LIFE ADVICE — 5

Vox Editor-In-Chief Ezra Klein spills some secrets.

COFFEE TREK — 7

Find a new coffee shop off the Red Line to call home.

SCHOOL OF ROCK — 11

These students are in a different kind of long-distance relationship.

DRUG DEALING REVOLUTION — 14

Lakeside Delivery lets you order weed to your front door.

Read the biggest fibs prospies hear on tours.

managing editor Jasper Scherer

creative director Daniel Hersh

photo directors

Natalie Escobar and Alexis O’Connor

senior features editors

Shelbie Bostedt and Clayton Gentry

senior section editors

Martina Barrera-Hernandez and Shannon Lane

associate editors

Megan Fu and Abigail Kutlas

assistant editors

Danielle Elliott and Ben Zimmermann

senior design editor Vasiliki Valkanas

designers Carolyn Betts, Hanna Bolaños, Nicholas Hagar, Lauren Kravec, Caroline Levy,

assistant photo director Jacob Meschke

photographers

Rosalie Chan, Alex Furuya, Jeremy Gaines, Rafael Henriquez, Sean Magner, Michael Nowakowski, Madhuri Sathish, Andrew Skalitzky, Mia Zanzucchi

digital product manager Aditi Bhandari

digital producers

Cameron Averill, Rosalie Chan, Annalie Jiang, Vickie Li, Allison Sun, Ashley Wu

illustrators Hanna Bolaños and Vasiliki Valkanas

corporate

director of marketing Leigh Goldstein

director of operations Samuel Niiro

director of ad sales Grant Rindner

director of talent Caroline Levy

director of business operations Daniel Hersh

board of directors

president Preetisha Sen

executive vice president Jeremy Layton

vice president Jasper Scherer

treasurer Samuel Niiro

secretary Daniel Hersh

MOST LIKELY TO STAY CALM UNDER PRESSURE

MOST LIKELY TO SUGGEST BEER PONG AT HIS FIRST PROFESSIONAL COCKTAIL PARTY

editor-in-chief Preetisha Sen

executive editor Jeremy Layton

managing editors

Tanner Howard and Samuel Niiro

assistant managing editors

Julia Clark-Riddell, Carter Sherman and Zachary Woznak

MOST LIKELY TO TAKE OVER THE WORLD

news editors

Erin Bacon and Megan Fu

features editor Elizabeth Santoro assistant features editors

Sasha Costello and Madison Rossi life and style editor Ricki Harris

assistant life and style editor Mira Wang entertainment editor Malloy Moseley

MOST HUGGABLE

MOST LIKELY TO BE BRUTALLY HONEST

MOST LIKELY TO HACK CAESAR

MOST LIKELY TO KNOW AP STYLE VERBATIM

MOST LIKELY TO SWEAR DURING A JOB INTERVIEW SASSIEST

MOST LIKELY TO LIVE TWEET

assistant entertainment editor Stacy Tsai writing editor Tia Anae

assistant writing editor Quinn Schoen sports editor Andy Brown

assistant sports editor Austin Siegel politics editor Ashley Wood assistant politics editors

Amal Ahmed and Anna Waters opinion editor Heather Budimulia assistant opinion editor Carrie Twersky photo editors

Alex Furuya and Madhuri Sathish video editor Rose McBride assistant video editors Nesa Mangal and Jon Palmer interactive editors

Rosalie Chan and Morgan Kinney assistant interactive editors

Nick Garbaty and Hayley Hu creative director Nicole Zhu graphics team

Phan Le and Bo Suh social media coordinators

Sarah Turbin and Ashley Wood webmaster Alex Duner

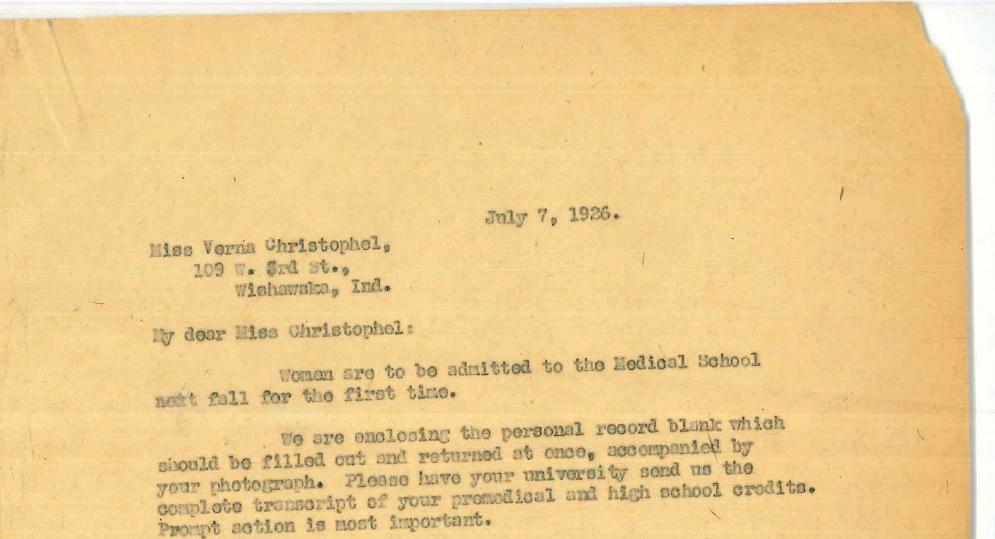

Ezra Klein was a blogger and columnist for The Washington Post from 2009 to 2014. In January 2014, he left the Post to start Vox, where he is now the editor-in-chief. Klein came to campus in April as part of the Contemporary Thought Speaker Series.

BY CAMI PHAM

“Sometimes I think we can overestimate the advantages of being well-rounded against the advantages of being really passionate and really into something. If you can find something you really love, it is worth going as deep into that as you can because when you get out of college, I think a lot of what the world looks for, contrary to what you’re told, is not well-roundedness—it is a thing you’re particularly good at and into more so than other people are.”

Photo by MICHAEL NOWAKOWSKI

BY MADELEINE KENYON

7

Number of NU football players who joined NFL teams in May. Safety Ibraheim Campbell and quarterback Trevor Siemian were drafted by the Browns and Broncos, respectively. Kyle Prater, Brandon Vitabile, Chi Chi Ariguzo, Jimmy Hall and Tony Jones signed with NFL teams following the draft.

How ordinary Hilary Duff is, according to Northwestern seniors who performed in the musical “A Not-So-Typical Gal: A Nostalgic Evening with Hilary Duff” on April 10 and 11.

2 DECADES

How long contemporary artist Julie Green spent making “The Last Supper: 600 Plates

Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Deathrow Inmates,” an exhibit at the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art.

1.5

How quickly tickets to see Bill Nye speak sold out on the first day they were released, according to the Norris Box Office.

What the hosts of the standup comedy performance Sit & Spin Stand-Up (jokingly) promised to do to the comedian with the weakest set April 3 and 4.

8

Number of Grammys Dillo Day headliner Miguel has been nominated for, including his hit single “Adorn” that won the 2013 Grammy Award for Best R&B Song.

13%

2,991

Number of votes cast in this year’s ASG presidential election, where juniors Noah Star and Christina Kim emerged victorious as president and executive vice president, respectively. Voter turnout increased by more than 1,000 from last year.

The percentage of Northwestern undergraduate applicants admitted to the Class of 2019. This number has dropped for six consecutive years.

Price for a small coffee: $2.10

Drink of choice: Chai latté

Metrics:

Easy to find:

Table availability:

Wi-Fi strength:

Best for: A quick and easy trip

Other observations:

Situated on a quiet block in Rogers Park, Towbar is bright and fresh, with simple decor and large windows. The menu is extensive and there is a full bar, but the prices are steep. Although the waitstaff are somewhat incompetent and inattentive, they get bonus points for their littlest member: One waitress’s elementary-aged daughter hangs out at the bar and will strike up a conversation with you.

Price for a small coffee: $2

Drink of choice: Peppermint tea and espresso ice cream

Metrics:

Easy to find:

Table availability:

Wi-Fi strength:

Best for: Serious solo study sessions

Other observations:

BY ABIGAIL KUTLAS

In a world where coffee shops are synonymous with college students, Northwesterners have their favorites. To many, Sherbucks, Unicorn Cafe or Coffee Lab seem like second homes. Although local spots are the most convenient, it can be hard to get serious work done when you run into friends at every turn or struggle to find an open table. This reading week, pop the Evanston bubble by hopping on the Red Line and finding a new study spot to call your own.

Price for a small coffee: $1.95

Drink of choice: Ginger lemonade and iced chai

Metrics:

Easy to find:

Table availability:

Wi-Fi strength:

Best for: A trendy meal/drink

Other observations:

The Common Cup is a neighborhood hangout, complete with a community bookshelf, art from a local children’s program on the walls and many groups of people catching up at the large tables throughout the shop. The clean, modern decor encourages productivity and the staff is always ready with recommendations. Although the food and specialty drink selection is lacking, The Common Cup offers frozen yogurt with a myriad of mix-ins to satisfy any studious sweet tooth.

The Kitchen Sink is a shop full of contrasts: dark wood counters under bright skylights, complex drinks and meals for low prices, and quietness despite its proximity to the Red Line. There are excellent spaces for sitting alone and getting work done separate from the larger tables, which can be reserved for meetings in advance. Be sure to check out the selection of handmade cards from local artists and pick up a dog treat for your favorite furry friend!

Price for a small coffee: $2.50

Drink of choice: Cortado, white peony tea and Lucky Charms cereal

Metrics:

Easy to find:

Table availability: Wi-Fi strength: Best for: An adventurous spirit

Other observations:

Although this shop was farther from the Red Line than any others visited, it was well worth the walk. The design is clean with vintage Americana decor, plush velvet and leather sofas, polished brass light fixtures and a giant American flag layered on top of gleaming white subway tile, marble tabletops and a large crystal chandelier. The staff is chatty and personable, and they can also get you a drink from the walk-up window that services sidewalk patrons.

Here’s how Roberta Buffett’s more than $100 million donation affects you.

BY ANNA WATERS

In January, Northwestern received the largest donation in the University’s history: more than $100 million. The donor, alumna Roberta Buffett Elliott, sister of business magnate Warren Buffett, gifted the money to expand the Buffett Institute for Global Studies. This donation comes as a part of the “We Will” campaign, which is seeking to raise $3.75 billion for University-wide goals. Dividing up $100 million is a colossal task that is certainly not finished yet. Starting with hiring a new leader for the Buffett Institute for Global Studies, the Buffett Institute has goals for different groups in the Northwestern community.

$55K + HIRING NEW PROFESSORS FOR GLOBAL ISSUES FACULTY PER YEAR PER YEAR AND PROGRAM PER FELLOW PER YEAR

$50K

TOWARD INTERNATIONAL STUDENT SCHOLARSHIPS

There would be a matching challenge grant to donors.

Note: Figures do not add up to $100 million. The donation will be paid in increments, so the amounts above do not reflect the entire donation.

TOWARD DISSERTATION RESEARCH TRAVEL AWARDS

Dissertations must be about international topics, and locations must be outside of the United States. There would be 40 awards available.

TOWARD POSTDOCTORAL FELLOWSHIPS

Up to three two-year postdoctoral fellows in global studies would teach one quarter course per year. Fellows will be eligible for $5,000 per year for research and $2,000 for relocation expenses.

TOWARD GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP FUNDS

Partnerships between Northwestern and foreign universities would be renewable every three years.

TOWARD ORGANIZED CONFERENCES

Grad students would be able to submit proposals on international topics. The winner would organize a conference.

