52 minute read

OUTDOORS

CREATIVE SHORES

We found countless coastal spots in Northern Michigan that offer the perfect place to journal, paint or photograph—or simply let the muse arrive. by KANDACE CHAPPLE

On a friday summer afternoon, I take my golden retriever, Cookie, out to Lake Michigan. We drive from Lake Ann to the last stretches of Benzie County Road 610, where it dumps us out on the rutted, barely paved Esch Road to Lake Michigan.

I settle in with Cookie on a blanket. We are alone on this magnificent beach except for one bald eagle making its way directly over us. For years I have threatened to do this—take off and just create. I never dared to; it just seemed too indulgent. But once I am quieted, the muse likes it. Cookie finishes her swim and enjoys the breeze coming off the lake. I take out my journal and begin.

Here’s a short list of places for artists of all mediums to find inspiration.

Cookie at Esch Road Beach.

DOWNTOWN TRAVERSE CITY

Crooked Tree Arts Center (in Traverse City and Petoskey) also offers a “Paint Grand Traverse” plein air event each year. Plus, there’s a secret spot to create on the docks behind Morsels, a bakery and coffee shop in downtown TC, along the Boardman River. As the bustle goes on above, you’re down on the water’s edge under shady trees. Get a bite-sized pastry from Morsels to complete the rapture.

OLD MISSION PENINSULA, TRAVERSE CITY

A scenic pullout/overlook along Center Road on Old Mission (about 8 miles up the peninsula) offers an amazing view of the west arm of Grand Traverse Bay. Here, you’ll have the choice of painting the bay as well as sunsets, cherry orchards, apple orchards, wineries and farmhouses.

FISHTOWN, LELAND

Weathered fish shanties and historic tugboats along the Leland River and a narrow maze of wooden docks and shops make the perfect destination for painters and photographers.

BAYFRONT PARK, PETOSKEY

This stretch of land along Little Traverse Bay includes the Petoskey Marina, lighthouse and breakwall, and a park with several grassy areas and picnic tables at which you can set up for the day and work. Bayfront Park is known for its perfect sunset view, so plan to come in the early evening. Climb the stairs to reach Sunset Park above, offering a higher perspective and overlook of the bay.

photo by Kandace Chapple

SLEEPING BEAR DUNES NATIONAL LAKESHORE, EMPIRE

An artist with their easel is a common sight at the Lake Michigan Overlook on Pierce Stocking Scenic Drive. In fact, every August, Glen Arbor Arts Center (GAAC) hosts their “Plein Air Weekend,” where artists are invited for a “Paint Out” to capture the villages, overlooks and lakes in the area. The pieces are then sold as a fundraiser to support GAAC. Other places along the lakeshore that inspire: Empire Bluff trail (see every shade of green to blue in Lake Michigan from above) and Glen Haven beach (paint or photograph the historic Cannery Boathouse Museum—a beautiful red building against the blue water).

POINT BETSIE LIGHTHOUSE, FRANKFORT

This is easily one of the most iconic lighthouses in Michigan, depicted in photographs and paintings many times over—and quite possibly the setting for a few star-struck lovers in a book or two. The serene white-washed buildings make for a striking contrast to the roar and roil of Lake Michigan. Perch on the bluffs to paint or write. Stay until dark and wait for the Milky Way galaxy to present itself in the night sky—it doesn’t get any better than that when it comes to sparking creativity.

Kandace Chapple is a freelance writer and owns Michigan Girl, a company that hosts outdoor events and trips for women in the Grand Traverse region. mi-girl.com

here

BY SARAH BENCE PHOTOS BY SARAH BENCE AND ALLISON JARRELL the

comes

DISCOVER THE SUNFLOWER FIELDS OF NORTHERN MICHIGAN.

NORTHERN MICHIGAN'S MAGAZINE 29 sun

witnessing

a field of sunflowers all standing together, turning their faces to follow the sun, is a sight to behold—one that’s inspired artists like Van Gogh, Monet, Klimt and more. Cultivated by Native Americans, glorified by the Aztecs and the subject of Greek myths, sunflowers have a long and varied history that’s fascinated people across the world. Despite public adoration, farmers agree that sunflowers are a persnickety crop, with their gangly stems and sensitivity to weeds and weather. They are worth the hard work, though, because they have something special beyond their harvesting purpose. Sunflowers bring people together. In Northern Michigan, this means a communion of hard-working farmers, smallbusiness owners and a host of visiting Michiganders seeking a good photo, a laugh or a day outdoors. But it can be difficult to find sunflower fields, especially because the farms and nature conservancies that host them are not solely dedicated to these blooms (they also grow other crops). You can’t simply Google sunflower fields and find a robust list.

Good thing you’ve got this guide!

when to go

Exploring Northern Michigan’s sunflower fields at peak bloom, when each one is a fabulous burst of color, will take some advance planning.

Sunflowers are impressive. In just a couple months, a small seed transforms into a plant often taller than a grown adult. However, they have a relatively short window of life at full bloom. Additionally, due to their long stems, sunflowers can easily succumb to the elements, like a heavy rainstorm or early frost.

In the North, sunflowers tend to bloom from late July through early September, but that sweet spot of peak bloom may last for only a week during that period.

This window of peak bloom differs significantly between farms, even those located nearby, because it depends on when the farmers planted their seeds. Some farms plant in succession, which can spread the flowers out over two to three months, whereas others have one fast and glorious bloom.

If you are driving a long distance or hoping for a full day in the fields, plan ahead by contacting the farmers and asking about their estimated bloom window. Many share updates on social media. As August approaches, it’s easier to estimate when the sunflowers will be most magnificent.

what to bring

Each of Northern Michigan’s sunflower fields is unique. Some involve pulling off to the side of the road and respectfully appreciating a farmer’s hard work. Others have responded to the public’s growing interest and have more established parking areas and amenities.

Either way, here’s what you’ll need to make the most of your visit:

• Camera • Sunscreen • Bug spray • Sun hat • Water • Sturdy shoes • Cash for donation

Some farms provide scissors and pruning shears for you to pick sunflowers to take home. If these aren’t provided, then it’s best to assume U-Pick is not allowed, and enjoy the field with your eyes and camera only.

5 PLACES to see sunflowers in northern michigan

HALL FARMS

location: 2623 St. Nicholas 31st Rd., Rock, U.P. owners: Dan and Teressa Hall

best time to visit: Early to midAugust, with peak bloom lasting seven to 10 days. Watch their Instagram and Facebook pages for bloom and weather updates.

U-Pick? Yes ––Located in the Upper Peninsula, half an hour north of Escanaba, is one of the most impressive sunflower farms in the state. Dan and Teressa Hall began farming 40 years ago, growing sunflowers to harvest for bird seed. A few years later, some people asked to take graduation and engagement photos among the flowers. “[When they] posted their photos online, the requests to see and photograph our field exploded,” Teressa says.

