Portfolio

Naomi Ziewe Palmer

‘The world is full of persons, but few of them are human […] Life is always lived in relationship to others.”

Graham Harvey, An Animist Manifesto

Story,

Project production Texts and media

Introduction

Reinhabiting reality

I’m washing my hands and glance in the mirror, but a stranger looks back. A flesh receptacle returning the gaze of… no one, with the simple regard of a cat, a bird, or a fish.

My hair, skin and clothes appear draped over a skeleton as though by chance with the personhood of stone, coolly objective, the commentary of my identity now muted.

An aspect of my usual awareness is gently panicking at the disappearance of my self from this entity - but it’s merely the brain’s automation kicking in; the cerebral equivalent of the fish gasps manufactured by a body in cardiac arrest. My egoic back-up gropes for something familiar from behind my eye sockets, but it's like looking out of the slot of a letterbox.

I return to myself after what can be only a few moments. The two people in that sentence are reunited and the body I had considered my own is personal to me again.

I dry my hands, the sensory detail of the familiar world returning and my chatter of judgments about it too.

What triggered this feeling of removal from myself, a condition that psychiatrists might call depersonalisation? What was it that spontaneously silenced that part of my awareness that I am employing now to write these words? Had my awareness defaulted for an instant to a state before human-specific consciousness, or that sense of self that we believe should occupy our awareness most of the time?

This state of ‘non-self’, referred to in Buddhist philosophy, is considered a desirable one to attain, but without the grounding meditative practices that underpin such a pursuit, spontaneous depersonalisation can feel like one’s identity is, oxymoronically, wholly void.

In Joe Simpson’s autobiographical account of his traumatic experience as a mountaineer in Touching the Void, he describes how he crawled inch-by-inch with severe injury from the depths of a crevasse back to base camp.

‘When the pain throbbed too insistently for sleep, I had lain shivering on the rocky cleft where I had collapsed and stared at the night sky. Shooting stars flared in the myriad bands of stars spread across the night. I watched them flare and die without interest. As the hours passed, the feeling that I would never get up overwhelmed me. I lay unmoving on my back, feeling pinned to rocks, weighed down by a numb weariness and fear until it seemed that the star-spread blackness above me was pushing me relentlessly into the ground. I spent so much of the night wide-eyed, staring at the timeless vista of stars, that time seemed frozen and spoke volumes to me in solitude and loneliness, leaving me with the inescapable thought that I would never move again.’ [p.173, Virago].

Forced into accepting his occupation of a failing body, Simpson’s account elsewhere makes repeated reference to the duality of an observing yet compelling internal voice that is at odds with his suffering egoic identity, while bereft of all other living company - human, animal or plant - in that stark and unyielding place. He describes an experience of complete alienation from the exposed landscape, which only hours before he had sought to conquer. Even the stars - a source of wonder and perhaps comfort to many other humans looking up at the same time as him - are indifferent, oppressive: he has nothing in common with our ancestral commons. Were it not for the ‘automated backup systems’ of his drive to survive against the odds, he may have allowed himself to die. He is both the subject and the object of his experience.

Perhaps there are two aspects to our relationship with the world and two parts to our relationship with ourselves.

Perhaps a state of connection, familiarity and wholeness - even friendliness - is imperative in how we engage with the world beyond ourselves, especially when confronted with the impact of our collective estrangement from the sphere that supports us. But only in practice - the practice of community (as with Simpson, the evident need for human others for survival), of recognition of ourselves in each other and in other-than-human life - can connecting tendrils reach across that void to bring together a sense of wholeness. That unity is essential if we are to remain alive here, or even maintain a desire to remain alive without taking countless fellow beings down with us.

All of which could sound a little like naive meliorism. Of course, we must strike a gentle balance between states. The cool observer doesn’t desire or crave: it just is And that ‘suchness’ described in Buddhist traditions is a state necessary to letting go of the grasping that underpins the desire to attach and to promote the artificial sense of security, which ultimately doesn’t really exist, through toxic craving behaviours like wealth hoarding.

Although UK naturalist Chris Packham is arguably the activist voice that many of us feel we need during these times of alarming climate tipping points and mindboggling biodiversity collapse (the product of that same extractive and hoarding ideology), I do not adhere to his Lovelockian philosophy that ‘nature’ would get on ‘just fine’ in our absence.

For me, communicative engagement of selfhood with the world and the world of self is the process that not only generates the meaning that distinguishes human existence from a world without humans, but in turn creates a world that makes it possible for humans to live here.

This is an ontopoetic read, for sure, but there is plenty of evidence nonetheless that the presence of humans in diverse environments the world over and across time can generate even greater biodiversity and, indeed, beauty and abundance through our stewardship and harmonious connection with land. The narrative of our absence facilitating the flourishing of life is one that almost guarantees our demise - and possibly the demise of so much more.

Without a vision of our place in the world for ourselves as human beings, we cannot expect to make our contribution to what Australian indigenous scholar Tyson Yunkaporta refers to as the "1,000-year clean-up" or, for that matter, the more beautiful world that part of us knows is within our gift, being within ourselves as aspects of that same world. Can we not accept our place as part of the global organism that is here?

My project emerges from that idea that we have a chance to reinhabit the reality that all matter is alive, both in itself or by participation in the world as a hylozoic entity. My project is one of creating intimacy between ourselves as human participants in the organism of the Earth through gentle acts of creation and letting go, while fostering recognition of our belonging and likely transienceirrespective of how meagre or seemingly ineffectual in the ‘face of things’ those gestures are. Because what else is there for us? Only the void.

