The Griffin

A student-led publication.

Introduction

The Humanities Corner

The Development of Animal Rights: A Shift Towards Legal Personhood and Abolition

Emily Dobbie

“Did the author really think of that?”: Biblical and Intertextual

Allusions in Fiction

Mr Kerr

Can Morality Exist Separately from God?

Aidan Clifford

Pythagoras of Samos: The Man, the Myth, the Legend

Max Pietrzak

The STEM Corner

Understanding Dissociative Identity Disorder

Aurora Navti

The Development of the Mobile Phone: From dream to reality, with a ‘little’ help from science

Dr Thomas

The Complexities of Informed Consent in Paediatric Care

Trinity Iya Njopa-Kaba The Plausibility of

Welcome to the second edition of The Griffin! This is a student-led journal, published every half-term, which hopes to provide a platform for students, staff, and alumni to write about absolutely any topic that interests and excites them. This half-term’s issue includes another brilliant selection of entries, ranging from exploration of ‘SciFi Energy Shields as a New Technology’, to discussion of more perennial questions, such as ‘Can Morality Exist Separately from God?’ ; hopefully, something to pique everyone’s interest!

I would like to extend a huge thank you to all of those who wrote an article – this would not exist without you! It would also be remiss of me not to give special thanks to Mr Goulding, who was, once again, massively helpful in the editorial process.

If you – students, alumni, staff, or parents – are interested in contributing to the next half-term’s edition, please get in contact at: maximilian.pietrzak@newhallstudent.co.uk

As ever, any feedback on the journal is also warmly welcome and encouraged – it is your opinion that matters!

I hope that you enjoy your reading of the articles!

Max.

The Development of Animal Rights: A Shift Towards Legal Personhood and Abolition

Emily Dobbie, Class of 2022

In recent years, the field of animal rights has experienced a transformative shift in its approach, challenging conventional views and advocating for fundamental changes in the way society treats animals. While the concept of animal rights has existed for decades, recent developments have pushed the boundaries further than ever before, advocating not just for improved treatment of animals, but for their legal personhood, autonomy, and liberation from human exploitation. This revolutionary wave of progress in animal rights is reshaping the way in which we think about our relationship with animals, and it is challenging the very structures of industries that have long relied on animal exploitation.

A Growing Movement for Legal Personhood

One of the most innovative developments in the animal rights movement in recent years has been the push for legal personhood for animals. This movement, led by groups such as the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP), argues that certain animals particularly great apes, elephants, and cetaceans should be recognized as ‘persons’ under the law, with rights akin to those of humans. This concept challenges the traditional legal status of animals as property, which has historically allowed them to be used and exploited for human purposes.

Legal personhood would grant animals fundamental rights, such as the right to liberty, the right to be free from exploitation, and the right to be protected from harm and captivity. The legal recognition of animals as ‘persons’ would mean that they could no longer be owned, used for entertainment, or confined in zoos or laboratories. Instead, they would be entitled to legal protections and the right to seek freedom.

In pioneering cases in the U.S. and abroad, the Nonhuman Rights Project has filed lawsuits seeking writs of habeas corpus for chimpanzees, arguing that they are sentient beings deserving of the same rights as humans to be free from captivity. Although these cases have yet to result in widespread legal changes, they have sparked a larger global conversation about the moral and legal status of animals.

Abolition of Animal Exploitation: A Radical Rejection of Human Domination

Another development in the animal rights movement is the abolitionist approach, which calls for the complete end of all human use of animals. Abolitionists argue that animals should never be used for food, clothing, entertainment, or research regardless of how well they are treated. This approach is rooted in the belief that the mere act of using animals for human purposes is unethical and that the very foundation of our relationship with animals needs to be changed.

The abolitionist philosophy stands in stark contrast with the animal welfare perspective, which seeks to improve the treatment of animals within existing systems (such as factory farming, circuses, and laboratories). While animal welfare advocates work to minimize suffering and improve conditions for animals in these systems, abolitionists argue that we should be focusing on completely ending the use of animals altogether.

This bold stance is reflected in the growing movement toward veganism and plantbased diets, which are seen as essential to ending the exploitation of animals. Abolitionists contend that, in a truly ethical world, humans should not consume animals or use them for entertainment or scientific testing. This view is gaining traction among those who believe that any form of animal exploitation no matter how humane is fundamentally unjust.

The Rise of ‘Ecofeminist’ Animal Rights

In addition to the push for legal personhood and abolition, another emerging development in animal rights is the influence of eco-feminist theory on animal rights philosophy. Ecofeminism argues that the oppression of animals is deeply intertwined with other forms of oppression, including the exploitation of women, indigenous peoples, and the environment. This perspective asserts that the domination of animals, particularly in industrial farming and the use of animals in research, is part of a broader system of exploitation that harms both animals and marginalized human communities.

Ecofeminist theorists emphasise that addressing animal rights requires not only a focus on animals themselves but also a recognition of the ways in which animals' exploitation is connected to other forms of injustice. This includes examining the environmental impact of factory farming, the abuse of female animals in breeding industries, and the displacement of indigenous peoples and wildlife in the name of animal exploitation. By framing animal rights as part of a larger social justice movement, ecofeminists are calling for a more holistic and intersectional approach to the ethical treatment of animals.

Emotional and Psychological Welfare

Another significant shift in animal rights discourse is the increasing emphasis on animals' emotional and psychological welfare. Historically, the animal rights movement focused primarily on physical well-being and the prevention of physical abuse. However, recent developments in animal behaviour and cognition research have shown that animals, particularly social species like dolphins, elephants, and primates, have rich emotional lives, including the ability to experience joy, sadness, empathy, and grief.

This growing understanding of animal psychology is driving the movement to focus not just on stopping physical abuse, but also on ensuring that animals are allowed to express natural behaviours and

form social bonds in environments that allow for their emotional well-being. For instance, the captivity of dolphins and elephants in zoos and marine parks has come under increasing scrutiny, with animal rights activists highlighting the psychological harm caused by isolation, confinement, and forced performances.

