Spring/Summer 2023 | Volume 2 | Issue 1

BOARD OF TRUSTEES, 2023-2024

Anthony (Tony) R. Sapienza, Chair

Paulina Arruda

Christina Bascom

Ricardo Bermudez

Susan Costa

Douglas Crocker II

Betsy Fallon

John N. Garfield, Jr.

David Gomes

Edward M. Howland II

Meg Howland

James Hughes

D. Lloyd Macdonald

Ralph Martin

Eugene Monteiro

Michael Moore, Ph.D.

Gilbert Perry

Victoria Pope

Dana Rebeiro

Maria Rosario

Lucy Rose-Correia

Brian J. Rothschild, Ph.D.

Nancy Shanik

Hardwick Simmons

Bernadette Souza

Carol M. Taylor, Ph.D.

R. Davis Webb

Alison Wells

Lisa Whitney

Susan M. Wolkoff

David W. Wright

Front Cover Image: Detail of Fred Albert Harvie (American, 1929-2005), Model of 227 Arnold Street, New Bedford, MA [Interior view] circa 1982. Dollhouse and interior furnishings, NBWM, 2021.30. Gift of Mary Edwards.

Back Cover Image: Detail from Daphne Ollivierre (Bequia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines; 1944-2021), Flensing a Pilot Whale at Petit Nevis, 1975. Hand-sewn cotton, 30 x 40 inches, NBWM, Kendall Collection, 2001.100.4867. Gift of Norman Flayderman.

Vistas: A Journal of Art, History, Science and Culture

Copyright © 2023 New Bedford Whaling Museum

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews and certain other non-commercial used permitted by copyright law.

18 Johnny Cake Hill

New Bedford, MA 02740

www.whalingmuseum.org

Spring/Summer 2023 | Volume 2 | Issue 1

Publisher

New Bedford Whaling Museum

President & CEO

Amanda McMullen

Design and Production

Brian Bierig, Graphic Designer

Consulting Editor

Naomi Slipp

Photography

Melanie Correia

Editor Michael P. Dyer

Contact

mdyer@whalingmuseum.org

(508) 717-6837

Scholarship & Publications Committee

Michael Moore (Chair)

Mary Jean Blasdale

John Bockstoce

Mary K. Bercaw-Edwards

Tim Evans

Ken Hartnett

Judy Lund

Daniela Melo

David Nelson

Victoria Pope

Brian Rothschild

Tony Sapienza

Jan da Silva

1 | Spring/Summer 2023

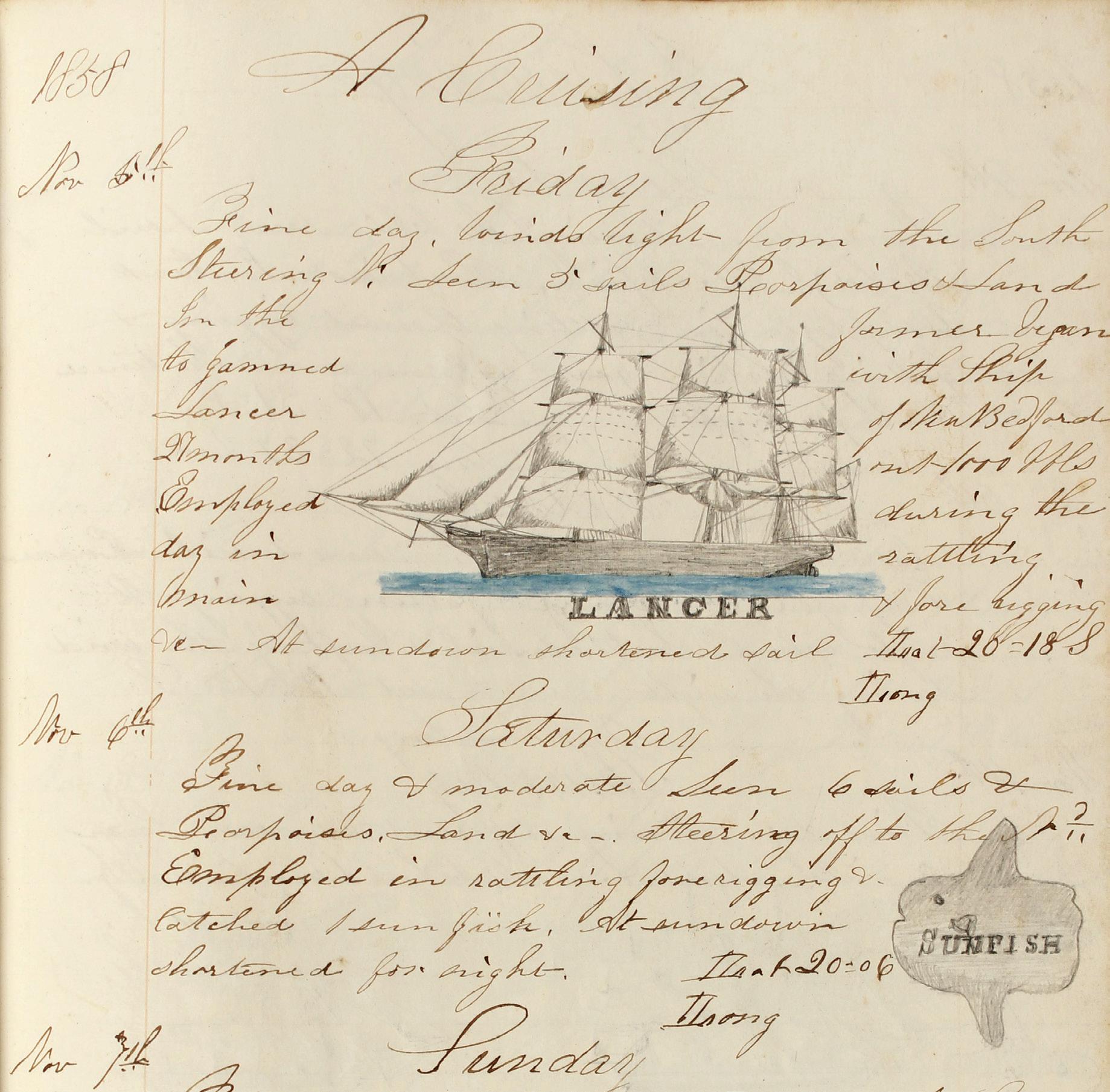

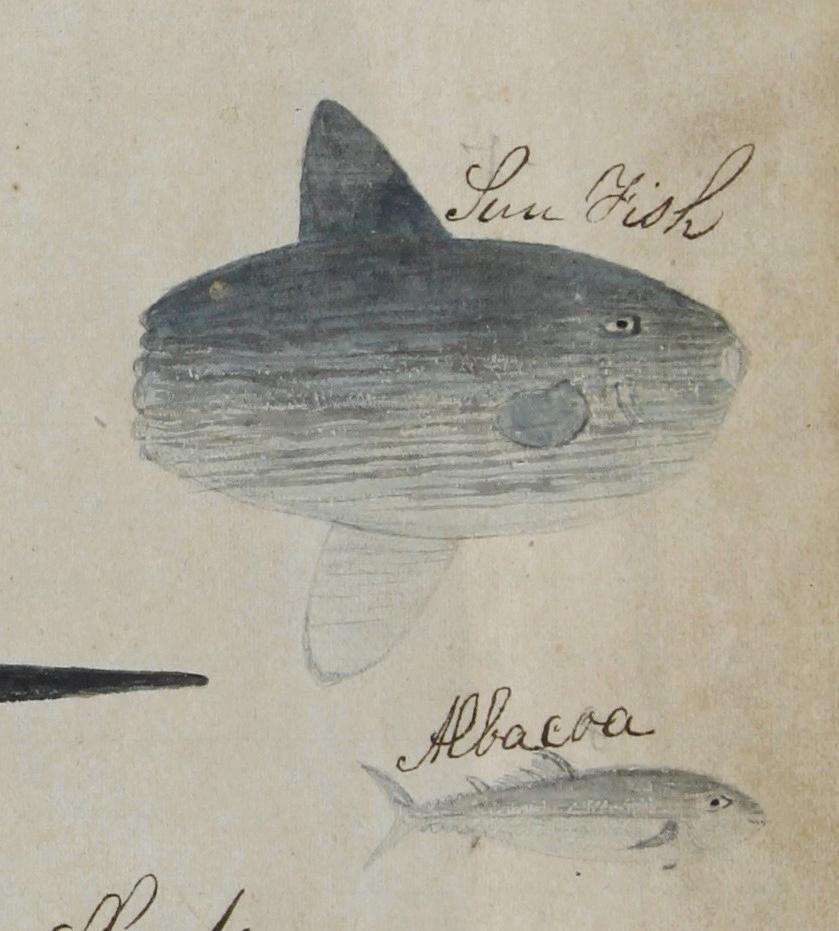

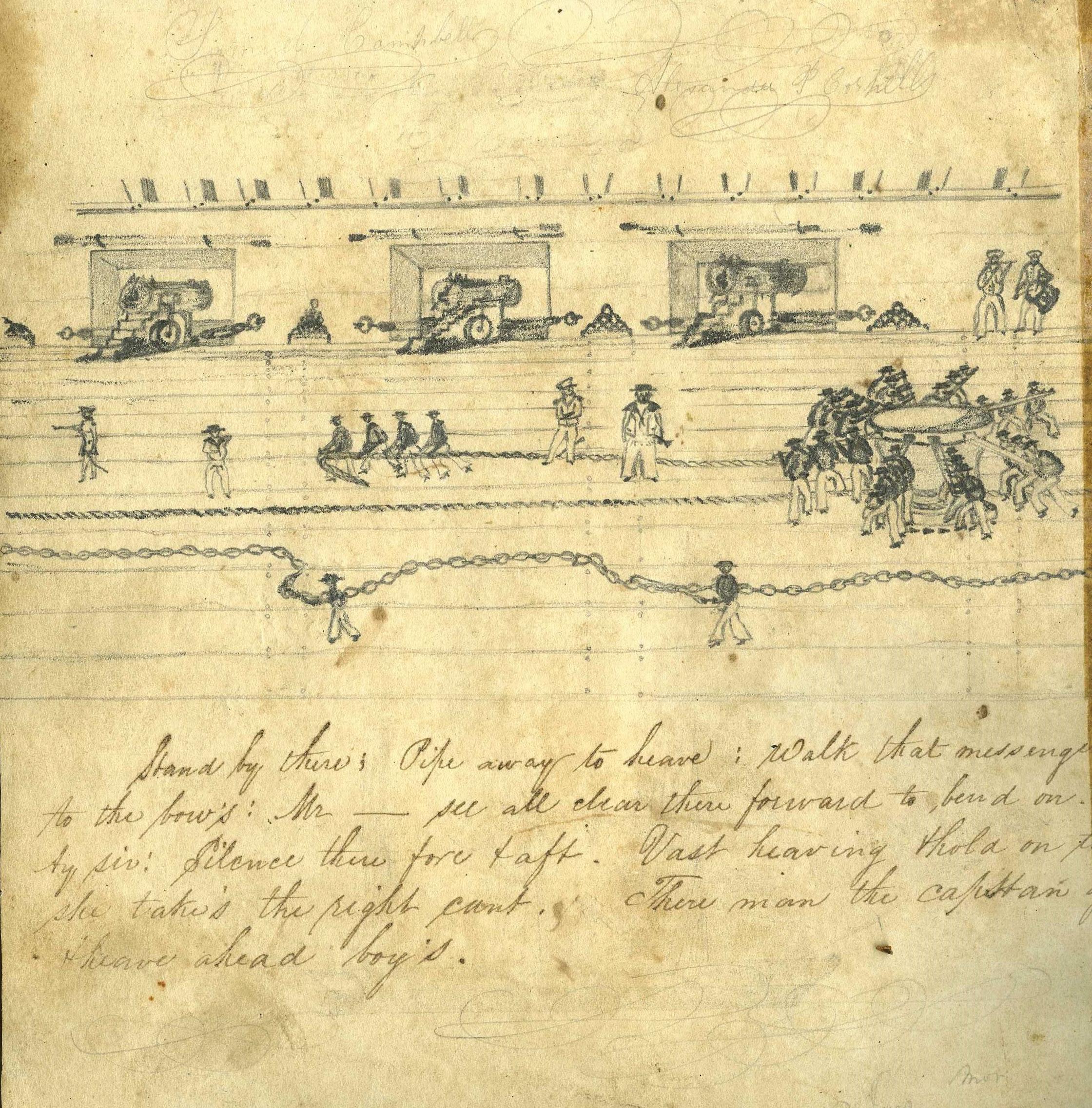

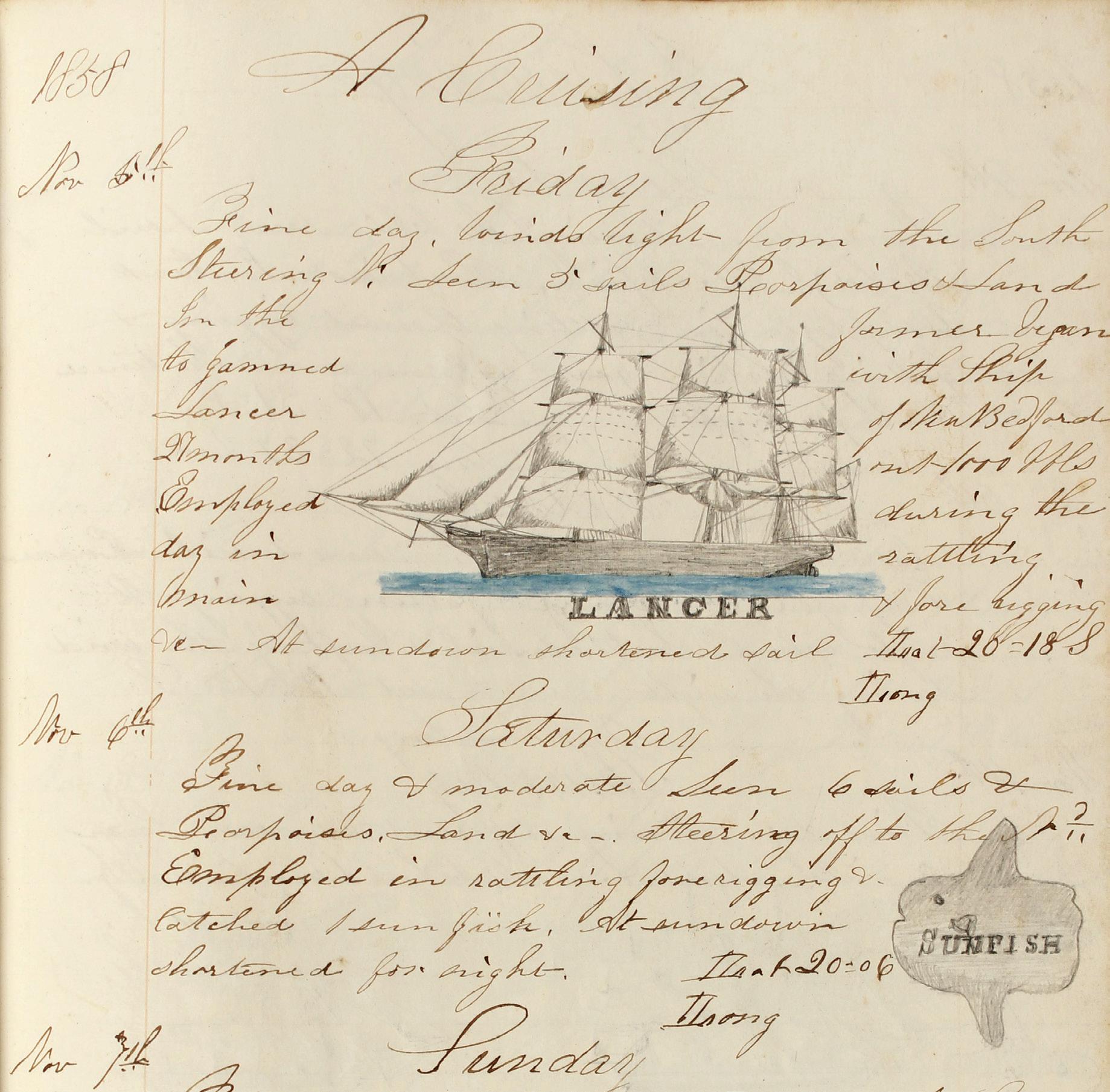

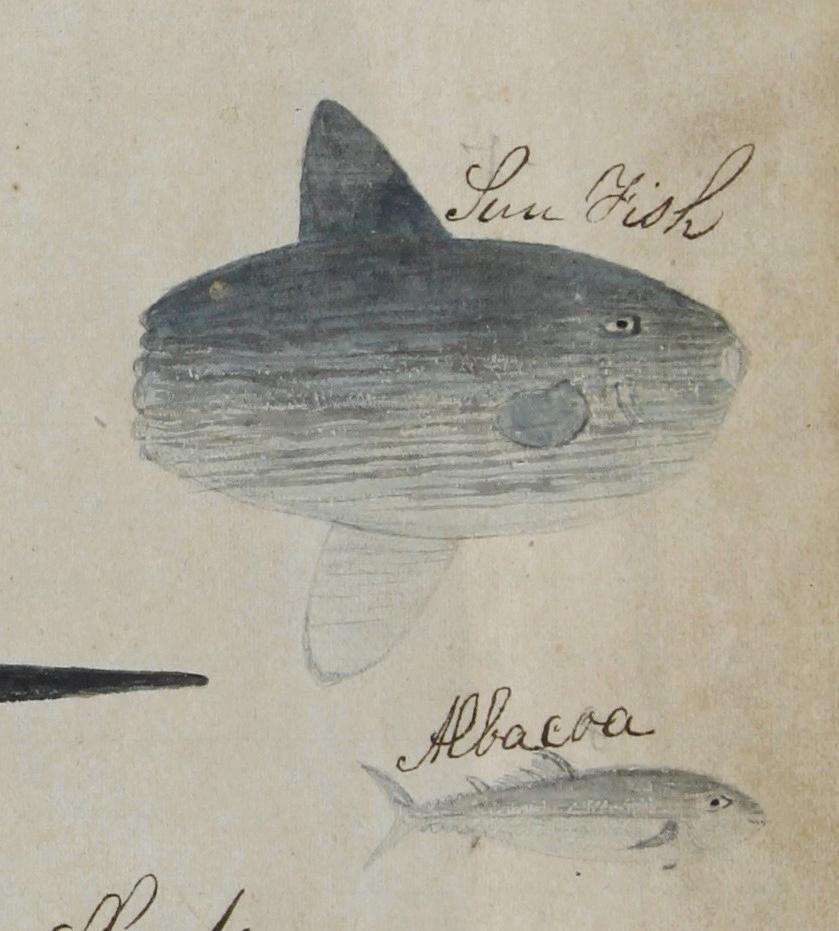

Dean Chase Wright (American, 1819-1895). Sea creatures including a sunfish drawn in his “Commonplace Book” kept onboard the ship Benjamin Rush of Warren, RI, 1841-1845. Pencil and watercolor on paper, 12 ½ x 7 ½ inches. NBWM, Kendall Collection. A-145.

Spreading

2 Contents Foreword ............................................................ 3 The Old Dartmouth Historical Society Finding Its Home, 1904-1916 5 Feature Articles From Sailors to Boarding House Keepers: Portuguese Mobility in New Bedford (1815-1900) By Anne-Sophie Coudray ......................................... 7 Documenting a Fred Harvie Miniature Model House By Dave and Marilyn Ferkinhoff ............................ 13 Book Talk Comets, Meteors, and UFOs in NineteenthCentury Skies By Mark D. Procknik ............................................. 17 Sharing Our Local History A Metaphor in Dartmouth: DHAS and its Quaker Transcription Project By Sally Aldrich, Robert J. Barboza, Richard W. Gifford, Robert E. Harding, Andrew Marcovici, and Marian Ryall .................................................... 21 From Our Fellows Picturing Pilot Whales, from George Hathaway Nickerson to Daniel Ranalli By Marina Dawn Wells 25 Paper Money and the “Free Banking Era” of 18371862: The NBWM Paper Currency Collection By Aidan Goddu..................................................... 29

About Stuff Stitching as Personal History: Quilts in the Collection By Naomi Slipp ...................................................... 35 Fresh Perspectives “A Catalyst for the Greater Good” By Waverly Verissimo 39

