This time, the Nass experiments with substances. We go a little too far. We get faded.

The Nassau Weekly

4 6 8

THE DRUG ISSUE

High on Laced Weed on Princeton Campus

By Anonymous

Designed by Jasmine Chen and Alexander Picoult

Sexy Pablo

By Mariana Castillo

Designed by Vera Ebong and Chas Brown

Old Friend

By Harry Gorman

Designed by Vera Ebong and Chas Brown

The Nassau Weekly Anonymous

The other week, a dealer–who up until this point had seemed demure and cryptically cosmopolitan in this very European way–messaged me, “In years past, I had everything all the time.” Me and my friends laughed for a while. Then, things got quiet, and we spent the evening very sober.

Designed by Vera Ebong 9 13 15 20

By Multiple Contributers

Designed by Vera Ebong and Hannah Mittleman

A Note on Drugs & Discipline from an Overcautious Schoolgirl

By Melanie Garcia

Designed by Hazel Flaherty

On Going Off Antidepressants

By Anonymous

Designed by Jasmine Chen

The Modern Cowboy’s a Guy Who Smokes Weed: A Treatise on Chronic Daily Use

By Anonymous

Designed by Vera Ebong and Chloe Kim

My Drugs/Diamond

By Ellie Diamond/Stephanie Chen

Designed by Jasmine Chen

Crossword

By Simon Marotte

The Nass “Drug Issue” split off from the smashhit “Sex Issue,” released last fall. With that issue, we conducted an experiment posing the mostly simple question, “Do Princeton students–Nass contributors in particular–still have sex?” To our relief, the volume of high-quality, well-substantiated submissions validated our hypothesis. Herein, we pose a similar question: “Do we still use drugs?”

The “Sex Issue” afforded us the convenience of precedent. We could consult a number of prior Sex Issues from the archives lovingly tended by our historian (then Julia Stern ‘26, now Jonathan Dolce ‘27). The “Drug Issue” doesn’t share the same pedigree, and it’s easy to imagine that, in years past, the Nass had everything all the time. Judging from the really wonderful contents of this edition however, I’m willing to presume that we have an eager group of drug-users among our masthead and contributing team: everything from benadryl to bath salts.

These twenty pages constitute the most comprehensive, literarily significant account of drug culture at Princeton University. It’s also a lot of fun. You’ll enjoy it.

This Week:

Verbatim:

About us:

4:30p Julis Romo

Last Lectures: Rayna Harris

7:30p Drapkin Studio

Sisyphus, a new play by Jessica Lopez ’24

2:00p Woolworth Princeton Undergraduate Composers Collective

2:00p Palmer Square 2024 Solar Eclipse

7:30p Drapkin Studio

Sisyphus, a new play by Jessica Lopez ’24

8:00p Wallace Theater

She Loves Me, a Classic Broadway rom-com

3:00p LCA Forum

Opus x Penn Sforza

8:00p Drapkin Studio

Theater&...math, a reading of a play-in-progress by Cooper Kofron ’24

4:00p Simpson

Cambridge University, Pembroke College Study Abroad Info Session

11:00a Firestone Plaza Spring 2024 Campus Farmers Market

12:30p Chapel After Noon Concert

7:00p Jones

Through the Looking Glass: Slavic Animated Films

4:30p ComSci Building Inside ChatGPT: Startups & AI With the World’s Most Powerful Company

1:30p Firestone Walks for Writers

For advertisements, contact Isabelle Clayton at ic4953@princeton.edu.

Overheard on ground floor Shrewdfriend,leavingnopin standing: “Over the weekend, I met her long-distance situationship. I just knew he did bowling. I just knew it. I was right.”

Overheard during love song

Self-reflector: “I listen to love songs and think about myself.”

Overheard in girl quad Justagirl: “You look like a slut.”

Aspiring,ambitiousslut: “Dress for the job you want.”

Overheard in Newark security line

ROTCkiss-ass: “The only reason I would ever travel to Europe is to die in an international conflict.”

Overheard during production night

DisillusionedNass-reader: “I thought what they publish was real.”

Overheard in history seminar

RealAmerican: “Superbad has helped me more than the Declaration of Independence ever has.”

Overheard past midnight

Wantstobeperceived: “How do you feel about me in intense detail?”

Perceiver: “I think you’re sensitive yet strong. You simultaneously have a richer inner world and social life, which is quite rare.”

Overheard at BCG info session

BCGrejectee: “What’s her major again? Nepotism?”

Overheard in U-Store Preppygayman,inpastels: “He definitely wore a lot of neon in high school.”

Overheard in girl quad Ambitiousslut: “I have to get undressed to go out.”

Overheard in SPE101 BurntoutSpelling-Beekid: “I always misspell vinyl because I get too excited about the ‘y’ and put it first.”

Overheard on GroupMe

“Chill”woman: “I am very easy maintenance and would only require a few meals a week, some occasional public outings where it’s clear that we are not just friends but not in a weird way obviously, and casting the once in a while intimidating glance at any potential unwanted uncomers (aka, Ex Boyfriend).”

Overheard on land Pelagicsoul: “I’ve been yearning for the open sea. Do you have any swashbuckling, nautical music to recommend?”

Submit to Verbatim

We meet on Mondays and Thursdays at 5 p.m. in Bloomberg 044! Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Got Events? Email John Emmett Souder at js0735@princeton.edu with your event and why it should be featured.

The Nassau Weekly is Princeton University’s weekly news magazine and features news, op-eds, reviews, fiction, poetry and art submitted by students. There is no formal membership of the Nassau Weekly and all are encouraged to attend meetings and submit writing and art. To submit, email your work to thenassauweekly@gmail.com by 10 p.m. on Thursday. Include your name, netid, word count, and title. We hope to see you soon!

Read us: Contact us: Join us: nassauweekly.com

Email thenassauweekly@gmail.com

thenassauweekly@gmail.com

Instagram & Twitter: @nassauweekly

Laced Marijuana on Princeton Campus on High

“Everytime I looked down at my cigarette, it was just as long as it had been the last time I checked. She then moved on to telling me about her internship.”

By ANONYMOUSIsomehow never really outgrew that juvenile middle school mentality that drugs are cool. I thought that needing a klonopin before bed, ketamine for visits to the movie theater, adderall before the library, weed before class… made me more enlightened than my peers. I was hacking life. In reality, this didn’t make me interesting, or superior. It made me a person with a substance abuse problem and, truthfully, a little bit of an asshole. But, when I got to Princeton, I was immediately curious what I could find by way of drugs on campus. It was hard to gauge what the drug culture here was like. People looked at me like I was a crack addict, just for smoking a little pot. But then, I was regaled with promises of frat boys snorting coke, heavyweight rowers taking ketamine, and Terrace members tripping on salvia. I spent my nights on the street peeking around for the storied Ivy coke room or looking for a sweaty, wide-eyed stranger who would perhaps be feeling generous. I was hoping to uncover the Princeton drug scene, since nothing makes you feel more like an addict than snorting ketamine alone

in the bathroom at a party. This attitude left me considering whether I should revisit the idea of finding an addict support group on campus, as my parents had suggested before I got to Princeton. Instead, I decided to make a far more mature choice: stick to weed and alcohol (except for on very special occasions) and avoid a stint in rehab. Perhaps not a historically successful approach, but definitely one more appealing than sobriety.