Story

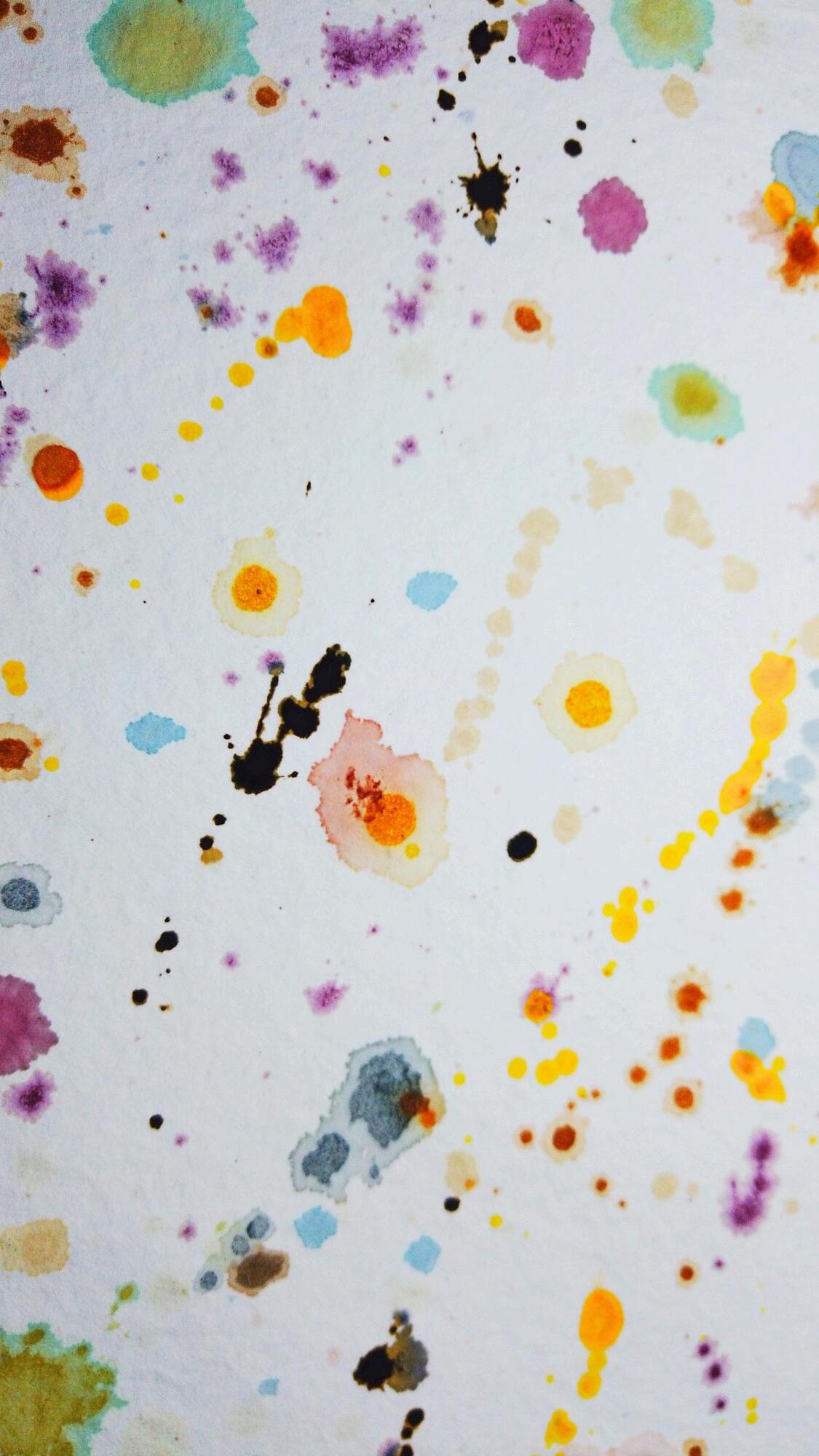

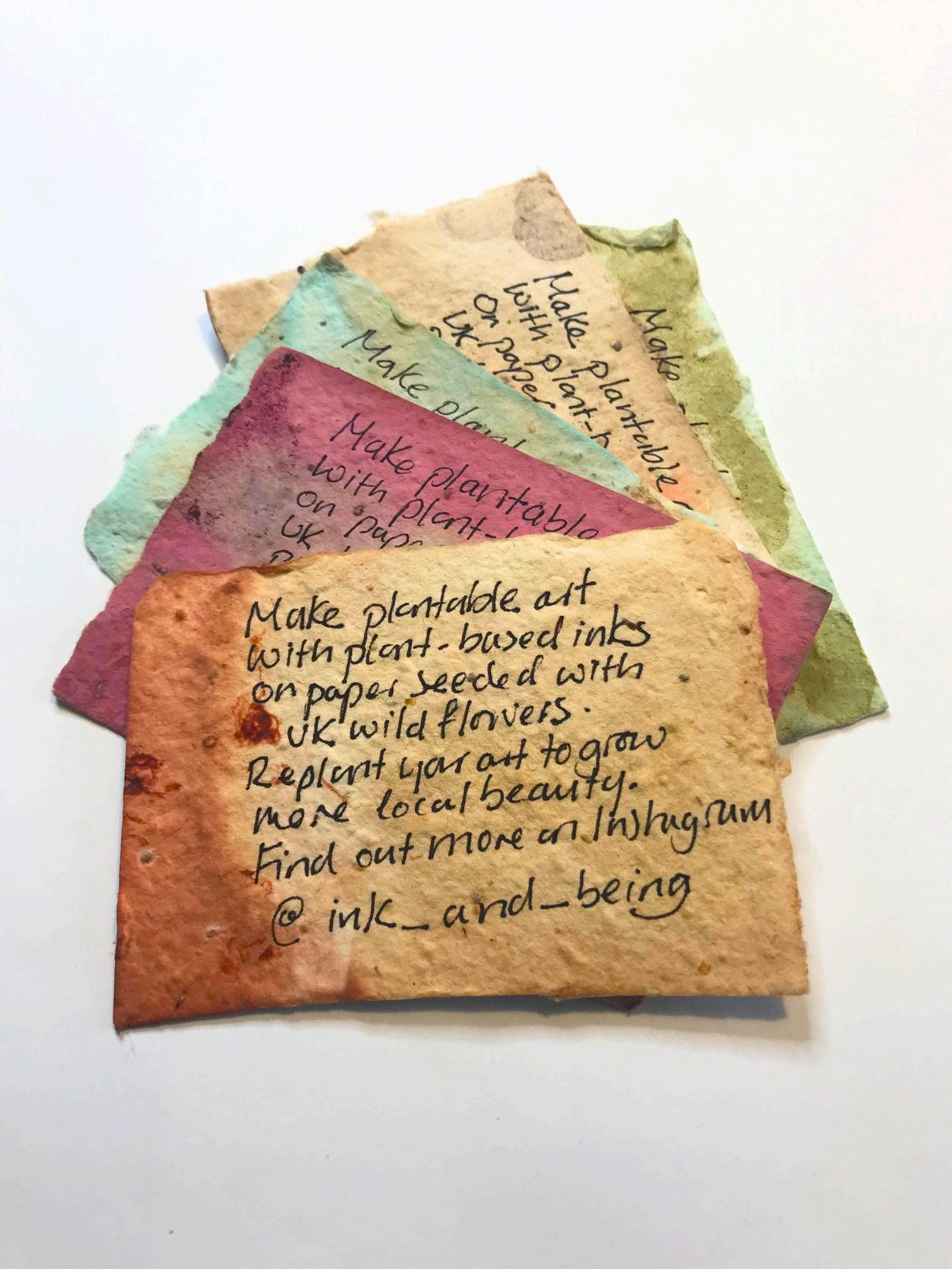

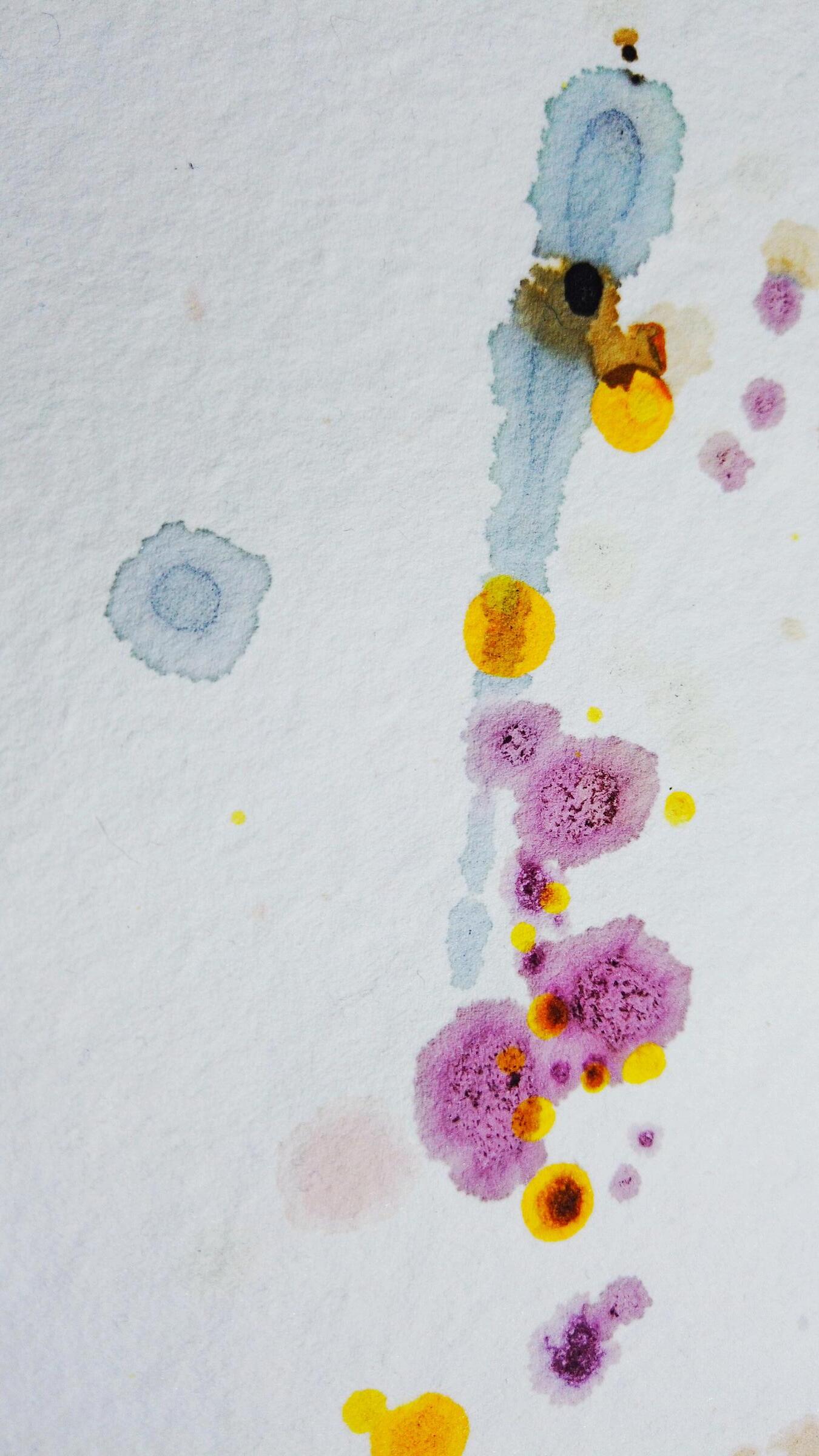

We sit around my kitchen table, which is covered in jam jars of the inks we’ve been making. Among them are little heaps of acorns, chalk, charcoal, turmeric, onion skins, beetroot and berries. We stir our paint brushes in a suite of tones from a strident yellow (‘Stubborn Optimism’) to a deep, sweet purple (‘Pixie Boots’), and swish and drip marks on our paper. Most of us haven’t painted in years, some not since childhood.

We paint on sheets of air-dried recycled paper seeded with native wildflowers, each sheet no bigger than an adult hand. It soaks up the ink readily, so it’s a good thing nature is generous. We have plenty of the blackberries gathered last year, and no-one - animal or human - has any other use for oak galls so I don’t feel too bad that my son has plucked so many ‘fairy footballs’ from one sapling.

As we paint, we chat. The local people who have responded to my invitation to participate in my project are keen to release colour from the kitchen scraps and plants that are growing in the gaps of our fairly stark, newly-built town.

It is mainly women (and one man who came along with his wife) who have responded to the inked invitations I hung on trees, fences and bus stops. Partly this is because the demographic of the new town is weighted towards the young families many of these women juggle; partly, too, because, having drawn on each others’ company and solidarity for most of domestic history, women are, arguably, simply more socialised into responding to the welcome of a stranger. My house is a place likely similar to their own in this production-line town where the houses unfold as though from flat packs and the arable land is gorged upon daily by excavators.

It had been my intention for us to explore the country park together for inkmaking materials and to experiment there, but it has been raining since November, and it’s still unrelenting winter here in Devon. There is no sign the land is becoming less saturated. Soggy benches and sodden turf is unwelcoming to those who will have to pick up the kids soon, or head off to their next shift, or resume that unending caring and household labour in an hour. So here we are, assembled in my kitchen, chatting like old friends although several of us have only just met.

Two women have come from a neighbouring village that is being gobbled up by the new town, the displaced red waters from the naked clay (the top soil having already been plundered and sold by developers) flooding their own kitchens. Though they have lived here for many years, they do not begrudge my presence as a new resident who is, by dint of my residency, partly responsible for the surface water that inundates their lives every year. Well, people have to live somewhere, one of the women says generously, as she whisks her brush in the water. I may move here myself.

Devon is replete with second and third home ownership and, like everywhere, long starved of social housing. The town has been dropped by developers and the district council into the Clyst Valley ('clyst’ meaning ‘clear stream’), a broad floodplain and former marsh and the only space that was left to build upon. Here, substantial ground works have established soakaways for the torrent the tiny brook becomes after a day or two of solid rain. At such increasingly frequent times, the sports field becomes a lake and the drains become fountains. Sometimes surface water ends up in people’s homes when the pipes are overwhelmed or a fat berg has built up. We have yet to see what the outcome of more than a short period of torrential downpour looks like, but that time can’t be far off.

The town is named after the brook that flows through it, the only tribute to the land the build now dominates. During dry spells the brook is only a couple of inches deep in places. A local from the nearby village told me he used to swim in it all the way from Broadclyst village to Rockbeare - about four miles as the crow flies. Here he would catch fish near the manor, with consent, he added. But today, without her natural curves and wiggles, the brook is a lifeless drain for agricultural run-off where you might catch a fleshy dog poo bag or your foot on some glass. Now and again there is a local effort to unplug the stream of the tyres and debris that accumulates, but it feels otherwise neglected. Perhaps a concerted downpour will one day release its suppressed fury. One doubts whether the spirit of the stream was offered the appropriate libations at the town’s inception.

