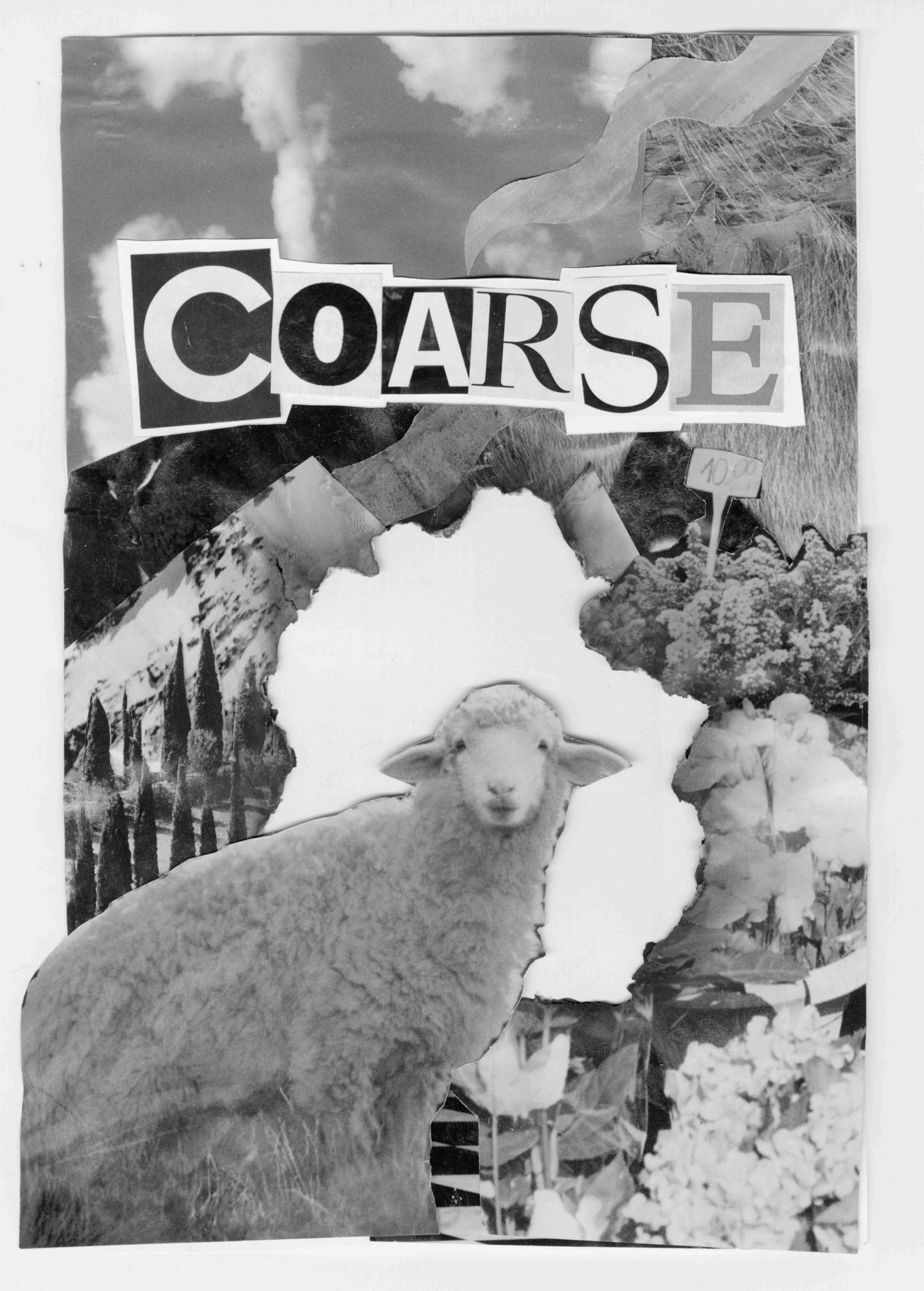

spring 2024

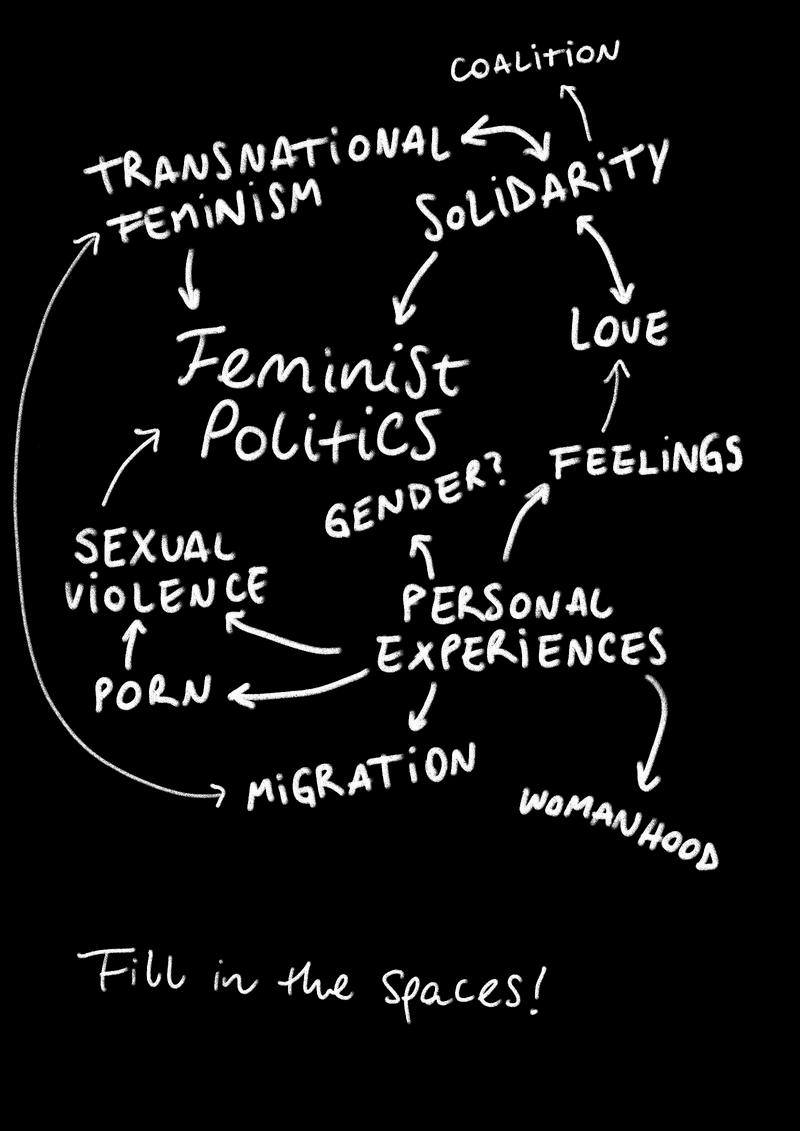

With this edition of COARSE, my main concernasafounderistomakeitasustainable project, which is why the team has expanded, and why we chose to work under the topic of ‘feminist politics’ for this issue It might sound too self-evident: isn’t all feminism about politics?

Well, it is and it isn’t. Some feminism is definitely about politics. It prods at our relationships,atourcommonsense,andatour worldviews and asks: Isn’t this kind of messed up? Isn’t this unfair? Isn’t this a contradiction? This kind of feminism is not easy to ignore. It breaks down the very fabric of existence by pullingslowlyatthethreadsandbeggingusto accept that a better world is possible.That is what I want to highlight as feminist politics: those acts and practices of solidarity that aim to build networks of sustainability, mutuality, sentiment and safety for everyone to live with dignity, which is achieved by observing the needs of those most disenfranchised in our communities first In short, a feminism that is fiercelycommittedtothefuture

On the other hand, there are definitely apolitical feminisms These are the corporate, and sincerely empty, attempts at selfaggrandizement, awareness without systemic change,andhierarchy.Thefeminismthatsees women in positions of power in the government and celebrates as the United States supports yet another genocide. The kindoffeminismthatpreachesselfcareasafix of symptoms where there is no effort to address the underlying problems. The kind of feminism that sees itself making an effort and stops for congratulations, never making it to the end goal, or to meet whoever is waving at thesidelines.

