how can therE be now if therE was no then

Jesse Lee Kercheval

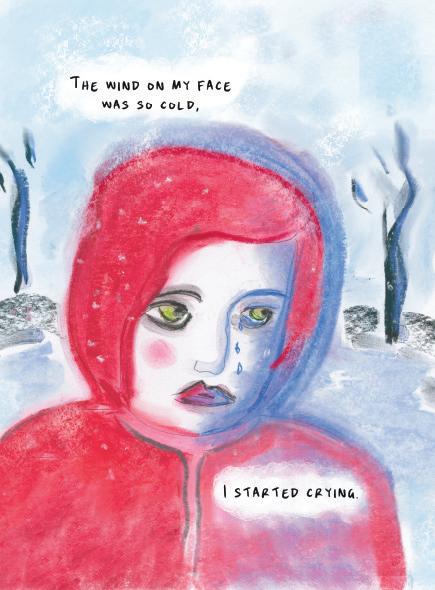

After a sleepless night, I am drawing a self-portrait. My face, barely visible in a sea of aqua waves. My hair is orange, so is my skin, my lips. My eyes the same unnatural aqua as the sea.

February 1, 2024, 7 am, I write on the drawing and, I feel like I am drowning.

I am drawing because, in my part of the art world, February 1 is Hourly Comics Day. People sketch what they do throughout the day (and sometimes night). Drink coffee, then drawing themselves drinking coffee. Then, hour by hour, they post their diary comics on social media for all the world (or an interested subset of the world) to see. I have been looking forward to doing it again this year. It is crazy. It is fun.

But today, I have Covid for the second time, so my day is officially both Hourly Comics Day and a Sick Day.

8 am. My second drawing.

I have a terrible cough, I write on the page above my hair.

Every one of my twenty-four ribs ache.

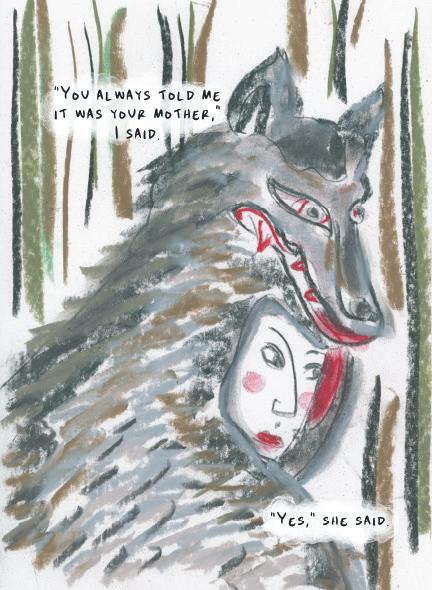

By the time I was six, I already knew the word “amnesia.” This is in the long-ago days of only three television networks, each with their interchangeable detective shows, Westerns, medical dramas. I knew about amnesia because, sooner or later in those series which my family watched together every night, a leading actor was bound to get it. Amnesia was their fate.

They would be hit on the head, then wake up bandaged, rescued by a distressed, often blond young woman. This happened when they were away from home for some reason—think cattle drive, think long drive where your car goes off a mountain road. Then the lead actors slipped into new lives, in a kind of radical freedom from everything that came before. They fell in love with the possibly blond woman, became essential to the survival of whatever community they had unexpectedly joined, until they arrived at the point of marriage, to committing themselves to the kind of life they could never have back in the main plot of the series.

Then the hovering threat apparent in the blond beloved’s eyes arrived. A villain, well-armed. A ragged army of them. Or sometimes a natural disaster, that weak dam bursting, threatening to wash them all away.

The lead actors always saved the girl, saved everyone. But also always at the price of hitting their head a second time. And, as we all knew, that was the sure-fire cure for amnesia. They would wake up and see their beloved only as a pretty, now weeping, stranger. Remember nothing that had just happened in the episode we watched except that they were late returning to their regularly scheduled lives.

Then, amnesia was a TV trope. Now it’s the way we live.

In March 2020, I was drawing myself, too. As a monster. As a blond little girl tumbling from the sky looking a bit too much like the Little Prince. I had never drawn before in my life, but the pandemic meant I was locked down in Montevideo, Uruguay, and when my hands were not shaking with fear, scared to touch the buttons in the elevator without hand sanitizer, I drew.

I know what was happening in those first days because I have the drawings. I drew my one house plant, a stem with two leaves I named Vera. Everything else that was green was 10 stories below in a world that was closed to me. I drew a couple dancing the tango on the roof of the even taller building across the street, a roof with no railings dangerously high in the air.

I drew a brick wall—and felt I was banging my head against it. The drawings are evidence. I also wrote essays, writing about all this. They appeared in magazines. Editors wrote asking for more. People in the world beyond where I could not go, borders closed, airports shut, read them, commented on them.

Now, no one wants to reread them, to know they ever existed. I don’t blame them. I don’t want to either.

9 am. Me, again.