Devon is a county with an entire era named after its geology. When walking the coastal path and feeling lulled by the gentle pace, the seabirds and the waves, it’s easy to forget that it was violent forces that created the undulating strata. Though the flat, farm-flocked valley where this new town is built feels gentle, water shaped it and it feels inevitable that its laws will catch up with us again.

When humans discovered pigment we left our signatures on our skin and in spaces that were made sacred. From red ochre to charcoal and chalk, colour and texture became a means by which to express ourselves in deep relation to these gifts from the ground. Making marks is our heritage, and we have felt separated from the local land that has lent us these materials by the demands of the everyday. But, like the brook, that urge to reconnect with the land is only dormant.

l have a research question in mind for my guests, but it is secondary to what is already occurring quite naturally between us around the table. As we commune with the materials, the paper, the pens, the inks and with each other, I learn about individual losses, a bereavement, a coma, a move, a separation. I hear about childhoods, travels, wishes and reflections, all with little prompting, because it’s not really me to whom my new guests are talking as they permit themselves the time and space to unfold into an activity that allows a brief reprieve from the demands of the head and the burdens on the heart to sink into the senses for a little while.

Mine is not a formal study, and is therefore unburdened by such constraints thereof. Participants have self-selected and are already primed by the nature of the activity, so the project has attracted those with a propensity towards creating; but it is not only those with a desire to make art who have responded to my invitation.

A woman with a scientific background, a senior transport planner, joins me at the table, eager to explore the vivid red alchemy that occurs when you drop alcoholbased turmeric ink onto the pink of an avocado pit, or the audacious green released when a pinch of washing powder activates the juice of a red cabbage. A parent who homeschools eagerly gathers knowledge to share in a future science activity with her kids. A youth club leader is making plans about what to do next with her young people.

All that’s needed for these people to engage with this familiar living space differently is the anticipation of colour, and recognition that it exists in multiplicities even in these couple of square miles of beige pop-up homesunderfoot, overhead, and in their food waste caddies.

The project story continues after a poem and commentary.

Matter in a new build

A midweek morning, the dull rumble of construction. The cat drills and pads on my stomach, I nudge her off so I can wash the dishes. Good morning pots, good morning pans (Jung must have irritated his cook).

The podcast is about Einstein’s manifesto to his first wife. I greet the subatomic particles in the plug scraps, The bowls spooning in the dish rack, The cress sprouting in a black plastic pot on the sill, And my heart beats with gentle joy. Brother Cup, Sister Spoon. Then my stomach heaves.

I rest my hand

Where a tiny life might be.

Commentary: Matter in a new build

I am interested in how concepts of the universal intersect with the motions of the everyday.

References to Jung, Einstein and St Francis of Assisi aren’t made here out of a desire to sound elevated, rather to juxtapose the spaces where life ‘happens’ at different scales.

The scale of the ‘universal’, whether that relates to concepts around Jung's collective consciousness, Einstein's physics, or St Francis' spiritual kinship between material matter and the heavens, are well documented and embraced. But the relationship of these ideas in the context of women, in the domestic space specifically, is only partially examined in art, and typically negatively with regards to our relationship with the latter.

Einstein’s cold misogyny towards his first wife in his litany of requirements of her to facilitate his work is at odds with the popularised iconic and playful imagery of him. Jung famously compelled his cook to greet the kitchen utensils, because they too were aspects of the uni-mind, though likely he was little concerned with her daily mundane (in the original sense of the word) management of them in service to him and his work.

