15 minute read

Case series: Frosted branch angiitis

Frosted branch angiitis: A rare blinding vasculitis in three children presenting acutely to Red Cross Children’s War Memorial Hospital…unmasking possible mumps-associated sequelae in the unvaccinated?

N Narainswami, FCOPH (SA), MMED (UKZN), Dip Oph (SA), Dip HIV Man (SA), MBBCH (Wits); Fellow Paediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5495-7153

N Freeman, MB ChB (Stell), FC Ophth (SA), MMed (Ophth) (Stell); Consultant, Paediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1110-9795

T Seobi, MBBCH (Wits), MMED(Wits), FCOphth(SA); Consultant, Paediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7125-4217

Corresponding author: N Narainswami, e-mail: neerannarainswami@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Frosted branch angiitis is a rare clinical entity with less than two hundred and fifty cases described in the literature. This report seeks to describe the clinical features and management of this devastating retinal vasculitis presenting in three children under five years of age to Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital (RCWMCH) just weeks apart.

Materials and Methods: Observational case report of three patients.

Case report: Three otherwise healthy children presented within the space of one month (May -June) to our eye clinic with a history of sudden, painless and profound vision loss post a flu-like prodrome a few weeks prior. An extensive infective and inflammatory work up proved negative except for positive mumps serology in one patient with an antecedent history of mumps. None of the children were previously vaccinated against mumps. Despite initial limited and poor response to aggressive systemic steroid therapy, escalation to infliximab infusion therapy seems to be assisting visual recovery in all three patients.

Conclusion: Mumps-associated retinal vasculitis can present as a devastating blinding disease. With the concurrent surge in ‘epidemic parotitis’ in South Africa and the absence of any other aetiologic factor other than mumps proven on serology it is possible that these cases may represent a spectrum of complications in unvaccinated children especially under the age of five years. The possible diagnosis of mumps- associated retinal vasculitis carries a significant public health concern needing to be highlighted and addressed by our health care sector. This is especially critical as there is currently no mumps vaccine freely available in the state sector in South Africa. Consideration of re-instituting the mumps vaccine may have to be undertaken to mitigate consequences in young children.

Keywords: frosted branch angiitis, retinal vasculitis, vaccine, epidemic parotitis, mumps.

Acknowledgements: Department of Neurology RCWMCH, Department of Virology RCWMCH, Dr J Steffen Department of Ophthalmology Groote Schuur Hospital, Dr W Huwaidi Registrar UCT Ophthalmology, Dr H Kassa Department of Rheumatology RCWMCH.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Ethical considerations: Written informed consent was obtained from the parents for use of clinical data and images.

Case Report

Three previously healthy boys from the Western Cape ranging from two to four years presented within the space of one month to the eye clinic at Red Cross Children’s Hospital with a history of sudden painless blindness post flu-like symptoms a few weeks prior.

Case 1: A three-year-old unvaccinated child from Atlantis, presented with profound bilateral painless loss of vision of PLP/? NPL OU without navigation.

Case 2: A four-year-old child from Hout Bay with a history suggestive of mumps including parotid swelling that was treated at home conservatively a few weeks prior. Vision was HM OU with limited navigation.

Case 3: A two-year-old from Athlone presented a week later with bilateral PLP vision with poor navigation.

None of the children lived in the same district and there was no travel history nor any other contributory history to account for a common environmental exposure.