My plans to avoid all drugs other than weed failed a few months after I made them but, for once, not on purpose. As a freshman at Princeton, finding decent weed on campus felt impossible. Also impossible? Going to the street sober and having anything close to a good time. So, having smoked the ounce I’d brought from home at the beginning of the semester, and exhausted all my options by way of overpriced campus drug dealers and delta 8 from the kiosk, I gave in and messaged Dr. Feelgood (I changed his name, but picture something just as stupid). Dr. Feelgood had approached me on Nassau street a few weeks ago, promising me “the good shit” and handing me a business card with only his Snapchat username on it. I had always prided myself on only buying from top shelf dealers, who did their business exclusively on Signal and who’s bud menus promised every strain, tincture, and edible available on the continent. But, desperate times.

I rolled up a joint of Dr. Feelgood’s finest, smoked it, and

took myself to the street, ready for a standard night of cigarettes on the patio, top 40 hits, and mingling with people that I don’t necessarily like. Once I got to Ivy, things started to feel a little less than standard. The banter from the bouncer felt threatening, not funny. The coat room felt more claustrophobic than usual. I couldn’t understand any of the words in the songs. I realized I was maybe a little more high than I intended to be and smiled to myself, deciding that maybe Dr. Feelgood really did have the good shit. Stepping

onto the terrace, I ran into some girl who was in my writing seminar. Happy to see a familiar face, I lit a cigarette and started talking with her, but everything she said struck me as insane. She was telling me some story about going to an alpaca farm as a kid, and I really hated her story. Everytime I looked down at my cigarette, it was just as long as it had been the last time I checked. She then moved on to telling me about her internship. Normally, when people start talking about things that make me feel inferior, I immediately start thinking about how I’m actually so much better than them – sure, I knew I was lying to myself, but this method generally worked for warding off an existential crisis. My defense mechanism was a little harder to employ in my hazed state, and I was ready for the conversation to be over. And it felt like my cigarette would never be done. With every puff, I could feel the

smoke seeping into my lungs and visions of myself in a hospital bed, pale and hooked up to a ventilator, danced in my mind. So, I committed a cardinal sin and put out my cigarette before having smoked all of it. After about five minutes of chatting, (which, in party time, is an eternity) I told her it had been nice talking to her and that I was going to find a drink. “Oh, I’m not interesting enough for you? You’re sick of me already?” I laughed, thinking she was making a joke, but she just glared at me. I felt sweaty under her gaze. Then, she smiled at me, and shoved me on the shoulder, I guess in a way that was meant to be friendly but the second she moved her arm towards me I recoiled from her touch, because why would I want this alpaca petting freak’s arm on me? I fell backwards, in the way that people in comics do when they slip on banana peels. Suddenly, I was surrounded by people, including a security guard. “Dude, if you’re too wasted, then leave,” an upperclassman I didn’t recognize said to me.

My usual cure for being too high was to get a little drunk, but this case seemed far more dire than one that could be fixed with a few watered-down beers. The entire party was tilted on its side. Dance floor makeouts looked pornographic, and horrified me. The music felt oppressive, and the dancing cartoonish. I could see it all so clearly. Everyone’s auras were violently swirling around them. I was seeing every person for what they were. Insidious, robotic, needy, social climbing, lonely, embarrassing. I stared at the room, so clearly full of insecurities, lies, and tragedy. Being at Princeton, with all its bizarre social hierarchies, affiliations, and priorities that to me seemed entirely fucked-up, often left me wondering: is everyone around me crazy, or am I the crazy one? Neither option felt entirely promising but, early on into my time at Princeton, I decided it was

the former. I walked around campus, convinced I was more enlightened than my peers, more interesting, more down to earth. I didn’t care which eating club I was in, or how I planned to spend my summer, nor did I compulsively check my LinkedIn.

I went up into the bathroom and looked at myself in the mirror. My makeup clownish, my outfit tryhard. I couldn’t stop thinking of every interaction I’d had in my time at Princeton in which I’d been fake, doing anything to ingratiate myself with the people I thought were cool. Everytime I’d texted my one upperclassman friend asking for a list spot, or told acquaintances that I passed walking up Elm “we should get a meal!” a saccharine smile on my face. I felt like throwing up. I wasn’t above Princeton’s crazy, I was wholly immersed in it. Deciding that the mirror was too

much for me, I went into a stall. I sat down and started peeing. Then, the door swung open and someone walked INTO the stall. I just kind of looked at this girl, and she looked at me and then stepped out. I lifted my leg to hold the door closed, and then realized something felt weird. I looked down and saw that I had forgotten to pull down my underwear and was peeing into my underwear. Okay, what the fuck was going on? I wasn’t some freak who performed pratfalls and pissed herself at parties, even when I got high. Washing my hands, I suddenly had the most genius-like moment I’ve ever experienced. I knew something was weird about that weed. Its smell and taste had felt familiar, but I hadn’t quite been able to place it. When had I smoked weed like this? Then, my brain got so big it filled the entirety of the bathroom

and I realized: sophomore year of highschool, the dime bag from the park, the weed that tasted ever so-slightly like a baby’s diaper. The weed that had given me auditory hallucinations and had led me to throwing up into my best friend’s desk drawer. The weed we had concluded was laced. Fuck.

It was time to go home. I went intIt was time to go home. I went into one of the few unoccupied rooms at the party and sat on an armchair, waiting for my friend to take me home. I was ready to rip my own skin off. I sat, clutching the arms of the chair, afraid that if I let go, the fabric of the chair would peel off and the hundreds of ants I was sure were living in the chair would crawl out. As people walked in and out of the room and I sat there, picking at my skin and mumbling to myself, I realized maybe Princeton wasn’t crazy, but I was crazy. I felt stuck to the chair.

The next morning, I woke up, and, to my horror, was still high. The writing sem girl had texted me: “that was fucked up.” What? I went to church and wondered what I would do if the high never wore off, but eventually it did.

When I got home, I texted Dr. Feelgood – well, actually, I snapchatted him: “great bud, 10/10.” I still keep that Dr. Feelgood weed in my nightstand, should I ever need it. I guess the thought that I might one day need weed laced with bathsalts (or worse) is not a great one… probably one that I should introspect on, but I’d really rather not.

I was regaled with promises of frat boys snorting coke, heavyweight rowers taking ketamine, and the Nassau Weekly.

SEXY PABLO SEXY PABLO

“To Colombians, he was a terrorist. But in the eyes of the rest of the world, he’s a Criminal Mastermind. The question is, why?”

By MARIANA CASTILLOThe reader has surely known a scrawny, gangster-loving seventeen-year-old boy who fangirls over the King of Cocaine. Bring up his name and they can educate you on how he built his empire and became one of the richest, most powerful men in the world—and it doesn’t stop there. No, no, no. They know the fun facts too. They’ve watched the series, they’ve done their research—a simple Google search taught them about his hippos, his zoos, his palatial homes and elaborate prison breakouts. Hell, they also wrote an essay about his Robin Hood-like

is crude—maybe even a bit insensitive. Maybe Britannica hired one of these seventeen-year-old boys to write it.

Pablo Escobar, Criminal Mastermind. Now, scratch out his name and insert the name of the evil historical figure of your choice. The reader thinks of a certain mustached demon and screams at the page—now you’re being dramatic.

My attempt with that exercise is not at all to compare, but merely to illustrate my point. An Amazon search of Ted Bundy reveals a list of books and movies educating you with the stories of the women he killed; but type in Pablo Escobar’s name and you can purchase pretty posters with his face in all different sizes to hang in your living room.

To Colombians, he was a terrorist. But in the eyes of the rest of the world, he’s a Criminal Mastermind. The question is, why?

What sets him apart?

acts for class. They have t-shirts of his mugshot.