There is a gentle irreverence in the voice in referencing the ‘subatomic’ in the plug scraps, and ‘Brother Cup, Sister Spoon’ in the dish rack (a lighthearted play on the title of the 1970s biopic of St Francis, Brother Sun, Sister Moon, the title of which references St Francis’ kinship with all bodies), but there is sincerity, too.

Over a few moments at the kitchen sink, the voice exists in felt harmony with the universal kinship perspective, perhaps because of the unconscious awareness of new life developing, hinted at by the construction going on outside, the clairsentience of the cat, the emergence of the cress seeds on the windowsill, and the otherwise unaccountable ‘gentle joy’ against the backdrop of washing up and distasteful waste matter that could equally be the source of the stomach heave. The setting of a ‘new build’ with its swift growth seems a symbolically appropriate one in which such a recognition could occur.

The domestic space has so often been assigned to women, and the associated banality of the household is frequently captured in art to articulate a sense of women’s despair and longing to access the psychological, scientific and spiritual territory historically occupied by great men, many of whom were enabled by a hidden workforce of women. But it’s seldom considered that the application of such study can be discovered, observed, explored and experienced in the minutiae of the ordinary; after all, it is often the most extraordinary experience, of harbouring new life, that is encountered in a household setting, here while undertaking domestic work.

This poem bears little relationship to O’Hara’s stimulus text, The Day Lady Died; the response is no elegy, but quite the opposite. Its parallel comes only in the listing of the everyday moments, albeit wearily in the voice of the former, with the juncture occurring towards the end, here as warm surprise, rather than O'Hara's cold shock.

Unlike the free structure of O’Hara’s elegy, the poem found its way through editing into fourteen lines, perhaps signifying the boundaries of the domestic space, or perhaps it is appropriate that the form should be a ‘little song’, given the sense of emerging joyful awareness of new life felt by the poetic voice within that space.

Although this poem leans on the moment of discovery of possible conception, it could end without the couplet, to be further distilled into haiku - a form traditionally evolved to express the relationship between the concrete and the abstract, the mundane and the sublime.

In relation to the Anthropocene, perhaps, were we to foster a sense of the sacred in our experience of the ordinary and everyday, then we might place far greater value on the materials that constitute the fabric of the planet, becoming less squanderous of them, and therefore capable of retaining our place in it as true materialists with a profound respect for matter.

Project story continued…

Neoliberal ideology has almost entirely scoured art from the curriculum. Grey academy chain corridors sport the slogans deemed appropriate for competing, alongside the logos of corporate partnerships. Messages of aspiration and attainment, ‘‘KEEP LEARNING, GROWING AND IMPROVING!’ - the academic equivalent of the ‘Live! Laugh! Love!’ wall art dogma - replace cheerful paintings on art room walls. They might as well say: Make a second income! Set up a side hustle! Monetise your gifts! Kids learn early that there is no place for creating in a culture that does not value anything other than that which can be appropriated by the ideology of wealth creation.

Creative extraction from humans is no different from the extractivism that shreds ocean floors, obliterates land and rips up ancient forests. So many of us are the product of swathe upon swathe of colonising forces; our own doorstep was the first land we plundered and then, as the inheritors of that traumatised psyche, we went on to do the same with the rest of the world. This new town might be considered an idyll to many and yet it is part of a broad and biodiversity-bereft agricultural industrial estate. In this setting, many of us yearn for an undoing: for a woodland where you can't see the edges from the middle; for a forest that isn't rows of listless commercial pine monoculture; for a meadow to nap in rather than a scrap of grass assigned to the muddy margin; for the glimpse of the flip of a fish in the waterways. We long to hear birdsong, not the roar of the adjacent airport and not the incessant mournful bellows from the nearby dairy farm of mothers who have once more had their calves taken from them. This new town has no monument, no centre, no soul, and yet it is a monument to our times, to the privileging of cars on roads that kids can't cross, to keeping us off the land and safely indoors, away from each other.

If we are to sustain our place in the world, then to extract from that which is freely given is counter to any desire to create. Responsible foraging is about not taking more than is reasonable for one’s needs, or to the detriment of the other creatures that depend on that plant, tree or habitat.

I was walking the south west coast path in the spring along some wooded undercliff, which was full of white stars of wild garlic. Partway into that wood, several people were stuffing armfuls of the plant into carrier bags, clearly to sell on in ‘locally foraged wild garlic pesto’ or some equivalent artisan product. It is one thing to make a jar of pesto for one’s own enjoyment, but to sweep the whole lot is a violence. As a solo woman I didn’t want to get into a confrontation with the men ravaging the crop, so on I walked, heart sore that this stretch would no longer be enjoyed by others who had anticipated this spring herald, but grieving too for the plant itself.

Back in my town I admired the clusters of cheerful dandelions that had emerged for the first time that year, apparently overnight, making golden the verges and pathways. They were beheaded the next day. Contractors trimmed the grass golfcourse short out of some obsessive demand for order that deprived the pollinators, whose homes the town had already displaced, of their first food of the season.

Of course contractors are going to fleece the place of its topsoil and its bloomsas often as they can, too. Under capitalism, the destitution of living things is the cost of living. But when we execute that brutal will over a shared living space, we kill a little of ourselves too. We become less beautiful and more lonely. The imposition of order onto our shared spaces is an expression of our desire to externalise our internal chaos, and an act of self-harm.

The project story continues after a poem and commentary.

Four haiku

The bowls spooning, The cress sprouting, Gently joyful.

Spider on my sleeve, Navigating fibres, Dismissed with one blow.

Tiny pumpkin In a child’s hand: Miniature sweetness!

Rain falling, Purple sky. Washing hanging.

Commentary: Four haiku

In these four haiku I have sought to capture fleeting moments of presence in the everyday in recognition of the 'sacredness' in the material, the botanical, the animal, the elemental and the human aspects of our world.

Latinate in its origins, sacredness is a word associated first with religion. Under neoliberal capitalism, it is the acquisition and hoarding of wealth that is sacrosanct. The followers of this religion, the Rational Man (Kate Raworth's homo economicus) makes irrational decisions to perpetuate the credo of economic growth at the cost of all else. And when everything is up for grabs to the first to colonise it, we might ask, 'Is nothing sacred?'

I make no apology, therefore, for using a word like sacredness, because its very absence from our lexicon is revealing. But perhaps the proto Germanic word 'holy' - with its origins in the adjective hailagaz (hailaz - whole) in the sense of 'uninjured', 'sound', 'healthy', 'entire' and 'complete' - is a better fit to illustrate the contrastive reality of how the world has been carved up through the movement of global capital and the urgency with which we must make the world and all its ruptured systems whole again.

The haiku form has traditionally sought to capture the 'suchness' of the moment as felt by the observer, the moment of loss of awareness of one's self and one's burdens - muga: an instance of experiencing unity with the world. Unity - or wholeness. Holiness.

It felt appropriate that these moments of wholeness should be humble and everyday, domestic, and routine. Because if value can be discovered in every instant, then the craving and reaching for more beyond that moment can diminish as the awareness of 'self', of individualism, of pursuits, distractions and demands, can - for a few moments - gently retreat into an instance of completeness and presence.

And, with its tools of distraction, escapism and manufacturing of desire, capitalism insists upon the urgent and constant privileging of selfhood, of attainment, of hyper-individualism. Contentment in the present moment is the enemy of capitalism, therefore, being present is a radical act.

It felt necessary and inevitable that the four haiku should originate where I live. I work full time from home where I am raising a young family. As with a great many people, the household space is where I spend the greater part of my time.

Those with access to regular fresh sensory experiences - in travel, adventure - may well be addicted to that moment of total presence that arrives when one is startled into a state of awareness by the thrill of the new.

This type of presence-seeking is favoured by capitalism because such moments are often available only to those with the time and resource to pursue them. The acquisition of many such moments amounts to an aspirational lifestyle.

