SF | CPD: CRITICAL CARE

September 2021 | Vol. 21 No. 9 Photo credit: Shutterstock.com

www.medicalacademic.co.za

This article was independently sourced by Specialist Forum.

Tackling harmful chemicals in medical devices

Health Care Without Harm Europe (HCWH-E) is a non-profit network of hospitals, healthcare systems and professional bodies, local authorities, research/academic institutions, and environmental organisations with branches in several countries.

W

CWH-E recently hosted a webinar to make healthcare professionals more aware of the potential danger of harmful chemicals used in medical devices.1

Plastic medical devices: a source of harmful exposure to EDCs Dorota Napieska,

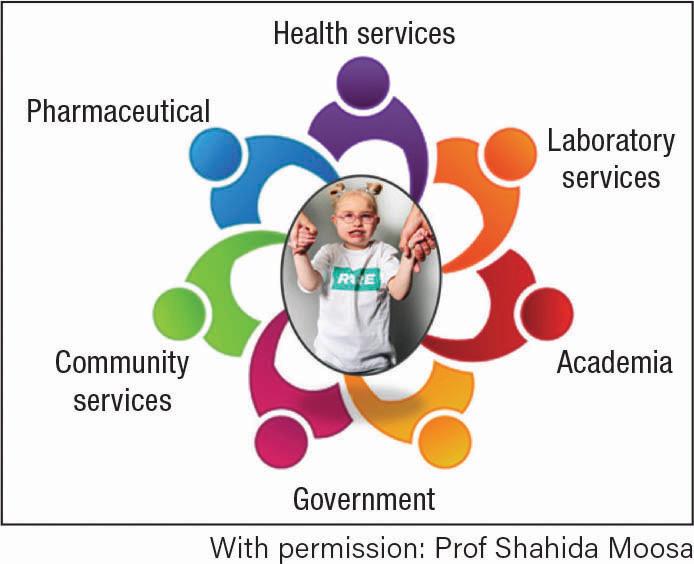

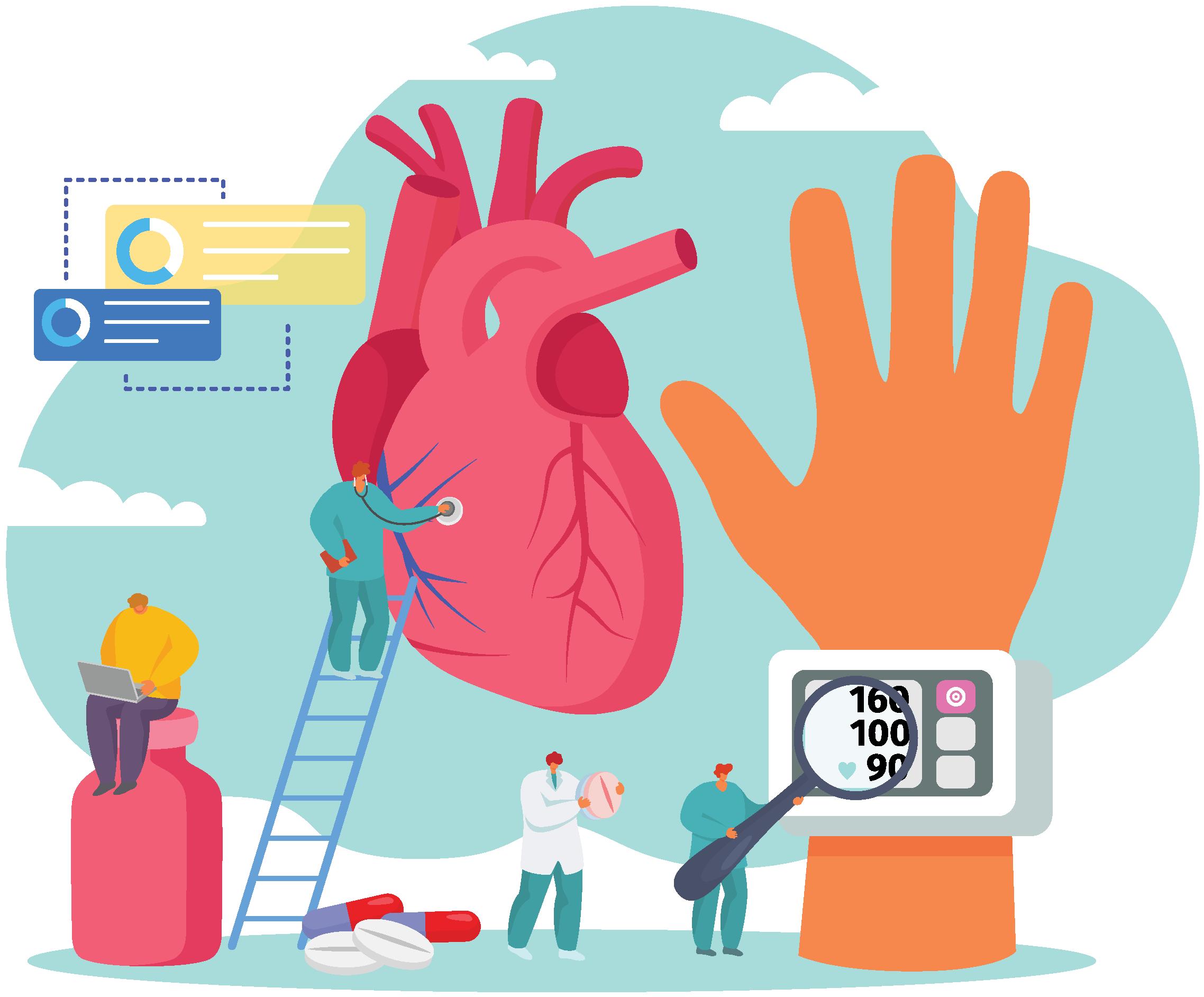

chemicals policy and projects officer, HCWH-E Healthcare professionals rely on medical devices to treat their patients and safeguard their health. Plastic medical equipment and devices can, however, be a significant source of exposure to harmful endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), including phthalates such as di(2- ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) and bisphenol A (BPA).1 Phthalates are often used to make polyvinyl chloride (PVC) flexible, whilst BPA is used to produce certain plastics such as polycarbonates and epoxy resins used in medical devices. These chemicals can harm patients, not only causing infertility and neurodevelopmental issues, but can also undermine the efficacy of treatment. EDCs can impact the human body at very low concentrations and can combine with other EDCs to produce additive effects.1 In May 2021, the European Union passed legislation that requires medical device manufactures to justify why they want to use oncogenic or EDCs above a certain concentration (0.1% weight by weight) in their production processes. This strict requirement is extremely important, said Napierska, because we know that harmful chemicals – most notably BPA

and DEHP – leak out in medical devices.1 While the role of exposure to EDCs and their harmful impact is well-known in the industrial sector, the role of exposure in the healthcare environment is still under-recognised, she added.1 Over the last few decades, HCWH-E has been involved in several campaigns to raise awareness of the harmful effects of EDCs in medical devices. Despite difficulties to demonstrate a causal link, some associations between EDC exposure and diseases are apparent. Foetuses, children, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and dialysis patients are particularly vulnerable to the effects of these exposures.1 Many alternative substances and materials have been developed in recent years to replace hazardous chemicals used in medical devices. Healthcare professionals can now choose between safer alternatives, or continue to ignore the potential danger to patients, she added.1 Exposure to phthalates or BPA can be minimised by adopting a precautionary approach and replacing medical devices with phthalateand BPA-free devices.1

