The New School's Orozco murals for the next century

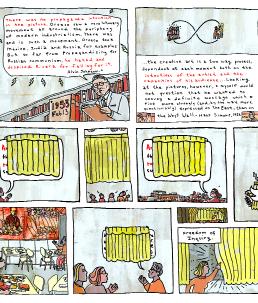

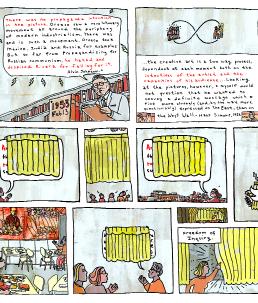

BELOW: Longtime Parsons faculty member George Bates created Red Scare, Yellow Curtain, a graphic narrative of the Orozco mural incident (known as the “curtain hysteria”), for Ofense issen , a 2014 campus exhibition curated by Julia Foulkes, Mark Larrimore, and Radhika Subramaniam. The show explored controversies involving art, identity, and community at The New School. In Bates’ illustrated panel, Alvin Johnson is shown addressing the community, claiming that Orozco had not intended to promote communism by including Lenin and Stalin in his New School mural.

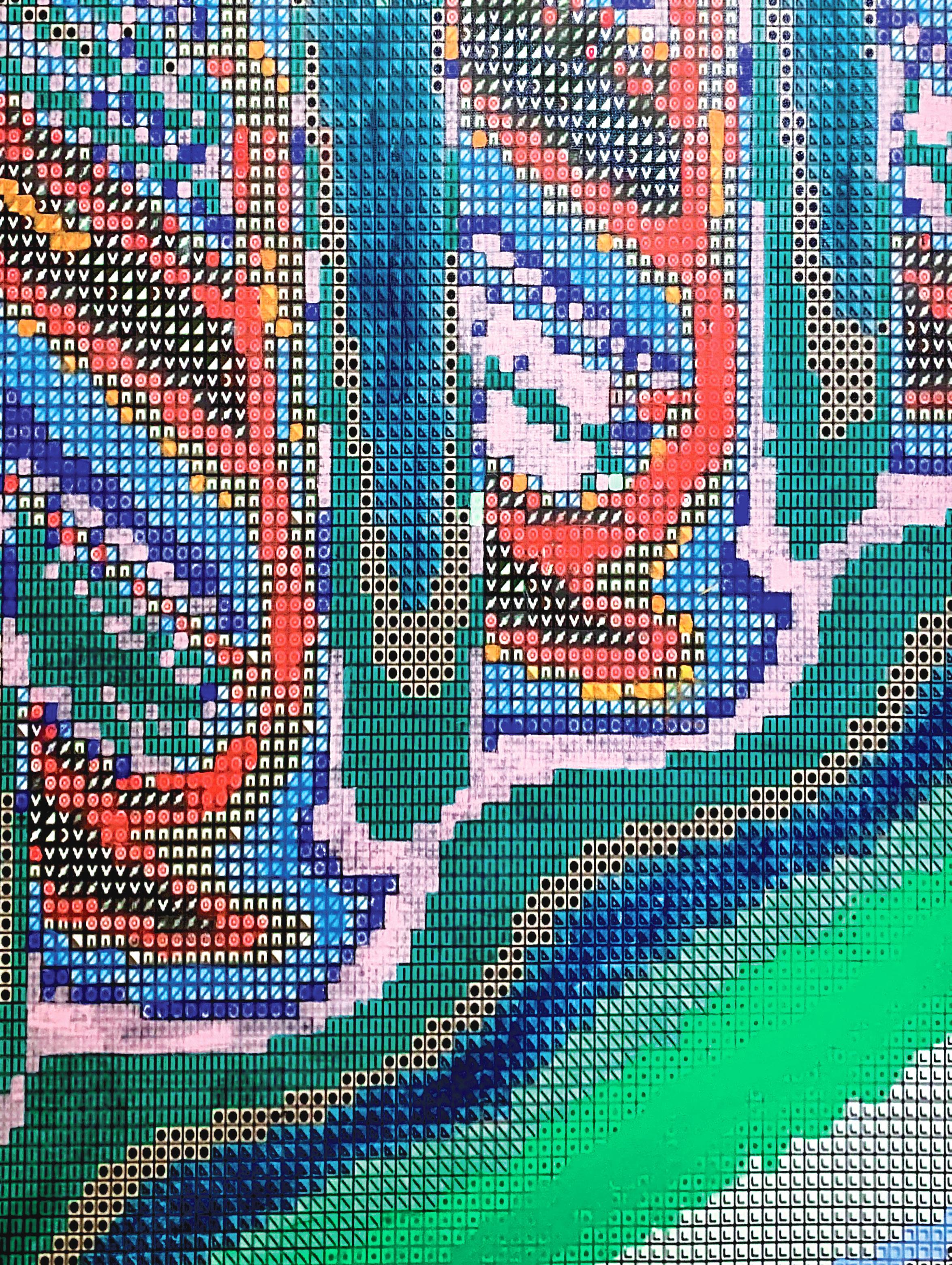

ABOVE: Protests against depictions of Lenin, Stalin, and the Red Army led the school to cover part of the mural with a yellow curtain during the 1950s. In a letter to a New School colleague, Alvin Johnson wrote that he looked forward to “a future date when politics will let art alone.” In a petition signed May 21, 1953, one student said, “You don’t judge a painting by its politics.” BELOW: The Orozco Room was occasionally used as a classroom. Seen here are Orozco’s Ta le of ni ersal Brotherhood (left) and part of Struggle in the Occident (which includes portrayals of Lenin and Stalin) on the right.

Creating Space for Dialogue

The New School’s Orozco murals—masterworks currently being restored and preserved for the future—demonstrate the university’s century-long commitment to art that sparks debate

Arguably the oldest and most important of The New School’s site-specifc art installations are the Orozco Murals, a series of frescoes created by José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949) for the university’s frst permanent home at 66 West 12th Street. One of the “three giants” of Mexican Muralism (along with Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros), Orozco created the works at the request of Alvin Johnson, a founder and the frst director of The New School, who gave Orozco complete artistic freedom in his commission.

