our woods and forests. Controlling these invasives helps the native plants and grows a more robust forest for the future.

1PM: Carbon Programs for Forest and Woodland Owners

Ian Crisman, NY State Department of Environmental Conservation

Family forest owners who own just a small number of acres may be eligible to be paid for managing their land in a way that increases the capture of carbon and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Learn how you might benefit and the issues that go with committing your land.

2PM: Silvopasturing: New Opportunities for Woodland Enhancement and Income

Brett Chedzoy, Cornell Cooperative Extension Forester

There are good opportunities in New York to manage your land for both woodland values and livestock production. Goats, sheep, or cattle can be tended on the same ground with certain tree species if carefully managed. There are benefits to both the land and the farmer-owner.

Saturday February 22

Moderator: Christian Torries, American Agriculturist magazine

10AM: Carbon Programs for Forest Owners

Calvin Norman, Pennsylvania State University

Family forest owners who own just a small number of acres may be eligible to be paid for managing their land in a way that increases the capture of carbon and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Learn how you might benefit and the issues that go with committing your land.

11AM: Effects of Climate Change on Northeastern Forests

Calvin Norman, Pennsylvania State University

The warming of our planet is producing some important changes in the forests and woods of the northeastern United States. What are the changes, and how they might affect how we handle our vital forest resources both nationwide and on your small acreage?

1PM:

Dylan Parry, State Univ. of NY College of Environmental Science and Forestry

Pest insects are always of concern in our forests and woodlands. In New York, we need to pay attention to emerging threats while also not ignoring more established species, whether they are invasive or native. The status, control efforts, and the effects of some of our major threats as well as some that are emerging as concerns will be discussed, especially in light of a changing climate. Woodland owners need to remain vigilant and plan their activities accordingly, recognizing that their short and long-term management objectives will dictate any response to insects of economic concern.

2PM:

Craig Vollmer, New York Forest Owners Association

Owning and managing a patch of woodland can be very satisfying and rewarding.A professional consulting forester can help you sustainably manage your woods, for timber sales, wildlife habitat, to carbon capture, and other benefits. A professional management plan will help you obtain cost-sharing for forest improvement practices.

Forestry Awareness Day in Albany is coming up and will be held on Tuesday March 4th. This is an annual event organized by the Empire State Forest Products Association (ESFPA) and, as in the past, NYFOA has been invited to participate in two ways. We will have a table to display NYFOA material, set up in the lobby of the Legislative Office Building (known as “The Well”), and we will join with members of ESFPA in short meetings with legislators and their staff. We need 2 people to staff the table and greet people passing by. In the past this has been a busy corridor with many legislative staffers coming and going during the day. We also should have about 10 people to join in the small groups (3-4 people per group) to make legislative visits during the day.

This is an exciting event and has been well received by our members who have participated in the past and gives NYFOA a chance to get our name out there and provide a little education for our Albany representatives and their staff. The event will run from 9 AM to 4 PM. People are urged to arrive between 8 and 9 AM as there can be long lines to go through security. The first item of the day will be a briefing and explanation of the visits and key issues to cover. Usually, some key legislators make a short presentation between 9 and 10 AM. The rest of the day is given over to a series of 15–30-minute meetings. ESFPA staff will set up these meetings beforehand and will provide handout materials for visits. Lunch will be covered for NYFOA members who participate.

Since this is an all-day event in the winter it would be easiest for our members in the Southern Adirondack, Capital District, Southern Tier, Central New York, and Lower Hudson chapters to attend although all are welcome. If you can participate, please email Hugh Canham at hocanham@esf.edu with your name, email address, and county where you live or where your woodlot is located. ESFPA will try to include one visit with your local assembly person or state senator and will be sending out directions and parking information etc. to those who register. Email me if you have any questions.

Materials submitted for the March/April Issue issue should be sent to Mary Beth Malmsheimer, Editor, The New York Forest Owner, via e-mail at mmalmshe @syr.edu Articles, artwork and photos are invited and if requested, are returned after use.

Deadline for material is February 1, 2025

Make check payable to NYFOA. Send the completed form to: NYFOA, PO Box 644, Naples, NY 14512. Questions? Call (607) 365-2214 * Minimum order is 25 signs with additional signs in increments of 25.

I am sorry to share with you that by the time you read this, I will no longer be your executive director. As a professional forester and a forest owner it has been my great honor, over the last four years, to serve NYFOA, and to serve all of you. NYFOA is a great organization with a great mission, full of great people with incredible passion for their woods. It has been a pleasure to see the passion you all have in action and to spend time with you in the woods. I regret that I did not get a chance to meet more of you and see more of your properties. NYFOA is special for sure, but it is all of you that make it that way.