Seeing all of this unfolding as we witness someofthelargesttragediesourworldhasto offer,itfeelsevenmoreimportanttoestablish ourselvesasfeminists.Notonlythat,toground ourselves in the soil of a feminism that feels coarse.I’mnotagainstpoliticsthatfeelsofter.I think it’s important to have a time and place where one can engage with others in joyful, pleasurable, and loving manners Feminist thinkers have demonstrated time and time again that this is indeed necessary, and valuable Inaway,acoarsefeminismshouldn’t takespaceawayfromthiskindoffeeling

But the focus is different; the case for a coarse feminism points to a different need. This is the need to stop being so satisfied with our own takes, our own actions, our own ways of engaging with each other. We need to be shaken off the ground by feminism, to be put in difficult positions, to shift in our seats at the discomfort. If there is so much to change about the world, then we do not only need a feminism that can help us change it, we need a feminism that can change us. I hope COARSE changes somethingforyou.

P.S. As a final note, I’d like to offer you a triggerwarning.ThiseditionofCOARSE contains discussions on sexual assault, porn, solidarity, feminicide and genocide, love, and feminism.

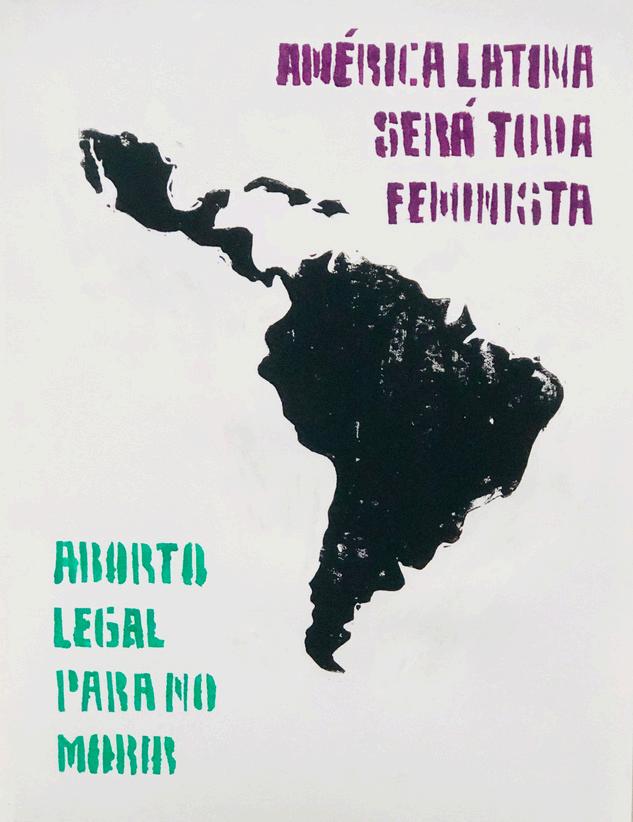

Print Series by Valeria Obregón Díaz

My first semester at SLU was in the Fall of 2020, and because of the pandemic and embassies being closed I couldn't get my student visa on time, and had to do my first semester remotely I took an art course called "Thinking Outside the Print Studio" that semester This class invited us all to be resourceful and try to make prints with the materials wehadaroundus TakingthisclassallthewayfromMexicoallowedmetoexploremyidentity as a feminist, and it was my first opportunity to share what it meant for me to be a woman in LatinAmericawiththeSLUcommunity

“América Latina será toda Feminista”

[Latin America Will All Be Feminist].

October 2020.

Mixed media print in linocut and stencil.

The text in this print translates to Latin America will all be Feminist, LegalAbortiontonotdie.

The year 2020 was an important year for the feminist fight in Mexico, asitwasayearwherethenumberof people at the International Women's Day March in Mexico City exceeded previousnumbersandreceivedalot of media coverage. The intention behindthisprintwastoexpresshow the feminist movement in Latin America is growing every year, and to share the dream that one day, everyone will be a feminist. The part about legalizing abortion calls attention to the urgency of the demand and how every day that passes without legalizing it results in hundreds of women dying Only one year after I made the print in 2021, abortion was decriminalized in Mexico, which was a big step in the right direction, and several states in the country have legalized it since then We are currently still fighting foritslegalizationatafederallevel

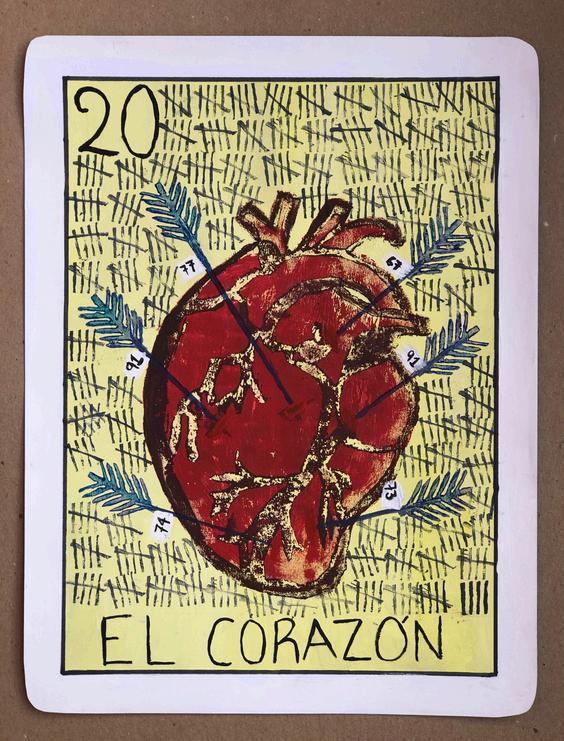

“Corazón feminicida”

[Femicide Heart]. November 2020. Mixed media print

This was my final piece, where I explored different techniques learned throughout the course, including hand-carved stamps in different materials. Corazon Feminicida is a memorial to all the women who were murderedduringthefirsthalfof2020 Onlyinthefirst six months of 2020, 549 femicides took place in Mexico. This means 549 women were killed because of their gender. This piece is inspired by the card of theheartfromthefamousMexicangame"LaLoteria", which initially represents pain. Instead of adding only one arrow as the original card, I decided to add six in total torepresent eachmonthof thisyear Thelabels oneacharrowrepresentthenumberoffemicidesper month starting from left (January) to right. In the background, I added a tally mark count to represent the total number. Since 2020 when I created this piece, according to the Department of Security and CivilProtectioninMexico,3286women'sdeathshave beencategorizedasfemicides.Sadly,thispieceisstill relevant today, four years later, which is why I am sharing it and bringing attention to the still pressing issue.

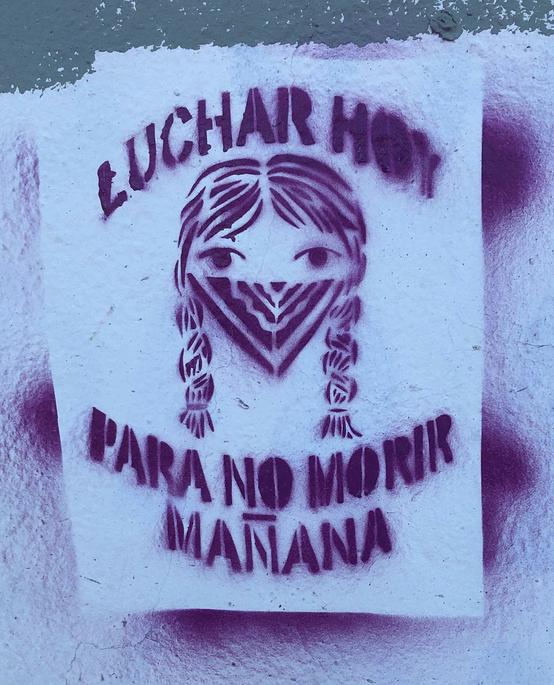

“Luchar hoy para no morir mañana”

[Fight Today, To Not Die Tomorrow]. October 2020.