All

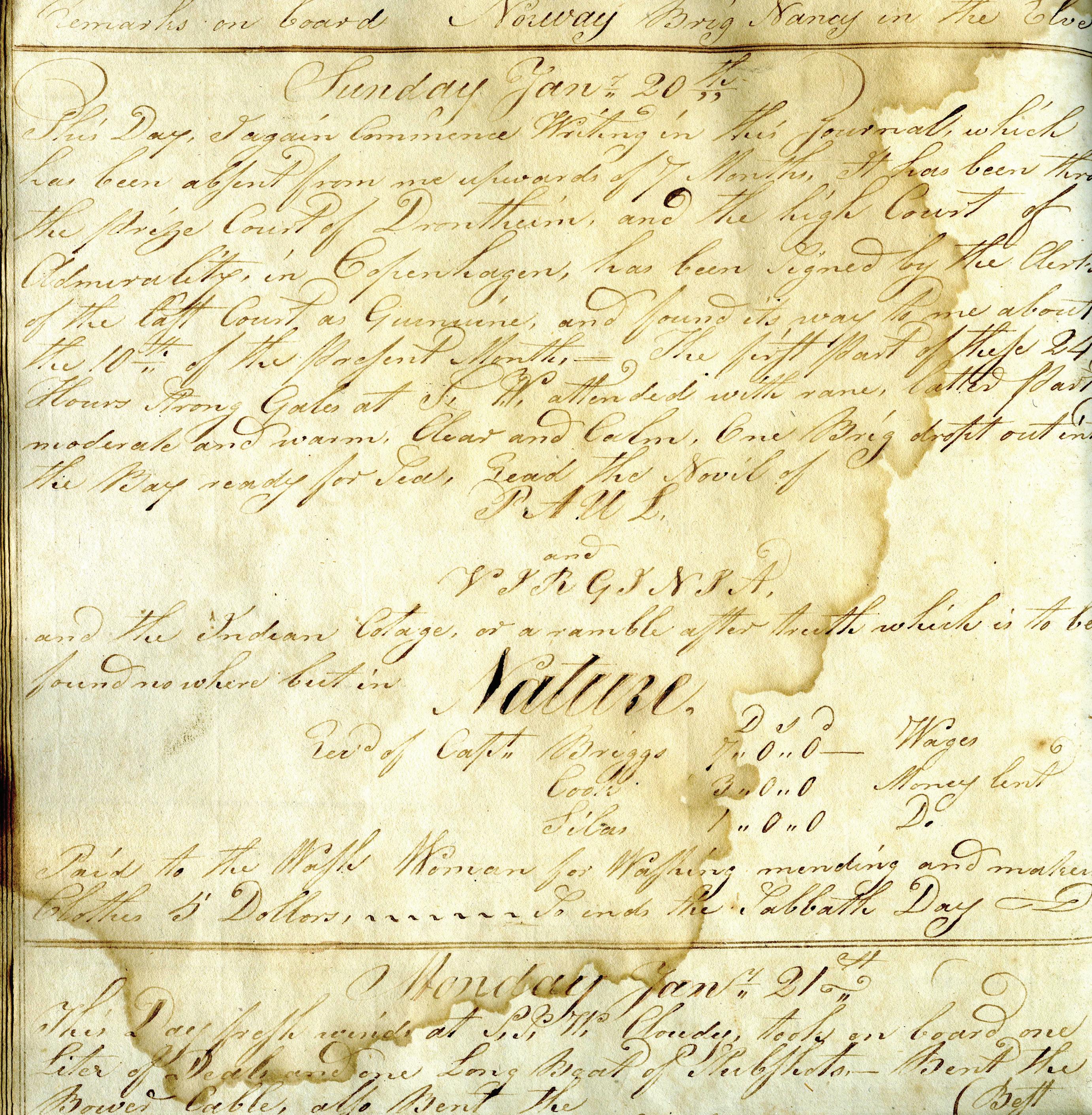

the Word “Contrary to both law and reason”: The Danish seizure

the

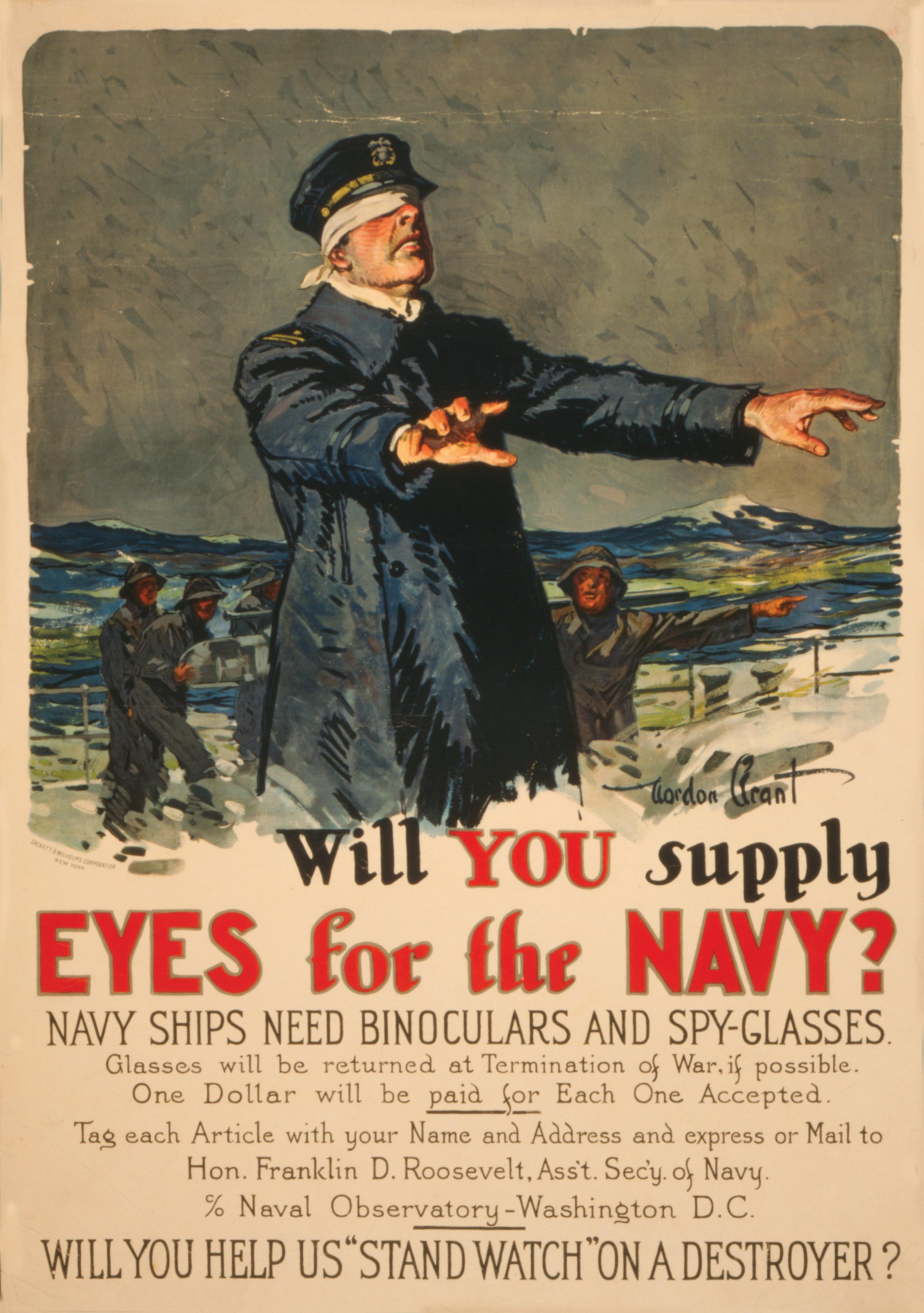

Nancy

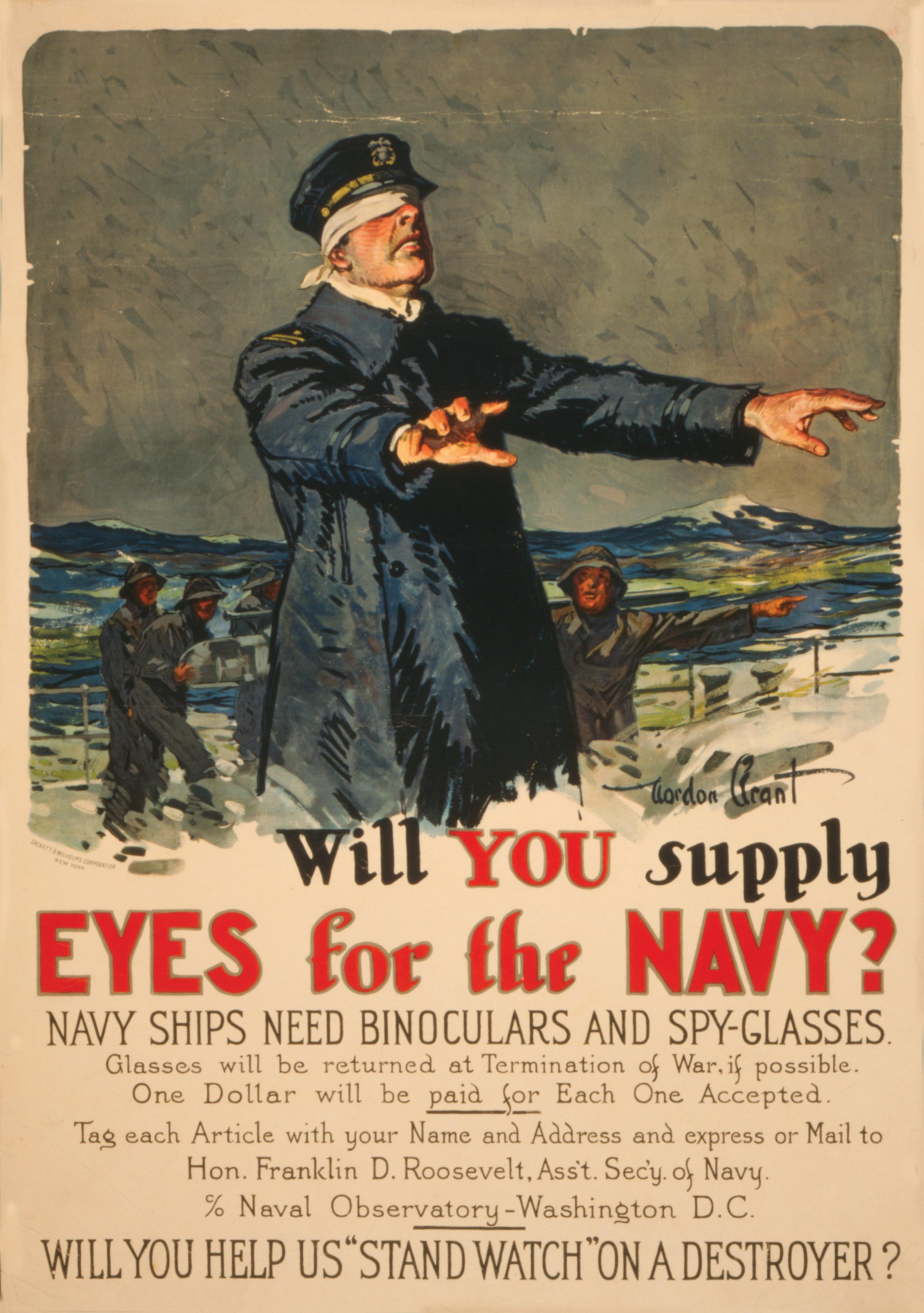

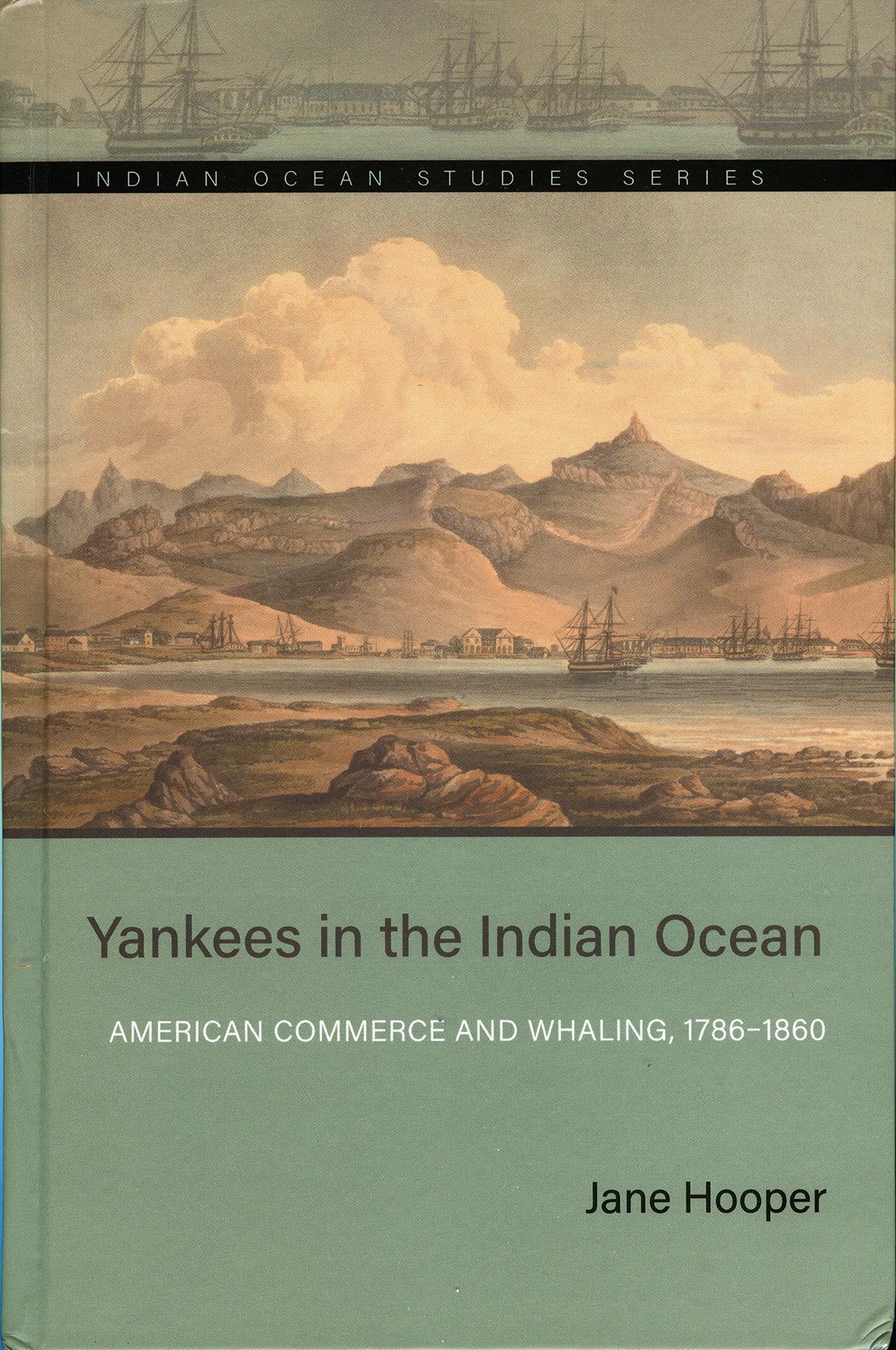

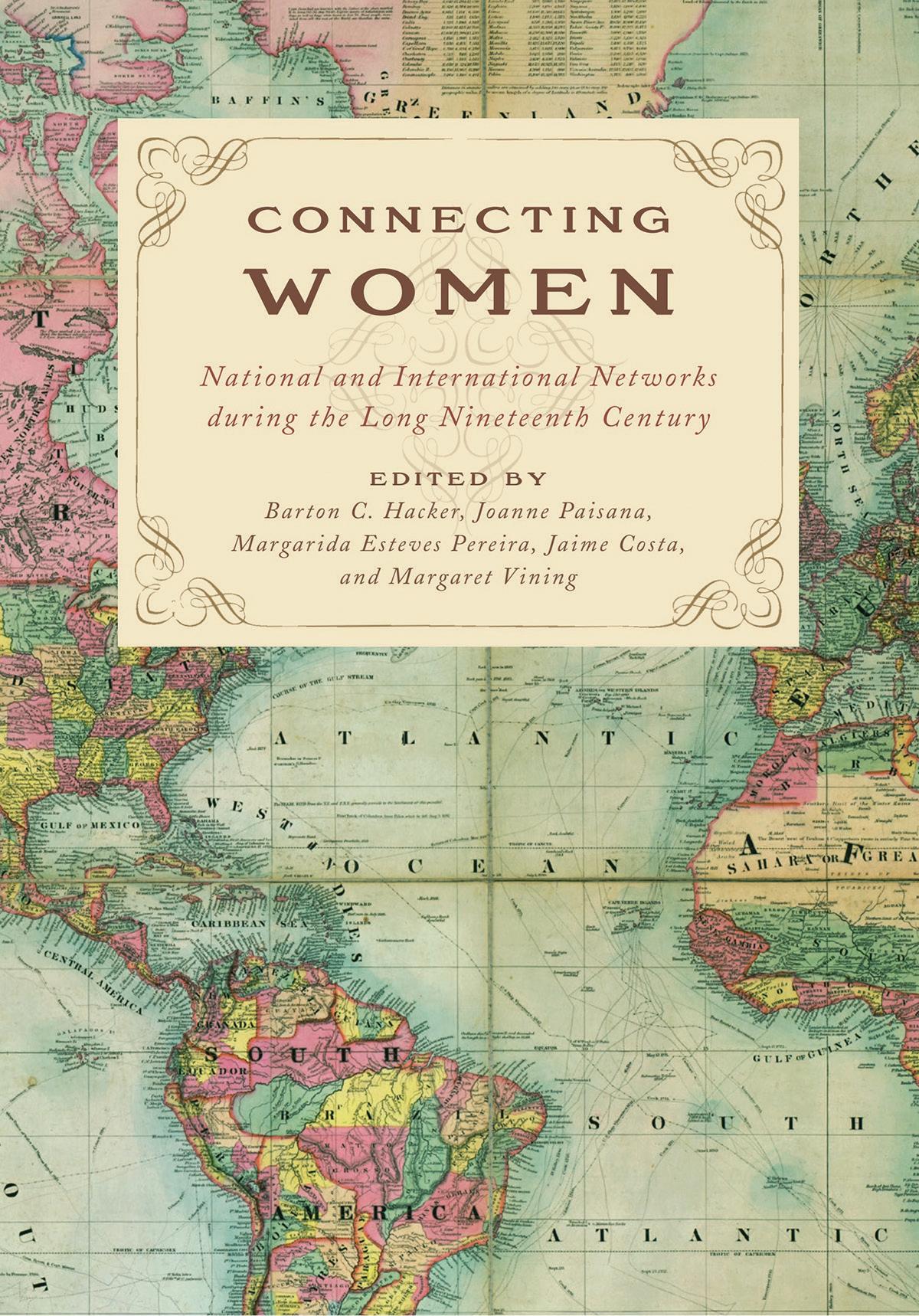

1810 Transcriptions by John Ricketson and Bob Hussey with explanatory notes by Michael P. Dyer ............. 41 Lighting the Way Women of Both Energy and Enterprise By Cathy Saunders and Carole Clifford .................. 45 Poetic Insights The Cutting-In. After reading Fathoms by Rebecca Giggs By Richard Dey 47 Animals and Issues Holy Mola! By Carol “Krill” Carson .......................................... 49 Exhibit Highlights A Singularly Marine & Fabulous Produce: The Cultures of Seaweed By Maura Coughlin ................................................ 53 Common Ground: A Family Reunited By Emily Reinl........................................................ 55 “All Hands”: Yankee Whaling and the U.S. Navy By Emma K. Sylvia ................................................. 57 Book Reviews Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds –A History of Slavery in New England By Janine V. da Silva 61 Yankees in the Indian Ocean: American Commerce and Whaling, 1786-1860 By Michael P. Dyer ................................................. 63 Connecting Women: National and International Networks during the Long Nineteenth Century By Anne Boyd 65

of

brig

of Rochester, MA,

By Bob Rocha and Emma Rocha 68 Spring/Summer 2023 | Volume 2 | Issue 1

Looking Back

Foreword

Our first issue of Vistas: A Journal of Art, History, Science and Culture was very well received. I am delighted to be providing our encore. With July 22nd marking 120 years of the Old Dartmouth Historical Society, this moment has me reflecting on the Museum’s legacy – an interesting, important, and complicated word.

Established as a legacy museum, our purpose was well defined by Old Dartmouth Historical Society President William W. Crapo, who noted in 1903:

No effort should be spared to preserve the story of the past, describe its events and incidents or keep alive the memories of the men and women who contributed to the advancement of the community. The coming generations are entitled to this knowledge, and it rests upon us to furnish it.

Last year when Daniel Weiss, President & CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, addressed members at our annual meeting he spoke about the creation and evolution of museums globally. Noting the unique nature of the “American museum experiment” in the 19th and 20th century, Weiss commented that “there was something very new and distinctive about the American museum,” because they are created by the local community and not established by kings or governments.

Thanks in large part to the trans-global whaling industry, our local community became one of the first truly cosmopolitan communities in the United States. Today, the New Bedford and SouthCoast population remains greatly diverse. The Museum’s five-year strategic plan, launched in 2020, prioritized the consideration of our institutional legacy and how we connect with and serve our community. Emphasizing our purpose through the overarching goals to Welcome, Engage, Steward & Thrive, NBWM chartered a deeper and more intentional path towards diversity, equity, accessibility, and

inclusion across our collections, galleries, staffing, and programming.

Putting focus on our community, we began our exploration by inviting feedback and I was pleased to hear from more than 500 members, neighbors, staff, trustees, volunteers and visitors. In 2021, I issued a report entitled “Building a Museum for All” which outlined a thoughtful, multi-year approach to advancing our commitment through deeds and not performative words. Since then, we have accelerated our efforts through numerous guided learning sessions for our staff, volunteers, and trustees, established a staff DEAI committee, increased representation on our board, shaped a position dedicated to the visitor and community experience, conducted a year-long Equity in Leadership learning program for our High School Apprentice alumni, created paid fellowships and internships, expanded the range of narratives and stories presented on our walls, and grown the diversity of our public programs. Every single step to date has resulted in increased visitation and broader community participation.

An important next step is to examine our collections and institutional history. A museum’s collection illustrates its priorities. It records whose histories were collected and, therefore, whose histories were deemed important at different moments in time. We must ask ourselves, when it comes to our collection: who is represented, who is underrepresented, and who is misrepresented? To be clear, this is not about eliminating narratives; it is about adding in. Our duty begs consideration of how we can best reflect the diversity of our community today, and strive to be responsible stewards for items in our collection that were created by Native and Indigenous makers.

Our work is being noticed and we are emerging as leaders in this critical space. Recently the Jessie Ball duPont Fund awarded us a $100,000 grant to accelerate our steps towards being a Museum for All. The grant will provide training for creating

3 | Spring/Summer 2023

sensory-friendly museum experiences to expand access, support work towards ethical stewardship in partnership with Indigenous descendant communities and heritage stakeholders, and underwrite the work of our staff Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion task force.

I have been asked if I am worried about what we will find when we look inward. My answer is simple: I am far more concerned about what we will find if we do not take these steps. Relevance is the quality of being closely connected. How can the NBWM engage in relevant leadership in the closely connected community of New Bedford without fully understanding who we are as an institution, how we got here, and where we are going?

In his closing address, Weiss noted the common question of who owns museums. In the United States, he noted, they are “founded by our citizens. In New Bedford it was 100 citizens who came together to create this museum. And it was founded by the idea that we will all own it, we will work together to develop a vision for this institution in service to our community.” He went on to observe that “over the course of more than a century in New Bedford, you have increasingly perfected the realization of that mission by serving more and more different constituencies in the larger community.”

That, right there, is the legacy we are building.

Amanda McMullen President & CEO New Bedford Whaling Museum

4

The Old Dartmouth Historical Society Finding Its Home, 1904-1916

The Masonic Building was built in 1893 and for many years housed the offices of civil engineers, insurance companies, stenographers and other professionals before the new Old Dartmouth Historical Society rented space for their meetings and exhibitions.

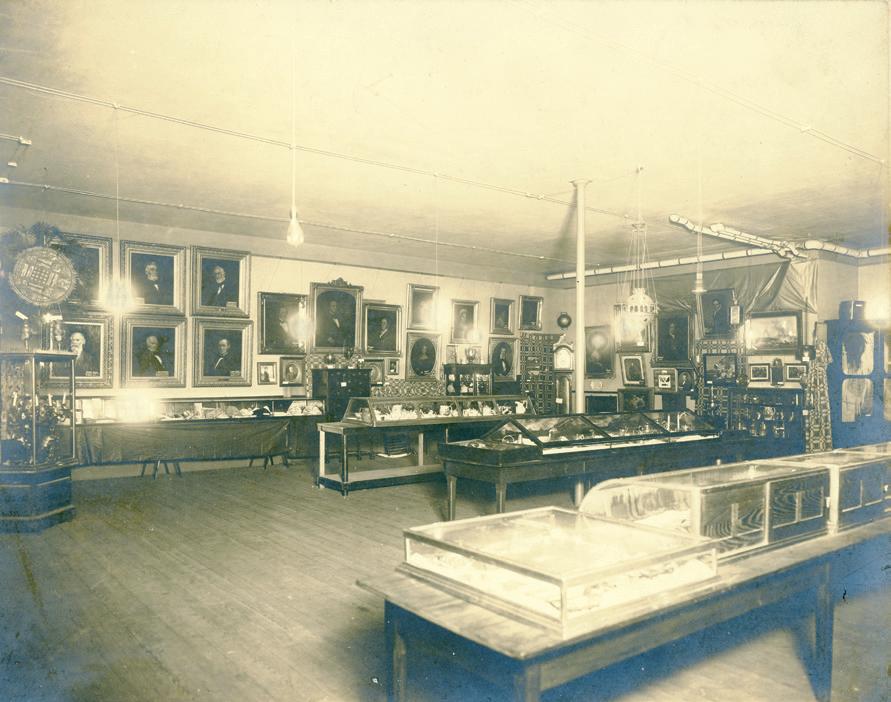

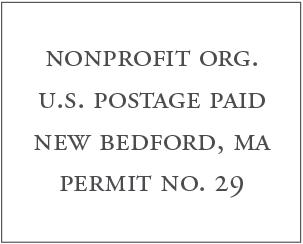

In June 1903, Abbot P. Smith (1853-1943), member of the ODHS Committee on a Temporary Museum (later Chairman of the Museum Section), reported that a room had been secured at the Masonic Building over the Ruggles and Ellison Dry Goods Store at 191 Union Street. Forty-eight men and women made up the Museum Section and “aroused an interest in the community that nothing else would have done.” The first ODHS exhibition opened in February 1904, and included portraiture, samplers, fans, decorative arts, marine ivories, objects from the Arctic and Oceania, whaling equipment, ship models, ship carvings, furniture, and curiosities. In years to come, some of the objects visible in these exhibit photographs would come into the Museum’s permanent collection.

5 | Spring/Summer 2023

Figs. 2 & 3. Joseph G. Tirrell (American, 1840-1907), Views of the first Old Dartmouth Historical Society Loan Exhibition, 1904. Mounted albumen prints. NBWM 1988.6.312; NBWM 2000.100.44

Fig. 1. Norman Fortier (American, 1919-2010), View of the Masonic Building, Corner of Union and Pleasant Streets, 1951. Image derived from an acetate negative. NBWM, 2004.11.57256.1

The 35 North Water Street building was originally built as the National Bank of Commerce in 1884. The bank moved to the Masonic Building on Pleasant and Union Streets and went into liquidation in 1898. The New England Cotton Yarn Company purchased the Water Street building in 1899, and then failed. At the urging of ODHS President William W. Crapo (1830-1926), Fairhaven oil magnate Henry Huttleston Rogers (1840-1909) bought the building and donated it to the Old Dartmouth

Society in 1906, when it became popularly known as the “Rogers Building.”

Several objects in this photograph of the ODHS exhibition space in the Rogers Building were on loan to the organization, illustrating the fledgling organization’s relationship to the community. For example, the William Bradford portrait of the ship Twilight (on wall at right) would not be accessioned into the permanent collection until decades later and the Manuel Pacheco Gamboa diorama of a sperm whaling scene (to the right of the fireplace) was acquired by the Kendall Whaling Museum in the 1960s. Captain Benjamin Cleveland acquired the two penguin specimens on a whaling voyage to Antarctica in the brig Daisy with ornithologist Robert Cushman Murphy in 1913. His wife, Emma A. Fish Cleveland donated the specimens in 1930.

