by Will Nicholls

Ablog written back in 2015 lists eight key issues for Indigenous Peoples in Canada. I would argue that there are many more. To begin: Indigenous children and youth have higher death rates, live in inadequate housing, have higher rates of suicide, poorer health, lower levels of education, higher rates of incarceration, higher rates of unemployment and lower income levels.

Written by Bob Joseph, a member of Gwawaenuk First Nation in BC, the article says this is due to a combination of the Indian Act and colonialism. For example, he wrote, the World Health Organization recognizes colonialism as a “common and fundamental underlying determinant of Indigenous health.” Poorer health is linked to lower income, social factors and more.

I would add that the systemic racism prevalent in Canada’s health systems is another factor. It led to Jordan’s Principle (to ensure Indigenous children receive the same health benefits as other Canadian children) and Joyce’s Principle (who died in a Joliette hospital as medical staff ignored her and made racist remarks).

When I went to the emergency room at a Montreal hospital, I had to inform them that I was First Nations so staff could speak English with me, which is a small improvement. Others have faced larger problems.

In Quebec, colonialism is stronger than ever in the education system. The CAQ government’s imposition of sharply higher tuition rates for out-of-province students in English post-secondary education institutions is one example. The requirement to prove French proficiency to graduate is not only designed to discourage enrolment in Quebe’s English-

language schools but will also be one more barrier for many First Nations students from other provinces.

Inadequate and crowded housing conditions is an issue that has existed since settlers mandated places where Indigenous people could live. The problem harms physical and mental health, often leads to domestic violence and helps produce food insecurity. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the RCMP came into many communities and killed all the dogs. The reason for this was to reduce mobility and keep First Nations people on reserves.

Indigenous people have lower incomes as there are no real local economic engines in most communities. People had to move away to find jobs, and many lost Indian status as a result.

Higher levels of incarceration are something that all First Nations know. Look at the jails – it’s mostly just us. In

federal prisons, 50% of female inmates are Indigenous while the total Indigenous population (male and female) is only 5% of Canada’s population.

Early deaths and injuries of children as well as higher rates of suicide are well known. Children who suffer injuries in remote communities rarely receive any form of physical therapy or rehabilitation or access to other resources they may need. While Jordan’s Principle was helping, the federal government hasn’t renewed funding in this year’s budget. Suicide rates have always been high, ranging from nine times the national rate for the Inuit and three times that for First Nations.

One key issue that Joseph left out is sex trafficking. About 50% of women, girls and children who are sex trafficked in Canada are Indigenous. The Nation is published every two weeks by Beesum Communications EDITORIAL BOARD L. Stewart, W. Nicholls, M. Siberok, Mr. N. Diamond, E. Webb EDITOR IN CHIEF Will Nicholls DIRECTOR OF FINANCES Linda Ludwick EDITORS Lyle Stewart, Martin Siberok PRODUCTION COORDINATOR AND MANAGING EDITOR Patrick Quinn, Randy Mayer CONTRIBUTING WRITERS X. Kataquapit, S. Orr, P. Quinn, J. Janke, M. Boivin-Neashit DESIGN Matthew Dessner SALES AND ADVERTISING Danielle Valade, Donna Malthouse THANKS TO: Air Creebec CONTACT US: The Nation News, 918-4200 St. Laurent, Montreal, QC., H2W 2R2 EDITORIAL & ADS: Tel.: 514-272-3077, Fax: 514-278-9914 HEAD OFFICE: P.O. Box 151, Chisasibi, QC. J0M 1E0 www.nationnews.ca EDITORIAL: will@nationnews.ca news@nationnews.ca ADS: Danielle Valade: ads@nationnews.ca; Donna Malthouse: donna@beesum.com

50% of female inmates are Indigenous while the total Indigenous population (male and female) is only 5% of Canada’s population

SUBSCRIPTIONS: $60 plus taxes, US: $90, Abroad: $110, Payable to beesum communications, all rights reserved, publication mail #40015005, issn #1206-2642 The Nation is a member of: The James Bay Cree Communications Society, Circle Of Aboriginal Controlled Publishers, Magazines Canada Quebec Community Newspa per Assn. Canadian Newspapers Assn. Les Hebdos Sélect Du Québec. Funded [in part] by the Government of Canada. | www.nationnews.ca | facebook.com/NATIONnewsmagazine | Twitter: @creenation_news

by Myriam Boivin-Neashit

Community gardens and greenhouse projects are taking root in Eeyou Istchee, fortifying local food security and revitalizing traditional harvesting practices despite the challenges posed by climate change. The boreal climate profoundly shapes daily life and traditional activities, presenting significant challenges for agriculture and garden sustainability.

These initiatives provide fresh produce and cultural connections in Eeyou Istchee. Greenhouses in Chisasibi, Wemindji and Whapmagoostui are extending the growing season, yielding vegetables that include zucchini, potatoes, tomatoes, cucumbers and broccoli.

“During challenging times, such as when grocery prices soar, these activities are invaluable,” emphasized one community member on Facebook.

There are workshops and other initiatives like gardening with students, which educate and engage community members of all ages in sustainable gardening practices. People are sharing photos of

their gardens and tips on social media, spreading awareness and inspiring others to participate in these practices.