Leaving aside my own envy as someone who would quite like to do a little more exploring, it nevertheless feels like a radical act to capture a fleeting moment of awareness that is, in fact, available at any time without the need to strain planetary boundaries. The haiku is the right vehicle for this defiance.

My guest today is testing the depth of colour of a rich beetroot ink. She is a former ranger of the local parkland and her failing health obliged her to leave her post. She spoke about having grown up rurally with a feeling of friendship with the little white flowers she called milkmaids, with the bluebells and primroses. It’s inherent in me to love that, because I grew up like that.

Our town is among the youngest in the UK, with a population that includes a great many children. But the parkland is almost empty as the young people have remained indoors since Covid, and when they do go out, curtain-twitching nimbys deem them a nuisance for the crime of listening to music and reprimand their parents on the local Facebook page. The Neighbourhood Watch group recruits 80 participants within 45 minutes of launch, while upstream, the community association is struggling with the same three or four people trying to get things off the ground. In a new Facebook post, an incandescent minimum wage staff member, protective of the company’s multi-million pound profits, reports that a couple of kids pinched some sweets from the shop and demands local policing. Elsewhere, a bus stop pane is smashed and the calls for policing are amplified. That demand is responded to with swift efficiency and satisfaction by the town council.

If children in this new town are already being told they don’t belong here, if the animals and plants whose place we have made our own are being deleted from it, we might wonder how our kids can be expected to love it.

Part of this project is about stitching together a relationship between the inhabitants of the new town and the land that lies beneath. Even with the fervent mowing, the ill-timed hedge cutting, and the herbicides sprayed on the camomile that has the temerity to poke through the pavement and on the moss that grapples for a place in roadside gutters (‘the stream is already dead’, reads the town council minutes as it approved the continued use of weedkiller), the morethan-human world is still offering us space alongside it.

It doesn’t take much for the land to forgive us the imposition. It is always ready to welcome us, the miscreant sibling, back home. The land proves time and time again that with even a modicum of our caretaking and participation, it is willing to allow itself to become more diverse and more bountiful in response.

Which is partly why the participants in this project have agreed not to keep the art they make.

The project story continues after a poem and commentary.

Felled

Lost in space with Mars the only out for a few billionaires who couldn’t survive the ocean, with no escape from daily detentions, uniform penalties, skipped meals, rising seas, scorched earth, sinking boats with babies on board, traipsing through a place that hates you and will charge you your life for the fraction of the space you need to breathe; a litany of post-crash cashless, digital land grabs, stabbed in the chest by the mess of a world that already ended. So bring it on - don’t mess around.

He cuts down the tree on a wild night when the wind's howl meets his own.

That tree, so seen, is no gift to him, so he, unwitnessed, cuts heaven from earth, bringing the years crashing down. A mean feat: three centuries stolen by sixteen years in seconds.

That gap, agape, aghast, empty air, a void that opened when he, still green, was toppled.

It's only a tree. What about me?

Stunted, he steals the joy he can't grasp to fill that gap and makes it gape.

Rootless, he gouges his hollow mark on a landmark, marked on maps, in story, in song, now marked by grief and rage.

We will replant green monuments, and make art in memory of a time long lost that can’t be reached by a generation of minds left to feed on the algorithms that fell a forest every day.

They call for him to rot but in or out he’s already jailed in a place that severed his link to land, to home, to a space where he can rise rooted and taste the earth and drink the rain. But when the teeth of his saw bit the trunk of that tree, there was a moment - of family.

Commentary: Felled

This free-verse poem relates specifically to the felling of a three-hundred year-old sycamore tree made famous by its place by Hadrian’s Wall and in popular culture. At the time of writing it was believed that a sixteen year-old boy* had cut it down.

Once I had integrated my broadly-shared feeling of distress and anger at the mindless act of apparent hatred of nature, a very obvious microcosm of human carelessness unfolding at a global scale, I felt curiosity about the origins of the desire to destroy something that occupied such a place in the shared psyche, and was perhaps destroyed for that reason.

The poem is a ‘villain’ origin story, with a voice not unsympathetic to the perpetrator. It asks what conditions enabled an act so wanton, allowing space for the villain’s voice to emerge at times: ‘What about me?’.

The poem challenges the cognitive dissonance we apply when we are roused to strong feeling in relation to the loss of a single tree to which we feel connected, while we maintain indifference to the ‘forest felled every day’ as a product of our consumer choices, with Amazon being one such ironically-named enabler of broad-scale ostensibly ‘legitimate’, yet objectively criminal, acts.

The associations with the stimulus poem, Ginsburg’s Howl, alluded to in the second paragraph, are in the pacing of the asyndetic listing of societal failures that contrast the rich and powerful with the poor and marginalised in the opening lines, illustrating a society in decline and a world in collapse, with many of these features specific to the experience of an estranged young person.

Here the free indirect voice of the boy emerges: ‘Bring it on, don’t mess around’. To him, the world is already at an end, so what difference does the felling of one tree make? The boy’s isolation, lack of future, and the hostility and disregard he feels from a dominant culture that does not allow him equivalent space to live and thrive, brings to mind the aphorism of burning the village down to feel its warmth.

The poem invites us to engage with the possibility that at the moment of the tree’s felling there exists a kinship between the boy and the tree, because they both face imminent destruction, albeit a singular act of arson contrasted with the harmed product of our structures and systems - both are among many casualties.

The boy never had the chance to grow like the tree: to ‘rise rooted and taste the earth and drink the rain’. He signifies our own collective estrangement and we abject him for this.

This boy does not seek to steal joy from others; he seeks to steal joy he did not receive. The tragedy is that he will never experience nourishment, since he has already been felled while young - ‘still green’. As a people that struggles - or refuses - to recognise our alienation from the Earth, it's easier to cast him simply as a crook.

This reading of an incident that elicited national outrage could easily be perceived as handwringing middle-class angst at the suffering of the likely working class poor, but the relationship between the isolated tree and the isolated boy is not incidental. Without a sense of interconnection, neither can survive, and it is this loss of a sense of connectedness with our place in the non-human world that arguably has given rise to the Anthropocene. The boy’s story is our own.

Project story continued…

We have been cultured into hoarding. The relatively recent personal storage unit industry is still thriving, TV schedules are back-to-back decluttering shows, and wardrobes are fat with sweatshop garments, their labels still on. All this is the inevitable outcome of a culture built around consumption. We are drowning in the products of capitalism, and like the magician’s apprentice, we haven't learned the magic word for stop. We are hungry when we are time- and space-starved and when our natural tendency to create is thwarted. While we can't fill that void with stuff, we gather more around us.

Lao Tzu said, ‘[… ]the sufficiency that comes from knowing what is enough is an eternal sufficiency.’ We know this; we just need the space to feel it.

Turning the fridge door into the home gallery creates a joyful altar space for celebrating the artworks of a household's young, but the broader cultural approach to art is to collect and to hoard it. Originals hang in safes while copies are displayed. Likewise, minerals and metals are ripped from rocks to be turned into objects of wonder that sit unseen in vaults underground. Hoarding and then hiding, rather than celebrating and sharing the art and craft of human making, is what our elite models. Now the Earth’s material is extracted from the ground to power data servers where unthinkable sums of digital currency is hoarded. Real matter is made fiction, and few question the sanity of this.

The beautiful ink artworks being made by my guests are well worthy of at least a place on the fridge, if not on a mantel. Perhaps they are deserving, even, of a gallery space, but this isn't what they have been made for.

Rather, we are consciously undertaking a practice not only of letting go, but of giving back.

These flower-seeded botanical artworks are to be assembled and temporarily stitched together with burlap to create a composite piece, a patchwork paper quilt that celebrates the time we have spent in their making, gathering around a table for the simple act of play. This composition cannot be anything other than joyful, with the heart that has gone into making each ink together and with each brush stroke and mark full of individuality and collaborative feeling.

Each small panel is unique, a playful investigation into technique and tone. They are masterful in their rawness, pieces of art that are so close to the land they came from, products of the community that has elected to join in its making and in letting it go.