TOWARD “BIG IDEA” PROPOSALS

These would be largescale, renewable multiyear interdisciplinary research programs about global challenges.

TOWARD BUFFETT PRIZE FOR EMERGING GLOBAL LEADERS

Undergrads would be able to nominate candidates under 30 years old working in areas of international significance. The winner will come to Northwestern for a workshop and speech.

Undergrads would be able to participate in a two-year paid fellowship in East Africa. + GESI SCHOLARSHIPS

+ ONE ACRE FUND JUNIOR PROGRAM ASSOCIATE

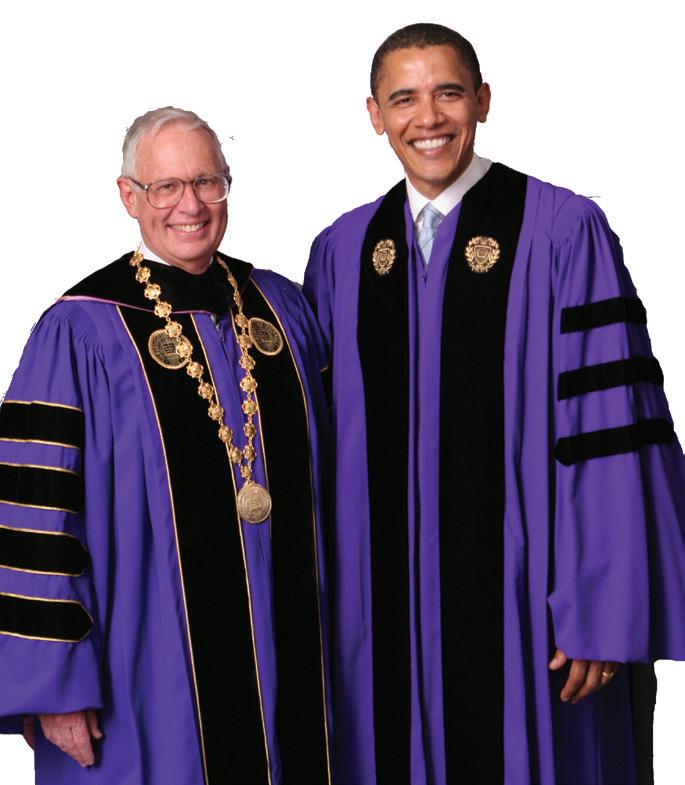

From Barack to RBG, these famous speakers

BY AMAL AHMED

Ever since your first tuition payment was due, you’ve been working toward the day you finally get to walk across a stage and receive your ridiculously expensive diploma at commencement.

This year’s speaker is Virginia Rometty, a North-

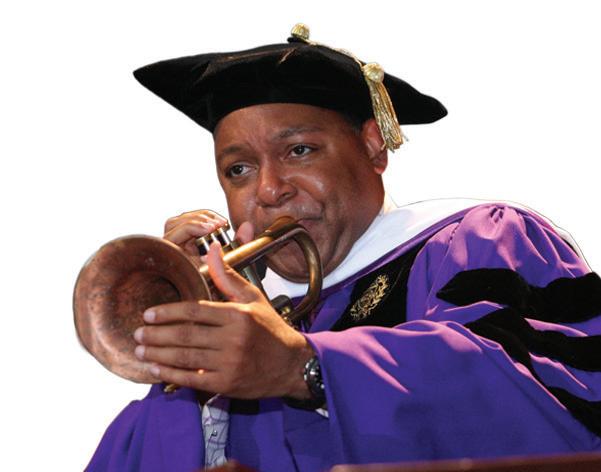

Claim to Fame: Renowned jazz musician, nine-time Grammy winner and recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Student Reactions: Swaying and clapping enthusiastically to the beat of Marsalis’s trumpet serenade.

Best Quote: “Well done…Now welcome to the world of free choice…it’s a sloppy, messy unruly world. You are suddenly called upon to contribute to the collective dream of who we are, have been and want to be. That is why I want you to take this moment to affirm your dream of yourself.”

(Cue: trumpet serenade following speech).

Claim to Fame: Second female justice appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Student Reactions: “Students said they were surprised and impressed” that the justice could come, according to the The Daily Northwestern on Feb. 19, 1998. Best Quote: “I continue to gain encouragement from people who appreciate what feminism really means. It is not a pejorative. It means freeing people, men as well as women, to be you and me, allowing people to pursue the talents and qualities they have without artificial restraints.”

Claim to Fame: Former host of The Colbert Report who is set to replace David Letterman in the fall as host of The Late Show

Student Reactions: “Many are wondering which version of the satirist will show up to Ryan Field in June. Will it be Stephen Colbert: Northwestern alum and successful comedian? Or will it be Stephen Colbert: right-wing commentator and onetime presidential hopeful?”

(North by Northwestern, Jan. 25, 2011)

Best Quote: “You cannot win improv. And life is an impro visation. You have no idea what’s going to happen next and you are mostly just making things up as you go along. And like improv, you cannot win your life.”

western alumna who currently serves as the first female CEO of IBM. But before the festivities begin for the 157th graduating class, here’s a look back at some of Northwestern’s most notable commencement speakers over the past two decades.

Claim to Fame: Egyptian-American documentary filmmaker who directed The Square, an Academy Award-nominated 2013 documentary about the Egyptian Revolution.

Student Reactions: The Daily Q, Northwestern University in Qatar’s student newspaper, reported that student opinions were split. Many students were unfamiliar with Noujaim’s work, while others were happy that a relatable female journalist was chosen as the speaker.

Best Quote: “It was taking pictures and making films that gave me a newfound appreciation for the contents of my mind allowing me to have an inner dialogue that fascinated me. If you do what you love, you will be a person that you like—and since you have to spend more time with yourself than anybody else in the entire world, it is very important that you like yourself.”

Claim to Fame: Then-U.S. Senator from Illinois with a reputation as a rising political star.

The ones who stood us up

Madeleine Albright, then-Secretary of State (1999)

Reason: A crisis in Kosovo was apparently more important than the one brewing in Evanston— students had been planning to protest Albright’s policies in Kosovo and Iraq.

Student Reactions: Expectations were high. One columnist in The Daily Northwestern posed a challenge to Obama to beat, ironically enough, John McCain’s policy-heavy speech from the previous year. Best Quote: “One of the great things about graduating from Northwestern is that you can now punch your own ticket. You can take your diploma, walk off this stage and go chasing after the big house and the large salary and the nice suits and all the other things that our money culture says you should buy. But I hope you don’t. Focusing your life solely on mak ing a buck shows a poverty of ambition. It asks too little of yourself. And it will leave you unfulfilled.”

Bill Clinton (1994), then-President of the United States

Reason: Had too much on his plate already, you know, running America.

Christiane Amanpour, journalist and foreign correspondent for CNN (2010)

Reason: She was called abroad to report on international conflicts.

Seniors create the ultimate Northwestern bucket list.

BY CAROLINE LEVY

Any senior will tell you to make the most of your time here. But what does that really mean? NBN asked the Class of 2015 to tell us. Seniors shared favorite experiences they’ve crossed off the list and others they hope to accomplish before graduation. Northwestern undergrads, here is the bucket list you’ve been waiting for.

11

Get on the rooftops of Northwestern buildings. – Charlie Scott, School of Communication

Have sex on the soccer field.

– Ali Herman, Medill

Run a half-marathon along Lakefront Trail.

– Storm Heidinger, Weinberg

Explore the steam tunnels in Tech.

– Nick DiMaso, Weinberg

Spend the night in Norris.

– Scott Egleston, School of Communication

Go on an apartment crawl.

– Stephen Piotrkowski, Medill

Visit each Chicago neighborhood for a day.

– Andrew Sonta, McCormick

Sleep on the lakefill.

– Heidinger

Go skinny-dipping in the lake.

– Herman

Visit Indiana Dunes State Park.

– Heidinger

– Piotrkowski 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Sail or paddleboard on the lake.

– DiMaso

Attend an abandoned warehouse glitter party. – Aileen McGraw, School of Communication

Have a full load of exclusively purple laundry. – Scott

Go downtown for St. Patty’s Day.

Troll a tour.

– Herman

Childhood friends create music together despite being hundreds of miles apart.

BY JACKIE MONTALVO

Photos by MICHAEL NOWAKOWSKI

Halfway through their set, the members of Zaramela begin to play an instrumental interlude. Horns booming, the lead singer beatboxes as the crowd sways with the music. The saxophone starts to play to a different tune as the guitars and drums transition one by one into a new melody. The crowd erupts as the band plays the first lines of a cover of Kanye West’s “Gold Digger,” completely engrossing everyone at Double Door Chicago.

CONTINUED

Since its debut in 2012, Zaramela—a band made up of seven college students at four different colleges—has been booking bigger and bigger shows, from the House of Blues and the North Coast Music Festival in Chicago to the South by Southwest music festival in Texas.

With influences from jazz, blues, rap, hiphop, soul, gospel, reggae and rock, Zaramela’s sound continuously morphs to match its changing musical interests and influences.

The members of Zaramela—Northwestern University student Josh Schwartz-Dodek, DePaul University students Kris Hansen and Malcolm Engel, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign students Aaron Gamalinda and Mike Jang and Columbia College Chicago students Inho Park and Jameson Brenner—have had music deeply ingrained in their lives since early childhood.

With the extensive variation in the instruments they play and the sounds they can produce, Zaramela has defied categorization.

“We can’t put a name on our sound,” Brenner says. “It’s like nothing out there and every time we come together it’s changing.”

The saxophone, trumpet and trombone bring a unique, soulful, jazzy tone to Zaramela’s music, giving them what they call their “full sound.”

“Now, whenever I’m listening to music without a brass section I’ll hear spaces where

I’m like ‘Oh, a horn there would make that sound better,’” says Schwartz-Dodek, a McCormick sophomore.

All hailing from the northwest suburbs of Chicago, Zaramela’s members have been friends since middle school and wrote original music in Engel’s basement throughout high school. There is no formula for their writing style. Usually a member of the band will have an idea and bring it to the others for feedback.

“We can’t put a name on our sound. It’s like nothing out there and every time we come together it’s changing.”

– Jameson Brenner, guitarist

“Sometimes I, or one of us, will come to the band with a full song written out with music for all the parts and play it for the band,” Brenner says. “Then we tweak it and sometimes it comes out the same as we brought it and others it sounds like a completely differ-

ent song.”

Other times, like in their cover of “Gold Digger,” the music comes from playing around with chords while jamming together.

“I was playing a few chords on the piano and Jameson asked what they were and started playing on the guitar,” Park says. “Then Kris started singing ‘Gold Digger’ over it and it just sounded really good.”

Zaramela’s three managers organize their gig requests, but the seven members plan out their own rehearsal times and schedules. Backstage before their show, Schwartz-Dodek and Hansen sat with their calendars open attempting to coordinate their schedules for the following two weeks. For those that go to school near Chicago, they practice together in a shared space at Fort Knox Studios downtown, while Jang and Gamalinda have a space in Urbana-Champaign.

The band is focusing its energy on recording a third record. “[We’re] trying to get the exact sound we want for this project,” Engel says.

While the band members have no concrete plans post-college, they hope to continue playing music for a while before going their separate ways.

Zaramela is currently in the process of writing and recording an EP, and its demo album Work (2012) and debut album Gumbo (2013) are available on Spotify.