Write: I tell myself I just need more coffee. Orange or aqua again, both unnatural, decidedly not normal colors. Because, really, what is normal about this? About drawing while quarantined on the third floor of my house, trying not to give Covid to my daughter who has asthma. She spent the pandemic working in Japan, four years always masked, and has just returned to the U.S. She has not had Covid yet. This time, I feel sicker than the first time though still within the range of “sick day at home,” not “sick enough to be in the hospital.” But I know that might change, so always there is this orange prick of fear, this aqua drip-drip-drip of dread.

This the way we live now. If I mention to someone that I have Covid, they either say, Oh I just got over Covid. Or, Oh everyone I know has Covid right now. But no one says more than that, no listing of parents who died, or friends with long Covid. No recounting of the strange years we spent in that pandemic life we fell into like a blow on the head.

And the amnesia is eerily collective. No real news about Covid other than an occasional article about how a study has

shown something like exercise helps with long Covid, followed by another that speculates exercise may make it worse. I know in the local news tomorrow, on February 2nd, the fact that Jimmie the Groundhog, Wisconsin’s homegrown weather mammal, has or has not seen his shadow and so spring will come sooner or later this year will take up more space than anything about Covid. Bam, that blow on the head. We have new lives now. New loves.

But today, I am drawing just what this kind of sick feels like.

10 am. Unable to do anything that requires an actual brain, I watch an old episode of Project Runway. I had forgotten how batty the dresses are.

11 am. I had forgotten how bitchy the designers are.

I feel the déjà vu. This is how I spent a lot of the pandemic. How we all did. In the first half of 2020, Netflix added more than 26 million global subscribers.

12 pm. Back in the aqua sea. I sink into a nap.

That, too, feels pandemic familiar. Working online. Time loose, stretching, sagging. Sleep impossible. Or sleep there, one slow breath away, all the time.

1 pm. I sink deeper. Curious fish, my memories of the pandemic, gathering around me.

I want to stay there. Or at least I want to catch and hold on to one of those fish.

In 2020, when I managed to get an evacuation flight from Uruguay back to Wisconsin, I had my first taste of public amnesia. In Montevideo, we lined up for our flight in a closed, dark airport, masks on our faces. No Uruguayan citizens were allowed to leave so it was me, my husband and some Chilean soccer players who had been playing for Uruguayan clubs. We were going to fly on LATAM, the Chilean airlines, to Santiago de Chile, then on another plane on to Miami. On the plane, the flight attendants, also masked, handed us sandwiches and bottles of water in giant plastic garbage bags, standing as far away from us as it was possible in the aisle of a plane. In Santiago, when we got off, the airport, too, was dark, everything closed.

“Run,” the gate attendant told us, shouting the number of the gate for the flight to Miami. He clapped his hands, “Run!”

And we did. Then we landed in Miami and there was no pandemic. One sign at passport control asked us about Hoof and Mouth Disease (Have you been near horses or cattle?). No one asked us about Covid. No one took the medical forms we had been asked to fill out on the plane. In the airport, everyone was eating and drinking. No one was wearing a mask. It was as if nothing was happening, had happened.

Eventually I made it home to my house in Wisconsin and then I was there, in the house, for two years. Or was it one year? To be honest, I can’t quite remember. I know I drew.

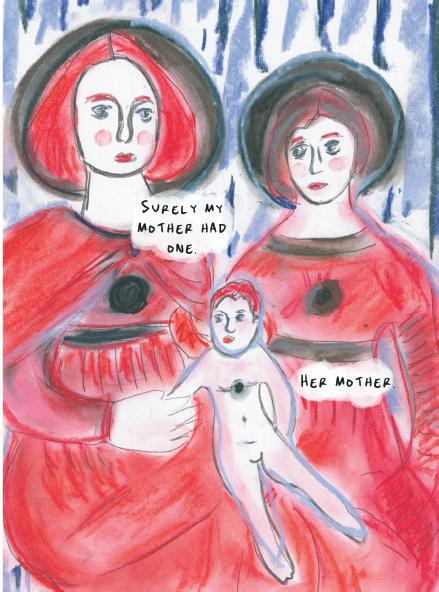

I drew women with wild red hair. My mother always told me women with red hair were not afraid of anything.

I drew women with their mouths open, screaming.

In March 2022, two years after I got locked down in Uruguay, I got my first case of Covid. I’d returned to Uruguay after its borders, closed for the whole two years, opened again. I wore a mask flying down. In Uruguay, I didn’t. And as is the custom, I kissed everyone I saw on the cheek. The Uruguayan friend I was staying with got Covid, too. Maybe we both got it at her birthday party. Maybe at a book fair where she gave a presentation in a tent on a freezing cold late winter night, me shivering in the audience. We both had already had a series of vaccinations. We were not very sick. We stayed inside her house, working on the anthology

of Uruguayan women poets which had been on pandemic pause since the lockdown in 2020.

I called COPA, the airline I was flying on, and told them I had Covid. They asked me to get a letter from a doctor saying I had Covid, so my friend asked her cousin to stop by after her practice closed. She talked to me through the fence, then passed me a note written on her prescription pad. I took a photo of it and sent it to the airline. They moved my flight forward. No charge. It was still that moment in the pandemic. Of course, the airline did not want someone with Covid on the plane, that was more important than charging me to change my ticket. It was the last moment of anyone feeling that way.