In the summer we, the contributors, will gather at my allotment for the ‘private view’. A gently humourous gallery space that the town council would most certainly put a stop to if they knew about it. But this is a community space, and an appropriate one, because after we have celebrated our work it will be dismantled and then planted.

Each artist will take away their pieces to plant somewhere in the town. Perhaps a derelict scrap of land so far untrod by contractors, perhaps a piece of soil between the astroturfs that are already brittle and bleached. I already know where I will plant it, says one woman, whose exquisite painting would not be out of place hanging in a more prestigious location.

Even before she has finished her painting she is planning its burial; the notion that it will become new life is giving her goose bumps, she says. She has in mind a seemingly unowned foot-wide strip of land next to her house that she has been tending since her arrival, much to her neighbour’s dismay that it shouldn't simply be tarmaced over. Her spirit of ‘in my back yardism’ is a quiet counterbalance to the local furies in the Facebook chat.

Already she is envisaging the cluster of wildflowers it could become. If it makes a difference to one butterfly or one bee then it's worth it, she says, quickly grasping the value of the gift she is planning to give and the circularity of this process of making art that regenerates the soil that it came from - on its own timeline, of course: wildflowers are notoriously selective about picking the right moment to put in an appearance. And patience is a part of this project, too, because the nature of the art means that there is no completion date. The second, third or fourth viewing could be years down the line.

The ritual of burial is a sacred one, but not a solemn one. Birth, not life, is the opposite of death. And these burials are about rebirth and renewal. Into the ground goes our artwork, and with that the conversations we have held alongside our making - all the nuanced aspects of our complex lives, individual and shared histories, all of our wishes for the future - take root.

Each artwork burial is a fresh patch on the fabric of where we live and a gesture of reconciliation.

The woman whose home the building of my home has flooded gives me a warm hug as she leaves, easily surrendering her painting to my care. She expresses a wish to pay me. It’s part of the gift economy, I reply. But I am hopeful that she will pay the experience forward by sharing this sense of communion with those gifts from the local land with her youth group, enabling them to see where they live afresh and full of colour, the potential of which can be realised before being offered back to the soil, perhaps in an act of ceremony or gratitude for that brief reunion.

Later I receive a message from her to say that she has found a cluster of oak galls close to her house. Soon her youth group will pluck some of them and begin experimenting with the same rich black ink used by Leonardo Da Vinci.

So what was my research question? The one I asked but perhaps didn’t quite need to? It was, ‘When do we feel at our best as humans beings?’

As with permaculture, the answer is within the question: when we are being.

The legacy of this project is in the process, not in the product - the inverse of the ideology of these times. It is in understanding our unity with the local land with a feeling of friendliness and returning home. When we feel at home, we don't need to assert dominance over it and we no longer experience that sense of a divided self. There is no stranger in the mirror when we feel at home in this entirely closed-loop system of which we are a part; when we return home, we are returning to ourselves.

Critical influences: A place for gentle activism

The origins of this project took root ahead of my application to the New School during lockdown, that interlude that permitted the space for many with the privilege to look again at how life could be. The idea has remained fairly consistent since, but I might not have anticipated the material process, the conversations that took place and the effect of the activity on project participants.

As someone who grew up anxiously absorbed by what was then referred to as ‘global warming’ and the plight of ‘wildlife’, it’s reasonable for me to wonder whether, in middle age, with decades of eco-anxiety under my belt, I needed the course to support my investigation. But the New School has given me a great deal more than awareness of human impact on the world, not least the permission to share and pursue my inquiry, perhaps in a similar way that my project gave permission to my own participants to explore their creativity in turn. The importance of community, whether alongside fellow New School scholars, or with those who joined my inkmaking sessions, was a fundamental driver for me and the philosophical thrust behind my direction.

I have thrice referenced permission. Perhaps as we move further into what feels like these ‘end of days,’ the imperative to assemble for creative and intellectual expansion will become less constrained by the hegemony of ‘legitimate’ context and more imperative to claim as our birthright.

My theme of rediscovering and recognising our creative nature as nature has been shaped and influenced by those whose readings of the world have elicited a sense of recognition in me; voices whose ideas awakened in the context of academia, or were grounded first in the experiential and subsequently examined through study, or came from beyond academia and are very much embedded in land. Of these, those who told the best stories most influenced my own reflections.

To an extent, the context of the course legitimised the possibly awkward first rituals with land that my ink-making participants might have felr when the time came to bury their artworks. But in the absence of land-based rituals of the everyday, feeling ‘awkward’ is a necessary concession to make when arguably normative behaviours have compelled us away from a sense of connection with where we live.

The imposition of the new town upon the place where my investigation happens could be described as a kind of ecotone. I propose that this imposition may yet nurture the potential to become richer than either habitat in isolation, but, as I have sought to convey above, only under the condition that we recognise ourselves as one biological community. After all, the painterly richness of a garden, with its cartoon fruit and vegetables and flowers that bloom like children’s drawings, is less likely to occur in the wilderness without the artistry of a human hand; the food forest of the Amazon and the other remaining biodiversity-rich parts of the planet cared for by indigenous peoples is testimony to that.

At our initial meeting, my project supervisor, Dr Sarah Elisa Kelly, asked me, What is at stake?

I struggled to respond to this question at first, because against the ever-present recognition of - and for the vast majority of humans, experience of - accelerating biodiversity and climate collapse, any gesture I might make feels ineffectual, or worse, indulgent and bourgeois. After all, what could be less urgent than sitting around a kitchen table, painting and chatting?

Following an abbreviated crisis of confidence, I rationalised that even with all the radical action and policy-making in the world by people infinitely braver and more expert than me, emissions are still going up, and target after target is being overtaken by soaring global temperatures while our impact extincts hundreds of species every day.

What if we, as individuals, as members of our local communities, were empowered to recognise ourselves in the global song of these times? Perhaps we might add our subtler notes to create a little harmony (not the shrillness of mindless positivity), rather than add to the prevailing discord with our own despair. And to risk straining an already overburdened metaphor, could that melody catch on, at least locally?

Among many of those who bear witness to the unfolding enviro-political catastrophes playing out (and are not yet impacted like those on the frontline in the global south and those facing poverty in the industrialised north), there is a tendency to seek refuge in the certainty of our decline as a race as we trigger these catastrophic tipping points. There can be a perverse comfort in ‘being right’ and having our worst visions play out. As Rebecca Solnit says:

‘Despair demands less of us, it’s more predictable, and in a sad way safer. Authentic hope requires clarity - seeing the troubles in this world - and imagination, seeing what might lie beyond these situations that are perhaps not inevitable and immutable.’

Clarity, and imagination. As someone who has recklessly/selfishly or helpfully/hopefully brought another human into the world, and rational though it might be, I cannot afford to commit wholly to the logic of collapse. Submitting to and adding to the net anguish is not useful, if nothing else. I have to support myself to see beyond, as Solnit says. All the same, when one looks around at all the people in our lives and considers that most are overwhelmingly pleasant and reasonable, and generally quite helpful, especially, as we saw, during times of acute crisis, such as during peak covid, how is it that it has come to this?

Anyone who has worked under and felt the weight of the systems of neoliberal capitalism will be familiar with the Hanlon’s razor heuristic: never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. Grey’s Law expands that any sufficiently advanced incompetence is indistinguishable from malice.

So is advanced stupidity the explanation for these apparently entropic times?

David Graeber’s and David Wengrow’s anthropological and archaeological investigation into the Dawn of Everything challenges the Hobbesian/Rousseuian binary narrative for a richer context against which to read the emergence of today’s dominant culture. It is a practical episteme and helps to contextualise all of the systems into which the world is now held hostage, and it offers no solution, of course. Theirs is an examination of how things have been, not of how things could be. Yunkaporta, meanwhile, diverts us from linear teleology to assert that the ‘war between good and evil is an imposition of stupidity and simplicity over wisdom and complexity’, a spiral curriculum of ignorance and illumination. It is a war that is also built into story: specifically, ‘right story and wrong story’. While ‘wrong story’ can gain traction swiftly through mis- and disinformation, ‘right story’ has a longer, slower trajectory, emerging as a deeper consensus over time, because the physics of reality (not ‘truth’) is that right story must eventually become evident.

