MAGAZINE Agritourism . Adventures in Life Sciences . Meet the New Dean

I AM CALS

Danny

Losito, CALS ‘14

Director of Sports Fields and Grounds Carolina Panthers | Charlotte FC

From the Super Bowl to Beyoncé concerts, CALS alum Danny Losito has built an impressive resume. And now, he’s got one of the rarest jobs in the country: one of only 30 director-level turfgrass managers in the NFL.

Continued on page 42

More online at go.ncsu.edu/DannyLosito

Stories from NC State’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

10

ADVENTURES IN LIFE SCIENCES

CALS life sciences alumni are finding—and even creating— their dream careers, from labs to zoos, in human health and data science, in rural and urban settings.

18 GARBAGE TO GARDENS

An innovative program in New Hanover County transforms cafeteria garbage once destined for landfills into compost for school gardens and outdoor spaces.

22 ONE OYSTER AT A TIME

North Carolina’s Oyster Trail supports coastal communities by serving up memorable experiences for foodies and tourists eager to sample these salty jewels from the sea.

28 AGRITOURISM—BENEFITING FARMERS AND COMMUNITIES

Unique, authentic, sustainable. Farm agritourism revenue tripled across the United States between 2002 and 2017. Learn why farmers, entrepreneurs and the next generation are utilizing creativity and ingenuity to draw visitors—and profits— via experience-led agriculture.

ONLINE EDITION go.ncsu.edu/CALSMagazine On the cover > NC State alumna Chinmayee Panda near the Plants for Human Health Institute in Kannapolis, North Carolina, where her enthusiasm for plant science took root. See story on page 14. Photo by Marc Hall. 4 CALS News 8 Roads to Carbon Removal 20 AGI Alum Spotlight 26 Undergrad Profile 38 4-H Spin Clubs 40 9,000 Students and Counting 42 I AM CALS 44 From the Archives CALS MAGAZINE FALL 2023

Learn more online go.ncsu.edu/DeanFox

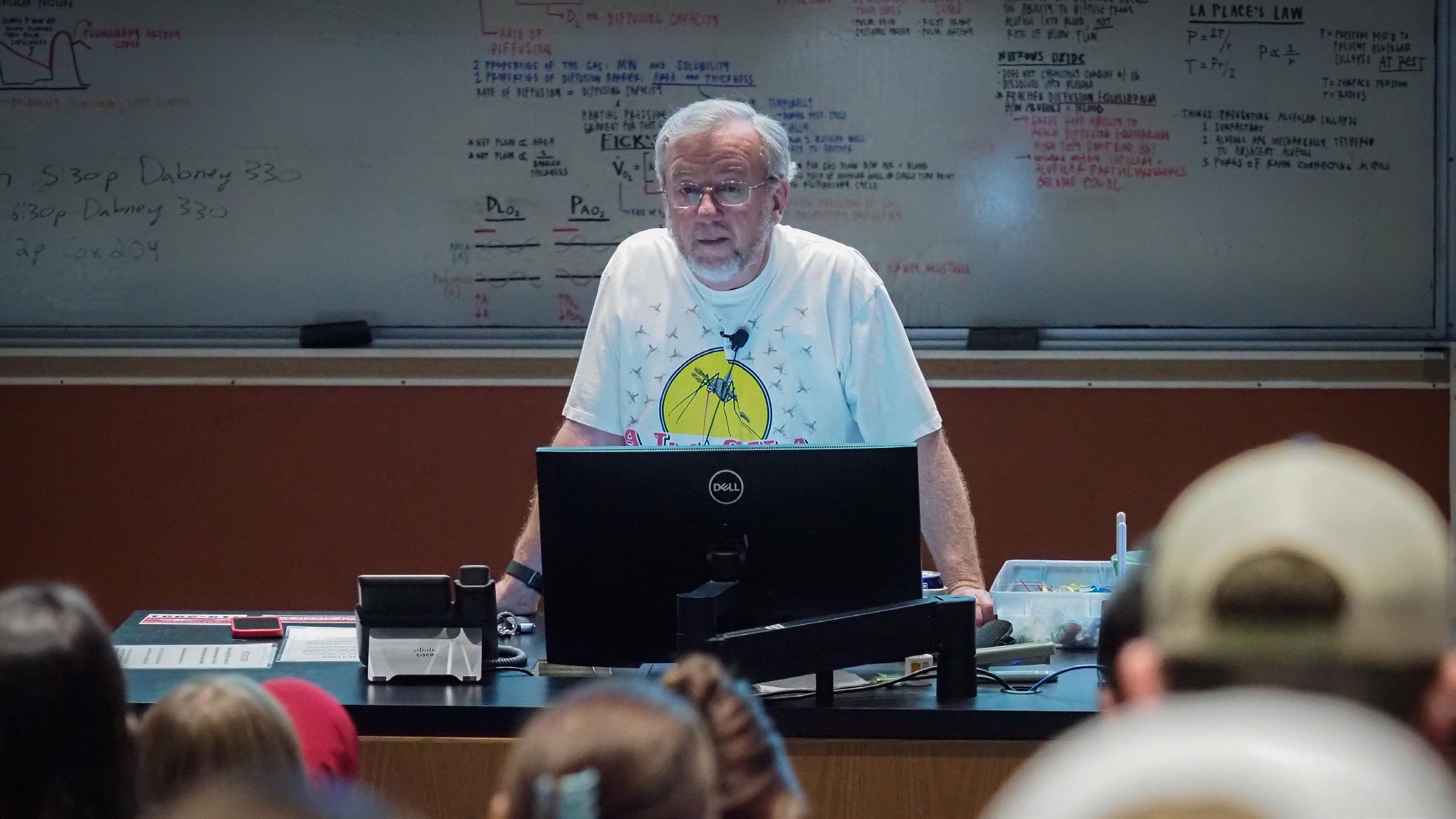

What are your initial goals as dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences?

One of the most important goals is making connections with people and understanding where there are opportunities for growth. A primary goal will be to continue the strong partnerships we have with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, NC Farm Bureau, and our industry and commodity groups within North Carolina. I am participating in a listening tour across the state where I can learn about all of the issues facing our agriculture and life sciences industries and how NC State can play an even greater role.

I’m going to find ways to provide resources, both internally and externally, to help our fantastic faculty, staff and students succeed and be more efficient and effective in their roles. I’m interested in engaging with students as much as possible and in putting together student advisory panels to help lead the college. I will also be visiting the incredible network of research stations we have within the state. I’m passionate about making sure that we help those research stations by improving facilities and bringing in new technology.

We need to continue to support the N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative and translate the great research at the Plant Sciences Building to our stakeholders, to really make a difference in the lives of citizens across North Carolina. We have an incredible opportunity to re-energize the vision for the Food Animal Initiative. How can we invest in and promote food-animal agriculture research, extension and teaching at NC State? Animal agriculture is such an important part of our agricultural industry.

What changes do you see on the horizon?

A digital revolution is happening right now, and it’s coming to agriculture and life sciences. We’ve already started to invest in artificial intelligence, data science and data analytics in CALS, but when you look at ChatGPT and open AI platforms, it’s going to

revolutionize what we’re doing and how we’re doing it, not only in research but also in extension and teaching.

You’ve worked jointly with the College of Engineering on the undergraduate programs in agricultural and biological engineering. Will you seek out new partnerships as dean?

One of the things that I’m excited about, based on that success, is building even stronger partnerships with not only the College of Engineering but all of our colleges at NC State. For example, how do we best interface with the College of Veterinary Medicine as part of the Food Animal Initiative? How do we better partner with the colleges of Sciences, Natural Resources, Textiles, Design, Humanities and Social Sciences, and Education, as examples, on important issues facing agriculture within North Carolina? When you consider the complexity of the food and agricultural system, the challenges are incredibly complex, and they’re going to require transdisciplinary expertise and efforts. We also need to recruit the very best students into CALS to help us solve these complex challenges.

What were your experiences with agriculture growing up?

I grew up on a beef cattle and wheat farm in a very small town named Godley, Texas. I graduated with a class of 35 students and was heavily involved in FFA, including traveling the state of Texas judging dairy cows, which provided so many opportunities to build leadership and public speaking skills. I’m a big supporter of youth educational activities like FFA and 4-H. I was a first-generation college student, and it was a shock, coming from a town of maybe 600 people, to walk into a chemistry class of 250 students at Texas A&M University. But the thing I could control, that was a part of my fabric from growing up on a farm, was hard work. It’s hard to outwork me, and I plan on using that work ethic as the dean of CALS.

cals.ncsu.edu 3

Get to know Garey Fox, the new dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Q&A

Meet Our New Department Leaders

After a nationwide search, alumnus Frank Siewerdt returned to the university as the new head of the Prestage Department of Poultry Science in May.

Originally from Brazil, he recently served in the United States as a national program leader in the Division of Animal Systems of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s Institute of Food Production and Sustainability.

Siewerdt earned his Ph.D. in genetics and statistics at NC State and plans to create an environment of excellence, mentorship and collaboration in the department.

He wants to invest in early-career faculty and students through mentoring and professional development. “It is always about the people,” he says. “We need to take ownership of preparing the next generation of leaders.”

New Zealand native and plant pathology researcher Carolyn Young was named the new head of the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology last year.

Young is an expert in developing a variety of tall fescue grasses that don’t compromise livestock health. She also studies pecan scab fungus to help farmers find ways to prevent it from ruining their crops.

Young, who has a strong interest in research projects that combine education and outreach, says she’s thrilled to lead the department.

“It is such a strong and innovative department that embraces the landgrant mission to benefit local, national and global agriculture and urban environments.”

Ecologist David Andow began his new role leading the Department of Applied Ecology in July.

Andow served as the Distinguished McKnight University Professor in the Department of Entomology at the University of Minnesota for 18 years.

Andow’s research has focused on insect population and community ecology, ecological risk assessment

for invasive species and genetically engineered organisms, insect resistance management and science policy.

“It’s a young, dynamic department, and I feel like I can help everybody there flourish,” Andow says, adding that he is eager to expand undergraduate programming. “I hope to help put students on a pathway to continued success into the future.”

4 CALS Magazine

Frank Siewerdt Prestage Department of Poultry Science

Carolyn Young Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology

David Andow Department of Applied Ecology

North Carolina FFA Honors Wilson

Beth Wilson, a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Human Sciences (AHS), received the North Carolina FFA Lifetime Achievement Award for her lasting impact on the agricultural industry. The organization’s highest accolade recognizes exceptional leadership, dedication to education and advocacy for agricultural development.

