From counterculture to carnival

Chronicling the history of the country’s largest student-run music festival.| pg. 50

Wildcat side hustles

Students are finding creative ways to cash in on their hobbies. | pg. 6

A male-dominated field

Exploring the gender dynamics of intramural soccer. | pg. 23

NORTH BY northwestern SPRING 2025

print staff web staff

EDITORIAL

PRINT MANAGING EDITOR Eleanor Bergstein

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITORS Sarah Lin, Mitra Nourbakhsh

SENIOR PREGAME EDITOR Olivia Teeter

ASSISTANT PREGAME EDITORS Marissa Fernandez, Sofia Hargis-Acevedo, Sarah Jacobs, Emi Levine

SENIOR DANCE FLOOR EDITOR Sarah Lonser

ASSISTANT DANCE FLOOR EDITORS Hazel Hayes, Seychelle Marks-Bienen, Emma Richman, Helen Ryan

SENIOR SPOTLIGHT EDITORS Laura Horne, Jamie Neiberg

ASSISTANT SPOTLIGHT EDITORS Gavin Fisk, Gabe Hawkins, Clara Martinez

SENIOR HANGOVER EDITOR Heidi Schmid

ASSISTANT HANGOVER EDITORS Sarah Brown, Ava Wineman

CREATIVE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Leila Dhawan

ASSISTANT CREATIVE DIRECTOR Ilse von Heimburg

DESIGNERS & ILLUSTRATORS Sofia Hargis-Acevedo, Sarah Brown, Sachin Chawla, Carter Chau, Jessica Chen, Kyra Doherty, Chase Engstrom, Sarah Jacobs, Isabella Millman, Lena Rock, Adelle Rubinchik, Marley Smith

PHOTOGRAPHERS Sarah Brown, Isabella Millman, Yujin Tatar

FREELANCERS

Greta Cunningham, Sophia Gutierrez, Caroline Killilea, Desiree Luo, Georgia Rau, Ruby Sadikman

COVER DESIGN BY LEILA DHAWAN

MANAGING

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mya Copeland

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Sammi Li

MANAGING EDITORS Indra Dalaisaikhan, Ava Hoelscher

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Jezel Martinez

DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION EDITORS

Gabe Hawkins, Sammi Li, Jezel Martinez

SECTION EDITORS

NEWS & POLITICS EDITOR Leilani Diaz

ENTERTAINMENT EDITORS Angela McKinzie, Mary Amelia Weiss

LIFE & STYLE EDITOR David Samson

SPORTS EDITOR Mariana Bermudez

INTERACTIVES EDITOR Gracie Kwon

FEATURES EDITORS Lindsey Byman, Maya Mukherjee

OPINION EDITOR Cassandra Brook

CREATIVE WRITING EDITOR Haley Kleinman

ASSISTANT CREATIVE WRITING EDITOR Ava Paulsen

AUDIO & VIDEO EDITORS Olivia Teeter, Dallas Thurman

GRAPHICS EDITOR Ilse von Heimburg

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

EDITORS Cydney Waterman, Sara Xu, Madelyn Yu

CONTRIBUTORS Mariana Bermudez

CORPORATE

PUBLISHER Alice Tao

AD SALES Christine Shin, Jane Yu

OUTREACH Cydney Waterman

EVENTS CHAIR Cydney Waterman

Readers, Dear

After a cold and gray Evanston winter, I wanted our spring magazine to embody the changing colors and fresh energy of the new season. Our fantastic staff spent six short weeks reporting on the ground, editing stories in the MFC and designing the beautiful pages you are (hopefully) about to flip through.

The Pregame section kicks off the issue with a look at some Northwestern students’ clever ways of making money on the side. We also highlight a local Evanston cat rescue shelter and undergraduate courses focusing on important current events. In Dance Floor, we reflect on the history of the storied Bobb Hall, set to undergo renovations next year. We also dive into the rules of intramural soccer that keep female players on the field.

Our cover story is a retrospective on the history of Dillo Day, from the first countercultural festival to this year’s carnival. In the 1970s, students started the annual festival in response to tumult in international news. It’s hard not to draw parallels between this and our other Spotlight stories, which explore how the University is grappling with a similarly uncertain moment.

This spring, $790 million dollars of federal funding to Northwestern were frozen. In Spotlight, we break down the implications of this freeze and reflect on broader conversations about higher education and academic freedom.

I can’t thank my incredible staff enough for all of their hard work. They poured so much into these stories, going to far corners of campus and the surrounding community to bring new perspectives and ideas to the pages of our magazine.

As we worked on this magazine, the color returned to Evanston. Like spring itself, this magazine is meant to be fun, uplifting and thoughtful. It focuses on stories of joy, resilience and action. I hope each of these pieces will feel encouraging to read, or teach you something new. Enjoy.

Sincerely,

Eleanor Bergstein

6

8

12 Kitty corner

10

Let’s get physical In the hot seat

13

That’s what (s)he said Side hustles

PHOTO BY ISABELLA MILLMAN

Side hustles

These Wildcats find creative ways to cash in on their hobbies.

WRITTEN BY RUBY SADIKMAN // DESIGNED BY SACHIN CHAWLA

Every Sunday morning, Communication second-year Piper Miller sets up rows of plastic press-ons, sparkling charms and a rainbow of nail glitter along her wooden desk. Then she opens the door to greet a new client — one she only knows through Instagram DMs.

“It’s really cool seeing people light up when they notice their nails in their peripheral vision,” Miller says. “Especially the ones I put a lot of time and effort into, they feel like a wearable art piece, and I’m glad other people feel the same way about them.”

Miller has been painting nails since Fall Quarter after falling in love with the intricacy of the craft this past summer. She serves as many customers as possible throughout the week while balancing schoolwork, offering anything from painting natural nails to designing complex press-on sets. Each customer can take up to three hours of Miller crouching over her tiny canvases, but she charges less than Evanston nail salons with her personal rate ranging from $40 to $70 per person.

Nail artistry is just one of many side hustles run by Northwestern students wanting to make money outside of traditional work. From dorm room cosmetology to designing groundbreaking apps and running comedy open-mic nights in an attic, these students are finding ways to turn their interests into profit.

“I’ve always heard people say if you’re good at something, don’t do it for free,” barber and Weinberg first-year Nathaniel Chavez says. “And it gives me a little rush in my day — I think all passion projects are meaningful in a type of way.”

Since getting a bad haircut this summer and realizing he could fix it himself, Chavez has been running a makeshift barbershop for his short-haired classmates in need. Charging just $15 per cut, he’s

making a quick buck and expanding his social circle in the process.

“I’m an introvert, so it breaks that shell of mine to talk to other people and get to know people well and just reach out to others in that way,” he says.

The deeper impact of side hustles is not lost on others in the community, including Communication secondyear Eliza Fisher. When her close friend brought up the idea of a crochet balaclava — a cozy hooded head covering — Fisher decided to try it out, not only to enhance her friend’s style but also as a way to maintain her own well-being.

“I got sick over the summer, and then I really had to learn how to prioritize selfcare as opposed to getting work done,” Fisher says. “I needed one thing to ground me in taking time for myself. I feel like making balaclavas is the way to do that.”

Fisher has since expanded her clientele beyond close friends, bringing all varieties of balaclavas to the student body — or at least those who commission

her through her Instagram account, @balaclavasby.lize. While her creations were originally priced as an “IOU,” Fisher is now charging around $40 per design, enough to cover both the time she puts in and the various brightly-colored yarns she uses.

While Fisher’s side hustle is more casual, some others are just gaining traction. For the past few weeks, Weinberg third-year Mateo Garcia-Bryce and his roommates have been running a Monday night comedy show out of their offcampus attic on Pratt Court. What started out as a group of friends throwing jokes around has evolved into a full-on comedy production with seating, beverages and even a spotlight for the featured comedian on stage. Attracting upwards of 85 people and filling the room in under five minutes, the aptly named “Prattic” has become a Monday night mainstay.

“I think people like this because, one, it’s in a super cool venue and, two, it’s super laid-back, very lowkey,” Garcia-Bryce

COURTESY OF PIPER MILLER

says. “We encourage essentially everyone to do it.”

This event has reached many corners of the student body, from Greek life to performance arts groups and other inspired side-hustlers. With a newlyinstated weekly cover fee of $3, “Prattic” has always been about bringing people laughs during the school week as opposed to making major profit.

“We didn’t really feel like charging people when we were also having to worry about doing our own sets,” Garcia-Bryce says. “We wanted to make the barrier of entry as low as humanly possible.”