A community member excitedly posted during the grand opening of the Wemindji greenhouse last October: “Look how full of life it is! They are growing zucchini, potatoes, tomatoes, cucumbers, broccoli, pumpkin, snow peas, jalapeños, lettuce, peppers, flowers… and more!”

Traditional harvesting practices like berry picking and mushroom foraging also play a role. These activities not only supplement diets but strengthen the bond between people and nature. The rich biodiversity of Eeyou Istchee, including boreal forests and wetlands, supports these practices.

However, the boreal climate faces numerous challenges. Increasing temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and ecological disruptions such as wildfires threaten local food systems and has had severe consequences for wildlife in the region.

Furthermore, the warming climate is altering the distribution of various animal and plant species. For example, eelgrass, crucial for migrating geese, has been declining along the coast, impacting hunting opportunities. This decline has also led to seals venturing ashore less frequently.

Many community members have highlighted that unpredictable weather is already disturbing hunting activities. These shifts disrupt ecosystems and pose significant challenges for wildlife conservation efforts.

In response, adaptation strategies are being developed to safeguard local food security. These include identifying climate change impacts on key food species, enhancing resilience through diverse agricultural practices, and integrating traditional ecological knowledge into modern adaptation strategies. Researchers point out that understanding these impacts and developing informed predictions are critical to the sustainability of northern communities.

Cree graduates of the first full-time in-community teaching program in Eeyou Istchee recently celebrated their convocation at Montreal’s Bell Centre, the result of a fruitful collaboration between the Cree School Board (CSB) and McGill University.

While this partnership with McGill’s Office of First Nations and Inuit Education (OFNIE) goes back over 40 years, the first full-time Bachelor of Education program for Kindergarten and Elementary Education was launched in 2020. It’s the same four-year program that is offered on campus except it is entirely community-based, primarily in Chisasibi, Waskaganish and Mistissini.

Without having to uproot their families to adapt to the significant challenges of studying in the city, students benefit from staying connected to their culture and local support networks. Several students questioned whether they would have completed the program without the encouragement of their family and friends.

“We got through this by encouraging each other,” said Constance Esau. “If someone said I want to quit, we’d say keep going, we’re almost done. Our family and friends played a huge role in this. I’m 36 and I just want to say it’s never too late to go back to school.”

Studying full-time in the Bachelor of Education program, Esau said it was challenging to manage the workload and budget expenses with the modest CSB allowance. Having newborns added an extra complication.

“I decided to get pregnant at a wild time, the first year the program started,” said Esau with a laugh. “It was challenging travelling, especially when I had to leave my kids. The first time I left my son, I cried many hours. Then the first time I left my daughter I cried too because that’s when her breastfeeding journey ended.”

While classes were held in Esau’s community of Waskaganish, instructor availability resulted in frequent trips to the larger group in Chisasibi and sometimes to Val-d’Or. Although courses generally alternated between

weeks in-person and online, the Covid pandemic forced the first half of the program to be exclusively online.

Working years as a waitress, Esau never dreamed of becoming a teacher until seeing a job posting at the Lodge. After starting in the school’s daycare program, she got a taste for teaching when asked to fill in as a substitute.

“I realized I like working with children,” said Esau. “It was intense at times, but the teachers were very understanding and helpful. I’m going to be teaching Grade 2 in the fall. The ones I graduated with from Waskaganish, we’ve all been hired.”

Eastmain graduate Alice Gilpin earned her certificate in education in the culture and language program and now plans to continue with the bachelor’s program. While she had previously worked in Cree language development, Gilpin finished high school as an adult and never went to college.

Overcoming big doubts to enrol with a 4-year-old daughter, part-time online and in-community courses enabled her to complete her studies even as she gave birth to two more daughters. However, there were times she questioned whether she wanted to be taking care of children both at home and at work.

“I said I’m just going to keep going and see how this ends,” Gilpin recalled. “When I walked across the stage in Montreal for our graduation, I felt ‘Yeah, I’m ready to become a teacher.’ My children were my

by Patrick Quinn, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

motivation because I’m also a role model. My girls are excited to start school to see me as a teacher.”

Gilpin fondly remembered her late grandmother Minnie Weetaltuk Gilpin, an Inuk woman who taught Cree literacy and created materials for the CSB. She’s grateful for the generations of trailblazers whose hard work developed the impressive Cree education system.

With many winter journeys, canoe brigades and hunting expeditions under her belt, the land-based courses were Gilpin’s favourites. Cree instructors were proud to see more Crees take this journey to educate their own people.

“It connected us when we were out on the land because if one person didn’t know what to do, another person always said I can show you how,” explained Gilpin. “When we’re teaching at the school, we always encourage our students to work together, trust each other and treat each other with respect.”

The CSB’s unique partnership with McGill;s OFNIE has evolved over the decades from part-time courses offered outside of teacher working hours to increasingly comprehensive and tailored programs. Working together to develop course outlines, the university welcomes culturally relevant topics while ensuring provincial education requirements are met.

Among the 28 students in the fulltime program, 23 recently graduated while others who may have taken medical or

maternity leave will likely graduate this autumn. To support students with passing the English exit exam necessary for the degree, the CSB offered online tutoring services and an in-person session of boot camp with intense grammar and writing.