Britannica describes Pablo Escobar Gaviria as a “criminal mastermind.” You get through the list of riveting fun facts and the oxymoron easily flies you by. It’s an interesting choice of words. They immediately aestheticize, speaking to the phenomenal in a way that elevates the subject above reality. The words are also automatically exonerating—a criminal mastermind deserves a movie! And boy, Pablo has plenty. It’s the kind of term you would use to describe the actors in Ocean’s Eleven. It alludes to some elaborately genius, successfully executed plan. It makes Pablo’s reign seem like a Hollywood stunt. Like 111 innocent people didn’t violently blow up in the air on Avianca Flight 203 after his cartel stuffed it with dynamite.

Something about the description

I visited my family in Colombia last summer, and on the final day of our vacation, having saved the best for last, my uncle drove me to La Candelaria, the capital’s historic center. Walking on cobblestone streets, we peered at museums, government buildings, and beautiful colonial structures through the flight of well-fed gray doves. This was one of Bogotá’s main tourist destinations, and as we toured we inevitably stumbled upon a row of slanted souvenir shops.

They sold replicas of Fernando Botero’s classic works, black and white postcards of a perched Gabriel Garcia Marquez, intricately beaded native jewelry, and an infinite array of yellow, blue, and red—if the tourists were going to learn anything during their stay in our tropical paradise, it was the colors of our flag. Alongside this, crucified on the wall with pushpins and cables and the slightly bothersome vinegary smell of formaldehyde, were hats, t-shirts, posters, flags, and underwear. They were all pressed with the glinting mugshot

grin of world celebrity, superstar, synonym of all things power and luxury—his shirt glowed brighter than the White House in front of which he infamously stood. To some tourists in the store, this was the only real recognizable figure. They flocked—they’d been searching for Pablo Escobar’s delicious image since they stepped foot on Colombian soil.

The sight struck me. The day before, we had visited one of the most popular malls in the city. As we neared the ramp leading down to the parking lot beneath the mall, several men in dark green uniforms, rifles slung across their chests, signaled for us to stop. When our car approached, my uncle knowingly suffocated the brake and they lifted the hood of our car. “They’re checking for bombs,” he said.

Garnishing the mall’s perimeter were buzzing restaurants, neat office buildings, and drumming nightclubs. The damage that could be inflicted by a car bomb would be catastrophic—it also wouldn’t be the first crater drilled into Colombia’s scarred history. Amidst its abundant biodiversity, beautiful landmarks, and delicious food, war raged in the eighties and nineties as terrorist groups fought over the country’s resources—king among these, the Medellín Cartel led by Escobar.

Sadly, there’s still an undeniable nexus between that name and The Republic of Colombia, and the continued association of criminals like Pablo and our nation can be likened to phantom pain: The limbs that were rotted by drug trafficking were crudely amputated—as if by a saw and a biting cloth—with Escobar’s death in the nineties. But the stumps are suffused with electric shocks as Colombia’s reputation continues to be inextricably linked to its victimization, perpetuated by pop culture and the ignorance that continuously romanticizes such

drug lords. The wealth and power swirled into drug production create an intoxicating aroma that, upon inhalation, dizzies you into blindness—one need not ingest, snort, nor inject to feel tickled: the stories are drugs themselves. Even the name of their moguls, the idolized Drug Lord, is allusive to the divine. Terrorists become glamourized beneath the purple haze.

Odds are, those who wear Pablo Escobar’s face have no idea that in December 1989, his cartel set off a car bomb in front of the country’s Department of Security (DAS), killing over sixty people and injuring almost six hundred. Escobar’s cartel murdered countless politicians, presidential candidates, judges, magistrates, and journalists, and offered two and a half million pesos (a monumentally larger sum than the average minimum wage

of the time) for each policeman who was murdered. One hundred bombs were set off by the Medellin Cartel just between September and December of 1989, destroying public spaces from stores, to schools, and banks, inflicting a reign of terror that left people fearing for their lives every time they stepped outside. Escobar’s reign left an estimated fifteen thousand people dead and inflicted social and political tremors that still shake our nation.

That Pablo’s image is sold in the very country he terrorized is not due to a lack of conscience or ignorance. Most Colombians are aware of his crimes in the same way Americans are aware of 9/11. The catering to tourist demands is merely the recognition of a fact— drugs and their champions are sexy.

Pablo’s face sells. And the uninformed tourist, by nature, scoops it up and feeds it to his gangster-loving seventeen-year-old son, a poster to crucify the martyr to his bedroom wall.

The wealth and power swirled into the Nassau Weekly create an intoxicating aroma that, upon inhalation, dizzies Mariana Castillo into blindness— one need not ingest, snort, nor inject to feel tickled: the stories are drugs themselves.

Old Friend

“There might still be a picture of me and Sam on his fridge from that year. We’re wearing red caps, all smiles, and holding autographed baseballs in clear plastic cubes.”

By HARRY GORMANIstill live here. The couple who moved in are childless and I’ve stopped thinking about him. Sam lived right by the bus stop – he only had to walk twenty steps from his porch. His thermos clanged twenty times in a lumpy backpack as he tottered forth, a miniature sheep swishing back and forth from a chain fixed to its zipper, and when it snowed, his boots made twenty little footprints. In November, we heard sirens and saw blue lights on our way home, and the bus kept pulling over. It drove around the block three times before we turned the corner and pushed our palms against the windows. Outside, his house had opened its doors and coughed up a plastic-bundled person. Sam wasn’t strong enough to force the jammed latches open to slide the pane down, so only our frantic bus driver knew he was yelling until we finally parked, and his father hoisted him, thrashing about, into his arms. They stepped

towards his car and trailed behind an ambulance – the first time Sam rode without a booster seat.

My mother put me in a little black suit and dress shoes. She crouched down to face me and wrapped a tie around my neck. Are you gonna be okay? I wasn’t sure, but a dark line of mascara dripped down her face and she hugged me. She straightened my tie and pulled it tight to my collar.

There might still be a picture of me and Sam on his fridge from that year. We’re wearing red caps, all smiles, holding autographed baseballs in clear plastic cubes. Next to us is a flexing Nutzy the Flying Squirrel, who signed our hats after posing with us. Someone is behind the camera and speeding us home to B.O.B., asking if we had fun, flicking the brims of our caps down to our noses, and tiptoeing upstairs to bring us a bag of barbeque chips and a DVD we aren’t supposed to have. It’s midnight in an attic, the TV is humming, and his mother thinks we are asleep. I keep this night like a pearl.

It is every parent’s worst nightmare to outlive their child. My mother squeezed my hand in hers but pulled it back to cover her eyes. Something is wrong. She sobbed louder than anyone, and when I turned my head, Sam’s grandmother was looking at her, and then she looked at me. I feel lucky

to have known someone so kind. This was the last time I saw her –it could’ve been that the pursing of her lips was a frown, the pensive eyebrows a scowl, the dry eyes disapproving. I hope I’m wrong. When Sam moved away a year later, she’d refused to go with them and was transferred to an assisted living facility. And started to forget. And sometimes, pressed her thumbs into the palms of tall boys who gave her pills and scrambled eggs, and said It’s been so long since I’ve seen you.

His brother Cooper screamed You fucking alcoholic bitch at his mom. I cupped my hands over my ears and tucked my head into my sleeping bag, too nervous to wake a snoring Sam. Maybe he was awake, but if so, we never had it in us to talk about plates shattering and loud engines popping down the street. Scorched throats and roomto-room fury. Groaning staircases, jingling keyrings, and scuffed leather boots. Horripilation. I heard three key tones from the kitchen and the click of the phone back into the charging stand. The door must not have made a sound when he slinked back in.