As a result, there is growing support for the idea that animals should have the right to live in environments that allow them to thrive emotionally and socially, not just physically. This shift in focus is leading to calls for greater sanctuary-style care for animals that have been rescued from captivity or abuse, where they can live out their lives in more natural, supportive environments.

Global Influence and the Expansion of Animal Rights Laws

The revolutionary shift in the animal rights movement is also having a profound impact on legal frameworks around the world. Countries like New Zealand and Switzerland have already made significant progress in recognising animals' rights in their legal systems. In 2019, New Zealand became the first country to grant legal personhood to the Whanganui River, recognizing it as a living entity with rights, which is seen as a victory for animal and environmental rights groups.

In the same vein, Switzerland has laws that recognize dolphins and elephants as sentient beings and grant them specific protections against exploitation. Several European countries, including the UK and Austria, have passed animal welfare laws that go beyond mere protection from cruelty, offering legal recognition of animals’ ability to feel pain and suffer.

The legal recognition of animals as sentient beings and the potential for granting them personhood could mark a turning point in the global legal landscape, significantly altering how animals are treated and what rights they are afforded.

Challenges and Criticisms

While these developments in animal rights represent significant strides, they are not without their challenges and critics. Opponents argue that the legal recognition of animals as persons is impractical and could lead to unintended consequences, such as disrupting industries that rely on animal use, including agriculture, pharmaceuticals, and entertainment.

Additionally, some animal rights advocates argue that even progressive changes like sanctuary care and personhood recognition are insufficient if they don’t lead to the complete abolition of animal use. For them, the ultimate goal remains the elimination of all exploitation of animals, rather than incremental improvements in how they are treated within human-dominated systems.

Conclusion

The transformative developments in animal rights represent a growing movement to change fundamentally how society views and interacts with animals. From the push for legal personhood and the abolition of animal exploitation, to the incorporation of emotional welfare and eco-feminist perspectives, the animal rights

movement is increasingly challenging the status quo and calling for profound ethical changes.

As society becomes more attuned to the emotional and psychological lives of animals, and as legal frameworks begin to shift, the conversation about animal rights is expanding into new, innovative territory. While the movement still faces significant opposition and challenges, its growing influence and the ongoing legal and ethical debates signal that we may be on the cusp of a major revolutionary transformation in how animals are treated globally.

“Did the author really think of that?”: Biblical and Intertextual Allusions

in Fiction

Mr Kerr, Teacher of English

One of the most frequently asked questions I encounter as an English teacher is, “Did the author really think of that?” a query often raised when analysing a specific word or phrase in a text, whether at GCSE or A Level. My response is often to highlight patterns, recurring motifs, or, most compellingly, biblical or intertextual allusions, demonstrating that, yes, the author likely did consider such details. Teaching English at a school like New Hall offers a unique advantage in this regard: students’ deep understanding of the Bible and its stories enables them to engage more profoundly with literature. This familiarity allows them to identify and appreciate biblical references and allusions that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Biblical and intertextual allusions are, in their most simple form, references within a text to other works, stories, or concepts. These allusions often function as tools for writers to imbue their fictional narratives with deeper thematic or cultural meaning.

Take, for example, Shakespeare’s Macbeth, which tells the story of the ambitious Macbeth, who murders King Duncan to seize the Scottish throne, only to be haunted by guilt and paranoia. Following the regicide, Macbeth contemplates his horrific act, using the imagery of his “hangman’s hands” metaphorically “plucking” out his eyes, which reveals his deep horror at what he has done. Here, this self-inflicted punishment evokes biblical figures like Judas Iscariot. According to the Gospel of Matthew, "when [Judas] saw that [Jesus] was condemned, repented himself, and brought again the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and elders, Saying, I have sinned in that I have betrayed the innocent blood. And they said, What is that to us? see thou to that " (Matthew 27:3-4). Like Macbeth, Judas betrayed Christ and endured the torment of his conscience, ultimately leading to his suicide and foreshadowing Macbeth’s psychological disintegration, illustrating guilt as a form of divine or self-imposed retribution.

Likewise, Lady Macbeth, in an effort to soothe her husband’s guilt, asserts that “a little water clears us of this deed” after Duncan’s murder. This reference to purification through water resonates with the Christian sacrament of baptism, symbolising spiritual cleansing and rebirth; however, Shakespeare subverts this idea, demonstrating that no earthly action can absolve them of their sin. The scene parallels Pontius Pilate who “washed his hands before the multitude, saying, I am innocent of the blood of this just person: see ye to it”. (Matthew 27:24) Here, washing his hands after condemning Jesus to crucifixion is an act intended to signify his innocence, but ultimately, Shakespeare uses it to highlight Macbeth’s moral cowardice. Likewise, the Macbeths’ attempts to distance themselves from their crime prove futile, as their guilt manifests in Lady Macbeth’s obsessive handwashing in her final scene on stage.

By contrast, Macbeth’s lament that “Neptune’s ocean” cannot “wash this blood clean” highlights the depth of his remorse. Neptune, the Roman god of the sea, represents immense power and the vastness of the ocean, yet even this divine force

cannot cleanse his guilt. When Macbeth envisions the sea turning “incarnadine”, it alludes to the biblical plague of blood in Exodus, where God transformed water into blood as a form of divine retribution. Shakespeare’s use of this allusion emphasises the magnitude of Macbeth’s moral transgression and the inevitability of divine punishment for those who defy natural and spiritual order by committing regicide, an act viewed as an assault on God’s anointed king.