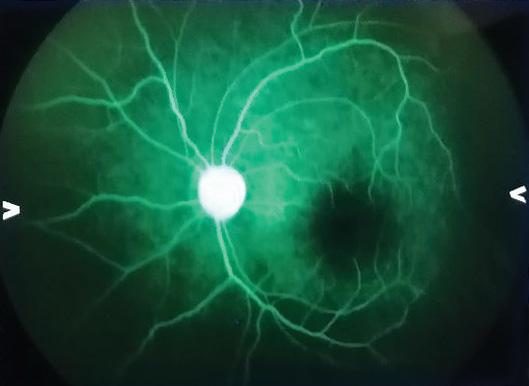

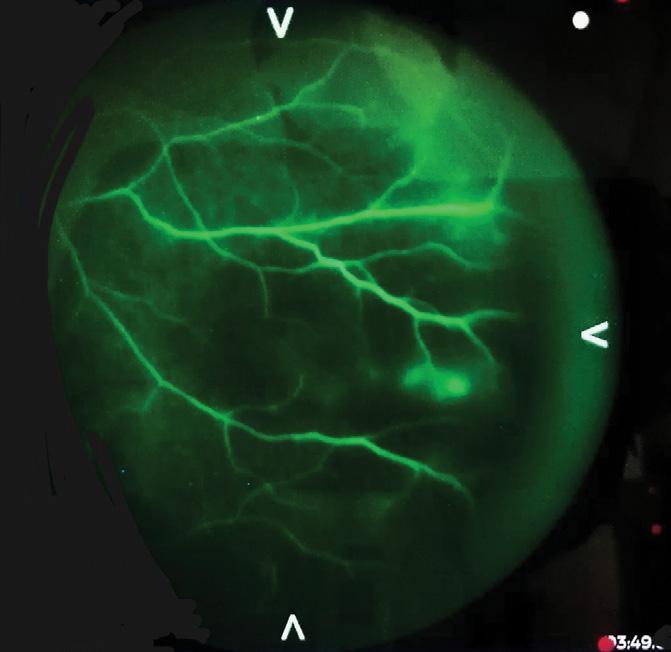

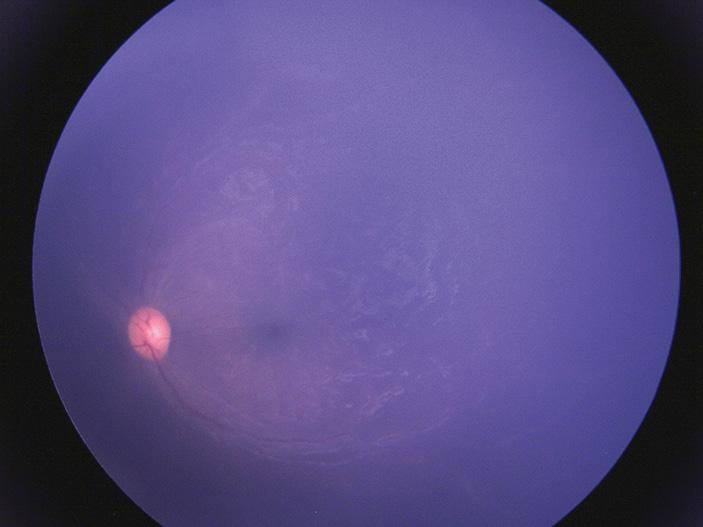

All three children presented with profound bilateral vision loss and limited navigation. Pupil reactions were sluggish in all three children. They were otherwise systemically well. Further examination of the anterior segment was unremarkable in all three. Dilated fundus exam revealed a striking frosted branch angiitis picture with severe vascular sheathing, relatively minimal vitritis and a punctate retinitis in the mid to peripheral retina in the first two cases. The third and youngest child had marked vascular sheathing falling short of being described as frosted branch, but with a similar punctate retinitis extending into the posterior pole. No occlusive disease was clinically evident in all six eyes of three cases. All three had diffuse retinal oedema with associated macula oedema. Optic discs were pink without any disc swelling.

Infective work-up including HIV testing, TB Mantoux, CXR and TB gene expert were all negative as were TORCH screenings. Covid nasal PCR was negative in all three cases. Nasopharyngeal swabs for respiratory viruses (RSV/Coronavirus/adenovirus) were non-contributory. Inflammatory markers (ESR/CRP/ENA panel) were all within normal range and an extensive autoimmune panel (SLE/Bechets/neuro-sarcoid) in each child turned up negative. MRI brain and orbits were within normal limits for all three boys with no evidence of a cerebral vasculitis nor demyelination.

