The mission of raising awareness of gender inequity on campus is complicated enough, and doing so while paying attention to the interlocking issues and systems that shape and contribute to gender inequality can be even more daunting. Having a place where students can express their thoughts and ideas, as well as where they can read and inform each other on opinions that may be unexpected to them is not just a productive and positive experience, it’s also necessary for an institution that strives for a diverse and intellectually enriching multicultural environment.

The COARSE feminist anthology is a project aiming to provide students at SLU an opportunity to publicly express their ideas on gender, race, class, and inequality from a feminist perspective. This pretends, in principle, to be a space to have important discussions in a safe environment. It is when we speak on issues that affect us, share dissenting opinions, and bring coarse topics forward that we can truly foster changemaking ideas, events, and circumstances.

In an era of hyper-surveillance, where policing has replaced accountability, and students shifted from models of citizenship to netizenship, it’s important for people to have a space in the physical world, with paper they can touch and feel and words that will not fade under the burdensome hyper information of online realities. Physical independent publications were extremely common in the SLU campus throughout our history, and they were a wonderful outlet for students who had similar (or contradicting) visions to come together and express themselves. This is why the prospect of publishing an article or piece of art in a tangible manner has a different effect from the opaque character of online discourse. The transparency and accessibility of the material object becomes more obviously real in the reader, as well as the writer’s eyes, and hopefully COARSE feels real to you. Editor Nach

Karni Keushgerian

When I came to this country, I stopped remembering how to say my name.

The letters carved on my tongue by the women of my family, drifted away and dissolved with the tears forming lumps in my throat.

When I came to this country, I became an Arab woman.

Arab first, woman second, human third.

People stopped understanding and stopped caring to listen.

My life transformed into a faraway myth and the scars of wars on my skin became lessons for those who treat me as part of their journey.

When I came to this country, I became a racialized subject.

Had I always been a colonial subject?

