7 minute read

COVID-19 Vaccine Communication Strategies

Tracks COVID-19 Vaccine Communication Strategies

By Elizabeth Moore, NATM Tracks Editor

On June 22, 2021, The Manufacturing Institute, the workforce development and education partner of the National Association of Manufacturers, hosted a webinar covering various communication strategies regarding the COVID-19 vaccine. The Manufacturing Institute partnered with the University of Florida, a leading research institution, to distribute a nationwide survey. They chose participants that reflected the population of manufacturing workers to gain insight into the industry’s opinions and actions regarding the COVID-19 vaccine. The webinar summarized these results and provided tactics to help manufacturing employers reach employees.

As of this writing, roughly 50 percent of Americans have been vaccinated, which is still 20 percent lower than the White House goal of 70 percent. In addition, the Sun Belt and Rust Belt regions of the nation, where the majority of US manufacturers are located, trend lower in vaccination rates than other areas. With this in mind, there is still much work to be done to increase vaccine confidence, reopen the economy, and protect families and communities.

Before many of these strategies can be employed, it is important to understand why people are choosing to forgo these widely available and free lifesaving vaccinations against COVID-19. There are many factors that can contribute to an individual choosing not to get the vaccine. These reasons mainly fall into three different categories: information, access, and hesitancy.

Information Factors

• Information fatigue/pandemic fatigue—Twenty-fourhour news cycles, social media, and many other forms of communication can drive this type of burnout. Many are just simply tired of hearing about the pandemic and related effects over a year into it.

• Scientific literacy levels—Not everyone has the same educational background, and often, scientific texts can be complicated and difficult to understand. Not all information on the vaccine is presented in an easy-to-understand format for everyone seeking knowledge.

• Language access—Again, not all information is accessible. Specialized vocabulary or jargon can make reading in a nonnative language difficult or impossible, and translations are not always readily available.

• Inaccurate or misinformation—There are many hardworking individuals and organizations that are trying to put a stop to misinformation campaigns aimed to derail vaccination efforts. But information, and false information, spreads fast in the digital age. All it takes is one tweet or Facebook post with false information to dissuade members of your community from becoming immunized.

Access Factors

• Inconvenience—Many don’t have the privilege of taking time off work to receive the vaccine, whether that is time for the appointment or time off for any side effects that may occur after receiving the vaccine. Others don’t have adequate child care or elder care that would let them take time away.

• Confusing Systems—For many, finding a vaccine distributor, booking an appointment, and other logistics can be difficult, especially when receiving information from multiple conflicting sources.

Hesitancy Factors

• Low perception of personal risk—Some don’t view themselves as at risk for contracting COVID-19 or passing it on, so they don’t think they need to get vaccinated, which is a false and dangerous narrative as healthy and young individuals alike have become dangerously ill.

• Distrust in systems (health, politics, media, historical behaviors related to race, etc.)—Some people are distrustful of the systems in place because they have been hurt in the past or have seen others get hurt.

• For example, from 1932 to the 1970s, the Tuskegee

Syphilis Study conducted by the United States Public

Health Service (PHS) and the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) told African American men who were infected with syphilis that they were going to be treated. Then, those same men were given placebos and other procedures under the guise of treatment when in reality, the purpose of the study

was to watch the natural course of untreated syphilis. As a result of the study, 187 people either died or had lifelong battles with syphilis and its effects. This, along with historically racist medical treatment and care, creates a distrust of the American health care system by minorities.

• Perception of loss of freedom or rights—Some may feel that their choice in the matter is being taken away, so they are more hesitant to get the vaccine.

• Vaccine not seen as a social norm—In some communities, not receiving vaccines (or other medical treatments) is a point of pride. In other communities, going to the doctor or receiving preventative measures or treatments has a negative connotation.

• Lack of confidence/low perception of the safety of the vaccine—People may not have confidence in the vaccine or may not know enough about it to judge its effects, so they air on the perceived side of caution and do not get the vaccine.

Many feel that because the vaccine was developed rapidly that it could be dangerous. The COVID-19 vaccine has been ten years in the making with previous work and research done on coronaviruses such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and the middle eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012.

Although these barriers may prevent some from receiving the vaccine, they are not insurmountable, and many have chosen to receive the vaccine to protect themselves, their communities, and help return the world to a semblance of normal. There is still work to be done though, and employers can play a key role in disseminating information and providing the access necessary to get their employees and communities vaccinated.