If someone brings it up, Aidan Chapman will say I was on that bus and David Nguyen will say It freaked my mom out so bad we moved, but neither of them will mention Sam’s dad driving him

to school by himself for the rest of the first grade. They’ll say That was so fucked up, not that Sam lost ten pounds and couldn’t eat in the cafeteria with us. When they say This kid Sam-who-used-to-go-here’s brother overdosed, they will not see the look in his eyes when I, adrift in a sea of black fabric and shuffling waists above my head, lit by the lambent blue light of a stained glass window, smacked my forehead against his by accident and sent him crashing to the ground. But I reached down and grabbed his hand.

I helped him to his feet. Sam stumbled into my shoulder. Neither of us were wearing shoes that fit, and they wobbled while I held him. I closed my eyes, and when I opened them, I made a wish.

Scorched throats and the Nassau Weekly. Groaning staircases, jingling keyrings, and Harry Gorman.

The Nassau Weekly ANONYMOUS

Nass contributors share drug stories that are strange, funny, remarkable, heartwarming, or otherwise worth compiling.

Every drug tale always gets flattened into the same octagonally-shaped directional and this one’s no different, soft as any other, and made of peach-like fuzzy skin—if you squeeze it too hard, you’ll bruise it and the insides will get all sandy and gritty, like a fallen apple, and if you squeeze even harder it might shit itself and you’ll find warm feces drooling down your dominant palm, and if you inject it with all kinds of substances it’ll squirt red just like you or I—it stands in the vacuum of nostalgia, vastly idolized and unbelieved, but it needs only exist so adults with peeled nostrils and wet tissues get to say I told you so, exempting themselves from any responsibility… his name was BLANK—feel at liberty to scribble any name which suits your purposes—and he took some BLANK (you get it) through his eyeball (or his rectum and any other crevice with pores into his cellular soul), and he was never the same—though usually, he dies—the base of every drug soliloquy that bubbles out of mustached mouths and gets sprinkled into alphabet soups and slurped by wide-eyed children in an attempt to save them from the porous and wrinkly pit.

he’s absolutely blasted. I can see her a few tables away, grinning like a madwoman. Her eyes have that unfocused look, her hands lay clasped in her lap, her feet swing of their own accord underneath her. I can tell she’s in deep. It has her every sense commandeered, every inch of her body hums. I glance around the coffee shop and wonder if anyone can tell what’s going on with her. They must, it’s so obvious.

Since this isn’t the first time I’ve seen her like this, I’ve quickly come to recognize that specific grin, that specific gaze. I saw it walking back from the street the other night, and across from me at dinner, and lying prone on my floor. The thought has occurred to me to be concerned about how quickly she’s changed, but honestly, I’m starting to feel a bit drugged myself, looking at her. And besides, there are worse things she could do than getting drunk on the love of the boy sitting across from her.

Acrown of thorns placed on His head He knew that He would soon be dead

A friend of mine studies philosophy. He buys his shrooms from Russia, from an Etsy seller with no name. He hates women but loves gender; he loves Nietzsche and likes Schopenhauer; he’s anxious about war but nev er about death.

Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia!

Alleluia, alleluia!

“Slavic shrooms boost testosterone,” he said one day, sighing sorrow fully about how whatever species we secured wasn’t quite good enough. It was late and cold. He looked wolfish that day, gaunt, the way I remem ber him best. He emptied an entire jar of Vaseline onto his dad’s table and spread it into an even layer. The Amish maple had never looked more luscious, more decadent. We carved our names in the goop and laughed.

It was my last time doing shrooms. I’ve become able, purposeful, and direct, phoning him every month or so to get his thoughts on my philos ophy papers. Last I heard, he was learning calligraphy and sketching out mail bombs. It’s a good friendship, one of my best.

e skip, hop, and jump through the suspicious brush lining the pier. Broken glass and empty cigarette packs crunch under our feet as we walk towards the center, where a couple people fight with a generator. It is near dead silent. Some rave.

These boots were the wrong call. This entire outfit was the wrong call; a tube top and mini skirt was somehow not ample clothing for this August night. It would not have mattered what I was wearing anyway the only light on the pier was coming from the buildings across the river.

Everything about this night so far has been slightly disappointing. And then I am handed a dime bag and a key. And then two bumps of K are singing my nasal cavity as they go down. And then things are not so bad. Lights are flashing, music is finally playing, my boots are no longer pinchy, and I am dancing.

At some point, my friend disappears. At some point, she reappears, and she is soaking wet.

She takes off her shirt and wrings it out. I am too sedated to process any of this. And so I just keep dancing.

wo years ago, when visiting my parents during winter break, my mom informed me of a riveting development in her life as an empty-nester: she had taken to growing shrooms. My mom had been hesitant to tell me. Apparently she had started prior to my fall break, but thought I would be horrified to know. I wasn’t, just more intrigued. How had my mom–who only drank sips from my father’s occasional beers and whose most recent experiences from weed were during her chemo–been spawned into the suburban mom shroom scene? My mom informed me that a neighborhood friend had introduced her months ago to a new friend, a mom who had a shroom hobby. After hearing from this friend about the demanding needs of shrooms (and the benefits of microdosing), my mom grew interested in developing her own fungal farm; and under the guidance of her new suburban shroom sensei, she became mycelium mother. My mom was clearly quite animated about her new hobby and offered to show me her shroom room. After donning masks and gloves (to avoid contamination), my mom led me into the dark room that used to be my sister’s before college and held the fruits of her labor. My mom presented various Tupperware containers containing an array of shrooms of all sizes and life stages, and explained her relative success in growing each shroom strain. After her show-and-tell, I asked my mom the question lingering in the back of my mind: had she ever tripped? My mom assured me she had not and that she only gave her fully grown shrooms to her friend to be developed into micro-dosing capsules. I % certain whether I trusted her, but at the end of the day, I was just happy she had a new hobby.

he first thing I told my incoming roommates is that I have a Benadryl addiction. It is devastatingly true. Sometimes I will be on the brink of sleep and remember how much better this sleep would be if I popped a Benadryl and thus will groggily waddle to my selfmade medicine cabinet under my desk and pop a Benadryl.

My medicine cabinet largely contains Benadryl and many open boxes of Dayquil, as during the perpetual sickness of my freshman fall, I of ten took the Nyquil of the Dayquil/Nyquil boxes, leaving me with a large amount of opened boxes of likely slightly oxidized Dayquils. I feel it is im portant to note that I haven’t taken Nyquil yet for Benadryl-like purpos es. What’s more striking about my affection for Benadryl is not simply that I reach for it, but just that I have a whole lot of it. Right now, I have four boxes in my cabinet. It reminds me of how during COVID, everyone took all the toilet paper and how we still have a lot of toilet paper in our garage. That isn’t to say Benadryl is my toilet paper or anything (even I can’t possibly go through four boxes in the next nine months; by that I mean I’ve been exaggerating this whole time), but I do wonder what will happen when all these Benadryl expire. I presume I will still take them.

SMU. Snow Mountain University. Southern Millionaires. Sorority of the Melancholy and Underweight. Whatever the euphemism, it was here that I understood the weight of love in a Gummy.

“They’re 175 milligrams each, but half of them are duds. Take half and don’t worry.” Ok. There were three of us. If two of them were duds and one of them wasn’t, I’d be on Mars and my friends would be on planet Earth—Minecraft Earth.

Superbad. Never seen it. The movie just got better and better. Michael Cera, you know, his nose is a little crooked, but I think it enhances the movie. Michael Cera’s nose… that’s deep. Humans are so obsessed with symmetry, so duped by beauty! Emma Stone is too beautiful for this. Give me Michael Cera’s schnoz.

The characters started dating around and having awkward sex. Becca said something that made me want to throw up to Michael Cera. But this too was profound. Real stuff. Young love is clumsy, muddy, the colors of Hawaii’s rainbow!