Similarly, in An Inspector Calls, set in 1912, J.B. Priestley critiques capitalist individualism and social inequality through the investigation of a young woman’s suicide. The Inspector, a moral figure, asserts, “We are members of one body”, directly referencing Corinthians: “But now they are indeed many members, yet but one body” (1 Corinthians 12:20). This verse compares society to a human body, where all parts must work together for the whole to thrive. By using this imagery, Priestley critiques the selfishness of the Birling family, whose exploitation of Eva Smith, a working-class woman, symbolises the mistreatment of the marginalised. At this point, the Inspector’s repetition of “millions and millions and millions” universalises Eva’s suffering, highlighting the widespread nature of poverty and inequality. The surname “Smith”, one of the most common in English-speaking countries, reinforces her representation of countless others in similar situations. Through these allusions, Priestley presents a moral imperative: society must value and protect its most vulnerable members, or it will face dire consequences akin to divine judgement.

Conan Doyle’s The Sign of Four, which follows Mary Morstan and Dr. Watson as they investigate the mystery of a hidden treasure, is perhaps more subtle in its use of allusion. Thaddeus Sholto, a minor, albeit key character, expresses a strong desire to share the Agra treasure with Mary, referring to her as “a wronged woman”. This gesture of atonement, as well as his name, connects him to Jude, also known as Judas Thaddeus, the patron saint of lost causes and desperate situations. Jude was one of the Twelve Apostles, and his link to redemption and hope reflects Thaddeus’ wish to make amends for his father’s greed and to seek moral salvation. The intertextual resonance deepens the reader’s understanding of Thaddeus as a flawed, yet fundamentally moral, character striving to make amends. The biblical allusion juxtaposes the destructive power of greed, as embodied by his father, with the redemptive potential of humility and selflessness.

Finally, in The Grapes of Wrath, set during the Great Depression, Steinbeck tells the story of the Joad family as they journey westward in search of a better life, only to encounter systemic exploitation and despair. In a powerful moment towards the novel’s close, Uncle John Joad, a deeply troubled and guilt-ridden man, sets the stillborn child of his niece Rose of Sharon, a young, pregnant woman who is initially filled with hope for a better future, adrift in a makeshift coffin on a river, echoing the tale of Moses in Exodus (Exodus 2:3). This act of placing the child in the river, though born of despair, is ultimately one of faith, signalling the possibility of redemption and a new beginning. In this way, the river serves as a metaphor for both loss and potential renewal, just as Moses’ journey marked the beginning of the Israelites’ eventual deliverance from oppression.

In contrast, Steinbeck’s narrative uses the stillborn baby to represent the death of hope and society’s failure to nurture life. Uncle John’s heartbreaking command to the box “Go down an’ tell ‘em” charges the baby with the task of bearing witness to the suffering of migrant workers. This act turns the redemptive promise of the Moses story on its head, emphasising the moral emptiness of a society that values profit over humanity; the stillborn child becomes a silent prophet whose fate reveals the corruption and dehumanisation faced by the marginalised.

Throughout each of these texts, biblical and intertextual references create a moral framework that ties the characters’ actions to larger spiritual or cultural narratives. Macbeth’s blood-stained hands, the Inspector’s plea for unity, Thaddeus’ search for redemption, and the stillborn child in Steinbeck’s river, all tally with timeless tales of sin, judgement, and salvation; in each, the writers tie their characters’ personal struggles to shared human experiences. In the end, such references remind us that fiction is not created in a vacuum; the author really did “think of that”. From Shakespeare’s examination of guilt and divine retribution to Steinbeck’s condemnation of systemic injustice, these stories continue to resonate, prompting us to face the repercussions of ambition, neglect, and greed in our own lives and communities.

Can Morality Exist Separately from God?

Aidan Clifford, Y13.

Is the contention ‘God is good’ analytic or synthetic? Suppose it is analytic, as the theist would have you believe: we would be subject to a world in which morality, in every sense, stems from a Divine Being and/or God. Alternately, taking the route of a synthetic statement, moral goodness and evil would exist as independent forces potentially subjective to human understanding.

Firstly, I would like to define morality as the ability to tell right from wrong correctly; thus, the question becomes whether or not one can accurately tell the difference between ‘rightness’ and ‘wrongness’ in a world lacking the Divine. In this we can observe the Euthyphro dilemma: (a) does God command x because it is good, or (b) is x good because God commands it; with horn (a) we are presented with the dilemma of morality superfluous to the existence of a ‘good God’, that is to say morality supersedes the Divine. This contention limits the power of the omnipotent God of classical theism, consequently creating a logical fallacy. And so, we must undertake the second, horn (b); this presents the idea of morality being arbitrary – something becomes good simply because God commands it to be so. This idea relies on the logic that “the Lord is good” (Psalm 34:8-10); however, this logic creates an issue for the theist: the statement ‘God is good’ cannot remain tautologous, nor can it avoid circular reasoning.

Plato (right) and Socrates, in The School at Athens by Raphael

The theists often respond to this dilemma by placing moral grounding in God’s nature, rather than his actions, attempting to assert that something is morally correct if it is congruent with Gods nature. However, this stance assumes that God’s nature is inherently good, consequently neglecting to inform us as to why God’s nature is the standard of goodness in the world; now the only logical way to render God’s nature as good would be to compare it to an independent moral goodness. Without this independent morality we would be left with a circular argument: God’s nature is good because God is good. To suggest that something may have inherent moral value works against the theist by leaving room for statements such as ‘good is good because it is good’ to have resonance, as, under this view of inherent value, to say that ‘God is good’ is just to move the full stop along from ‘good is good’. To this, some theists may persist in the primacy of God as the source of all morality, by arguing that ‘God is good’ is an analytic statement, which we will now evaluate.

The statement ‘a married woman is a wife’ is still logically sound when inverted to ‘a wife is a married woman’ – it is tautologous; the same cannot be said for ‘God is good’. Although we may be able to assert that ‘God is good’, we cannot implement this logic in the same way we could other analytic statements, for otherwise we would be arguing that ‘goodness is God’. This logic seems to fail when reviewing statements such as ‘preservation of human life is God’; God as a criterion fails to encapsulate the dynamic nature of ‘goodness’. The predicate here (goodness) is providing new information for the subject (God), and so goodness cannot be universally applied as a counterfeit for God, or put more simply: God and goodness are not interchangeable terms. With this in mind, it is to be noted that we must be able to understand the criterion of goodness to be able to apply it to a subject such as God, and so an intellectual understanding that goodness is morally right exists separate from a Divine body. Significantly, so too does the belief that God is worthy of worship.

