Transatlantic Relations— an Austrian Perspective— 1921-2021

Martin Weiss

Ambassador of Austria to the United States (2019 - 2022)

occasional paper, volume 5 Transatlantic Relations— an Austrian Perspective—1921-2021

occasional paper, volume 5

Transatlantic Relations—

an Austrian Perspective—1921-2021

Martin Weiss

Ambassador of Austria to the United States of America (2019-2022)

With an introduction by Clemens Sedmak

Professor of Social Ethics and Director of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies

University of Notre Dame

Part of a symposium titled “The U.S.-Austria Peace Treaty at 100: Historical, Political, and Moral Perspectives” Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame

Monday, August 23, 2021

Facilitated by The Nanovic Institute for European Studies

Keough School of Global Affairs

University of Notre Dame

Sponsored by The Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies

Copyright © 2023 by Nanovic Institute for European Studies

Keough School of Global Affairs

University of Notre Dame

Printed and bound in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-0-9975637-2-6

First Edition, First Printing

Table of Contents Post-Lecture Discussion 33 Exhibits 25 Introduction 7 Clemens Sedmak Translantic Relations—an Austrian Perspective—1921-2021 11 Ambassador Martin Weiss

Introduction

Clemens Sedmak Director of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies Professor of Social Ethics University of Notre Dame

If this were a liturgy, I would say, “Peace be with you!” Even though it is not a liturgy, I would like to say peace be with you as we commemorate the U.S.-Austria Peace Treaty after the First World War—a treaty that was signed on August 24, 1921, exactly 100 years ago tomorrow.* Peace is not something we can take for granted, as the most recent developments in Afghanistan have taught us once again. Peace is a gift and a responsibility. In German: Friede ist gäben und aufgaben.

On Thursday, August 19, we hosted a virtual symposium on the U.S.-Austria Peace Treaty from 1921, exploring aspects of the complexity of its text and its impact. Both that event and this lecture have been made possible through the support of the Botstiber Foundation. The Botstiber Foundation was established to promote an understanding of the historic relationship between the United States and Austria. It was founded by Dietrich Botstiber, who was born in Austria and had to emigrate when the Nazis took power, settling in the U.S. and pursuing an exceptionally successful career in technical development. He remained connected to Austria and founded the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies, which publishes the Journal of Austrian-American History. A big thank you to the Botstiber Institute for helping us commemorate the 1921 U.S.-Austria Peace Treaty. A peace treaty is a milestone in the relationship between two countries, and we are grateful for the many years of peaceful relations between the U.S. and Austria.

* This publication is based on an original lecture presented by Ambassador Weiss. It has been adapted and edited for print by the Nanovic Institute.

7

The most important Austrian diplomat in the U.S. who supports these peaceful relations is our guest today. It is my pleasure and my honor to introduce our guest of honor who has come to sunny South Bend: His Excellency Ambassador Martin Weiss, the ambassador of Austria to the United States. Welcome, Your Excellency!

Ambassador Weiss was born in Innsbruck, Austria. His father was a well-known professor of German studies who remains an influential voice in the area of Austrian literature. Having successfully survived a childhood in the household of a university professor, our guest of honor started his career in the Austrian Foreign Service in 1990. He has held some delicate diplomatic missions and posts. Before he was appointed Austria’s ambassador to the U.S., he served as ambassador to Israel, as director of the Foreign Ministry’s press and information department, and as ambassador to Cyprus. He had to show his deep diplomatic skills in zones of conflict.

Ambassador Weiss is no stranger to the United States; he has held postings in the U.S. throughout his career. He started as a human rights attaché for the Austrian Mission to the United Nations in New York, then held the positions of political counselor, counselor for congressional affairs and public diplomacy, and director of the Austrian Press Information Service at the Austrian Embassy in Washington, DC. Most recently, from 2004 to 2009 he served as Austrian consul general in Los Angeles, so we can assume Ambassador Weiss has flown over Indiana and our university many times. Your Excellency, we are grateful and honored that today you have landed in the Midwest for your first visit to Notre Dame.

Ambassador Weiss holds a law degree equivalent to a J.D. from the University of Vienna and an LLM from the University of Virginia. He is married and the father of two. The ambassador took up his duties as head of mission in Washington on November 1, 2019. While he may have enjoyed a few pre-pandemic months, ever since spring 2020 his work has been stalled by the global health challenges that have hit us all. And here we are.

8 clemens sedmak

Today Ambassador Weiss will speak on the topic of “Transatlantic Relations—an Austrian Perspective—1921-2021.” After his talk, he has graciously agreed to a question-and-answer session, and we expect some excellent comments, footnotes, and questions. After the questions section concludes, the Nanovic Institute for European Studies invites you all to a reception to celebrate the ambassador, continue our discussion of the peace treaty, and explore the special exhibit of the Austrian art world on display in the Snite Museum of Art’s Beardsley Gallery.

Your Excellency, thank you so much for being here. The floor is all yours.

9 introduction

10

Ambassador Martin Weiss visits the Golden Dome of the Main Building at the University of Notre Dame, August 2021.

“Transatlantic Relations—an Austrian Perspective—1921-2021”

His Excellency Martin Weiss Ambassador of Austria to the United States

I promised to give a talk about transatlantic relations starting in the year 1921. It has been exactly 100 years since the signing of the U.S.-Austria Peace Treaty, which was published in Bundesgesetzblatt für die Republik Österreich (the Federal Law Gazette for the Republic of Austria) on November 25, 1921. 100 years is a substantial portion of history. When I read some of the comments that were made at the time, one statement I thought was particularly striking referred to this peace treaty as not harsh—as opposed to other peace treaties, apparently—but brought about by “negotiations between two equal partners.” They hoped that the peace that followed would be “the starting point of a new, more fortunate epoch” politically and economically.