And then I went to the bathroom and just one color was there, big and green, and un der my eyes. McLovin. Love. If Superbad is bad, I don’t want to know.

had a dream our airplane touched down in Candy Land. I jumped out of the plane and started eating the grass. I was high immediately. I spun in circles until I was blind diz zy, and it started snowing. Each snowflake that melted on my tongue made me shud der. I rolled in the snow down a hill to a lake of pure blue. I began lapping at the water like a dog. You don’t need fun to have alcohol. A leprechaun on a unicorn wearing a rainbow-colored unitard joined me, and we drained it. Then we smelled the salts at the bottom of the lake. We started floating and growing larger and larger until we were like blimps. The air was as crisp as an apple, and I bit out chunks of the sky. Jazz melted my bones. Honey on my tongue. The clouds were cotton candy, and eating them made me ecstatic and horny–I was salivating. I writhed in the air, longing for someone to hold onto, but the feeling passed, and I felt numb.

I grew and grew and kicked the Earth out from under me. I was floating in space until my feet grazed the floor. I didn’t know there was a floor in space. I walked over to the sun and tried to grab it, but it burned my hand. I poured some of the space water at my feet on it and it cooled down, burning red instead of white. I plucked it out of its orbit and ate it in one bite. Light came out of my eyes and my ears and my nose and my navel and my hands and my feet and then all of my skin turned to pure luminance. I started vibrating, and that started shaking the space ground. The universe was trembling. Some stars fell out of their orbits and plopped into the dark pool at my feet. Then space-time shattered and everything collapsed. The plane at my feet, infinitely far below me, was shallow water with broken stars glowing like drowning lightning bugs. I screamed. A howl of primal rage. Then I cried, sinking to my knees with my face in my hands. I picked up a fragment of a star and held it to my eye. I stuck it in my eye.

Then I could see everything for what it was. I was back in Newark. My flight from AMS was over. The security guards were eyeing me, and my roommate was seething. I didn’t care. My eyes had apprehended the cosmos. I bolted from the waiting room; an Olympic sprinter couldn’t have caught me. I wanted to be alone.

I’m writing this in the notes app on my phone in the EWR terminal-five men’s room, stall four, standing on the toilet. What I saw at the end of my drug-induced revelation wasn’t God, or Aliens, or the Simulators of our reality–I saw myself for what I was: terminally ill. The substances were quite affecting, but the meat of my mental malaise was what I had learned about myself.

This is my official letter of resignation from Princeton University. I am also revoking my citizenship from the United States of America and will not be paying taxes. I hereby cancel my subscriptions, and my library books will not be returned. I name my successor as the executor of my estate. I’ll eke out a meager existence for the rest of my days cowering in the inevitably of my death and wishing I had more time. I wasted my youth when I was young. I’m told I can only expect to live another 60 to 70 years. Death comes to us all.

A Note on Drugs & Discipline from an Overcautious Schoolgirl

Identity and substance use collide during a boarding school drug bust.

By MELANIE GARCIAIremember halting as I started to speak. I was sitting in a circle of friends in the spot we’d claimed on the first floor of our newly renovated school library, which was named after some dead eugenicist’s even deader father. There was irony in this; we were a diverse collection of people. Our freshman year, a white boy in our grade had collectively nicknamed us “The Whole Enchilada,” and admissions photographers loved that they could find Black, Latine, and Asian kids in the same place. We were socioeconomically diverse, too—ranging from wealthy to lower middle class. I was near the bottom of that social ladder, but still, I hoped that my friend group’s diversity had made them open-minded enough to understand what I was

going to say.

The night before, I’d arrived home late from my nightly commute—unlike most of my friends, I was a day student. I swiped through my friends’ private Snapchat stories—which were uncharacteristically busy for a weeknight—and realized that I was missing perhaps the most entertaining event of my junior year. The administration was carrying out a massive drug search of the majority of dorms on campus. In horrified awe, my friends reported the cartoonish lengths that our classmates went to protect themselves—for instance, one kid allegedly threw his vape cartridges out of his bedroom window as a dean walked by. More fascinating was how people covered for each other; day students were instrumental in this. Unlike boarders, who were constantly surveilled by house counselors, day students had the luxury of privacy and mobility. We could simply leave campus of our own accord, while boarders had to obtain faculty permission to leave town. That

night, then, day students hid their illicit substances in their cars, where the administration couldn’t search, or simply strolled out of the library with their pockets weighed down by boarders’ drug paraphernalia.

Despite its scrambling chaos, this camaraderie was tender and inspirational. The way that students looked out for one another was a signal of campus unity that none of us had seen before (especially after the pandemic had scattered us hundreds of miles away from one another for several months…I’ll spare you the details). That day though, students’ collective agreement that banning a kid from their own graduation for owning a vape pen was unfair drove them, in turn, to collective protection.

I admired their selflessness. More than that, I envied their courage, because I was afraid to do as they’d done.

It wasn’t just that I was a student of color (I’m Afro-Latina, so that’s already a racial double whammy) on full financial aid, an intersectional identity that would surely heighten my chances of facing harsh disciplinary action. No, at the core of my fear was the relationship between my hometown and the wealthy, predominantly white suburb that my high school was nestled in.

I grew up in a low-income post-industrial city with a high Latine population. It was

regionally notorious for its drug market and high crime and poverty rates. Our public school system wasn’t strong, so my parents put me in Catholic school through eighth grade. Come eighth grade, I was expected to apply to a local Catholic—or otherwise private— high school in the area, which ultimately led me to an independent secular high school that was far more elite than I could conceptualize.

In my new school, I did anticipate discrimination based on my hometown, especially in relation to drugs. In local media, my city was positioned as the supplier of narcotics to the surrounding suburbs. In local papers, state news, and a speech by then–presidential candidate Donald J. Trump, we were imagined as a cesspool full of immigrants and their criminal offspring that got innocent white kids hooked on heroin. Fortunately, at my high school, sentiments informed by racism, xenophobia, or classism were mostly reduced to the awkward stretch of silence that followed my turn to name my hometown during class introductions. More blatant occasions were rare, like the time my bio classmate winced and said (quite tactfully, I might add) “That’s bad,” when I mentioned where I was from.

Otherwise, I could mostly forget about the stigma that my city carried. There’s an odd numbing effect that boarding school can have.

When your financial aid office

gives you a weekly stipend, a free MacBook, and funding for any supplies you might need; when you, a kid accustomed to a school building with hazardously malfunctional radiators and no gymnasium, are given similar access to the bastion of resources that an elite institution provides your wealthy white classmates; you get lulled by the privilege you gain. Your family may have to save up to take trips to their home country while your classmates can easily hop to Mykonos for spring break, and your middle school may have not have offered algebra while your classmates had already taken trigonometry by eighth grade, but now that you’re all here, the gap between you and most of your peers seems to have shrunken. Extracted from your respective contexts and dumped onto a 250-year-old campus, you seem to forget the differences between yourselves as the Ivory Tower’s cozy, all-inclusive blanket of privilege shelters everyone.

But other days, you get shocked back into reality when you see the staggering balance in your friend’s bank account, or when certain people get tailed by employees at CVS, or when your chem lab partner (who has a lower grade than you) treats you like an idiot. Or when the day students (who are from the aforementioned suburb) feel bold enough to stride out of the library carrying illicit substances or to hide contraband in their cars, while you’re at home, simultaneously admiring their camaraderie and imagining a scenarios that could ruin your life—if your friend’s vape pen fell out of your backpack, for instance, and you were unceremoniously expelled; or if you drove home with your friend’s weed and just so happened to get pulled over by a cop.