Emily Howland Bourne’s (1835-1922) generous cash donation enabled the ODHS to construct a building memorializing her father, Jonathan Bourne Jr’s, success as a whaling agent. The Bourne Building, modeled on the Custom House at Salem, MA and housing a half-scale model of the whaling bark Lagoda, is an important example of purpose-built museum architecture in the early twentieth century.

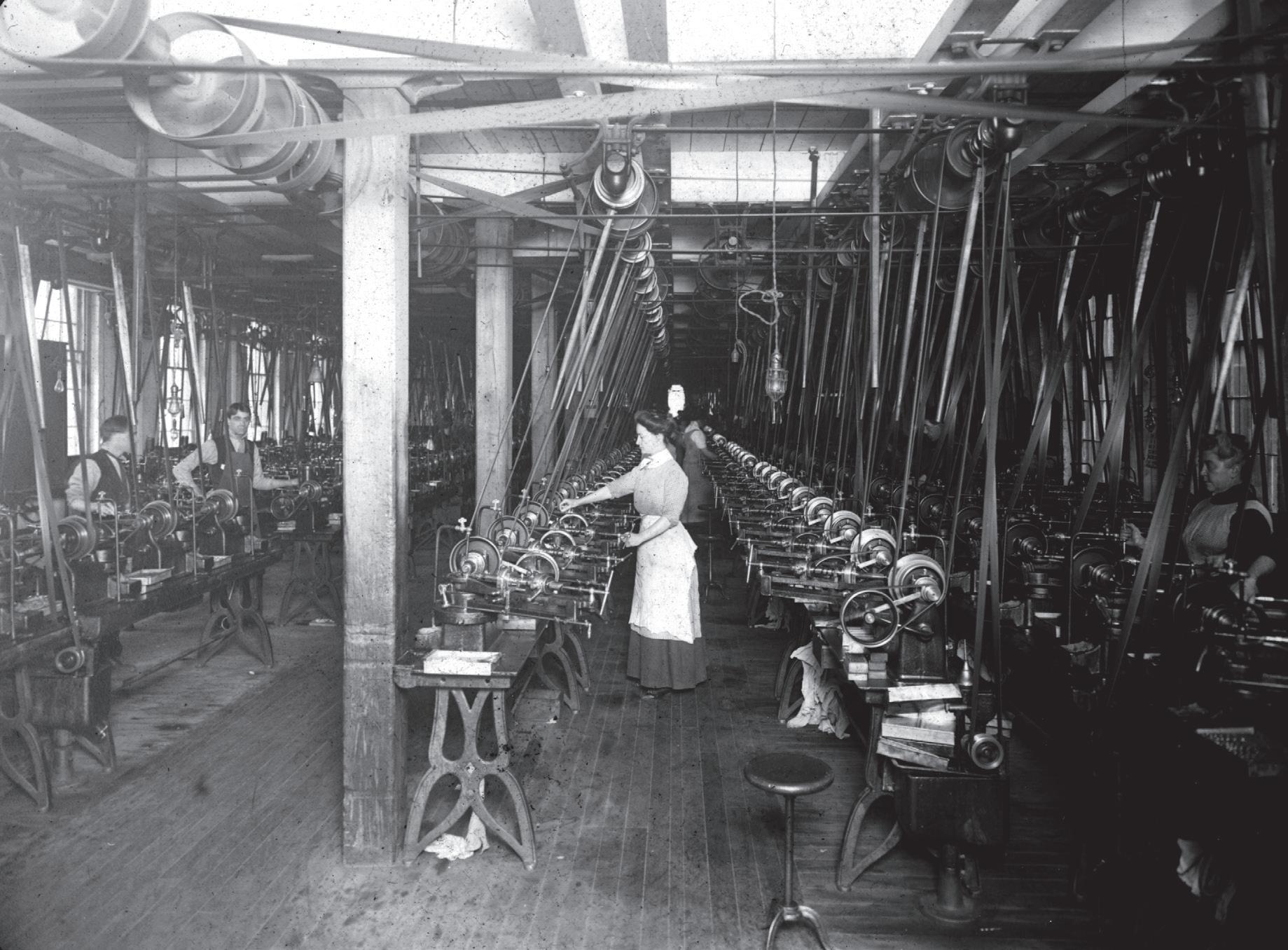

As the Bourne Building was being constructed on the other side of the block, it was business as usual along North Water Street. The ODHS sat in the middle of a busy business district. The Rogers Building housed galleries devoted to colonial history, whaling, textiles, photography, and arts of Oceania. Their neighbors included firms like Slocum & Kilburn selling mill supplies, John Cleary manufacturing cigars, and electrical contractors like Gatenby & Swift.

6

Fig. 7. Standard-Times photograph, View of the buildings along the west side of North Water Street, circa 1915. Image derived from a glass plate negative. NBWM, 1981.61.926

Fig. 6. Attributed to Joseph S. Martin (American, 1883-1947), View of the Jonathan Bourne Memorial Whaling Museum at the ODHS Under Construction, October 25, 1915. Image derived from a silver gelatin print. NBWM, 2000.100.89.3.324

Fig. 5. Joseph Sisson Martin (American, 1882-1947), Interior view of an early ODHS exhibition gallery, c. 1920. Image derived from an acetate negative. NBWM, 2000.100.85.317.

Fig. 4. Fred W. Palmer (American, fl. New Bedford, 1889-1910), View of the National Bank of Commerce Building, c. 1906. Image derived from a glass plate negative. NBWM, 2000.100.80.226.

Historical

From Sailors to Boarding House Keepers

Portuguese Mobility in New Bedford (1815-1900)

By Anne-Sophie Coudray, Ph.D, Student, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, International Research Center on Slaveries & Post-Slaveries (CIRESC)

Seaport cities and towns like New Bedford catered to a large number of itinerant seamen. Whaling merchants commonly recruited men from many American seaports and whaling masters did so as well at many ports of call around the world. Providing lodging for these men as they waited for their voyage to sail or after they had returned to New Bedford was an integral function in the workings of the seaport.

In 1856, Joseph Vera (circa 1820-1894) was one of the first Portuguese immigrants to open a boarding house in the city of New Bedford, at 113 South Water Street.1 Having emigrated a few years earlier to the United States as a sailor, Vera was among those who saw the whaling enterprise as a means of economic mobility in the United States. Born in Pico in the Azores archipelago, he joined several whaling ships

7 | Spring/Summer 2023

Feature Article

1 Managed either by Joseph or his son, Frank, this establishment would have a twenty-eight-year long tenure and become the most sustainable boarding house in New Bedford.

Fig. 1. William Allen Wall, Portraits of Joseph Vera and Anne Rose Donavan Vera, ca. 1867. Oil on canvas, NBWM 1989.48.1-2. Gift of Joseph S. Vera.

before settling permanently in New Bedford.2

Between 1857 and 1880 he invested in thirteen whaling voyages alongside individuals belonging to the political and industrial elite of New Bedford. In the time-honored tradition of this highly successful whaling port, he partnered his investments in ships with other influential merchants. During the Civil War, he diversified his activities, invested in the ownership of several whaling ships, and became a merchant clothier in addition to running his boarding house.3

In the late 1860’s, Vera abandoned the management of the boarding house and fully devoted himself to his whaling investments. In 1867, John Rose, a former sailor originally from Faial, took over the management of the boarding house.4 At the same time, he and Joseph Vera partnered in the creation of the “Vera & Close” corporation, specializing in the sale of textile products.5 Located at the same address as the boarding house, the establishment became a multipurpose place offering various services for transient and immigrant populations.

In 1869, Joseph Vera’s thirty-two-year-old son Frank took over the management of the boarding house.6 Born in 1837 in Pico, he joined his father in the United States in 1853 through whaling.7 Although it is difficult to measure how long Frank Vera had been a whaleman, it is likely that he first joined a whaling ship as a cabin boy before joining

2 Massachusetts Vital Records, 1840-1911 (Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1894), 266.

3 New Bedford whaling merchants were often ship chandlers, grocers, clothiers, or operated other businesses of direct value to whaling. These businesses not only provided cash for investment, but also served the outfitting needs of the vessels and the men who operated them.

4 The New-Bedford City Directory for 1867-68, Containing the General Directory of the Citizens city and County Register, Business Directory (Boston: Dudley & Greeough, 1867), p. 218.

5 Ibid, p. 226.

6 New England Historic Genealogical Society; Massachusetts U-S Marriages Records 1840-1915, Boston, Massachusetts; Massachusetts Vital Records, 1911–1915, 1870.

7 National Archives at Boston; Waltham, Massachusetts; ARC Title: Petitions and Records of Naturalization, 8/1845 - 12/1911; NAI Number: 3000057; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: RG 21.

subsequent voyages. In 1861, he joined the ship Majestic, Alexander Augustus Tripp, master, for a fivemonth sperm whaling voyage to the North Atlantic. Thanks to their various commercial activities, the Vera family experienced a rapid economic rise that propelled them up the social hierarchy, with their accumulation of economic capital largely due to the operation of their boarding house.

In the 1850’s, individuals of Portuguese origin were poorly represented among the community leaders of New Bedford, including the boarding house ownership. Of the seventy-three such establishments, eight were held by Azoreans and Cape Verdeans in 1859.8 While the second half of the nineteenth century heralded the gradual decline of the whaling industry, it also saw an increase in the recruitment of seafarers from the Azores and Cape Verde. They became among the most widely represented groups of crew on the whaling ships. When Joseph Vera opened the doors of his boarding house in 1856, 1600 sailors from the Portuguese Atlantic islands were recruited on board whaling boats from New Bedford, representing 12% of the crew. Between 1845 and 1920, the presence of Portuguese sailors on board whaling ships increased from 6.7% to 50%.9 Vera’s boarding house thus became a privileged accommodation for Portuguese sailors.

The increasing involvement of the Portuguese in the whaling industry coincided with a period of mass immigration to the industrial metropolises of New England. Between 1840 and 1850, more than four million European emigrants joined the east coast cities of the United States.10 The city of New Bedford saw the growth and development of commercial textile manufacturing, making it an important center of European immigration. Between 1880 and 1900, the city’s population doubled from 26,840 to

9 Russel G. Handsman, Kathryn Grover, Donald Warrin, New Bedford Communities of Whaling: People of Wampanoag African and Portuguese Island Descent, 1825-1925 (Boston, MA: National Park Service, 2021), 306.

10 Roger Daniels, Coming to America. A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life (New York: Harper Perennial, 1991), 124-125.

8

8 The New-Bedford City Directory, Containing the City Register and a General Directory of the Citizens (New Bedford, MA: Charles Taber & Co., 1859).

9 | Spring/Summer 2023

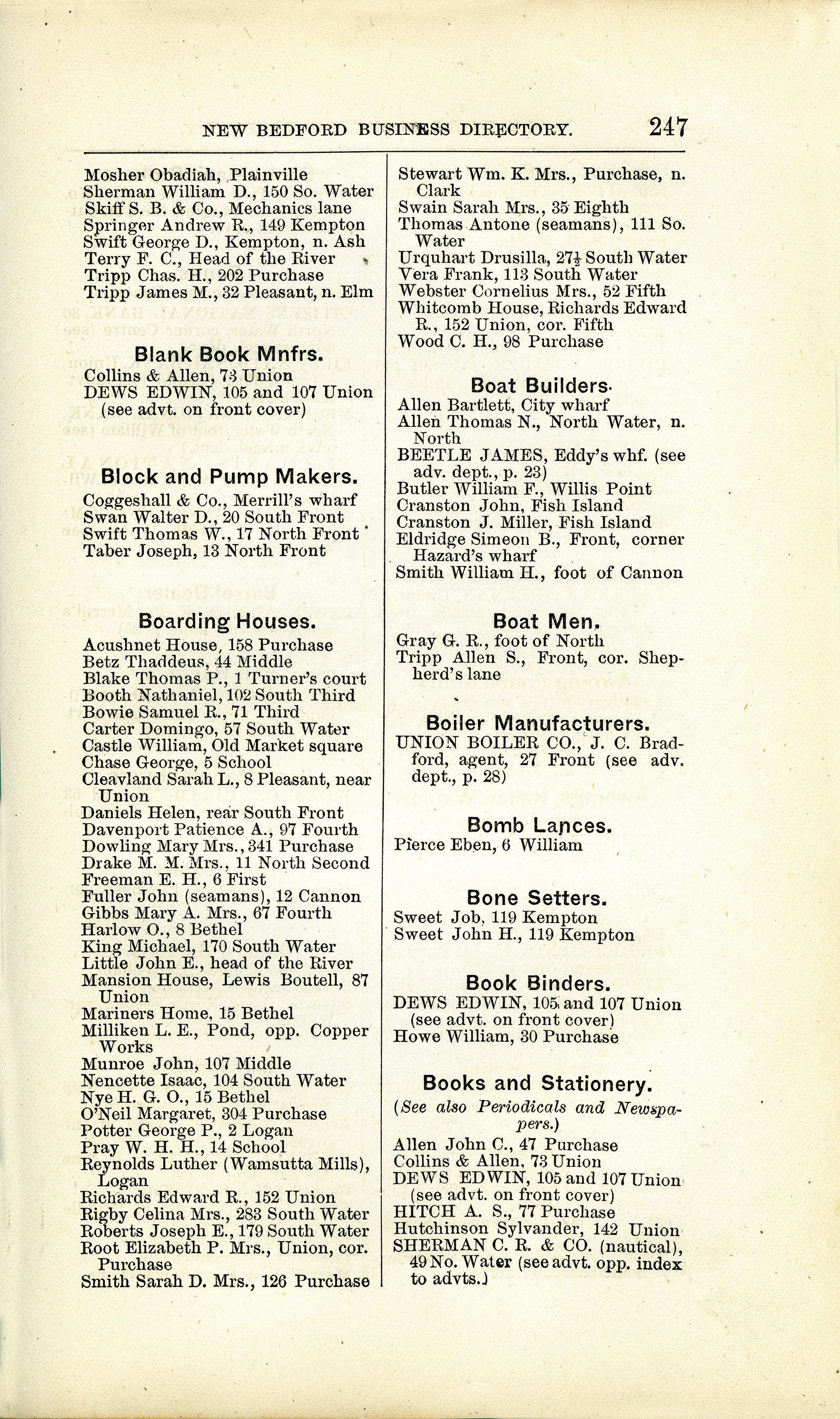

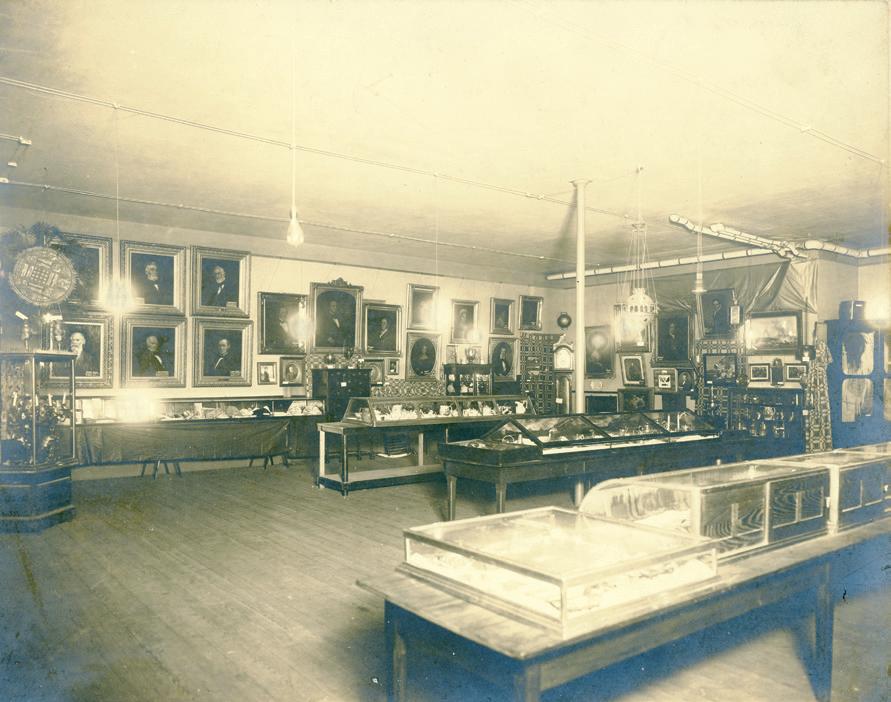

Fig. 2. List of boarding houses in 1875, New Bedford, Massachusetts, City Directory, p. 247.

62,442. Portuguese immigrants represent 14% of the immigrant population.11 In 1880, the number of Portuguese immigrants in the United States is estimated at 16,650; it reached 114,321 in 1921.12

In seaports such as Boston, New Bedford, and Providence, boarding houses became places of reception not only for sailors but also for laborers, skilled craftsmen, and employees from the new white-collar middle class.13 Throughout the century, the boarding houses catering to itinerant workers and seafarers were a recurring feature of the urban seaport landscape and a testament to the many demographic changes experienced by industrial metropolises. As a reception and place for socialization, these establishments offered services including sleeping, meals, clothing, and other necessary goods that distinguished them from mere lodging houses. The increase in Portuguese emigration through the whale fishery strongly influenced the emergence of a new group of Portuguese boarding house owners. The maritime experience of the latter was a critical attraction for individuals seeking more permanent settlement. This made some Portuguese boarding houses in New Bedford and Boston important places of recruitment of Portuguese sailors.

Over nearly three decades, the Vera family supplied many whaling ships with manpower, some recruited for their own vessels. Many investment partnerships linked them to more established shipowners making them privileged interlocutors in the search for sailors. On the strength of his economic success, in 1880 Joseph Vera became the sole owner of the schooner Lottie E. Cook of New Bedford, which made five whaling voyages until 1887. Of the eighty-five crew members who made up these voyages, fifty-six were from the Portuguese Atlantic, the majority from the Azores, Cape Verde, and to a lesser extent Lusophone Africa, including Mozambique and Angola. The

11 Christine A. Arao, and Patrick L. Elefey, Safely Moored At Last, Cultural Landscape Report For New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, Vol 1 (Boston, MA: National Park Service, 1998), 41.

12 Marylin Newitt, Emigration and the Sea, An alternative history of Portugal and the Portuguese (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015), 191.

13 Wendy Gamber, The Boardinghouse in Nineteenth-century America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), p. 3.

exceptional longevity of the Vera boarding house seems justified by their complementary commercial activities. While several of the owners of these boarding houses were former sailors, those who managed to broaden invests in the purchase of whaling vessels were a minority.

Between 1856 and 1896, only four other Portuguese boarding house keepers, Francis T. Perry (18281901), Joseph F. Lima (1835-1882), John Joseph Fernandes, and Joseph Fernandes Pinna (401 South Water St.) acquired sufficient prosperity to move towards investment in shipping after the opening of their boarding house.14 Both Pinna and Fernandes invested in packet schooners although their investments were short-lived. Fernandes bought the schooner Irving of New Bedford which was wrecked off Nantucket in 1875 en route to Cape Verde with passengers and a cargo of goats and whale oil. Pinna invested in one voyage of the schooner Sarah E. Lee of New Bedford in 1906. Like the Vera family, these individuals also owned clothing stores for sailors. In 1872, for instance, former sailors Francis T. Perry and Joseph F. Lima shared ownership of the brig George J. Jones of Fairhaven, with other investors.15 The similar trajectories of these Portuguese sailors who were boarding house keepers, merchants, and shipowners illustrate how whaling was a pathway to economic flexibility for some sailors.

Perry was originally from the Azores and opened a clothing store in 1859 at 89 South Water Street in New Bedford; this address became a boarding house in 1865.16 He subsequently sold his businesses to Joseph Fernandes Lima (1829-1882), who became the new owner in 1877.17 Between 1878 and 1881, Lima invested 4/52 shares in the schooner Surprise

14 Late nineteenth century immigrants’ names often appear in their anglicized forms in New Bedford records like the City Directories

15 Ship Registers of New Bedford, Massachusetts Compiled from original documents stored in the New Bedford Custom House, Volume III 1866-1939 (Boston: National Archives Project 1940), p. 68.

16 The New-Bedford City Directory, Containing the City Register and a General Directory of the Citizens (New Bedford, MA: Charles Taber & Co., 1859), p. 140.

17 The New-Bedford City Directory, Inhabitants, Institutions, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Societies, Business Firms, etc, in the City of New Bedford for 1877-1878 (Boston: W.A. Greenough & Co., 1877), p. 277.

10

of New Bedford, alongside several city craftsmen, including coopers, a physician, another boarding house manager, a pump and block maker, and other skilled laborers.18 The management of the schooner Surprise stands as a prime example of whaling as a means toward community investment and upward economic mobility. For each of the vessel’s five voyages under this disparate group of investors, Portuguese seamen represented most of the crew members. They were likely recruited through the local complex of boarding houses.

In the 1880’s, merchants encountered many difficulties recruiting maritime labor in New Bedford. Some used coercive methods, called crimping or shanghaiing, to recruit sailors. In 1881, a report prepared by the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries mentions the major role New Bedford clothing merchants, outfitters, and boarding house owners played in sailor’s recruitment:

The crews at New-Bedford are generally furnished by a class of merchants known as “outfitters” assisted by boarding house keepers. [….] Both of these classes are known locally as “sharks”. When the Agent of a ship wants a crew, he notifies the outfitter who draw upon “the shipping master” in New York, Boston or the boarding house keepers in New Bedford for the number of men required.19

Howland Street in New Bedford. In 1890, John Wing, part-owner with his brother William of the merchant tailor firm J. & W R Wing & Co., along with Justino A. Ferreira, supported Antonio Tavares de Pinna’s request for access to naturalization as witnesses.20 A year after obtaining his US citizenship, the latter opened his own boarding house located at 8 Walnut Street in New Bedford.21

After 1850, boarding houses became important channels of migration. Alongside ship owners and sailors, boarding house owners from the first wave of emigration encouraged the naturalization of other Portuguese boarding house keepers and sailors. In 1862, Joseph F. Lima obtained American naturalization thanks to the support of Francis T. Perry and Francis Lewis, a shoe merchant.22 On November 15, 1880, Frank Vera obtained American naturalization thanks to the support of two Boston boarding house keepers, Joseph J. Alves and Antonio J. Avellar, who were both actively involved in naturalization procedures of Portuguese sailors and boarding house keepers. The same day, he supported the request for naturalization of a Portuguese sailor named John Oliver Perry, alongside another Boston boarding house keeper named Antonio Enos.23 These initiatives all suggest a national solidarity, revealing above all some common interests for the exchange of maritime labors. At the end of the 1800s, the boarding house keepers of New Bedford forged real commercial links for the recruitment of labor and the realization of economic benefit.24

20 National Archives at Boston; Waltham, Massachusetts, Copies of Petitions and Naturalizations in New England Courts, 1787-1906, Bristol County, Third District Court, New Bedford, Ma, Vol· 1885 to 1896, Pg 805-1453 B, Ca· 1787-1906.

21 The New-Bedford City Directory, Inhabitants, Institutions, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Societies, Business Firms, etc, in the City of New Bedford (Boston: W.A. Greenough & Co.,, 1891), p. 390.

at 47

While the involvement of boarding house keepers in the exploitation of an immigrant workforce cannot be affirmed, their presence as witnesses alongside shipowners in the individual acts of naturalization of seamen and other Portuguese immigrants demonstrate a clear alliance in the recruitment of sailors. In 1890, Antonio Tavares de Pinna obtained US Citizenship. Born in 1859 in Brava, he emigrated to the United States in 1874 as a whaleman. Between 1874 and 1890, he made four whaling voyages, while living intermittently in the boarding house of Justino A. Ferreira

18 Ship Registers of New Bedford, Massachusetts Compiled from original documents stored in the New Bedford Custom House, Volume III 1866-1939, (Boston, The National Archives Project, Work Projects Administration, 1940), p. 163.

19 George Brown Goode, United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries, The Fisheries and the Fishery Industries of the United States, Section V, History and Methods of the Fisheries …, Volume II (Washington: Government Printing Office 1887), p. 224.

22 The New-Bedford City Directory, Inhabitants, Institutions, Manufacturing Establishments, Business, Societies, Business Firms, etc, in the City of New Bedford (New Bedford, 1867), p. 219.

23 National Archives at Boston; Waltham, Massachusetts; ARC Title: Petitions and Records of Naturalization, 8/1845 - 12/1911; NAI Number: 3000057; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: RG 21.

