The Griffin

A student-led publication.

Introduction

The Humanities Corner

To What Extent Does Language Shape Thought and Perception?

- Amira Alsayed

Entropy and God

- Annabelle Minnis

Albert Schweizer: Anatomy of a Polymath

- Mr Harman

Vanished Without a Trace: The Enigma of the Roanoke Colony

- Oliver Wilson

Hesiod: The Father of Greek Mythology

- Tabitha Blackmore

The STEM Corner

The Role of Colonisation and Imperialism in Shaping Global Economic Systems

- Louise Adiukwu

Should We Be Worried about Super-Gonorrhoea?

- Dr Martin

A Brief Introduction to Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity

- Ned Broderick

Science in the DC Universe: The Lasso of Truth

- Chidera Maduka Agbeze

Welcome to the first edition of The Griffin! This is a student-led journal, published at the beginning of every half-term, which hopes to provide a platform for students, staff, and alumni to write about absolutely any topic that interests and excites them. This half-term’s publication includes a vibrantly varied selection of entries, ranging from exploration of ’Entropy and God’, to discussion of ‘Super-Gonorrhoea’; hopefully, something to pique everyone’s interest!

I would like to extend a huge thank you to all of those who wrote an article – this would not exist without you! It would also be remiss of me not to give special thanks to Tabitha, Mr Harman, and Mr Goulding, all of whom were massively helpful in the editorial process.

If you – students, alumni, staff, or parents – are interested in contributing to the next half-term’s edition, please get in contact at: maximilian.pietrzak@newhallstudent.co.uk

I am particularly hopeful that students younger than the Sixth Form will get involved next time, so please do not hesitate to register your interest.

Any feedback on the journal is also warmly welcome and encouraged – it is your opinion that matters!

I hope that you enjoy your reading of the articles! Max.

To What Extent Does Language Shape Thought and Perception?

Amira Alsayed, Y13.

On the surface, language functions as a method of communication, yet the influence language has on our perception and understanding of the world extends far beyond just interactions linking with philosophy, linguistics, and psychology. The SepirWorf Hypothesis, also known as language relativity, argues that the language unique to the individual plays a significant role in their perception of the world. By examining an individual’s culture, ethics, and the conceptualization of time, it becomes clear that language plays a significant role in thought and perception rather than acting as a framework for communication.

With around 7,000 languages in the world, the phenomenon of communication becomes increasingly fascinating. Not all of us are able to communicate in the same way and so, theoretically, one culture could be more limited by their language in terms of worldview compared to another culture. An example posed by Lera Boroditsky, a cognitive scientist and author of 7,000 Universes, shows that even when discussing the same idea, speakers of different languages will not be able to make sense of it in the same way. Boroditsky uses the example of telling a friend about a time you went to visit your aunt on her 53rd birthday - through the analysis of different languages it becomes clear how they shape the perception of this example. If the conversation was spoken in Mian (one of the 800 languages spoken in Papua New Guinea) the verb alone would be indicating the specific time frame of the party; an Indonesian translation, however, would give no indication of time. In Mandarin, the noun referring to the aunt would distinguish whether it was an aunt from the mother’s or father’s side. Interestingly, the Amazonian dialect Pirahã does not have words for exact numbers. There would, therefore, be no way express that the aunt was 53 years old. From this, it seems plausible to assume that our lives are shaped by our mother-tongue and perhaps, therefore, those who have been raised in a bilingual manner will have a broader conceptual understanding of the world.

The notion that language influences how we conceptualize time seems uncanny at first. Upon analysis, however, it has become clear that language is integrated with societal and cultural norms, and therefore we tend to take an emic approach when considering such concepts. With the specific example of time conceptualization, the link with language seems farfetched, mainly because it is not something we would even question, yet research into the link between writing direction and space mapping would suggest otherwise. Although time is not a tangible concept, the use of spatial metaphors in everyday language proves that there is a link between the two. For example, in English, common phrases such as ‘the holidays have flown by’ shows how the English language maps time on a horizontal spatial axis. This concept explains how individuals map out past and future events depending on the direction of their writing. Most languages write from left to right, but languages such as Taiwanese use a top-down method of writing whilst Arabic and Hebrew natives will write from right to left. This raises the question of whether Arabic and Hebrew speakers perceive past-to-future events in a way English speakers might

consider "backwards", but measuring something as intangible as time remains challenging.

A study conducted by Bergen and Lau looked at comparing Taiwanese and Mainland Chinese participants, who share a language and cultural background but differ in writing direction. The aim was to isolate the effect of writing orientation on spatial-temporal mapping. The participants were given black and white images depicting the growing process of a living thing, e.g. an egg, a chick, and a chicken, or a baby, a toddler, and an adult. The researchers found that the Taiwanese participants placed the images from earliest to latest in a manner of top to bottom whilst the Mandarin participants placed the images from left to right. Having questioned the implications of such spatial mapping it seems the way people visualize time can significantly affect their daily experiences, decision-making processes, and interactions with others. Ultimately, this research highlights the importance of considering linguistic and cultural frameworks when examining cognitive processes, offering valuable insights into the interplay between language, culture, and thought.

There seems to be a link between morality, ethical decision making, and the language used. When first coming across this problem, it seemed that the link between morality and language was emotion. From personal experience, I can attest to the fact that the emotion of language is stronger in one’s mother tongue than a language learned later in life. For example, getting told off in English always seems that bit more formal compared to my mother telling me to do something in German.

Essentially, this is known as the modern foreign languages effect (MFLE) which posits that when a native language is used, there is a greater emotion attached and so arises a tendency to follow deontological based ethics. Using research carried out by Boaz Keysar, Sayuri Hayakawa, and Sun Gyu An, it demonstrates how the MFLE works in ethical situations. When participants were presented with the ‘trolley dilemma’ (where they had the choice either to let the train kill five innocent people or they could pull a leaver to send the train down a track that would only kill one person) it became apparent that when the dilemma was presented in a foreign language, participants were more likely to choose the utilitarian and less emotionally invested decision than when they were asked in their native language. The fact that many were more willing to choose to kill one initially 'safe' person intentionally suggests the lack of emotional understanding when working with a foreign language. This indicates that thinking in a foreign language can create psychological distance, reducing emotional bias and leading to more rational decisions. Sayuri Hayakawa highlights importance of the point at which the foreign language was learnt as this could have serious implications on the emotional availability of the person. Hayakawa argues that if a child learns a foreign language, they are far more likely to develop an emotional connection with the culture and tradition. Therefore, this child in adolescence may feel they are able to make the same rational decision in response to an ethical dilemma whether it be in their native or foreign language. Thus, the relationship between language, emotion, and morality is complex and varies based on personal language experiences.