Together with the leadership, we have worked to build NYFOA’s value to you as members and relevance to the outside world by demonstrating that it is the leading organization providing educational and networking opportunities for its members, and is recognized as the leading voice of all forest owners in New York State. There is no other statewide organization like this. I hope that this effort has made your membership worthwhile and that it motivates you to be engaged.

The forests and woodlots of NY, your forests, your woodlots, have never been more important and have never been getting more attention than they are now. They and those that own them, like you, are under a microscope to say the least. As NY

embarks on an ambitious agenda to mitigate climate change, it recognizes the vital role that healthy forests play in that; this could be good for forest owners and forestry. Since most of NY’s forests and woodlots are privately owned, it is therefore recognized how important a role that those who own them will play. This matters because this recognition will lead to policies, regulations, and programs aimed at the forest and the forest owner. This matters because it will fuel a desire to forge a publicprivate “partnership” to ensure NY’s forests continue to be abundant, robust, and healthy.

NYFOA has never had a more important role to play in the fulfillment of its mission and to be the statewide voice for all of you in the policy arena. NYFOA needs to have a seat at the table to be influential. If it is not at the table, if it is not influential, the decisions made for the coming policies, regulations, and programs will be made by and influenced by others and you as the forest owner will be in the backseat

instead of the driver’s seat. NYFOA cannot be at the table and cannot be influential without being robust and healthy itself, and that is only made possible by dedicated volunteers willing to invest some of their time, energy, and talent to the organization.

So, as my time with NYFOA comes to an end, I would leave you with one final encouragement to get more actively involved in your chapter or serve on the state board or its committees, to share your talents and skills; I would also encourage you to set aside the time to participate in the events that fellow members have organized for you. If you haven’t gone on a woods walk, or attended one of the other programs, or even just broken bread with your fellow members at a dinner or picnic, I assure you that you are missing out on a great time, missing out on making new friends who love the woods like you do, missing out on the opportunity to expand your knowledge about the forest, and missing out on the important opportunity of making your voice heard.

I know that we are at a point in our culture where people are more reluctant to volunteer, and that life gets busy, but I promise you that volunteering in NYFOA will be a rewarding experience, without being a life sentence. You will be helping NYFOA grow, helping it thrive and prosper, helping it function well, helping it provide the benefits and services to its members, helping ensure that it will continue to exist for you and others down the road, and it is an awesome opportunity to meet and work together with other woodlot owners. But it takes dedicated people willing to sacrifice a little of their time for all that to happen. As the saying goes, many hands make light work, and by volunteering you ensure that

everyone stays energized and no one burns out. NYFOA has been led from top to bottom by a group of incredible people who are extremely dedicated to the organization and all of you that make it up; many of whom have served for a lot of years, but they cannot serve forever and need your help. I hope you will consider helping your NYFOA be everything it is and more.

I will miss being on the front lines of private forestry in NY as your executive director. I will miss all of you, but I am sure we will see each other in the woods sometime, somewhere. So, I will not say goodbye; I will just say farewell. Until we meet again…go to the woods — take it all in and love it until you can’t.

–Craig Vollmer

t-shirts, hoodies, baseball hats, vests, golf shirts, coffee mugs, coolers, and more!

367-5916 email halefor@verizon.net

A column focusing on topics that might limit the health, vigor and productivity of our private or public woodlands

Coordinated by marK Whitmore

bY mArk whitmore

While contemplating writing this article over the Thanksgiving holiday, wondering which bad bug to tackle, I realized that I am thankful for the bugs that eat trees but don’t cause

huge problems. I know they’re out there, a myriad of bark chewers, leaf eaters, and sap-suckers lurking, just waiting for their chance at fame. Some are here already; others are waiting to be transported

from some far away land. But the thing is, only a few really develop into widespread tree killers like Asian longhorned beetle, emerald ash borer, spruce budworm, spongy moth, southern

The thing about these pests that I’m thankful for is that they help point out mechanisms at play that keep them from becoming mega-problems. The pests I’ve been thinking about fall into two basic categories: native pests that were problems in the past but seem to have lapsed into obscurity, and pests introduced from other places that looked problematic at the outset but fizzled over time. Keep in mind when contemplating why these potential problems don’t

materialize is that their populations are kept in check by the interaction of abiotic factors like the weather, biotic factors like predators and microbes, and resistance of the host trees. It’s a combination of these factors that keep populations in check. With some insects tree resistance might be more important and with others it may be predators or microbes. These factors are always shifting, and this is what drives periodic outbreaks. So, as I consider the following examples, I’m thinking to myself “Will the currently innocuous populations stay that way, or will we see them develop into periodic problems?”

continued on next page pine beetle, or hemlock woolly adelgid. I did some digging through old records and talked with colleagues to jog my memory and came up with interesting examples.