For Garcia-Bryce and his roommates, “Prattic” is less about financial gain and more about fueling a stifled creativity. Miller, on the other hand, is exploring what it’s like to monetize an interest. She was further convinced to pursue her nail art after hearing from a PhD student whose research focuses on the use of masks throughout theater history— taking a love of art and turning it into a degree.

“Even if your passion is so singular and focused, you can find a way to turn that into an education and a career,” Miller says.

While getting a side hustle off the ground can seem intimidating, there are many ways to find success. For one, Weinberg fourth-year Mo Moritz and a few of his friends launched the app

“I think all passion projects are meaningful in a type of way.”

Nathaniel Chavez Weinberg first-year

“Polo” in February, creating a platform for Northwestern students to advertise their various hustles and services. From seniors selling their couches to Moritz’s own personal chef services, the app allows almost anyone to turn their passions into income.

“Our main priority is just proving scalability, proving proof of concept and providing something that’s going to add value to the community,” Moritz says.

“Students want a source of income in college but can’t really commit to a full or even part-time job because of how sporadic the college schedule is.”

Like many other students in the side hustle community, Moritz recognizes this platform is more than just a pastime for his crew, even with graduation looming.

“I just feel like our work isn’t done here yet,” Moritz says.

COURTESY OF MATEO GARCIA-BRYCE

COURTESTY OF NATHANIEL CHAVEZ

UKitty corner

Paws and Claws fosters cats and community.

// DESIGNED AND PHOTOS BY

pon entering Paws and Claws Cat Rescue, the shelter’s slogan , “Where cats become family,” welcomes patrons into the store. Toys, blankets and wooden perches line every wall and window. Staff and volunteers float between four rooms equipped with food, water and litter boxes. Some felines rest inside white cardboard boxes decorated with hearts, clouds and cats hand-drawn by children of Evanston.

“I wanted to create a space that I was truly excited to be part of, and I wanted to not only save the lives of cats but, in a way, impact people as well,” Paws and Claws founder and Evanston resident Ashlynn Boyce says.

Boyce founded Paws and Claws in May 2020 after she noticed a “void for companionship” across the community. The shelter aims to support overlooked cats suffering from abuse, neglect and overpopulation in municipal shelters, which are required to take in all animals regardless of resources or space. The organization started small and without a physical location. Since then, Paws and Claws has saved the lives of over 2,500 cats.

“I wanted to not only save the lives of cats but, in a way, impact people as well.”

Ashlynn Boyce Paws and Claws founder

“We didn’t have a facility, so we relied on foster families,” Boyce says. “And a lot of those folks that started with us five years ago have continued to foster ever since.”

The program eliminates the financial restraints of fostering by providing the cats’ food and medical care. Today, the shelter is supported by over 350 community volunteers, who helped the rescue center reach over 10,000 volunteer hours in 2024. Volunteers are tasked with cleaning the cats’ spaces and playing with them.

Paws and Claws emphasizes the individual identity of each cat, giving every feline a unique name — “Gold Dust Woman” and “Doc Marten,” for example.

The shelter offers many opportunities for community involvement including children’s birthday parties and kitten yoga. It also offers 90-minute-long rentals for other events hosted at the shelter.

For the past two years, Evanston resident Diana Morrow has almost always had a foster cat in her care, totaling 44 rescues. She loves to learn their quirks, favorite foods and toys, but her favorite activity is napping with the fosters.

“I get to take a nap, and I’m doing some good because I’m socializing that cat and helping them learn to snuggle, and that makes them a better companion for their future adopter,” Morrow says.

When Paws and Claws settled into its Chicago Avenue location in 2023, Morrow was excited a cat rescue shelter had opened within walking distance from her house. She soon began fostering while working from home with her own three cats. Now, after leaving her job, she has picked up a regular volunteer shift at Paws and Claws, where she often visits her former foster cats.

Evanston resident Rosa Durand started volunteering in November 2024 and became interested in fostering, particularly after seeing the cats who could not find foster homes. After arriving at the shelter, cats must be isolated as certain diseases can take weeks to detect. Additionally, the cats must be neutered and vaccinated, a process that starts at six weeks of age at the earliest. New rescue cats without a foster home often live in treatment room cages during this time.

Durand noticed cats would get overwhelmed in these cages, which encouraged her to take in fosters of her own. Her first fosters were a pair of bonded cats, while another was a skittish cat who would hide in small spaces.

Paws and Claws’s impact reaches far corners of the country. One cat, 7-yearold Nessa, comes from Louisiana, where it is particularly difficult for sickly cats like her to find homes. The shelter helps support cats affected by hurricanes in southern states like Florida, in addition to having strong partnerships with Midwestern states including Indiana and Michigan. To facilitate these cross-country rescues, the shelter collaborates with several volunteers to deliver the animals.

As a nonprofit, the organization credits local residents and volunteers for its success over the past five years.

“People come because they’re excited about the cats,” Boyce says. “But ultimately they stay here and continue to come back because they’re excited about the community that’s been built within these four walls.”

Let’s get

physical

Pregame takes on SPAC workout classes.

WRITTEN

BY

PREGAME EDITORS // DESIGNED BY LENA ROCK // PHOTOS BY

Spring Quarter means warmer weather, and suddenly, the walk to Henry Crown Sports Pavilion and Aquatic Center (SPAC) becomes less daunting. SPAC offers a range of unique exercise classes throughout the week, some of which you may have considered trying before. Well, fear not: Pregame has dabbled in its specialized offerings, from the infamous BODYPUMP class (yes, the caps are necessary) to the more laid-back Sunrise Yoga. Now, you’ll have no excuse to avoid that class your friend always tries to drag you to.

Emi - Sunrise Yoga

For the rare early birds at Northwestern, Sunrise Yoga is just the class for you. While I had to budget at least 15 minutes in the morning to accommodate the trek from Allison Hall to SPAC, watching the sunrise as I walked north was one of the highlights of my experience. Upon arrival, each participant grabbed a mat and two blocks before setting up a place for themselves in the studio. Donna, the instructor, started the class off in

fold. I had only minimal experience with yoga prior to this class and was surprised by how tiring the poses were to hold. My leg muscles tightened during the warrior two sequence and I was noticeably sweating by the end. The class’s difficulty made Shavasana at the end feel all the more rewarding. I left the studio feeling ready for the day ahead, before returning to my room and falling back asleep for two more hours.

Sofia - BODYPUMP

If you enjoy pushing your body to its limits, I suggest pushing yourself in the direction of BODYPUMP. As the title suggests, this class hits every major part of the body: chest, biceps, shoulders, legs, glutes, calves and core. I recommend showing up early to set up your station before the class fills up — space dwindles fast in Studio B. Participants grab an elevated mat, a couple dumbbells and a weighted bar and weight plates, which you can switch out depending on the exercise. As we started with the warm-up, I made the unfortunate assumption that the class would not be that bad. However, as the hour progressed, I quickly realized how wrong I was. The class used fastpaced cardio and toned my muscles at the same time. I will admit, walking up the stairs was difficult after the workout.

For anyone looking to get into workout classes — or even for experienced pros — SPAC’s Pilates Barre class is the perfect workout. Upon entering the studio, most participants grab a mat, a set of weights and a pad to place underneath. It’s best to get there early as the room fills up quickly and some supplies are scarce. The class started with various upper body exercises like planks and push-ups, before moving to core, back and leg exercises. Halfway through, we took our mats from the middle of the floor and moved them to the walls and barres, which help dancers maintain their balance for certain movements. At the barres, we did a series of plies, incorporating ballet positions before ending the class with stretches against the wall. Even though I came into the gym with minimal energy, I left feeling refreshed and ready for my evening in Periodicals.

I honestly didn’t know what to expect going into this class, and that was definitely the way to approach it. When the teacher waltzed in two minutes after class was supposed to begin, I knew I was in for a chaotic and entertaining ride. We hit four types of latin dance — Bachata, Salsa, Cha-cha-cha and Merengue — and wasted no time starting the first move. The teacher slowed down the steps for us, her feet moving in a series of rhythmic shuffles and taps. But issues arose when the tempo quickened. I knew I was not great at dancing, but this experience was truly humbling — maybe more stumbling. Nobody in there was great at dancing either; we all laughed to ourselves. By the end, my heart was beating fast and I was sweating. However, this class was more about having fun than building biceps. I would highly recommend you try it out as a break from the stress and to let loose.