To conclude, it seems as though language is far more than a tool for communication, clearly shaping the way we perceive and interact with the world. From influencing our understanding of time to guiding moral and ethical decision-making, it is language that intertwines with culture, thought, and emotion in complex ways. The examples of linguistic relativity, as seen in the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, Boroditsky’s research, and studies on the modern foreign language effect, demonstrate that the languages we speak shape not only our worldview but also our emotional responses. Ultimately, the importance of considering linguistic diversity when examining human thought processes is highlighted, as it reveals that our minds are moulded by the languages we use, and perhaps even by the languages we have yet to learn.

Entropy and God

Annabelle Minnis, Y13.

Murphy's Law states that ‘Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.’

This isn’t due to the planets misaligning or some mysterious cosmic force working against you, it is simply entropy at work. The second law of thermodynamics tells us that entropy – the measure of disorder in a system – is constantly increasing. Put simply, the universe tends to move from order to chaos. For instance, if you build a sandcastle, over time the wind and tides will disperse it into a random collection of sand particles. This is because there are always more disorderly variations than orderly ones. It is true that the wind could move the sand to form the exact variation of sand particles you once formed, but in reality, the odds are astronomically higher that the sand would disperse into a random clump.

This concept has implications beyond mere physical processes. The teleological argument for the existence of God posits that the complexity and order of the universe point toward purposeful design, suggesting an intelligent creator. However, the second law of thermodynamics poses a challenge: if the universe was created with perfect order, why does it naturally tend toward disorder?

If we logically reversed this process of entropy and moved back in time, entropy would decrease, and the level of order would rise. The entropy at the moment of the universe's inception has been calculated at 10^10^123 – a number so vast that it is nearly impossible to comprehend. This level of precision challenges the idea that the universe's beginning was the result of random chance. The finely tuned nature of the universe suggests purposeful design.

Yet, the question remains: why would a perfectly ordered creation possess an intrinsic tendency toward chaos and decay? Some suggest that this reflects a kind of ‘freedom’ built into the universe, mirroring the concept of human free will. Polkinghorne presents a ‘free process’ theory whereby the universe doesn’t just operate through strict, deterministic laws but also contains an element of openness or indeterminacy. Others argue that the universe's movement toward disorder is part of a divine plan, where the current decay will ultimately be reversed or renewed, either through metaphysical means or divine intervention at the end of time.

The law of entropy forces us to reconsider the relationship between order, disorder, and divine design. Could the inherent chaos in the universe be a feature, not a flaw, of its creation? And if so, what does this tell us about the nature of the creator?

Albert Schweizer: Anatomy of a Polymath

Mr Harman, Teacher of Theology.

Whereas genius often wears the convincing disguise of single-minded, unalloyed intellect, the greatest polymaths remind us that this must not come at the cost of conscious action. Einstein described Schweizer’s life and work as a “shattering example of what can be achieved by one who unreservedly sets his heart and mind and soul upon a noble purpose”. Planted neatly at the end there are several unfashionable notions which nonetheless inform polymathy greater than any other: heart, mind, soul, and nobility.

A physician, a musician, and a theologian. Far from being the incipit to a bar-based gag, these three professions describe the one man, born in Alsace (my favourite region of France, with particular emphasis placed on its food, wine, and the fact that it is essentially Germany) who commanded a life and legacy befitting of a Nobel Prize. This portrait of the man will consider three elements of polymathy.

The polymath does not perceive there to be a limit to the number of fields one can master. Schweizer the theologian led the quest for the Historical Jesus, finding satisfying reconciliations between developments in historical criticism and the eternal truths of Christianity. Schweizer the musician became the leading Bach scholar of his time, played the organ to an impressive level, and learned to fix the mighty things where necessary. Schweizer the physician founded a hospital in remote Gabon, to which he brought modern technique and humanitarian zeal. Crucially, Schweizer permitted one discipline to inform the other: his Christcentered ethic inspired his medical advances, and so on.

Secondly, the polymath sees art and music not as a mere hobby but an intellectual end in itself. As mentioned above, Schweizer used music as a means of breaking down the barriers between disciplines: it was spiritual as well as academic, from the mathematics of musicology to the rich theology of Bach’s compositions. Music, and arts generally, are the sustaining forces of polymathy.

Finally, the polymath actions his intellect. Polymathy is not the pursuit of knowledge for one’s own sake, but for others. Schweizer’s time in Gabon fostered a deep sense of moral responsibility which both fed his intellect and demanded recourse. Whereas traditional Western ethics failed to account for the inherent value of all things, Schweizer’s ethic “reverence for life” required a universal respect: all things, he claimed, have a “will to live”. Our greater cognitive ability demands responsibility to this end. The recipient of a Nobel Peace Prize in 1952, Schweizer’s philosophy was a precursor to modern bio- and environmental-ethics. His was a soul which apprehended the raw realities of life; his was a heart which tackled the problem of suffering instead of conceptualising it; his was a mind which exhibited in the most perfect way, cross-discipline mastery. Such are the elements of nobility and, indeed, polymathy.

Vanished Without a Trace: The Enigma of the Roanoke Colony

Oliver Wilson, Y12.

The story of Roanoke Colony, often called the ‘Lost Colony’, remains one of the most puzzling and mysterious chapters in early American history. Established in 1587 by English settlers on Roanoke Island, off the coast of what is now North Carolina, the colony had vanished without a trace by 1590. What happened to the 115 men, women, and children who settled there? Over centuries, historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts have put forth various theories, but the ultimate fate of the Roanoke colonists continues to elude us.

Roanoke Colony was part of England's ambitious plans to establish a foothold in the New World. Sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh, an English nobleman and explorer, the colony was meant to serve as England's base of operations for exploration, trade, and eventual expansion in North America. Raleigh had attempted to establish a settlement on Roanoke Island in 1585 with a military expedition under the command of Ralph Lane, but it had failed, due to shortages and strained relations with the local Indigenous tribes. Despite the setbacks, Raleigh was undeterred. He financed a second attempt in 1587, sending a group of settlers under the leadership of Governor John White. This time, the group included women and children,

indicating that England intended for the colony to be permanent. Among them was White’s daughter, Eleanor Dare, who gave birth to the first English child born in America, Virginia Dare.