A final point of issue can be observed through the lens of process theology. This school of thought posits God as affected by the experiences of the world, rendering God’s ‘goodness’ as a dynamic quality that grows and evolves along with creation. With this in mind, we may view moral growth or recognition as a Divine-human collaboration; we may observe God to be ‘good’ as rational creatures capable of complex thought. Conversely, in the absence of our existence, God’s ‘goodness’ fails to become realised, negating both the existence of goodness and, too, the idea of an objective morality. This argument can be strengthened by Hume’s law; in this he reasons that things may only exist if they can be empirically verified by our senses, and so the existence of morality would fail to retain traction as a result of its metaphysical grounding.

And so, now the issue arises: whence could this separate intellectual understanding of moral goodness originate? With this we could observe the Darwinian logic of natural selection. We can come to understand an intrinsic and natural aversion to physical pain and suffering; in the same way that a bacterium will avoid death or an elephant in the wild will avoid pain, the atheist would have us believe that we as humans have extrapolated a moral compass from the rudimentary principle of pain constituting badness. As intellectual and rational beings we have become able to

engage correctly in moral dilemmas as a result of years of observation around what has caused harm not only to ourselves but to others. This conclusion then presupposes that, indeed, morality may exist without the Divine; however, in favour of the theist, it may be noted that our inclination to morally good acts, rather than the derivation of moral goodness and badness, still partially relies on an authority which can only be observed through the presence of the Divine.

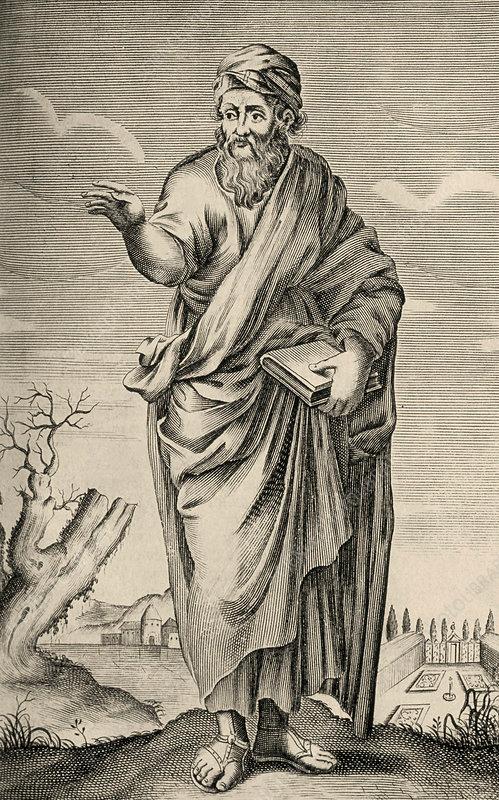

Pythagoras of Samos: The Man, the Myth, the Legend

Max Pietrzak, Y12.

For over two millennia, mathematicians have deceived their students – albeit, perhaps not willingly –regarding one of the most fundamental, “beloved”* even, mathematical principles: Pythagoras’ Theorem. Despite the obvious implications of the name, it is highly improbable that Pythagoras himself actually discovered the Theorem, though the Pythagorean school is often credited with providing the first thorough proof. Rather, the evidence points toward an Egyptian conception, by which Pythagoras is likely to have been inspired. What’s the big deal, then, about some random Greek bloke from some random seaside town, who probably plagiarised the idea for which he has been perennially famed? As it transpires, there was more to Pythagoras than triangles.

Amongst the notoriously elusive Presocratic philosophers, Pythagoras stands out especially as one whose mythical status is exceedingly difficult to reject. As a result, unearthing the ‘real’ Pythagoras is a somewhat impossible task; for the most part, we can but sift our way through lore and fantasy. Tenuous as this is for a factual portrait, it does make for a particularly remarkable, eccentric, and in some cases even amusing glimpse at the man and his legacy.

Originally from Samos, off the western coast of modern Turkey, Pythagoras is now most closely associated with the Greek settlement of Croton in Southern Italy. From Croton he is credited with founding the Italian school of philosophy – and within this Pythagoreanism – which would leave an indelible mark on philosophy for much of antiquity and beyond, influencing even those whom we now deem to be the fathers of Western philosophy. I should offer the caveat that the claim that Pythagoras ‘founded’ this school is made in a particularly loose sense of the word –one which does not necessarily entail much demonstrable philosophical contribution. Though he wrote no books of which we are aware, Pythagoras’ musings, teachings, and activities are recorded by many subsequent doxographers and historians, with some composing biographies even 1000 years after his death.

Amongst his devout following, Pythagoras held a quasi-divine status, with filial claims to the likes of Apollo and Hermes. Not only was he deific by genealogy, but by action, too; authors like Iamblichus and Porphyry offer countless stories of miracles associated with Pythagoras, many of which sound eerily familiar in a Catholic school. These include: healing both the mentally and physically sick, walking on water, calming storms, levitating, predicting future events, and resurrecting a dead man. Indeed, this familiarity is no accident; at the time of Iamblichus and Porphyry’s writing in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, the rise of Christianity posed a grave threat to pagan religion in the Roman Empire. It was thus very much in the interests of those who did not subscribe to Christianity,

including both Iamblichus and Porphyry, for Pythagoras to satisfy so many of the prevailing criteria for supernatural-sage-status. Iamblichus even goes as far as to say that Pythagoras was capable of spontaneously vanishing, transfiguring himself, and talking to animals, all of which seem pleasingly Hogwartian Yet, the notion of a supernatural Pythagoras was nothing new, even if it did evolve with the political climate; details including his having a golden thigh (a trope for the divine in antiquity) appear in accounts as far back as Aristotle.