Now, their roughly 20-acre field of hardy black oil sunflowers is open to the public each summer. It seems to stretch endlessly toward the sun, and visitors can immerse themselves in the flowers with walking paths, elevated viewing decks and photo opportunities (such as a giant painted minion) that Dan and Teressa have created over the years. It is a photographer’s playground. “Our sunflower field has grown every year beyond our wildest imagination,” Teressa says. ––

favorite thing about growing sunflowers: “Meeting and talking with visitors; hearing their stories about why they like to come here and seeing their beautiful photos.”

–TERESSA HALL

SEND BROTHERS FARM

location: 8670 Bates Rd., Williamsburg (at Bates and Hawley roads) owners: Mark, Eric and Marty Send

best time to visit: Mid-August, but check for updates on their Facebook page.

U-Pick? No

Mark Send, Send Brothers Farm

With more than 350 acres, you’d think the Send brothers’ sunflower fields would be hard to miss. But you’ll need an old-fashioned map to the intersection of Bates and Hawley roads in Williamsburg. The Send brother’s impressive fields won’t show up on any GPS because they’re just that: fields in a working farm.

Despite being a working farm, visitors are welcomed each summer to pull off to the side of the road and view the flowers. “Please don’t pick the sunflowers, just admire their beauty,” says Mark, who partners with his brothers Eric and Marty to run their farm and feed business. This will be a particularly poignant year for the Send brothers’ sunflowers. Two years ago, their fields were destroyed in a matter of hours just days before peak bloom by a terrible wind and rain storm. However, the Send brothers have been farming for their entire lives, says Mark, and that will continue this year. ––

favorite thing about growing sunflowers: “To see the beautiful artwork that you and God have created and to see people enjoy them.”

Peter Leabo, Leabo Farm

LEABO FARM

location: 9224 East Duck Lake Rd., Suttons Bay owners: Peter Leabo, Michael Leabo, Shari Crider, John Leabo and Mary McMananney

best time to visit: Due to succession planting, blooms last for two to three months, from July through September. Check their Facebook page for updates.

U-Pick? Yes ––

If you’ve ever driven across the Leelanau Peninsula on a late summer day, you may have been lucky enough to have seen the blooming sunflowers off M-204. This is Leabo Farm, which has been operating for more than 60 years since it was started by Peter and Josephine Leabo in 1962. Now, it’s run jointly by their children. Twelve of the farm’s 150 acres are devoted to sunflowers which, set against a weathered barn and green woods, are a beautiful sight to see.

“We’re open to having people stop by and take photographs,” says Peter Leabo, one of the co-owners of the farm—and who has been playfully dubbed “Sunflower Pete” on social media by one of his siblings. There are parking spots off M-204, and U-pick is available on an honor system. During your visit, you’ll likely run into one of the Leabos. You’ll also find a few ladders and platforms throughout the rolling field, which are perfect for

Virginia Coulter, Old Mission Flowers photo opportunities.

“We have a lot of people who come back year after year,” Peter says. “It helps the farm stay viable in a new age. We like to have the community.” ––

favorite thing about growing sunflowers: “Sharing them with other people.”

–PETER LEABO

OLD MISSION FLOWERS

location: 16550 Center Rd., Traverse City owner: Virginia Coulter

best time to visit: Open daily from dawn to dusk during the summer months. Due to succession planting, sunflower blooms can last two to three months.

U-Pick? Yes favorite thing about growing sunflowers: “Sunflowers are miraculous! It never ceases to amaze me that I can plant a seed and a couple of months later have a plant taller than I am with a flower bigger than my head.”

–VIRGINIA COULTER

Leabo Farm

Maple Bay Natural Area

“My vision was quite small: I wanted to quit my job and grow flowers,” says Virginia Coulter who, at the age of 60, started a small cut flower farm near the northern tip of Old Mission Peninsula. At just over an acre and with more than 100 varieties of densely planted flowers, this isn’t a typical sunflower field. What you will find, however, is one of the best views in Northern Michigan: a few rows of tall sunflowers high on a hill, directly overlooking Grand Traverse Bay.

Old Mission Flowers is an ideal destination for gardeners and photographers alike. Unlike many of the larger farms, there are fewer sunflowers here but more diversity: orange, pale yellow, chocolate, multicolor; and in 2022, Virginia plans to plant a pink variety. This is a self-serve pick-a-bouquet business, so you can drop by anytime and cut your own flowers.

MAPLE BAY NATURAL AREA

location: On either side of US-31 in Williamsburg, near Maple Bay Farm owners: Grand Traverse County owns the property but leases it to local farmers.

best time to visit: Early to midAugust, but be aware these fields aren’t planted every year.

U-Pick? No ––The fields here are a part of Maple Bay Natural Area but are leased to a local farmer by the county. You should know there isn’t a guarantee you’ll find sunflowers here—the crops are often rotated every other year. That said, last year was meant to be the “off” year, but row after row of sunflowers popped up. It’s worth taking the chance to drive by. For the best parking spot to view these fields, drive south of Maple Bay Natural Area, parking off US-31. On the west side of the road, right after you pass the Maple Bay Farmhouse, there should be a small gravel lot with space for about five cars. Here, you can walk along the field and there is even a platform set up for better viewing. Last year, there was a small wooden sign

–Virginia Coulter

reading simply: #outerrimfarm. It may be worth checking this hashtag on social media before your visit, to see if the sunflowers are in bloom.

Sarah Bence is a freelance writer and occupational therapist based in Michigan. Follow her travel blog @endlessdistances on Instagram.

Allison Jarrell is the managing editor of Traverse, Northern Michigan’s Magazine. Reach her at allison@mynorth.com.

When a few hundred strokes

are the difference between a comfortable night’s sleep or shivering in a damp tent pitched on uneven ground, you make them count.

As we dug our paddles into the confused water, waves broke over our boards, and a 30knot wind pushed us farther and farther from our destination. We made brief eye contact with each other in the rain as we realized we weren’t just fighting for a good campsite, but also our lives.

You may be wondering why three guys are sitting on paddleboards during a violent Lake Superior storm.

Let’s back up.

For generations, Isle Royale served as a port for many vessels. From the beginning, Native Americans paddled their birch-bark canoes to its basalt shoreline in search of copper and game. Mackinaw boats followed, sailing around the island in search of fish and furs. At the turn of the century, steamships whisked passengers to luxury resorts while fishing tugs bobbed in protected coves as they hauled in their catch.

Today, most people who explore this wild place travel by foot, kayak or canoe. The three of us—Liam Kaiser, Grant Piering and myself—are longtime buddies and avid paddlers; we wanted to experience the park by paddleboard and prove it can be done safely while having a great time.