Olivia - Latin Dance

Marissa - Pilates Barre

In the

hot seat

Northwestern classes tackle some of today’s most relevant issues.

WRITTEN BY MARISSA FERNANDEZ // DESIGNED BY SARAH BROWN

Students anxiously refresh CAESAR as the seconds tick down to their course registration time. They try enrolling in their top choices, only to find courses which were open seconds ago are now completely filled. This is a scene that plays out every quarter. While many of Northwestern’s classes cover subjects that prepare students for their future careers, some of them focus on important issues relevant to students’ day-to-day lives or current events. With the flurry of executive orders and policy changes from President Donald Trump’s second administration, subjects ranging from international economic policy to immigration and artificial intelligence have moved to the forefront of many student’s minds. North by Northwestern explores some Spring Quarter classes that center current events and hot topics.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution guarantees rights such as birthright citizenship and equal protection under the law. This course offers students an in-depth look into the 1868 amendment and how the Supreme Court has interpreted its meaning, both expanding and limiting the rights it delineates. Students also study how social movements have shaped the amendment’s significance.

While many recent headlines concern Fourteenth Amendment rights, this subject matter is always pertinent, says associate professor of instruction of Legal Studies Joanna Grisinger, who coteaches the course with professor of History Kate Masur.

“I really want students to feel like, when they read the materials, when they’re reading the sources, that they can understand this too,” Grisinger says. “And that they can keep up with current debates, and that they have a role to play in current debates.”

Why do people do good? The answer to that question is explored in a quarterlong journey through psychology, philosophy and economics in this introlevel class. Students learn different ways to evaluate impact and success so they can assess the effectiveness of real-world charities and nonprofits.

As the Trump administration makes cuts to U.S. foreign aid, “Doing Good” explores how people use available resources and information to decide on charities to support. Throughout the quarter, the class will narrow down a list of 34 charities to one that will receive a $20,000 donation.

Dean Karlan, the former chief economist for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), taught an upper-level version of this class in previous years. However, he says he wanted to create a class that was open to students with a variety of academic backgrounds and combined economics with ideas from psychology and philosophy.

“When you put them all together, they do end up providing some guiding lights for how to think about what charities are particularly effective or what we can do with our volunteer time,” Karlan says.

While Northwestern students may use ChatGPT to help them answer a math question or explain a complicated topic, the reach of artificial intelligence isn’t limited to academics. This class explores the role of artificial intelligence in international security: how it can be used to protect against cybercrime, but also how it can be used by cybercriminals. This is only the second year “AI and International Security” is being offered, and it is open to all students.

McCormick second-year Brock Brown is taking the class to satisfy an elective requirement for his major and because of his general interest in AI and machine learning.

“I just wanted a firmer grasp on how everything is connected and what we could potentially do in the future to … make sure people don’t use [AI] in bad ways,” Brown says.

That’s what (s)he said

Steve Carrell has got big shoes to fill.

WRITTEN BY EMI LEVINE // DESIGNED BY CARTER CHAU

For many college students, graduation brings an onslaught of questions as they ask what they want to do and who they want to be. Commencement addresses, given by a successful alumni or influential individuals, offer graduates guiding principles and lessons as they take on life after college. As graduation season quickly approaches, here are four of the most memorable speakers in Northwestern’s history and words of wisdom they shared.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg spoke to Northwestern’s graduating class of 1998 while serving on the United States Supreme Court. She joked that she chose Northwestern because it was the only place where she “could be cast in the same role as Robert Redford and Bill Cosby,” two other notable past speakers. Her speech centered around the fight for gender equality in professional and academic settings. One student called Ginsburg’s address “definitely the best part of the ceremonies,” The Daily Northwestern reported in June of that year.

“I continue to gain encouragement from the example of those who, despite great odds, have persevered in the pursuit of justice, and who, like you, have chosen to make a difference.”

— Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1998)

Two months before former President Barack Obama’s visit, The Daily printed a column by Elaine Meyer (Weinberg ‘06), who called upon the then-state senator to challenge the senior class in his commencement address. Standing in Ryan Field on a muggy June day, with a commanding voice and charismatic demeanor, Obama responded to Meyer’s request. He based his speech on themes of personal responsibility, perseverance and empathy, while also situating it in the social and political issues of the time.

“There’s a lot of talk in this country about the federal deficit. But I think we should talk more about our empathy deficit — the ability to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes; to see the world through those who are different from us.” — Barack Obama (2006)

Many Northwestern alumni say they wouldn’t be where they are today without this university. For Seth Meyers (Speech ‘96), that statement is literal — the LateNight host told graduates his parents met in a Northwestern poetry class. Meyers focused his 2016 commencement speech on the friendships he made at Northwestern. As one graduating senior told The Daily, “whether it is in medicine, law, engineering, consulting, whatever career path we may choose to follow, I hope we can use our Northwestern experience and find the same hard-earned success that Seth has found.”

“You’ve been surrounded by the best for the last four years and there’s no better favor you will do yourself than continuing to do that. Every success I’ve had has been thanks to the people around me.” — Seth Meyers (2016)

For most students, Northwestern dining halls are a place of mediocre food, long lines and the occasional existential crisis. Not many would describe them as places to meet your future life partner, but for actress and Northwestern alumna Kathryn Hahn (Speech ‘95), that was exactly what happened. Hahn met her husband in the former Hinman Dining Hall as first-years. In 2024, she returned to Northwestern to address the graduating class. In her speech, she acknowledged that life often encompasses contradictory emotions and situations and thus encouraged graduates to adopt a “both/and” mindset.

“While it is true that at this very moment, yes, there is unimaginable pain and suffering in this world, it is also true that you and your class are going through something together that is oncein-a-lifetime and worthy of celebration.” — Kathryn Hahn (2024)

The cat’s Mee-Ow

Dance Floor

Bobb the building

Marketing for a cause

A maledominated field

Washington to Wildcat

A round of applause

Passport to progress

15 19 21 23 26 28 30 32

Drawing back the curtain

The cat’s MEE-OW

51 years of Northwestern’s premier comedy group.