24 Bureau of the Navigation, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Navigation to the Secretary of the Treasury (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1898), p. 198.

11 | Spring/Summer 2023

In 1883, the Vera boarding house and clothing business closed. Frank Vera Jr. (1874-1959) chose quite a different career path from his father, becoming a lawyer.25 Thanks to the economic prosperity and strong community engagement created by his family through the whaling era, he was integrated in the professional life of New Bedford. While he became justice of the peace in 1900, he nevertheless continued to maintain close ties with Portuguese sailors and

25 United States federal Census, Massachusetts, Bristol, New Bedford Ward 05, District 0194, Massachusetts; Roll: 637; Page: 13; Enumeration District: 0194; FHL microfilm: 1240638, 1900.

boarding house keepers, validating naturalization requests into the 1950s.

12

Fig. 3. Joseph G. Tirrell, Boarding houses on the east side of Bethel Street looking north from Union St., New Bedford, circa 1900. Silver gelatin print, NBWM 2000.100.89.1.1.26.

Documenting a Fred Harvie Miniature Model House

By Dave and Marilyn Ferkinhoff, New Bedford Whaling Museum Volunteers

We’ve recently had the opportunity to restore a rather spectacular model house donated to the NBWM in 2021. The model is based upon an old New Bedford house originally built in 1876 at 227 Arnold St. which still stands today.1 The donor, Mary Edwards, is the niece of George and Katherine Castino, the former owners of the house. Ms. Edwards commissioned famed miniaturist Fred Albert Harvie (1929-2005) to build it, stating that she had “fond memories of it” growing up. Harvie was originally a carpenter and house builder in Hingham, MA, but in 1975 he and his wife Jean opened “Fred’s Dollhouse and Miniature 1 Zillow search, https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/227-Arnold-StNew-Bedford-MA-02740/55996079_zpid/

Center” in Pittsford, VT, where they specialized in miniatures. The Arnold Street House is a superb example of their work. The model is mounted on a custom-built cherry wood chest of drawers that stores many extra objects and other accoutrements, some of which are listed later in this article.2

We consider it a model versus a dollhouse, which warrants an explanation of the difference between a

2 An excerpt of the database description reads: “Custom built highly detailed modeled house of the New Bedford home of George F. Castino and Katherine MacDonald Castino, built by Fred Harvie, ca. 1985. George was grandson of Capt. John A. Castino (18301910) and Etherlinda Gage Baker (1836-1917). John A. Castino commanded three whaling voyages onboard the ships Congress and Governor Troup between 1859-1872.”

13 | Spring/Summer 2023

Fig 1. Front view of the Fred Harvie model of the house at 227 Arnold St., New Bedford. NBWM 2021.30. Gift of Mary Edwards.

miniature, a model, and a dollhouse. A miniature is any object representing a normal object but scaled down. Many examples of miniatures can be seen in this Harvie model including paintings, furniture, books, kitchen utensils, etc. Conversely, a dollhouse is generally modeled after a particular style, but the finishing and interior architecture can be radically different from any real house in order to facilitate play. For this reason, dollhouse rooms generally go either all the way or half way from the front to the back. Dollhouses come in five popular scales. Play scale (think “Barbie”) is 2 inches to the foot (2:12). Most miniaturists collect 1 inch, ½ inch, or ¼ inch. Lately, 1/144th scales have become popular.

A model on the other hand tries to duplicate the architectural and decorative styles of an object. A model of a house would include interior hallways, paint colors, etc. Sometimes, as in the case of this Arnold Street house, even the furnishings are recreated. Actually, it would not be inappropriate to call a house model a dollhouse, as the term dollhouse has become somewhat generic, and in truth most models could be played with as a dollhouse. So, a model and a dollhouse can both be considered miniatures, but a dollhouse is not necessarily a model – although it can be. A central hallway points to this being a replica model of the real house instead of a simple dollhouse.

This 1:12 scale house consists of 16 rooms including:

• Front: a front porch, living room, half bath and dining room downstairs; 2 bedrooms upstairs and an attic on top.

• Side: a side porch and kitchen downstairs and an attic.

• Rear: a pantry, bathroom and study downstairs; a bedroom and a bathroom upstairs.

• A central hallway with stairs.

As model houses go this is a larger one in terms of the number of rooms, and while its overall size is impressive it’s not an excessively large model. The construction and finishing are extremely well done, although many of the artworks and furnishings are fanciful additions not meant to represent actual pieces either owned by the family or in their possession in the house.

In early October of 2021 a curatorial team went to the donor’s home, took pictures of all the rooms in the dollhouse on site, then packed up the objects for transportation to the museum. As volunteers, Marilyn and I worked diligently to clean, repair and catalog each of the small items on days when we were not busy giving highlight tours or walking the halls on busy days as docents.

A general cleaning was very important. The true beauty of the house was hidden under a layer of dust. In fact, the dust was so evenly distributed and so well

14

Fig 2. View of a nineteenth-century dollhouse. Note the limited number of rooms and their large size, twice as large as the Harvie model. The wallpaper appears to date from the late nineteenth century. NBWM, 00.49.32

stuck down to the rough roofing asphalt shingles, that everyone originally thought the shingles were grey. A good vacuuming with a special miniature brush cleaned them up so their true color could shine.

We then used the photos taken at the time of acquisition to identify where each of the items originally came from and reconfigured the rooms and their contents, as they had been at the donor’s home. Many of the small items incorporated into the room arrangements, as well as the extra pieces, are of the highest quality and most are still in superb condition. During the cataloging process repairs were done to some damaged items and the house itself. For example, we glued things like doorknobs back on, and repaired bed frames and the wind vane. The house is electrified with tape wiring, so all the lamps were checked one by one to ensure both they and all the plug sockets are operable.

Finally, we are photographing groups of items from each room for inclusion in the museum’s collection database. With these photographs, their placement can easily be determined in the future. This step makes it easier to redecorate if the items are ever removed for long term storage, or if future generations want to put it back as it was. Extra objects are photographed as a group of like objects, e.g., Christmas items, kitchen utensils, pantry items, etc.

A Description of the Downstairs Rooms

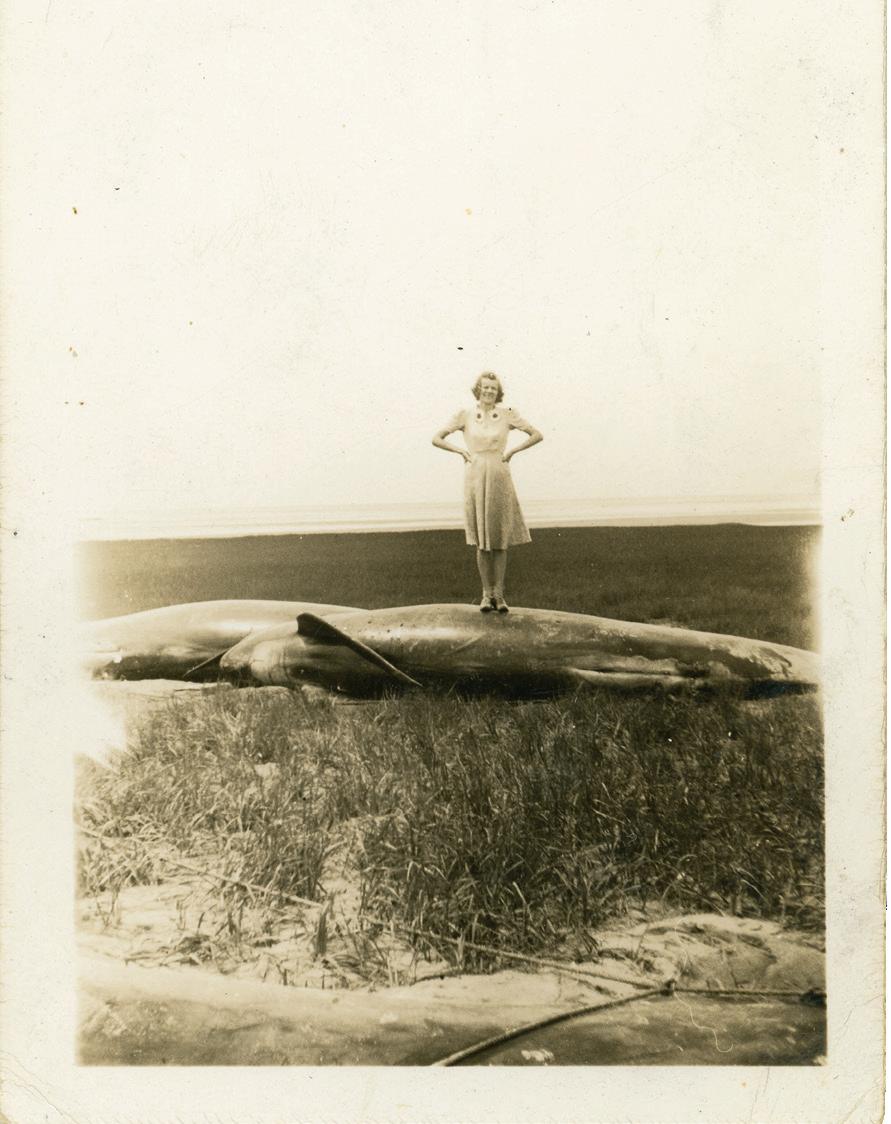

The grandfather clock in the sitting room has exquisite inlay in the body, a William Bradford reproduction painting hangs on the wall, fine quality rugs adorn the floors, and working floor lamps give the room light and warmth.

The pink dining room with matching drapes contains a fully stocked bar, cherry furnishings, and a working chandelier. High quality plates adorn the plate racks along the top of the walls. A silver punch bowl, coffee and tea set, and candelabras sit waiting on the sideboard. With the side table in back closed up to hold a silver and glass lamp it looks like the missing residents are preparing for a party.

Several of the more interesting items are displayed in the study. They include a whale cribbage board,

telescope, inlayed cabinet, sextant in a case, sailing ship model, and other knickknacks. Each of the items mentioned are of superb quality, as are the remaining furnishings in the room.

The pantry has the most items, and as such will be the most difficult to catalog. It is fully stocked with dry goods of all sorts, including a case of Coca Cola, a box of oatmeal, bag of sugar, fresh veggies just in from the garden, as well as jars of preserves on the shelves. Dishes are stored in the cupboard on the other side of the shelves. Other adornments include a water cooler, jug, cleaning supplies, and even a mouse trap.

The kitchen is very well done and includes a white porcelain stove, sink, marble table and chairs, braided rug, muffins, and everything needed to fix a scrumptious meal.

A Description of the Upstairs Rooms

The two front bedrooms appear to be decorated as adult’s rooms. Working lamps are used to bring light to these rooms that would otherwise be in shadow. The cherry furnishings, glass lamps, porcelain bowl, and fabrics are extremely well made. Pictures of nuns and someone in uniform adorn the walls. A painted chest and screen, and even shoes bring the sense of a space being lived in.

The back bedroom is the kid’s room. One of the lights in the room is a working whimsical lamp and serves its purpose. A rocking chair, bed, shelves with books, and toys decorate the room. The dolls, games, and toy soldier bring back memories of a child’s fantasy world.

The half bath downstairs contains a painted porcelain toilet with matching sink and mirror. A simple light lends elegance to the room with its painted decorations. The open white wicker shelving rounds out the room making it look larger than it is.

The upstairs full bath has gold plumbing on white porcelain fixtures. The same central light as the room below adorns the ceiling and ties the two bathrooms together. A robe hanging on the back of the door and slippers by the tub make one wonder who will come through the door next. Maybe you surprised someone and they had to run out of the room in a hurry!

15 | Spring/Summer 2023

The attics are a jumble of items like you would find in any attic, well any attic of a whaling captain. If you’re not careful you might even stub your toe (well, finger) on a case of harpoons stored up there.

There are several drawers in the cabinet with additional items. They include tools and supplies for working on the house, new plants, holiday decorations, and odds and ends that were swapped out during the change of seasons.

Future Exhibition Possibilities and Concerns

This model house presents some challenges as far as exhibition is concerned. The hundreds of little

bits that populate the rooms are fragile in their arrangements. This model would not make a suitable interactive experience on its own. Sitting as it does on a custom chest of drawers the entire ensemble is a work of art and would need to be both protected in its entirety as well as being seen that way. Two of the walls of the house itself can be opened allowing the interiors to be examined in detail. However, having the walls open increases the footprint of the model as well as stressing the wall hinges as they are open. These walls are not designed to remain open for long. Perhaps one day a suitable case will be constructed that allows for this splendid example of the miniaturist’s art to be publicly enjoyed.

16

Fig 3. Interior view of the sitting room of the Fred Harvie model of 227 Arnold St., New Bedford, MA. NBWM 2021.30. Gift of Mary Edwards.

Comets, Meteors, and UFOs in Nineteenth-Century Skies

By Mark D. Procknik, Librarian

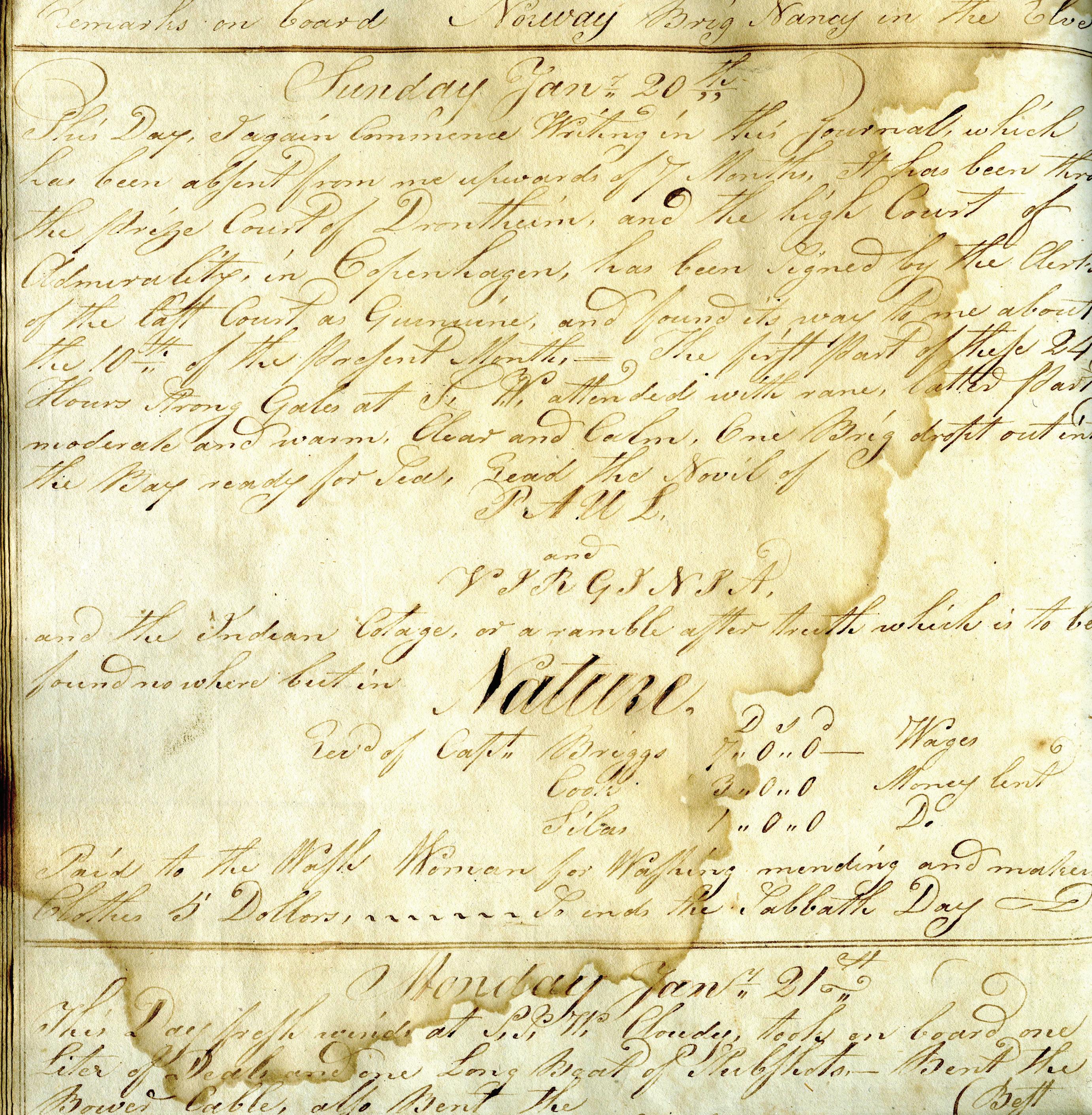

In June 2021, the United States Office of the Director of National Intelligence issued a Preliminary Assessment on Unidentified Aerial Phenomena.1 For the first time, an official statement was shared with the public on a subject that captivated the popular imagination for generations. From an archivist’s viewpoint, this report begs the question of whether the experience of such phenomena has an historical record, and if so, could it be gleaned from the deep resources of an archive devoted to preserving the day-to-day observations of thousands 1 https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/PrelimaryAssessment-UAP-20210625.pdf

of American mariners? The logbook and journal collection of the New Bedford Whaling Museum seemed an ideal place to search.

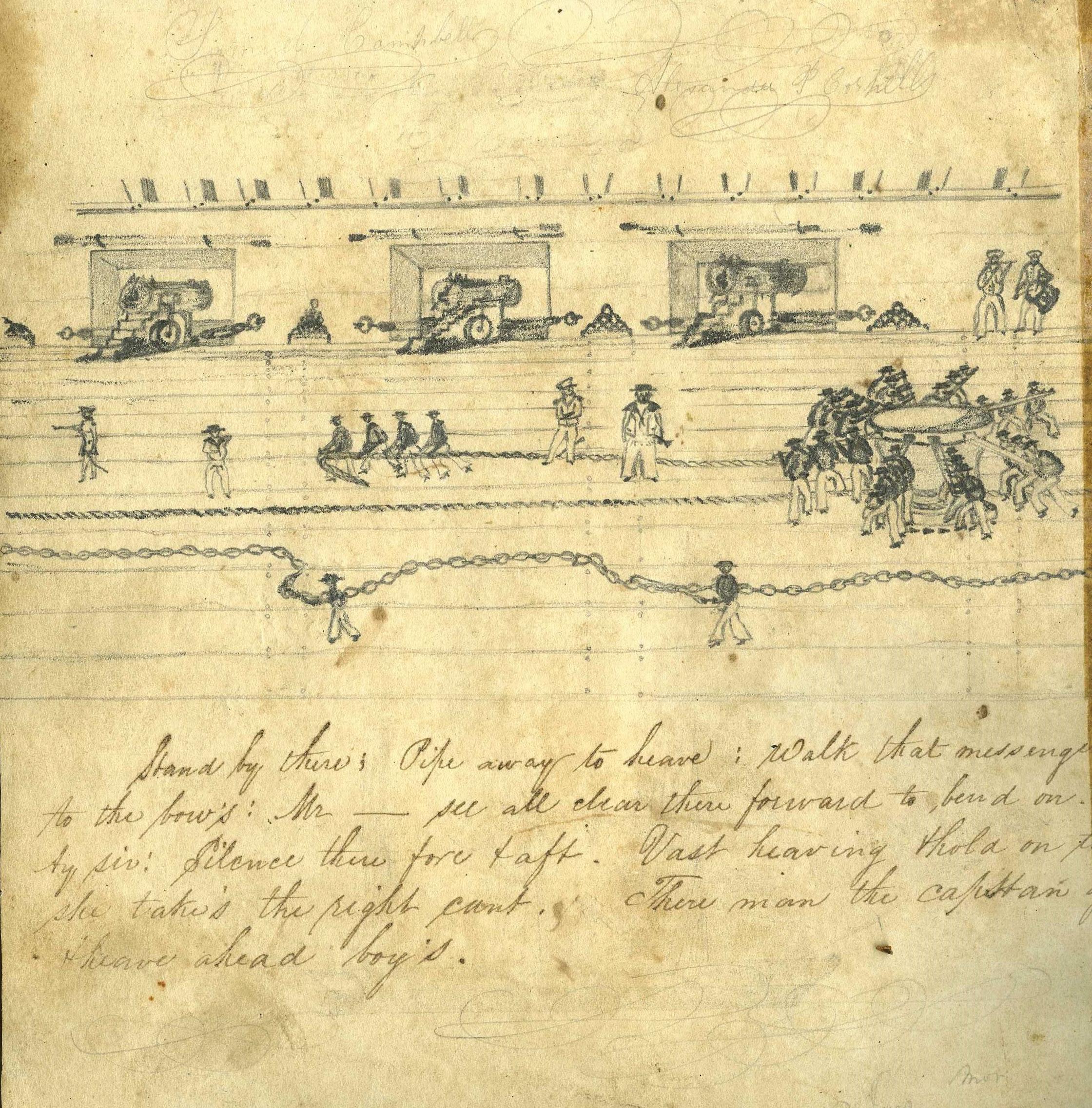

Countless pieces of whalemen’s artwork depict anatomically correct sea mammals, accurate whaling scenes, intricate ship portraits, and precise representations of foreign ports. The keepers of whaling logbooks and journals often recounted their experiences at sea in great detail. Whalers were constantly immersed in the natural world for years at a time, so it is no surprise that some were keen observers and accurate reporters of their experiences.

17 | Spring/Summer 2023

Book Talk

Fig. 1. John F. Martin, “Great Comet,” c. 1843. NBWM, KWM 434. Martin drew this picture in his journal kept onboard the ship Lucy Ann of Wilmington, DE, in March 1843.

They were also no strangers to the night skies, as a correct observation of the stars was fundamental to navigation. Captains and officers regularly turned their gaze towards the heavens, and logbooks and journals sometimes record unusual occurrences in the night sky. Examples include comets, meteors, lunar eclipses, planetary movement, and shooting stars. As a result, the Museum’s logbook and journal collection offers a unique repository of nineteenth-century celestial observations ranging from historically renowned comets to unidentified objects that seemingly defy explanation.

For over 150 years, the Great Comet of 1843 held the distinction of the longest known cometary tail and is one of history’s most well-documented nineteenth-century comet sightings. Due to its brightness and the length of its tail, many written and pictorial accounts exist, including sightings in China describing it as “broom-star,” the Australian Anglican Bishop, William Grant Broughton (1788 -1853), describing it as a “remarkable spectacle,” and additional accounts noting that the comet’s dramatic appearance “produced great alarm” and caused “widespread panic.” Charles W. Austin of the ship Charles Phelps of Stonington, Connecticut, for instance, recorded a sighting of the comet in his entry for March 5, 1843 (ODHS 899), while cruising in the South Pacific Ocean. Austin wrote that the comet’s tail “came down to the horizon and extended far into the Heavens in such a way all of the men said that they never saw before.” Comet sightings were nothing unusual for whalers, but the brightness, magnitude, and length of this particular comet no doubt presented whalers onboard the Charles Phelps with a unique view to a comet that according to modern astronomers will not reappear in the Earth’s skies until at least the year 2443 due to its 600 to 800-year orbital period.

Some whalers, not content to simply write about celestial bodies, also illustrated what they witnessed. While onboard the ship Lucy Ann of Wilmington, Delaware, in 1843 (KWM 434), John Martin wrote of the same comet Austin encountered onboard the Charles Phelps and described its tail stretching “from the horizon to almost directly overhead.” A gifted artist whose journal includes several brilliant watercolors of

whales, whaling scenes, wildlife, and distant shores, Martin not only included multiple entries about the comet in March 1843, but included two watercolor illustrations showing the comet and its historic tail. In the absence of photography, Martin’s journal illustrations, along with nineteenth-century paintings by Australian artist Mary Morton Allport (18061895) and Scottish astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819-1900), endure as visual representations of the comet and provide valuable historical documentation for modern day astronomers.

