A CREATIVE RESPONSE TO THE JUVENILE JUSTICE CRISIS

Abdul Aziz

Nic[o] Brierre Aziz

Adrienne Brown-David

Nya Carolington Skipper

Aubrey Edwards

Dave Greber

Robert Jones

Ivy Mathis

Demond Matsuo

Louise Mouton Johnson

COMMISSIONED ARTWORK BY ART PROJECTS CREATED WITH YOUTH, IN WORKSHOPS LED BY TEACHING ARTISTS

Pat Phillips

McKinley “Mac” Phipps, Jr.

Sheila Phipps

Nik Richard

Vitus Shell

Mariana Sheppard

Sha’Condria “iCon” Sibley

Maxx Sizeler

Charm Taylor

Breanna Thompson

Langston Allston

Jose Cotto

Cherice Harrison-Nelson

Linda A. Reno with Nic[o] Brierre Aziz

Sheila Phipps

marta rodriguez maleck

AND FEATURING

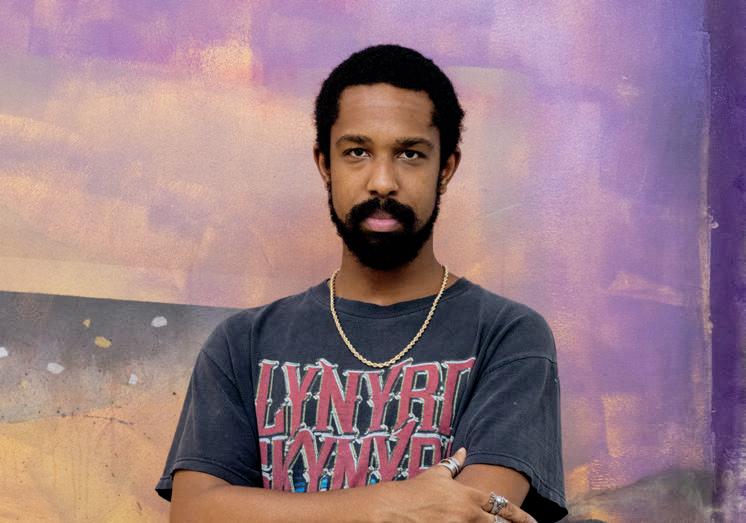

G’yanni Paris

January 21 – June 10, 2023

Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University

Unthinkable Imagination: A Creative Response to the Juvenile Justice Crisis is a collaborative exhibition steered by an advisory panel made up of Syrita Steib, Dolfinette Martin, Gina Womack, Aaron Clark-Rizzio, and Ernest Johnson and with the support of their respective organizations Operation Restoration, Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, and Ubuntu Village.

This brochure acts as a companion to Newcomb Art Museum’s exhibition Unthinkable Imagination: A Creative Response to the Juvenile Justice Crisis. It is an introduction to the community and voices involved in the exhibition, a catalogue of the artists featured in the show, an outline to the creative process, a deeper understanding behind the curatorial method, and an initial guide to the policies, history, and terms of the juvenile justice system. Just as this show has been an iterative, creative response, this brochure acts as the same, a part one to a diverse array of literature accompanying the show. We invite you to email museum@tulane.edu to sign up to be on our email list to stay in the loop about the next edition of this brochure, upcoming events, and more.

Adrienne Brown-David, detail of Run, 2022, oil paint on canvas. This artwork creatively interprets the experience of LaZariah

Unless otherwise noted, all images in this publication appear courtesy of the artists.

Unthinkable Imagination: A Creative Response to the Juvenile Justice Crisis is the second iteration of Newcomb Art Museum’s exploration of the carceral system in Louisiana. In contrast to per(Sister): Incarcerated Women in Louisiana, the lens of the curators and the community partners has been applied to youth—arguably, the most vulnerable citizens in our nation-state. Utilizing a multilayered curatorial approach and methodologies, this project strives to illuminate and make palpable an experience that remains murky, if not completely obscure, to many of us. Yet, it is done with the understanding that very few can create an artistic space and imagery that captures the depth and breadth of emotions, brutalities, and alienation that an imprisoned person might experience.

The narrative arc of this show starts with vital, contextual information for understanding Louisiana’s carceral system and shifts to a range of visual experiments developed in community spaces, and through dialogues between artists and youth, so that we can begin to envision new futures. To frame the different visual registers and artistic transitions that were developed collectively and independently, the curators and artists drew upon the words of experts— youth with direct knowledge of Louisiana’s extensive carceral system. They decided that the primary argument of the exhibition should not revolve around a sustained meditation on the injurious events. Instead, they yearned for an exploration of that which can exist in worlds beyond the humiliations of prison life and America’s failed justice system.

These dreams and yearnings of the youth participants, community partners, and curators are firmly situated in the vision for Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University. We craft each new

artistic experience to facilitate a creative exchange of ideas and provide opportunities for civic dialogue and community transformation. The exhibition has been generously supported by The Ford Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Unthinkable Imagination: A Creative Response to the Juvenile Justice Crisis would also not have been possible without the leadership of Miriam Taylor Fair, former Interim Director, and current Special Projects Curator; Laura Blereau, Curator and Coordinator of Academic Programming; Jennifer Williams, Guest Curator; Hanan Al-Bilali, researcher, and Alex Landry, Curatorial Assistant. Their curatorial vision has been supported by the entire Newcomb Art Museum staff, and particularly the efforts of Lexus Dawn Jordan, Andrew Mellon Community Engagement Coordinator; Tom Friel, Coordinator of Interpretation & Public Engagement; Sierra Polisar, Collections Manager and Assistant Registrar; Sherae Rimpsey, Andrew Mellon Art Writing and Editor; Kendra C. Thompson, External Affairs and Communications Manager; Marylin Mell, Administrative and Budget Coordinator; and Ariana T. Hall, former Finance Manager.

Syrita Steib serves as the Executive Director for Operation Restoration, an organization she started 2016 to eradicate the roadblocks she faced when returning to society after incarceration. At the age of 19, Syrita was sentenced to 120 months in federal prison. After serving nearly 10 years in prison, she was released into a community vastly different than the one she left. Cell phones and computers had evolved beyond recognition and even personal dress and social norms passed her by while she was incarcerated. Other formerly incarcerated women helped her to re-adjust to the world she had left behind. Despite her academic accomplishments while incarcerated, Syrita was initially denied admission at the University of New Orleans due to the criminal history question. Two years later she reapplied unchecked the box and was granted admission. Syrita went on to earn her BS from Louisiana State University’s Health Sciences Center in New Orleans and is a nationally certified and licensed Clinical Laboratory Scientist. In 2017, Syrita wrote and successfully passed Louisiana Act 276 which prohibits public post-secondary institutions in Louisiana from asking questions relating to criminal history for purposes of admissions, making Louisiana the first state to pass this type of legislation. In 2018, she was a co-chair for the healthy families committee for New Orleans Mayor Cantrell’s transition team. Syrita was also a panelist on the Empowerment stage at Essence Festival in 2018 and 2019. Syrita is 2020 Rubinger Fellow and Unlocked Futures Fellow, a policy consultant for Cut50’s Dignity for Incarcerated Women campaign and worked tirelessly on the passage of the First Step Act. Syrita was appointed by the Governor to the Louisiana Justice Reinvestment oversight council and is the Vice-chair for the Louisiana Task Force on Women’s Incarceration. She also helped create and was featured in the Newcomb Art Museum’s per(Sister) exhibition, which shared the stories of currently and formerly incarcerated women.

Dolfinette Martin, Housing Director at Operation Restoration, is a strong community leader. She manages all housing programming provided by Operation Restoration and supervises staff, interns and volunteers working for Operation Housing. Dolfinette earned a college degree in 2015 after her release from prison in 2012. She serves on the Formerly Incarcerated Transitional Clinic Advisory Board, a clinic created for formerly incarcerated people, as a panelist on the Criminal Background Check Review Board for the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) and as an Advocate of safe and affordable housing for people touched by the criminal legal system.