WRITTEN

AND DESIGNED

BY SOFIA HARGIS-ACEVEDO

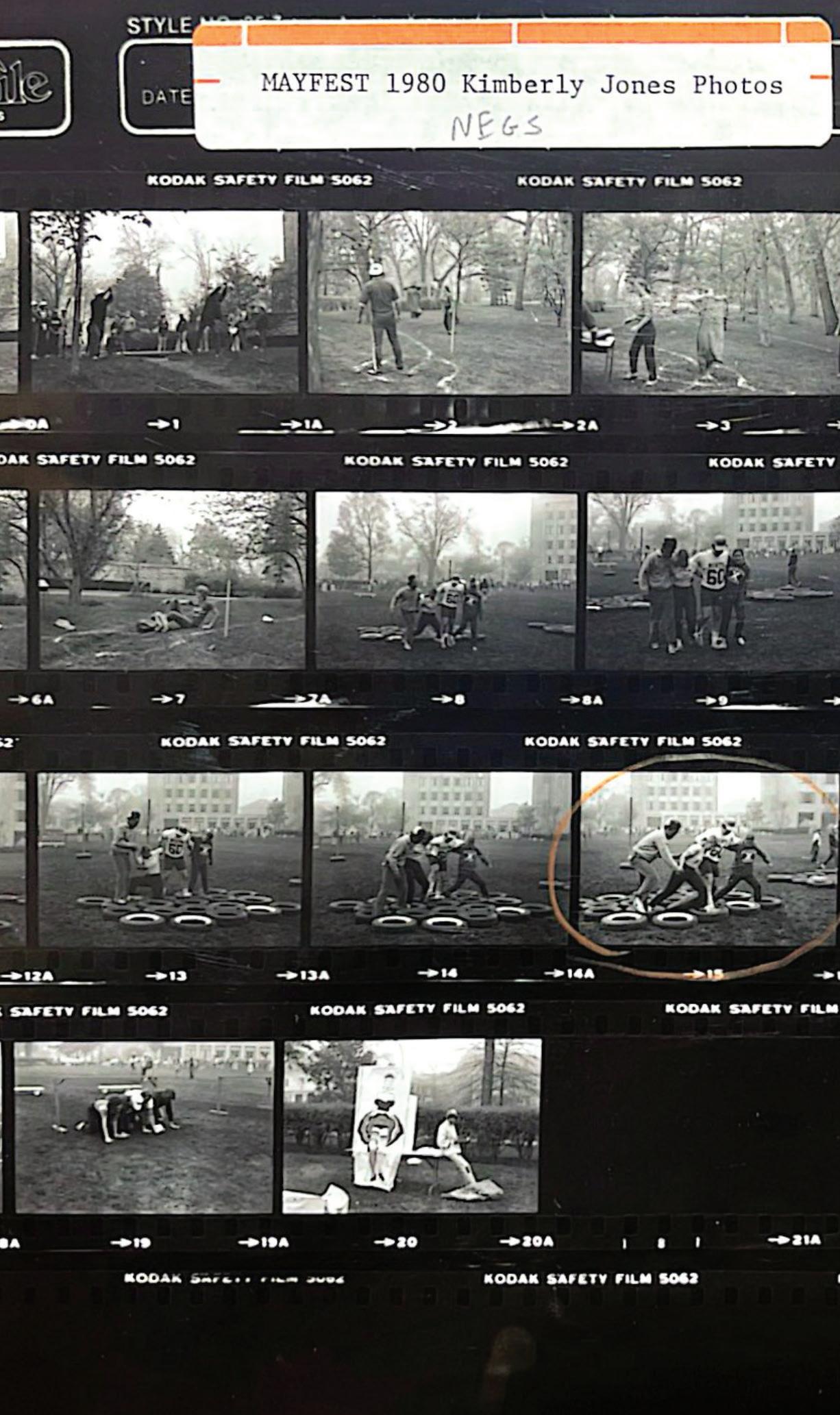

PHOTOS FROM UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

It’s the spring of 1974. The Watergate scandal is in full swing. The American people are questioning the security of democracy. And what does a group of Northwestern students do?

They perform comedy skits about the whole ordeal.

Richard Nixon accepts an Academy Award in one scene. In another, a congressman sings a song about Watergate to the tune of a The Music Man number. The night of April 12, 1974, the comedy group Mee-Ow made their debut at the McCormick Auditorium.

Mee-Ow describes their act on Instagram as “one-third sketch, one-third improv and one-third rock & roll.” Over the past 51 years, the comedy group has gained prestige and popularity among students, faculty and beyond. Their ranks have included a string of big-name cast members like Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Seth Meyers and Kristen Schaal. From Mee-

Ow’s big premiere to their most recent show, North by Northwestern embarks on an archival journey through the history of the iconic student-run improv and comedy group.

1974: The beginning

The first ever Mee-Ow show, Just In Time, ran the weekend of April 12-14. While the annual act now includes short-form improv and a live band, the first show consisted of 40 written skits — some in the form of a musical, some zeroing in on dramatics, but all comedic. The original cast consisted of 39 students. Over the years, as the group learned how to produce a successful show, that number has dwindled to the single digits, but it has remained completely student-run.

Prior to Mee-Ow’s existence, the musical theatre group Waa-Mu was the only big student-led production on campus. Founded in 1929, the group had established its legacy at the school. However, after leaving WaaMu’s performance the previous year unsatisfied by the content of the show, Paul Warshauer (Speech ‘76) and Josh Lazar (CAS ‘75) produced Mee-Ow as an “alternative” to Waa-Mu.

Mee-Ow’s debut was met with backlash. Students appreciated how Mee-Ow’s producers were aiming to create a less selective show than Waa-Mu; however, many believed the show itself was poorly executed at times. A string of The Daily Northwesternarticles were published after Mee-Ow’s opening show, written by the then-president of Orgy of the Arts — an organization that produces many studentrun shows. These pieces revealed tensions between the cast and crew and a lukewarm reception frm students.

“It’s amazing that people sat through that garbage,” said one observer, according to The Daily.

After six years of perfecting their craft, Mee-Ow began to establish themselves in the theatre department. In 1980, future Emmy Award winner and Saturday Night Live cast member Julia Louis-Dreyfus joined the cast and performed in their Ten Against the Empire show. Louis-Dreyfus made it onto Mee-Ow her first year, which, if you know your Mee-Ow facts, happens very rarely.

Not only was it uncommon for freshmen in general to be accepted, but it was even more uncommon for a freshman woman to make it in the group. Paul Barosse (Speech ‘80), one of Louis-Dreyfus’s fellow cast members, says the Mee-Ow group was impressed by her talent from the start.

“It was pretty much a boys’ club, and you really had to stand out to make it as a girl,” he says.

After juggling both school and being a cast member of The Second City, Chicago’s renowned improv and sketch comedy group, Louis-Dreyfus left her junior year at Northwestern when she got the role of a regular cast member on SNL.

1996: Seth Meyers

By 1996, Mee-Ow had been established at Northwestern for 22 years. Seth Meyers (Speech ‘96), former SNL cast member and host of NBC’s Late Night With Seth Meyers, was an RTVF major with a passion for comedy.

Meyers auditioned for Mee-Ow three times, starting as a freshman, before getting in his senior year. He said that finally becoming a cast member changed the trajectory of his future career.

“I loved it so much that I remember thinking that I, for the first time in my life, knew what I wanted to at least try to do and that I would try to do it until someone told me I didn’t have to do it anymore, or I wasn’t good enough to do it anymore,” Meyers told The Daily in 2017.

Meyers’s rise to fame in the world of comedy has only added to the success of Mee-Ow, as he has credited the group multiple times in his fruitful career.

1999-2000: Kristen Schaal

The 2000 show Mee-Ow On Ice featured Kristen Schaal (Speech ‘00), who is now an actress, comedian and writer. The group opened the show with a song about how old and run-down Shanley Pavilion is, throwing in jokes about how it was made with pieces of the cross and was the first building to cross the Atlantic Ocean over 30,000 years ago.

Not long after her performance in 2000, Schaal moved to New York to continue pursuing her comedy and acting career. She has appeared in many different television shows such as Bob’sBurgers and Gravity Falls and wrote for popular shows including How I Met Your Mother and Ugly Betty.

Schaal returned to Northwestern in April of 2024 for Mee-Ow Fest, when the comedy group celebrated their 50-year anniversary. In an Instagram post, she reminisced on good times with a caption stating, “Thank you for a wonderful 50th reunion Northwestern Mee-Ow! It was great to be surrounded by creative and funny people of all ages. This show means a lot. @lizcackowski and I still have our 1999 hoodies, baby!”

“It was a really surreal moment to be like, ‘whoa, we’re playing this big stage. It’s for us.’”

Sam Marshall Communication fourth-year

2024: the Mee-Ow Band Takes

on Dillo Day

After a successful winter of shows, the Mee-Ow Band — which was established in 1984 as a musical accompaniment to the comedy sketches — was eager to keep their momentum going. Taking the next step as a music group, the band decided to compete in the 2024 Battle of the Artists, a competition for student musicians and groups to secure a slot performing at Dillo Day. The Mee-Ow Band secured the win, ready to take to the big stage.

They had never played a gig of this caliber. Communication fourth-year Sam Marshall, Mee-Ow’s music director and guitarist, says a crowd this large was a big step up.

“We rehearsed our set to death,” Marshall says. “It was a nerve-wracking situation, but we just practiced and practiced.”

When the day came to perform, Marshall says he was so nervous that his hands weren’t moving how he’d like them to. But playing in front of family and friends with his bandmates by his side, Marshall had the performance of a lifetime.

“It was a little scary, but looking across this stage and seeing my bandmates was comforting,” he says. “We were all a little nervous, but then that kept us tight and on top of it. It was a really surreal moment to be like, ‘whoa, we’re playing this big stage. It’s for us.’”

In its 51st year, Mee-Ow is still producing sketches and improv. The group performed twice this Winter Quarter, during week four — The MeeOwgic School Bus — and week eight — KnivesMee-Owt. Even after half a century, the group still finds ways to evolve.

Usually, only the opening sketch ties with the theme of the show, but this year Communication fourth-year and co-director Brenden Dahl suggested including a closing sketch based on the theme that also calls back to sketches throughout the show. Co-director and Communication fourth-year Shai Bardin hopes this format continues in the years to come.

“Adding that level wraps [the show] into a bow,” Bardin says. “That part of it was very satisfying and exciting, artistically.”

For the past 50 years, Mee-Ow has been produced and sponsored by the Northwestern Arts Alliance (AA). In recent years, the two groups’ goals began to diverge, leading Mee-Ow to split away from AA and file their own producer petitions for the upcoming 2025-26 season. While the split marked a critical change in the partnership of Mee-Ow and AA, Dahl says there is no animosity between the two groups.

Mee-Ow has touched the lives of many students over the years. From current members to famous alumni to the group’s creators, Mee-Ow has become a part of the University’s rich arts culture.