Exposure assessment of infants following cardiac surgery Dr Elizabeth Eckert,

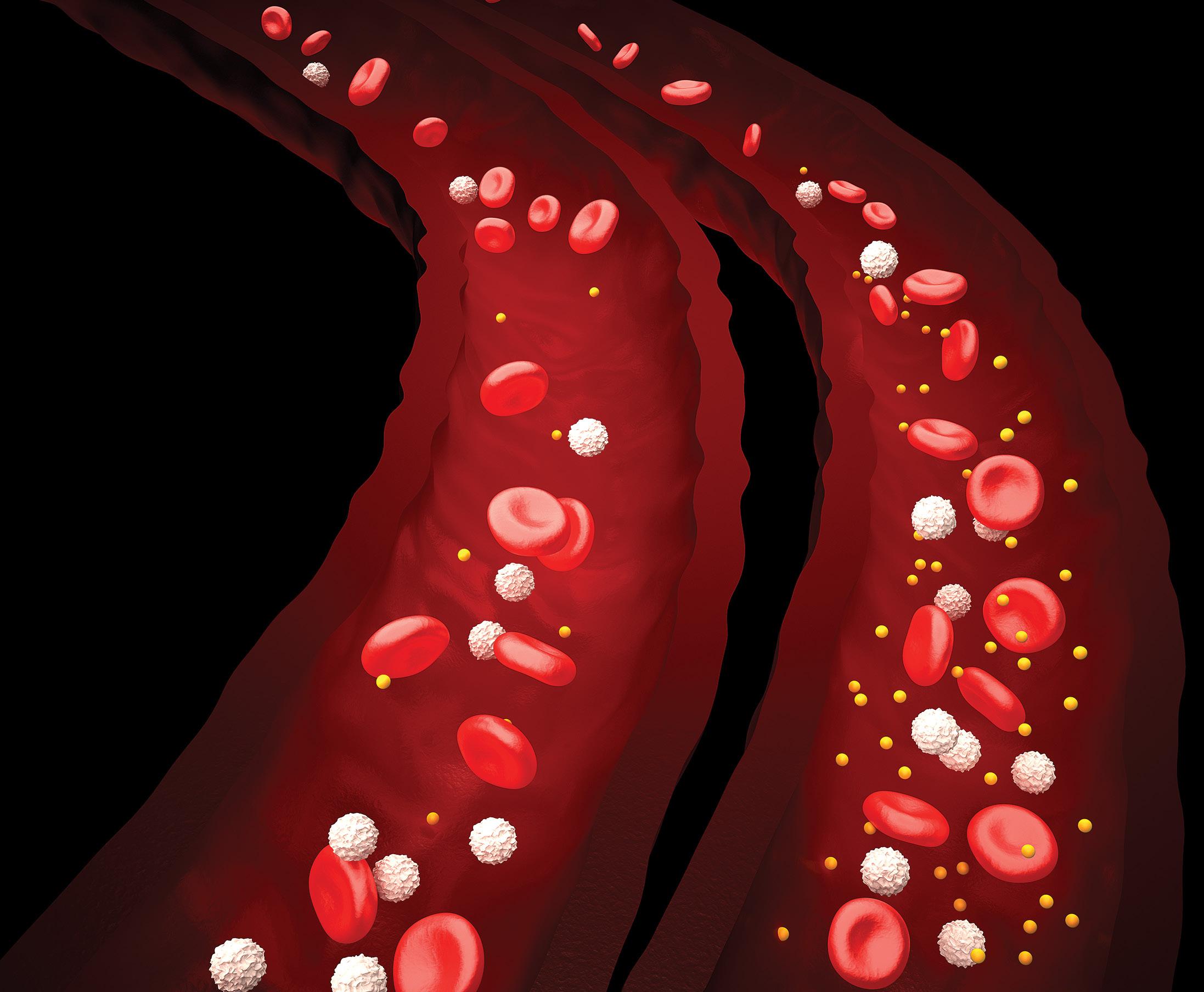

Institute and Outpatient Clinic of Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, Friedrich-AlexanderUniversität Erlangen-Nürnberg (Germany) Plastic medical devices such as tubing, blood and infusion bags, as well as syringes, contain plastic material, which often ranges from 20% to 40% per weight. About 30% of the plastic material contains plasticisers. Plasticisers are not chemically bound to the plastic matrix

To com plete the quiz , go t o w w w . medicala cademic .co.za and clic k on t h e CPD ta b

and therefore, patient exposure due to migration into blood, is possible.1 DEHP is classified as oncogenic and is a known EDC, which has been linked to reproductive toxicity effects. DEHP was banned in the manufacturing of toys and childcare products several years ago, yet it is still used widely in the manufacturing of medical devices widely used in paediatric patients, despite the fact that safer alternatives are available.1 A safer alternative is tri-(2-ethylhexyl) trimellitate (TEHTM) for example. Although there is not as much data available for TEHTM, it has been shown to have a lower rate of acute and chronic toxicity potential compared the DEHP, said Dr Eckert.1 In one of their experiments, Dr Eckert and her team studied the migration behaviour of three different blood tubing sets: PVC material with two different plasticisers (DEHP and TEHTM), and silicone as control material. The tubing sets were attached to a standard heart-lung machine used in cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in children.2 They analysed the total plasticiser migration, the parent compounds as well as their primary degradation products in blood. Additionally, the total mass loss of the tubing over perfusion time was examined.2 They found that PVC tubing plasticised with DEHP had the highest mass loss over time and showed a high plasticiser migration rate. In comparison, the migration of TEHTM and its primary degradation products was found to be distinctly lower (by a factor of about 350). Moreover, it was observed that the storage time of the tubing affected plasticiser migration rates.2 In conclusion, the DEHP substitute TEHTM

45