The first two children were commenced on intravenous (IV) acyclovir for at least 24 hours prior to an IV pulse of methylprednisolone of five days duration. This was to empirically cover for any possible herpetic cause of vasculitis while awaiting infective work-up. Serology for syphilis, toxoplasmosis, HSV, VZV, CMV, Rubella, anti-streptolysin O were all negative. Mumps serology, which is not routinely available in state service, was also deemed necessary due to the parallel mumps outbreak in South Africa. Only one swab in Case 1 was positive for rhinovirus, but rhinovirus is not associated with retinal vasculitis. Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis revealed an absence of cells on chemistry and all three children were negative for viral (HSV/CMV/VZV/ mumps) PCR and VDRL testing. Post IV pulsing the frosted branch picture showed dramatic resolution on fundoscopy, but no concurrent visual gains were seen in the first month. Electrophysiologic testing revealed markedly diminished activity in all three cases. Clinically, there appeared to be narrowing of some of the retinal vessels in all three children with stippling hyperpigmentation in the periphery as vascular sheathing and retinal oedema resolved. We decided to test vitreous fluid and perform fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) to correlate our clinical findings and assess if there was any viable retina worth salvaging in each child. FFA showed a remarkably well-preserved retinal vasculature with normal calibre vessels and no occlusive vasculitis nor stasis despite the initial striking funduscopic signs. Macular perfusion was good in all three cases and no capillary drop out was noted. The last child to present (Case 3) showed some late leakage from temporal retinal vessels at the watershed zone. A trial of intravitreal triamcinolone acetate was given in one eye of Case 1 with the poorest baseline vision to assess response.

Vitreous tap specimens were negative for viral (HSV/VZV/CMV) PCR including mumps. All three children remained on gradual oral prednisone taper over four weeks. Visual gains however seemed to lag and remained underwhelming. Case 1 remained light perception with poor projection and navigation a month post intravitreal steroid injection. Intraocular pressure in the injected eye increased in comparison to the fellow eye but was controlled adequately on antiglaucoma drops.

Case 2 with antecedent history of mumps also showed a marked improvement in vasculitis activity with no leakage on FFA. At one month his vision was PL with assisted navigation. He was able to confidently pick up large high contrast objects presented to him and but unable to recognise faces of family members.

Vision in the third case also improved to navigating independently though he remained unable to identify high contrast optotypes at one month.

At this point mumps serology was positive (both IgG and IgM) in one child (Case 2).

At two months post presentation there was no further appreciable visual improvement, despite improvement in inflammatory activity. Further multidisciplinary consensus determined that an escalation to a trial of IV immunemodulatory therapy (infliximab) was a reasonable treatment option. The attendant complications of cataract and glaucoma made continued steroid therapy unfeasible beyond two months. The delayed presentation coupled with the improved ocular inflammatory activity on steroid therapy made the diagnosis of a post-infectious immune hypersensitivity phenomenon most likely.

One month after the first infliximab infusion there was an improvement in vision noted with all three cases able to navigate independently and Case 3 able to identify and pick up large silver balls. The decision was made to complete three doses of IV infliximab and commence oral 5-7.5mg weekly methotrexate after the first infusion as well as to continue low dose oral 5mg oral prednisolone maintenance. Visual gains in all three cases were noted after each infliximab infusion with vision in all three cases improving dramatically to at least 6/24 (identify and pick up 100s and 1000s) after the third infusion.

Discussion

Mumps is a viral infection caused by a paromyxovirus, a member of the Rubulavirus family.1 Commonly affecting children under ten years it usually runs a mild and self-limiting course.1 Older children and adults can also be uncommonly affected. Mumps infection in childhood generally confers lifelong immunity. Ocular manifestations of mumps are rare but well documented with acute dacryoadenitis being the most common finding followed by optic neuritis, though this is usually in the setting of a meningo-encephalitis.2,3