“Of course, it was our first cohort so there were some shortcomings,” said Charlene Erless, the CSB’s coordinator of professional development. “We listened and are making improvements as we go. Since Covid, Air Creebec doesn’t fly directly from Chibougamau to Chisasibi anymore and the younger generation doesn’t have vehicles yet.”

There are currently 154 Cree students enrolled in six CSB teaching programs, including a certificate in inclusive education for teaching children with special needs. Erless revealed there are discussions about soon offering an in-community master’s degree program for Cree teachers.

The CSB launched its second fulltime cohort in 2023. Erless would like to see more applicants from the smaller communities, noting the clear benefits of having more Cree teachers in schools for employee retention and improving the student experience.

“They get to stay in their hometown and work with their people,” explained Erless. “You know these students very well. You see them when you go to the community store or arena. The students are more respectful, or they feel that sense of belonging in the school.”

Department of Commerce and Industry

Mobile clinic

Mikinakw launches

The Centre d’amitié autochtone de Lanaudière (CAAL) has launched Mikinakw, Quebec’s first mobile clinic created by and for Indigenous people. This innovative clinic aims to address holistic health, intervention and education needs directly within the Indigenous communities of Lanaudière.

Mikinakw will offer a range of services from SaintMichel-des-Saints to southern Lanaudière, focusing on areas with high Indigenous populations. The clinic provides medical care for isolated individuals and psychosocial support, as well as educational services and parental support. Hours and locations will vary seasonally and can be found on CAAL’s website.

“This project represents significant progress in public health,” said Joliette Mayor Pierre-Luc Bellerose. “I am convinced this initiative will have a positive and meaningful impact on the well-being of Lanaudière’s Indigenous population.”

Supported by an initial investment of $300,000 and annual operating costs of $40,000, Mikinakw is made possible through partnerships with the Regroupement des centres d’amitié autochtone du Québec (RCAAQ) and the National Association of Friendship Centres (ANCAA). The clinic’s exterior, a mobile art piece by artist Eruoma Awashish, involved eight young CAAL participants, expressing their cultural pride through art.

“Mikinakw is not just a holistic health clinic,” said CAAL Executive Director Jennifer Brazeau. “It’s a clinic of intervention and education

that will meet the community near their homes.”

Wearing a keffiyeh, a traditional scarf that symbolizes the Palestinian struggle, Katsi’tsakwas –better known as the Mohawk activist Ellen Gabriel – emphasized the struggle for Palestinian liberation during her acceptance of an honorary doctorate from the Université du Québec à Montréal June 8.

She noted that there are few universities in Gaza – and that there will be not a single graduate in 2024.

“It would have been irresponsible of me not to mention it, and not to stand in solidarity with Palestinians and other oppressed people,” Gabriel stated. “What we see today is a movement where oppressed people are coming together.”

Gabriel highlighted the parallel with how education has oppressed Indigenous people in Canada. “The history of Western education and the Indigenous people of Turtle Island is a difficult one,” she said in French. “Education was a tool to destroy our languages, our cultures, and alienate us from our Native lands, attacking our families and our identities.”

Rachelle Chagnon, UQAM’s dean of political sci-

ence and law, noted that the university’s history of activism mirrors Gabriel’s advocacy. “We have students who will always be very strong in their opinion, and they’re vocal about it. We’re renowned for that, and Ellen fits in with the way we are,” said Chagnon.

Gabriel’s speech received a standing ovation from the UQAM audience. “It’s even more precious to have this honour from a university that has a reputation for social justice and human rights,” she concluded. “To be able to speak freely without censorship is a tribute to their openness and leadership. Not every university will do that. I’m really honoured.”

by Patrick Quinn, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Red Fever , the newest documentary from Cree filmmaker Neil Diamond and co-director Catherine Bainbridge, explores the roots of cultural appropriation to reveal the profound influence of Indigenous cultures on the world’s fashion, sports, arts and even politics.

Following the award-winning Reel Injun’s analysis of Hollywood stereotypes and Rumble’s look at Indigenous voices in music, this final act of the trilogy opened in theatres June 14 after a triumphant premiere at Toronto’s Hot Docs festival in May.

“The film evolved over a long time,” Diamond told the Nation. “It was going to be about cultural appropriation, then the Covid pandemic hit, and it evolved into the influence of Native Americans on world culture. People have a very distorted view of Native people.”

With the Black Lives Matter movement shifting perceptions about culture and privilege, the filmmakers felt that people now knew they shouldn’t appropriate but didn’t really understand why. Examining

the imagery underlying much of Western culture, Red Fever asks why people are so attached to enduring fantasies of “fierce warriors” or “magical peoples.”

Exploring Indigenous influence on fashion, sports, politics and the planet, Diamond serves as the film’s guide on both sides of the camera. Bookended by beautiful portrayals of Eeyou Istchee, Diamond’s travels around the world exude warmth and curiosity.

“Neil brings a very Cree humour and point of view to the documentary,” said Bainbridge. “He comes at it never wanting to shame people, just teasing and really open. That’s what makes it a place where people can come into the room and be part of the discussion.”

While illustrating high fashion’s longstanding scavenging of Indigenous designs, Red Fever highlights emerging Indigenous talents and bridges wider trends with personal reflections. Finding a hat made from beaver in New York City leads Diamond to discuss his hometown of

Waskaganish, the site of the Hudson Bay trading post that launched the international fur trade.