Photo by Alex Furuya

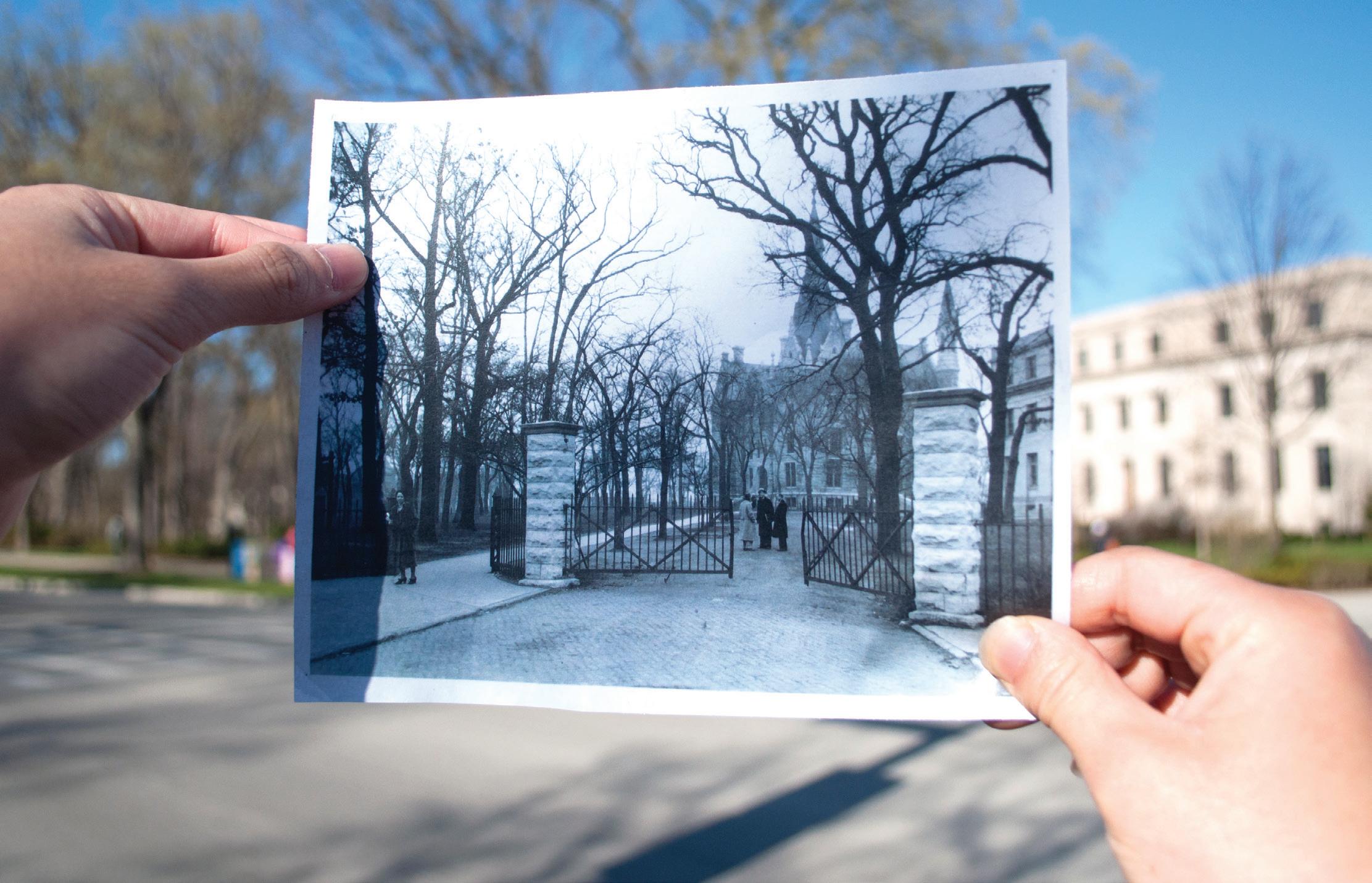

Northwestern’s nondescript campus has forgotten its history.

BY SAMUEL NIIRO

Northwestern University is a faceless campus. Most other universities in the United States have a face; Harvard has its “statue of three lies,” UChicago has a whole Midway Plaisance featuring equestrian and scientist statues, and even the University of Illinois has a massive bronze monument dedicated to learning and labor. Northwestern has nothing like those. As the University comes to grips with the history of founder John Evans, all it will need to do to remove him from campus is change the names of the Alumni Center and a room in Norris. No statue to remove, not even a portrait.

Northwestern gives no outward sign of its 19th-century beginnings. Barring a few exceptions like University Hall and Patten Gym, most of the architecture on campus dates from the post-war period. One hundred sixty-four years of history seem barely visible on Northwestern’s campus.

Yet for all of Northwestern’s constant changes, earlier genera-

tions of students and administrators hoped to create marks that would last on campus forever. One of the most notable and storied of those was the Avenue of Elms, a 75-tree-long path that culminated in a bronze boulder memorializing former Northwestern students killed in action. In June 1923, the Alumni News proclaimed that the memorial promised “to become one of the features of the campus that will live always in the memory of the men and women who go out from the environment of the University with certain ideals cherished above life itself.”

In reality, the Avenue of Elms lived for about 30 years following its 1923 dedication. Everything but the boulder was removed to make way for the expansion of the Technological Institute and the construction of Bobb-McCulloch.

The Avenue of Elms might be the most poignant loss from Northwestern’s campus, but it is hardly the only one. The original Patten Gym, which once played

home to the first-ever NCAA men’s basketball tournament, was also removed when Tech was expanded. Old natural landmarks, like a stream separating the Garrett Bible Institute and the rest of campus that students called the “Rubicon,” have fallen prey to the University’s expansion. Two 19th-century stone pillars which used to frame the south entrance to campus were removed in 2011, when they were deemed incapable of bearing the weight of the Arch that has stood there since 1999.

Kevin Leonard, University archivist and an alumnus himself (CAS ‘77), has no single explanation for why the stacks of history that fill Northwestern’s archives don’t seem to materialize on its campus, but has a couple ideas why Northwestern doesn’t wear its history on its metaphorical sleeve.

For one thing, it might be that the University just doesn’t have history that old students and administrators wanted to commemorate. After all, Northwestern

might be a notable school now, but Leonard notes that it has not been all that famous—or more importantly, rich—for much of its history. Add the fact that NU is, in the grand scheme of U.S. colleges, not that old, and there might just not be enough history.

“One hundred sixty-odd years is a long time, but it’s not as long as some of those schools out east,” Leonard says.

Northwestern is old and it has money now, but that doesn’t mean it has the same history as schools that have old money. Of course, there are alternate theories.

“It might also be that this is, really, a professional school,” Leonard says. “People come here, they focus on their studies, their careers.”

In other words, maybe the University’s approach to history is just a reflection of its students’ and administrators’ priorities. Who has time to worry about history when a glitzy new communications building will be better for classes and attract more applicants?

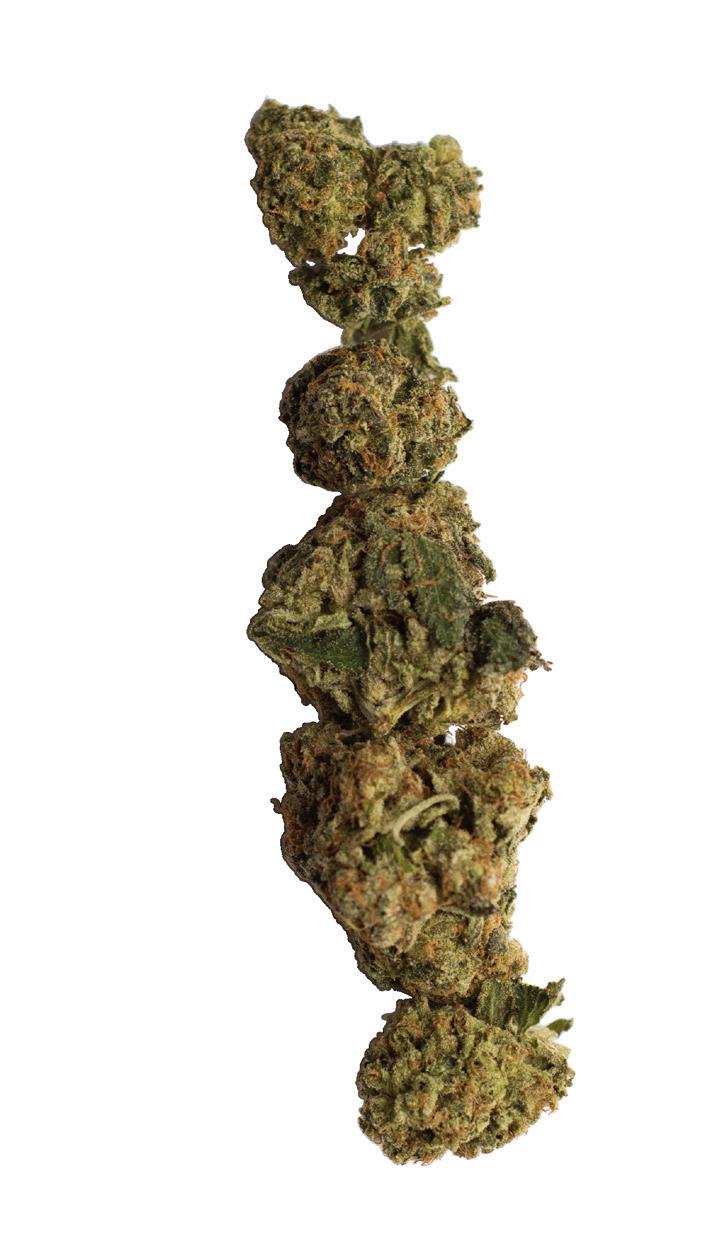

BY CARTER SHERMAN

The 2013 FBI shutdown of The Silk Road, an online black market where users regularly trafficked illegal drugs, sparked the Internet’s imagination and gave rise to other similar operations. Now, ordering drugs right to your doorstep is astonishingly easy with some creativity and connections—just text Lakeside Delivery, a local drug delivery service.

“It’s more consistent and quicker than [an in-person dealer],” customer Jackson* says. If he sends the right message to the right number, a marijuana dealer will arrive at Jackson’s apartment within the hour.

“We were all really sketched out at first, because we were like, ‘That’s probably not the best way. It could easily be a cop. Don’t do it,’” fellow client Tyler says of his first time using Lakeside. But Tyler’s friend took the plunge anyway.

You don’t chill with your dealer anymore. You don’t hang out with the guy when you’re not picking up. You just pick up. It’s purely a business transaction.

– James

“We were like, ‘Well, if he did it, we could all do it,’” Tyler says. “And we’ve all been doing it since.”

Tyler, who regularly bought weed in person before discovering Lakeside in the fall, believes the service decreases his risks of getting caught or hurt because he’s no longer interacting with random strangers.

“It’s unfamiliar and it’s very sketchy,” he says of traditional drug deals. “So this whole ‘They’re coming to me in a place that I know, with people that I know’ makes it a lot more convenient and comfortable.”

This is the real question in the brave new world of online and mobile drug delivery. Which is more likely to get you caught: ye olde drug dealer handshake in a public space, or a cyberspace contract where no one can catch you red-handed but the record is forever preserved?

“You can lose sight of the fact of what you’re doing,” says Riley, a Lakeside customer who’s used the service since September. He’s never bought weed in person and instead

relied on friends to buy for him, he says, because meeting drug dealers seemed too shady. Now, he orders from Lakeside a little more than once a month. “Even though it doesn’t really make too much sense when you think about it, in the moment it seems less risky.”

To see a menu, customers must supply two referrals from people who already use the service. The menu tends to consist of at least three different weed strains, and is accompanied by enough winking emojis to mortify a preteen. These strains are typically available in units of an “eighth”—oneeighth of an ounce or around 3.5 grams of marijuana—and priced between $50 and $60 depending on quality. Lakeside only offers marijuana products, including edibles and liquid THC, the chemical responsible for a user’s high.