Wilson served in dual roles from 2013 to 2021 as director of North Carolina State University’s Agricultural Institute (AGI) and as assistant director of academic programs for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Her accomplishments include creating an internship program for AGI, starting the Soldier to Agriculture Program to recruit veterans, and securing over $1 million in grant and industry funding for improvements. She also developed curricula for high school agricultural science courses and for undergraduate and graduate classes in AHS.

Most recently, she has worked in CALS Career Services during phased retirement, recruiting industry representatives to post job openings and attend career fairs. A native North Carolinian, Wilson earned four degrees in horticulture and agricultural education at NC State. She taught high school for 13 years and received the National FFA Agriscience Teacher of the Year award. As the FFA central regional coordinator, she created three high school courses. After completing her doctorate, she was hired as an assistant professor to teach Methods of Teaching and supervise student teachers. While rising to full professor, she created curriculum and conducted science teacher workshops on biotechnology in agriculture, working across departments in CALS and the agricultural industry. In addition, she focused on teaching teachers to work with diverse learners.

Stage Honored for Preschool Nutrition Work

Virginia Stage, an assistant professor in the Department of Agricultural and Human Sciences, won the Nutrition Education Research Award from the Society of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

Stage, who’s known for designing programs that help preschoolers learn about science and healthy eating, began working in early childhood settings as a doctoral student in NC State’s Department of Food, Bioprocessing and Nutrition Sciences. Prior to joining NC State in 2022, Stage was a faculty member at East Carolina University (ECU) for over 10 years.

As a registered dietitian, Stage believes that teachers and families need to work together to improve children’s health. She leads a diverse team of multidisciplinary researchers from ECU, NC State, North Carolina A&T and UNC Greensboro developing strategies to train Head Start teachers. She has partnered with NC State’s Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program to create healthy eating and physical activity programming for Head Start teachers and families. A National Institutes of Health Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences funded a $1.3 million, five-year project known as More PEAS, Please! (short for Preschool Education in Applied Sciences). A revised program is underway in Wake, Sampson, Chatham and Caswell counties.

cals.ncsu.edu 5 CALSNEWS

Editor

D’Lyn Ford

Art Director

Patty Anthony Mercer

Staff and Contributing Writers

Rachel Damiani, D’Lyn Ford, Simon Gonzalez, Lea Hart, Sam Jones, Chelsea Kellner, Krystal Lynch, Emma Macek, Alice Manning Touchette

Photography

Keeshan Ganatra, Marc Hall, Becky Kirkland

Videography

Keeshan Ganatra, Chris Liotta

Digital Design

Leighann Vinesett

Creative Team

Janine Brumfield, Kionna Coleman, Caro Metzler

Copy Editors

Gregor Meyer, Dee Shore

Dean, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Garey Fox

Senior Associate Dean for Administration

Harry Daniels

Associate Dean and Director, NC State Extension

Richard Bonanno

Associate Dean and Director, N.C. Agricultural Research Service

Steve Lommel

Interim Associate Dean and Director, Academic Programs

Kimberly Allen

Assistant Dean and Director, CALS Advancement

Sonia Murphy

Chief Communications Officer

Megan Lybrand

Visit Us Online > cals.ncsu.edu

NC State University promotes equal opportunity and prohibits discrimination and harassment based upon one’s age, color, disability, gender identity, genetic information, national origin, race, religion, sex (including pregnancy), sexual orientation and veteran status.

Send correspondence and requests for change of address to CALS Magazine Editor, Campus Box 7603, NC State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 -7603.

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

Jabeen Ahmad | Fall 2020 Issue

Jabeen Ahmad, a Ph.D. candidate in plant biology who was featured in the fall 2020 issue, is continuing her work to promote food security in North Carolina. Ahmad’s research is part of a larger global initiative with North Carolina State University and several institutions in Denmark. She is working on the Interact Project, a Novo Nordisk Foundation-funded research effort that explores microbiomes in wheat roots.

In May, Ahmad met Christina Markus Lassen, Danish ambassador to the United States, who visited the Plant Sciences Building, headquarters for the N.C. Plant Sciences Initiative. Ahmad gave the ambassador a lab tour and provided detailed insight into the research she hopes to apply to realworld scenarios that North Carolina farmers face.

Ahmad received a 2023 Fulbright Scholarship that will allow her to spend her final doctoral year with Mette Haubjerg Nicolaisen, associate professor of microbial ecology and biotechnology at the University of Copenhagen.

“There’s a strong initiative in Denmark for promoting more sustainable agriculture,” Ahmad says.

She will continue her research overseas to understand the wheat root microbiome to improve plant growth, development and resilience.

CALS Magazine Fall 2023

9,000 copies of this public document were printed at a cost of $1.29 per copy. Printed on recycled paper.

From Lawn to Learning Landscape

A conventional lawn and courtyard tucked between two engineering buildings isn’t an obvious place to learn about sustainability and permaculture. But that’s the plotline for the space between North Carolina State University’s D.S. Weaver Laboratories and the Weaver Administration Building.

By spring 2024, a nondescript patch of grass will become a vegetable garden, pollinator garden and serenity garden, accessible on paths made of pavers. A tiny farm of experimental row and beneficial cover crops will highlight sustainable farming.

Jasmine Gibson, a master’s student in the Department of Horticultural Science, is leading the project to engage Biological and Agricultural Engineering (BAE) students and promote urban agriculture. With BAE’s Graduate Student Association (GSA), Gibson is raising funds and securing donations. Construction is expected to wrap up by Earth Month next April.

“I want the garden’s raised beds, information signage and pathways to encourage students to apply their engineering curriculum to solve local food security and sustainability disparities,” she says.

Before changing her focus to horticultural science, Gibson was a BAE student. Her involvement with the garden began with her board membership in BAE’s GSA and horticultural science Professor Anne Spafford’s permaculture plant design course.

Gibson and Spafford, who’s now her adviser, created a conceptual design for the 1,890-square-foot plot that incorporates donated compost, pavers and landscaping grasses from Hoffman Nursery in Rougemont, North Carolina. Four commercial nurseries have also donated plants, and three faculty members have donated seeds. Gibson and Neil Bain, BAE research shop supervisor, are coordinating construction with the university’s landscape management team.

Gibson says sustainable farming isn’t new. “We are trying to replicate what Indigenous people have done for us and give credit where it’s due.”

By seeking Black BAE student involvement, Gibson also wants to remove the stigma associated with farming within the Black community. “Farming was our longest career in Africa. It didn’t start with slavery, and we shouldn’t be ashamed of returning to it.”

cals.ncsu.edu 7 CALSNEWS

KRYSTAL LYNCH

“I want the garden’s raised beds, information signage and pathways to encourage students to apply their engineering curriculum to solve local food security and sustainability disparities.”

Roads to Carbon Removal

By Sam Jones

Global efforts to reduce carbon emissions in the face of a warming world are making significant gains, but scientists don’t think the gains will be fast enough to avoid a 2-degree Celsius (3.6-degree F) global temperature increase. Finding new ways to actively remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere could make a critical difference.

“Climate scientists agree that we have to start removing carbon from the atmosphere to the tune of a few billion tons per year by the middle of the century,” says Joe Sagues, assistant professor in the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering.

Currently, only a few million tons of carbon dioxide are actively removed from the atmosphere every year. Researchers at North Carolina State University are investigating ways to increase that number.

BIOPRODUCTS

BIOELECTRICITY SWITCHGRASS

POLYETHYLENE PLASTIC CORN STOVER

FOREST RESIDUE CONSTRUCTION MATERIALS

Bioprocessing, one of the technologies that can be used to remove carbon, is the subject of Sagues’ research. He and his team conducted a detailed life-cycle assessment of four bioproducts already on the market: bioelectricity from switchgrass, polyethylene (plastic) from corn remnants, and biochar and construction materials from forest residue. The ultimate goal is to find economically feasible and efficient solutions that go beyond carbon-neutral to carbon-negative.

“We wanted to understand what the carbon footprint over the full life cycle of the bioproduct is, how carbon-negative the bioproduct could be and how stable the carbon is,” Sagues says. “We were able to show that all four bioproducts can remove a pretty substantial amount of carbon from the atmosphere, and that they could be truly carbon negative over 100, 1,000 and even 10,000 years.”

8 CALS Magazine

Sagues represents NC State in a multi-institutional grant project funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. The Roads to Removal project will carry out a granular geospatial assessment of the United States to identify the cheapest carbon removal options at the county level.

The project consists of four teams: forestry, soils, direct air capture, and biomass, carbon removal and storage, or BiCRS, co-led by Sagues. All four teams are using pre-existing databases that show biomass availability. Sagues’ team is looking at uses for waste materials like agricultural residue, forestry residue and municipal organic waste, as well as sustainable crops like switchgrass.

“Roads to Removal is novel because while biomass availability isn’t necessarily new, no one’s ever built a model that could look at, say, seven different industrial bioprocessing technologies to make 15 different bioproducts, and then recommend the precise technologies and bioproducts that individual counties with specific biomass can produce for the lowest cost,” Sagues says.

The BiCRS team alone has found that industrial bioprocessing could remove approximately 500 million tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year for less than $100 per ton.

From carbon capture plants at pulp and paper mills throughout the Southeast to bioethanol production facilities in the Midwest, the carbon-negative bioeconomy is ramping up across the country, in large part due to new and existing federal tax credits. Other funding sources are stepping up to fill in the gaps.

In 2021, worldwide funding for carbon capture and storage rose to $224 million, compared with just $13 million in 2015. Sagues’ own research has led to significant commercialization efforts in the chemical and manufacturing sectors, along with opportunities for carbon-negative consultants and even a startup of his own. The carbon-negative bioeconomy points the way for profitability and sustainability to converge on the path to a cooler world.

cals.ncsu.edu 9

“Climate scientists agree that we have to start removing carbon from the atmosphere to the tune of a few billion tons per year by the middle of the century.”

Joe Sagues

Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering

FUNDING FOR CARBON CAPTURE AND STORAGE 2015 $13 M $224 M 2022

ADVENTURES

IN LIFE SCIENCES

By D’Lyn Ford

Life scientists are some of the most inventive people around. They’ve mastered specialized tools and technologies, and they’ve developed professional skills like teamwork, leadership and communication as they seek—and even create—their dream jobs.

Barbara Durrant , for example, built her wild and wonderful career with the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance using degrees in animal science, physiology and reproductive physiology from North Carolina State University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS).