We set sail on the ferry from Copper Harbor to Isle Royale with calm seas, and a few hours later Greenstone Ridge broke the horizon line; at 45 miles long and 1,394 feet tall, this prominent feature acts as a backbone for the swamps, bogs, ridges and valleys we’d soon be exploring.

photos by Liam Kaiser

Isle Royale is Michigan’s only true national park (Sleeping Bear Dunes and Pictured Rocks are national lakeshores). It contains 99 percent wilderness and is known for the population of moose and wolves that call it home. The park’s list of superlatives is long, but my favorite one describes Ryan Island in Siskiwit Lake, which is in the middle of Isle Royale. Ryan Island is “the largest island in the largest lake in the largest island in the largest lake in the world.”

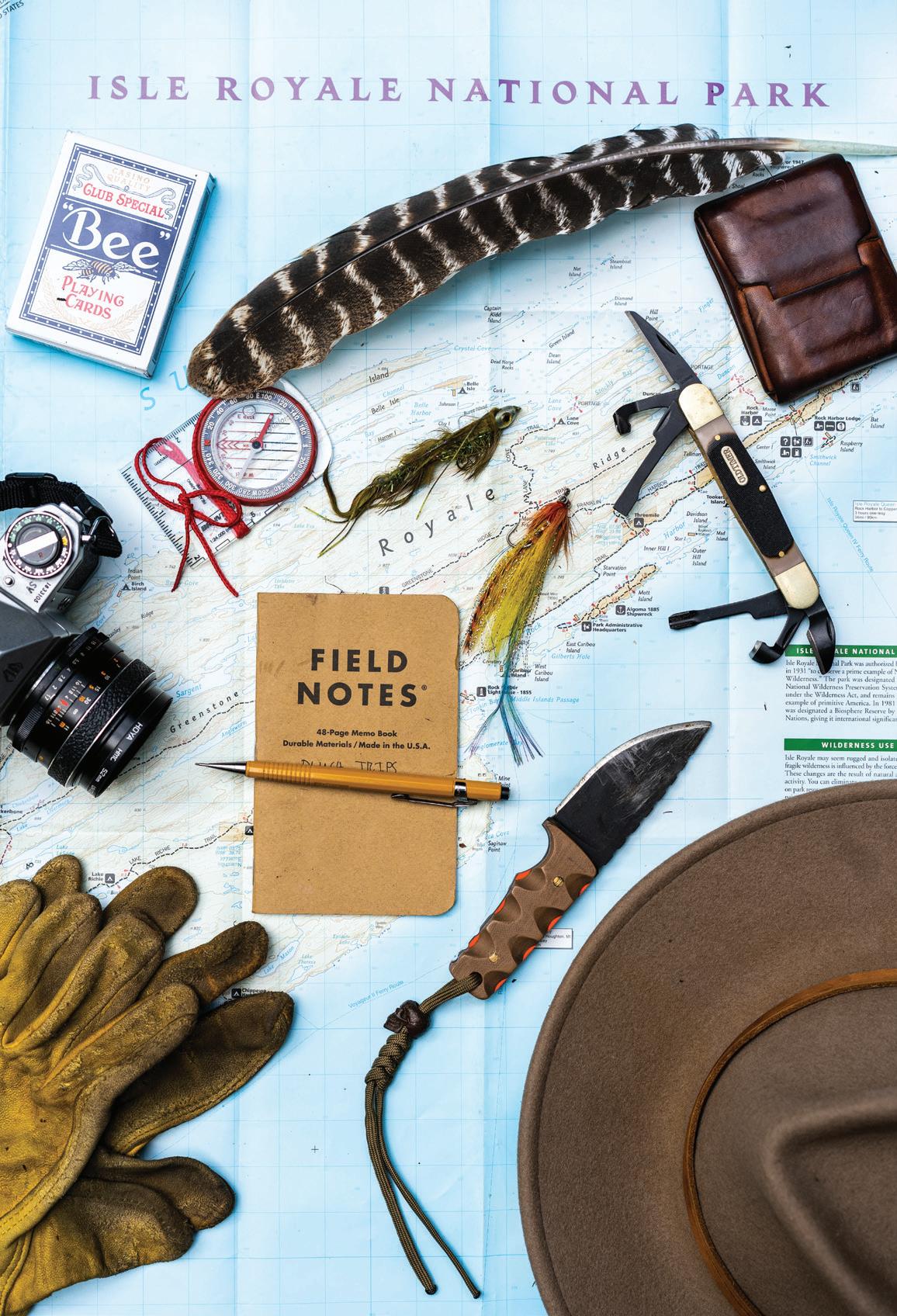

From left: The journey begins. Sam and Grant take their first few paddle strokes in Rock Harbor; Trip essentials: Knife, gloves, camera, cards, compass … turkey feather? That’s Sam’s good luck charm.

As we slowly motored into Rock Harbor—the island’s main arrival point and home to a visitor center, lodge and marina—passengers clung to the cold steel railing on the bow to soak in the views. A recent wildfire on the island’s northern end smoldered, and clouds of gray smoke wafted ominously from the charred remains. Were we crazy to consider paddleboards as worthy crafts to explore these waters?

Yes. The park ranger raised her eyebrows when I told her our itinerary, and visitors beamed glances of concern and even confusion as we unloaded our boards from the crowded ferry.

Once on shore, we crammed our drybags with supplies. If we forgot something it was too late now; if something didn’t fit, we crammed it harder. Boards loaded, snacks packed and life jackets snugged, we hoisted the sails of our adventurous spirits, left the skeptics and headed south toward our first campsite at Caribou Island Campground. The first few strokes from Rock Harbor were revealing; with eight days of provisions, our boards were heavy and cumbersome, and we had 49 miles to paddle and 18 miles to portage over the next week. But as we worked our way south, we found our cadence and settled into a rhythm.

Paddling is meditative. When your board carries everything you need to survive, moving the craft goes beyond a chore and becomes a necessity. We embraced each stroke—refining our technique, demanding more from our core and encouraging each other with hoots and hollers.

Our journey would take us on a clockwise loop around the northeastern tip of the island (see the map on page 38). On the first day, we paddled south from Rock Harbor toward Moskey Basin. Once on the basin’s swampy edge, we portaged and paddled our way inland to connect with four tannin-stained lakes—Richie, LeSage, Livermore and Chickenbone. We’d get to know the island’s interior well as we carried our boards and drybags through the glacially warped terrain of drumlins and moraines under a dwarfed mantle of white cedars, black spruce and paper birch.