Let me fast-forward a century. The United States is now the second most important export market for Austrian products. First, of course, is Germany, a large neighbor. But the U.S. is already number two, larger than our other important neighbors, such as Italy and Switzerland. 100 years after the Peace Treaty of Vienna, our economic relations are extremely strong. To put it into numbers, you see that our exports to the U.S. within 10 years have nearly doubled, which is significant (fig. 1). As you might imagine, we see a small dip in the year 2020—this is, of course, a COVID-19 dip. But I am quite sure that in the year 2021 and the years following we will increase these numbers, likely doubling them again in the next 10 years.

Let me share a few figures when it comes to Austria and the United States. We have much foreign direct investment in the U.S. Approximately 200 Austrian companies have U.S. production sites, employing 30,000 American workers. If you wonder what the Austrians are exporting, there is no Austrian “Phillips” or Austrian “Daim-

11

ler-Benz” or Austrian “Nestlé.” No, Austria is a country of small- and medium-sized companies. So when we say “cars and car parts,” we do not mean Austrian BMWs, but if you open the hood of your BMW today, the engine was most likely produced in Austria.

So, Austria is very much in this niche where we produce a lot of parts you may not know about, but they are very much Austrian. To give you some names you might recognize, BMW has a large production site for engines in Steyr, Austria. KTM, a motorcycle maker, is also in Austria. At the last MotoGP, as an example familiar to any motorcycle-racing fan, KTM won the race, beating Yamaha and other giants of motorcycles. KTM is now competing at that level. And Red Bull—a drink you might use for your studies every once in a while—is produced and developed in Austria. Glock handguns are made in Austria, as well. Now I am not a great fan of handguns, but if you have one, then it should probably be a Glock. And Rosenbauer, which produces special engines for firefighting at airports—these are just a few examples of products made in Austria.

Turning again to foreign direct investment in the U.S., one of Austria’s largest investments is our steel production plant Voestalpine in Corpus Christi, Texas. This investment of roughly €1 billion was made a few years ago. Then there is a Red Bull plant in Glendale, Arizona. Before it opened, every can of Red Bull you drank had to be bottled and filled in Austria and shipped across the Atlantic—not very environmentally friendly–but now the plant in Arizona will bottle and fill those Red Bull cans. Some 3.5 billion cans will be produced right here in America.

Another significant investment is EGGER’s particleboard production plant in Lexington, North Carolina, and I visited this facility because EGGER has invested roughly €700 million in production. It is a company that emerged from World War II because people needed a lot of production materials for building houses but did not have a lot of wood after the war. What they did have, however, were destroyed houses with wood pieces in them. So, the company developed a technology to take the wood, shred it, and produce laminated wood from

12 ambassador martin weiss

13 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

12 10 8 6 4 2 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Figure 1: Austria’s Export Volume to the United States 2010-2020, courtesy of Amb. Martin Weiss.

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 AUSTRIA In Billion Euro:

Figure 2: Austria’s gross domestic product from 1960 to 2020, courtesy of Amb. Martin Weiss.

Austria’s Export Volume to the United States 2010-2020

these pieces. Today this technology is used for all kinds of production—in bathrooms and kitchens, for example. EGGER is a company that operates worldwide and now has a large U.S. facility. Again, this is an almost billion-dollar investment.

Back to Austria, the GDP per capita—or Austria’s gross domestic product divided by its total population—is about $55,000 (fig. 2). There are two problems we see in this chart: first, 2008 and the European debt crisis; and second, 2020 and COVID-19. Otherwise, the line goes up and up. If you look closely, you will see that the line starts in 1960, which is because major developments happened between 1921 and 1960.

First, 1938 was the year of the Anschluss, which is the year when Austria basically ceased to exist due to its annexation into Nazi Germany. Austria’s currency became the Ostmark. There is an intense debate in Austria, which started mostly in the 1980s, about whether Austria was or was not a victim. As seen in photos from the time, some people raised their hands to salute Hitler, so they were somewhat happy to see German troops coming into Austria. That was certainly true for a number of Austrians. The government, however, was not so happy. Many people tried to resist, but Austria was not Poland and no shots were fired. A couple of days later, a great many Austrians ended up in jails and concentration camps. Still, a large part of the population saw the Third Reich as the future for Austria, so it is certainly disingenuous for Austrians today to present themselves purely as victims. And yet I am thankful for this debate about 1938 and the open and frank stock-taking of Austria’s history.