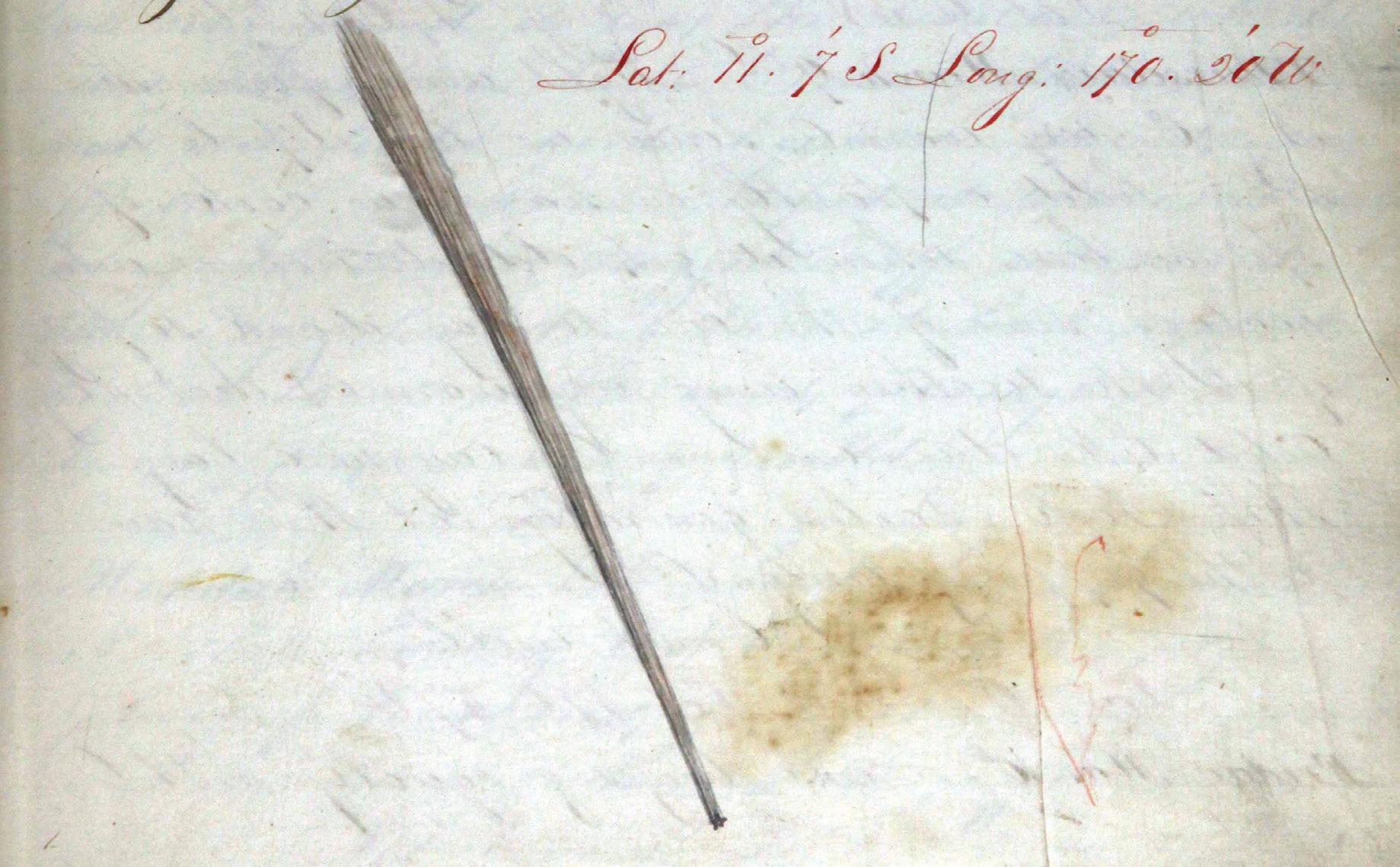

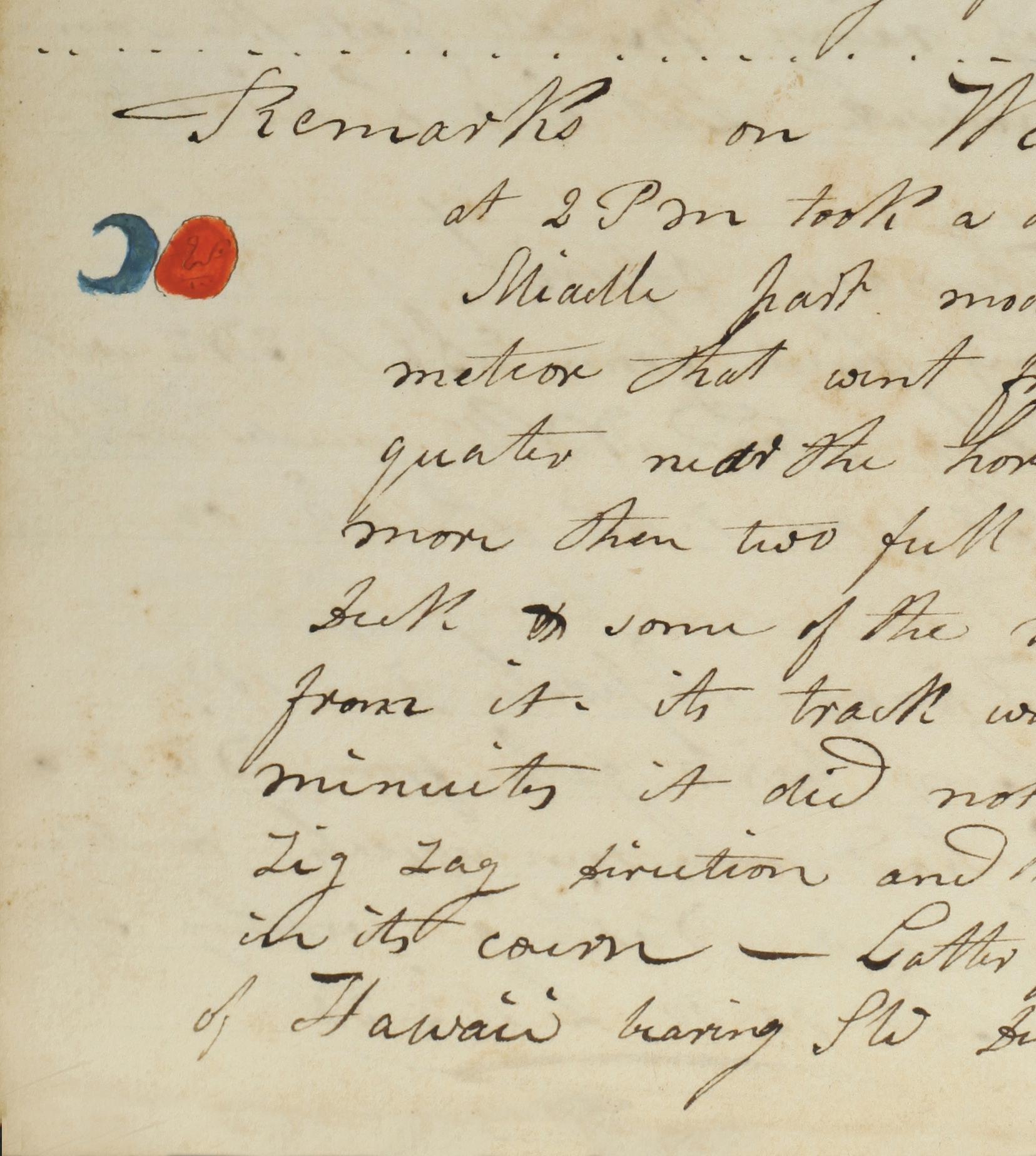

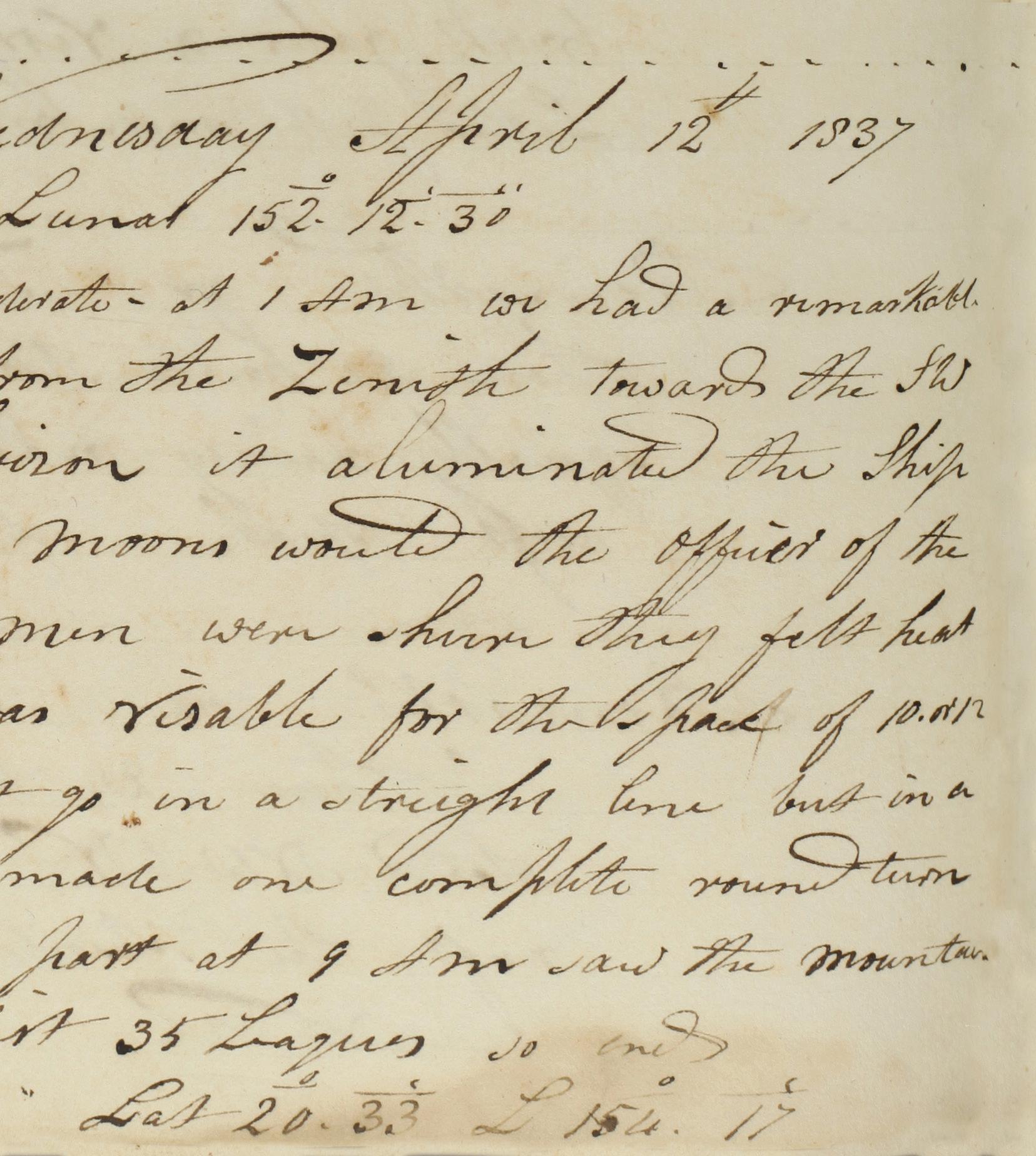

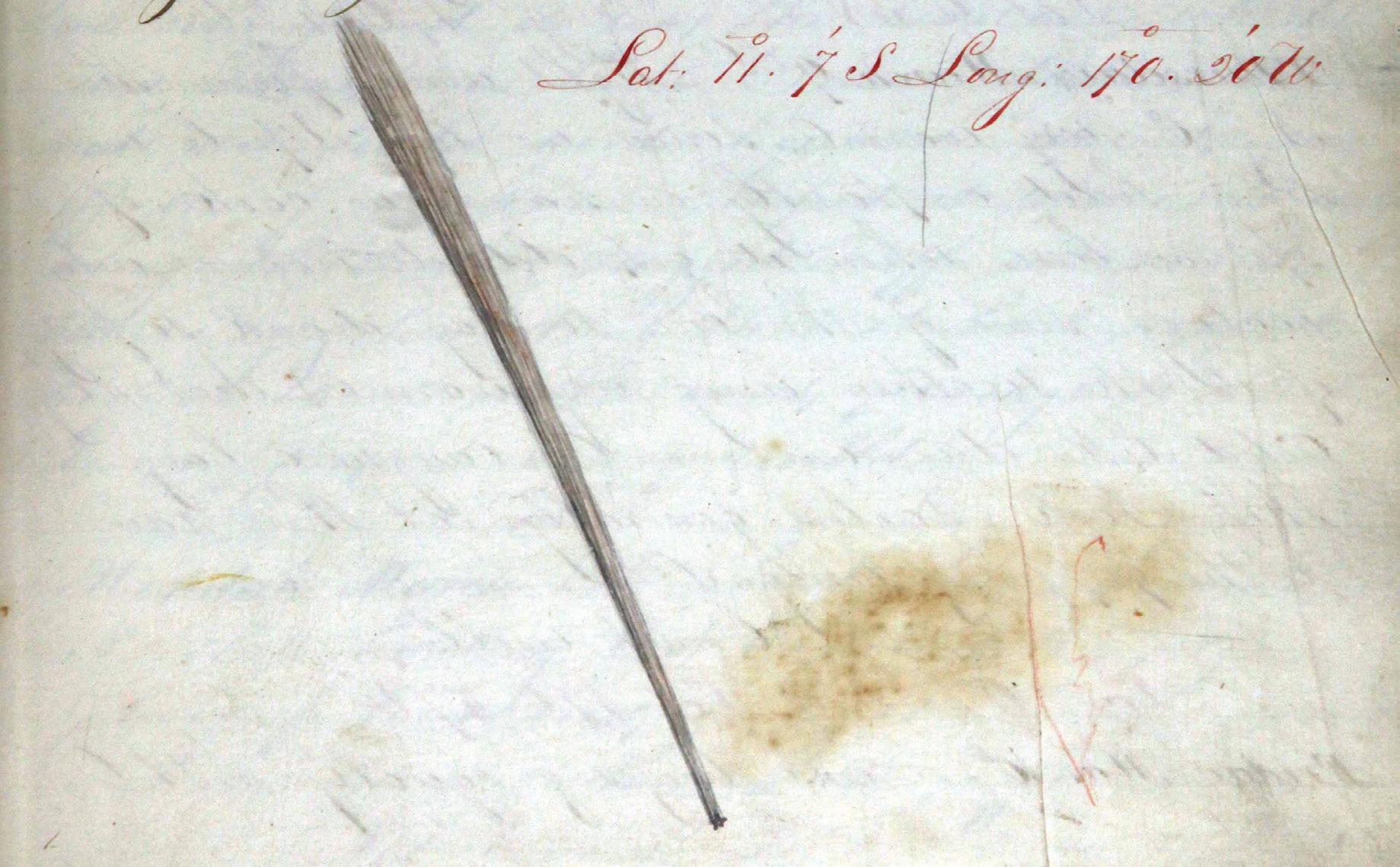

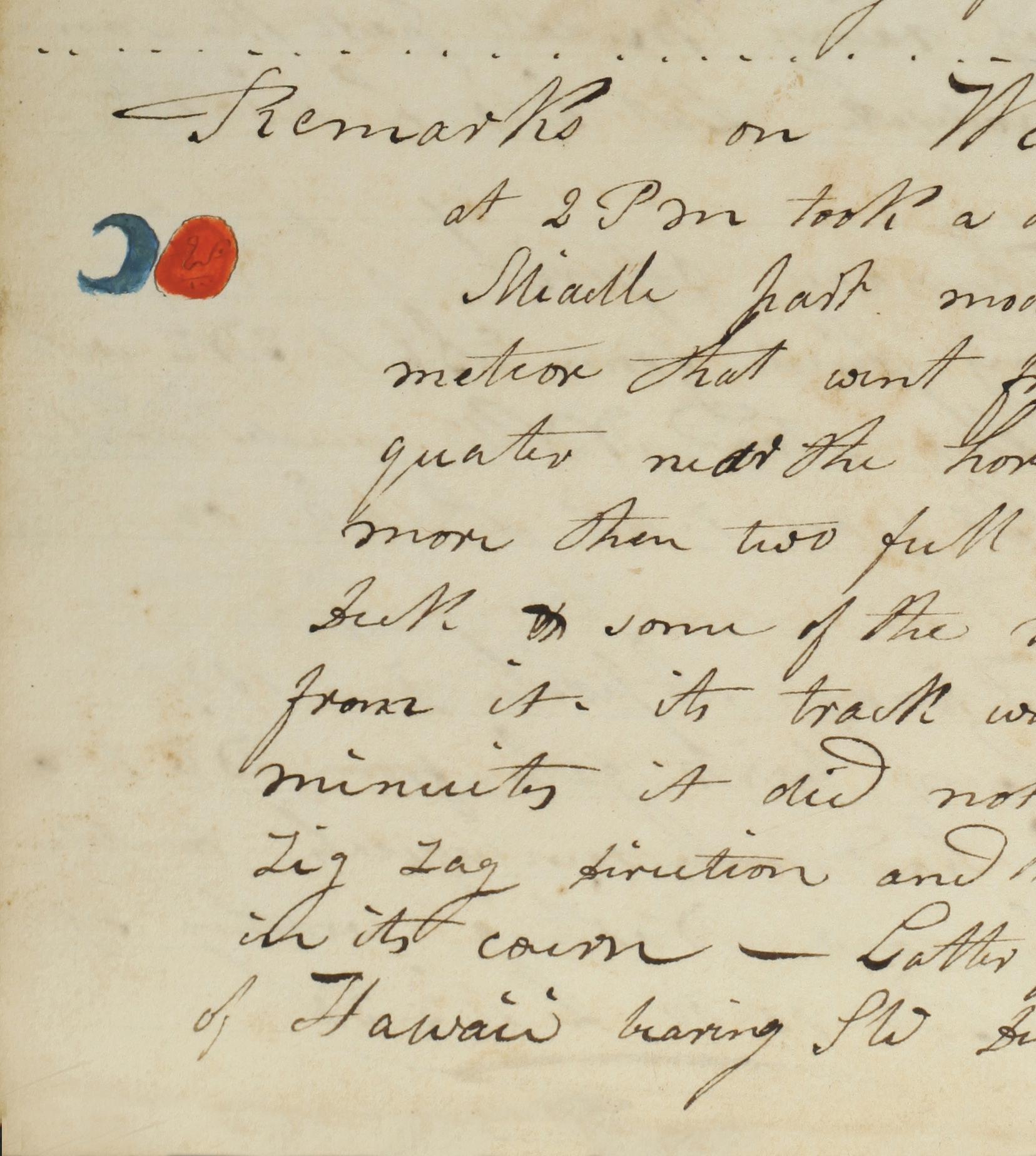

History’s notable comets were not the only illuminated objects that captured the minds and attention of whalers. Logbooks and journals document predictable phenomena such as meteors, shooting stars, eclipses, and planets. However, at least one whaleman’s observation describes an object that defies astronomical explanation. Robert Joy, captain of the ship Roman’s 1835 to 1839 voyage out of New Bedford (NBW 1378), pens one of the most notable period celestial sightings in the entire collection. Cruising in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii on April 12, 1837, Captain Joy observes a “remarkable meteor” visible in the night sky for ten to twelve minutes. Joy describes the object as very bright, noting that it “illuminated the ship more than two full moons would” and writes that some of the men and officers on duty could feel heat emanating from the object. What makes Joy’s account so remarkable is that this meteor does not move in a straight line like a meteor would or should. According to Captain Joy, this meteor witnessed by his entire crew “zig-zagged” through the night sky and “made one complete round turn in its course.” This is obviously atypical behavior for natural objects like meteors or meteoroids, commonly called “shooting stars,” that have entered the Earth’s atmosphere moving in a straight-line trajectory.

What was it, then, that Captain Joy reported and what his crew witnessed? With little apart from Joy’s observations to analyze, it sounds like neither a meteor nor any other object intrinsic in nature. Captain Joy only described it as “a remarkable meteor” as that was the best he could do given his (granted great) knowledge of naturally occurring celestial objects. Whalers would often observe something unusual in

18

19 | Spring/Summer 2023

Fig. 2. Section of text dated Wednesday, April 12, 1837 from Captain Robert Joy’s journal kept onboard the ship Roman of New Bedford, MA, 1835-1839 on a sperm whaling cruise to the Pacific Ocean. NBWM, NBW 1378.

the sky and frame their descriptions in terms they were familiar with and understood. This would occasionally result in descriptions of a “fiery meteor lighting up the night as if it were midday,” a “blazing planet,” or a “blazing star” that “hovered” in the sky. The “remarkable meteor” that zig-zagged, turned, and maneuvered its way through the Pacific skies in

1837 will likely remain unidentified, forever marking this April 1837 entry as a whaling captain’s credible account of a nineteenth-century unidentified flying object.

20

Sharing Our Local History

A Metaphor in Dartmouth: DHAS

and its Quaker Transcription Project

By Sally Aldrich, Robert J. Barboza, Richard W. Gifford, Robert E. Harding, Andrea Marcovici, and Marian Ryall of the Dartmouth Historical and Arts Society, Inc.

“The absolute truth is that happiness really comes from within, when we can be content with what we have and are doing in the present.”

Dan Socha, The Seeker and the Owl: Of Truth and Wisdom (Kindle edition, 2018).