The infamous appropriation of an Inuit shaman’s parka inspires Diamond to visit his friend, filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk, in Igloolik to learn about the significance of these traditional garments. A rousing glimpse of seal hunting is followed by a moving ode to the end of shamanism in Inuit culture.

With thousands of sports teams based on offensive caricatures, Diamond wanders through a crowded bar where Kansas City Chiefs fans crudely imitate a tomahawk chop. However, rather than dwell on stereotypes, the film prefers to emphasize positive stories such as the sacred practice of running in Navajo culture.

A digression on the extraordinary career of Jim Thorpe, one of the most celebrated athletes of the 20th century, reveals the Indigenous boarding school he attended introduced key strategic elements that made American football the game it is today.

Some of the doc’s most provocative points come when Diamond argues that the ideals of freedom and democracy so fundamental to the American Dream were inspired by interactions with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Their Great Law of Peace that united warring groups influenced European colonizers, as did inherently Indigenous values of respect, individualism and female empowerment.

“It’s a hidden part of North American history,” asserted Diamond. “Imagine the very first settlers had been living under kings and queens for generations and generations, and they meet people who don’t bow down to anybody.”

Bainbridge suggested that era’s violence overshadows the much more routine communication and trade. With proximity between settler and Indigenous communities, she said that more than half of trade at the time was cross-cultural, which inevitably influenced both sides.

The film conveys how Indigenous contributions are woven through modern society, charting Indigenous peoples’ growing power and cultural revitalization. The breezy presentation and striking visuals make it an easy watch as the editing team led by Rebecca Lessard layers the nar-

rative with an impressive depth of visual archives.

“The imagery Neil is able to capture behind the camera is so evocative,” said Bainbridge. “The canyons and young runners in the Navajo territory are so beautiful, and in the North with Zacharias Kunuk. It so lifts the hearts of people who watch the film in theatres to see Neil’s magnificence in the dark room.”

Diamond and Bainbridge have worked together since being young journalists in the 1990s, along with Chisasibi’s Ernest Webb, who is Bainbridge’s husband and one of Red Fever’s executive producers. After co-founding the Nation magazine with Will Nicholls, Bainbridge and Webb created Rezolution Pictures in 2000.

As executive producer, Webb said he helped shape the film’s tone while supporting the directors’ vision. With Rezolution’s TV series Little Bird racking up numerous awards, he’s noticed broadcasters and mainstream audiences are becoming more open to Indigenous stories.

“Sometimes when you’re filming, you’ll know when you’ve got something special going,” Webb said about Little Bird. “Everybody put their heart and soul into it, and it reflects what you see on screen. Our future as a production company is looking bright.”

An enthusiastic screening to 600 high school students and their teachers has already demonstrated Red Fever’s potential as a learning tool. Future broadcasts on German and French television will show its European version with exclusive content about a German subculture that imitates Indigenous culture from centuries ago.

Red Fever closes on an optimistic note, showing the successful return of salmon to British Columbian waters guided by Indigenous environmental stewardship. Along with the closing image of Cree fiddlers, inspired by contact with early Scottish settlers, the message conveyed is that being influenced by other cultures isn’t necessarily negative – indeed, the world clearly has much still to learn from Indigenous peoples.