Eventually, we’d weave our way through McCargoe Cove where the fjord-like walls would guide us out of the protected waters and onto the northeastern shoreline of Isle Royale, also known as the Five Fingers. There, we’d be exposed to the prevailing winds and swells on Lake Superior as we paddled in open water back to Rock Harbor—the same elements that drove the wrecked ships in these icy waters to their graves. A risk worth taking, according to everyone we spoke with—just not on paddleboards—but for us, once we arrived, there would be no turning back.

getting used to it. It had been four days since we’d seen anyone else. Our minds and bodies were adapting to the stillness, and sleep came easy after a few nights, even with Liam’s snoring. The island became a part of us—the lakes hydrated and bathed us, and squishy carpets of moss cradled our ragged bodies while we peeled callouses off our hands during portage breaks.

Our daily camp routine revolved

Above, from left to right: Grant and Sam take advantage of calm weather on the ferry and catch up on some reading; Moose antler sheds rest at the base of a wooden map in Rock Harbor; Liam’s 35 mm film camera captures a different vibe as Sam and Grant contemplate what’s for lunch (sardines and smoked oysters); Built in 1855, Rock Harbor Lighthouse is the oldest lighthouse in the park, and hosts a museum that’s open to the public. Left: Grant portaged a 45-pound rigid touring board on his head. Legend has it his head is still sore.

Isle Royale hits everyone a little differently and getting to know it would take a lifetime. For me, I wasn’t surprised that a 206-square-mile ecosystem nestled into the world’s largest freshwater lake (by surface area) made me ponder my existence. And exploring these waters with two good friends could make or break the friendships that brought us here.

Paddling in a stiff headwind in the rain for a few hours reveals the depth and quality of someone’s character. I found myself asking: “Can we endure? Will they still like me? Did Liam bring enough food?” We used our strengths and leaned into each other when we needed help. Liam provided comedic relief and Grant’s calm and calculated demeanor never let things get too out of hand.

Trips like this give us an increasingly rare chance to really see what we’re made of beyond the stage of social media—what a relief. How deep can we dig when no one else is watching? If we do something radical, and Instagram doesn’t know about it, does it still count?

Paddle, camp, eat, explore, eat, sleep; this was life, and we were around a system of different colored bags that defined our rhythm; unpack, pitch the tent, fetch water, put on dry clothes.

In the mornings we did it in reverse, putting everything back in the correctly colored bag, sliding into a smelly shirt and lashing everything back onto the board. I admit to instinctively reaching for my phone while sipping coffee the first few days. But that faded. The essence of this trip was escape—and I was reminded that when we remove ourselves from our modern lives and focus our distracted minds on the tribal mentality of survival, everything else seems trivial.

On our itinerary, we had eight days to paddle a distance that most experienced paddlers can do in four or five. This was intentional. In the past I’ve regretted packing on miles and not allowing enough time to savor the places that I worked so hard to get to. Our daily mileage wasn’t brutal (never more than six miles) and we typically didn’t spend more than four hours on boards.

We woke when we felt like it and sipped coffee without the nagging urge to pack up. We took naps on sun-warmed striated bedrock slabs, casting lures on the edge of weed beds for pike and

The trip was going well. The days were pleasant and warm in a place with famously fickle weather. No injuries, only a few bug bites, and all of our gear was still dry–but Lake Superior wasn’t done with us, yet.

frying SPAM in foaming puddles of butter in the warm morning sun.

Most days, we’d set up camp and then head back out on our unloaded boards to explore the coastline without the burden of gear weighing us down. One of those days, the wind was in our favor for a change, so we lashed our paddleboards together to create a large raft—Tom Sawyer-style.

From our expanded platform, we sunbathed and munched snacks in the middle of the fourmile long Amygdaloid Channel while a two-knot breeze scootched us back to camp. I sent a lead lure down into 100 feet of water and jigged the rod as the current swirled around us. I caught and released a Coaster—an endangered species of

Isle Royale National Park

Finish

Brook Trout only found in Lake Superior—and kept a whitefish that we roasted in tin foil over glowing coals for dinner that night.

Many visitors choose to hike the island, and backcountry hikers are required to camp in designated campgrounds. One of the major perks of paddling is the isolation. Paddlers have the option to camp on smaller islands off Isle Royale that are only accessible by boat. These campsites feel wilder and don’t make you feel as bad about skinny dipping. Beyond the luxury of having a quiet campsite, paddling provides access to the best part (in my opinion) of the island—the Five Fingers. On the northeast corner of Isle Royale, long ridges and small islands emerge from Lake Superior and run parallel to the mainland creating a playground of protected water and a glimpse at the impressive geologic history that makes this island so unusual. It’s truly hard to comprehend the volcanic action and glaciers that formed this paradise billions of years ago, but paddling the Five Fingers gives your imagination plenty to work with. The elevated view from a paddleboard gave us a clear glimpse into the serene waterscape just beneath us. Granite ledges, boulders and fallen logs join the layered volcanic and sedimentary bedrock sequence Start that cascades down into the depths. Fragments of the island’s human history—docks, buildings and fish shacks—stand in various states of decay, reminding us of the resilient souls who made a living on this island before it was a national park. For a closer look at the depths, we grabbed boulders from the shallows, taxied them to the middle of the inlet on our boards, bear-hugged them, and rode them to the bottom of the lake. Forty feet down, with a snorkel mask and lungs full of air, we embraced the stillness of the lake while our heartbeats thumped in our ears and silt swirled in the frigid blue thermocline. The trip was going well. The days were pleasant and

warm in a place with famously fickle weather. No injuries, only a few bug bites, and all of our gear was still dry—but Lake Superior wasn’t done with us, yet.

On our second to last day, we woke to rain on Belle Isle, a long island in the Five Fingers known for its productive lake trout reefs. As we packed our gear, the wind picked up from the south, but it was hard to tell how strong it was from the protection of our little cove.

Once we paddled out, we saw that the wind had reached a sustained 30 knots and was violently sweeping across the channel we had to cross. Three-foot waves forced us to straddle our boards and ride them like seasick cowboys on bucking stallions.

Wind gusts pushed us toward Canada as we fought the turbulent lake swell, but once we’d started, it was too late to turn back.

I squinted through the rain and lake spray to see if the guys were struggling as much as I was. Liam shouted above the howling wind, “I can’t do this.” His voice quivered with fear.

We decided to pull over on the leeward side of Dead Horse Rocks, a small island about the size of a two-car garage. We knew we had to cross this channel to catch the ferry leaving tomorrow. We made a plan—paddle quartering downwind to the point on the opposite side of the channel.

We tried again. The wind increased. It rained harder.

We failed, again.

We sought protection on the leeward side of Green Island and decided to wait for the wind to die. This long skinny island was our last resort. If we left this spot and were blown out into open water, our next landfall would be Canada, 50 miles away.