Dolfinette was appointed to New Orleans’ first female mayor Latoya Cantrell’s transition team and in 2019 was appointed to the New Orleans Audubon Zoo Board of Commissioners. She was a founding member and former president of the New Orleans chapter of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls. She is a recipient of the John Thompson Leadership for Change Award and The Graduates’ Freedom Fighter Award. Dolfinette is an equal partner in Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Museum’s per(Sister) exhibition, and was instrumental in creating the first Women’s Gathering Fellowship for women of color with the Center for Community Change and was one of the first ten cohorts. She also contributed her expertise to help create The Power Coalition’s She Leads Fellowship which also focuses on women of color doing on-the-ground organizing. Based on her legislative advocacy, Governor John Bel Edwards appointed her to sit on the Louisiana Women’s Incarceration Task Force in 2018.

Gina Womack is the executive director and co-founder of Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, a state-wide membership-based organization dedicated to creating a better life for all of Louisiana’s youth, especially those who are involved or at risk of becoming involved in the juvenile justice system. Gina is the proud mother of three children, a member of Pleasant Zion Missionary Baptist Church and Sanctuary Choir as well the Joyful Gospel Choir. She is honored to be a 2006 Petra Foundation Fellow, 2009 Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana Advocate of the Year, 2009 Ms. Foundation Women of Vision award, and 2011 Alston Bannerman National Fellow.

Ernest Johnson is co-founder of Ubuntu Village. He has a passion and energy for advocacy and volunteerism that spans a period of 10 years. He has traveled around the country speaking on navigating the criminal justice system, family engagement, and leadership building. He is a recipient of the National Juvenile Justice Beth Arnovists Gutsy Advocate for Youth award.

Aaron Clark-Rizzio is co-executive director of the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights. Prior to joining LCCR, Aaron acted as Chief of Staff and Legislative Director to New Orleans City Council member Jason Williams. There, he advised Council member Williams on a wide array of policy initiatives, including improving the conditions of detention for juveniles and reforming the District Attorney’s juvenile transfer policy. Previously, Aaron served as a staff attorney for the Orleans Public Defenders for five years, practicing client-centered advocacy and team-based defense. He is a graduate of Vassar College and New York University Law School.

The U.S. incarcerates more people than any country in the world, with Louisiana imprisoning more of its citizens, than any other state. Of the stories that circulate in the popular imagining about the impacts of the carceral system, too few are expressed by those directly experiencing the system. In January 2019, the Newcomb Art Museum, in partnership with Syrita Steib, Dolfinette Martin, Operation Restoration and Women with a Vision, opened per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana. The exhibition utilized the storytelling power of art to shine a light on one of the most critical issues facing our communities—mass incarceration. Through interviews with formerly incarcerated women, artworks from more than 30 artists, and a myriad of programs with community partners, stakeholders, and advocates, the exhibition aimed to build awareness of the situations arising, before, during, and after incarceration, as identified and expressed by those who’ve experienced it. per(Sister) sought to find common ground and new pathways for society to empathetically and equitably move forward together.

The exhibition Unthinkable Imagination is the next step on that pathway.

At the close of per(Sister), artists, advocates, activists, scholars, community stakeholders, and individuals directly impacted by the carceral system came together to discuss next steps. What role does a privileged art museum at a largely white institution play when it comes to creating programming that addresses the injustices at the center of the carceral system? From those

FREEDOM IS AN UNTHINKABLE IMAGINATION OF HAPPINESS AND JOY AND OPEN SPACE OF OPPORTUNITY.

AARON, UNTHINKABLE IMAGINATION YOUTH COLLABORATOR

conversations came a recognition of what Newcomb is—and what Newcomb isn’t. We are a contemporary art museum that engages communities both on and off Tulane University’s campus, working to foster the creative exchange of ideas and cross-disciplinary collaborations with experts of all fields from within and without the academy. We aim to operate as a “third space” on campus, where art can act as a vehicle for truth, beyond art’s sake, and towards a social and civic healing for all. We recognize that art has power beyond the visual, it touches the spiritual and in doing so can hold space for restorative moments for the soul. Beyond that, art coupled with the direct stories of impacted individuals and researched, informative texts about the state of our state can provide new avenues and access points to issues critical to our communities.

Time and again in the meetings at the close of per(Sister), conversations about the impact of the carceral system on the young people of New Orleans and Louisiana came up—driving home the importance of building awareness on this topic. Why is it that in a moral society we accept the fact that young people in desperate need of community support, access to mental health resources, and an educational system that empowers them, are locked away in jails and prisons, separated from family, friends, mentors, and the support of their communities at the time that care and connection is needed most? Why is it that the federal judge who recently approved the transfer of eight boys to be housed in the former death row cells at Angola called “locking children in cells at night at Angola… untenable,” instead of what it is—intolerable? Why do we find it okay to we lock children up?

It is important to note that this exhibition, Unthinkable Imagination: A Creative Response to the Juvenile Justice Crisis, has been in the works since 2019—before a global pandemic upended the way we work, live, and advocate; before the summer uprisings of 2020 brought to light, yet again, systemic injustices against African Americans and communities of color across the United States.

Unthinkable Imagination is a collaborative exhibition steered by an advisory panel made up of Syrita Steib, Dolfinette Martin, Gina Womack, Aaron Clark-Rizzio, and Ernest Johnson and with the support of their respective organizations Operation Restoration,

Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, and Ubuntu Village. Lexus Jordan, the museum’s Coordinator for Community Engagement tirelessly worked with directly impacted young people to center their voices and their stories—and reminded us that there is no story about young people without young people, that there is no future for Louisiana without the youth of Louisiana. From those conversations, new artwork came to being, whether directly created by the youths themselves or by artists from across Louisiana and the Gulf South interpreting the experiences of the young people through a variety of mediums. The curatorial team led by me, Jennifer Williams, Laura Blereau, and our curatorial assistant Alex Landry, weaved together these diverse stories into one collective—utilizing color, sound, and material to craft a visual language that speaks to the potential of each young person impacted by the justice system. Writer Hanan Al-Bilali aided in shaping the exhibition text throughout the show, addressing the history of the youth justice system in Louisiana, the root causes of the system, and the direct harm it does to young people and their families, while highlighting what is truly lost when we give up on the youth of our city—their humanity. Their joy.

Each young person involved in this exhibition—Jessi’, Jiyah, Aaron, Jai’Lynn, Kirious, Deshawne, Ahmad, Rashad, Taijah, Lamaj, Anika, Alella, Deontae, Christopher P., Lokell, Christopher S., Michael, Keymon, Slick, Rayqine, Raynell, Jaquan, Aamond, Donny, JyHarin, Lazariah, N’Shavia, Ronnisha, Kiore, Ne’Eviah, Semaj, Troy, Ivan, Alvin, Kyla, Aaliyah, Gyanni, Stephon, Daytanya, Zedrick, Rob, Nariya, Ivan, Jonathan, Kira, Kori and Vanti, among many others (who asked to remain anonymous)—held space for their future, their unthinkable imaginings by contributing to this show in so many ways. By lending their voices, their talents, their experiences, and their creativity they have fashioned a space for themselves within this show. A place of belonging and ownership, a place where their joy takes precedence—where their dreams are center stage. We invite you to see, hear, and feel these stories, to be reminded of what it is to be young, and to remember the pure potential that time of life informs. We hope that you to leave here changed. To be moved to

action on behalf of the youth of our state, to ensure that they have the freedom to be kids—the freedom to shape their own future.

Miriam Taylor Fair serves as the Curator of Special Projects for the Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University. She originally came to Newcomb in 2016 as the external affairs manager before stepping into the role of deputy director and finally interim director (2020-2021)—overseeing the museum through the pandemic closures. While at Newcomb, she has assisted in developing programs, events, and community partnerships and aided in producing, publicizing, and fundraising for such exhibitions as Laura Anderson Barbata: Transcommunality (2021), Brandan ‘Bmike’ Odums: Not Supposed 2-BE Here (2020), LaToya Ruby Frazier: Flint is Family (2019), per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana (2019), Fallen Fruit: Empire (2018) and Clay in Place (2018). Before coming to Tulane she worked as the communications director at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans after an early career in journalism in New York.

