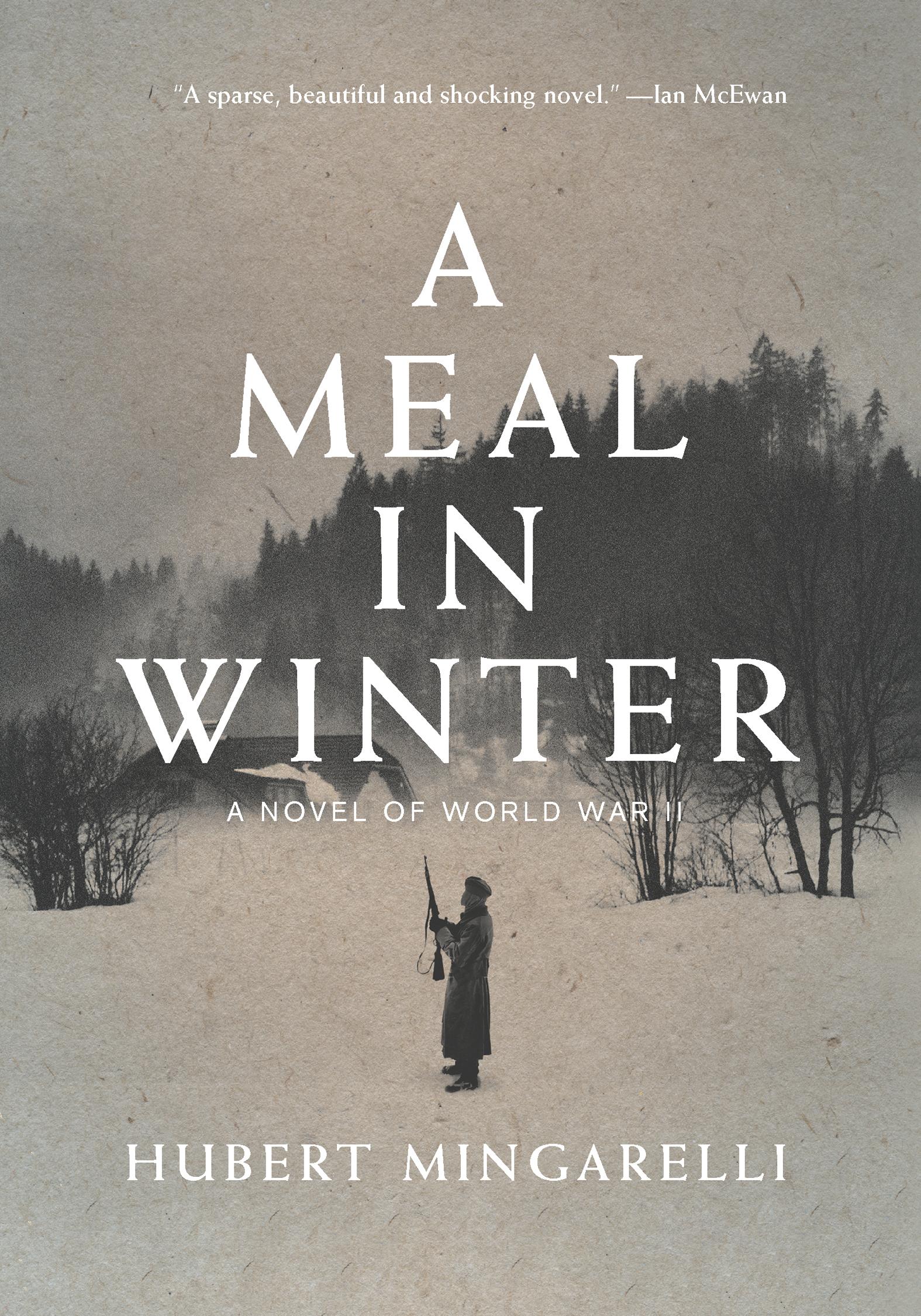

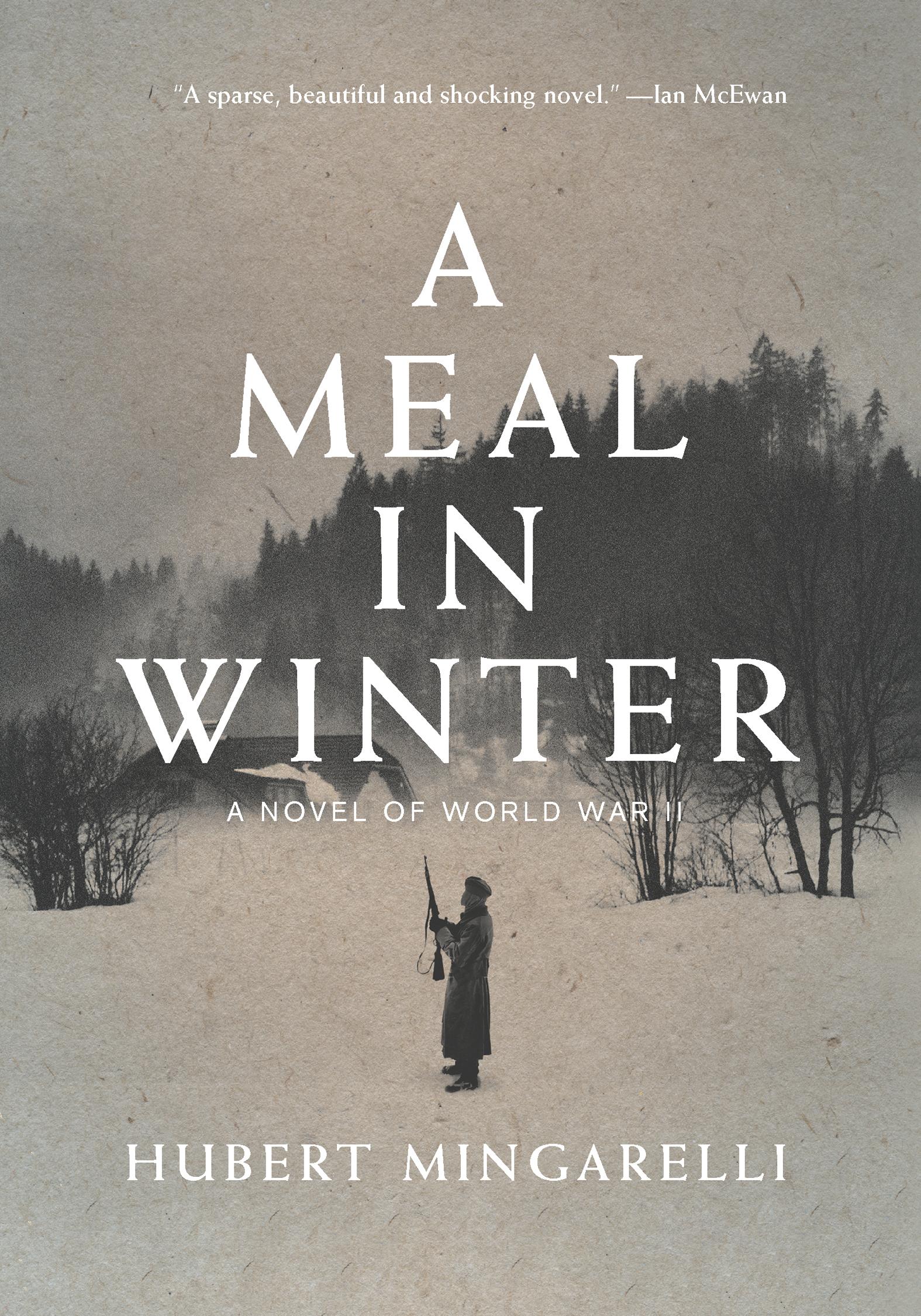

Praise for A Meal in Winter

“Stark and profound. . . . Mr. Mingarelli allows us to see ker nels of genuine sympathy in his soldiers without ever denying the fear and malice they must indulge to do their jobs.” John Williams, The New York Times

“Fine reading, not just for those interested in the war. ”

Librar y Jour nal

“The command of tone and voice sustains tension until the ver y last page of a novel that will long resonate in the reader’s conscience ”

Kirkus Reviews (star red)

“Masterful. . . . Mingarelli offers a new twist on the Holocaust novel. His spare prose, cr isply translated by Sam Taylor, adds to the nar rative’s intensity and keeps you tur ning the pages until its poignant conclusion.”

Huffington Post

“It is profound pages of hor ror and humanity.”

Book of the Year, The Ir ish Times

“Shor t, powerful, vivid, and utterly compelling ”

“Br illiant, devastating, [and] compelling.”