Project to protect and manage coastal regions nears fruition

by Patrick Quinn, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

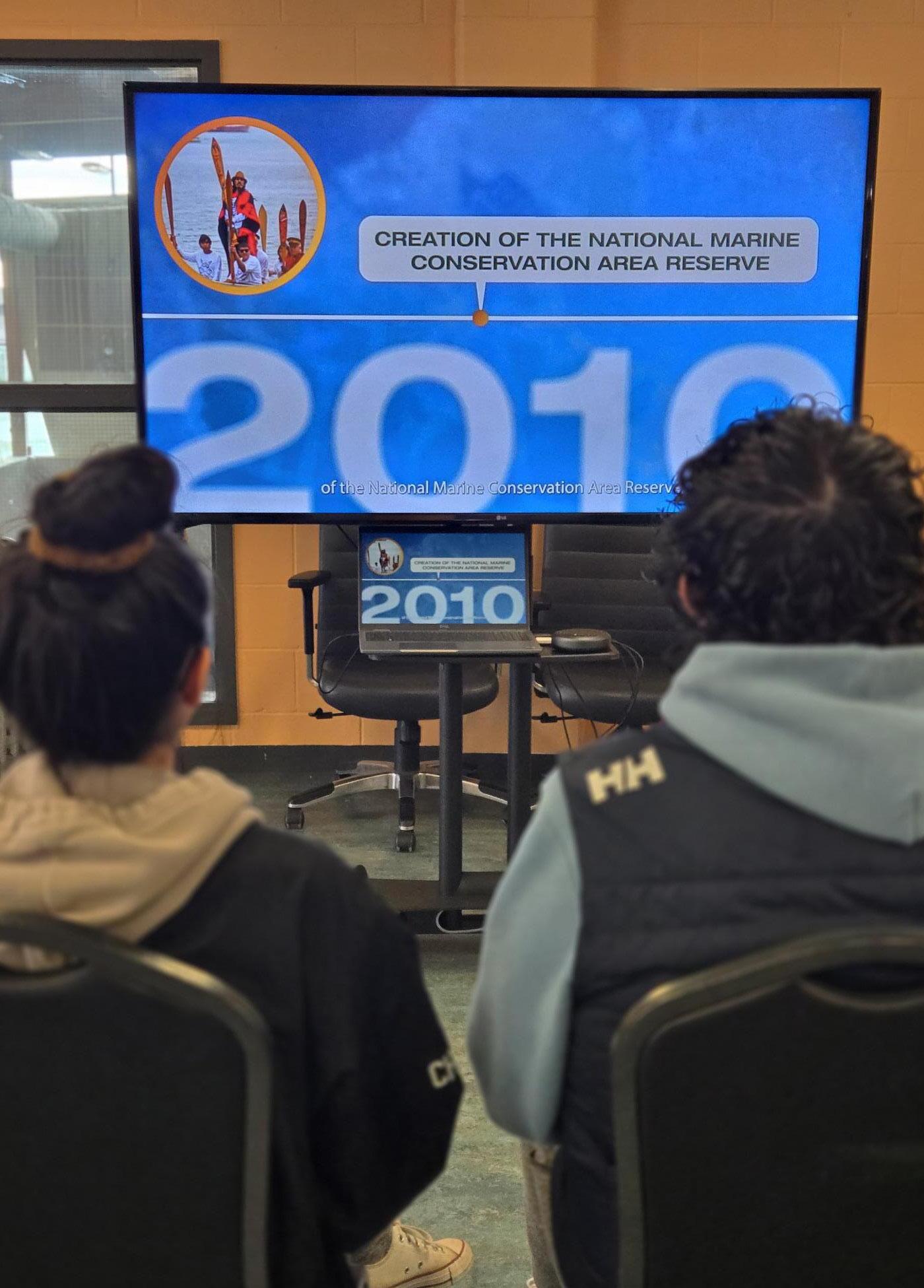

Consultations for the National Marine Conservation Area (NMCA) feasibility study recently wrapped up in Cree coastal communities. Two-day focus groups were held in Waskaganish, Eastmain, Wemindji and Chisasibi after Goose Break, concluding with an information session in Whapmagoostui.

Deputy Grand Chief Norman A. Wapachee leads a steering committee to guide the assessment process alongside protected areas manager Chantal Otter-Tétreault and members of Parks Canada. The feasibility report will be submitted to the Grand Chief and environment minister ahead of an expected announcement at the Annual General Assembly in Wemindji in August.

“Wenipaahk [James Bay] was always part of Eeyou Istchee,” asserted Wapachee. “It was a sacred gift from our ancestors, and we need to find ways to protect it. The NMCA team talked about the importance of culture, preserving the ecosystem, the traditional way of life.”

The initiative stems from Wemindji’s Tawich (marine) project starting in 2007, which sparked protection discussions with the federal government. In 2012, the Eeyou Marine Region (EMR) land claims agreement recognized Cree jurisdiction over coastal waters and 80% of the islands in James Bay.

A 2019 agreement began identifying offshore priorities for conservation as part of a federal plan to double protected areas on both land and water. While the proposed NMCA only covers the “Cree Zone” of the EMR, hopes are that discussions with the Nunavik Inuit will expand this coverage to overlapping areas north of Chisasibi.

“For the Cree, it’s about expanding governance out in the bay,” Wapachee told the Nation. “The NMCA only touches waters. It would be up to the Cree if they want to build traditional camps on the islands – the youth were talking about maintaining cultural villages in the bay.”

While the NMCA wouldn’t replace existing EMR boards, it would provide additional funding for environmental monitoring and tourism infrastructure

with flexible zoning to limit access to specified areas. Defining roles and responsibilities with Parks Canada will ensure Cree traditional practices are maintained.

NMCAs intend to balance safeguarding ecosystems with supporting sustainable use, inviting visitors to learn about preserving vulnerable regions. Parks Canada is currently leading the creation of 10 new NMCAs, contributing to Canada’s international commitment to protect 30% of marine and coastal areas by 2030.

With many rivers bringing freshwater into the bay, Eeyou Istchee’s waters have a low concentration of salt and rich biodiversity. Freshwater fish mingle with marine fish, migrating birds are plentiful and beluga whales winter in its relative shelter.

Recent community engagement sessions took a storytelling approach, with potential benefits explained through a conversation between “Kaya and Noomshoom” before splitting into focus groups and one-on-one discussions.

“One of the benefits is ecological restoration or recovery of species,” explained Wapachee. “Mining came up in almost all communities. I think the Cree will have to tighten up environmental regulations upstream wherever there are mining activities – we know this has intensified up north.”

People were reassured that their hunting and fishing rights remain constitutionally protected even in national parks. Whapmagoostui was eager to expedite the process to include their offshore islands, which Wapachee said hold intriguing legends.

Communities anticipate an increase in tourism with associated infrastructure upgrades and job opportunities. At least one community will become a hub for Parks Canada, likely requiring reception centres, boats, storage and hotels.

“We do want people to see the beauty of the EMR, learn from our culture and come to our communities,” said OtterTétreault. “That’s the main driver for me personally. I said to youth imagine your job is to get on a boat, knowing you’re

protecting the environment and teaching people about your culture.”