Fair holds a BA in Journalism and a BA in English from the University of Mississippi and master’s in Journalism from the Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. She is currently pursuing her PhD in the Urban Studies track of the City, Culture, and Community doctoral program at Tulane University where her research focuses on the intersection of engaged museum practices, identity formation, informed histories and cultural memory, with an emphasis on communities across the Gulf South. Fair is a Sawyer Seminar Fellow and Mellon Fellow for Community Engaged Scholarship. Her writing has appeared in Theory and Practice: The Emerging Museum Professional’s Journal, Cultural Vistas, 64 Parishes, the New Orleans Times Picayune | Nola.com, the Syracuse New Times, Mississippi Magazine, Yall.co, and Fast Company, among other publications.

I joined this project in April 2022 as Community Engagement Coordinator, by which time much of the groundwork had been done in forming partnerships with Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, Operation Restoration, and Ubuntu Village, allowing the steering committee to lead this work. An initial component of the project included summer art making workshops for young people, but we struggled to get engagement. Justice for young people demands real time response. This is work that cannot and should not be put on hold to maintain an exhibition timeline. Life presents its own challenges and beauty. Life can be further burdened by the bureaucratic maze and oppression of the carceral system that strains human connection. Our young collaborators were not always a phone call or text away. We reached a moment that reminded us, emphatically, that this project must continue to be grounded in youth experience and insight. To do so, we initiated a cohort of youth museum interns to participate in curation and programming of the exhibition. I’ve had the pleasure of working with the inaugural Newcomb Art Museum Youth Internship Cohort: Ne’vaeh, Ivan, Robert, LaZariah, G’yanni, Nariya, Jonathan, and Troy. It has been a beautiful experience. The collective will remain with us until the show’s end. In addition to the steering committee and community gatherings (open to participating artists, community members and organizations, youth collaborators and their families), these young people have consulted oncuratorial design, featured artworks, marketing, and programming. At every turn, we continue to ask, whose voice should be present here. How are young people centered here? And of course, when people share, making sure we listen.

This exhibition is inextricably tied to community. As an art museum, we recognize the limits of our capacity to engage in activism. As the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, we recognize our position. We accept the challenge to be good partners, good neighbors. We honor our partners and community members who are fierce advocates of young people. Most importantly, young people remain at the center of this work. We invite the most vulnerable and brilliant voices to have this conversation. Our responsibility is to center and to support those voices, to co-create space for them to tell whole stories. This exhibition may bring in all sorts of audiences with varying points of entry. We thank the voices that made this work possible.

To every young person, caretaker, community member, advocate, and artist, thank you with much gratitude and joy.

Lexus Dawn Jordan holds an MA from Louisiana State University and a BA from Xavier University of Louisiana, both in Communication Studies with a concentration in Performance Studies. Her work has been focused on using identity and cultural narratives for community advocacy.

Previously, Lexus spent over five years as a youth advocate for a local, New Orleans-based non-profit organization. Lexus has also worked as an adjunct instructor at Xavier University and Southern University at New Orleans. Lexus currently serves as the youth director and a leadership advisor to her faith-based community.

In her community work, Lexus utilizes one-on-one mentoring and group facilitation as tools for programming and teaching. In her role at NAM, Lexus expands community partnerships and relationships while working to co-create sustainable programs. Lexus is an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow.

Operation Restoration was formed in 2016 and is led by formerly incarcerated women. Operation Restoration’s mission is to support women and girls impacted by incarceration to recognize their full potential, restore their lives, and discover new possibilities.

www.or-nola.org • INSTAGRAM operationrestorationtheor

Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children is a grassroots, state-wide, membership-based, inter-generational organization working to transform the systems that put children at risk of prison. Through empowerment, leadership development, and training they strive to keep children from going to prison and support those who have and their families. From the street level to the state level, from meeting rooms to the state capitol, they are working to build a society based on the principles of racial justice, human rights, and full participation through our tireless fight for justice for youth.

www.fflic.org • INSTAGRAM fflicla

Ubuntu Village fights for social, economic, and transformational justice for children and communities. They work primarily with families of youth who are involved in the juvenile justice system. They help families advocate for their rights and those of their children by educating them and helping them navigate the juvenile system. At Ubuntu, they believe that those directly affected by incarceration should be at the forefront of efforts to reform the system. They work with parents and young people to conduct participatory action research, analyze inequities in the juvenile justice system, and advocate for changes that would make the system more humane, antiracist, rehabilitative, and just. In all our programming, they prioritize providing immediate economic opportunities to participants and families as well as developing strategies for long-term economic sustainability.

www.ubuntuvillagenola.org • INSTAGRAM ubuntuvillagenola

The Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights is a nonprofit law office that stands with kids in the justice system no matter what. As the juvenile public defender in New Orleans, they represent over 90% of children in the city who come into contact with the juvenile justice system, providing each child with a holistic team—a lawyer, social worker, investigator, and youth advocate—to address both the causes and consequences of an arrest. They also represent the majority of children in Louisiana who are facing life without parole sentences, which the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled unconstitutional in all but the rarest cases. They provide holistic legal defense to address children’s needs both inside and outside the courtroom and tackle the systemic issues that criminalize mostly poor, Black youth in the first place. Their goal is to keep kids out of a harmful system so that they can thrive where they belong—at home, at school, and in our communities.

www.lakidsrights.org • INSTAGRAM lakidsrights

Robert Jones, detail of Let’s Play, 2022, acrylic paint on canvas. This artwork creatively interprets the experience of Kiore

Robert Jones, detail of Let’s Play, 2022, acrylic paint on canvas. This artwork creatively interprets the experience of Kiore

Unthinkable Imagination: A Creative Response to the Juvenile Justice Crisis is an exhibition that gathers the experiences of Louisiana youth between the ages of twelve and twenty-two who are system-impacted, incarcerated, or formerly incarcerated. The show is a multifaceted social sculpture in flux, strengthened and nurtured by the community. It lives as a generative, restorative, and future-building space.

Our team’s selection of artists in the exhibit revolved around key ideas:

1 Only the folks who have lived in this region can truly understand and interpret the voices of New Orleans youth represented in this project.

2 Teaching artists have skills that are aligned with the goals of educators and advocates practicing care. They are sensitive to the youth mindset and a process of lifelong learning.

3 Collaborating partner organizations and youth would join us in the selection of artists and issues they raised. We’d choose artists who are strong leaders that can guide us toward a path of liberation.

4 Artists who are directly impacted by carceral systems embody wisdom and valuable insight—for the young people interviewed and academics, alike.

All the featured artists in the exhibition bear witness to the powerful change and development inherent to the human condition. They see the societal problem of punitive measures taken against children and address it holistically. The arts offer a wellness space for processing trauma, without causing further harm. We care deeply about that. The interior lives of youth are innately creative; they deserve visibility as a

healing force. Placing greater emphasis and resources into the social spaces of education and community-based programs—for treatment— is a viable alternative to youth incarceration.

In the exhibition, youth stories come to life in the hands of twentyfive artists—who engage traditional approaches in the fine arts as well as experimental techniques and technologies. These artists include intergenerational, cis, and gender-expansive identities. They come from diverse cultural backgrounds, some living in rural areas and others dwelling in cities or suburbs. As a whole, the artists use formally trained and self-taught approaches toward visual art, design, literature, and music.

Among the twenty artists paired one-on-one with youth, three stand out for their commitment to non-profit social justice work: Robert Jones, Executive Director and Co-Founder of the New Orleans youth mentorship organization Free-Dem Foundations; Ivy Mathis, an Outreach Coordinator in Baton Rouge for Voice of the Experienced, who serves on the state Council on the Children of Incarcerated Parents and Caregivers; and Abdul Aziz, Communications Director for the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana from 2006–2009 and a board member of the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights from 2013–2017. Three artists have experience as New Orleans public school system educators: Louise Mouton Johnson, Charm Taylor, and Aubrey Edwards. Nine teach Louisiana and Mississippi youth in other educational and public contexts: Sheila Phipps and her son McKinley

“Mac” Phipps, Jr., Sha’Condria “iCon” Sibley, Mariana Sheppard, Vitus Shell, Nic[o] Brierre Aziz, Adrienne Brown-David, Dave Greber, and Nik Richard. The remaining five orient their practices poetically, in different ways, to address the impact of family life, economic opportunity, and wellness on youth: Pat Phillips, Maxx Sizeler, Breanna Thompson, Demond Matsuo, and Nya Carolington Skipper.