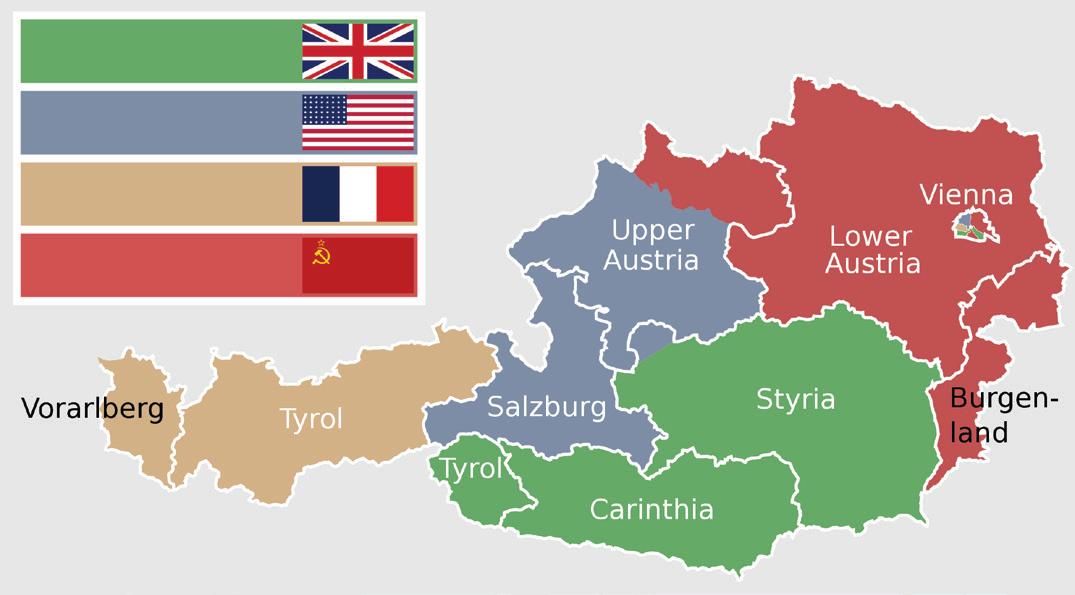

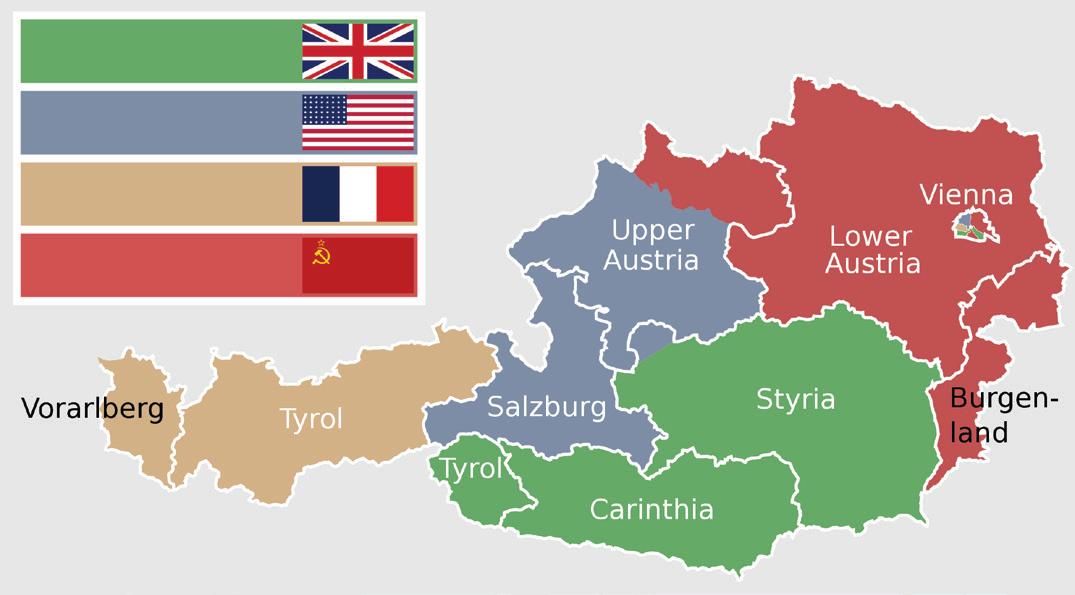

Next, let us discuss 1945, the year the Second World War ended. Vienna became a divided city with four occupation zones: French, British, American, and Russian areas. All of Austria, in fact, was divided: you can see here the different zones (fig. 3). My home towns are Innsbruck and Salzburg (but more so Salzburg). At the time, my father was teaching in Salzburg, which was in the American sector. Of the four nations occupying Austria, we were quite sure that

14 ambassador martin weiss

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Austria_Occupation_Zones_1945-55_en.svg.

License (CC BY-SA 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en.

three of them would leave us at a certain point in time—the fourth one, we were not quite so sure. The problem was that the Soviet zone stretched to the eastern border, adjacent to the Iron Curtain. Austria could easily have become a divided country, as was the fate of Germany, were it not for a stroke of luck. Between 1945 and 1955— that is how long it took for Austria to become an independent nation again—there was the European Recovery Program, better known as the Marshall Plan. Growing up in Salzburg, we used to go swimming at the AYA Bad, the public swimming pool. I do not think many of my friends knew what “AYA Bad” stood for. It was the American Youth Association Bad, or “Bath,” and is still used today. The AYA Bad was presented by the general of the American forces in Salzburg as a gift to the Austrian youth in 1950, paid for with funds from the Marshall Plan, which was no small feat. Remember that until 1945 the U.S. was at war with Austria—perhaps not Austria technically speaking, but because Austria was part of the Third Reich, in that sense they were at war. And only five years later, we get a swimming pool paid for by the United States of America! Now that is quite stunning.

15 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

Figure 3: Occupation zones in Austria between 1945 and 1955. October 28, 2020. Image. https://

Creative Commons

Also, keep in mind that approximately 63 percent of Austrian electricity is produced by hydropower, and one of our most famous dams, the Kaprun Dam, was built with money from the Marshall Fund (fig 4). This is remarkable, and with all the talk these days about Afghanistan, this truly is nation-building, only a few years after a devastating world war. When it came to the Marshall Plan and its funds for Europe, it was the United States that truly built this new bridge with Europe.

Now we turn to 1955: the year Austria regained its independence, its freedom. That is when the State Treaty was shown to the cheering masses in Belvedere Palace. The moment was ripe; it began ripening in 1953. When Soviet leader Joseph Stalin died, Nikita Khrushchev took over, and there was a moment of thawing in the Cold War. Austria, smartly at the time, grasped that moment. We could not join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO); the Soviet Union would never have let Austria join NATO. So Austria, at the time, was to be a neutral country built on the model of Switzerland. Not many Austrians knew what that even meant, but it was the price of freedom, so they embraced it graciously. Austria became a neutral country in the middle of Europe. If today you were to ask an Austrian, “Is Austria a

16 ambassador martin weiss

Figure 4: Bhavna. Kaprun Dam, Austria. Image. https://stock.adobe.com/315216759. Education License.

neutral country?” it would be second nature to answer affirmatively, but it was not in 1955, let me assure you.

After 1955, economic development was the name of the game, and the decisive year for Austria was 1995. That is when Austria joined the European Union (EU), which brought it strongly into the Western economic system. Of course, Austria had applied to join in 1989, the year the Iron Curtain fell, which opened this avenue to move Austria into the EU. Since then, Austrian foreign politics are, in reality, EU foreign politics. I was still working on my first assignment at the Austrian Embassy in Washington in 1992. At the time, Austria was not part of the EU, and I can tell you that working for an Austrian ambassador is completely different since becoming an EU member state, so 1995 was critical. If you look closely, you can see that Austria is not exactly in the center of the EU (fig. 5). That was remedied a few years later, in 2004, with the EU’s eastward enlargement (fig. 6), which was important for Austria. Ideologically, we always saw ourselves at the very heart and center of Europe, and with this round of enlargement to include our eastern neighbors, we actually were.