CALS researchers take a life sciences approach to tackling the grand challenges of food security and sustainability, working hand in hand with agriculture.

“We need to be responsible in understanding what we’re doing in the plant, with the animal, in the environment,” says Amy Grunden, assistant director of the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service (NCARS). “You gain that understanding through a life sciences perspective.”

A Competitive Advantage

Proximity to Research Triangle Park, the largest U.S. research park, gives CALS life sciences students opportunities to study, network, intern and collaborate with global companies, starting as undergraduates.

“I herald it as much as I can, because it gives us a competitive advantage,” says Steve Lommel, CALS associate dean and NCARS director. “A lot of our graduates end up in those companies.”

Graduates also pursue academic research, become entrepreneurs, work in non-governmental organizations, and go on to medical school and health careers.

Many more life sciences graduates are needed. “Nationwide, there’s a deficit of 40,000 master’s and Ph.D. graduates a year in the plant sciences,” says Lommel, a board member with the North Carolina Biotechnology Center (NCBiotech).

Demand is strong for NC State alumni like Kristen Eads, whose Master of Microbial Biotechnology (MMB) degree equipped her to lead pharmaceutical programs for patients with rare diseases. The MMB’s scientific and business coursework opens doors to marketing and management. Ninety-three percent of MMB graduates are employed within three months, earning an average salary of $91,949 within six months.

Beyond RTP, Paul Ulanch, a senior director with NCBiotech, sees advantages from state investment in the North Carolina Research Campus in Kannapolis. “That campus is starting to see interesting collaborations, with a lot being led by NC State. Great examples are the Food Innovation Lab and Plants for Human Health Institute.”

Alumna Chinmayee Panda, who worked at the institute as she earned a Ph.D. in microbiology and genetics, landed a research job in Kannapolis with a nutritional supplement company.

Life sciences hubs are growing statewide, from Asheville to Wilmington. State economic development officials work with community development experts from N.C. Cooperative Extension in all 100 counties and with the Eastern Band of Cherokee.

Ever-Evolving Life Sciences

With constant change, including a “tsunami of biotechnology,” as Lommel puts it, the life sciences sector is evolving rapidly. To help meet the growing demand for big data analytics and regulatory knowledge, CALS created new certificate programs.

Alumna Shelly Hunt was among the first to earn an Agriculture Data Science Certificate, along with a master’s in biological engineering. Immediately after graduation, she landed a job with the agriculture division of analytics giant SAS.

For Hunt, it adds up to a promising start in a field where she can choose her own adventure.

Read on to learn about the career paths of Durrant, Panda, Eads and Hunt. >

10 CALS Magazine

LIFE SCIENCES PAYS

$112,000 Average salary for a life sciences job in N.C.

That’s nearly twice the pay earned by other private-sector workers statewide.

2X the pay

A RECORD YEAR

2022 was a record year for investment in life sciences in North Carolina.

33 projects funded

2,700 jobs expected

LIFE SCIENCES JOBS IN N.C. ARE GROWING AT A FASTER RATE THAN JOBS IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR OVERALL

totaling $2.1B

Employment growth in N.C. (since 2018):

13% growth

ifeSciences Companies

Source: Fierce Biotech, 2023

Considering a career in life sciences?

Source: North Carolina Biotechnology Center, 2023

TOP 10 LIFE SCIENCE JOBS FOR THE NEXT DECADE

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational

3% growth Private SectorOvera

Source: 2022 TEConomy Report

4 th

N.C.’s Research Triangle hub ranks nationally for biotechnology activity.

NORTH CAROLINA’S LIFE SCIENCES SECTOR

75,000 EMPLOYEES

810 Life sciences companies

2,500 Companies that support or are related to life sciences

Source: North Carolina Biotechnology Center, 2023

cals.ncsu.edu 11

L I FESCIENCESCAREER S

PROFILESIN

L

l l

Outlook Handbook

1. Clinical Laboratory Technologists 2. Medical Scientists 3. Biological Engineers 4. Biochemists and Biophysicists 5. Chemical Technicians 6. Epidemiologists 7. Microbiologists 8. Bioengineers and Biomedical Engineers 9. Genetic Counselors 10. Zoologists and Wildlife Biologists

BIRDS, BEES AND RHINO BABIES

By Emma Macek

From rattlesnakes to rhinos, Barbara Durrant, a three-time alumna from North Carolina State University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, has worked with hundreds of different wildlife species throughout her nearly 45-year career at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

Her focus is the “birds and the bees” of zoo animals. As the Henshaw Endowed Director of Reproductive Sciences, she studies reproductive biology, endocrinology and behavior, and develops methods to encourage species reproduction with an important goal: conservation.

“What could be more interesting than reproduction? And the result is wonderfully cute babies of different species,” Durrant says.

A Wild Start

Durrant’s interest in animals began while growing up near Syracuse, New York. She enjoyed spending time outside observing the native wildlife, sometimes returning home with injured birds or mice.

12 CALS Magazine

“My parents were both in medicine, so when I brought home injured animals, they would help to rehabilitate and release them,” she explains. Her parents urged her to become a vet, but she had her eyes set on exotic animals.

“Everywhere my family traveled, I always made them go to the local zoo,” Durrant says.

During high school, Durrant’s family moved to North Carolina, and she decided to study animal science at NC State. She was one of only two women in the animal science program at the time.

Durrant remembers being laughed at by her male classmates—who grew up on farms—because she didn’t have the same skills they did, but she didn’t let that stop her. After earning her bachelor’s degree, she earned a master’s in physiology and a doctorate in reproductive physiology, studying embryo metabolism and reproduction genetics, respectively. She received an Outstanding Alumni Award in 2022.

Saving Species

While earning her master’s degree, Durrant learned that the San Diego Zoo was starting a research program, and she reached out in hopes of landing a position there.

“I loved the idea of working with zoo animals, and it was the only zoo that had a research department,” Durrant says.

After earning her doctorate, she was hired as a postdoctoral researcher and helped start the now-famous Frozen Zoo, the largest bank of cryopreserved living exotic animal cells in the world.

“There wasn’t anyone doing reproductive physiology research at the zoo, so I stepped into a job that wasn’t there and created one,” Durrant says. “It really was a dream job, and it still is.”

Durrant leads a team of 16, and her lab manager, Nicole Ravida ’00, is also an NC State animal science graduate. One of the team’s main projects is helping the northern white rhino avoid extinction. Listed as “critically endangered,” there are only two northern white rhinos left worldwide, and they’re females who can’t reproduce.

The Frozen Zoo has cells from northern white rhinos, and researchers are hopeful they can revive the species through careful reproductive planning with their close relative, the southern white rhino, which is listed as “near threatened.” The zoo has six southern white rhinos that are specially trained for reproductive monitoring, such as ultrasound and hormone analysis. So far, Durrant’s team has welcomed two southern white rhino calves—Edward and Future—through artificial insemination; one from frozen semen, which had rarely been successful in rhinos, and one from chilled semen, which had never been successful in any rhino species.

Over the years, Durrant has also worked on the reproduction of giant pandas, antelope, koalas and cheetahs. With all of her wild success, she hasn’t forgotten about her time at NC State.

“All of my current work has a basis in the cattle, pigs and sheep I studied at NC State,” Durrant says. “There are variations, of course, but it’s the same basic studies that are stretched and manipulated for each species.” >

cals.ncsu.edu 13

Opposite: Barbara Durrant gives a southern white rhino an ultrasound. Above: Edward, a southern white rhino born in 2019 through artificial insemination, and his mother, Victoria. Photos courtesy of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

PROFILESIN L I FESCIENCESCAREER S

“There wasn’t anybody doing reproductive physiology, so I stepped into a job that wasn’t there and created one. It really was a dream job, and it still is.”

UNLEASHING PLANT POWER

“I faced my fears head on and fate intervened.”

14 CALS Magazine

By Rachel Damiani

Chinmayee Panda was in her early 20s, living in Davidson, North Carolina, about 8,000 miles from her home in India, and eager to pursue a graduate degree.

Unsure where to begin, she started knocking on doors— visiting the library and professors’ offices to learn more about research opportunities in North Carolina. Eventually, her explorations led her to North Carolina State University’s Plants for Human Health Institute (PHHI) in Kannapolis, 25 miles away.

“I visited the campus, and I happened to speak with a couple of people who were probably taking a stroll on their lunch break,” Panda says. “I stopped them and asked about the institute and their work.”

These strangers told her about investigating plants to help people live healthier lives.

“I was sold,” Panda says. “It felt like a hot spot of intellectual curiosity and stimulation.”

This small talk led to big life changes, despite some trepidation on Panda’s part. “I faced my fears head on, and fate intervened.”

After her serendipitous encounter, Panda interned with PHHI, earned her doctorate in NC State University’s Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, and landed a coveted role as a clinical research scientist with the Kannapolis location of Standard Process Inc., a Wisconsin-based company that produces plant-based nutritional supplements for people and pets.

Panda’s fascination with plants has propelled her career. She’s especially intrigued by phytonutrients, compounds that plants produce to protect themselves from threats. For example, some berries create polyphenols that can provide antioxidant benefits for people.

“Plants are the most intelligent species to me because they have evolved to really deal with stressors in their own way by forming phytonutrients, which are really helpful to them,” she says. “We are actually harnessing that power now to be able to help human health.”

In her current role, Panda investigates these phytonutrients with the goal of bringing botanically based nutritional supplements to market. She’s a scientific jack-of-all-trades who

designs clinical trials, publishes peer-reviewed papers and manages teams.

While Panda says she’s found a fulfilling career, her path has surprised her.

“When I was in India as a child, I didn’t know this field existed at the intersection of clinical research, nutrition, genetics and genomics,” she says. “But I had an unwavering passion for science and its transformative potential in improving lives that has always stayed with me.”

She says the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences gave her a strong foundation to make her career passion a reality. Panda approached each opportunity with grit, starting with her PHHI internship.

“If I look back at myself, I think the only driving force that I had at that point was my scientific curiosity and passion. ‘I want to do something. Just give me a chance. I’m going to try hard,’” she says.

It wasn’t long until Richard Blanton, director of graduate programs for the Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, encouraged Panda to apply to the Ph.D. program and connected her with a mentor.

Once accepted, she began studying the nitty gritty of plants as the first doctoral student in the lab of Associate Professor Xu “Sirius” Li. As PHHI’s plant metabolic pathway engineer, Li applies his biochemistry expertise to understanding the inner workings of plants.