I didn’t want to do what a brave person would. But I didn’t want to be a bad friend, either; I didn’t want my friends to believe I’d be there to cover for them when I

was too scared to. So the next day, in the eugenicist’s dad’s library, I explained to my diversity-photograph friend group that I simply had too much to lose. And it wasn’t just me at risk: it was the reputation of the kids from my community who wanted to attend my high school (we were already so scarce in the student body), and that of all the youth in my city. So my friends couldn’t count on me to protect them if another drug search happened. And I didn’t say it aloud, but I hoped it’d be implied: I can’t be labeled another inner city drug trafficker. Ask your rich white friends instead.

Most of my friends understood, or seemed to. Some looked disappointed, but they didn’t question me. But one spoke up with a sad sense of betrayal: “You wouldn’t do it for your friends?”

I didn’t know how to explain it to her. She was wealthy, and she wasn’t an underrepresented minority, so she wouldn’t be criminalized the way I might be. She had so many safety nets that I probably would never have. So I stammered something more about how high the risk was, my community’s reputation, about the threat of the cops. She was a leftist, and this was post-2020, so that was enough to make the conversation fizzle out.

But I still don’t think she understood. If the night before had reminded me of my lack of leeway, that conversation in the library showed me how easily some people overlooked the gaps in privilege that the Ivory Tower’s blanket so often obscured. To this day, I’m itched by a question that my peers didn’t even seem aware of: what sense did it make for me to protect my boarder friends with my privacy and mobility if their relative lack of criminalization, racial privilege, or wealth already protected them? Why would I take on their risk if my consequences were already so much sharper?

Maybe compassion,

selflessness, and courage are supposed to drive me to overcome those fears. Theoretically, I’d agree that we’re all supposed to use our scraps of privilege to aid one another until we make the world just. And I’m sure that there’s plenty of marginalized people out there who are brave enough to take the risks that I didn’t. But, for the sake of my community—and perhaps more than I want to admit, for my own sake—I’m not that brave. You can call me a coward, but if I’d gotten caught on a day like that, I could’ve been called much, much worse.

But other days, Melanie Garcia gets shocked back into reality when she sees the Nassau Weekly.

On Going Off Antidepressants

Notes on the reality of antidepressant dependency and withdrawal

By ANONYMOUS CW: Suicidal IdeationAfter four years of successfully taking antidepressants, this January, I made a mistake. I’d picked them up while I was home for winter break and forgot to bring the new bottle with me when I returned to campus. I would not recommend doing this. I went to the CVS on Nassau Street, and they told me it was too soon to pick up my refill, so my doctor needed to prescribe a “bridge” — which I’ve learned is just a bottle with less pills in it — and then my insurance still wouldn’t cover the cost of the refill unless I waited a month, but obviously I couldn’t wait a month, so, all very messy. It eventually worked out fine, but there were a couple of days where I thought it would not. These days were disturbingly terrifying. I thought about cutting my pills in half to make them last until spring break, or spacing them out every other day — I do miss a dose every once in a while, and it’s not

the end of the world. But, both of these options made me feel quite stressed out. Google will tell you that suddenly stopping antidepressants is potentially life-threatening; for a moment, I felt potentially life-threatened.

I started taking Lexapro and Wellbutrin when I was fifteen. I think there is a larger discussion to be had about the ramifications of putting young teenagers on mind-altering medication, but for me, it turned out to be the right move. Extreme, intolerable lows began to feel a little bit less extreme and intolerable. The part of my brain that was latently planning my suicide gradually just… stopped doing that. I don’t think my emotions have become duller, or suppressed. I still experience a lot of human sadness, and a lot of vivid joy. I cry about things. Sometimes life feels unbearable, it’s just that when it does, I know that I’d still like to live it.

I have no idea how that works, by the way, and I’m not sure how much I can credit it to medication — lots of things have changed about my brain and my body over the last four years. What I do know is that I got better, and I did so while taking these pills. And I’m lucky enough to not experience significant side effects or huge financial costs, so there’s nothing

immediately deterring me from taking this medication forever and ever.

Except this: when the pharmacy — temporarily — wouldn’t give me my medication, I felt weirdly helpless. It became salient to me, in a way it wasn’t before, that I was dependent on this medication, and that if I didn’t get it, I couldn’t trust my own brain to function in the way that I have become accustomed to. There are a whole bunch of disconcerting physical symptoms that can come with antidepressant withdrawal, but the biggest risk is suicidal ideation. I haven’t felt suicidal in a long time. It’s really scary to think that I might just by virtue of forgetting to bring my medication back to campus.

People stop taking antidepressants by tapering their dosage in increments. They often experience some degree of withdrawal, but usually successfully get off the medication and on with their lives. Except, sometimes, they experience a relapse in depression, and start taking medication again. They might try this five or six times over the course of their lives. It might never work.

I can’t speak to what that feels like. I haven’t done it yet. But I think I would feel very defeated. I haven’t spent a lot of time thinking about a future without

antidepressants until recently, but I have spent the last year imagining that I have recovered all on my own, and the antidepressants are just a coincidence. I wouldn’t like to be proved wrong.

I am functioning at a much higher level than I was before. Every year, I seem to have more and more obligations; it is never the right time to risk not being high-functioning. And for all the discomfort I feel at the notion of being dependent on something, antidepressants give me more, not less, control over my own mind. A large part of my concern about taking them for the foreseeable future is probably due to our narrative that being on medication means you have a problem, that effective medicine doesn’t “fix” you because if you were fixed, you wouldn’t need the pills in the first place. No longer being suicidal is only an achievement if it remains true without Wellbutrin and Lexapro.

Rationally, I can look at all of those thoughts and say that they are nonsense. I am very lucky to have found something that works for me, even if it’s somewhat stigmatized. But on a purely emotional level, I do feel a little bit trapped.