Participants suggested the NMCA represented an opportunity to share a Cree perspective of history with Cree place names and activities that promote the Cree language and legends. It could serve as an outdoor classroom, improving access to the land.

Some shared concerns that the region’s remoteness would limit arrivals regardless of a NMCA while others felt a tourism influx risked overwhelming local capacity or threatening environmental and cultural security. However, more were optimistic about the potential for summer camps and niche adventure or eco-tourism.

Expanding access to islands, perhaps even a landing strip on Charlton Island, could support both tourism and archaeological projects while growing Land Keepers and other conservation programs. Exploring James Bay’s mysterious waters could inspire biologists and possibly identify exciting new food sources.

“Coastal people could harvest certain species of fish for commercial purposes,” suggested Wapachee. “Canada was open to that. On the west coast, they engage with the Haida for commercial fishing. If there’s an interest, we would go in that direction.”

With Cree leadership building relationships with neighbouring Indigenous nations, the NMCA may be an opportunity to collaborate with the Mushkegowuk Council on the other side of James Bay. The Deputy Grand Chief was invited to speak at their recent NMCA announcement.

“I congratulated them and opened the door for both groups to work together to protect all the James Bay and Hudson Bay areas,” Wapachee shared. “We have common issues and interests – this is one of them. I’m hoping we can work together on a high-level committee that would oversee the west and east sides of James Bay.”

Negotiations with Canada will commence in the fall, likely with further consultations to identify sensitive areas. Otter-Tétreault hopes that next year “the real work will get started.”

“We’re just expanding our protected areas that are significant to the Cree,” said Wapachee. “We use those rivers – Rupert, Eastmain, Chisasibi, Great Whale – that flow into James Bay, Wenipaahk. Our actions flow out into the world. We must embrace our sacred responsibility preserve the area and promote our way of life.”

by Joshua Janke

Three years ago, on July 26, 2021, Mary Simon was sworn in as the 30th Governor General of Canada, becoming the first Indigenous person to hold the position.

As Governor General, Simon represents the Crown, King Charles III, in Canada. While her duties are nonpartisan and largely ceremonial, the role of her position is to uphold the traditions of Parliament and other democratic institutions.

Born in 1947 in Kangiqsualujjuaq, Simon returns home to Nunavik often, where she enjoys playing the accordion, berry picking, and being in nature when not working in Ottawa and visiting communities across Canada.

Beginning her career as a broadcaster for CBC North, Simon was an Inuit representative during the negotiation for the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement of 1975 as well as the patriation of the Constitution in 1982.

The Nation (TN): Your Excellency, you have had a remarkable journey to becoming the Governor General of Canada. Can you share with us how your career path led you to this prestigious position? Specifically, what were some of the significant moments and roles that prepared you for this responsibility, and how did you navigate the selection process?

Mary Simon (MS) : The first time I worked full-time for the government, I was 28. That’s when I was elected to an organization board. I was quite young and getting involved in regional politics up in Nunavik, in northern Quebec, which is where I come from, a place

called Kuujjuaq on the northern tip of the province.

International work was fascinating for me because it provided me with a new vision of what this world was about. I got to meet other Indigenous people from Finland and northern Russia, and we had so much in common, even though we are all very different in terms of culture and language.

Two and a half years ago, I received a call from the government office. I wasn’t even supposed to tell my husband that I was shortlisted for the position with two other people. It took two or three months, and it was very confidential and nerve-wracking because I knew my life would change forever.

My time in Denmark gave me an idea of what to expect if I got the position. The diplomatic life is very different from everyday life, and I knew that my experience in Denmark would help me out a lot. I got through the interviews, even though I was very open about not speaking French. I was bilingual in English and Inuktitut, and I thought this might be the one barrier that would stop me.

Anyway, I got the job. One day, the Prime Minister called, and after talking to me for 45 minutes, he said something like, “Well, you know why I called. I wasn’t going to do this, but I’m doing it right now. I’m offering you the job as Governor General.” I was so happy I screamed.

TN: Can you tell us more about your upbringing in the Arctic and how it has

influenced your journey? What lessons did you learn from your family and community that continue to guide you?

MS: It has been quite a journey, from living in the Arctic with very little, in a sense. My grandma was a nomadic person; all Indigenous people were nomadic before the colonization process. My grandma taught me so much about my history. My background is very rich, but not in a materialistic way. The Inuit moved from season to season.

In the North, we are a people of the land. When you speak of a tight-knit group of people covering a vast area in the Arctic region, living a nomadic way of life and following the seasons and the animals, this is something special we have kept with us.

TN: As Governor General, you have emphasized several key priorities. Could you elaborate on your focus areas, particularly regarding reconciliation and the empowerment of Indigenous communities? How do you envision these efforts evolving, and what steps do you think are crucial for meaningful progress?

MS: Reconciliation is a difficult issue. People don’t like to tell stories, people don’t like to tell who they are, but that conversation has to take place. If we’re going to have a country that is premised on issues like racism and violence, we have to understand the country in a much better way, and people need to know who they are.

Indigenous people are always saying they want to run their own affairs, so this arrangement should be made while staying in Canada, not outside of Canada, because we’ve evolved so much over 150 years. Turning the clock back may not be possible, but there are many self-government agreements that are being signed now in Canada, which allow Indigenous people to have a lot more authority over their own affairs while living in the country.