Frosted branch angiitis (FBA) is a rare clinical entity with less than 60 known cases in the world literature and only a few attributable to mumps.4 Primary (idiopathic) FBA presents as a florid translucent retinal perivascular sheathing of both arterioles and venules (though typically a predominant periphlebitis and variable vitritis. It has a variable course, typically affecting young children as low immunoglobulin levels at this age is postulated to be inadequate to suppress an immune response to any number of infectious agents. Secondary FBA occurs in the setting of ocular and systemic viral or auto-immune disease. CMV retinitis in the setting of HIV is a classic example with CMV known to have a tropism for endothelial cells. The deposition of antigen-antibody complexes, as is also seen in auto-immune disease such as SLE, is thought to incite a vasculitis. The frosted branch picture that is sometimes seen in leukaemia and lymphoma is due to infiltration of actual malignant cells.

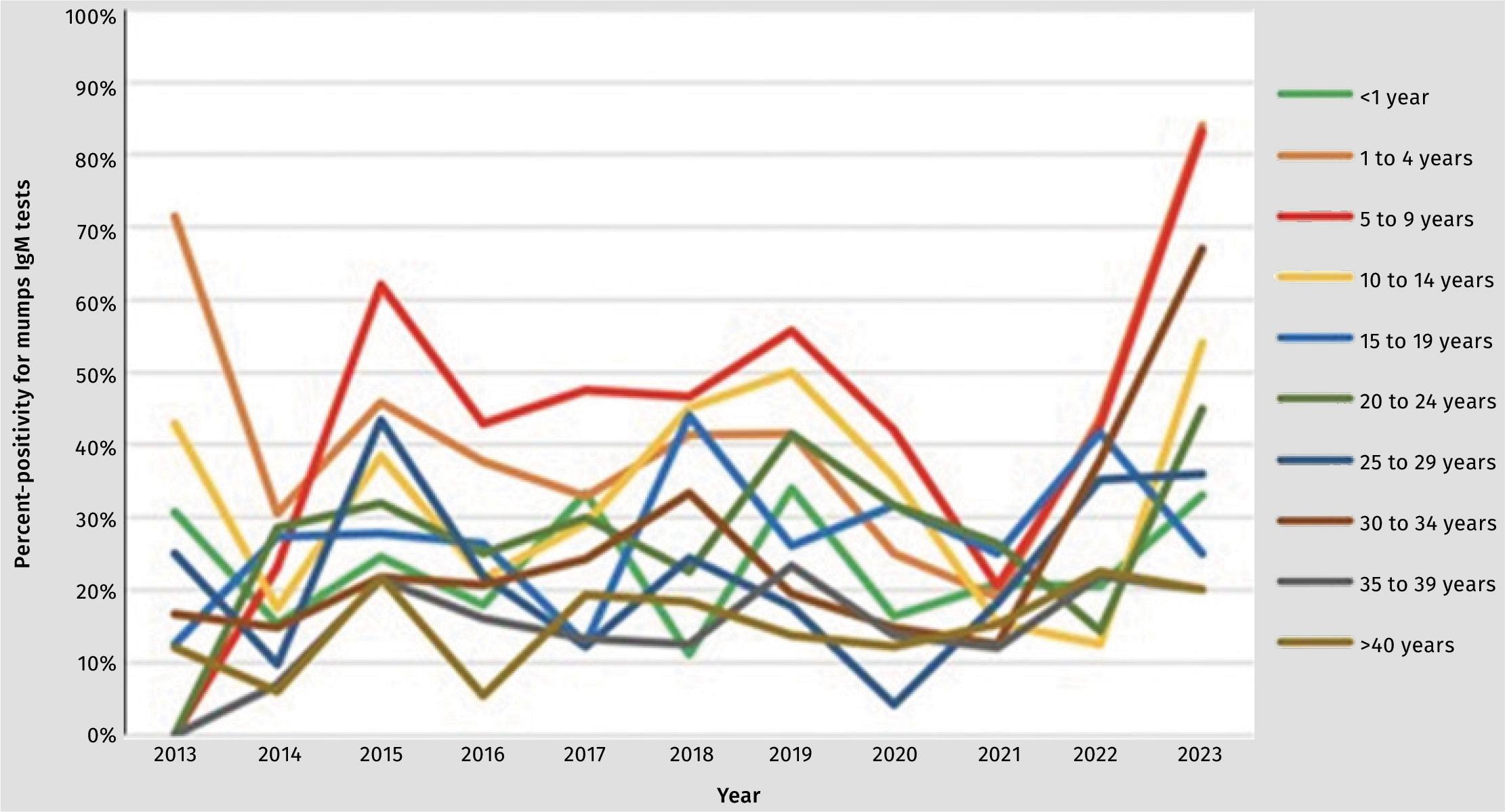

Following the reports of clusters of mumps outbreaks earlier in February this year, the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) of South Africa confirmed an outbreak on 11 May 2023 with the annual percent positivity for mumps IgM reaching 69% (prior having peaked at 39% in 2019).1 Annual percentpositivity for mumps IgM tests by age category shows marked increases in percent-positivity in the one-four-year age category (84% in 2023) and the five-nineyear age category (83% in 2023), followed by the 30-34-year age category (67%) and 10-14-year age category (54%) (Figure 1).1

All three children presented during the same period that South Africa recorded its highest ever percent positivity for mumps IgM testing in the under five-year age category. Case 2 had parotid swelling in keeping with clinical signs of mumps. While immunisations were up to date for all three children, none received the mumps vaccine as it is no longer part of the extended programme for immunisation (EPI) in the state sector and is only available in the private health sector in South Africa.1 None of the parents had been aware that the EPI no longer offered mumps vaccine coverage.

There is no known standard of care for FBA. Systemic corticosteroid therapy has been employed in most cases of primary FBA with documented improvements in anatomic and functional outcomes.6-8

With exceptionally few isolated case studies on mumps-associated vasculitis in the literature,6,7 a multidisciplinary approach was deemed necessary to guide therapeutic interventions. The negative viral (mumps, VZV, HSV, CMV, rubella) PCR results on vitreous tap sampling in all three children coupled with positive IgG mumps serology in one child, seem to support an underlying immune-mediated response to an inciting antigen in the eye rather than the presence of ocular infection. This finding has been suggested in earlier case reports.2,8 The delayed onset of vision loss following the flu-like symptoms in two of the three cases also supports the concept that the immune mediated response may cause the vison loss and not the virus itself.