Unveiled in January 1931 at the opening of the university building, designed by Joseph Urban, Orozco’s fve-panel Call to Revolution and Table of Universal Brotherhood refects the social and political struggles of his time and addresses themes of justice, equality, and liberation. Four panels surround what was then a student dining room, with the ffth panel located just outside.

Among the fgures appearing in the murals are Lenin and Stalin, whose presence ignited controversy during the McCarthy era. Responding to complaints and fearing vandalism, the school curtained of a section of the

mural in 1953 to hide the Soviet leaders from view. Despite a student petition calling for the removal of the covering, it remained in place until the early 1960s. In the years since, the murals have inspired public conversations on democracy and freedom, including dialogue around exhibitions such as Reimagining Orozco (2010) and Ofense and Dissent (2014).

The frescoes are both historic and rare; they make up one of just three Orozco murals in the United States and are the only surviving sitespecifc frescoes by a Mexican artist in New York City (Rivera’s unfnished piece inside Rockefeller Center was destroyed after clashes over artistic censorship). But the murals have sufered the efects of time and climate change–driven fuctuations in temperature and humidity. Over the years, the university has implemented a number of measures to restore and protect the frescoes, including restricting the use of the Orozco Room to occasional meetings and special events.

Today the murals are undergoing a comprehensive multi-year restoration involving a range of stakeholders, including New School President Joel Towers, an architect who supported the design of a climatecontrol system for the room. Since the university’s founding, fnding innovative ways to address contemporary challenges like climate change has been as important as supporting thought-provoking artists. Preserving these murals will help ensure that they remain part of the cultural conversation for the next 100 years and beyond.