When not cosplaying Harry Potter and/or Jesus, Pythagoras primarily concerned himself with two areas of thought: mathematics, and religious and ethical conduct. These subsects divided his followers too into two main camps: the acusmatikoi (those interested in his ethical teachings), and the mathematikoi (whom Peter Adamson aptly labels the ‘math geeks’). Though the mathematically-inclined Pythagoreans would later make genuine advancements in the field, it seems that Pythagoras himself, and his early followers, had a rather mystical relationship with numbers. Though such beliefs did in fact constitute the basis of their entire worldview, they oftentimes come across to the modern reader as – to put it bluntly – bizarre. For example, the mathematikoi held the belief that the number 5 represented marriage, on account of its being the sum of 2 and 3, each representing female and male, respectively. They also held the number 10, associated with the so-called ‘terakys’ (a triangle consisting of 10 dots equally-spaced, arranged in incrementally increasing rows, believed to symbolise the arrangement of the universe), to be of such fundamental importance to their mathematics and cosmology that they literally worshipped it; this entailed reciting a prayer beginning, “Bless us, divine number, thou who generated Gods and men!”.

The acusmatikoi held similarly quirky beliefs and practices, derived from acusmata –oral maxims attributed to Pythagoras – from which three subcategories are often extrapolated: A) those which detail what something is (e.g. ‘What is a trireme? A type of Greek ship.’), B) those which indicate what is the most of something (e.g. ‘What is the most just thing? The gods.’), and C) those which suggest what one ought or ought not to do. The lattermost type of acusmata varies greatly in its contents, ranging from yet more eccentricity to what seem to be genuinely constructive instructions, even to the modern reader. On the one end of the spectrum, abstention from beans, specifically of the fava variety, stands out as a one of the more famous acusmata Explanation theories for this include the beliefs that the beans housed the souls of the dead (thus to eat them would be cannibalistic), had too flatulent an effect on their consumers, resembled human foetuses too closely, and resembled both male and female human genitalia too closely. However ridiculous this may seem, fava beans obviously meant quite a lot to Pythagoras, given that most accounts of his death reference his regard for the lives of beans above his own; one account has him refusing to cross a field of fava beans to evade a soon-to-be murderer, for fear of killing the beans by stepping on them. On the other end of the spectrum, another acusma describes the need for two moments of ‘thoughtful reflection’ during the day; when one wakes up in the morning, and when one goes to bed at night. Porphyry recounts some productive prompts for these moments of reflection: ‘Where have I failed myself? What have I done? What duty have I not fulfilled? ’ Pythagoras also seems to have had some catchy, gnomic remarks up his sleeve, which reveal that at

least some of his acusmata demanded more than a literal reading (or listening, if you will): ‘Eat not your own heart’, ‘Vex not the fire with the sword’, ‘Pluck not the crown’, and ‘Sit not on the corn ration’.

Though Pythagoras remains a household name for a rather dubious reason, his lesser-known legacy was, nevertheless, a remarkable and exciting one. Perhaps the next time you are solving for the hypotenuse, or (more likely) cutting across the diagonal of a rectangular space in haste, you might be reminded of the fascinating and unique musings and antics of Pythagoras the man, the myth, and the legend.

*Edward Broderick, A Brief Introduction the Einstein’s Theory of Relativity (The Griffin, Issue I)

Understanding Dissociative Identity Disorder

Aurora Navti, Y12

Dissociative identity disorder (DID), previously known as multiple personality disorder, is a severe mental health condition which belongs to a larger group of dissociative disorders. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health, fifth edition (DSM-5), identified DID as ‘identity disruption indicated by the presence of two or more distinct personality states’. With its strong connection to childhood abuse, those with the disorder use dissociation as a defence mechanism in traumatic situations, allowing them to escape from the trauma and feel as though, in that moment, it is not happening to them.

The defining diagnostic feature of DID is the presence of two or more distinct identities or personality states, which may be described in some cultures as an experience of possession. Another feature is amnesia, defined as ‘gaps in the recall of everyday events, important personal information, and traumatic events, inconsistent with ordinary forgetting’. Moreover, symptoms must cause clinically significant distress, resulting in difficulty functioning. This disturbance is not part of normal culture or religious practice, nor due to direct physiological affects of a substance (e.g. drugs or alcohol) or of a medical condition (e.g. complex partial seizures).

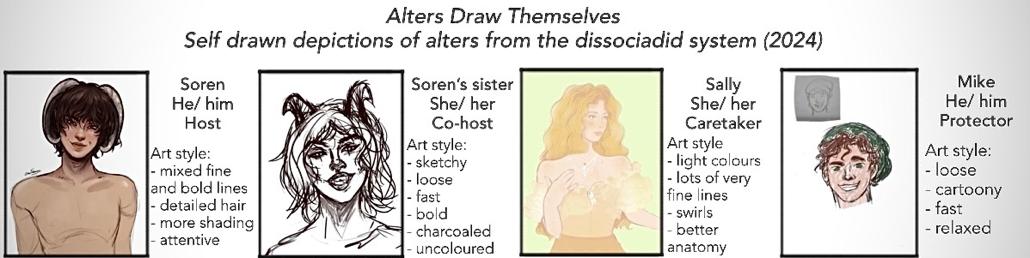

The system

The term ‘alter’ refers to alternate states of consciousness, which collectively form a ‘system’. It is important to note that, though existing within the same corporeal body, different alters develop separately, with various opinions, memories, religions, genders, sex, sexual orientation, physical appearances, and possibly different mental and physical disorders. Thus, they have a sense of ownership over their own thoughts, actions, and abilities, and experience a disconnect from that of others in their system. As any individuals, alters may not always get along and can interact with one another to varying degrees. Though many would have existed from childhood and grown up throughout their lives, not all alters age – some may be stuck at a specific age or time period that may be representative to them of a significant event or emotion.