“[Mee-Ow’s accomplishments] in and of itself [are] really exciting and really drew me to Mee-Ow, drew me to Northwestern,” Bardin says.

The group has no plan to slow down. Though Mee-Ow has no more performances lined up for this school year, Bardin is excited to see where Mee-Ow’s talent brings them in the coming years.

“Even though you’re students doing a student show, the actual feat that you’re doing, the thing that you’re putting on is so impressive, is good, is entertaining,” Bardin says. “That kind of legacy is really awesome.”

“[Mee-Ow’s accomplisments] in and of itself [are] really exciting and really drew me to Mee-Ow, drew me to Northwestern.”

Shai Bardin

Communication fourth-year

Can Northwestern fix it?

WRITTEN BY EMMA RICHMAN // DESIGNED BY KYRA DOHERTY

It’s Friday night in Bobb-McCulloch Hall, and as usual, it’s loud: music blasts down the hall, freshmen mix miscellaneous beverages in their dorms, girls in tiny tank tops flock to the frats in single-digit weather. There’s rarely a silent moment in the dorm that never sleeps.

renovations over the next two years: the Bobb side first, then McCulloch, which will remain open while Bobb is under construction.

no Henry Crown Sports Pavilion and certainly no Ryan Fieldhouse. Bobb was right on the lakefront.

“In my day, Bobb-McCulloch was considered to be one of the better dorms to try to get into,” Thompson says.

For better or worse, Bobb is a Northwestern classic. As one of the largest dorms on campus, it houses over 400 students. But starting this summer, the ivy-covered and mold-ridden 70-year-old dorm is getting a long-overdue makeover. The building will be partially closed over the next two school years, Residential Services announced in February.

For many, it feels like the end of an era. Thousands of students have passed through Bobb’s cinder block halls over the past decades, and many say living there was a formative experience.

“Living in Bobb is something you love while you’re doing it, and then you never want to do it again,” says Medill fourthyear Saul Pink.

Pink lived in Bobb his freshman year — or technically, he lived in McCulloch.

The two dorms, conjoined since 1980, will both be undergoing

These renovations have been a long time coming. In 2015, Bobb was slated to be demolished in 2020. But the dorm is still standing. The upcoming construction is aimed at improving the student experience, according to the February announcement. Renovations include adding kitchenettes and laundry rooms to each floor.

While the renovations may change how it looks and operates, Bobb — and its culture — are here to stay.

Ride or die

Bobb has always been a social hub, a place where people meet their best friends and sometimes even future spouses. While current students flinch at the outdated facilities, it wasn’t always considered one of the filthier dorms on campus.

When J.T. Thompson (CAS ‘85) lived in Bobb as a sophomore, the dorm was coveted. He could walk right out of the building and be on the beach. Back in 1982, there was no parking garage,

Aside from the great location, Thompson remembers Bobb being a very community-centered dorm. He often had friends come over to his room and hosted cocktail hours. Today, he’s still in touch with the friends he met in Bobb.

The dorm’s social culture remained alive and well throughout the ‘80s. In February 1989, Bobb’s executive board began publishing monthly newsletters called The Bobb-McCulloch Connection Within colorful blue, yellow and pink pages, the board advertised upcoming events such as Tuesday movie nights, dorm Olympics and a booze cruise on Lake Michigan.

The March 1989 issue encouraged residents to attend social events to foster “a close-knit community.” It also announced some important news: “198889 Bobb-McCulloch shot glasses on sale for just $2!” Even then, Bobb residents liked to party — that reputation remains.

When Pink lived in McCulloch in 2021, he spent many late nights in the “McLounge,” what he and his friends called the McCulloch fourth floor lounge. He says it was the best freshman dorm experience he could have asked for.

Pink formed bonds with his hallway

Living in Bobb is something you love while you’re doing it, and then you never want to do it again. ”

Saul Pink Medill fourth-year

Room for improvement

Walking into a Bobb bathroom, one might find vomit, hair dye staining the sinks or a meal from Lisa’s spilled all over the floor. Residents say it’s a true wild card.

McCormick first-year and McCulloch resident Roselyn Attipoe says the filth is a result of students neglecting the already worn-down facilities.

If Bobb was nicer, Attipoe says she thinks students would treat it better.

For many, the Bobb bathrooms are its most problematic feature. With so many people sharing the space, the facilities often don’t meet students’ needs.

“There was a solid two week period during Fall Quarter when [hot water] was a hit or miss thing, or we had two showers blocked off out of the three,” Weinberg first-year and McCulloch resident Reed Zimmerman says.

For Zimmerman, the laundry situation

“I wouldn’t cook there,” Zimmerman says. “You might get food poisoning.”

Both Zimmerman and Attipoe say the new kitchenettes will be a game changer for future residents.

While Pink agrees that renovations will certainly improve the quality of life, he also says the dorm’s less-than-ideal cleanliness is part of its charm and even its culture.

“People bond over being somewhere that’s not nice,” Pink says. “If Bobb was a nice, fancy dorm, like Lincoln or Shepard, I don’t know if the same atmosphere would be there.”

The master plan

With Bobb closed next year, Northwestern will re-open 1835 Hinman, recently renovated to house over 200 students with expanded kitchenettes and communal lounges. Located across Sheridan Road from East and West Fairchild, Hinman closed in 2018 for renovations.

The Bobb construction is part of a 2018 plan that also outlined potential 2025 renovations of Sargent, East Fairchild and West Fairchild.

Residential Services was expected to release its new Housing Master Plan report during Winter Quarter, but has not published it yet. It contains a plan for the next 10 years of on-campus

housing and dining, created with input from over 400 students, faculty and staff, along with thousands of student survey responses, according to the Residential Services website.

“Completion of the plan has been delayed as we work to ensure that it provides viable guidance in the current budgetary climate,” a University spokesperson told North by Northwestern in an email.

According to the University, the main goals of this new plan are to improve the condition of residential housing and dining, and enhance student community and belonging. It’s more comprehensive than the 2018 plan, as it also includes visions for dining and graduate housing.

As for the Bobb renovations, a Residential Services official says construction on the Bobb side is set to be complete by Fall 2026 and McCulloch by Fall 2027. Besides new kitchenettes and laundry rooms, it’s unclear what exactly the renovations will improve.

At the end of the day, many residents agree: Bobb isn’t as bad as people say.

“I’ve met some of my closest friends in Bobb,” Zimmerman says. “Having them be only a couple doors down is really, really nice.”

Next year, the dorm’s hallways will lie vacant as construction gets underway. Incoming freshmen will have to find their pregames elsewhere.

Marketing for a cause

How a group of IMC graduate students are changing the Chicago nonprofit landscape.

WRITTEN BY GRETA CUNNINGHAM // DESIGNED BY CHASE ENGSTROM

Laura Salgado showed up for her volunteer shift at one of Nourishing Hope’s Chicago food pantries expecting to be put to work moving frozen meals and wheeling carts of groceries. She did not expect to hand out flowers. However, seeing customers’ reactions to the florals showed Salgado exactly what “nourishing hope” can look like. One parent exclaimed that they could bring their daughter flowers, and another visitor eagerly took a bouquet for their mother.

Nourishing Hope is a hunger relief nonprofit that provides resources for food, mental wellness and social services across Chicago. For the last few months, Salgado has been visiting nonprofit organizations like Nourishing Hope to create promotional content as the External Communications Director of Northwestern’s Cause Marketing Initiative (CMI).

Each spring, CMI takes on 15-20 nonprofits in the Chicago area and provides them with pro bono marketing services. CMI is run entirely by graduate students like Salgado in Medill’s Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC) program who leverage their skills to develop and implement everything from brand strategy to stakeholder analysis to public and media relations. They work with organizations that, despite their essential role in the community, are often underfunded and lack adequate resources to expand their reach.

According to the 2024 Nonprofit Marketing Trends Report, most nonprofits only have one or two staff members devoted to communications. 71.9% of surveyed nonprofits identified limited budgets and resources as challenges they foresaw in achieving marketing goals, according to Feathr, a nonprofit digital marketing service. Research by Tapp Network and TechSoup consultants found that less than half of nonprofits have a digital marketing strategy in place.

That’s where CMI comes in. In January, the student executive board reaches out to local nonprofits with information about the program and a “Request for Proposal” through which the organizations can detail their marketing goals.

The program has grown from seven or eight clients in 2008 to 20 in 2025, and about one-third of the projects return year after year. This cycle, interest was so high CMI had to turn down a few projects. Advisor Chris Cahill, an IMC faculty member, says it’s a metric of the program’s success.