Reis, Júlio. EU15-1995 European Union map

. Image. https://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File :EU15-1995_European_Union_map_enlargement.svg . Creative Commons License (CC BY-SA 2.5), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en

17 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

Figure 5: 1995 European Union enlargement.

Figure 6: 2004 European Union enlargement.

enlargement

Now, on today’s topic of transatlantic relations, as I said, Austrian transatlantic relations are European transatlantic relations. So when the U.S. introduced a punitive steel and aluminum tariff in 2018 under then-President Donald Trump, it had an immediate effect on EU transatlantic relations, and, thus, on Austria. The steel plant built in Corpus Christi, Texas, that I mentioned earlier has lost approximately €200 million to these tariffs, which is a significant sum for a company of this size. I am glad to say that we have moved along with President Joe Biden. We are coming now to a truce-like situation and hope that this dispute can be resolved. The question is not an easy one to solve because we are talking about international competition and American jobs. These tariffs are not something that President Biden ended on his first day in office. This issue still needs work. While we do have an avenue to tackle and resolve this disagreement, I assure you, it will not be easy.

Turning to the Airbus-Boeing issue, this is an endless discussion between Europe and the United States—20 years of discussion, with tariffs imposed on both sides of the Atlantic to the tune of some $30 billion each year. Again, here we have come to a truce. For five years there will not be any tariffs because of the Boeing-Airbus dispute. Meanwhile, we hope we can work it out because it does not make sense to have this kind of dispute and to have these tariffs. We are allies, but still, we hit each other with punitive tariffs. Austrian companies have lost millions as a result—we are talking about drinks, cheese, and machinery completely unrelated to this dispute. This is a way to create pressure, but while we are busy imposing tariffs on each other, China is building wide-body airplanes and selling them with state subsidies all over the world. How does that make sense for our nations? I’m glad we are working to resolve this dispute today.

Another issue that is hotly debated between the U.S. and Europe is the taxation of digital goods and services. Austria has introduced such a tax, much to the dismay of the United States. France and other countries have a digital tax as well. The concept behind it is quite simple, and it has a lot of political pull. You have companies—like

18 ambassador martin weiss

Facebook, Twitter, and others—that create a huge stream of revenue in Austria and do not pay a single cent of tax into Austrian coffers. Austrian companies say: “How can that be fair? I’m a medium-sized company. I have to pay all of my taxes. And they can find a different way around this tax system.” This is simplifying a complicated issue, but the political dynamics are simple: no European politician can say, “Let’s say it is nothing. We’re all friends here, and let’s forget about this stupid tax system.” This issue must be negotiated, but thankfully, it is now being discussed. We will not solve it as we started, by again imposing punitive tariffs on one other, but we hope to be able to find a solution within the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) that we can live with on both sides of the Atlantic. It is not easy for an American president to accept additional taxes on American companies on revenues made abroad, because you would always say: “If anybody taxes American companies, it should be the U.S.” This is a complicated question, and the details are the trickiest part. We are, however, currently working in Paris to find a solution.

Staying with the topic of transatlantic relations, there is one issue we are all talking about these days, and that is our relationship with China. Europe finds itself in a sandwich position. For us, China is a partner and a competitor, of course. It is also a huge market and a place where we produce a lot of our goods. And sometimes you read in the media that we are entering a new Cold War with China. But during the Cold War of the last century, economic relations between the West and the Soviet Union were practically nonexistent, except for some raw products. What Soviet products would you find in your household in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, or 1990s? Chances are the answer was zero. What Chinese products do you find in your household today? Definitely not zero. The economic relationship between Europe and China, and the U.S. and China, is so much stronger, and this comparison with the Cold War and the Soviet Union is, I think, a complete fallacy. Just look at the numbers for American companies. Last year, GM sold 2.5 million cars in the U.S. and 2.9 million in China. The same is true for Daimler-Benz and BMW. BMW sells approximately

19 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

300,000 cars in the U.S., meanwhile selling 800,000 in China. The economic cooperation between Europe, the United States, and China is strong, make no mistake. We can talk about all the onshoring and resourcing in the world, but this is a relationship that is strong and lasting. You can build all the TVs in Chicago, made in America, but chances are they will be smaller and cost probably ten times as much. I am not sure how much public support there is for that.

Resilience and resourcing issues are important for all of us. I will give you one personal example. I bought a new BMW when I came to the U.S., and being a good global citizen, I bought a hybrid version. A month after I bought it, the car did not work anymore because there was a problem with the battery. The car had to be recalled. Now BMW cannot repair the battery in your car because every single battery that BMW uses is bought from Korea. So, for two-and-a-half months, my car was standing still. Mighty BMW finds it impossible to repair a new car for me. That is a question of resilience, and COVID-19 brought it home to us that there are some issues that we all want to take a hard look at. When it comes to pharmaceuticals and rare materials, there are issues we need to address, and we want to address those together. I think it is an important lesson that we have learned, and nowadays Europe and the United States sound similar when we talk about China. We have common interests. Why is the Chinese market not open for American companies, and why is it not open for European companies? We definitely have joint interests that we can work on together. I remember when there were statements from the White House basically saying Europeans are just as bad as the Chinese, only a little smaller. I do not think President Biden would say that, and so I think we have moved on, and rightly so, because there are still disputes we want to resolve together.