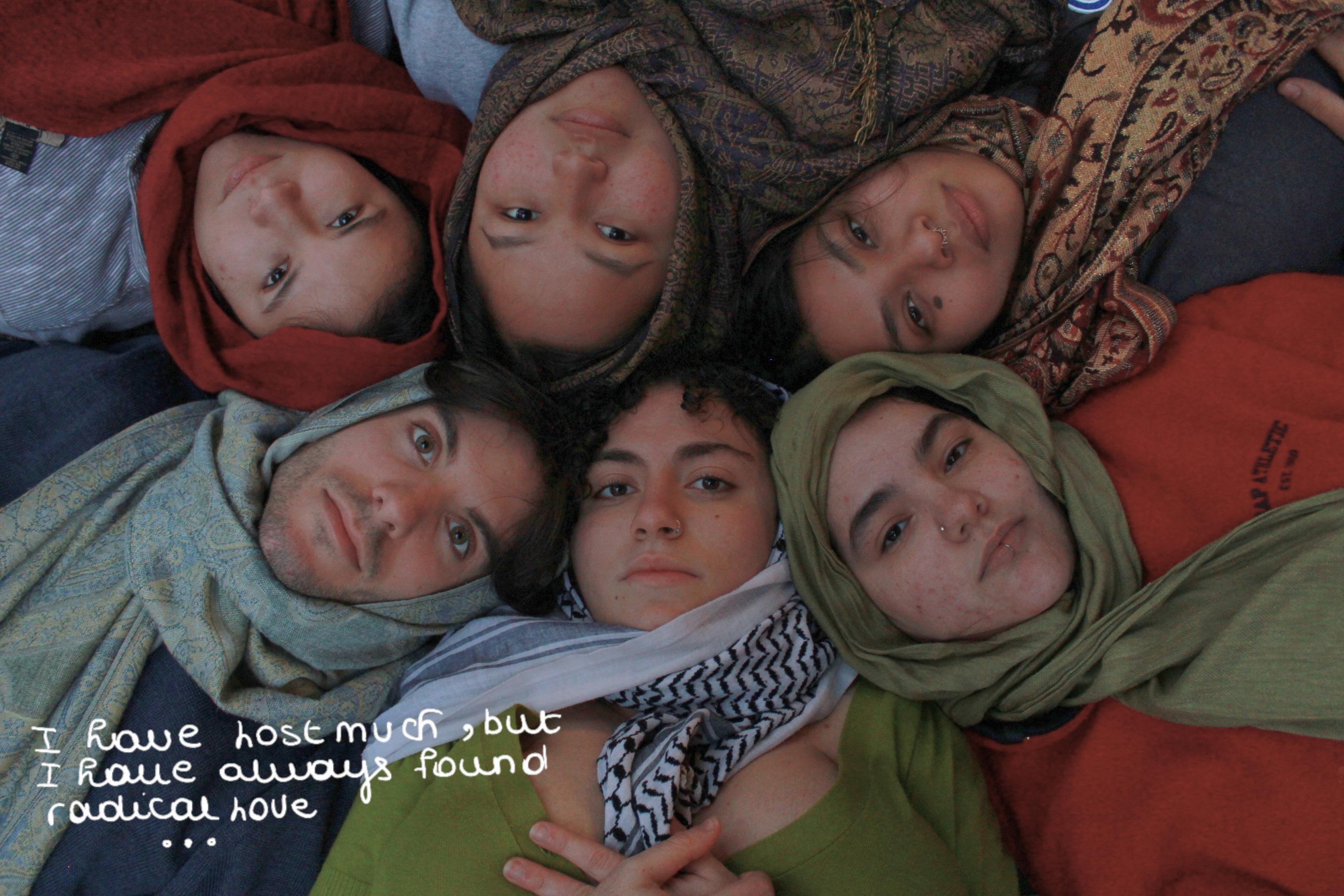

When I came to this country, I learned how to find solidarity.

Intersectionality. Familiarity.

The community found me and I have never felt so loved within my loneliness. My sadness. My pain.

I have lost much, but I have always found radical love capable of dismantling…

The systems that confine us.

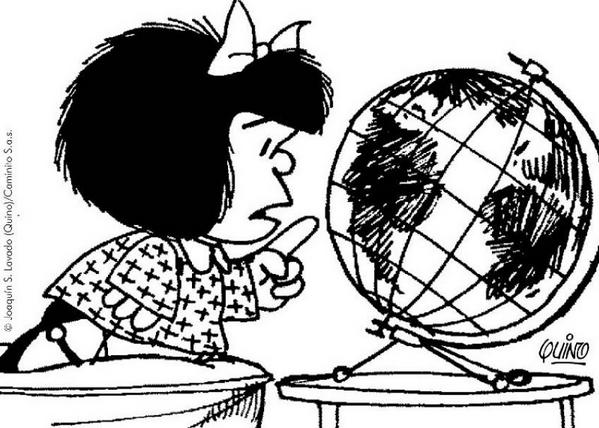

I struggle translating some words and expressions from Spanish to English: empalago, te quiero, sobremesa, madrugar. One I’ve been grappling with more recently is ternura, defined as a feeling for people, things or situations that one thinks deserving of a pure love because of their sweetness or vulnerability. You could try to translate it into tenderness, endearment, softness, but to no avail; there’s no expression like it in anglo thinking. However, I do think our world needs a bit more ternura, so I want to bring you an example. From the province of Mendoza in the Argentinian West, author Quino is celebrated for a long and poignant career as a cartoonist with an unbreakable spirit. His most famous character, Mafalda, is iconic to all Argentinians, and read all over the World.

Mafalda was published between 1964 and 1973, and her universe is interesting because of its simplicity and unexpectedness. She’s a 6 year old girl, she hates soup, and she is voraciously smart. Her biggest accomplishment hasn’t been, like Barbie, to show kids that they could be anything they wanted, but that they could want things. She taught generations of Argentinian kids that we could think, that our perspective could be interesting and important, and that our presence in the world matters. Mafalda is also an illustration that one ’ s rebellion or wits are not dependent on gender. If anything she taught us that kids can desire different things, and that we should struggle against attempts to limit that capability. My goal with this explanation is not to bring Mafalda into North American discourse, although I think her message is still relevant today. In a way, it would be a disservice to read the entirety of her literature out of the Argentinian context, but there are lessons to be learned from her yarning for a better and freer world. What I think we can take away from Mafalda is that there are more avenues of fighting the status quo than outright activist rage, that a distinctive ternura can emerge from our innate curiosity to foster solidarity and mutual care, and that, too, can be revolutionary.

These days I find myself thinking about Mafalda when faced with the harsh realities of Argentinian politics, and the slow simmer into neo fascism we are facing.

We are entering a new era marked by extreme intolerance, where all spheres of life are permeated by punitivist thinking and intensely polarized political views. Argentinian feminist anthropologist Rita Segato called this “ a pedagogy of cruelty”, a system of socialization that indoctrinates us into seeing everything as a lifeless commodity. To fight this, Argentinians rebel against the system in a variety of ways, from pointed criticism of the state and activism against world-destroying corporate greed, to forming alliances for mutual aid, fostering communal closeness and solidarity. Communal eateries (known in the U.S. as soup kitchens) for those in need, knitting circles where women make blankets for the homeless, fundraising for small rural schools in remote corners of the country. These are all examples of things that people do while their country is in crisis. How can a person turn around and give selflessly to the one behind them that which they also lack? I think it is because we are taught to care. Through cartoons like Mafalda, through conversations at the dinner table, through football and an intimate involvement with politics, Argentinians are recognized for our passion because we absorb the world around us through the understanding that we are affected by it. The kinds of relationships we form, how we understand people around us, how we interact with the world, thus, matter.

