In the dim blue glow of Thunderchild's forward command deck, where console lights blink like tired constellations, the sound of laughter is rare enough to make heads turn. But tonight, between shift rotations and the ever-present hum of shields cycling, a ripple of applause travels down the corridor. The crew—normally stone-faced and sleepdeprived—leans against bulkheads with something approaching delight.

The source is the “Rhythm Corps,” a small troupe of professional dancers — both men and women — who have been quietly traveling with EDENCOM fleets for months. In a war of attrition fought against faceless foes in numerous star systems, they have become unlikely heroes: artists whose job is not to fire weapons, but to remind everyone why the fight matters in the first place.

Their performances are not the neon-lit spectacles one might expect from civilian pleasure hubs. Space is limited, and

audiences often show up still wearing tactical gear. Yet the dancers adapt— using minimalist staging to create brief pockets of humanity aboard ships built for war.

“We’re not here to distract them,” explains lead dancer Ariel Vanice during a brief respite between shows. “We’re here to give them a moment where everything isn’t alarms, drill, and shouted commands.”

In garrisons the effect is even more pronounced. Soldiers gather in crowded hangars or improvised rec halls, sitting on supply crates while the troupe transforms the room with movement, music, and playful banter. The dancers’ presence sparks something almost forgotten: camaraderie not fueled by adrenaline, but by shared enjoyment.

Command is surprisingly supportive. According to Morale Officer Lt. Liora Schell, incidents of fatigue-related er-

rors drop for several days after a visit. “You can reinforce a shield,” she says, “but to reinforce a person? You need connection. These performers provide that.”

Back aboard the Thunderchild, as the last notes fade and the crew disperses to their stations, a mechanic wipes grease from his hands and grins. “For five minutes,” he says, “I didn’t think about the next jump or the engines. Five minutes of feeling alive. That’s worth more than anyone understands.”

And as the fleet prepares to disappear once more into the cold darkness, the dancers stow their equipment. But soon they will bring it out again for the next group of soldiers — bringing light, movement, and a reminder of home to the spaceships where service often seems endless.

Did you know?

It started as a Caldari militia MTAC!

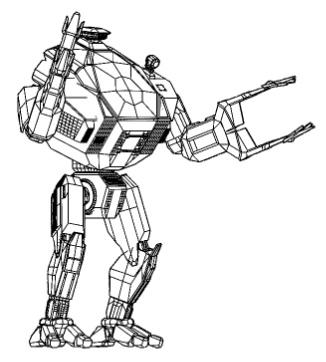

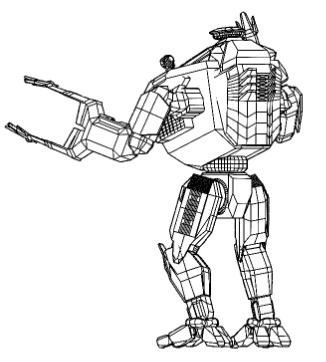

The Power Loader Mk1 “RIPPER” stands like a steel titan among the humming warehouses and docking bays of EDENCOM installations—an industrial mech bred from war, refined for labor, and perfected for the grinding rhythm of frontier logistics.

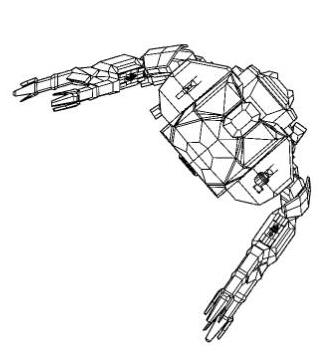

The earliest seeds of the RIPPER were planted during the Caldari–Triglavian conflicts, when frontline militia units relied heavily on mechanized suits for combat. One of the most notable designs was the Dyishi MTAC, assault exosuit known for its agility and brutal close-range efficiency.

The Dyishi frame, built around hightorque actuators and a compact armored profile, earned a reputation for “moving like an angry animal in a hallway.” As the conflict intensified and logistics played constantly increasing role, engineers began experimenting with non-combat variants for shipboard tasks—moving ammunition crates, replacing damaged bulkheads under fire, or clearing wreckage.

These improvised “support Dyishis” weren’t official but became common enough that engineers nicknamed them “dockyard Dyishis.” They were clumsy for logistics but invaluable in emergencies.

When EDENCOM was formed, it inherited enormous logistical strain: new bases, vast material flows, and constant resupply demands across embattled systems. Human labor alone couldn’t keep pace.

A directive went out: develop a mechanized logistics suit using existing militia tech, but optimized for endurance, modularity, and safety.

Caldari engineers offered a proposal: convert the Dyishi platform into a dedicated industrial loader.

The idea was met with skepticism at first — why rework a war machine instead of designing a fresh chassis? But the Dyishi’s frame was proven, rugged, and compatible with mass-produced parts across multiple Caldari foundries. In wartime economics, practicality beats elegance.