Speaking of joint initiatives, climate change is a substantial topic Europe and the United States are working on together closely. As regards China, this is one area where we meet in the same boat. But while climate change is a topic that sounds beautiful on the surface, underneath it is extremely complicated. Take the phrase “carbon

20 ambassador martin weiss

adjustment,” for example, which means tariffs on foreign products that have not been produced as sustainably as your own products. Why would European companies pay all these taxes in order to produce cleanly, only to allow products on the market that have not been produced cleanly? You have to adjust for this kind of situation, and that can lead to a huge conflict between Europe and the U.S. If we introduce punitive tariffs, calling them carbon adjustments, on American products that have not been built to the same standards as European products. There you have a huge dispute. So, while in theory, we are all on the same page on climate change, in practice it is a tough discussion.

There is also a deep political divide when it comes to this topic. In America, every poll you look at asks a Democrat and a Republican about climate change, and you get two different sets of answers. It is still the same climate, still the same air, but at the end of the day, there is a huge political divide. Not so in Europe. In Austria, we have a conservative government, a Conservative-Green Party coalition, so conservatives have to meet green demands. You have to go far to the right in Europe to find someone who would basically deny climate change, but it is a politically fraught and complicated topic when you look at the details. Again, nothing can be achieved by Europe alone, or by the U.S. alone. It is definitely an area for cooperation.

Now, as I said, our politics with the United States are for the most part European politics, but there are issues where Europe does not take a position. One is the case of the Balkans. Croatia is now a member of the EU. The other Balkan states are not. For Austria, one of the priorities of our foreign politics is to bring these countries into the EU. How does it make any sense that these small countries—and we are talking about five to seven million inhabitants per country—are not part of the European Union? Every country around them is part of the EU, but they are not. That creates vacuums, and both nature and politics abhor a vacuum. It creates a playground for Russia, China, and Turkey, not to mention drug dealers. It creates all kinds of mischief and negative dynamics. Still, there is no joint European position on these

21 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

countries joining the EU. Rather, these days we are constantly moving the goalposts. The moment one of these countries achieves what we ask for, we ask them for something else—which is deeply disappointing for these countries that consider themselves European.

Regarding the Balkans, Austria and the U.S. have practically identical positions. We both favor them joining the EU as soon as possible. This has to be the goal, and we see eye to eye with the U.S. in a way we do not with any European country. If you follow the debate in France, for example, there is a lot of hesitation about Kosovo and Albania, as though their entry would destabilize the EU. We have played this game before in the EU. We have brought countries into the union that did not quite measure up to Europe at the time, but still, there always was at least one success story. Why can we not repeat that success? This is an issue for close collaboration with the U.S. to find better answers than we have in the past.

Another issue we have discussed, which was resolved, is Russia’s Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline. Austria was one of the investors in this pipeline. Our largest energy company vested €1.5 billion in building Nord Stream 2. You have read about this. It has been a big debate between the U.S. and Europe. And we have basically concluded that this pipeline will be built. For Austria, this was always very much an energy question. I spoke earlier about hydropower, and it is true that hydropower is extremely important. But for our industry, we need cheap and affordable energy for the next twenty or thirty years because Austria does not have any nuclear power and we closed our last coal plant last year. We cannot meet every energy need with hydro, wind, and solar sources currently. We need something in between. Natural gas is a cheap energy resource that we have used, are using, and will be using for years to come, and whatever you may think about Russia, it has been a stable supplier for decades. Nord Stream 2 is another way of bringing energy into our market, so we have been supportive. Other European countries have criticized the pipeline, especially the Baltic countries. Poland is unhappy, as is Ukraine. But we no longer have a dispute with the U.S., even

22 ambassador martin weiss

though before there were extraterritorial sanctions we thought were completely unacceptable. We can debate about where our energy should come from, but this is a debate we need to lead in Europe. It will not be led by Texas Senator Ted Cruz alone.

Just a word now about how Austria sees itself, and always has seen itself. The OSCE, which I mentioned earlier, is one of the international organizations headquartered in Vienna. It has fifty-seven members and is the forum for talking about the Ukraine crisis. In the OSCE, you have Russia, Ukraine, the United States, and the West; we are all sitting at the same table. This is a forum that has worked exceptionally well, and this is exactly how Austria views its role—to be a facilitator, a meeting point where these discussions can take place. So, the OSCE is a forum that is extremely important. Regarding the United Nations (UN), in 1955 Austria became a free country again, and two months later it joined the UN. UN membership had very much been in the back of our minds; Austria wanted to immediately be back on the international playing field. Vienna became one of the UN’s three headquarters, along with New York and Geneva, and the home of several important units, including the International Atomic Energy Agency. To make this happen, the late Bruno Kreisky, Austria’s chancellor from 1970 to 1983, invested significant political and financial capital. These agencies remain in Vienna to this day, an important part of the international infrastructure.

As I said, Austria likes to think of itself as the facilitator. The June 2021 Iran talks, held in Vienna, serve as a recent example of the nation filling this role. Robert Malley, the U.S. special envoy for Iran attended these talks. Since then, we have had elections in Iran, and the Iran talks are now on ice. We hope they will be thawed before long. Again, here Vienna served during the last round of Iran talks as a meeting point where people could come together to discuss a complicated issue—exactly how Austrians see themselves and their nation. I spoke earlier about neutrality. I spoke about international relations, and I think this is the role Austrians see for themselves. In my opening remarks, I referred to the hope at the time to find “a new,

23 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

more fortunate epoch in our political and economic development.” If those people from 1921 could see where Austria stands now in its relations with the U.S., 100 years later, I think they would be quite happy, and rightly so.

24 ambassador martin weiss

Special Exhibit of Austrian Artwork for “The U.S.-Austria Peace Treaty at 100: Historical, Political, and Moral Perspectives”

The exhibit showcased artworks from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, created in the years leading up the First World War, through the early years of the First Austrian Republic co-sponsored by the Nanovic Institute for European Studies and the Snite Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame, and made possible by the generous support of the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies (BIAAS).

25 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

Unknown American artist, Laundry on the Russian Front, Austrian Army, World War I, ca. 1915, albumen print. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Gift of Janos Scholz, 1981.031.151.