“I look at the number of clients that come back that next year and want to continue working with CMI,” he says. “I see that as a way to measure the value they’re deriving from these projects and working with the students.”

The board then matches four or fiveperson student teams with nonprofits. IMC students rank their choices based on how the organizations’ missions resonate with them and how the desired

project aligns with their goals and experience.

Once the board has finalized the projects and teams, they host a kickoff event where organizations get to meet the students they’ll be working with and start building a network with other nonprofits in the area.

“CMI teaches communicate you to with empathy.”

Mallika Mehta IMC graduate student

“It’s really one thing to communicate with organizations over email,” IMC graduate student and Program Director Jimmy He says. “But to put a face to these organizations and see how excited

COURTESY OF LAURA SALGADO

these nonprofits are to be working with students, even though we’re just students ... to see us grow and help us help them was really rewarding for me.”

Because the IMC program is only 15 months long, the students in CMI turn over every year. This year, over 85 students are participating in it — about 60% of the IMC cohort. Cahill says the high level of involvement shows how eager students are to work with nonprofits.

For many, the work allows them to feel engaged with the community. Cahill saw CMI as a way to give back to the neighborhood that had contributed so positively to his undergraduate experience at Northwestern. Salgado wrote about her interest in CMI as part of her IMC application. Mallika Mehta, team leader for one of the program’s projects and an international student from Delhi, India, hoped the experience would help her acclimate to her new city.

“[CMI] shows direct impact to see if the skills we’re trying to gain from the program are being used or are being applied well,” Mehta says. “It was one of the most meaningful ways I could learn to become a marketer, but it was also a lot about becoming a responsible part of the community I’ve just joined.”

Mehta’s team is doing a brand management project with Ten Thousand Villages, a fair trade retailer in Evanston. Their goal is to help the shop reach their target audience and raise consumers’ awareness of Ten Thousand Villages’s unique mission to ensure their artisans are paid a livable wage, support traditional cultural arts and work with marginalized communities.

“[Marketing] is a challenge for small businesses,” says Hannah Wymer, the store manager at Ten Thousand Villages.

“We wear a lot of hats, and it’s a few people doing all the things.”

Ten Thousand Villages thought it was a good time to embark on a marketing collaboration because they recently moved business districts — MainDempster to Downtown Evanston — and wanted to increase outreach in their new neighborhood.

“Some of my team members are coming to IMC straight from undergrad, so it was quite interesting to see how they have developed their leadership, their client communication skills and also figure out the right balance between business objectives and nonprofit missions,” Mehta says.

The CMI students consulting for Ballet Chicago are working to increase the company’s engagement with a target audience — in this case, a younger demographic. They’re hoping to build the ballet company’s social media presence with behind-the-scenes and day-in-thelife of a dancer segments.

Emily Hsueh, the team leader for the CMI group working with Ballet Chicago, says she has loved watching their plans come to life on the organization’s Instagram stories and website.

“Being able to do our work and then put it into the real world is fantastic,” Hsueh says.

To ensure a successful project, teams break up their goals into specific

deliverables scheduled across the span of the program, adjusting their objectives as needed based on routine communication with their clients. On May 30, the student teams and nonprofits will come together for a wrap-up party where teams have the opportunity to present the strategies and plans they’ve developed and any results they’ve seen.

To evaluate which strategies are yielding results, the Ballet Chicago team pays attention to click-through rates on marketing emails, Instagram and ticket links. Sharyn Pulling, Ballet Chicago’s general manager, says their ticket sales are higher this year than last and that they are on track to exceed their current sales goals.

In addition to implementing the conceptual skills students develop in the classroom, the projects are an opportunity to practice problem-solving. Nonprofits’ small and busy staff, the short 12-week timeline and budget constraints require teams to stay flexible and creative.

“[CMI] teaches you to communicate with empathy. You are not just selling products or services anymore. You’re trying to inspire action,” Mehta says. “As a team, we have learned how to stretch our emotional intelligence and think beyond business, think about how our marketing initiatives can help the community at large.”

COURTESY OF LAURA SALGADO

A male-dominated field

Exploring the gender dynamics of intramural soccer.

WRITTEN BY SEYCHELLE MARKS-BIENEN AND HAZEL HAYES // DESIGNED BY SARAH JACOBS

Tillie Freed was recruited to the competitive division of winter intramural (IM) soccer by a member of the pickup soccer league she played in on campus. The Medill first-year was initially confused by the request.

“I play fine at pickup but I’m not doing anything crazy, so I was like, ‘Why does he want me to play on his team?’” Freed says. “Then I asked, ‘Is there a gender requirement?’ and that’s how I figured it out.”

Every Tuesday night of Winter Quarter, students file into the Henry Crown Sports Pavilion (SPAC) and make their way up to Ryan Fieldhouse. Typically, the Fieldhouse is filled with NCAA and club athletes, but once a week, it opens up to a different group of students: IM soccer players.

These indoor 5v5 IM soccer games provide a unique opportunity for men and women to compete together — similar to the spring outdoor 11v11 IM soccer season that kicked off in early April. Using Northwestern’s online IM sports portal, students can sign up by adding friends to their rosters and selecting a time slot to play in either the competitive or recreational league based on skill level.

However, the winter season has one major rule difference: a gender requirement.

Compared to the “open” spring league, which has no restrictions on who can join, the winter league is COREC, meaning teams must consist of both men and women. The official IM handbook requires each team to have a minimum of two women on the field at all times, a rule

that has been in place ever since winter IM soccer was introduced about four years ago, according to Northwestern’s director of IM sports Ryan Coleman.

The rule is designed to foster a more inclusive and fair playing environment. This year, many female players noted that, though well-intentioned, the rule is not effectively encouraging women to participate. Rather, many are brought to IM soccer for the purpose of filling a quota.

Weinberg first-year Rosa Saavedra was recruited by male players looking to fulfill the gender requirement. While getting lunch at Sargent Dining Commons, she overheard the students next to her talking about the soccer video game FIFA, and inserted herself by arguing about formations.

“It was the most wanted I’ve ever felt I had so many people ask me to play with them.” Tillie Freed Medill first-year in my life.

The male students were impressed by her knowledge of FIFA and soccer in general, Saavedra says, and immediately asked her to join their team. Saavedra hadn’t heard of the IM program before, but as a former captain of her high school’s varsity soccer team, she was intrigued by the opportunity.

“I looked at [my friend], and I was like, ‘I’ll only do it if she does it,’” Saavedra says. “I didn’t think she was going to, but then she was like, ‘We’ll both do it!’”

Once on the field, Saavedra and other players noticed a lack of women in the program. If a team can’t fulfill the twowoman requirement, they are forced to compete with fewer players. If just two women show up, they must play the whole game with no substitutions and can experience overexertion.

Because of this, female players are in high demand during the winter season.

“Honestly, it was the most wanted I’ve ever felt in my life,” Freed says. “I had so many people ask me to play with them.”

Similarly, McCormick third-year and women’s club soccer captain Nicky Williams, who has played IM soccer since her freshman year, says she has gotten a text “every weekend” for the past three seasons asking if she can play in a game.

Some players, such as Medill first-year Natalie Gordon, enjoy the extra playing time. But there are times when she feels it inevitably hinders her performance level.

“I think it did get tiring at some points, which posed a challenge,” Gordon says. “I don’t want to be bringing the team down because of this rule.”

Despite the lack of female players, many believe the rule is a necessary

“There is transactional-ness to it.” some sort of

Tillie Freed Medill first-year

component of the COREC league. Many female players say they would not have been introduced to IM soccer if it were not for the gender requirement.

“It is kind of unfortunate, but that is the truth,” Weinberg first-year Jordan Stuecken says. “I am really glad that I did IM soccer, but I feel like if they didn’t have that rule they probably just would have formed a team from the guys they know.”

Just like Freed and Saavedra, Stuecken wasn’t initially planning on playing but joined after receiving a text from a male friend inviting her.

Freed also says she began to question the intention behind the encouragement expressed to her and other female players.

“Obviously they need me, so they have to be nice to me to some extent,” she says.

Coleman agrees that without the gender requirement, there would be significantly fewer women participating. For example, there is currently no gender rule in the spring outdoor season, and because of this the league is “essentially a men’s league,” Coleman says.

The idea of playing on a maledominated field can be off-putting for many female players.

“There’s obviously a strong biological difference; I’m not going to be able to beat them in a foot race,” says Williams. “I think it’s hard because a lot of the girls are just intimidated when they are going up against guys who are really good.”