Stencil spray paint.

I made this piece of art during the unit on stencils. Continuing with the theme of exploring my relationship withfeminism,IknewIwantedtosharethisdesignbeyond my class with my local community in my hometown, Tijuana.Iwasabletoputtendifferentspraypaintsaround my neighborhood. The decision behind making this art piece public was bringing attention to the urgency of the fightbecauseitisamatteroflifeanddeath.Byputtingthe designinthestreet,Ihopedtomakepeoplereflectonthe feminist fight and what the absence of this fight could meantosomanywomen,whichcouldrangefrommicroaggressionstodeath.

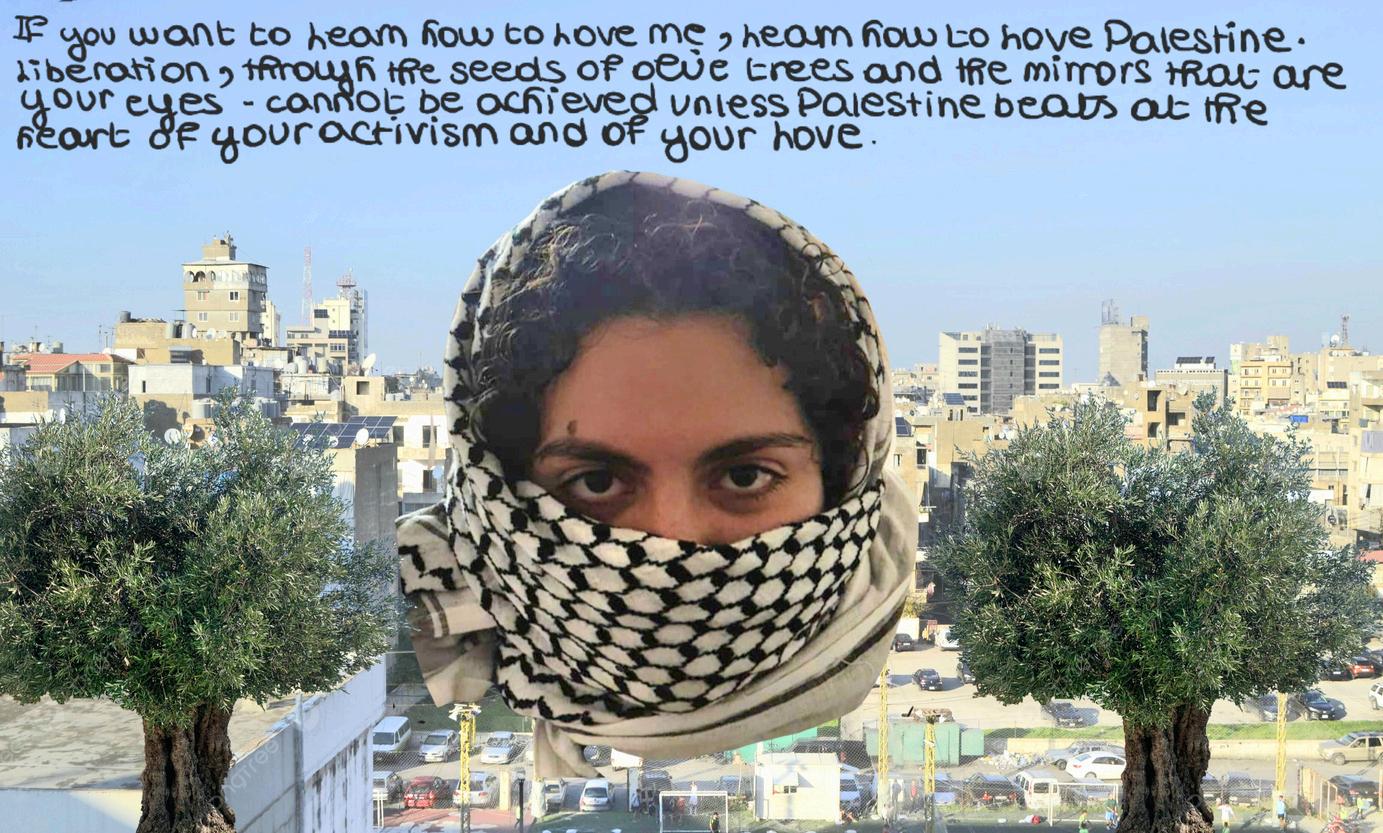

Digital collage and poem by

Karni Keushgerian

Heartachelooksdifferentforeveryone,granted.

Butwhatdoesheartachelooklikeforthoseintheworldwhoselivesarehalted,lost,andfrozen acrossborders,andacrosstheindefinitemarginsofwhatpeoplecall“home?”Whenone’s fundamentalideasofhomeandlovearefossilizedinmemoriesthatoncewereandarenow lost,wheredoesonelookforcomfortandforpeace?

Often,IwonderifIamcapableoflovingpeoplewhoseexperiencesdonotgivethemaccessto understanding my life and my region beyond what is on the screens of the West, about the “orient.”

Whenloveisnotradicalenoughtobattlethebombsthatdroponmychildhoodroom,likeakite makingitswaytogreetme,Irefusetowelcomeit.Theword“solidarity”disguisesitselfasthat kiteanddancesinthewindremindingmethatsomeonemightslightly,artificially,andbarely feelthewhirlwindoftheBeirutPortblastbutwillneverseektoreachitsstringsbeneaththe rubbleandpullmeout.

Donotdilutetheloveyouareaskedforbycharacterizingitasbeingsomethingyoucannot offer.Isaythisbecausethedisorientationandthedisconnectionyoufeeliscausedbyyour fundamentalunderstandingofnationalism,globality,belonging,citizenship,andhumanity Allof whichIneedyoutoviolentlyanddisruptivelyquestion.

Tolovemeislikebeinginaprotest:Loud,tireless,andvisible.

Often,Iwonderifitisfairtoaskanothertowaitwhenwhatiscomingnextissounsure. Often,IwonderifIamcapableofbeingandstayinginlovewithsomeonewho,withinthe systemthatkeepsclawingatourhumanity,livesintheirpowerasthoughitisacloudfloating above;restingonthebedofpowerthatgivesthemthegiftsofmobility,stability,consistency, andlove.

Asanimmigrant,myfirstheartbreakwasmarkedwhenIlefthomeforthefirsttime.And, throughouttheyears,Beirut,myfirstlover,hasmadesuretoalwaysinjectherselfinthewaysI lookatmyotherlovers Forwhenoneonlyhasmemoriesofaplacethatnolongerexists,those feelingstransformintoaneverlastingheartbreak.

ThelasttimeIfellinlove,mylovercouldnotwaitforme Itwouldtakemetoolongtofindmy waytoaplaceofconsistency,tofindmywaybacktothem.Icouldlovethemintimebutnotin space.And,inthemomentofthisrealization,IturnedaroundtolookatBeirut.Thecurseofher lovemakingitsway,yetagain,andcoatingmyheartinalayerofunreachable,unseeablemist

Tothis,Iwonderhowoneissupposedtoloveandbelovedwhentheritualofwaitingtakesup somuchofourspacesonthisEarth:Waitingforthewartoend,waitingtoseeafriend,waiting togetabetterjob,waitingtofinishadegree,waitingtohaveenoughenergytomakeameal... waitingtolearntolove.