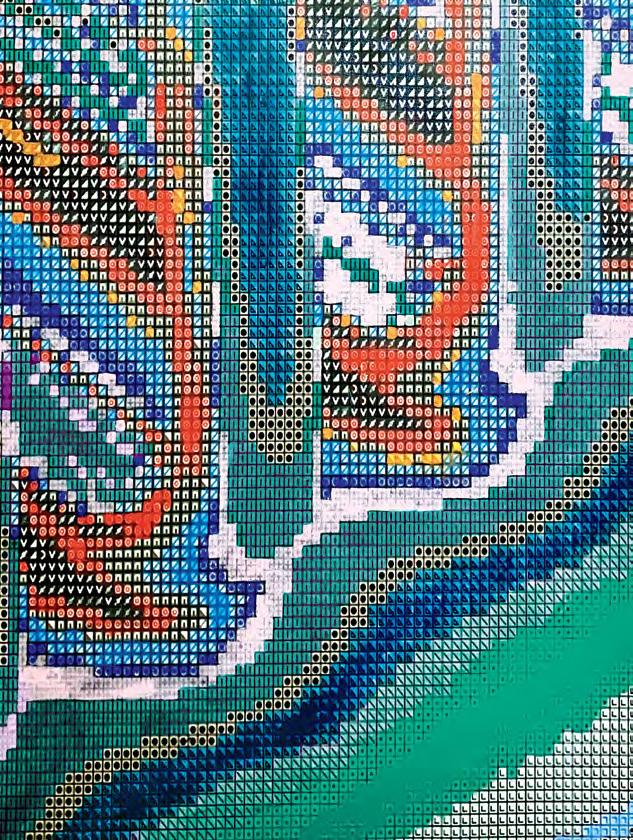

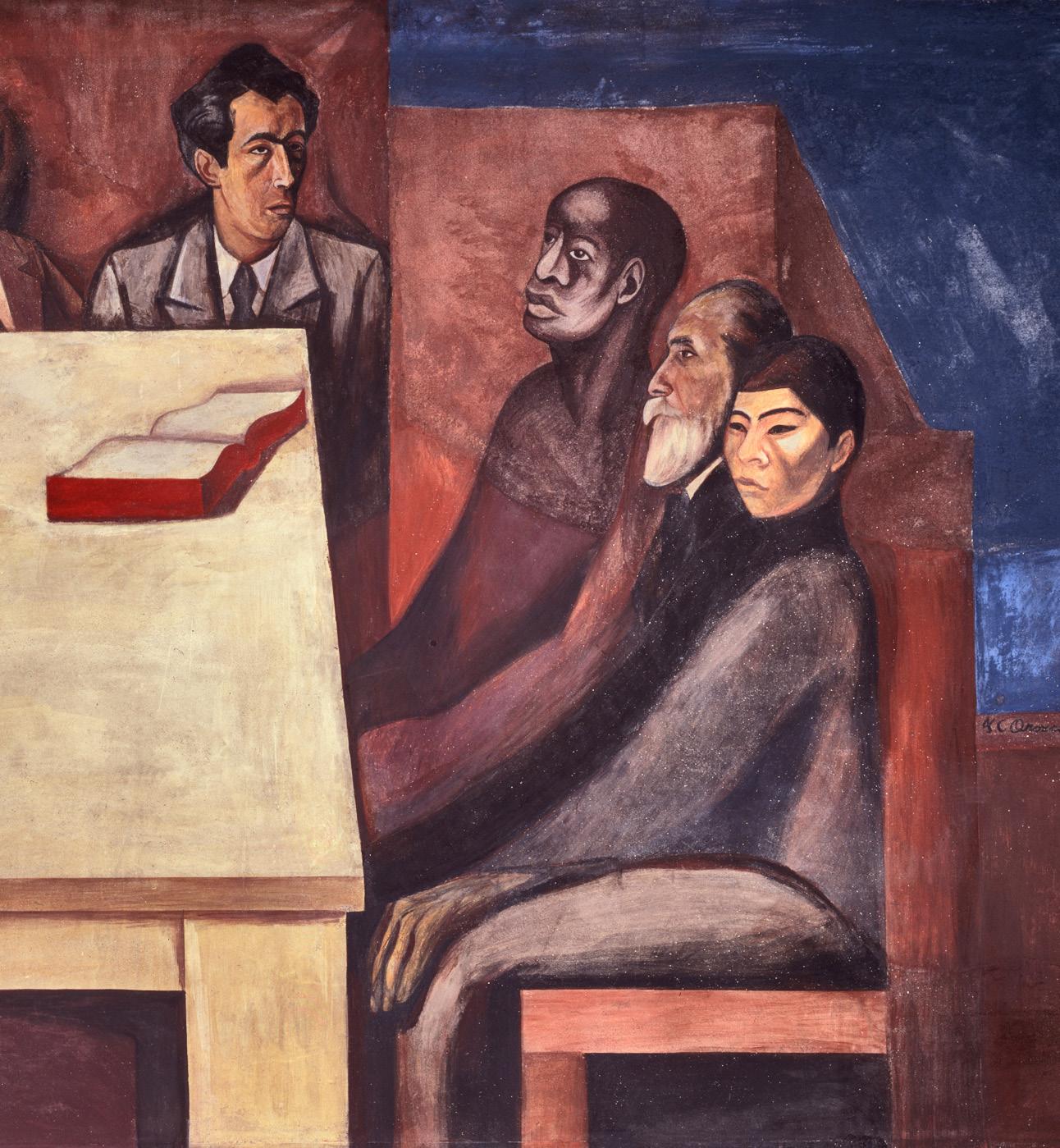

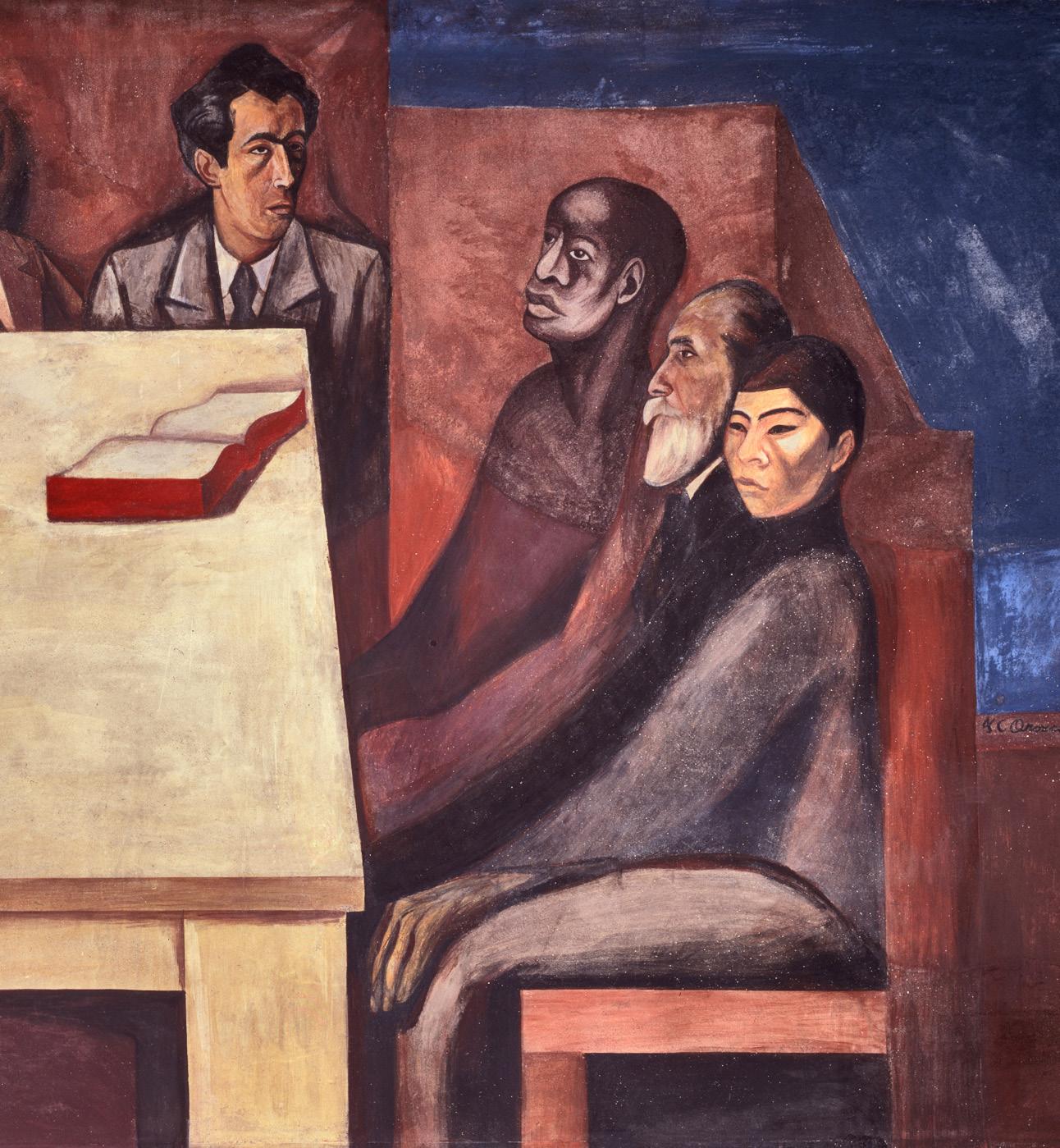

ABOVE: Orozco’s Table of Universal Brotherhood presents a scene of unity among people of difering races, ethnicities, and religions. BELOW: The appearance of Lenin and Stalin in Struggle in the Occident stirred controversy and prompted Alvin Johnson to cover the part of the murals where the two historic fgures appeared. In protest, students formed a committee, calling Johnson’s act “a capitulation to the forces of darkness” and urging university leaders to reconsider in light of the resulting “dangers to democratic tradition and cultural freedom.” “We will have little democracy, indeed,” said the committee in a letter to the New School Board of Trustees, “if majorities were thus granted dictatorial power.” The committee went on to say that while the curtain remained in place, “there should be continued talk about it; especially should there be widespread discussion about freedoms and