From the start, Roanoke Colony faced significant challenges. The settlers quickly encountered problems with food shortages, and tensions rose with the local Indigenous tribes, who may have seen the English settlers as a threat to their own resources. Unable to secure a reliable food supply, Governor White returned to England later in 1587 to seek more support and supplies for the struggling colony. However, his departure would prove more significant than he or anyone else could have anticipated.

The timing of White’s trip coincided with a critical period in England’s history. When he arrived in England, he found the country preparing for war with Spain, which resulted in a naval blockade that prevented White from returning to Roanoke promptly. England’s resources were stretched thin by its defence against the Spanish Armada, and White’s return to Roanoke was delayed for three years.

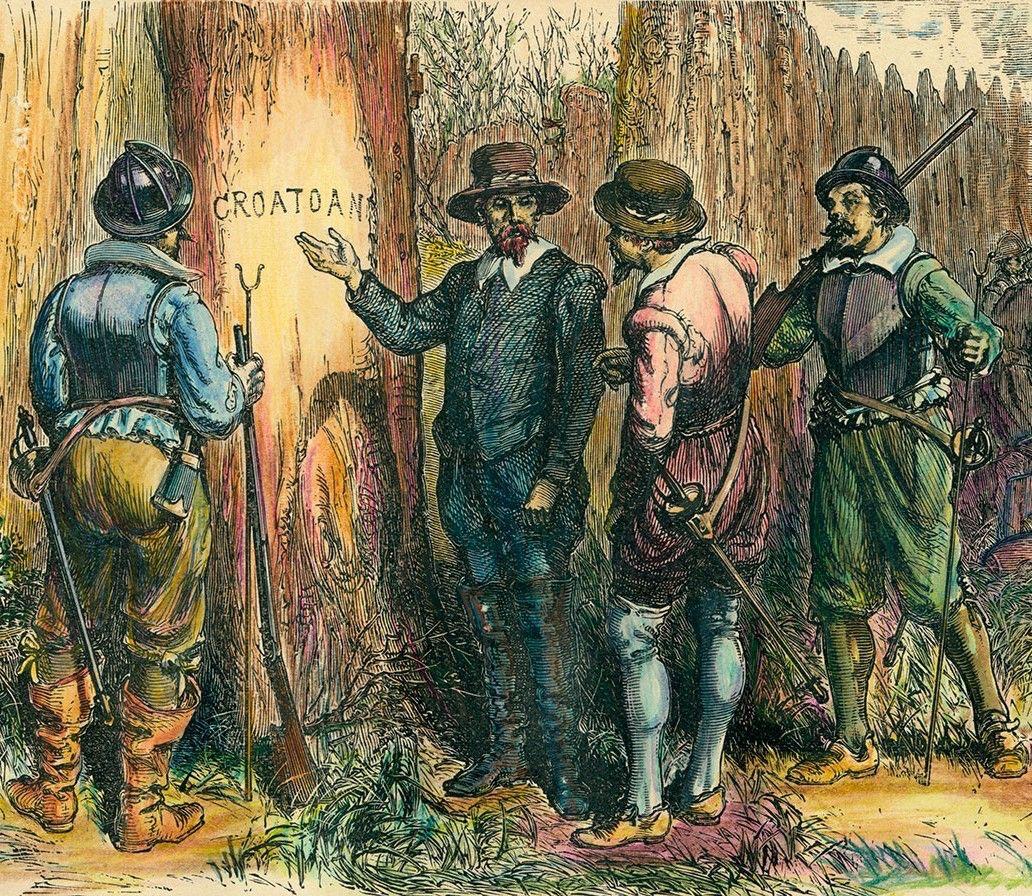

Finally, in August 1590, White was able to return to Roanoke, accompanied by a group of explorers and the supplies he had promised to bring. However, upon reaching Roanoke Island, White found only an eerie silence and an empty settlement. The fort was abandoned, and there were no signs of life. The only clue to the colonists’ fate was the word ‘CROATOAN’ carved into a post and ‘CRO’ etched into a nearby tree. White took this to mean that the colonists had relocated to Croatoan Island (now known as Hatteras Island), which was inhabited by Indigenous people, friendly to the English settlers.

However, a thorough search for the colonists on Croatoan Island was never conducted. Dangerous weather and the reluctance of White’s ship crew to stay in the region forced them to return to England, leaving the fate of the Roanoke settlers a mystery that has never been solved.

One widely accepted theory is that the Roanoke settlers integrated with nearby Indigenous tribes, such as the Croatoan (Hatteras) or other Algonquian-speaking peoples. Proponents of this theory argue that the colonists might have sought refuge among the Indigenous groups to survive after White’s prolonged absence. Archaeological evidence found on Hatteras Island suggests that English and Indigenous artefacts were intermixed, hinting that some degree of cultural integration may have occurred. However, while this theory is plausible, it lacks conclusive evidence linking specific artefacts to the Roanoke colonists.

Another theory is that the settlers moved north to the Chesapeake Bay area, where they may have intended to settle originally. Some historians suggest that Sir Walter Raleigh had plans for a colony in the Chesapeake and that the settlers may have relocated there in White’s absence. Supporters of this theory cite records of Jamestown settlers in the early 1600s who reported encountering Indigenous tribes that spoke English and wore European-style clothing. However, like the integration theory, this idea is largely speculative.

A darker theory posits that the colonists were killed or captured by hostile Indigenous tribes. Relations with certain groups, such as the Secotan tribe, had been tense from the beginning, and conflicts over land and resources were frequent. If the colonists had relocated or attempted to assert themselves elsewhere, they may have encountered violent resistance. However, no physical evidence, such as human remains or signs of a massacre, has been found to substantiate this theory.

A simpler and equally tragic explanation is that the Roanoke colonists succumbed to starvation or disease. Cut off from resupply and facing unfamiliar environmental challenges, the settlers may simply have run out of resources and perished. This theory aligns with the reality of colonial life at the time, which was fraught with hardship and mortality. However, the absence of remains and artefacts makes it challenging to support this theory definitively.

Some historians speculate that the colonists split up, with small groups attempting to survive in different areas. In such a scenario, groups might have moved to nearby islands or further inland, surviving for a while before eventually dying out or merging with Indigenous tribes. Evidence of European-style artefacts and DNA markers in certain Indigenous communities lends some support to this theory, but no clear-cut evidence has been found.