Mylastloveraskedmewhatitmeantto“build”loveknowingthattimewouldneverbepresent andwilling.ThankstotheconversationsIhavehadwithmycurrentgodoftime,mylegalstatusin thecountrythatbombsmyhome,Ihaverealizedthatthereisnosuchthingastimebeingagainst you.However,itistruethatitskissesleavedifferentmarksonthecheeksofmany.Timewill alwaysbeonyoursidebutnoteveryonewillunderstandyourrelationshiptoit.Because,when minutesrunout,somewillreturntotheirborderedhaven You,ontheotherhand,willreturnto anindefinitelylongandlonelywalkthroughthemargins

Often,Iwonder,isitfairtoasksomeoneyoulovetoalwaysbereadytobattleagainstasystem thatmighttieyourhands,whenyousaywordsthatnotmanywillwanttohear?Wordssuchas

From The River,

To The Sea

Becausewhileyoumakeupyourmindonwhatisfairandwhatisnot,Isitonthefloorofmy roomwithmyphonegrippedinmyhandandtearsrunningdownmycheeks. IcannotbreatheasIseemypeoplegothroughagenocide. So,frankly,Inolongercareaboutmyimmigrantheartbreak,andInolongercareifyouare willingtowaitornot.Ihavemanythingstodo,andIamtired.

Lovemepolitically,ordonotlovemeatall

“

Photo series by Agata

Faran

Artist Statement by Allison House

April 2024

In high school – with my first couple boyfriends – I was a cool girl. “You can watch porn!” “I watch porn, it’s normal.” “These are normal feelings; it doesn’t make me insecure that you watch porn.” “What is your favorite kindofporn?”

I studied, I learned, and I mimicked the behavior.At15,“youcanchokeme.”At16,“you can bruise me.” At 17, “you can pull my hair.” It made me feel sexy. It made me feel desirable. Butthen,Ibecameanadult.

My sister just turned sixteen She is a child in myeyes Whywouldanyonewanttochoke,hit, andpullonachild?Whywouldachildfindthis desirable? Was I a child when I was recreating thosevideos?Whatisporndoingtous?

Most young boys that I knew watched porn They had unrestricted access to it, and their guardianswereoftennonethewiser.Itwasnot justathome;itwasatschool,andathangouts, andatpractices.Asayoungadultorteenager, you cannot escape it. Porn was force fed to me. Itwasnotjustme,asawoman,whowasforce fed porn. Many boys have a nonconsensual first experience with porn – told by both personal stories and studies (Grueter, 2023). Thefirsttimeyouwatchedpornography,wasit being shown to you or did you seek it out on your own? As a boy, if porn is forced on you, youlearnthatsomethingscanbeforced.You are told that it is normal, it is healthy, that you areaman,andyouwillenjoyit

Not only will you enjoy it, but you will learn from it (Grueter, 2023) It will teach you You will study and fantasize about recreating the scenes He is in charge He takes – often a younggirl–andHeshowsherwhatHecando Shebegstobebrutalized Shebegstobehurt ShebegsforHimtotakeandtakeandtake.

Youexpectthistobethecase.Youfindagirl andyoutake.Youtakeherbreath,youtakeher hair in your hand, you take her throat in your grip. Many times, you will take her voice. She might not say she feels violated or abused or raped.Shewantedtotryit,too.Butjustasporn

hastaughtyoutotake,pornhastaughtherto please.

Pornhastaughtherthatthisisnormalinthe same way porn taught you that it was normal. Your willingness to take reinforces this idea. She must enjoy pain and brutalization. She learns to moan when it hurts, to ask for the things she sees in the films. She will learn that it’swhatyouwant.

Seriously ask yourself: Is it what you want? Does causing pain turn you on? Does infantilization, the naivete of a virgin make you hard? Or were you taught that? There is a difference between kinks and fetishes and desires,andlearnedbehaviors

How much are we taught from porn and how much are our own desires? If we can be convinced to follow trends in clothes and hair and food, what makes you think that your sex lifeisanydifferent?

From, Agirlwhohashadsex

Excerpt from John Greuter’s “The Positive and Negative Impacts of Exposure to Pornography during Male Adolescence, and Implications on Sexual Education Policies” from a female subject withamale,pornographyconsumingpartner.

“[The position is] with me laying down on my stomach and him laying down on top of me. It often, um, I know it is kind of extreme, but it feels like rape. Like, I don’t know [laughs]. I just feel like I can’t move. I feel like even if he’s not being rough or anything on me, I just feel like stuffed, like it’s not right. I feel like that’s something that – it just doesn’t – it just doesn’t feel like ... it’s not comfortable. Yeah, it doesn’t feel like that’s what couples do [laughs]. It feels likeI’mbeingforced.Idon’tlikeit.”

Source: JohnGreuter,StephanieSitnick,andBeatrice Turenne.2023.“ThePositiveandNegative ImpactsofExposuretoPornographyduringMale Adolescence,andImplicationson SexualEducationPolicies,”

Essay by Alice Yuchang Zhang

When I think about you, I think about love; along with all the most beautiful things this worldcanprovide Ilovethemdeeply,because they are loved by you (Sappho, Fragment 16) What a divine portrait of lovingness, and of course, this is coming from a woman’s perspective, and from her desire to love another woman. It was not coming from just any woman, but from one of the greatest lyric poets in history, the “Tenth Muse”, “The Poetess”,SapphoofLesbos.

Whatisthemostbeautifulthingonthisdark earth? Sappho expressed that men claimed it to be a marching of horses, ships, or armies; but to her, it was what her love interest loved. “Themostbeautifulthing…Isay,itiswhatyou love.” (Sappho, Fragment 16). She put her on the crown of love, giving her the power equivalent to a Goddess, because what a God loves is something divine and beautiful. Sappho recognized that her love’s heart is the originofbeauty Itisnotevenloveitselfthatis most beautiful, but it is what the loved ones love that has the power to define beauty, an intimate and passionate claim Sappho was willing to shift and adjust her own morals and judgments according to what the love of her life desires, because she had full trust and adored the heart of her loved one to give her thispoweroflove,thepowertodefinebeauty. Sheofferedacceptanceandwillingnesstosee the world through her love’s eyes and to love whatsheloved.

In a patriarchal world, what men worship is the resemblance of power, but what Sappho worships is beauty itself, and it is represented by the woman she loved. This world, from ancientGreecetothemodernday,putthe

loveforpoweroveranythingelse,andpraised power to be the only thing worth pursuing after

Instead of love for power, Sappho justified the power of love.

According to this woman poet, the masculine narrative has tried to use love to justify violence and war, treating women as either a trophyorapossession.Yet,intheend,women always ended up taking the blame for the consequences of war and destruction. Helen, the woman behind the great Trojan War, was puttothecourtofblamewhentwomenwere fighting over her love. However, Helen’s own motivation and reason were always left out of narratives from male authors. In Homer’s Odyssey,hespentpagesexplaininghowHelen is the reason behind the Trojan War, while barelylettingherspeakforherself,evenwhen Odysseusmether.Noonetriedtolookbehind herownwillanddesirestoleaveherhomeand everythingbehindinthenameoflove Shewas condemned, blamed, or neglected in history forgoingafterwhatsheloved TheTrojanWar was allegedly started in the name of love, yet thecommonnarrativesomehowleavesoutthe only part where love takes initiative, because behind the heart of this love, was a woman. Sappho not only saw the irony in this, but she also provided understanding and compassion forHelen.

Sappho’scompassionforHelenissignificant inhistorybecausesheattemptedtojustifythis most criticized woman in many historical literaryworks.ShenoticedhowHelennever

got a stage to express and defend herself Instead, Helen was only given the recognition of “the most beautiful woman” of her time, as herbeautywaswhatstartedthewar–butnot men’sownarrogance;menfellinlovewithher physicalattractiveness,butnothermindorher heart.Then,aman’sloveseemssosuperficial, violent, and dangerous. They claim to love in order to possess, to show power and dominance. If they cannot get the love they desire, they would cast a war at the cost of sacrificing other men’s lives to take back what is lost. The love they show lacks emotion and understanding Onthecontrary,Sappho’slove was gentle and respectful. She loved not for thebeautyontheoutside,butmoreforwhata beautifulheartwasattractedto.