The problem is that the services Indigenous people get aren’t enough. When you look at the communities, clean water access and health systems, we need to do more for the northern regions, which continue to have limited access to these essential services. Improving internet access, for example, would allow for an increase in mental health services for northern Indigenous communities due to the vast improvements made in online mental health services in Canada since Covid-19.

I’ve always felt very strongly that people need to understand that our body and mind are together and one. People think they are separate, like you’re physically sick or you have mental health challenges. In the North and across the country, the inequality between the two health services is quite large. There needs to be more of a balance between physical health services and mental health services because if you’re mentally not well, then you are physically not well.

TN: Education is often mentioned as a cornerstone of your agenda. How do you see education transforming the future of Indigenous youth and the broader Canadian society? What specific changes or initiatives do you believe are necessary to ensure a more inclusive and accurate representation of Indigenous history and culture in our educational system?

MS: Education is one of my priorities. Education is key, and the role of teachers is very important. I’m using education not just in the academic sense in schools, but to educate Canadians about the country, about who Indigenous people are, and what happened in the past.

There are no history books that truly reflect this. Every school should teach the real history of the country, not in a negative way, but just the history itself, what happened over the last 150 years.

The part about Indigenous people is absent in many of the history books. A former prime minister grew up over a hill, and there was a residential school not far from his house, and he never knew. It was an issue that was never brought up, so the history of the country is important to teach in a true and more comprehensive way. Including Indigenous history is crucial.

The role of education is very important. To get a job these days, most people want you to have a post-secondary education. In the early days, it wasn’t so much about that, but now it is. A lot of kids in the North face challenges; for instance, they go to school in Inuktitut for the first three years, then after Grade 3, they are expected to switch to English or French. This sudden switch creates a situation where, by Grade 9 or 10, many can’t catch up and drop out. This type of thing in the North has to change so that kids don’t face these problems.

TN: Climate change and food access are pressing issues in northern Quebec and across Canada. How are these challenges impacting Inuit communities, and what measures do you think are essential to address them? How can traditional knowledge and modern technology work together to ensure food security and sustainability?

MS: Access to food is of utmost importance. I just came back from one of the northernmost communities alongside the Hudson Strait, and there was great concern about how climate change was affecting the community’s ability to hunt and fish. Traditional knowledge is a very solid knowledge base, but with the changes in climate, things like weather and seasonal harvests become harder to predict. In early April, the hunters were telling me that the seasonal shift was two months ahead, and the sea ice is already melting like it does in June. Because this directly affects access to food, finding solutions should be a

priority. We can help people adapt to the changes without giving up who they are, without giving up their culture, and without giving up their language. There are new technologies to help people who need to go out and hunt for food.

All humans need protein in one form or another every single day, and in the North, it’s meat and fish that we depend on because when you go into the store, there’s hardly anything there. People really have to go out and hunt for their food, so to me, food access to northern communities must be a priority.

There are lots of other inequalities. Housing is a big issue, as it is across the country these days, but in the North, it has been bad for many years. Lack of policy has been terrible. The inequality of housing is a big issue for governments in the North, even to the point where now, because of climate change, the permafrost is melting, and the houses that were built on it start to break and crack as the earth melts and shifts. There’s no way of helping them fix those problems because there’s no funding or help for them to rebuild in different locations.

TN: Adjusting to life in Ottawa must have been quite a transition. Can you share your experiences moving to the nation’s capital and how you balance living between two cultures? What has helped you stay connected to home while fulfilling your duties as Governor General?

MS: A lot of my family and my grandmother’s sisters were relocated to the high Arctic to live in another community by force. There were a lot of relocations happening in those days.

So, when I moved to Ottawa, I started living in this huge house – it’s a beautiful house with a lot of culture and some history – and it was an adjustment for sure, but I have adjusted before. I can live in one culture one moment and then go up North and live in my own culture the next, so this transcending of both cultures makes me very fortunate. Being able to stay connected back home makes it easier living here in Ottawa.

Do you know that the Nation is also available in e-Edition?

As readers continue to shift to digital reading, newspapers are evolving to engage with readers in new ways.

The Nation can be read cover to cover, on Issuu, straight from the Nation website.

It's exactly like the print magazine. Past issues, as far back as 2018 can also be read on the Nation website. All issues are available for download.

You are travelling, even to Timbuktu, and cannot pick up a Nation copy? Maybe you prefer to read on your device?

The Nation has you digitally covered. Check us out!

Here’s another edition of the Nation’s puzzle page. Try your hand at Sudoku or Str8ts or our Crossword, or better yet, solve all three and send us a photo!* As always, the answers from last issue are here for you to check your work. Happy hunting.

by Sonny Orr

plat! Another large moth collides with my windshield as I cruise down the Billy Diamond Highway. I activate my windshield wipers and they distribute the dead insect around, adding another layer of slime to the already wellsmeared glass.

I pump on the wiper stalk only discover there’s no more cleaning fluid left. With my vision of the road severely impaired, I stop and look for any liquids to throw onto the windshield. I find one of my hydrating drinks and splash it on the wipers and lo and behold, it cleans off the grime. Hmmm, I think, I’ve accidently discovered a new solution that might take the world by a storm. Will it clean out my guts, too?