In recent years, archaeologists have renewed efforts to solve the mystery of Roanoke. Excavations on Hatteras Island and areas along the mainland have uncovered European artefacts dating back to the 16th century, including ceramics and tools. Researchers continue to investigate whether these artefacts can be definitively linked to the Roanoke settlers or if they came from later English explorers or traders.

Additionally, a 2012 discovery of a patch on a 16th-century map, believed to mark a hidden fort location, spurred a renewed search in areas around the mainland that were previously overlooked. This ‘Site X’, near the Chowan River, has yielded some artefacts from the time period but has yet to produce definitive evidence connecting them to Roanoke.

The Roanoke Colony remains a strong reminder of the uncertainties and perils faced by early settlers in the New World. Though the mystery endures, the story of Roanoke continues to captivate and inspire, embodying themes of survival, exploration, and the unknown. The tale of Roanoke is more than a mystery; it is a testament to the resilience and tragedy of early American colonisation, and a haunting piece of America’s forgotten history.

Hesiod: The Father of Greek Mythology

Tabitha Blackmore, Y12.

Zucchi: Apollo and the Muses (1767)

While many know of Homer, the Iliad, and the Odyssey, fewer know of his contemporary Hesiod, who, while his texts are not so epic as Homer’s, can be seen as equally important.

Hesiod, whose name translates to ‘someone who sends forth his song’, was a late 8th century BCE poet from a small town in Boeotia named Ascra, and is famed for his two surviving texts, the Theogony and Works and Days. Unlike Homer, scholars can be certain that Hesiod was an actual person that we know a lot about, due to the highly autobiographical nature of the texts. For example, we know in depth about the tumultuous relationship he had with his brother, that his father was a seamerchant turned farmer, and that he despised his town , describing it as ‘horrible in the winter and miserable in the summer.’

As mentioned before, only two of Hesiod’s works survive intact. However, many of the missing works are referenced in the following centuries, so their contents and sometimes titles are available to us. The most referenced is The Great Hers, which is a compendium of all the Goddesses and female characters in Greek Mythology. Not all of Hesiod’s work was so religiously relevant; the Precepts of Chiron is a poem written entirely from the perspective of a centaur about the struggles of its life. Similarly, an unnamed poem is mentioned which is an epic solely about pickling fish.

Greek mythological genealogy is as complex as genealogy can be, and it was at the same time a crucial feature of Ancient Greek society. In the 8th century BCE, there was no unified system of writing, which meant that religion had to be passed down using the oral tradition of poetry, which is exactly what Hesiod’s most famous work Theogony is. This epic poem, starting with the Muses on Mount Helicon, is the first known comprehensive genealogy and catalogue of Greek Mythology, from the disembodied force of Chaos, to the many nymphs that live in Greece’s rivers. Scholars believe that the Theogony was written for the funeral games of the King Amphidamas of Euboea. In the Works and Days, the other surviving text, Hesiod

references a competition he won at the funeral games with a religious compendium. This is believed to be the Theogony, due to the prevalent themes of grief and death found in it, making it perfect for funeral games. The importance of the Theogony to the Ancient Greeks cannot be understated; all religious, moral, and recreational stories had to be spoken aloud, so this 1000-line poem became the primary source for religious teachings, due to its memorability. It is also important to modern day classicists, as Hesiod is believed to have invented many of the names of the Gods, including the Muses, giving them each their name and speciality.

Works and Days is a morally didactic poem, instructing the reader on all manner of things, from how to pay your respects to a 33-part instruction manual for building a wagon. It tells firstly of an argument between Hesiod and his brother over their father's will. Hesiod expounds on issues of right and wrong, using his brother’s idleness and wasteful nature in conjunction with some corrupt kings to instruct on the best morals and actions by which to live. He then proceeds to the Works section of the text; this includes the wagon instructions. This part delves into everyday chores and the best way to do them – the best ways to ensure a good life. The Days section follows, comprising an almanac of days in the Greek calendar showing good and bad days, the very first of its kind and illustrating to us the superstition prevalent in Ancient Greek society. Another insight into Ancient Greek society it gives is the many proverbs that are dotted throughout the poem.

Hesiod is so important as his work shows us the extent of communication between ancient connections. His works follow traditions that have origins in cultures that span the East; for example, he is credited with the very first Greek fable which had origins in the Eastern literature. Furthermore, the morally didactic nature of both the Theogony and Works and Days follows the longstanding traditions of many cultures that are far away from the small Grecian town of Ascra, showing the high level of communication and travel there must have been for Hesiod to follow these traditions. Numerous logical and didactic poems have been attributed to him posthumously, one being the sixth book of Works and Days that was actually written in the 6th century, and, as Hesiod became more popular and increasingly important –particularly in the Alexandrian period – intellectual poets began taking him as their mascots. Eventually, this led to Virgil praising Hesiod as the inspiration for his Georgics, ‘singing Ascra’s song through the streets of Rome.’

The Role of Colonisation and Imperialism in Shaping Global Economic Systems

Louise Adiukwu, Y12.