Nevertheless, while we live at a time when the grip of wrong story is playing out as unimaginable suffering (the scale is far beyond the scope of imagination: it is actual), how do we respond to this despair? Dr Robin Wall Kimmerer says:

‘Restoration is a powerful antidote to despair. Restoration offers concrete means by which humans can once again enter into positive, creative relationship with the more-than-human world, meeting responsibilities that are simultaneously material and spiritual. It’s not enough to grieve. It’s not enough to just stop doing bad things.’

By asking the question of my project participants, 'When is it that we feel at our best as humans?', I hoped to create a space for right story to be told from a place of the experiential and restorative practice that Kimmerer describes.

Replies were simple, not simplistic. The wish was for community, not consumption; for relationship with land, not estrangement from it; for individuation, not hyper-individualism; for collaboration, not competition. The precise opposite, in fact, of the ideology compelled upon us by almost every aspect of the current paradigm. Yes, my participants were self-selecting and heavily primed by the context and the nature of the activity, but they were not monks and nuns. Perhaps less receptive ‘others’ entrenched in identities endorsed by establishment values, who then have the chance to experiment with alchemy, texture, marks and colour in a companionable setting, would soon allow a softer awareness to emerge, one that recognises the difference between wisdom and stupidity.

In Kaplan’s and Davidoff’s essay, A Delicate Activism, they discuss the ‘magic’ of the ‘ordinary’ in their approach to the Cape Flats of Cape Town conservation project:

‘The ‘magic’ lay not in method or design, though these support it. The magic lay in the quality of conversation we were able to engage in, and the space we created for it - the magic is ordinary... yet magical as it is so often elusive... relying as it does on quality conversation that asks for a deep level of integrity and trust in relationship that is grown in a myriad of ‘ordinary’ and everyday interactions and activities. The ‘magic’ of this practice is essential if we are going to conserve our ecosystems and our communities anywhere, and its ordinariness means it is transferable….’

Through my haiku and my sonnet, I sought to emphasise the ‘magic’ of matter and the everyday being accessible in the ordinary and in the familiar felt like an important aspect in the phenomenological approach I took (which assumes a yearning for the ‘reciprocal and creative relationship between human beings and the world’ that Kaploff and Davidoff describe). I hoped that whatever emerged from that typical new-build setting would be relevant to anywhere, to anyone and to any time, in ‘order that we may live in our world in ways that enhance and make it fit for living in,’ as the authors of the above study state.

Although between us we did create a beautiful patchwork composite piece of art that was full of colour, a piece that seemed to embody those immediate and intimate conversational moments, the making was a vehicle for achieving that state of companionable presence, simply by focusing on our inks and their influence on those hand-sized pieces of paper, seeded with potential. And it is our potential that we must foster and draw upon.

In 2014, Ursula Le Guin gave a speech at the National Book Awards:

‘I think hard times are coming, when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom. Poets, visionaries - the realists of a larger reality.’

As I have sought to capture in my poems, for me the voices Le Guin anticipates go beyond those of writers, and can be found in anyone who can discover a deeper value ‘in the dew of small things’, to reference Kahil Gibran. And those things might be as small as a literal seed or in the figurative seeds activated during a conversation over a cup of tea at someone’s kitchen table. And while everyone who has ever gone down in history as a great humanitarian or peace activist may well have once had a pivotal conversation with a neighbour over just such a cup of tea, all the multiple micro-kindnesses, gentle acts and generosities might also have achieved far more than it is possible to calculate to temper the harms that a culture steeped in collective historical trauma (as both victims and perpetrators of colonial harms, as indigenous American academic, Dr Lyla June discusses in relation to her fascinating integration of her duel indigenous and European heritage) could unleash.

So what’s the harm in bringing our awareness to these ordinary moments, especially when that awareness is enhanced through acts of shared creativity - a little respite from that prevailing mode of coerced consumption and pursuit of stimulation and attainment and growth?

Though economics and ecology author Charles Eisenstein has fallen foul of much recent strident criticism and has been cancelled by a fair chunk of the political continuum in recent years, partly owing to his insistence on nuance across all manner of divisive topics, and although I would prefer a little more class consciousness and a little less universal consciousness, in many of his ideas I recognise possibility. His discussion in his book Climate, a New Story, presents a vision for a future in which we undertake a regenerative role. I find solace in his proposal that:

‘Whether invisible or not, acts of great faith, acts that come from a stance deep in the territory of reunion, send powerful ripples out through the fabric of causality. One way or another, perhaps via pathways we are unaware of, they surface in the visible world.’

This idea of invisible networks, of hidden magic that holds the fabric of reality together, is one that presents the possibility for a livable future, because it cannot be capitalised upon, though the dominant culture of extractivism tries, with its tentacles probing into human relationships with each other and to the living world, ever seeking to draw wealth, if not value, upwards through those intricate bonds.

Rather, our bearing on reality is complex. We are, as much as anything, part of nature’s complex tapestry; a rich though slim seam in the weave that extends all the way back to the bubbling pools that first wove the strands of the amino acids from which we emerged. And before then, to swirling rocks and gasses compressed by gravity into a sphere, and before then to the universe's opening chord - or cord, if we are to adhere to the textile metaphor, which itself could be just one cloth among possibly infinite weaves. Against this complexity, and to quote Gandalf, even the very wise cannot see all ends.

Now back to the kitchen table. Or the warm data lab.

It’s important to me that this activity is about the ordinary places where many - if not most of us, at least in the UK - live. I am pretty conventional: since I didn’t particularly relate to it, I pragmatically took the honorific ‘Mrs’ in my twenties to make (typically small-c conservative) people in positions of power feel comfortable when interviewing me for jobs. I work in the least harmful paying role I could find, alongside pleasant people in typical spaces at desks and on Zoom, not especially close to the philosophically refined or bohemian, artistic, creative, academic, or pioneering spaces where intellectual inquiry, activism or political dynamism is par for the course. Like a great many people, I chat with my neighbours about bin collections and parking, and to other parents about school pick-ups and drop-offs. I keep on top of the domestic demands, and make daily meals. I have squandered a fair bit of emotional energy diminishing myself for my conventionality and lack of any particular ‘career’ ambition. I have felt frustrated by my aversion to putting myself into a space of attainment, for not having adequately cultivated a USP that my peers who had excelled by the standards of this culture had, for not having travelled widely or cashed in on the many riches available to others who, like me, meet the demographic of those rich in choice. I became politicised late, only when I became a teacher in my twenties and could confront the complexity of the relationship between young lives and systems. Much later still did I begin to grapple with my egoic identity thanks to adversity served by the standard business of being human, and became, therefore, marginally more capable of beginning to let go of these self-imposed constraints and to recognise that it wasn’t my own values with which I was struggling.

Because woven into all of this abundant ‘ordinariness’ available to me, far from war, starvation and persecution, underpinning all this immense good luck, is everyday care: values of intimacy and connection, of listening and participation that some of us are lucky enough to be born into and many of us share in our seemingly inconsequential exchanges. And it is in these spaces that conversations about how reality is playing out occurs and what our role is in shaping that realityaway from the influence of violent ideological forces, apart from the dominance of debate deemed legitimate in our institutions and across our media, and foremost in the immediate, in our consensus reality of human-to-human, over garden fences and cups of tea. In these spaces the simple Hobbit-like power of the ordinary holds, as gently trickling tributaries, influencing the harmony of our everyday and shaping the bigger picture.

Kimmerer asks how, steeped in modernity’s discord and abjection from a state of felt connection, can we ‘find our way to understand the world as a gift again, to make our relations with the world sacred again?’

I have tried to respond to this question through the relational nature of this project and the associated poetry, because as Kimmerer goes on to say, by paying attention we create, ‘[...] a form of reciprocity with the living world, receiving the gifts with open eyes and open heart.’ And to me that living world includes the people in it, in our micro-exchanges, in our regular acts of sharing.