This exhibition amplifies the voices of system-impacted, incarcerated, and formerly incarcerated youth with a display of twenty recorded audio interviews that served as source material for all of the paired artists. Our curatorial process also offered an intentional platform for creative expression via youth workshops and seized a chance to continue the arts education efforts led by several local organizations

and schools.1 In the last year of exhibition development, approximately twenty invited youth energetically painted, collaged, photographed, and verbalized their ideas in workshops led by six artists: Langston Allston, Jose Cotto, Cherice Harrison-Nelson, and marta rodriguez maleck. A few workshops occurred at the museum while others took place off-site in local artist studios. Teachers affiliated with Arts New Orleans’ Young Artist Movement, Journey Allen and Gabrielle Tolliver, facilitated the production of a monumental forty-foot collaborative

1 Ashé Cultural Arts Center, Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans Museum of Art, Antenna Gallery, Arts New Orleans, Travis Hill School at the Juvenile Justice Intervention Center, Bar None, Youth Empowerment Project, YAYA Arts, Guardians Institute,

Dance

Drum

the Woods, Better Family Life New

Recreation Development Commission, Kumbuka

Roots

Connection;

House

Annual talent shows and contests for local middle, junior high and high school students also spark a lasting feeling of joy and creativity instrumental to our exhibition, which leverages the educational and wellness resources on Tulane University’s campus.

Pat Phillips, detail of I Am My Brother’s Keeper / Matter Of Fact, You Going To Have Your Business... 2022-2023,

mural by Langston Allston, which hangs as a visual centerpiece of the exhibition. Prior to 2022, The Travis Hill School, located inside of New Orleans’ juvenile detention center and adult jail, served as the site of independent art workshops led by Sheila Phipps, Linda A. Reno and Nic[o] Brierre Aziz.

A paid internship program started by Newcomb Art Museum’s community engagement coordinator, Lexus Dawn Jordan, resulted in youth-led exhibition design strategies, including programming and messaging. For example, interns chose the bright neon colors in the exhibition’s palette, marking the popularity of sneaker and fashion design among this age group, and the influence of digital RGB screen-based color

schemes. This program was open to all young people represented in the show through interviews, plus 7th to 12th graders who are systemimpacted. Seven of the interns worked with artist marta rodriguez maleck on the design of plush sculptures that contain magical symbols carrying their ambitions, joys and wishes for the future. The exhibition also features paintings and impactful words of youth at the Travis Hill School who participated in a workshop with Sheila Phipps in 2017, two years prior to the start of our exhibition’s curatorial process. Unthinkable Imagination, the exhibition’s main title, was drawn from a statement written by a young man participating in Phipps’s Steps to Freedom workshop while she served as the inaugural artist-in-residence for Bar None, a non-profit organization dedicated to transcending incarceration. Answering the question, “What is freedom?” he wrote: Freedom is an unthinkable imagination of happiness & joy and open space of opportunity. Additionally, the exhibition debuts a series of collaborative portrait photos that Linda A. Reno and Nic[o] Brierre Aziz created in an independent workshop with youth at the Travis Hill School in March 2020, just prior to the pandemic lockdown.

Some of the most challenging decisions and moments we faced while developing this exhibition grew from a desire to protect youth privacy rights. Interviews were gathered at informal spaces with the presence of social workers, counselors, or loved ones. Legally, parents and guardians control the circulation of images and likenesses of children under their care, up to age eighteen. We chose NOT to photograph most of the young people who shared their stories with us, and instead made audio recordings (with the proper permissions) to serve as primary documents to represent the youth. In some situations, personal information was redacted or obscured, when it was passed along to artists or colleagues. These and other concerns informed the museum’s visitor policy for the exhibition—such as discouraging photography in certain areas of display.

Because the content of this exhibit is complex and emotionally heavy at times, a printed Care Guide for all visitors contains wellness resources, a chronological timeline of juvenile incarceration in Louisiana, creative prompts and texts. Spaces for contemplation or

reading are placed throughout the exhibition. Multiple sites invite participation and reflection, for centering youth experiences.

At the museum entrance are artworks establishing the exhibition’s central themes of perseverance, hope, and creative transformation. Through audio clips, visitors are introduced to the interviewed youth who name personal heroes and offer gratitude for people who nurture them. In the adjacent gallery, a room titled Root Causes presents information on the school-to-prison pipeline and systemic inequities shaping Louisiana’s high rates of youth incarceration. Accompanying art and audio recount the challenges confronting specific youth and their families. In the next room titled To Do No Harm, youth narrate how they’ve coped with the conditions of confinement and navigating the juvenile legal system. The art in that space largely focuses on resilience and the full humanity of childhood.

In the larger rear gallery are a variety of objects and sound pieces that center belonging and the artistry of young people. It presents imagery created in workshops facilitated by Arts New Orleans, the City of New Orleans, Travis Hill School, and the Newcomb Art Museum. Here, youth share their joys of discovery and strengths, while also envisioning how to build a world where young people are not imprisoned.

How can understanding the stories of detained Louisiana youth help us create a more just world? We welcome your response to Unthinkable Imagination, as programming unfolds through June.

Edward Buckles, Jr. Katrina Babies, documentary film, Invincible Pictures and Time Studios, 2022.

Rosa Ruth Boesten and George Anthony Morton. Master of Light, documentary film, Vulcan Productions and One Story Up in collaboration with Docmakers, 2022.

Nicole R. Fleetwood. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2020.

Ava Duvernay. 13th, documentary film, Kandoo Films, 2016.

Hans Haacke. Unfinished Business, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2016.

Simone Leigh in collaboration with Stuyvesant Mansion. Free People’s Medical Clinic, Weeksville, Brooklyn. Creative Time, New York, 2014. https://creativetime.org/projects/ black-radical-brooklyn/artists/simone-leigh/.

Michelle Alexander. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness New Press, New York, 2010.

Adverse Childhood Experiences, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. https://cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/index.html.

Pulitzer Center Programs for K-12 Teachers and Students. https://pulitzercenter.org/education.

Jennifer M. Williams has more than twelve years of experience producing multidisciplinary public arts programs. She is currently the Program and Outreach Coordinator for Art Papers in Atlanta. Previously, Williams has held the positions of Communications Manager for Alternate ROOTS, Public Programs Manager at the New Orleans Museum of Art, and Deputy Director for the Public Experience for Prospect.4. For six years, she served as Director and Curator of the George and Leah McKenna Museum of African American Art in New Orleans. Williams is committed to contributing to the cultural and artistic landscape locally, regionally, and internationally. She supports and serves on various committees and boards including Junebug Productions and A Black Creative’s Guide. She has participated in and led a variety of experiences, including the Lagos Biennial Curatorial Intensive and the Urban Bush Women Leadership Institute. Jennifer received her BA in History from Georgia State University.

Laura Blereau is the Curator and Coordinator of Academic Programming at Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, where she creates exhibitions that highlight women artists and socially engaged art practices. Since coming to Newcomb Art Museum in 2017, Blereau has curated and co-curated several exhibitions, such as Metamorphoses: Highlights from the Permanent Collection (2022), Jess T. Dugan: To Survive on This Shore: Photographs and Interviews with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Older Adults (2022), Core Memory: Encoded (2022), Laura Anderson Barbata: Transcommunality (2021), Brandan ‘Bmike’ Odums: Not Supposed 2-BE Here (2020), per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana (2019), Fallen Fruit: Empire (2018) and Clay in Place (2018). A participant in the 2011 Curatorial Intensive program at Independent Curators International, Blereau holds an MFA in New Forms from Pratt Institute and a BFA in Painting from Louisiana State University.

2022, Acrylic paint on wood

Together, Towards Freedom is a mural created by lead artist Langston Allston and twelve young artists from the YAM team. The mural depicts the harm of incarceration and the reimagining of a brighter future. Seen throughout the mural are messages of youth experiences in their day to day lives, and the history from which these issues are rooted. The first panel of the mural represents the slave trade, the beginning of the United States’ brutal policies, then transitions into a depiction of the terror and distrust that police and prisons inflict upon our communities today. Here people are fleeing police, followed by the stark landscape of a prison.