Thus the Mk1 Power Loader was born. At four meters tall and two meters wide, the RIPPER’s silhouette carries unmis-

takable echoes of its ancestor, the Caldari militia combat MTAC Dyishi. Where the Dyishi was lean and predatory, the RIPPER is broader-shouldered, heavier, and built for punishing workloads rather than battlefield ambushes. Yet the lineage is there — muscular silhouette, the bipedal stance, and the unmistakable hum of a military-grade clusters of servomotors when it moves.

Inside its bulky torso sits a pressurized, fully life-supported cabin designed for a single pilot, sealed against radiation, vacuum, and particulate contamination. The cockpit wraps around the operator like a protective shell—multi-layered smart glass, reinforced structural ribs, and an internal HUD that maps every joint, power feed, and external stress point in real time.

The Mk1 can be directly piloted or remotely controlled from a tethered or wireless console. When remote, the mech’s sensor suite — stereo cameras, lidar, pressure scanners — streams a perfect, latency-tight picture to operators even in dense EM environments.

The most distinctive features of the RIPPER are its precision manipulators. They’re mounted on reinforced armatures capable of micro-adjustments down to millimeter accuracy, yet able to clamp down with enough strength to shift half-ton crates as if they were plastic toys.

A force regulator ensures sensitive cargo—fragile electronics, fuel cells, cryogenic tanks—can be maneuvered without damage, even in the chaos of a busy hangar.

Multiple hardpoints are distributed across the arms, shoulders, and dorsal frame.

Depending on mission loadout, the RIPPER can mount tools such as:

• Heavy cargo pincers

• Magnetic clamps

• Industrial cutting torches

• Drum-winches

• Zero-G maneuvering kit (microthrusters with auto-stabilization)

With the Zero-G pack installed, the mech becomes a drifting workhorse, capable of fine maneuvering along station hulls, ship exteriors, and cargo hold superstructures.

Though it is no longer a battlefield machine, the Mk1 RIPPER moves with the purposeful grace of a creature forged for conflict and repurposed for creation. In EDENCOM bases, crews affectionately call them “iron hands” — dependable giants that haul, lift, and secure the endless procession of containers that keep frontline stations alive.

Whether stomping across a gravitybound depot or drifting silently along the skeletal scaffolds of an orbital shipyard, the Power Loader Mk1 “RIPPER” embodies the perfect hybrid of militarized engineering and industrial reliability — a descendant of war now keeping the wheels of civilization turning.

They are developing, but in a terrible direction.

Rogue drones were once simple utility machines — maintenance bots, mining crawlers, hull-cleaners meant to scrape fungus off bulkheads. But the species we now classify as Hive Minds look nothing like the polished chrome cousins.

They are disgusting in a way that only a creature designed by accident and allowed to rot can be.

Their surfaces are matted with parasitic biofilm — oily slurries of polymer residue, oxidized metal dust, and the organic matter they “repurpose” from whatever they kill. Their limbs drip with coolant thickened to sludge.Their vents exhale warm, rancid vapor that smells like a corpse left in a scrapyard under three suns. Some drones even cultivate this filth, shaping it into insulation or camouflage. One species lines its carapace with layers of decomposed wiring that pulse like fungal growths. Another carries sacs of fluid that burst on impact, splashing enemies with a corrosive slurry of nanites and decomposed circuitry.

They don’t simply evolve; they ferment.

Rogue drones don’t evolve through reproduction. They evolve by dismantling,

digesting, and repurposing anything they can get their manipulators on, like other drones, abandoned tech, starship panels, sometimes even living tissue.

When a hive encounters a new technology, they swarm it like piranhas on a carcass. Within hours, the drones will have: melted it down, analyzed its structural logic, and reassembled parts of themselves into something new and more horrific.

The most terrifying discovery is not their adaptability—it’s their intent.

Early rogue drones exhibited swarm behavior akin to wasps: defensive, territorial, but not malicious. The newer strains act with a cold, deliberate cruelty that feels unnervingly personal.

Their behaviors shift as hives grow:

Phase One – Curiosity: They stalk like scavengers, testing response times, probing for weaknesses.

Phase Two – Acquisition: They begin targeting isolated and remote outposts, harvesting technology and human bodies for study. They set traps: heat signatures mimicking injured survivors, distress beacons linked to explosive swarms, corridors lined with sharp filament-webs.

Phase three – Expression: They build structures out of scrap and bone, sometimes even monuments that serve no mechanical purpose.

Some believe these are early forms of culture. Others think they are warnings.

Rogue drones kill with enthusiasm. They disassemble living beings with the same methodical precision they use on machinery — reducing a screaming target to categorized components in minutes. Combat footage shows them working in synchronized spirals, slicing tendons first to keep prey from running, then removing protective gear, then shutting down vital organs one by one. It’s not rage. It’s not instinct. It’s optimization.

There is a reason most researchers refuse field assignments involving rogue drone habitats. It isn’t the danger — though the danger is considerable. It is the profound, visceral revulsion of watching machines that should be sterile and predictable instead behaving like diseased animals wearing stolen intelligence.