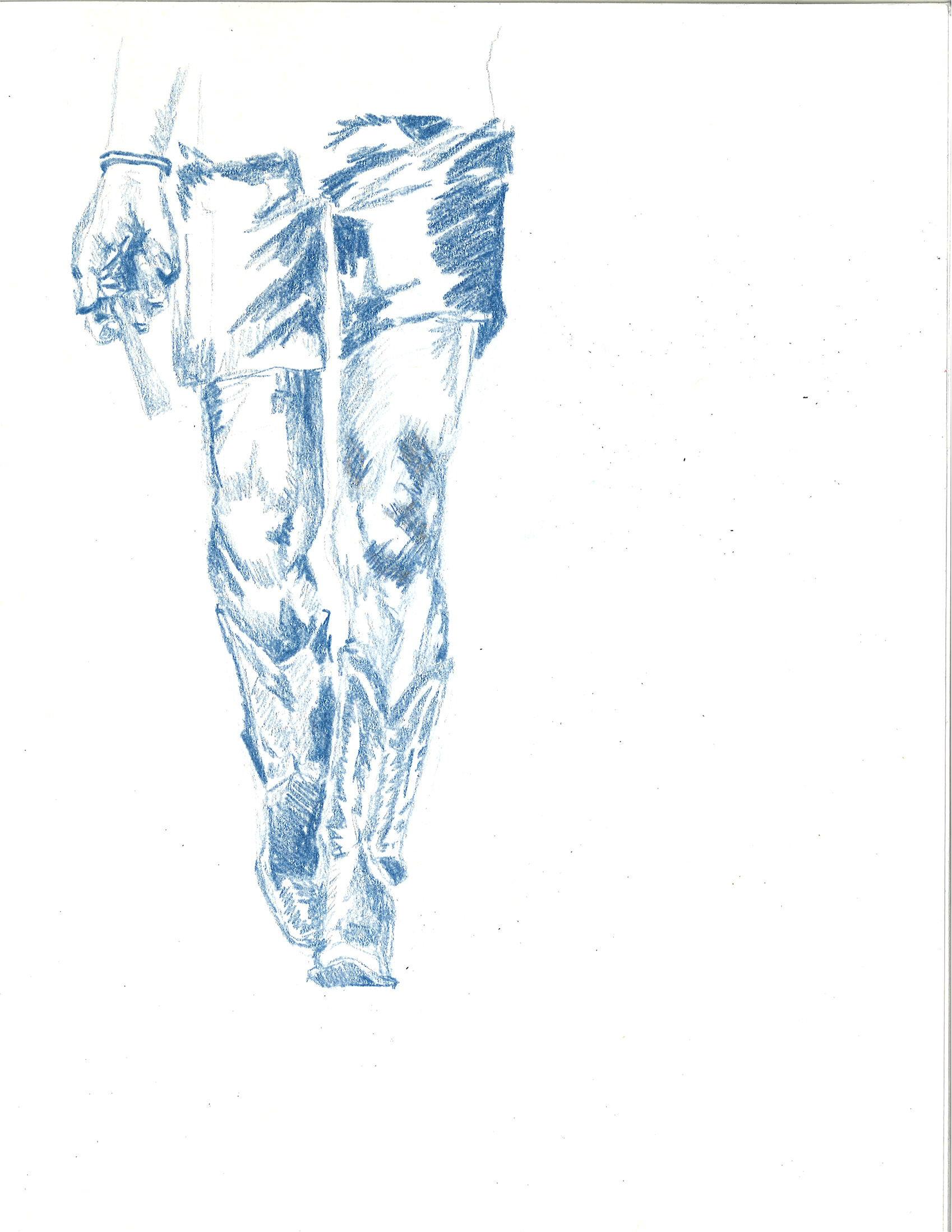

THE MODERN COWBOY’S A GUY WHO SMOKES WEED A Treatise on Chronic Daily Use

A personal history of moderate substance use and abuse

By ANONYMOUS

and found ourselves outside of the home. We ranged with people we loved. Close enough to touch. We cowboyed. When we smoked, I was always someone somewhere, and, really, at the little pressurized, high-heat crystal of the thing, I thought we could do it artfully. The way I saw it, there was something old and dirty and undeniably beautiful to the whole thing.

When I see those friends now, sometimes it feels like we don’t really know what to do with our hands or mouths. Eight of my ten friends smoked every day for years. All of them have tried to quit. For some of them, it worked.

I first tried weed at fifteen, I think, when one of my friends invited me on his family vacation to Hot Springs, VA, which was lovely in the late summer. We wore boxers and slid ourselves into a hot tub that was really only warm. He impressed weed into the bowl so gently with his thumb. He held the little one-hitter hand-pipe so deftly. I was enamored by process.

I spent the night dead-legged by this barometric sensitivity that tried to take every minute fluctuation of how I felt into account. I was jumpy and had no idea what to look for. The hot tub jets bubbled and stopped erratically. I felt pinned to the surface of Virginia. I felt like I made a small entomology of myself against the night. The treeline throbbed with cicada

sounds and frogs. The wind turned the trees. Then, I knew I was high.

Chronic Daily Use Period #2

One summer, I ran a six mile loop in the woods close to every day. I finished dead tired, muddy, and prickling with sweat. Sometimes, I got tacos and a 20oz on the way back to my grandma’s house in Chapel Hill, NC.

Then, every night, I smoked in my grandma’s garden or, sometimes, the guest room, which was Southern and lacey and proper. Two or three times, I smoked with my older cousin behind an elementary school near his house or on the bank of a little backwatered oxbow. My aunt tried several times to smoke with me, but I managed to avoid it.

I liked the garden best. I sat right outside my grandma’s window, but I don’t think she ever suspected anything. It was easy to be ghost-like in these pinelands that slung so low in their valley. It was easy to smoke under my grandma’s window while she lay so still and silent in her bed. Easy is the operative word. Here are all the flowers I could name in her garden: Daisies, petunias, honeysuckle, hydrangea, azaleas, gardenias, coneflowers, milkweed, phlox, and a big magnolia in the front yard.

I am mostly unashamed about my appreciation of these WASPy, dead guys like David Foster Wallace and Dave Berman. These guys who, when I mention that I’m a fan, elicit, not an eye roll or a groan but a more pity-laced “come on, man.” Soon enough though, you’ll find that most of the groaners and eye-rollers haven’t actually done the work of reading or listening or weed-smoking.

I think at least part of my identification derives from their transparency about weed dependency. You can smell it off DFW’s prose. Ken Erdeddy in Infinite Jest not only smokes too much but does it

with stunning expertise. Wallace writes, “he would smoke the whole 200 grams–120 grams cleaned, destemmed–in four days, over an ounce a day, all in tight heavy eco nomical one-hitters off a quality virgin bong, an incredible, insane amount per day.”

Berman, “Random Rules”: “Broken and smokin’ where the infrared deer plunge in the digital snake.” This guy knows what he’s talking about.

In high school, my friends and I used to buy weed from this 26-year-old named Zay, who had a kid and was rumored to have a gun. My gutsiest friend drove Zay to the gas station and waited in the car for him to buy an iced tea and pork rinds. Then, he drove him back to his apartment. Sometimes, we’d get a discount on his shakeand-trim. After we lost contact with Zay, we bought once or twice from a girl in our class, who, at the time, was four months pregnant. We bought from a few members of the varsity lacrosse team. We bought from a friend’s coworker at Trader Joe’s. We bought from a deceptively straight guy. We bought from a deceptively gay guy in the year below us. We bought from a childhood friend. We bought from an art school student. We bought from a guy whose senior superlative was “class medicine man.” We bought from a guy who dropped out and went to wilderness rehab. We bought delta-8 one time from a 7-11 but never did it again. We bought from a friend’s brother. We tried to buy from another friend’s sister. We bought from the first guy we knew to get a med card. Then, one of my friends got a med card. Then, another.

We were stopped by a cop one time while smoking behind a vacant office building, but he let us off, and it was unremarkable.

Before entering a dispensary

license to an associate stationed at the door. Under no circumstances, will they remember your face, even after regular visits. Inside, you have to approach a desk and present your valid drivers’ license to a second associate, who will ask you “medical or recreational,” which doesn’t actually mean anything anymore. They might ask you if you’re a member or want to become a member, and the answer should probably be “no.” You have to wait in a waiting room for a third associate to receive you in the actual dispensary. The second associate at the desk has to buzz you in.

Every dispensary looks the same. I’ve heard friends compare the interior to a yoga studio but also an Apple store or a third-wave coffee shop. It feels corporately hostile. It feels far–geographically–from Zay’s apartment and the faint, spectral sounds of his infant child through the wall.

There are still some permit-related weirdnesses at the dispensary. If you pay with debit, it shows up as a cash withdrawal with a heavier than anticipated ATM fee. Before you complete the transaction, you have to present your valid drivers’ license to this third associate, who always looks at it for a little too long.

Chronic Daily Use #1

One winter, we smoked on a nightly basis, tight in our winter coats, in sun-faded lawn-chairs on my friend’s porch, in the great

nings. We listened to Joni Mitchell and Vashti Bunyan and the wind tearing around slats of the porch. The blue-blackness just out of reach of the light from inside seemed to seethe with grainy substance, as if we looked at it through an old camera. The night so full of noisy, radiating stuff.

I have very few recollections of any that happened those nights.

I was dating this girl and was horribly unhappy about the whole thing. My dog was dying, I think. My brother wasn’t talking to me. I don’t know. It was like I was never really there.

Flower so heavy with terpenes that it leaves residues you can’t clean from your fingers for days.