This bleak imagery is interrupted by an embrace, meant to show the power of community care. Behind this embrace, the same prison is now crumbling and overgrown. The next three pink panels illustrate a world being carved out of the rubble of the prison, with overgrowth turning into a flowering garden that can support a community. Woodcuts from the youth artists are placed throughout the piece to underscore specific historical moments. These moments are shared to showcase what brought our society here, and specific steps which can help to escape the current structures. The process of arriving at this design has taken several different forms. The YAM team started by drawing and discussing how they wanted to portray

a world without prisons. Artists elected to create a narrative arc that brought viewers from the roots of the prison system into a future without it. To that end, the mural begins in the dark of night and concludes with the sun setting on a new day.

Langston Allston (b. circa 1992, Urbana, IL; based in New Orleans, LA) is an artist and muralist. His work tells stories and explores hidden histories using a process of site-specific research and installation. Allston has created several public projects and collaborative murals in New Orleans including the Andre Callioux memorial at St. Rose de Lima church on Bayou Road, and the NOCCA Institute Homer Plessy memorial mural, with lead artist Ayo Scott. In 2018, his work was the subject of a solo exhibition with the National Public Housing Museum in Chicago. Allston’s paintings have also been presented at the Museum of Contemporary African Diaspora Art in Brooklyn and featured locally by Paper Monuments and the Contemporary Arts Center. His work has also been supported by an artist residency at the Joan Mitchell Center. He earned a BFA in painting at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 2014.

www.langstonallston.com •

langstonallston

Langston Allston with Young Artist Movement (YAM) youth artists Jessi’ Cage, Jiyah Davenport, Aaran Hogan, Jai’Lynn Allen, Kirious Anderson, Deshawne Cornelius, Ahmad Lumar, Rashad Bakewell, Taijah Thomas, Lamaj Mathis, Anika Binalla, Alella Binalla, John Davillier. Detail of Together, Towards Freedom, 2022, acrylic paint on wood. Journey Allen, YAM Lead Arts Educator. Gabrielle Tolliver, YAM Program Coordinator. Courtesy of the artists, The City of New Orleans Percent for Art Program, Arts New Orleans, and Newcomb Art Museum.

Langston Allston with Young Artist Movement, documentation of the creation of Together, Towards Freedom, Summer 2022. Photos by Jose Cotto, Gyanni Paris, Lexus Jordan, and Charlotte Milliken.

Langston Allston with Young Artist Movement, documentation of the creation of Together, Towards Freedom, Summer 2022. Photos by Jose Cotto, Gyanni Paris, Lexus Jordan, and Charlotte Milliken.

In a Landscape Without Prisons, We Feel. 2022, Archival pigment prints

“Close your eyes and imagine waking up to a landscape without prisons. What feelings rush through your body as you walk through your front door and into this world? What shifts are visible in your immediate community? Who do you see and don’t see? What scents and sounds fill the air? How are people able to move, commune, and exist differently in this environment? How are you different in this landscape? How does it feel to be—here?”

These are images of Young Artist Movement participants who worked with artist Langston Allston on a community mural. The photographs resulted from guided meditations, conversations, and reflections on how we might physically, emotionally, and spiritually experience the world around us differently, in a society that rejects carceral systems. After discussing the themes and imagery explored in their collaborative work, I invited everyone to close their eyes and allow themselves to go through the motions of a full day, taking as much time as they needed, to inhabit a New Orleans without prisons. Once they returned to the space, we made these portraits to document their journey and capture the feelings that emerged from the process.

JOSE COTTOJose Cotto (b. 1989, Worcester, MA; based in New Orleans, LA) is an interdisciplinary artist and designer who grew up in Great Brook Valley. His creative practice explores relationships between people, place, and time—and often integrates poetry, carpentry, architecture, mark-making, and lens-based media. Cotto’s work has been featured by Paper Monuments, Antenna Gallery, and the Contemporary Art Center; and recognized by artist residencies at the Joan Mitchell Center and A Studio in the Woods. Calling New Orleans home since 2012, Cotto earned a Master’s of Architecture from Tulane University in 2014, following his studies at University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He is a 2018 Salzburg Global Seminar Cultural Innovators Fellow. In his current role at the Albert and Tina Small Center of Collaborative Design, Cotto leads a seminar course on public space in New Orleans, working with Tulane students to explore critical connections between our built environment and social fabrics.

www.jccotto.space • INSTAGRAM jccotto

The Circle of Life

2022, Photo collage

This project was supported by the Tulane University Mellon Program for Community Engaged Scholarship.

In The Circle of Life, I include pictures of my favorite people (my cousins) and sunsets. The Circle of Life also includes pictures from the photography workshop with Jose Cotto where we captured other young artists making the mural. I wanted to show progress. Everything in my collage shows progress of people, nature, and things that are happening in life.

G’YANNI PARISBox of Love

2022, Shadow box with feather, charms, jewel stones

This project was supported by the Tulane University Mellon Program for Community Engaged Scholarship.

My pieces are inspired by my favorite things. I like sunsets. Sunsets are beautiful and change colors from day to day. My favorite sunsets have a little bit of blue and purple which are my favorite colors. I use those colors as the center of The Box

of Love. Queen Reesie taught me to sew a jewel patch and encouraged me to tell my story through her workshop. The peacock feather and “princess” charm represent who I am.

G’YANNI PARISG’yanni Paris, youth participant in a creative-expression workshop led by artist Cherice Harrison-Nelson, Box of Love, 2022.

G’yanni Paris, youth participant in a creative-expression workshop led by artist Cherice Harrison-Nelson, detail of Box of Love, 2022.

G’yanni Paris, youth participant in a creative-expression workshop led by artist Cherice Harrison-Nelson, detail of Box of Love, 2022.

Cherice Harrison-Nelson (b. 1959, New Orleans, LA; based in New Orleans, LA) is a leader of the African-American Carnival dress art tradition which uses narrative beadwork, dance, featherwork and chanting with percussive instrumentation. She is the third of five generations in her family to participate in this authentic New Orleans art form, a ritual handed down from her late father, Big Chief Donald Harrison, Sr. She is perhaps best known locally as Maroon Queen “Reesie” of the Mardi Gras Indian Tribe Guardians of the Flame. A co-founder and curator of the Mardi Gras Indian Hall of Fame, Harrison-Nelson has published four books and coordinated numerous exhibitions focused on our region’s West African-inspired cultural expressions. Her work is part of the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Museum and has also been recognized by a 2016 USA Artist Fellowship, a Fulbright scholarship and an award from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities.

www.joanmitchellfoundation.org/cherice-harrison-nelson

Photo by Michael Weintrob

Photo by Michael Weintrob

Wishes That Come True

2023, Embroidered soft sculpture; fabric, foam, thread

I think of myself as a transdisciplinary builder and artist with a background in construction, conversation, and filmmaking. My process starts with questions related to personal experiences and perceptions as a way of considering our singular selves as part of a greater whole, within a sociopolitical context.

In Fall 2022, I spent an afternoon with four young adults in the museum’s youth internship program, talking about ambitions, joys, and hopes for the future. We wrote our wishes for the coming years and used letters within those sentences to create sigils or coded symbols whose meaning is known by those who created them.

During their next group meeting, one of these super-inspiring youth interns led the same exercise for three additional participants, who were also interns. The personalized designs they created became the embroidery on each of the pillows that the youth will take home at the end of the exhibition, as their daily reminder of their wishes that can come true.

MARTA RODRIGUEZ MALECKmarta rodriguez maleck (based in Philadelphia, PA and Bulbancha / New Orleans, LA) is a builder working at the intersection of conversation, archives, documentary, and visual mediums including performance and sculpture. By creating environments of open mindedness and self-reflection, they engage people in participatory methods of storytelling that center comfort, communal accountability, healing, and understanding. rodriguez maleck has exhibited at the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the Pensacola Museum of Art, the New Orleans Public Library, Chicago’s Hyde Park Art Center, Baby Blue Gallery and Anas Galley in Chicago, AnyTime Dept in Cincinnati, and Ground Floor Gallery in Brooklyn. Their bi-monthly podcast, Reports from New Orleans, was featured on Montez Press Radio in New York, and their work has been featured in New American Paintings, Burnaway, OnCurating, LVL3, Bad at Sports, and Bust, among other publications. www.martarodriguezmaleck.com

2020, printed 2022, Archival pigment prints

In the process of creating these portraits, the young men were asked to define their ideal space. They were asked to define what that space would look like, what songs would be playing, who would be present, and what they’d be wearing. While we could not actualize all aspects of their desired idyllic places, by simply asking the questions, we were able to help create a mindset conducive to their own visions of what freedom feels like. We gave the youth clothing to mask the orange jumpsuits that mark their incarceration, so that they were able to unmark themselves for the portraits.