I looked for a campsite. With one bar of cell service, I sent a text to my wife, “Lots of wind, might miss ferry, we are safe, love you.” I was also able to pull a forecast that said the wind would die at 3 a.m. That meant at first light we could paddle the last 14 miles to the ferry dock before it left at 12 p.m. If the wind died.

So, we waited. The sun came out, but the waves still raged as we cinched our hoods around our faces, napped on weathered driftwood logs and nibbled wet chocolate bars while weighing our options. The only sliver of flat ground on the island wasn’t flat. Everything was damp. As I sat on a bed of moss in the scraggly dwarfed forest, I could feel the waves reverberate through the soil as they crashed on the shoreline. Was this home for the night?

Then, even though our passage was still a frothing mess of confused waves and wind gusts, the wind direction shifted. Now it was coming out of the southeast—worst-case scenario, we would get blown back to the island instead of to Canada.

The rain stopped and the passage no longer looked as ominous, but it still filled us with dread. I spoke with Grant, and he agreed we could now make the crossing. I approached Liam, told him I wouldn’t ask him to try if I didn’t think he could make it. He was ready.

It was only a third of a mile but it would be the hardest paddle of the trip, maybe our lives.

We rounded the leeward point of the island to face the wind head on and began paddling across the channel. We moved backward with the first few strokes, not anticipating the strength and resilience of the elements that still swirled around us.

After a few more heartfelt strokes into the wind, we finally made some headway. I glanced to the north where giant waves farther out on Lake Superior made the horizon look like a distant

Clockwise: A quick sear with a hot knife blade takes care of the leech on Liam’s foot; Sam admires a whitefish he reeled in from the depths of the Amygdaloid Channel—dinner is served; One of the many camping shelters available throughout the island. These are first-come, first-serve and provide a welcome sanctuary when the weather turns, or you need to dry your gear; Grant descends through the thermocline with a granite boulder for assistance; Morning light from Belle Isle campground.

mountain range, jagged and foreboding. After 20 minutes, we were in a swell shadow from an island just south of us; 10 more minutes and we made it across.

Thirty minutes of terror, but our journey wasn’t over yet—there were still six more miles to go. We’d made it to the north side of the island, but with a southeast wind, we could judiciously follow the coves and inlets to escape its menacing presence. The next mile was pleasant, but we had one more open water crossing to go, harder and longer than the first. Isle Royale, clearly, wasn’t going to let us off that easy. And I’m glad she didn’t. We should have assessed conditions that morning in camp before we left, and now, we were paying the price for our ignorance.

That final grueling crossing made the last miles seem effortless. I began to feel a sense of closure; our dry bags were lighter, portaging was a breeze and our blisters were healing. We glided across a protected inlet toward our final campsite of the trip.

We woke to rain, but no one seemed to mind. Spirits were high, despite a growing head wind; soon swollen rain drops made the placid cove come alive as they crashed into the water. A park ranger motored up to us as we coasted down the inlet, paddling the last few miles between us and the dock at Daisy Farm.

“Was that you guys crossing Belle Isle channel yesterday?”

“Yeah, that was us,” we sheepishly replied.

“I was watching you guys from the mainland; you’re crazy.”

“Yeah, we know.”

It’s not that we’re careless—we spent weeks planning this trip and would never recommend it to novice paddlers. It’s just that people have yet to see how capable and functional paddleboards are for long excursions. We believed in them— and ourselves—and were rewarded with fellowship in wild places and the valuable life lesson of trusting our instincts.

Sam Brown writes from Empire where the land, lakes and people inspire his writing. Tag along with his outdoor pursuits on Instagram @gnarggles.

Liam Kaiser is a visual storyteller with a strong love for the outdoors and the grit that comes with it. Follow his adventures on Instagram @LiamKaiserCreative.

A TRIP TO ISLE ROYALE REQUIRES PLANNING AND FORETHOUGHT. DON’T LET THE DETAILS OVERWHELM YOU AND TAKE THEM ONE STEP AT A TIME. NPS.GOV/ISRO

TRANSPORTATION

Plan ahead; the ferry books up well in advance and the schedule changes based on the seasons. Ferry: From Michigan, depart on the Queen IV from Copper Harbor or The Ranger III from Houghton, which drop you off and pick you up at Rock Harbor. Sea Plane: You can take a sea plane to Isle Royale from the Houghton Sea Port. Since they cannot accommodate boats, kayaks or paddleboards, this is a great option for backpackers. You can rent canoes on the island or arrange for a water taxi to drop you off somewhere on the island.

PERMITS

Once you’ve secured transportation, buy your permits. Isle Royale charges a $7 per person daily entrance fee, which can be paid online. You can also buy a season pass for $60, which is good for three people.

Those venturing out on the island need to secure a backcountry permit upon arrival. The permit is free and park rangers will need to know your itinerary for the duration of your stay.

GEAR

There’s a lot of it. Pack like you’re going backpacking. While paddle trips offer the luxury of not having to worry about weight, once the portages come, you’ll regret those extra pounds.

Pack wisely. Everything, I mean everything, needs to be stored in a durable waterproof bag. We each packed

The Logistics in a 65-liter and a 55-liter NRS bags. We packed heavy. A 65-liter backpack for a six- to seven-day backpacking trip on land is usually more than enough. Grab a handful of different colored stuff sacks in various sizes. This will help you keep your gear organized— red bag has the snacks, blue bag has dinner, green bag has clothing, or was it the black one? You get the idea. FOOD Plan your meals and then add some extra. We ate dehydrated meals for dinner, which aren’t that bad. Our favorites were the pad Thai and chana masala from Backpacker’s Pantry and lasagna and chicken and dumplings from Mountain House. Breakfast was oatmeal and lunches were high-calorie and fatty foods that didn’t need to be heated up: sardines, peanut butter, smoked oysters, meal bars, candy, jerky. Don’t forget to leave

From left: Grant takes a snooze on Green Island while we wait for the weather to turn; The guys and their trusty boards wait for the ferry home—exhausted, dirty, hungry but proud.

the tent vents open after chili night. Actually, every night—keep the vents open every night.

FISHING

Toss a spoon or a bucktail lure, any color and any size, into an inland lake on Isle Royale and you’ll catch a northern pike. I used a lightweight spinning rod with 12-pound test with a steel leader.

On Lake Superior, many people have success trolling the drop-offs with deep diving lures in the 10- to 14-foot range. I had more success vertical jigging on calm days in 75 to 100 feet of water. You do not need a fishing license to fish the inland lakes on Isle Royale, but you’ll need a Michigan DNR license to fish on Superior.

WEATHER

Your biggest foe is also the most unpredictable one. If you’re exploring on foot, you don’t have as much to worry about. Those on watercraft will want to heed the forecast and your intuition wisely.