The Jewish Chronic le

Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of The Romanovs

“A luminous tale. . . . The most moving book I have read for a long time ” The Independent on Sunday

“A master piece ” The Independent

“This strong and simple stor y packs a mighty punch ” The Times (London)

“Beautiful and disturbing, complex and sur pr ising. . . . This is not easy for the reader to handle, but Mingarelli knows what he is doing.”

The Herald (Glasgow)

Huber t Mingarelli is the author of numerous novels, shor t stor y collections, and fiction for young adults. His book Quatre soldats won the Pr ix de Médicis He lives in Grenoble, France

Sam Taylor is a translator, novelist, and jour nalist His translated works include Laurent Binet’s award-winning HHhH. His own novels have been translated into ten languages.

A Meal in Winter

A N O V E L O F W O R L D W A R I I

Huber t Mingarelli

Translated from the Frenc h by Sam Taylor

The New Press gratefully ac knowledges the Florence Gould Foundation for suppor ting the publication of this book © by Huber t Mingarelli

English translation copyr ight © Sam Taylor, All r ights reser ved

No par t of this book may be reproduced, in any for m, without wr itten per mission from the publisher. Requests for per mission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Per missions Depar tment, The New Press, Wall Street, st floor, New York, NY .

Or ig inally published in France as Un repas en hiver by Éditions Stock, Par is,

Fir st published in Great Br itain by Por tobello Books, London,

Fir st published in the United States by The New Press, New York,

This paperback edition published by The New Press, Distr ibuted by Two River s Distr ibution

ISBN ---- (pbk )

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Mingarelli, Huber t, –

A meal in winter ; a novel of World War II / Huber t Mingarelli ; translated from the French by Sam Taylor pages cm

“Fir st published in Great Br itain by Por tobello Books, London, . Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, . Distr ibuted by Per seus Distr ibution” Ver so title page.

ISBN ---- (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN ---- (e-book) Soldier s Fiction Impr isonment Fiction Escapes Fiction Jews Poland Fiction I Taylor, Sam, 1970– translator II Title

The New Press publishes books that promote and enr ich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world.These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librar ians; and above all by our authors www thenewpress com

Pr inted in the United States of Amer ica

T H E Y H A D RU N G the iron gong outside and it was still echoing, at fir st for real in the cour tyard, and then, for a longer time, inside our heads. We would not hear it again. We had to get up straight away. Lieutenant Graaf never had to r ing the iron twice. A meag re light came through the frost-covered window. Emmer ich was sleeping on his side. Bauer woke him. It was late after noon, but Emmer ich thought it was mor ning. He sat up on his bed and looked at his boots, seeming not to under stand why he’d slept in them all night.

In the meantime, Bauer and I had already put our boots on. Emmer ich got up and went to look through the window, but he couldn’t see anything because of the frost, so he kept on str uggling to disentangle night from day. Bauer explained to him that it was after noon and Graaf was calling us.

‘What, again?’ Emmer ich g roaned. ‘What for? So we can freeze to death?’

‘Hur r y up, ’ I told him.

‘You’re kidding,’ Emmer ich replied. ‘Why should I hur r y just so I can freeze while I’m standing to attention?’

We felt the same way as him. The whole company did. Why did Lieutenant Graaf need to muster us outside? Wasn’t he afraid of the cold, like we were? We could just as easily have heard what he had to say standing by our camp beds here in the war m. Presumably he didn’t think it was for mal enough, talking to us inside a gymnasium. He’d had a piece of old iron hung from a telephone pole, and we hated the noise it made when it was r ung, that sinister chime, even more than the cold that awaited us outside. We had no choice – we obeyed order s – but all the same, it took courage to go out in weather like that.

We had put on our coats, and wound our scar ves several times around our necks, tying them behind. Next came the wool balaclava. Completely covered except for our eyes, we went out into the gymnasium cour tyard. Bauer, Emmer ich and I were the last ones out there.

We were used to it, we knew what to expect, and yet the cold always came as a shock. It seemed as if it entered through your eyes and spread through your whole body,

like icy water pour ing through two holes. The other s were already there, lined up and shiver ing. While we found our places among them, they hissed at us that we were ar seholes for making the whole company wait like that. We said nothing. We got in line. And, when ever yone had stopped shuffling their feet to get war m, Graaf , our lieutenant, told us that there would be more ar r ivals that day, but late probably, so the work was scheduled for the following day, and that this time our company would be taking care of it. I had the same thought as ever yone else: was that all? Couldn’t he have told us that inside?