As a teacher, I already had a previous relationship to many of the students as an Artist-in-Residence for Travis Hill Schools. We had a comfortable and familiar rapport—a true human connection that allowed us to create bold unique portraits. However, the images don’t define them. Rather, they serve as interpretations of who these young men were in that moment, in that space. An opportunity to see the young men beyond their circumstance.

LINDA A. RENOLinda A. Reno (b. 1981, Detroit, MI; based in New Orleans, LA) is an American photographer, storyteller and educator. She is a graduate of the University of Texas at Austin where she earned an MA in Photojournalism. Reno is a visual storyteller using still photography, videography and multimedia production. She works as a youth photography educator and is particularly fond of this type of work. Her personal work focuses on documenting and exploring the manifestation of ancient collective memory within culture. Reno was born in Detroit, but early adulthood brought her down below the Mason-Dixon line and she has never looked back. The sights, sounds, smells, tastes, textures, and culture of the Global South inspire all her work. Throughout all her endeavors, it is this visceral sense of culture that she seeks to both reveal and revel in.

www.larenophotography.com • INSTAGRAM prettyreindeer

“I feel like I’m back at home” is a quote that rings deeply in my subconscious whenever I think about my experiences with the Travis Hill School. I distinctly remember one of the students saying this as he tried on one of my jackets for his portrait. Notions of “home” and what creates this feeling, in relation to how our sense of home impacts how we show up in the world as individuals, were central ideas to this project and my practice in general as an artist. This was undoubtedly one of the most memorable projects I’ve ever been a part of—a chance for the Travis Hill students to “see themselves beyond” the orange jumpsuit they’re forced to wear every day. Those jumpsuits only amplify the layers of oppression you feel from the moment you walk into the building—so to use art as a means of combatting those barbaric vibrations is something that I will cherish. I so vividly remember the expressions of joy and excitement from the students as they tried on the different clothes. This project was especially resonant for me as an artist, as my practice has centered around exploring the ways in which Blackness exists as a construct, experience, and colonial-capitalist tool. As I reflect upon these young Black men—these beams of light—I can’t help but think about the ways in which their bodies are being used to perpetuate the carceral system. And of the oppression and exploitation that is the literal root of this country’s wealth—this country that is supposed to be our home.

NIC[O] BRIERRE AZIZ

Nic[o] Brierre Aziz (b. circa 1990, New Orleans, LA; based in New Orleans, LA) is an interdisciplinary artist of Haitian and American heritage. He describes his work as a historical-pop culture assemblage, drawing on existing narratives and materials to create a new narrative. His practice is community-focused and reimagines the collective future. Aziz’s work has been recognized by several awards,

including a 2020 Andy Warhol Foundation Curatorial Fellowship and 2021 Joan Mitchell Center Artist Residency. He has led numerous community-based projects with the Prospect.5 New Orleans triennial, Office of Mayor Mitch Landrieu, YAYA Arts Center, Arts New Orleans and most recently the New Orleans Museum of Art. He also manages the Haitian Cultural Legacy Collection, a collection of over 400 Haitian artworks started by his maternal grandfather in 1944. Aziz holds a BA from Morehouse College in Atlanta and an MSc from the University of Manchester in the UK.

www.nicbrierreaziz.com •

2017, Twenty paintings; acrylic paint and pencil on canvas boards

This project was supported by Bar None.

In 2017, Sheila Phipps conducted the Steps to Freedom workshop at The Travis Hill School, located inside of New Orleans’ juvenile detention center and adult jail. This workshop offered space for creative expression, primarily through painting and writing.

Unthinkable Imagination, the exhibition’s main title, was drawn from a statement written by a young man participating in Phipps’s workshop.

Sheila Phipps (b.1957, New Orleans LA; based in New Orleans, LA) is an activist and self-taught artist best known for her stunning portraits and creative workshops. In her practice, Phipps addresses issues of justice and engages visual strategies that raise consciousness, empower, and educate. In 2017 Phipps became the first artist in residence at Bar None, a multidisciplinary initiative that aims to transcend incarceration by offering opportunities for healing through the arts to people who are directly impacted by the carceral system. Exhibited internationally, her work was featured in States of Incarceration, a 2016 traveling project of the Humanities Action Lab. Her work has also been presented locally at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Antenna Gallery, and Newcomb Art Museum. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including prizes from the National Conference of Artists and the National Arts Program in New Orleans. www.sheilaphipps.com

The 2022-2023 Newcomb Art Museum Youth Internship Cohort selected twenty of the Steps to Freedom paintings and designed their layout for the exhibition.

Steps to Freedom, 2017. Created by anonymous youth at the Travis Hill School, who participated in a creative-expression workshop led by artist Sheila Phipps. Pictured above: twelve of twenty paintings; acrylic paint and pencil on canvas board.

On October 18th, 2022, eight young people were transferred from the youth detention center in Bridge City to Angola Prison2—a maximum-security prison for adults located on the same grounds as a former plantation.3 Most Juvenile Justice systems nationally are moving towards models that center the needs of children, such as closer proximity to caregivers, mentors, mental health services, and appropriate educational support. The state of Louisiana continues to enact policies that leave the state’s most vulnerable children with fragile support systems. Despite the continuation of harmful practices that impact young people, communities have continued to be at the forefront of comprehensive reform. Through grassroots organizing, legislative advocacy, and community care, youth, families, and communities have continued to dream and create generative places for young people to gain access to the resources they need to be successful—despite the odds.

In 1989, the United Nations Human Rights Commission ratified the Rights for Children.4 It states that every child deserves the right to proper nutrition, shelter, and to be children. 5 In 2022 The state of

1 Omo Obatala Egbe Inc. 24th International Orisha Conference, October 29, 2022.

2 Paul Murphy / Eyewitness News, “Angola Receives the First Wave of Bridge City Juvenile Offenders,” wwltv.com, October 18, 2022.

3 Louisiana State Penitentiary.

4 The United Nations defines a child from birth until the age of 18.

5 “Convention on the Rights of the Child.” n.d. UNICEF.

Louisiana ranked 49th in the nation as it relates to the overall quality of life for its young people.6 Massachusetts ranks first, followed by New Hampshire and Minnesota. Mississippi (48th), Louisiana (49th), and New Mexico (50th) are the three lowest-ranked states.7 Children and their families are at even greater risk once they enter the Juvenile Justice System. Youth who have had contact with the court system overwhelmingly suffer from mental illness or other challenges, ranging from learning disabilities to a history of trauma. Due to the gaps in services such as preventative mental health support and educational resources, the Juvenile Justice System often ends up being a landing place for the state’s most vulnerable.

6 https://www.aecf.org/interactive/databook?l=22

7 Ibid.

Children of color, especially Black children, are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system. Despite Black youth being only 40% of the population in the state—they comprise 70% of the youth in nonsecure care and 80% of the youth in secure care.8 This creates an environment where young people are removed from their communities when they need support the most. Secure care, the deep end of the juvenile justice system, is reserved for those youth deemed to be a risk to public safety and/or not amenable to treatment in a less restrictive setting.9 Youth are monitored 24 hours a day by Office of Juvenile Justice (OJJ) staff and cannot leave the facilities. As opposed to non-secure facilities that are less restrictive,

8 “Louisiana DMC Update 2019 - Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency ...”

Accessed December 7, 2022. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/media/document/ la-fy18-dmc-plan_508.pdf.

9 https://ojj.la.gov/serving-youth-families/youth-in-secure-care-facilities/

it is often the next step before a young person returns home. Although both options were designed to provide rehabilitation, these facilities are often retraumatizing.