Alters within a system will often have a role or multiple roles that enable it to function cohesively. The most prominent role is the ‘host’, referring to the alter that fronts (is in control of the body) most often. They generally take care of daily activities including work and school, often with no memory of trauma, enabling them to go about daily life as normal. Though some alters are aware of their roles, it is common for hosts not to be aware of other alters, or even that they have DID until either a dramatic event brings it to light, or they are informed by a professional or someone close to them. Other roles include protectors, caretakers, and persecutors, all of which are formed from trauma. Whilst the protector's role is to protect the body from further outward abuse and trauma, the caretaker looks after the system,

often taking care of their body and the physical space around them, as well as emotionally supporting the system. Persecutors hold immense trauma and pain, often adopting maladaptive coping mechanisms. They specifically target their own system, turning abuse inwards, often believing that if they harm the system more than their abuser, the system will be strong enough to endure their abuse. It is imperative to understand that these alters are not inherently ‘evil’ and can change and learn healthier behaviours.

Introjects are alters created from external figures, often formed under the idea that if the individual were someone else, they would be able to help themselves escape or survive the trauma they are enduring. There are two main categories: A) factional (alters based on people from the external world) and B) fictional alters. For example, a female child, often surrounded by strong men, may associate strength with being male; out of a desire to protect themselves, they may create a male factional alter. Furthermore, a fictional introject may be a hero from a television show, created by an individual in order to feel stronger or simply able to survive the trauma they are experiencing. These alters may create a dissociative barrier between what is actually happening and what the child feels can happen to them, putting a separation between the trauma and the individual experiencing it.

Though the host is the alter that fronts most often, it is also possible for other alters to front via a switch – when the alter in control of the body changes. Switching is often controlled by the alter with the role of gatekeeper, which, due to their elevated amount of knowledge of the system, are also able to facilitate communication between alters and help keep specific traumas away from certain members. Additionally, it is possible for alters to be co-conscious. This is when more than one alter is fronting at once, each with partial control of the body. If an alter is closer to the front (the consciousness), they can become aware of what us going on in the body, receiving some information about what is happening in the outside world.

Despite being a disorder that forms in childhood, it is possible for alters to form at any stage of life – this is called a split. DID is a coping mechanism, meaning that if an event is stressful or traumatic enough, dissociation may reach a peak, resulting in an alter being formed in later life. However, new alters don’t always form because of trauma. They may also form due to new stress evoking responsibilities within the system’s life, such as a new job or relationship. Conversely, alters may also integrate. There are two types of integration: the integration of memories (when alters gain access to trauma, potentially going on to form one memory of life) and the integration of alters (when alters combine to become another alter).

The current treatment for DID is trauma focused psychotherapy, which proceeds in 3 stages. After stabilising symptoms and processing trauma, the aim and final stage of psychotherapy is the total integration of alters, to create a fully formed personality by removing amnesic walls. However, it is now more common for treatment to be aimed at getting a system to work cohesively, supporting them so they are able to live successful, full lives with dissociative identity disorder.

The Development of the Mobile Phone: From dream to reality, with a ‘little’

help from science

Dr Thomas, Teacher of Physics.

I sat in a group assembled of staff across the marketing, communication, financial, and science divisions of an international telecommunications company to address a problem that we faced for the future. Mobile phones were rapidly becoming the ‘must have’ accessory of the modern day, coming down in price and size, and having replaced the pager as a way of staying in touch with people wherever they may be. There were a few models being offered that would almost fit on the wrist like the nostalgic ‘Dick Tracy’ device from the 1950s comics, and the battery technology now meant that they could last for several days without charging. The quality of the sound reproduction had improved dramatically from the tinny version that we had started with, and the aerial had shrunk in some models to be only a centimeter or so in length, or had become invisible, hidden inside the device itself

But since the phone was now so successful, the question was how to continue to make sales. Nervous parents had yet to let their children enjoy the advances in communication. At current costs there was no way to expect users to buy a replacement on a regular basis, even as the technology improved.

Someone suggested that there might be a way of enabling the electronics to play simple games like the earliest ones with simple graphics and algorithms, Tetris or Worm for example. Using the improving audio system might allow different tunes to be recorded onto the phone. Perhaps the first step towards an entertainment system, certainly the beginning of an approach to making this device more than just a communication device.

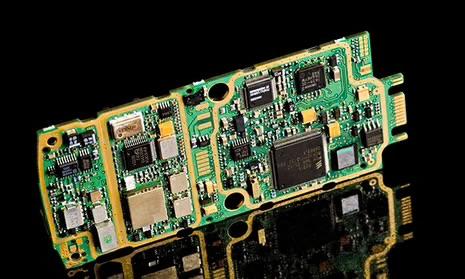

No one in that meeting, even with the greatest of imaginations, or the best awareness of what upcoming technology could offer, could have predicted that in less than two decades these devices would have more processing power than a computer of that time, nor a greater memory; a better camera quality than those used professionally, and with analysis software on par with television production companies. Of course, the greatest change across phones, however, as with so many areas of our lives, came with the smart phone’s connection to the internet, which was also on the cusp of a massive increase in versatility.

Alexander Graham Bell’s name is synonymous with the development of the first telephone, despite the many other discoveries and technologies that he pioneered. Before him, the technology of communication had already embraced electricity in the form of the telegraph to get beyond the limits imposed by the horizon. It had also increased the speed beyond the fastest horse-riding courier. Alexander brought the personal voice to the transmission process and his motivation was as personal

as it was scientific; he had met and fallen in love with a lady who was deaf and was desperate to find a way to communicate.

Many years later, the modern phone has developed far beyond the imagination of even a great scientist like Alexander Graham Bell, and this development has been driven both by advances in technology, and by the wishes of the people who use them.

Since their first development, inspired by the naturally occurring piles of alternating positive and negative charged materials found in the torpedo fish and electric eel, batteries have evolved to provide increasing energy from a decreasing size. Sodium metalhydride batteries provided rechargeable energy sources for the first mobile phones, but took up significant space and limited the available time between charging. At the time, this was acceptable, as the phone was only used for calls, and the aerial and controls, including the simple screen, were also quite big. With the introduction of ‘smart phones’, with their touch screen and much more, almost non-stop use, and the slimmer model, a new approach was needed, and this was provided by the lithium-ion battery, which has a much higher energy density and better recharge efficiency.