There is no cell service on the island. Weather radio reception is spotty. When you arrive at Rock Harbor, take a picture of the printed-out weather forecast on the visitor center message board, it may be the last one you see. Satellite emergency beacons like the Garmin inReach can pull weather forecasts, send text messages and alert authorities in case of an emergency.

WATERCRAFTS

Paddleboards are remarkably stable and can handle swell and wind better than a canoe or kayak. One of the worst things that can happen on a canoe or kayak is “swamping it” during an open water crossing. You can’t swamp a paddleboard. When you fall off, you get back on it—this isn’t always an option with other vessels.

Beyond any safety concerns, paddleboards are remarkably efficient. Unlike paddling from a seat, a paddleboard allows you to engage your entire body for the stroke. It’s more powerful, you get more glide from each stroke and you can cover a lot of ground.

We paddled touring boards that are high-volume boards built for long distances. Our boards averaged 12 feet in length, 30 inches wide and 6 inches thick. This trip would not have been possible without quality gear rentals from Sleeping Bear Surf and Kayak in Empire. Thanks, Ella!

A tyrannical tsar, a fugitive agronomy student, an isolated Lake Michigan island, some crazily optimistic dudes …

all a part of the story of the greatest strain of rye on Earth and its journey to become a legendary whiskey.

O

n a bluebird morning this past June, the Manitou Island Transit ferry puttered out of Leland harbor headed for uninhabited South Manitou Island, which lies some nine miles off the Leelanau Peninsula. Onboard, 90 beamingly happy guests (including the renowned whiskey writer Chuck Cowdery and Maggie Kimberl of American Whiskey Magazine) and the staff of Northern Michigan–based Mammoth Distillery were already raising cocktails to the day’s occasion: the first-ever Rosen Rye Day.

The celebration would center around a public reveal of a mere quarter-acre of an extremely rare rye said to have once been the key ingredient in some of the finest whiskey in the world. Although Mammoth staff had painstakingly planted the precious crop on the island just last fall, Rosen rye has a history on South Manitou—but it had been almost a century since the grain graced this beautiful island.

The hesitant among us, myself included, started with bloody marys, as it was still morning; the rest threw decorum to the wind and ordered selections from the open

Opposite: The Rosen Rye field at the old Hutzler farm on South Manitou Island. Above, left to right: Matt Hayes, Phil Attee, Chad Munger, Ari Sussman, Collin Gaudard, Doug Burke. Below: Looking down on the South Manitou Lighthouse Station from the top of the lighthouse.

bar that included the Whiskey Tango Foxtrot— Mammoth whiskey, pineapple-jalapeño mixer and ginger beer. It will be six to eight years before the first bottle of Rosen rye whiskey is available to the public, but it’s never too soon to cheer a world-class whiskey in the making. Especially this one, packed as it will be with equal parts story and flavor. As the ferry rolled into the infamously dangerous Manitou Passage, Mammoth employee Matt Hayes hoisted the huge, bright orange and black Mammoth Distillery flag into the breeze where it flapped

with swashbuckling authority.

The moment brought home the staff-wide pride in this company that is more about ethos and heart than bottom line. Headed by founder and CEO Chad Munger and his compatriot in right-brain visioning Whiskey Maker Ari Sussman, Mammoth’s products have garnered a number of awards (most recently the Chairman’s Trophy at the prestigious Ultimate Spirits Challenge in New York for their Northern rye) in the decade since they opened their first tasting room in tiny Central Lake. They’ve also added three more tasting rooms in Northern Michigan and one downstate in Adrian, and their products are distributed nationwide. Yet, Munger describes the company’s growth as “slow and purposeful.” The purpose is to build community—as in tasting rooms that feel like neighborhood bars—while utilizing authentic Northern Michigan ingredients no matter the effort. “We aren’t show dogs,” Munger says. “We are work dogs.”

Which brings us to the Rosen rye, their toughest and most heartfelt project to date. The four years since Munger and Sussman hatched a plan to bring the rye back to South Manitou Island, where its glory days began over a century ago, have been marked with plenty of sweat, probably some blood but no, not tears. More like a company-wide, “Holy wow, we are making this happen!” It’s a great story built on the back of another epic story: The origin of South Manitou Island Rosen rye itself.

Clockwise: Boarding the Manitou Transit Ferry the Mishe-Mokwa; passing the North Manitou Shoal Light Station located in the Manitou Passage; Avery Robinson of Black Rooster, a guest of Mammoth Distilling for the trip, hands out slices of authentic handmade Russian rye bread—jam or butter, our choice; chatting at the floating bar; waiting for the tractor ride out to the Hutzler farm. Opposite: Louis Hutzler, one of the “Manitou Kings,” stands in his field of Rosen rye circa 1925; our group heads into the Rosen rye field.

In 1903, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia exiled Joseph Rosen, a teenager, to Siberia for his political views. Rosen escaped to Germany where he studied agronomy before immigrating to the United States and making a beeline for Michigan Agricultural College—now Michigan State University. There he met plant-breeding genius Professor Frank Spragg. Interested in strains of Russian rye, Spragg asked Rosen to have his parents send seeds from Russia. Sometime later, several cups of seeds arrived in an envelope mailed by Rosen’s parents. Spragg went to work and came up with a hybrid he named Rosen after his young Russian friend.

By this time, Rosen had moved on to receive a doctorate from the University of Minnesota, and his interaction with the seed that bears his name became minimal. Meanwhile, Spragg sent Rosen rye seed out across the state, and it consistently produced yields and characteristics that were far superior to other varieties. While most rye in this country is used for pasture or as a winter bedding crop, it was soon clear that although Rosen was certainly prolific, it was also an elite grain that could produce whiskey of the finest quality.

The new champion grain had only one drawback: It cross-pollinated too easily with inferior strains. Within two years of cultivation, Rosen lost its super powers. Spragg knew he needed to find a place to breed pure seed stock isolated from other crops of rye. By 1918, he and his team of researchers had zeroed in on South Manitou Island, just 200 miles from his East Lansing campus. Except for steamers stopping at the harbor for cordwood, the small island community well-known of them being August Beck and brothers Louis and George Hutzler. Their fame, and that of the rye they grew, was amplified considerably by Prohibition. Not surprisingly, the prized island seed stock surreptitiously made its way to whiskey-making meccas including Kentucky, Pennsylvania and Maryland. But even as the rye’s reputation soared, events were unfolding that would end the Rosen rye dynasty. By the time Prohibition ended in 1933, the drinking public had come to favor the taste and price of whiskey made with corn instead of rye. Simultaneously, the new coal-burning ships replacing steamers on the Great Lakes didn’t need to take on cordwood so they had few reasons to stop at the island. Farmers no longer had a guaranteed way to ship rye and other produce to the mainland for sale. By the early 1940s, commercial crops—the magic rye included—had vanished from South Manitou.