When I was better, I flew home.

This second time, I was pretty sure I got Covid renewing my driver’s license at the DMV. Or maybe it just seemed like the place all the contagions in the world go to take a number and sit next to each other, coughing, in yellow plastic chairs. At any rate, it made a good story. It made me not responsible for getting sick. I had to go to the DMV. I needed a driver’s license. Then again, that is early pandemic thinking. No one thinks like that anymore. No one tries to figure out where they were exposed or who exposed them. It just happens.

I got it. I’d already had it. I will undoubtedly have it again. A friend, who teaches kindergarten, told me she’s lost count of the number of times she’s been sick. Another has been sick every single day for four solid years.

2 pm. I tell myself I feel better.

A month ago, as part of switching doctors, a nurse called for a telehealth screening. She recited a list of five common words, then had me repeat them back. “At the end of this conversation,” she said, “I am going to ask you to repeat them again for me.” We talked for thirty minutes, going over my medical history. Then she asked me for the words. I said, Apple, river, clock, green

And then—I stopped. I could not remember the fifth word.

“I’ll give you a hint,” she said. “It’s a part of your body.” I still could not remember.

“Face,” she said. I shook my head. No moment of, Oh, of course, face!

“No, not face,” I said.

“Yes, yes, it was.” I knew she must be right. But I felt, strongly, irrationally, she was lying to me. “That’s alright,” she said. “Forgetting one or two words is normal.”

If forgetting is normal, is amnesia normal, too? National amnesia? Global? Name the last five years. Oh, you forgot two! Never mind, totally normal.

3 pm. How could I forget face? I draw mine.

My mouth tastes like an old penny.

I am taking Paxlovid this time and every sip of water is orange rust.

I was married once before, very young. After I got divorced, every few years the phone would ring, and it would be my exhusband. He would have seen something I wrote in a magazine. Or found something he thought was mine. He would run through a set speech about how no one was at fault in our divorce. How we had both been too young. I didn’t disagree. But the odd thing was that whenever this happened—and it happened for decades—I never recognized his voice. Not when I answered, not during the entire phone call. I always found myself thinking, This is someone pretending to be my ex-husband.

Surely, that was a form of amnesia. How can you not recognize a voice you heard nearly every minute of a marriage that lasted three years? Like with the word “face,” had his voice somehow never moved from short term to long term memory? And so disappeared without a trace? Or had I just hit myself, hard, over the head and willed the memory away?

Because I didn’t want him to call me. I didn’t want to remember being married to him at all. I wanted him to be the episode of Big Valley where Jared got that inevitable blow to his head. I wanted him to be the pretty blond girl or the menacing villain I could not remember after I returned home to my real life. And surely that is what we are doing now. There was a different life. A villain. Bam, now they are gone. *

5 pm. Me, trying to stop coughing. My head feels like a too tight shoe.

6 pm. Me with a bathtub of soup. I fix my family dinner.

7 pm. I watch an old episode of the Great British Bake Off, the reality TV opposite of Project Runway The bakers are as sweet as the cakes

Now, when I travel, in the U.S., to Italy, Chile, China, or France, there always comes a moment as I am leaning over a coffee or tea or glass of wine with a friend when they tell me about their pandemic. They whisper to me, as if it were our secret. Their voices trail off as if the memory were fading already. I nod as they speak. It happened, I am saying. It happened to me, too.

I should have kept a diary, one of them said to me. I should have written it all down, another. I keep nodding but honestly, I am also shrugging. Sometimes, by then, they are, too. Because I did write it down. I wrote it. I drew it. It doesn’t seem to matter.

But I am writing and drawing about it, damn it, one more time. I want to remember it. I want someone somewhere in the future to know what it was like.

I am fighting to stay awake but losing. I am still coughing but with my eyes closed.

8 pm. I fall asleep. I dream I am on Project Runway wearing a freshly baked cake.

9 pm. I sleep and dream I am back in the ocean surrounded by fish.

10 pm. I catch the fish that is my memories. Hold onto it. I promise myself I will never let it go.

Jesse Lee Kercheval is the author of 18 books, including the graphic memoir French Girl (Fieldmouse Press, 2024), the poetry collections I Want to Tell You (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2023), Un pez dorado no te sirve para nada (Editorial Yaugurú, Uruguay, 2023); the short story collection Underground Women (University of Wisconsin Press, 2019); the memoir Space (University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), winner of the Alex Award from the American Library Association; Brazil (Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2010), winner of the Ruthanne Wiley Memorial Novella Contest; Cinema Muto (Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), winner of the Crab Orchard Open Selection Award; The Alice Stories (University of Nebraska Press, 2007), winner of the Prairie Schooner Fiction Book Prize; and The Dogeater (University of Missouri Press, 1987), winner of the Associated Writing Programs Award for Short Fiction.

She is also a translator, specializing in Uruguayan poetry. Her translations include: Love Poems/ Poemas de amor by Idea Vilariño, (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020) and The Invisible Bridge/ El puente invisible: Selected Poems of Circe Maia (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015).

She is the Zona Gale Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.