The use of stress in silicon chips, effectively mis-producing them, gave them better properties, and the improved battery properties enabled the mobile phones to use less efficient silicon material, rather than more complex aluminium gallium arsenide devices, which also allowed a shrinkage in size and cost. The mobile phone can now be less effective than it could have been, and still complete all that we need of it.

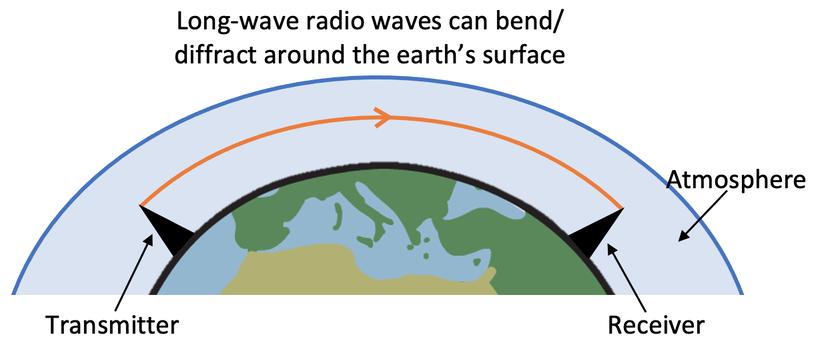

A corded telephone could carry signals using electrical current, which were produced by electromagnetic induction in the microphone and converted back into vibrations by a loudspeaker using the electromagnetic motor effect, both courtesy of ideas developed by my working-class scientist idol Michael Faraday. Switchboard operators connected a signal from the sender to the receiver one at a time. Radio communication removed the wire, and regularly-placed transmitter towers or reflecting waves at the ionosphere layer of the atmosphere, which gave it range beyond the limited power of the radio transmitter; but, the microwave’s shorter wavelength, and ability to penetrate the atmosphere, has enabled satellite communication a range and data bandwidth that far exceed the radio. In addition, the use of optical fibre to transfer an enormous amount of data between the transmitters and receivers has made the use of the internet so versatile.

The Complexities of Informed Consent in Paediatric Care

Trinity Iya Njopa-Kaba, Y12.

Informed consent is a fundamental principle of ethical and legal medical practice, ensuring that patients understand and freely agree to proposed medical intervention after being fully informed of their risks, benefits, and any other options they could explore. However, in paediatric care (regarding children), the process involved in obtaining informed consent is particularly complex. Children are generally not deemed capable of providing informed consent about medical procedures, due to their incomplete cognitive and emotional development. Thus, it is the parent(s’) or legal guardian(s’) responsibility to assume the role of decision makers on behalf of their children. Yet, as children grow and their cognitive and emotional maturity develops, their capacity to understand not just medical information, but all information given to them, and their capacity to participate in decision-making grow too; they might also actually want to make their own choices regarding their care. This can cause conflicts between the minor’s and parent’s wishes, and medical recommendations. The process necessitates a careful balance between parental authority and the evolving autonomy of the minor, creating ethical, legal, and practical challenges.

In paediatric care, parents or legal guardians are generally the primary decisionmakers for their children’s healthcare. However, here the problem lies, because this authority is rooted in the presumption that parents and guardians always have their child’s best interests at heart, and are in the best position to make informed decisions on their behalf, given their intimate knowledge of the child’s needs, values, and family context. Both of these are, unfortunately, not always true. Additionally, it is near impossible for a parent or guardian to disregard their own cultural, religious, or personal values, which might not apply to or be the same as the child in question. However, this authority is not and cannot be absolute, because there will inevitably be situations that arise where parental decisions may conflict with what medical professionals deem to be in the best interests of the child. For example, parents may refuse vaccination, life-saving treatment, or other medical interventions, due to personal or religious beliefs. In such instances, healthcare providers and, occasionally, courts may be forced to intervene to protect the child’s well-being. These situations highlight the fine line between respecting parental authority and safeguarding the child’s right to health and life.

Children's cognitive capacities and understanding of medical decisions, as well as their desire to participate in medical decisions that impact their lives, develop as they get older. Adolescents, in particular, often have the intellectual maturity to comprehend complex medical information and the emotional investment to express their own values and preferences. This evolving autonomy is increasingly recognised in medical ethics and law, placing emphasis on the idea that minors should be involved in decisions to the extent of their capacity. The concept of ‘Gillick competence’, established in English law, provides a framework for determining whether a minor is capable of giving consent to medical treatment. In accordance with this principle, people under the age of majority (being considered an adult) can consent to medical treatment if they prove sufficient understanding and intelligence to appreciate fully the ramifications of their decision. This is

significant because the concept acknowledges that a child’s ability to make informed decisions is determined by maturity, and not just age. However, this evolving autonomy can often cause conflicts to arise, particularly when a minor’s wishes diverge from those of their parents or guardians. For instance, a mature teenager may refuse a treatment that their parents want to proceed with or may request a treatment that their parents oppose (these commonly lie within the bounds of contraception and abortion). It is the responsibility of a healthcare provider to navigate these disagreements with sensitivity, often relying on ethical deliberation or legal guidance to resolve such conflicts while still prioritizing the minor’s best interests.

Clearly, this is an incredibly challenging scene to navigate. Assessing a child’s ability to take part in decision-making is subjective and context dependent, influenced by the nature and urgency of the medical issue, the child’s developmental stage, and their ability to grasp medical information. Secondly, cultural and familial values can heavily influence feelings of autonomy and authority in decision-making. It is common that, for some people, family-centred decision-making may take precedence over individual autonomy, which can lead to tensions between healthcare providers and families when addressing the child’s role in consent. Thirdly, healthcare providers need to bear in mind that involving children in decisions can be emotionally taxing. Children may feel overwhelmed by the weight of certain medical decisions, particularly in life-threatening or chronic conditions. Age-appropriate communication is critical in this situation as it helps to ensure that the child is neither excluded from the process nor burdened with decisions they are not equipped to make. There is a fine line between empowering them and causing undue stress.