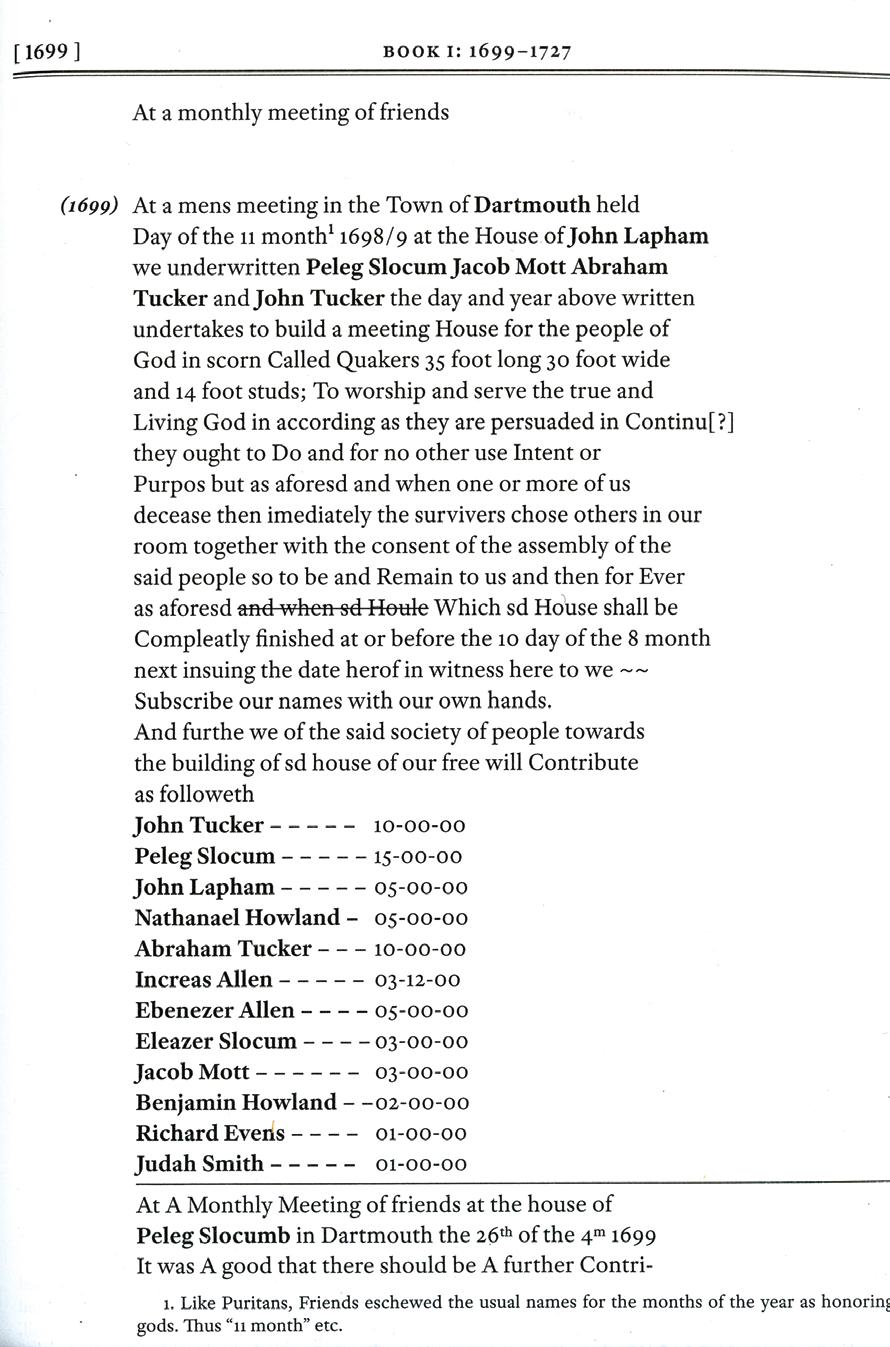

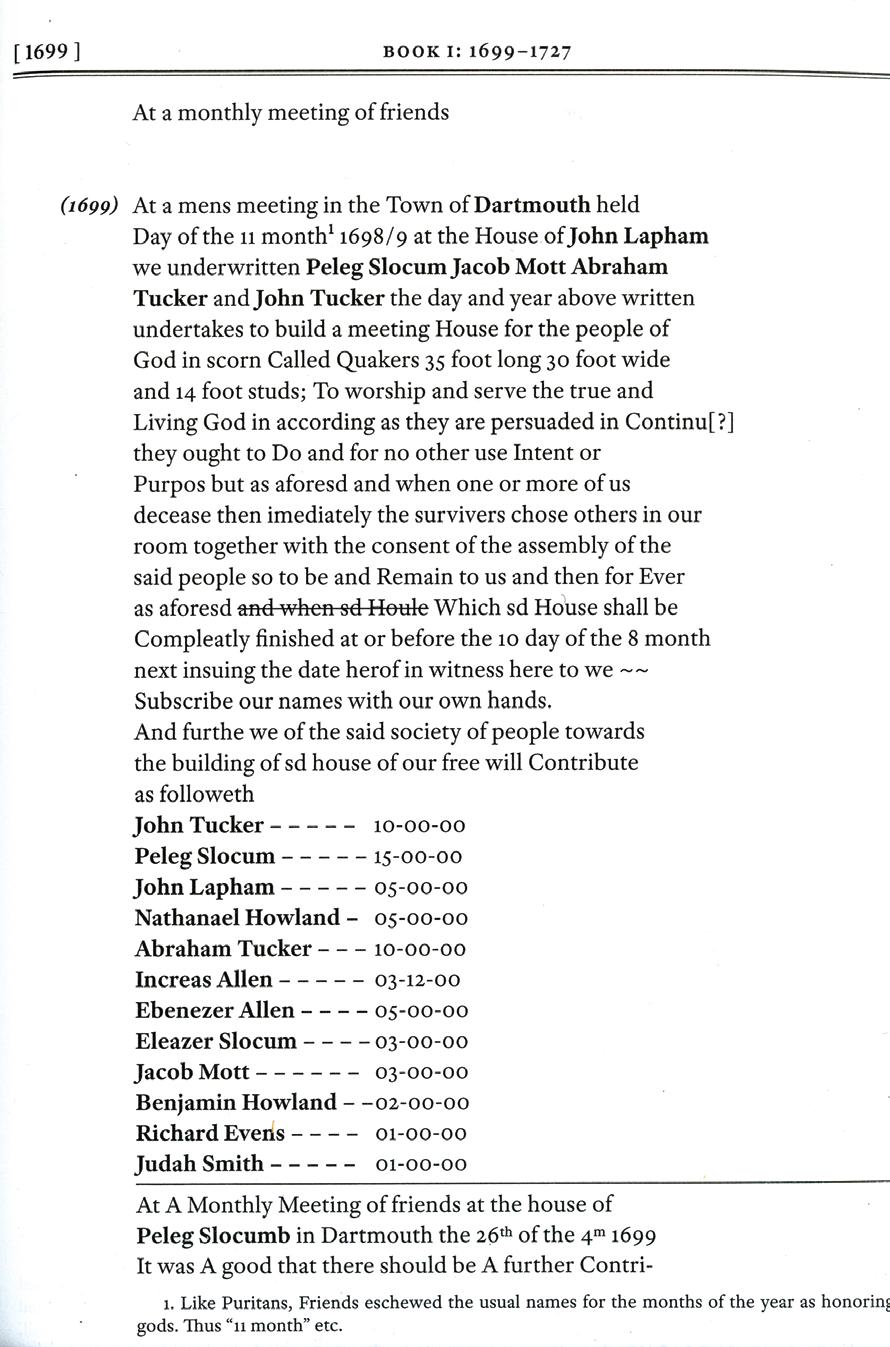

Tales of Mighty Mouse, an “ordinary mouse with extraordinary powers,” emerge metaphorically as the Dartmouth Historical and Arts Society, Inc., known locally as “DHAS,” steps into the publishing realm of serious scholarship as a partner with the Colonial Society of Massachusetts in the new two-volume set The Minutes of the Dartmouth Monthly Meeting of Friends, 1699-1785, Thomas D. Hamm, ed., Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Vol. XCVIII (Boston, 2022).

Noted historian John W. Tyler, long term Editor of Publications for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, worked with DHAS on their recent publication of the Quaker records of Dartmouth and commented in a recent issue of the CSM Newsletter that “These volumes are a cooperative venture with the Dartmouth Historical and Arts Society, an extremely ambitious and active local historical organization.”1 Founded in 2011, the DHAS mission statement concisely explains the motivation driving its ambitions: “To preserve, promote, and disseminate the historic and cultural diversity of Dartmouth, Massachusetts.”

In pursuit of this mission DHAS has set out to secure primary records, preserve them, and make

1 John W. Tyler, “A Brief Report on Publications,” in CSM Newsletter ; Volume 27, Number 1 (September 2022).

them accessible for researchers and genealogists. DHAS often describes its website, as a “researchers’ workbench.” Many primary record sets are uniquely available on the website including:

(1) Town Meeting records of the old township of Dartmouth, 1674-1787

(2) The Bristol County Land Record Abstracts of Dan Taber

(3) Records of the Dartmouth Monthly Meeting of Friends2

2 Quality checking the last 5% of the 6,000 pages is still in process but will be finished shortly. This collection of primary source records for the Dartmouth Monthly Meeting are held in the Special Collections of the UMass Dartmouth Libraries, http://findingaids.library.umass. edu/ead/mums902-d378

21 | Spring/Summer 2023

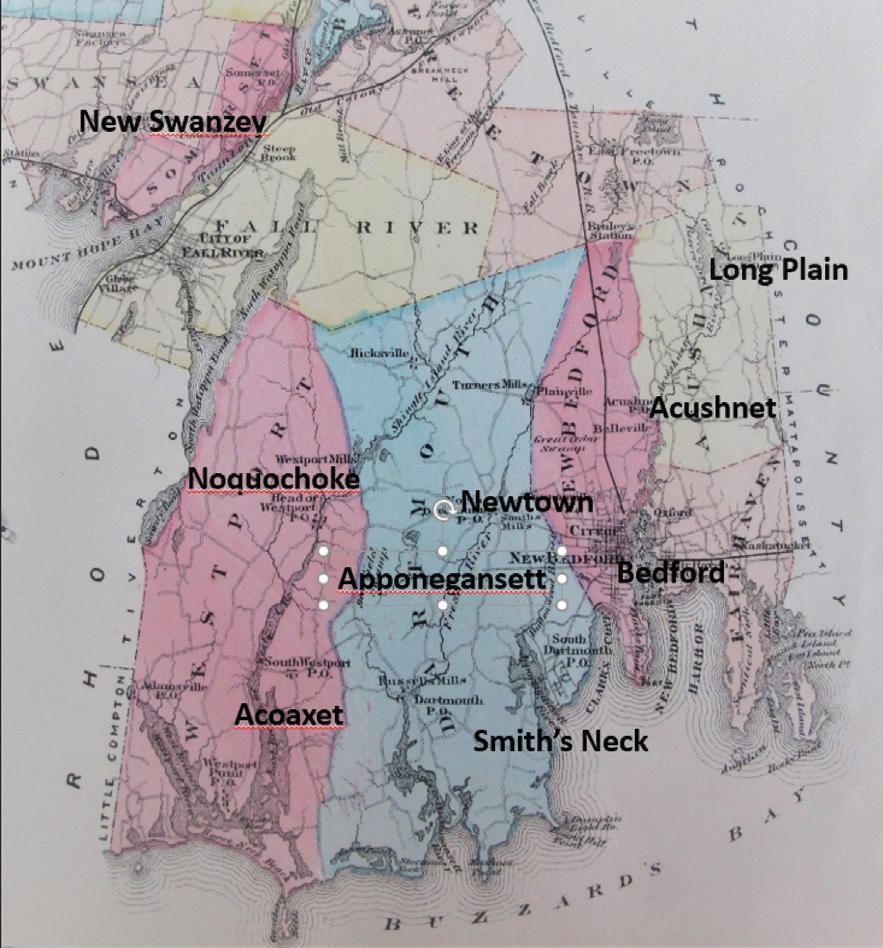

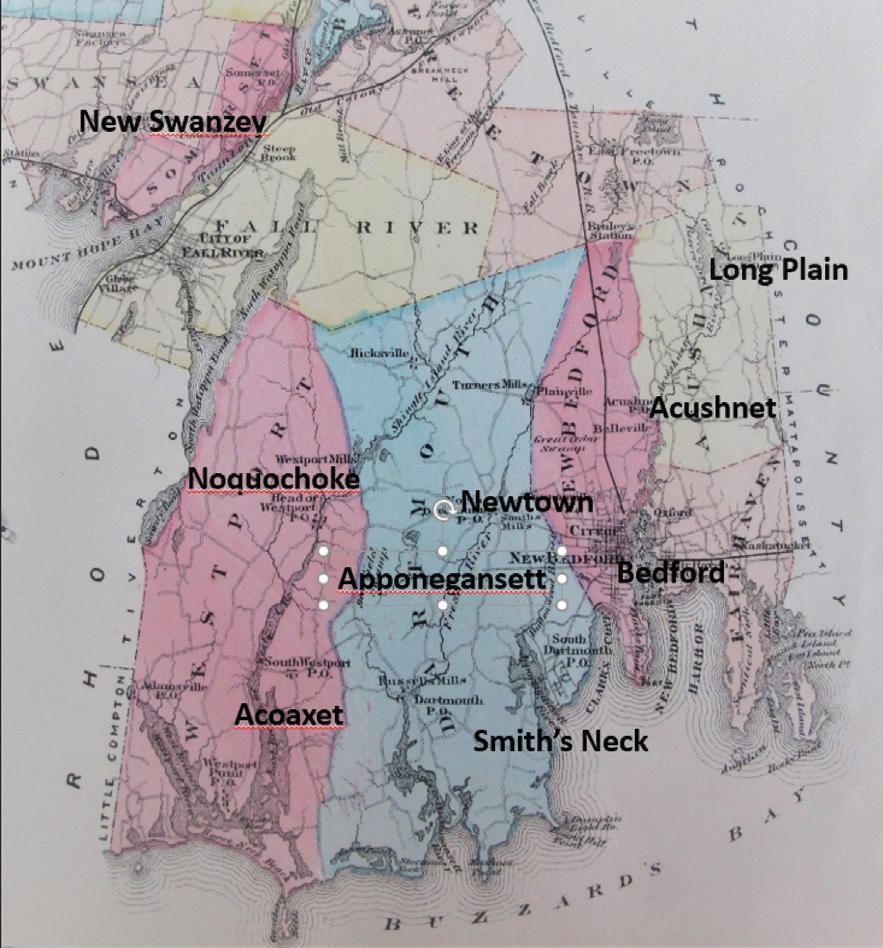

Fig. 1. Quaker Meetings in the Old Dartmouth region.

The Dartmouth Quaker record begins in late 1698 and early 1699 when the Dartmouth Monthly Meeting was “set off” from the Rhode Island Friends Monthly Meeting. Located on the western edge of Plymouth Colony and an equally remote border with settled Rhode Island, the “Old Dartmouth” region was a convenient refuge for Native Americans, freed Blacks, and religious dissidents.3 The region became a refuge for many Quakers who, being viewed as deviants from orthodoxy, were commonly mistreated and generally unwelcome elsewhere in Plymouth Colony and the Puritan Massachusetts Bay. The Friends became a majority population of colonial Old Dartmouth and remained so for many years.

One feature of Quakerism, enforced from its earliest days, was the requirement to have Monthly Meetings for business which, while not “worship meetings,”

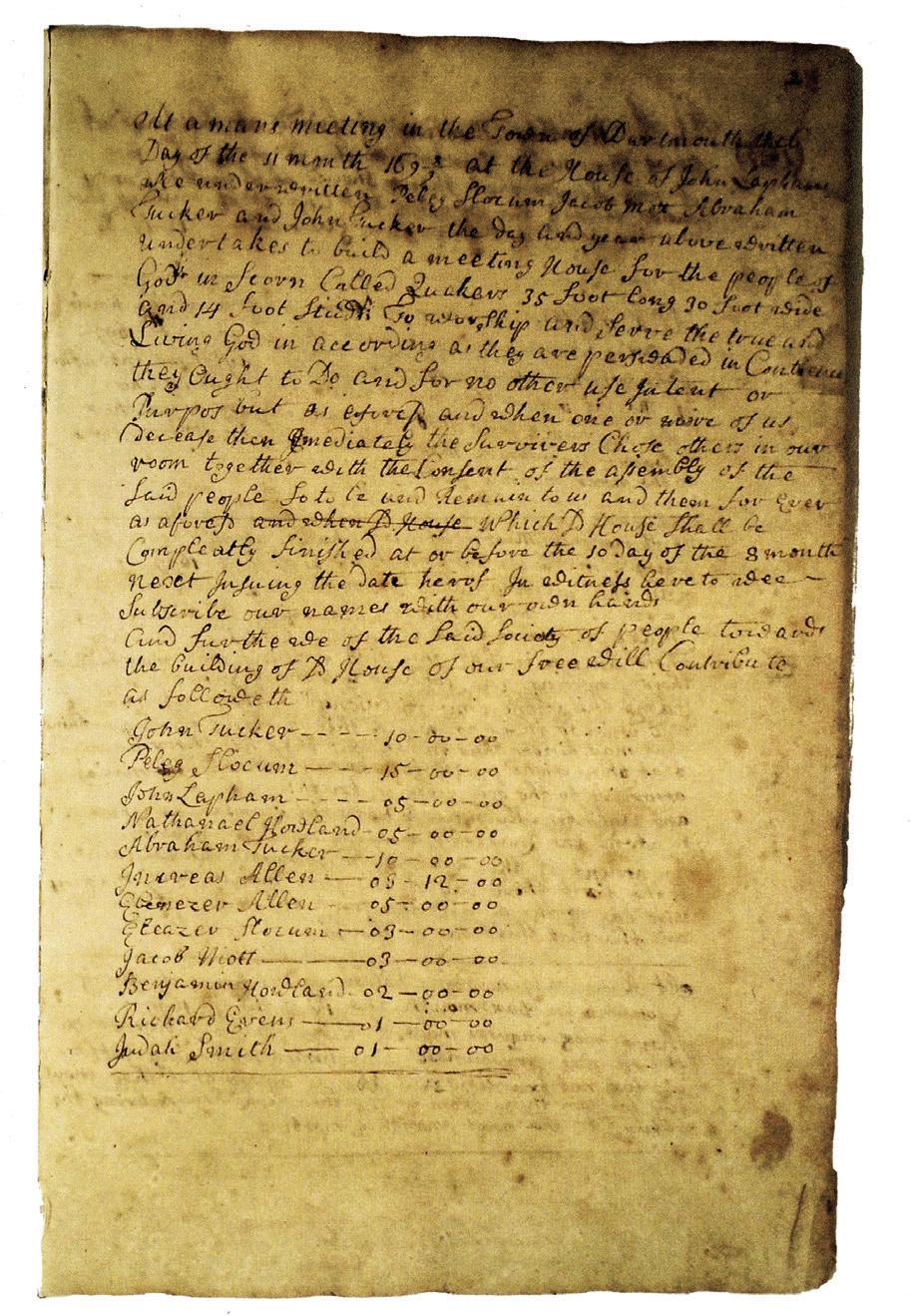

were worshipful and, significantly, were required to keep written minutes. These minutes were (and still are) kept in journals which were preserved, dated, and certified by the Clerk of the Meeting. The Dartmouth Monthly Meeting (DMM) recorded monthly minutes from “11th month 1698” forward. A large collection of journals resulted with their roots in the seventeenth-century Old Dartmouth colonial experience. These journals were variously named Men’s Minutes, Women’s Minutes, and Combined Minutes reflecting the fact that for a time only men met in the Men’s Meeting, women in the Women’s Meeting, and later in the mid-nineteenth century, the two met together in the Combined Meeting. Other types of records were journalized and preserved by the DMM as well. These included Journals of Births, Marriages and Deaths, Book of Discipline (Rules for Faith and Practice), and Book of Removals (documenting the permanent or temporary transiency of Friends between Meetings in other geographical settings).

22

3 John W. Tyler, “Foreword,” in The Minutes of the Dartmouth, Massachusetts Monthly Meeting of Friends 1699-1785, ed. Thomas D. Hamm (Boston, 2022), xi.

Fig. 2. Select pages from The Minutes of the Dartmouth (MA) Monthly Meeting of Friends, 1699-1785 showing original 1699 manuscript and transcription text. “Dartmouth Monthly Meeting of Friends Records,” Image courtesy of Smith’s Neck Meeting.

These archival materials are highly significant, and quickly became an area of focus for the efforts of DHAS. To execute the publication of The Minutes of the Dartmouth Monthly Meeting of Friends, 16991785, the original minutes had to be digitized and then transcribed. DHAS played a pivotal role in this effort, thanks to the support of Marcia Cornell Glynn and Russell Cornell, Katherine Plant, Robert E. Harding, and The Monthly Meeting. The latter became aware of the need to find another way by which these fragile, environmentally sensitive records might be consulted, settling on digitization as the best path forward and granting the DHAS permission to undertake the project. DHAS leaders Bob Harding and Dan Socha and advisor Jane Fletcher Fiske tackled the transcription and digitization project. The now-completed DHAS Quaker Transcription Project consumed several years of work from a dedicated management team, volunteers (both members and friends of DHAS), and two commercial transcription companies. It produced an accessible and valuable mine of detailed information about the Dartmouth

“Friends,” as Quakers are commonly known, and provided the foundation for this recent two-volume publication.

The Dartmouth Quaker records have special value to genealogists and historians because they are primary sources, recorded at the time the events occurred by reliable clerks of the DMM. These types of records provide multiple opportunities to ensure the correct spelling of names and details of most of the incidents chronicled, because of the Friends’ particular custom of patiently repeating issues and waiting for general acceptance by the whole meeting. All the minutes are dated, thus placing them accurately within a timeline, and the Quaker requirement for “certificates of removal” when individuals or families moved from the jurisdiction of one monthly meeting to another (whether for marriage, visiting, preaching, or permanent relocation) yields very detailed information about patterns of geographic migration, since they specify locations, people, and specific times.

23 | Spring/Summer 2023

Fig. 3 Manuel Goulart (Azorean-American, 1866-1946). View of Apponegansett Meeting House, South Dartmouth, 1933. Image printed from a glass plate negative. NBWM, 1993.48.18.95.

24

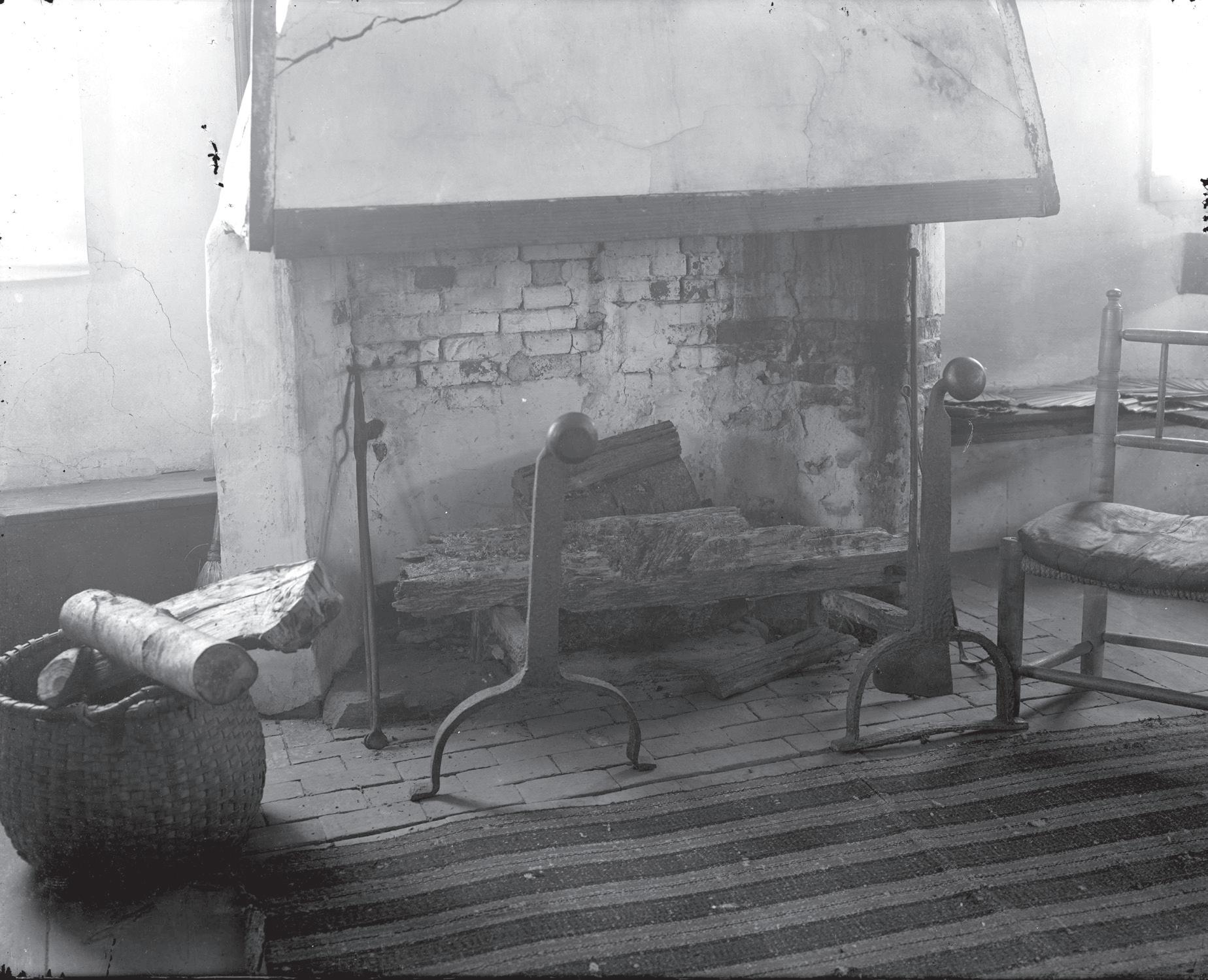

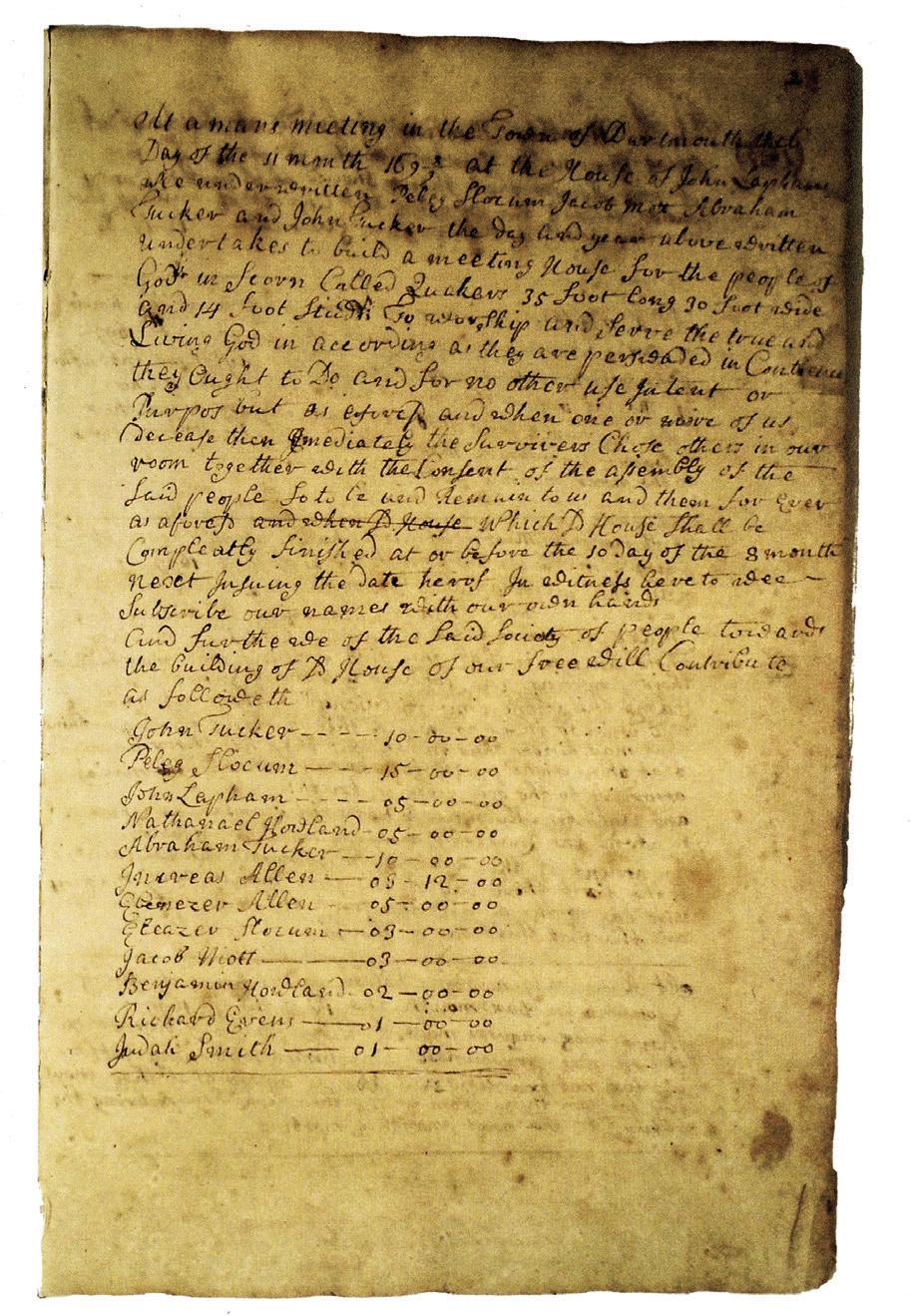

Fig. 4. Joseph G. Tirrell (American, 1840-1907). Fireplace at the Apponegansett Meeting House, circa 1880. Image derived from a glass plate negative. Built in 1799 on the site of the original 1699 Meeting House, this structure has two fireplaces, one at each end of the building for the comfort of the separate women’s and men’s meetings. NBWM, 2000.100.85.353.