“He really honed my critical thinking and cognitive skills,” Panda says. “He constantly challenged me to excel.”

Panda says pursuing her doctorate was demanding. But just as a plant can build phytonutrients by taking what it needs from the soil, Panda cultivated her resilience by tapping into the support of her dissertation committee members.

Six years after graduating, Panda no longer knocks on doors. Instead, she opens doors for the public as a science communicator for consumers, policymakers and students who may follow her path.

“I like keeping the content really clear, concise, scientifically sound, yet captivating for audiences,” she says. “Witnessing the spark of curiosity in their eyes is really gratifying.” >

cals.ncsu.edu 15

PROFILESIN L I FESCIENCESCAREER S

A DOSE OF HOPE

By Lea Hart

Kristen Eads supports patients who are prescribed medicines to treat rare diseases, ensuring that pharmaceutical science reaches people who can benefit.

She’s uniquely qualified to serve as a rare patient experience strategy and design lead at UCB, a global biopharmaceutical company, thanks to the Master of Microbial Biology (MMB) degree she earned in 2006 from North Carolina State University.

As a professional science master’s degree, the MMB program blends science and business education with practical training in the biotech industry. Eads took electives within the Poole College of Management, including a pharmaceutical supply chain course. She still remembers a guest speaker’s talk about the

balance between the affordability of pharmaceuticals and innovation for new medications.

“The real benefit to the MMB program is the fact that it puts students squarely into industry to work on real problems and real challenges to create real solutions,” she says.

Patients can have difficulty getting access to and coverage for rare disease medicines because they are specialty products, Eads says.

Patient support programs implemented by manufacturers help patients obtain, afford and remain compliant with their medications. Patients often don’t know these programs exist, so step one for Eads is building awareness.

Her MMB degree taught her to distill information and communicate to all

stakeholders while working within a specialized business environment.

“Because it’s pharmaceuticals, it’s highly regulated for all the right reasons,” she says. “There’s a degree of scientific marketing associated with it, but I also work with lay people. I have to be able to interpret the data in a way that can be consumed by someone with a limited science background.”

Eads brought her industry perspective back to NC State, serving on the MMB’s Industry Advisory Board for 11 years before recently stepping away from the role.

“I have energy behind trying to help students make that transition into the working world and providing them perspective on how to go about doing it,” she says.

16 CALS Magazine

“The real benefit to the program is the fact that it puts students squarely into industry to work on real problems and real challenges to create real solutions.”

DRIVEN BY DATA

By Lea Hart

A background in math and engineering plus an interest in agriculture started adding up for Shelly Hunt in her junior year at NC State. That’s when she decided to explore data analytics.

While earning her master’s degree in biological engineering, Hunt became one of the first students at NC State to complete an Agriculture Data Science Certificate, which bridges data science and agricultural fields of study.

Hunt’s experiences with data science led her to a job at SAS, a Cary-based company with NC State roots that develops and markets analytics software. As an agriculture and consumer goods specialist, she supports the agriculture sales division as an analyst, building industry partnerships in agricultural equipment, retail agriculture, animal science and other areas.

At NC State, she was a member of the interdisciplinary research team on the Sweet-APPS project, working to reduce agricultural waste and maximize yield for North Carolina’s sweetpotato producers. SAS was an industry partner, and Hunt networked her way into an internship and then a full-time position.

“Everything I learned earning the certificate is very applicable to my current role,” she says. “I see myself as sort of the expert in machine learning on my team. It sets me apart within my group—I’m the person to go to when we talk about all things machine learning, Internet of Things and so on.”

Hunt currently serves as SAS’ liaison to NC State and the North Carolina Plant Sciences Initiative, exploring ways to optimize their partnership.

Data science is the future of agriculture, according to Hunt. “I can see how much benefit it brings industry from profitability and risk reduction standpoints. I want to help make data science approachable and applicable to growers.”

cals.ncsu.edu 17

PROFILESIN L I FESCIENCESCAREER S

“Data science is the future of agriculture.”

By Simon Gonzalez

Lunchtime is learning time at Winter Park Elementary and D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy in Wilmington.

No, the kids aren’t burdened with extra reading, writing or arithmetic during the daily break. They get to enjoy their meals and time with friends. But afterward they employ important lessons in environmental stewardship.

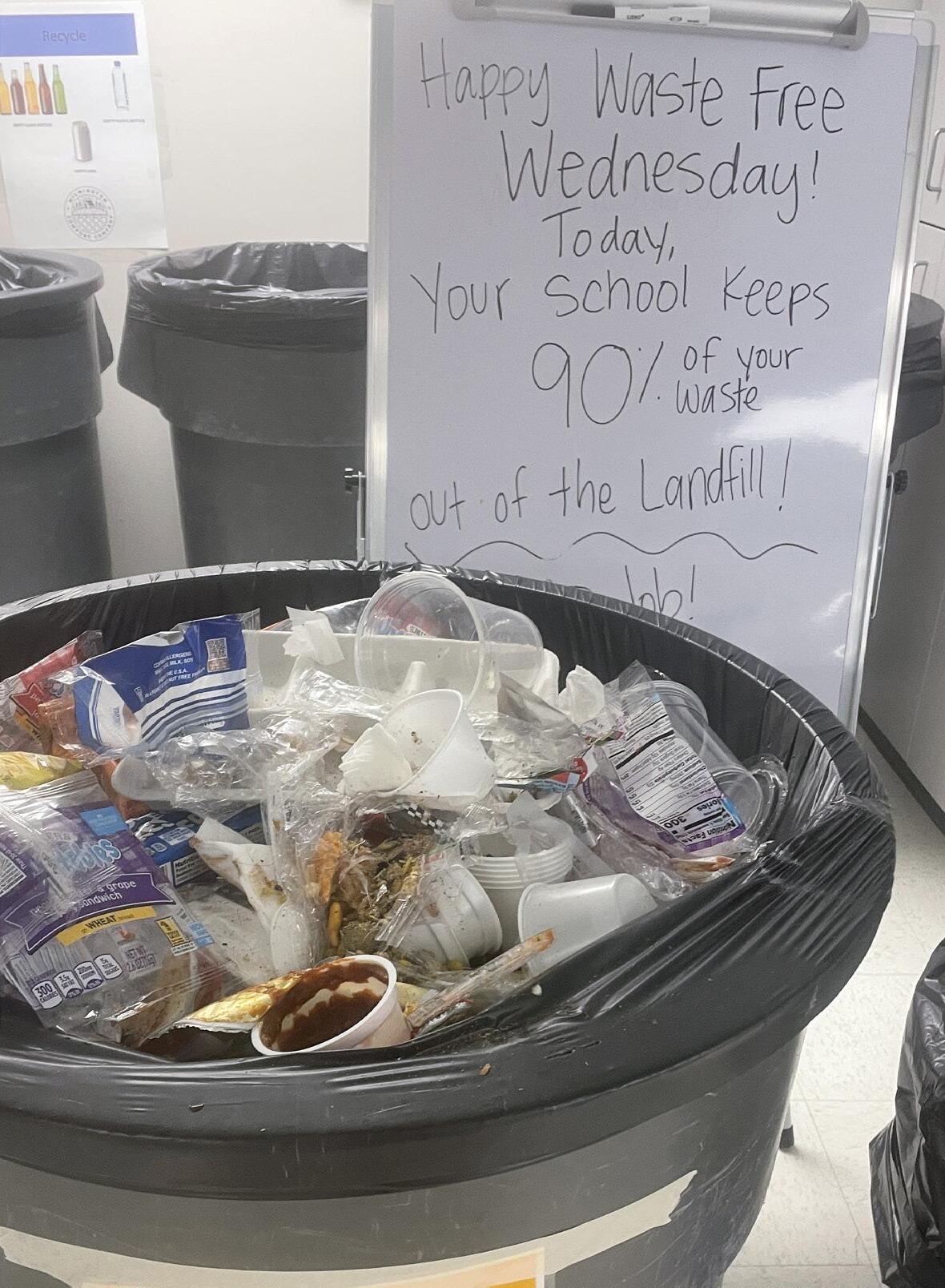

Rather than dumping all the detritus from the meal into a big trash can, the students separate it. Recyclables go into bins. Liquids are poured off. Organic food waste goes into a separate container that’s shipped to the county composting unit.