Despite the overwhelming needs of young people impacted by the juvenile justice system due to lack of funding, many basic needs are not addressed while in custody. Many states with similar incarceration rates have moved towards a community-centered model based on cost alone. In the state of Louisiana, it costs $155,000 to imprison a child, while only $11,000 is designated for public education.10 Although alternative care options have been passed through state legislation, the reform efforts have been underfunded or lacked proper state oversight to be implemented successfully.

In 1916, the Baton Rouge State Times reported that an eight-yearold black boy was sent to Angola Prison for Adult Men for stealing canned goods.11 Despite the Juvenile Justice Movement that began in the early 1900s, Black children across the state of Louisiana continued to be sent to adult prisons until 1948.12 In 2022 children in Louisiana still experience high rates of poverty, inadequate schools, and a lack of appropriate resources that make them more susceptible to encountering the juvenile justice system. Much of what is seen in current incarceration trends for children results from a history of violence and structural racism in Louisiana. In general, many

10 “A Youth Justice Disaster.” Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://www.fflic.org/a-youth-justice-disaster/.

11 Whitney, Sabrina Michelle, “Juvenile justice in Louisiana: an exploratory study of trends surrounding juvenile incarceration” (2012). LSU Master’s Theses. 4138.

12 Ibid.

BECAUSE IT WAS NEVER BUILT TO PROTECT US. IT STARTED AS SLAVE CATCHERS, LIKE YOU SAID. SO I DON’T TRUST THE POLICE SYSTEM. I DON’T TRUST THE JUSTICE SYSTEM. I DON’T TRUST NONE OF THEM. I DON’T.

ALVIN RICHARD, UNTHINKABLE IMAGINATION YOUTH COLLABORATOR

THE DISTRICT ATTORNEYS. THE WAY THEY TRY TO PROSECUTE US AS IF WE’RE JUST MONSTERS.

DAYTANYA, UNTHINKABLE IMAGINATION YOUTH COLLABORATOR

policies that impact families make being a child difficult, disrupting opportunities for a child to develop agency over their own lives.

Despite the lack of follow-through on ACT 1225, local activists, community members, and people impacted by the system have continued to write policies and advocate for safe spaces and opportunities for young people affected by the juvenile justice system. In 2020 eighty community stakeholders—including youth, organizers, and business leaders from various sectors—came together to dream and devise a road map for the future of young people in New Orleans.13

From this convening, the “Youth Master Plan” was conceived. This plan addresses a wide range of issues that impact young people and is a regional example of what is possible when youth voices are prioritized in imagining their own future.14

High rates of poverty and a lack of appropriate resources make the children of Louisiana more likely to encounter the juvenile justice system. The current landscape regarding the quality of life for children and their families in Louisiana is bleak. According to data collected by the Louisana Budget Project, the state ranked the highest in overall poverty in the nation.15 Child poverty was 26.7% in 2021. More than 146,000 children lived in deep poverty or below 50% of the official poverty line.16 A report by Save the Children on child well-being ranked Louisiana at 50th regarding their quality of life.17 These findings were based on child malnutrition, education, teen pregnancy, and early childhood deaths.

These high rates of poverty lead to a host of other problems, leaving schools throughout the state unable to meet the needs of their students academically. Along with the lack of access to essential academic resources, punitive policies further harm children of

13 The Youth Master Plan is facilitated by the New Orleans Children and Youth Planning Board (CYPB), the New Orleans Youth Alliance (NOYA), and the Mayor’s Office of Youth and Families (OYF).

14 “What Is the Youth Master Plan?” CYPB Youth Master Plan.

15 https://www.labudget.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/LBP-Census-2021Released-2022-2.pdf

16 Ibid.

17 “The Land of Inopportunity - Save the Children USA.” Accessed December 7, 2022. https://www.savethechildren.org/content/dam/usa/reports/advocacy/us-childhood-report-2020.pdf.

color. In one year alone, 41,689 black students were suspended from public schools in Louisiana.18 School suspensions or expulsions due to acting out or misbehaving are often unidentified or undiagnosed mental health diagnoses or developmental issues. In 2019 a lawsuit was brought against the Louisiana Department of Health for not providing proper mental health care for children on Medicaid. Instead of offering appropriate mental health services, the state has relied on psychiatric hotels and prisons to fill in the gaps.19 Because of historical and systemic inequity, children suffer the most from the government not prioritizing their needs. They are at the mercy of the state.

AS A YOUNG MAN, I WAS IN THE YOUTH STUDY CENTER. THAT SYSTEM DID NOT MAKE ME BETTER; THAT SYSTEM ACTUALLY HARDENED MY HEART EVEN MORE. AND IT TOOK OUR COMMUNITY FROM WHERE I WAS FROM, IT TOOK MY CHILDREN, IT TOOK ALL THOSE PEOPLE TO HELP [GET] ME ON THE RIGHT TRACK. I KNOW HAD I HAD A CITY THAT HAD MY BACK, IF I HAD PUBLIC OFFICIALS THAT HAD MY BACK, I WOULD HAVE BEEN BETTER EARLIER.

KEVIN GRIFFIN-CLARK, FAMILIES AND FRIENDS OF LOUISIANA INCARCERATED CHILDREN

I THOUGHT IT WAS A DREAM. I THOUGHT I WAS GOING TO WAKE UP AND JUST BE BACK AT HOME, GETTING READY FOR SCHOOL ... WHEN I WOKE UP IN THE HOLDING CELL, THAT’S WHEN IT REALLY SET IN.

SEMAJ, UNTHINKABLE IMAGINATION YOUTH COLLABORATOR

18 Harper, S. R. “[PDF] Disproportionate Impact of K-12 School Suspension and Expulsion on Black Students in Southern States: Semantic Scholar.” Undefined, January 1, 1970.

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Disproportionate-Impact-of-K-12-SchoolSuspension-Harper/eeecca31a7ff960881a8481facadb03367279785.

19 Brad Bennett Interim Editorial Director. “SPLC Sues Louisiana for ‘Nonexistent’ Mental Health Services for Medicaid-Eligible Children and Families.” Southern Poverty Law Center, November 7, 2019. https://www.splcenter.org/news/2019/11/07/splc-sues-louisiana-nonexistent-mental-health-services-medicaid-eligible-children-and.

The juvenile justice system in America was created to protect and rehabilitate the state’s most vulnerable children. However, the relationship between children and the criminal justice system has been more harmful than helpful. The most recent example is the “War on Drugs” impact on juvenile justice laws throughout the 1990s. This shift in priorities criminalized hundreds of thousands of young people nationally. By the early 2000s, evidence had shown that incarceration is, in general, especially harmful for young people and their families. Advocates and policymakers began centering the developmental needs of children, and more holistic models of care were made available. Despite the success of these new models, the

McKinley “Mac” Phipps, Jr., detail view of IPSISSIMUS, 2023, acrylic paint on canvas. This artwork creatively interprets the experience of Troy

McKinley “Mac” Phipps, Jr., detail view of IPSISSIMUS, 2023, acrylic paint on canvas. This artwork creatively interprets the experience of Troy

state of Louisiana continues to implement destructive policies and decades of failed promises.

In 1998, there were 2,000 children incarcerated in the state of Louisiana. That summer, a lawsuit was brought against Tallulah Prison by the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana (JJPL) stemming from accounts of abuse to children who resided at the facility.20 The work of JJPL, alongside many of the clients and their families, would result in the closing of the Tallulah Youth Detention Center. As a result of the organizing by JJPL, alongside many of the clients, Families, and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children was created.21 Through organizing a statewide coalition, not only was Tallulah closed but in 2003, ACT 1225 was passed. At the time, it was some of the most important juvenile justice legislation in the state of Louisiana to date.

ACT 1225 not only called for the closing of certain prisons and additional oversight, but more rehabilitative measures to be implemented, such as resources being funneled back into the community. Despite the legislation’s passing, the new law’s promises failed to be actualized—though there were significant decreases in youth incarceration at detention centers. Still, conditions were dangerous for children. As recently as 2021, two of the largest detention centers were deemed “structurally unfit” to implement the best practices outlined in ACT 1225.22 Due to the lack of funding, most changes did not happen.