Picturing Pilot Whales, from George Hathaway Nickerson to Daniel Ranalli

By Marina Dawn Wells, Photography Collection Curatorial Fellow

“

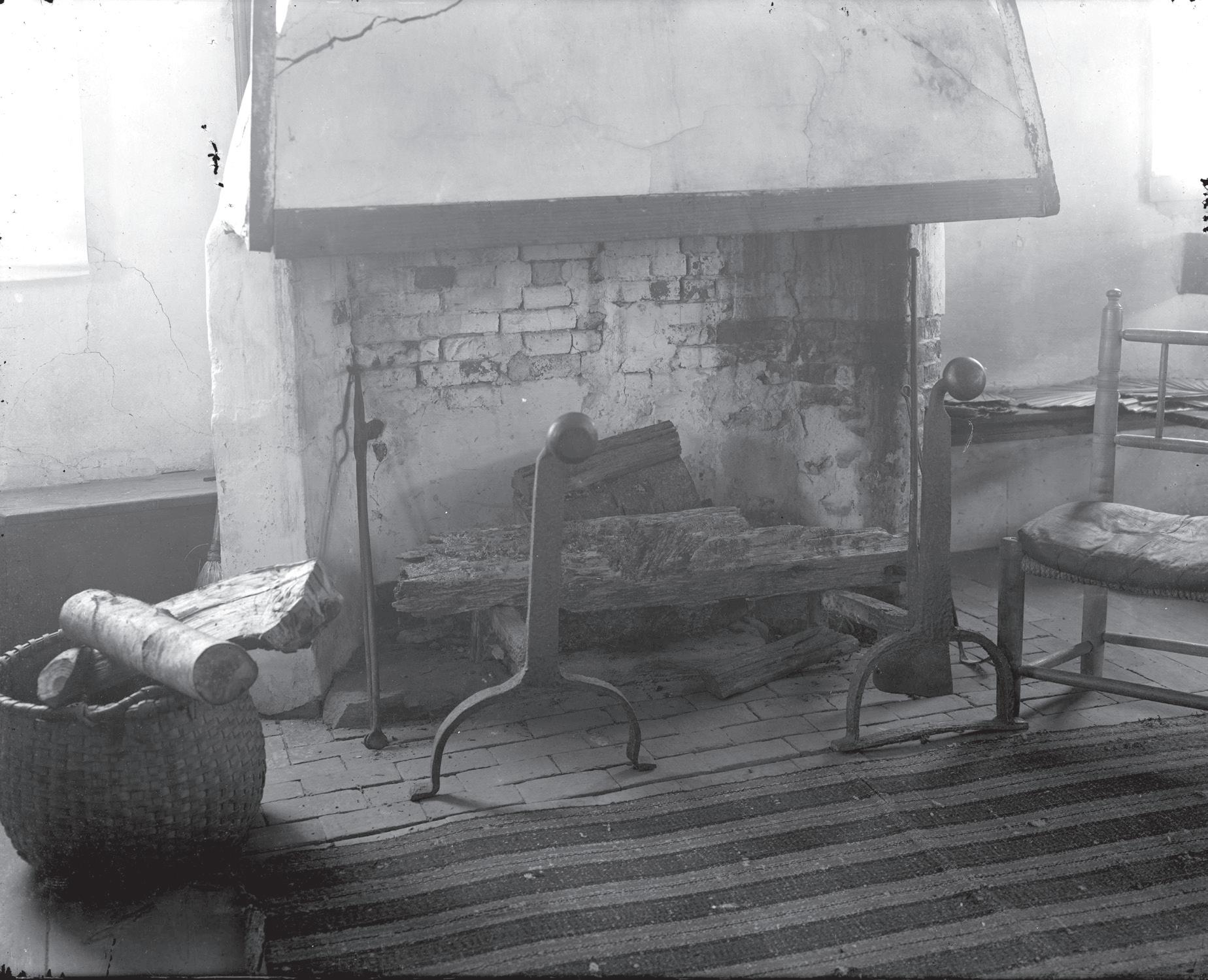

Amid the torrent of whale strandings in the 2020s, it is painful to imagine a time when such events were sought out and glorified. Many of the NBWM’s paintings, prints, photographs, postcards, and advertisements actually celebrate the oft-overlooked history of pilot whales dying along Atlantic shores.

Blackfish," now known as long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melaena), swim along New England’s coast, while short-finned pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus) make their homes farther south. These small cetaceans were easier to capture than larger species, and oil manufacturers valued their smooth, spermaceti-like oil. In the late nineteenth

25 | Spring/Summer 2023

From

Our Fellows

Fig. 1. Cape Cod Post Card Co. after George Hathaway Nickerson, “Blackfish Driven Ashore,” 1939. Postcard, 3.5 x 5.5 inches, NBWM #2000.101.173.

century, long-finned pilot whales were also captured through a photographic lens. From professional pictures in the 1870s to point-and-shoot snapshots of the 1900s, people have often looked at dying pilot whales with positive interest. Today, artists and activists grapple with how to depict pilot whales, whose visual representations have gathered different meanings over time––as demonstrated by the 2023 exhibition of multimedia works by Daniel Ranalli (b. 1946) at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Ranalli’s artwork laments whale strandings (including deliberate hunts of pilot whales) and builds upon the ambivalence of historical imagery toward human-animal relations.

Only 150 years ago, people killed massive numbers of pilot whales, responding to demands for watch and chronometer lubricants. Manufacturers like Ezra Kelly and William Nye of New Bedford and David C. Stull of Provincetown made their fortunes from jaw oil and what they called “melon” oil from the pilot whale’s head, where the animal carries an oleaginous organ that avoids coagulating in cold temperatures. Some killed the whales systematically alongside other species during offshore whaling voyages. Others took advantage of schools that swam close to shore, embarking in small craft to violently herd the animals onto the beach with harpoons and bare hands. It was likely in 1874 that professional photographer George Hathaway Nickerson (1836-1890) climbed into a boat in Provincetown to chase a pilot whale school that had entered Cape Cod Bay. As the Provincetown Advocate wrote, Nickerson was one of about three hundred “clerks, printers, clergymen, veteran whalers, shipmasters, and photographers all participating in the fracas and all coming in for a portion of the proceeds.”1 Clearly, such news excited hopes to profit from the animals. The community also scrambled to see the sheer spectacle created by the hunt. Given this visual interest, the photographs Nickerson snapped would live on long after the whales died of dehydration on the beach.

In the years that followed, Nickerson’s images of pilot whales sold as stereocards, postcards, and even

1 Provincetown Advocate (December 24, 1874); quoted by G. Brown Goode, The Blackfish and Porpoise Fisheries, from The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States V I and II (Washington, D.C., 1884), 304.

advertisements for oil manufacturers. These photos and others like them appeared repeatedly in the northeast, even after the turn of the century when the dominant Nye oil company moved its “fishery” to Hatteras Island.2 Postcards burgeoned in popularity as towns on the outer Cape shifted their economies away from fishing and toward tourism. As the deliberate stranding events fell further into the past, these pieces of visual culture captured a quaintness that was useful for the area’s image. Postcards were even accompanied by references to the tip of the Cape as the “First Landing Place of the Pilgrims,” trading in Colonial Revival-era historical nostalgia. As advertisements, such images also explicitly promoted oil manufacturers like Nye and Stull, acting as origin stories for their company’s products. On the back of these morbid pictures, visitors penned lighthearted messages to friends and family, as one did in 1939: “What an old fashioned town.”3

2 David S. Cecelski,

Clock Oil and the Bottlenose Dolphin Fishery at Hatteras Island, North Carolina, in the Early Twentieth Century,” The North Carolina Historical Review 92, no. 1 (January 2015): 49-79; Ed Parr, The Last American Whale-Oil Company: A History of Nye Lubricants, Inc., 1844–1994 (Fairhaven, MA: Nye Lubricants, Inc., 1996).

Time and the Sea:

26

“Of

Nye’s

3 NBWM #2000.101.173.

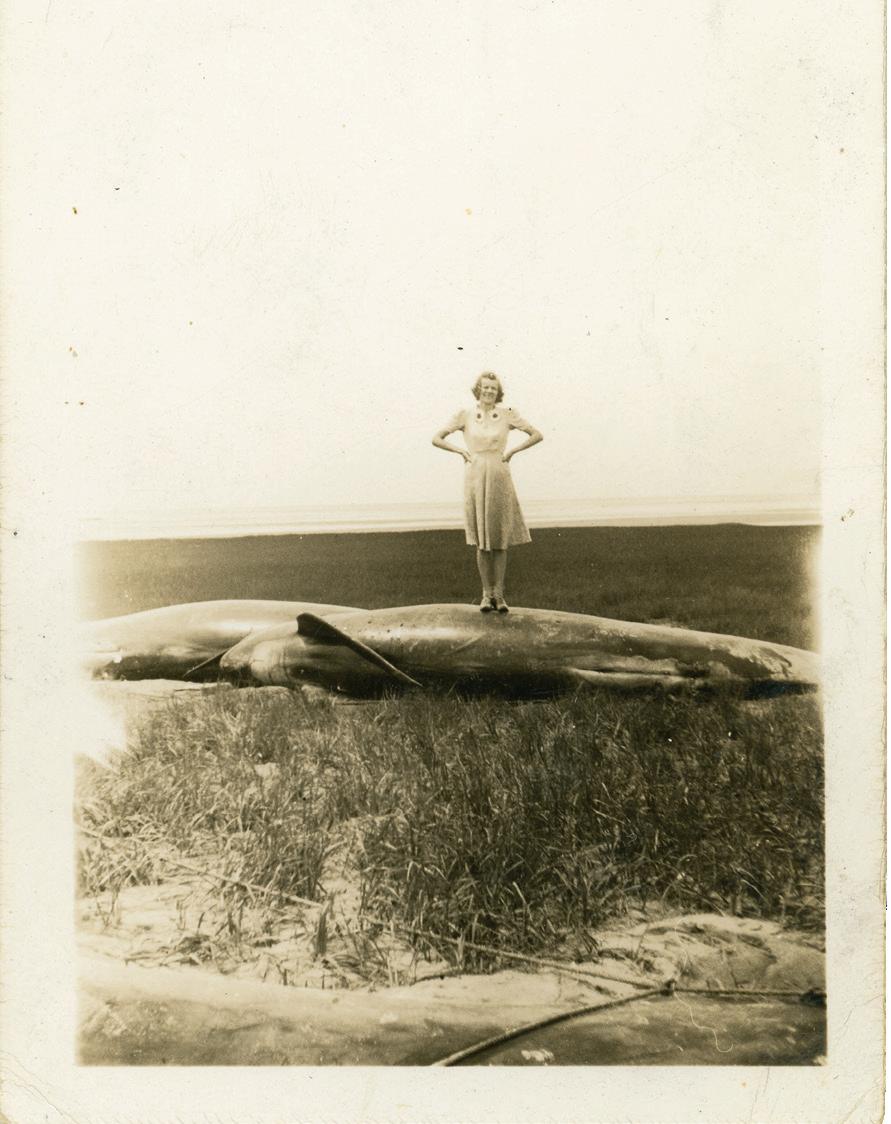

Fig. 2. Maker once known, “Woman with pilot whale,” 1945. Gelatin silver print, 2.5 x 3.5 inches, NBWM #2016.2.1.

Into the mid-twentieth century, blackfish strandings continued (as they continue today), and the practice of photographing them continued as well. Building on postcard imagery, anyone with a camera could now capture these scenes for personal amusement. In one 1940s photograph, a woman stands with a proud stance on top of a pilot whale body (Figure 2). The whale she stands on was less likely to be urgently commodified for oil than its predecessors; however, by making a photo like this, she rendered its body into entertainment. Such snapshots continued the legacy of celebrating whale death, rather than responding to it with grief.

Nye Lubricants continued producing porpoise oil as long as it lawfully could into the 1970s. In a photograph from that time, Black workers and families stand on the beach on the island of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, where Nye outsourced their operation. The unknown photographer followed others, like

Albert Cook Church (1880-1965) and Clifford W. Ashely (1881-1947), who documented American pelagic whaling with anticipatory nostalgia. In this scene, well-dressed women and a dog look on as men in minimal clothing work on pilot whale bodies that lay in pieces on the ground. This perspective immerses the viewer in the gory process of rendering life into death, in the years that the industry itself also approached its own end.

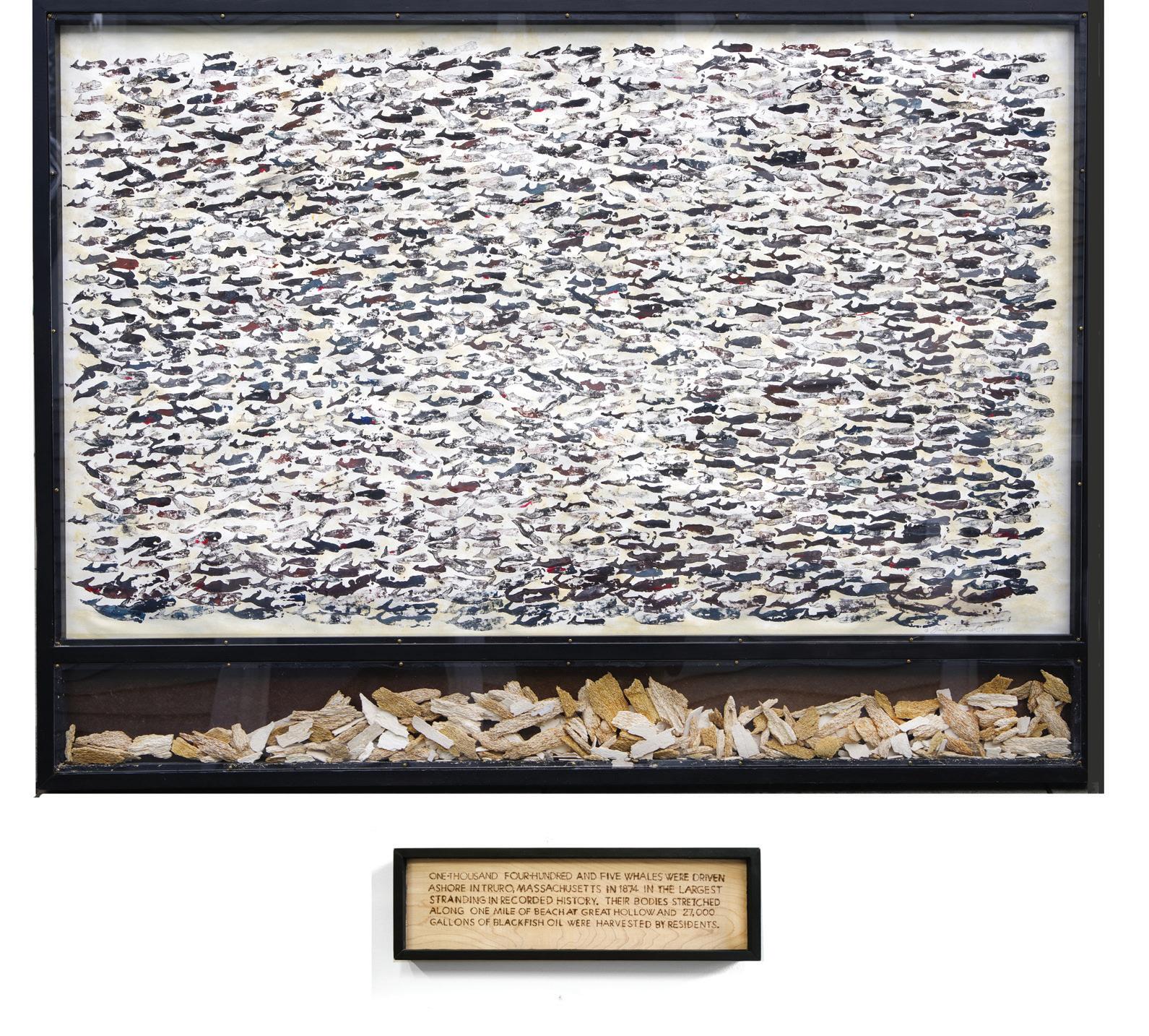

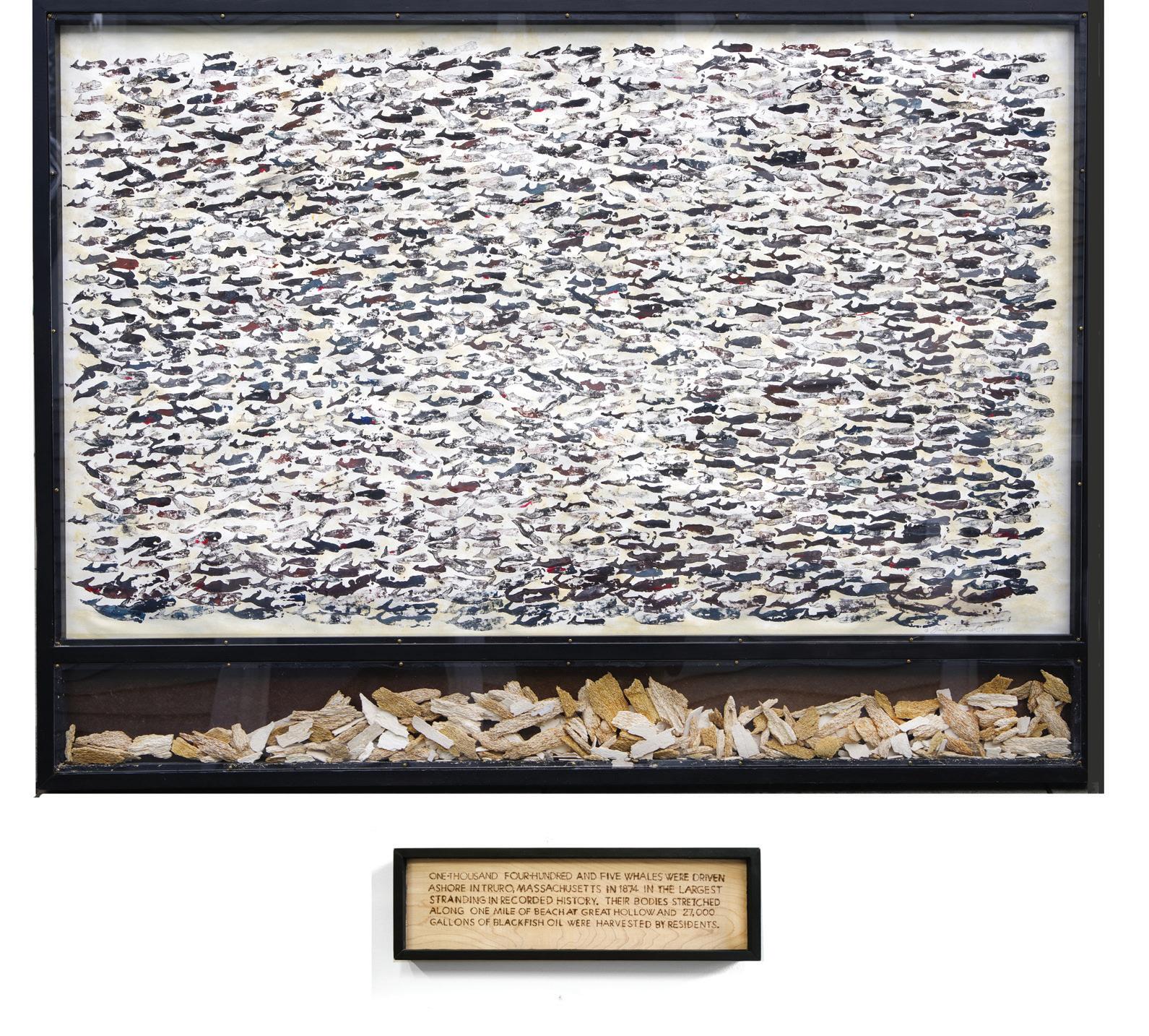

With these scenes now decades in the past, contemporary artwork provokes further questions about how to picture pilot whale strandings, even in a culture with ostensibly changed sensibilities. In Whale Stranding, an ongoing series inspired by the firsthand experience of a stranding event, Daniel Ranalli creates work that extends to sculptural and conceptual forms. Pieces like 1405 Whales (1997) contrast the explicit photographic depictions of whale bodies examined thus far (Figure 4). In fact, 1405 Whales refers to the

27 | Spring/Summer 2023

Fig. 3. Maker once known, “Men working on blackfish for Nye Oil on St. Vincent and the Grenadines,” c. 1968-1972. Negative, 4 x 5 inches, NBWM #39080.

same stranding event that likely resulted in Nickerson’s original photographs in 1874. While Ranalli and Nickerson both emphasized the abundance of bodies, Ranalli renders the whales as stylized figures. His stamps represent whale deaths, referring to nineteenthcentury whalemen’s documentation in logbooks. Although the marks are dynamic with alternating colors and angles, many look faded as if inked with a tired hand. Additionally, unnamed bone fragments pile into a window below the collection of stamps, representing the tangible but anonymous bodies lost in such an event. Ranalli’s depictions unsettle the viewer, given the contradictory affects the same event could generate. They seem to alienate the positive excitement experienced by people in the past, to instead highlight horror for contemporary viewers.

From Nickerson to Ranalli, every image of a whale––alive, dead, or dying––initiates a relationship between viewer and viewed, killer and killed. Ranalli’s work calls

attention to the systematic whaling of the nineteenth century through its whale stamps, the bones of animals on the beach, and by implicating historic actors both past and present. As Ranalli’s work suggests, humans have long participated in these tragedies, whether by causing them, recording them, or bearing complicit witness to them. Thankfully, prevailing sentiments have changed alongside protective laws mandating that whales not be killed––particularly with intent. However, as whale deaths become more visible in the twenty-first century, we should continue to feel their weight rather than become habituated to them. Every story and picture of a new mortality event requires that we resist returning to a recent past, when dead whales provoked pleasurable awe, spectatorship, or even celebration as they breathed their last breaths on the beach.

28

Fig. 4. Daniel Ranalli (b. 1946), 1405 Whales, 1997. Unique block print on rag paper with bone fragments in artist’s frame & woodburned text panel, 38 x 49 inches, collection of the artist.