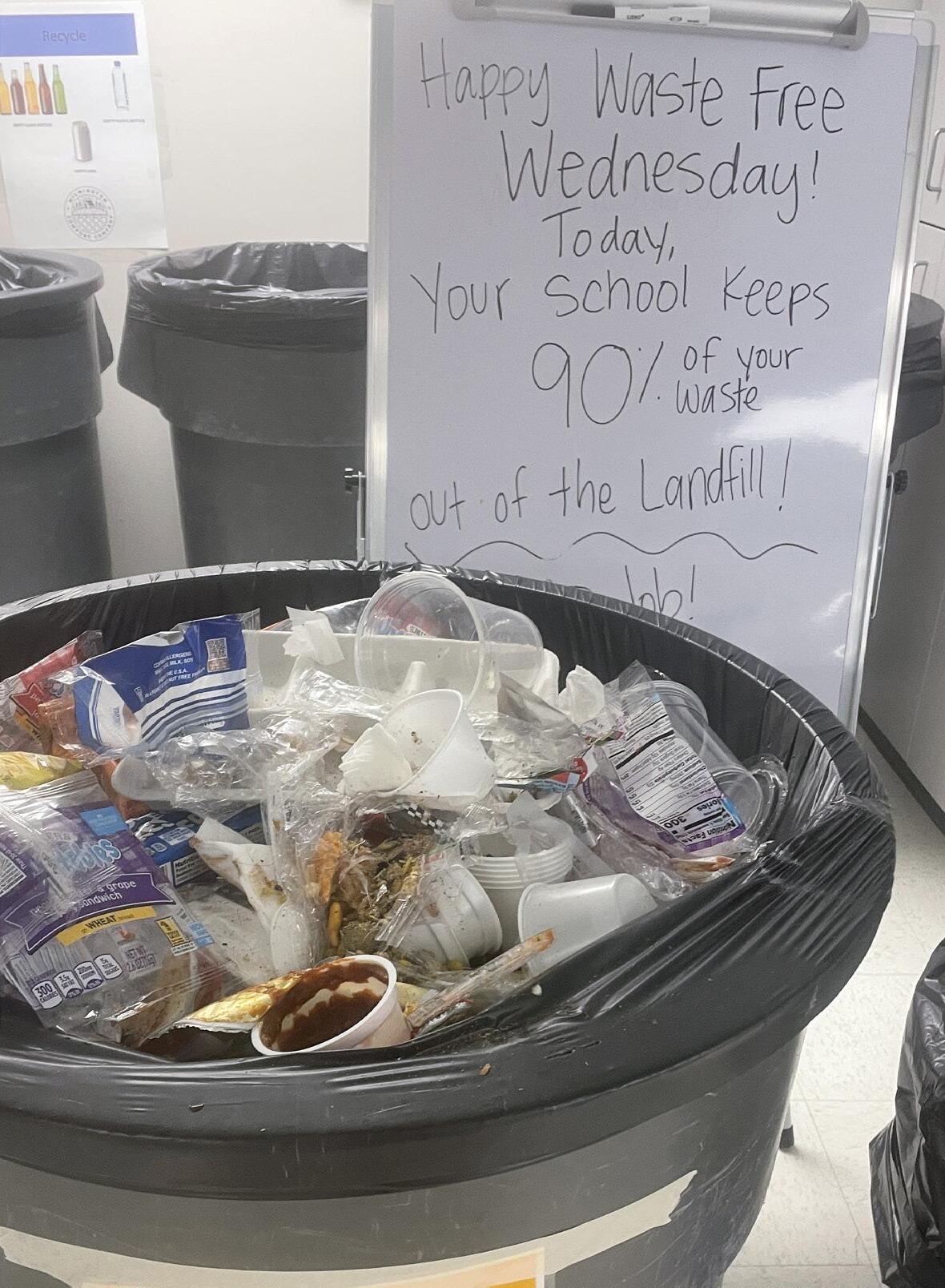

“The young kids really jump into it. There’s a clear energy and excitement about having the opportunity to be a waste ambassador,” says Matt Collogan, N.C. Cooperative Extension consumer horticulture agent in New Hanover County. “Before the program was implemented, 10 trash bags would be going to the dumpster after every cafeteria session. Now we’re looking at one bag.”

The Extension center in New Hanover County began the Garbage to Gardens program in 2019 as part of a multifaceted effort to reduce waste going to landfills.

“New Hanover County has 28 years left at current fill rates before it is filled to the brim,” Collogan says. “When Hurricane Florence happened (in 2018), we lost about 13 years of lifespan off the landfill in one blow. So we are two big storms away from having no landfill.”

State law prohibits new landfill permitting in coastal counties, which will face new costs and logistical challenges to dispose of their waste when landfills are saturated.

Extension’s response was to increase sustainability efforts, both at the county center at the New Hanover County Arboretum—which won the 2023 Sustainability Award from the American Public Gardens Association— and in the community, through recycling and composting.

“Any time we can divert landfill waste to some other source, we are saving our taxpayers dollars. That’s why composting is huge,” says County Extension Director Lloyd Singleton. “We did a waste characterization study about four years ago. We found that 40% of what was going to our landfill could be composted, and about 20% of it could be recycled. By really emphasizing that, we’ve diverted a lot of waste from the landfill.”

The school pilot program began in 2019 at Winter Park Elementary.

“The Garbage to Gardens name was coined by the students,” Collogan says, noting that the food that the students divert comes back to the schools as compost to be used in outdoor learning spaces and school gardens.

D.C. Virgo was added in 2021, when part-time coordinator Kat Polk came on board. A $180,000 U.S. Department of Agriculture grant will fund a full-time coordinator and expansion into 18 schools in the county.

NC State Extension is also well positioned to grow Garbage to Gardens beyond New Hanover County.

“The state is looking at this very seriously, that we should have a systemic food waste diversion program in our schools,” Collogan says. “We’ve produced a gettingstarted guide that any school can use, starting with low cost and little effort, all the way up to the Cadillac version of paying someone to haul off the diverted food waste.”

18 CALS Magazine

“Before the program was implemented, 10 trash bags would be going to the dumpster every cafeteria session. Now we’re looking at one bag.”

cals.ncsu.edu 19

“Anytime we can divert landfill waste to some other source we are saving our taxpayers dollars. That’s why composting is huge.”

I was a very nontraditional student at the Ag Institute. I actually graduated from the University of Georgia in 2013, so I did this backwards, but there’s a story behind it.

After earning a bachelor’s in international affairs, my goal was to work for UNICEF, to help starving children. I spent time in the Dominican Republic at an orphanage where the children didn’t have shoes and other things that we take for granted, which was a big eye-opener. But I felt that even though there’s extreme poverty over there, we have just as much here in the States, and I should help in my home country.

Amanda Hadden, a 2023 graduate of the Agricultural Institute at NC State, tells the story of her educational journey in her own words.

Amanda Hadden, a 2023 graduate of the Agricultural Institute at NC State, tells the story of her educational journey in her own words.

How do you combat poverty? I thought it started with education. After going through alternative certification, I taught at high-poverty schools in two different settings, urban and then rural. I got to see firsthand what an effect poverty has. A child could be misbehaving because they didn’t get dinner the night before. For some students, the only guaranteed food they have is the breakfast, lunch and snack provided at school. It broke my heart.

I made my classroom a safe place, built relationships with parents and felt I was able to make an impact. But my mom would visit, and she could tell that I literally was just coming home, taking a shower, eating, getting up and doing it all over. As much as I loved it, that wasn’t sustainable.

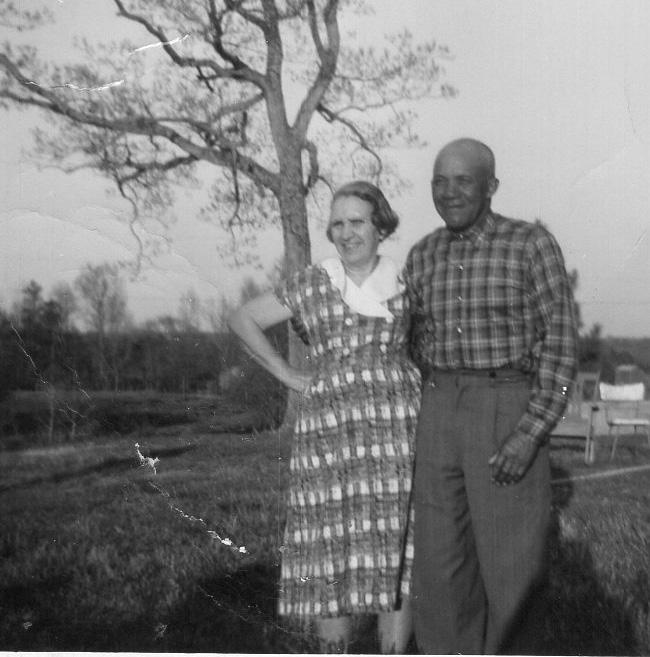

In my childhood I showed horses, and my happy place was at the barn with the animals. But I had totally forgotten about my family’s roots. My great-grandfather was a farmer. He raised hogs and grew tobacco. We still own that land in Franklin County, which has been passed down in my family since the 1890s. My dad’s plan was to retire on the land, but that changed.

I approached my dad and said, “I want to restore the land.” And he said, ”OK, I support you, but you don’t know what you’re doing.” I learned about the Ag Institute and said, “I can know what I’m doing. It’s a degree from NC State. It’s reputable.” What really drew me to it were the hands-on opportunities, because at every job that I’d had, I was inside all day.

At the Ag Institute, I could put my life on pause for two years and then have a career I enjoy. Going back to school, I was the one footing the bill. For the first year and a half, I worked 12-hour shifts on Saturdays and Sundays as a nursing home receptionist.

When my heart was heavy, I’d go out to the land or my grandparents’ or great-grandparents’ grave site. I just asked them to guide me and protect me, because it’s hard. I was never treated any differently at NC State, but walking into a meeting and being the only Black person—that’s intimidating. It made me secondguess myself.

Initially I felt alone, but the more I got involved and the more I asked for help, I realized that I’m not alone. This is a community that wants to see their students excel. My adviser, Dr. Lynn Worley-Davis, has been truly instrumental. She brought in people from the poultry industry who talked about all the career opportunities, this whole world that I never knew about.

I found that I love working with chickens. That led to internships, joining the Poultry Science Club and the Young Farmers and Ranchers Program through Farm Bureau, and taking on an Ag Institute ambassador role. As the president of Delta Tau Alpha honor society, I’ve been able to bring in Ag Institute graduates to tell us what they did with their degrees.

I started working at the Chicken Education Unit at the Lake Wheeler Road Field Lab to learn more about birds and get hands-on experience. I did an internship last spring with Braswell Family Farms, and that was fantastic, because I had no agriculture experience. The fact that they gave me a chance, I’ll be forever grateful for. I also interned with Mountaire Farms to see all aspects of the poultry industry. That led to a job as a flock advisor with Perdue Farms.

It’s funny how life works. When I went to Georgia, I wanted to combat hunger and help starving children. Years later, I’m going into an industry that is helping feed the world. Full circle moment. Different approach, but the same goal.

Opposite: Amanda Hadden graduated in May as the Ag Institute’s only valedictorian, earning a 4.0 GPA. Top circle: Hadden at the Chicken Education Unit. Lower circle: Hadden’s great-grandparents, John and Amanda Alston, in 1963.

One

yster At A Time

By Sam Jones

From the salty breeze of the Outer Banks to the winding undulations of the Blue Ridge Mountains, a new food trail is introducing people to a rather misunderstood creature: the eastern oyster.

In the spring of 2020, North Carolina Cooperative Extension specialist Jane Harrison launched the NC Oyster Trail, a grassroots network of oyster growers and fishers; seafood markets, restaurants and festivals; environmental education centers; and conservation organizations. The trail has grown to encompass 80 sites offering memorable experiences for foodies and farm fanatics of all kinds.

Harrison wears a few hats—she is an affiliate faculty member in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics and a graduate faculty member in the College of Natural Resources. Her primary position is the coastal

economics Extension specialist for NC Sea Grant, where she repeatedly heard from shellfish growers about the need for more consumer awareness of their tasty bivalves.

“Some of my agribusiness students have tried their hand at growing oysters,” Harrison says. “Oyster farmers have stepped up to the plate to grow shellfish with innovative marine aquaculture technologies, providing a truly sustainable protein.”

Despite their environmental benefits, Harrison says oysters are not the No.1 seafood that people choose. Shrimp and salmon are still the most popular choices.