While in the past we ’ ve seen conservatives mobilize the image of the child to invoke the protection of the family and mid-20th century gender norms (although they would just call them traditional values), now we see the children they’ve advocated for use their own voices to protest the world that is being left to them. Climate injustice, political instability, asphyxiating prices for rent, healthcare, and education, among other issues, are what we face as we become adults in this globalized world that allocates resources selectively. What Mafalda can teach us is that these pleas need to be heard, not simply because of who we are, but because we make sense, and we make sense because we care. This care is also why I wanted to write this to begin with. Like many of us, I don’t know what solutions are to be found, I only know that through caring we can find community in each other, and we can be inspired both by ternura and by rage. These are not, as some people would have you think, incompatible feelings.

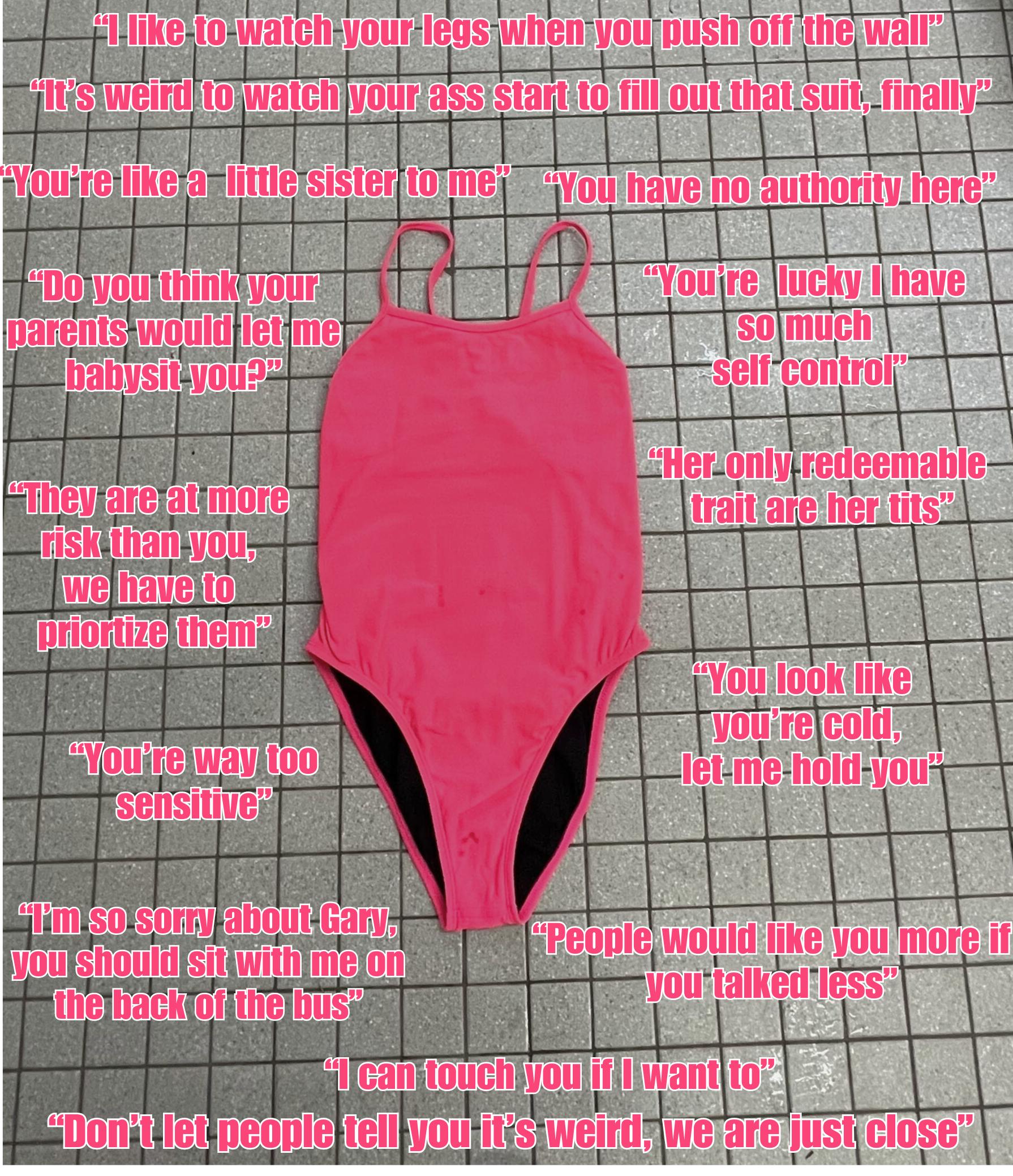

This is a picture of a swimsuit I wear a lot as a competitive swimmer. I was on a boy's swim team all throughout middle and high school. Around the suit are direct and summarized quotes about things my teammates or coach would say to me from ages 12 to 17. I don't know what word to use to describe what I went through —abuse and rape doesn't feel right, but it feels like more than harassment and assault. While these comments are not descriptive of the entirety of the team, everyone on the team knew what was happening and actively chose not to intervene. I will never forgive anyone involved.

I attended a conference at the University of Rochester in the past week called “Finding a Path Forward: Addressing Inequitable Museum Practices”. Here the keynote speaker, Silvia Forni, director of the Fowler Museum at UCLA, spoke about ethical museum practices. She spoke about how museums are centers for culture and citizenship for a state or country. She found that most museum practices were rooted in colonialism and misogyny. She also expressed the need for museums to reexamine their collections based on what is and isn’t appropriate for a museum to have. In order to do this, Forni suggests that curators need to be asking questions like “What am I trying to say about this culture with the art I have chosen?” and to think through how museum exhibitions interact with people. This caused me to ask, how do sections within museums reinforce the standard for who is good at art versus who is othered and not good? This summer I did research on gender discrimination within the visual arts, and I found an article called Review of The Legacy of Feminist Art History by Maura Coughlin. Coughlin wrote about the separation of art history courses and how oftentimes, instead of just integrating women into the mainstream art history, women are separated from it. She argues because there is a small amount of people who seek out Women’s Art History courses, this tactic often ends up othering people of color and women in the art world. As a studio art major, I have heard the resistance of many studio art majors when they have to take art history courses. Why would they be interested in taking more art history courses if they didn’t have to? What does it say to have these courses separated instead of integrating women into the art mainstream? And is there the same effect when museums section their art pieces?