The forest tent caterpillar (FTC), Malacosoma disstria, sort of fits into the first category but I include it because it illustrates periodic outbreaks. It’s a native insect that we haven’t seen defoliate large swaths of trees in New York since 2009, when over 500,000 acres were impacted. This moth is a defoliator of early season foliage and can be quite destructive, especially in sugar bush operations. FTC is widespread in the deciduous forests of North America and experience says it will come back, but 15 years is a bit long between outbreaks. It’s well documented that FTC populations are controlled

effectively by parasitic flies, wasps and a polyhedrosis virus, but what triggers their outbreaks? It’s undoubtedly a combination of factors. We have little data on the impact of natural enemies when pest populations are low, so it’s hard to say what their influence may be. However, during the buildup to the last outbreak in 2007 I first noticed defoliation of sugar maple along a stretch of sharply drained soil above one of the Finger Lakes, indicating that trees resistance was weakened. We likely don’t have long to wait until the next outbreak, so if you have a sugar bush you will want to be watching for those first signs of FTC defoliation in early spring.

Another native defoliator that’s a little more puzzling is the saddled prominent (SP), Heterocampa guttivitta. This moth is a late-season defoliator with foliar damage noticeable from late July into August. It’s favored trees are sugar maple, beech, yellow birch, and apple. Found throughout eastern forests, SP is most damaging in the Northeast. In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s SP defoliated more than 1.5 million acres in the Northeast and Pennsylvania. The most recent defoliation event in New York was 35 years ago in 1989 when 130,000 acres were defoliated in the southern Catskill towns of Margaretville and Stamford. 35 years is a long time between outbreaks, and all I can do is guess what’s going on.

Of the imported pests, the story of the red pine scale or pine bast scale (PBS), Matsucoccus matsumurae (used to be M. resinosae) is interesting. There are several native Matsucoccus scales in North America, mostly on pines, which cause little damage. PBS was first reported on many dying red pines in Connecticut plantations in 1946. It may have been imported from eastern Asia on ornamental pines planted for the New York World Fair in 1939. PBS is a small, soft bodied sucking insect that hides beneath bark scales, feeding on twigs and producing a waxy wool on its body. It is difficult to detect until symptoms of dying branches are found. There are no specific parasites

for this group of insects, just generalist predators. Like hemlock woolly adelgid, PBS disperse as a “crawler” after hatching from the egg stage. Crawlers are carried by wind, birds, or small mammals from tree to tree. PBS spread through CT, the lower Hudson Valley, and NJ. There was great concern about the damage PBS was causing to red pine. A quote from the New York Times on 27 Jan 1977 illustrates this concern: “We have no way of controlling it,” a New York State forester, said during an inspection tour the other day. “The real problem with this insect is that if it continues to spread, it will one day kill every red pine tree on the North American continent.” Fortunately, this has not happened. PBS caused mortality of red pine in areas south of its natural distribution, what we call off-site plantings. Currently, PBS is occasionally found in native red pine forests, but not causing mortality, in essence acting like a native insect, unable to damage healthy trees growing on sites the red pine prefers and where they are resistant to PBS infestation.

Another example of an introduced insect that appears to be acting as a native is the sirex woodwasp (SW), Sirex noctilio. This large broad-waisted wasp is native to Europe in pines and became infamous when it turned up in the radiata pine plantations established in the southern hemisphere causing large areas of mortality and economic loss. SW inserts its modified stinger into the wood of a living tree where it deposits an egg and at the same time a toxic mucus and a fungus. The toxic mucus shuts down the conductive tissues in the wood allowing the fungus to grow and kill the tree. The larva grows by consuming the wood and the fungus. We were concerned about the possible introduction of this insect to North America because of the widespread damage it had caused in the past. In 2004 SW was detected in pine near the port of Oswego, NY. SW are strong fliers, and they spread rapidly around the state. It’s been 20 years since that initial detection and SW has yet to be found killing anything but weak and suppressed trees, just like a native insect would.