Paper Money and the “Free Banking Era” of 1837-1862: The NBWM Paper Currency Collection

By Aidan Goddu, Undergraduate Curatorial Intern, New Bedford Whaling Museum

By Aidan Goddu, Undergraduate Curatorial Intern, New Bedford Whaling Museum

For much of the history of the United States, questions surrounding the function of the central financial institution of the country, its role, power(s), and responsibilities surrounding monetary policy have been common. The first National Bank of the United States was a politically contentious issue, and after twenty years, its charter was not renewed upon its original expiration in 1811. Supporters of the first National Bank would eventually avenge its fall by chartering a second. Both the first and second national banks performed many functions that were similar to commercial banks during the period, but they also functioned to more easily facilitate the payment of taxes and as a receiver of deposit from the federal government. Opponents of the national bank would once again prove victorious when President Andrew Jackson vetoed the renewal of its charter.

Once the charter of the 2nd National Bank expired in 1836, the country was once again without a central

financial institution, leaving only state-chartered banks to fill the gaps. These types of banks had existed for over fifty years at this point, with the first of these – The Bank of North America – being chartered in Philadelphia, PA on December 31, 1781. Statechartered banks would issue currency for circulation in their local area with little government oversight until the introduction of the National Banking Act in 1863 brought about the eventual demise of the state-chartered banking systems in favor of national charters.

Across the nation as a whole, the “Free Banking” period was one of general insecurity in the financial institutions present in the country. Under the system, many poorly managed and unstable banks issued currency that would be rendered valueless once the issuing bank went under. Notes that were traded a sufficient distance away were traded at a discount of their par value, reflecting the travel costs of redemption as well as the risk of default by the issuing bank.

29 | Spring/Summer 2023

Fig. 1. One Dollar banknote issued by the Metacomet Bank of Fall River, November 15, 1853. 3 x 7 inches, NBWM, 2002.59.35. Gift of the Kendall Whaling Museum Trust.

Despite the general trends of insecurity and the declining value of notes further away from their banks of issue, in New England state-chartered banks proved to be more resilient, partly due to the Suffolk System. The Suffolk system, named after the Suffolk Bank of Boston, operated by having each member bank maintain a reserve deposit in the Suffolk Bank (or other participating Boston bank), with the Suffolk Bank then accepting and clearing all banknotes issued by the members of the system at par value.

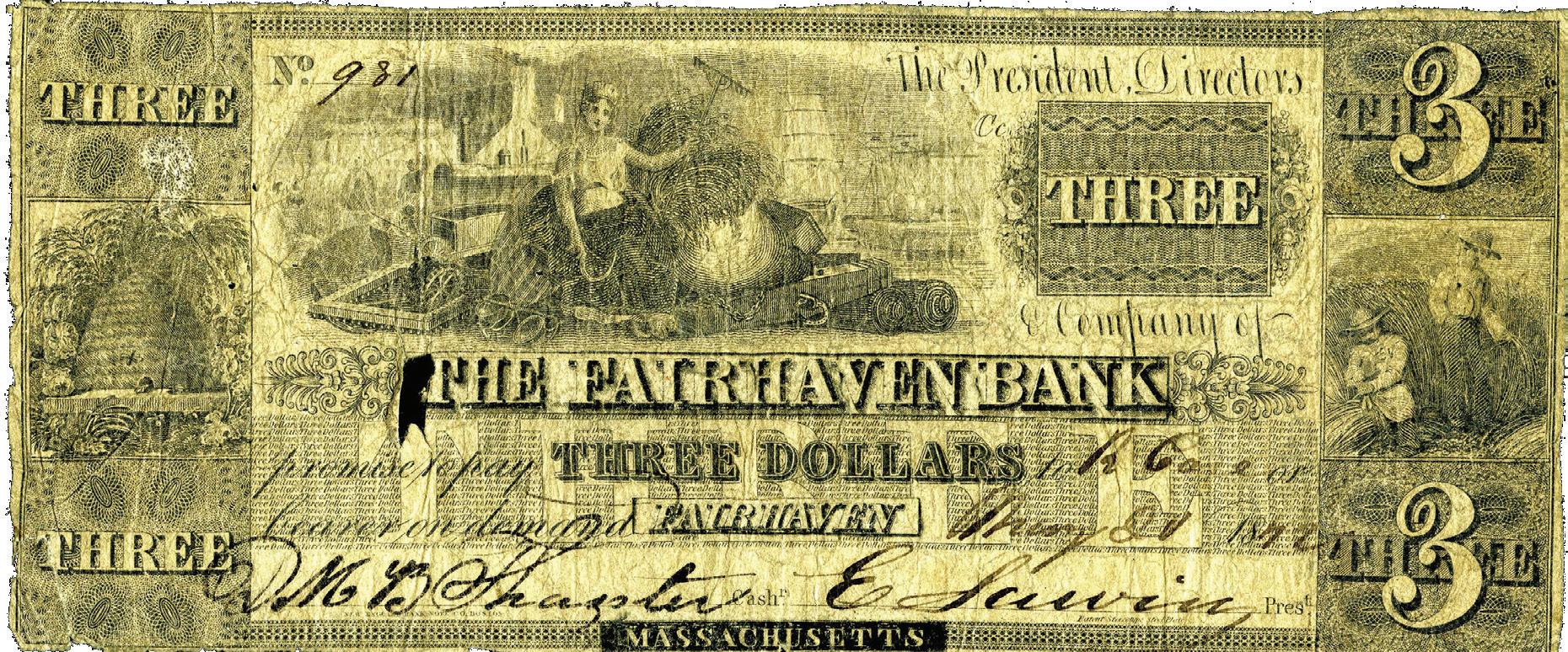

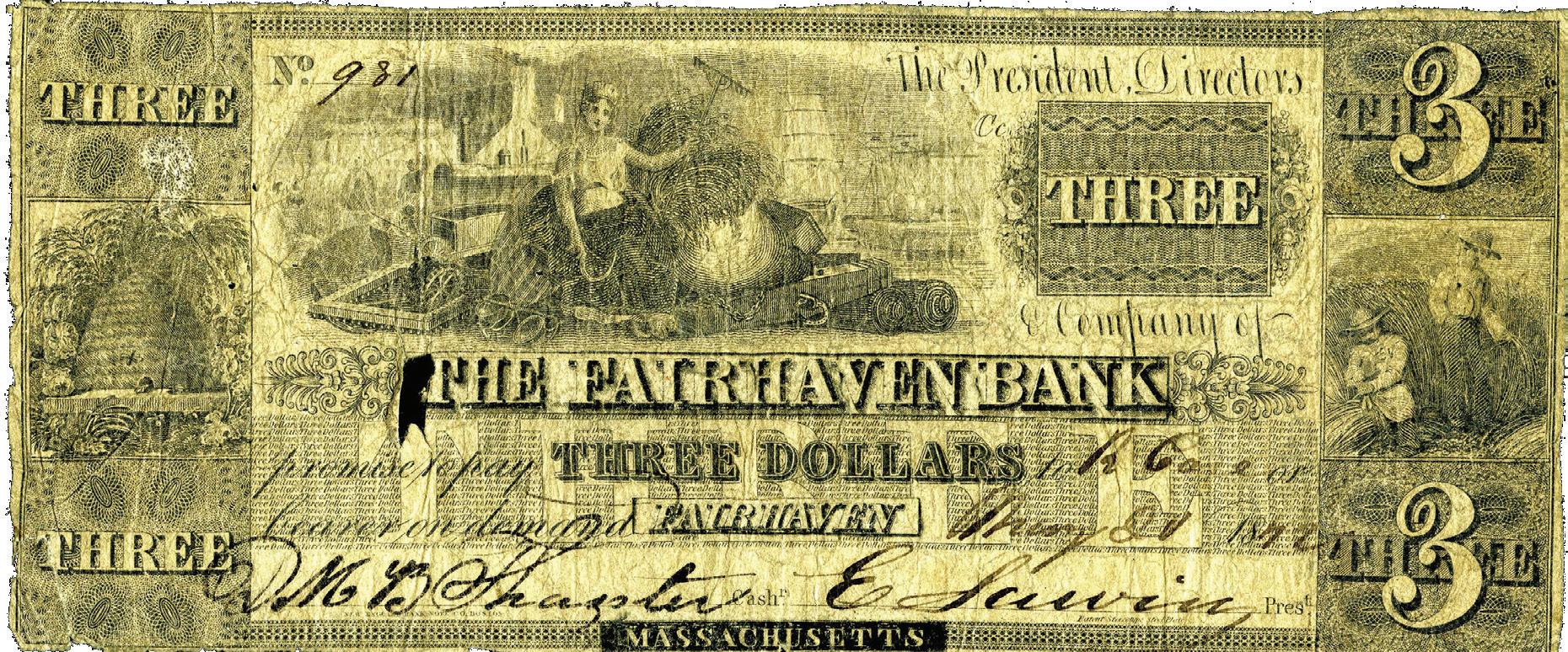

State-chartered banknotes in the collection: The Museum preserves many notes from several state-chartered banks, principally from the local SouthCoast area. Many of the designs are common among different banks since banks would order notes from the same suppliers and engravers. These notes have various artistic motifs, from whaling and farming to classical American depictions of Liberty personified.

Notes in our collection issued from regional banks include:

• The Fall River Bank (Fall River)

• The Metacomet Bank (Fall River)

• The Marine Bank (New Bedford)

• The Bedford Commercial Bank (New Bedford)

• The Merchants Bank (New Bedford)

• The Mechanics Bank (New Bedford)

• The Fairhaven Bank (Fairhaven)

In addition to these local notes, the museum also possesses various notes issued from state-chartered banks in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and several other states, with a particular focus on the Northeast. Many of these, including notes from the Whaling Bank of New London, the Commercial Bank of Perth Amboy, NJ, and the Suffolk County Bank of Sag Harbor, NY, were collected specifically for their whaling imagery. Banks represented in this part of the collection include:

• Manufacturers & Mechanics Bank (Nantucket, MA)

• The Citizens Bank (Nantucket, MA)

• Phoenix Bank (Nantucket, MA)

• Nantucket Bank (Nantucket, MA)

• The Warren Bank (South Danvers, MA)

• The Broadway Bank (Boston, MA)

• The East Bridgewater Bank (East Bridgewater, MA)

• The Leicester Bank (Leicester, MA)

• The Dorchester & Milton Bank (Dorchester, MA)

• The Marblehead Bank (Marblehead, MA)

• Washington Bank (Boston, MA)

• Bank of Rhode Island (Newport, RI)

• Mount Vernon Bank (Providence, RI)

• The Farmers and Mechanics Bank (Pawtucket, RI)

• The Washington Bank (Westerly, RI)

• The Franklin Bank (Chepachet, RI)

• Brunswick Bank (Brunswick, ME)

• Hall and Augusta Bank (Hallowell, ME)

• Castine Bank (Castine, ME)

• The Commercial Bank (Bath, ME)

• The Claremont Bank (Claremont, NH)

• Hillsborough Bank (Amherst, NH)

• The New Hampshire Union Bank (NH)

• The Whaling Bank (New London, CT)

• Stonington Bank (Stonington, CT)

• Union Bank of New London (New London, CT)

• The Bridgeport Bank (Bridgeport, CT)

• The Merchants’ Bank (Norwich, CT)

• Phoenix Bank (Litchfield, CT)

• The Eastern Bank (West Killingly, CT)

• The Hartford Bank (Hartford, CT)

• Bank of Orange County (Chelsea, VT)

• The Bank of the Wilmington and Brandywine (Wilmington, DE)

• The Marine Bank (Baltimore, MD)

• The Commercial Bank of Wilmington (Wilmington, NC)

• The Commercial Bank of New Jersey (Perth Amboy, NJ)

• The Farmers and Manufacturers’ Bank (Poughkeepsie, NY)

• The Merchants Banking Co. (New York, NY)

• The Marine Bank (Buffalo, NY)

• The North American Bank (New York, NY)

• Suffolk County Bank (Sag Harbor, NY)

• The Commercial Bank

• Albany, NY

• Saratoga, NY

• Rochester, NY

• Clyde, NY

30

National banknotes in the collection: The Museum also preserves banknotes issued as national currency in concordance with the National Banking Act beginning in 1863. These notes are more similar to one another than their state-chartered predecessors, and represent a shift towards greater federal control over the financial systems in the country. The Act established requirements for banks to use Treasury bonds to back notes at 90% of their value and a 25% specie reserve on circulation and deposits, as well as a $300 million circulation ceiling and ban on loans secured by real estate.

In its original form, the National Banking Act proved unpopular. For the system to function better, amendments were made to entice large banks in New York, as well as smaller “country” banks, to engage in the national banking system. In the spring and summer of 1864 congress amended the system, lowering the reserve requirements for country banks from 25% to 15%, and allowed for the multilayered pyramiding of reserves for New York banks. The amendments helped the system gain popularity among banks across the nation, and the national banking system would last across the nation until the institution of the Federal Reserve System in 1913.

The National banknotes in the Whaling Museum’s collection are a smaller collection than the “free banking” era notes, and consequently come from

a smaller range of banks. All of the notes in our possession from this system are from the New England region, with the majority of issuing banks located in New Bedford, MA. National banknotes in the collection include examples issued by:

• The First National Bank of New Bedford (New Bedford, MA)

• The Merchants National Bank of New Bedford (New Bedford, MA)

• The Safe Deposit National Bank of New Bedford (New Bedford, MA)

• The Mechanics National Bank of New Bedford (New Bedford, MA)

• The National Bank of Commerce of New Bedford (New Bedford, MA)

• The National Bank of Fairhaven (Fairhaven, MA)

• The National Whaling Bank of New London (New London, CT)

• The First National Bank of Biddeford (Biddeford, ME)

For further reading on this subject see: Jaremski, Matthew. “State Banks and the National Banking Acts: Measuring the Response to Increased Financial Regulation, 1860-1870.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 45, no. 2 (2013): 379-399. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23463525.

31 | Spring/Summer 2023

Fig. 2. Three Dollar banknote issued by the Fairhaven Bank of Fairhaven, MA, May 20, 1842. 2.75 x 6.5 inches, NBWM, 2003.101.95. Bequest of Eliot S. Knowles.

Klebaner, Benjamin J. “State-Chartered American Commercial Banks, 1781-1801.” The Business History Review 53, no. 4 (1979): 529–38. https:// doi.org/10.2307/3114737.

Michaels, Walter Benn. “The Gold Standard and the Logic of Naturalism.” Representations, no. 9 (1985): 105–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3043767.

Newman, Patrick. “The Origins of the National Banking System: The Chase-Cooke Connection and the New York City Banks.” The Independent Review, 22, no 3. (2018): 383-401. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/26314773.

Rolnick, Arthur J., Bruce D. Smith, and Warren E. Weber, “Lessons from a Laissez-Faire Payments System: The Suffolk Banking System (1825-58).” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, May/June (1998): 105-16.

Smith, Bruce D., and Warren E. Weber. “Private Money Creation and the Suffolk Banking System.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 31, no. 3 (1999): 624–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/2601080. Van Fenstermaker, J., and John E. Filer. “Impact of the First and Second Banks of the United States and the Suffolk System on New England Bank Money: 1791-1837.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 18, no. 1 (1986): 28–40. https://doi. org/10.2307/1992318.

32

For much of the history of the United States, questions surrounding the function of the central financial institution of the country, its role, power(s), and responsibilities surrounding monetary policy, have been common.

33 | Spring/Summer 2023

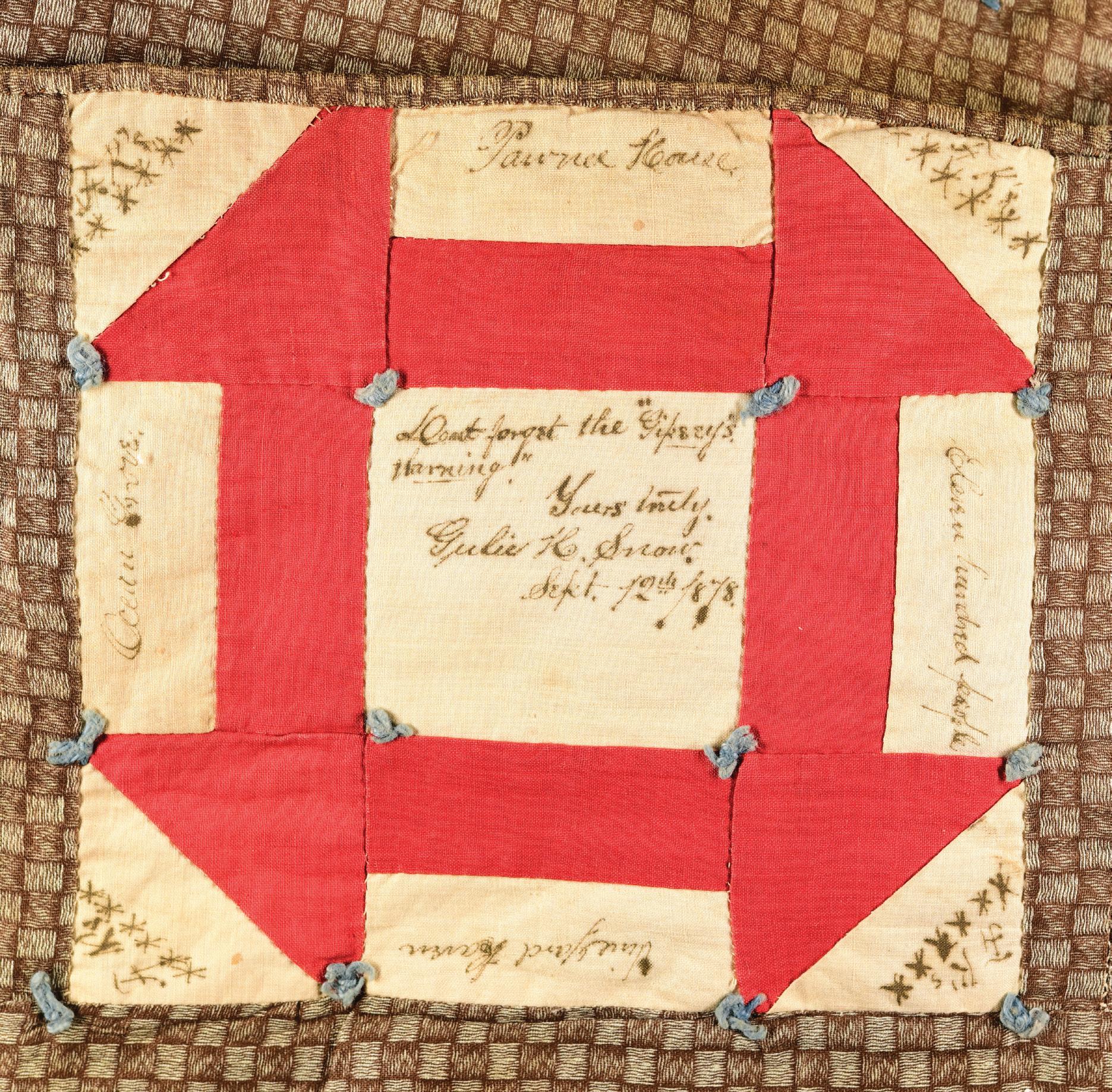

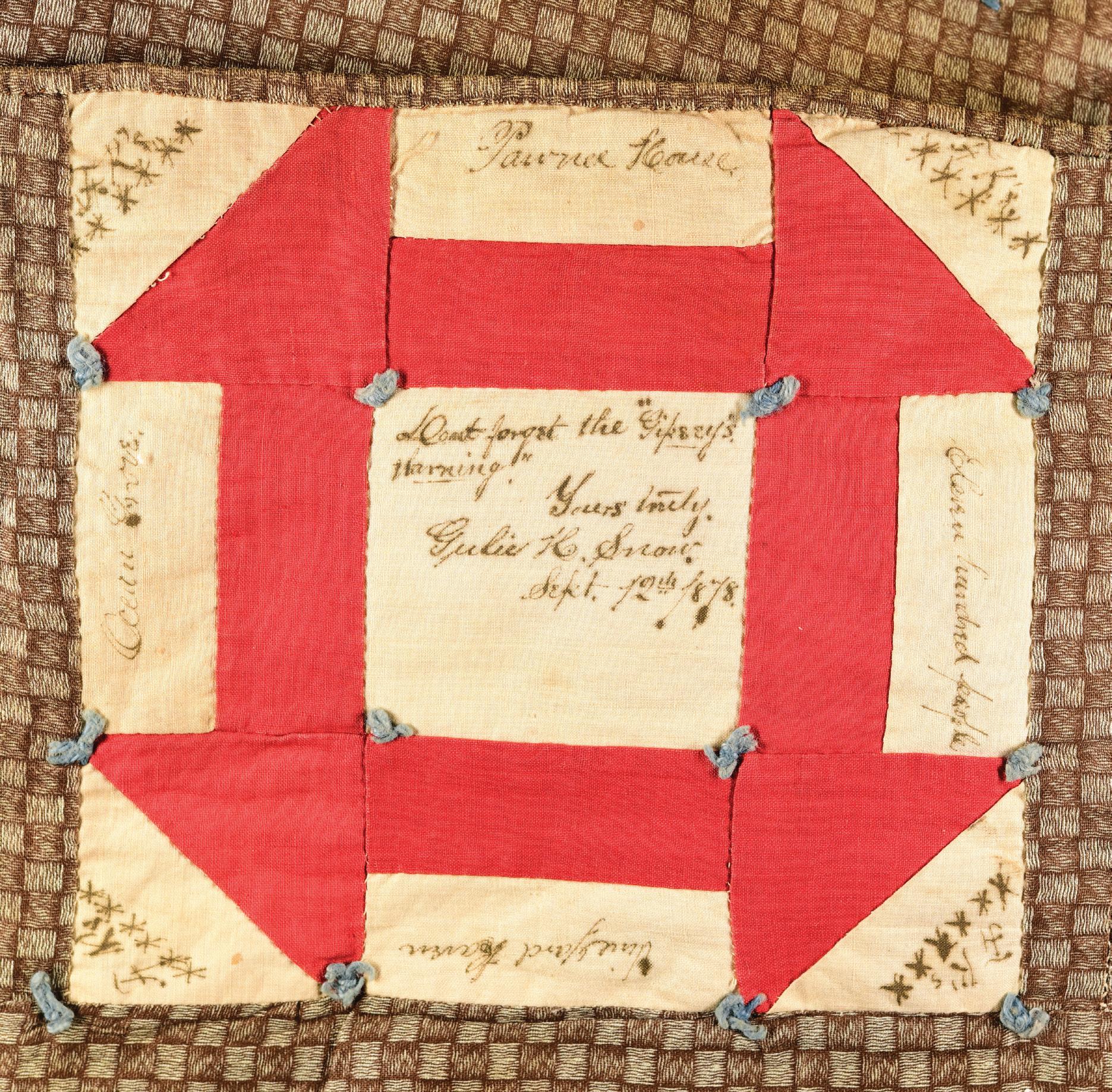

Piecework lap quilt “made by women of the Cummings family, circa 1865.” Satin. 55 x 56 inches. This quilt is made in the “log cabin” pattern. NBWM, 00.221.101

34

Stitching as Personal History

Quilts in the Collection

By Naomi Slipp, Douglas and Cynthia Crocker Endowed Chair for the Chief Curator and Director of Museum Learning

When it comes to traditional written histories, women’s stories are often hidden in the margins. Historically, women’s lives were defined by their class, race and ethnicity, social position, marriageability, domestic skills, husband, and children. If recorded, their names are often subsumed by the surname of father or husband. For the majority, their labors were domestic and familial, tied to the innumerable duties of home and the raising of children. When we look at the visual and material culture of a museum collection, however, we find vivid evidence of their work and skill, their artistry and vision. Quilts are one such product.

“Quilting” is defined as “a method of stitching layers of material together. Although there are some variations, a quilt usually means a bed cover made of two layers of fabric with a layer of padding (wadding) in between, held together by lines of stitching. The stitches are usually based on a pattern or design.”1 Quilts can also be comprised of piecework, where textile scraps are stitched together in a patchwork pattern to form a bedcover. Whatever their method of construction, a quilt can be “read” as an object in many ways. We can consider the pattern used, the fabric employed, the maker(s), the owner, or the event that a quilt might commemorate. Every quilt has a story.

In North America quilting became a popular domestic handicraft by the 1700s and took off in the 1800s, as machine-made textiles and massproduced domestic manuals disseminated patterns

1 An Introduction to Quilting and Patchwork, Victoria & Albert Museum, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/an-introduction-toquilting-and-patchwork.