22 CALS Magazine

For those unfamiliar with oysters, or maybe even wary of them, consider these salty jewels an adventure for your taste buds. Oysters possess their own distinct flavors, known as “merroir,” derived from the unique aquatic environments in which they are grown. Some oysters might have a savory umami taste while others have a mineral flavor. They can be rich or light, and their saltiness varies widely.

Despite these qualities, Harrison has found that many people are still unsure about when to eat oysters, how to prepare them, and whether or not they’re safe to eat. She sees the NC Oyster Trail as a critical educational tool for consumers and policymakers.

To ensure the NC Oyster Trail would be successful, Harrison conducted a market demand study led by Whitney Knollenberg, an associate professor in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism. Feedback from over 1,000 coastal visitors and local seafood consumers helped determine the level of potential interest in an oyster trail. Harrison and her colleagues used the results to map out a trail with a variety of family-friendly opportunities to help ease oyster skeptics into the wonderful world of life on the half shell.

“Our study showed a high demand for seafood educational experiences, especially for shellfish farm tours,” Harrison says. >

FALSE Myth Busting: Only Eat Oysters in “R” Months

Before refrigeration, harvesting oysters in hot summer months (those without “R”s) from May to August made it difficult to bring the oysters down to 50 degrees quickly enough to prevent bacterial pathogens. With the advent of ice and refrigeration, that’s no longer true for farmed oysters.

BUT … wild oysters are off-limits for harvesting in non-”R” months because they spawn in the summer.

cals.ncsu.edu 23

“The NC Oyster Trail is about changing our culture, one oyster at a time.”

Cody Faison Co-owner Ghost Fleet Oyster Co.

Shellfish Farm Tours

NC OYSTER TRAIL

Opposite: Staff at Ghost Fleet Oyster Co. provide a unique educational experience.

Photo by Justin Kase Conder.

According to their study, the average willingness to pay for an oyster farm tour was $150 per person. Whether booking a private boat tour in Topsail Sound or ordering a dozen fried oysters for happy hour in Raleigh, visitors to the NC Oyster Trail are part of the seafood industry’s $300 million annual contribution to the state’s economy. That significant economic impact comes with positive environmental impacts as well.

“People really do want to understand how oysters are grown and their role in the coastal ecosystem,” Harrison says.

Wild oysters provide many ecosystem services as a keystone species. An individual oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day, which greatly improves water quality. They also supply food for other marine organisms and provide spawning habitat for juvenile fish and crustaceans. However, their numbers have been decimated over the years due to overharvesting and environmental degradation.

The NC Oyster Trail works to counterbalance this pressure on wild oysters by promoting the consumption of farmed oysters. Some sites on the trail showcase living shorelines made from recycled oyster shells that create new wild oyster habitat and protect coastal land from hurricanes. The NC Oyster Trail offers boat and kayak tours of conservation projects as well as volunteer opportunities to help restore damaged environments.

“The NC Oyster Trail is about changing our culture, one oyster at a time,” says Cody Faison, co-owner of Ghost Fleet Oyster Co., which offers customized oyster farm tours in Hampstead.

Three years into running the NC Oyster Trail, Harrison’s ongoing surveys have found that nearly 90% of visitors are satisfied with their experience. Another sign of success: Farmed oysters now represent more than half of all the oysters consumed in North Carolina.

“We want those who depend on the coastal environment for their livelihood to be successful,” Harrison says. “Especially in our coastal communities, working on the water is a heritage. It’s a part of North Carolina’s history. Being able to sustain and evolve these practices is critical to maintaining our culture, for our sense of self and identity.”

From The Writer:

“As a self-proclaimed ‘foodie,’ the daughter of a former chef, and a generally adventurous eater, even I had not yet tried an oyster at the age of 30—until I was assigned to write this story. I’ll admit, I was nervous at first. Would it be slimy? Gooey? Overwhelmingly salty? No, friends. Emphatically, no. Instead, my first oyster was full of surprises, served raw on the halfshell with nothing but a squeeze of fresh lemon juice. Yes, it was cold and wet and salty, but the texture I was so afraid of went more or less unnoticed. It was fresh and bright with a lovely shellfish flavor, bereft of any fishiness whatsoever. Thanks to the NC Oyster Trail, I can now proudly add the eastern oyster to the long list of foods I love and crave. Consider me one more oyster skeptic who has been converted into a bonafide bivalve believer.”

24 CALS Magazine

Writer Sam Jones eating her first oyster.

82% are N.C. residents

18% are from out-of-state (top visitation states: Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania and South Carolina)

Importance of Oyster Trail Experiences to Visitors

Where Oyster Trail Tourists Come From Oysters and Food Safety

77% Eating oysters on a tour

74% Meeting oyster farmers

72% Purchasing oysters from a farm

Bacterial pathogens can live in raw oysters, but many precautions are taken before reaching the consumer’s plate.

“The Division of Marine Fisheries does not allow the harvesting of oysters from water bodies that have poor water quality. If there is a rain event, which creates some pollution from runoff from the nearby land, they will automatically close shellfish beds in that area. They will then test the waters before they’re allowed to be harvested again.”

Jane Harrison

Cooking to an internal temperature of 145°F kills harmful bacteria in oysters. Food safety experts recommend that people with compromised immune systems or chronic health issues avoid raw or undercooked shellfish.

For more information about the NC Oyster Trail, visit ncoystertrail.org.

cals.ncsu.edu 25

TIP

A BEAUTIFUL BALANCE

By D’Lyn Ford

By D’Lyn Ford

26 CALS Magazine

Above:

Kara Pawlowski performs Joan Nicholas-Walker’s piece “Thursdays” at the spring 2022 State Dance Company concert. Photo by Robert Davezac. Opposite: State Dance Company members (from left) Kellsie Jennings, Madison Kotyra and Savanah Buck performed Kara Pawlowski’s choreography for “Complexities of Loneliness.”

Photo by Jillian Clark.

More online go.ncsu.edu/Kara

As a child, Kara Pawlowski danced in her room, making up routines and performing all of the parts herself.

“I’ve always just had an inclination toward choreography,” she says. “I’ve danced seriously since I was 12, which is actually a pretty late start for dancers—you’re supposed to dance the second you’re born. But then I did competitive dance for about eight years, and that led me right up into college.”

The latest works from Pawlowski’s imagination are coming to life on stage at North Carolina State University with State Dance Company, led by Tara Mullins. In fact, Pawlowski’s initial choreography project won a Creative Arts Award in dance from Arts NC State.

Pawlowski came to NC State from the Charlotte area to major in chemistry. Because of her interest in plants and agriculture, she gravitated toward biochemistry in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

In addition to studying six hours daily for her classes, she’s started working in a CALS genetics lab to help find the best maize for cereal makers. In addition, she curates a walking tour of JC Raulston Arboretum that explains the chemical structure and medicinal uses of various plants.

“I’m always looking for opportunities to grow and explore biochemistry in a new light,” Pawlowksi says.

A demanding schedule makes her dancing essential.

“Dance is an incredible break from all the academic stress,” Pawlowski says. “Everyone in the company, almost, is a STEM major, so we can all relate to each other in that way. And it’s just a true release from all that. You don’t have to think about microbiology or genetics or organic chemistry when you’re dancing, which is nice.

“For me, it is definitely a creative outlet. I could not do school if I didn’t have dance.”

Pawlowski performs and teaches her choreography to others in the company, with support from fine arts faculty and visiting guest artists.

Her first staged piece, “Complexities of Loneliness,” represents the struggle with an emotion she’s had to work through herself. Three State Company dancers, Savanah Buck, Madison Kotyra and Kellsie Jennings, perform dressed as mimes—lonely characters. Two of the women have heart symbols on their costumes.

“Savanah, who I call the main mime and who doesn’t have the heart, is on a journey of finding self-contentment,” Pawlowski says.

But it isn’t necessary to know Pawlowski’s intent to enjoy the 6-minute performance piece.

“I do hope people see that she’s missing something in the beginning, and then she gets it at the end,” she says. “They can kind of fill in the blanks of what they think that means.”

As Pawlowski continues her studies, the next steps of her career are becoming clearer.

“I would love to work in a lab and maybe go to grad school to get a master’s to be a leader in a lab position.”

cals.ncsu.edu 27

“Dance is an incredible break from all the academic stress.”

BENEFITING FARMERS

Ag-ri-tour-ism

noun:

AND CO M MUNITITES

By Alice Manning Touchette

Unique, authentic, sustainable. Farm agritourism revenue tripled across the United States between 2002 and 2017. Learn why farmers, entrepreneurs and the next generation are utilizing creativity and ingenuity to draw visitors—and profits—via experience-led agriculture.

Diversification is more critical for farmers than ever before. Adding agritourism activities can generate additional farm income, boost rural economies and cultivate relationships with North Carolinians statewide, including those unfamiliar with farming. In addition to seasonal favorites like pumpkin patches and pick-your-own operations, savvy farmers are creating one-of-a-kind venues and experiences.

Farm agritourism revenue tripled in the United States between 2002 and 2017. Though small relative to total farm revenue, agritourism income helps both family farms and the surrounding communities.

“Agritourism is not for every farmer,” says Carla Barbieri, NC State Extension specialist and agritourism researcher in the College of Natural Resources. “But for farmerentrepreneurs, it’s a great option to try something new. It’s an opportunity to regenerate and keep your farm alive.”

Some farms repurpose existing resources to support direct sales and agritourism activities. That may consist of converting an old tobacco barn into a gift shop carrying jams made from the farm’s fruit, like the one on Gross Farms outside of Sanford, North Carolina.

Diversified enterprises that farmers develop to make more money to add value to their overall business.

“The key is open-mindedness and realizing what skill sets you have within your family,” says Tina Gross, former president of the North Carolina Agritourism Networking Association and business manager of Gross Farms. “You can’t put all your eggs in one basket.”

Gross Farms, now run by the sixth generation of the family, diversified their row crop operation of tobacco, soybeans, rye and corn, adding strawberries and pumpkins in 2000. In addition to pick-your-own activities and the barn shop, Gross Farms has an annual corn maze, pumpkin patch, hayrides and children’s play area.

Gross runs the agritourism and business end of the farm while her husband John, sons Cody and Colton, and son-inlaw, Wesley, farm the land and tend the crops. Her daughter MaKayla, a CALS crop science alumna who works full time with AgCarolina Farm Credit, joins younger sister Kassidy at busy times to help with social media, marketing, special projects and event planning. During the six-week peak season in the fall, the Gross family spouses, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins and family friends all get involved.