Pine false webworm or red-headed pine sawfly (RPS), Acantholyda erythrocephala, is another broadwaisted wasp that feeds on the needles of pines. Introduced from Europe in 1952, it has become widely established in the northern states and Canada. Adult sawflies lay eggs in old needles in spring. Hatching larvae feed on old needles from within silken tubes that they construct. When they finish larval development by the end of June they drop to the ground where they overwinter. Defoliation won’t kill the pines immediately, but it will weaken them making them vulnerable to other pests like native bark beetles. RPS was first detected in New York in 1991, and in 1994, 500,000 acres of white pine were defoliated in St. Lawrence County. In 2000, significant defoliation was noted in northern NY, but since then there have been no reports of defoliation in the records. A parasitic tachinid fly was introduced from Europe to Ontario in the early 2000’s as part of a biocontrol program and a virus was also introduced, but sawfly populations naturally go through wild fluctuations which made evaluation of these biocontrol agents difficult. Yet, after 24 years and no defoliation found, perhaps they have spread to NY and are working?

I could bring up more examples like the pine shoot beetle, Tomicus piniperda, introduced from Europe in the early 1990’s which spread rapidly through the state but never developed into the problem we had anticipated. Then there are others where a few individuals are caught in survey traps but don’t seem to establish, like the European oak borer. More pests will be inadvertently introduced in the future, and having these past examples helps us to evaluate their response in our forests. Of course, the moving target is what will happen as our climate changes, and trees are exposed to new climatic conditions that may be stressful and open them up to attack by a pest that they were resistant to in the past.

Mark Whitmore is a forest entomologist in the Cornell University Department of Natural Resources and the chair of the NY Forest Health Advisory Council.

NYFOA would like to thank and recognize B&B Forest Products of Cairo, NY for their generous sponsorship. We are grateful for their support of our organization and its mission.

We welcome the following new members (who joined since the publishing of the last issue) to NYFOA and thank them for their interest in, and support of, the organization:

Name

Chapter

Bill Bond WFL

Mark Brackett NAC

Michael Buil AFC

William and Scott Manley Curran SFL

David DoBell SOT

Andy and Pamela Ernst WFL

Michele Gennarino WFL

Kristin and Yishai Horowitz SOT

Josh and Thomas Kirkey WFL

Gerard and Diana Lenzo SOT

Marianne Patinelli-Dubay and Brian Dubay NAC

Michael Rater AFC

Carol Weidemann and John Edmunds AFC

David Wilson SOT

. . . leading the way in rural and urban forestry

Management Plans ~ Timber Sales

Wildlife Management

Boundary Line Maintenance

Arborist Services

Timber appraisals

Tree Farm Management

Timber Trespass Appraisals

Herbicide Applications

Forest Recreation & Education

We take pride in providing hands-on, comprehensive rural and urban forestry services geared toward obtaining your goals and objectives.

Have Pioneer Forestry become your long term partner.

Fax (716) 985-5928

less than sugar maple). It is also quite unstable, both when drying, when it will commonly warp/cup/bow/twist/crook etc., but also in service, when exposed to fluctuations in temperature and/or humidity. Its volumetric shrinkage in drying is 14.6%, which is on the high side, and its ratio of tangential to radial shrinkage is 2.3:1, resulting in internal tension that manifests as boards refusing to remain flat once milled.

Another major cause for elm’s instability is its tendency to grow with spiral, interlocking grain. As opposed to the tree’s fibers growing parallel to its centerline, as is the tendency of a well-behaved species like ash, elms are predisposed to have their fibers spiral around the stem, and also to change direction periodically, spiraling one way and then the other, leading to the ‘interlocked’ nature of the grain. If you have ever tried to hand-split elm firewood, you are all too well acquainted with its incredibly stubborn grain. I’ve gotten a second wedge stuck in an elm round while trying to free the first one, and even a third one trying to free the

first two. It’s not fun, and a word of advice: definitely keep your fingers out of a partially split round when trying to retrieve a stuck wedge, as it will clamp down with tremendous force if it gets the chance (don’t ask how I know this). Speaking of firewood though, elm is actually a pretty decent choice, generating about 20 million Btu/cord (comparable to black cherry). You just want a hydraulic log splitter for the job. Trust me. Due to the interlocking grain, and its propensity for the grain to

tear out, elm is a poor choice for either carving or turning. As its lumber is shock resistant, with good elasticity, and bends easily while resisting splitting and splintering, elm was once commonly used for hockey sticks, archery bows, and wagon hubs. It was also commonly used in chair making, both for seats and various steam bent parts. I’ve used elm mostly for small projects, and some utilitarian things like the handrail I mentioned above, and a portable vise for cutting tenons or dovetails in wide boards (Figure 9). Unfortunately, the constantly changing grain direction makes handplaning elm near impossible, especially on its quartersawn faces (perpendicular to the growth rings); a well tuned and freshly honed plane will take fine shavings, but it is ultimately an exercise in frustration, as portions of any board will always end up with badly

continued on next page

torn grain, or at least a fuzzy feeling end product. Sanding and/or scraping are the way to go for this reason, but elm will always have somewhat of a coarse texture due to its open pores and grain structure. An interesting thing I immediately noticed with elm is that even when unfinished its wood tends to have a natural luster, sometimes known as ‘chatoyance,’ due to the way its shifting grain captures light. The open grain can be filled before finishing, but then you lose the natural iridescence. Elm takes glue well, holds nails and screws firmly without splitting, and takes finishes well if the surfaces are as well prepared as possible.