Some 80 years later, on that first-ever Rosen Rye Day, Chad Munger and Ari Sussman stood

It had been almost a century since the grain graced this beautiful island.

lived a secluded existence. When an emissary for Spragg, a Mr. J.W. Nicholson, came calling to ask if the farmers there would be willing to grow Rosen rye, it was a momentous occasion.

Eleven farmers signed on to grow Rosen and only that variety. As the story goes, they agreed to drown any one of them who dared break that rule. From the first crop harvested in 1919, Spragg’s experiment was a stupendous success. Island Rosen rye seeds were sent to farms all over the country. When the rye had lost its mojo after several years, there was fresh seed stock waiting on South Manitou.

The South Manitou rye was so amazing that the island farmers raked in award after award at both national and international agricultural expositions. Their reputation even earned them the nickname the Manitou Kings—the most at the edge of the field of shoulder-high Rosen rye that their Mammoth team had planted on the old Hutzler farm last fall. As the rye swayed

in the breeze, Munger and Sussman recounted the story of how Mammoth Distilling brought rye back to the island.

Four years ago, Sussman was mining the agriculture and food archives at Michigan State—indulging a personal passion while doing the R part of R&D for his company—when he came across a managed by the National Park Service, an entity not given to allowing private enterprise on federal land.

Munger, who built his company on vision first (and figuring out how to get there later), plunged in. Job number one was finding Rosen rye seed. It turned out that the United States Department of Agriculture had seed stashed safely away in its vault at the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation. Not long after Munger asked for it, 18 grams came in the mail—just as it had come

Above: Lead agronomist Doug Burke gives us a rundown on the perils of island farming, among them: the poison ivy. Once when he forgot his boots, Burke completely wrapped his feet in yellow tape to protect them. Below: The boarded up Hutzler farmhouse is a part of the island’s lost-in-time ambiance. Opposite, from top: The ferry bar stocked with Mammoth products; the magic rye up close; leaving the island—and the Rosen rye—behind.

full-page ad for Old Schenley rye in a 1934 issue of Vanity Fair touting that it was made with Michigan Rosen rye: “The most compact and flavorful rye kernels Mother Earth produces were used for this luxurious brand.”

“How could I not have heard of this before?” Sussman recalls thinking. He shared the ad with Munger ASAP. “We had exactly one conversation where he described what he discovered, and it was pretty clear to me that this was something that we needed to try to do,” Munger says. “It was just too close and too relevant to the business we were building.”

Munger and Sussman didn’t want to just grow Rosen rye, they wanted to grow it on South Manitou because, obviously, the island conditions are ideal—but also for historic authenticity. There was a problem: South Manitou is a part of Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore and to Spragg from Russia 120 years ago. Next, Munger turned to Michigan State University, the birthplace of Rosen rye, and specifically to Dr. Eric Olson of MSU’s College of Agriculture & Natural Resources. Olson helped Munger and Sussman uncover Spragg’s records from so long ago—and in so doing, established a historical connection to the rye and South Manitou that was all-important to the administrators at Sleeping Bear. Just as farmers have been issued special use permits to grow corn at Gettysburg National Military Park, where cornfields had stood during the Civil War, Mammoth Distilling received permission to plant Rosen rye where it had been historically grown on South Manitou Island.

Cutting through the federal government’s red tape was a whew moment, but the real work hadn’t even started. In accordance with their permit, the Mammoth crew must plant, tend and harvest the rye just as the Manitou Kings did: with no pesticides, no irrigation,

no electricity and no machinery other than a tractor. They had to bring their own gas for the tractor and pitch a tent in one of the primitive island campgrounds at night. It all adds up to what Munger calls “farming in the raw.”

Three young, energetic and devoted Mammoth employees head up the island farming operation: Matt Hayes, custodian of the Mammoth flag on our trip over; Lead Agronomist Doug Burke (aka Farmer Doug), who sports a rye tattoo that stretches along his right forearm; and Mammoth’s Head Distiller Collin Gaudard, a fifth-generation Leelanau Peninsula farmer whose grandfather was once keeper of the South Manitou Lighthouse. “It just feels so right to be farming here,” he says.

The team’s first planting was October of 2020—a mere hundred square feet on the old Hutzler farm. The ferry trip over was in rocking

It’s never too soon to cheer a world-class whiskey in the making, especially this one, packed as it will be with equal parts story and flavor.

and rolling autumn waves, and when they arrived at the farm, they found the field covered in Amazonian-sized poison ivy. Yet, they dug in with pioneer perseverance, gearing up in boots, long pants and long-sleeved shirts to disc the poison ivy into oblivion. They harvested that rye by hand last summer, and then used the seeds to plant the quarter-acre crop that now waves in wind at the Hutzler field. The seed from that in turn will be used to plant more acreage and so on, until 40 acres of historic rye beds will once again be cultivated. Additionally, Mammoth Distilling has leased a farm on Beaver Island, north of South Manitou, where they will grow Rosen rye. All too soon our group had to say goodbye to the rye and the bucolic serenity of the Hutzler farmstead so we could make it back to the ferry in time. But there wasn’t one of us who wouldn’t return to the island for Rosen Rye Day when the whiskey is ready. Bloody marys be damned. On that morning we’ll all be drinking rye.

Elizabeth Edwards is senior editor of Traverse, Northern Michigan’s Magazine. lissa@traversemagazine.com

Beth Price is an editorial and commercial photographer based in Northern Michigan. She’s passionate about capturing authentic human experiences that help achieve a greater appreciation for the natural world we live in. bethpricephotography.com

T

The Mitten State is many paradises within a single boundary, a truth understood by perhaps no one better than the fly angler, who in a single week might find themselves fishing trout in Crawford County, muskies in the Upper Peninsula and steelhead on the west-coast tributaries. Today, I’m leaving one paradise—my trout camp near the Manistee River—for another: A big-water bass bonanza at the end of the road. Emphasis on end. My destination is Waugoshance Point in Emmet County’s Wilderness State Park, where I’ll be fishing for smallmouth bass with Captain Ethan Winchester of Boyne Outfitters. Waugoshance is a peninsula’s peninsula. If Michigan is the Sistine Chapel, Mackinaw City is only Adam’s head; Waugoshance Point is the business end of Adam’s finger, reaching out to God.

I meet Ethan and his friend, Matt Mates, at the boat launch at 9 a.m. as the cool of the night is lifting and a proper summer heat shoulders in. “The wind is perfect today,” Ethan assures, looking out across the Straits toward the bridge and the U.P. beyond. I’ve known Ethan for years, and together we’ve explored big and small trout streams alike. But we’re here to ply the Lake Michigan flats with the new boat he acquired for the mission, a Hog Is-

Ocean.” – Captain Ethan Winchester

land skiff with a poling platform.