Museums tend to create a timeline of art history, starting from the “beginning” of art to contemporary art. Creating this idea of a mainstream timeline, museums show you what they believe to be the foundation for all other art and what art is most influential. All other art is separated into their own sections and not integrated into the mainstream. Forni says in her talk that African art and Indigenous art don’t go past a certain date to imply antiquity, suggesting that these cultures have not made anything substantial since, or simply suggesting that that culture must have ended since there is no contemporary work chosen to represent them. An example could be the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta in 1986. They had an exhibit called “The Spirit Sings” with no Indigenous curators on the team. The Lubicon Cree Nation –a community living in northern Alberta– called to boycott the exhibition, which glorified numerous stereotypes associated with cultural objects while denying their complex contemporary realities. To make matters worse, the exhibition was sponsored by Shell, an oil company actively contributing to the destruction of the land of the Lubicon Cree Nation (Lee-Ann Martin, 2017). Another example is the exhibit called “Into the Heart of Africa” in the Royal Ontario Museum in 1889. This art exhibition was supposed to be representative of West and Central Africa. However, the museum only put work on display that was taken from British missionaries and soldiers. Rather than critiquing imperialism, they ended up glorifying it (Art History Reframed).

Women are not really put into the art timeline until later on, suggesting a lack of ability to be creative before the 1900s, and that they are behind in technical skill. This is a harmful way to set up a museum, and it reinforces a misogynistic and white supremacist way of thinking. It leaves viewers with the impression of who is capable of contributing to society in a creative way and who is not. Here we see how both art history courses and museum practices are shaping and creating knowledge. This is something reflected on by gender and feminist theorists who often think about the ways in which knowledge is created and shared. How is the way knowledge is shared and prioritized shaping who we are as people? How does it reinforce gender stereotypes? These are the questions Coughlin and Forni are asking, and this is something that Sandra Lee Bartky explores in her essay Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power. In this essay she speaks about how authorities create knowledge and categories of people and how this asserts control over them. Here we can see how those in charge of museum collections and curation reinforce knowledge creation that results in control.

How are we able to combat the harmful ways in which knowledge is created? As Coughlin and Forni suggest, and I think Bartky would agree, we need to integrate women and cultures of the global majority into the mainstream of art history and

into the mainstream timeline of art museums. By challenging the narratives of the dominant voice with different points of view of oppressed people and through representation, museums can start to help shape a more inclusive art history and history of people’s creativity. Secondly, as Forni suggests, museums need to start thinking through their museum practices, and recognize the role the museum has in silently informing society and shaping people, unlearning the harmful ways in which the museum sets up narratives about different groups of people. Forni also suggests that museums need to come to terms with the role they have had in perpetuating harmful stereotypes and acknowledge those wrongs by starting to do the work of repatriation and by exercising ethical museum practices.