She did not praise love itself, but preached for her object of love, and for everything covered by it. She imagined Helen running away, putting her responsibility aside. At this moment when she was after love, she was finally her own individual, free from the rest of theworld.AccordingtoSappho,Helen’sloveis worth praising because her love involved sacrificing. She was willing to give up everythingunderherroyalnameandfledfrom comfort just to be with the man she loved. (Sappho, Fragment 16). To be loved by a woman, it is an accepting and gentle love out of appreciation; to love what she loved because she believed in the power of beauty. Tolovewhatshewasbecauseshebelievedin the power of love For beauty herself should alsoloveandattractotherfinethingsandthat is enough reason to justify and believe in love ItisnotthecasethatSapphoiscalmandloving becauseshereceivedtheloveback Similarto Menelaus losing Helen, Sappho lost her love, Anaktoria. “Let her astray,” (Fragment 16). Sappho keeping her promise to recognize what her lover loves is more divine than anything else. She let Anaktoria go to pursue herownhappinessandlovebecausesheknew nothing would compare to what a beautiful heartdesires.AnaktoriawasgoneandSappho wasstilllongingforher,yetthatshouldnotbe the reason to force her to stay, even in the name of love Sappho is letting her beloved carry herself away, along with her love and blessing, because to love is to sacrifice and to let the woman you loved go after what she is lovingnow.However,driftingapartdoesnot

take away the love that was once shared betweenthem.

Through the metaphor of Helen, Sappho set herselfandherlovefree.Thesethreewomen’s paths intertwined at this very moment as they allcarriedthedesiretoloveandtobeloved,as well as the burden of not being able to be loved by what they loved. Maybe this poem is also a reminder for Sappho herself, just like HelenandAnaktoria.Sapphostillhadachoice to move forward with the reminder that she waswhatherloveronceloved,whichmadeher somethingdivineandbeautifulaswell.

In a male predominant world, Sappho’s narrations for love were evolutional and inspiring Insteadofbeingtheobjectofloveas a woman, Sappho took the pen and became a powerfulvoicetoexpressthisbeautifulfeeling. She truly worshiped women and treated women as divine beings themselves, giving them power by giving them love. Femininity tookthestageinhistory,showingthesoftside of love in comparison with men’s aggression Men choose war while women choose love. Sappho’s queer representation in history serves as a powerful encouragement for the modern-day revolution and feminist movement. Without her and her words, many of us would be lost and blinded by the blandness and sterileness of the patriarchal hetero-normativewayofexpressinglove.

Sappho reminded us how accepting and gentle it can be to love and to be loved by awoman.

Source: SapphoandStanleyLombardo.Sappho:Poems andFragments Hackett,2002

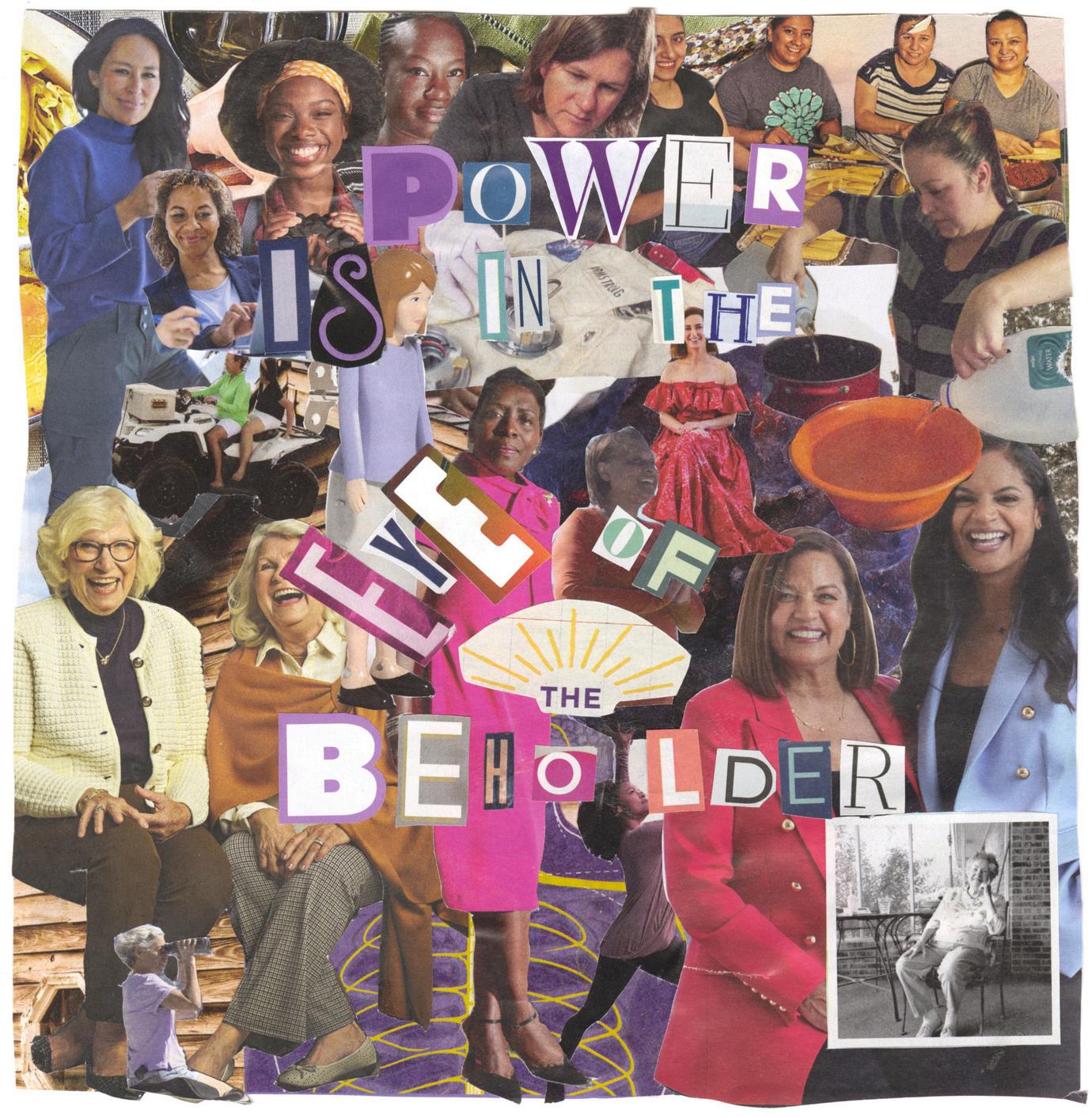

By Renate Jakobsen

March 2024.

Collage.

Where men are more likely to be assigned leadership attributes such as analytical, competent, and dependable, women are more likely to be described as scattered, indecisive, and compassionate; all words that are usedtomakethemlesspowerful.

Studies show that in mixed gender groups, men speak 70% of the time (Chemaly, 2015). Women are rarely viewed as the most powerful, influential, or relevant speakers, yet they are stereotyped as being too talkative (Doyle, 2014) A study of US senators shows that men who spoke more often, showed a strong relationship between power and volubility, while women who did the same did not show the same relationship (Brescoll,, 2011) Men who talk more in professional settings are likely to receive a proportional ncrease in perceived power, while women who do the same are not Women are not only less likely to be in positions of power, but when they are, they are viewed differently The perspective of women in positions of power is evidently biased, as shown on websites like Rate My Professor. Terms such as “brilliant” or “intelligent” appear in men’s reviews, according to research, while words like “annoying”, “harsh” or “unfair” were more common in reviews of women (MacNell, et. Al., 2015). Women are constantly in a fight to be perceived as serious and respectable due to gendered prejudices constantly putting them at a disadvantage.

For men, power is something they are given. For women, power is something we must take. Power is not something unbiased, but something subject to the views and biases of the viewer.

Power is in the eye of the beholder.