Lakeside is open from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. every day, and deliveries usually take from 15 minutes to an hour. The etiquette is like interacting with a pizza delivery guy, clients say.

Customers place an order simply by texting their address. The courier rings the doorbell on arrival while Lakeside simultaneously sends a text alert. It’s up to the customer whether to let the dealer into the house or to buy the drugs outside. Depending on the speed and quality of the delivery, some clients even tip.

To protect its customers’ anonymity, Lakeside never asks for more than first names. But Tyler isn’t so sure that such security measures are enough. “In the back of my mind, I’m like, ‘You know, something could get traced back to me,’” he says. “I’m assuming that nothing, hopefully, will come back to me. But I don’t know.”

Still, none of the clients interviewed say they plan to stop using Lakeside Delivery. The risks seem too small, and the rewards too easy.

“The cops have bigger problems to worry about than me,” Jackson says.

In fact, Riley thinks Lakeside’s operation might be the way of the future. With medical marijuana increasingly legal and punishments for marijuana possession on the decline, he envisions a United States where everyone can order pot with the push of a button.

“What can’t you get straight off your phone delivered to your front door?” he says. “Why not extend that to weed too?”

*Editor’s Note: Names have been changed to protect the identity of Northwestern University students.

Indica – Known for its relaxing high

Sativa – Known for its energetic high

Hybrid – A mix of indica and sativa

2012

Washington State and Colorado legalized recreational marijuana for people 21 years old and up.

2014

Alaska and Oregon legalized recreational marijuana. Alaska’s law took effect in February 2015, and Oregon’s will begin in July 2015.

Stuff your face without emptying your wallet.

BY BO SUH

Northwesterners always hear Chicago is just a quick ‘L’ ride away. But where to begin? Luckily, we’ve compiled this list of cheap and delicious eats around the Windy City, recommended by BuzzFeed and tested by NBN, that aren’t too far from good ol’ Evanston.

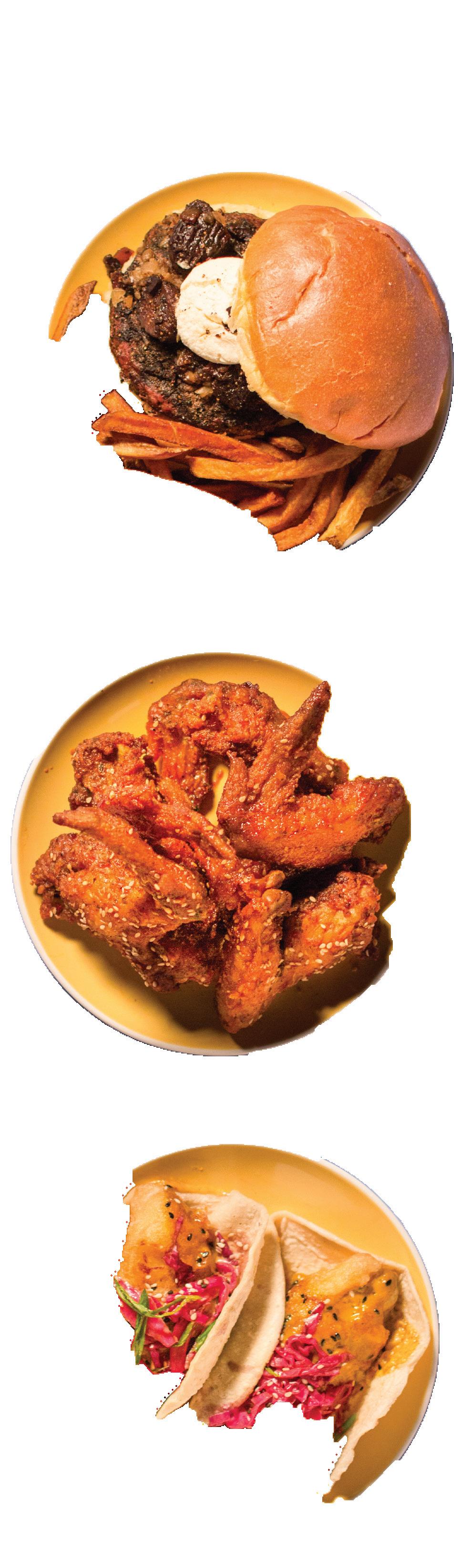

Dish: Whole Jumbo Wings Price: $8.95

There is something beautiful about eating Korean-fried chicken served by a bearded white guy while Kendrick Lamar’s “King Kunta” plays on the restaurant speakers. Could this be the American Dream? The embodiment of the melting pot?

Fried chicken was a popular dish among Korean Americans long before entering the mainstream, and Crisp continues that legacy with more of an American touch. With the exception of Buffalo sauce and Korean “burritos,” the menu remains traditionally Korean albeit with catchy dish names like “Seoul Sassy” chicken wings and the “Original Bad Boy Buddha” bowl. On each table was a container of Gochujang, Korean red pepper paste. The fridge also offers Milkis, a popular Korean cream soda. The only drawback? The five wings were not filling enough—I left feeling like I could have eaten another serving.

If the restaurant in Bob’s Burgers had a real-life equivalent, it would be The Bad Apple. The menu is full of classic American burgers with a twist, like “The Wrath of Julia Child” and “The Land of the Brie.” Without losing the homey, welcoming atmosphere necessary for a good burger joint, The Bad Apple pays a lot of attention to detail, elevating it into a refined and gourmet must-go for lovers of all-American food.

Some of the combinations don’t sound like they would ever be assembled into burger form: The “Edmund Fig-Gerald” combines fig and bacon relish, goat cheese and smoked onion into a unique and tasty burger. Like most other burger joints, The Bad Apple offers a variety of seasonings to go along with its hand-cut fries, including minced garlic, Old Bay seasoning, truffle and spicy chipotle.

Dish: Crispy Fish Tacos Price: $8

Taco embodies Wicker Park’s love for a vintage aesthetic combined with modern sensibility. Everything from the typography on the menu to the mason jars by the water dispenser exudes a nostalgia for 20thcentury America, despite the restaurant’s Mexican roots. The menu also reflects this MexicanAmerican blend: The tacos include complementary ingredients from both cuisines, such as steak and potato hash combined with cilantro and queso.

And it’s inexpensive—only one food item on the menu exceeds $10.

Curt’s Café gives at-risk youth a new opportunity.

BY JEREMY LAYTON

At first glance, Curt’s Café on Central Street may seem like nothing more than a trendy eatery. It is lively and cozy, and the food and coffee are top-notch. To an unfamiliar customer, it’s simply another un-commercialized Starbucks, a neighborhood spot, a quirky hideaway.

But it’s more than that. Even the title, which some might assume is named after an owner, has a hidden meaning. It’s an acronym, standing for Cultivating Unique Restaurant Training.

Of Curt’s Café’s 36 employees, only six work as paid staff members. The rest are 15- to 24-yearolds who have either spent time in jail or faced some type of legal trouble. Some have committed serious crimes, others are homeless,

and many have lost friends and family to gang violence. Almost all of them have been tossed aside by the judicial system, with little hope of finding permanent employment. The mission of Curt’s Café is to take in these young people and provide them with the training they need to find jobs.

“When we incarcerate young people, we make them stop learning,” says Susan Trieschmann, owner and founder of Curt’s Café. “So when they come out four years later, they don’t know how to learn. They have a 14-year-old mentality when they’re 18. It makes them look dumb, but it has nothing to do with dumb or smart.”

The students, as they are referred to, go through a gradual training process that begins at the

dish sink and moves toward the front of the café.

Once comfortable with the working environment, they start making sandwiches and salads, eventually graduating to the counter where they interact with customers and make drinks. At the end of their tenure at Curt’s, usually after around three months, students graduate with a wealth of new skills and the experience they need for a full-time job. Since the café’s opening in 2012, more than 80 graduated students have gone to school or found jobs at a variety of businesses, ranging from Edzo’s Burgers to T.J. Maxx to right here at Northwestern.

Anna Martinez, 19, a student from Evanston, started at Curt’s in mid-February and is now one of the first faces many customers see

at the counter. Although she was skeptical at first, she quickly grew to love her fellow Curt’s employees, who welcomed her with open arms and have taken a liking to her young son.

“They love him,” Martinez says. “It’s wonderful.”

Martinez also says she wants to be a barista once she graduates, and recently got a callback to work at Starbucks.

Trieschmann keeps close contact with her students after they graduate, making herself available in any way if they run into trouble. While some students may fall back into old habits, most won’t. And for Trieschmann, that’s all that matters.

“Our unwritten goal is to have them stay out of prison,” she says. “That’s what we really want.”

Teach me more, teach me more!

BY RICKI HARRIS

Every major consists of course requirements whose CTECs alone fill students with dread. For Weinberg junior Daniel Liu, Economics 310-2 was that class. Luckily for him, he was able to soften the blow by enrolling during the summer.

Whereas high school students view summer school as a threat, many Northwestern students embrace the chance to spend a summer on campus and either catch up or get ahead on their courses. More than 2,300 students elect to stay in Evanston for summer courses each year, which is roughly a quarter of the undergraduate population.

“It was just a decision based on the fact that I switched majors kind of late in the game, and I didn’t want a crazy school year,”

Liu says. “It was easier to get more out of [my courses] in the summer because I got a chance to really understand the material better.”

As an economics and RTVF double major, Liu found that taking Economics 310-2 and Foundations of Screenwriting helped him fulfill prerequisites and ultimately gave him more leniency in the following academic year.

“For a lot of students, it’s a really great time to be able to focus without the pressure to complete work in other courses,” says Stephanie Teterycz, director of Summer Session and Special Programs. “If you want to just be able to focus on a particular area of study, summer is a great time to do that.”

The University offers more than 300 courses over the summer, including intensive language and science sequences, which condense three quarters worth of material into a single, nine-week course.

After finding out that his position working in a lab on campus would only be part-time last summer, Weinberg sophomore Jack Armstrong figured he might as well take a course too. By enrolling in the second-year French sequence, he was able to advance to the 200-level classes during the next academic year.

“It was academically productive and also fun to spend a summer living with my friends and going into Chicago on weekends,” Armstrong says.

But the academic benefits of Summer Session come at a cost that not all students are able to meet, making the decision to enroll difficult. Undergraduate tuition for one credit comes to $3,903 for Summer Quarter 2015, and students must be enrolled in at least two courses to be eligible for financial aid.

“If a student is awarded Northwestern funding for the summer, it will count as one of their 12 quarters of institutional eligibility,” says Angela Yang, director of financial aid operations. “Summer funding is limited and requires a separate application. And as it is the final quarter of the academic year, a student may have exhausted any government or outside resources.”

Financial aid for the summer is limited and thus granted on a priority basis. Precedence is given to those graduating in August, seeking to participate in programs offered exclusively during the summer or making up for a prior quarter of non-enrollment.

Although she referred to summer as “Northwestern’s fourth quarter,” Teterycz says the financial opportunities, or lack thereof, reflect the view of Summer Session as an “add-on.”

Teterycz added that the issue of access to Summer Quarter is “part of a conversation that needs to happen more broadly across the University in terms of the way that it conceives of an undergraduate’s academic experience.”

Tucked away on a glass shelf sits a ceramic jug bearing the likeness of Steve Mullins, the 82-year-old owner of the world’s largest Toby Jug collection. Resting comfortably next to President Obama, the object is a symbolic representation of Mullins’ dedication to the Toby Jug, a historical curiosity most have never heard of.