Only one child (Case 2) had positive IgG and IgM serology for mumps. All three children were immune competent. Serological methods and test kits for mumps vary considerably in their sensitivity and specificity with some immunofluorescent assays detecting as few as 12%-15% of confirmed mumps cases.9 A negative mumps PCR in blood, nasopharyngeal swab and vitreous fluid does not exclude the diagnosis of mumps as the virus does not linger beyond few weeks post infection.9 This is important when considering FBA as an immunemediated sequelae of mumps infection as it does not require the detection of mumps via PCR testing to consider the diagnosis.

Bilateral neuro-retinitis post mumps with subsequent vision loss has been reported in at least six cases with improved visual acuities to normal or near normal in most cases.6-8 The pattern in our three patients is however different with there being an overwhelming retinal vasculitis with punctate retinitis and no features of optic nerve involvement clinically. The MRI imaging also showed no ON involvement. Also contrary to the few anecdotal cases in the literature initial visual recovery in our patients was underwhelming from PL vision to PL vision with some projection after intravenous steroid pulsing.6,10 Sayadi et al reported the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in managing mumps-associated retinal vasculitis in a child with notable improvements in visual activity.3 This modality of treatment is unfortunately not readily available to the public health sector in South Africa.

One eye of one child (Case1) with PLP/ NPL vision was injected with intravitreal triamcinolone but showed no gain in vision post injection. Intraocular pressure did however elevate but was well controlled on topical agents. With minimal visual recovery after two months of oral taper of prednisone, the decision was made to escalate to a trial of infliximab infusion therapy to assess response in visual recovery. This was new unchartered territory in terms of treatment being guided mostly by a few anecdotal case studies and no large evidence -based trials. Infliximab, a chimeric mouse/ human monoclonal anti-TNF antibody, was chosen based on its suggested effect for treatment of refractory childhood uveitis including juvenile idiopathic arthritis and its relatively low rate of treatmentending adverse events.11,12 Notable visual gains both subjectively and objectively were evident in all three cases with each successive infliximab infusion.