But are all these micro-exchanges enough to withstand our self-determined demise? Bringing the light of awareness to the everyday might not be enough to hold back the floods, quench the fires, restore the failed crops or end the wars, but all the same, can we at least become better companions to ourselves and therefore to each other? It’s hard to imagine that such kinship can be expanded during a time of such monumental human violence. But, as Solnit says, ‘The future is dark, with a darkness as much of the womb as the grave.’ And, like the womb, the soil in which we bury our seeded art is dark. And that darkness likewise supplies the incubation of a seed, or an idea, that is compelled to make its way into the visible light when conditions allow. So surely we should be ready to help support the conditions of unfolding, wherever we are, especially in the most ordinary of settings?

A practical criticism that might be directed at this project is that plants don’t need our help to thrive. After all, don’t brambles, dandelions, buddleia and ash saplings successfully self-seed without our intervention? Left to it, as evidenced by photographers like Gerd Ludwig who documented the Chernobyl nuclear disaster over three decades, surely ‘nature’ could take hold and recover easily enough without us getting in the way? Such photographs of Chernobyl’s rewilding are testimony to the incredible self-healing powers of the Earth, which is inclined to repair its skin fairly rapidly following man-made disasters.

But in the near term, without our total absence from the planet, we often live inside the wounds we have inflicted and suffer those wounds ourselves. Railway sidings smothered in brambles exhibit for thousands of miles what becomes of land that has been interrupted by the scars of our traversing it. Brambles flourish due to excessive nitrogen levels in the acidified soil brought about through industrial agriculture. Of course brambles have their place as the nursery of the oak and as structural protection for some species, but the lack of biodiversity is a product of our broader influence.

It’s easy to feel cynical about the word ‘stewardship’ when alienation from land ensures that thousands of trees that are planted by greenwashing brands as vanity or carbon offsetting projects (often to legitimise destruction elsewhere), and with a plantation rather than a regeneration mindset, result in the deaths of those saplings due to lack of investment in their continued care. This doubles the cost given the water use that went into first establishing those plants. Simplistic solutions to complex problems without deeper relation to land and the slow, considered work required of a caretaker demonstrably creates more problems.

Which is why the planting aspect of this project is secondary - maybe tertiary - to the act of engaging in ceremony with place and with communion with each other.

Masanobu Fukuoka, in his founding document of the alternative food movement, The One-Straw Revolution, says:

‘I believe that if one fathoms deeply one’s own neighbourhood and the everyday world in which he lives, the greatest of worlds will be revealed.’

There is much reassurance and enormous possibility in this entirely countercultural belief, especially when in the dominant culture the emphasis is placed on the importance of making outstanding gestures, leaving a monumental legacy, and making a headline-worthy impact, of being extraordinary rather than extraordinary - very often at hidden personal, societal or environmental cost. But if the future is determined by the most compelling story, then surely we must play our part in shaping it from wherever we are with whatever is within our gift. In a society that assumes giving means depleting and is driven to ever greater harms by notions of scarcity, actual giving comes at no cost because the reward is built into the act, which is almost a principle of permaculture.

A fundamental permaculture principle is that the solution exists within the problem. For example, if a garden is dominated by slugs, make the garden more appealing to frogs and birds. Enhancing biodiversity and encouraging complexity unifies the ambitions of both gardener and those within the gardener’s sphere of care.

In a similar way, we may be the Earth’s problem and also its solution: exempting ourselves from that responsibility, whether through nihilism or hedonism, is not only a dereliction of our part as a functioning organ of the Earth, it’s indicative of a severe lack of imagination.

In her series of essays, Dispersals, On Plants, Borders and Belonging, Jessica J. Lee asks:

‘…Where and when, exactly, we might locate a version of nature to which we would like to return. At what point do we acknowledge that the environmental legacies of the great acceleration cannot be treated distinctly from the social, cultural, very human power dynamics that shaped them.’

Indeed it cannot. Although in Kimmerer’s discussion above, and underpinning much environmental and ecological discourse, is the not unreasonable belief that things were better for the more-than-human world before we unleashed an ideology of ownership, extraction and hoarding upon it. But it’s important for us not to assume that restoring an unpinpointable past is the only way through what could be a fairly bleak future for all life. If everyone took care of their own backyard (IMBYism), and sought to protect that square of public land from overzealous council contractors, that strip of stream from agricultural run-off, that back garden from herbicides, fungicides and insecticides (and paused for a moment to consider the actual impact of those morphemes), then little by little we might extend our definition of a ‘backyard’ and therefore our relationship with all life. Then perhaps ecocide wouldn’t be a casual outcome of conflict, because we wouldn’t be obliterating lands and their peoples into dust and bone. Perhaps this is a bit of a reach, but we have to start somewhere, however humbly. No one else is coming to do it for us.

There are no Beatrice-esque heavenly beings who will intercept to redirect our course, and outsourcing responsibility to any kind of ‘higher power’ is demonstrably guaranteed to fail us in developing anything like connection. As humans we are quite alone, but only in regard to a higher authority; there is plenty more to keep us company. Perhaps a deeper recognition of the absence of a guiding authoritative hand - whether political or spiritual - will help us to emerge out of our protracted adolescence, out of a world that has killed all the many spirits and goddesses of each grove, river curve or hill that existed across cultures, and into a space of psychological and spiritual maturity in which we recognise ourselves as already whole.

I am often moved when individuals become fixated on a particular variety of plant, passionately making it their cause to protect it and to create an even richer variety of one species or another. These are our guardian angels, those whose natures have assigned deep and precise care to one aspect of existence that is special to them.

A woman who walks her dog daily in my neighborhood collects a bag of rubbish every day. Yes, her contribution is a response to the structural issue of waste, but without her consistent and quiet care things would be worse. She might not be a saint, but her contribution here is holy and there are similar acts of holiness on every suburban street like mine, quiet and unwitnessed.

Beginning small, wherever we are, is the least and the most we can do.

Parallel media

Project documentary: Common Ground

New build state of mind: mid-term microproject

Not a thing of beauty: patchwork thinking project

texts & media

Below are a few of the books and the media that helped to direct my thought over the course of this project.

Books

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, Penguin Classics, 1985

Carl Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Harper Collins,

Charles Eisenstein, Climate, A New Story, , North Atlanta Books, 2018

Masanobu Fukuoka, The One Straw Revolution, , NYRB, 2009

Kahil Gibran, The Prophet, Heinemann: London, 1995

David Graeber and David Wengrow,The Dawn of Everything, Penguin Random House UK, 2022

Lao Tzu, The Tao Te Ching, Arkana, 1985

Jessica J. Lee, Dispersals, Penguin Random House, UK, 2024

Rebecca Solnit, Hope in the Dark, Canongate Books, 2016

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants, Penguin Random House UK, 2020

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Gathering Moss, Penguin Random House, UK, 2021

Kate Raworth, Donut Economics, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017

Joe Simpson, Touching the Void, Vintage, 1997

JRR Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Unwin, 1990

Vron Ware, Return of a Native, Repeater Books, 2022

Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, The Text Publishing Company, UK, 2019

Podcasts (infuential but not referenced)

The Almanac of Ireland

The Blindboy Podcast

The Emerald Green Dreamer

This Jungian Life On Being The Other Others

Planet Critical Team Human

Film (influential but not all referenced)

Aluna (2012), Dir. Alan Ereira Earth, BBC, 2023, Dir. Tom Hewitson Brother Sun, Sister Moon, (1972), Dir. Franco Zeffirelli

Seed: The Untold Story (2016), Dir. Taggart Siegel. Jon Betz

Articles (referenced)

Lyla June, Reclaiming our indigenous European roots

Graham Harvey: An Animist Manifesto

Rebecca Solnit: Slow change can be radical change

A Delicate Activism: Allan Kaplan and Sue Davidoffof the Proteus Initiative

Poems referenced

Allen Ginsberg, Howl

The day lady died, Frank O’Hara

Other

And more that has not been directly referenced here. Naturally, discussions with peers and the Anthropocene seminars were significant.