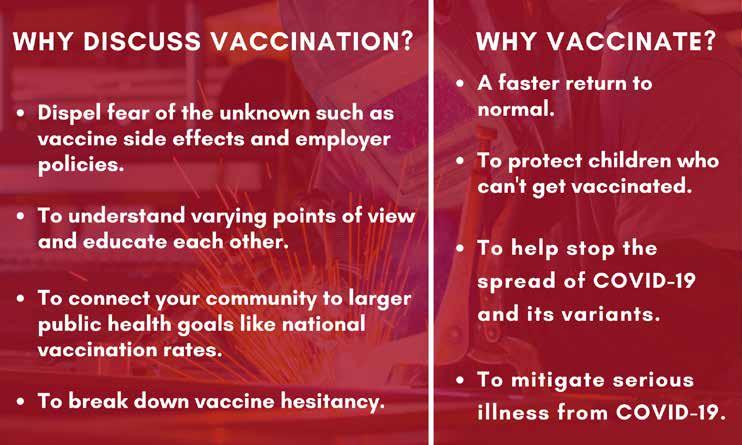

Below are some suggestions to help remove some of the barriers discussed above.

Remove barriers to vaccination

• Provide PTO, childcare, or ride vouchers to employees who need to take time off to get vaccinated.

• Partner with community organizations to offer multiple sites for vaccination. The workplace, doctors’ offices, clinics, pharmacies, and grocery stores may all be locations you can set up vaccination sites. • Offer vaccinations to the entire family over the age of 12 (per current vaccine eligibility requirements).

• Reduce the uncertainty of what to expect. Find out what reasons are driving hesitancy in your company and then address them.

• Offer administrative help to those who need assistance navigating registration systems or other logistics.

Highlight trusted messages and messengers

Trusted messages and messengers may be different people depending on who you want to target. Inother words, vaccine hesitancy is not a one-size-fits-all concern, so reduction strategies cannot be one-size-fits-all either.

For example, of those who participated in the survey who were not vaccine-hesitant, 41 percent trusted the CDC, and 40 percent trusted local health care professionals. On the flip side, of those who answered the survey who were vaccine-hesitant, 60 percent trusted their family, and 40 percent trusted their close friends. The key is to find the trusted messengers within your community and use them to help spread information. Once you have found trusted messengers, the tips below can help you communicate effectively:

• Practice two-way empathetic communication. Listen to what is being said and try to understand where that person is coming from.

• Share straightforward information that is repeated often through multiple mediums (i.e. posters, emails, conversations, etc.)

• Use positive emotions like hope, pride, humor, or love when communicating. Shame will not work.

Customize messages

Once the trusted messengers have been established for the organization, the focus can move to customizing the messages that are to be shared. There are many tools that can help with this, but one important one is psychographics.

Psychographics go hand in hand with demographics. While demographics tell who a person is (age, race, geographic location, gender, etc.), psychographics tell how people see the world and deal with identities. They can help discern what a person thinks is right and what is wrong. Psychographics are key to finding what messages will resonate with your target audience.

Below are some other ideas on how to customize messages so you can communicate effectively:

• Connect larger public health goals with the immediate community. Distance leads a person to “checking out” and not acting.

• Co-host vaccine sites with local organizations like churches or civic groups and involve local doctors and medical professionals.

• Present communications in a range of languages, especially languages reflecting your workers’ primary languages. Also note that translations may not work. Providing resources in other languages is not only about comprehension but about being seen and acknowledged.

• Be transparent with the sources you are using and why.

Be explicit on why you chose that source. Don’t assume everyone has the same familiarity with the discovery processes and credibility of the source. This article is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to communication surrounding COVID-19 and the vaccine. It is intended to provide suggestions and tips on how to communicate with your workforce and vaccine hesitant individuals.

The webinar this information was compiled from was part of the This Is Our Shot Project by the National Association of Manufacturers and their education and workforce partner, The Manufacturing Institute. For more information on the project, visit www.TheManufacturingInstitute.org/research/thisisourshot. At that link, you can find resources like “COVID-19 Vaccine Conversations Guide” and “Protecting the People Who Make America” which goes in depth on the survey discussed in the article and provides a guide on building trust and confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine. If you have questions about the information presented here, visit www.NAM.org/coronavirus/creators-respond.