For Stuecken, the idea of going up against experienced male players was intimidating. Prior to the winter season, she had not played soccer since her senior season in high school and was hesitant to join IM.

Ultimately, she decided to step out of her comfort zone on the condition that she would have one of her friends playing by her side. Stuecken found that as the season progressed, she got more comfortable in the playing environment.

Looking to the future, many players believe that there are ways to make the IM program more encouraging for female

league or stronger rules against slide tackling could make the environment more welcoming.

Stuecken notes that having more female referees would contribute to a more positive environment. In fact, she does not recall having a single female referee throughout the season.

Some of these approaches have been tested in the past. Coleman has worked as the IM director since 2001, and has attempted to create women’s leagues across various sports several times. According to him, not enough people sign up.

Coleman says since more female players show up to the COREC league, that’s what the program pursues.

“I do my best, because we don’t have women’s leagues, to create a more positive environment for women in those leagues,” Coleman says. “Like for basketball, it’s three women on the court. Most schools around the country, it’s two. And I thought, ‘now we don’t run a women’s league, so I want there to be more women on the court.’”

Coleman is constantly checking in with his staff of student officials and supervisors to make improvements to the program. This means the gender

COURTESY OF TILLIE FREED

“You would have thought

Rosa Saavedra Weinberg first-year we won the World Cup.”

Coleman also points out Northwestern’s IM program is twice the size of some state school programs in the Midwest. According to Coleman, having solely COREC leagues in the winter instead of “open leagues,” or ones where there is no gender requirement, somewhat mitigates this problem. If there were only open leagues, he predicts he would receive up to 150 teams attempting to register, composed of mostly males.

Saavedra reflects on the moment when her team — the “Ball Busters” — finally secured their first win from the last game of the season.

“You would have thought we won the World Cup,” she says. “Moments like that remind me of when I played club soccer competitively and how much I miss it.”

in a positive direction. Williams notes there has already been a large increase in the number of women since she started playing three years ago. That said, there is always room for improvement.

“Being part of a team is such a valuable experience,” Freed says. “I would like more girls to be able to

Washington to Wildcat

Professor Kirabo Jackson talks economic policy and undergraduate advice.

WRITTEN BY JAMIE NEIBERG // DESIGNED BY ADELLE RUBINCHIK

In 2023, Kirabo Jackson left the hallowed halls of Northwestern’s School of Education and Social Policy for somewhere a little more high-profile: the White House. During his time as a member of the Biden Administration’s Council of Economic Advisers, Jackson gained new perspectives on policymaking and navigating economic uncertainty. This spring, North by Northwestern sat down with the professor to learn more about his experiences. Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

NBN: What was the transition like from academia to policymaking?

Jackson: The administration brought me in largely because I had expertise in the areas of labor economics and education policy. After the pandemic, the administration was thinking about the decline in test scores and deterioration in mental health among students.

I had the expertise and was happy to work and help them achieve their policy goals in the most economically sound way. I had to change my orientation a little on certain topics as I wouldn’t say that I agreed with everything the administration was doing.

NBN: Why do you think there was a disconnect between economic indicators and public sentiment under the Biden administration?

That’s an interesting question I’ve been asked many times. I can answer it more honestly now because I’m no longer representing the White House.

The Biden administration struggled to effectively communicate economic wins because the benefits were often gradual while the pain points, like inflation, were immediate and tangible. It’s a reminder that economic policy success isn’t just about the numbers but about how people experience their day-to-day financial lives.

COVID was a disruptive time. It exposed many Americans and many people across the world to the fact that things are not always as stable as they seem. We were going about our lives just regularly and, suddenly, something drastically changed. Having said that, the economy under Biden was growing strong. We had a GDP growth of, like, 3.4% in 2024.

Despite statistical improvements in wage growth, especially for lowerincome workers, people’s lived experiences often differed from what the data suggested. Several factors contributed to this disconnect.

First, inflation hit hard during the post-pandemic recovery. Even with wage growth, many families saw their grocery and housing costs rise significantly, which eroded purchasing power and created financial stress despite nominal income gains.

Second, these economic improvements were happening against a backdrop of pandemic trauma and political polarization. When people are anxious or divided, positive economic news often doesn’t resonate the same way.

Third, economic indicators are averages that can mask individual experiences. A family facing a medical emergency or housing crisis might not feel the benefits of broader wage growth when facing immediate financial pressures.

NBN: You have been an expert witness in cases determining whether school funding is constitutional. How do you make sense of current changes regarding federal funding for education?

I’ve been thinking a lot about the implications from multiple angles. When these things happen, the first reaction is, “This sounds very drastic. What does it mean?”

One of the first things I try to do is think, “What does the federal government do? How much money does the federal government control? What is the role of the federal government in the K-12 system and in higher education as well?” That helps ground yourself to get a sense of possible scenarios.

Title I, which provides federal money for lower-income kids, came into existence under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. That predates the establishment of the Department of Education. We must provide money for students with disabilities. That also is by statute, not something the president can just decide to not fund.

If that money were to disappear, lowincome kids and students with disabilities would be

disproportionately affected. Affluent neighborhoods wouldn’t feel it as much because they don’t receive as much federal funding.

To put this in perspective: if all federal education dollars were eliminated, research estimates suggest the overall high school graduation rate could fall by 3 or 4 percentage points. The collegegoing rate would likely fall by about 5 percentage points. That’s a significant impact on our future workforce and productivity decades down the line.

The silver lining is that because most education happens at the state or local level, we can lean on state legislators, policymakers and local community leaders to step up. It will be painful for some communities, but if we focus locally, we can weather the storm.

NBN: With Northwestern’s hefty price tag, is a Northwestern degree still a sound investment?

The good news is that the Northwestern brand is strong, and your education will be valuable.

There’s been debate in popular media suggesting education’s value isn’t what it used to be. That’s simply not true. People are less likely to pursue two-year degrees at community colleges, but enrollment in four-year institutions remains strong.

Looking at returns on education: college graduates earn 40-50% more than those with just high school diplomas. Those returns remain substantial, and I don’t see that changing anytime soon.

Regarding the future, I don’t think it’s feasible for us to move back to an economy where the middle class is sustained by doing things with our hands. That’s not how we make things anymore. Instead, we’re an economy where we use technology to a great extent.

NBN: As we enter this new economic terrain, what survival skills should young people be developing?

One of the benefits of having a Northwestern degree, or any sort of fouryear degree, particularly one from a T10 institution, is it provides a broad set of skills. Not just in terms of knowing a particular topic area, but it teaches you not just what to know, but also how to think about things, how to reason. It’s those problem-solving skills, those reasoning skills that allow workers to be more nimble.

Number two: make yourself indispensable. Make sure that you’re at a position where if they tried to get rid of you, they would have to jump through many hoops.

Number three: keep up with the times. Get up to speed on how people are using AI. I think that’s going to be really helpful. For young people, I think that’s going to be second nature, but for dinosaurs like me, we have to sort of pick it up and learn it.

The best way to navigate economic uncertainty is always to develop adaptable skills. Northwestern graduates will be well-positioned to weather these changes better than most.

Upon entering the AMC Evanston 12, students are greeted by the bright neon sign, movie posters and the smell of buttered popcorn and Icees. But this June, they won’t be coming to the theater for a star-studded Hollywood production. Instead, Hello, Goodbye will be on screen, a full-length feature film created entirely by students in Northwestern’s Applause for a Cause.

Founded in 2010, Applause for a Cause is a student-run club that creates an 80 to 180-minute film every year to support charity.

The project is funded by the Associated Student Government (ASG) and a fundraising campaign through a platform called Catalyzer. Students encourage friends and family to donate and sometimes host fundraisers to raise money for the film and items needed to create it.

The film’s proceeds go to a Chicago charity of the group’s choosing, with this year’s being GirlForward: a nonprofit geared toward providing a safe space and resources for refugee and immigrant girls by pairing them with women mentors in the community.

“This year, we wanted something that is in Chicago, so it’s local, and something that relates to the themes of the movie … a community coming together to support someone when they’re going through a tough time,” Communication secondyear and co-director Brody Bundis says.

Getting the show on the road

COURTESY OF HANNAH OTNESS

Behind the scenes

From conceptualizing the story to getting the cast and crew on set, hours upon hours of work have been poured into this film. Students of all grades, majors and experience levels have contributed to make it a success.