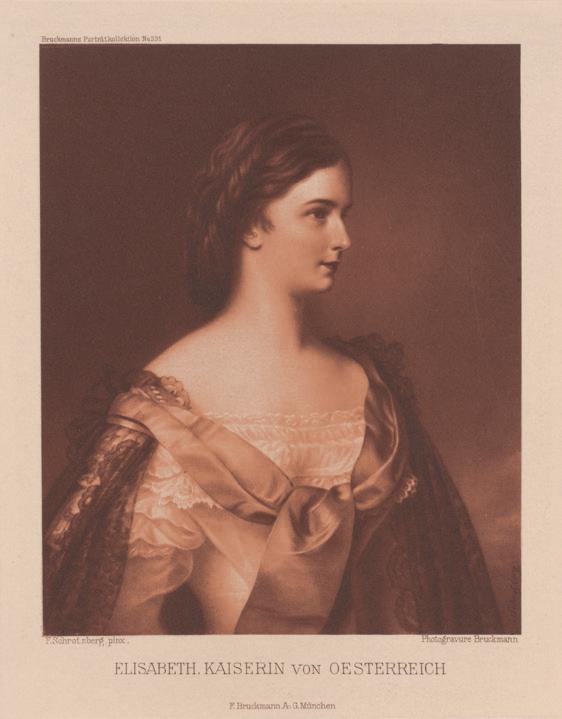

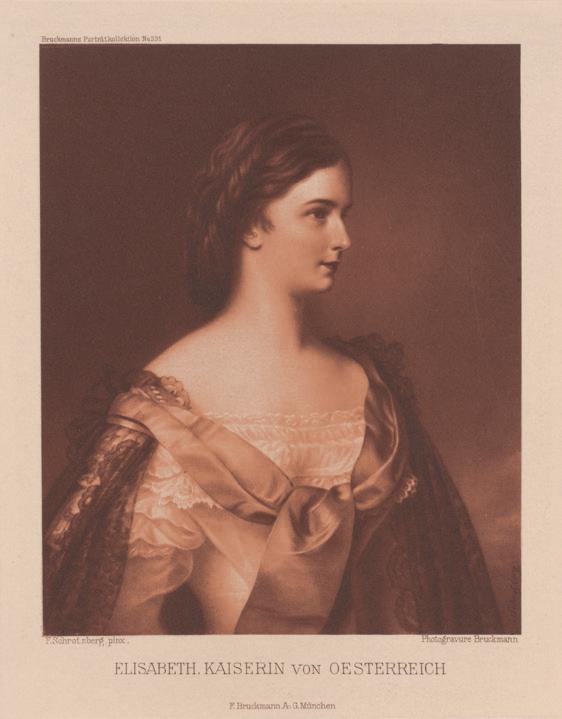

Unknown European

,

26 exhibits

artist, Elisabeth, Empress of Austria

ca. 1870 - 1890, photogravure. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Gift of Janos Scholz, 1978.081.039.

Georg Caspar Prenner, Presentation of the Austrian Arms to the Virgin, 1720 - 1766, oil on panel. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Gift of Julius Raab, 1959.002.

Other Austrian Artwork on Display

27 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

Karl Klaus, Secessionist Charger with Peacock and Tigers, ca. 1911, faience with hand painted polychrome enamels, silver and gold gilt. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. William L. and Erma M. Travis Endowment for Decorative Arts, 2002.035.

Joseph Maria Olbrich, Candlestick, ca. 1900, pewter. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Friends of the Snite Museum of Art Fund, 1985.064.001.

Otto Prutscher, Saucer of Demi-Tasse Cup and Saucer, ca. 1907, brilliant, clear, glass with geometric wheel-cut overlay in deep blue glass. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. William L. and Erma R. Travis Endowment for the Decorative Arts, 1998.050.

Josef Hoffmann, Ceramic Cup and Saucer, ca. 1920, porcelain. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. William L. and Erma M. Travis Endowment for Decorative Arts, 1985.076.

Josef Hoffmann, Chair for the Cabaret Fledermaus, ca. 1907, natural, polished beech. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Gifts of Stuart M. Kaplan and Mrs. Frank E. Hering, by Exchange, 1989.027.

Josef Hoffmann, Coupe with Fluted Handles, ca. 1920, brass. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Gift of Rev. Edmund Joyce, C.S.C., 1989.027.

Josef Hoffmann, Flower Basket, ca. 1905, silverplate with original glass liner. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Whirlpool Corporation fund, 1985.065.002.

Josef Hoffmann, Vase, ca. 1900, green, iridescent glass. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Walter R. Beardsley Endowment for Contemporary Art, 1991.004.

Joseph Maria Olbrich, Fish Knife and Fork, ca. 1900, silver. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Friends of the Snite Museum of Art Fund, 1985.064.002.

Du Paquier Porcelain Manufactory, Charger with the Rape of Europa, 1730, hard paste porcelain. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Virginia A. Marten Endowment for Decorative Arts, 2015.070.

Dagobert Peche, Vase, ca. 1918, silverplated alpaca. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. Gift of Mr. Peter C. Reilly, by Exchange, 1990.006.

Jutta Sika, Cup and Saucer, ca. 1902 - 1904, glazed porcelain. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. William L. and Erma M. Travis Endowment for Decorative Arts, 1991.042.

28 exhibits

29 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

Monica Caro (left), senior associate director, Nanovic Institute for European Studies and Ambassador Martin Wess, participate in a private tour of Austrian art with Joseph Becherer (right), director and curator of sculpture of the Snite Museum of Art, and other members of the museum staff.

Ambassador Weiss at the Snite Museum of Art

Becherer (left) and Amb. Weiss (right) review paintings in the gallery.

30 exhibits

Becherer (left) and Amb. Weiss (right) discuss the statue on display.

Becherer (left) with Amb. Weiss and Clemens Sedmak (right), director of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, examine a metal work sculpture.

31 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

Amb. Weiss leads a lecture in a gallery at the Snite Museum of Art, located on the campus of the University of Notre Dame, on August 23, 2021.