Citations

Coughlin, Maura Review of The Legacy of Feminist Art History, by Fiona Carson, Claire Pajaczkowska, Linda Nochlin, and Aruna D’Souza. Art Journal 61, no. 1 (2002): 101–3.

Bartky, Sandra Lee. Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power. McCann, Carole R.; Kim, Seung-kyung; Ergun, Emek. Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives. Taylor and Francis. (2021): 342-52.

Martin, Lee-Ann. Anger and Reconciliation: A Very Brief History of Exhibiting Contemporary Indigenous Art in Canada Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry (2017) 43: 108-11

Art History Reframed. “The Wrong Place at the Wrong Time: The Failure of the Royal Ontario Museum’s ‘Into the Heart of Africa.’” Renaissance Reframed (2021).

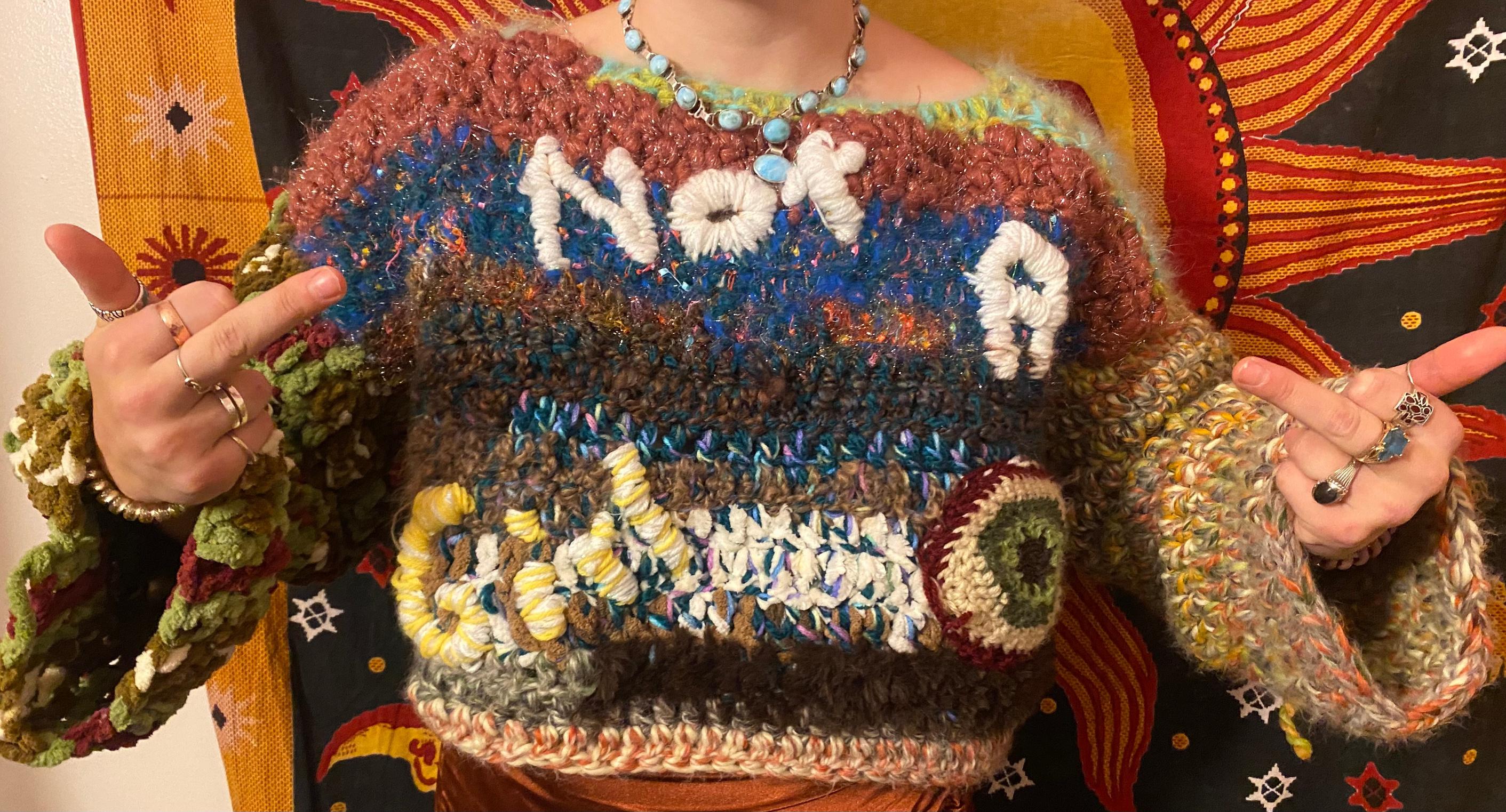

This piece represents my identity as an AFAB (assigned female at birth) nonbinary person and the challenges that may come along with it. For this piece I used all recycled, scrap yarn to create a piece that extends across the binary stereotypes. I wanted to create a piece that reflects who I am. By using scrap yarn, I wanted to embody the sense of imposter syndrome that I feel as a femalepresenting person. At some points, I feel