Graaf could not tell how it made us feel to know that there would be more ar r ivals that day. He couldn’t see if we were whisper ing behind our scar ves. All he could see was our eyes. And from that distance, he could not yet guess who would repor t sick the following day.

He hadn’t told us how many were coming. He knew it made a difference to us, that it was impor tant. Because if a lot came, he wor r ied that we’d star t repor ting sick that night.

He nodded, tur ned around, and went to the officer s ’ mess.

We could have broken rank now and gone back inside, but we didn’t. We stayed where we were. Earlier, we would

have g iven almost anything not to have to go outside, and yet we waited before retur ning to the war m. Perhaps it was because of the work that awaited us the following day. Or because we were already frozen inside, so a few minutes more made no difference.

Now they were outside anyway, the soldier s in charge of the stove that night took the oppor tunity to fill their buckets with coal. Bauer and I were looking over at the officer s ’ mess because apparently they had a bathtub. We’d been talking about it when the iron sounded. I told Bauer that, in the old days, I’d saved up to have a bathtub fitted. We often used that phrase. We often said ‘in the old days’, par tly as a joke, but not entirely. Emmer ich came towards us. He tr ied not to show us his distress. He had dark r ings around his eyes from sleeping dur ing the day.

We went back inside, and sat on Bauer’s bed. We didn’t talk about the work that awaited us the next day. But because we didn’t talk about it, we felt the pressure of it building inside us.

T H A T E V E N I N G , W E asked to see our base commander. What else could we do? We were able to go over Graaf ’ s head because he’d left to see an acquaintance in town –thankfully, as I doubt he’d have let us do it otherwise. The base commander looked away as he listened to us, his hands fidgeting in his pockets as though he were searching for something. We didn’t hold back when we spoke to him. He was a bit older than us. In civilian life, he bought and sold f abr ic in bulk. It was difficult for us to imag ine that, though, because for us he had always been some sor t of commander.

We weren’t telling him anything he didn’t already know. Occasionally he would glance towards the door, or g ive quick little nods. Not because he was in a r ush, but because he under stood us. We exaggerated a little bit, of cour se. Here, if you wanted an inch, you always had to ask

for a mile. If the cook were to star t being a bit stingy with his por tions, for example, we would have to say that we were star ving to death, otherwise nothing would ever change.

That evening, what we had to say was more impor tant, and our commander gave those occasional nods to show he under stood this. We explained to him that we would rather do the hunting than the shootings. We told him we didn’t like the shootings: that doing it made us feel bad at the time and gave us bad dreams at night. When we woke in the mor ning, we felt down as soon as we star ted thinking about it, and if it went on like this, soon we wouldn’t be able to stand it at all – and if it ended up making us ill, we’d be no use to anybody. We would not have spoken like that, so openly and frankly, to another commander. He was a reser vist like we were, and he slept on a camp bed too. But the killings had aged him more than they had us. He’d lost weight and sometimes he looked so distraught that we feared he would f all ill before we did and that another, less under standing commander would be appointed in his place: someone we didn’t know, or – wor se, perhaps –someone we did know. Because it could easily be Graaf , our lieutenant. He didn’t sleep on a camp bed. He took good care of himself , but not of us. With him in charge,

there would be less coal and more marching. With Graaf , we would be ceaselessly filing in and out of the base. When we thought about this, we could hear the iron echoing from dawn till dusk. It went without saying that we liked our commander, no matter how distraught he was.

As usual, he gave us what we asked for, and we left the next mor ning – Emmer ich, Bauer and myself . We went at dawn, before the fir st shootings. That meant missing breakf ast, but it also meant not having to f ace Graaf , who would be filled with hatred that we had gone over his head. It was still dark, and ever ything was frozen. The road was harder than stone. We walked for a long time without stopping – in the cold air, under the frozen sky – but we weren’t unhappy, in spite of that.

And it was as though I’d lied to the commander the previous evening, because that night, for once, I didn’t dream about our life here. I dreamed that Emmer ich, Bauer and I took a tram together. It was a perfectly simple dream, but extraordinar y for that ver y reason. The three of us were sitting, and around us all was peaceful and – in contrast with most dreams – entirely realistic. There was nothing to suggest it was f alse, that the scene existed only in my mind.

I didn’t tell Emmer ich and Bauer about my dream. I

wor r ied that they would star t telling me about their s. Here, good dream or bad dream, the same r ule applied: better to keep it to your self . In f act, why keep it at all, even for your self?