Detention centers continue to be plagued with high staff turnover, which contributes to a lack of proper supervision for the young people in the facility. This gap increases the possibility of assault by other inmates or correctional officers while in custody. The state-run detention centers also lack adequate mental health and educational services, which are critical for community re-entry and is a legal right for minors. Education and career readiness are

20 “Act 1225 Mapping Project.” Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://www.fflic.org/act-1225/.

21 Ibid.

22 “Next for Louisiana Juvenile Justice Reform? Improve Safety and Oversight at State’s Outdated Facilities.” The Advocate, March 4, 2019. https://www.theadvocate.com/ baton_rouge/news/crime_police/article_6986dd4e-3c62-11e9-b929-afd5d245d409. html.

essential indicators of long-term success for all young people. A recent report released by the Center for Louisiana’s Children’s Rights highlighted unconstitutional gaps in educational attainment in detention centers. Youth in custody are being denied fundamental rights to education—namely compliance with requirements of young people who have special education needs, adequate plans for transition out of the facility, and overall consistency in services.23 Detained youth reported going weeks and sometimes months without being in school.

The “Missouri Model” is a successful method of care that has seen results locally and nationally and was an integral part of ACT 1225. The legislation outlined plans for smaller facilities closer to the youths’ communities, coupled with coordinated care around mental health, as well as medical and educational institutions. The promises of ACT 1225 have continued not to be prioritized by local and state governments. Developmentally, children need caring adults to serve as role models and support. Instead, the current policies continue to disrupt a child’s ability to prepare for adulthood, leaving young people further traumatized and with fewer options once they return to their communities.

Despite the clarity and vision of the young people in the state of Louisiana, the juvenile justice system and other government-led institutions continue to shape the experiences of young people throughout the state without their input. Regardless of the missed opportunities of state

23 “Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights.” Louisiana Center for Childrens Rights. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://lakidsrights.org/.

I WAS FEELING HAPPY, BECAUSE [I WAS] GOING HOME TO MY FAMILY WHERE I WAS SUPPOSED TO BE AT AND NOT IN NOBODY’S SYSTEM.

ZEDRICK, UNTHINKABLE IMAGINATION YOUTH COLLABORATOR

THE CHILDREN AND YOUTH OF NEW ORLEANS ARE NOT BROKEN OR DAMAGED. WE CAN RISE ABOVE CIRCUMSTANCES AND HAVE THE ABILITY TO DEFINE OUR OWN PATH

JOHN D., NEW ORLEANS CHILDREN YOUTH PLANNING BOARD (YOUTH ADVISORY BOARD MEMBER)

government, the advocates and community-based organizations have remained committed to upholding the dignity of children.

Youth and their communities already have envisioned a pathway to justice. This understanding is happening within a larger national cultural shift. Court systems that work directly with social service agencies to provide mental health services and restorative justice have been integrated into the court system and schools. More collaborative responses between various sectors have proven effective, impacting hundreds of thousands of young people throughout the United States. Solutions are present. Space needs to be created for young people and their families’ voices to be elevated.

Coordinated care and community-based solutions have long provided solutions that work for the youth in the form of Louisiana. ACT 1225 has given the state Government a roadmap of what sweeping change could look like for the juvenile justice system in Louisiana.

Local organizations have continued to advocate for things that they know are working.

Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children, Operation Restoration, Ubuntu Village, and Center for Louisiana’s for Children are leading the charge for a better way to protect the state’s children. The solutions are embedded in the voices of the youth and the community.

Hanan Al-Bilali has committed her career to supporting Black and Latinx communities through arts, education, and mentorship.

Al-Bilali is currently a Ph.D. Student in the City, Community, and Culture program at Tulane University. Her primary research interest is the role of black art and ritual as tools for transformation. She began studying the relationship between art institutions and community engagement after enrolling in a Museum Educator Practicum at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Al-Bilali went on to explore the role of arts and community with institutions such as No Longer Empty, the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute, The Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA), and the New Orleans African American Museum.

A Maddening Perception of a 15-year-old creatively interprets the experience of Deon Tae

2023, Archival pigment print.

For nearly two decades, I have documented social issues, conflict, and war with my camera, to tell stories of marginalized voices. Only recently have I considered myself an “artist,” as the primary goal of my work has been to raise awareness and improve the human condition. Photography has been the tool I have used to capture and convey emotion, pain, destruction, and beauty. With the advent of the rapidly developing technological marvel of Artificial Intelligence, lines begin to blur between reality and fiction. Our ability to perceive what is real is quickly shifting!

Just as our perceptions of reality can be altered by new information, so can the reality we create for others. During my time as Communications Director at the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana, I understood the

importance of creating narratives highlighting the humanity of children involved in the Juvenile Justice System. We often forget the mistakes of our childhood. We elevate ourselves above those who have made life-altering decisions. Understanding that the Juvenile Justice System was specifically designed to be rehabilitative is key to understanding that juvenile offenders are indeed children, even when they make adult-sized mistakes.

This work merges my passion for photography, technology, and Juvenile Justice Advocacy. It was created using digital photography as a base. I then fed prompts into Artificial Intelligence that were taken directly from an interview conducted with a young man who is determined to find himself on the right track. A Maddening Perception of a 15-year-old challenges the idea that children are disposable or irredeemable. Nothing can be farther from the truth. I hope that this piece resonates with the viewer to counter such perceptions.

Abdul Aziz (b. 1978, New Orleans, LA; based in New Orleans, LA) is an artist and media designer best known for his work as a photojournalist and documentary filmmaker. Early in his career, he served as a Communications Director for the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana (2006–2009) and a board member of LCCR

(2013–2017). Aziz has chronicled human conflict and urgent social issues in the Middle East and Africa to the far reaches of the Himalayas and US for over two decades. His most recent work focused on the rise of American white nationalism and the Black Lives Matter movement has been widely circulated by leading new agencies such as The New York Times, Der Spiegel, and NPR. In 2021, Aziz was recognized for capturing Louisiana’s history, culture, and peoples with the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ Documentary Photographer of the Year Award. He studied at Loyola University. www.photoaziz.com

Maroon, Mawòn (2 Sides II A Book) creatively interprets the experience of Jy’Harin

2023, Diptych, collage; graduation tassel fibers, cowrie shells, Dogon Tribe beads, and silkscreen on American Target Company shooting range target posters, colonial maple pine.

Depending on which of history’s sides you resonate with most, “maroon” as we know it today has French and/or Taino roots. According to one book, the word comes from the French “marron” which meant “feral” or “fugitive.” Another book would state that

maroon as we know it originates with the Spanish “cimarrón”, via the Taino people, meaning “untamed.” This layered multiplicity is a microcosm of the construct of Blackness—especially within a country such as the United States.

When I hear the word maroon, I think of enslaved people who escaped and liberated themselves to establish their own communities in countries such as Haiti, Brazil, Jamaica and the United States. This term and color, which has these varied meanings and relationships to “freedom,” instantly came to mind when I familiarized myself with Jy’Harin’s story. With that, I intended to create a piece influenced by some of his specific feelings and desires—his love of football, his desire to go to college and be an air traffic controller, his eight sisters. I also sought to illuminate the Black body, expression and image’s relationship to aspiration, captivity, control and capitalism.

In 2019, I found and purchased these original arrest reports featuring Black men from the 1930s–1960s and their eyes were, ironically and eerily, listed as maroon. The composition of these arrest reports juxtaposed with Black men from Morehouse College from the same time period, all screen printed onto a Black body silhouette produced by the American Target Company, intend to question the ways we might continue to be “targets” in our respective quests for liberation. The presence of elements such as the Dogon tribe beads, the cowrie shells and the loosely strung Black and Maroon fibers within the Colonial Maple Pinewood frame additionally reference the fortitude and eternality of African aesthetics along with the tensions that those of the diaspora must navigate within an imperialist based world.

Run creatively interprets the experience of LaZariah.

2022, Oil paint on canvas.

Adrienne Brown-David, Run, 2022.

Adrienne Brown-David, Run, 2022.

Much of my work focuses on Black freedom and challenging the narrative of what Black youth looks like to much of society. This piece represents breaking free of past constraints and sprinting toward a future of growth. Each step brings the possibility of something new, something fresh.