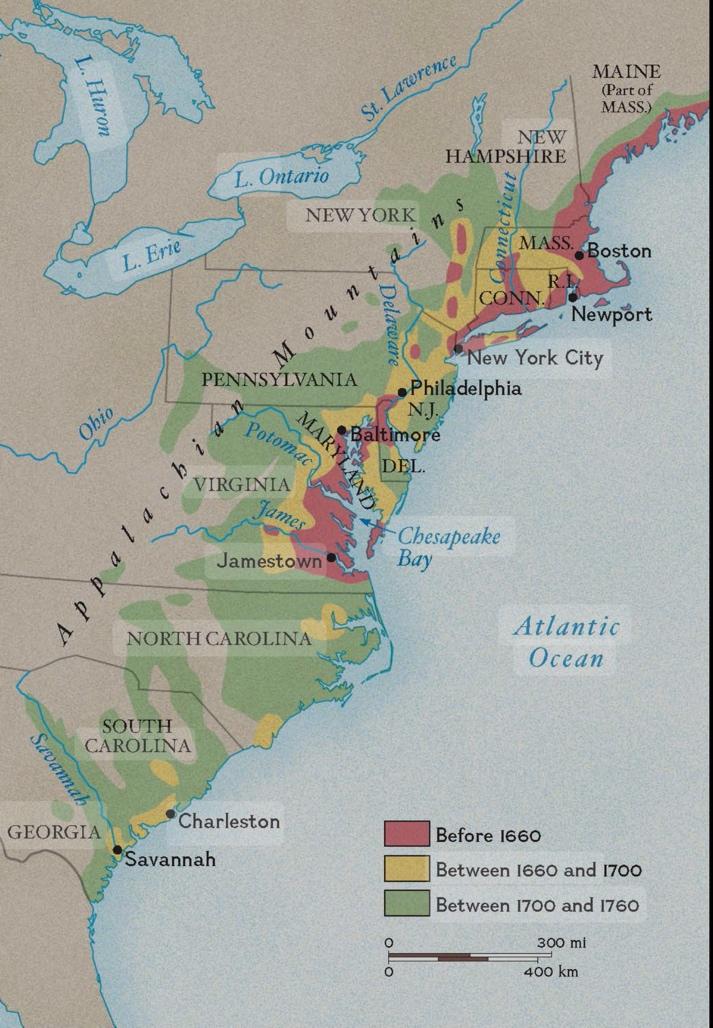

Colonisation and imperialism refer to the practice of gaining control over another territory to exploit it, often for economic gain and power. From the 15th century to today, European powers have expanded empires during their quest for wealth, resources, and geopolitical influence, building trade networks and introducing new goods to global markets. Consequently, these actions have established economic dependencies, reshaped social structures, and contributed to lasting inequalities. This topic invites exploration of the multifaceted roles colonisation and imperialism have played in shaping European dominated global economic systems, including both historical and enduring impacts on colonised regions and the world.

The roots of colonisation and imperialism trace back to the 15th century, marked by Europe's Age of Exploration, when nations at the forefront of the explorations like Portugal and Spain sought new territories and trade routes to Asia for valuable goods – spices, silk, and myriad other luxury goods. Later, the Scramble for Africa in the late 19th century saw European powers dividing the continent, leaving many African nations to continue to grapple with the consequences of arbitrary borders, economic dependency, and underdevelopment.

A primary motivator of colonisation was the pursuit of resources to fuel economic growth and wealth in colonising nations. For instance, Latin America became a major source of silver and gold for the Spanish Empire, boosting European trade and early capitalist ventures while leaving the colonies unable to achieve similar growth. Akin to Latin America, Africa’s wealth in diamonds, ivory, and minerals

fuelled Europe’s industrial age (funding public works, factories, and infrastructure) but left local economies underdeveloped due to lack of reinvestment. This extraction-based model led to wealth accumulation in Europe for investment in industrialisation, while entrenching economic dependency and underdevelopment in the colonies, making them vulnerable to global market fluctuations and widening inequality in regard to wealth distribution.

The colonial economy was most notably shaped by the transatlantic slave trade, which relied on enslaved African labour to maximise profits in plantations and mines, leading to the forced migration of millions to the Americas. This system enriched European traders and landowners, fuelling industrial growth in Europe, especially in textiles and shipbuilding. After slavery's abolition, indentured labour brought Indian, Chinese, and other workers to plantations in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific, creating migrant labour patterns that continue to influence global demographics and labour markets. The slave trade inflicted lasting damage on African societies, including economic destabilisation, cultural disruption, and social fragmentation. It also established a racial hierarchy that laid the groundwork for systemic racism and social inequalities still prevalent in education, healthcare, and housing. These legacies underscore the ethical consequences of economic gain built on labour exploitation.

Colonisation significantly altered global trade by establishing extensive maritime routes that connected colonies with European metropoles (empires’ home territories), creating a global economy characterised by a flow of economies. Europe gained access to a plethora of new crops (e.g. potatoes, maize, and tobacco), transforming diets and agriculture, while European goods entered colonial markets, reinforcing economic integration. However, this led to economic dependency, as colonies focused on cash crops, often at the expense of food security and economic diversity. Many were forced to specialise in exports like tea in India or sugar in the Caribbean, displacing traditional agriculture. Furthermore, infrastructure built by colonial powers roads, railroads, and ports were designed to extract resources

rather than foster internal growth, embedding a pattern of dependency that persisted post-independence.

The legal and institutional frameworks established during the colonial era have left lasting effects on former colonies' economies. European powers restructured land ownership to support plantations and mines, dispossessing indigenous populations and favouring European settlers, causing unequal property rights. Land privatisation and centralisation within these systems benefited elites and foreign investors, restricting local access. Additionally, colonial taxes payable only in colonial currency forced locals into wage labour, shifting economies from subsistence farming to cash-based systems, often resulting in debt and dependence on imperial economies. These institutional legacies reinforced an unequal global hierarchy, perpetuating underdevelopment and economic dependency on former imperial powers.

Ultimately, colonisation established a ‘core-periphery’ economic structure that still defines global economics currently. The ‘core’ includes industrialised, former colonial powers with diversified economies and technological advancements, while the ‘periphery’ consists of former colonies reliant on raw material, exports, international debt, and foreign investment. Evidently, this divide perpetuates economic inequality, affecting trade policies, debt, and aid systems. Many former colonies face significant debt, rooted in colonial economic models, which limited growth potential. Today, multinational corporations in the Global South often replicate colonial extraction practices, benefiting from weak regulations and favourable trade agreements. Therefore, understanding the history and ongoing impact of colonisation is essential to addressing today’s global economic inequalities and building a fairer future. Recognising our past highlights the need for sustainable global economic systems that benefit all nations.

Should We Be Worried about Super-Gonorrhoea?

Dr Martin, Teacher of Biology.

Students that I have taught at New Hall will know that my favourite microorganism is Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacterium that causes the sexually transmitted infection gonorrhoea. I even have a giant microbe soft toy model of it in my lab which I use in lessons.

Prior to teaching I spent 13 years working on the bacterium, undertaking my PhD on N. gonorrhoeae and then did some post-doctoral positions where I led the National and European surveillance programmes for gonorrhoea at the Health Protection Agency (now known as Public Health England).

N. gonorrhoeae is transmitted through sexual contact, though there are rare cases of transmission between mother and child during labour where the baby’s eyes can become infected and can lead to blindness. Not all individuals will have symptoms; they are said to be asymptomatic, which can result in individuals not being diagnosed. It is treated with antibiotics, but when left untreated can cause costly longer term health issues including infertility in females and ectopic pregnancies. Additionally, being infected with gonorrhoea increases the risk of HIV transmission five-fold. The best method of prevention is safe sex using condoms and screening for STIs before unprotected sex.