Conclusion

Primary frosted branch angiitis can present as a fulminating blinding vasculitis.14 South Africa was in the grip of a mumps outbreak as confirmed by NICD in May 2023. All three children were unvaccinated against mumps. Positive mumps serology in the absence of any other systemic or ocular cause seems to suggest that these cases represent an immune-mediated response to the mumps virus in the unvaccinated.

While a novel or as yet unknown infectious agent cannot definitively be ruled out, this seems unlikely in the face of a parallel mumps outbreak.

Careful consideration by all stakeholders may need to be taken into possibly re-introducing the mumps vaccine as part of the immunisation schedule in South Africa.

References

https://www.nicd.ac.za/confirmation-ofmumps-outbreak-south-africa-11-may-2023/.

Walker S et al. Frosted branch angiitis: a review Eye 18,527533@0 04 eye, 18257-5333.

Sayadi J, Ksiaa I, Malek I, Ben Sassi R, Essaddam L, Khairallah M, Nacef L. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for MumpsAssociated Outer Retinitis with Frosted Branch Angiitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2022 May 19;30(4):1001-1004. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1841243. Epub 2021 Feb 5. PMID: 33545017.

Hedayatfar A, Soheilian M. Adalimumab for treatment of idiopathic frosted branch angiitis: a case report. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2013; 8(4): 372-375.

Neri P, Aljneibi S, Pichi F. Rescue Treatment with Infliximab for a Bilateral, Severe, Sight Threatening Frosted Branch Angiitis Associated with Concomitant Acute Onset of Presumed Dermatomyositis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022; 8: 1-5. doi:10.1080/09273948.2 022.2057333

Khubchandani R, Rane T, Agarwal P, Nabi F, Patel P, Shetty AK. Bilateral Neuroretinitis Associated with Mumps. Arch Neurol 2002;59(10):1633–1636. doi:10.1001/ archneur.59.10.1633.

Ali A, Ku JH, Suhler EB, Choi D, Rosenbaum JT. The course of retinal vasculitis. The British journal of ophthalmology. Jun 2014;98(6):785-789 George RK, Walton RC, Whitcup SM,2Nussenblatt RB. Primary retinal vasculitis. Systemic associations and diagnostic evaluation. Ophthalmology. Mar 1996;103(3):384-389.

Rosenbaum JT, Ku J, Ali A, Choi D, Suhler EB. Patients with retinal vasculitis rarely suffer from systemic vasculitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. Jun 2012;41(6):859-865.

Rota JS, Rosen JB, Doll MK, McNall RJ, McGrew M, Williams N, Lopareva EN, Barskey AE, Punsalang Jr A, Rota PA, Oleszko WR. Comparison of the sensitivity of laboratory diagnostic methods from a wellcharacterized outbreak of mumps in New York City in 2009. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013 Mar;20(3):391-6.

Dorairaja T, Yuen GS, Rahmat J. Idiopathic Frosted Branch Angiitis In Paediatric Patients: Case Series. Ijmms. 2019 May;427-32.

Walton RC, Ashmore ED. Retinal vasculitis. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol Dec 2003;14(6):413-419.

Abu El-Asrar AM, Herbort CP, Tabbara KF. Retinal vasculitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. Dec 2005;13(6):415-43.

Levy-Clarke GA, Nussenblatt R. Retinal vasculitis. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. Spring 2005;45(2):99-11.

Rodriguez A, Calonge M, Pedroza-Seres M, et al. Referral patterns of uveitis in a tertiary eye care center. Arch. Ophthalmol. May 1996;114(5):59.

Hughes EH, Dick AD. The pathology and pathogenesis of retinal vasculitis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol Aug 2003;29(4):325-340.