Sources: Brescoll, V. L., 2011, Who Takes the Floor and Why: Gender, Power, and Volubility in Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 56(4), 622-641. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839212439994

Chemaly, S., 2015, In Mixed Gender Groups, Can You Guess Who Talks The Most? Role Reboot, http://www.rolereboot.org/culture-and-politics/details/2015-10-in-mixed- gender-groups-can-you-guess-who-talks-themost/

Doyle, J. E. S., 2014, The ‘Feminized Society’ Myth. In These Times. https://inthesetimes.com/article/our-feminized-society Jaschik, S., 2015, Rate my word choice. Inside higher ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/02/09/new-analysis-rate-my-professors- finds-patterns-words-used-describemen-and-women

MacNell, L., Driscoll, A., Hunt, A.N., 2015, What’s in a Name: Exposing Gender Bias in Student Ratings of Teaching. Innov High Educ 40, 291–303 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9313-4

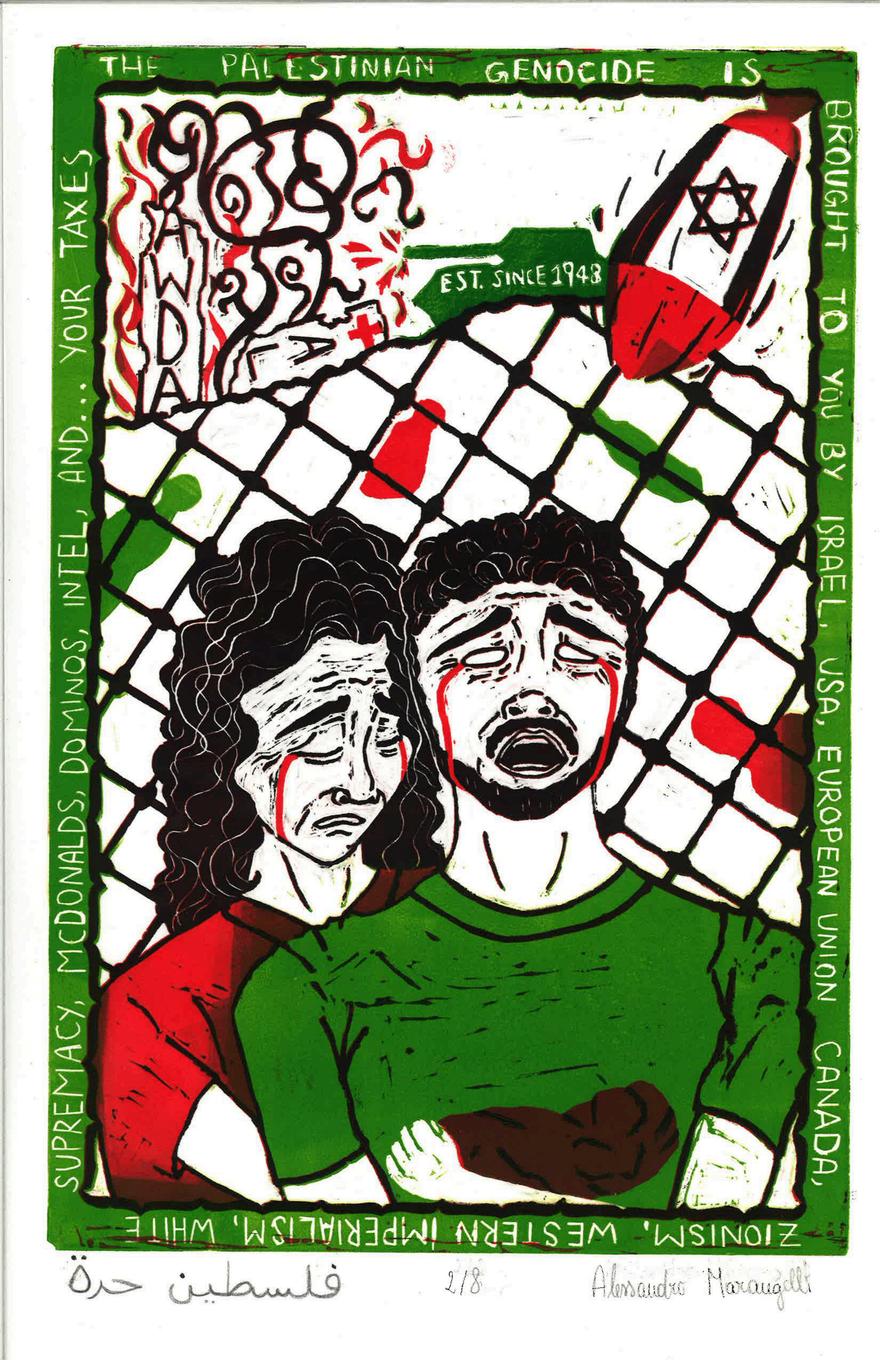

By Alessandro Marangelli

[Free Palestine]. March 2024. Linocut print.

Millionsofpeopleacrosstheworldarecalling forafreePalestine.Freefromcolonialism.Free from Western imperialism Free from Zionism Free from all the intersecting oppressions Palestinians endure on a daily basis As I write this statement, it is hard to convey a message thattriestostaytruetotheresistanceandthe horrors that have been unfolding since October 7th, since the Nakba in 1948 Rather, sinceBritishcolonialismbeforethen.

Palestinian and non-Palestinian activists, scholars, parents, students, workers and countless more advocate for Palestine as also a feminist struggle, and I too believe it to be one. People on the ground, as well as NGOs and international organizations have been documenting the abuses that the genocidal, western-backed Zionist state of Israel has beencommitting.TheliberationofPalestineis a feminist struggle because Zionism, like all forms of injustice and persecution, oppresses peopleinintersectionalways,suchasthrough pink-washing genocide. Israel is proven to target reproductive rights by intentionally forcingpregnantpeopletogivebirthatcheck points, forcibly sterilizing women, and forcing Palestinians in Gaza into living in a mass concentration camp (Eid, 2023), sexualized torture (ie, rape, denigration, stripping, etc) Yet, until Palestinians are treated with humanity, or even as citizens, Palestinian liberation struggles will continue to be a feminist struggle. Until we stop ignoring Palestinian men as if their suffering doesn’t count, it will be a Feminist struggle. Until Palestiniansarenotreturnedtherightstoselfdetermination, Palestinian liberation will be a Feministstruggle.UntilallPalestiniansarefree, it will be a Feminist struggle. Without a free Palestine, there cannot be free women, men andnon-binarypeople.

Writing this statement has been hard as I reflectonmygeopoliticalpositioninallofthis. As I wonder what I can do amidst all the lies spreadbytheUS,myowngovernment,and

mass media, I ground myself through the solidarity,empathy,andcompassionthatIsee around the world and experience within my own community Still, the knowledge that billionsoftaxdollarsarebeingsenttoIsraelto carry on its abominations also makes me question my actions, together with all the falsehoodthatIfeelIhavetodebunk Thereis moretothisthanwhatisbeingsaid,especially in understanding broader political economic structures; like the deals that Israel has with fossil fuel companies on the reservoirs of naturalgasintheGazaSea.

Makingthepiecenotonlytookavastamount oftimebecauseitwasmysecondlinocutprint and first reduction piece, but mostly because of the emotional energy it required. The Palestinian struggle has been closer to my heart than many others. I do not know if it is because of the geographical proximity, or the similarity between Palestinian towns and hills and my home, or because of all of this and more. Every day I think about Palestine, and every time I worked on this piece, I thought more about it At times it felt too overwhelming, forcing me to stop the carving In the last session, as I was writing the title ةﺮﺣ ﻦﻴﻄﺴﻠﻓ on the prints, I was feeling very emotionaltoseeitallcometogether AsIwas listening to shuffled music from my playlist of liked tracks, the song Rossa Palestina by MahimAhmedstartedplayingonmyphone.At thatmoment,Ialmostburstintotears.