Toby Jugs are a type of ceramic jug featuring the full-body likeness of an individual. Along with the character jugs, which depict only a figure’s face, they’re a phenomenon that began in mid-18th century England, eventually reaching more than 30 countries.

The museum lies just a 30-minute walk south from Northwestern’s campus, on the corner of Main Street and Chicago Avenue. It houses nearly 8,000 jugs, drawing in Toby Jug collectors from around the globe. Spanning from 1765 to present day, the collection includes both the world’s biggest (40 inches) and smallest (3/8 of an inch) jugs. In between are jugs of all backgrounds, from the political (Karl Marx) to the pop culture (the Mighty Ducks) to the inexplicable (a lizard monk).

The museum is the brainchild

BY TANNER HOWARD

of Mullins, who has developed the collection over nearly 70 years. He bought his first six jugs while in summer camp at the age of 15, bringing them home as a present to his mother.

After making several more purchases while traveling through Canada en route to Dartmouth— where he attended college—Mullins’ collection picked up steam when he returned from military service in Europe in 1956 with a trunk full of jugs.

“That’s when we realized, this was my collection, not my mother’s,” he says.

Today, Mullins works as a Chicago real estate investor and developer, a job that gave him the financial ability to purchase thousands of jugs, some of which are as valuable as $40,000. But his real passion (and the majority of his time) lies in the collection, the history of the jugs, that insatiable collector’s mentality that drives collector’s markets of all kinds. Twenty years

ago, Mullins moved his collection from his downtown Chicago office to Evanston, and in 2005, he moved the jugs to their present address, just north of Main Street, giving the collection room to grow into its current form.

The number of Toby Jug collectors has declined over the past several decades, dwindling to the low thousands, Mullins says. But he remains an active member of the community, traveling every winter to a ceramics conference in Florida. While the market has shrunk considerably in the 21st century, Mullins remains optimistic about the object’s future.

“I’m convinced there will be collectors out there forever,” he says. “They’ve gone on for 250 years, they’re going to go on.”

Mullins estimates that approximately 1,000 people visit the museum each year, learning of the museum via word of mouth. While Mullins’ real estate work helped fund the collection, the museum is

now self-sustaining. As a non-profit, it accepts donations of smaller collections to resell. The museum has also begun to commission its own jugs for sale, including a 12-piece collection of World War II figures (set to be completed this year) costing $5,000.

While Toby Jug manufacturing continued successfully into the new century, the 2011 closure of Royal Doulton, the company that manufactured Mullins’ first six jugs, put the industry in decline. Today, only one manufacturer remains.

Despite the uncertain future of Toby Jugs, Mullins’ efforts have proven instrumental to the jugs’ survival. With the museum bequeathed to his children, Mullins hopes that Toby Jugs will live on long after he’s gone.

“Will it just become something of the past that people will still collect? It’s really hard to predict that,” Mullins says. “I’m hopeful, but I suppose I won’t know the difference.”

Northwestern now accepts more students through its early decision program than ever before.

BY ALYSSA WISNIESKI

“We always wanted a high yield, because the higher the yield, the greater draw the school has. It gives you higher ranking, it gives you more interest with donors and athletes and increases the reputation of the institution.”

-Drusilla Blackman, former dean of admissions, Columbia

“The push to ED has an impact on the senior year. There’s stress on the child to fall in love with the school without taking the time to really figure out if they like every aspect of it or not.”

-Maria Steiner, associate director of college counseling, Hawken School (Ohio)

“During early decision, certain preferences are given to legacies, athletes or kids whose parents are tied to the university.”

-Sung Lee, co-founder at Solomon Admissions Consulting

“I think a lot of students are looking critically at applying early. Also, they may see ED as attractive because it alleviates stress early on.”

-Bari Norman, college consultant at Expert Admissions

UCHICAGO: Early action (non-binding) applicants increased from 3,777 for the Class of 2013 to 11,403 for the Class of 2019

20-30%

The increase in acceptance probability for early applicants compared to those applying regular decision.

1,011 students: 49% of total class

PENN: Early decision

for the Class of 2013 to

for the Class of 2019

# of NU students who applied early

# of NU students accepted early

Students bust the myths they heard before coming to campus.

BY MADISON ROSSI

“‘One hour in the classroom does not actually mean two hours of work outside it.’ I’ve found that to be a blatant lie.”

– Max Zoia, Weinberg freshman

“Tour guides always seems to talk about how massive Tech is...but in the end, who is going to pick NU because Tech has over seven miles of hallways?”

– Colin Wang, Weinberg freshman

“I remember my tour guide saying NU was second best in the nation for food, and now I literally eat Sargent chicken every single day.”

– Emma Felker, Medill freshman

“My tour guide told me she went into Chicago twice a week and, I was like, what? How is that even possible?”

– Ceci Marshall, SESP freshman

“My tour guide said people hang out on the lakefill all the time, but in reality that’s for like a month and then it gets windy and you want to leave.”

– Taylor Sheridan, Weinberg freshman

“I remember my tour guide said that during finals they heard this huge, long, slowly emerging scream. They made it seem like the primal scream was this huge thing, but it’s really not.”

– Maddy Kaufman, Medill freshman

“My tour guide told me that in terms of where you live there’s no divide between north and south campus. But I’ve found that in the winter months especially it was hard to keep up friendships that are a mile apart.”

– Madeline Greene, Medill freshman

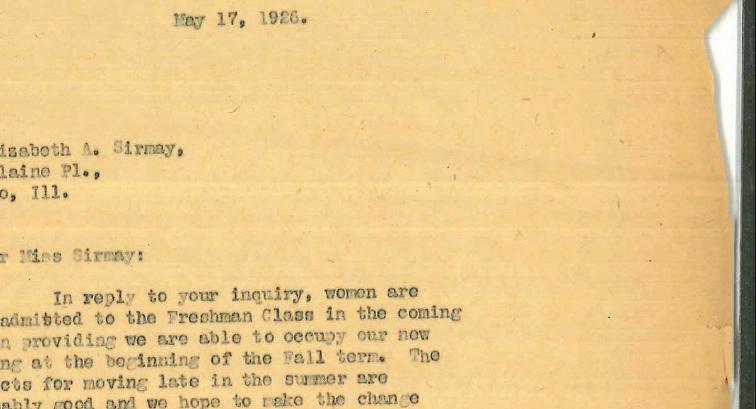

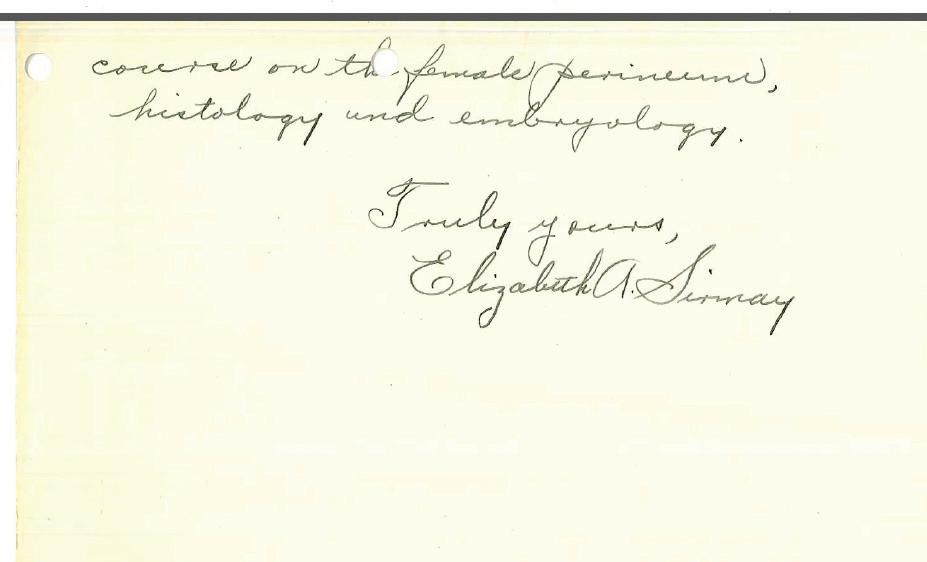

BY ETHAN COHEN

If you want to see everything NU Admissions said about you ... you can’t. Stanford students start the trend of viewing application comments.

I’m not the only one who wonders if Northwestern made a mistake in admitting me. As prospective students, we throw our grades, our activities and our essays into a metaphorical pit and in return receive what feels like the defining judgment of our lives. Earlier this year, inspired by students at Stanford University who publicized a way to see one’s admissions file, I set out to go beyond the “yes or no,” to see what value the University saw in me.

MARCH 17: I finally did it. With great solemnity and sense of purpose, I submitted a form to the Office of the Registrar with a request to view my application and all related documentation.

APRIL 3: I’m still waiting. By law, the school has 45 days to comply with my request, and while I’m not expecting anything before then, the waiting is frustrating. We never hear what people really think of us, and I want to read the unfiltered truth. Were they drawn to my essays or my extracurricular involvement? Was there debate over my qualifications or was I an immediate “yes?”

APRIL 30: Today is the day. After setting up my appointment, I go to the Office of the Registrar and they hand me a manila envelope. My heart sinks as I open it and slowly flip through the photocopied pages. There are no comments, no rubrics, no check marks. They’ve simply given me back my application: just the essays, transcript and

lists of activities exactly as I had submitted them October of my senior year. I waited 45 days for nothing. I wanted to see a critical analysis of my strengths and weaknesses, but instead, my application was scrubbed clean of anything potentially discomforting. While I am disappointed, Al Cubbage, vice president for University relations, says in an email that the school has never kept records. “After a student matriculates at Northwestern, the only admissions records that are kept are the application, test scores and high school transcript. The University does not keep any additional materials. This has been Northwestern’s practice for many years.” This is legal under the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act: A university is not required to maintain any of these records, but to me it still feels like a cop-out.

MAY 2: Upon reflection, I realize that I had gone into this experience hoping for validation, thinking that in some comment I would find my purpose at this school. I did not get that, but I also did not get an empty envelope. At that lonely table in the NU Office of the Registrar I got to see myself with fresh eyes. I saw what is the same—I still love Northwestern because it believes in learning by doing. And I saw what has changed—so much for studying theater in college. Maybe external opinions are less important.

If I was looking for an expert perspective on my value, why do I assume that a guy in the admissions office would be more qualified on the topic than me?

BY ETHAN COHEN

1974: The Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act becomes law. The act requires any school getting federal funding to guarantee student access to education records and the confidentiality of those records.

JAN. 15, 2015: The Fountain Hopper, a student-run newsletter at Stanford University, blasts instructions for how students can access their admissions records, including university notes and comments.

FEB. 23: A Stanford administrator sends an email to those who had submitted requests, asking them to reconsider their decision.

MARCH 2: Stanford students start viewing their records, including scorecards and written comments. The Stanford Daily reports that students have mixed reactions, with some feeling more insecure than others after reading their records.

Stanford freshman Catherine Goetze says in an email that she doesn’t think students should be allowed to view these records, but was glad she was able to nonetheless. “What I saw in my files reassured me that my admission was never a mistake,” Goetze says. “It made me feel like the University really understands who I am, and that they truly wanted me to be a part of the freshman class.”

MARCH 9: The Stanford Daily reports that Stanford no longer keeps admissions records.

Molly has captivated concertgoers, but what is the drug really made of?

BY SARAH EHLEN

Strobe lights pulse in time with the bass of blaring dance music originating from a single laptop on the stage, managed by the young, messy-haired DJ. There are sweaty bodies everywhere, scantily clothed in shorts and tank tops, neon fishnet tights, furry boots and glow stick necklaces. The room is loud, hot and crowded—you’re not really sure why you’re here. You don’t like the music, you hate being so overheated and you don’t know anyone around you aside from a few friends. And then suddenly, like the flip of a switch, you’re floating, glowing and having the time of your life.