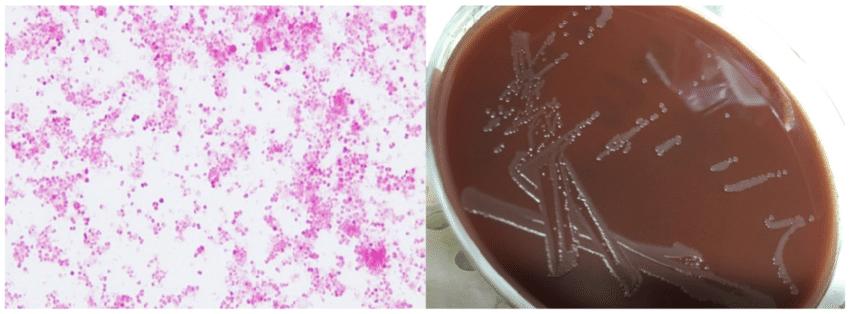

Figure 1: The left microscopy image shows a Gram stain of N. gonorrhoeae and the right image shows the bacteria growing on an agar plate.

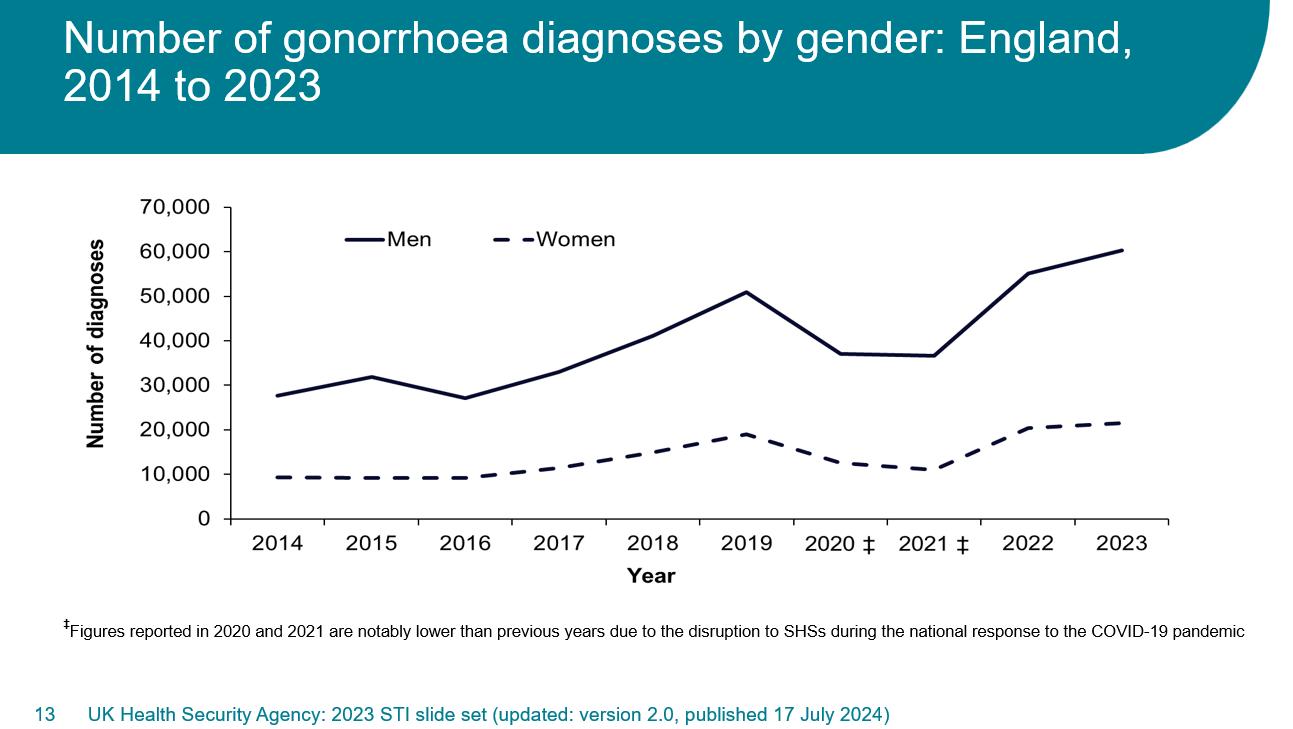

In England gonorrhoea is the second most common STI, with chlamydia taking the top spot, and cases are increasing: in 2023 there were over 85,000 cases in England, an 8% increase on 2022, with peak diagnoses in the 20–24-year-old category and this is from our national surveillance data (figure 2). So, should we be worried with this increase in diagnoses when you can be treated with antibiotics? Well, yes!

Figure 2: Most recent surveillance data for gonorrhoea in England for the past 10 years

Bacteria, including N. gonorrhoeae, are becoming superbugs as they are adept at evolving to become resistant to antibiotics. It shouldn’t be surprising to any GCSE or A Level biologist at New Hall that antibiotic resistant gonorrhoea occurs as the antibiotics used create a selection pressure. To survive, the DNA of the bacteria mutates and, although this is a random process, in gonorrhoea it occurs at a very high rate; if the mutation gives the N. gonorrhoeae an advantage, such as resistance to an antibiotic, they survive. The resistance genes can be in their chromosomal DNA , or in plasmid DNA, and plasmids can be exchanged between bacteria in a process called conjugation. N. gonorrhoeae can reproduce rapidly within the human body and very quickly resistant strains can be spread within the population. In countries where antibiotics are available without a prescription not only are ineffective antibiotics being used, but sub optimal dosing may occur where an insufficient dose is taken, leading to rates of antibiotic resistant gonorrhoea much higher than in England.

Over the last 80 years of antibiotic use to treat gonorrhoea resistance has occurred to penicillins, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones and, more recently, cephalosporins including ceftriaxone. This is where surveillance is essential to inform the treatment guidelines of appropriate antibiotics to use to minimise treatment failures and further spread of the infection. Dual therapy, where 2 antibiotics (Ceftriaxone and Azithromycin) are used, is now the recommended treatment in the UK, USA and Europe, to try to reduce the likelihood of superbug gonorrhoea. These are recent UK headlines:

In England these first 2 reports of super-gonorrhoea in 2018 and 2019 are not isolated and further cases have been diagnosed. Super-gonorrhoea cases have started to occur around the world, with reports also from Japan, Canada, France, Sweden, and Australia, where surveillance programmes are in place and have detected the emergence of these strains. They are incredibly difficult to treat as they are resistant to Ceftriaxone and Azithromycin which are the first line antibiotic treatments to use in most countries. With very few new antibiotics in the drug pipeline it is foreseeable that, in time, super strains of gonorrhoea may become untreatable due to its resistance to all classes of antibiotics available. This is a major public health concern globally.