Nanovic Institute Director Clemens Sedmak, professor of social ethics in the Keough School of Global Affairs, welcomes the audience to the lecture and introduces Amb. Weiss.

32 exhibits

Amb. Weiss presents his lecture on 100 years of U.S.-Austrian relations after the 1921 peace treaty.

Amb. Weiss speaks with students during a reception at the Snite Museum of Art.

Student: You were talking about the tariffs of 2018, which obviously put a strain on transatlantic relations between Austria and the U.S. What did the pandemic do to this relationship, and what influences will it still have considering the restrictions on travel and visas?

Ambassador Martin Weiss: COVID-19 had an impact on economic development, as is fairly clear, but it is the same story for us all. What Austria did is what the U.S. did during the crisis. The government took a lot of money and pumped it into the economy. We essentially paid Austrian companies to employ people they could not use so they would not let them go and they would not be unemployed and on the street. In that sense, I think we will get through this quite well. We can see now that the U.S. economy is starting again quite strongly. China came through the crisis quite well. Europe is a little bit behind, but I think it is working out. Again, with the vaccinations, Europe was also a bit slower, but now we are nearly at the same point. There was a big European debate about vaccinations and why some countries did this and did that. I’m happy that Europe held together. We purchased vaccines together because, for all the criticism of the slowness of the EU, what would have happened to the EU if one member had outbid the next on the vaccine market? The Bulgarians would not have had any vaccines, and we would have had 95 percent vaccinated. What would that do for the EU? I think we are actually on the same page.

The problem is still the travel restrictions. Europe has reopened to American travelers, and I think it was the right move, but we get a lot of questions from our citizens. They ask why Americans can travel to Europe, but they cannot travel to the U.S. Is there not usually reciprocity? Indeed, usually, there is, so why has the U.S. not reopened to Europeans? There are various explanations. It is definitely not infection rates because if you look at some countries whose citizens can travel to the U.S., they have much worse rates than Western Europe and the EU. I think the real reason is that COVID-19 provides an opportunity to have limited travel, for example, between the U.S. and Mexico. If you start reopening to all Europeans and the rest of the

33 Post-Lecture Discussion

world, why not reopen to Canada and Mexico? It is all part and parcel. That means you have a very different refugee or asylum-seeker situation on the southern U.S. border. I think that is one of the reasons why the U.S. is not in a rush to lift all restrictions for the time being. For Europe, it is not pleasant. Daily, I have dozens of cases of Austrians—professors, business people, and others—who would like to, but cannot, travel to the U.S. All I can tell them is, you just have to hold out a little longer.

Student: Regarding administration changes in the U.S., you see two political parties and two different administrations, especially in the most recent years. With your job, can you share what that means when you have a new administration from a different political party? What do negotiations look like across the divide and across the aisle?

Weiss: When I was here in the late 1980s through the early 1990s, I always felt that there was still a working-across-the-aisle mentality. In the Senate, you had these old, grand senators who would always work with the other side. I think that some of that has been lost. It seems that the divide has become deeper. For our job, it is actually quite complicated because what you do in the U.S. when a new administration comes in is something we are unfamiliar with. In Austria, civil servants run the country. The civil service is very strong, and personnel stay in their jobs no matter the political environment. In the U.S., you have a new government, and you change the Cabinet: the deputy secretary of state, the assistant secretary of state, and the deputy assistant secretary of state. And you do that in every ministry! For us, this is unusual and hard because politics is also about personal relations. You have to know the people to get things done, and if everybody changes, in addition to the context of COVID-19, where you basically only have the chance to meet someone during a Zoom conference, it makes my job very hard. Before the pandemic, there were a few normal months. Usually, we would have been much quicker to engage with a new administration and all its new players, but it has not happened and it is complicated. As a senator, Ted Cruz has a hold on a number of nominees for various positions in the government. And he relates the hold to Nord Stream 2. This is difficult. It should be the

34 post-lecture discussion

entire U.S. leadership that makes political decisions, not one senator. The fact that a number of key persons are not in their positions is challenging, and it is not true, as some foreign policy experts claim, that it does not make a difference if they come three months later. In this Afghanistan crisis, we are talking to the U.S. every day, and every day there is something that we want to discuss. It makes a huge difference whether there is a U.S. ambassador to Austria. Victoria Reggie Kennedy has been nominated to be your ambassador to Austria. She has not had a hearing because she is part of the hold.** She can make a huge impact in Austria if she goes and talks to our chancellor and the minister of defense. If you only had, for example, a political secretary making the case for America; I am sorry to say, this is not the case. It does make a difference on many levels. In the U.S. you do not have an assistant secretary for European affairs. You do not have an ambassador to Afghanistan. How does that make the U.S. better? For me, this kind of transition is, on the one hand, fascinating, but on the other hand, a little bit frustrating. We will work our way through it.

Audience member: When countries enter the EU, how does it impact their balance sheets and also the individual balance sheets of the citizens of those countries?

Weiss: It makes a huge change in a country. For all of the countries joining—and you can draw a line for Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Austria—GDP per capita goes up year by year, and strongly. What it also means is they diversify. Earlier, I discussed how Germany is our strongest trading partner, which is natural because it has a strong economy and the same language. With Austria’s joining the EU, the percentage of our trade with Germany went down drastically because we diversified. Austria developed new markets because of the possibilities the EU gave us. It adds wealth to a country, and oftentimes, it also means it is extremely hard for politics to attack a monopoly because it will be so unpopular with your population. It is complicated, but within the European Union, you can tackle these situations much more easily. What it means is that Austrian politicians make deci-

35 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

** Between the lecture and this publication, Ambassador Victoria Reggie Kennedy assumed office as the U.S. Ambassador to Austria on January 12, 2022.

sions in Brussels, and then if people complain, they say, well, it was Brussels that decided, not mentioning that they sat at the table, too. But membership also allows you to restructure your economy. Things that had not happened until 1995 happened quickly in the ensuing years. We became part of a bigger system, and Austrian intricacies no longer decided our markets, making some people rich and some people poor. You are in an EU market. For Austria, economically speaking, nothing better could have happened than joining the EU. You lose a little sovereignty, but sovereignty oftentimes is just a headline, not much more. I have never understood how leaving the EU makes Britain stronger; it has made Britain so much weaker. The most important benefit when Britain was in the EU was you could conduct European politics through London for the most part, but not anymore. Being in Europe gives you strength and gives you a voice, and the beauty of the EU is there are only small countries, even if some of them do not know it yet.