To address these challenges, shared decision-making models have emerged as an effective approach in paediatric care. These models place a strong emphasis on collaboration between parents, healthcare professionals, and the child, encouraging communication that respects each party's viewpoints and responsibilities. Along with attentively listening to the child's preferences and concerns, it also gives them age-appropriate, clear information and assists parents in understanding the medical ramifications of their decisions. By involving all parties in the decision-making process, we can promote mutual understanding and trust, ultimately leading to outcomes that align with the child’s best interests.

In conclusion, the process of obtaining informed consent in paediatric care is a multifaceted challenge, requiring a nuanced understanding of the interplay between parental authority, the minor’s developing autonomy, and the ethical obligation to protect the child’s well-being. Healthcare professionals can successfully manage these challenges by encouraging open communication, carefully evaluating the child's maturity, and placing a strong emphasis on collaboration. Keeping the child's best interests at the forefront of care while upholding the rights of all parties involved is the ultimate goal.

The Plausibility of Sci-Fi Energy Shields as a New Technology: Could This Be a Real Innovation of the Future?

Stanley Bailey, Y12.

Take a moment to consider the last sci-fi movie or series that piqued your interest, or perhaps the last futuristic story in which you found yourself engrossed. Indeed, there is a greatly amusing theme commonplace among all media in the sci-fi genre, which places it as undeniably ubiquitous in today’s culture; from titles like Star Wars and Interstellar, to books such as War of the worlds, sci-fi loves to intrigue us with inspiring ideas and images of what humans of the future might resemble, and it exhibits breath-taking technologies and immense feats of both engineering and human understanding. Whether a franchise leans more heavily into the fiction than the integrity of the science, or prides itself upon its adherence to real principles of physics, we are often met with concepts that seem rather plausible as real life innovations for humanity one day to produce and refine, bringing the stories of today into reality. As someone with a great appetite and fondness for science, I find these concepts profoundly fascinating.

I have encountered energy shields as an advanced technology in a range of franchises, which I personally find to be incredibly luring and a source of immense curiosity, and this is the topic which I would like to discuss in this article.

In fiction, energy shields are a widely applicable concept for purposes ranging from use in weaponry, to space exploration, to colonies on other planets. But a question I have often asked myself is: could this technology be used for the same applications now, and successfully? Could this perhaps be the key to expanding the frontiers of humanity beyond the stars? Or, could energy shields perhaps become a new military innovation we see developed, like the laser-based weapons recently seen from the likes of the United States? The answer appears to be that this is unlikely. However, the idea itself does not seem entirely farfetched. I have considered a few possibilities for the basic mechanism of energy shields: perhaps magnetic fields could be used as a way to deflect certain hazards? Or maybe a physical barrier comprised of ions (charged particles which produce electrostatic interactions with nearby particles)? The most difficult method of producing a shield without solid material would be a true energy shield, simply using energy to protect from incoming hazards. Upon researching this topic, I discovered that I am not the only person with an interest in it. In fact, more extensive research has been conducted into this subject than one would initially anticipate.

Magnetic Fields

The crucial property of magnetic fields that makes them a potential candidate for shield technology is, of course, their ability to attract and repel, and hence move, charged particles. In space, there are a number of sources of charged particles which can be harmful to astronauts on space missions: namely, solar wind – the charged particles, present in the form of a plasma, which propagate from the sun. Research published in the journal Acta Astronautica suggests that lab tests show evidence of magnetic fields capable of forming a sort of protective barrier against solar winds. A

lab test was performed in which a magnetic field formed a magnetosphere with the plasma flowing onto it. The plasma has diamagnetic properties, meaning it produced an opposing magnetic field to the one produced in the lab, forming a barrier when captured by it, which blocked the rest of the incoming plasma. In some sense, this is a form of energy shield which protects from incident charged particles in the form of plasma. Due to the fact that the plasma used exists in outer space, this type of barrier has applications in space travel as a means of protecting astronauts from solar winds with existing materials in space.

Ion Shields

To a large extent, this type of shielding is linked to the previous idea, using magnetic fields and plasma to form a barrier against certain hazards. However, this idea focuses more on the use of the ions themselves as protection. In this sense, the previous idea could be considered a type of ion shield, with the method of production being the use of magnets. Similar to the previous idea, ion shields make use of the properties of plasma and charged particles to create a barrier against radiation, which may be absorbed, and other charged particles that may be hazardous, as their charge property allows them to repel and deflect other charged particles. An example of this technology in development is research conducted in the University of Washington in 2006, where a group experimented with the creation of a bubble of charged plasma contained by a mesh of conductive wire, which would protect against radiation and certain particles. This type of shield would have similar uses to a magnetic field shield, as they largely use the same mechanism for protection.

‘Energy’ Shields

Is it even possible to produce genuine ‘energy’ shields? This is a complex issue, but the answer seems to be no, as energy cannot be harnessed in a ‘pure’ form, but rather is transferred between stores, which determines the conditions of the object with the energy (for example, an object in motion has kinetic energy, or energy in the kinetic energy store). When researching, I was not able to find any examples of designs or research for this kind of technology.

Limitations

Clearly, this technology in reality is in very early stages of its creation, refinement, and development, so there are a number of limitations that must be addressed. Namely, most of the concepts rely on the same mechanism to protect, which may not protect from all threats. Furthermore, these designs may not be easily operated in a moving spacecraft or vehicle and may require large amounts of power to function. Hence, it would be very gratifying to see advancements in this technology, though it is largely not mainstream.

To conclude, energy shields are clearly not wholly based in fiction; while there are many improvements to be made, this technology is somewhat plausible and could be the solution to interplanetary travel! Indeed, the concept of such a well-known sci-fi idea becoming a reality is immensely exciting and a testament to the progression and growth of humanity.