democratic values generally” among “classmates with diverse views.” Students proposed the creation of a Forum for Freedom, aimed at “supporting and encouraging student eforts to grasp the reality of democracy in an open exploratory forum.” Such an efort would help students “learn to live as creative, expanding healthy personalities by drawing upon the resources of fellowship for strength and enrichment.”

ABOVE: Orozco’s Table of Universal Brotherhood presents a scene of unity among people of difering races, ethnicities, and religions. BELOW: The appearance of Lenin and Stalin in Struggle in the Occident stirred controversy and prompted Alvin Johnson to cover the part of the murals where the two historic fgures appeared. In protest, students formed a committee, calling Johnson’s act “a capitulation to the forces of darkness” and urging university leaders to reconsider in light of the resulting “dangers to democratic tradition and cultural freedom.” “We will have little democracy, indeed,” said the committee in a letter to the New School Board of Trustees, “if majorities were thus granted dictatorial power.” The committee went on to say that while the curtain remained in place, “there should be continued talk about it; especially should there be widespread discussion about freedoms and democratic values generally” among “classmates with diverse views.” Students proposed the creation of a Forum for Freedom, aimed at “supporting and encouraging student eforts to grasp the reality of democracy in an open exploratory forum.” Such an efort would help students “learn to live as creative, expanding healthy personalities by drawing upon the resources of fellowship for strength and enrichment.”

Orozco, photographed by Berenice Abbott in 1936. Abbott taught photography at The New School from 1934 through the 1970s, guiding students including Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus. She created the only known image of Orozco in which the loss of his hand, the result of an accident in his youth, is evident.