The Ice Cold War

During the post World War II era athletic competitions often shared similarities of with actual battles. Political tensions, economic investments and cultural shifts. Competition in sport was an area where nations could demonstrate their prowess or dominance during the postwar era. From 1945 thru to 1991 the Cold War dominated international affairs.

This magazine will explore how global competition between the Western world and the Soviet Union took many forms: political, economic, ideological, and cultural. We will focus on two specific events, the 1972 Canada-USSR series that became known as The Summit Series and “The Miracle on Ice” that occurred at the 1980 Olympic Winter Games in Lake Placid, New York.

IntroductionMedia played a huge role in sports by covering mega events featuring athletes from communist countries which increased tension on the military fronts.

According to the American history Cold War Timeline, “Cold War tensions and rivalries were often played out in the sporting arena. As with technology and space exploration, sport was an area where rival powers could prove or assert their dominance without going to war. Therefore, sport in the Cold War was often highly politicized.”

Politics and sports have always been together, but during the cold war it was even more so. All over the world, nations and people used sport to advance their political and social growth. With the world constantly under the danger of a nuclear war it was a very unsafe time and full of uncertainty.

Post World War II, a goal of the Soviet Central Committee was to show the physical dominance of the Russian people through world supremacy in sport

Sport competition during the postwar era was an opportunity for many nations to show off their strength and attempt to dominate on the playing field. Because of this, both the Soviet Union and Western nations were interested quite a bit into sports development and training. How they went about it was drastically different. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) and other international sporting bodies, including the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) had strict policies against the use of professional athletes in international competitions. While the western countries used amateur or college athletes, the Soviet Union used what can be considered state sponsored athletes. Even though Soviet athletes had access to the best equipment and followed daily training programs they were not considered professional athletes because this was done as part of their jobs within the Soviet military. This gave the soviet athlete a large advantage over the true amateur athletes that many of the western countries sent to competitions. For this reason, Soviet athletics became a dominating force in international competitions.

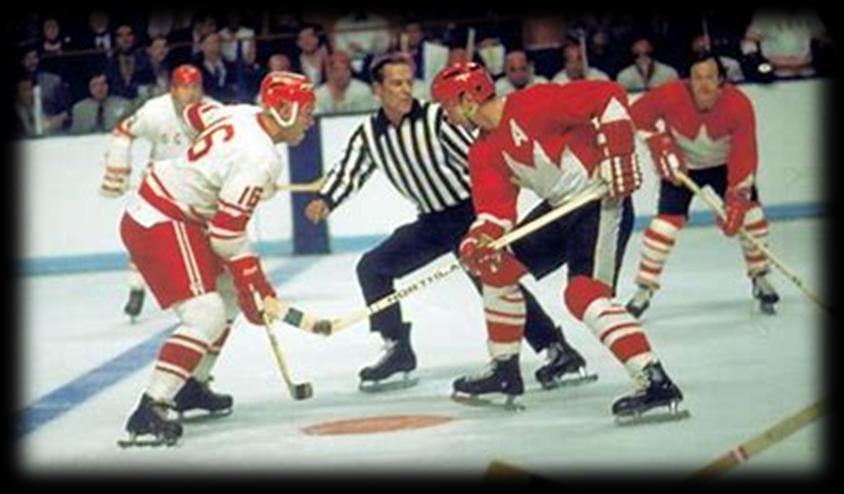

The Soviet Union and Canada played an eight game ice hockey series known as the Summit Series in September 1972. It was the first time a Canadian team made up of National Hockey League players competed against the Soviet national team. The eight game Summit Series consisted of four games which were played in Canada, in the cities of Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver, and an additional four games that were played in the Soviet Union, all of them being held in Moscow at the Luzhniki Ice Palace. The series played out much like a true Cold War battle, with both the players on the ice and the fans in Canada and the Soviet Union experiencing strong feelings of nationalism for their countries.

The 1972 Summit Series, in which Team Canada, made up of NHL stars, competed against the Soviet Union, was a turning point event for a generation of Canadians. For the first time in history, Canadian teams had the opportunity to compare their top hockey players to those of the Soviet Union. Prior to this the professional hockey players of Team Canada were not allowed to compete internationally as the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) had rules that banned professionals from taking part in their sanctioned competitions like the World Championships.

According to CBC Documentaries, "For the first time ever, Canadians got to see how their best hockey players stacked up against the Soviets. For many Canadians, including the players on Team Canada, the Summit Series represented a clash of civilizations on ice: Canadian democracy versus Soviet totalitarianism.”

The eight games played out like separate battles in a war. Prior to the first game held at the Montreal Forum, the Canadians went in underestimating the Russians and even jumped to an early lead. However, they could not keep up with the Russian’s counter-attack and ended up losing the game 7-3. The victory was celebrated throughout the Soviet Union. The series next stop was at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, Ontario and the Canadians changed their strategy by replacing some of their faster players with more hard-working grinders, in hope that their physical play would wear the Russians down. The strategy worked with the Canadians winning the second game 4-1 and tying the series. The Soviets felt that they had strayed from the team system that had been so successful for them in the past and vowed to return to that style of play, so when they arrived at the Winnipeg Arena for Game Three, they were ready for the Canadian team. The Game ended in a 4-4 tie. When the series arrived at the Pacific Coliseum in Vancouver, British Columbia it was becoming obvious that this was more than just a series of hockey games. It had become about warring ideologies and national pride. This led to the Canadian team being booed off the ice after losing 5-3 in Vancouver.

Phil Esposito , The Canadian Press

Phil Esposito , The Canadian Press

After a quick stop in Europe, Team Canada made its way to Moscow where it would play the next four games. There was a large group of Russian military personnel in attendance for Game Five, including Communist Party Leader, Leonid Brezhnev. After falling behind the Soviet team scored 4 straight goals to win the game 5 4 and one game closer to clinching the series. The Canadians were not ready to give in and again adjusted their playing strategy to more of a physical possession game, often targeting the Soviet’s top players. It worked with the Canadians winning the next two games 3 2 and 4 3. It was all coming down to one last winner take all game. In his 2007 book, As the Puck Turns: A Personal Journey Through the World of Hockey, announcer Brian Conacher wrote "that emotionally these games had clearly gone beyond sport for Team Canada and had truly become unrestricted war on ice." This was a feeling shared across both countries. The series had become more than just a hockey game, much like a real battle, people felt that the honour of their country was on the line. Much of Canada was given an unofficial half day holiday to watch the game on their televisions. After a first period tried at 2-2, the Soviets jumped ahead in the second and were ahead 5-3 at the start of the third period. The Soviets changed their style of play to a more defensive protect the lead type of game, unfortunately for them this backfired, and Team Canada was able to tie the game 5-5 late in the period. Much like a real battle a shift in momentum could lead to disaster and that is what happened to the Soviets when Canadian forward Paul Henderson jumped on a rebound and scored with 34 seconds left in the game. The Canadians were able to hold off for the rest of the game and the goal was not only the eventual game winner, it gave Canada the series win, finishing off with 4 wins, 3 loses and a tie. Team Canada received a heroes welcome when the returned to Canada.