A few hundred kilometres later, I’m in Matagami. Thankfully, I could scrape everything off my windshield at a closed gas station and then continue to my destination. Halfway to Rouyn, I finally come across a gas station and buy some fluids and gas, and head to the hotel where I check in at 3:30 in the morning.

The dozing hotel clerk stirs, then jumps up and hands me my room key. In the room, I literally crawl into my bed. Sleep comes instantly and so, it seems, does the alarm I set – as if my sleep lasted only a few seconds. I shower off the fatigue and notice that my hair has curled up into an impossible mess. Oho, I say to myself, there’s some bad weather coming.

My hair has always acted like a natural barometer, warning me of upcoming weather patterns. It was an easy indi-

I am a master of logistics, but only when things go perfectly

cator – smooth straight hair meant nice weather and curly meant lousy weather.

I head to the convention centre to find out I missed a super thunderstorm which affected the internet and electricity over a wide area. The conference continues without a hitch and after a nice banquet, I crawl back to my room and lie down.

I wake up a few seconds later to find out that I’m late for breakfast. So, I grab a quick coffee to shake off the cobwebs around my eyes.

Again, the conference continues without any mishaps or delays and I’m back to my normal self. This time I dress a little lighter as the temperature soars to unbearable heights (at least for me) and I thank the inventor of the air conditioner.

I check on my vehicle, which hasn’t moved since I arrived, and air out the heat that has accumulated over the past 24 hours. The seat could have doubled as a barbeque, but I endure it long enough for the wind to blow the hot air out the

windows. Once it’s cooled down, I head back to my room, where it’s comfortable enough to think and breathe.

As I plan my return trip, I think of the conference. It focussed on logistics, of which I am a master. Often, I get labelled as a perfectionist traveller, but I know the woes of not being prepared. A simple thing like parking nearby can be a deal breaker. Can you imagine carrying loads of shopping several blocks to your vehicle while trying to wipe the sweat off your brow? Very difficult.

Planning for travel may seem an ordinary thing. But when an entire conference is designed to improve logistics for a large company or organization, you know, it’s about controlled pandemonium. Yes, I am a master of logistics, but only when things go perfectly. And in the North, nothing ever does go the way you want it.

Signing off from the middle of Abitibi storm country, I remain curly haired.

There has been some good news lately in honouring agreements and righting wrongs when it comes to Indigenous peoples on the James Bay coast. The big news was the announcement by Indigenous Services Minister Patty Hajdu of $1.2 billion for the Weeneebayko Area Health Authority (WAHA) for their Hospital Redevelopment Project.

This funding will go towards multiple developments including a new hospital, administrative offices, staff accommodations and an ambulatory care centre on Moose Factory Island. In these days of creeping privatization of our healthcare system it is good to see our governments investing in public healthcare.

In addition to the $1.2 billion federal investment, this will go with the $1.3 billion Ontario had already committed. Also recently announced was an additional $44 million from the Ontario government to ensure that this construction remains on track. In 2018, the federal government had committed to provide $158.4 million to support the construction of the new WAHA hospital. There was a delay in getting things moving and finally through the efforts of many stakeholders the funding was announced.

The WAHA takes its name Weeneebayko from the word we use to refer to James Bay. The organization provides vital healthcare services to people on the eastern James Bay and Hudson Bay coast.

My parents Marius and Susan Kataquapit were both involved with our local hospital services in Attawapiskat. They always reminded us of how important it is that our communities have modern services. They grew up in a time when any serious injury or illness meant life or death because no modern medical facilities existed in the community.

Mom worked in the kitchen and dad worked as part of the maintenance department at the original St. Mary’s Hospital in

by Xavier Kataquapit

In these days of creeping privatization of our healthcare system it is good to see our governments investing in public healthcare

Attawapiskat. They later moved on to the new hospital established in the 1980s. They also lived for a time in Moosonee and saw how important the main hospital was in Moose Factory. They reminded us often that at one point it was such an important facility that it took in patients and clients as far north as the Inuit territory. Dad got to know so many Inuit at the hospital that he learned a little of their language.

In my own experience, I spent a month at the Moose Factory hospital during the annual spring breakup when I was seven years old in 1983. I had broken my leg that winter and since I was still recovering with a full leg cast, my parents couldn’t properly care for me at our wilderness camp as there was the danger of possible flooding.

I recall the huge open rooms of the old hospital and the separate areas they moved us to every morning to sit in the sun surrounded by windows. Little did I realize that the hospital had been built as

a tuberculosis sanatorium to help patients recover from the illness.

WAHA said in a press release that the new health campus will replace the 75-year-old Weeneebayko General Hospital, Canada’s oldest unrenovated hospital. This is welcome news for the health of everyone on the James Bay coast.

This was all made possible through the dedication and advocacy of so many people who saw how important it was to provide such vital services to people on the James Bay coast. In my parents’ time, they taught us that these critical medical services are important to establish and to fight for.

As WAHA president Lynne Innes stated, “In the spirit of truth and reconciliation I am thankful and appreciate Canada in fulfilling their commitment to our new healthcare campus in Moosonee and ambulatory care centre in Moose Factory. This is a pivotal step to ensuring the health, safety and dignity of our First Nations communities.”