Surveillance data guides treatment guidelines When resistance to an antibiotic reaches 5% in the population, it is no longer recommended that the antibiotic is used as a first line therapy, as too many treatment failures would occur, facilitating further transmission within the population. Surveillance in one country is not enough to protect against outbreaks of super-gonorrhoea, given its global nature and increasing incidence, as individuals travel and may have unprotected sex, and, as up to 50% of women and 10% of men are asymptomatic, you have the recipe for the spread of super-gonorrhoea. Surveillance data between many countries and world regions, such as Europe, does occur, but it needs improving according to the World Health Organisation. The reporting of new super strains must be quick to help countries be alert and to ensure the appropriate treatment of gonorrhoea occurs and changes are made to these in a timely manner. In England, we are very lucky to have effective surveillance and prompt updates of treatment guidelines that are used by doctors to reduce the emergence of further super-gonorrhoea, but this is not the case in most countries.

A Brief Introduction to Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity

Ned Broderick, Y12.

To begin with, it is important to accept two postulates that Einstein proposed when forming his Theory of Special Relativity. 1) All laws of physics apply in the same way in all inertial frames of reference. 2) The speed of light is constant in all inertial frames of reference. The first means that if you have a constant velocity, no matter how fast you are moving, the laws of physics will all apply in the same way. The second claims that again, no matter your velocity, the speed of light is always constant from your perspective. Both of these postulates have been backed by plenty of scientific data and have become fundamental parts of the way we now view the Universe.

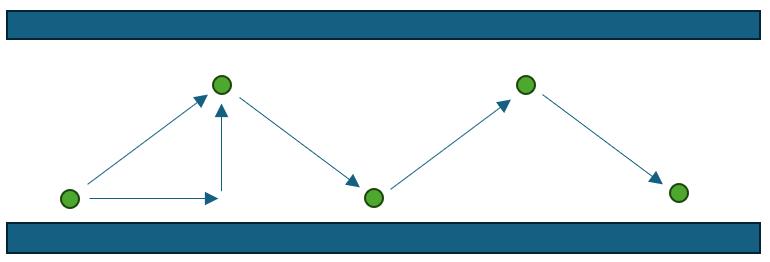

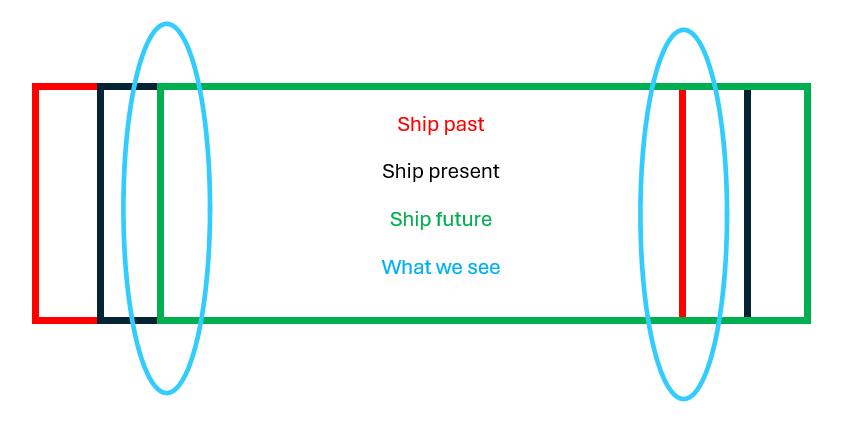

After accepting both ideas, now imagine that you are standing in a room and have two mirrors. You fire a beam of light towards one of the mirrors, and this then bounces back and forth continuously (see Figure 1).

This light (if we imagine it as a photon moving back and forth), travels at c (the speed of light) and so covers x distance in t time (distance = speed * time, so x = ct). However, now imagine that you are on a spaceship moving close to lightspeed. When you are in a car or a plane and are moving at constant velocity, if you close your eyes it often feels like you are not even moving. This is because, relative to the car you are sat in, you are not actually moving. However, if you stood still on the pavement and watched a car go by, relative to you, it very clearly is moving. Now imagine you perform the same light experiment with an alien in the spaceship, and so from your inertial frame of reference (IFOR) the same thing is seen. Remember that we said all laws of physics apply in the same way no matter your IFOR, and so from your perspective, the photon moves in exactly the same way as in Figure 1. Now imagine that you are sitting on the moon watching the spaceship go by. Not only is there motion in the vertical direction (photon moving between mirrors), but in the horizontal direction too; the spaceship had a constant velocity and so did the

Figure 1

alien (standing inside it) as did the light source it was holding, and thus the light itself.

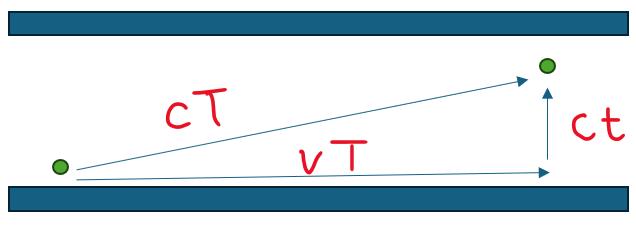

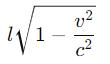

Via the beloved Pythagorean Theorem, it is clear that the net distance moved by the photon as a result of the added movement of the spaceship is far greater (see Figure 2). However, the speed of light is constant and both you and the alien watched the light move from one mirror to the other in the same amount of time. How can we have different distances if distance = speed * time, and, speed & time are constant? The only answer is that one of these is incorrect. We know that the speed is constant from postulate 2 earlier, and the distances are clearly different so the time must be different too (when you look from a different IFOR). It turns out that time passes faster or slower depending on your velocity relative to the observer. We just don’t notice this normally because of how relatively slow everything is.

The next step of the process is the maths. If we take v = velocity of the ship (and so horizontal velocity of the photon), c = speed of light, t = time taken for travel from perspective of the alien, T = time taken for travel from your perspective (on the moon). Distance = speed * time so:

Diagonal distance (distance from your perspective) = cT

Vertical distance (distance from alien’s perspective) = ct

Horizontal distance (distance spaceship and so photon travels from your perspective) = vT

Figure 2

Figure 3

Via the Pythagorean Theorem we now get: (vT) 2 + (ct) 2 = (cT) 2

And after solving for T: T =

This means that if the spaceship were moving at 0.75c (0.75 * lightspeed) relative to an outside observer, a time of 10s inside the ship would appear to be 10/root(10.752) = 15s.