James Otteson: *** My question is about immigration. Before COVID-19, Austria had very different immigration policies from the U.S. I wonder what you think the immigration policies in Austria will be once we get out from under the cloud of the pandemic, and what effect do you think those policies will have on the Austrian economy and, more generally, on the EU?

Weiss: Immigration is a complicated topic. In 2015, I went to Israel as an ambassador. This was the year when we had a refugee crisis in Europe, and it was a nightmare. At the time, whoever made it out of Syria could get into Turkey, and from there they could basically walk through the Balkans into Western Europe. That was essentially the system, and in 2015 there was a crisis where we had hundreds of thousands arriving. In the eastern part of Austria, you could not drive on a highway because it was used as a walkway for thousands every day. There was a complete loss of control, and it was overwhelming for us, and it is still a trauma in European politics. Of course, for certain

36 post-lecture discussion

*** James Otteson is the John T. Ryan Jr. Professor of Business Ethics and the Rex and Alice A. Martin Faculty Director of the Notre Dame/Deloitte Center for Ethical Leadership at the Mendoza College of Business, University of Notre Dame.

parties, it was the best thing that could have happened, because if you are far enough to the right, you can play it up beautifully. Even if you are not to the right, if you suddenly lose control, if a country cannot control its borders, then things get very complicated. The crisis brought home something that we often forget: what we have done in the EU is unique—that you would allow your neighbor to control your borders for you. This is a huge sign of trust. Think about it. It is as if the U.S. were to say, “You know what, it is okay if the Mexicans control our southern border; that is good enough for me. Everyone who enters Mexico can come to the U.S.” Would you ever do that? No! But in Europe, we’ve done it. We’ve removed the Croatian border, so Croatia controls the border and whoever makes it into Croatia is thereby in Austria because between Croatia and Austria there is only a sign that says you are now entering Austria. We took this huge leap of faith, and the foundation of this faith was suddenly shaken vehemently during this migration crisis. The question was, how do we do this? The system is not there yet. It is extremely complicated with the asylum convention because it could mean that you simply say: if you have entered Austria through a European country (and that is our law as it is written right now), then you have been in a safe place, so there was no real need for you to come to Austria, and I will push you back to the last safe country. This all ends in Greece and Italy, right, because this is the only way you can come into the EU. You come by boat over the Mediterranean Sea, or you come from Turkey to Greece. We leave it all for the Greeks and the Italians. That is not exactly solidarity and will not make them very happy. But then, the discussion gets extremely complicated: How many refugees are you willing to take? How can we divide them between one country and another? How can we control it? Migration is always a game of numbers. We can integrate a number of people, but only so many. And look at Austria. Where do you think a refugee would go? To a Tyrolean cow village in the mountains? No, they all go to Vienna, and probably to two districts in Vienna because this is where they feel most comfortable. If you take 100,000 and put them into a city of 200,000 in two locations, you have a problem. How do we handle that in our schools? In a classroom with 23 students,

37 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

21 of whom do not speak German as their mother tongue, how many teachers do you need to teach them to a functioning standard? It is a really complicated discussion, and we have not solved it. At the end of the day, there is a lot of migration, and it is a huge challenge for the EU. In the U.S., you are often able to see the strengths of migration. We have also seen it in our systems, that it brings a lot of strength to a country, but it has to be managed. The lesson we have learned is that no kind of happy talk will solve those problems. If you have this issue in a school, what you have to do is bring at least two teachers in for every class, and maybe a third teacher to teach them in the afternoon. If not, you have a problem for the next fifty years. It takes money, it takes effort, it takes politics, and it is hard work for the European Union. There are no easy answers.

Student: Throughout your career, you have had to resolve many conflicts. I’m wondering which conflict-resolving techniques you find most useful.

Weiss: This is a difficult question. Yes, I think there is a role for diplomacy at the end of the day. I think that is of course the lesson, that is what every diplomat will tell you. You know, we have seen it in numerous conflicts. Weapons will only get you so far, and we all know the Theodore Roosevelt quote, “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” You certainly should have that stick if need be, but you have to talk, you have to listen, and you have to understand where the other side is coming from. I was in Israel for four years, and of course, Iran looks much different from Israel than it does from the U.S. or from Austria. You have more of a luxury talking about an issue that is further removed. For Israel, it is much more immediate. No matter what the political rhetoric, and no matter what the political pocket change you can make from it, I am 100 percent sure that this is an issue you cannot solve by military means. Maybe some senators, whose names I will not mention, think you can bomb Iran back to the Stone Age, but I do not think that is the answer. Resolving conflicts is complicated. It takes hard work. It takes listening. And I think the best technique is putting yourself in the shoes of the other. It is very hard to do and

38 post-lecture discussion

very easy to say, but I think oftentimes it is the only way you can move forward. That will be my cheerful note to end my talk.

Sedmak: That was cheerful. And you know, putting myself in your shoes, you have given us a lot, and you need a drink now! First, let me say thank you to all my colleagues from the Nanovic Institute. Thank you so much to the Botstiber Institute for Austrian-American Studies (BIAAS) for making this possible. Also, thanks to the Snite Museum. Finally, we want to thank our guest of honor. We have a little gift for you. It is a harmless thing you may wear in your professional capacity advertising Notre Dame. Your Excellency, thank you so much for being our guest.

39 transatlantic relations—an austrian perspective—1921-2021

40

ISBN: 978-0-9975637-2-6