like a mismatched person, constantly feeling as though I need to be someone I’m not to appeal to societal norms. Since I am feminine, it’s expected of me to fall into the binary stereotypes that stem from the expectation that feminine presenting people must be female. I am constantly referred to as a woman. While I am not pointing fingers at anyone who was not informed about my pronouns, I do expect those who know to respect them, which isn’t always the case. Overall, I wanted to create a piece that represents who I am, as well as creating an inviting space for others who may feel the same as well. Being feminine does NOT require you to be female.

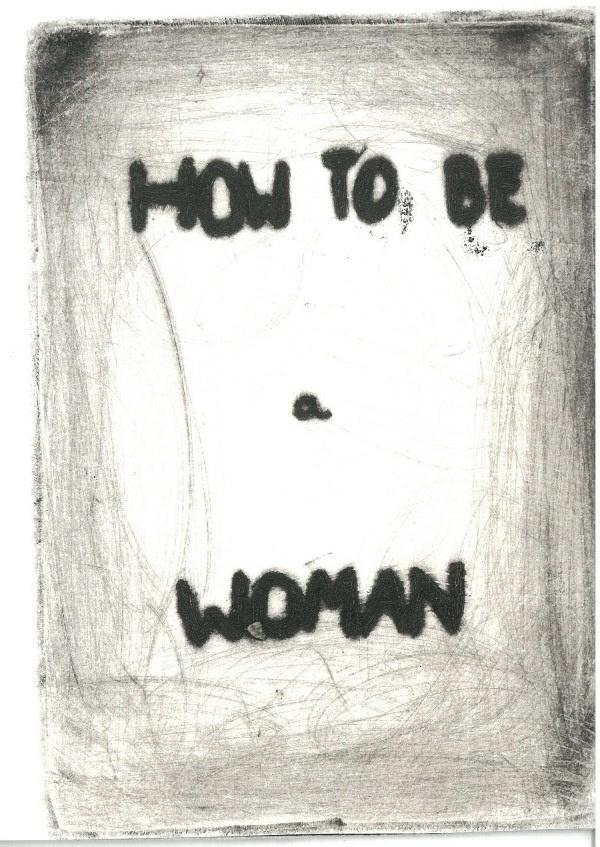

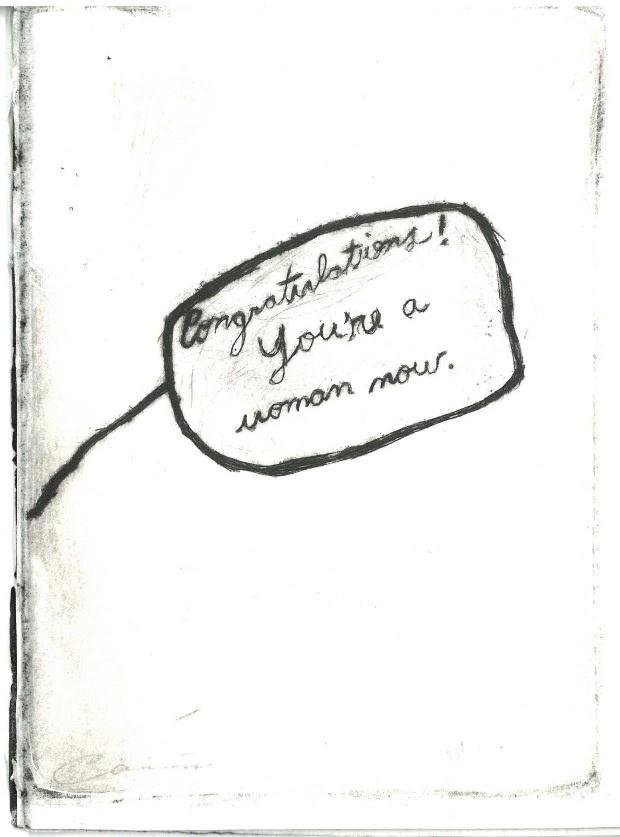

Intaglio prints, linocut prints and watercolor on handmade booklet

When I got my period at eleven years old, someone gave me a flower bouquet. CONGRATULATIONS, it read. I did not understand what it meant. Now, I can get pregnant if I get raped, I remember thinking. I was scared. I wanted nobody to know. But I felt like a woman, whatever that means. For a long time, I thought that bleeding was all it took. Today, at twenty-one years old, I barely menstruate due to health problems.