Source: Eid,H.(2023,December30).OntheGaza ‘shoah’andthe‘banalityofevil.’AlJazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/12/30/o n-the-gaza-shoah-and-the-banality-of

Essay by Nach Insaurralde

Introduction

Isitatthetableinfrontofmylaptopwriting this and I get distracted by the inundating presence of my phone. I turn to social media forsomerelieffromtheburdenofthinkingand I see Gaza. Bisan, a young storyteller turned journalist, tells us about the current genocide against the Palestinians. She speaks of her people being bombed, about losing hope in her own survival. It creates a puncture in my heart, a rush of anguish in my body. I turn my phoneoff,yettheanguishremains

Idon’twanttoforget,but evenifIwantedto,mybody wouldn’t.Imaynotknowthe pain,butIwillrememberit.

AsIenvisionwhatthisessayisgoingtolook like, I feel the need to establish a couple of remarks on my own positionality. My name is Ignacio Insaurralde, and I come from José C. Paz, Argentina, one of the most dangerous cities in the country. My parents, and myself, are working class, and I identify as South Americanwhite,locatingmyselfintheprivilege of my skin color in my own native town and in diverse steps of subjugation of international racism and ethnocentrism at the same time. I am also openly gay, and visibly androgynous, non-binary. My home country has been and continues to be exploited and looted by imperial powers of the Global North, which is where I live My unique position as someone whohaslivedmostoftheirlifeintheGlobal

South yet speaks the language of the colonizer,livesatthehomeoftheempire,and moves through different axis of power and subjugation with certain fluidity has led me to develop a very specific kind of solidarity, one that is based on feelings. The contradiction of the different interstices that make up my positionality creates contradictory feelings, which in turn nurture a complex, yet fertile groundinwhichthefruitsofsolidaritygrow.

After a discussion on the work of Kaplan, feminist theory professor Clare Hemmings arguedthatsometimesempathyinthecontext of feminism turns to a “cannibalization of the othermasqueradingascare”(Hemmings152) I wanttoavoidthis Sobeforewritingthis,Iwant to be clear with both myself and the reader: this essay will not be about Gazans It will be about me, and about how what I feel about Palestine is rooted in my own history, my own feelings, and my own experience of structural oppression and power. I will, from the honesty of my knowledge and my feelings, mobilize conceptspertinenttomemoryworkandaffect theory to answer the question: How can local affective memory practices sustain transnational anti-imperialist solidarity with Palestine?

This will be done through an exploration of emotion, touching on concepts such as wonder, perplexity, affective solidarity, and sorrow.Iexplorehowmyexperienceofhistory and my own positionality connect me with these feelings, and how I reach solidarity through them, arriving at a collective and pluralistsolidarityrootedinemotion

This essay will not, however, attempt to outlinewaystoactuponthatsolidarity.

That isapath each of us must labor for ourselves.

The initial question to answer when introducing affect theory is: Why care? This is led by the assumption that reason and emotionsareseparate,andthatreasonismore valuable,hence,oneshouldn’tbepayingmuch attentiontofeelings.Thisis,however,nottrue. Feelings permeate every single choice we make, and we experience them all the time. In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, critical feministtheoristSaraAhmedbreaksdownthe basis of this assumption. She argues that “focusingonemotionsasmediatedratherthan immediate reminds us that knowledge cannot be separated from the bodily world of feeling and sensation” (Ahmed 171). What she, then, callsamediatedfeeling,isonethatresembles ‘bodily knowledge’ (Ahmed 7), where our memory of a circumstance comes back to leaveanimpressiononthebodyaswereactto the repeated circumstance in the present In this way, feelings can be an avenue to explore knowledge differently and vice versa If “in order to know differently we have to feel differently” (Hemmings 150), then familiarizing ourselves with the texture of our own and other’s emotional landscapes can be more than just personally enriching, it can be informational.

ClareHemmingsarticulatesinareflectionof standpoint and affect theory that “knowledge iscreatedthroughstrugglebetweendominant and marginal voices and perspectives, and betweenoneversionofthetruthandanother” (155). In this sense, the contradictory experiences of privilege and oppression I embody can be an instrument for epistemology,onethatembracesapluralityof experiences and allows space for others to do the same This, I’ll argue, can be practiced through wonder. As defined by Sara Ahmed, wonder “is about learning to see the world as somethingthatdoesnothavetobe,andas

somethingthatcametobe,overtime,andwith work”(180).Throughwonder,wecanmove beyondsimplernarrationsofhistoryasalinear, fixed timeline into affective experiences of eventsandcircumstances.Wonderdemandsa humble curiosity and a responsible reading of historical memory, one that embraces the contradictions of emotion to foster plurality. Wonder stems from a feminist ‘passion’ (Ahmed 183) that illustrates a commitment to futurity –we can examine history by engaging the feelings of the past with the feelings of the present,inspiringadesireforsomethingbetter forourselvesandothers...Inspiringsolidarity.

Perplexity, like wonder, can be a useful tool in exploring historicity. Perplexity marks “the tension between overlapping, opposing, and asymmetric forces or fields of power”, manifesting itself as “individualized feelings of loss, anxiety, [and] confusion” (Ramamurthy 525). In “Material Consumers, Fabricating Subjects: Perplexity, Global Connectivity Discourses, and Transnational Feminist Research”, anthropologist Priti Ramamurthy explicates perplexity as a consequence of contradictory consumption practices. I wonder if for the purposes of examining my own relationship with history through perplexity, I could also explain my anxieties, unfolding the contradictions and heterogeneity of my own historical memory practices, using this concept That is to say, if other kinds of contradictions, like the contradiction between our historical identity and our physical context, can also produce perplexed subjects In the context of historical memory, perplexity could be a more materially specific way of explaining the consequences of contradictory feelings produced by conflicting circumstances. It can speak to the overwhelming feeling of realizing there are things that shouldn’t be happening, but they are, and open pathways to ask pertinentquestionsthroughwonder.

When considering my own relationship with history, my positionality takes once again center stage. As a young Argentinian, growing up meant understanding the plea for memory, truth and justice that tried to repair the damage done by the last military dictatorship, which governed us de facto from 1976 to 1983. The number 30 000, after the forcefully disappeared,wasetchedinmymemoryasa

reminderthatthestatecouldinjectterroronto civilians,andtheydid.

Asaqueerindividual,learningaboutourown specific suffering was another layer added to this mobilization of memory in the pursuit of justice.Thedifferenteffortscarriedoutbythe ArchivodelaMemoriaTrans,withwhichIhave a personal relationship, and the movements that change the number 30 000 to 30 400, honoring the at least 400 people who were targeted by the government because of their queerness, who didn’t make it to the official count, informed my understanding of where I stand As far as ‘knowing my history’ can go, the truly transformative experience was engaging with these emotional narratives, and learning that in a very literal sense, it could have been my body that didn’t make it to the count.Butitwasn’t.