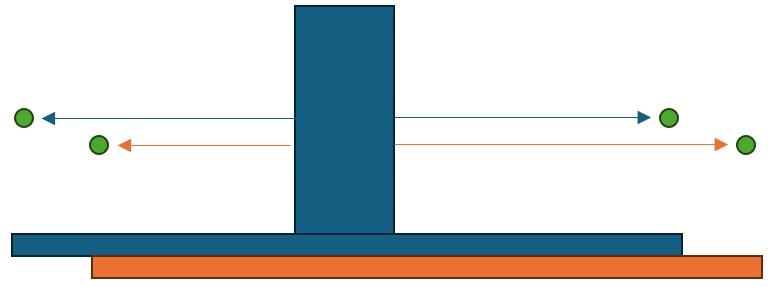

There is a second particularly interesting phenomenon that arises due to this called length contraction. Suppose you were to stand in the middle of the spaceship, take a two-sided torch, and fire two photons in opposite directions (see Figure 4).

From the alien’s perspective they each take the same amount of time to reach the walls on either end. However, from your perspective as an outside observer, since the spaceship has moved forwards by the time the photons reach the walls (direction of motion in this example is to the right), one has moved further than the other (see Figure 5), and so (due to the consistency of the speed of light) the left photon takes less time to reach the end than the right photon.

Figure 4

Figure 5

This means that from your perspective time passes faster on the left and slower on the right (allowing both to take the same time inside the ship but more time for the right-hand photon outside of the ship). In other words, the back of the ship is slightly in the future (relative to its centre) and the front is slightly in the past (see Figure 6).

This results in the ship contracting in length (from your IFOR).

There is one final quite interesting case to consider which will allow us to calculate the length contraction. Suppose the alien were to stand at the back of the ship and shine a torch to the end. To it, the photon appears to take t = l/c to reach the end (where l = length of the ship and t = time relative to it [him] ). However, to you (the outside observer) it appears to take T to reach the end (the spaceship is moving and so time dilation makes it take longer from your perspective) – see Figure 7.

Figure 6

Figure 7

was used, however for ease this will be written as T = γt where:

γ =

T= γt and t = l/c so T = γl/c

As described above the spaceship will appear to contract in length, and so T = L/c (where L = length of the ship from your perspective). Setting these equal to each other gives us L/c (= T) = γl/c so L = γl so

L = Therefore, if the spaceship were moving at 0.75c and were 100m long, it would, from your IPOR, actually be 66m long.

As a question for the reader, how fast would a tank have to be travelling so that it had the same length as a calculator?

Science in the DC Universe: The Lasso of Truth

Chidera Maduka Agbeze, Y13.

Most, if not all, people have heard of Wonder Woman - Princess of the Amazonians. A powerful warrior, she fights criminals and monsters to save innocent civilians. And, like all superheroes, she has skills and tools that we instantly associate with her when we think about her, one being the Lasso of Truth, forged by a god; a weapon Diana uses to capture villains and force them to tell the truth. What if we could make one?

First, we would have to consider what the weapon is and its purpose before making any suggestions on how to make it. As previously stated, the Lasso of Truth is a lasso that forces people, who are bound by it, to tell the truth. The way the lasso does this is through magic, but we obviously don’t have access to magic, so we would have to use neurological technology instead to give the lasso this function. So, the next question is: why do we feel obligated to tell the truth? To answer this question, I am going to approach it from a biological viewpoint. Usually, when we withhold the truth from people, we feel a level of stress and dishonesty, as we are concealing something from them that could potentially damage our relationship if they find out. This stress stimulates the release of 2 hormones called cortisol and adrenaline. Cortisol is a steroid hormone that is produced in the adrenal cortex after receiving signals from the pituitary glands and hypothalamus. Using cholesterol as the starting molecule, it goes through the steroidogenesis pathway to become cortisol and, secreted by the adrenal glands into the bloodstream (where the molecule binds the CBG and albumin so it can be transported) , it reaches a normal range of 3 to 20 micrograms/decilitre. One of its roles is to increase energy

availability to respond to stressful situations by increasing both blood sugar levels and increasing fat metabolism; prolonged exposure to high levels of the hormone has been linked to anxiety and depression. Adrenaline (also known as epinephrine) is the fight or flight hormone. It is secreted from the adrenal medulla – the inner region of the adrenal glands – in a range of 0 to 900 picograms/millilitre. It prepares our bodies to make quick decisions when we are faced with a dangerous situation by increasing heart rate, cardiac output, blood-sugar levels, oxygen intake, etc. When our bodies release these hormones, the physical strain that it puts on our body is a necessary trade off to increase our chances of survival in dangerous situations, but only during necessary periods of time; excess exposure to these hormones can cause high blood pressure, mood disorders, and muscle tension, which cause pain, discomfort, and fatigue. As creatures who aim to build good relationships, we are biologically hardwired to try to build those relationships, which is why we have a hormone called oxytocin, the bonding hormone. This hormone is produced in the hypothalamus (a region in the brain) and is secreted by the pituitary gland into the bloodstream. One of its functions is to prompt feelings of trust and empathy between individuals, so they can build good relationships; this hormone provides feelings of calmness by reducing blood pressure and stressrelated response, like those listed previously.

So, if the Lasso were real, it could increase both cortisol (above 20 micrograms/decilitre) and adrenaline (above 900 picograms/millilitre) levels within the person who is bound, so if they were not to tell the truth, they would experience high blood pressure and muscle tension, which would make them weak and more compelled to tell the truth. However, upon telling the truth, the Lasso would also stimulate the high release of oxytocin to reduce the stress-related pain experienced by the person. So, one way for the lasso to stimulate the hypothalamus and pituitary glands would be electronic methods such as deep brain stimulation – a method that involves implanting electrodes in specific brain regions – and transcranial magnetic stimulation – a procedure that uses magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain. However, both of them require placement on the scalp, yet the Lasso of Truth can be used all over the body – not just on the scalp; so, these methods of stimulation won’t be ideal. The next method would be using a neurostimulation device (the use of electrical stimulation to treat neuropsychiatric disorders, such as epilepsy) to stimulate the release of the hormones.