Bundis and his co-director, Communication second-year Levi Gillis, hold many responsibilities including pre-production preparation, workshopping the script, finding actors, the day-to-day tasks of heading production and creative direction on set. They are also in charge of hiring some of the team behind the film, including makeup artists, sound technicians and editors.

Bundis emphasizes that his job as one of the directors is intertwined with the rest of the team. Weinberg secondyear and co-producer Yuka Sumi says her responsibilities revolved around organizing behind the scenes, such as booking locations and making sure there was food on set.

“Sleepless nights, planning, trying to execute, failing and overcoming ... it’s a lot of work.”

Levi Gillis Communication second-year

“It’s a really great thing that we have such a big team and we all share our responsibilities and work together to do this,” Sumi says.

Underclassmen also play a big part in the Applause for a Cause team. Communication first-year Maille Hickey petitioned for and got the role of Assistant Director (AD). Despite being new to the school, Hickey found her voice making sure that everyone was organized and production stayed true to the schedule.

“[Bundis] and [Gillis] were really helpful,” Hickey says. “It was my first set ever. They taught me what to do, and I learned by the end of the quarter what being an AD meant and what my style of being an AD is.”

The show goes on

Time spent on set wasn’t always perfect, Bundis recalls. One of the crew’s locations backed out after they had begun to film there, meaning the team had to find a new place at the last minute and reshoot many scenes.

In another instance, only one makeup artist was available, causing the set to run an hour behind. It was up to the student leaders to find solutions on the fly and keep their movie running smoothly.

“We all want this project to succeed. We all have poured our blood, sweat and tears into this thing, and we don’t want to see it falter,” Gillis says.

Even with late nights and occasional mishaps, Applause for a Cause members remain devoted to the project.

The culmination of the cast and crew’s hard work over the past year will be on display for students and community members on the big screen. A premiere will take place in June to celebrate the accomplishments of the students involved.

“Every weekend last quarter was spent on this film,” Gillis says. “Sleepless nights, planning, trying to execute, failing and overcoming, and it’s a lot of work. But I mean, once I see the final product, I have a feeling that it’s all worth it in the end.”

Passport to progress

Students intern abroad with the Global Engagement Studies Institute.

WRITTEN BY CAROLINE KILLILEA // DESIGNED BY MARLEY SMITH

On one of Katie Cummins’s last days in Argentina, she went to a barbecue hosted by her boss’s neighbor. The Communication fourthyear stayed until 2 a.m. talking, laughing and enjoying traditional Argentinian food and beverages with her newfound community.

Cummins studied abroad through Northwestern’s Global Engagement Studies Institute (GESI), a summer experience that places students at full-time internships with local development organizations in a variety of countries ranging from Bolivia to Vietnam. Cummins worked for a nonprofit that provides environmental consulting for sustainable urban development projects in Salta, Argentina.

Cummins says the late-night barbecue memory encapsulated what it meant to participate in an immersive study abroad experience.

“Wow, this is so magical,” she says. “Just being able to integrate into a community like this and being able to pass an evening in such a lovely way.”

GESI aims to connect undergraduates with the resources needed to learn about and confront global issues. All grades and majors are eligible to participate in the various programs. Students are assigned to internships based on their interests and preferred location, as well as their language ability, if they opt to live in a Spanish-speaking country.

Prior to Cummins’s summer abroad, Argentina had elected President Javier Milei, a conservative leader who slashed federal spending. The nonprofit’s funding had been cut, so Cummins worked alongside a fellow Northwestern student to help build its website and create a strategy for finding alternative funding.

After Cummins returned from Argentina, she became a Global Learning Office (GLO) Fellow, and now runs the GLO ambassadors program that promotes studying abroad.

“I’ve loved getting to know the GLO staff more, and being a mentor for other students and a campus leader in that regard,” Cummins says.

Weinberg third-year Annika Macy also sought a study abroad experience beyond a typical quarter in Madrid. She found what she was looking for with GESI, in the form of a homestay with a Costa Rican family. For Macy, it was an opportunity to speak the local language and become a part of the community.

Macy lived just outside Costa Rica’s capital city of San Jose. She worked at a nonprofit that provides students from impoverished neighborhoods with meals, academic support and a place to stay before and after school. Macy says because of her summer with GESI, she learned to connect with others despite a language barrier.

“Especially with kids, being able to just play games with them and talk about what their interests are and things like that — at a very low level, you can still build connections,” Macy says. “It definitely reinforced my decision to do a Spanish minor because I really find it important to be able to connect with people who I otherwise wouldn’t be able to speak to.”

Macy says her time spent in Costa Rica opened her eyes to the importance of education. She wants to continue the nonprofit’s work by making education more accessible for students across the globe.

Be mindful of the gutter! If you want your photo/illustration to span the spread, just make sure nothing important is in the gutter.

“Education became a more important part of what I want to pursue in the future,” Macy says. “Any study abroad program, especially this one, can really push your comfort zone because you’re not just taking classes. You’re really diving deep into living in a community. I think you can learn a lot about yourself and about other cultures.”

COURTESY OF KATIE CUMMINS

This summer, students will be going to Argentina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Thailand, Uganda and Vietnam through GESI. SESP second-year Adelle Johnson will be going to Costa Rica. She says the program has been on her radar since before even applying to Northwestern.

Starting this year, SESP students can use GESI to fulfill their practicum and experiential learning requirement.

GESI encourages students to immerse themselves in the language so they are able to communicate more easily with locals. Johnson said she will learn more about education in other countries through conversing with real students.

“Getting conversation with native speakers can be difficult, especially outside of an academic setting,” Johnson says. “I feel like the language use is so different, so I’m really excited to stay in a homestay and be able to use the language all the time and get more practice with that. It’s really a unique experience.”

Weinberg fourth-year Caitlin Jimmar, who studied abroad in Bolivia with GESI in 2023, interned with a nonprofit organization that provides care and advocacy for people with disabilities.

Jimmar, whose mother is a speech therapist, helped start a speech therapy program for the nonprofit. She says GESI taught her about the importance of local advocacy work.

“With the program, there’s also a class component in international development, and I think that class is really important because it gives you the theoretical background to come into that nonprofit space, especially taking into account your positionality as an American college student coming into an organization,” Jimmar says.

Jimmar says her homestay experience was her favorite aspect of GESI. She says living with a large family resembled a summer at home with her own.

“Living at college, we’re away from our families,” Jimmar says. “So it was really nice to spend a summer living with a family again, helping my host niece with her homework at night, watching TV together on the weekends. One of my host sisters was about my age, so we hung out a lot. We still talk today.”

“At a very low level, you can still build connections.”

Annika Macy Weinberg third-year

COURTESY OF KATIE CUMMINS

Drawing back

The dynamics of student theater.

WRITTEN BY DESIREE LUO // DESIGNED BY LENA ROCK

the curtain

* Name has been changed to protect source’s identity.

In black box theaters across Northwestern’s campus, students craft productions that blur educational exercises with professional showcases. The theatre community, which alumni have collectively dubbed the “purple mafia,” creates a unique environment where personal relationships and career aspirations intertwine.

“After you’ve been here for a little while, it kind of is like every single audition you do is for somebody that you know,” says Communication secondyear Casey Bond. “Everybody kind of knows everybody.”

Each freshman class caps at 100 theatre majors, according to the School of Communication Office of Undergraduate Programs and Advising.

Many freshmen join the Student Theatre Coalition (StuCo), a collective of nine student-run theater boards and two dance groups that produces about 30 shows yearly. Each group maintains its own executive board and performance series while sharing organizational

support through StuCo practices like general auditions, space allocation and equipment management. The co-directors of each board, along with two StuCo cochairs, form the coalition’s leadership.

Each board follows a specific theme and produces up to three shows annually. For example, Vertigo Productions focuses on students’ newly written work while Purple Crayon Players showcases children’s plays.

“It’s unserious and it’s also the most serious thing you’ve ever done,” says Communication second-year and Vertigo president Lux Vargas.

Some student actors, stage managers and music directors also work with the Virginia Wadsworth Wirtz Center for the Performing Arts (Wirtz), a production company staging about 40 shows yearly. Communication secondyear Mia El-Yafi performed in three StuCo productions as a freshman. This year, she acted in three Wirtz shows — Antigone , Lobster and Mancub — led by Masters in Fine Arts (MFA) students and professional local directors.

“The Wirtz shows feel very professional and by the book, whereas the StuCo shows feel much more like a family and a community,” she says. “Maybe you’ll spend a little more time doing a check-in, and it’s just kind of less strict.”