Flower that boasts THC content as incredible and insane as 35%.

Flower that might better resemble the stuff my parents smoked interminably deep into the past. That flower dry and shrunken. Flower, when I got to school, with names like The Michelle Obama Pack. Flower cut with rosebuds or lavender or mugwort herbal blends. Carts flavored like Black Cherry Fruit Punch. Carts that get hot in your hand and threaten detonation. Carts that survive far longer than expected and become burnt and almost undead. Flower scraped together like gleaners. Flower that comes in a wrinkled ziploc bag. Flower that comes in vacuum-sealed packaging.

Flower that smells predictably,

unforgettably like cat piss. Flower that smells like nothing at all. Maybe you’ve gotten used to it.

You can read these sections in any order, and when you finish, you can read them again if you want, but I wouldn’t recommend it. All you can do with these sections and the small space between them is try to trace lines in the fabric of my relationship to a substance. From there, you can start to trace the lines of my friends, but you don’t actually know them.

You can make like a cowboy out here. You can wander across these plateaux of intensities. You can be in a body and be in a place. The whole thing is very easy.

My baby-brother turned seventeen the other week.

When I smoke too much for too long, I feel scrapped out and insubstantial and sort of translucent. In the end, it’s just weed.

The PuffCo Peak Vaporizer works by heating a copper coil around this amberish wax concentrate of THC, CBD, and terpenes. The vapor percolates through a chamber of water, and–here’s the really magical part–you can activate the rig through an app on your phone. You can use the PuffCo Connect app to turn the thing on, and you don’t even have to be in the same room, from what I understand.

I heard one story from an ex-girlfriend’s roommate. A guy she knew had this PuffCo Peak Vaporizer and the app and used it. Just a really great smoking experience all around, great enough, he said, to be worth the admittedly colossal price tag. The only problem was that one time, as a result of some software issue, from time to time the vaporizer came to life all on its own. This guy walked into the room and found the vapor already percolating, the chamber already filling with the thick, impenetrable stuff.

In the summers, we returned to that porch, and, when he was in town, we smoked with my friend’s older brother. He lived in New York, then DC, then the Bay, but we could generally rely on seeing him every few months.

He overdosed this past summer, but last time, the evening light felt watery. We toked from a dusty bong, and from time to time, resin caught the bowl in the down-stem. My friend’s brother told me about his job, which sounded boring, but, for a job, it didn’t sound so bad. Behind us, the sun set without us noticing.

In a bookstore one time, I met a woman who had met a guy who had sold Animal Collective weed in high school. They’re another “come on, man” artist, but I can sympathize with a real particularity because they’re from where I’m from. We know the same lovely, desolate landscape. I can listen to their music and know that I am one person in this long, brotherly continuum of smoking at the reservoir, in the parking lot of the Jesuit school, the fairgrounds, the field where electrical pylons stagger like wayward giants moving West.

One time, I picked this girl up in the battered four-door that my brother and I shared, and I smoked her out on the shore of the reservoir. I told a bad joke, and she didn’t find it funny. When we hooked up in the backseat, I was too high to get it up, and so we just sat there and sweated. We listened to country music from the fourdoor’s tinny speakers, and the summer made noise outside. We breathed very carefully and waited on something.

The way they saw it, there was something old and dirty and undeniably beautiful to the Nassau Weekly.

Imy drugs

n a ‘very special issue’ of the Nassau Weekly, we’re attempting to tackle one of the most controversial topics in recent history: drugs. Are we the first publication to do this? No. Will we be the last? I mean, I’d be surprised to see anyone else approach the taboo with as much tact and grace as we are sure to. As you flip through the pages of the issue, you might find, however, an explicit non-presence of writing about things that are drug-like, but not necessarily drugs in the ‘classical’ sense. Feelings or objects that can elicit some sense of euphoria or high of the utmost potency. I’m here to fill this gap. The entries you will read may shock you, may be completely incomprehensible, but trust me that I say with complete severity that my relationship with the word ‘praxis’ is akin to that which one might have with LSD. I’ve experienced this word tactilely, not only coming to an understanding of the meaning of the word but also of myself. Buying clothes that I don’t like is like heroin: I know it’s bad for me each time I do it but I’m only trying to recreate those first, great highs, or that perfect pair of pants. I crave the notifications I receive daily on my phone, but I have to obfuscate this fact in order to surrender myself to the masses who claim to hate what the iPhone has done to them: I’m a high functioning phone-aholic. So, when you read this list, read it first as a joke. But I urge you to read it a second, even three or four more times, or if you want to dig really deep six, seven, or maybe eight more times. You know what? Nine or ten times might even do the trick. After these ten times, you might have learned something about yourself and your addictions. You might even find that through this practice, you’re addicted to ol’ Ellie Diamond and her little lists. For that, there is no antidote. Just live.

1. vaping as a joke

2. buying clothes that don’t fit

3. adhering to the speaking style of whatever podcast im listening to

4. telling somebody i worked out today

5. checking my email

6. love

7. the albums ray of light and confessions on the dancefloor by madonna

8. delusion

9. laughter

10. employment

11. the cacophony of sights, sounds, and smells one is confronted with on the streets of new york city ~

12. getting 2 likes on a tweet

13. getting 4 likes on an instagram story

14. the word ‘praxis’

15. checking my notifications while my phone is on ‘do not disturb’

16. “your order has been delivered”

17. fabricating

18. waking up with a mysterious bruise

19. the spotlight

20. leaving things strewn about

21. saying “famously” before describing a habit or trait of mine that is not, in fact, widely known

22. the fog

23. shoes

24. having a weird day

25. cocaine

DRUG SMUGGLING

ACROSS

“Seek and ye ___ find”

Symbol on a score

Campus near Beverly Hills Rocks for Jocks, say

Playful growl

“[Achieve] the trance-like blissful state reached when riding the edge of cumming for as long as possible,” per Urban Dictionary

Half of a Wonderland duo

Swedish city

Calypso-influenced genre

Some July births

Wedding-cake features

Oscar-winning actress

Patricia

Shoestring tip

Light-footed

Drag queen’s accessory

___ white dogs (disparaging catch-all category for some Bichon Frises and Cairn Terriers)

Falafel accompaniment, often

Free app annoyances

Balcony climber of Shakespeare

Joke played with some sincerity

Drug Smuggling Simon Marotte

ACROSS

Florist’s containers

Angsty genre

Additionally

Temporarily banish, as a roommate

“Sure, why not!”

Shockingly dangerous animals?

Word before duty or metal

Salacious

Ancient Athens rival

“The Incredibles” designer Mode

Major record label

Place last, say

Pads used for handling hot dishes... or an apt description of 17-, 29-, and 45-Across

Pupil’s spot

Small amount

Burj Khalifa’s city

Like the fact that this clue references itself

“Fancy ___!”

Michelle Robinson’s married name 1.

DOWN

Hardens, as gel

Sell, slangily

En route via ship

Bleaching agent

Punch bowl dipper

Certain New Orleans native

British boys

Palindromic animal

Hauler’s cargo

More repulsive

Legendary jazz bandleader

Like “Infinite Jest” or “War and Peace”

“No ifs, ___ , or buts”

Abundant in foliage

Separate

Wall St. letters

By SIMON MAROTTEImitative

Cry when making a one-handed catch Real pieces of work

Uncle Sam’s headcovering On a tight schedule

Canceled abruptly

Molten pool

Job in a court, for short

Canonized “Mother”

Antiquated

Picture-book character lost in a crowd

Slender Study, with “over”

Jazz singer James

First name of the “Queen of Country”

Hurrily prepare for a final Continent for 64-Across Cry of delight

Continent for