But the pill you just took might not be as pure as you think.

CONTINUED

MDMA, commonly known as Ecstasy (pill form) or Molly (considered by some to be a more pure, powder or crystal form), has become almost synonymous with the rising popularity of the electronic dance music industry, which Billboard reported to be worth more than $6 billion. Concertgoers and others use the drug to feel euphoric and more connected to the music.

But as the use of the drug has become more common, so have injuries and even deaths related to its use, as the substance is often laced with harmful chemicals.

The last day of the 2013 Electric Zoo music festival in New York was cancelled after two concertgoers died from using Molly. An honors student at UVA died after using Molly at a concert in September 2013. Last October, 16 individuals were hospitalized for possible Molly use at a Skrillex concert in Chicago. And in late February, nearly a dozen students from Wesleyan University were hospitalized after using the drug.

While MDMA—shorthand for 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine—is synonymous with what users typically call Ecstasy, researchers at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) have “determined that many Ecstasy tablets contain not only MDMA but also a number of other drugs or drug combinations that can be harmful.” As The New York Times explains, “Despite promises of greater purity and potency, Molly, as its popularity had grown, is now thought to be as contaminated as Ecstasy once was.”

“One of the major risks of recreational MDMA use is buying an adulterated substance. It’s often hard to tell, or near impossible to know what is being sold on the streets,” says Irina Alexander, an associate at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), a nonprofit research

dents, and Northwestern students are no exception.

McCormick junior Daniel’s* first experience with MDMA came in a fairly typical setting: a concert in downtown Chicago.

“I had no idea what to expect,” he says. “I had looked into being safe, but I had heard no stories [about the dangers

“IT IS IRONIC THAT A DRUG THAT IS TAKEN TO INCREASE PLEASURE MAY CAUSE DAMAGE THAT REDUCES A PERSON’S ABILITY TO FEEL PLEASURE ON THEIR OWN.”

ize psychedelics for clinical use.

In a 30-year longitudinal study for The American Journal of Psychiatry, researchers found an overall decrease in the proportion of college students who reported use of illicit drugs from its peak in 1978, “with the striking exception of MDMA or ‘Ecstasy.’”

While MDMA is not a new drug, research backs the media’s suspicions about its rising use among college stu-

MDMA: 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-Methylamphetamine

O O H N

After popping the capsule of Molly at dinner before the concert, Daniel didn’t notice any immediate effects for the first several hours of the show. But while overlooking the crowd just before the main act, he and his friends felt a little off.

“It was nothing ridiculous or overpowering, but suddenly it couldn’t have been a more perfect experience,” Daniel says. “We were glowing, smiling, dancing, having great

deep conversations, and a few days after there were lingering positive effects.”

Similarly, Weinberg senior Sarah* first encountered Molly at the annual electronic music festival Electric Forest in Michigan.

“I found a heightened level of empathy and affection that can be really hard to achieve otherwise,” she says.

Though some users report a tie between MDMA and the user’s enjoyment of concerts, both Daniel and Sarah, along with McCormick junior Alex*, say they use the drug for other reasons as well.

Alex, who had battled with mental health issues prior to using Molly, notes the drug’s ability to inspire a renewed sense of self-confidence while helping him discover his potential to connect with others.

“Before MDMA, I had very low self-esteem and had been kinda struggling with depression and anxiety issues,” he says. “But after it, I realized I don’t need to be on a drug to have a deep conversation with someone. I don’t need to wait around for someone to come get to know me. I can do that myself.”

Some researchers recognize the drug’s possible benefits, and they advocate for legalizing MDMA for clinical use in certain circumstances.

“Through clinical trials, we’ve seen that MDMA, combined with therapy, can help treat people who have been exposed to various types of trauma and suffer from PTSD,” Alexander says of the work done at MAPS. “In the near future, we’re starting a clinical trial

SUBSTANCES SOMETIMES FOUND IN MDMA

Amphetamine (speed)

LSD (acid)

2-CB (a hallucinogen also known as 2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromophenethylamine)

Ephedrine (used in “herbal ecstasy”)

Ketamine (a type of anaesthetic)

Aspirin, and other over-the-counter or prescribed medications

Source: ecstasy.org

featuring cancer patients to see if MDMA can help with end-oflife anxiety.”

However, MDMA is still an illegal substance, and not everyone has positive views about its use.

Concerns remain because of the drug’s possible fatal consequences. From 2005 to 2011, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported a 128 percent increase in ecstasy-related emergency room visits among patients younger than 21.

Special Agent Owen Putman of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Chicago Division says MDMA can cause unwanted psychological effects like depression. Further risks that users may face, he says, are similar to those of other stimulant drugs, such as cocaine and amphetamines. He adds, “High doses of MDMA can interfere with the ability to regulate body temperature, resulting in a sharp increase in body temperature [hyperthermia] leading to liver, kidney and cardiovascular failure.”

Not only do MDMA users run the risk of these negative physical consequences, they also put themselves in danger of psychological repercussions. Though the drug can allow users to feel immense pleasure and euphoria, too much of it can inhibit a user’s body from being able to produce these pleasurable feelings on its own. It can destabilize the brain’s levels of serotonin—a chemical that helps regulate mood, aggression, sexual activity, sleep and sensitivity to pain.

“It is ironic that a drug that is taken to increase pleasure may cause damage that reduces a person’s ability to feel pleasure on their own,” Putman says.

But the biggest risk seems to be the harmful substances sometimes added to Molly, ironically making the supposedly pure form of ecstasy into a deadly concoction of additives. The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that such additives include cough suppressants, cocaine, methamphetamines, ketamine and synthetic cathinones, the psychoactive ingredient in bath salts. The NIDA also reports

that combining a mixture of these harmful drugs with other substances such as alcohol or marijuana only increases risk.

Medill sophomore Carl*, unlike other students, recalls his negative experience when trying the drug.

“Ecstasy literally turned off part of my emotional spectrum, which was a genuinely unsettling experience,” Carl says.

Even with these dangers, the DEA reports that they are seeing a significant increase in the use of synthetic drugs overall. Some resources do exist in an attempt to help MDMA users enjoy their high in the safest way possible. For example, DanceSafe, a San Francisco-based non-profit, teams up with festivals and concert promoters to provide safety measures like counseling and information on safe usage.

However, some, like Putman, worry these safeguards do not extend far enough, noting that many users don’t fully understand the damage they are doing to their bodies.

“Laboratory analysis confirms that some Molly samples do not actually contain MDMA and in some instances are comprised of other controlled substances,” he says. “Users often don’t know what it is that they’re putting into their body.”

*Editor’s Note: Names have been changed to protect the identity of Northwestern University students.