Elm has negligible rot resistance, so is suited for indoor/protected use only, though interestingly if kept constantly wet it will resist decay, which led to it being used as a pre-copper/galvanized/PVC era material for water piping and troughs. As it resists wear well, elm was commonly used for barn floors, where sharp hooves and horseshoes would quickly degrade a less durable wood.

Freshly cut elm has a very pronounced and distinctly rank odor, leading to the

colloquial name of ‘pisselm,’ which doesn’t quite capture it but is honestly not too far off the mark. Thankfully the odor largely dissipates once the wood is dry. I can detect a hint of it lingering in my airdried stash, but you really have to get your nose up close. Once finished, it is odorless.

Back when elm lumber was more abundant, about 2/3rds of it went for for boxes and crates, furniture, and vehicle parts (back in the day when car bodies were actually made of wood), but according to Lumber and its Uses, published in 1914, elm at that time was used for at least 70 distinct categories of consumer products. Elm lumber grown here in New York is almost non-existent in the marketplace today. It is so marginal that it is not

Figure 7. Elm endgrain, magnified. Note the distinctive pore arrangement in the dark/wide latewood section of each growth ring.

even listed on the DEC’s Stumpage Price Report. I don’t know of any supplier in my area (Southern Tier) that sells it, or whether there is any demand for it. I imagine that most of the elm that is culled during timber stand improvement harvests ends up as either pallet wood or firewood, or is simply left in place to rot. True to its nature, in my woodlot, elm is still hanging around in my lowest lying stand that is bisected by a small stream, and the younger trees are growing rapidly. Not surprisingly, there are none in my upland stands. The largest specimen, which was likely the ‘mother’ tree for all of them, and was about 22” DBH, was growing right next to the creek bed, and was seemingly flourishing until 2010, when it sadly made an abrupt and rapid decline before dying a year or so later (Figure 10). I milled that one up with my chainsaw mill, and am still slowly working through the

large stockpile of lumber from that one majestic tree. The wood has some slight discoloration from the fungal damage, but I find it to be beautiful anyway, at least partially because of the uniqueness of its grain patterning, but more so because of its scarcity today, and its storied past. An

additional legacy from this tree came a few years later, when I found a number of morel mushrooms growing in close proximity to its stump; dead or dying elms have long been known by mycology buffs to be prime hunting grounds for morels.

If you know of a grand old elm in your neck of the woods, consider paying it a visit, as I think they are vastly underappreciated today, in an out of sight, out of mind kind of way. And if you’ve got any elms in your woodlot, keep a close eye on them. If their crowns begin to show signs of dieback, consider milling them and using their lumber, as a form of tribute, before they succumb to the ravages of the insects and diseases that have robbed them (and us) of their former glory. If you have any personal experiences milling or utilizing elm lumber, or have any large, legacy elms in your woodlot or on your property, let me know, as I would be interested in hearing about them.

Resources:

Albright, Thomas A., et al. 2020. New York Forests 2017. Madison, WI: USDA, Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Resource Bulletin NRS-121. www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/ pubs/61445.

Fergus, Charles. 2005. Trees of New England. Guilford, CT: The Globe Pequot Press.

Hoadley, Bruce R. 1990. Identifying Wood: Accurate Results with Simple Tools. Newtown, CT: The Taunton Press.

Kellogg, R.S. 1914. Lumber and Its Uses. Chicago, IL: The Radford Architectural Company.

Lassoie, James P. et al. 1996. Forest Trees of the Northeast. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Cooperative Extension Bulletin 235. Meiners, Scott J. Tree by Tree: Saving North America’s Eastern Forests Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Peattie, Donald Culross. 1977. A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Elm zigzag sawfly: https://www.wnyprism. org/invasive_species/elm-zigzag-sawfly/ Silvics of the Forest Trees of the United States:

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ ag_654/volume_2/ulmus/americana.htm Wood Database:

https://www.wood-database.com/americanelm/

Jeff Joseph is the managing editor of this magazine.