The boat is a manifestation of Ethan’s latest obsession—or rather his first. Long before he spent a decade developing Boyne’s inland trout opportunities, he was on the big water every day, working in rescue and captaining private vessels. As we curve into our first cove, I ask Ethan whence the change.

“I love the river,” Ethan says. “But the feeling of vulnerability and the prism of blues here can’t be replicated anywhere else. Maybe the Indian Ocean.”

Looking out over the expanse of water beyond our island cove, I realize he has a point. This could be the Seychelles, except for the fact that we’re surrounded not by bonefish or permit, but smallmouth bass, pike, drum and muskies. And that’s Ethan’s other draw to this lake life—native big-water fish.

“It’s not until you get out here on a

Previous spread: When navigating the flats, there’s always one best line to take between the shoals and boulders. This spread: A set of elevated eyes makes spotting and stalking fish a whole lot easier.

Top: Crisp double hauls and laser-tight loops help deliver flies through the prevailing winds. Bottom: While wind is a fact of life in flats fishing, a good captain can always find some fashion of lee. Right: The extreme clarity of the water creates a feeling of floating on air.

boat that you realize what’s around in fishable numbers. There are some big muskies hanging around, as well as freshwater drum. Much like permit, they’ll gladly eat live bait while snubbing the fly.”

Then there’s the lake trout, a puzzle Ethan looks forward to solving.

“The challenge with lake trout is timing. Seas are rough in the spring and fall when lakers are closer to shore and at depths we can access with a fly rod. But we catch them in Little Traverse Bay and northern Lake Huron early and late in the year. They’re here.”

“Strip… strip… strip,” Ethan chants down from the poling platform to Matt, who is up first on the casting deck. His song is an attempt to impress the right cadence on a proper flats smallmouth presentation, and Matt’s line hand moves slowly and rhythmically, as if he were darning a tear in a blanket. A trout angler accustomed to mixing up long quick strips with short stitches and rod tip quivers might have a hard time with this presentation, but in order to whet the smallmouth’s appetite, a slow, steady approach is essential. All three of us stare intently at the stark blackness of the marabou leech, visible at a great distance as it inches over the sand flat. Suddenly another, larger dark form appears behind it. The bass, perfectly attuned to its surroundings, looks like nothing more than a phantasm of sand.

Fly fishing has been described in many ways. Looking at my first bass of the day, I find myself favoring the late Gary LaFontaine’s slightly more philosophical version, that fly fishing is the pursuit of perfect moments.

Left: The angler’s payoff: a beautiful native fish perfectly matched with its surroundings. Above: A good day on the flats can feel like a waking dream.

But it’s towing a dark slice of shadow with it across the flat, and in the next moment that shadow eases up just inches behind Matt’s fly.

“Stop, stop… set! Set!” Ethan implores, and Matt is fast to his third fish of the day.

There’s a special beauty to this collaborative, communicative way of fishing. It’s an approach born of saltwater fly fishing, with a guide or seer high atop a poling platform, looking for fish and moving the boat carefully with a push pole, which is far stealthier than a set of oars. But the seeing works both ways— fish can spot a boat at distance, and so casting distance is at a premium. There’s no creeping in close like on a trout stream, using broken water and riparian obstacles to camouflage your presence as you work a rising fish. Out here on the big water, which at times can feel like one huge aquarium, casts must have good distance and decent form. Land your fly directly on top of a fish, and it will certainly spook. Cast too short and it might see the boat before it seals the deal. But gracefully plunk a fly down at 60 feet in the direction a spotted fish is swimming, and you’re in for a moment of beauty.

Then there’s the hook set.

There’s a tendency when sight fishing to jump the gun. The art of flats fishing for smallmouth requires a real sort of grace under pressure. Anticipate the eat and you will set the hook too early. React to the eat and you can set too late.

I ask Ethan how to get the timing right. He smiles and pushes off toward fresh water.

“Be one with the fish.” After lunch, it’s my turn up on the casting deck. I strip out more line than I think I’ll need, gather the wet marabou leech up in my hand, and start scanning the water. Fly fishing, at its best, feels like a form of enchantment, and staring over the sand and stones, the glittering lattice of light on the seafloor, I’m on full alert for magic. The folk literature of the north associates

conjurings, gnomes and elves with the dark understory of pine forests, but as I get my flats eyes, it seems otherworldly things are hiding just out of sight. “Bass,” Ethan declares, knocking me out of my stupor. “Four of them.” It is a quirk of fish in general, and smallmouth bass in particular, to gravitate toward anything that stands out in the environment. In this case, a boulder the size of a bowling ball and tuft of reeds no larger than a bouquet of roses holds four good fish. I identify the largest and drop a long cast off to the side, hoping to peel it away from the group. But then something strange happens. I ask Ethan how to get the timing right. He smiles and pushes off toward fresh water. “Be one with the fish.” Like a cartoon elephant stepping out from behind a lamppost, an even larger fish untucks from the reeds and, with a few easy tail strokes, eclipses my original target and inhales my fly.

The confusion has me late to my hookset, but it’s no matter: The hook drives home and the rod bends deep. The act of fighting my fish is a dinner call to all other bass in the area, who swarm my fish, hoping that the tussle will cause it to cough up an earlier part of its lunch, a habit of smallmouth bass. Finally, we get the fish into the net. It’s a beautiful specimen, pale with fine striations and subtle markings, a perfect big water bass, and I stare at it for a minute. Fly fishing has been described in many ways. There’s the literal: standing in the water swishing a stick. And the comical: standing in a tub of ice-water casting 100-dollar bills into a fire. Looking at my first bass of the day, I find myself favoring the late Gary LaFontaine’s slightly more philosophical version, that fly fishing is the pursuit of perfect moments. As I release the bass, which yaws slowly across the flat as a pair of monarchs flutter over the surface in the opposite direction, I wonder: can I stay in this perfect moment forever? Could I, at the end of the day, decline the ride back to the launch and instead make a stand on one of these unnamed islands, chasing fish all day every day like some bass-bewitched Caruso? I take quick inventory of my provisions. There are a few White

Claws. An uneaten brownie leftover from our too-big lunch. In my dry bag, there’s a raincoat I could use for shelter. I’d have to borrow a lighter and a knife. Could I find enough driftwood for nightly fires? How are the black flies? I’m still scheming when the boat swings around on its axis.

“Fish,” Ethan cries. “2 o’clock and 60 feet… 55… 50…” And so I leave my machinations aside for the time being and begin working some line into my cast, edging my bare feet out to the very edge of the bow, squinting, waiting, for the next perfect moment to swim into view.

Dave Karczynski is the author of “From Lure to Fly” and co-author of “Smallmouth.” He splits his time between teaching writing and photography at UM-Ann Arbor and chasing the bugs Up North. Follow him on Instagram: @davekarczynski.