Ally Devane

I learned about my connection to feminism at a very young age. I think being raised by a single mother kind of forces you to confront how patriarchal structures operate in your daily life. Witnessing my mother work the “double shift” of balancing many jobs, then coming home to the job of caring for her three children all by herself made me feel hopeless. Seeing how easily a man can withdraw from his children made me feel fear. Realizing how readily I took on care work within my home to make up for a father’s absence made me feel rage. It was always very evident to me that these feelings must be channeled into something more. I suppose every feminist begins to identify with the movement once they realize their feelings of hopelessness, fear, or rage are communal and thus political.

Identifying with feminism has led me to believe everyone should be a feminist because oppressive gender expectations impact every single one of us. In my own life, I witnessed how the gendered expectations for heteronormative men impacted my brother. I saw him struggle to identify with the “feminine” in our home while clinging to the toxic displays of masculinity found in the media he consumed and the vision of masculinity in my community at large. For context, I grew up in a small suburban town in downstate New York, about an hour outside of New York City, where the only talk about feminism was when someone was making a joke about liberals. When considering why everyone should be a feminist, I can’t help but think about how differently masculinity could be expressed if the same men that made these jokes recognized how gender oppression impacts their own lives. For example, the burden of being a breadwinner is political, and perhaps if more men realized their frustrations with being “head of household” was comunal, we would see more equitable distributions of labor within my community.

I feel we tend to forget that we are all victims of this gender oppression and perhaps if everyone was more aware of their feelings, we would understand why everyone should be a feminist.

Another aspect of my upbringing that made me realize everyone should be a feminist was experiencing the burden society puts on single mothers. Our political system fails countless single parents who are left with no option but to balance childcare and work. I felt one way our political system failed my mother was by assigning a dollar amount to account for the absence of my father and labeling it “child support”. It was frustrating to see the state label three children as my mother’s sole responsibility, while any contribution from my father was simply seen as support. I remember as a child not understanding why my mom had to be by herself, why did she have to be the one to balance everything? Nobody had an answer for me, rather they all would tell me how much of a “strong woman ” my mother was for holding it all together. This trope of glorifying single mothers as strong women still frustrates me today. Honestly, I feel we need feminism as long as there are parents and guardians carrying this burden and as long as our politics reinforce these gendered expectations. We should all be feminists because we all are raised by someone, and we should care about how our politics support such caregivers.

To conclude, I want to make it clear that as a white woman privileged enough to gain access to a private institution such as St. Lawrence University, my feminism is constantly expanding and reshaped by the different individuals I meet, and experiences I have both in and outside the classroom. In my small town, being a feminist simply means advocating for women to have equal rights. Although in a larger global context, I have realized my feminism must be expanded to include gender liberation for all individuals and transcend borders to include feminist voices my ethnocentric education has never considered. Thus, this essay has been shaped by my feelings on why everyone should be a feminist, and this is constantly evolving as I educate myself on different forms of gender oppression throughout our society. Overall, I hope to communicate that everyone should be a feminist because everyone is affected by gender oppression, and may we always trust that our feelings can be transformed into something political.

This is a question I wish I had a clear cut answer for. As a non-binary, trans person in this very polarized and gendered World, I’m forced to ask it constantly. It will definitely torment me until the end of time, or at least until I feel safer in the communities I choose to join. My hope in writing this is not to impose any ideas on anyone, simply to untie my own thoughts, which stem from academics I’ve read or experiences I’ve lived, and to share them in case they’re of use to any readers. Before you go on, I want you to ask yourself: What is gender to me? And I want you to understand that whatever definition you find, that should be good enough for you. I’ve been made to feel like crap over my own understanding of this phenomenon many times, so my goal would never be to make you feel bad about your own conclusions. Merely to provide some context so that you can embrace other ideas, and welcome diverse notions and experiences of gender in your communities, spaces, activities, groups… You get it.

The first perspective of gender a lot of us learn growing up is something we could call gender essentialism. Essentialist thinking is entangled with biologism. That is, resorting to physical –which many times is also seen as unchanging or inherent–explanations for an immensely social phenomenon. This comes out when people speak of being “born a man or woman ” and that “there’s only two genders, because there’s only two sexes ” . I’m not going to spend too much time on this because essentialism is a flaky logic to begin with. The main thing to know about these kinds of catch-all phrases is that the science behind sex and gender would very strongly disagree. At a very basic level, biological sex has different components (like genetics, hormones, gonads, etc.), and those components can be expressed in a variety of arrangements, some of them not aligning themselves quite neatly with male and female normality. As a consequence, we have our wonderful Intersex peoples, who are a significant number of our population, and their existence alone means Humans, in fact, don’t have only two sexes –destabilizing the notion that the gender binary can be rooted in biological properties to begin with.