Instead, my body is the one that works and paystaxesinAmerica,thecountryinwhichthis terror was planned My body is the one that getsonaplaneandleavesafterhavinglearned all of this. My body is the one that enjoys the privilege of continuing with my life, businessas-usual. But thanks to all of these efforts, I remember. These strategies to “counter forgetting” (Hirsch 3) gesture at the desire for a better future, something that remains consistent throughout feminist literature (Hirsch 4, Ramamurthy 543, Hemmings 157), and something that consistently informs my anti-imperialist struggle If my body is here, perhaps I can use it to struggle against the empire, mobilizing whatever strength I accumulate to use my emotional understandingofthepastasabridgetowarda better future. In this way, perplexity and historical memory lead to solidarity as a solution for the contradiction, and as a way of aligning myself once again with who my own experiences of historical narratives tells me I am

Thecontradictionofmyexperienceofhistory comesfrommylivingasanexpatintheGlobal North for the last five years. Because of this, the content of my emotional historical experience doesn’t match the context I’m in. I respond to things as a queer Argentinian, as a Latin American non-binary person, and as someonewhogrewupwithwhiteprivilege

evenifthewayI’mreadandthecontextI’min doesn’t require, and many times, doesn’t have space for that. In fact, many times the context I’minintheGlobalNorthrequiresthatIforget this history so that I can more easily engage with imperial politics as an insider, producing feelingsofloss,anxiety,andevendespair.The usefulness of perplexity is that it describes feelings that are easily located on the body, and thus, it can give us clearer clues to understand how it is that my body, its discourses, and its “experiences are shaped and contained by culture and language” (Ramamurthy 525) It is thus that I can comprehend my specific relationship with historyisaproductofbeingbornanon-binary Argentinian, and that my body’s physical uprooting and consequent more direct engagementwithGlobalizationandcolonialism impacts me An example of where all of these conceptscometogetherisaffectivesolidarity. Mobilized by Clare Hemmings in “Affective solidarity: Feminist reflexivity and political transformation”, this concept “draws on a broader range of emotions [...] and the desire for connection, [and is] proposed as a way of focusing on modes of engagement that start from the affective dissonance that feminist politics necessarily begins from” (148). This dissonance is where perplexity comes in, producedbyadisagreementbetweenwhowe areandwhoweareexpectedtobe,something Hemmings posits as an essential struggle to realize the need for mobilization. This is an essential notion, as it allows us to move from theindividualtothecollective.

Sorryisnotafeeling Itcanbeappropriatein certainsituations,butit’smostlysomethingwe say to deflect, to end the conversation ‘Feeling’ sorry requires little effort, little action, little searching beyond the five letters of the word. Sorrow, instead, can be a consequence ofsolidarity,orleadustoit,andIwilldefineitas a visceral experience of emotional suffering that shows up as grief, sadness, loss, and anger. As a powerful stance in aligning ourselves and our energy with an experience ofsuffering,whetheroursorsomeoneelse’s,it requires a response. Sorrow has a direction, andasthusithaspotentialtoguideustoward orthroughactionintosolidarity.Thekey

difference between this feeling and perplexity orwonderisthatitismostlyfeltwithothers. Oneofthemostpopularkindsofmobilizations for the queer and Argentinian communities I belong to are public performances of grief such as mass funerals, candlelight vigils, and marches. It has been the same for manifestations in solidarity with Palestine throughout the World. That an enormous amount of people can mobilize similar affects toshowupinsolidarityis,tome,asignthatthe feelingstheyaregoingthrougharemarkedby similar emotions of perplexity, empathy, wonder, and sorrow. As ways of knowing through feeling, these emotions can be powerful tools in the drive toward activism. Focusing on the Third World or Global South from which I come, this solidarity stems from ourownhistoricalmemory.InArgentina,oneof the few public figures to pronounce themselves against the Palestinian Genocide has been Norita Cortiñas, one of the mothers who stewards the demand for memory, truth, andjusticeoverthelastdictatorshipaspartof the Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo. As someone who refuses to forget, she brings the picture of her forcibly disappeared son, Gustavo Cortiñas, around her neck to march for a Free Palestine, and mobilizes the affects of an Argentinian mother, as well as of thehistoryofterror,todemandforjustice.

As Viviana Beatriz MacManus powerfully illustrates in “Gendered Memories, Collective Subjectivity, and Solidarity Practices in Women’sOralHistories”,stateterrorimposesa trauma that is shared and cyclical. By recovering this trauma through historical memory and oral history, women “recuperate their positions as protagonists of this history andrevealtheradicalpoliticsofsolidarity”that are buried through state-sponsored olvido, or forgetting (MacManus 137). Memory work seeking to struggle against “daily acts of forgetting” (Hirsch 7) highlights the cyclical character of both trauma and violence to expose the effort that forgetting entails. As feminist activism has time and time again shown,

sometimes remembering is the only option, and it can only happen in community.

That the Third World can picture itself in solidarity as a community was proposed by Chandra Tapalde Mohanty After Benedict Anderson’s reflections on nationalism, she posits that an “imagined community of third world oppositional struggles” can emerge to trace alliances and collaborations transnationally (Tapalde Mohanty 4). An important lesson to learn from transnational feminist activism is that the narrative seeking to binarize categories and establish discrete concepts is, in reality, masking a continuum of existencethatcanbeembracedasawhole.In this way feelings, specifically sorrow, can be a form of illustrating that continuum In aligning ourselves with Palestinian suffering we are forming transnational connections, where oppression, or at least the feelings it causes, are shared. While the author argues that a common history of struggle with empire can beastrongholdofsolidarity(TapaldeMohanty 8),Ithinkwecanconsiderhowthatsolidarityis built through emotional experiences and connections.

Inthisessay,I’veexploredmyownconnection to different concepts pertaining to affect theory, how I make this connection through history, and why this leads me to solidarity. I have observed that a pluralist epistemology can emerge from feelings, and that my contradictory experiences of privilege and oppression can be productively explored throughwonder,perplexity,affectivesolidarity, andsorrow Thisallowedmetomovebetween twodifferentspectrums:oneoffeeling,history, and knowledge, on one side, and another one defined through personal, political, and collective aspects of solidarity on the other. The utility of this analysis is that it fills in the gaps when it comes to understanding why we do activism, by providing us with language to speak to the connection between emotions and politics, as well as providing platforms for connectiontowardjusticeforPalestine,andfor all other oppressed peoples of the world. I prefer to embrace the contradiction and the difficultyofmyowncomplexitiesasanavenue tosolidarityratherthangivemyenergyoverto socialapathyanddisassociation.

Afterunderstandingthatsolidarityisaffective, and it can be individual and communal, and knowing we can move with certain fluidity between these ideas, it’s easier to understand why Bisan hasn’t pierced just my heart, but many others What we feel for her is not only sadness,itissorrow.Assuch,wearemovedto act, because us Third Worlders have felt it in our historical memory. When I say I may not know the pain, but I will remember it, I mean I willrememberitjustasIrememberthestoryof so many Argentinians, especially Trans Argentinians, who were also crushed by imperialism, and this memory will make me perplexedwheneverIamaskedtoforget.

Sources:

Ahmed,Sara.“TheCulturalPoliticsofEmotion.”EdinburghUniversityPresseBooks,2014, https://doi.org/10.1515/9780748691142.

Hemmings, Clare. “Affective Solidarity: Feminist Reflexivity and Political Transformation.” Feminist Theory,vol.13,no.2,Aug.2012,pp.147–61.https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700112442643.

Hirsch,Marianne.“Introduction:PracticingFeminism,PracticingMemory.”Women MobilizingMemory,editedbyAyşeGülAltýnayetal.,ColumbiaUniversityPress, 2019,pp.1–23.

Mohanty,ChandraTalpade.“UnderWesternEyes:FeministScholarshipandColonial Discourses.”Boundary2,vol.12/13,1984,pp.333–58.https://doi.org/10.2307/302821.

Ramamurthy,Priti.“MaterialConsumers,FabricatingSubjects:Perplexity,Global ConnectivityDiscourses,andTransnationalFeministResearch.”Cultural Anthropology,vol.18,no.4,2003,pp.524–50.

VivianaBeatrizMacManus.“GenderedMemories,CollectiveSubjectivity,andSolidarity Practices in Women’s Oral Histories”. Disruptive Archives: Feminist Memories of Resistance in Latin America'sDirtyWars.2020,pp133-161.

Managing Editors

Allison House

Agata Faran

Contributing Editor

Cas Bernardini

Editor-in-Chief

Nach Insaurralde

COARSE is an independent publication brought to you by The Dub, the feminist resource center at St. Lawrence University. Canton, N.Y., U.S.A. Spring 2024 issue.

ValeriaObregónDíaz Classof2024.

KarniKeushgerian Classof2025.

AllisonHouse Classof2026

AgataFaran Classof2026

AliceZhang Classof2025

AlessandroMarangelli Classof2024.

RenateJakobsen Classof2026.

NachInsaurralde Classof2025.