“For agritourism to work, it’s got to be truly genuine,” Gross explains. “We’re an authentic working farm, and we provide an experience that appeals to visitors’ senses. When they smell or see a strawberry, it brings back the memory of our farm.”

A statewide study by Barbieri and her colleagues revealed that after visiting a farm, consumers increased their appreciation for local food and were willing to pay more for it.

28 CALS Magazine

More online at go.ncsu.edu/Agritourism2023

“We saw a 5% to 20% increase in likelihood to purchase local foods even if they were more expensive,” Barbieri says. “When they see the family farm label in the store, they will buy it because they have been there. That’s huge for our state’s economy and local food systems.”

Full Integration

While Barbieri describes North Carolina agritourism as mature, there is room for more integration with farms, communities and consumers.

Gross sees an example of that in Sanford, a 30to 45-minute drive from the Triangle. Her customers are daytrippers wanting an escape from urban living.

“Visitors come here not just to experience pickyour-own at our farm, but to eat at local restaurants and attend festivals in our small town centered around produce and live music,” Gross explains.

Advanced agritourism engages the whole community, Barbieri says. “Everybody related to overall local food production, such as farmers, chefs and bakers, is involved. All of those local experiences integrate into one product for consumers, giving them a reason to visit and come back.”

“No matter where you go, you will find some sort of agritourism, but the experience is different in each farm,” Barbieri explains.

If you’re in California’s Napa Valley, agritourism looks like winery tours and a chef-prepared meal with a wine pairing menu. In Texas, it may be staying on a dude ranch and roping cattle. In New England, think glamping in a maple grove and tasting unique cheese from dairy farms. And North Carolina has a wide spectrum of agritourism experiences. >

cals.ncsu.edu 29

N.C. Agriculture and Agribusiness (food, fiber and forestry)

$103.2B in economic impact for N.C. employs ~1 in 5 employees statewide generates 16% of the gross state product

30 CALS Magazine

Community Spirits

You’ve heard the phrase, “it takes a village.” When it comes to Social House Vodka’s step into agritourism, it takes a village, a farmer, an entrepreneur and a gaggle of NC State researchers.

As a result, Social House became North Carolina’s No. 1-selling craft vodka four of its six years in production. Its distillery became the latest agritourism destination in rural Kinston.

Social House Vodka is distinct for a few reasons. First, it’s distilled from corn grown only 20 miles from its distillery. Second, its water comes from a million-gallon reservoir filled by three deep water wells to the Black Creek Aquifer, which runs under the sandy, fertile soil in Eastern North Carolina. Social House’s smooth sweet, peppery taste has made it a popular craft spirits choice within the state. But success didn’t happen overnight.

CALS Researchers Inform Recipe and Process

“We were very fortunate to work with NC State,” says Cary Joshi, founder and president of Social House Vodka. “First we started with MaryAnne Drake’s team in the Food, Bioprocessing and Nutrition Sciences department to understand what elements in vodka’s chemistry make it taste the way it does.”

Drake’s team tested 24 different brands of vodka via gas chromatography mass spectrometry, a research method that identifies substances in a liquid sample.

“Her team helped us analyze various vodkas and interpret how the results affect the various taste profiles,” says Joshi. “With their help, we came to understand what makes one vodka good, what makes one smooth, what makes the texture different, and so on.” >

cals.ncsu.edu 31

NORTH CAROLINA

Visitors gather around for a tasting while touring the Social House distillery in Kinston, N.C.

“Small businesses lift up America. We connect with and work with our community. We have seasonal menus and source everything from watermelons to botanicals from local farmers for the cocktails in our tasting room. It’s good for everybody. ”

Cary Joshi, Founder and President Social House Vodka

Cary Joshi, Founder and President Social House Vodka

32 CALS Magazine

Sylvan, Warren and Justin Hardy represent three generations of growers at Warren Family Farm.

Next, Joshi and his team turned to Wayne Yuan and Ying Liu in the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering to pick the perfect corn for their product.

“Their team assisted us in the evaluation of starch content in different strains of corn to select the specific strain that would give us the taste that we wanted,” Joshi says. That corn is grown by Warren Hardy Farms in Seven Springs, North Carolina, a 20-minute drive from the distillery.

Next, the Social House team turned to NC State bioprocessing engineer John Sheppard, an expert in food and beverage fermentations. Sheppard helped Joshi develop operating procedures for brewing corn mash, yeast propagation and fermentation.

A Small and Mighty Community

Social House chose eastern North Carolina as its home base. Kinston is the birthplace of Mother Earth Brewing, a craft brewery, and Chef and the Farmer, Vivian Howard’s farm-to-table restaurant that put the city on the culinary map. Kinston’s agrarian economy was once driven by cotton and tobacco but has reinvented itself around local food and the arts.

“When we were looking for a place to set up, we came to Kinston and met with local business owners. The farm-totable movement was booming,” Joshi says. “We met with Wilbur King from King’s Barbecue and Stephen Hill, who

started Mother Earth Brewing and was behind the revitalization of downtown Kinston—we wanted to be a part of this town’s renaissance. The community was committed to bringing the town back and making it a destination through the culinary and visual arts.”

They set up the distillery in a former power plant on the banks of the Neuse River. After launching the vodka and the brand, they opened The Pumphouse 1906, a speakeasy cocktail bar and tasting room where folks could gather socially or enjoy themselves after a distillery tour.

“Being able to show folks how it’s made also helps create a deeper connection to the brand,” Joshi says.

Hyperlocal Agritourism Success

The team takes care to keep Social House Vodka hyperlocal, sourcing boxes from Bethel, labels from Salisbury, and botanicals and fruits from local farmers.

“Small businesses lift up America,” Joshi says. “We connect with and work with our community. It’s good for everybody.”

Next, Social House plans to release new spirits: two whiskeys, a gin and a limoncello. In addition, they partnered with Harvest Host to allow RV campers to stay on the distillery land for free. Another Kinston farm is offering a glamping option, and the retro, revitalized Mother Earth Motor Lodge downtown offers visitors another place to spend the night and extend their stay.

“We created Social House to encourage our customers to spend time with and create moments with friends and family,” Joshi says. “Now we draw bookings from all over the country. They come to Kinston, visit our tasting room and take a bottle back to wherever they are staying.”

Social House has proven that advanced agritourism with a niche, authentic offering can succeed not only for its business, but also for farmers who supply the produce, the local economy and consumers looking for a memorable experience. >

cals.ncsu.edu 33

NORTH CAROLINA

Localizing Luxury

When you think about North Carolina farm attractions, strawberries, sweetpotatoes and Christmas trees may come to mind—but what about caviar?

Family-owned and -operated Marshallberg Farm, with a state-of-the-art recirculating aquaculture system (RAS), is opening its doors to agritourism in the hopes of educating the public about sustainable aquaculture and their specialty: coveted Osetra caviar.

The Making of a Fish Farm

Marshallberg Farm started in 2008 and has since become the largest indoor RAS sturgeon farm in the United States. With two farms, they have four grow-out buildings to raise Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii) in addition to processing facilities. Marshallberg Farm is committed to sustainably producing caviar and meat to help reduce overfishing and facilitate wild sturgeon conservation. With a profit some 13 years in the making, Marshallberg Farm is the largest producer of Osetra caviar in North America.

Marshallberg Farm is the passion project of retired NC State professor of geophysics I.J. Won, Ph.D. Owner of a 300-acre coastal farm in Smyrna, North Carolina, and another similar-sized facility in Lenoir, North Carolina, Won built his Smyrna commercial-scale aquaculture farm in 2010—a $10 million investment.

“When my dad started the farm, he wanted to create a venture of sustainable aquaculture. RAS is the only truly sustainable technology in aquaculture,” explains Won’s daughter and business partner, Lianne Won-Reburn. “It’s as much a water treatment plant as it is a farm. It just happens to have fish in it.”

Won-Reburn’s husband Brian Reburn, a water treatment professional, oversees the feeding and care of the sturgeon and day-to-day operations at the fish barn, ensuring the delicate balance of the RAS. With over 30,000 fish—the females are worth nearly $5,000 each—and a long maturation process, it’s a big job. >

cals.ncsu.edu 35

NORTH CAROLINA

With aquaculture, success depends on water quality control. The RAS recycles a million gallons every hour through a series of filtration systems before it goes back into the tanks.

“Ninety-five percent of our water is filtered and reused,” Won says. “The little bit of effluent, or liquid waste, that we produce we give to local farmers and gardeners to use as fertilizer.”

Marshallberg Farm hopes to work closely with researchers at NC State’s Marine Aquaculture Research Center (MARC), hosted on a 6-acre plot of Won’s farm, on further research and development of sturgeon aquaculture in North Carolina. MARC is led by Steven Hall, a professor in the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, and William White Jr., Sturgeon Aquaculture Distinguished Professor in Biological and Agricultural Engineering. Alex Chouljenko, assistant professor and director of the seafood technology program at NC State’s Center for Marine Sciences and Technology (CMAST), is also involved with the farm.

Marshallberg Farm works with CMAST to test samples of the caviar, and Chouljenko is working to develop a DNA test for the sturgeon to help determine the sex of the fish before their sex organs mature at around age 5.

The crew currently determine the sex by performing an ultrasound on each fish, after which the males and females are moved into separate tanks. The males are harvested for sturgeon meat, which is smoked on site. After 7 to 10 years of maturation, female sturgeon produce 80,000 to 100,000 eggs that are harvested as roe.

The Cost and Reward

Wild Caspian sturgeon are among the most endangered species on Earth. According to the World Wildlife Fund, their scarcity is due to overfishing, loss of habitat and an illegal caviar trade. Aquaculture is an important component in conserving sturgeon and the only way to sustainably produce Osetra caviar. Conservation and sustainable fish farming are pillars of Marshallberg Farm. The practices come with a healthy price tag but a huge potential reward.

Marshallberg Farm enforces strict food safety and environmental regulations at their aquaculture facilities and feeds the fish a high-quality diet designed just for them. “You have to be patient and have enough resources to keep feeding the fish and keep the aquaculture system running,” Won-Reburn explains. Ranging from $65-$180 per 1-ounce tin of caviar, the delicacy is expensive and in demand by

chefs and foodies. The niche product has the potential to create a financial boon for Marshallberg Farm and prove sustainable aquaculture as a business model for farmers.