NU’s

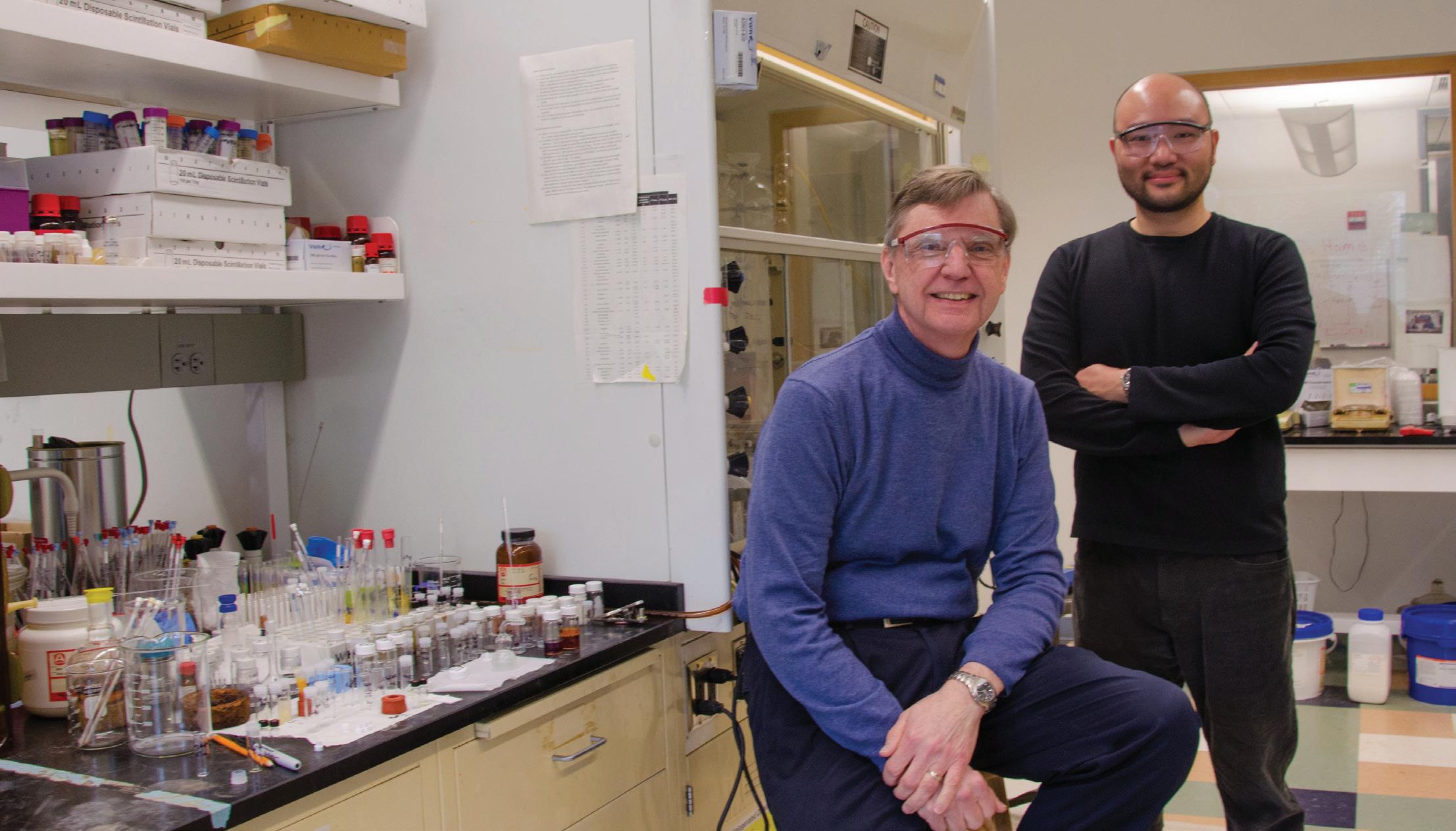

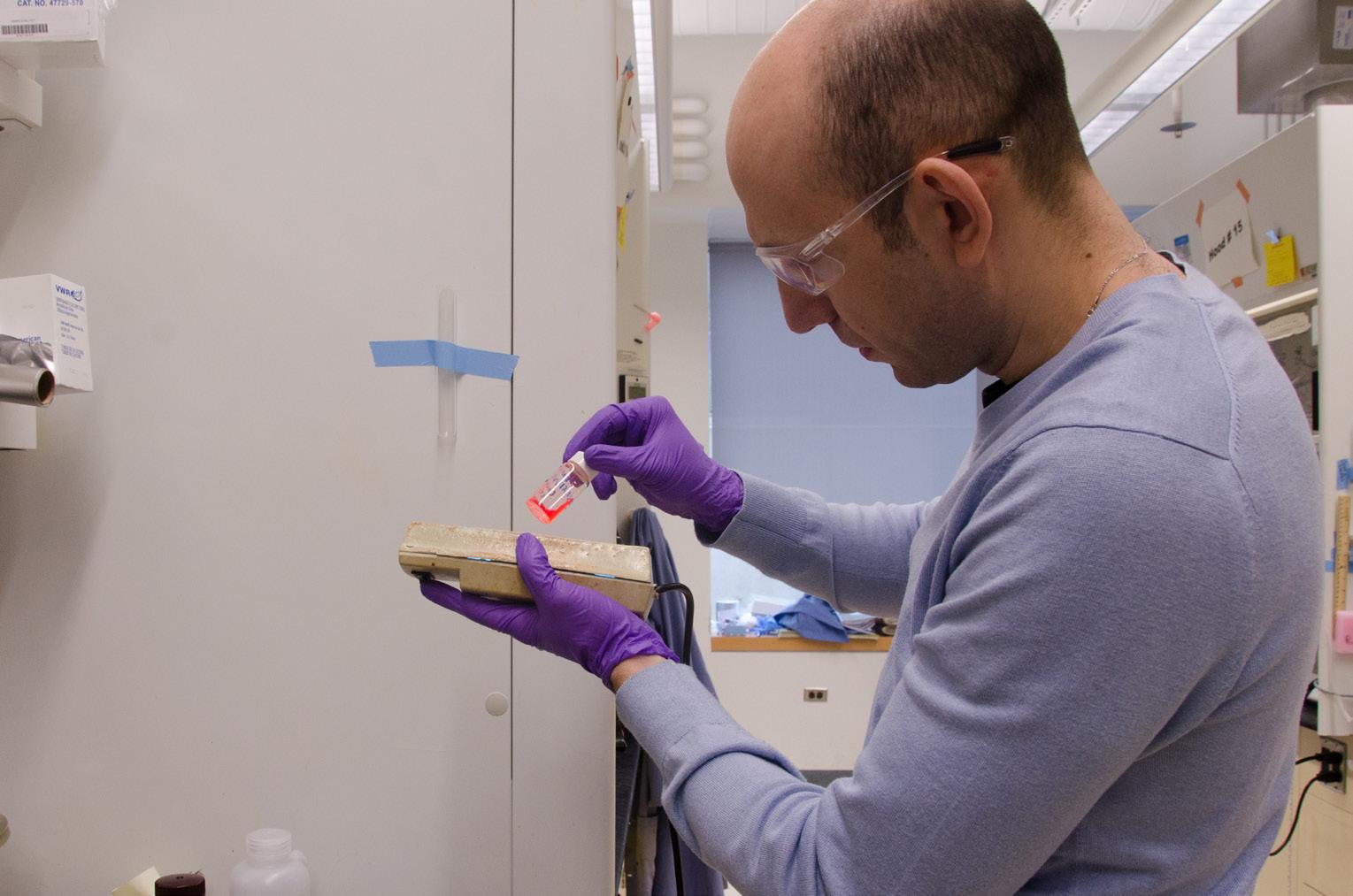

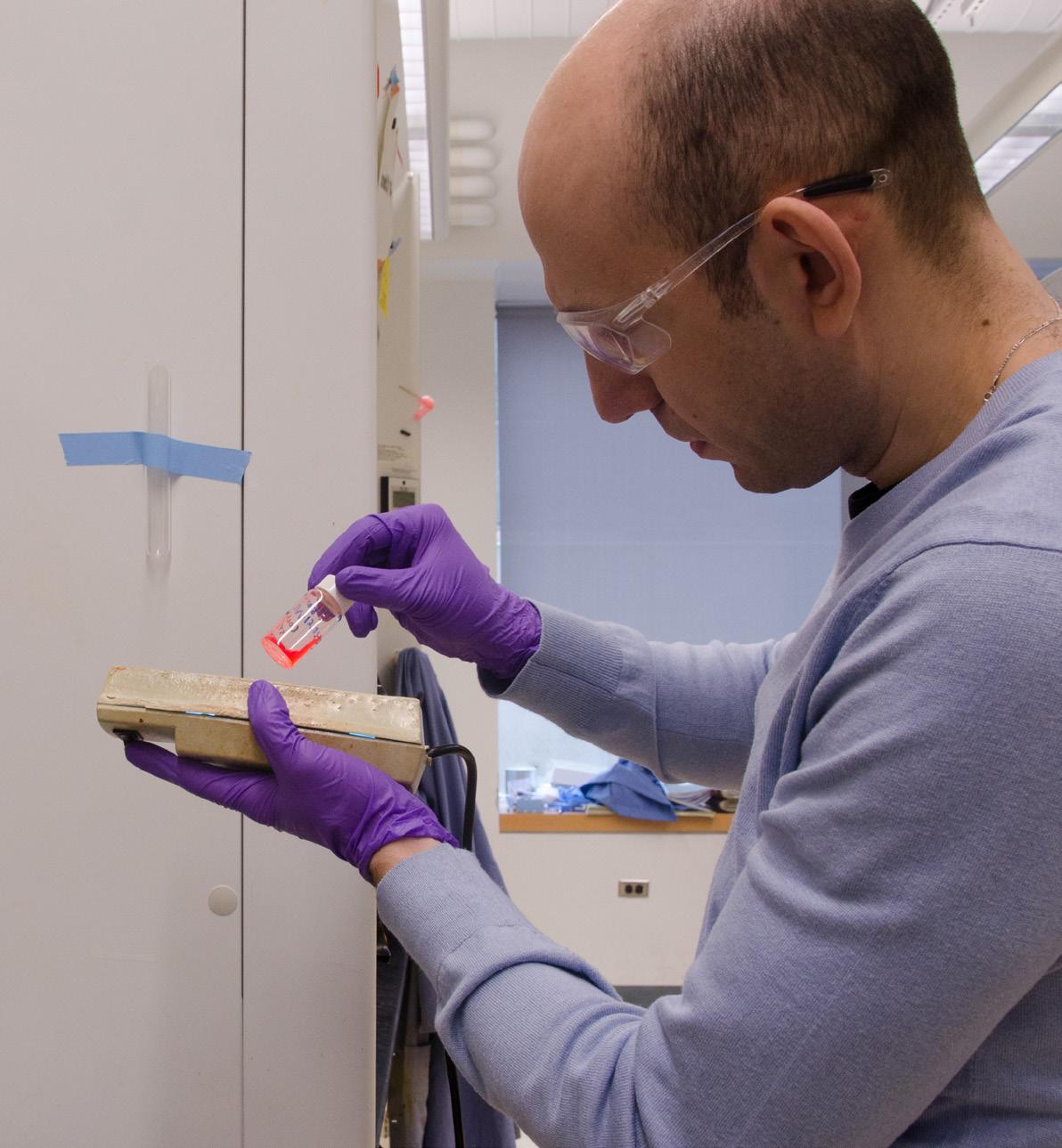

Solar Fuels Institute seeks to change renewable energy worldwide.

BY MORGAN KINNEY

Amid the sprawl of Northwestern’s Technological Institute, a vibrant mural of a mountain vista spans the wall of one unusual room. The sky in the mural is a little too blue, the windswept prairie grass a tad too golden. On a hike through those foothills outside Telluride, Colorado, legend has it that two colleagues hatched the idea for an organization to save the world, or at least power it. If the stereotype is that every great startup begins with a creation myth, Northwestern’s 3-year-old Solar Fuels Institute (SOFI) does not stray far.

SOFI’s vision is simple, in theory, yet difficult to achieve: Take sunlight and store it in chemical bonds. It’s the same idea at the heart of gasoline, only without the million-year lag time. We already convert sunlight to electricity with traditional solar panels, but we don’t have a good way to store that electricity.

Solar fuels like hydrogen, methanol and synthetic gasoline store the sun’s energy in a liquid form that can be centrally produced and distributed. You can burn them in cars, planes, trains, power plants—basically anything powered with fossil fuels, only without the carbon guilt.

Solar fuels might be the environmental Hail Mary the world needs. But nobody is quite sure how to convert sunlight to lamplight with any degree of efficiency.

From its cranny in Tech, SOFI leads a global consortium that brings together universities from Rutgers University in New Jersey to Uppsala University in Sweden. Industry partners include significant players in the energy field, like Total and Shell. Rounding out the team are government-funded research institutions including the Brookhaven National Laboratory, the Max Planck Institute in Germany and the Korea Center for Artificial Photosynthesis in Seoul.

Together, SOFI members share knowledge and resources to solve the solar fuels problem as quickly as possible. This means getting behind solar fuels in every form and in every industry. In a way, SOFI hedges its bets by betting on everyone. Co-Managing Director Dick Co calls these SOFI members his “dream team.”

“It’s not business as usual,” he says. “We’re not here just to put 15 logos together so that we get the next big research grant to do more research. By leveraging, we feel like

we have more shots on goal.”

His idea is to tackle the situation with the mentality and business model of a Silicon Valley startup. Traditionally, academic research is fragmented between competing institutions where scientists are compelled to publish original papers. SOFI seeks to break down these institutional barriers between labs and companies to share knowledge across a broader solar fuels community.

Bill Nye aficionados might recall an episode where the scientist splits water to illustrate chemical changes. This scene is a routine demonstration of electrolysis where an electric current divides H2O into its constituent hydrogen and oxygen. Electrons from a battery pass through the water and attract the positively-charged hydrogen atoms that pull away from the oxygen atom. SOFI aims to do this on a large scale. Once water is split, the hydrogen can be processed for use in solar fuels.

But according to its mission statement, SOFI exists to facilitate the development of an “efficient and cost-effective” solar fuel, and both of those qualifications throw a wrench in any notion of simplicity. Bill Nye’s jury-rigged electrolysis requires an existing energy source, which doesn’t apply when you’re trying to create a sustainable energy future. The tricky part of the solar fuels equation is getting the sun to do the water splitting.

If science does that, the industry can proceed with solar fuels production in two

by Rosalie Chan

broad categories. One option involves directly harnessing the two hydrogen atoms from each split water molecule for compression and use in hydrogen fuel cells. Hydrogen fuel is the carbon-free gambit whose only byproduct is water.

Researchers are aware of the consortium’s efforts to open up channels of communication between industry partners and basic science, but the early stages of the consortium have yet to convince them that practical applications are within reach. It’s a sentiment that’s

SOFI envisions a new future for solar fuels research—a future conducive to those elusive breakthroughs, if only scientists learn to work together.

Another process involves drawing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The same electron transfer reduces carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide, which, in combination with hydrogen, can be processed into methanol or even synthetic gasoline. Both fuels still produce CO2 when burned, but the point is moot because CO2 is drawn from the atmosphere to create the solar fuel.

That may sound simple enough, but it overlooks the decades already devoted to water splitting without success. What’s different for SOFI is the emphasis on collaboration and interdisciplinary thinking, which is exactly the approach some experts recommend for stubborn scientific questions.

SOFI’s business model attempts to bring together this existing knowledge. Still, this sort of collaboration goes against the standard protocol etched into the minds of scientists. Even scientists at Argonne National Laboratory, a SOFI-member institution in Lemont, Illinois, meet the idea of fast-tracking science with skepticism.

not uncommon among scientists focused on basic research.

louder and try harder. SOFI envisions a new future for solar fuels research—a future conducive to those elusive breakthroughs, if only scientists learn to work together. SOFI may physically exist in a tiny cranny of Tech, but its startup ambitions remain larger than life.

“Why bring this startup mentality? Why is industry important? The overarching reason is that we need solutions to mitigate climate change,” Co says. “We’re not here to be the next WhatsApp. We’re here at the highest of levels to save the planet.”