Going beyond the body, essentialist thinking might prescribe ‘innate’, and thus appropriate social roles and behavior to each sex, which are deemed necessary for

social normality. This notion can be debunked very quickly. Have you ever, as someone who identifies with a specific gender, been cautioned not to act like ‘the other’ gender? As a non-binary individual who was raised as a man, I can tell you I have. It wasn’t fun, but it was a way to understand that our gender norms are imposed, not inherent. If these gender norms were natural and normal to us, they wouldn’t have to be taught, and my inherent femininity wouldn’t have had to be corrected and repressed. The issue with the essentialist prescription is that it suffocates any possibility for diverse forms of being, and with that, it suffocates freedom itself. Even beyond this, the biggest mistake essentialism makes is thinking of gender as final. What does this mean, though? It means that people visualize gender as something that exists outside of social processes, outside geography, or even the body, and outside of time. As if gender was an omnipresent set of norms, behaviors and characters that are and should be the same for everyone. We are taught gender comes to be in the equation by itself and it’s meant to stay in our consciousness, unchanged. Again, this is not true. Gender is not made for us, it is made by us. Social rules are agreed upon, or constructed, and gender is one of those. I know this for the same reason I know gender is imposed: we are as diverse in our collective norms and regulations as we are individually. In fact, getting many indigenous populations to accept the European gender binary was part of the colonial project throughout the World. But the non-binaries, the two-spirits, the Muxes, the Hijras and Machi Weyes are still here, because we ’ ve made a whole different set of gender and social norms than the European standard. Fortunately, indigenous communities are more resilient than the colonizer would like.

For Beauvoir it’s something we become, for Butler it’s something we construct through repeated action, or ‘performing’, for Argentinian law it’s something we, through identity, experience intimately, and for bisexual activist Robyn Ochs it’s something we breathe; it exists in the air between us. What all these definitions have in common is that they don’t think of gender as natural, but as a constructed process. It doesn’t necessarily have a destination, it exists in its own making. Here we arrive at the ‘gender is a social construct’ of it all. In addressing this, I will put it simply: You're right, gender is a social construct. But repeating this without stopping to think about what we ' re saying is not productive if what we want is to really change how people come to experience it. Gender being a social construct doesn't necessarily mean that it's made up, a mere fantasy we ' ve created to oppress each other, and that it's void of meaning. It means, rather, that gender is made and remade everyday in the interactions that compose our societies, and in the privacy of our own actions, thoughts, and desires.

Gender doesn't just affect the way we feel about ourselves but the way in which we

perceive and interact with the world around us, the way we come to think of the very essence of our beings. And in the same way we don't go out the door thinking the same thoughts every day of our lives, and we receive and interpret our contexts differently depending on our mood or whatever else is making us think differently about life, we also experience gender diversely every day, every hour. You might wake up today feeling insecure because you don't look like the men who get praised on social media, or feel comfortable and beautiful in your femininity today yet feel the opposite tomorrow. Gender being a social construct doesn’t mean it’s not real. It’s quite the opposite actually, it means it’s real because we ’ ve made it. Before understanding its building blocks –the diverse rules, impositions and restrictions we have placed on men and women–, and how those building blocks interact with race, culture, class, and identity, it’s important to accept that there are building blocks to begin with.

We pointlessly gender things like our voices, capabilities, and interests to make us feel more confident. We see it materialize all around us so it becomes a reliable form of reassurance one can hold on to when our own personhoods and experiences seem uncertain. But the irony is that what seems to make gender solid is what dilutes it. When we assign a property of gender to everything, we start to naturalize its influence and reach, and gender starts to become invisible due to its normalcy. The irony becomes paradox when gender as personal reassurement makes characteristics, activities and experiences gain significance outside of their own merit. This happens when we decide that Women make better nurses than they do doctors, or that Men make for worse parents than Women. The activities or experiences of healing and parenting, with all of their important qualities, start to become secondary to the gendered value we give them. In this way gendering arbitrary things obscures the potential for becoming, and when we assume this gendering is inherent and necessary, we give our own agency and potentials away. That which gives us strength starts to make us weaker.

There is much more to be said about gender; what we have made of it and what it has made of us. Feel free to add to this article, respond to it, do black-out poetry with it, or even origami. Either way, I hope it is useful.

Once you are done with COARSE, pass it along to a friend. Speak to people. Be a feminist (if you want).