“Raising sturgeon for caviar makes economic sense for an RAS farm,” Won says. “The U.S. imports over 90% of our seafood from companies and farms that wouldn’t pass USDA or FDA regulations, or they’re not following sustainable fishing practices and destroying the ecosystems in the oceans and rivers. So our goal is to produce seafood in the U.S. in a sustainable way. Caviar is the place to start from the top down because it can sustain the high cost to run a sustainable RAS farm.”

That sustainability model is also popular with informed consumers. Marshallberg Farm hopes to raise different species in the future as the technology and their profits improve.

Demand for Agritourism

Once word got out that Marshallberg Farm was raising Caspian sturgeon on an aquaculture farm in eastern North Carolina, an influx of interested people wanted to see how.

“We get a little boost in sales from agritourism, but we’re not doing it for the money,” Won-Reburn says. “We’re doing it because people call all the time wanting tours. And it’s been interesting seeing the connections we’ve made that have helped our business.”

Agritourism helps customers connect with the farm on a deeper level. The experience includes an in-depth tour of the RAS Osetra sturgeon farm, caviar tasting with champagne and vodka, sampling of smoked sturgeon products and the opportunity to purchase Marshallberg Farm products.

“Visitors get to see what we do and they remember it. They experience it,” Won-Reburn says. “That kind of grassroots marketing, where they have a great experience and can tell their story, helps our reputation. It’s good for the soul of our company.”

About two dozen restaurants on the East Coast have Marshallberg Farm caviar on their menus regularly or for special occasions. Direct sales are starting to pick up, and Won-Reburn enjoys hosting tour groups from nearby Beaufort and other towns on the Crystal Coast. She hopes to see the farm turn a larger profit so they can expand the agritourism business and continue to grow their sustainable aquaculture farming.

As for her father, “He’s still going strong,” Won-Reburn says. “There’s always some vision he’s working toward.”

36 CALS Magazine

“The U.S. imports over 90% of our seafood from companies and farms that wouldn’t pass USDA or FDA regulations, or they’re not following sustainable fishing practices and destroying the ecosystems in the oceans and rivers. So our goal is to produce seafood in the U.S. in a sustainable way.

I.J. Won, owner of Marshallberg Farm and retired NC State professor of geophysics

cals.ncsu.edu 37

Aerial view of Marshallberg Farm.

Reading an ultrasound from inside the tanks.

Sturgeon tanks in the barns.

NORTH CAROLINA

Photos courtesy of Crystal Coast Development Authority and Marshallberg Farm.

Adult Osetra sturgeon

By Simon Gonzalez

The thought of speaking in front of people can cause some of us to break out in a cold sweat. Now imagine entertaining the group with a story or humor improvised on the spot.

Angela Galloway, 4-H agent in Scotland County, knows the feeling from performing at area improv clubs. It can be intimidating, but the challenge of overcoming anxiety and being instantly creative is overwhelmingly positive. So much so that she incorporates it into her youth development work.

“I’ve done an improv program project at four middle and elementary schools,” she says. “Kids who were shy, quiet, nervous getting up in front of people, by the end of the class they’re laughing, they’re loud, they’re participating. Their confidence is different.”

This fall, Galloway plans to launch a 4-H improv program.

“It builds confidence, builds self-esteem,” she says. “I see this project being an amazing fit in Scotland County, really all over.”

38 CALS Magazine

“Spin clubs are a great tool to introduce 4-H to the nontraditional audiences, those kids who really don’t know what it is.”

Crystal Starkes 4-H agent in Union County

An improv program might seem like an odd choice for a traditional 4-H club, but it’s perfect as a special interest (spin) club.

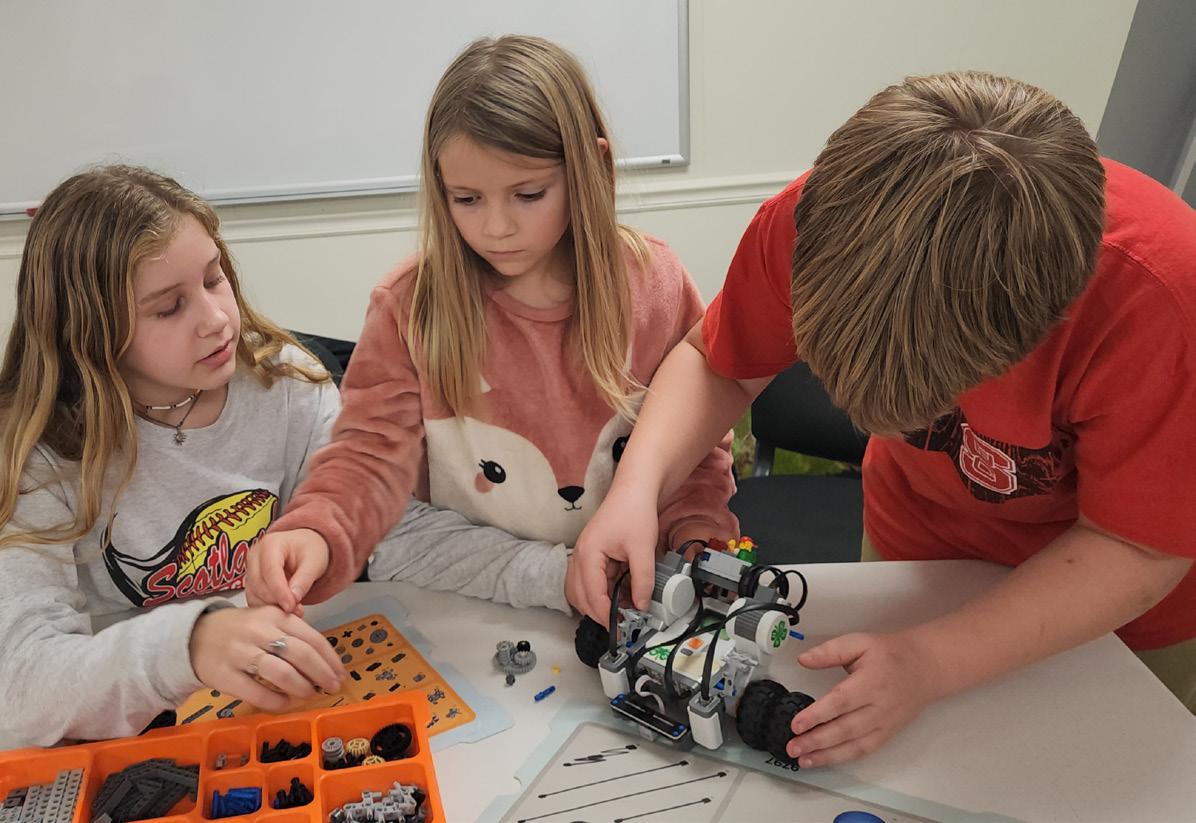

4-H is NC State Extension’s youth development program. Traditional clubs last for a semester or year, and are typically focused on livestock, agriculture and environmental stewardship, healthy living, science and technology, and community involvement.

Spin clubs cover several topics in six months instead of just one. They are designed to introduce topics, gauge interest for potential longer-term clubs, and recruit new members.

“Parents see it as a short-term commitment. Kids see it as an opportunity to try something new. And it is a great way to expose the community to the other areas of 4-H,” says Nicki Carpenter, 4-H agent in Burke County.

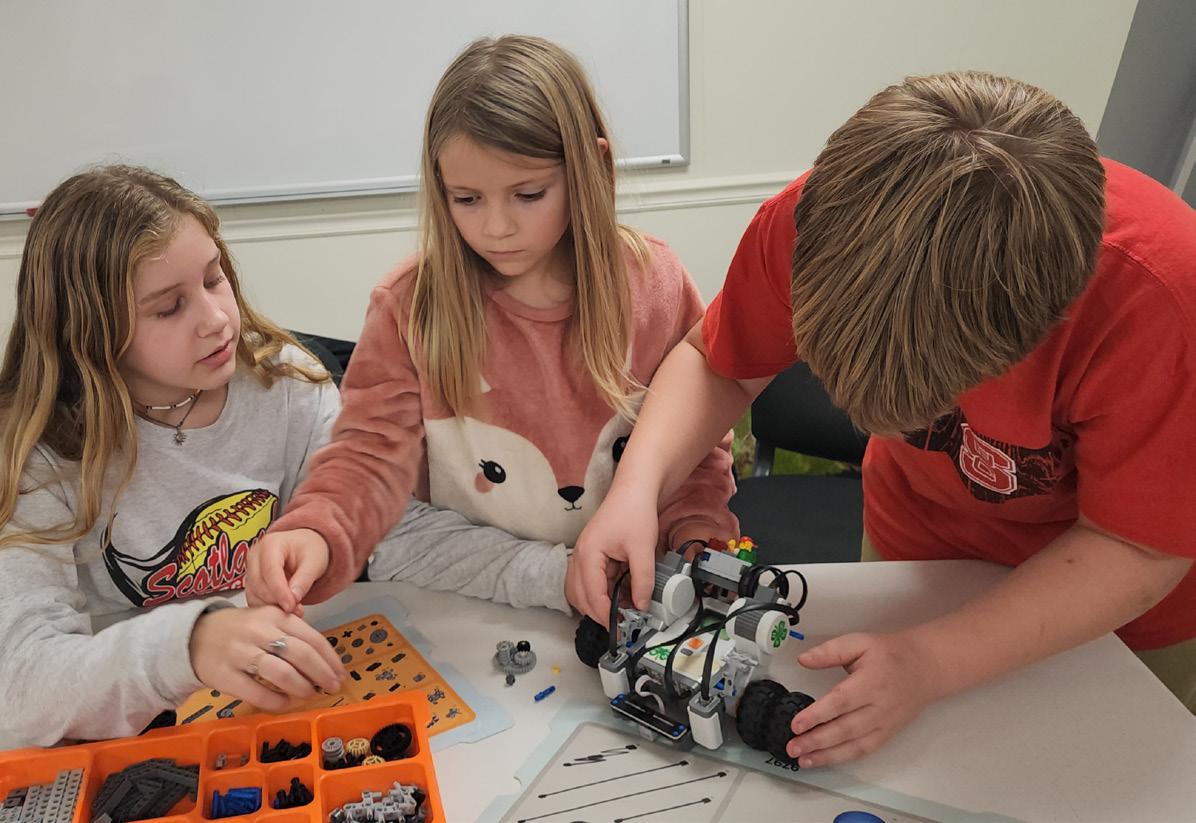

Carpenter has offered short-term clubs in sewing, culinary creations and creative arts. She has created clubs for teenagers and for cloverbuds (K-3rd grade).