“I think to get that kind of effort there has to both be a huge surge in both academic interest but also commercial interest, and I think that solar fuels is just not quite there,” says Alex Martinson, an Argonne National Labratory chemist. “It’s fair to say that solar fuels is not even niche yet.”

By now Co has heard just about everything the naysayers have to say. His response? Shout

Students at MOSAIC embrace cooperative spirit.

BY SASHA COSTELLO

In a bright yellow room, under a canvas of psychedelic swirls and colors, Weinberg senior Chelsea Phillips lounges on a brown velvet couch with a large skein of pink yarn on her lap, knitting away while a chorus of dishes clatters in the kitchen.

At 7 p.m. the dinner bell rings. Northwestern graduate student Stephanie Ger announces tonight’s dinner—kale with mango and lentil-rice salad—as residents of the three-story house start to emerge from their rooms to settle around a wooden dining table.

Twelve people live in the MOSAIC (Members of Society Acting in Cooperation) housing cooperative’s primary house, known as the “Zooo” not only for its address at 2000 Sherman Ave., but also for the abundance of animal pictures interspersed inside its walls.

Despite MOSAIC’s informal, homey feel, housing cooperatives are legally recognized organizations in which members pool their resources to lower the living costs each person would otherwise incur individually. MOSAIC belongs to the North American Students of Cooperation (NASCO), an organization of over 400 co-ops.

“That [affiliation] is something that hugely differentiates us from a random house of friends,” says Medill senior Leah Varjacques.

The co-op is kind of modeling the society we want to see in the broader world.

– Weinberg senior Kelby Schuetz

A group of Northwestern students who wanted to experiment with cooperative living and to bridge the Northwestern and Evanston communities started MOSAIC in 1998 in a house on Ridge Avenue. In 2004, they relocated to the Zooo.

The whole house gives off the appearance of a shared living space: scraps of paper on the coffee table, painted canvases on the walls and even a poster reading “Big Brother Is Watching You (if you’re into that

sort of thing)” hanging on the common room ceiling.

“It’s a beautiful space of creativity and it’s really messy, but it’s because it’s so organic here,” says Weinberg senior Sasha Lishansky over the clinking of silverware and chatter of housemates. “Everything in here has either belonged to us or has belonged to generations before us. Everything has such a rich history. Everything is made by people like me who have also lived here.”

Lishansky joined MOSAIC Spring Quarter of her sophomore year after seeing a flyer as a freshman. She applied, interviewed and still lives there as a Spring Quarter senior.

Phillips says living in the co-op is more about wanting to join the community than about needing a place to live. Each week, every member is responsible for doing four to five hours of assigned chores, which cover almost every task in the co-op, from cooking dinner to administrative duties.

“The way I think of the coop is kind of modeling the society we want to see in the broader world,” says Weinberg senior Kelby Schuetz. “There is a big focus on sustainability, on socially conscious living ... and actually practicing democracy in our daily lives.”

On Sunday nights, members convene for meetings to discuss what needs to be accomplished within the co-op. They make decisions by consensus, where any individual has the power to veto the group’s idea.

“Just because something is doesn’t mean it needs to be,” says SESP junior Emiliano Vera. “We can

change things according to what is good for the group.”

Meetings start with everyone sharing the highs and lows of their weeks, and end with what the community calls “appreciations,” or little slips of paper on which residents write positive comments about one another anonymously.

Schuetz says these are “nice” and “sometimes necessary after stressful weeks.”

While in theory the co-op is open to anyone, in practice the residents tend to be Northwestern students and alumni. However, next year some young adults unaffiliated with the University will join the community.

Currently, the Zooo’s residents represent majors from across every Northwestern school except for the Bienen School of Music. Engineers make up the largest proportion of the community.

Though under its current egalitarian system the co-op doesn’t have an administrative board,

Schuetz says that it will next year when MOSAIC expands to a second house on Elmwood Avenue, which will function as an independent co-operative with MOSAIC as the umbrella organization that oversees both houses.

For financial reasons alone, MOSAIC’s appeal makes sense.

“In terms of practical matters, we really benefit from economies of scale,” Phillips says. “I’m assuming I would spend much more [living anywhere else].”

Per month, members pay an average of $480 to $510 in rent depending on room size, $121 for common area food and five vegetarian dinners a week, and $50 for utilities. A $15 slush fund sponsors extra expenditures, from home improvements to house parties.

Schuetz says that what attracts people to MOSAIC is the community of open-minded and outwardly loving people.

“It’s a family,” says Northwestern graduate student Torey Kocsik.

A Kemper RA’s pet is more than man’s best friend.

BY ELIZABETH SANTORO

Yapping furiously, a floppyeared puppy scampers around the floor of a Kemper suite living room. She dashes down the hall, cuts back and sprints up the couch and back down to the floor to complete her first lap. After doing a few more “zoomies,” she kisses her favorite roommate.

Darcy, a Chiweenie pup—half Dachshund, half Chihuahua— lives with Weinberg junior Sei Unno in Kemper, where Unno is a Residential Assistant.

Adopted in July, Darcy is an emotional support animal who helps Unno manage her chronic depression.

“My first two years here, it was pretty stressful,” Unno says. “My room kind of became this toxic environment and somewhere I would isolate myself, but now that she’s always there and always very playful, I can’t really do that anymore.”

On a typical day, Unno walks Darcy both before and after classes, during which Darcy, who Unno describes as a “social butterfly,” attracts attention. She’s even become popular enough to have a social media presence: @darcythechiweenie’s Instagram account has 235 followers.

Taking Darcy on walks and feeding her meals regularly puts Unno on a schedule that doesn’t lend itself to the busy lifestyle of many Northwestern

students. But Unno doesn’t mind sacrificing accolades and potential resume-builders.

“She does require a lot of time, so that has made me reconfigure how I spend my time,” Unno says. “It’s more important for me to be happy.”

Unno forgoes other traditional Northwestern experiences as well. She was planning on studying abroad but decided against it so she could stay with Darcy.

“It would break my heart and it would be so stressful to live in a different place,” Unno says.

Securing roommate status for Darcy wasn’t easy. Unno was the first student to request to live with an animal in a dorm, so she had to gain special approval from AccessibleNU last summer. At first, the office asked for more information from Unno because Darcy was not considered a service animal, but rather an untrained emotional support animal.

Alison May, assistant dean of students and director of AccessibleNU, says the department wanted to handle this precedent-setting case correctly and fairly. May and her office had to ensure that all parties involved, including other students, would not be negatively affected, and everyone’s privacy would be protected.

After getting Darcy approved as an emotional support animal, Unno’s next step was solving the

problem of her position as an RA. Because she is an employee of the University, AccessibleNU needed to assess whether Unno’s dorm should be considered her workspace or living space. If the former, Unno would be accommodated as an employee and different rules would apply to Darcy.

Unno was prepared to give up her RA position for Darcy, but AccessibleNU decided that Unno’s dorm was her “living space,” and the Chiweenie became Kemper’s newest resident.

Since Darcy is the first known animal to live on campus with a student, AccessibleNU, Residential Services and the office of General Counsel had to make sure Unno’s suitemates didn’t have allergies. In the future, Residential Services will be permitted to check her room for ticks and fleas.

“When you’re thinking about two beings’ lives you really want to try and make sure you are careful,” May says.

Now a permanent Kemper resident, Darcy’s positive presence is infectious. SESP sophomore Ian Pappas takes Darcy for walks about once a week as a stress reliever.

“Nothing gets her down. She’s 100 percent energetic 100 percent of the time,” Pappas says. “It’s a good time to step back and take everything into perspective. Take a dog’s view of things.”

Students seek to engage in meaningful dialogue about one of Northwestern’s most contentious issues.

BY JULIA CLARK-RIDDELL AND MEDHA IMAM

When Associated Student Government Senator and Weinberg sophomore Isaac Rappoport voted in favor of the Northwestern Divest resolution, he voted with the knowledge that he would lose friends.

Rappoport had watched the NU Divest movement—which advocated for the University’s Board of Trustees to divest from any holdings tied to corporations that profit from business operations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory—ignite campus through the cold winter months.

Student groups involved with the debate who used to collaborate on events and meetings severed ties. Pro-divestment and anti-divestment banners alike were reportedly vandalized in the night, and some students say relationships and friendships ended at the discovery that one person had attended meetings for the “other side.” Accusations of racism and anti-Semitism punctuated debates and social media posts.

When a resolution in favor of divestment came before the floor of the student Senate on Feb. 19, Rappoport thought the vote was going to be close—and he was right. In some areas of the room sat supporters of NU Divest. In another group sat NU Coalition for Peace, a group of student organizations who opposed the resolution, including members from Wildcats for Israel, NU Hillel and J Street U Northwestern. Senators and students filled the room. After five hours of heated debate, the resolution passed in favor of divestment, 24-22, with three abstentions.

Months after the resolution passed, the events of the Senate debate continue to polarize campus.

“I received a lot of flak—written, vocal, emails, texts—people telling me that I betrayed my community, that I betrayed my religion,” Rappoport, who identifies as Jewish, said after the vote. “A lot of the leadership in my community turned its back on me for a period of time.”

In the aftermath of the resolution, some advocates and opponents of divestment continue to place blame on one another for employing rhetoric that caused rifts in the student body.

“I think that the opposition

[to NU Divest] was a reactionary movement,” says Weinberg sophomore Marcel Hanna, co-president of Students for Justice in Palestine. “We launched divestment and the next day, there was the opposition. It wasn’t like they were striving for a coalition for peace before this started.”

As the debate ensued, student perspectives ranged across the spectrum, and students leaning toward the center found themselves feeling silenced.

“It was either fall in one camp, stay there and fight for it or don’t say much of anything at all,” says Haley Hinkle, a Medill junior who spoke with students responding to the debate as she prepared to run for ASG president. “Campus was a powder keg, ready for the wrong thing to light it and explode.”

Hinkle says that as a campus leader, she was worried about alienating one side of the conversation by siding with the other.

“I didn’t feel comfortable ex-

tine videos lacked context and was not of equal quality to the Israeli videos.

“Intentions can only get you so far,” says Weinberg senior Emily Schraudenbach, who attended the event. “It became political. It’s important for the community to know how angry and how legitimate the anger of the Palestinian voices was. As I understood it, everything they said was legitimate and didn’t go up against what J Street U wanted to do.”

Northwestern Coalition for Peace formed in January out of a belief that the divestment movement had oversimplified the conflict. The group urged the student body to “change the conversation” and “oppose NU Divest,” according to the Coalition’s Facebook page.

With a diversity of perspectives on the issue, polarization often seems inherent in debates about Israel and Palestine. For some students, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

IF STUDENTS AT NORTHWESTERN ARE UNABLE TO FOSTER A MEANINGFUL DIALOGUE WITHOUT ANGER, FEAR OR POLARIZATION, WE CANNOT EXPECT A SOLUTION ON A GLOBAL SCALE.

Chetan Sanghvi (CAS ‘86)

pressing my opinion,” Hinkle says. “What I felt was that there was no way to win. There was no way to come out of it, especially from a campaign perspective, and not feel the anger directed at me from some student communities.”

Medill junior Tal Axelrod, cochair of the student group J Street U Northwestern which supports a two-state solution with a pro-Israel, pro-Palestine and pro-peace platform, says that while the group has seen increased membership in recent months, he thinks arguments in the middle were often left unspoken during the debates.

In an attempt to remedy that problem, J Street U Northwestern held an event called Side By Side on April 22 that intended to discuss both the Palestinian and Israeli narratives. However, some student attendees criticized J Street U Northwestern for delegitimizing and misrepresenting the Palestinian narrative, saying that the Pales-